2. Methodology

An eclectic methodology examines the ontological and affective capacities of researcher-generated photography as a critical lens for engaging with the significance of unmanaged rewilding sites, drawing on Rosa’s resonance theory and contributing to wider debates on the valorization of the countryside and constructions of “Nature.”

In

Rosa’s (

2019)

Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World, ‘resonance theory’ explores our complex relationship with landscape, the potential for ‘vertical resonance’ which the individual can achieve through a kind of transcendental experience, or metanoia. But of course, Rosa’s contribution to the consideration of “phenomenological landscapes”, and the questions that emerge, resonate in the performance, and experiential aspects of iterative photography within the Middleton Hospital site. And in terms of the longitudinal focus of the research project, might the researcher’s ‘store’ of resonance become depleted by iterative visits to the site? Is the felt experience blunted by the excessive representations (800+) of the research project? Does the methodological strategy of walking to the site with camera in hand reduce resonance, thereby commodifying the entire method of inquiry? But perhaps the self-efficacy of the researcher in these conditions is not as important as the photographs produced and related writing, to persuade the reader that the potential for a less conventional form of resonance is available through a reconceptualization of those unchecked places of rewilding. This aim echoes Rosa’s (ibid.) proposition, that resonance acts as a counter-concept to an increasingly materialistic society, disconnected from nature and each other, suffering the destructive

ennui of alienation. In this context, Rosa’s resonance theory provides a ‘relational lens’, one that eschews landscape as a static “object” and subject as passive “viewer”, with one that frames our relationship with landscape as mutual, dynamic, and transformative. Rosa reconfirms the conditions here, in which a ‘number of phenomenological studies appear to confirm that body, landscape, and weather together form a tight, involuntary system of resonance’ (

Rosa 2019, p. 385).

Belz and Wittek (

2025) reinforce the power of Rosa’s resonance theory, as a ‘meaningful, reciprocal relationship between individuals and nature, where one feels touched, transformed, and connected’ (

Belz and Wittek 2025).

Interestingly, there is no study that explicitly combines photographic representation of rewilding with Rosa’s resonance theory.

The lyrical critical reflections on the reproduced photographs (extracted from a much larger archive of the author’s 800 photographs from the site) will be informed by an eclectic synthesis, including resonance theory, social semiotics, and an expressive use of visual sociology. To explain the adoption of visual sociology it is worth noting that this approach is vital for understanding the cultural, historical socio-economic context in which sites of unchecked rewilding emerged. Combined with social semiotic analysis, visual sociology is effective in capturing the lived, sensory, and aesthetic dimensions of ecological change that text or data alone cannot convey. And although it is perhaps beyond the scope of this paper, visual sociology in the form of photographs is ideally suited to uncover social meanings embedded in the landscape, such as perceptions of wildness, beauty, neglect, or renewal, and how these might shape public support or resistance to rewilding. By integrating visual sociology, social semiotics, and lyrical reflexivity, we might better interpret how ecological transformation is both a material and cultural process.

This paper proposes that researcher-generated photographic practice provides invaluable primary epistemological evidence, while making available a conduit for interdisciplinary research collaborations/interactions. The unique potential of researcher-generated photographic practice is distilled by Pauwels:

The act of photographing and thus reframing aspects of the physical world (…) materializes the inner feelings, views, preferences, and values of the image producer and seeks to trigger similar or other reactions with the spectator (a creative process) mediated by numerous formal decisions of the image maker (…) contingent on the ability or willingness of the spectator to go further than the depicted matter or a purely denotative level of reading an image.

And irrespective of the photographer’s intentionality, it is inconceivable that some element of semiotic/sociological evidence would not result in critical reflections, associated meaning making and a contribution to knowledge. For example,

Wee and Goh (

2020) are interested in how the semiotic landscape is structured so that the specific:

indexical meanings of signs are encouraged, especially those that pertain to the display of affect. Institutional actors that have jurisdiction over a given landscape will make use of certain signs and other resources in order to encourage some kinds of affect while discouraging others.

In short, the photographic framing of rewilding in the Middleton Hospital site invites modal affordance, a semiotic process of interpretation that is capable of bestowing ideological power, expressive agency, and aesthetic socio-cultural value; and in this sense, photographic representation and the Middleton Hospital site itself is an outcome, a

mode, whose materiality has been subjected to direct physical and cultural shaping by social interaction. Interestingly, the term affordance originated in

Gibson’s (

1979) psychological research exploring cognitive perception, influencing

Van Leeuwen’s (

2005) subsequent work on ‘meaning making’ in multimodal texts. Moreover, it is worth noting the conventions in which a mode functions, including the cultural work that photographs perform ideologically in the wider historical–cultural context. The cultural shaping of the photograph as cultural artefact is interminable, always deeply affected by the unstable politics of representation, social interaction, collective memory, online/offline dissemination, and the recent questioning of authoritative archives.

Considering the ubiquity of photographs, their impact on global culture

McGuire (

1998) claims that this unprecedented image resource has created a crisis in meaning, in which an accessible image-saturated culture upholds the ‘present order’, rather than ‘redistribute cultural and experiential horizons.’ To counter this predicament, McGuire rejects the camera’s role as an ‘impassive and impotent witness’ (

McGuire 1998, pp. 58–59). McGuire’s anxiety might be assuaged by the democratization of post-digital representations produced by the public since 2000, which would include forms of activist photography and “citizen journalism”. Each of these recent practices have sought to subvert the ‘disparities of power’ often associated with the so-called “legacy media”, a situation made more complex by access to AI image-generation. As photography confronts the challenges associated with artificial intelligence

Ritchin (

2025) encourages photographers to produce personal work that explains what ‘occurred outside the frame of the photograph’, in addition to their ‘own feelings in experiencing a situation or event’. Ritchin’s “call to action” seems to support the aims of the Middleton Hospital project, in the attempt to contextualize a lyrical reflexivity embedded in the production of each photograph of rewilding.

And although the argument surrounding photography’s evidential claims may be anachronistic to many, a truncated overview (in view of the threat from AI) might be useful for the general reader: some issues still remain, in which photography can expose hidden truths, yet, others argue that the medium inevitably distorts and obfuscates a research enquiry, skewing the sociological context of ‘making, taking and reading’ rendering any worthwhile analysis untenable (

Prosser 1998, p. 99). The Middleton Hospital photographs reject this view in their non-illustrative function, demonstrating the conviction that photography not only records, but critically penetrates ‘the characteristic attributes of people, objects, and events that often elude even the most skilled wordsmiths’ (

Prosser and Schwartz 1998, p. 116).

Edwards (

1997) emphasizes photography’s ability to ‘communicate about culture, peoples’ lives, experiences and beliefs, not at the level of surface description, but as a visual metaphor, one which bridges the space between ‘the visible and the invisible’, while espousing an expressive lyricism (

Edwards 1997, p. 58). In other words, the camera provides access to social reality in the raw, in which the captured images enable us to witness not only what is manifestly present, but what is dormant beneath the edge of presence. In relation to resonance, the photographs also capture the sense of what was not there: the site’s palimpsest of transgressive interactions, including unauthorized fires, casual vandalism of the hospital’s remaining buildings, obligatory graffiti tags, and the scattered remnants of rifle shells, resulting from illegal deer hunting, are all imbricated in a tensive state of unmanaged ecological restoration, cultural memory associated with the past patients, visitors, medical staff, and the impossibility of recovering an idealized “Nature” devoid of human intervention.

In this peculiar interactive landscape context, the photographic representations of resonance are open to subsequent polysemic readings; even in this iterative longitudinal project there can never be an authoritative representation. As

Wright (

[1999] 2004) emphasizes, the captured moment can never to be repeated once secured by the camera for reproduction and repeated viewing; but the process does enable our perception to endure over time, offering reflective space to imagine, examine, interpret, in a way that would not normally be possible. In time this research archive of Middleton Hospital photographs may be valued as idiosyncratic repositories of unmanaged rewilding, offering a different experience of beauty, the pastoral, rather than dormant sites for the continuing development of rural gated communities.

Buell (

1995, p. 52) considers this reconfiguration of the pastoral concept through an ‘ecocentric repossession’, one that requires a ‘shift from representation of nature as a theatre for human events to representation in the sense of advocacy of nature as a presence for its own sake’. In certain respects, Buell’s view appears to contest Rosa’s somewhat anthropocentric view of “nature”, as an epiphanic resource/experience that is only legitimate when humans are present.

Yet the longing to return to nature persists in the antipathy toward the city and suburbia, promulgated and embedded in the pastoral notion of Arcadia, the historical region in Greece, and explored in the work of the American poet,

Gary Snyder (

1995). For Snyder ‘culture is nature’, a state in which our alienated relationship with “nature” is salvaged through an acceptance that our ‘[c]onsciousness, mind, imagination and language are fundamentally wild […] “Wild” as in wild ecosystems—richly interconnected, interdependent, and incredibly complex’ (

Snyder 1995, p. 168).

As

Williams (

1983) explains, the cultural keyword “Nature” is never a neutral timeless substratum waiting to be discovered, but a socially constructed and negotiated category deeply enmeshed in cultural practices, scientific discourses, and political power. Rather than simply referring to a pre-existing “natural world,” the idea of nature emerges through networks of human and non-human actors who co-create what counts as natural. In this view, nature is neither wholly objective nor entirely fictive—it is a hybrid formation shaped by the interplay of material processes and social meanings. Moreover, our understanding of “nature” varies across time, space, and social context; different communities, scientific traditions, and political regimes produce distinct “natures” through their practices, technologies, and narratives—a social construction that has real consequences: what is designated as “natural” shapes environmental policy, conservation, and ethical debates. As Bruno Latour observes, such ‘nature-cultures […] are co-constructed by the ‘real,’ material […] practices […] as well as by the social, textual, narrative […] practices’ (

Latour 1993, p. 6).

Furthermore, considering the post-pastoral condition

Gifford (

1999, pp. 161–62) suggests that we have access to a genuine encounter with unbridled nature which is prior to language, a process enhanced through a ‘direct sensuous apprehension’; yet, there is a catch: the semiology that we use to describe the experience is itself, socially constructed, and the dream of Arcadia always remains a ‘literary construct’. While acknowledging the often-cited “limitations of language” in response to lived experience, we must still persevere.

To lubricate the reflections on the experience of resonance in the Middleton Hospital site and its photographic re-presentation, one finds linguistic support (and solace) in the work of

Abbott (

2007), the principal theorist of lyrical sociology.

Abbott (

2007, p. 74) asserts that an enduring lyrical reflection is manifest from the perspective of ‘an intense participation in the object studied’. In this spirit, my own truncated semiotic reflections are written from a stance that is emotionally engaged and sensitive to a particular consciousness situated in a specific place over time. Importantly, the main difference between a lyrical and narrative account includes the following: a narrative writer tells us what happened and perhaps to explain it. The lyrical writer aims to tell us of their intense reaction to the social process encountered. This means that the first will tell us about sequences of events while the second will give us congeries of images. Adopting the

Rosa (

2019) position, the lyricist will use figurative language and personification (

Abbott 2007).

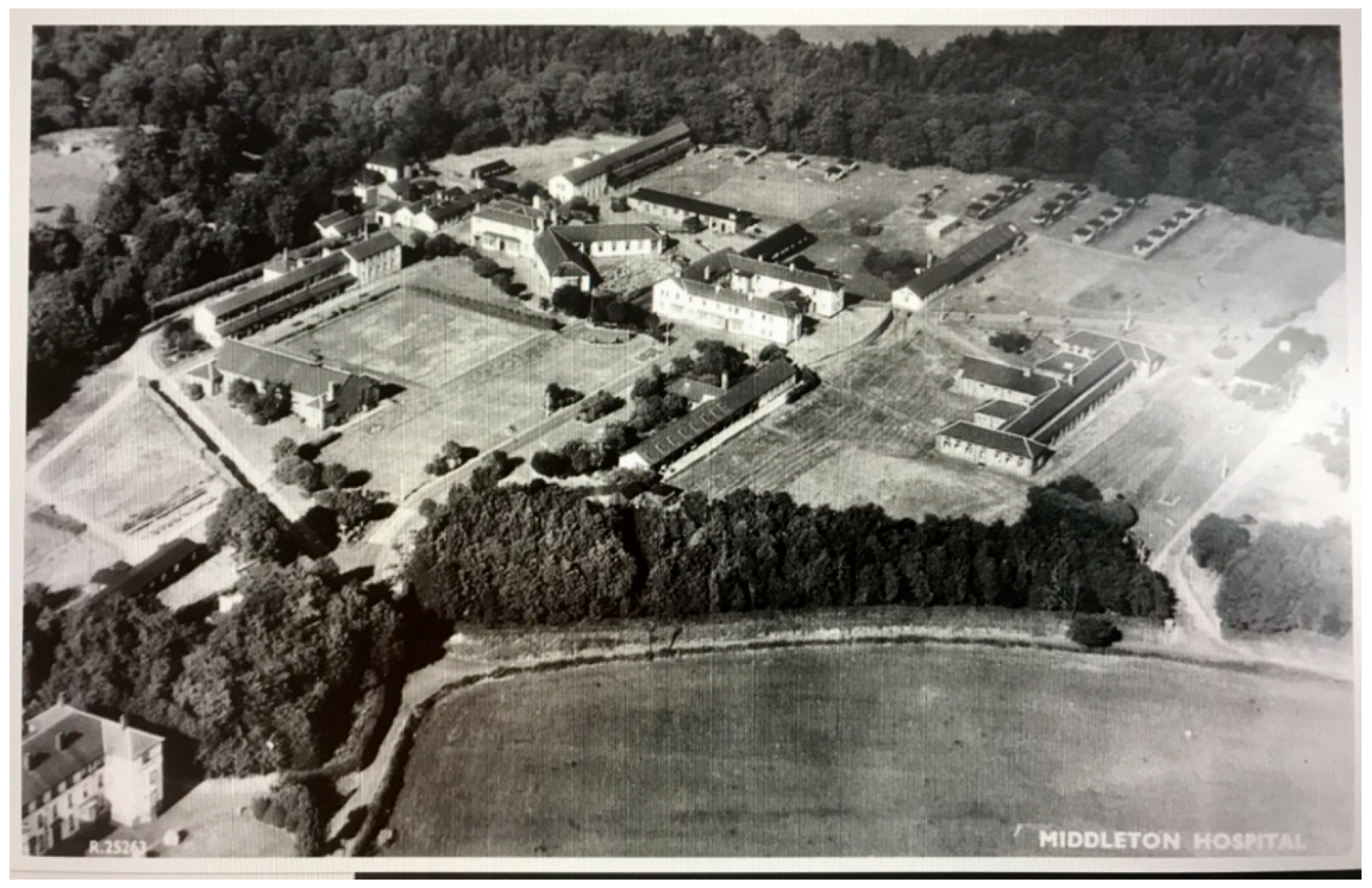

Incorporating the lyrical intensity of the ‘return’, longitudinal rephotography enables the recording the seasonal transformations, charting the encroachment of rewilding which increasingly shrouds Middleton Hospital’s historical function. Rephotography has been used by various activist photographers to expose evidence of environmental damage, argue for protection, and regulation. Consider Desert Cantos (1979–) by Richard Misrach, an ongoing project to record the contamination of the southwest American desert landscape.

In short, the rephotography research method enhances the continuing dialogue that situates photography’s capacity to bear witness into practice. (

Mc Leod et al. 2014).

In many ways, the photographs of the Middleton Hospital site resonate with other overlooked urban landscapes, in which ownership and function remain ambiguous, resembling counter spaces—a

terrain vague. According to

Barron (

2014, pp. 1–23) such interstitial places are ‘containers of a fragmented shared history, illuminating the imperfect process of memory that constantly attempts to recall and reconstruct the past’.

Although an obvious point, walking as a form of active research was essential to the production of the project. The slow act of walking facilitated photographic observations, mitigating expedient choices, concomitantly promoting the experience of resonance, while facilitating reflexivity. Furthermore, the immediacy, and slightly subversive action of walking has always been deeply embedded in visual sociology practice and the wider performative aspects of social semiotics in which the photographer’s presence is a contributory factor.

According to

Van Leeuwen (

2005), semiotic resources are most potent when considered as the connection between representations and how people implement them, in which semiotic ‘resources are the actions, materials and artefacts we use for communicative purposes’, their meaning making potential augmented by their ‘past uses, and a set of affordances based on their possible uses’ (

Van Leeuwen 2005, p. 285). In many ways, the countryside has been absent from much social semiotic discourse. I discussed this apparent gap in the social semiotic literature with

Van Leeuwen (

2005). In one exchange, Leeuwen responds to my enquiry on potential use of social semiotics in relation to landscape research: ‘(…) I would approach landscapes in relation to the social practices in which they play a role. Even if landscapes that are not produced by human effort, (they) still exist for us only when they function as the sites of social practices’ (24/01/22).

In considering the recent replacement of the critical term ‘mood’, to

atmosphere (possessing a similarly elusive feeling to resonance),

Anderson (

2009, pp. 77–81) suggests a ‘series of opposites—presence and absence, materiality and ideality, definite and indefinite, singularity and generality—in relation to tension’ should be present. For my part, iterative researcher—generated photography emplaced in the rural landscape is able to fulfill Anderson’s recommendations.

3. Critical Reflections on the Middleton Hospital Photographs 2016–2025

In the same way that landscape, and the theorization of “nature” is an ideological socio-cultural construct, the photograph as artefact (visual text) has the potential to elicit ideological socio-cultural reactions, while being subjected to the same forces that try to determine its ontological embodiment. In short, both the landscape and the photograph invite different readings and cultural inscriptions. In this complex context, how do photographs capture the resonance lurking in the rewilded landscape? How might framing affect interpretation(s)? According to

Ravelli and McMurtrie (

2016, p. 107), ‘information values’ and ‘organizational meanings’ are affected by the ‘degree of framing between different parts of the spatial text’, which contribute to the connection or separation between visual elements. Evident in the photographs reproduced here, are multiple semiotic resources that affect the dialogic encounter. In formal terms, we must consider a fundamental question: does the choice of landscape or portrait format affect the readers’ interpretation(s)? In terms of representing resonance and the iconography of rewilding is the expansive scanning opportunities afforded by adopting a landscape format view more effective in creating a meaningful discourse around landscape valorization. A human’s lateral head movement when encountering a new place suggests that this is an innate surveying choice inherited from ancestors.

In contrast, the portrait format demands that the viewer must raise their head to scan the visual information. This upward motion is also related to the concept of salience in social semiotics, implying subordination, and hierarchy. As an example of this effect, consider the somatic impact of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel (1508–1512) on the visitor. Moreover, a significant cultural signifier emerges through salience by initiating a ‘reading path’, in which the spectator’s vision moves between ‘points of fixation, accruing information in order to construct an overall visual interpretation’ (

Ravelli and McMurtrie 2016, p. 108).

The entire Middleton Hospital archive of photographs adopts the landscape format framing, to encourage the reader to scan from left to right, a strategy essential to the semiotic configuration of each photograph; this is not to say that important imagery is always situated on the right side, but the intention is to create semiotic ‘jolts’, often incorporating a Western semiotic regime, without foreclosing alternative interpretations.

A truncated selection of seven researcher-generated photographs is reproduced here from the larger archive of over 800+. The intention is to show the gradual rewilding of the site through distinctive seasonal changes, some of which, reveal the bizarre collisions caused by quixotic human agency; such performances have contributed to the site’s unexpected resonance.

A definitive interpretation of each photograph is eschewed, to invite the readers’ alternative readings. The lyrical style of semiotic interpretation aims to reflect the complex situatedness of the researcher–photographer as a present subject, experiencing potential resonance, while immersed in the site, equally affected by the contrasting changes due to times of the day and seasonal weather transitions. In this sense, the photographer’s embodied presence in the site becomes a methodological asset. According to

Rosa (

2019), resonance is more likely to happen when the subject (me) allows the world to affect them, creating a space where knowledge is generated through reciprocal engagement rather than a detached observation, often associated with ‘objective’ documentary photography. Therefore, the photographs produced during such encounters serve as material traces of this resonant relation, capturing the co-presence of empirical witnessing and affective experience.

Nevertheless, one recognizes that the key semiotic resource—the photographic frame, is already contaminated (to varying degrees) by the autobiographical subjective life of the researcher–photographer’s social practice, whose neutral aspiration for a ‘complete reality’ remains partial and open to subsequent interpretations. To mitigate an overly subjective approach to the research project, it was essential to extricate oneself from the seductive atmosphere of the site through reflexivity, an attempt to counter this critical predicament, by anticipating the potential readings that might be elicited by the photographs. And while avoiding self-censorship, one must be sensitive to how each photograph might be interpreted in other contexts, such as exhibition venues, traditional art galleries, digital or analogue print reproductions, offline or online, and of course, which audiences have access to the photographs and ideas underpinning their development and dissemination.

Embracing the multimodal interdisciplinary potential of photography,

Kress and van Leeuwen (

2001, p. 2) encourage scholars to:

move away from the idea that the different modes in multimodal texts have strictly bounded and framed specialist tasks (…) Instead we move towards a view of multimodality in which common semiotic principles operate in and across different modes

This wider reflexivity should inform the ‘modes of representation’, and the ‘consequences for eliciting different meanings’ by different political, local and academic discourses, resisting generic visual representations which fail to question culture for fear of adverse reactions (

Pink 2007, p. 43).

The anchoring of unambiguous meaning in relation to photographs is tempered by what

Wright (

[1999] 2004, p. 6) claims: is a relationship to reality constructed through ‘cultural convention’, in which people have been ‘taught to see [photographs] as such’.

According to

Mauad et al. (

2004, p. 185) ‘the very act of taking pictures also anticipates what is worth being shown’. As polysemous surface artefacts photographs expose multiple potential narratives, meanings (some latent), uncertainties, provocations, and ambiguities, all of which, invigorate the lyrical reflections on resonance in relation to rewilding.

Although other visual researchers have not underpinned their research on rewilding within resonance theory, there are two important photographers whose longitudinal projects ‘speak’ to the Middleton Hospital project, they are Wout Berger, and Joel Sternfeld. Sternfeld’s celebrated project

Walking the Highline (2000) recorded Manhattan’s derelict elevated rail in wide format colour photographs to explore a forgotten urban ecology resistant (temporarily) to the surge of New York gentrification.

Brogden (

2019) points out the paradox of certain visual representations, that: ‘In this bizarre urban ecology, the creative sector is itself implicated in the destruction of the distinctive places that attracted them [researchers, photographers] in the first place’ (2019, p. 147).

In contrast, Wout Berger’s

Giflandschap (

Poisoned Landscape,

Berger and Sijmons 1992) Dutch project documents inadvertent areas of rewilding because of toxic contamination and social neglect. In an interesting postscript to Berger’s project in 1992, he returned to the same toxic sites in

Giflandschap Revisited (

Berger 2017) to discover how soil remediation over the past 25 years had reshaped or decontaminated the sites. According to the soil scientists who provided scientific commentaries to Berger’s photographs, many formerly polluted sites showed significant improvement through decontamination, although the beauty of rewilding transformation still hides the complex toxic legacies.

In this context, both Sternfeld and Berger have been instrumental in combining visual research rigor and aesthetic ambiguity, resulting in compelling strategies prompting urgent policy debate, and the public’s engagement in rewilding.

Despite the unremarkable landscape depicted in the photograph

October, Middleton Hospital (2016) the allusion to the history of landscape representation is clear: namely the

en plein air tradition of outdoor easel painting, contributing to the notions attached to the ‘prospect’, the surveying landscape gaze as projection, a form of possession inviting the spectator to ‘own’ what is encountered and reimagine (

Figure 2). The subjugated wild “nature” evidenced in the landscape designs of Capability Brown (1716–1783) are subverted in this celebration of heterogeneity, complete with the subtle evidence of transgressive human agency signified in the “chance juxtaposition” of discarded rubble. We are reminded of other ‘grim’ northern edgelands, celebrated in films like

Kes (1969), directed by Ken Loach (1936–). Indexically, the mid-foreground shows evidence of the first ‘pioneer’ of rewilding: moss.

Such reflections recall Walter Benjamin’s fascination with photography’s “optical unconscious”, a phenomenon in which the visual content of ‘photographs reclaim from the unconscious domain, for the re-engaged conscious mind to consider’ (Benjamin cited by

Brogden 2019, p. 116). The opportunity to reconsider the photograph (

après coup) beyond the research field is crucial for semiotic analysis and meaningful reflexivity.

The planar axis frontality of the photograph

May, Middleton Hospital (2018) functions as the

leitmotiv of the project, represented by the juxtaposition of spreading birch trees across the remnants of a previous building’s concrete foundation (

Figure 3). The photograph arrests the dichotomous archaeological ‘destination’ of the scene, in which compressed building materials will eventually return to their original earthly materiality.

Without foreclosing other readings (and perhaps digressing), one recalls the discoveries of Nazi atrocities in similar arboreal locations throughout central Europe, where nature was complicit in interring evidence.

Baer (

2005) asserts in his book,

Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma how seemingly inconsequential landscapes can hide sites of trauma, where the ‘presence of trees are evidence not of death and destruction but of the denial and concealment of its occurrence’ (

Baer 2005, p. 78). Moreover, the phrenic detonation of certain places is explored by

Lock (

2015, pp. 113–30) where a subject’s relation with place itself is never simply physical, sensuous or spatial, but also typically psychic in character’.

Continuing this reflection on the deliberate (or accidental) repurposing of landscape resulting in a disquieting form of resonance, similar residual features inhabit the Middleton Hospital site, suggesting ancient earthworks.

During previous site excavations conducted by the environmental agency, to check the site for toxic materials, such as asbestos and radioactive contamination caused by discarded X-rays, these investigations have created several unintentional ‘land art’ mounds, providing various plants with an opportunity to access greater light (

Figure 4). It is not surprising then, that the decision to take the photograph

April, Middleton Hospital (2022) is influenced by the creative interventionist land works of Robert Smithson, in which his American landscape reconfigurations include,

Partially Buried Woodshed, Kent State, Ohio (1970). This piece provides an early example of Smithson’s fascination with the angle of repose—the inevitable degree that mounds adopt, according to the laws of physics. Smithson’s repurposing of redundant industrial sites is particularly relevant to the Middleton Hospital site, across which rewilding is prosecuting a similar imbrication. As

Graziani (

2004, p. 168) asserts, Smithson was interested in the ‘idea of using abandoned quarries, old strip mines and the recycling of ‘ruined landscapes’ that afforded a surprising ‘cultivation’.

The paintings of English artist, Paul Nash (1889–1946) influenced the photographic research in the way he highlighted a specific landscape motif in his work, often drawing on the remnants of ancient and sacred sites. Nash’s landscape paintings represent his inner vision and, in some ways, prefigure

Rosa’s (

2019) argument for spiritual renewal in nature. Like the Middleton Hospital site photographs Nash sought places that eschewed conventional beauty, in favor of the uncanny and ritualistic. A painting that epitomizes Nash’s visual sensibility is

Wittenham Clump (1913), noted by Nash, as the ‘Pyramids of my small world’ (

Moore 2007, p. 146). (One notes that Nash’s approach to landscape is indebted to the sublime work of the English artist, Samuel Palmer (1805–1881).).

In contrast to the more intimate landscape encounters depicted in the paintings of Nash, the work of the German Romantic painter, Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) anticipates the contemporary desire for more immersive encounters in wild landscapes. One imagines Friedrich finding solace, and indeed, resonance in the Middleton Hospital site, attracted by its imbroglio of ruined hospital remnants and an encroaching unfettered nature. One might consider that Friedrich’s paintings featuring the recurrent

Rückenfigur—the solitary figure viewed from behind—operates as a mediating device that invites the viewer to inhabit the perceptual and emotional orientation of the depicted subject. The painting

The Monk by the Sea (1809) encapsulates Friedrich’s prescient vision of resonance through the figure’s solitary encounter with nature’s ineffable elements. As

Hofmann (

2000) suggests:

The [Prussian Crown] Prince many have been fascinated by the sombre atmosphere of the [painting], which contained neither comfort nor patriotic uplift. They offered him a refuge from current events, precisely because their tone of anchorite isolation was so remote from the world of war and politics.

Rather than functioning as individualized characters, Friedrich’s figures function as proxy observers, whose posture, scale, and placement within the landscape establish a contemplative mode of viewing. To “identify” with them, therefore, is not merely to project personal feelings onto the scene, but to recognize how the pictorial structure actively positions the viewer within a shared horizon of experience. And in relation to resonance theory this identification reflects an interpretive process in which the viewer adopts the embodied stance offered by the painting’s atmosphere of introspection, sublimity, existential reflection, and experience of resonance. And like Friedrich’s Rückenfigur, the researcher–photographer, both present but absent, becomes a conduit through which the viewer negotiates their own relationship to the landscape site, aligning subjective affect with the visual and spiritual orientation that Friedrich stages. In this sense, identification emerges as a co-produced experience: a dialogue between the viewer’s inner life and the representational strategies that guide their empathetic entry into the image.

In the photograph

January, Middleton Hospital (2023) the framing of this ‘beaver lodge’ of heaped branches suggests human agency (

Figure 5). The modal affordance created by the reconstituted arboreal material might point to the conservation of insects, toads, newts, bees, and hedgehogs, while alluding art historically, to the ephemeral outdoor constructions created by the English artist, Andy Goldsworthy (1956–). The overall resonance of the photograph pays homage to the painting

Hunters in the Snow (Winter) 1665, by Pieter Breugel (1526–1569). The frame’s indexicality entices the viewer to consider other allusions to other landscape representations—a factor emphasized by

Kress (

2010):

the word ‘frame’ names the formal; semiotic resources which separate one semiotic entity from its environment ‘pre-frame’ or from other semiotic entities. In this, the frame provides unity, relation and coherence to what is framed, for all elements inside the frame. Without a frame we cannot know what to put together with what, what to read in relation to what. If we do not know what entities there are, we cannot establish relations between them. We cannot know therefore where the boundaries to interpretation are: we cannot make meaning.

And importantly, what is excluded from the frame is equally important, and what might continue and change in the site of the original event. This is crucial in considering the site’s continued transformation through rewilding and quixotic human interventions. As

Wright (

[1999] 2004) reminds us, the photographer must anticipate the transformations in the subject, the future contexts inhabited by the photograph, and how subsequent viewers might form interpretations:

Photographs suggest meaning, partly in the ways that they are structured themselves, and arts of the image can set off trains of thought which have as one of their objectives that of stimulating the viewer’s imagination.

According to

Lee (

1997, pp. 126–41) there is no such thing as a neutral site, rather a place ‘upon which the effects of prior social relations produce a complex array’ of meanings. As

Lee (

1997) asserts, places (such as the Middleton Hospital site) are often subjected to a superficial scrutiny, viewed as a potential real estate development, mere backdrops to social change, yet there are possibilities to reflect on:

human agency and space: that is, the relationships between people (defined by their class position, gender, age, racial or ethnic origin, and so on) and their geographic environments, how they use or are used by these environments, how notions of ‘identity’, ‘belongingness’ or ‘alienation’, for example, are forged through these environments.

John Gossage’s prescient Photobook,

The Pond (

Gossage [1985] 2010) presents similar complexities in relation to the valorization of certain places. His series of monochrome photographs seek to reveal the tensions that exist between a liminal wild area, and an encroaching suburbia, signified by the random detritus left by transgressive human agency. Gossage’s Photo book pays a literary homage to Henry David Thoreau’s

Walden (

Thoreau 1854), itself a proto- ecological meditation on the value of solitariness in wild nature (resonance), in relation to an increasingly materialistic America, inhabits the Middleton Hospital site project.

4. A Different Kind of Beauty

As we have discussed, to frame a subject transforms its visual information and meaning-making potential. In relation to representations of rewilding and their cultural reception, one must be aware that even the most abject subjects captured, including photographs of war and other traumatic events, are likely to fall ‘victim’ to the process of aestheticization—re-presentation. Therefore, any attempt to critique the term beauty, is a precarious venture, liable to flounder, so, I approach it with due caution.

Various contestations emerge when aesthetic comparisons and judgements are offered between archetypal agricultural landscapes, collectively recognized as the ‘countryside’, and those landscapes associated with rewilding. This aesthetic landscape paradigm is deeply embedded in English culture, a condition supported by the ideological power exerted by organizations like the National Trust, although a new generation of members are influencing the Trust’s consideration of alternative sites for protection. Let us consider what I refer to as the “plaque effect”: a process that designates cultural value on nature and landscapes (

Brogden 2019, p. 101). Imagine the reception if the Middleton Hospital site was installed with its own ‘National Trust’ branded plaque declaring the “Middleton Hospital Arboretum”.

Nevertheless, each landscape is managed to a lesser or greater degree, affecting the aesthetics of place, and of course, the potential for individual resonance. The management of treasured National Trust sites is explicit, deploying information guides, designated walking routes, car parks, souvenir shops and café, all of which requires obvious governance, while the Middleton Hospital site’s management is enigmatic, often transgressive, reliant perhaps, on a deliberate collective forgetting (save for the odd adventurous psychogeography YouTuber), until the next development application to the North Yorkshire Planning Department ignites some interest, in the form of objection letters from interested parties.

This aesthetic predicament is reflected in the photographs:

October, Middleton Hospital 2019 (

Figure 6) and

December, Middleton Hospital 2024 (

Figure 7). Both, I would argue, invest the site with cultural references to the Sublime and

Rosa’s (

2019) resonance theory in relation to landscape and place: photography’s unique ability to arrest fleeting autumnal and winter light. The promise of a sensuous encounter, deeply connected in nature (not separate) inhabits both photographs. We encounter in (

Figure 6) a proximity to the brittle golden autumnal leaves of densely situated saplings, to the

contre-jour shadows (

Figure 7) cast by an early hoar frost. We can almost hear and feel the sharp crush of the photographer’s boots when setting up the camera.

Abram’s (

1997) echoes a similar experience of resonance in proselytizing for encounters in an overlooked nature, reiterating, that without these sensory experiences, and apprehension, there could be nothing:

to question or to know’ [where] the living body is thus the very possibility of contact, not just with others but with oneself—the very possibility of reflection, of thought, of knowledge.

The bucolic iconography might even invite the reader to reflect on the original function of these hospital grounds: the treatment and offer of solace to those suffering from tuberculosis. The countryside is perceived as a sanctuary—“a breathing space”.

This sense of bucolic retreat from an unhealthy urban milieu is epitomized in the final photograph,

June, Middleton Hospital (2025) (

Figure 8). The anthropomorphic teasles (used in the northern textile mills to catch stray fibers) offer a sanguine reclamation of this (to certain people) everyday “wasteland”, with its paradoxical beauty, a photograph that fails to represent the equally important soundscape of this immersive experience, including the murmur of insects, and frequent birdsong.

Now a successful clinical psychologist in Australia, having moved on from a flourishing academic career in philosophy,

Kieran (

2007, p. 5) reflects on the photographic aestheticization of everyday places like the Middleton Hospital site, in which ‘the beauty of the photographic prints’ (unlike the Pre-Raphaelites idealized depiction of the English countryside), presents a different beauty, one that emerges ‘from that which many of us would not normally appreciate in real life’. Kieran (ibid.) encourages an engagement with the unseen value of these overlooked places, whose re-presentation offers a new apprehension of the transcendental in the everyday. How is it that the photographs reproduced here are beautiful, whilst (or so it may seem to us), what is depicted is not?

Kant (

[1790] 2007) recognized that even where the subject matter itself is unappealing, it can nonetheless be depicted beautifully.

A re-engagement with the historical motif of the ruined landscape transformed by rampant rewilding is evident in the work of two artists who have influenced the choice of the Middleton Hospital site: Robert Polidori conducted the ultimate rewilding investigation (however inadvertent) in his book

Zones of Exclusion: Pripyat and Chernobyl, (

Polidori and Culbert 2003), which provides a powerful testament to the restorative power of nature, a process made more compelling, when we understand the circumstances that created this new ‘wilderness’, emerging as it did, from the Chernobyl radioactive contamination incident, on 26 April 1986.

Like Polidori, the English artist

Jarman (

1995) sought to represent a paradoxical Arcadia (made more elegiac by his HIV condition at the time) with the ‘dark side’ of a contested landscape. Jarman’s film,

The Garden (1990), made two years before his death, distils his life-long preoccupation with beauty, transience, decay, and nature’s resurgence. The redemptive Prospect Cottage Garden, which Jarman created on the unforgiving English shingle ‘desert’ at Dungeness (adjacent to the nuclear power station), is testament to an unconventional apprehension of nature, and beauty in unexpected places.

5. Findings and Conclusions

The intention was to use researcher-generated longitudinal photographs to present a cultural defense for rewilding, revealing “nature’s” own ineluctable restoration (without deliberate human intervention) using the case study of the redundant Middleton Hospital site. And in the broader context of landscape re-presentation and its cultural valorization, the paper also explored the potential to experience Rosa’s theory of resonance in these less codified places, often prohibited by ambiguous ownership, while seemingly resistant to conventional forms of recreational landscapes visited by tourists.

And although the inclusion of a more detailed analysis of the surrounding ‘peribolos’ of the agricultural landscape in the Middleton area is beyond this paper, its pervasive presence accentuates the tenuous coexistence that afflicts sites of inadvertent rewilding—an ecological situation that might be reevaluated by the wider society (

Sessions and Devall 1985;

Harvey 1998;

Naess 1989).

The paper demonstrated a robust aesthetic and critical defense of primary researcher-generated photographic practice, itself, a method in need of cherishing, protection, from the challenges represented by AI image generation. As a heuristic tool with its own complex history, photography has been proselytized here as an epistemological conduit through which the iterative representation of the Middleton Hospital site could elicit a range of interdisciplinary approaches, including social semiotics, visual sociology, synthesized through a lyrical reflexivity. According to

Ball (

1998, p. 137), researcher-generated photographic reflexivity is necessary because ‘as a form of data, photographs are not capable of talking for themselves’—that the ‘information has to be teased out of them, interpreted and encoded’, in which the ‘availability of the phenomena has to be unpacked’.

(Some of these critical explorations have been truncated for practical reasons). The purpose of the allusive and eclectic interpretations of several photographs featured in the text are there to engage the reader, while revealing the biographical bias of the researcher, and why the researcher might frame certain iconographic opportunities. And the aftermath of the photographic act (away from the research site) is equally important, in providing duration and space for semiotic analysis and reflexivity. We might reflect on whether the contemplation of the uploaded photographs to the computer screen retains the heightened experience of resonance, or is this residual, or transient? And what of the reader? Do they experience resonance when encountering these reproduced representations, or do they at least stimulate their own inquiry into places of rewilding?

Nevertheless, photographs do ‘talk’, even though they may talk to different readers in different ways. (Even words are dormant, until decoded by the reader). The photographic ‘information’ that Ball refers to still exists, albeit open to various semiotic analyses. Therefore, it is not a matter of ‘teasing out’ this information, but rather an interpretative attitude of openness to possible signification based on several factors, including cultural context—where we encounter the photograph(s). And importantly, in relation to the truncated selection of photographs reproduced here, we must recognize, as Ball insists, that photographs ‘do not and could not comprise a complete or fully systematic record of the scene or scenes depicted’ (

Ball 1998, p. 141).

In considering the validity of the photographic document in qualitative research,

Adelmann (

1998) proposes that each photograph functions as ‘an extension of the photographer’, within the context of self-awareness and reflexivity (1998, p. 148). The intention to contribute to the construction of knowledge and the current debates related to the working countryside and nature’s restoration through visual practice and reflexivity is supported by

Pink (

2007, p. 118), in which ‘visual research (…) means scrutinizing the relationship between meanings given to photographs and the academic meanings’ attributed to the same photographs.

In short, the integration of photography and text seeks to illuminate the ideological and aesthetic tensions that exist in the UK countryside, a situation compounded by the challenges facing agriculture: the demand for ‘net zero’ targets, food security, infrastructure, affordable housing, and ecological restoration.

And even though it impossible to include all 800+ research photographs taken over the nine-year period in this paper, I hope that the seven researcher-generated photographs reproduced in the text adequately reflect the much larger archive, and do not function as mere discursive illustrations to add some visual light relief, but rather, they occupy the text with a critical purpose, performing a visual rhetoric that operates symbiotically with the text, to contribute to the current debates on rewilding, how land is valued, and for whom.

What is apparent, is that the relationship between the rewilding landscape and resonance remains elusive, and resistant to definitive meaning-making. And perhaps, that is how it should remain—without a definitive commodification.

Nevertheless, researcher-generated photographic practice must believe that it is still possible to offer a reconceptualization of resonance, in which the re-presentation of those overlooked places promises a wilder encounter.