1. Pierre Schaeffer’s Artistic Machinism

When Benjamin (

Benjamin [1931] 1999) described the “optical unconscious” revealed by photographic machines, it was to emphasize that photography and cinema reveal—through magnification, slow motion, and other strategies—aspects of physical reality that escape our ordinary consciousness, in the same way that psychoanalysis reveals aspects of our psychic reality that escape our ordinary consciousness. He adds that this optical reality is both 1/the unveiling of underlying structures (for example, the weaved pattern of a material filmed at close range, or the regular curve of a rapid movement) and 2/ the appearance of images akin to “waking dreams”: the aspects of “the smallest things (…) which [become] enlarged and capable of formulation” (

Benjamin [1931] 1999, p. 512). The optical unconscious thus bears a double resemblance to the drives-based unconscious, both epistemically (the production of a new knowledge of the world) and phenomenologically, since its mode of appearance of things resembles the flows of waking dreams.

Like Benjamin, but also Paul Valéry, Pierre Schaeffer considers that sound and optical machines are not just prostheses, but grounds for a new sensitivity not only to materiality but to human perceptive or psycho-perceptive activity itself, overturning the traditional relationship between subject and object. For Schaeffer, preceding Jonathan’s Crary’s (

Crary 1990) clear formulations of the same idea by some years, the “observer” becomes the center of the machines and the artworks.

Far from distancing us from ourselves, machines bring us back to ourselves. So much so that human beings endowed with sensibility, such as artists, can find new grounds for creation by finding, as Benjamin contends, the means to make these perceptions “capable of formulation”. In his December 1949 lecture at the Centre d’Études de la Radio (CER)—published the following January in an internal CER brochure (

Schaeffer 1949)—Schaeffer framed what he called the “creative power of the machine” from this perspective. His 1970 text introduces a crucial addition to the latter—which will be the basis of the argument here—namely, that the way artists imagine machines plays a decisive role in their creative practice.

Because it escapes the artists themselves, this imaginary is in a way the other unconscious of the machine, telescoping the potentialities offered by the first one, resulting in many illusions and disappointments. However, it may indeed also become itself a new field of possible operations. Schaeffer’s reflections remain highly relevant today for thinking about the digital unconscious of or in cinema and audiovisual media. Digital images and sounds can be productively read in the light of his reflections, not only insofar as they modify images and sounds in new ways, but also insofar as they mobilize artists’ unconscious of the digital machine, as we’ll see through a theorical discussion. This Schaefferian thesis challenges a blind spot in research on digital images, which rarely questions what artists unknowingly project onto machines.

The analysis presented here draws primarily on his text “Le machinisme artistique” published as a chapter at the beginning of

Machines à communiquer in 1970 (

Schaeffer 1970), but some passages of which were first written during the 1960s, notably in a 1963 text entitled “L’art et les machines” (

Schaeffer 1963). This three-part text contains in 1970 a revealing self-criticism. The first part, the one already written in 1963, classifies artists according to their attitude to machines; the second, rewritten, examines how the Muses deal with the new media of sound and image; the third, which is new, proposes a typology of machines. The last type of machine, the “communication machine”, gives the whole book its title. So, this is not a minor issue for Schaeffer.

Artists who refuse to enter into a genuine, destabilizing relationship with machines instead make fun of them, deride them as Tinguely did. These are the purists. Those who delegate all power to machines, the “progressives” who consider them as “subjects”, including Xenakis who sought to compose music through pure random mathematics, forget that art and meaning are problems for humans and not for machines. In so doing, they fail to understand the unconscious dimension revealed by machines, this new material which, as Schaeffer argued in 1963, consists in the fact that machines refer us back to our own activity of perception: “The object of art is within” (

Schaeffer 1963).

Those who find compromise with the machines, the “accessoiristes” (prop masters, but in French “accessoire” means also secondary, marginal), don’t really take the potential of the instrument itself seriously. As a result, they subordinate the machine to another purpose: however, video-enhanced theatre may be, it remains theatre. The inability of these three artistic positions to truly come to grips with the impact of machines, which Schaeffer humorously figures as a cataclysm disorienting the Muses of the classical arts, is why he calls for us to shift our focus away from abstract discussions of Art and attend more closely to the specificity of communication machines, that is, those of sound and image.

In other chapters of his book, audiovisual (mass) media are examined as a professional organization and as a social and political institution (the mediatic dimension). Schaeffer, however, considers it essential to begin with what could be called the “medial”

1—that is the material, technical, machinic—dimension of media (

Soulez 2015).

Self-critical in the text “Artistic Machinism”, Schaeffer acknowledges that he too once believed in the “creative power of the machine”, following artists who envisioned a new Subject: “we ourselves, forgetting their genesis, started from machines to study the reactions of men”. To avoid this mistake, “we must, [on the contrary,] start from the man who invents machines, from what he invents them for, and from what they enable him to do” (

Schaeffer 1970). On this basis, he thus defends a fourth type of relationship to the machine, one that is productively instrumental: recorded sound and image can then be played with, as he did when he “invented”

musique concrète in 1948. More precisely, it should be said that

recorded sound can be played, in the same sense that one plays the violin (without the

with).

Schaeffer thus invites a recognition that thinking about machines in relation to the unconscious usually avoids the crux of the issue (projection on machines as machines), machines being usually treated either too platonically or, conversely, without questioning the extent to which the sound or visual machine compel a rethinking of art and perception when they are reduced to mere props for other purposes. He thus terms this fourth relationships “artistic machinism” and situates it within the broader question of the relationship between art and machines. Otherwise, neglecting this step means becoming victims of our own projections onto machines, and one could say that we become machined humans.

Only under this condition, he believes, can the potential at stake—not that of the machine itself, but of what it reveals about us when dealing with them—enable us to take advantage of the new possibilities offered by cinema, radio, television, and other media. This potential involves managing the optical or sonic unconscious by distancing ourselves from our ordinary perceptions of the world and, as Schaeffer emphasizes at the end of his text, conserving the ephemeral (recording) and separating perceptual unity (notably sound from image, contrary to our primary experience of the world).

The image below from Gérard Patris’s film

Caustiques (1960) exemplifies Schaeffer’s idea of a work on the image itself. A reflection developed through machinery, produced at the Service de la Recherche (SR, an experimental laboratory he directed from 1960 to 1974 within French public television), and similar to the illustration accompanying his previously mentioned 1963 article (

Schaeffer 1963), it demonstrates how photography and cinema, as they are first and foremost machines of light, can record the phenomenon known as the “caustic” in optics (

Figure 1).

In this film, light is “played” (not simply played with as in shadow puppetry). It stands at the center of the artistic experience, while the photographic or filmic machine does not disappear from this experience. This centrality of light would later become one of the components of the non-figurative film La Chute d’Icare (Gérard Patris, The Fall of Icarus, SR, 1960), where it is symbolically linked to the sun, the originary source of light. The film may thus suggest a way of creating figures capable of formulation out of physical phenomena that usually remain invisible. At the same time, it demonstrates how the Schaefferian sensibility focuses as much on the relationship between technique and reality (the material commonality of light linking machine and reality) as on what the technique reveals of reality (the machine merely reveals certain aspects of light).

The global spread of radio, cinema and television, so alarming to his contemporaries preoccupied with the influence of “mass media,” seems to Schaeffer less fundamental than the mode of production of these images and sounds itself. In short, if a psychoanalytic model is operative here, he remobilizes it to call on artists to undertake a form of self-criticism or self-analysis—to step back from their own artistic unconscious, from the extent to which they themselves become the playthings of problematic, idealistic or superegoic conceptions of art, which they project onto machines.

Just as scientific fables since the Renaissance have shown, machines do not operate to enable progress; if anything, the opposite seems to hold true, as Schaeffer quips in an interview with a journal of futures studies: “it is utopia that makes machines work” (

Lichnerowicz et al. 1973).

2. Digital Images and Sounds from a Schaefferian Perspective

As we wrote above, digital images and sounds can be productively read therefore in the light of Schaeffer’s reflections, not only insofar as they modify images and sounds in new ways, but also insofar as they mobilize artists’ unconscious of the digital machine. More precisely, as with the case of conservation and separation, what the digital can do to images and sounds thanks to computational processes (perhaps another kind of separation?) can only be truly understood when set in relation to what human subjects, and artists in particular, wish to do with the digital, without necessarily being aware of it. Following Schaeffer, digital images and sounds may then be grasped more fully and put to productive and compelling use for our sensibility. Greater lucidity about this unconscious relation to the digital machine allows for an attunement to the new optical and sonic unconscious brought to light by the digital.

Might, then,

The Matrix’s famous “bullet-time” be said to introduce a new dimension of reality? (

Figure 2). At first glance, it seems to celebrate the new human power to stop time (and therefore death) by dodging a bullet. But is “bullet time” anything more than slow motion? Have we truly progressed beyond the optical unconscious that Epstein identified as the “intelligence of the machine” (

Epstein [1946] 2014)? If Epstein’s “progressive” impulses make us smile today, at least slow motion corresponds to a real phenomenon. By contrast, in

The Matrix it is not time itself that is stopped by digital means, but a

false slow motion that is produced (from a technical point of view, no scrolling is slowed down). Is the digital here a simulacrum of the simulacrum

2, distancing us from our relationship with a world full of technologies, even as the film claims to warn us about it? In this sense, while

The Matrix is a dystopia, rich in political and philosophical significance, it nevertheless manifests a highly conventional imaginary of machine mastery, as if digital technology could abolish the limits of analog capture, celebrating the mastering of time by a new Prometheus. Epstein’s slow-motion images, on the contrary, offer a reflection on the limits of human perception of the world.

Schaeffer’s three categories of artistic attitudes can certainly be identified nowadays, along with those who, conversely, maintain a productively instrumental relationship to this new optical and sonic unconscious (

Table 1). The idea here is not to develop analyses of the works cited (except for the last one), but rather to suggest, on the one hand, that the Schaefferian perspective seems relevant since this line of inquiry can immediately shed light on contemporary digital productions despite the historical distance, and on the other hand, that it opens up avenues of research for approaching these works.

In the same way, when films claim to mobilize ever more extraordinary new techniques than their predecessors to represent imaginary worlds or dystopian futures, an archaeology of the science-fictional unconscious could situate these films within a genealogy while questioning their capacity to genuinely interrogate the potentials of the very techniques they employ.

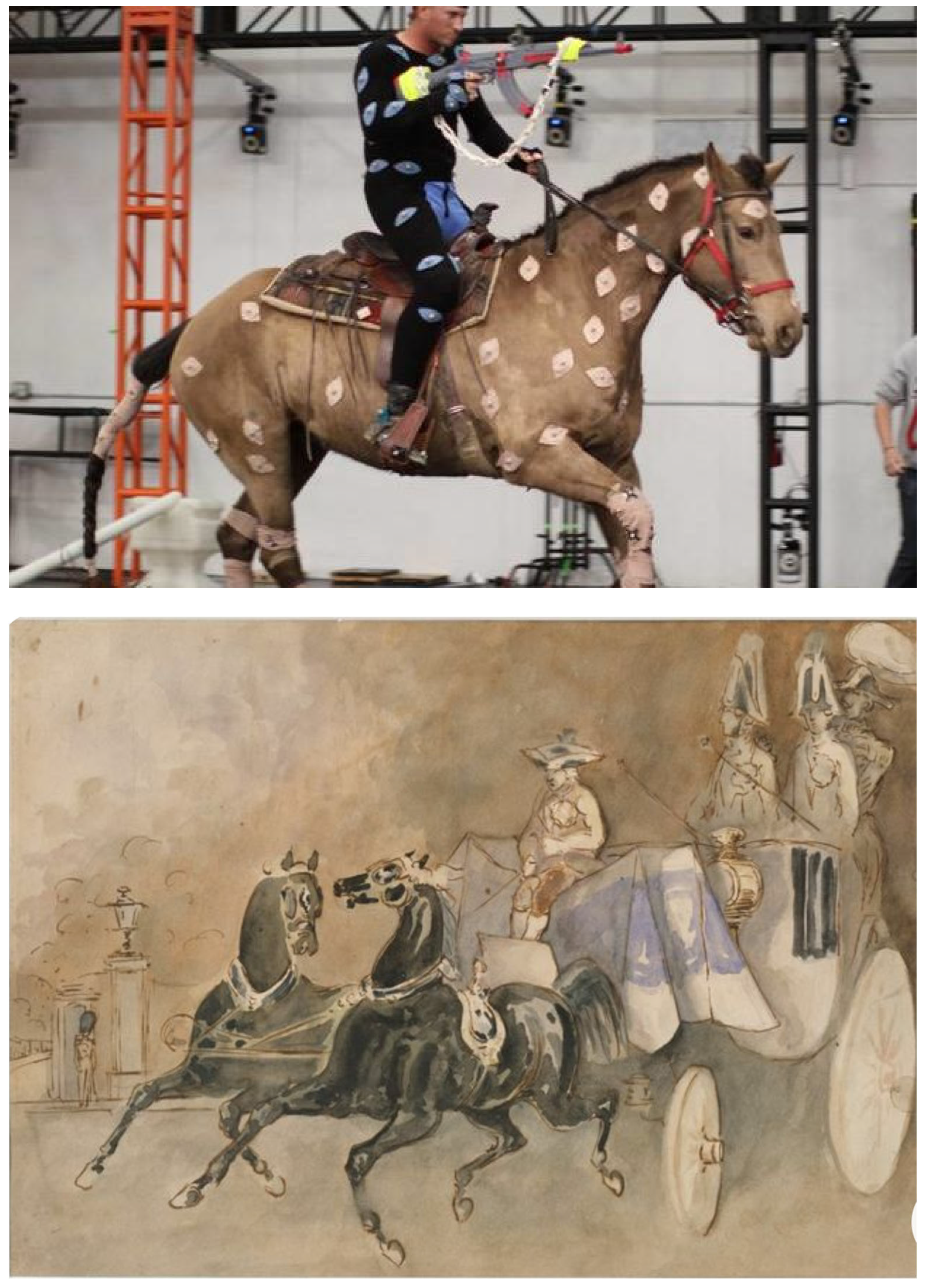

Furthermore, the gap between the photorealistic rendering of motion capture and the loss entailed by sensor analysis could be explored in relation to the more imperfect human hand-drawn line, which captures—interprets—an energy or even fabricates a form that is neither entirely in reality nor entirely in the human mind. This recalls the well-known Baudelairian perspective on “modernity” (

Baudelaire [1863] 1965) which may be applied as much to animation drawing as to the framing of a body in motion (comparison between

Figure 3).

A further approach might be to cross-reference the types of machine distinguished by Schaeffer, since digital technology relies on what he refers to as a thinking machine, in the sense of a calculating machine. Significantly, Schaeffer associates such calculating machines with syllogisms that can be reduced to mathematical formulas (as in formal logic).

Without adopting a reactionary attitude—there’s no reason not to calculate everything available, even “uncertain foodstuffs that are not very well suited to calculation, psychological elements, sociological responses and musical notes”—Schaeffer remains ironic, doubting whether such operations will teach us anything in these areas. Rather, the theme of reduction interests Schaeffer here, not that of fidelity or originality.

The list of possible lines of inquiry could continue: to what extent do audiovisual media always involve a reduction in experience and, since calculation tends to be reductive, to what extent, conversely, can an experimental approach resist reduction, whether by disrupting calculation, by mixing digital and non-digital regimes, or by foregrounding reduction itself, that is to say the limits of the digital itself?

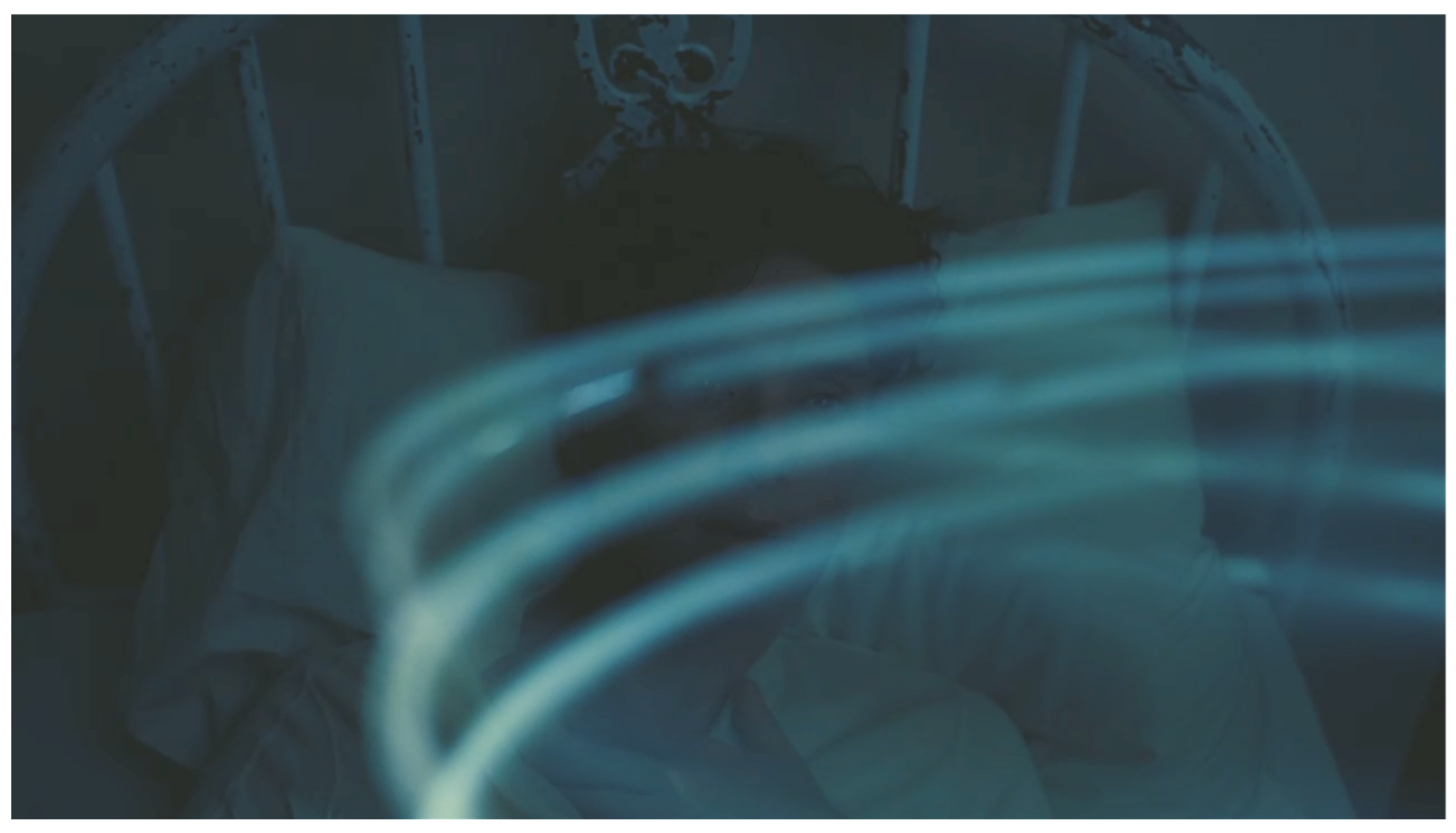

3. A Case-Study: Oppenheimer’s Reveries

Oppenheimer’s reveries in Christopher Nolan’s film (Oppenheimer, Nolan 2023), soon after the beginning (between the fifth and the eighth minutes), are quite fascinating from this Schaefferian point of view, as they underscore the inability of digital representation to render the mathematical flows running through the scientist’s thoughts (

Figure 4). At least two types of non-realist images other than the mathematic figures can also be identified in this scene: on the one hand symbolic (or mythographic) images (fire, hubris), and on the other, “atomic” images (the image transformed by radiation, the result). The latter clearly conveys the protagonist’s sense of culpability of the main character, appearing as distinct hallucinations.

However, at the level of the viewers’ conscious engagement with their conception of digital machinery, these specific mathematical reveries ultimately share Oppenheimer’s frustration at the failure of the images (inner for him, materialized onscreen for the audience, with the superimposition in between the two). They do so even though these images are clearly presented at the end as calculations that yield no definitive result or form, thereby provoking a form of reflexivity in the viewer. This effect is reinforced by the length of the sequence, which is itself diegetically motivated by Oppenheimer’s torments as he searches for a new quantum representation of reality (unlike the atomic images, these are not deformations of reality by a sick mind).

In this sequence, the digital appears as an attempt to find a graphic equivalent of what unfolds in Oppenheimer’s mind. Different images are proposed, more or less—and in fact rather less—connected to each other. The film appears as a “machinery” (and not as a mere tool) in the sense that the notion of machinery implies what we project onto it. The digital machinery, in this view, stands between the viewer and the images it has produced.

At an initial, Benjaminian, level (close to Benjamin’s reflections on the optical unconscious), the adequation of the digital flow with the mathematical reveries suggests how cinema may reveal an optical unconscious of our usual relationship to reality, by emphasizing the continuities between the material world and the inner world, against the separation between subject and object. However, at a second, Schaefferian, level, the questioning of the machinery of images by the digital film opens another perspective: what images, and image machines themselves, can do for our understanding of reality, which is quite different from the first level. It is not a question of (better) capturing reality, but rather of questioning the reasons why we, humans, seek to capture reality (with machines).

It is therefore incumbent to keep in mind that the digital unconscious may designate the unconscious ways in which we think about the digital, which effectively frame our appreciation of digital creations.

Second, the fact that these machines are at once machines of perception and of calculation forces us to shift our expectations towards image and sound technologies. Contrary to the expectations associated with analogical images and sounds as icons (using C. S. Peirce’s vocabulary), and despite the increasing photorealism of the digital (Oppenheimer itself uses IMAX technology), digital image and sound machines must paradoxically be regarded as schematic reductions in our perceptions, against centuries of visual and auditory habits oriented toward the enrichment of perceptual and communicative experiences.

More is less could be the lesson of the digital unconscious.