1. Introduction

Art of Recovery responded to the current global context and the mental health challenge associated with refugees and asylum seekers. Internationally foregrounded by the European Union, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and the World Health Organization (WHO), the health of refugees and asylum seekers is now a global priority (

UNHCR 2018;

WHO 2017). Since May 2017, WHO has shifted its approach on migration from a solely humanitarian-based approach to one based on health systems that strengthen the physical and mental health of refugees (

WHO 2017). WHO’s premise is that at global and national levels, health policies and strategies to manage the health consequences of migration and displacement have not kept pace with the speed and diversity of modern migration and displacement.

The project was a collaboration with the charity Freedom from Torture, who provided a supportive environment for the research in one of their North of England centres. Art of Recovery explores how participatory art contributes to the recovery of refugees who experience trauma.

The project developed from a growing recognition that refugees appear to benefit from engagement in creative arts (

Andemicael 2011;

Dutton 2017), and participatory arts in particular (

Rose and Bingley 2017;

Barnes 2009). With the aim of developing an appropriate research design, we first undertook a pilot study,

Migrating Art (2017), in partnership with the Merseyside Refugee & Asylum Seekers Pre & Postnatal Support Group in Liverpool, United Kingdom (UK). This charity supports women migrants who are victims of rape, trafficking, sexual violence, domestic servitude, and other forms of gender-based violence and human rights abuses.

Art of Recovery built on this earlier pilot, in particular in relation to working in a safe, therapeutically supportive space. Both projects adhered to strict ethical guidelines provided by the University Ethics Committee and respective ethics committees of the migrant-supporting charities (approved in April 2016 and May 2017).

Freedom from Torture (FfT), as one of the world’s largest charities in the field, has provided treatment for more than 57,000 survivors of torture. The charity provides a broad range of support for clients who attend weekly sessions, including psychological and physical therapies, forensic documentation of torture, legal and welfare advice, and creative projects. Their centres employ language interpreters ensuring well-supported communication for clients.

Although organisations supporting refugees through arts projects in the UK have grown over the last decade, there is a need for more research and evaluation of the rehabilitative potential of participatory visual art (

Hayhow et al. 2016). While these organisations may reflect on their practice and keep records of outputs and impacts achieved, there is little collation of evaluative material in arts projects, other than in reports to funders (

Sonn et al. 2013). Evaluation is required to enable practitioners of participatory visual arts with refugees to establish methods of best practice (

Sonn et al. 2013).

Art of Recovery conducted a qualitative thematic evaluation to ascertain the impact of participatory arts for a small group of refugees, supported by FfT.

In this paper, we first discuss the context for refugees who have been tortured and displaced. We describe the model of recovery on which we explore the participatory arts intervention, and map key theories underpinning the research. The explanation of research methods involves qualitative participatory approaches, the thematic narrative and visual data analysis methods, followed by a section exploring the findings. Finally, an evaluation of the intervention assesses the potential of arts-based approaches to contribute to the recovery and transition of refugees who experience trauma.

1.1. Displacing Mental Health and Well-being

According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (

UNHCR 2018), the world is witnessing the highest levels of human displacement on record. UNHCR estimates there are 65.6 million forcibly displaced people worldwide, of which 22.5 million are refugees and asylum seekers living in exile. In 2016, the number of applications for asylum in the UK, excluding dependents, was 30,747 (

Refugee Council 2017). Refugees and asylum seekers often experience traumatic events, before and during displacement (

Hargreaves 2002;

Hollifield et al. 2002;

Nosè et al. 2017), and afterwards. Post-displacement trauma can continue after arrival in the UK, where trauma can occur in relation to imprisonment in detention centres (adults and children), and resettlement stress related to stigma, shame, hostility, racism, and discrimination (

Miller et al. 2006). In comparison with the general population, refugees and asylum seekers have been shown to experience higher prevalence rates of a range of mental health disorders, and disorders specifically tied to stress (

Fazel et al. 2005;

Bogic et al. 2015;

Slewa-Younan et al. 2015). The most studied mental health problem in the refugee population remains post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as it is 10 times more likely in refugees and asylum seekers compared to host populations (

Fazel et al. 2005;

Bogic et al. 2015;

Slewa-Younan et al. 2015). Even if the prevalence of PTSD is over-estimated for instrumental purposes to mobilise resources (

Fassin and d’Halluin 2007), there is evidence that it is substantially increased in refugees, whether adults or children (

Fazel et al. 2012). Research indicates the prevalence of PTSD in survivors of torture is over 90% (

Johnson and Thompson 2008;

Moisander and Edston 2003;

Mollica et al. 1998). FfT (originally known as the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture) treats over 1,000 torture survivors each year. Most arrive traumatised, vulnerable, and fearing further persecution. They have a right to rehabilitation under Article 14 of the United Nations Convention against Torture (

UNCAT 2012). It is important to provide treatment soon after the events, because early psychosocial support is a decisive factor in limiting the development and severity of PTSD symptoms (

Dutton 2017;

Wilson and Drožðek 2004). A systematic review undertaken by

Robjant et al. (

2009) indicates that lengthy asylum processes result in increased risk of psychiatric disorder. Long delays and very slow administrative processes for asylum seekers in the UK means that sometimes individuals are in the system for many months, sometimes years. Many detained indefinitely in immigration centres are destabilised, or retraumatised by the experience having encountered torture in similar conditions (

Boyles 2017).

Mental and physical repercussions of torture mean its survivors are particularly susceptible to social isolation and its adverse psychological effects (

Acheson 1998;

Burnett and Peel 2001;

Gorst-Unsworth and Goldenberg 1998). Having left behind their culture and homeland, known way of life, community, work, political life, home, friends, and family, many refugees hope to be reunited with family at a later time (

Boyles 2017), but many live on their own in exile, reliant on their inner resources. Migration itself is a potentially traumatic experience (

Grinberg and Grinberg 1989), felt by the individual as a discontinuity, a breakage in the self, in the relationship with the environment, and with the individual’s past (

Le Roy 1994). Reconnection is a significant element in enhancing mental health outcomes (

Burnett and Peel 2001), and it is important for migrants to find ways to reconnect with society, and crucial for survivors of torture on their journey of recovery (

Herman 1992).

Gorst-Unsworth and Goldenberg (

1998) examine the health needs of refugees to suggest the importance of establishing informal groups, as a useful way of sharing experiences and ways of coping and making sense of past experiences. They highlight the importance for refugees to develop ongoing links and friendships with people in the host community, as well as making contact with people from their own countries (

Epstein 1996); in this way, the best mental health outcomes are achieved (

Burnett and Peel 2001).

1.2. The Road to Recovery

Examining the meaning and process of recovery is useful in this context. In this research, we draw on

Herman’s (

1992) three-stage model of recovery from trauma, the model recommended by the UK Psychological Trauma Society for use by trauma therapists based in the UK (

McFetridge et al. 2017). In this model, Herman identifies the key features as three stages in the process of recovery, namely, safety, remembrance and mourning, and reconnection. She defines recovery as based on the empowerment of the survivor and the creation of new connections (

Herman 1992). As (

Lamb 2017, p. 56) explains, recovery as defined in the mental health field is the process by which individuals find ways to live a meaningful, ordinary life, even if they continue to experience symptoms. For Lamb, Herman’s model is applicable to survivors of torture, even those who experienced prolonged, repeated trauma, and sustained threat to life. She notes, according to

WHO (

1992), that these individuals may have developed symptoms of PTSD, and enduring personality change resulting from their catastrophic experiences (

Lamb 2017, p.57). When recruiting for

Art of Recovery, therapists at FfT identified potential participants as those able to engage in stage three of Herman’s process of recovery: individuals for whom reconnection proceeds or is possible. Most participants had established a relative level of security and safety in their new environment and were incrementally working through key rehabilitation processes used by therapists aimed at recovery, including: stabilisation of trauma symptoms; facing traumatic memories; moving toward integration of the trauma into a new narrative of self and personality (

Lamb 2017, p. 57). As Lamb suggests, “the goal is to help survivors connect with the changed person they have become, the trauma more or less integrated into their autobiographical identity” (p. 57). In Herman’s terms, participants were in various stages of the ability to move forward to live an ordinary life.

According to

Kidd et al. (

2016), the inclusion of refugees and asylum seekers in participatory arts has emerged gradually as a recognizable phenomenon in the UK. In 2016, around 200 organisations in the UK provided programmes related to arts and refugees (

Hayhow et al. 2016), and the provision is growing as councils, community groups, churches, and charities respond to the increased numbers of displaced people in the UK. There is recognition of the role of participatory arts in healing trauma, as the approach supports individuals in accessing unprocessed traumatic responses and provides an opportunity for creative expression (

Dutton 2017, p. 275). Survivors of trauma with limited language or the inability to put ideas into speech are particularly likely to benefit from self-expression through art, music, movement, or play as they provide the means to convey ideas without words (

Dutton 2017, p. 271).

The focus of participatory arts is slightly different to that of art therapy. Participatory arts and art therapy are sometimes positioned against one another, with participatory arts set up within a recreational, social, or research context with little or no direct therapeutic focus. However, as

Pavlicevic et al. (

2014) note, there can be similarities in that artmaking, whether in a participatory or an art therapy context, can both use expressive media and be experienced as therapeutic whether intentional or not. The differences are in the context and intention: art therapy is a psychotherapeutic technique using art as a means to express thoughts and feelings, facilitated either in a group or individual sessions by trained therapists using recognised models of interaction and intervention (

Malchiodi 2003). Participatory arts is a means to bring people together to share ideas, events, and experiences using arts media. Although participation is not intended to be directly therapeutic, participants do report indirect benefits of these kinds of arts events and groups, both within community or research contexts (

Tsekleves et al. 2018).

Art of Recovery sought not to provoke the exploration of difficult issues, or traumatic memories, but aimed to provide a space for people to meet, carry out meaningful art activities together, and connect with and share thoughts and feelings about places with positive associations. Refugee-supporting organisations are interested in the use of participatory arts as an adjunct to support clients engaged in therapy and, as

Stickley (

2010) argues, to better understand the potential for these arts-based approaches to open up possibilities for recovery beyond models focused on mental health.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of

Art of Recovery was to explore the potential of a participatory arts engagement with place to contribute toward the recovery and reconnection of refugees who experience trauma. To this end the project set up art workshops where participants could engage in 2D and 3D artmaking: painting with acrylics, drawing with crayon and pencil, and creating collage using a range of tactile materials, including textiles, felt, wool, stones, and feathers. Through these media, participants expressed their experience of safe spaces and places, encountered as safe havens, either recalled from their country of origin, or experienced on their journey toward safety, or an imaginary place. Emphasis in research design on positive memories and associations sought to minimise the potential for re-traumatisation. Artmaking from remembered or imagined safe places was examined in terms of the contribution to the participant’s recovery and transition to a new environment. We explored how best to facilitate participants in connecting with a safe place within themselves through imaginary and visual representation. The project was informed by practices in participatory arts, therapeutic therapies, and the theoretical framework of therapeutic landscapes (see

Rose 2012 for a detailed discussion of therapeutic landscapes in this context).

There were three phases to the project:

Phase 1. Ethical approval was provided by the authors’ university research ethics committee (Ref: FL16211) and by FfT (Ref: R37). Prior to recruitment for workshops, researchers twice met FfT’s therapists to discuss research design and to address specific vulnerabilities in the group. A former client serving on their Advisory Board was involved in discussions, as were five language translators to discuss terms and uses of language, and to identify possible cultural differences in interpretation. Therapists’ professional knowledge gauged the suitability of participants invited to join the project. Each was at a stage in recovery with the potential to benefit from participatory artmaking, but not regularly attending other activities.

Phase 2. Following recruitment, four participatory arts workshops were delivered over six weeks. Qualitative data collection included demographic data providing a general profile of the participant group, three questionnaires designed to prompt semi-structured individual and group discussions during workshops, end of workshop informal reflections, observations in the form of field notes, and photographs of participants’ artwork. Demographic data, questionnaire responses, and discussions together with visual data were collated with written field notes for each workshop. After each workshop, the research team met to debrief with the therapist, the former client, and interpreters. Following the final workshop, the research team had a final debrief with the lead FfT therapist to discuss key data analysis and findings as part of the triangulation process.

A qualitative thematic analysis of written, visual and observational data was completed by the research team, using primary codes based on Herman’s theory of recovery: terms of remembrance (images or comments relating to original homeland), mourning (images or comments communicating nostalgia, loss, and grief), and reconnection (images or comments expressing life lived in the present). Secondary coding identified two sub-themes: the participants’ experience of transition between their homeland and the UK; and new social connections, including the participation in the workshops, and how this contributed to their sense of well-being. The findings were interpreted by the research team and are discussed below.

Phase 3. Dissemination of findings with an accessible summary of findings produced for FfT, participants, and other interested refugee groups, made available on FfT’s website.

Demographic data recorded a total of N = 14 clients, of whom N = 10 were male and N = 4 female, aged between 20 and 40 years, with the majority aged between 20 and 30 years old. Most participants had spent all their lives in their country of origin before exile, a small number (N = 2) having migrated to a country other than the UK at an earlier age. The research element of the project constituted workshops 2, 3, and 4 (W.2, W.3, W.4), producing 33 artworks, recorded as digital photographs. The participants originated from Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Iraq, and Sri Lanka. All participants had family remaining in their homeland.

W.1. Facilitated participants in making a collage or painting on any subject with positive associations. Designed as a “warm-up”, activities introduced working with art materials, and helped to relax everyone into sharing ideas and artmaking together in this context. Demonstrations in assembling tactile materials emphasised collage as an accessible approach, alongside demonstrations in applying acrylic paints on canvas, mixing colours, and using different brushes for specific effects. Such demonstrations sought to invest participants with a greater means of expression, rather than to achieve a level of expertise.

W.2. Facilitated participants’ artmaking on the research theme outlined above. Participants made collage, paintings, or a combination, on A4 or A3 sized canvasses. They continued to explore the subject matter throughout W.3 and W.4. Thoughts about artworks were shared in individual discussions with researchers, and each other. After W.3 and W.4, an exhibition in the space of the artworks enabled everyone to see all the artworks produced, and to discuss their thoughts and reflections. Questionnaires provided toward the end of each workshop enabled individuals to work with their language translator to provide written responses to questions about the experience of being in the workshop, the process of creating artworks, and their subject matter.

3. Findings

3.1. Artworks

Of the paintings produced, participants almost entirely chose to depict existing places and objects (N = 33) rather than imagined. Places were predominantly from their homeland (N = 26) and were places with which they had positive associations. Some also represented places from their present life in the UK. Within the total output, landscapes featuring natural elements were most prevalent (N = 49), with the sea, lake, rivers, fields, mountains, gardens, and croplands occurring most frequently. These settings were populated by trees and flowers (N = 10), enhancing places where people gathered, shaded from the sun under a tree, or in a pavilion, park, or garden (see

Figure 1).

Natural landscapes frequently depicted weather: sun, rain, and rainbows (N = 9). There were a number of non-natural environments (N = 27) represented by buildings, interiors, cityscapes, a temple, church, house, restaurant, etc. (N = 12), and other depictions, such as roads, cars, trucks, a carpark, a football pitch (N = 8), and ships, boats, and bridges (N = 7). As participants explained, none of their artworks represented journeys undertaken in search of a safe haven. Ships and boats signified previous occupations as fishermen, as did cars and trucks, rather than journeys.

Several images depicted fields and croplands on farms where a participant once lived, and several artworks represented places where they once worked, or their previous occupations (see

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 below). Respondents described feeling nostalgic, and both sad and happy while they were engaged in making these artworks. Even though they were pleased to remember places, they mourned their previous occupation, their home, and their family, knowing they were unable to return. Previous occupations were important factors in identity, financial independence, and social and family roles, regarded as positive and valued. Participants experienced conflicting emotions in relation to places they remembered versus their present situation, where loss of occupation was allied with loss of identity, as illustrated by Mahamadou in

Figure 2 below.

One participant articulated this when he declared himself: “Not happy, no joy inside. Speaking English is a joyful language, so I will not speak English. I used to drive a lorry and now I can’t”, Zain (Iraq).

Participants expressed conflicting emotions regarding the beauty of their homeland against the reasons why they had to leave, and their present situation. As Chathura states, “

I feel nostalgic and I miss my village”, Chathura (Sri Lanka), and Tharindu (Sri Lanka), “

This is a place in Vanni in Sri Lanka (…) where I was a fisherman, fishing with a group of men. It is helpful to remember and I miss this place”, (see

Figure 3).

Participants expressed pleasure in reengaging with these places, even while experiencing their loss: “When I draw this, I will see my birthplace and I really miss my birthplace (…). It is the most wonderful place ever in my life. Wherever we go, however we live, we still miss this beautiful Island”, Hiruni (Sri Lanka). Remembering the place where they lived and worked was a trigger for concern for what has since happened to it, or their remaining family, “This is the paddy (rice) field I worked (…) it was very hard because I do not know what happened to that field (…) I worry about my family back home”, Roshan (Sri Lanka). Participants noted the importance of these remembered places as real, as Roshan comments, “These places are not my imagination, but the place where I lived with my parents and five sisters. I am remembering how we were a happy family. I heard from my wife it had been destroyed by the Sri Lankan army”. Roshan explained he now fears for the safety of his family (see

Figure 4).

Several participants represented buildings inhabited by people, such as a painting marked by a Red Cross entitled

Pharmacy painted by Divine (Democratic Republic of Congo). The painting depicts the interior of the clinic where a pregnant woman lies on a bed, surrounded by medical drips and stethoscopes, another person, possibly a doctor, sits in a chair, while outside there are other women with their children (see

Figure 5).

Divine also painted her Sunday school, depicting how as children they would go to a smaller annex of the church, while adults prayed in the big church. Both paintings are notable for the thick walls and sturdy rooves of the buildings. Some participants chose to make artworks of objects associated with feelings of safety. Both Alizia and Divine made images of cassava grinding pots using paint with feathers and wool. In a later workshop, Alizia made a bright red painting of her hand, commenting: “I paint my hand. My hand is special. I burnt my hand. It is special because I cook nice food with my hand for my family; I cook cassava, mixed with palm oil”, Alizia (Democratic Republic of Congo).

3.2. Participation

In analysing respondents’ answers to workshop questionnaires asking how they experienced producing artwork in the group setting, researchers made a general assessment regarding clients’ engagement with the participatory element of the programme. In terms of the experience of creating artworks, all participants, without exception, gave positive responses, for example, it was a “very, very good experience”; “very, very nice, I don’t want it to stop” Akram (Iraq); “really useful” Hiruni (Sri Lanka); “inspirational” Mahamadou (Democratic Republic of Congo), “It is taking my memory back. You give me a space to think for myself and that is better” Divine (Democratic Republic of Congo).

Participants were confident from the start in the process of creating art. The “warm-up” encouraged participants to adopt an experimental approach on large shared sheets of paper, and to test their own ways of creating collage and painting. Sharing large sheets of paper helped participants overcome anxieties about making mistakes, or lack of expertise. The approach was empowering and participants quickly made artworks they felt were significant. The “warm-up” was successful in generating a sense of community, one in which participants felt supported and safe. Notably, female participants, with one exception, were comfortable with soft fabrics and wools. In contrast, male participants preferred harder collage materials: stone, cork, and drawing with a ruler. In future, it may be useful to provide more building-like materials, such as miniature bricks. In later workshops, participants enjoyed using paints on individual ready-made canvasses. Large canvasses were the most popular, with participants adding collage to paintings. Researchers observed that the contained shape of the canvas appeared to reassure participants and encouraged their creativity. The participants worked alongside others of similar languages with an interpreter, who supported discussion of ideas and meanings of artworks in the group. This arrangement was effective in ensuring good communication between researchers and participants.

When identifying potential participants for recruitment, FfT therapists suggested inviting clients to take part who did not attend many other activities at the centre. Consequently, it was interesting to note several responses in questionnaires where clients clearly valued the participation with others, “I feel good to do art together with other people. The people inspired me to get out again”, Alizia (Democratic Republic of Congo). Fahad described the experience, “Positive, helped me feel confident and comfortable among others (…) it is a good distraction, it also helped me to socialize and mix with others”, Fahad (Iran). For some participants working together, sharing ideas and the stories behind their artworks was an important part of the participatory experience. Mahamadou found the experience, “very motivating, because we exchange ideas” Mahamadou (Democratic Republic of Congo); similarly Alizia explained, “We work together, inspire each other and friendly people” (Democratic Republic of Congo). Errolvie and Chathura made similar points regarding sharing their stories, “Very motivating as we were sharing stories behind our drawings”, Errolvie (Democratic Republic of Congo). Others echoed these sentiments, “Very interesting, because we discuss what is very special behind our drawings”, Chathura (Sri Lanka). Many participants were disappointed the programme would not continue for longer, “We would like more, it is good for us. I make art about my country, my home, my city. I feel sad because of so many bad memories. But I feel good to do art together with other people” Alizia (Democratic Republic of Congo).

3.3. Recovery and Reconnection

In Herman’s theory, the three stages of recovery from trauma are not distinct and separate (

Lamb 2017, p. 59); their elements might overlap, there are advances and setbacks. Stage two, remembrance and mourning, and stage three, reconnection, are not necessarily linear in progression. An analysis of the data collected by the research team from workshops 2, 3, and 4 indicated all participants (N = 14) explored remembrance of place in their artworks (N = 30), and recorded comments to this effect in questionnaires (N = 22) and in discussion (N = 18). In terms of mourning, it is difficult to gauge from the artworks whether mourning constituted an element of subject matter. However, recorded comments indicated that the activity of making artworks of remembered places provoked feelings of mourning expressed as “nostalgia”, “sadness at loss”, “grief”, “missing family/place/warm sun/flowers/fields” (N = 34). Reconnection was identified by the research team in two ways: artworks depicting lives lived in the present (N = 5), see below, and recorded comments indicating reconnection with the world and with others (N = 4), for example, “making art helped me feel confident and comfortable among others” (Alizia).

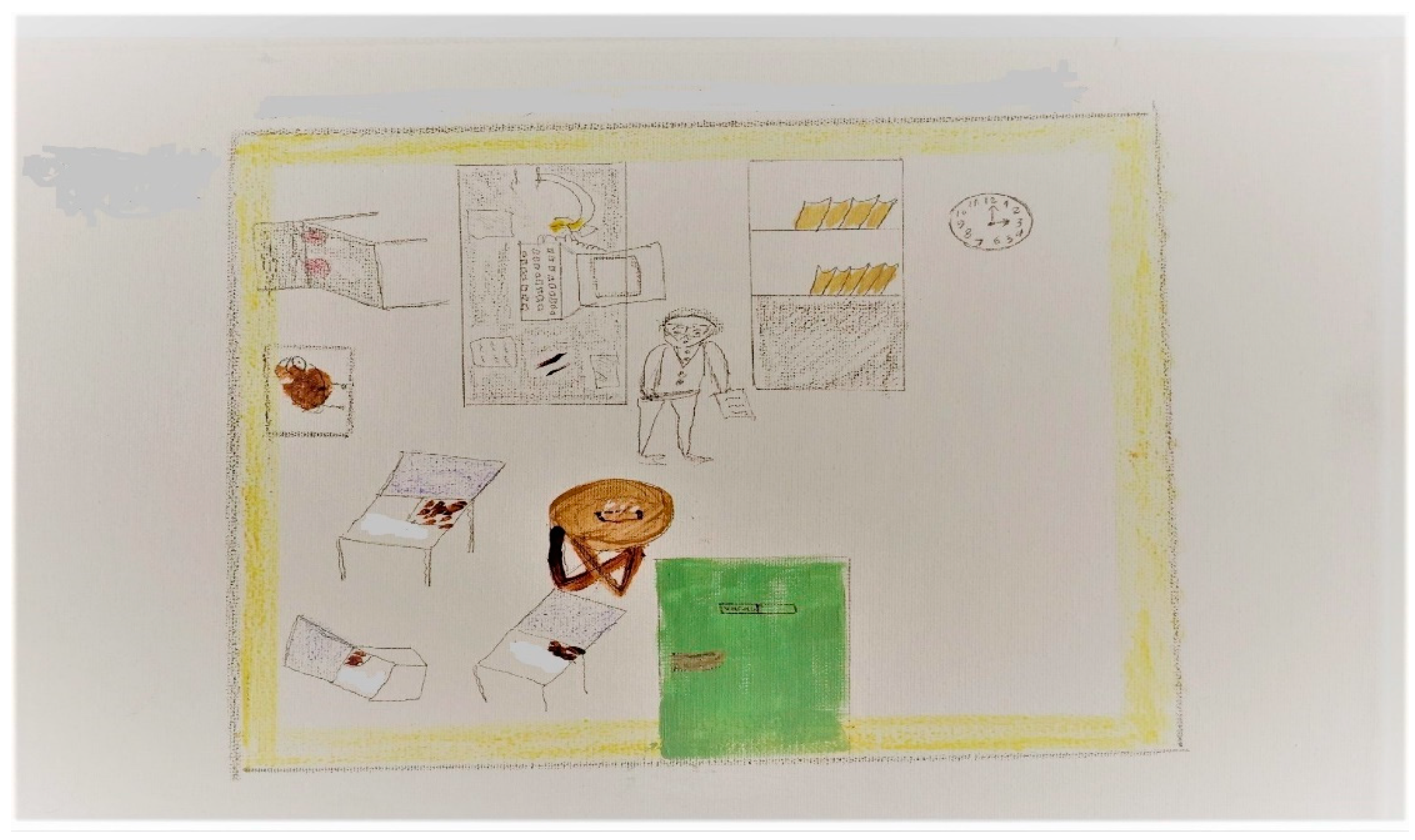

The workshop design sought to minimise the possibility of re-traumatisation in the workshops by enabling clients to work at their own pace and by encouraging artworks that drew on the present as well as the past, allowing participants the choice to avoid subject matter that could prompt difficult memories. This process highlighted the points of overlap between these stages of recovery. Interestingly, the artworks based in the present appeared more as signs of reconnection, rather than avoidance of difficult memories. Production of these artworks occurred in W.4. after individuals had already made artworks of remembered places. The subject matter of artworks based in the present represented places encountered in ordinary life, suggestive of the individual reconnecting with the world around them. For example, the participant Mahamadou depicted remembered places in W.1 and W.2: a pick-up lorry he could no longer drive, a banana stall selling fresh bananas he could no longer eat, in a city he could no longer visit. He particularly mourned the fresh bananas. In W.3 and W.4, he depicted places in his present life: a local church where he found solace in prayer and conversations with the priest and a football pitch where he regularly enjoyed playing football. These images of life in the present suggest some degree of integration of the trauma into a new narrative of self and personality. Similarly, Alizia’s bright red painting of her hand connects the injury she sustained in the past with the positive activity of cooking cassava for her family in the present. In an early workshop, Akram (Iraq) depicted an idealised image of a beautiful tree, surrounded by sunshine and blue skies, the image decorated with small pink roses, indigenous to his home country of Iraq. In W.4, using a ruler and sharpened pencils, he carefully delineated his psychotherapist’s room, where in his present life he received treatment. Every detail meticulously rendered, the clock at the appointed hour, the position of the chairs, his interpreter, the desk, the computer, a cushion, etc., and above the artwork it says “

the best place in my life”. To the question of whether it is useful for Akram to remember this place when stressed, he replies “

sure, all the time in my mind”. To the question of whether the experience of making art has changed him in any way, he says “

Sure, because every time I look at my work on my phone or at the wall I feel happy” Akram (Iran) (see

Figure 6).

The research team interpreted artworks of lives lived in the present as representative of the individual reconnecting with the world around them. As such, they correspond to Herman’s stage three, reconnection, indicating a level of recovery that enables survivors to connect with the changed person they have become. As described earlier, therapists working with survivors of torture understand this form of reconnection within a process of recovery as one where autobiographical identity integrates the trauma into a new narrative, enabling survivors to live in the present (

Lamb 2017, p. 59).

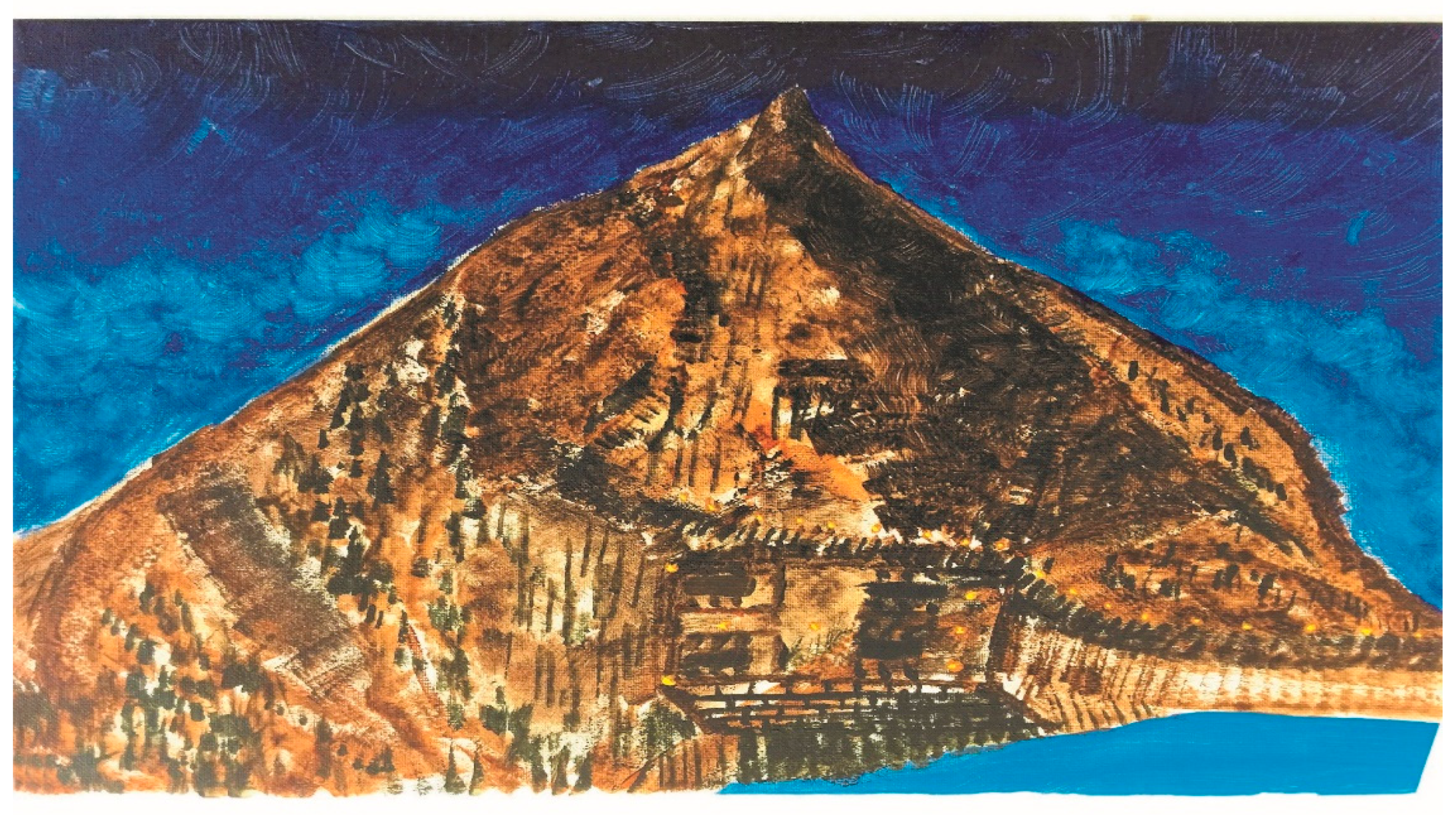

In exploring the potential of engagement with place to contribute toward recovery, we noted some relevant comments made by participants that suggested that the act of creating artworks was an expression of their recovery process. For example, Fahad (Iran) painted a restaurant in the lee of a mountain facing a lake. It is night-time, the sky is dark, and small twinkly lights illuminate some of the way to the summit. Fahad tells us that for a time he could only go out at night, but he has walked to the top, he says it is a beautiful, quiet place (see

Figure 7). He says, “

I have been to this place in the past and going there always made me feel happy. Remembering it now makes me feel sad and happy now”. Harnessing conflicting feelings, Fahad was able to explain that making the artwork in a group was “

Good, made me feel better” and “

I feel relax and comfortable”. In terms of Herman’s second and third stages of recovery, Fahad’s painting and his comments suggest remembrance, mourning, and reconnection, the components of recovery.

Many participants commented that it was useful for their recovery to remember places from their country of origin. Data findings from observation, field notes, and photographs indicated that the majority of participants were motivated to represent places precisely, whether this was mixing a specific colour or achieving structural accuracy. For example, Fahad had to have exactly the right black before he would paint the earth and the sky, Akram the right pink for his Iraqi Rose, and Mahamadou, Tharindu, and Akram insisted on using a ruler and sharp pencils to draw their image before they would use colour.

As researchers, we interpreted that the participants’ requirement for precision and their great concentration during the artmaking period reflected the personal significance of their images. They cared a lot about how their special place was expressed to themselves and to others, suggesting to us that they closely associated those places with their identity. Remembrance and expression of places connected to personal identity also arose in participants’ paintings of villages associated with their family’s history, or their childhood home, even if they and family members no longer lived there.

When considering whether these images contributed to recovery, Chathura answered, “Yes, I feel relieved because I am expressing what I have within me”, Chathura (Sri Lanka). The research team observed that participants’ artworks expressed a strong sense of cultural identity and historical rootedness. The project enabled them to connect with a deeper place related to their identity, a safe place, and potentially a healing place within.

4. Conclusions

The research drew upon

Herman’s (

1992) three-stage model of recovery from trauma to provide a qualitative thematic analysis of written, visual artwork, and observational data, and its interpretation. Researchers identified primary codes based on Herman’s theory of recovery in terms of remembrance, mourning, and reconnection, and were able to interpret that the participants’ engagement with these elements supported a trajectory of recovery. Secondary coding identified two sub-themes, namely, the participants’ experience of transition between their homeland and the UK, and new social connections. Data analysis of these themes enabled researchers to infer that participating in a group making artworks of places associated with safety may contribute to processes of transition and social connectedness. This combination, we suggest, indicates that this model of participatory art has the potential to contribute toward feelings of well-being and a trajectory of recovery for refugees who experience trauma.

The artworks produced by some participants across the four workshops appeared to provide a visual microcosm of this transition from past into present, from remembrance and mourning, to reconnection. For these individuals, artworks in early workshops were characterised by images of remembered homelands with mixed feelings of nostalgia, loss, and attachment to place. Artworks in later workshops tended to depict images of present places encountered in ordinary life, suggestive of the individual reconnecting with the world around them. Herman’s model of recovery would suggest that artworks representing life in the present indicate the individual is integrating trauma sufficiently to be able to envisage the start of a new narrative of self and personality, and able to project that identity to others. For other participants, the focus centred on the remembrance of places from their homeland associated with their identity, and the mixed feelings generated by these memories. These participants may have potentially connected emotions they felt in the present with memories of the past, and this process may also support recovery.

In developing this idea, the project Art of Recovery explored how artmaking involving the expression of remembered safe places might contribute not only to early phases of recovery, but also to later stages of transition, to connecting and building a relationship with a new environment. Through processes of remembering a safe place and its visual realisation, participants reconnect with a place, connecting their past with their present, and express their past and present selves to themselves and to others. Conceivably, these artworks serve as physical symbols through which participants connect their past with their present self, prompting self-understanding, and potentially understanding of others.

The study found that the process of creating art in a group was helpful in counteracting a sense of individual isolation, with the potential to enhance feelings of personal growth and supportive of transition to the new environment. In this respect, a particularly useful feature of the research design was to group individuals with others speaking similar languages, enabling a sharing of experiences. Indeed, some participants noted that usually they would not have met and talked with others and that the workshops were important in terms of social interaction. This appears to be an important element in the success of the programme and is underscored by Burnett and Peel’s study (

Burnett and Peel 2001) highlighting the importance for refugees to make contact with people from their own countries, a significant step in enabling them to better connect with host communities.

Researchers and therapists observed that the workshops appeared to facilitate participants in making artworks that they felt had significance in terms of their experience. They seemed to enjoy the opportunity to create and express themselves in artmaking, particularly for those with, as yet, little or no English. Such findings prompted researchers to understand the significance of participatory art in revealing memories and emotions not always easily accessible or readily articulated into words, but conducive to therapeutic processes.

Through imagining place and its physical representation in art, the project explored the facilitation of participants in connecting with a safe place within themselves, held in mind in times of stress, a process that may contribute toward their recovery. Participants were seen to exercise considerable attention to detail with specific elements of their artwork, reflecting a strong mental image they sought to express. The artistic process appeared to reinforce the presence of a healing place within participants, both as a positive mental image and as external expression. As Akram said, he could now look at the photo on his phone and on the wall, and this made him happy.

A limitation of the programme was its brevity. Many participants requested sessions for a longer period and expressed disappointment when the programme finished. This also meant there was no time to follow up or reflect with the participants on the wider long-term impact of the intervention or evaluation of the benefits and challenges of participation. Psychotherapists working at FfT after the workshops finished were able to continue a discussion of the artworks, and the safe places visualized, with individuals and groups, and many of the artworks are exhibited on the walls of the centre. These strategies helped participants to keep these safe places in mind following the end of the project. However, limitations of the project will be addressed as we have now further funding to support a longer programme of participatory arts workshops to assess longer term impacts. Further research is designed to foster greater creative development, exploration of participants’ cultural differences, and deeper exploration of personal stories. Potentially, we aim to explore more profound, longer-lasting benefits and challenges of this kind of participatory arts intervention.

FfT was able to provide a safe containing space with which participants were familiar, they ensured clients taking part would find artmaking suitable at their stage of recovery, and they provided experienced therapists and interpreters throughout the workshops, all of which provided invaluable support, as did prior meetings between researchers and professionals during the design stage of the project. A reported benefit of these participatory arts workshops was their use as an adjunct to the therapeutic work of FfT. An important feature of participatory arts is its capacity to contribute to recovery in a large group, within a designated period. For example, participatory arts programmes can support less formal social interaction within the context of a shared activity, an aspect that is not part of one-to-one therapy sessions or purely social meetings. Thus, the workshops provided an opportunity for refugee participants to meet others, in the context of shared artmaking, who understood their situation, and this has potential to counter some social and emotional isolation. With its focus on remembrance of place, the programme fostered the sharing of stories and experiences visually and verbally, in ways that were creative and rewarding. In this way, the artmaking process provides some of the elements necessary to effect positive change in self and the production of a new narrative, necessary for reconnection and recovery.