Material History of Ethiopic Manuscripts: Original Repair, Damage, and Anthropogenic Impact

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

2.1. A Look at Historical Features

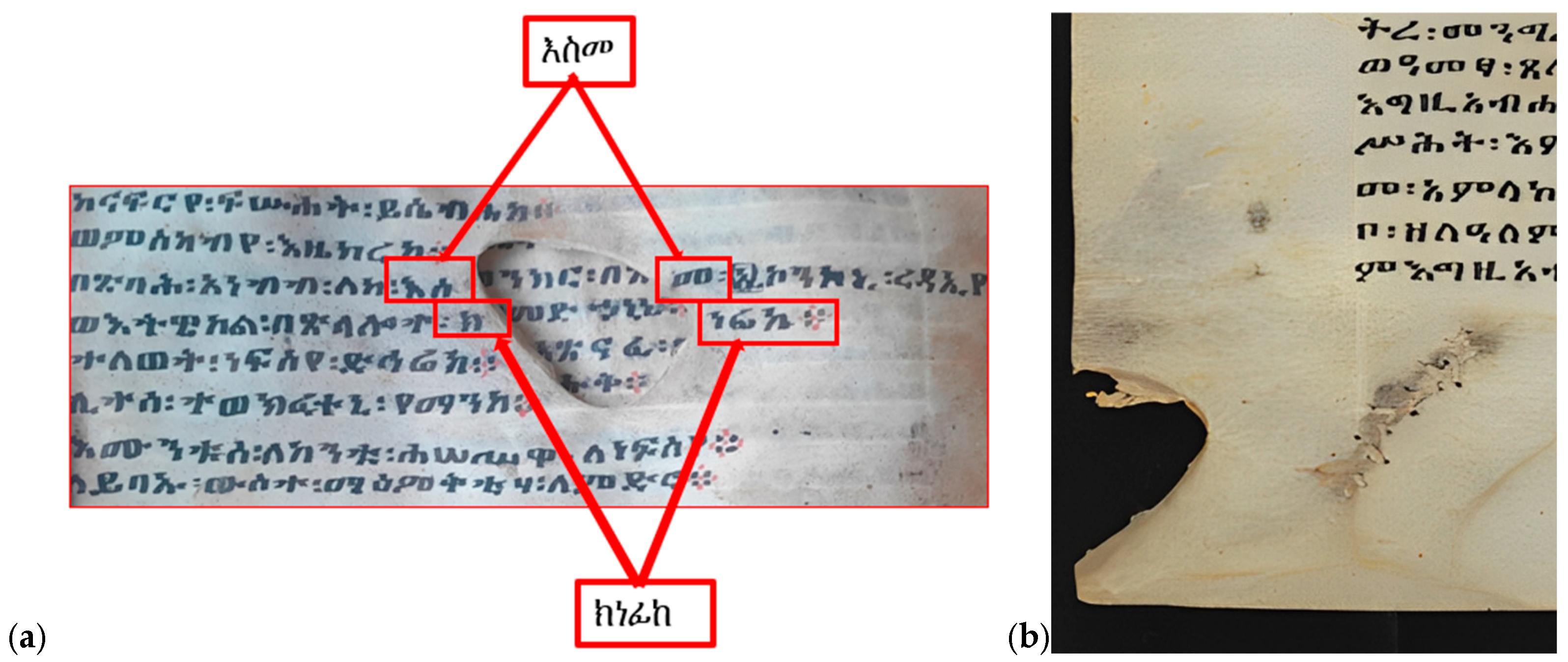

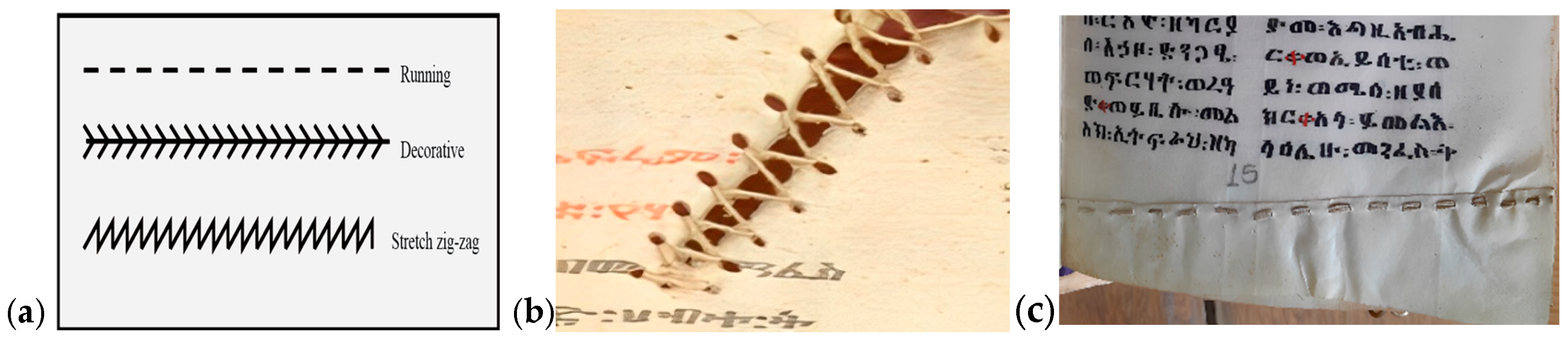

2.1.1. Evidence of Original Damage and Repairs

2.1.2. Scribes, Corrections, and Additions

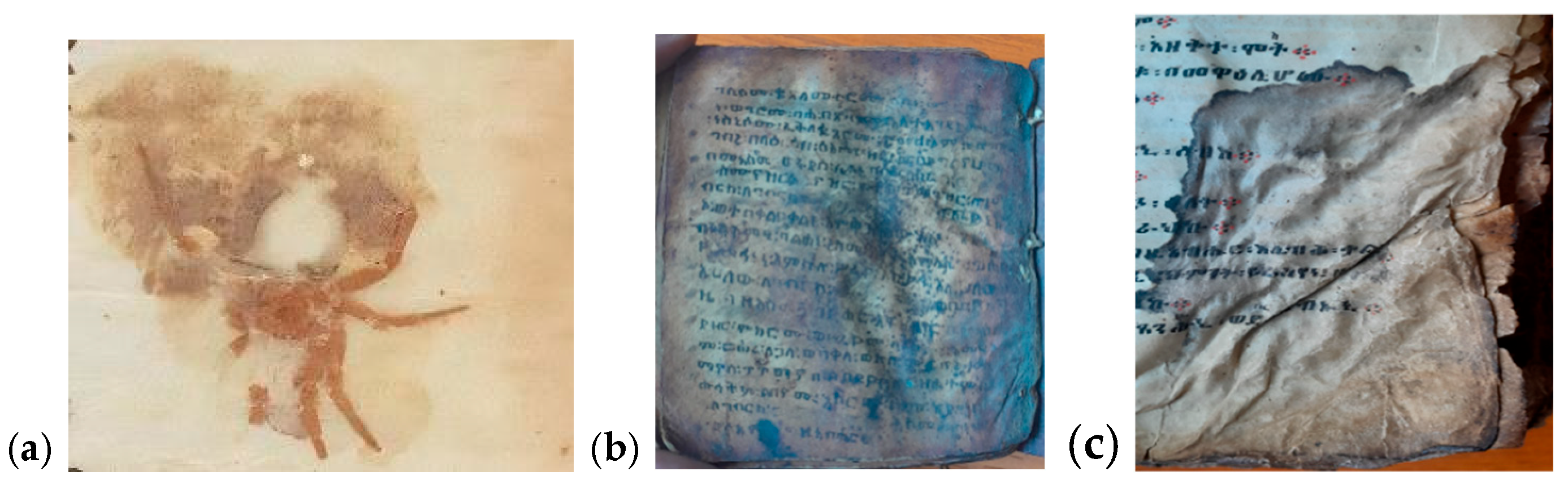

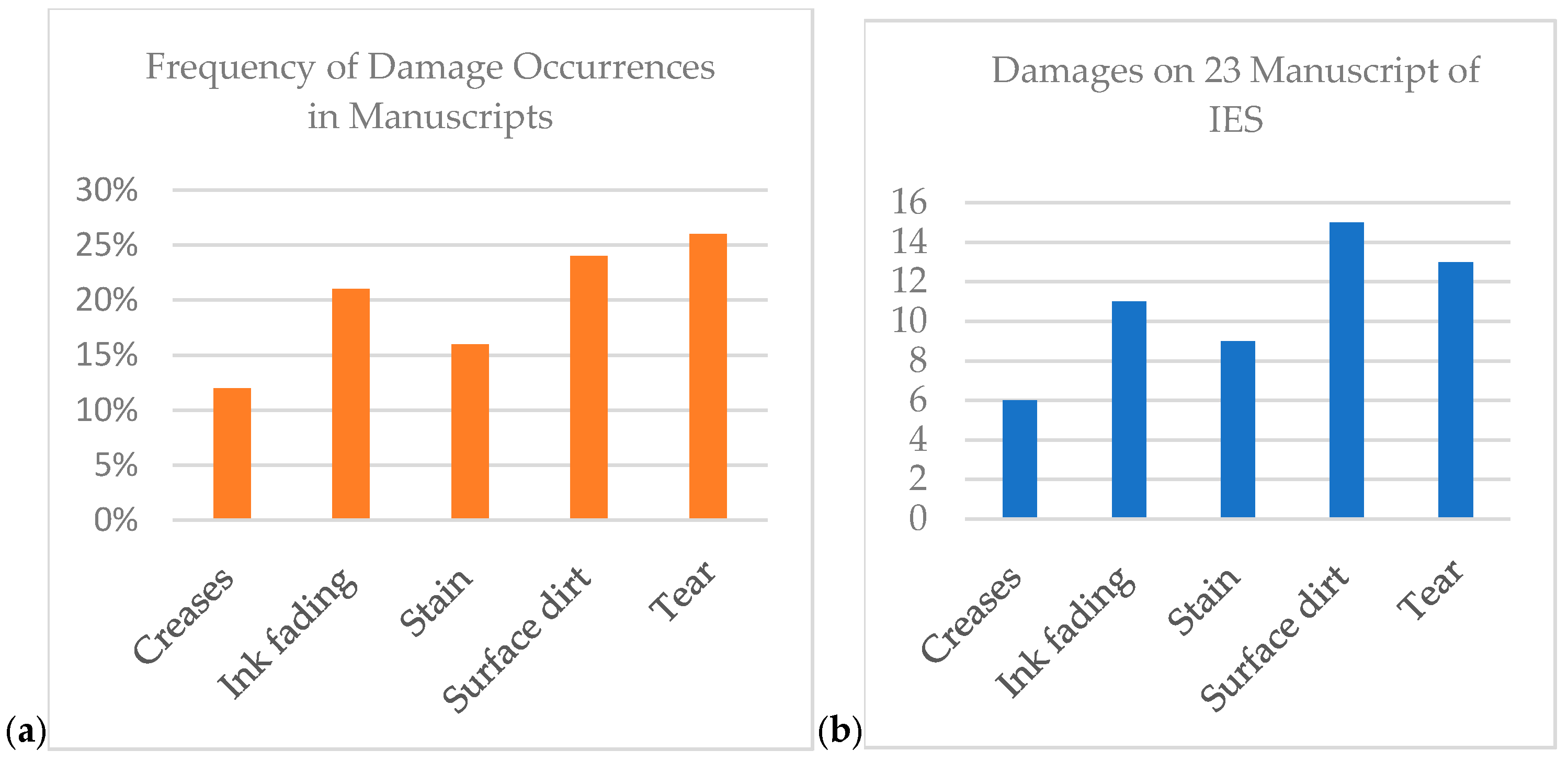

2.2. Common Deterioration

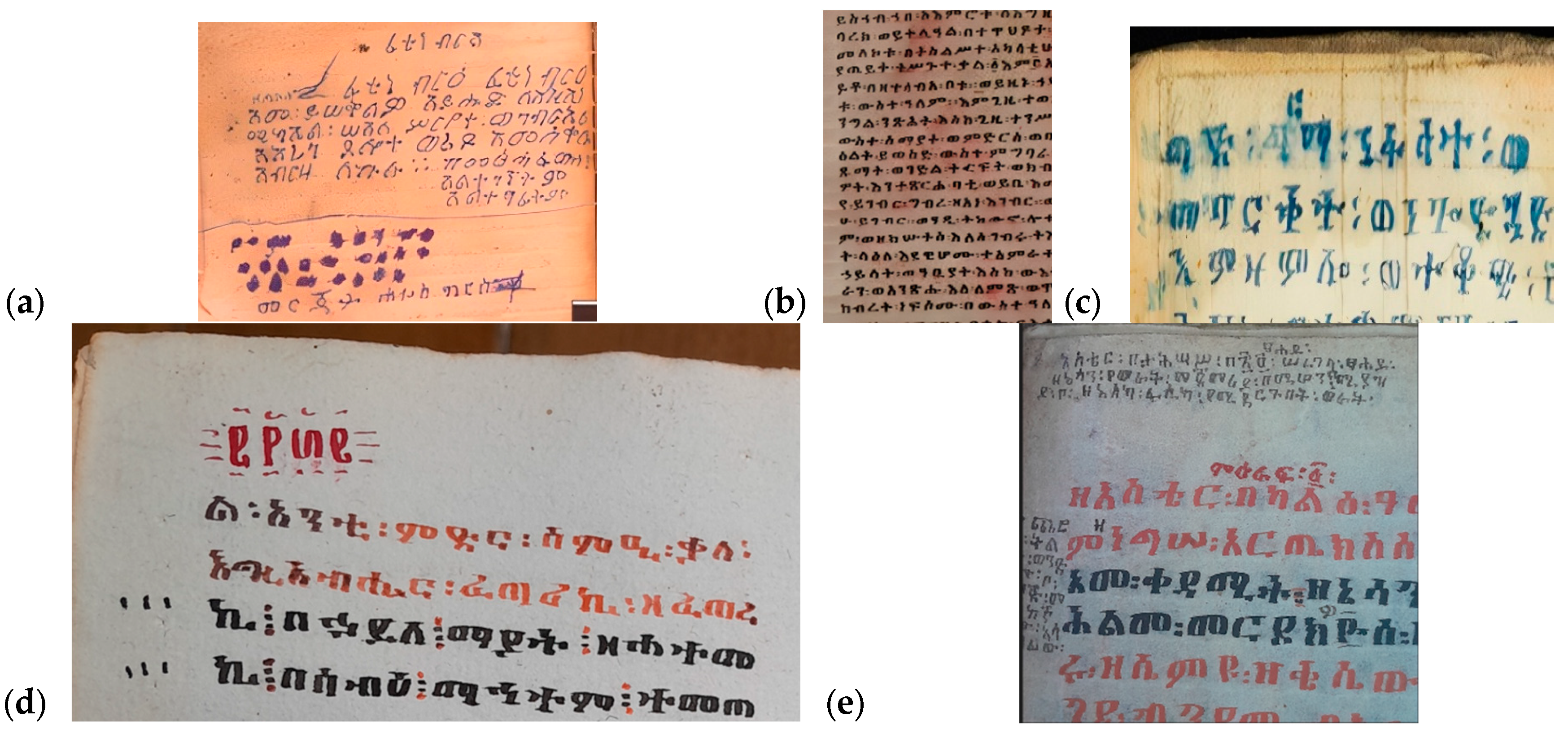

2.2.1. Surface Dirt Stains and Fading

2.2.2. Tear and Creases

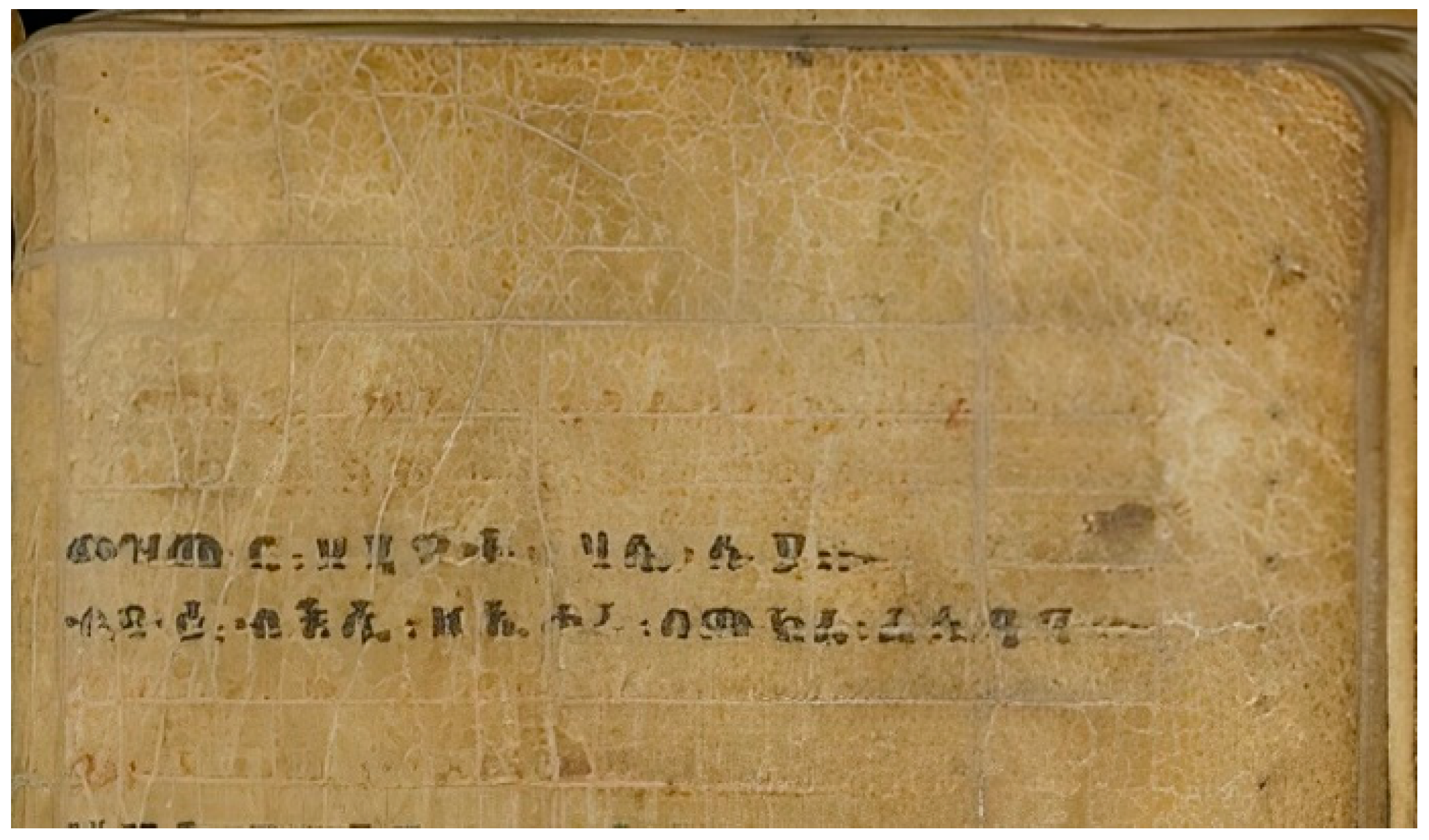

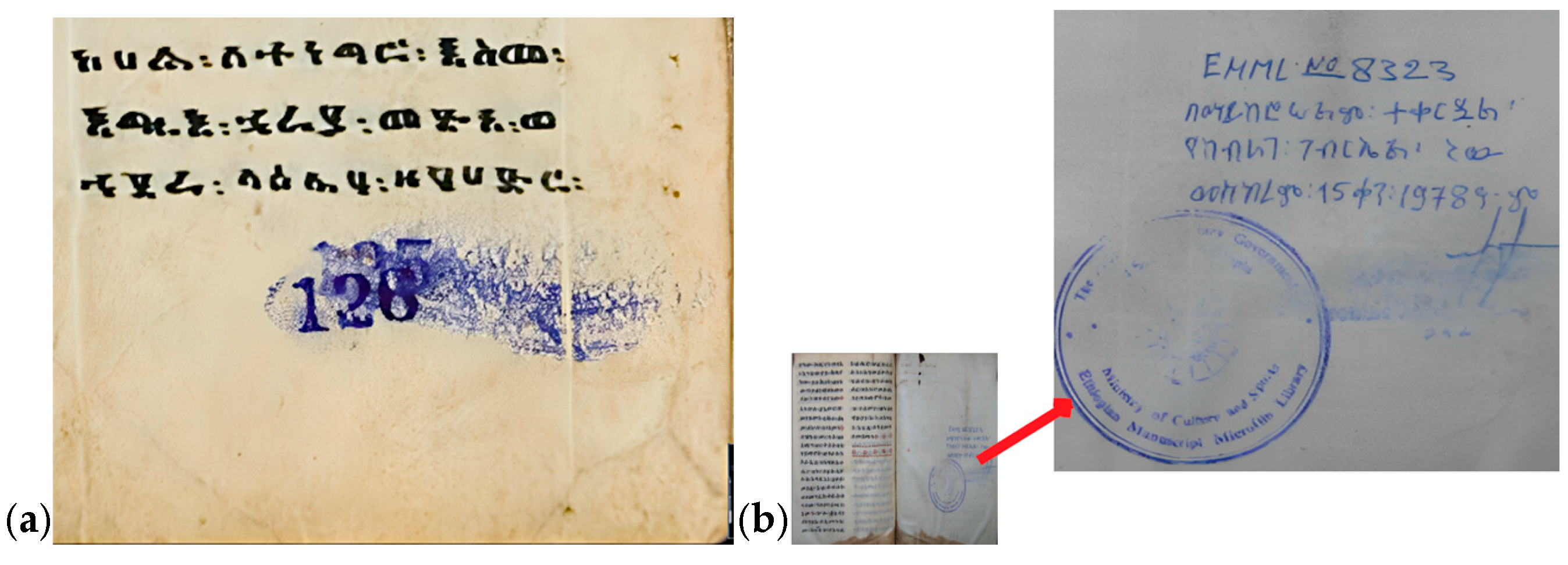

2.3. The Desecration of the Spiritual Order

2.3.1. Spiritual Order for Physical Preservation

2.3.2. Desecrated Spiritual Orders

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Maksoud, Gomaa, Hisham Emam, and Nahla Ragab. 2020. From Traditional to Laser Cleaning Techniques of Parchment Manuscripts: A Review. Advanced Research in Conservation Science 1: 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admasu, Wondwosen. 2011. A Catalogue of Some Manuscripts in Ankober Medhanialem Church Museum. Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Aikenhead, Lydia. 2020. Hol(e)y Moly!: Historical Damage and Repairs in Medieval Manuscripts. New York: The Morgan Library & Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Alemnew, Walle. 2022. Catalogue of The Manuscripts of Ṭayru Giyorgis Church, South Gondar. Master’s thesis, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Ancel, Stéphane. 2016. Travelling Books: Changes of Ownership and Location in Ethiopian Manuscript Culture. In Tracing Manuscript in Time and Space Through Paratexts, Studies in Manuscript Cultures. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 269–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalew, Hailemariam. 2009. Catalogue of Some Selected Manuscripts in Beta Mariam Church (Lalibela). Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Ayinekulu, Mulugeta. 2020. Catalogue of Hagiographical Manuscripts of Ura Kidanä Mǝḥrät Monastery. Master’s thesis, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, Blessen. 2022. Cultural Contacts between Ethiopia and Syria: The Nine Saints of the Ethiopian Tradition and Their Possible Syrian Background. In Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity in a Global Context Entanglements and Disconnections. Buckinghamshire: Brill, pp. 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Balicka-Witakowska, Ewa, Alessandro Bausi, Denis Nosnitsin, and Claire Bosc-Tiessé. 2015. Ethiopic codicology. In Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies: An Introduction. Hamburg: COMSt. [Google Scholar]

- Bausi, Alessandro, Antonella Brita, Marco di Bella, Denis Nosnitsin, Ira Rabin, and Nikolas Sarris. 2020. The Aksumite Collection or Codex Σ (Sinodos of Qǝfrǝyā, ms C3-IV-71/C3-IV-73, Ethio-SPaRe UM-039): Codicological and Palaeographical Observations. With a Note on Material Analysis of Inks. Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Bulletin 6: 127–71. [Google Scholar]

- Book of Ankritos (AM-IV-738). n.d. 19th Century. Bahir Dar: Kibran Gebriel Monastry.

- Book of Antiphonal Chants. n.d. 17th Century. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP526-1-89=436 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Book of Hawi (EMML 7603). n.d. 19th Century. Collegeville: vHMML. Available online: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/201130 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Book of Jubilees (IES MS 439). n.d. 1505. Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies.

- Brown, Julian. n.d. What is Palaeography? Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst. Available online: https://people.umass.edu/eng3/fcd/documents/Brown_WhatIsPalaeography.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Ciotti, Giovanni, and Hang Lin. 2016. Tracing Manuscripts in Time and Space Through Paratexts. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Zina, Hahn Oliver, Ira Rabin, and Aengus Ward. 2024. Centenary Paper: Of inks and scribes: The composition of a thirteenth-century Castilian manuscript—British Library Res 20787. Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 101: 703–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyril, (Add. 1569). n.d. 18th–19th Century. [Dataset]. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Digital Library. Available online: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01569 (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Dal Sasso, Eliana. 2022. Describing Ethiopian Bookbinding in TEI. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Sasso, Eliana. 2023. Ethiopian and Coptic Sewing Techniques in Comparison. In Tied and Bound: A Comparative View on Manuscript Binding. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 251–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dawit, Girma. 2019. Ge’ez Literature and Medieval Ethiopian Hagiographies in the course of Ethiopian Literature. International Journal of English Literature and Culture 7: 121–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dawit, Girma. 2023. Ethiopic Literature in Medieval Ethiopia. Journal of Liaoning Technical University 17: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Dege-Müller, Sophia. 2014. The Ethiopian Psalter: An Introduction to its Codicological Tradition. The Anglo-Ethiopian Society News File. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/9305145/The_Ethiopian_Psalter_An_Introduction_to_its_Codicological_Tradition (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- De Valk, Marijn. 2018. Library Damage Atlas: A Tool for Assessing Damage. Antwerp: Vlaamse Erfgoedbibliotheek. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, Herre. 2016. Reading the Book’s History. Understanding the Repairs and Rebindings on Islamic Manuscripts in the Vatican Library and Their Implications for Conservation. Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 7: 339–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, Marco, and Nikolas Sarris. 2021. The Conservation of a Fifteenth-Century Large Parchment Manuscript of Gädlä Sämaʿtat from the Monastery of ʿUra Mäsqäl: Further Conservation Experiences from East Tigray, Ethiopia. Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 18. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elagina, Daria. 2023. Materiality and community: Digital approaches to Ethiopic manuscript culture. In Can’t Touch This: Digital Approaches to Materiality in Cultural Heritage. London: Ubiquity Press, pp. 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fetha Nagest (EMML 7601). n.d. 18th Century. Collegeville: vHMML. Available online: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/201128 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Fetha Nagest (Or. 2122). n.d. 19th Century. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. Available online: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-OR-02122/303 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Fitsumbirhane, Desta. 2009. Catalogue of Some Selected Manuscripts of Dabra Sayon Church Ziway Island (Lulu Guddo Island. Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Four Gospels. n.d. 17th Century. [Dataset]. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP254-1-4=249 (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Genealogy of Ethiopian Kings, through King Iyasu II 1755, Petition and Supplication. n.d. Late 17th Century–Early 18th Century. [Dataset]. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP286-1-1-628=-344 (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Getachew, Haile. 1975. A Catalogue of Ethiopian Manuscripts Microfilmed for the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library, Addis Ababa, and for the Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Library, Collegeville. Collegeville: Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Library, St. John’s Abbey and University, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gezae, Haile. 2018. The Limits of Traditional Methods of Preserving Ethiopian Ge’ez Manuscripts. Libri 68: 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezae, Haile. 2024. Reclaiming and Unlocking Ancient Heritage Knowledge from Ethiopia’s Ancient Cultural Heritage. Libri 74: 349–67. [Google Scholar]

- Girmay, Marshet. 2016. Traditional Cultural Heritage Management Practice in Church Property: The case of Dakewa Kidane Meheret, Dabat Wäräda. Ethiopian Renaissance Journal of Social Sciences and the Humanities 3: 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- G/Mariam, Tamirat. 2020. Ethiopian Manuscripts and Archives: Challenges and Prospects. PJAEE 17: 4214–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gobbitt, Thom. 2014. Materiality, stratigraphy and artefact biography: Codicological features of a late-eleventh-century manuscript of the Lombard laws. Studia Neophilologica 86: 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospel Book. n.d. 18th Century. [Dataset]. Cambridge: Cambridge Digital Library. Available online: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-OR-01802 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Gospel of John (ብ.ቤ.መ 39). n.d. 19th Century. Addis Ababa: National Archives and Library Service.

- Guidi, Ignatius. 1961. Annales Iohannis I, Iyasu I, et Bakaffa. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiography of Abriham Yshaq and Yakob (IES MS 377). n.d. 14th to 15th Century. Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies.

- Hagiography of Saint Gebere Menfes Kidus (IES MS 98). n.d. 17th Century. Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies.

- Hagiography of Saints (ብ.ቤ.መ 214). n.d. 17th Century. Addis Ababa: National Archives and Library Service.

- Hagos, Abrha Abay. 2023. Manuscripts’ Digitization in Northern Ethiopia: Challenges and Heritage Crises. ECAS 2023 Conference Paper. Paper Presented at European Conference on African Studies, Cologne, Germany, May 31–June 3; Available online: https://nomadit.co.uk/conference/ecas2023/paper/73114 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Harp of Praise, Ritual for Penitential Baptism, Hymn to Mary with the Saints. n.d. 16th Century–19th Century. [Dataset]. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP286-1-1-7=277 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Haymanote Abew (EMML 8610). n.d. 18th Century. Collegeville: vHMML. Available online: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/201460 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Homily of Michael (EMML 8734). n.d. 16th Century. Collegeville: vHMML. Available online: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/201492/ (accessed on 15 June 2015).

- Homily of Mikael (ብ.ቤ.መ 226). n.d. 19th Century. Addis Ababa: National Archives and Library Service.

- Housley, Marjorie. 2015. Holes and Holiness in Medieval Manuscripts—Medieval Studies Research Blog: Meet Us at the Crossroads of Everything. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame. [Google Scholar]

- Image of Mary, Image of Jesus, Image of George. n.d. 19th Century. [Dataset]. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP286-1-1-13=271 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Job and Jeremiah (ብ.ቤ.መ 14). n.d. 19th Century. Addis Ababa: National Archives and Library Service.

- Keith, T. Knox, and Roger L. Easton, Jr. 2003. Recovery of Lost Writings on Historical Manuscripts with Ultraviolet Illumination. In IS and TS PICS Conference. New York: Society for Imaging Science & Technology, vol. 6, pp. 301–6. [Google Scholar]

- James Bible Dictionary. n.d. Available online: https://kingjamesbibledictionary.com/Dictionary/Anathema (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Krzyzanowska, Magdalena. 2015. Contemporary Scribes of Eastern Tigray (Ethiopia). Rocznik Orientalistyczny LXVIII: 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kwakkel, Erik. 2015. Decoding the material book: Cultural residue in medieval manuscripts. In The Medieval Manuscript Book: Cultural Approaches. Edited by Michael Johnston and Michael Van Dussen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Liturgy (IES MS 3164). n.d. 16th–18th Century. Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies.

- Lusini, Gianfrancesco. 2017. The stemmatic method and Ethiopian philology: General considerations and case studies. Rassegna Di Studi Etiopici 1: 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Macomber, William F. 1975a. A Catalogue of Ethiopian Manuscripts Microfilmed for the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library, Addis Ababa, and for the Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Library, Collegeville. Collegeville: Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Library, St. John’s Abbey and University, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Macomber, William F. 1975b. A Catalogue of Ethiopian Manuscripts Microfilmed for the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library, Addis Ababa, and for the Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Library, Collegeville. Collegeville: Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Library, St. John’s Abbey and University, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mazen, Bataa, Badawi Ismail, Rushdya Rabee Hassan, and Mahmoud Ali. 2021. Damage caused by black inks to the chemical properties of archaeological papyrus—Analytical study. Pigment & Resin Technology ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Mersha, Alehegn. 2011a. Medieval Ethiopian Manuscripts Contents, Challenges, and Solutions. Bulletin of the Department of Linguistics and Philology 37: 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mersha, Alehegn. 2011b. Towards a Glossary of Ethiopian Manuscript Culture and Practice. Aethiopica International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies 14: 145–62. [Google Scholar]

- Minasse, Ashenafi. 2009. A Catalogue of Some Selected Manuscripts in Abba Afase Church. Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, Sana. 2017. The visual resonances of a Harari Qur’ān: An 18th-century Ethiopian manuscript and its Indian Ocean connections. Afriques. Débats, Méthodes et Terrains d’histoire 8: 64–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nosnitsin, Danis. 2012. Ethiopian Manuscripts and Ethiopian Manuscript Studies. A brief Overview and Evaluation. Gazette Du Livre Médiéval 58: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosnitsin, Danis. 2014. Ethio-SPaRe Cultural Heritage of Christian Ethiopia: Salvation, Preservation and Research. Hamburg: Hamburg University. [Google Scholar]

- Nosnitsin, Danis. 2023a. Ethiopian Manuscript Studies Yesterday and Today. Available online: https://www.aai.uni-hamburg.de/en/ethiostudies/research/ethiospare/pdf/ppp-nosnitsin-2013-brussels.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Nosnitsin, Danis. 2023b. Lesser-known Features of the Ethiopian Codex. In Movements in Ethiopia, Ethiopia in Movement. Addis Ababa: Centre Français des Études Éthiopiennes, Tsehai Publishers, Addis Ababa University, vol. 1, pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nosnitsin, Denis, Emanuel Kindzorra, Oliver Hahn, and Ira Rabin. 2014. A “Study Manuscript” from Qäqäma (Tǝgray, Ethiopia): Attempts at Ink and Parchment Analysis. Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Newsletter 7: 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Old Testament (Add. 1570). n.d.a. 16th Century. Cambridge: Cambridge Digital Library. Available online: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk//view/MS-ADD-01570=-1570 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Old Testament (ብ.ቤ.መ 15). n.d.b. 19th Century. Addis Ababa: National Archives and Library Service.

- Panda, Siva Sankar, Neena Singh, and M. R. Singh. 2021. Development, characterization of traditional inks for restoration of ancient manuscripts, and application on various substrates to understand stability. Vibrational Spectroscopy 114: 103232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paper-Based Records. 2022, College Park: National Archives. Available online: https://www.archives.gov/preservation/holdings-maintenance/paper (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Phillipson, Laurel. 2013. Parchment Production in the First Millennium BC at Seglamen, Northern Ethiopia. African Archaeological Review 30: 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praise of Mary (Add. 1888.2). n.d. 18th Century. Cambridge: Cambridge Digital Library. Available online: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk//view/MS-ADD-01888-00002=-1890 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Praises of Mary, Gate of Light, Angels Praise Her. n.d. 19th Century. [Dataset]. EAP286/1/1/19. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP286-1-1-19=265 (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Psalter and Angels Praise Her. n.d. 19th Century. [Dataset]. EAP286/1/1/3. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP286-1-1-3=281 (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Psalter (IES MS 50). n.d. 18th Century. Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies.

- Psalter (IES MS 76). n.d. 16th Century. Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies.

- Sciacca, Christine. 2010. Stitches, Sutures, and Seams: ‘Embroidered’ Parchment Repairs in Medieval Manuscripts. In Medieval Clothing and Textiles. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, vol. 6, pp. 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sergew, Hableselassie. 1981. Book Making in Ethiopia. Leer: Karstens Brukkers B.V. [Google Scholar]

- Service Book (Add. 3682). n.d. 18th Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Library. Available online: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk//view/MS-ADD-03682/56=-65.75 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Şeşen, Yasin. 2024. Application of codicology science in Ottoman manuscripts. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi 41: 569–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, Gemma, and Hayley Webster. 2025. Getting Inked? A Survey of Current Institutional Marking Practices in Rare Books and Special Collections. RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 26: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Columba. 2017. A Brief History of the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (EMML) 2017. In Studies in Ethiopian Languages, Literature, and History. Festchrift for Getatchew Haile Presented by His Friends and Colleagues, Äthiopistische Forschungen 83. Edited by Adam Carter McCollum. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye, Samuel. 2011. A Cataloging of Some Manuscripts in Dabra Brhan Sllase Church. Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Teshager, Habtie S. 2019. Codicology of Gondärian Manuscripts (ca. 1650—1800). Ph.D. thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- The Acts of Ananya. n.d. 18th Century. Endangered Archives Programme. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP254-1-9 (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- The Book of Consolation. n.d. 17th Century. Endangered Archives Programme. London: British Library. Available online: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP254-1-40=213 (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Tomaszewski, Jacek, and Michael Gervers. 2015. Technological aspects of the monastic manuscript collection at May Wäyni, Ethiopia. In Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives Programme. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 89–133. Available online: https://books.openedition.org/obp/2228?lang=en (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Trettien, Whitney. 2024. Re-using Manuscripts in Late Medieval England: Repairing, Recycling, Sharing by Hannah Ryley (review). Manuscript Studies: A Journal of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies 9: 158–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 1970. Catalogue of Manuscripts Microfilmed by the UNESCO Mobile Microfilm Unit in Addis Ababa and Gojjam Province. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Education and Fine Arts, Department of Fine Arts and Culture. Available online: https://www.vhmml.org/readingRoom (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Vadrucci, Monia, Davide Bussolari, Massimo Chiari, Claudia De Rose, Michele Di Foggia, Anna Mazzinghi, Noemi Orazi, Carlotta L. Zanasi, and Cristina Cicero. 2023. The Ethiopian Magic Scrolls: A Combined Approach for the Characterization of Inks and Pigment Composition. Heritage 6: 1378–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vnouček, Jiří. 2022. Hole Repairs as Proof of a Specific Method of Manufacture of Late Antique Parchment. Restaurator. International Journal for the Preservation of Library and Archival Material 43: 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weronika, Liszewska, and Jacek Tomaszewski. 2016. Analysis and conservation of two Ethiopian manuscripts on parchment from the collection of the University Library in Warsaw. In Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 15. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow, Sean Michael. 2015. Ethiopian Manuscript Culture: Practice and Context. Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Wion, A Anaïs. 1999. An Analysis of 17th-century Ethiopian Pigments. In The Indigenous and the Foreign in Christian Ethiopian Art. On Portuguese-Ethiopian Contacts in the 16th–17th Centuries. Edited by Manuel João Ramos and Isabel Boavida. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 103–12. [Google Scholar]

- Worku, Belay. 2010. A Catalogue of Some Selected Manuscripts in Hayq St.: Estiphanos Abune Iyasus Mo’a Monastery. Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Yirga, Gelaw Woldeyes. 2020. Holding living bodies in graveyards: The violence of keeping Ethiopian manuscripts in Western institutions. M/C Journal 23: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonas, Yilma. n.d. Ethiopian Manuscript Heritage: Ethiopic Manuscript and the Role of ARCCH. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/28794775/Ethiopian_Manuscript_Heritage_Ethiopic_Manuscript_and_the_Role_of_ARCCH (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- ኅብረት, የሺጥላ. 2007. ትምህርተ ውግዘት. አዲስ አበባ. [Google Scholar]

- ማማሩ, ስማቸው. 2015. በምስራቅ ጎጃም ዞን የምትገኘው የከንቺ ማርያም ገዳም የእጅ ፅሁፎች መዘርዝር. [ኤ.ም.ኤ]. ባህር ዳር: ባህርዳር ዩኒቨርሲቲ. [Google Scholar]

- ሰለሞን, መሰለ. 2011. ታሪካዊ የብራና መጽሐፍት. አዲስ አበባ: የቅርስ ጥናት ጥበቃና ልማት ባለስልጣን, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- ተስፋዬ, አራጌ. 2010. ጥንታዊ የብራና መጽሐፍት ካታሎግ. አዲስ አበባ: የቅርስ ጥናት ጥበቃና ልማት ባለስልጣን, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- ዳንኤል, ክብረት. 2008. ጥንታዊ የብራና መጽሐፍት እንድ ሰነዶች ምዝገባና ማረጋገጫ ጽ/ቤት. ሐቃፊ ሀገር ካልኣይ ጉባኤ ግዕዝ ጥንቅር. አዲስ አበባ: ባህልና ቱሪዝም ምኒስቴር የቋንቋና የባህል እሴቶች ዳይሬክቶሬት. [Google Scholar]

- ዳንኤልገብረ መስቀል ቀኖ. 2019. ያልተፈታው ውግዘት. አዲስ አባባ. [Google Scholar]

- ጀማነህ, አላብሰው. 1963. የመጀመሪያው ብሔራዊ ቤተ መጽሐፍት በኢትዮጵያ. በኢትዮጵያ የፓሌ ኦንቶሎዥና አርኬኦሎዢ ጥናቶች. አዲስ አበባ: የኢትዮጵያ ንጉሰ ነገስት መንግስት የጥንታዊ ታሪካዊ ቅርሶች አስተዳደር. [Google Scholar]

- ጌታሁን, ኪዳነማርያም. 1960. ጥንታዊ የቆሎ ተማሪ. አዲስ አበባ: ትንሳኤ ማተሚያ ድርጅት. [Google Scholar]

- ጌታቸው, ኃይሌ. 2020. ከግዕዝ ስነ ፅሑፍ ጋር ብዙ አፍታ ቆይታ. አዲስ አበባ: ብራና መፅሐፍት መደብር. [Google Scholar]

- ተፈራ, ፈቃደስላሴ. 1987. የብራና መጽሐፍት ግኝትና አጠባበቅ. በኢትዮጵያ ብራና መጽሐፍት ማይክሮፊልም ድርጅት ሲምፖዚየም. አዲስ አበባ: አዲስ አበባ የኒቨርሲቲ. [Google Scholar]

- ተፈራ, ፈቃደስላሴ. 2002. ጥንታዊ የብራና መጽሐፍት አዘገጃጀት. አዲስ አበባ: አዲስ አበባ የኒቨርሲቲ ፕረስ. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Physical Location | Collection/Digital Archive | Sample Manuscripts | Period of Production | Type of Copies Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IES, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | IES collection | 23 | 16th–19th century | Physical |

| 2 | NALS, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | NALS collection | 5 | 17th–19th century | Physical |

| 3 | Gondar & Gojjam, Northwestern Ethiopia | Hill Museum & Manuscript Library | 10 | 16th–19th century | Digital |

| 4 | University of Cambridge, UK | University of Cambridge Digital Library | 7 | 16th–19th century | Digital |

| 5 | Romanat Qidus Michael & May Wayni, Northern Ethiopia | Endangered Archives Programme | 10 | 16th–18th century | Digital |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yalew, S.A.; Ortega Saez, N.; De Kock, T.; Biks, T.B.; Taye, B.; Demssie, A.S.; Dinberu, A.D. Material History of Ethiopic Manuscripts: Original Repair, Damage, and Anthropogenic Impact. Arts 2025, 14, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060173

Yalew SA, Ortega Saez N, De Kock T, Biks TB, Taye B, Demssie AS, Dinberu AD. Material History of Ethiopic Manuscripts: Original Repair, Damage, and Anthropogenic Impact. Arts. 2025; 14(6):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060173

Chicago/Turabian StyleYalew, Shimels Ayele, Natalia Ortega Saez, Tim De Kock, Tigab Bezie Biks, Blen Taye, Ayenew Sileshi Demssie, and Abebe Dires Dinberu. 2025. "Material History of Ethiopic Manuscripts: Original Repair, Damage, and Anthropogenic Impact" Arts 14, no. 6: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060173

APA StyleYalew, S. A., Ortega Saez, N., De Kock, T., Biks, T. B., Taye, B., Demssie, A. S., & Dinberu, A. D. (2025). Material History of Ethiopic Manuscripts: Original Repair, Damage, and Anthropogenic Impact. Arts, 14(6), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060173