1. Introduction

The book

Elizabeth Durack, Art & Life, Selected Writings (

Clancy 2016) presents a selection of writings of the Australian artist Elizabeth Durack (1915–2000) (

Figure 1). The selections are presented in chronological order as eight decades of chapters (1920s, 1930s, through to the 1990s) and the final chapter, 2000. The book gives an insight into days gone by when distances were spanned via lengthy letters, and some individuals confided in their diaries.

A considerable portion of this book comprises selections of Elizabeth’s diary entries and personal letters. There are some unpublished manuscripts and there are several essays (including a 1984 essay published under the nom de plume, Ted Zakrovsky).

To cobble together such a mischmasch to create a single coherent text is the task that the editor, Elizabeth’s daughter, Perpetua Durack Clancy, has embraced. She wisely leads each chapter with her own introduction.

I recall hearing Douglas Adams (author of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) explaining that: “the trouble with real life is that it lacks narrative structure”. This is the challenge that faces the compiler of such a book as Art & Life. We can impose some post facto narrative structure by reading this text as Elizabeth Durack’s journey from a childhood in Perth, through a life informed by experiences in the Kimberley outback of Western Australia, through to the denouement of Eddie Burrup.

2. Elizabeth Durack

Elizabeth Durack served a long apprenticeship in art, to finally graduate, in her 80th year, as Eddie Burrup.

Art & Life relates that journey in her own words. At one point, she writes of “words, not being my medium” (

Clancy 2016, 1954 letter, p. 77). She recalled that “Matisse, stung to retaliate at various times [against hostile critics], advised: ‘if you would reply, cut your tongue out—an artist should speak only with his brush’” (

Clancy 2016, 1954 letter, p. 79). She goes on to observe that Matisse did not follow his own advice. And neither does she.

She railed against an unfavorable review, writing of “The unfairness of it, the sheer meanness, the spitefulness” (

Clancy 2016, 1947 letter, p. 42). She visited a solicitor for a remedy. The advice was that she had no winnable case. Still enraged, she sought the reviewer’s address and took a taxi to his home, “He tried to be nice to me … Bernard Smith thought it was a terrifically daring thing to do” (

Clancy 2016, 1947 letter, p. 45). Otherwise, she reported “my very timidity, my very hesitancy, my modesty and reserve” (

Clancy 2016, 1947 letter, p. 43), and how she “waited 30 years before she dared put a picture in a frame, hang it on a wall, [and] price it” (

Clancy 2016, 1947 letter, p. 42).

We learn in

Art & Life that Elizabeth lived in Perth, Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, Alice Springs, Darwin, Broome, Hermannsburg (NT), Beagle Bay (WA), and various Kimberley cattle stations (WA). She reported that “for years the Aboriginals were … my everyday companions” (

Clancy 2016, 1961 letter, p. 96). She expressed her frustration: “Why is this: I have hung in three capitals now and not one of the national art galleries have come forward to buy” (

Clancy 2016, 1947 letter, p. 46).

Elizabeth wrote, with some exasperation, that to be a politically correct (PC) artist in Australia: “Maturity, perseverance, a long record of productive and consistent work are all serious handicaps and all such baggage should, if possible, be discarded or kept dark. An additional drawback is ever to have been stimulated to produce work that derives from a direct visual response to sight or scene”. She added that “It is an advantage if an artist does not happen to be a several generation Anglo-Celtic Australian” (

Clancy 2016, 1993 letter, pp. 187–88).

Elizabeth could be succinctly scathing. Critics were “these dopes and twerps” (

Clancy 2016, 1947 letter, p. 44), Christian missionaries were “Bible thumpers” (

Clancy 2016, 1954 letter, p. 75), a motel mural in Sandfire Flats (WA) was “really no worse than Nolan” (

Clancy 2016, 1981 letter, p. 154). Of the Queen’s speech in Broome (WA) she wondered: “wouldn’t you think that after all these years of practice she could rattle off a few words of innocuous pleasantries without reading from a sheet … You never heard such nonsense. It might have been a speech made by Queen Victoria … a hundred years ago … Still, it had the saving grace of being brief” (

Clancy 2016, 1963 letter, pp. 107–8).

Elizabeth had long felt the disdain of the Australian artocracy. She had many solo exhibitions; they had failed to win the acclaim that she sought and the national galleries of the country were not clamoring for her art. On a recent trip to Perth, I visited the Art Gallery of Western Australia, I asked to see the Elizabeth Duracks of the collection—none were forthcoming. Imagine, I am standing in front of them, in their gallery, at the so-called information desk, as an interstate visitor, yet I am advised that I should send an email to the gallery with my query and they would respond within the prescribed number of weeks! Elizabeth had a point. It remains sharp to this day.

Shortly after the death of her sister, Mary, in 1994 (16 December), a tsunami of creative energy was unleashed within Elizabeth Durack (from 28 December). Just when she might be expected to be hanging up her brushes, Elizabeth worked in a manic frenzy to create the masterpieces of her life.

At the age of 80 years, Elizabeth Durack channelled a burst of creativity into a suite of remarkable paintings. They are big, bold, brash, refreshingly different, and distinctively Australian. We might well exclaim, like the sommelier at the wedding feast of Cana: “But you have kept the best until last!” (after John 2:10).

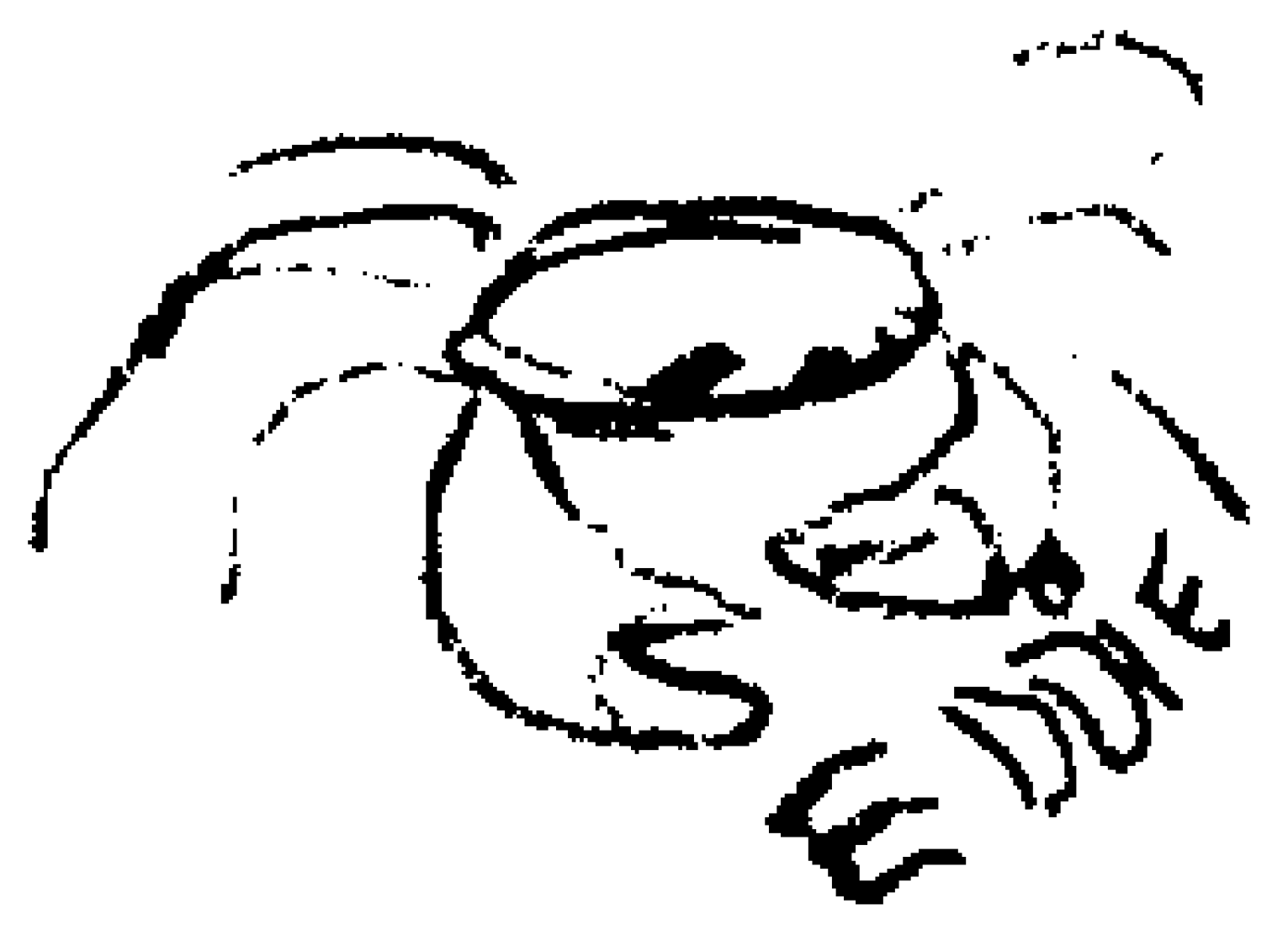

These new works are the apogee of Elizabeth’s life work. They were presented to the world as the work of a previously unknown artist named Eddie Burrup. Eddies are currents that run counter to the main currents and this Eddie ran true to type. Swept away by the Eddies was the cute sentimentality, bordering on kitsch, of Elizabeth’s early marginalia (

e.g., Durack and Durack 1935;

Durack and Durack 1940)) (

Figure 2). With those cherubic aborigines of Elizabeth’s past, she was perhaps at risk of being categorized along with Brownie Downing (1924–1995) as a creator of Aboriginal-themed kitsch. Downing had commercialized Elizabeth Durack-style ‘piccaninnies’ (

Durack and Durack 1940) into a prolific cottage industry of gift cards, porcelain plates, decorative plaques, children’s books and tea sets (

Higgins 1995). For Downing it was a marketing exercise. For Durack it was a lived experience.

The Burrup paintings are masterful and engaging (

Figure 3). This fresh burst of paint on canvas was neither cute nor quaint, neither sentimental nor illustrative, and it was writ large. Here was an envisioning of Australia as a playground for the spirits and totems of the land, here was a novel rendering of an ancient landscape, imbued with love, fun, humor and exhilaration. Elizabeth had observed what so many others had observed, and seen what no one else had seen. And now she was transferring those visions into a distinctive suite of artworks unlike anything that had gone before, for her or for anyone.

3. Eddie Burrup

Elizabeth continued to paint like a woman possessed. She painted unlike Elizabeth Durack. She painted as Eddie Burrup (

Figure 4). “As Eddie draws me deeper and deeper into his world I find myself becoming not only reluctant but actually resentful of putting him on the back-burner—or, worse, of having to turn off the jet altogether, while I draw myself back to old ED … She is boring; he is so interesting) (

Clancy 2016, 1995 letter, p. 197).

And so, she hatched the plan, with the hesitant collusion of her daughter Perpetua Clancy Durack, to present Eddie Burrup to the world. A backstory for Eddie was concocted (

Table 1). An early move was for Perpetua to present Burrup paintings to a commercial Melbourne gallery with the view to an exhibition. After the initial interest, Perpetua’s nerve failed, and she signaled to the gallery that Eddie Burrup might be a nom de plume—it was a declaration that understandably proved fatal to that line of advancement of the Eddie project.

Elizabeth wrote: “let us be fairly clear in our own minds just who Eddie Burrup is and what he is on about … his totemic brothers call to him to put them in to his paintings … to reposition and re-assert that time when the universe consisted of a shared partnership between all living creatures and life-forms” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 fax, p. 203). She writes of the Eddie Burrup phenomenon: “Yes, it is an experiment—not a hoax—not a crime. Think Professor Higgins and Eliza Doolittle—not Ern Malley—not Macbeth … Who knows what lies ahead for Eddie—he might never be exposed—who knows … I can’t really live without Eddie B now. He has become a part of me—Me—in fact. I can’t go on, or get on, without him. I know he is an antiquated version of Aboriginality” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 fax, pp. 205–6).

In a diary entry, she writes: “My great fear now is that Eddie will be lost to me … Broome a week ago at Easter where we were together so happily. How I loved sitting under the mango tree with him in the dappled shade with the brilliant sunshine splashing over the fresh buffel grass and on to the red ground while he told me of his life before we met—every moment drawing closer as we shared so much of past experiences and life in the north … When and how dare I call him up?” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 diary, p. 207).

She recalled that: “Eddie Burrup … first emerged with neither name nor persona and yet fully formed … He just arrived … These morphological works—what are they about? … I suppose they are actually about what I am about, all my life … but only now coming out in this particular form … These morphological works … are removed from the work I might exhibit or be asked for, or the work … with which I am associated … totemic ideograms … they found a focus through the eye and hand of Eddie Burrup” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 diary, pp. 216–17).

She reported in her diary that: “He works on every day with his drawings and is adding titles to them, fragments of ‘old blackfella stories’ or enigmatic jottings, a mixture of ancient myths and his own reminisces. He hasn’t tackled a bigger painting for a while. Perhaps he will over the weekend. … He has the idea that he will be having an exhibition … in September” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 diary, pp. 219–20).

Eddie was a demanding muse: “He is making it harder and harder, if not impossible, for me to do any other work than his. Nothing seems to hold my interest—every other form of expression seems dull and simplistic compared with the persistently intriguing ideas that Eddie keeps coming up with … If anyone has painted him or herself into a corner it is surely I” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 diary, p. 221).

With 40 works produced in his first ten months, Eddie was prolific: “Whither Eddie Burrup? God only knows. I have been working with him all day down in the rear studio. We completed a new composition … and then named most of the paintings and signed them with Eddie’s mark—a little rock crab—on the back (

Figure 5). There must be about 40 pieces there now. Some better than others but some very good … The work I have been doing, apart from Eddie, seems so tame and insipid … Eddie Burrup is the ultimate in a prison of the imagination” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 diary, pp. 221–22).

A year had now elapsed, and the artist was impatient: “It will be a year on December 28 since Eddie Burrup entered my life. And where in all that time have we got? The answer is—Nowhere. In fact, far from joyous liberation, the relationship has brought about a situation in which I am trapped, hoisted by my own petard, frustrated, thwarted. I did not think that, this time, it was going to be so slow … Both Eddie and I foresaw an exhibition in Melbourne in September … It would not be so bad if all my previous modes of activity had not now become so dull, depressing and tedious … I was functioning quite well on the two levels … Now I can no longer operate this way. Eddie is too demanding and too interesting” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 diary, p. 226).

By now, Eddie was preparing works for competition: “Eddie Burrup has been an incredible psychic stimulus to me and opened a whole Pandora’s box, not of evil spirits but, rather, a host of imprisoned and benign ones who were, previously, locked up in the dark confinement of my personal thalamus … Eddie does a drawing a day, title and all. He has done two paintings for the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Art Award 1996. They are among his best works to date” (

Clancy 2016, 1996 diary, p. 229).

The artist was yearning to share these new works: “Yesterday the sun came out and Eddie took the opportunity of doing a painting—Ladder to the Sky. This is the first time, ever, that he has used blue … We have no one to show it to or to talk about it to. Working on like this, forever in the dark, is just about killing us both” (

Clancy 2016, 1996 diary, p. 231).

With Eddies accepted into art exhibitions (see

Table 1), Elizabeth outed herself as Eddie Burrup (in 1997). There was immediate blowback from the ruse. It was hurtful to Elizabeth Durack. She wrote that “Elizabeth Durack and Eddie Burrup have no intention of going on the defensive about what has occurred between them. It is a private matter … for the present we plan to ride out this unseasonal storm … Life is short … Art is long (

Clancy 2016, 1997 letter, p. 237).

The controversy was a distraction. She took the view that: “The whole thing is a sort of conspiracy to stop me spending long uninterrupted days in communion with Eddie Burrup” (

Clancy 2016, 1999 diary, p. 248).

Elizabeth reflects on the themes of Eddie: “this artist and his particular frame of reference is a resource—one untapped until his work emerged, fully formed, late in 1994 … His visions are wildly eclectic—they range from Totemic Tumult (his central theme) enmeshed with the Ngarangani (the Dreaming), to random incident within historical times (the impact of the hoof upon the precinct of the paw being ever in mind), to fragments from the lives of the creation ancestors and the lives of the old stockmen … even Bible stories. The visions of Eddie Burrup are unpredictable … They are unified by a coda of their own and by the artist’s unique therianthropic ideography … the images swim up to me out of the silt of the past or when I hear the old voices re-echoing from what is now another and a lost world” (

Clancy 2016, 1999 letter, pp. 252–53).

Perpetua lamented: “As the work of Eddie Burrup, the paintings were applauded and hailed as those of a genius, as the work of Elizabeth Durack, the work was … vilified, maligned, defamed” (

Clancy 2016, 2000 panel discussion, p. 261).

The new millennium arrived. Four months before her death, Elizabeth reflected on: “the sense of loss and regret as I saw the old calendar fly past and along with it everything and everyone who had shaped what ever I was and what ever I became. There will be no more shaping for me … All my shapers are in the past now, in another century” (

Clancy 2016, 2000 diary, p. 257).

4. Conclusions

Elizabeth Durack was the apprenticeship of Eddie Burrup. It was an apprenticeship of 80 years, after which Eddie Burrup emerged to possess her, for her most prolific years, the final five years of her life. As an octogenarian, she produced her consummate masterworks. They are works that could not be taken for those of any other.

Art & Life presents, in her own words, the growth and development of an artist who spent a lifetime engaged with aboriginal Australia and with art. From the outset of her art career, there was some awareness that the path she was treading just might be contentious. The Dedication to “the black community on Argyle Station” in her first illustrated book,

All-About, states that: “You will never read this, for to learning you have no pretensions. You cannot sue us for libel, though we have exposed your characters, your secrets and your private lives. Forgive us! Our protection lies in your unworldliness … there is much that you can teach us that is not in the white man’s knowledge. Yours is the gift of laughter and human kindliness and true philosophy” (

Durack and Durack 1935, p. 5).

The bulk of Art & Life was not written for publication. There are personal letters and private diary entries. So most of the material in this book is new in print; reprinted items, such as several essays, comprise the minority of the content. Collectively they throw light on the growth and development of the artist.

It does not serve the artist to send her private misspellings into public print. An editor’s courtesy to an author is to protect the reader from the irritations of misspellings and the author from the ridicule of misspellings. It is not sufficient to reproduce a misspelling and flag it as such with ‘(sic)’. Retained incorrect spellings are a distraction in Art & Life. Examples include: aplomb (which appears as “a-plumb”, p. 28), niche (“nitch”, p. 109), hieroglyphics (“heiliogriphics”, p. 124).

Transcription errors also distract. For example: the artist surely means frizzy (rather than “fizzy”, p. 148), bunged (rather than “bungled”, p. 149), grist (rather than “gist”, p. 179).

The illustrations presented are in black and white and as such they do no justice to the art. For black and white reproduction, should there be a future edition, some attention could be made to the selection of images suitable for black and white reproduction and then techno-tweaking them to optimize their reproduction in monochrome (or, in the alternative, bite the bullet and produce the images in color).

Art & Life provides welcome primary source material—albeit selected and selective—regarding the phenomenon of Eddie Burrup. In a text of 275 pages, the pages 17–184 relate to the pre-Eddie Burrup years, while the pages 185–264 relate to the Eddie Burrup years. This suggests that a book dedicated to the latter period is a sustainable proposition for a future publication.

Art & Life throws light on Australia’s greatest visual arts hoax. Elizabeth herself struggled to settle on a word to describe it: “the experiment/device/ruse/stratagem/trick/ploy/hoax/cunning manoeuvre” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 fax, p. 201). She elaborated: “the story is that Elizabeth Durack becomes Eddie when she paints these morphological paintings? And this is actually true. Eddie Burrup is Performance Art” (

Clancy 2016, 1995 fax, p. 202).

Eddie Burrup is a fascinating chapter in the story of Australian art. Elizabeth had written of “the immortal Ern Malley” (

Clancy 2016, 1985 essay, p. 174). Ern Malley is the fictitious poet of Australia’s most famous literary hoax (

Heyward 1993). Now Elizabeth had created the immortal Eddie Burrup.

After the whiff of controversy has blown over, the rage of a few autocrats has subsided into oblivion, and the pettifogging critics are silenced (by time or irrelevance), then we are left with Eddie Burrup, a unique suite of masterworks of Australian art produced in the twilight of a life and in the grip of a mysterious creative impulse.

A reader should not be put off by the bland title of Art & Life. This book is packed with the politically incorrect thoughts of Elizabeth Durack. It touches on the politics of identity, the plasticity of race and gender, and it reveals the long artistic gestation of Eddie Burrup and his incarnation in Elizabeth Durack’s 80th year.

The Book

Elizabeth Durack, Art & Life, Selected Writings, Perpetua Durack Clancy (Ed.), Brisbane: Connor Court Publishing, ISBN 978-1-925501-09-4, 276 pp., A$29.95.