Abstract

Negev rock art comprises a large and diverse corpus of motifs and compositions developed over the course of several millennia. As dating of specific elements is at present not possible, the rock art was analyzed statistically through the study of individual panels where internal sequences of engraving could be discerned. Examining the set of such individual sequences, larger scale reconstruction of engraving phases, sequences and patterns were recognized. Additional chronological markers, such as the presence of domestic camels or other chronologically diagnostic features, offer benchmarks for tying the general trends to more absolute frameworks. The reconstructed patterns reflect the long term history of the Negev and some of the most significant cultural and social transitions in the region are reflected visually through the rock art, notably a form of self-expression, a crucial complement to the historical sequences derived from sedentary peoples living farther north. For example the introduction of the domestic camel and its symbolic and economic significance is well evident in the rock art. Similarly, the emergence of Islam is expressed through the mark makers’ preference for "abstract" (non-figurative) motifs. One motif found throughout all engraving phases, transcending the religious, political and economic structures of Negev society, is the “ibex”. Although Negev societies have all focused, to one degree or another, on sheep and goat pastoralism, these animals are rarely present in the Negev rock art and never as herds. Ibex, whose role in the diet and daily subsistence was minimal, was the most commonly depicted zoomorphic motif.

1. Introduction

Although rock art is abundant in the Negev, few systematic analyses have been conducted. These few have focused on two aspects, chronology and meaning. Concentrating on the chronology, the primary focus of this paper, three different approaches have been studied: 1. The use of datable attributes in the art itself; 2. Archaeological stratification and association with archaeological materials; and 3. Stylistic attribution. Thus, for example, a corpus of 14 “horse” petroglyphs (Nevo 1991:104–105) [1] was dated to the Early Islamic period based on accompanying Arabic inscriptions. Similarly, at Timna two large panels bearing petroglyphs were dated to the Late Bronze Age based on specific datable attributes including an “Egyptian battle axe” and “chariot” reins tied to the driver’s waist (Rothenberg 1972:119–124) [2]. The attribution was supported by archaeological material finds found in close proximity (soft sandstone bowls buried by collapsed boulders) also datable to the Late Bronze Age. Anati (1956, 1962:181–214, 1965, 1968, 1993:71) [3,4,5,6,7] constructed a relative chronological sequence of rock art based on changing trends in engraving technique, size, shade of rock patina, and subject matter which he applied to both the Negev and neighboring regions. Recently (Bednarik and Khan 2009; Eisenberg-Degen 2012; Khan 1996) [8,9,10] Anati’s work has been critiqued and many basic points on which his schema was based have been refuted.

No direct dating of Negev rock art has been attempted. Though several chronometric techniques are available, it remains notoriously difficult, if at all possible, to secure absolute dates for petroglyphs (for a list of methods and their pit falls see Bednarik 2007:115–152 [11]) The present paper presents a proposed chronology based on relative sequences discernible within individual panels, the construction of larger scale trends derived from the small scale (individual panel) sequences, and the use of specific attributes and motifs to anchor the sequence and transform the relative framework into an absolute chronology. The sequence based on the Har Michia corpus shows continuous use of both motifs and styles over several millennia. For this reason even when direct dating becomes reliable and individual elements can be dated with precision the results will have little effect on the overall chronology of Negev rock art, at least until very large numbers of motifs can be dated. The great contribution of direct dating will be in securing the date of the emergence of the rock art phenomena in the Central Negev.

The long-term history of the Negev is reflected in its rock art. The introduction of new motifs such as the camel and later numerous "abstract" motifs, and the long-term trends evident in the rock art constitute a visual self-expression, a crucial complement to the historical sequences derived from sedentary peoples living farther north. In this way the rock art reflects both the cultural continuities of Negev societies, and highlights the innovations as they were introduced.

2. Har Michia

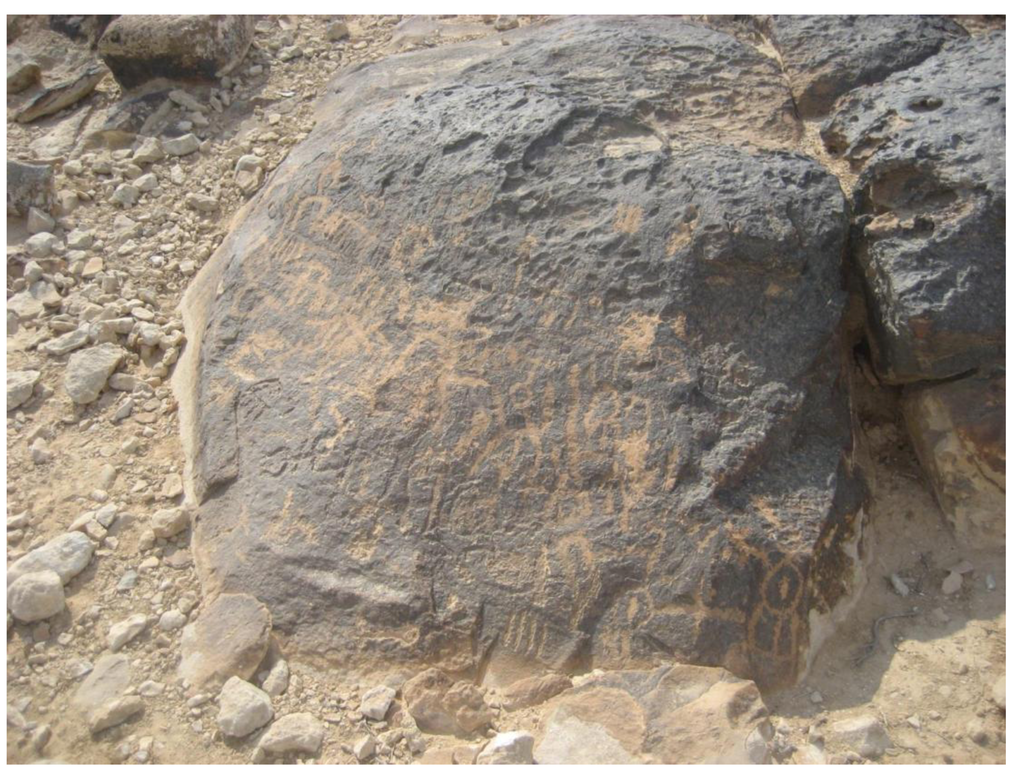

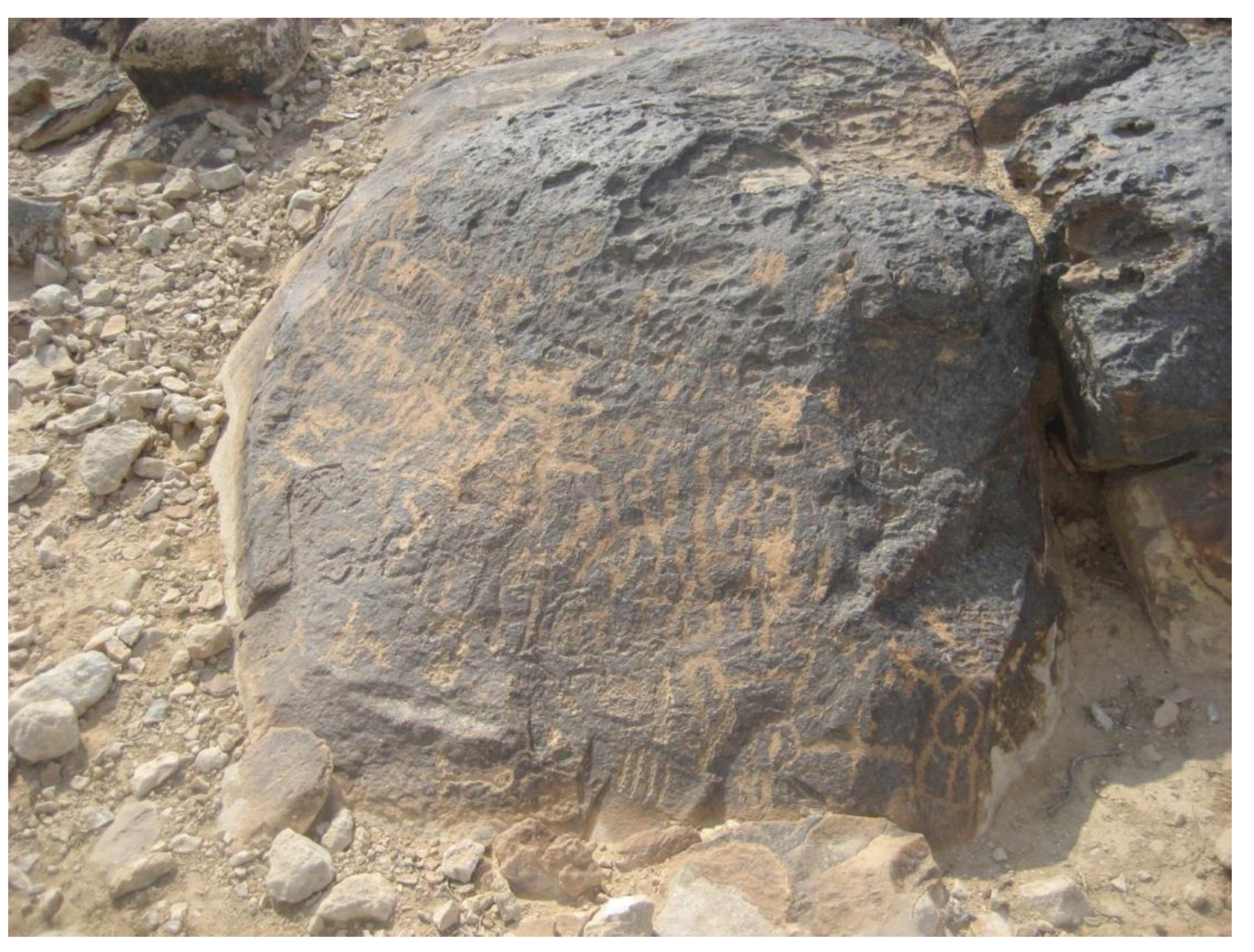

Har Michia, a plateau on the west side of Nahal Zin and 2–3 km west of the Byzantine town of Avdat in the central Negev, is the locus of intense rock art engraving on its eastern slope (Figure 1 and Figure 2). This region is composed of a series of parallel anticlinal ridges and synclinal valleys running on a north-east to south-west axis. The south-east slopes of these ridges are quite steep, while the north-west ones are gently inclined (Hillel 1982:79) [12]. The exposed rock in this region is Eocene and late Cretaceous limestone. With 100–125 mm annual rainfall, vegetation is sparse. The Avdat canyon, approximately 5 km from the site, offers reliable water sources with three active springs (Evenari et al. 1971:49, 54; Orni and Efrat 1973:165, 172) [13,14]. Many limestone outcrops have developed a dark rock patina (Evenari et al. 1971:61) [13]; these outcrops stand out against the bright, bare landscape and served as a primary target for rock engraving.

Figure 1.

Har Michia in the Central Negev.

Figure 1.

Har Michia in the Central Negev.

Figure 2.

General View of Har Michia facing south-east.

Figure 2.

General View of Har Michia facing south-east.

Human occupation in the central Negev can be traced back as far as the early Pleistocene and the first wave of migrations out of Africa. The earliest sites date to the Middle Paleolithic. In general, the archaeological record is rich and can be characterized as a sequence of periods of social and demographic florescence and decline (Rosen 1987) [15]. Economically, the transition from hunting-gathering to early goat pastoralism (herding-gathering) occurred in the 7th millennium BCE. Agriculture, based on run-off irrigation, was not introduced into the region until the 1st millennium BCE. A chronological chart with periods and significant culture attributes is presented in Table 1.

An area of 0.36 sq km of Har Michia was surveyed. All rock art found within this area, 965 panels with 5077 elements, was documented and this represents an estimated 5% of the total rock art of the Central Negev. The rock art of Har Michia comes in the form of petroglyphs created using several techniques including incision, pounding, pecking, and abrasion. These are almost entirely limited to the rock patina covered outcrops. With the initial petroglyph, the rock patina is removed revealing the inner host stone. The contrast between the light colored host limestone and the dark rock patina essentially constitutes the petroglyph. With the elapse of time, rock patina develops and darkens the petroglyph itself, and the petroglyph becomes closer in color to the surrounding surface until eventually it is no more than a slight depression, a sunken dark image within the somewhat darker patinated rock surface.

Table 1.

Chronological Chart of Periods and Significant Culture Attributes.

| Complex | Period begins | Substance | Cultural Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Paleolithic | ca. 1.8 mill. | Hunter-Gatherers | |

| Middle Paleolithic | ca. 200,000 | ||

| Upper Paleolithic | ca. 50,000 | ||

| Epipaleolithic | ca. 20,000 | ||

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic | 10,000 BCE | ||

| Transitional Cultures | 7th mill. BCE | Hunting, Herding | Introduction of the domesticated goat. |

| Timnian Culture | 6th mill. BCE | Herding-Gathering to mobile pastoralism | Introduction of the domesticated donkey. |

| Middle-Late Bronze Age | 2000 BCE | Settlements from this period have not been recognized in the Central Negev | |

| Iron Age | 1200 BCE | Agriculture, and Pastoralism. | Introduction of the domesticated camel. Major trade contacts. |

| Babylonian and Persian | 586 BCE | ||

| Hellenistic-Roman | 4th c. BCE | Trade, husbandry and agriculture | Cities, hamlets, military bases and camp sites. |

| Byzantine-Early Islamic | Mid 4th c. CE | Cities, hamlets, and camp sites. | |

| Middle Ages | 1000 CE | ||

| Ottoman-Recent | 17th c. CE | Traditionally—agro-pastoral. | |

In descending order according to frequency of depiction, the Har Michia motifs subjectively consist of "abstract" elements, “zoomorphs”, “anthropomorphs”, “inscriptions”, “hand and foot/sandal prints”, “tools/weapons”, and structures. As there are no indigenous populations living, using and producing rock art in the Negev, all terms and interpenetrations are subjective and based on the author’s understanding and reading of the material. The largest category consists of "abstract" elements with over 75 different “abstract” element types. Within all categories a linear style incorporating only minimal details dominates. “Anthropomorphic” petroglyphs are depicted in a variety of forms; most are un-sexed and are presented standing, or on “horse”, “donkey”, or “camel” back. The clearly “male” figures are presented either armed, or with an exaggerated phallus in the orant stance. Few petroglyphs of “females” were documented. “Horses”, “donkeys” and “camels” were at times mounted while other times they are in no apparent association with “humans” or other “animals”. Other “animals” depicted are “birds (mostly ostrich)”, “dogs”, “horned ungulates” (most of which may be identified as mature male ibexes, Capra ibex nubiana), “predators” (most likely leopards), “scorpions”, and “snakes”. In addition the species of many “zoomorphic petroglyphs” (22%) could not be identified. In some cases the “animal” is well formed, but does not include diagnostic attributes such as a hump, horns, mane or long ears, which would allow for classification.

3. Forming a Chronology

Approaching the Har Michia corpus and the question of chronology as a tabula rasa, not trying to fit the data into any existing formula, the recorded data was arranged and examined in several ways. Here two aspects that lead to relative chronologies and the emergence of patterns are presented: super-positioning of motifs one on another (Figure 3a,b and Figure 4) and phases of engraving based on relative darkness of the rock patina within individual panels (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 3.

Example of Super-positioning at Har Michia. “Heart” (element 16-41-30 measuring 22 × 17 cm) super-positioned over stylized “horned ungulate” (element 16-41-8 measuring 19 × 32 cm) super-positioned over “several ibexes” (element 16-41-9 measuring 12 × 14 cm, 16-41-33 measuring 6 × 10 cm, 16-41-6 measuring 13 × 13 cm, and 16-41-25 measuring 20 × 13 cm).

Figure 3.

Example of Super-positioning at Har Michia. “Heart” (element 16-41-30 measuring 22 × 17 cm) super-positioned over stylized “horned ungulate” (element 16-41-8 measuring 19 × 32 cm) super-positioned over “several ibexes” (element 16-41-9 measuring 12 × 14 cm, 16-41-33 measuring 6 × 10 cm, 16-41-6 measuring 13 × 13 cm, and 16-41-25 measuring 20 × 13 cm).

Figure 4.

Example of Super-positioning at Har Michia. “Foot print” (element 34-61-16 measuring 16 × 24 cm) super-positioned over Arabic inscription (lower left, element 34-61-17 measuring 10 × 19 cm)

Figure 4.

Example of Super-positioning at Har Michia. “Foot print” (element 34-61-16 measuring 16 × 24 cm) super-positioned over Arabic inscription (lower left, element 34-61-17 measuring 10 × 19 cm)

Figure 5.

Example of a Number of Re-patinated Shades on a Single Surface. Panels 37-11 (left, measuring 36 × 103 cm) and 37-12 (right, measuring 16 × 89 cm) with four different shades of re-patination. Numbers indicate engraving phase as determined by hue. Number 1 is earliest of the four phases on this panel.

Figure 5.

Example of a Number of Re-patinated Shades on a Single Surface. Panels 37-11 (left, measuring 36 × 103 cm) and 37-12 (right, measuring 16 × 89 cm) with four different shades of re-patination. Numbers indicate engraving phase as determined by hue. Number 1 is earliest of the four phases on this panel.

Figure 6.

Example of a Number of re-patina Shades on a Single Surface. “Abstract” (element 9-2-2 measuring 8 × 11 cm) placed partly contiguous to “equid” (element 9-2-1 measuring 12 × 15 cm). The shades of re-patination present two engraving phases.

Figure 6.

Example of a Number of re-patina Shades on a Single Surface. “Abstract” (element 9-2-2 measuring 8 × 11 cm) placed partly contiguous to “equid” (element 9-2-1 measuring 12 × 15 cm). The shades of re-patination present two engraving phases.

3.1. Super-Positioning

Super-positioning (one element partly or entirely covering another) was noted in numerous cases, summarized in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4. Cross-tabulating these recorded instances with motif type, certain patterns emerge. “Abstract” elements were most often involved in super-positioning. Of the recorded material 86% of all overlaying elements and 54% of all underlying ones are abstract. With “zoomorphic” and “anthropomorphic” elements involved in super-positions, up to 4 times more were recorded as underlying rather than overlaying. Thus, these “zoomorphic” and “anthropomorphic” motifs clearly pre-date the “abstract” ones overlying them, forming a relative chronology. Few cases were noted where two of the same motif type were super-positioned. These few instances offer an insight to stylistic development of the “ibex” motif.

Table 2.

Stratification of Attributes at Har Michia. Sum of elements is larger than the noted 5077 in the text as ridden animals (n = 59) are counted twice, once as anthropomorphic and once as zoomorphic. The single representation of a phallus is not stratified and not included in the table. Number of over and under occurrences do not include like on like.

| Motif type | No. of elements | No. of stratified elements | Over | Under |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Abstract” | 4346 | 609 | 227 | 41 |

| “Zoomorph” | 557 | 293 | 41 | 192 |

| “Anthropomoph” | 145 | 47 | 10 | 30 |

| “Foot Print” | 32 | 16 | 4 | 11 |

| “Inscription” | 27 | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| “Hand Print” | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| “Tool/Weapon” | 21 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Building | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sum | 5135 | 982 | 290 | 283 |

Table 3.

Stratification of “Zoomorphic” Species at Har Michia. “Buildings”, “Inscriptions”, “Phallus”, and “Foot/Hand” prints are not super-positioned below “zoomorphic” elements and therefore are not included in the table. “Scorpion”, “Snake” and “predator” are not involved in super-positioning and are not included in the table. Number of over and under occurrences do not include like on like.

| Under | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over | No. of elements | Total no. of stratified elements (above and below) | “Abstract” | “Zoomorphic” | “Anthropomorph” | “Ridding Anthropomorph” | “Tool/Weapon” | Total |

| “Horned Ungulate” | 254 | 159 | 21 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 33 |

| “Un-identified Zoomorph” | 125 | 60 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| “Equid” | 66 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0` | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| “Camel” | 73 | 28 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| “Dog” | 20 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| “Lizard” | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| “Bird” | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 555 | 264 | 35 | 23 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 70 |

Table 4.

Stratification of “Zoomorphic” on “Zoomorphic” Elements at Har Michia by Species. “Scorpion”, “Snake” and “predator” are not involved in super-positioning and are not included in the table. Number of over and under occurrences do not include like on like.

| Under | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over | No. of elements | Total no. of stratified elements (above and below) | “Horned Ungulate” | “Zoomorphic” | “Equid” | “Bird” | Total |

| “Horned Ungulate” | 254 | 159 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| “Zoomorphic” | 125 | 60 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| “Equid” | 66 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| “Camel” | 73 | 28 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| “Dog” | 20 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 538 | 262 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 19 |

3.2. Engraving Phase Based on Re-Patination

The engraving phase data differs from super-positioning as it relates to elements that are not necessarily physically touching or overlapping. Engraving phases were reconstructed based on comparing the hue of re-patinated elements and their relative darkness (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Patina (or patina), a thin crust (5 µm–1 mm) that develops on Negev limestone (including the Avdat ridge and Har Michia) is composed of iron, manganese oxides, quartz, clays and carbonates. Patina on boulders and re-patination of petroglyphs is highly affected by daily and seasonal variation in temperature, precipitation, wind direction and atmospheric dust, and the size and physical character of the underlying rock, (Krumbein and Jens 1981; Pope et al. 2002; Schneider and Bierman 1997) [16,17,18]. Therefore comparisons between patina shades were limited to single surfaces. Single surfaces, i.e., panels, present minimal change in inclination and are as constant a surface as can be found in the Negev desert. The governing factor followed is that the darker the patina, the longer it has taken for it to form (Krunbein and Jens 1981) [16]. Applying varying degrees of pressure or using different tools may penetrate the patina to different depths resulting in diverse patina shades (Macdonald 1981) [19]. In an attempt to compare like data, the technique used was noted. (For further discussions regarding patina formation see Dorn 1998, Fleisher et al. 1999; Liu and Broecker 2000) [20,21,22].

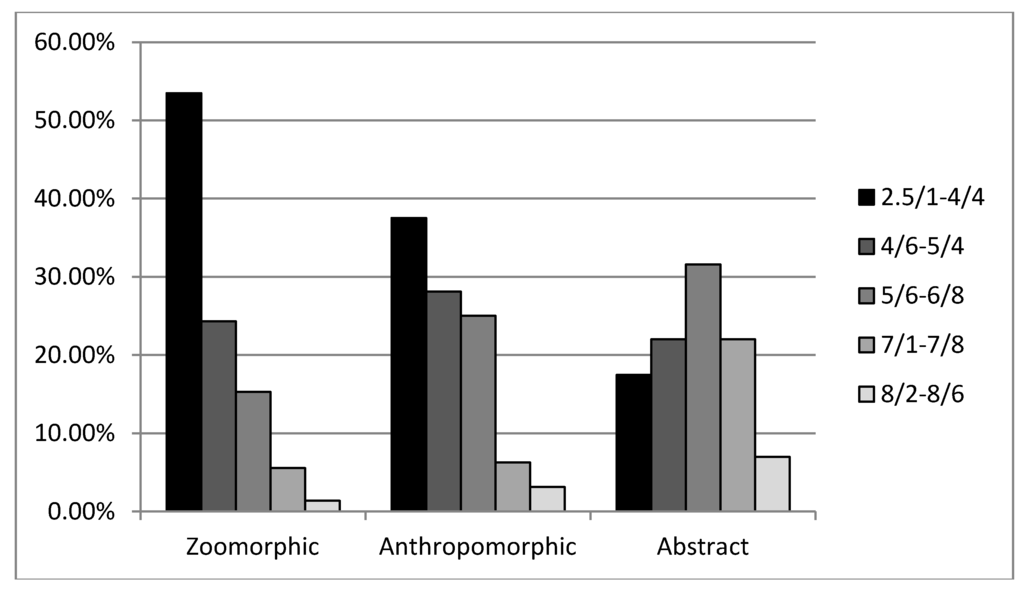

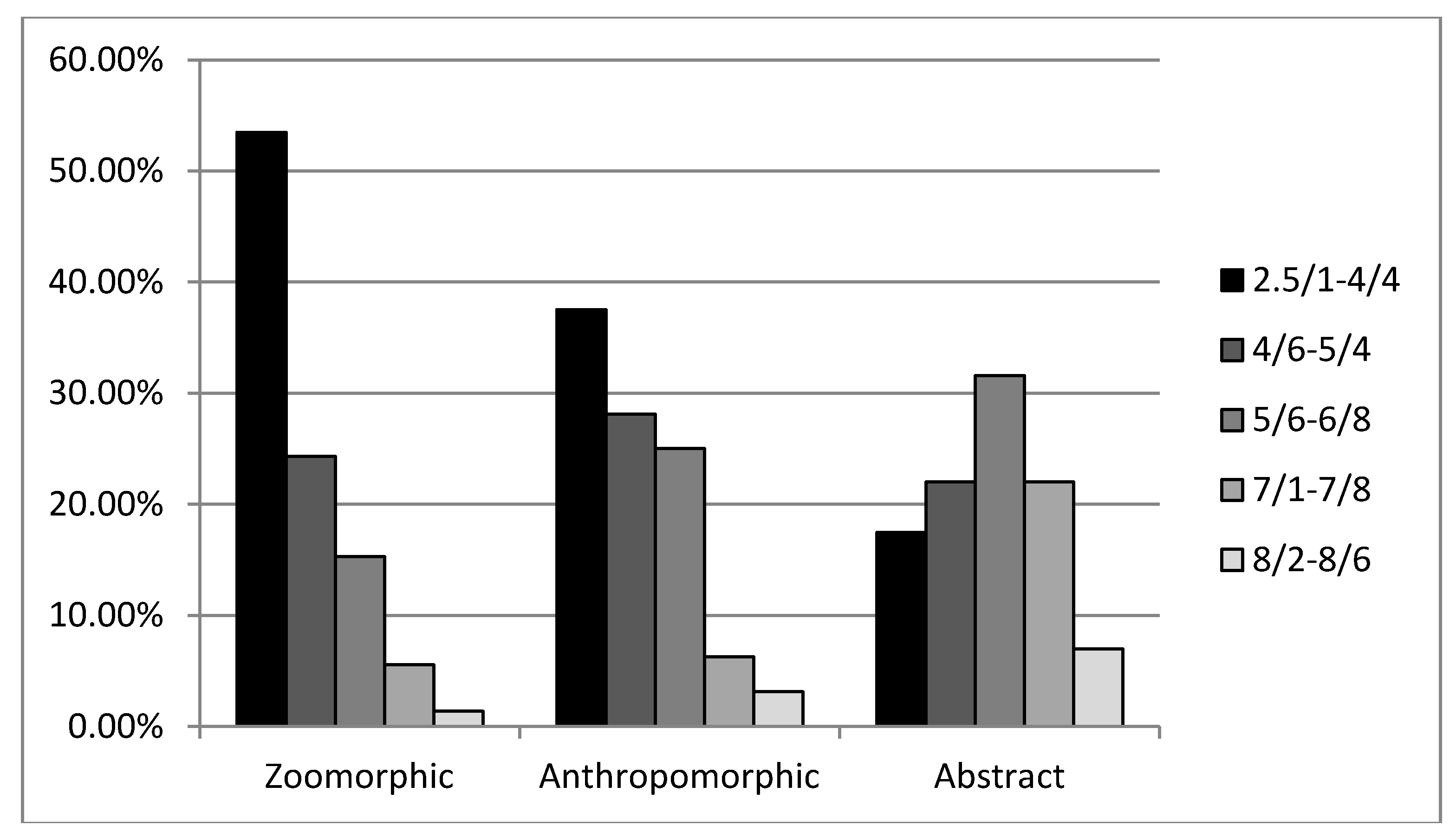

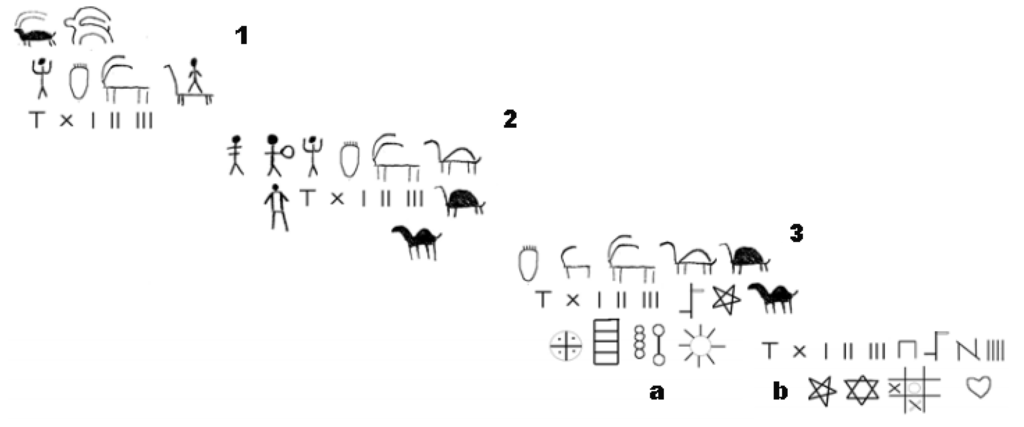

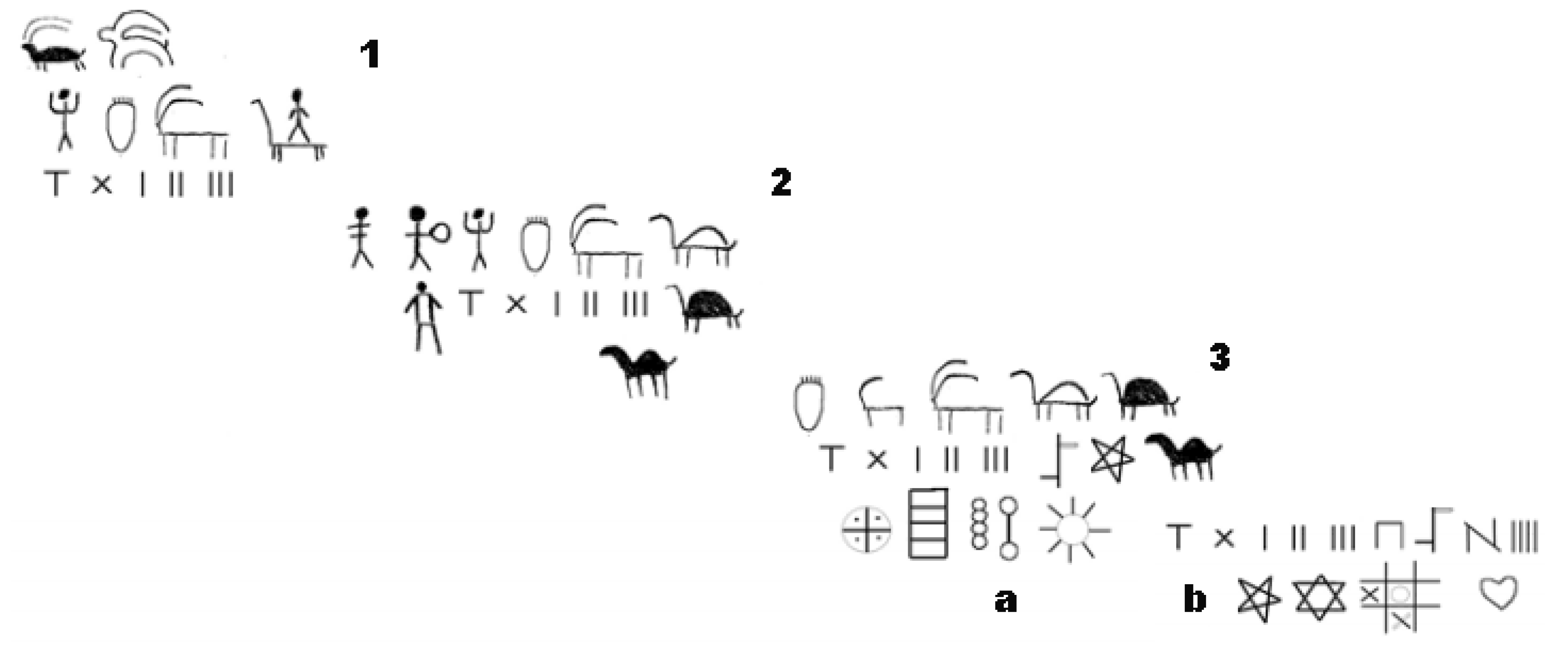

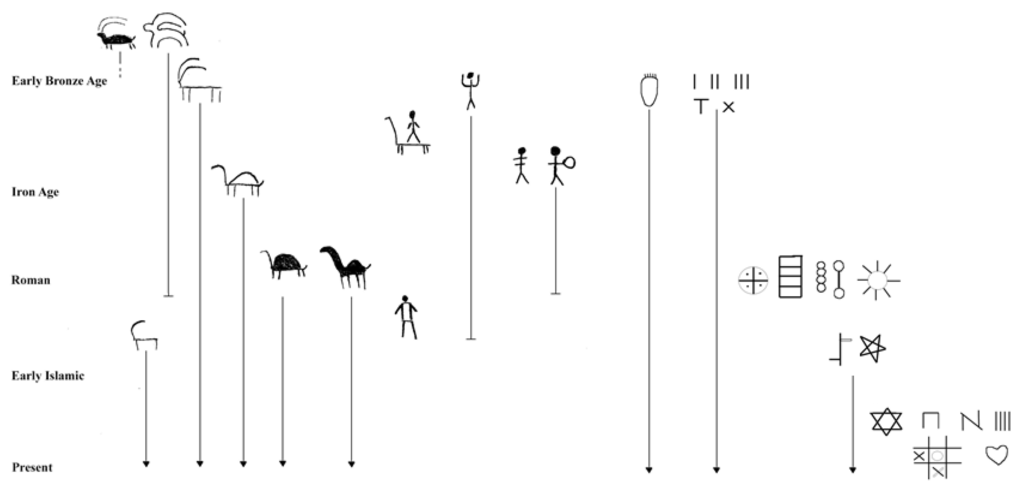

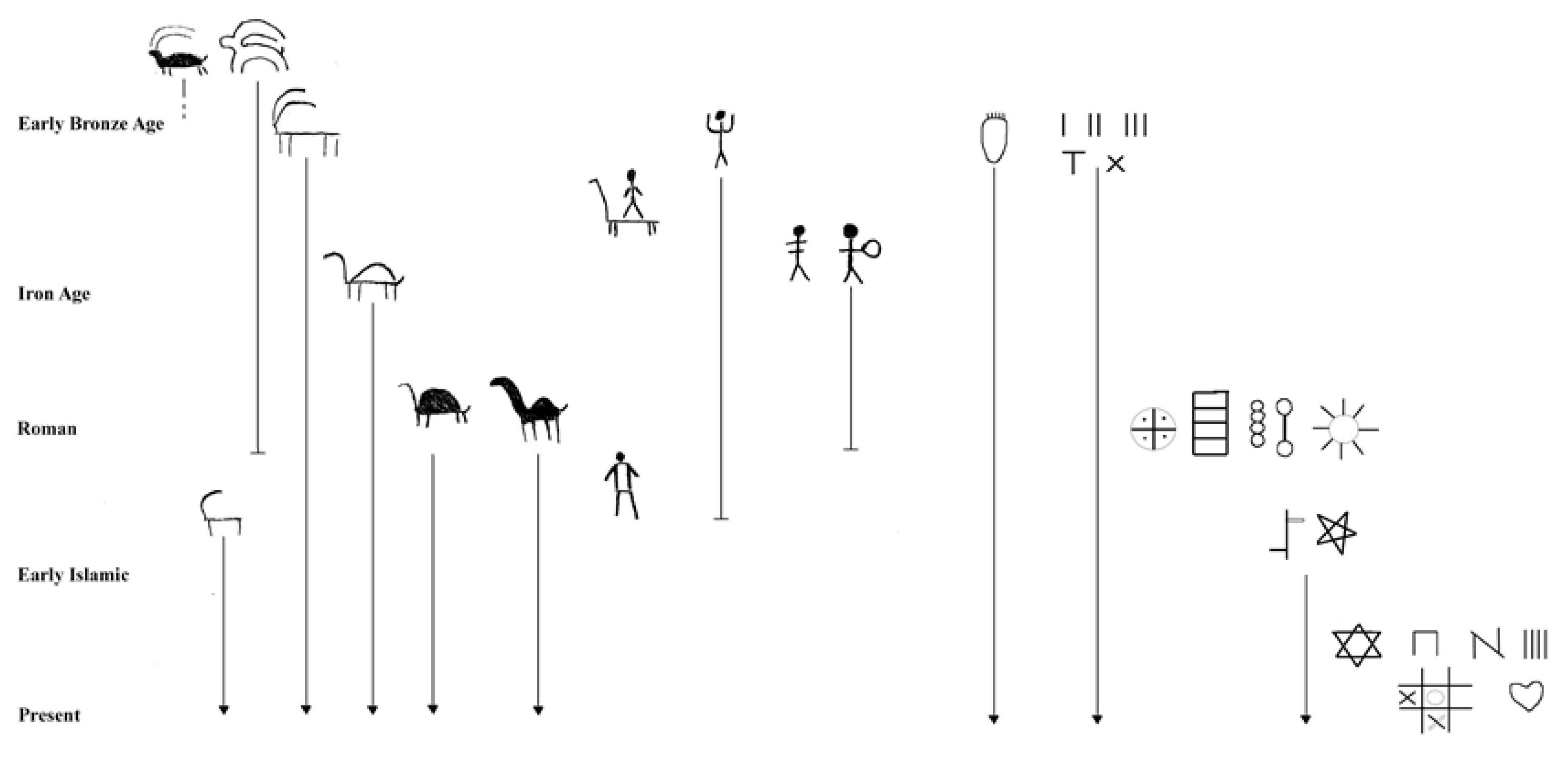

The patina color, noted as part of the fieldwork documentation (using Munsell Soil color chart sheet hue YR 7.5), was examined in two fashions: determining engraving phases for single panels by reference to relative hue (Figure 5 and Figure 6), and cross comparison of absolute patina color with motif type (Figure 7). Cross comparison of patina color and motif type included all documented elements. In considering different rates of patina development, the documented 30 hues were grouped into five groups, based on Munsell Color Chart classifications. In addition it must be taken into consideration that the earliest engraving phases of each panel need not be contemporary. Panels with more than one engraving phase were not all engraved during the same period; the panels were not all active simultaneously. Thus we cannot take the three phases of panel “A” and compare them to the first three phases of panel “B” or “C”. Nonetheless, examining 73 of Har Michia’s panels which exhibit clear relative chronology, certain general trends are apparent (Figure 7, Table 5 and Table 6). These trends from Har Michia were repeated at the rock art site of Giva’t HaKetovot (Eisenberg-Degen 2012) [9], supporting the Har Michia results. Thus, Figure 8 illustrates chronological trends in the appearance and disappearance of motifs and attributes and does not serve as an absolute chronological indicator. These trends are not discrete phases, but rather should be seen as modalities (with the latest divisible into two subsets), (Figure 9), each with its characteristic composition of motifs. 1. Within the earliest engraving phases are “ibexes”, isolated or in a group, at times in association with an “anthropomorph”; other elements to appear are “dogs”, “equids”, “tools and enclosures”; 2. The second phase includes camels. 3a–3b. The third phases includes more "abstract" elements and relatively fewer “zoomorphic” and “anthropomorphic” elements. It stills remains impossible (and methodologically ungrounded) to date a single, isolated element strictly based on its patina shade.

Figure 7.

“Abstract”, “Zoomorphic” and “Anthropomorphic” Percentages Present within Each Patina Shade. Each motif type adds up to 100%.

Figure 7.

“Abstract”, “Zoomorphic” and “Anthropomorphic” Percentages Present within Each Patina Shade. Each motif type adds up to 100%.

Table 5.

Panel 33–113 Engraving phases according to re-vanished shade. As explained above, the re-patinated hues are grouped together, therefore the eight layers of engraving seen by eye are reduced to five layers in the table.

| Layer 1 | Layer 2 | Layer 3 | Layer 4 | Layer 5 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Abstract" | 10 | 11 | 34 | 17 | 3 | 75 |

| “Horned Ungulates” (Ibex) | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | ||

| “Un-Identified Zoomorph” | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| “Camel” | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| “Equid” | 1 | 1 | ||||

| “Dog” | 0 | |||||

| “Anthromorph” | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| “Foot Print” | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Total | 16 | 18 | 39 | 19 | 4 | 96 |

Table 6.

Panel 25–31 Engraving Phases according to re-patinated shade.

| Layer 1 | Layer 2 | Layer 3 | Layer 4 | Layer 5 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Abstract” | 20 | 44 | 91 | 24 | 5 | 184 |

| “Horned Ungulate” | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| “Un-Identified Zoomorph” | 1 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| “Camel” | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| “Equid” | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| “Dog” | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| “Anthropomorph” | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| “Anthropomorph Riding” | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| “Tool/Weapon” | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| “Phallus” | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| “Building” | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 27 | 55 | 104 | 27 | 5 | 218 |

Figure 8.

Motif modalities (phases) in chronological sequence. Numbers 1–3 indicate the different modalities (phases). Modality 3 may be subdivided into a and b, earlier and later.

Figure 8.

Motif modalities (phases) in chronological sequence. Numbers 1–3 indicate the different modalities (phases). Modality 3 may be subdivided into a and b, earlier and later.

Figure 9.

Proposed Chronology based on Super-positioning and Engraving Phases.

Figure 9.

Proposed Chronology based on Super-positioning and Engraving Phases.

Summarizing these analyses:

- "Abstract" elements are a relatively late development, appearing in large numbers in later engraving phases.

- “Ibexes”, the most commonly depicted “zoomorphic” element, are present in a range of engraving phases in single panels. Ordering them by engraving phase according to their stylistic features and compositional setting demonstrates that the linear, minimalistic “ibex” with four legs, two long scimitar horns and a short upturned tail was stable type, present in most phases and apparently extending over much of the sequence (for example nos. 32 and 38 in Figure 10).

- In spite of differences present in setting, “ibexes” in general are found throughout the rock art sequence. For example, panel 33–113 with eight engraving phases presents a “hunting scene” in the earliest engraving phase followed in the next phase by several “male ibexes” not associated with any anthropomorphic figure. “Camels”, “ibexes”, and a large number of "abstract" elements were added in later engraving phases. Motifs of the final three phases consist almost entirely of "abstract" elements. Similarly, panel 25–31 (Figure 11) is relatively large and dense, engraved with 218 recorded elements and at least five clearly defined engraving phases. In the earliest engraving phase, an “anthropomorph”, a “phallus”, and an “ibex” are depicted. “Ibexes” continue as the dominant motif in the following three phases.

- The final phases consist almost entirely of "abstract" elements. This pattern is repeated in panel 39–69 where three engraving phases have been noted. The first phase includes two “ibexes” and an “un-identified zoomorphic” element. The second and third phases present strictly “abstract” elements.

3.3. Constructing a Relative Chronology

A relative chronology was constructed by combining super-positioning and engraving phases (Figure 8). Beyond the general categories reviewed above, engraving phases include depictions of “domestic animals” and inscriptions in a number of languages. “Equids”, “camels”, “weapons” and inscriptions are all motifs introduced into an existing rock art tradition at a certain point in time. Dating the period in which each motif type was potentially first engraved anchors the relative chronology, transforming it into an absolute chronology.

3.3.1. “Equids”

“Equid” in the present paper serves as a general name for the horse—donkey family and their offspring, the mule, and hinny. Each animal has distinctly different physical characteristics. Donkeys have short legs, a wide head and long ears. They are robust animals with the ability of carrying heavy loads. Adapted to the harsh climate of the Negev desert they graze on desert scrub (Borowski 1998:90–93; Stadelmann 2006) [23,24]. Horses have long legs, a slender head, and a mane running from its head down its neck. They have a delicate build and require care, such as protection for their hooves (Borowski 1998:98–101) [23]. Mules and hinnies, both hybrids between a horse and a donkey, also differ morphologically (Borowski 1998:108–111 [23]; Clutton-Brock 1981:94–96 [25]), but no distinctions were possible in the petroglyphs.

Figure 10.

Panel 33–113 with Several Engraving Phases. Panel measures 92 × 111 cm.

Figure 10.

Panel 33–113 with Several Engraving Phases. Panel measures 92 × 111 cm.

The majority of engraved “equids” are presented in simple, minimalistic fashion. Given that proportion and minute details seem to have been of little importance to most mark makers, distinction between the different kinds of equids is difficult at best. Donkeys are slower than horses and were not ideal for hunting (Borowski 1998:93 [23]; Hizmi 2004 [26]), but even this does not allow identification of, for example, horses in a hunting scene.

Between the horse and donkey, donkeys were domesticated and introduced into the region first, in the 4th millennium BCE, the Early Bronze Age I (e.g., Milevski 2009) [27], or perhaps as early as the Chalcolithic period (Horwitz and Tchernov 1989) [28]. They were utilized both as pack and riding animals (Hizmi 2004 [26]; Stadelmann 2006 [24]). Osteological evidence points to a Middle Bronze Age II—Late Bronze Age date (mid-second millennium BCE) for the introduction of horses into the southern Levant, and they were common by the Iron Age II (Wapnish 1997) [29]. Given the difficulty of distinguishing between horse and donkey, a terminus post quem of the mid-4th millennium BCE is reasonable.

3.3.2. “Camels”

Camels were introduced into the region fully domesticated in the Late Bronze IIB (thirteenth century BCE) and were fully integrated into trade economies by the Iron Age II (ca. 900 BCE) (Jasmin 2006 [30]; Wapnish 1981 [29]; Rosen and Saidel 2010 [31]). It is possible that some camel petroglyphs represent wild camels rather than domesticated ones but, as morphological changes between wild and domesticated camels such as length of hair and size of teeth (Ucko and Dimbleby 1968:208) [32] are not indicated in graphic representations such as petroglyphs, the “wild camel” representation could only be recognized as such based on a pre-LB/IA dates. Even though fragments of camel bones were recovered from Early Bronze Arad and interpreted as hunted wild camels (Amiran 1978:87) [33], at present there is no evidence to support the recognition of wild camels in the central Negev rock art. Assuming that all “camel” petroglyphs represent domesticated camels then a terminus post quem Late Bronze/Iron Age date is warranted. A post-Iron Age II date is reinforced by the depictions of “ridden camels”. In all examples of riders on camel back, the rider is placed high on the hump, indicating the use of the North Arabian saddle, introduced no earlier than 500 BCE (Bulliet 1977:87) [34].

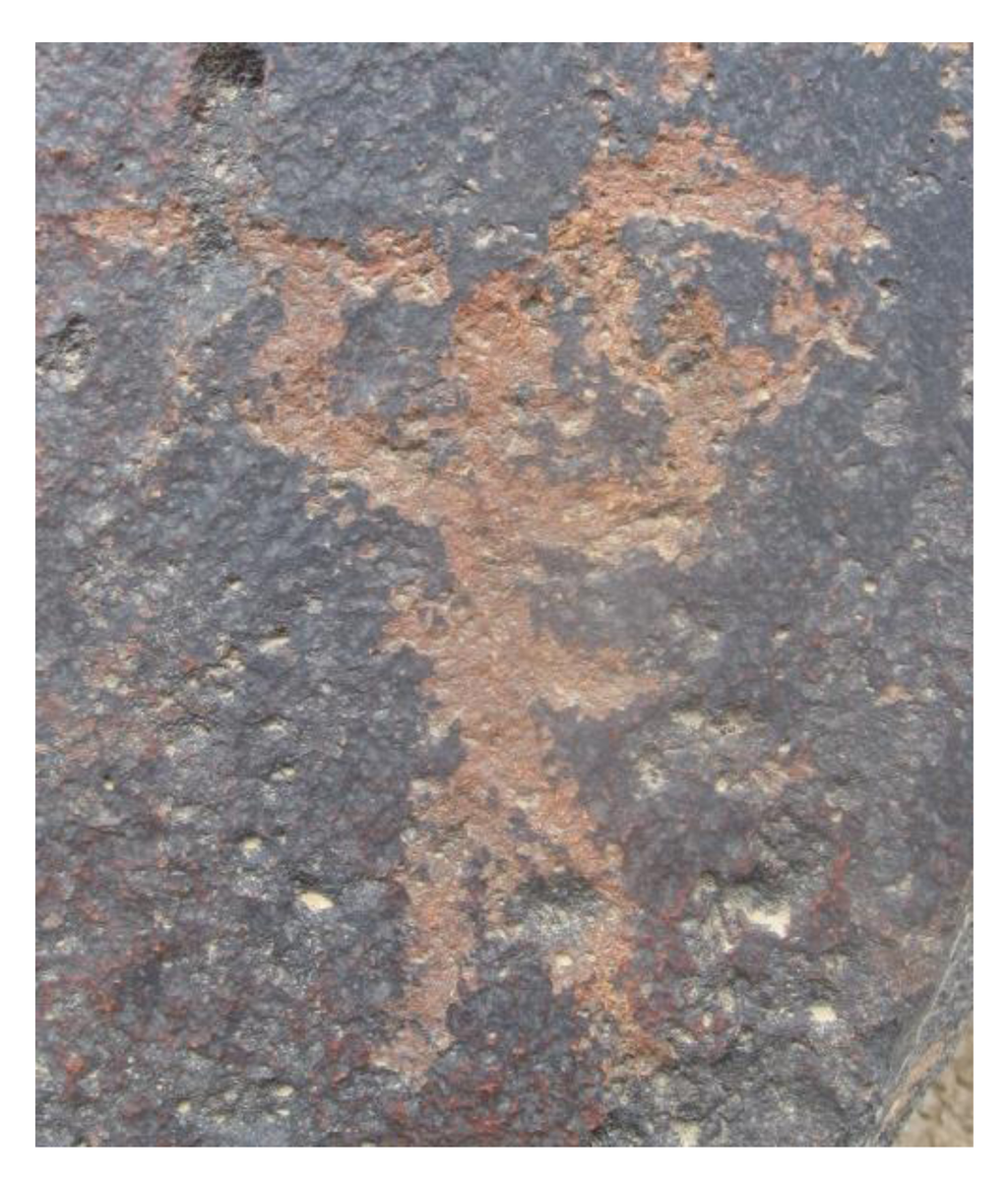

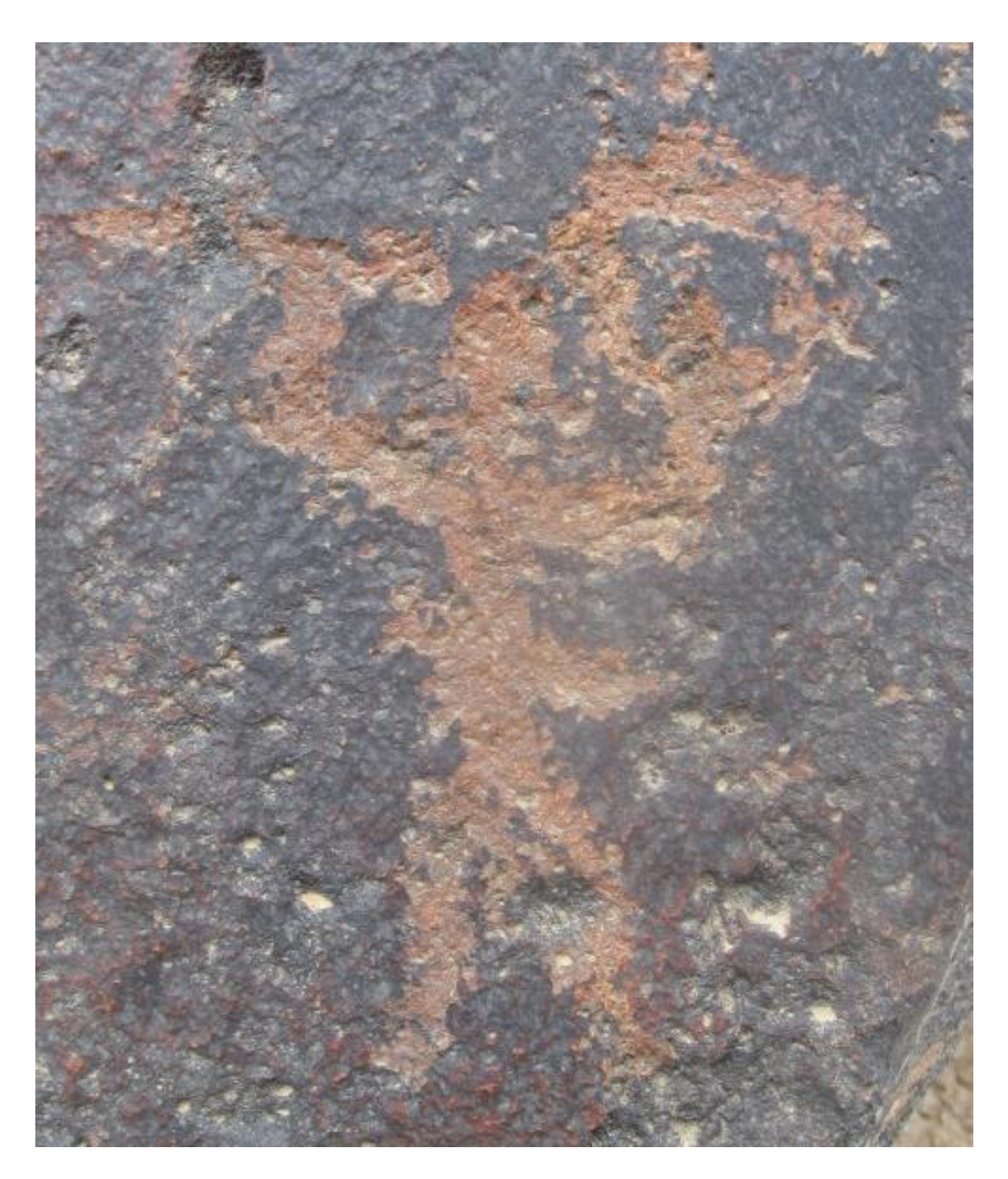

3.3.3. Weapons

At Har Michia 145 “anthropomorphic” figures were recorded. These figures may be divided into 12 “types” based on whether they are “mounted”, the placement of the “arms”, and the “weapons” held. One such type has a “line at the waist” (Figure 12). As the line at the waist is not held, indicating an independent accessory, it might be interpreted as a “belt”, “sword”, or “sheath” tied in place. Figures with a “line at the waist”, sometimes horizontal and sometimes diagonal, are presented as isolated figures “standing”, “mounted on a horse”, engaged in “combat”, or “hunting”. The line at the waist of the Har Michia figures is almost horizontal, in some instances thick and long. It is plausible that it represents a “sheath”. Comparing these representations to more detailed representations of “anthropomorphs” in different media with a similar line at the waist strengthens the assumption that the line is a “sheath”, perhaps suspended over the shoulder (cf. Potts 1998, Figure 10) [35]. None of the Har Michia petroglyph representations offer details sufficient for recognizing an actual sword or dagger. Examining the “anthropomorphs” in a literal fashion, we can say that the implement at their waist must be a minimum of 70 cm long for it to extend on both sides of the body. Long swords exceeding 70 cm in length were introduced into the Mediterranean in the late second millennium BCE, no earlier than 1200 BCE. Prior to this date, cutting and thrusting weapons consisted of daggers, dirks, and sickle blade daggers, none of which exceeded 50 cm (Drews 1993:193–208; Philip 1989:102–143) [36,37]. The sword (reaching an average length of 75 cm) replaced these short bladed weapons and became the most commonly used weapon from the Late Bronze Age through the Hellenistic period. During the Hellenistic period, the lance and spear served as the preferred weapon. As the lance and spear replaced the sword, the sword was reduced in length transforming it back into a dirk. Although the Har Michia “anthropomorphs” present only minimal detail, we may interpret the line at the waist as the “sheath” of a straight bladed sword rather than the “sheath” of a dagger or curve bladed sword. This identification places these figures roughly within an 800 year span, ranging from 1200 BCE to the mid fourth century BCE. Parallels to the Har Michia “anthropomorphs” from a wide range of sites and regions (Cornelius 1994:180–181, Figure 37 [38]; Negbi 1976:29 Figure 42, p. 162, Plate 20 no. 1311 [39]; Potts 1991:95–96, Figure 137 [40]; Rothenberg 1972:119–124 [2]) reinforce this proposed date.

Figure 11.

Panel 25–31 with 218 Elements. Panel measures 270 × 93 cm.

Figure 11.

Panel 25–31 with 218 Elements. Panel measures 270 × 93 cm.

Although a terminus post quem of Middle Bronze Age is indicated from the mid-length straight sword and round shield depicted, the central Negev has virtually no settlement throughout the second millennium BCE (based on the number of sites as documented in the Archaeological Survey of Israel—Negev Emergency Survey monographs, see for example the following surveys: Avni 1992:14*–18*; Cohen 1981:vii–xi; Haiman 1986:14*–20*; Lender 1990:xix–xxiii; Rosen 2009) [41,42,43,44,45]. Therefore, it is more likely that the straight bladed sword and use of round shields in the Negev reflect an Iron Age or later date. The round shield continued to be in use through Roman times (Gonen 1979:75–79) [46].

Figure 12.

“Anthropomorphic” Motif with a “Line at the Waist”. Element 37-9-4 measuring 11 × 13 cm.

Figure 12.

“Anthropomorphic” Motif with a “Line at the Waist”. Element 37-9-4 measuring 11 × 13 cm.

3.3.4. Inscriptions

At Har Michia 27 “inscriptions” were documented. Most of the documented inscriptions consist of single words and are most likely personal names (Pers. Comm. Robert Hoyland), similar to the Hismaic inscriptions of Southern Jordan (Corbett 2012) [47]. Beyond the seven inscriptions that could not be deciphered, the inscriptions fit into general language groups based on the shape and use of the letters. The majority of inscriptions were Arabic, several of which seem to be of a recent date (Pers. Comm. Nitzan Amitai Preiss). Five inscriptions are in a North Arabian Script, pre-dating modern Arabic. Languages such as Thamudic, Nabatean, Safaitic and Hismaic were pre-Islamic and texts in these languages in the various North Arabian scripts have been found from southern Syria and Iraq through Yemen and Upper Egypt (Macdonald and King 2000:436–438) [48]. In Arabia these scripts were in use as early as the 8th century BCE. In the Negev, North Arabian script is usually dated to a timeframe ranging from the 4th c. BCE through the mid-3rd century CE. Thamudic inscriptions of the Negev date to the 1st–2nd c. CE (Halloun 1990:36*) [49]. Nabatean inscriptions in Sinai are dated as late as the second half of the 4th c. CE (Negev 1977:73) [50]. Arabic was introduced with the Arab conquest in 640 CE and numerous Arabic inscriptions in the Negev are dated to the mid-7th c. CE, suggesting a period of intensive activity in the region (Sharon 1990:9*) [51].

4. Rock Art as a Reflection of Symbols, Values, and Change within the Society

4.1. The Introduction and Integration of the Domestic Camel into Negev Culture

At Har Michia “camels” (Camelus dromedarius) represent the second most depicted “zoomorph” (not including un-identified zoomorphs). The Har Michia “camel” petroglyphs take several forms. Some were mounted by an “anthropomorph” holding a “steering stick” or “engaged in combat”. Most “camels” were not “mounted”, and not associated with “people or other animals”. “Camel” petroglyphs were usually single representations though, at times, pairs of “camels” were engraved. The form of the “camel” may be outlined, fully pecked or linear. The most common “camel” form is linear, with a line representing the body, another for the neck, and four lines serving as legs. A curved line placed on the body forms an outlined hump. Little attention was paid to proportions between the body size, length of legs, neck, or hump size. Roughly 50% of the “camels” with clearly discerned tails show them up-turned (Figure 10, right side, behind panel 33–113).

Up-turned tails help identify the depicted “camel” as a female, or she-camel. The camel tail thus becomes a gender specific attribute. Camel herders see up-turned tails as an indication of a pregnant camel (Wosene 1991) [52]. In Ancient North Arabian languages there is a distinction between male and female camels and petroglyphs of she-camels in Transjordan and Syria are titled bkrt (Arabic bakra) and are presented with up-turned tails (Winnett 1957 nos. 60 and 803; Winnett and Harding 1978 for example nos. 2018, 2112, 2763, 2731 and 3615b) [53,54]. Male camels, gml (Arabic jamal) or bkr (young male camel) are presented with slack tails (Corbett 2010:126) [55]. This artistic convention was also applied in the Negev (Eisenberg-Degen 2006:86) [56]. No clear male “camels” have been documented in Negev rock art thus far.

As noted above, all “camel” petroglyphs are assumed to be of domestic camels and date no earlier than the Late Bronze/Iron Age. The introduction of the camel into the rock art repertoire is not only an expression of the new beast of burden, but reflects the emergence of a new and important factor in pastoral life. The camel is a strong pack animal that can carry up to 200 to 325 kg of goods and travel for several days without watering (Gauthier-Pilters and Dagg 1981:110) [57]. This fact altered the nomadic lifestyle as migrating long distances with heavy equipment such as hair tents became possible, thus increasing mobility and flexibility (Rosen 2008 [58]; Rosen and Saidel 2010 [30]). Camel pastoralists were able to traverse deep into the desert, much farther than sheep, goat, or cattle pastoralists could venture (Corbett 2010:148–150) [55]. Beyond transportation, the she-camel serves as a reliable source of wool, dung (used as fuel), milk, and when needed, meat (Köhler-Rollefson 1993:182) [59]. Thus, the camel became a main source of milk, transportation, and wealth in the pastoral society. The “camel” petroglyphs, appearing in the middle of the Negev rock art sequence, reflect a milestone in the history of the Negev.

Nevertheless, the “camel” petroglyphs of Har Michia (and the Central Negev in general) do not mirror the camel’s use. Few loaded camels and caravans are depicted. The sex of the “camel” is depicted through some attributes, but teats are few and there are no examples of camel milking in the rock art. The “camel” petroglyphs are not a reflection of everyday life but rather serve as a type of meaning enriched icon. In fact more than any of this, the camel achieved a symbolic power in Bedouin society reflected, for example, in the large vocabulary associated with the animal and in the existence of a pre-Islamic genre of poetry dedicated to it (Stetkevych 1986, 1993) [60,61]. It is this symbolic element, perhaps in this sense like the “ibex” that seems to be most reflected in the rock art.

4.2. The Emergence of Islam

In the mid seventh century CE, Arab tribes expanded into the Negev (Avni 1994) [62]. The Arab conquest did not abruptly change the life of the Negev population; sites were not demolished and the ceramic assemblages show only a slow and gradual change with the introduction of new vessel types (Avni 1996:8; 2009; Nahlieli 2007) [63,64,65]. Sites, both sedentary and nomadic, were gradually abandoned and certainly by the beginning of the 10th century CE the Central Negev was but sparsely inhabited. Arabic inscriptions dated to the 8th–10th centuries CE support these dates (Magness 2003:137 [66]; Rosen 2000; 147 [67]; Rosen-Ayalon et al. 1982 [68]; Sharon 1990 [51]; 1993 [69]). The rock art offers new insights into this period.

Towards the end of the rock art sequence, as expressed in the Har Michia panels Arabic inscriptions, simple “abstract” elements and “footprints/sandal prints” appear in growing numbers. The new elements slowly replaced the existing repertoire of “anthropomorphic and zoomorphic” figures. This new and limited repertoire of images suggests that the mark makers were governed by non-iconic, religious restrictions, marking a major change in the nature of the rock art.

Approximately 600 Arabic inscriptions from the Central and Western Negev have been documented and published (Nevo et al. 1993 [70]; Rosen-Aylon 1988 [71]; Rosen-Ayalon et al. 1982 [68]; Sharon1981 [69], 1985 [70]; 1990 [51]). Of the hundreds of inscriptions, few are accompanied by “zoomorphic” elements and even fewer by “anthropomorphic” motifs (Haiman 1995 [74]; Magness 2003:138–141 [66]; Nevo et al. 1993 Pl 2–30 [70]). Some inscriptions are accompanied by “abstract” elements, usually a single element (see for example Nevo et al. 1993: MA 4207A, PL 15, and MA 4256E, PL 17) [71]. These changes detected in the rock art sequences reflect the tribal Islamic character of the Negev population. This phase in the central Negev came to an end around the 10th century CE when both the village and nomadic systems collapsed and the region became more or less abandoned.

4.3. Infiltration and Settling of the Recent Bedouin in the Central Negev

The most recent infiltration of tribal groups into the central Negev occurred in the late 17th and early 18th centuries AD (Bailey 1980; Israel 2006) [75,76]. The final rock art sequence, undoubtedly attached to this wave of settlement (sensu latto), continues the non-iconic character of the previous phase. Now “abstract” elements are repetitively engraved. Ethno-historic data suggests that several of the "abstract" motifs documented at Har Michia are Bedouin tribal markings (wusum).

The “abstract” element category is a diverse one with 75 different forms. A number of these have been identified as tribal markings and traced to tribes such as the 'Azāzma confederation and the Janabib (Al-‘Aref 1937: 63–100; Ashkenazie 1957) [77,78]. The 'Azāzma have been present in the central Negev from at least the mid 19th century to this day (Bailey 1978; Marx 1974:16; Palmer 1871: 360–363) [79,80,81]. Few other marks could be tied with certainty to specific tribes since documentation of tribal markings began only in the late 19th century and often consisted of a verbal description rather than a visual one (see for example Al-‘Āref 1937: 63–130) [77]. Other tribal marking lists were composed in more northern regions and do not include the tribal markings of the Negev tribes (Ashkenazie 1957 [78]; Conder 1883 [82]). To these, some more recently collected anthropological information have been added (Pers. Comm. Allan and Doron Degen). Some “abstract” elements may be markings of tribes no longer residing in the region, such as those documented and traced in Saudi Arabia (Khan 2000:105) [83] and recognized in Upper Egypt (Winkler 1938:11) [84].

The frequency of a specific element distributed over the landscape helps identify the element as an ownership marker (Hartley and Wolley Vawser 1998) [85]. A good example of this is the “door” shaped 'Azāzma tribal marking, which was documented 102 times at Har Michia alone. These were sometimes placed several times on a single panel. Tribal markings are often engraved in a simple form. They were not emphasized in their placement, size or thickness of an engraved line. In a sense these marks are doodles and were not necessarily intentionally formed as “sign posts” of ownership. Shepherds doodling as a pastime have been documented in Iran (Watson 1979:203) [86] and Mongolia (Demattè 2004) [87] and many of the tribal marks recorded in the Negev seem to have originated from such doodling and were not directly intended as ownership marks; they are spread throughout the tribe‘s pastoral territory and are not placed strictly on the periphery, such as formal boundary inscriptions from northern Israel. However, even when a tribal mark was not engraved intentionally as a territorial marker, it did and does serve as one. Bedouin of Saudi Arabia, belonging to the same general tribal culture, were able to recognize “abstract” elements as tribal marks of ancient tribes no longer residing in their region (Khan 2000:1–5) [83]. Thus, even when not engraved with a clear intent in mind, tribal markings transfer a meaning of presence and hence, ownership.

4.4. Hunt Scenes and the Significance of the Ibex

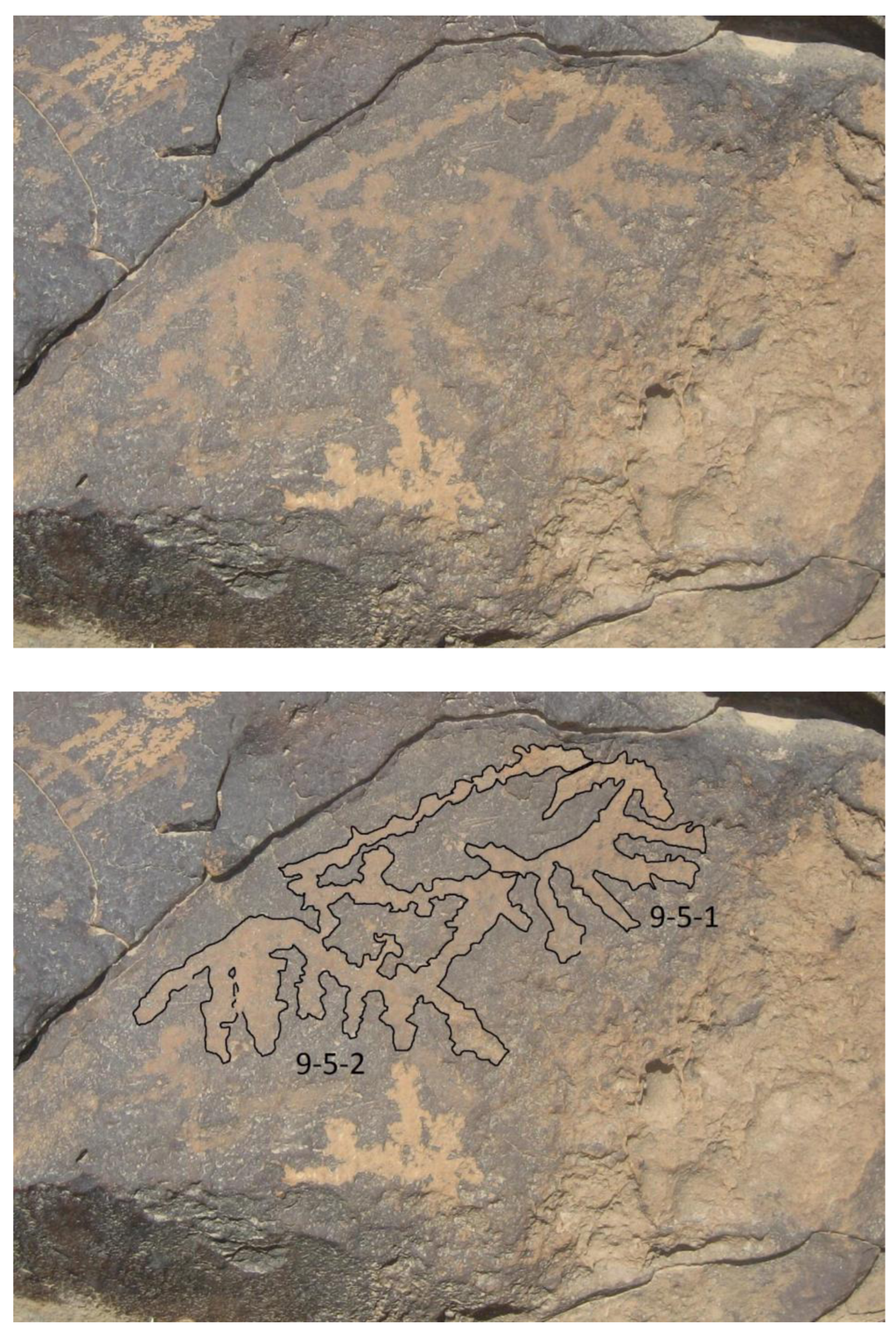

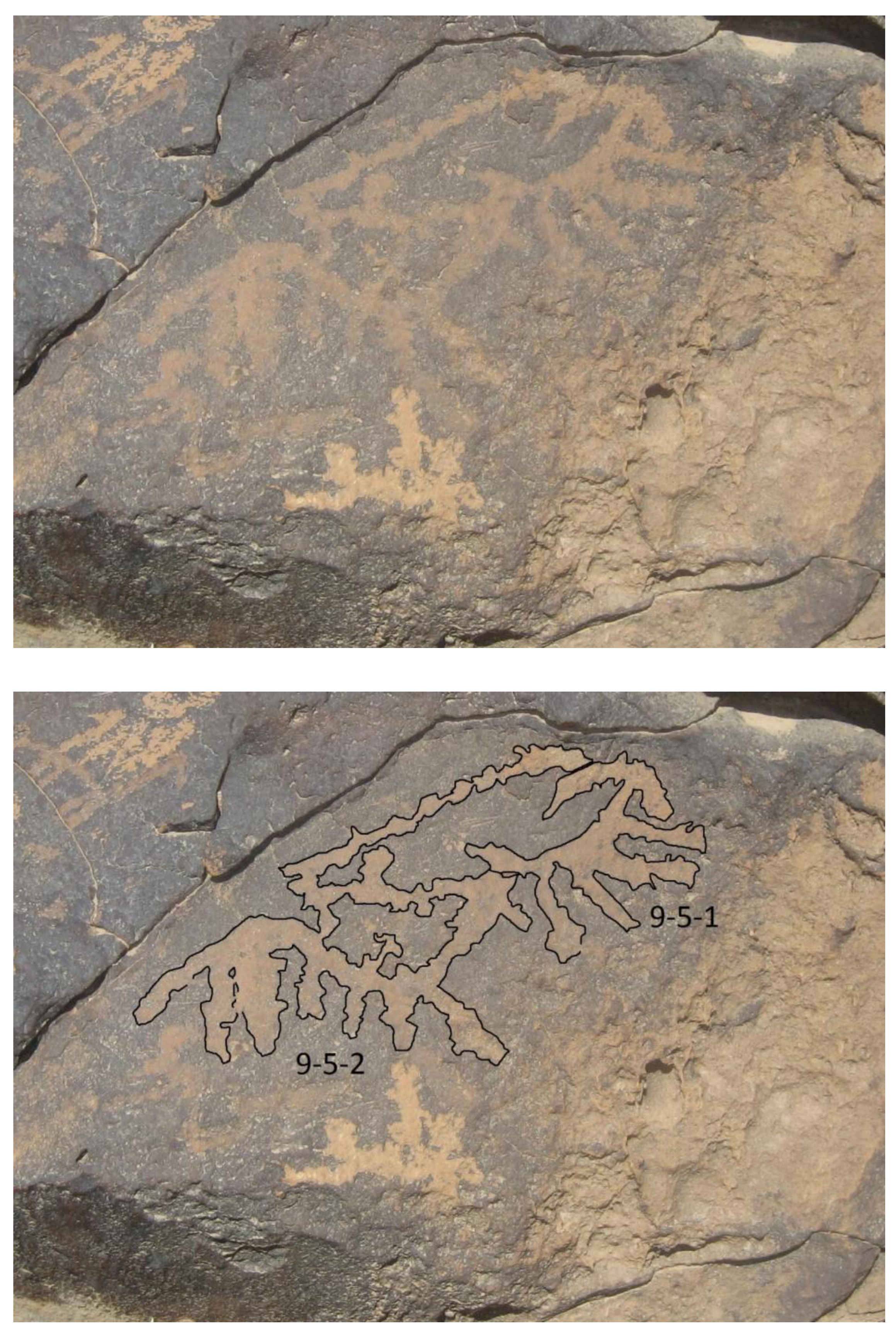

The final section of this paper concentrates on the “ibex” motif. The “ibex” was one of the first (if not the first) motif to emerge with the Negev rock art. The “ibex” dominates the early rock art phases but is consistently engraved and retouched through the entire rock art sequence. The Har Michia “hunting scenes” documented need not represent specific historic (or prehistoric) events and these panels seem to hold more of a symbolic meaning and importance than a literal one. Thus, in most “hunting scenes” the “hunted animal” is a “mature male ibex”. This depiction does not accord with the osteological evidence which points towards gazelle being the most hunted animal from the Chalcolithic/Early Bronze Age (e.g., Dayan et al. 1986 [88]; Hakker-Orion 1999:327 [89]; 2007 [90]; Horwitz and Tchernov 1989 [28]; Rosen and Horwitz 2005 [91]). “Studying hunting” scenes from Southern Jordan accompanied by Thamudic inscriptions, Corbett (2010:180–182) [55] turns to pre-Islamic jāhilīyah poetry imagery and metaphor to decipher the images. He offers a number of interpretations including that the portrayed “hunt” conveys aspects of the transition from adolescence to adulthood, that the hunt is emblematic of the social covenant between group members, or that the “hunt” represents human destruction of the natural animal world. In any case the South Jordanian panels show explicit “hunting” scenes of a symbolic import engraved by a pastoral society, and not reflecting economic imperatives. The “hunting scenes” of the Negev were also engraved by a pastoral society and also bear symbolic meaning and importance. In addition to these hunting scenes pairs of “ibexes” and an “ithyphallic anthropomorph”, “ibex” and (human) “foot/sandal prints”, and “ibex” and “predator” combinations enhance the idea that not only are they meaning embedded, but the “ibex” image itself is of importance (Figure 13).

“Ibexes” are present in all phases of the Har Michia panels, accounting for the majority of motifs of the first engraving phases. Looking at the frequency of motifs as presented in all engraving phases, “horned ungulates” account for 47% of the “zoomorphic” elements, 74% of these clearly represent mature male “ibexes”. “Ibexes” dominate most Negev rock art corpuses, for example At Har Karkom “ibexes” account for 57.5% of all “zoomorphic” elements (Anati and Mailland 2009:25) [92], and in the two Late Bronze Age panels at Timna few animals other than “ibexes” are presented (Rothenberg 1972:120–123) [2]. The importance of “ibexes” in the Negev rock art is best demonstrated by their presence and dominance in rock art sites some distance from the “ibexes” natural habitat. At Giva’t HaKetovot “horned ungulates” dominate the sample representing 53% of all “zoomorphic” elements (of these, 78% are unquestionably recognized as mature male ibexes.) Gazelles (Gazelle dorcas), the dominant ungulates of this region, frequenting Timna and Har Michia as well, are rarely depicted. It is clear that ibexes held an important role for the mark markers’ even if their precise meaning at present remains elusive. The true significance of “ibexes” petroglyphs is that they reflect a long symbolic continuity for indigenous Negev cultures.

Figure 13.

“Hunt Scene”. “Anthropomorph” mounted on “equid” (element 9-5-2 measuring 24 × 29 cm) “hunting horned ungulate” (element 9-5-1 measuring 14 × 20 cm).

Figure 13.

“Hunt Scene”. “Anthropomorph” mounted on “equid” (element 9-5-2 measuring 24 × 29 cm) “hunting horned ungulate” (element 9-5-1 measuring 14 × 20 cm).

5. Conclusions

In the construction of a chronological sequence for the rock art of the Negev two major historical changes stand out, the adoption of the domesticated camel and the infiltration of Islamic tribes into the region. The relative and absolute chronologies formed, based on the Har Michia data may be extended to other Central Negev rock art sites. Thus, a preliminary examination has shown that the Har Michia sequence is repeated at Giva’t HaKetovot (the “Hill of the Inscriptions”), a rock art site in the western Negev and the sequences offers a model through which to approach all Central Negev rock art.

When listing the motifs depicted, the possible motifs and subjects not engraved are also of interest. Landscape, flora, and an endless list of activities which sustained the Negev population on a daily basis (herding and pasturing, social gatherings, tents, nuclear family relationships, explicit religious symbols) are not presented or are extremely rare. This conclusion contradicts the concept that Southern Levantine rock art reflects the economy and everyday life of the local population, a view held by several researchers (e.g., Anati 1962:185–187 [4]; Nevo 1991:104–105 [1]; Oxtoby 1968:25 [93]; Sharon 1990:9* [51]).

The mature male “ibex”, an image which appears in the Negev rock art thousands of times, was engraved throughout all periods, without relation to the mark maker’s ethnicity, religion, political regime, or economic base. Though the “ibex” was a meaningful image in each period, the meaning the “ibex” held probably differed and was adapted to each society, their beliefs and needs. This continuity in symbolism constitutes a basic feature of the desert society.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Y.D. Nevo. Pagans and Herders: A Re-Examination of the Negev Runoff Cultivation Systems in the Byzantine and Early Arab Periods. Midreshet Ben-Gurion, Israel: IPS Ltd., 1991. [Google Scholar]

- B. Rothenberg. Timna Valley of the Biblical Copper Mines. London, UK: Thames and Hudson, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- E. Anati. “Depiction of human beings in ancient rock drawings.” Bull. Isr. Explor. Soc. 20 (1956): 1–12, (Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- E. Anati. Palestine before the Hebrews. London, UK: Jonathan Cape, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- E. Anati. “Rock Art in Israel.” In The Art of the Stone Age: Forty Thousand Years of Rock Art. Edited by H.G. Bandi. Tel Aviv, Israel: Devir Ltd., 1965, pp. 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- E. Anati. “Rock Art in Central Arabia.” In The ‘Oval-Headed’ People of Arabia. Louvain, Begium: University of Louvain, 1968, Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- E. Anati. Har Karkom in the Light of New Discoveries. Capo di Ponte, Ital: Studi Camuni Edizioni del Centro, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- R.G. Bednarik, and M. Khan. “The rock art of southern arabia “reconsidered”.” Adumatu 20 (2009): 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- D. Eisenberg-Degen. “Rock Art of the Central Negev: Documentation, Stylistic Analysis, Chronological Aspects, the Relation Between Rock Art and the Natural Surroundings, and Reflections on the Mark Makers Society through the Art.” Ph.D. Thesis, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel, 6 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- M. Khan. “A Critical Review of Anati's Books on 'The Rock Art of Central Arabia'.” Atlal 14 (1996): 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- R. Bednarik. Rock Art Science: The Scientific Study of Palaeoart. New Delhi, India: Aryan Books International, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- D. Hillel. Negev Land, Water, and Life in the Desert Environment. New York, NY, USA: Praeger, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- M. Evenari, L. Shanan, and N. Tadmor. The Negev the Challenge of a Desert. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- E. Orni, and E. Efrat. Geography of Israel. Jerusalem, Israel: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- S.A. Rosen. “Byzantine nomadism in the Negev: Results from the emergency survey.” J. Field Archaeol. 14 (1987): 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W.E. Krumbein, and K. Jens. “Biogenic rock varnishes of the desert (Israel) an ecological study of iron and manganese transformation by cyanobacteria and fungi.” Oecologia 50 (1981): 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.A. Pope, T.C. Meierding, and T.R. Paradise. “Geomophology’s role in the study of weathering of cultural stone.” Geomorphology 47 (2002): 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.S. Schneider, and P.R. Bierman. “Surface Dating Using Rock Varnish.” In Chronometric Dating in Archaeology. Edited by R.E. Taylor and M.J. Aitken. New York, NY, USA: Plenum Press, 1997, pp. 357–388. [Google Scholar]

- S. Macdonald. “The study of engraving techniques and patina.” Annu. Dep. Antiq. 26 (1981): 171. [Google Scholar]

- R.I. Dorn. Rock Coatings. Amsterdam, Holland: Elsevier, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- M. Fleisher, T. Liu, W. Broecker, and W. Moore. “A clue regarding the origin of desert varnish.” Geophys. Res. Lett. 26 (1999): 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Liu, and W.S. Broecker. “How fast does rock varnish grow? ” Geology 28 (2000): 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. Borowski. Every Living Thing Daily Use of Animals in Ancient Israel. Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- R. Stadelmann. “Riding the Donkey: A Means of Transport for Foreign Rulers.” In Timelines Studies in Honor of Manfred Bietak. Edited by E. Czerny, I. Hein, H. Hunger, D. Melman and A. Schwad. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2006, Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- J. Clutton-Brock. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge University, England: Cambridge University Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- H. Hizmi. “An Early Bronze Age Saddle Donkey Figurien frim Khirbet El-Makhurq and the Emerging Appearance oif the Neast of Burden Figuriens.” In Burial Caves and Sites in Judea and Samaria from the Bronze and Iron Ages. Edited by H. Hizmi and A. de Groot. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Antiquity Authority, 2004, pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- I. Milevsky. “A new fertility figurine and new animal motifs from the chalcolithic in the Southern Levant: Finds from cave K-1 at Quleh, Israel.” Paleorient 28 (2002): 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- L.K. Horwitz, and E. Tchernov. “Animal Exploitation in the Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant: An Overview.” In L’urbanisation de la Palestine á l’âge du Bronze ancient. Edited by P. De Miroschedji. BAR International Series (527); 1989, Volume II, pp. 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- P. Wapnish. “Middle Bronze Equid Burials at Tell Jemmeh and a Reexamination of a Purportedly 'Hyksos' Practice.” In The Hykso New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Edited by E.D. Oren. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The University Museum, The University of Philadelphia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- M. Jasmin. “The Emergence and First Development of the Arabian Trade across the Wadi Araba.” In Crossing the Rift Resources, Routes, Settlement Patterns and Interaction in the Wadi Arabah. Edited by P. Bienkowski and K. Galor. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 2006, pp. 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- S.A. Rosen, and B.A. Saidel. “The camel and the tent: An exploration of technological change among early pastoralists.” J. Near East. Stud. 69 (2010): 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P.J. Ucko, and G.W. Dimbleby. The Domestication and Exploration of Plants and Animals. London, UK: Gerald Duckworth and Co. Ltd., 1968. [Google Scholar]

- R. Amiran. Early Arad, the Chalcolithic Settlement and Early Bronze City I First-Fifth Seasons of excavation, 1962–1966. Jerusalem, Israel: The Israel Exploration Society, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- W.R. Bulliet. The Camel and the Wheel. London, UK: Harvard University Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- D.T. Potts. “Some issues in the study of the pre-islamic weaponry of Southeastern Arabia.” Arab. Archaeol. Epigra. 9 (1998): 182–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Drews. The End of the Bronze Age Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe CA 1200. B.C. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press, 1993, pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- G. Philip. Metal Weapons of the Early and Middle Bronze Ages in Syria-Palestine. BAR International Series 526(i); Oxford, UK, 1989, Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- I. Cornelius. The Iconography of the Canaanite Gods Reshef and Ba’al: Late Bronze and Iron Age I periods (C 1500-1000 BCE). Fribourg, Switzerland: Orbis biblicus et orientalis, 1994, pp. 180–181. [Google Scholar]

- O. Negbi. Canaanite Gods in Metal an Archaeological Study of Ancient Syro-Palestinian Figurines of Ancient Syro-Palestinian Figurines. Tel Aviv, Israel: Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- D.T. Potts. Further Excavations at Tell Abraq: The 1990 Season. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaar, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- G. Avni. Archaeological Survey of Israel Map of Har Saggi Northeast (225). Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Antiquities Authority, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- R. Cohen. Archaeological Survey of Israel, Map of Sde Boqer – East. Jerusalem, Israel: Publications of the Department of Antiquities and Museums, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- M. Haiman. Archaeological Survey of Israel Map of Har Hamran Southwest (198)10-00. Jerusalem, Israel: The Department of Antiquities and Museums the Archaeological Survey of Israel, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Lender. Archaeological Survey of Israel, Map of Har Nafha. Jerusalem, Israel: Publications of the Department of Antiquities and Museums, 1990, please delete page no. [Google Scholar]

- S.A. Rosen. “History Does Not Repeat Itself: Cyclicity and Particularism in Nomad-Sedentary Relations in the Negev in the Long Term.” In Nomads, Tribes, and the State in the Ancient Near East Cross – Disciplinary Perspectives. Edited by J. Szuchman. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Oriental Institute Seminars no. 5. University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- R. Gonen. Weapons of the Ancient World. Jerusalem, Israel: Keter, 1979, (Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- J. Corbett. “The signs that bind: Identifying individuals, families and friends in hismaic inscriptions.” Arab. Archaeol. Epigra. 23 (2012): 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.C.A. Macdonald, and G.M.H. King. “Thamudic.” In The Encyclopedia of Islam. Edited by P.J. Bearman, T. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Leiden, Hollond: Brill, 2000, pp. 436–438. [Google Scholar]

- M. Halloun. “New Thamudic Inscriptions from the Negev.” In Archaeological Survey of Israel, Map of Sde Boqer – East. Edited by R. Cohen. Jerusalem, Israel: Publications of the Department of Antiquities and Museums, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- A. Negev. The Inscriptions of Wadi Haggag, Sinai. Jerusalem, Israel: Hebrew University Institute of Archaeology, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- M. Sharon. “Arabic Rock Inscriptions from the Negev.” In Archaeological Survey of Israel Ancient Rock Inscriptions Supplement to Map of Har Nafha (196) 12-01. Edited by Y. Kuris and L. Lender. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Antiquity Authority, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- A. Wosene. “Traditional husbandry practices and major health problems of camels in the Ogaden.” Nomadic Peoples 28 (1991): 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- F.V. Winnett. Safatic Inscriptions from Jordan. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- F.V. Winnett, and G.L. Harding. Inscriptions from Fifty Cairns. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- J. Corbett. “Mapping the Mute Immortals: A Location and Contextual Analysis of Thamudic E/Hismaic Inscriptions and Rock Drawings from the Wādī Hafīr of Southern Jordan.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Chicago University, Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- D. Eisenberg-Degen. “Deciphering the Camel Petroglyphs of the Negev: Har Nafha Region as a Test Case.” Master’s, Thesis, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel, 1 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- H. Gauthier-Pilters, and A.I. Dagg. The Camel Its Evolution, Ecology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- S.A. Rosen. “Desert Pastoral Nomadism in the Longue Durée. A Case Study from the Negev and the Southern Levantine Deserts.” In The Archaeology of Mobility. Edited by H. Barnard and W. Wendrick. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, 2008, pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- I. Köhler-Rollefson. “Camels and camel pastoralism in Arabia.” Biblic. Archaeol. 56 (1993): 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Stetkevych. “Name and epithet: The philology and semiotics of animal nimenclature in early arabic poetry.” J. Near East. Stud. 45 (1986): 89–124. [Google Scholar]

- S.P. Stetkevych. The Mute Immortals Speak Pre-Islamic Poetry and the Poetics of Ritual. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- G. Avni. “Early mosques in the Negev highlands: New archaeological evidence on Islamic penetration of Southern Palestine.” Bull. Am. Sch. Orient. Res. 294 (1994): 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Avni. Nomads, Farmers and Town Dwellers, Pastoralist - Sedentist Interaction in the Negev Highlands, 6th–8th Centuries CE. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Antiquities Authority, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- G. Avni. “The Invisible Conquest: The Negev in Transition between Byzantium and Islam in the Light of Archaeological Research.” In Man Near A Roman arch Studies Presented to Prof. Yoram Tsafrir. Edited by L. Di Segni, Y. Hirschfeld, J. Patrich and R. Talgam. Jerusalem, Israel: The Israel Exploration Society, 2009, (Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- D. Nahlieli. “Settlement Patterns in the Late Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods in the Negev, Israel.” In On the Fringe of Society: Archaeological and Ethnoarchaeological Perspectives on Pastoral and Agricultural Societie. Edited by B.A. Saidel and E.J. van Steen. BAR International Series 1657; Oxford, England, 2007, pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- J. Magness. The Archaeology of the Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine. Winona Lake, IN, USA: Eisenbrauns, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- S.A. Rosen. “The Decline of Desert Agriculture: A View from the Classical Period Negev.” In The Archaeology of Drylands. Edited by G. Barker and D. Gilbertson. London, UK: Routledge, 2000, pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- M. Rosen-Ayalon, A. Ben-Tor, and Y. Nevo. The Early Arab Period in the Negev. Jerusalem, Israel: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Institute of Archaeology, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- M. Sharon. “Five Arabic Inscriptions from Rehovoth and Sinai.” Isr. Explor. J. 43 (1993): 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Nevo, Z. Cohen, and D. Heftman. Ancient Arabic Inscriptions from the Negev. Midreshet Ben-Gurion, Israel: IPS Ltd., 1993. [Google Scholar]

- M. Rosen-Ayalon. “New Discoveries in Islamic Archaeology in the Holy Land.” In The Holy Land in History and Thought Papers Submitted to the International Conference on the Relations Between the Holy Land and The World Outside it, Johannesburg, 1986. Edited by M. Sharon. Leiden, Holland: E. J. Brill, 1988, pp. 257–269. [Google Scholar]

- M. Sharon. “Arabic Inscriptions from Sede Boqer.” In Archaeological Survey of Israel, Map of Sde Boqer – East. Edited by R. Cohen. Jerusalem, Israel: Publications of the Department of Antiquities and Museums, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- M. Sharon. “Arabic Inscriptions from Sded Boqer.” In Archaeological Survey of Israel Map of Sede Boqer – West (167) 12-03. Edited by R. Cohen. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Antiquity Authority, 1985, pp. 31*–34*. [Google Scholar]

- M. Haiman. “An early Islamic period farm at nahal mitnan in the early Negev highlands.” ‘Atiqot 26 (1995): 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- C. Bailey. “The Negev in the Nineteenth Century: Reconstructing history from bedouin oral traditions.” Asian Afr. Stud. 14 (1980): 35–80. [Google Scholar]

- Y.M. Israel. “The Black Gaza Ware from the Ottoman Period.” Ph.D. Thesis, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel, 5 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- A. Al-Aref. The History of Beer-Sheva and her Soundings. Translated by M. Kopliok Soshani. Tel-Aviv, Israel: Publications, 1937, (Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- T. Ashkenazie. The Bedouins, Their Origin, Life and Traditions. Jerusalem, Israel: Rubin Mass Ltd., 1957. [Google Scholar]

- C. Bailey. “Notes on the Bedouins of the Central Negev.” Notes on the Bedouins 9 (1978): 62–69, (Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- E. Marx. Bedouin of the Negev. Tel-Aviv, Israel: Reshafim, 1974, (Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- E.H. Palmer. Desert of the Exodus Journeys on Foot in the Wilderness of the Forty Years’ Wanderings. London, UK: Bell and Daldy, 1871. [Google Scholar]

- C.R. Conder. “Arab Tribe Marks (Ausam).” Palest. Explor. Fund Q. Statement 15 (1883): 178–180. [Google Scholar]

- M. Khan. Wusum the Tribal Symbols of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Education, 2000, Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- H.A. Winkler. Rock-Drawings of Southern Upper Egypt. London, UK: The Egypt Exploration Society, 1938, Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- R. Hartley, and A.N. Wolley Vasner. “Spatial Behavior and Learning in the Prehistoric Environment of the Colorado River Drainage (South-Eastern Utah), Western North America.” In The Archaeology of Rock Art. Edited by C. Chippindale and P.S.C. Taçon. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- P.J. Watson. Archaeological Ethnography in Western Iran. Tucson, AZ, USA: The University of Arizona Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- P. Demattè. “Beyond shamanism: Landscape and self-expression in the petroglyphs of inner Mongolia and Ningxia (China).” Camb. Archaeol. J. 14 (2004): 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Dayan, E. Tchernov, O. Bar-Yosef, and Y. Yom-Tov. “Animal Exploitation in Ujrat El-Mehed, a Neolithic Site in Southern Sinai.” Paléorient 12 (1986): 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Hakker-Orion. “Faunal Remains from Middle Bronze Age I Sites in the Negev Highlands.” In Ancient Settlements of the Central Negev Volume I The Chalcolithic Period, The Early Bronze Age and the Middle Bronze Age I. Edited by R. Cohen. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Antiquity Authority, 1999, pp. 327–335. [Google Scholar]

- D. Hakker-Orion. “The Faunal Remains.” In Excavations at Kadesh Barnea (Tell el-Qudeirat) 1976–1982 Volume I. Edited by R. Cohen and H. Bernick-Greenberg. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Antiquity Authority, 2007, pp. 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- S.A. Rosen, and L.K. Horwitz. “Vivat Hayil 35: A Stratified Epipaleolithic Site in the western Negev.” J. Isr. Prehist. Soc. 35 (2005): 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- E. Anati, and F. Mailland. Archaeological Survey of Har Karkom (229). Capo di ponte, Italy: Centro Internazionale di Studi Preistorici ed Etnologici, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- W.G. Oxtoby. Some Inscriptions of the Safaitic Bedouin. Ann Arbor, MI, USA: American Oriental Society, 1968. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).