Abstract

Gerald Chukwuma is a prolific Nigerian artist whose creative adaptation and use of media tend to deviate from common practice. This essay draws on his several avant-garde works on display at the Nnamdi Azikiwe Library and at the administrative building of the University of Nigeria Nsukka. These artworks are referred to as ‘paintaglio’ in this essay owing to the convergence of painting, and engraving (or intaglio) processes. This study therefore identifies, critically interprets and analyzes Chukwuma’s artistic inclinations—style, spirit, forms, materials, and techniques. This is in order to lay bare the formal and conceptual properties that foreground the artist’s recent paintaglio experiments. The study relies on personal interviews, literature, and images of Chukwuma’s works as data. Such experimental works which clearly express influences of ‘natural synthesis’ ideology are here examined against the backdrop of their epistemic themes.

1. Introduction

Nigerian artist Chike Aniakor’s view of creativity as “the wandering of human spirit from one level of experience to another,” until it has secured a desired venting point lends credence to Dante Rossetti’s understanding that fundamental brainwork makes art unique (Aniakor 1987, p. 21). Without a concentrated intellectual activity, there would be no originality in art practice. This understanding has guided the creative experiments of Gerald Chukwuma, a Nigerian artist who seems to have grappled with the challenges of creativity as he has tried to re-invent painting and sculpture in a different visual language. We have chosen to refer to this avant-garde art as ‘paintaglio’ owing to its combination of colors and textures. Chukwuma’s paintaglio experiments are unique because of their tactility and heightened visual quality. Etymologically, the term “paintaglio” is derived from the words, “painting” and “intaglio” to express the application of color (paint) onto hollowed-out designs (intaglio). It was first used by Ola Oloidi, (a professor of art history and criticism, at the Nsukka Art School) in reference to Chijioke Onuora’s style of painting in which substantial part of his pyrographed works were painted over with oil colors (Onuora 2012) . Onuora, according to Nzewi “belongs to a pantheon of Nsukka greats; a select few of adept, experimental, and original draughtsmen” (Nzewi 2014, p. 43). Onuora’s works in this regard developed as a result of his skill in quick drawing. In order to move his skill to new frontiers he “went on to draw on board with the angle grinder” as a way of defining his subjects (Onuzulike 2014, p. 17). This approach to art making is clear in the work The Desire to Fly Again (Figure 1a), which represents Onuora’s other works, where pyrography is used to accentuate painted subjects. However, his use of color began in a subtle monochromatic instance (see Hangmen Also Die, Figure 1b), as he went on to advance paintaglio as a technique.

Figure 1.

Chijioke Onuora’s Paintaglios (a) The Desire to Fly Again, 2003; (b) Hangmen Also Die, 1995. Reproduced with permission from Chijioke Onuora. Photo by the Artist.

Paintaglio stands as one of the several results of exploratory approaches in modern and post-modern visual arts practice, which Obodo and Morgan described as “a game of search out” (Obodo and Morgan 2014, p. 1). In their work, David Cohen and Scott Anderson saw such method of creative inquiry as an ability of experimenting the environment with “keener visual sensibility” (Cohen and Anderson 2006, p. 10). Although there are limited texts around the works of Chukwuma, his style of working becomes defined in terms of use of materials and processes. Like El Anatsui’s wall sculptures, they draw materials from recyclable discards (Houghton 1998). Chika Okeke-Agulu’s description of El Anatsui’s works as a re-invention of sculpture, a style characterized by mark making, significantly applies to Chukwuma’s paintaglio experiments and those of other avant-garde artists of Africa whose techniques and media express diverse visual languages (Okeke-Agulu 2010). Moreover, several Nigerian artists have become more sensitive to the ideas, materials, and processes of art making that deal with the burgeoning socio-cultural issues of the people, such as ecological crises, militancy and insurgency, education, and politics, among others. The iconographic representation in Chukwuma’s works primarily derives from the indigenous visual idiom of uli, an Igbo traditional graphic system, whose use has attracted wide investigation from scholars in Nigeria and beyond. The literary works of Ikwuemesi (Ikwuemesi 2016), Ottenberg (Ottenberg 2002), and Chukueggu and Onwuakpa (Chukueggu and Onwuakpa 2016) and many others on uli are quite useful in this context. On subject matter, Chukwuma’s paintaglio experiments have found a link to those of Nkechi Nwosu-Igbo who has for about a decade now “consciously made her work to reflect on the education system in Nigeria” (Anya-fulu-ugo 2015, p. 36). Yet huge differences exist on the use of materials, style, ideas, and iconographic details.

Our concern in this essay, therefore, is to discuss Chukwuma’s new visual language of art that manifests paintaglio as a technique. Following their epistemic backdrop, his works in this regard are structured around struggle for self-discovery and survival. This study, then, sets out to answer the following questions: What produced such creative ideology and professional notches in Chukwuma? How has the artist used his work to drive his themes? How can we interpret the visual metaphors embedded in Chukwuma’s paintaglios? Relying on personal interviews, literature review, and visual data, this study underscores the profile and the pedagogical nurture of Chukwuma and influences that have spurred his exploration. It further carries out a visual discourse of his works.

2. Gerald Chukwuma and His Creative Orientation

Chukwuma Gerald (b. 1973) has his roots in Oguta, Nigeria. After his secondary education in 1989, he enrolled in the University of Nigeria Nsukka to study for a degree in Fine and Applied Arts. His study at the Nsukka School (Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka) lasted between 1999 and 2003. While a learner, his works portrayed him as grappling with the challenges of creativity. This is evident in his Footprints, Six Feet Later, a painting that featured series of rectangles, lines, and images of lizards and stylized footprints which he exhibited in 2001 alongside his mates.

Although he specialized in painting and was not tutored directly by El Anatsui, who was teaching sculpture at Nsukka School at the time, Chukwuma maintains that the well-known African artist inspired him greatly. He clearly avers that Anatsui “fanned into flames” the fire already lit by his teachers in painting—Krydz Ikwuemesi and Chike Aniakor (G. Chukwuma, personal communication, June 2015). How the fanning exercise by Anatsui took place is not clear, yet it is obvious that extrovert Chukwuma as the representative of his class, had had personal contact with El Anatsui and his works within the four years of his study. Although he mentions Anatsui, Aniakor, and Ikwuemesi as those who made remarkable impacts on his art practice, it is certain that the experimental spirit of ‘natural synthesis’ manifested through Uche Okeke’s uli at Nsukka School remained operative in many post-war graduates of the academy. It is necessary therefore to highlight briefly the connections and influences of ulism and Anatsui, whose subtle but pervasive influence on the artist is evident in Chukwuma’s paintaglio experiments.

2.1. Uli and Exploration at Nsukka

Uli primarily was a means of decorating the body among the Igbo, especially among the women. Applying the uli design on the body, with or without uhie (red camwood) was quite appreciable because of the prevalence of nudity at the time. Different types and styles of uli existed and so were occasions that informed its application (Willis 1997). It was also used in mural painting. In the 1960s, and after the Nigerian civil war, the tradition of using uli as body and wall decoration began to decline as the grip of Christianity and modernity on local tradition became tighter, only to begin a new history in formal art at Nsukka. Captivated by the Igbo uli, especially for its varied motifs, “underlying logic …, brevity of statement, and masterly control of space”, Uche Okeke started to explore uli art in 1962 although his first stance towards uli was in the 1940s (Oloidi 2016, p. 4).

Moreover, the exploratory approach to art (at Nsukka School) derives its force from a creative reaction of a group of student-artists at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology, Zaria (later Ahmadu Bello University). Adopting the name Zaria Art Society, the group comprising Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Bruce Onobrakpaeya, Yusuf Grillo, Simon Okeke, and Jimoh Akolo chose to ‘rebel’ against prevailing occidental tradition of art pedagogy of the time because they considered their indigenous tradition equally rich, diverse, and capable of being explored alongside foreign traditions. The group was headed by Uche Okeke between 1958 and 1960, the period Nigerian elites drummed for and experienced the country’s independence. As “the rise of modern art in Africa is closely connected with [the] region’s struggle for independence” (Frank 2006, p. 453), the rationale behind the ‘rebellion’ was to gain ‘independence’ of some sort, to institute an art practice that would be premised on localization of art curriculum. According to Chukueggu and Onwuakpa:

Of the uli experiment, Ottenberg wrote: “Ulism may be at the core of most Nsukka artists’ work, but their expression is varied” (Ottenberg 2002, p. 19). With uli and other indigenous idioms, art practice in Nsukka School became more robust while boundaries that once separated genres of art became more and more blurred. This ideology has undeniably influenced Chukwuma’s art practice.Uche Okeke’s contribution to contemporary Nigerian art is his active role in fostering of the culturist tradition particularly in several budding artists while at Nsukka School. Hence the style or trend presently identified with the school is majorly his handwork(Chukueggu and Onwuakpa 2016, p.267).

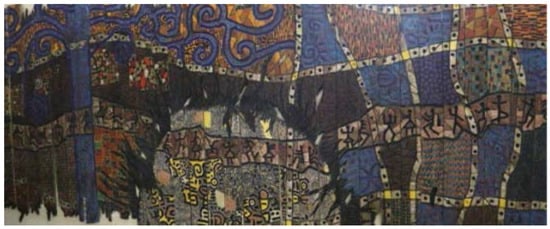

In his creative experiments, Chukwuma turns wooden panels into platforms for engraving and organisation of elements of design. This results in colorful compositions of two-dimensional design and relief (paintaglio). For instance, the Narrow Way (Figure 2) shows the system of design typical of Chukwuma’s several paintaglio experiments. Appearing as an appliqué, Narrow Way reveals indigenous signs, ideograms, and motifs in bright and harmonious tones.

Figure 2.

Narrow Way, 2013. Mixed media, 38 × 65”.

Reproduced with permission from Gerald Chukwuma. Photo: Trevor Morgan.

First, it is clear that Chukwuma is one of the several Nsukka-trained artists who has continued the cultural experimentation on uli. More so, we see an engagement and reinterpretation of indigenous idiom in a contemporary art practice different from its original usage. However, this emerging visual language in paintaglios, corroborate El Anatsui’s view that presenting the same old materials in new ways is what has ensured continuity in art practice (Onuora 2001, p. 93).

3. Gerald Chukwuma and El Anatsui: Parallels and Peculiarities

While Chukwuma and El Anatsui share certain creative parallels in their works, there are certain points of uniqueness for each of the artists. El Anatsui trained and practiced in Ghana before he left for Nigeria to join the faculty of Nsukka Art School in 1975. Although the change of environment originally affected his access to “ready-made wooden trays” he used to “burn, paint, engrave and sculpt” in Ghana, this change afforded him the opportunity to work with Uche Okeke (Oguibe 2010, p. 25). Such contact and subsequent relationship made Anatsui incorporate signs indigenous to the southeastern Nigeria such as uli, and nsibidi, in his works. Previously, Anatsui had appropriated adinkra and other visual signs common to some communities in Ghana. In 1995, for instance, he created a piece from an old mortar formerly used in extracting palm oil. The sculptural piece he called Adinsibuli Stood Tall features uli, circular patterns of Adinkra textile patterns and nsibidi ideograms together. These indigenous signs and symbols are heterogeneous, having come from different parts of Western Africa. In the 1980s or even earlier, Anatsui’s wooden sculptures featured these symbols in form of heavy charred intaglio lines or painted signs. On the instance of use of color, his early 1990s works fashioned with “different power routers, drills, and rotary saws” were also embellished with acrylic and tempera (Okeke-Agulu 2010, p. 41) as can be seen in his Earth-Moon Connections produced in 1993 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

El Anatsui. Earth-Moon Connexions, 1993.

Reproduced with permission from El Anatsui. Photo: Franko Khoury.

Owing to the creative success recorded by Anatsui, his influence spread across a good number of artists within and outside Nsukka School. Yet, Chukwuma does not readily come to mind when considering Anatsui’s disciples. This informed why Chijioke Onuora did not capture him in the series of progenies of Anatsui’s creative styles (Onuora 2001). However, it is interesting to note how Chukwuma had followed Anatsui as an exemplar in pyrography, perhaps from a distance. Chukwuma, moreover, noted that over time he has created a rather different way of expression. He wrote:

A close look at Anatsui’s Earth-Moon Connexions (Figure 3), Chukwuma’s The Narrow Way (Figure 2) and Everyone (Figure 4) reveals certain similarities. As a point of difference, it is evident that Anatsui has applied color more scarcely in his style of works done on wood with power tools. Anatsui’s motifs in planar wood reliefs or metallic wall hangings are both less varied and more repetitive (Kwame 2010, p. 72). On the use of material, Chukwuma fastens pieces of aluminium with striking colors to enclose and embellish surfaces more unlike Anatsui who rather creates all-over repeat composition in his wall sculptures. In general, we see Chukwuma has pursued a more pronounced color finish than a diminutive found in Anatsui’s wooden works. On the other hand, while we cannot effectively group Chukwuma’s works with Onuora’s, which are more pronouncedly paintings, the three artists share similarities in technique and materials. However, Chukwuma’s paintaglio experiments are more stratified.People often see a striking resemblance between the work of Africa’s most famous contemporary artist Professor El Anatsui’s wooden slats and that of mine. While I never studied directly under Anatsui (He taught sculpture and I graduated with a degree in painting), I was nevertheless influenced by his works and give credit to the great teacher’s impact in my seminal wood pieces… From this vantage point, it is exciting to see how my color and technique, coupled with this bold style has matured into a distinct expression of its own(G. Chukwuma, personal communication, December 28, 2016).

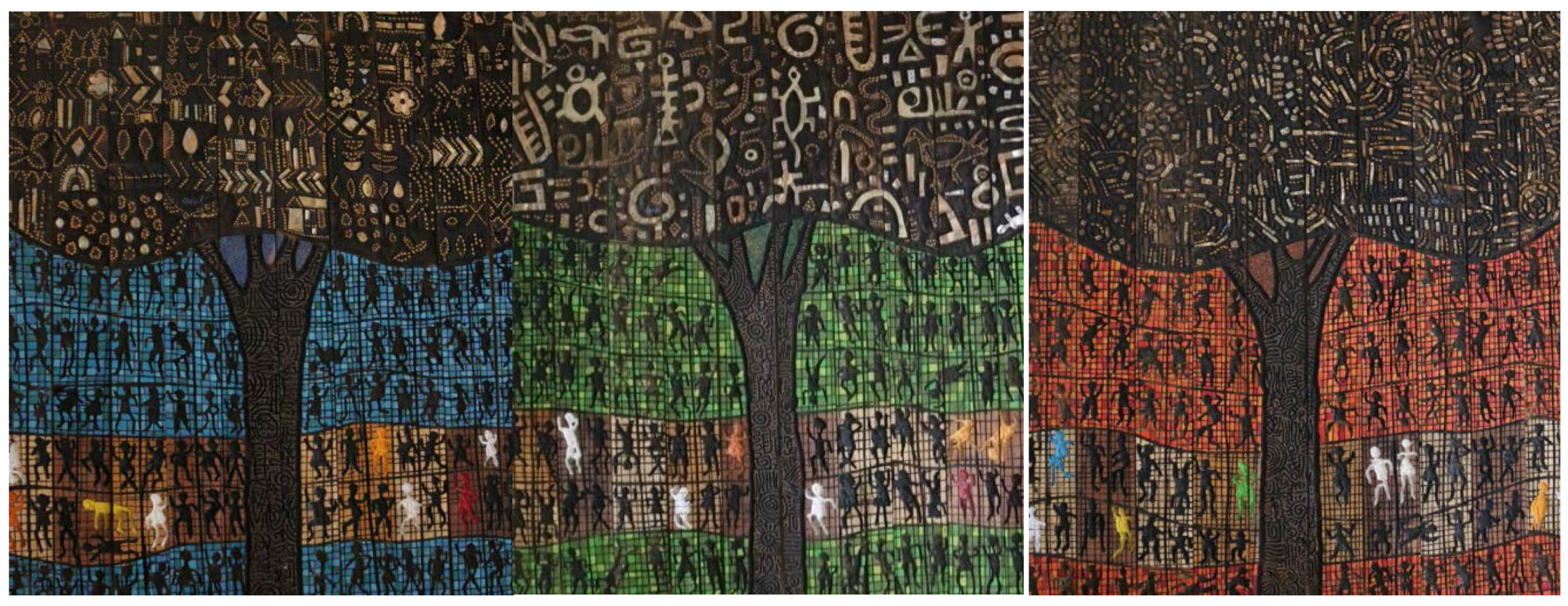

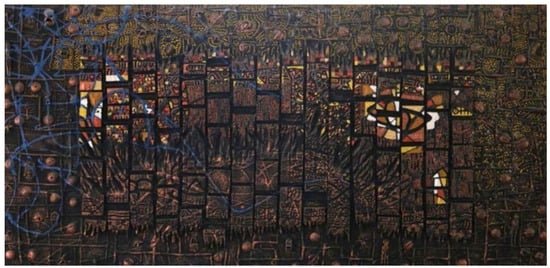

Figure 4.

Everyone, 2013. Mixed media, 85 × 162”.

Reproduced with permission from Gerald Chukwuma. Photo: Trevor Morgan.

4. A Visual Discourse of Chukwuma’s Paintaglio Experiments

Motifs and symbols in Chukwuma’s works similarly functional as ideograms and motifs used in Anatsui’s hangings resonate with African identity and heritage. Chukwuma says, he is “fascinated by motifs and symbols” for the “purpose they served in their times and their historical significance” (G. Chukwuma, personal communication, December 28, 2016). This informs why he profusely applies them to his works. Engraving indigenous signs and symbols in wood panels with care derives from his skill to handle mechanical and manual sculpture tools such as the router, angle grinder, gouges, and others. This helps him unveil imageries latent in woods—by subtracting non-essentials to create desired shapes, forms, and patterns.

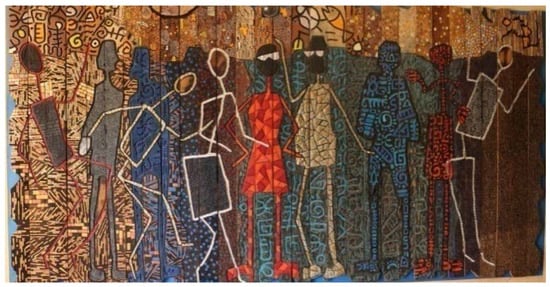

Marking the visual symbolism inherent in his style, Chukwuma’s works are finished with elaborate dots, ‘pixels’, lines, space, and forms, which are either pierced, incised, appended, or painted. We see in his works imageries that are not in any way divorced from the linearities and intricate ornamentations that characterize the uli system of design. He moves his shapes and forms around in rhythmic flows for creative effects. Although some critics may think him eccentric, examining the creative superimpositions that have defined the experiments, it is clear his ideas and visual forms drive a significant theme for Nigeria, today. In a personal communication, Gerald stated:

His theme of knowledge is premised on the principle of self-discovery and struggle towards self-realisation. This time, the struggle is not all of political and economic powers, nor between the ruling class and the working class, rather scholars are poised in the struggle for academic power in order to enjoy a better social and economic life. The common ideology and notion of Africans as constantly in competition and struggle for survival as underscored in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart tends to find expression in Chukwuma’s works (Chinua 1958). In I Know Where the Sun Lives, (Figure 5) the artist expresses the concept of self-discovery of individual ability for an adorned future. The Socratic principle “man know thyself” is underscored here to provoke an intensive search into the personality and potentialities of the individual. In a corroborative standpoint, Borgdorff argued that “art’s epistemic character resides in its ability to offer the very reflection on who we are, on where we stand” (Borgdorff 2012, p. 154). The reality of identification of knowledge agrees with Chukwuma’s views. In I Know Where the Sun Lives, we find representations of the sun, human figures, stylized tree, regular horizontal and vertical lines, uli and nsibidi motifs and other symbols. This is a visual metaphor expressing the open and diverse routes to self-realization, howbeit, to be actualized within the framework of discipline and industry. Chukwuma represents, as central in his work, the imagery of the sun—a figurative expression for the highest point of possibility—and as the nucleus of life, the sun here is personified and perceived as the source of power, light, vision, and that which pushes darkness of ignorance away.When I was commissioned to do the pieces at the University of Nigeria Nsukka, which by the way took two years to accomplish, I had to work around a theme. The narrative had to go around the concept of knowledge, education, university, and their impact on people. Therefore, all the titles and messages had to reflect the theme(G. Chukwuma, personal communication, December 28, 2016).

Figure 5.

I Know Where the Sun lives, 2013. Mixed media, 71 × 167”.

Reproduced with permission from Gerald Chukwuma. Photo: Trevor Morgan.

On the broad horizontal channel in this work, we see human figures traversing the stellar space in various postures, some expressing as it were, relief, happiness, tension, challenge, or heat caused by the sun, perhaps. Chukwuma, conceivably, wants to redirect his audience who undertake the journey of life to the true ‘source‘. While pushing his materials and ideas around, he lays bands of metal in a curvilinear patterning to create irregular spaces, perhaps to reveal how chequered life can be. The work is enlivened by punctuated spaces and intricacies of line and dots with an application of subdued tones in shades of blue, gray, yellow, and red. In a formal analysis of his message of knowledge and self-discovery, the choice to experience the sun lies open to anyone and everyone—to create, to invent, to make discoveries and breakthroughs if we dare to exploit the resources and materials provided by nature or man.

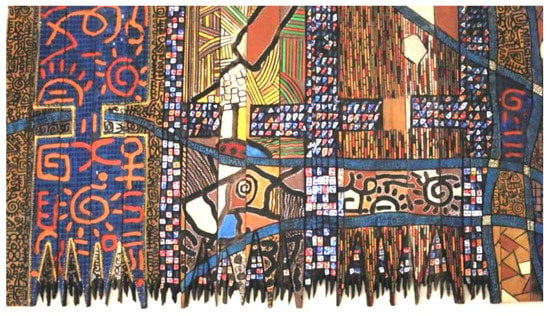

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Chukwuma’s titles have expressed certain ‘spirito-centric’ persuasions that draw ideas from biblical narratives to support his epistemic themes. In using light as a metaphor, he marks out areas of bright colors in Light out of Darkness (Figure 6) similar to I Know Where the Sun Lives. Thus, calling to mind the historic statement, “Let there be light,” made by God to bring illumination on the dark formless entity of the universe in the biblical account of creation. By using bright and warm hues of white, yellow, red, orange of shapes and dots Chukwuma in Light out of Darkness activates two points of entry from which the “light” begins to emerge. This chimes with the Socratic viewpoint that education is the kindling of a flame, and not the filling of a vessel. In its organization, the work shows a highly-pixilated body, saturated with intense visual textures, designed on its border with broken pieces of ropes, round metals, dolls, combs, padlock, and toys or assorted representations of animals and objects.

Figure 6.

Light out of Darkness, 2013. Mixed media, 48 × 96 × 3”.

Reproduced with permission from Gerald Chukwuma. Photo: Trevor Morgan.

Following the religious undertone of his theme, the deep tones of the work symbolize darkness of ignorance and negatives that becloud dreams and purposes, which education and enlightenment should eliminate. The same message of responsibility in self-discovery is also locked up in Everyone (Figure 4) the piece with which Gerald, argues that “anyone and everyone is able to tap knowledge when he chooses to open a book” (G. Chukwuma, personal communication, December 28, 2016). The whole essay is condensed to a relief of graphic design. Stylized rendering of matchstick human figures of both genders are represented in varied postures of leisure, work, labor, study, and freedom with which academic settings are known. Composed of 30 pieces of wood slats, the work is mounted at the right flank of the entrance to the largest library in West Africa, the Azikiwe Library for its didactic role. Here we see a humanistic sensitivity that mirrors self. Chukwuma believes in individual capability to ‘locate’ where his sun lives and to tap from its enlivening energy. In a more applied sense, his themes go on to refer us to the questions of materialism, which raises profound challenges for scholarship in Nigeria. Although his themes make a point for the emancipation of the individual through education, the view on materialism foregrounds the situation or context in which people tend to seek for knowledge in Nigeria today in pursuit of higher and revered class. Certificates are seen as mere meal ticket, perhaps, owing to harsh economic realities that becloud the nation. Hence, students, graduates, and employees are willing to engage in even severe malpractices to secure rankings, jobs, and promotions (Falola 2017).

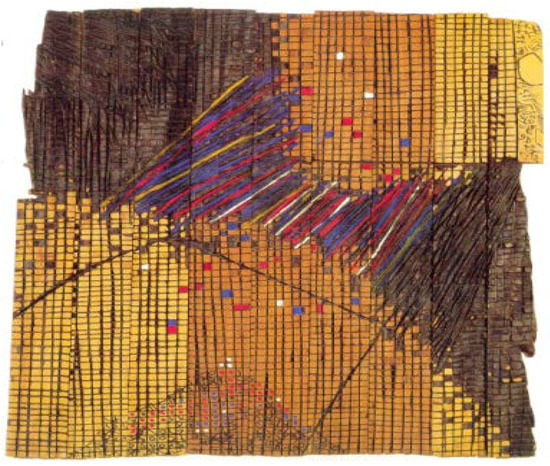

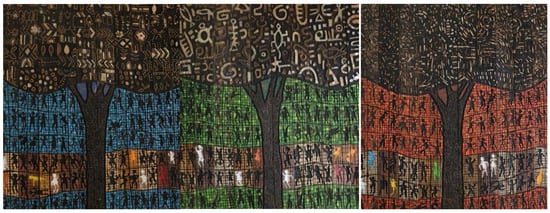

He speaks of his ideas, concepts, and their underpinnings as projecting hopefulness for those who dare, of optimism placed under the reality of choice. For instance, of the Tree of Life (Figure 7) Chukwuma explains:

The Tree of Life is not a triptych as it seems, rather it is a band of three distinct works with identical layout. Each work, consisting of 10 panels, features a towering tree at the center, that dwarfs and overshadows engraved miniature figures in silhouettes. Appearing in rows are these figures in varying positions, framed vertically and horizontally. Some stand, others wobble or fall, perhaps in pursuit of wisdom or knowledge from Tree of Life. The varying color of these figures from black to white, yellow, red, and green seems to capture the cultural diversity that defines the identity of the entire learners’ population.This piece talks about the benefits of wisdom and understanding. (Proverbs 3:13–18, KJV): Happy is the man that findeth wisdom, and the man that getteth understanding. For the merchandise of it is better than the merchandise of silver, and the gain thereof than fine gold. She is more precious than rubies: and all the things thou canst desire are not to be compared unto her. Length of days is in her right hand; and in her left hand riches and honor. Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace. She is a tree of life to them that lay hold upon her: and happy is every one that retaineth her(G. Chukwuma, personal communication, December 28, 2016).

Figure 7.

Tree of Life series, 2013. Mixed media, 54 × 60” each.

Reproduced with permission from Gerald Chukwuma. Photo: Trevor Morgan.

5. Conclusions

In Chukwuma’s works, we have found a unique union of painting and intaglio, otherwise referred to as paintaglio. Although the formal properties of the works are premised on the ideology of “natural synthesis”, one sees in them an innovation in techniques and materials that aligns with Anatsui’s, of which Robert Storr concludes that if such works open “a new chapter in the history, it is the most pictorial sculpture imaginable” (Storr 2010). Chukwuma drives a continuum of the same indigenous African creative paradigm with his sculpturesque paintings. Following that artworks are iconographic archetypes charged with meanings, Chukwuma’s experimental works could be read or interpreted from diverse perspectives by general audience and connoisseurs. Beyond structure, texture, and visual effects of these paintaglio experiments, their underlying theme of knowledge framed around self-discovery and struggle for survival is worthy of note considering the status of educational development in Nigeria. Moreover, our reading here is pertinent, for Africa and her Diasporas, now that the politics of education in Nigeria has a tremendously materialistic focus. Furthermore, the study has underscored the ubiquitous demand for self-discovery as a precursor to global discovery and advancement. More innovative inquiry in art practice in which materials, ideas, and processes of working interlace is required, especially with foci on developing issues around the African people.

Acknowledgments

No funding was received for this research work. We appreciate Gerald Chukwuma for the interviews granted us during this research. Our special gratitude goes to the reviewers of this work for their untiring spirit. We are highly encouraged by their dedication to making this work come out strong and mature.

Author Contributions

This work was conceived and designed by Trevor Morgan and Chukwumeka Nwigwe. Uzoagba Chukwnonso contributed in gathering visual materials while Chukwuemeka Nwigwe conducted communications with Gerald Chukwuma. Trevor Morgan was intensively involved in writing and editing of the work with support from Chukwuemaka Nwigwe and Chukwunonso Uzoagba.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aniakor, Chike C. 1987. Introduction to 2nd Annual Exhibition Catalogue, by AKA Circle of Exhibiting Artists (Hotel Presidential, Enugu, 23 April–May 25, 1987; National Gallery of Crafts and Design, Lagos, 2 July–16 July 1987), 67pp.

- Exhibition in Honour of El Anatsui and Obiora Udechukwu. (Nnamdi Azikiwe Library, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, June 4-July 8, 2015). Nsukka: Faculty of Arts, UNN.

- Borgdorff, Henk. 2012. The Conflict of the Faculties: Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. The Hague: Leiden University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chinua, Achebe. 1958. Things Fall Apart. Essex: Pearson Education Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Chukueggu, Chinedu C., and Samuel I. Onwuakpa. 2016. Natural Synthesis and Contemporary Nigerian Visual Arts: An Exposition of Uche Okeke’s Works. African Review Journal 10: 257–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, David, and Scott Anderson. 2006. A visual Language: Elements of Designs. London: Herbert Press. [Google Scholar]

- Falola, Toyin. 2017. Contemporary Challenges of Education in Nigeria. 1st Distinguished Lecture of the Faculty of Arts. Nsukka: University of Nigeria Nsukka. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, Patrick. 2006. Prebles’ Artforms: An Introduction to the Visual Arts, 8th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, Gerard. 1998. El Anatsui and the transvangarde. In El Anatsui: A Sculpted History of Africa. London: Saffron Books, pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ikwuemesi, Krydz Chuu. 2016. Eziafo Okaro: An uli woman painter’s tale in the Igbo heritage crisis. Cogent Arts and Humanities 3: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kwame, Appiah. 2010. Discovering El Anatsui. In El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You about Africa. Edited by Lisa. M. Binder. Washington: University of Washington, pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nzewi, Ugochukwu-Smooth. 2014. Chijioke Onuora: Nsukka Art School and the Art of Drawing. Chijioke Onuora: Akala Unyi, (The National Gallery of Art, Enugu,11 July-25 July 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Obodo, Eva, and Trevor Morgan. 2014. Visual Metaphor: Ekene Anikpe’s Sculptural Essays. International Journal of Research in Arts and Social Sciences 7: 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Oguibe, Olu. 2010. El Anatsui: The Early Work. In El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You about Africa. Edited by Lisa. M. Binder. Washington: University of Washington, pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke-Agulu, Chika. 2010. Mark-making and El Anatsui’s Reinvention of Sculpture. In El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You about Africa. Edited by Lisa. M. Binder. Washington: University of Washington, pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Oloidi, Ola. 2016. Uche Okeke: The Unchallengeable Pioneer and embodiment of Modern Igbo Uli Art Form. In Special Tribute to Master Artist Uche Okeke. Abuja: National Gallery of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Onuora, Chijioke Noel. 2001. Inspiration, Exploration & Installation: The Influence of El Anatsui in Nsukka Art School. In A Discursive Bazaar: Writing on African Art, Culture and Literature. Edited by C. Krydz Ikwuemesi and Ayo Adewunmi. Enugu: Pearls and Gold, pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Onuora, Chijioke Noel. 2012. Two Decades of Pyrography by Nsukka Artists (1986–2006). Ph.D. thesis, Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Onuzulike, Ozioma. 2014. “In Conversation with Chijioke Onuora”. Chijioke Onuora: Akala Unyi, (The National Gallery of Art, Enugu, July 11 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Ottenberg, Simon. 2002. Reflections on a Symposium and an Exhibition. In The Nsukka Artists and Nigeria Contemporary Art. Edited by Simon Ottenberg. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Storr, Robert. 2010. The Shifting shapes of things to come. In El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You about Africa. Edited by Lisa. M. Binder. Washington: University of Washington, pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Elizabeth Anne. 1997. Uli Painting and Identity among the 20th Century Igbo. Ph.D. dissertation, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).