1. Introduction

We may postulate that hand-marking practices at known locations were culturally transmitted across distances (“diffusion”), or alternatively that they came to be made in diverse places as impulsive expressions of affordances answering the needs of people in particular environments. It is beyond the scope of our present knowledge to attempt an answer on this score, but this does not mean that there is nothing to be said and argued about. In fact, after many studies have been undertaken, much to do with hand stencils and prints is still in dispute. So my aim here is the modest one of revisiting basic technical aspects of hand-marking production (

Figure 1), viz what has gone into their making. In a previous article in this journal I argued the case for the hand trace as a convenient external term lending itself to exogrammatic use. For a mark or object to function as an exogram it must

mean something and that meaning needs to be accessible. The trace element of hand stencils and prints eminently satisfies this requirement, doing so in a minimal way by communicating information about the nexus of the biological self and its defining and shaping environment. Theoretical engagement with this nexus has in recent decades given rise to a new discourse on the subject of the “ecological self”. My understanding of the term derives from cognitive psychology, in particular the founding studies of Neisser and his colleagues [

1] working with concepts relating to the idea of “direct perception” developed by J.J. Gibson, whose focus was the perceiving organism extracting meaning from its surroundings. Meaning is present in the form of “affordances” which structure an organism’s activities [

2]. In the case of human hand-marking, the rock surface, the hand, and the traced hand are to be seen in the light of Gibsonian affordances generating in the first instance minimal meaning relating to the hand-marking agent’s self-awareness as a negotiator of environmental spaces (distances, planes, obstacles, shapes and textures).

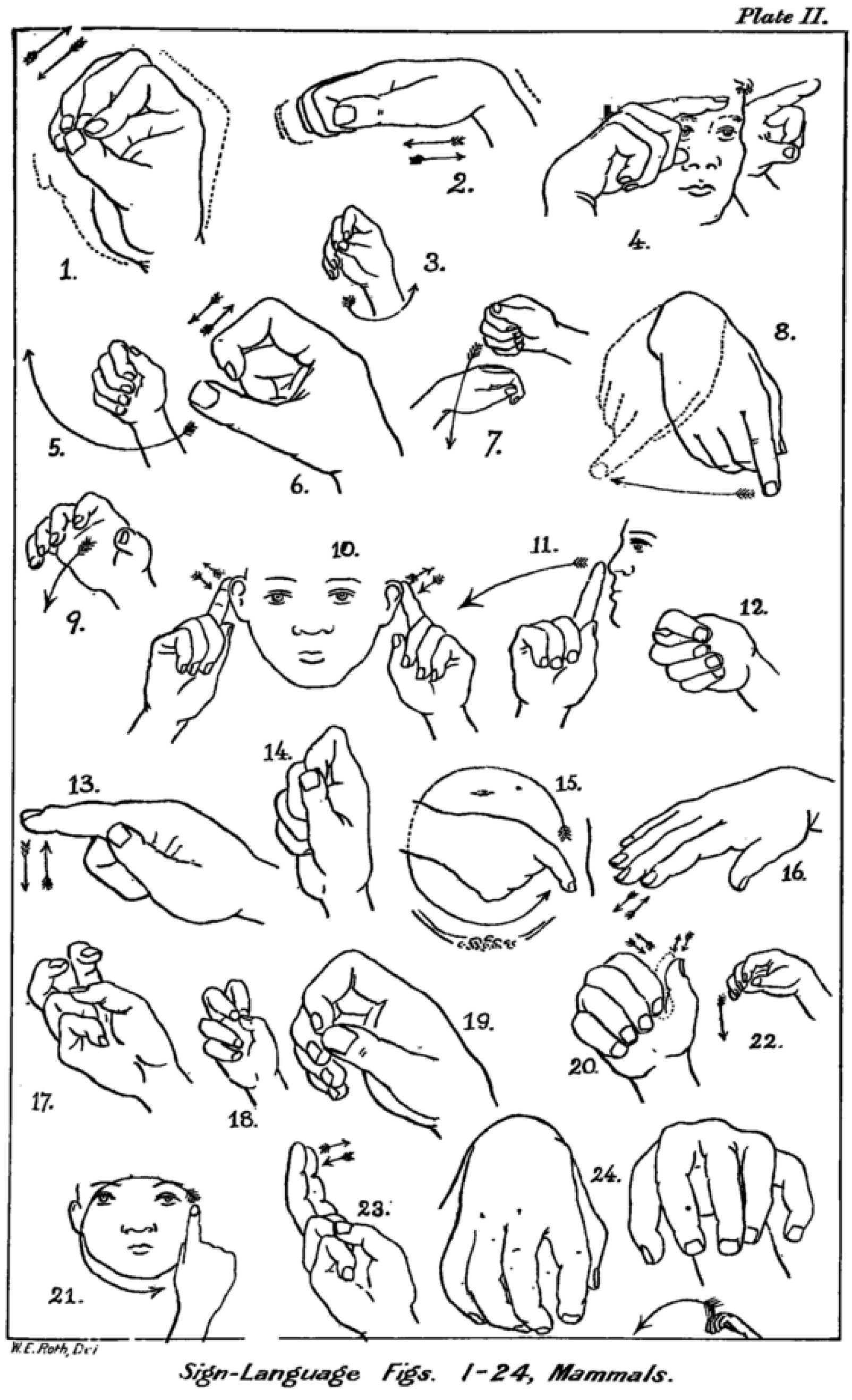

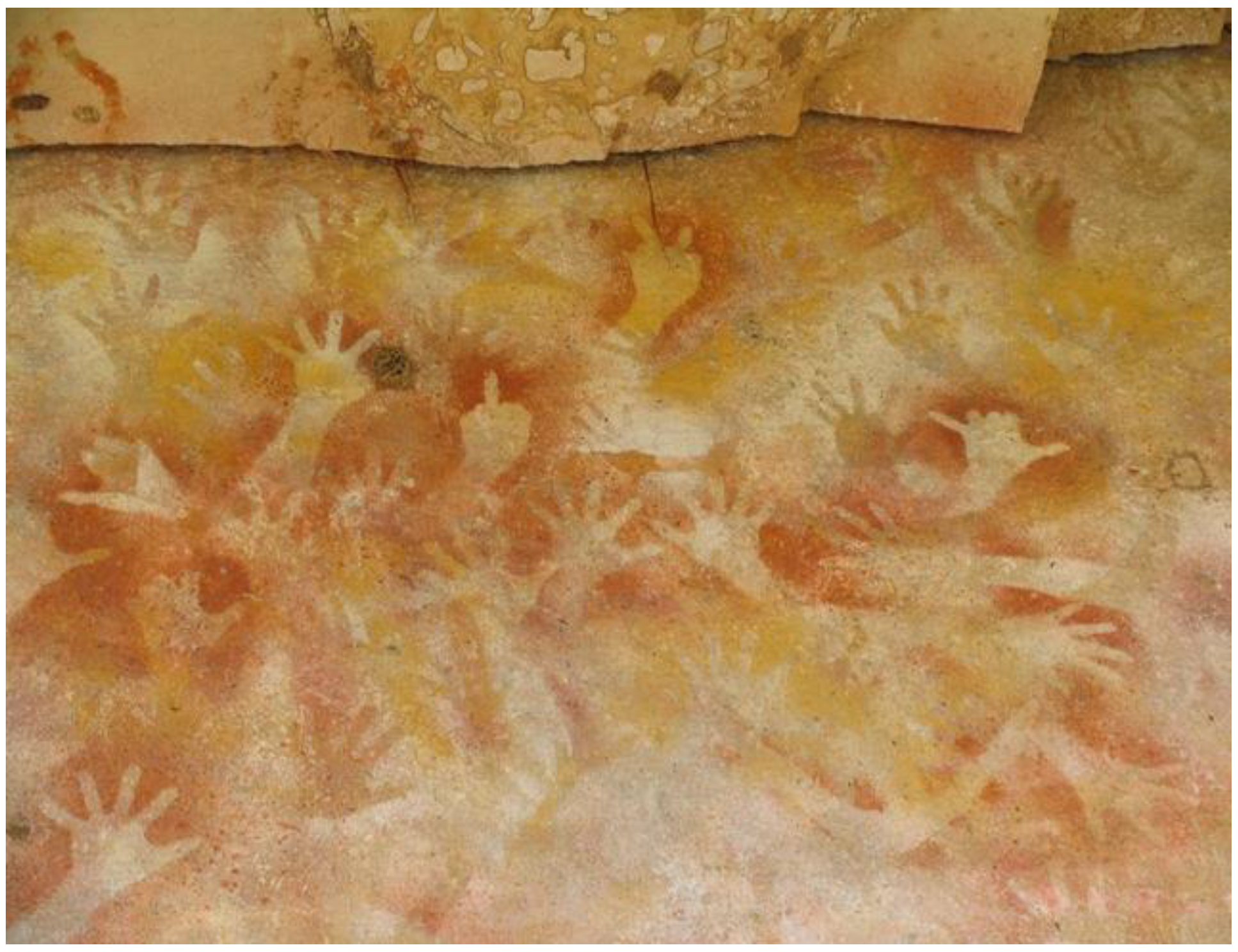

Figure 1.

Numerous stock and “decorated” hand stencils, Major Art site, Mt Borradaile, Arnhem Land, Australia.

Figure 1.

Numerous stock and “decorated” hand stencils, Major Art site, Mt Borradaile, Arnhem Land, Australia.

Importantly, the hand mark possesses what I term

act-identity—alongside

author-identity accessible if the maker is known.

Act-identity, unlike

author-identity (“signature”), is universally readable ([

3], p. 296). I have chosen to distinguish these aspects of the hand mark image because what is described as “signature”, viz the identity of a particular maker, is only decipherable through cultural knowledge, whereas “act-identity” is immediately accessible to any comer as a trace of an originatory action. Cultural meanings will differ from place to place, but the act of leaving a direct and recognisable trace of a hand provides a universal starting point for denotative elaboration. For details and citations I refer the reader to my argument set out at length in “The case for hand stencils and prints as proprio-performative” [

3], the companion piece to this article. A “proprio-performative” image is defined as one which addresses the viewer directly and in a way which conveys information about the artist-agent.

It should be noted that the art of stencilling has developed to include a large repertoire of objects besides the hands, hand and forearm. Even drawing examples from Australia alone (while acknowledging Australia’s possibly unique diversity [

4], p. 419), we have human and animal feet, the human body itself (rarely), implements, utensils, weapons, pendants, leaves, snakes, fish, mice, lizards, macropod legs and kangaroo tails, as well as whole birds and isolated images of a bandicoot, horse’s hoof and mammal skin. (For a digest of finds with citations relating to the unusual among the above, plus evidence for the antiquity of recently-located whole bird stencils, see Taçon

et al. [

4]). A different kind of “composite stencil art” has been identified by Walsh in his management study of archaeological sites in the Queensland Sandstone Belt. According to Walsh, nets, zig-zags, “‘ladders’, ‘trees’, and even humanoid figures” previously regarded as a freehand painting style, are accomplished by an accumulation of stencilled units (sometimes in the hundreds) to form an independent motif through a technique of positioning and masking body parts and/or artefacts during pigment application [

5]. With acknowledgement to Walsh, this technique was used by Lorblanchet (who had worked in Australia) in his well-known experiment reproducing the spotted horses panel at the French site of Pech-Merle [

6,

7], pp. 105–121).

Significant as the topic of stencilling is in general, the object of my inquiry is not stencilling as such, but the phenomenon of hand-marking. Hand-marking has created extraordinary sites around the world (from Patagonia’s Cueva de las Manos to Australia’s Carnarvon Gorge), sites which prompt us to ask why stencillers have so frequently and on such a large scale chosen to imprint their hands. Hand-marking possesses acknowledged special status in the rock art repertoire. In the context of the argument I put forward in the companion piece to the present article, it emerges as a form of iconic representation of the ecological self in action, a very particular kind of action which ultimately opens out possibilities for a visual language. See especially Sections 6.2 The “Ecological Self”; 6.3 The Rock Surface as Rudimentary Mirror; 6.4 Performative Images; 6.5 The Looming Effect and Representational Momentum; 6.6 Mirror Neurons and 7.2 A Definition in Dobrez [

3].

My previous article has analysed the perceptual and cognitive aspects of hand-marking. But there are many ways of approaching hand stencils and prints in rock art. These range from remarking on them as manifestations of a universal human desire to record one’s presence, to speculating about possible methods of production, symbolic placement of images on surfaces (and in relation to the surrounding terrain), associations with other images, and meaning within sign systems. Or we might note colour patterning and formal arrangement, treating a rock art panel as a discrete aesthetic object. Because we are eager to uncover what hand marks might add to our understanding of the human story there is an imperative to date them. Other empirical studies centre on attempts to determine the age, gender, handedness, and numbers of “authors” involved. A study of technics—rigorously carried out through observation, data analysis, appeal to ethnography and, where warranted, a testing of the field of the possible through replication experiments—can further our understanding of the role of image-making activities. My aim here is to comment on fundamental aspects of technique involved in the making of hand marks. However, to have a worldwide conversation on the topic we need to agree on what views we hold in common. So, with this in mind, my desire at the outset is to ask where researchers stand on a number of basic issues under discussion since rock art studies began to inquire into the who, how and what of hand stencilling and printing.

2. Definitions

At this point in time, when a global conversation about rock art is more than ever possible through information-sharing and well-attended international meetings, it seems reasonable to ask that we attempt to reach some consensus about what we see as universal and what is patently culture-specific. Hand-marking is a global phenomenon. We can agree on this: it is a starting point. As soon as we begin to ask even apparently simple questions about how hand stencils are made differences emerge. Is the same true of hand prints? Can we agree on the way a hand print is made? Will the IFRAO English definition—“a positive pigmented imprint of a human hand, made by pressing a paint-covered hand against the rock surface”—satisfy everyone (

Figure 2)? Certainly the IFRAO French “empreinte de main positive” and Italian “impronta di mano” descriptions contain nothing to contradict it ([

8], p. 8, p. 84, p. 153). Sometimes a hand print will be called an “impression”: “Impressions are made by pressing the palm of the hand, which has been dipped in paint, to the rock” ([

9], p. 42). Unfortunately few of us are multi-lingual so a great deal of what the

Rock Art Glossary might offer us by way of insights into diverse, and sometimes divergent, approaches will be closed to many. My hand stencil might look like yours but our understandings of the way it came into being and what it signifies might differ considerably.

Figure 2.

Hand prints, Blue Dome site, Idaho, USA.

Figure 2.

Hand prints, Blue Dome site, Idaho, USA.

In any conversation it is important that a speaker’s standpoint, or “subject position”, is well understood. What any one of us has to work with in visualizing technical processes is exhausted in a list: finds at sites (e.g., ochre and implements), measurements, experiments, ethnographic descriptions—and hunches. Importantly, though, the way we shape our ideas will be subject to geographic and cultural influences. It is not surprising, therefore, that Europeans, unless they have worked elsewhere in the world, will tend to adopt positions influenced by the literature relating to Franco-Cantabrian sites. The British are caught between two worlds. Often they will have knowledge of Australia, once an outpost of Empire and a convenient place to engage in fieldwork. However, their closeness to the great French and Spanish sites, which since the 19th century have provided a critical arena for rock art research, sometimes means that they will regard conjectures made during the long period that these sites have been investigated as having special authority. For instance, a British university website currently up-and-running illustrates the acceptance of French theorizing as having universal application. Having mentioned prehistoric sites from South America, Africa and South East Asia, including Australia, the website author takes up a position entirely based on speculation about methods employed at Franco-Cantabrian locations:

The experimental replication of hand stencils shows that they were best produced by blowing watered-down pigment of runny consistency through hollow tubes, and the recovery of ochre-stained shells and bird bones below stencils in several caves reveals the specific equipment used to do this. A large bivalve shell was used to contain the runny paint, and a short tube inserted into it like a straw. Holding the ensemble close to the subject hand a second tube was used to blow across the first. This created a vacuum which sucked the pigment up from the shell as a fine spray. This created the characteristic diffuse cloud of colour around the hand, while revealing the hand in sharp outline.

The Groenen two-tubes hypothesis, difficult to visualize in operation, comes across as rather cumbersome, and the use of the qualifier “best” is surely not enough of an excuse for treating speculation as fact, however much its workability has been displayed in replication experiments [

11]. A replication experiment, by demonstrating a method as unfeasible, may falsify a theory, but it cannot prove it merely by virtue of the fact that the method

works. For a considered review of the “vaporisation à l’aide de deux tubes creux disposés à angle droit” method in operation see Le Quellec ([

12], pp. 249–250). If we understand that the website quoted here is designed to showcase the research project of the team which in 2012 offered us a then oldest known date for hand stencils at El Castillo, Spain [

13]—very recently overtaken by a finding for a hand stencil in a cave in Sulawesi, Indonesia [

14]—we are able to place this description of technique firmly in the perspective of freewheeling theorizing about the caves of southern Europe, a theorizing which in its beginnings was unchecked by observations made by privileged ethnographers of the New World. Such is the force of tradition.

Even the notion of blowing through a tube, accepted by many, remains speculative, inference drawn from ochred bone tubes found at hand stencil sites. Clearly it would be good to have a review of all the candidate bone tubes found around the world. We do need reassurance that such tubes display clear evidence of having contained pigment—otherwise we might surmise that they were used to mix paint in shells or other containers. Added to this concern is an abiding suspicion that there might be a bias in some quarters towards answers centred on technology, as if complex tools were of themselves something to celebrate—the myth of progress being an unjustified but nevertheless spontaneous default position of many researchers.

For anyone seeking authoritative general information about Australian hand stencilling practice the ANU’s

Rock Art Research Centre offers the following description specifying what is thought to obtain in relation to Australian stencils:

Stencils in Australian rock art are made by mixing dry pigments (such as ochre, clay and charcoal) with water and/or saliva in the mouth and spitting the mixture onto the surface of the rock to create a negative image or outline of an object or body part. The most common stencil in Australia is the human hand (this is true of many countries around the world).

Note the present tense: “are made”, the point being that the making of stencils is a continuing practice in some Aboriginal communities. Australian research into the presence of saliva in pigment samples from stencil sites has been limited and there should be more analysis of this kind, but there is a wealth of documented observation of the ongoing techniques of hand-marking by indigenous peoples, encouraging speculation about past practice. Spencer and Gillen in

Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899) note that stencilling the hands palm to surface by blowing ochre or charcoal from the mouth was “practised . . . all over the continent” [

16], p. 616]. Herbert Basedow (1881–1933) also appears to be referring to a practice

generally observed when he suggests in his 1935 text

Knights of the Boomerang, which narrates his life among Aboriginal people, that they have “evolved a technique of their own” ([

17], p. 102; [

18], p. 261). The

passé title of Basedow’s book reflects his conviction (since overturned by DNA evidence) that Australian Aborigines were Caucasians—a view based on the discredited race theory of another age, but one which predisposed him to look with sympathetic interest for cultural parallels, one of them being the correspondence he sees between hand stencil imprints and written signatures. (For a discussion of Basedow and his historical milieu see Zogbaum [

18])

Diverse reasons for the making of hand stencils are given in the literature. While at one location they will be made by as marks of respect ([

17], p. 102) and at another as “fun” ([

19], p. 19), in Australia at least there appears to be a continent-wide manner of producing them, as outlined in the following description by Basedow (backed up by others):

Briefly stated, the method is this. The visitor takes from a small plaited dilly-bag . . . a lump of pipeclay, and crunches it with his teeth. Retaining the masticated product on his tongue, he fills his mouth with water and makes a thorough mixture. Then placing his hand over the chosen spot, he squirts the contents against the back of it, so that the pipeclay suspended in the water splashes the rock all around. When the hand is withdrawn, a negative imprint of it remains, which may or may not be subsequently filled in with red ochre.

([

17], p. 102; see also [

18], pp. 261–262)

Several important observations relevant to debates among rock art researchers are made here, and I shall comment on two of these presently, viz the clear picture which is presented of

palms of hands held to the rock surface and the practice seen in some places of

over-painting stencilled hands. From the point of view of the present discussion, it is Basedow’s record of mastication of paint material which is of prime interest. The method is not exclusive to hand stencils. In this regard it is worth noting that an Arnhem Land painter on barks reported to Brandl that, when making a Rainbow Snake image on rock, he used his mouth as a receptacle for water and ochre and sprayed the mixture onto the image to create spots ([

20], p. 105;

cf. also McCarthy [

9], p. 35); compare, as a matter of interest, the reputed technique of making spots on the famous horses of Pech-Merle, France [

6,

7], p. 479), and for mention of further Australian ethnographic sources recording blowing from the mouth see Dobrez [

3]).

McCarthy, allowing an alternative method of production, has this to say about Australian stencils in general:

The stencils are made in two ways, either by blowing powdered pigment from the mouth or from a little sheet of bark on to a wetted surface, or by blowing liquid pigment from the mouth, on to a dry surface, around an object held against the rock.

Humans are resourceful and any imagined plausible method should not be ruled out. It is important to remember, however, that materials like bark are perishable and will not remain in the record. While accepting direct spraying from the mouth, the

Bradshaw Foundation website relating to “World Rock Art” adds expulsion of “charcoal powder through a reed” [

21]. Malvesin-Fabre

et al. ([

22], p. 14) suggest that hand stencils at Gargas in the mid Pyrenees, France, might have been produced, not as iconic images made in their own right, but as accidental by-products of an activity of body-painting where holding a hand against a wall would be a matter of convenience rather than intentional design.

An early Gargas theory proposed that the process involved projecting powder onto a moist surface. This theory is, however, dismissed by Barrière who argues that the stencils’ characteristic stippled haloes could not have been achieved in this fashion: “a dry coloured powder sprayed on to a damp rock face does not give the spattering effect . . . and almost always gives ‘fall-out’ below the hand, a feature which is never seen at Gargas”. Methods clearly vary between sites around the world. At Gargas there are stencilled hand images which appear to have been made by dabbing with a pad, thus producing “a regular area of paint around the hand and no diffused halo” ([

23], p. 76).

Notwithstanding variety in pigment application, blowing from the mouth has been reported by ethnographers in so many Australian contexts that it cannot fail to be described as a dominant technique. Unfortunately a means we have available to help us make up our minds about this crucial aspect of stencilling has only limited application. Saliva possesses a detectable carbon signature, but this marker diminishes over time. So, it is a matter of frustration that pigment analysis able to supply evidence for the presence of saliva in paint—thus supporting the blowing from the mouth thesis—is defeated when dealing with stencils older than a few hundred years ([

24], p. 92). If the “Australian method” were to be emphatically established across the world, its status as a technical universal would prompt us to ask radical questions about its genesis. Might not the architecture of the brain itself, the product of long-established patterns of interacting with the world, dispose the human organism to pre-set sequences with neural underpinning from those localized areas of the cortex coordinating control of face and hand? We might look to Broca’s area, the motor site for speech, which recent studies have implicated in the development of language-readiness through an already existing gesture recognition apparatus [

3].

3. Placement

To the extent that the body itself functions as a tool [

3],

placement of an image comes under the heading of technique. Of course motives of a cultural sort, like the superimposition of hand stencils on special images at sites of increase, come into play in potent ways. However, these motives do not impinge on matters of technique pure and simple. Just

where a hand image, stencil or print, is placed on a rock surface will be determined in the first instance by the capabilities of the human body, including the ability of one human to assist another, and in the second by any possible supporting apparatus which might hypothetically have been employed, such as a scaffold. It should be noted, however, that placement of hand marks usually correlates with the apparent age and stature of their makers—as judged at least provisionally by hand size ([

25], p.109). At sites around Laura, Cape York, for example, intimate ground-level shelters feature small hand stencils (

Figure 3) which appear to be the work of children (S. Trezise, pers. comm. 15/8/2014). Instances have been recorded of supposed children’s stencils at heights suggesting lifting by adults ([

25], p. 109; [

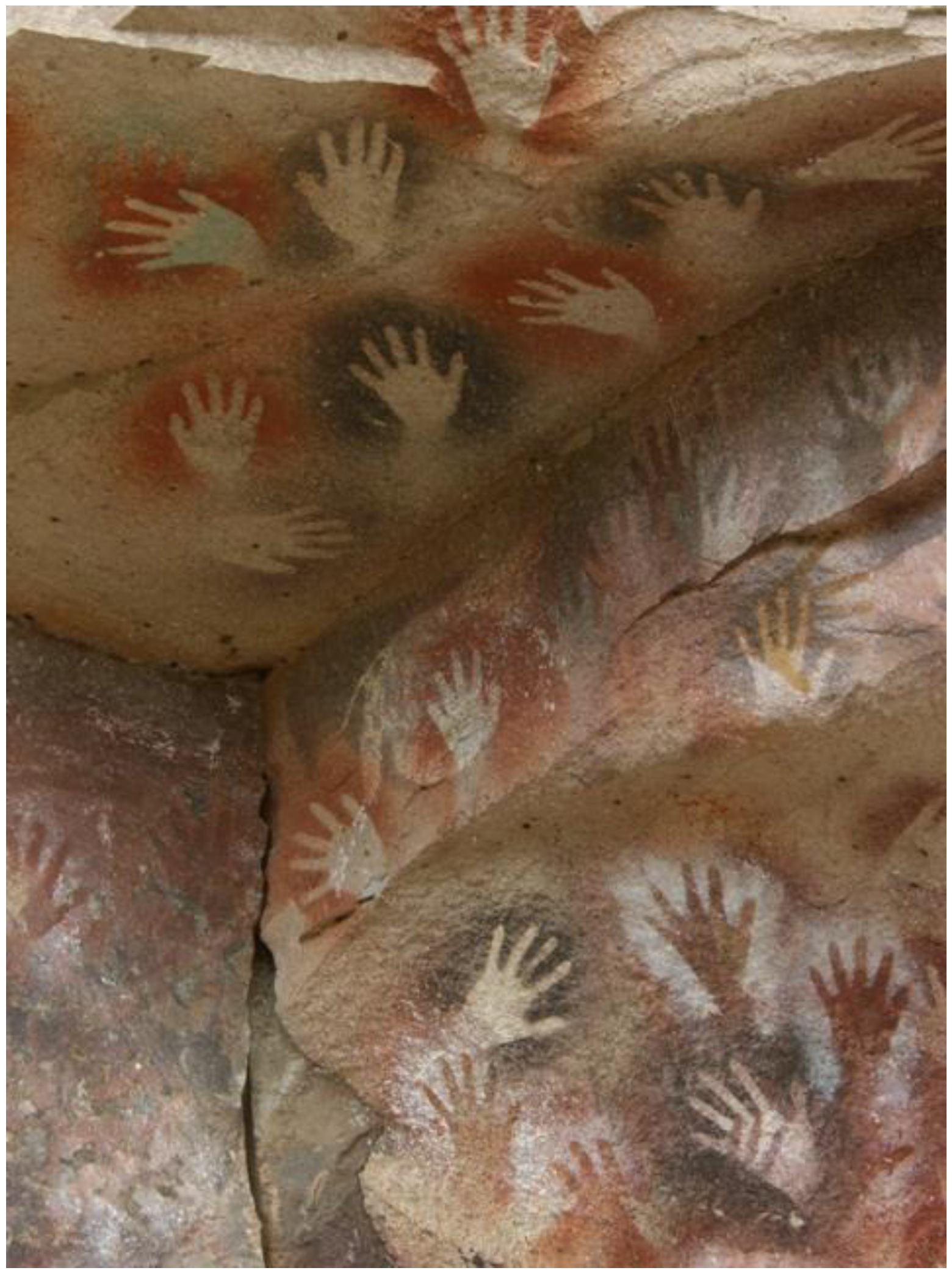

26], p. 14), and “adult” stencils have been found in difficult places where the alternative explanations must be: (a) that an athletic exploit is involved; (b) that floor levels or wall contours have changed over time; or (c) some engineering feat is implicated. Witness these stencils placed at height at Cueva de las Manos, Argentina (

Figure 4), and, more strikingly, stencils occurring at up to ca. 8 m (25 ft) height at a site in Cape York, Australia (

Figure 5). Comments comparable to the above may be made of positive hands. In the Victoria River region, Northern Territory, Australia, McNickle has recorded one site where “well over one hundred hand prints have been placed on the wall, many of them well above unaided human reach” ([

27], p. 40). In connection with north-west Australia, Walsh asserts: “ancient imprints have commonly been applied in inaccessible areas, at times 20 m (65 ft) above floor level” ([

28], p. 94).

Figure 3.

Small shelter with children’s hands, Cape York, Australia.

Figure 3.

Small shelter with children’s hands, Cape York, Australia.

Figure 4.

Stencils at height, Cueva de las Manos, Santa Cruz, Patagonia, Argentina.

Figure 4.

Stencils at height, Cueva de las Manos, Santa Cruz, Patagonia, Argentina.

Figure 5.

Stencils at great height, Gugu-Yalangi, Cape York, Australia.

Figure 5.

Stencils at great height, Gugu-Yalangi, Cape York, Australia.

6. An Ethnographic Reality-Check

It is important to recognise that not all questions will be answered by appeal to criteria relating to the mechanics of an operation. For example, the notion that there might be a plausible

non-practical reason for spraying saliva-mixed pigment from the mouth (at one level, of course, the method

is practical, eminently so, since it

works) is suggested by a recorded preoccupation with, and ritual attitude to, bodily fluids among some groups for whom a stencilling tradition is still alive today. Many such attitudes, much like poetic/metaphoric elements in modern languages, will have a longevity relating to a long lost-sight-of origin. Spencer and Gillen remark on a central Australian practice of “spittle-throwing” (“

Puliliwuma”)—a form of magic intense enough to cause the targeted person to waste away ([

16], pp. 552–553). Elkin speaks of blood being used as a sacred, efficacious,

ex opere operato substance in ceremonies of increase “not only to paint the totemic emblems on the actors’ bodies or to decorate some symbol, but also to anoint the stone which is the permanent [totemic] symbol” ([

38], p. 225). Meaning attributed to particular bodily fluids will, of course, vary from place to place, but this is not the issue: it is the general fact of their being significant which is relevant here. The great ritual cycles of fertility, procreation and renewal of Arnhem Land employ as major poetic tropes water, blood and semen, together with ochre for body-painting. All four liquids are woven in a powerful way into the Goulburn Island Cycle performed as a prelude to the coming of the monsoon ([

39], pp. 47–72). In western Arnhem Land, Australia, the “sweat” of a dead person is regarded as a spiritually powerful substance. As recorded in 1982, Kunwinjku people hold that “you have to wash it [“sweat”] away and you have your own body back” ([

19], pp. 108–109)—this in the context of a washing ceremony which removes the influence of the dead from the living. Might not beliefs such as this when related to

saliva—beliefs which would give added meaning to the notion of a stencil as so potently idiosyncratic that it can act as a stand-in for an absent or dead person—help to explain the twin practices recorded at Arnhem Land sites (1) of acknowledging the “living” portrait embodied in the trace hand and (2) of masking the stencils of the dead to erase this influence ([

3], p. 285)? In this way the power of bodily fluids might be expected to influence the practice of mixing pigment with saliva.

At Balgo in the Great Sandy Desert, central Australia, where there is a tradition of image-making in the earth itself,

i.e., “sand drawing”, great emphasis is put on the importance of

touching. Reflecting an overarching world-view, words in languages of the area which refer to the making of both painted images and those drawn in the sand are said to “cluster around ideas of touching, poking and piercing” ([

40], p. 52). When pondering hand marks and the way they are produced, it might help to think about

what else might be shaping technical practices, viz an elaborated (symbolic) meaning which in all likelihood retains a link with an originatory real-world act. In the case of expelling liquid pigment from the mouth to record a trace of a hand making contact with a rock surface, we could be looking at ethnography that relates to the ritual significance of the practices of touching, the laying on of hands, non-stencil-related cases of expelling liquid from the mouth, as well as concepts relating to breath and speech.

The likelihood of symbolic significance being invested in every aspect of hand stencilling, from the outset of ochre collection (for instances of mythologies and rituals centred on sacred pigments see McCarthy [

9], pp. 34–35) to placing the hand on a rock surface, should make us wary of assuming that technical choices in image-making are driven by

mechanical considerations alone. Indeed it makes sense that, in many instances, technique—provided it works—will be subservient to considerations of cultural importance to a group, especially those which have their origin in a people’s direct relationship with an environment. An approach centred on technē alone, often governed by 19th-century progressivist notions, will not suffice. At its most misguided, it encourages an ungrounded hypothesizing about the involvement of possible tricky mechanical apparatuses in situations where quite different impulses and motives are clearly in play. Where rock art is concerned, considerations of an ecological kind provide a safe starting-point, biology “exuding”—to employ Leroi-Gourhan’s term when discussing our first tools ([

41], p. 106)—the symbolic. When considering the symbolic, we should be looking as much as anywhere else to the biological.

In its basic expression, hand-marking is interesting because it is technologically unencumbered. The body itself is the tool, producing readable external iconic images strategically placed for information-storage (in the first instance information-storage in the form of traces of bodily acts [

3]). With stencils, hand, mouth, ochre and a rock surface provide the wherewithal; with prints, hand, ochre and a surface. In view of this, I would suggest that a clearer, more candid testament of an organism

aware of its ecological niche cannot be found than hand-marking—and that the act reflects the human hand’s special status in species definition ([

3], pp. 273–275).

7. Selecting and Preparing Surfaces

Clearly not all rock art surfaces are suitable for paint application and in most cases these are avoided. What appeals as a suitable surface, however, will sometimes surprise. At Laura, Cape York, Australia, stencils are to be found on a pock-marked surface (

Figure 12). At the spectacular Patagonian site Cueva de las Manos there are instances of stencilled images standing out sharply against clean surfaces. On the other hand, there are also walls displaying a palimpsest of superimposed hands and layered colour (

Figure 4).

Figure 12.

Stencils, Gugu-Yalangi, Cape York, Australia.

Figure 12.

Stencils, Gugu-Yalangi, Cape York, Australia.

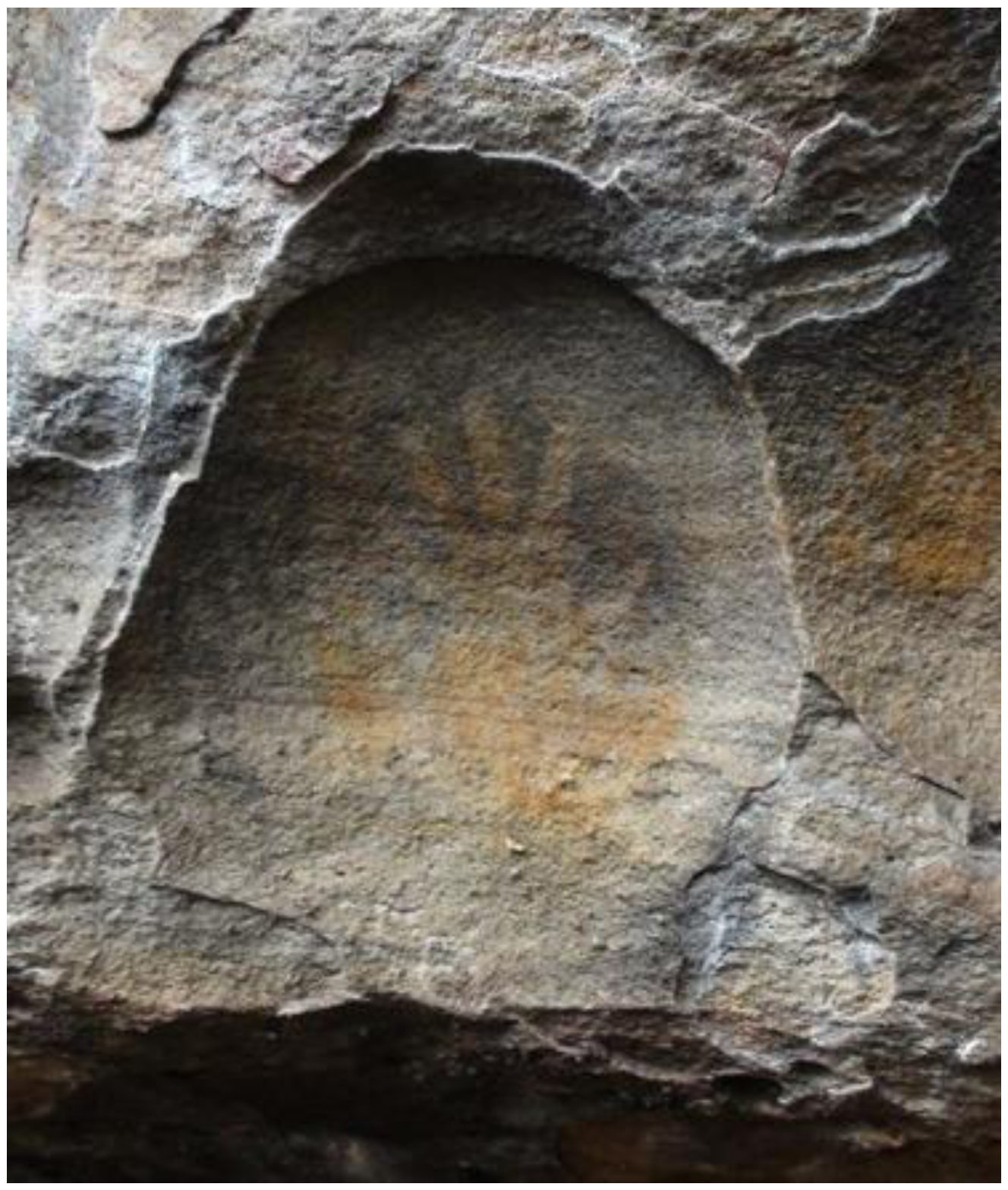

The choice of “framing” niches, like the famous one enclosing a single black hand at Gargas or other rock features conducive to display, is not uncommon (

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15).

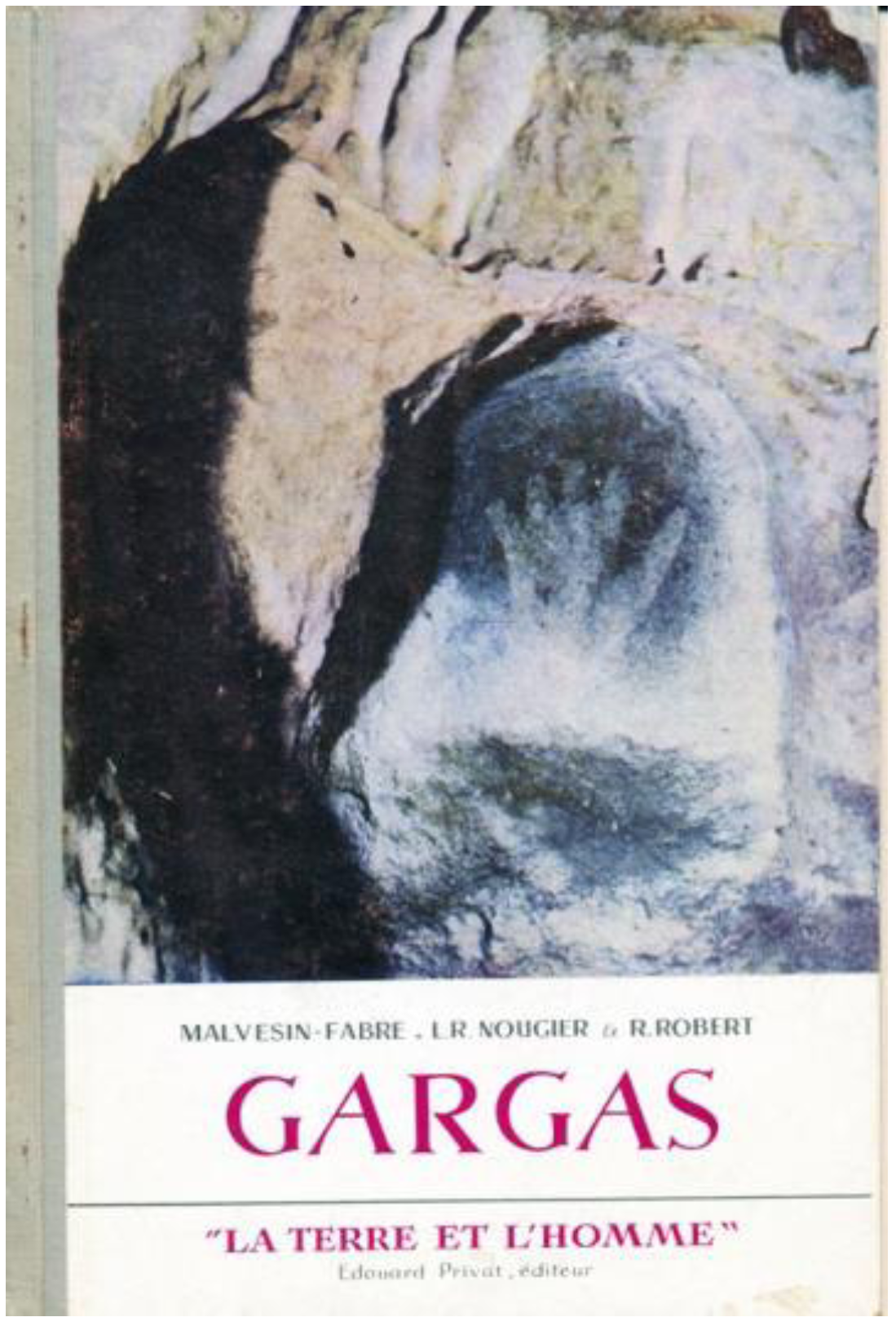

Figure 13.

Cover, Malvesin-Fabre et al. : Gargas: La Terre et L’homme.

Figure 13.

Cover, Malvesin-Fabre et al. : Gargas: La Terre et L’homme.

Figure 14.

“Framed hands”, Woronora, New South Wales, Australia.

Figure 14.

“Framed hands”, Woronora, New South Wales, Australia.

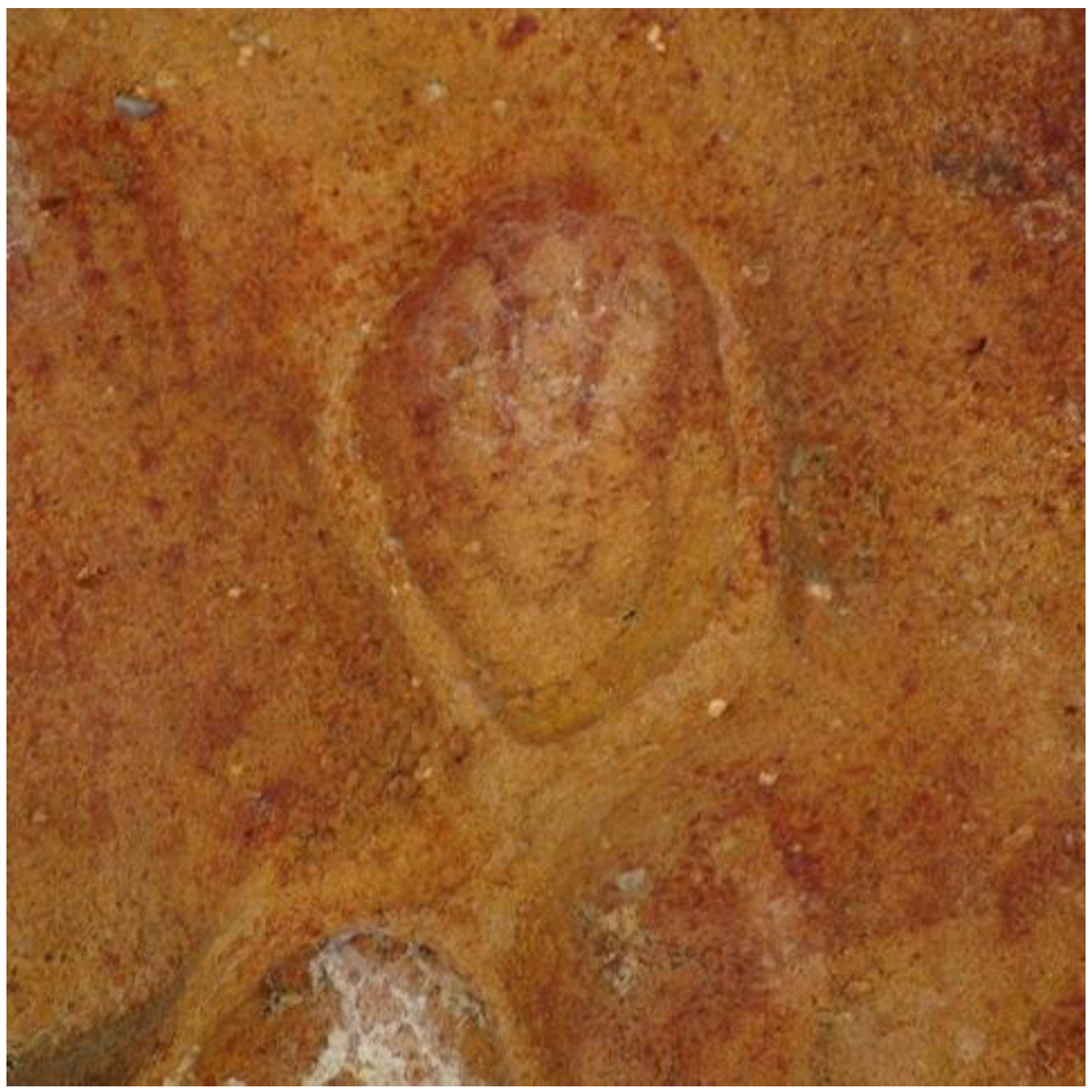

Figure 15.

Enigmatic “framed” hand image, Baby’s Feet Shelter, New South Wales.

Figure 15.

Enigmatic “framed” hand image, Baby’s Feet Shelter, New South Wales.

Surface preparation has been identified by Gunn [

42] at Mulka’s Cave, Western Australia. Such a method is seen as “a feature” of the site, where 35 stencils—white-on-red negative images which, because of subsequent weathering, look like positives—were made on a pre-pigmented surface. However, Gunn is at pains to point out that it is not possible to judge definitively whether the surface was prepared for the purpose of stencilling or simply provided a suitable area for making images. Mathews suggests the preparation of surfaces by dampening, after which dry powder is blown from the mouth “where it appears to have the durability of ordinary pigment” ([

43], p. 147).

10. Conclusions

In conclusion to this discussion of largely technical matters, it is important to stress that an exclusivist approach centred on

procedure alone is likely to overlook important factors determining the way an image is made. When it comes to understanding what we encounter in the field, ethnography remains an invaluable resource. As Huntley

et al. remind us: “choices regarding every aspect of rock art production, from pigment procurement, placement, application, and motif form are culturally mediated choices” ([

24], p. 93). At the same time, however, we should appreciate that our ethnographic sources relating to the cultural aspects of hand-marking belong to recent time, the period of contact. All things considered—and notwithstanding the value we will put on ethnography where it happens to exist—it is only with a vivid sense of

apparently unbridgeable distance from origins that we may think of recovering, through extant mythologies and rituals, memetic vestiges of our dialogic

beginnings—those faint remembrances which might serve to throw light on the

ur-act of symbolic communication.

When attempting to understand first impulses, our prime preoccupation will need to be the situation of the ecological human self in an environmental niche which offers material affordances for the appearance of readable marks of presence. Only by focussing in the first instance on the biological, rather than the cultural, will we begin to understand how the nearest thing to casual but nevertheless propitious marks—when recognised, repeated and varied—may become the stuff of an adaptable system of exograms, viz an organisable external arrangement of remembered signs promoting an entirely new freedom of mental activity.