Melomaniacs: How Independent Musicians Influence West Hollywood’s Cosmopolitanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

WeHo: The Creative City

“Most cities import culture. In West Hollywood, we export it.”—John D’Amico, West Hollywood Mayor, 2014–2015, 2019–2020

2. Data and Methods

“So, my identity is black, gay artist. And I’m left-handed.”—Colten, 54, voice/piano, male

2.1. Arts-Based Research (ABR)

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analytical Strategy: Interactionism and Post-Postmodernism

2.5. Creative Data Sharing: Engaging the Public Imagination

2.6. Limitations

3. Findings

“I would say, like, 98% of my life is with music in my ears.”—Mary, 27, voice/electric guitar, female

3.1. Authentic Musicality and Self-Expression

“Why am I still a musician? Because I love it. It brings me joy like nothing else, to be able to connect with somebody while playing music and to just be on the same beat as somebody, like physically, and just being in the same moment as somebody.”—Aria, 29, voice/collaborative pianist/conductor, female

“It [music] was something I could do when I was a little child. And it’s almost like I already knew music when I came to this life. I already knew how things worked, no one had to tell me so. It embodies more than your feelings. It embodies your whole spiritual, mental, physical, everything self. So, I don’t even think of myself as a musician. I just do it at this point. I can’t do anything else. I mean, I don’t think I could do anything else.”—Jolene, 81, piano, female

“It’s just because there’s really nothing else and I don’t have any reason to look for anything else. I’m going to live and die as a musician, and I’ll play up until the day I drop. Because this is what I do. This is who I am. And it’s important.”—Toby, 61 piano, male

“I felt almost as if I didn’t really have another choice, that it was so ingrained in me to play music. I tried to do other things when I was in college, but music was always the thing that gave me inspiration and energy. And when I woke up in the morning, that’s what I thought about and wanted to do… and even after 30 years of touring, it’s still the main driving force. Music was something that I excelled at. And you know, it would have been easier if I would have chosen something else. And it’s not an easy life. But I just can’t imagine doing anything else.”—Peter, 59, acoustic guitar, male

“I came through classical music and commercial artist fame was not ever a consideration. I mean, maybe you’ve heard of one flutist in the last generation that’s a household name? And we [musician spouse] have made a lot of connections with the film music industry, film music composers, but we’re always on the artistic side of it. My goal was always to be a musician and somehow be middle class at the same time. And that was, like, really what I hoped to be.”—Sage, 44, flute, female

“I honestly thought it was just going to be too far-fetched to ever get signed. But I think I had to convince myself it wasn’t about getting a label or getting a contract. It’s just about spreading good vibes, you know? And yes, it is the dream, if I could be on the radio, it would be beautiful. But it’s such a bullshit industry that I’m not going to let that take away from my joy.”—Johann, 29, guitar/piano/composer, male

“Are you there for the fame or are you there for the art? I think there’s something natural and healthy about wanting to be compensated for what you bring to the table. That’s one thing. Another thing is if you’re in a fame mindset and nothing else matters, then that’s where your mindset is. For me, it’s that I connect to music… there’s a relationship between music and me. If you picked it for fame, this is what you’re going to go for. But the connection that you have and the satisfaction that you get out of pursuing your art? I think there’s a reward there.”—Donovan, 62, guitar, male

“No one said it was going to be easy. That was in the brochure… and anyone who’s successful in the music industry, as a performer, they are doing what they need to do to be successful. They are singing songs that are tailored to make them the most marketable, songs about things that will sell the best. Now, some might call that selling out, but I disagree. They’re just using their musical skills to be funded as a musician. I don’t think that’s selling out. Frankly, if you’ve heard of anybody, it’s because they’ve sold out in some way.”—Presley, 44, oboe/conductor/composer, male

3.2. Legitimacy from (Live) Audience Connections

“I think if I zoom out, then, of course, I don’t want to just do this for myself.”—Dylan, 29, voice/piano, male

“[Success is about] When I get to produce the music that I want to produce on my terms, you know, professional and artistic terms.”—Donovan, 62, guitar, male

“Does it make me happy? Am I satisfied? If it’s not making you happy, you’re not successful. Like, why are you doing it? If you’re not passionate about it, it’s not going to make you happy either. And if you’re not giving something of value to people in whatever you do, that’s not success to me. That’s gonna make me cry.”—Kamille, 63, voice, female

“I can tell I’m making a positive difference. I will go to Pride, and I will get up with a microphone for five minutes and say something and people will thank me. And I try to carry that gratitude and let it stay with me, so I can remember why I do this and why it’s so important that I never stop.”—Sutton, 25, voice/composition, nonbinary trans

“My minor is in rhetoric. Like the big thing about rhetoric is that there’s the writer and the reader or the speaker and the audience. And some may define rhetoric as the relationship between the two, which is like, ‘Hello?’ That’s, like, music. That’s music performance for me.”—Harmony, 32, violin/viola/voice/piano, female

“I’m thinking about how much joy can I radiate from this music? How much joy can I allow myself to channel? Like how much passion can I channel through me and hopefully somebody sees that in the audience. I think it’s more like you become a vessel for you and you become a vessel for the art. You become the vessel for the intangible.”—Aria, 29, voice/collaborative pianist/conductor, female

Social Media Connections

“They can be impressive for 45 seconds and get their thumbs up. Its success is to the detriment of the actual music world… and music in general.”—Toby, 61, piano, male

“I love playing live. I grew up playing live. In terms of the audience, I just feel like that’s how I can really minister, like in live space more than on the Internet. Access to playing live is now mitigated by social media, and if you want bigger touring opportunities, you need a bigger following and more Spotify streams. So, if I really want to be on tour, I got to win online first.”—Messiah, voice/piano/songwriter, 34, nonbinary

“Most regular citizens don’t know how to value an artist. Your sense of potential or status is through social media. And if they see you’ve got a viral video or say, ‘Oh, you were in something with a million views!’ or ‘you’ve got 10,000 followers!’ or whatever it is, your stock starts to go up in their mind. Which is not to say it’s not legitimate, I’m just saying it’s only one way to view the world… through financial creation and value creation.”—Nadia, 32, violin, female

“You get these people who have lots of fans and followers on their social media. And a record label swoops in and helps them with the creation and marketing of a song and those people may or may not have put in the time in the years to be developed as an artist. And if they’re not developed, as many of them aren’t sometimes, you don’t really get, like, a big artist’s career from that. You get, like, a temporary moment. And that’s not necessarily what I would view as success because that’s not an artist career. It’s just a moment in time. And then the movement fades and society moves on.”

3.3. Intimacy and Inclusivity Within WeHo’s Music Worlds

“West Hollywood is an idea that is so necessary for the survival of those of us who are not from here and who look towards this beacon with hope that we might get to be ourselves one day.”—Eric, 36, voice/composer/conducting, male

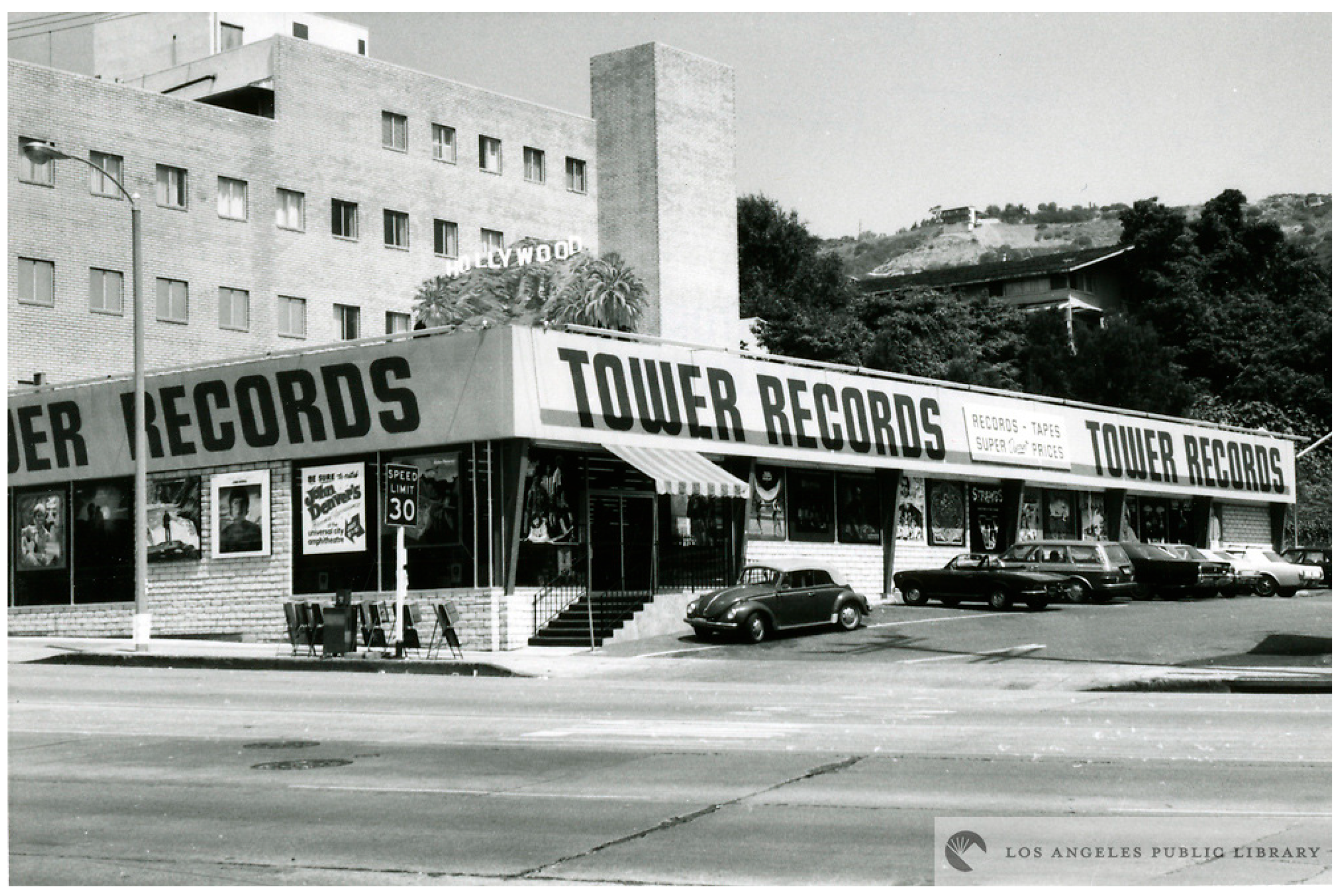

“I remember going in and finding our album and seeing our trio’s name card on the CD stack. And that was a significant moment where I had felt we had achieved some amount of success… that we’re in West Hollywood, in Tower Records, and we had our own name card.”

“Everyone here wants to see what someone can come up with and that’s a wonderful way to operate. As an artist, that’s an immense amount of freedom you can feel. I am a better artist for being here. If I had stayed in the Midwest and stayed playing in the orchestras, playing all that music, I would not be a tenth of the musician that I am now. From being here for ten years and hearing all of the music and seeing all of the performances and meeting all the people that I’ve met here and experiencing the life here.”—Presley, 44, oboe/conductor/composer, male

“My first experience living in West Hollywood was when I was 19 years old in 1975, sleeping on the couch. There is such a treasure trove of artistic spaces… there’s a place here for me. WeHo is my artistic home. I might reside in another town now, but WeHo is absolutely at the very center of my artistic spirit.”—Laurel, 68, guitar/piano/conducting, female trans

“I see WeHo definitely as a safe space for queer people, as a place with really strong connections to art and to queer culture, queer community. It matters a lot to me that I have so many options of places to go to be with… be with people like myself. We have a lot of alphabet soup here.”—Sutton, 25, voice/composer, nonbinary trans

“Growing up gay and growing up with ADHD I felt there were lots of threats to my sense of belonging in the world… music was something that I was really good at and something that I was consistently validated for. I latched onto as a sense of like, this is how I can belong to a tribe. Like this is going to be where I can source my self-worth from.”—Dylan, 29, voice/piano, male

“As a queer person, music was always a way where I could say, ‘Here’s a little piece of myself that I would not be able to express otherwise.’ And beyond that, there is something so wonderfully queer to artmaking. Obviously, straight people can make great art, but sometimes humans are best when there is diversity, when there are multiplicitous points of view and means of expression. And I think that is part of the queer aspect of humanity here [in WeHo]. It’s like an ability to not be stuck to sameness.”—Johann, 29, piano/guitar/songwriter, male

3.4. Emerging Theories Within Findings

3.4.1. Independent Musicians as Cultural Omnivores

“There’s so many different types of music happening in L.A. and WeHo, and there’s so many different types of work you can do as a musician every day… I don’t know what that is, but there is some invisible fiber there. It’s like a root system, but it starts to expand kind of as one.”—Nadia, 32, violin, female

“I feel like there is a willingness to want the arts around here [in WeHo], like all music, dance, visual arts, all of them together, regardless of genre or anything. I feel like everyone here wants it in different ways. But they want it to be around.”

3.4.2. Independent Musicians Embracing Postmaterialism

“Well, my mother said it [conservatory] would be such a waste of your brain… she just wanted safety and security and a happy life… we, I think, built a very different life than what she maybe had pictured.”—Sage, 44, flute, female

“There’s no rational reason for it. There are moments in a performance, whether you’re playing or listening, or even if you’re listening to a recording, where something happens that it just, I don’t want to use the word transcendent, but it’s so powerful and so personal that I think it’s the juice that keeps you going to the next thing. And at a certain point, you’ll keep doing it whether you get paid or not.”

3.4.3. Moral Capital in West Hollywood

“I think if you want to take this and make it more into a career, you can do it here in West Hollywood. You can have that experience here. And I think if you know where to look and you’re an artistic person, and no matter how you identify, you can live here and have a full artistic life.”—Carl, 30, voice/guitar/songwriter, male

“I just ingratiated myself in West Hollywood almost strategically because, well, this is where the opportunities are. I’ve always been such an interdisciplinary fan. And WeHo really lives that value. They have a commission for everything. They think about how urban art intersects with infrastructure in a way that forces this level of connection at different parts.”

4. Discussion

“When I meet someone new and tell them I’m a musician, I find they either think I’m a rock star or I’m just crashing on my girlfriend’s couch without a job. They don’t seem to know or are not aware of the middle ground, the working musician… we call each other ‘blue collar artists.’”—Linus, 48, double bass/electric bass, male

4.1. Cosmopolitanism

4.2. Musicians’ Influence on West Hollywood’s Cosmopolitanism

5. Conclusions

“I think it’s okay to ask that [what’s your day job?], but it’s what comes next that is the issue… the disbelief, or the asking a second time. And I think some people are genuinely curious. But I do think it would be fun to ask someone who says they’re an accountant or an investor or they do insurance, ‘Oh, is that all you do?’ It would be fun to see what they say.”—Nadia, 32, violin, female

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Questions not to ask working musicians: (1) What’s your day job? (2) How much money do you really make in this city playing music? and (3) Do you have a “real” job? |

| 2 | Crossley’s “music worlds” concept denotes a relatively cohesive cluster of musical interaction (i.e., West Hollywood) within the broader universe (i.e., greater Los Angeles area) of such interaction in a society (Crossley 2025, p. 160). |

| 3 | The Tower Records in West Hollywood opened in 1971 and was the first Southern California location of the Sacramento-based chain, and arguably, the most famous. It closed in 2006 when Tower Records went bankrupt. In 2023, Supreme—a retail store primarily selling clothing, accessories, and skateboards—renovated the building and opened in the location. |

| 4 | A derogatory nickname referring to the glitz and glamour yet often fragile or superficial world of entertainment in Los Angeles. |

References

- Adler, Laura. 2021. Choosing Bad Jobs: The Use of Nonstandard Work as a Commitment Device. Work and Occupations 48: 207–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, Patrick, and Taner Osman. 2025. Otis College Report on the Creative Economy. Available online: https://www.otis.edu/about/initiatives/documents/25-063-CreativeEconomy_Report4_250325.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Albinsson, Staffan. 2018. Musicians as Entrepreneurs or Entrepreneurs as Musicians? Creativity and Innovation Management 27: 348–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, Arthur S., Azamat Junisbai, and Isaac Heacock. 2007. Social Status and Cultural Consumption in the United States. Poetics, Social Status and Cultural Consumption in Seven Countries 35: 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Ray. 2010. In Pursuit of Authenticity: The New Lost City Ramblers and the Postwar Folk Music Revival. Journal of the Society for American Music 4: 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, Neil O., and Gregory H. Wassall. 2006. Chapter 23 Artists’ Careers and Their Labor Markets. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. Edited by Victor A. Ginsburg and David Throsby. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Americans for the Arts. 2023. Arts & Economic Prosperity 6 (AEP6). Available online: https://aep6.americansforthearts.org/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Back, Les. 2023. What Sociologists Learn from Music: Identity, Music-Making, and the Sociological Imagination. Identities 31: 446–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, Irene, and Diana Tolmie. 2018. What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life? A Profile of Jazz/Contemporary Voice Graduates. International Journal of Music Education 36: 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baym, Nancy K. 2013. Fans or Friends?: Seeing Social Media Audiences as Musicians Do. Matrizes 7: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Howard S. 2023. Art Worlds, 25th Anniversary Edition: 25th Anniversary Edition, Updated and Expanded. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Andy. 2017. Music, Space and Place: Popular Music and Cultural Identity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Dawn. 2008. A Gendered Study of the Working Patterns of Classical Musicians: Implications for Practice. International Journal of Music Education 26: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertacchini, Enrico, Valentina Bolognesi, Alessandra Venturini, and Roberto Zotti. 2021. The Happy Cultural Omnivore? Exploring the Relationship between Cultural Consumption Patterns and Subjective Well-Being. SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3934767. Rochester, NY. October 8. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3934767 (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Blake, George. 2021. A Tale of Two Cities (and Two Ways of Being Inauthentic): The Politics of College Jazz in ‘Official Cleveland’ and in the ‘Other Cleveland’. Ethnomusicology 65: 549–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1985. The Genesis of the Concepts of Habitus and Field. Sociocriticism 2: 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bridson, Kerrie, Jody Evans, Rohit Varman, Michael Volkov, and Sean McDonald. 2017. Questioning Worth: Selling out in the Music Industry. European Journal of Marketing 51: 1650–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, Anna, and Christina Scharff. 2017. ‘McDonald’s Music’ Versus ‘Serious Music’: How Production and Consumption Practices Help to Reproduce Class Inequality in the Classical Music Profession. Cultural Sociology 11: 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, Anna, and Christina Scharff. 2021. Classical Music as Genre: Hierarchies of Value within Freelance Classical Musicians’ Discourses. European Journal of Cultural Studies 24: 673–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, Craig. 2020. 14. A Cosmopolitanism of Connections. In Cosmopolitanisms. Edited by Bruce Robbins and Paulo Lemos Horta. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Amanda. 2016. WEHO Arts: The Plan. City of West Hollywood’s Arts Division and Arts and Cultural Affairs Commission. Available online: https://www.weho.org/home/showpublisheddocument/36882/636682845500500000 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Cech, Erin. 2021. The Trouble with Passion: How Searching for Fulfillment at Work Fosters Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, David, and Lisa Kaida. 2020. Harmonic Dissonance: Coping with Employment Precarity among Professional Musicians in St John’s, Canada. Work, Employment and Society 34: 407–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Tak Wing. 2019. Understanding Cultural Omnivores: Social and Political Attitudes. The British Journal of Sociology 70: 784–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Terry, and Larry Gerston. 1987. West Hollywood: A City Is Born. Cities 4: 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchelli, Vincenzo, and Sylvie Octobre. 2018. Omnivorism and Aesthetico-Cultural Cosmopolitanism. In Aesthetico-Cultural Cosmopolitanism and French Youth: The Taste of the World. Edited by Vincenzo Cicchelli and Sylvie Octobre. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of West Hollywood. 2024a. Open Data. Available online: https://data.weho.org/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- City of West Hollywood. 2024b. West Hollywood’s ‘Top 20’ List. Available online: https://www.weho.org/city-government/communications/media-relations/top-20-list (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Cloonan, Martin, and John Williamson. 2023. Musicians as Workers and the Gig Economy. Popular Music and Society 46: 354–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Randy. 2016. National Arts Index 2016. An Annual Measure of the Vitality of Arts and Culture in the United States: 2003–2013. Available online: https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/NAI%202016%20Final%20Web%20Res.042216.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Corman, Jordan. 2019. Artist Managers and Their Impact on Clients’ Career Success. Purchase College—State University of New York (PC). Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/14627 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Coulson, Susan. 2012. Collaborating in a Competitive World: Musicians’ Working Lives and Understandings of Entrepreneurship. Work, Employment and Society 26: 246–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, Nick. 2020. Connecting Sounds: The Social Life of Music, 1st ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvt6rk0h (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Crossley, Nick. 2022. From Musicking to Music Worlds: On Christopher Small’s Important Innovation. Music Research Annual, From Musicking to Music Worlds: On Christopher Small’s Important Innovation 3: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, Nick. 2025. Music Worlds and Event Networks: An Exposition. Cultural Sociology 19: 159–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, Nick, and Rachel Emms. 2016. Mapping the Musical Universe: A Blockmodel of UK Music Festivals, 2011–2013. Methodological Innovations 9: 2059799116630663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currid, Elizabeth, and Sarah Williams. 2010. Two Cities, Five Industries: Similarities and Differences within and between Cultural Industries in New York and Los Angeles. Journal of Planning Education and Research 29: 322–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Mike. 2007. Riot Nights on Sunset Strip. Labour Le Travail 59: 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Delanty, Gerard. 2006. The Cosmopolitan Imagination: Critical Cosmopolitanism and Social Theory. The British Journal of Sociology 57: 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenfeucht, Renia. 2013. Nonconformity and Street Design in West Hollywood, California. Journal of Urban Design 18: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, Benjamin. 1995. West Hollywood as Symbol: The Significance of Place in the Construction of a Gay Identity. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 13: 133–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenette, Alexandre, and Timothy J. Dowd. 2018. Who Stays and Who Leaves? Arts Education and the Career Trajectories of Arts Alumni in the United States (Working Paper). Washington: National Endowment for the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, Norm, Carina Henriksson, and Tone Saevi, eds. 2012. Hermeneutic Phenomenology in Education. Rotterdam: SensePublishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, M. F. 2003. What Makes Music Work for Public Education. Journal for Learning through Music 87: 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Godden, Lorraine, and Benjamin Kutsyuruba. 2023. Hermeneutic Phenomenology. In Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods: Selected Contextual Perspectives. Edited by Janet Mola Okoko, Scott Tunison and Keith D. Walker. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazian, David. 2004. Opportunities for Ethnography in the Sociology of Music. Poetics, Music in Society: The Sociological Agenda 32: 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfeld, Liah. 1984. The Role of the Public in the Success of Artistic Styles. European Journal of Sociology/Archives Européennes de Sociologie 25: 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Chong-suk, George Ayala, Jay P. Paul, and Kyung-Hee Choi. 2017. West Hollywood Is Not That Big on Anything but White People: Constructing ‘Gay Men of Color’. The Sociological Quarterly 58: 721–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, Jo, and Lee Marshall. 2018. Beats and Tweets: Social Media in the Careers of Independent Musicians. New Media & Society 20: 1973–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennion, Antoine. 1983. The Production of Success: An Anti-Musicology of the Pop Song. Popular Music 3: 159–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennion, Antoine. 2017. The Passion for Music: A Sociology of Mediation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoedemaekers, Casper. 2018. Creative Work and Affect: Social, Political and Fantasmatic Dynamics in the Labour of Musicians. Human Relations 71: 1348–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, Richard, Michael L. Dolfman, and Solidelle Fortier Wasser. 2007. The Economic Impact of the Creative Arts Industries: New York and Los Angeles. Monthly Labor Review 130: 21–34. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294187370_The_economic_impact_of_the_creative_arts_industries_New_York_and_Los_Angeles (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1988. Cultural Change in Advanced Industrial Societies: Postmaterialist Values and Their Consequences. International Review of Sociology 2: 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Ronald. 2015. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, Sunil. 2013. Artists by the Numbers: Moving From Descriptive Statistics to Impact Analyses. Work and Occupations 40: 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Maria-Rosario. 2004. Investing in Creativity: A Study of the Support Structure for U.S. Artists. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 34: 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvin, Linda, and Rena F. Subotnik. 2010. Wisdom From Conservatory Faculty: Insights on Success in Classical Music Performance. Roeper Review 32: 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffri, Joan. 2015. Information on Artists [1989, 1997, 2004, 2007, 2008, 2011]. Ann Arbor: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennex, Craig, and Charity Marsh. 2021. Introduction: Queer Musicking. MUSICultures 48: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Cathryn, Timothy J. Dowd, and Cecilia L. Ridgeway. 2006. Legitimacy as a Social Process. Annual Review of Sociology 32: 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafka, Kyriaki I., and Pantelis C. Kostis. 2021. Post-Materialism and Economic Growth: Cultural Backlash, 1981–2019. Journal of Comparative Economics 49: 901–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz-Gerro, Tally, and Mads Meier Jæger. 2013. Top of the Pops, Ascend of the Omnivores, Defeat of the Couch Potatoes: Cultural Consumption Profiles in Denmark 1975–2004. European Sociological Review 29: 243–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, Kristina. 2021. Producing (Musical) Difference: Power, Practices and Inequalities in Diversity Initiatives in Germany’s Classical Music Sector. Cultural Sociology 16: 174997552110394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, Luke Eric. 2005. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo3632872.html (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Leavy, Patricia. 2020. Method Meets Art: Third Edition: Arts-Based Research Practice, 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, George H. 1992. Who Do You Love? The Dimensions of Musical Taste. In Popular Music and Communication, 2nd ed. Sage Focus Editions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., vol. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, Danielle J., Steven J. Tepper, and Heather Laine Talley. 2017. ‘I Don’t Take My Tuba to Work at Microsoft’: Arts Graduates and the Portability of Creative Identity. American Behavioral Scientist 61: 1555–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingo, Elizabeth L., and Steven J. Tepper. 2013. Looking Back, Looking Forward: Arts-Based Careers and Creative Work. Work and Occupations 40: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, Anthony F. 2004. Bringing Music to the People: Race, Urban Culture, and Municipal Politics in Postwar Los Angeles. American Quarterly 56: 693–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusen, Ann. 2013. Artists Work Everywhere. Work and Occupations 40: 481–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusen, Ann, Sam Gilmore, Amanda Johnson, Titus Levi, and Andrea Martinez. 2006. Crossover: How Artists Build Careers Across Commercial, Nonprofit and Community Work. Americans for the Arts and University of Minnesota, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Available online: https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/crossover-how-artists-build-careers-across-commercial-nonprofit-and-community-work (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Maslen, Sarah. 2022. ‘Hearing’ Ahead of the Sound: How Musicians Listen via Proprioception and Seen Gestures in Performance. The Senses and Society 17: 185–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C. Wright. 2000. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Allan. 2002. Authenticity as Authentication. Popular Music 21: 209–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, Aline Pereira Sales, Daniel Carvalho De Rezende, and Alessandro Silva De Oliveira. 2021. Consumption and Social Distinction in the Cultural Field of Music. ReMark-Revista Brasileira de Marketing 20: 362–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Music Industry Research Association (MIRA). 2018. Inaugural Music Industry Research Association (MIRA) Survey of Musicians. Available online: https://psrc.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf1971/files/resource-links/report_on_mira_musician_survey.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). 2019a. Artists and Other Cultural Workers: A Statistical Portrait. Washington, DC. Available online: https://www.arts.gov/artistic-fields/research-analysis/arts-data-profiles/arts-data-profile-22 (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). 2019b. Arts and Research Partnerships in Practice: Proceedings from the First Summit of the National Endowment for the Arts Research Labs. Available online: https://www.arts.gov/impact/research/publications/arts-and-research-partnerships-practice (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Nault, Jean-François, Shyon Baumann, Clayton Childress, and Craig M. Rawlings. 2021. The Social Positions of Taste between and within Music Genres: From Omnivore to Snob. European Journal of Cultural Studies 24: 717–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negus, Keith, and Pete Astor. 2022. Authenticity, Empathy, and the Creative Imagination. Rock Music Studies 9: 157–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, George E., and Rosanna K. Smith. 2016. Kinds of Authenticity. Philosophy Compass 11: 609–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Saul. 2002. Constructing Political Culture Theory: The Political Science of Ronald Inglehart. Politics & Policy 30: 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pater, Walter. 1893. The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. Edited by Donald L. Hill. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2398/2398-h/2398-h.htm (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Peterson, Richard A. 1992. Understanding Audience Segmentation: From Elite and Mass to Omnivore and Univore. Poetics 21: 243–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Richard A., and Roger M. Kern. 1996. Changing Highbrow Taste: From Snob to Omnivore. American Sociological Review 61: 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflederer, Marily. 1963. The Nature of Musicality. Music Educators Journal 49: 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portman-Smith, Christina, and Ian A. Harwood. 2015. ‘Only as Good as Your Last Gig?’: An Exploratory Case Study of Reputational Risk Management amongst Self-Employed Musicians. Journal of Risk Research 18: 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, Taylor. 2024. Cognition, Interaction, and Creativity in Songwriting Sessions: Advancing a Distributed Dual-Process Framework. Social Psychology Quarterly 88: 01902725241266138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitch, Tal-Chen. 2020. The Potential of Music to Effect Social Change. Music & Science 3: 2059204320939772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnapala, Suri. 2023. Moral Capital and Commercial Society. The Independent Review: A Journal of Political Economy 8: 213–33. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24562686 (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Roy, William G., and Timothy J. Dowd. 2010. What Is Sociological about Music? Annual Review of Sociology 36: 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Hiro. 2011. An Actor-Network Theory of Cosmopolitanism. Sociological Theory 29: 124–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, Maggi, and Katherine Wimpenny. 2014. A Practical Guide to Arts-Related Research. Boston: SensePublishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrank, Sarah. 2014. Art and the City: Civic Imagination and Cultural Authority in Los Angeles. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Shamser, and Les Back. 2014. Making Methods Sociable: Dialogue, Ethics and Authorship in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research 14: 473–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintas, Jordi López, and Ercilia García Álvarez. 2002. Omnivores Show up Again: The Segmentation of Cultural Consumers in Spanish Social Space. European Sociological Review 18: 353–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, Rachel. 2017. Arts Alumni in Their Communities: 2017 SNAAP Annual Report. In SNAAP: Strategic National Arts Alumni Project. Bloomington: Center for Postsecondary Research Indiana University. Available online: https://snaaparts.org/uploads/downloads/Reports/SNAAP-Annual-Report-2017.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Skey, Michael. 2012. We Need to Talk about Cosmopolitanism: The Challenge of Studying Openness towards Other People. Cultural Sociology 6: 471–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/depaul/detail.action?docID=776766 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Small, Christopher. 2016. The Christopher Small Reader. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Catherine Parsons. 2007. Making Music in Los Angeles: Transforming the Popular. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, Martin. 2007. On Musical Cosmopolitanism. The Macalester International Roundtable 21: 8. Available online: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlrdtable/3 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP). 2011. Forks in the Road: The Many Paths of Arts Alumni. In SNAAP: Strategic National Arts Alumni Project. Bloomington: Center for Postsecondary Research, University of Indiana. Available online: https://snaaparts.org/uploads/downloads/Reports/SNAAP_2011_Report.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Tai, Yun. 2023. The Ties That Conform: Legitimacy and Innovation of Live Music Venues and Local Music Scenes. Poetics 100: 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, Anna. 2013. Key Factors Contributing to the International Success of a Rock Band: Managing Artists as Businesses. Helsinki: Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences. Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-2013121521252 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Umney, Charles, and Lefteris Kretsos. 2015. ‘That’s the Experience’: Passion, Work Precarity, and Life Transitions Among London Jazz Musicians. Work and Occupations 42: 313–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census. 2024. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: West Hollywood City, California. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/westhollywoodcitycalifornia/PST045224 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Vaag, Jonas, Fay Giæver, and Ottar Bjerkeset. 2014. Specific Demands and Resources in the Career of the Norwegian Freelance Musician. Arts & Health 6: 205–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, Mariana. 1994. Moral Capital. Canadian Journal of Law and Society 9: 213–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Stichele, Alexander, and Rudi Laermans. 2006. Cultural Participation in Flanders: Testing the Cultural Omnivore Thesis with Population Data. Poetics 34: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zijl, Anemone G. W., and An De Bisschop. 2023. Layers and Dynamics of Social Impact: Musicians’ Perspectives on Participatory Music Activities. Musicae Scientiae 28: 10298649231205553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Jane. 2003. Producing ‘Pride’ in West Hollywood: A Queer Cultural Capital for Queers with Cultural Capital. Sexualities 6: 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warde, Alan, David Wright, and Modesto Gayo-Cal. 2007. Understanding Cultural Omnivorousness: Or, the Myth of the Cultural Omnivore. Cultural Sociology 1: 143–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Allan, Michael Hoyler, and Christoph Mager. 2009. Spaces and Networks of Musical Creativity in the City. Geography Compass 3: 856–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, Christian, and Ronald Inglehart. 2005. Liberalism, Postmaterialism, and the Growth of Freedom. International Review of Sociology 15: 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, James, and Samuel Horlor, eds. 2022. Musical Spaces: Place, Performance, and Power. Singapore: Jenny Stanford Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, Ben, Greg Berger, and Jean-Christophe Gaillard. 2017. We’ve Seen the Future, and It’s Very Diverse: Beyond Gender and Disaster in West Hollywood, California. Gender, Place & Culture 24: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woronkowicz, Joanna, and Douglas S. Noonan. 2019. Who Goes Freelance? The Determinants of Self-Employment for Artists. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 43: 651–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, Seungil. 2020. The Relationship between Creative Industries and the Urban Economy in the USA. Creative Industries Journal 13: 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Qian, and Keith Negus. 2021. Stages, Platforms, Streams: The Economies and Industries of Live Music after Digitalization. Popular Music and Society 44: 539–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Gender | LGBTQ+ | Age | Marital Status | Children | Instrument-Discipline | Primary Genre | Arts Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jolene | Female | 81 | Divorced | Piano, Voice, Songwriter | Jazz | |||

| Carl | Male | ✓ | 30 | Single | Voice, Guitar, Songwriter | Pop/Rock | ✓ | |

| Peter | Male | 59 | Married | Acoustic + Electric Guitar | Instrumental Acoustic | ✓ | ||

| Benjamin | Male | 70 | Married | Bass Guitar, Composition | Progressive Rock | |||

| Nadia | Female | 32 | Single | Violin | Jazz | ✓ | ||

| Prince | Male/Female | ✓ | 31 | Single | Voice | Drag | ✓ | |

| Sage | Female | 44 | Married | Flute | Contemporary Classical | ✓ | ||

| Presley | Male | 44 | Married | Oboe, Conductor, Composition | Contemporary Classical | ✓ | ||

| Dylan | Male | ✓ | 29 | Partner | Voice, Piano | Pop/Rock | ✓ | |

| Johann | Male | ✓ | 29 | Single | Guitar, Piano, Composer | Pop/Rock | ✓ | |

| Mary | Female | ✓ | 27 | Single | Voice, Electric Guitar | Pop/Rock | ||

| Nelson | Male | 31 | Single | Electric Guitar, Composer | Rhythm + Blues | ✓ | ||

| Harmony | Female | ✓ | 32 | Single | Violin, Viola, Voice, Piano | Pop/Rock | ✓ | |

| Colton | Male | ✓ | 54 | Single | Voice, Piano | Jazz | ||

| Kamille | Female | 63 | Single | ✓ | Voice | Musical Theater | ✓ | |

| Messiah | Nonbinary | ✓ | 34 | Single | Voice, Piano, Songwriter | Pop | ||

| Sutton | Nonbinary Trans | 25 | Partner | Voice, Composition | Musical Theater | ✓ | ||

| Toby | Male | 61 | Married | ✓ | Piano, Composition | Jazz | ✓ | |

| Aria | Female | ✓ | 28 | Partner | Voice, Piano, Conducting | Collaborative Piano | ✓ | |

| Linus | Male | 48 | Married | ✓ | Double Bass, Electric Bass | Jazz | ✓ | |

| Donovan | Male | 62 | Married | ✓ | Guitar | Brazilian | ✓ | |

| Laurel | Female Trans | ✓ | 68 | Married | ✓ | Guitar, Piano, Conducting | Choral | ✓ |

| Eric | Male | ✓ | 36 | Married | Voice, Composition, Conducting | Choral | ✓ |

| Name | Files | References |

|---|---|---|

| ◯Audience | 13 | 20 |

| ◯Background | 21 | 63 |

| ◯Family Life | 10 | 13 |

| ◯Parents | 11 | 17 |

| ◯Challenges and Risks | 22 | 47 |

| ◯Commercial | 18 | 43 |

| ◯Connections | 12 | 25 |

| ◯Identity | 21 | 50 |

| ◯Instruments | 18 | 32 |

| ◯Leaving the Industry | 20 | 27 |

| Other | 20 | 48 |

| ◯Social Media | 9 | 19 |

| ◯Solidarity | 17 | 25 |

| ◯Songwriting | 3 | 3 |

| ◯Space | 22 | 90 |

| ◯Success | 23 | 65 |

| ◯Valued-Recognition | 20 | 31 |

| ◯Why Music | 19 | 33 |

| 2024 WeHo Music Venues | Year Built | Capacity * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Troubadour | 1957 | 500 |

| 2 | Whisky a Go Go | 1964 | 500 |

| 3 | The Roxy | 1973 | 500 |

| 4 | Viper Room | 1993 | 250 |

| 5 | Bar Lubitsch | 2006 | 100 |

| 6 | Peppermint Club | 2013 | 200 |

| 7 | Sun Rose | 2022 | 150 |

| 8 | Backbeat On Sunset (Hotel Ziggy) | 2022 | 300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagy, C.E. Melomaniacs: How Independent Musicians Influence West Hollywood’s Cosmopolitanism. Arts 2025, 14, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060133

Nagy CE. Melomaniacs: How Independent Musicians Influence West Hollywood’s Cosmopolitanism. Arts. 2025; 14(6):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060133

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagy, Caroline E. 2025. "Melomaniacs: How Independent Musicians Influence West Hollywood’s Cosmopolitanism" Arts 14, no. 6: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060133

APA StyleNagy, C. E. (2025). Melomaniacs: How Independent Musicians Influence West Hollywood’s Cosmopolitanism. Arts, 14(6), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060133