Abstract

The eighteenth century marked a peak period of globalization, during which Chinese porcelain emerged as a pivotal commodity in global material culture. This study focuses on a distinctive category, Chinese armorial porcelain, as a transcultural and hybridity artefact exchanged between High Qing China and Britain. Drawing on a multidisciplinary approach that combines close visual analysis with theoretical insights from material culture studies, postcolonial theory and consumer sociology, this study examines the evolving design language of these hybrid wares. It offers, for the first time, a systematic typology of Chinese decorative patterns on armorial porcelain and traces their compositional shifts over time. The analysis reveals a gradual Europeanization of these objects, corresponding to changing European perceptions of China—from a space of cultural fascination to a subordinated Orientalist otherness. At the same time, these porcelains register significant shifts in British social values, taste hierarchies, and consumption practices. Crucially, this study foregrounds the role of Chinese patterns, long treated as peripheral, as active agents in visual and cultural negotiation.

1. Introduction

The eighteenth century was a golden age of globalization (Farrell 2014, p. 2). The expansion of global trade led European countries to establish colonies worldwide, creating trade networks that spanned Africa, Asia, and South America (Abernethy 2000, p. 46). Trade between Europe and China was primarily conducted through the East India Companies (Chaudhuri 2006, pp. 15–18), and Chinese goods, particularly porcelain, became highly fashionable in Europe, with luxury items coveted by aristocrats and wealthy merchants (Berg 2007, p. 24).

In this study, the term armorial porcelain refers specifically to Jingdezhen-made export wares that were individually commissioned by European aristocratic or mercantile families and customized with their coats of arms. The origins of such wares can be traced to the early sixteenth century, when Portuguese patrons ordered porcelain from Chinese merchants across the Malacca Strait. A blue-and-white ewer made in Jingdezhen between 1505 and 1521, bearing the badge of King Manuel I of Portugal, survives as the earliest known example (Li 2017, p. 114). The trade in armorial porcelain subsequently expanded and reached its peak in the eighteenth century, when commissions multiplied in both number and variety, and the wares became central to the culture of elite display while also assuming a pivotal role in the material and visual exchanges between China and Europe. Accordingly, this study concentrates primarily on commissions produced during that period.

Unlike mass-market export porcelains, armorial porcelain wares were not anonymous commodities but bespoke luxury items that embodied both Chinese artisanal expertise and European heraldic identity (Denyer et al. 2024). Produced in Jingdezhen, they combined Chinese craftsmanship with European emblems (Li 2017, p. 114), resulting in a hybridized material form forged within a transcultural framework. European coats of arms were integrated into established Chinese decorative systems, creating objects that were simultaneously local in manufacture and global in symbolism. The high degree of personalization granted Chinese armorial porcelain a definitive position within the category of Chinese export wares (Yu 2011, pp. 223–36).

Current academic scholarship in the field predominantly focusses on European heraldic patterns, tends to position Chinese armorial porcelain as westernized (Howard 1974, 2003).1 However, despite their marginal positioning, Chinese patterns remain significant. As Michael Camille points out that marginal images are not merely secondary or decorative elements; they serve as critical reflections of the central themes of the artwork (Camille 1992, p. 38). These marginal images, though they may appear peripheral or chaotic, offer profound insights into the social, religious, and political structures of the time (Camille 1992, p. 43), challenging and reflecting the power dynamics and cultural context of society.

Building on a multidisciplinary approach that integrates visual analysis with theories from material culture, postcolonial studies, and consumer sociology, this study investigates the systematic typology of Chinese decorative patterns on eighteenth-century armorial porcelain and traces their evolving forms and shifting meanings over time. Through close examination of the spatial and compositional relationships between Chinese patterns and European coats of arms, the research traces how these hybrid objects both reflected and shaped the dynamics of cross-cultural exchange. The findings reveal a gradual transformation in European perceptions of China—from an initial fascination with cultural alterity, as embodied in exotic motifs and artisanal techniques, to a more instrumentalized Orientalist framing aligned with emerging Eurocentric ideologies. At the same time, the consumption and display of these objects in Europe, particularly Britain, indexed deeper social transformations concerning status, taste, and moral economy.

The discussion unfolds in three interrelated sections. First, it analyses the thematic motifs and visual logic of Chinese patterns on armorial porcelain, with a particular focus on comparing their stylistic presentation with those found on domestic Chinese porcelain. This section defines the distinctive esthetic transformations that Chinese patterns underwent when adapted for the British market. Second, it explores how changes in decorative schemes mirror broader shifts in European attitudes toward China, from admiration to hierarchical subordination. Third, it positions Chinese armorial porcelain within the shifting landscape of eighteenth-century British consumer culture, arguing that these wares reflected and shaped new ideals of class, taste, and moral order, as British society moved from aristocratic honour to the values of commercial civility and refined individuality.

2. Hybridity and Visual Syntax: The Reinterpretation of Chinese Patterns on Armorial Porcelain

The visual language of Chinese armorial porcelain is shaped through a complex interplay between Chinese decorative motifs and European heraldic emblems, producing a stylistic hybridity that is both deliberate and ideologically significant. This hybridity extends beyond mere ornamentation; it is embedded within a compositional syntax that conveys layers of meaning related to social status, cultural identity, and authority (Burke 2009, pp. 3–28). Crucially, the placement and relative prominence of Chinese patterns alongside European coats of arms provide key insights into the negotiation of visual hierarchy and cultural power on these objects. Therefore, establishing a clear typology of how Chinese and European motifs are positioned within armorial porcelain is essential for understanding their layered meanings and functions.

The typological analysis in this study is grounded in David Sanctuary Howard’s two authoritative catalogues of Chinese armorial porcelain (Howard 1974, 2003), which together document over 4000 services and remain the most comprehensive record of extant material. Howard’s database provides the chronological and heraldic framework for tracing the evolution of Chinese decorative patterns, linking patron identity with design choices, and supplying core visual references. To supplement this published corpus, direct object study was undertaken at the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum, allowing close examination of composition, brushwork, and pigment application. This selective, object-driven approach ensures that the typology rests on both authoritative catalogues and first-hand observation, while remaining focused on motifs most relevant to questions of hybridity and cultural negotiation.

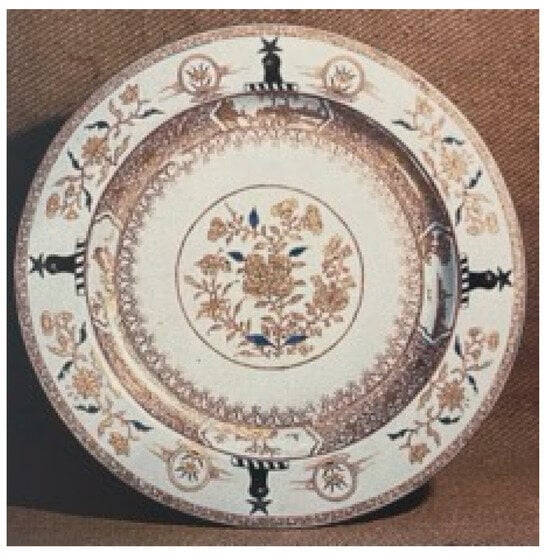

On the basis of this combined corpus, recurrent patterns of spatial organization emerge. The juxtaposition of heraldic devices with Chinese ornament was not random but followed identifiable compositional logics. These logics can be grouped into four primary positional types, each of which reflects different negotiations of visual hierarchy and cultural meaning. The first positions Chinese patterns as marginal decorations, framing the vessel’s rim, while European heraldic devices occupy the central focal point (Figure 1). In the second, the heraldic design is divided: shield motifs dominate the vessel’s centre, whereas crests are positioned on the outer rim, often surrounded or accented by Chinese elements (Figure 2). The third compositional type presents Chinese and heraldic motifs coexisting side by side within the central field, creating a dynamic visual dialogue between the two cultural languages (Figure 3). Finally, in the fourth position, Chinese decorative elements, such as birds, flowers, figures, or landscapes, increasingly claim the central scene, with European heraldry confined to peripheral zones like the rim (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

The first positions of Chinese patterns on armorial porcelain. A5 CUST, Baronet, impaling BROWNLOW. Yongzheng ca. 1725. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by David Sanctuary Howard (2003, p. 129).

Figure 2.

The second positions of Chinese patterns on armorial porcelain. D5 RUDGE quartering DELAFOSSE. Kangxi ca. 1720. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 147).

Figure 3.

The third positions of Chinese patterns on armorial porcelain. E4 MACRAE. Yongzheng ca. 1730. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 158).

Figure 4.

The fourth positions of Chinese patterns on armorial porcelain. A4 LETHIEULLIER. Yongzheng ca. 1725. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 126).

Among these configurations, this study finds that the range of Chinese patterns on armorial porcelain is remarkably diverse, with botanical and animal motifs emerging as the two most prominent types. To clarify their visual function and cultural significance, the following sections offer the first focused analysis of Chinese decorative typologies within armorial porcelain. By comparing these patterns with contemporaneous Chinese domestic porcelain, the discussion highlights how Chinese patterns were appropriated, transformed, and recontextualized for European consumers. Botanical and animal motifs offer a productive lens through which to trace their stylistic evolution and intercultural resonances across both Chinese and European decorative traditions in the eighteenth century.

This article focuses on seven motifs: chrysanthemum, peony, bamboo, rose, lotus, dragon, and phoenix, because botanical and animal clusters dominate the corpus. Notably, while landscape and bird motifs are also present on Chinese armorial porcelain, they most often appear in combination with floral ornament, forming integrated decorative ensembles. These categories are extensive and have been the subject of substantial scholarship (Ying 2021). Given the focus of the present study on the role of botanical and animal motifs as cross-cultural signifiers, landscapes and birds are acknowledged but not treated as primary objects of typological analysis. Their presence is discussed in relation to floral motifs where relevant, but a comprehensive treatment lies beyond the scope of this article.

2.1. Botanical Motifs on Chinese Armorial Porcelain

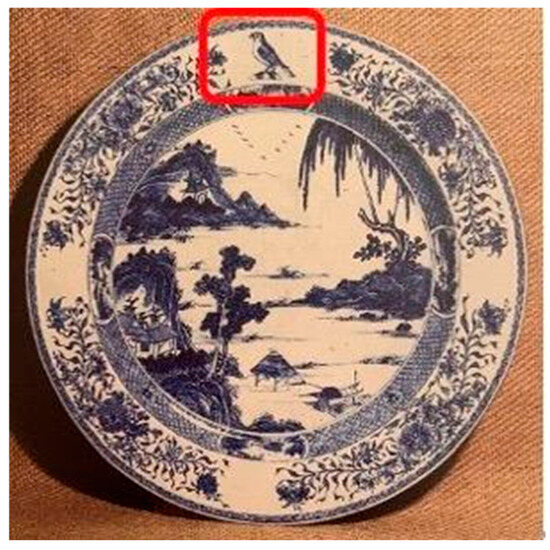

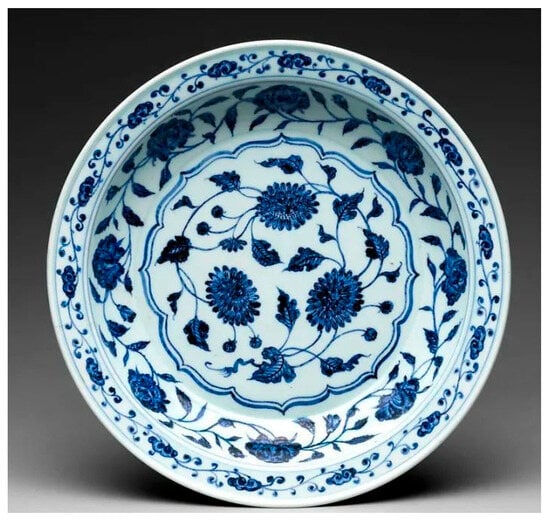

2.1.1. Chrysanthemum

The chrysanthemum motif stands out as one of the most frequently depicted botanical elements on Chinese armorial porcelain. Native to China and cultivated for over 3000 years, the chrysanthemum has a long history in Chinese decorative arts (Long et al. 2015, pp. 212–13). In Chinese porcelain, chrysanthemums typically appear in scrolling floral designs. This type of composition, characterized by intertwined vines and symmetrically arranged blossoms, is a longstanding tradition. For instance, a late Ming blue-and-white plate features a central floral medallion surrounded by scrolling chrysanthemum vines. The motif is fluid and dynamic, with gracefully extended branches and leaves, creating a sense of movement rather than a static, rigid pattern (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Plate with chrysanthemums and peonies, ca. 1368–1644. Diam. 14 7/8 in. (37.8 cm). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York.

Additionally, the integration of chrysanthemum motifs with other decorative elements reflects long-standing traditions in Chinese porcelain painting. For example, the dynamic S-shaped arrangement of chrysanthemums and bamboo on a plate produced for export (Figure 6) exemplifies a meandering border composition that was especially popular among European consumers. Such designs echo the symbolic esthetics of the “Four Gentlemen of Flowers” (mei, lan, zhu, and ju) in Chinese painting, in which the chrysanthemum represents restraint, solitude, and integrity (M. Zhang 2020, p. 135).

Figure 6.

Blue-and-white export porcelain plate. Housed at the Museum of Applied Arts, Leipzig, Germany. Kangxi ca. 1622–1722. Image source from Asian Ceramics in the Saxon Court and the Firing of European Hard-Paste Porcelain 萨克森宫廷藏亚洲陶瓷及欧洲硬质瓷的烧制, by Ruoming Wu 吴若明 (Wu 2021, p. 109).

A comparable example can be seen in Figure 7, an eighteenth-century Chinese armorial porcelain plate commissioned by the Boone family. Similarly to the Chinese domestic porcelain (Figure 5), the Boone plate employs blue-and-white underglaze painting, layered border decoration, and a scrolling floral pattern that integrates chrysanthemums. The composition maintains a sense of balance and visual harmony, with floral elements arranged to ensure esthetically pleasing symmetry. Notably, the chrysanthemum vines adopt a dynamic S-shaped configuration, an arrangement frequently used in Chinese porcelain to create a sense of movement and liveliness. Despite these similarities, the armorial porcelain version incorporates European heraldic elements, with the chrysanthemum branches and leaves at the centre and edges being more luxuriant. Additionally, the arrangement of decorative elements on the Boone plate creates a greater sense of three-dimensionality, further distinguishing it from traditional Chinese domestic porcelain. The dynamic S-curve scrolls were not only inherited conventions. Chinese workshop painters might use them as adjustable armatures to “stage” heraldic charges, thickening or thinning vine runs to open clear reserves for shields and crests, and to keep the visual weight balanced across the plate. This compositional tuning points to an artisan-led management of space.

Figure 7.

Chinese armorial porcelain plate. A2 BOONE. Kangxi ca. 1718. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 125).

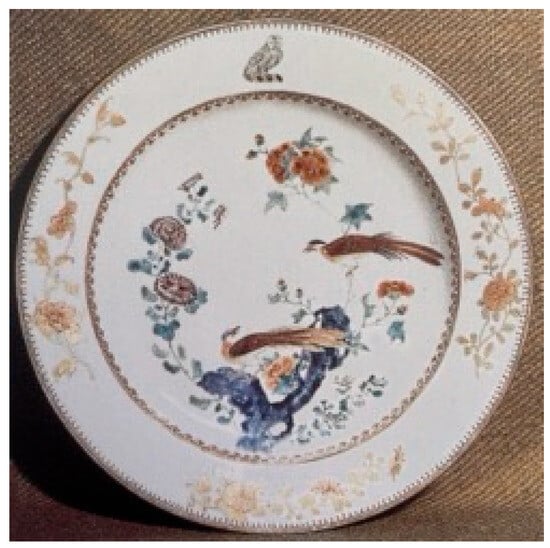

Furthermore, this study also identifies resonances between the floral decoration of Chinese armorial porcelain and that of contemporary English-made porcelains. A notable comparison can be drawn between a Chinese armorial plate customized for the Barton or Massey family (Figure 8) and a product from the Chelsea Porcelain Factory (Figure 9). The Chelsea plate features a moulded lobed edge with engine-turned decoration, painted with exotic birds and butterflies on a turquoise feathery border, with sprays of flowers on the rim and a gilt edge. This floral and avian decoration style was evidently a favoured theme among European consumers of the time.

Figure 8.

Chinese armorial porcelain plate. K5 BARTON, MASSEY or another. Qianlong ca. 1745. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 220).

Figure 9.

European porcelain plate made in Chelsea (London). Ca. 1759–1760. Diameter: 8.70 inches. © The Trustees of the British Museum. London.

Notably, in both the Chelsea plate and the Chinese armorial porcelain, the birds are depicted facing each other, creating a sense of interaction. Additionally, the rims of both plates incorporate gilt decoration, an element particularly favoured by European consumers to enhance their luxurious appeal. At the same time, the chrysanthemum’s appearance in Chinese porcelain aligns with parallel developments in European ceramics, such as Meissen’s appropriation and reinterpretation of Chinese floral borders. The well-known Meissen “Onion Pattern” (Figure 10) incorporates stylized chrysanthemum blooms both centrally and peripherally, integrating them into a Rococo-inflected decorative vocabulary. These visual and material adaptations illustrate a process of cultural hybridization, whereby Chinese floral iconography was neither passively copied nor entirely transformed, but strategically recontextualized. The chrysanthemum motif thus functions as a dynamic cultural signifier, capable of traversing esthetic boundaries while retaining its exotic and symbolic value within an increasingly globalized porcelain trade.

Figure 10.

Meissen Blue-and-White onion pattern porcelain plate. Housed at the German Ceramics Museum. Yongzheng ca. 1730. Image source from Asian Ceramics by Wu (2021, p. 109).

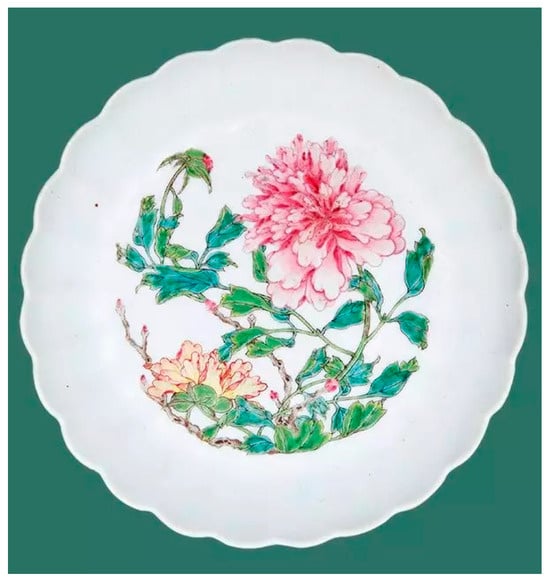

2.1.2. Peony

In traditional Chinese culture, the peony (mu dan) is revered as the “King of Flowers”, admired not only for its sumptuous and elegant appearance but also for its rich symbolic resonance as an emblem of prosperity, power, and imperial grandeur (Chiem 2018, p. 388). Since the Sui and Tang dynasties, the peony motif frequently appeared on porcelains produced for the imperial court (Deng 1989). A famille-rose plate from the Yongzheng period (1723–1735) (Figure 11) illustrates this tradition: the peony, rendered in full bloom at the centre of the composition, is combined with pheasants and ornamental rocks, together signifying auspiciousness, longevity, and prosperity. Here, the flower functions as a visual and ideological focal point, embodying the luxurious esthetics and symbolic density typical of imperial porcelain.

Figure 11.

Peony pattern plate. Yongzheng ca. 1723–1735. © The Palace Museum, Beijing, China.

By contrast, the reception of the peony in eighteenth-century Europe entailed a significant reconfiguration. Naturalists such as Sir Joseph Banks introduced Paeonia suffruticosa (tree peony) to Britain, while Paeonia lactiflora (herbaceous peony) soon became a popular garden plant. Under the Linnaean system of taxonomy, however, the long-standing Chinese distinction between shao yao (herbaceous peony) and mu dan (tree peony) was collapsed into a single genus, Paeonia. This epistemological unification effectively effaced the plant’s differentiated meanings in Chinese botanical, medical, and symbolic traditions, reframing it in Europe as an esthetically exotic but semantically neutral flower (R. Zhang 2021, pp. 49–50). As Richard Zhang has observed, “The mu dan did not retain its kingly status at Kew Gardens, nor did shao yao become a common subject of Neoclassical or Romantic paintings (R. Zhang 2021, p. 50).” In Europe, the peony was thus reinterpreted less as a culturally saturated emblem than as an ornamental curiosity. This process may be understood in terms of “culturally induced ignorance,” whereby selective translation and epistemic disjuncture stripped away the symbolic agency of the flower while preserving its visual appeal.

The same shift toward ornamental neutrality is observable in Chinese armorial porcelain. On early eighteenth-century commissions such as a plate for the Bates family (Figure 12), peonies appear frequently but occupy marginal positions, forming clustered border patterns interspersed with smaller buds to create fullness and rhythm. The heraldic crest, by contrast, invariably dominates the centre. This compositional hierarchy reflects the cultural logic of European decorative systems: symbols of lineage and authority are accorded centrality, while foreign motifs are relegated to the periphery. In adapting to these demands, Jingdezhen decorators did not simply replicate traditional conventions but actively modified them. The adoption of famille-rose enamels enabled fuller petals, gilded highlights, and clearer separations between dense floral clusters and heraldic crests (Clunas 2004; Wu 2021). These workshop strategies preserved the ornamental rhythm of Chinese design while safeguarding the legibility of European arms, exemplifying the esthetic negotiation inherent in cross-cultural artistic production.

Figure 12.

Chinese armorial porcelain. D4 BATES or BATE. Yongzheng ca. 1730. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 143).

Comparative examples further clarify this transformation. In Chinese imperial porcelains of the Yongzheng period, peonies retained their central, ideologically charged position. By contrast, a mid-eighteenth-century plate from the Chelsea manufactory in Britain (Figure 13) placed the peony at the centre in imitation of Chinese prototypes but rendered it in a simplified manner with few surrounding elements. In the nineteenth century, this plate was repainted, and its background overlaid with gold. While gold was rarely used in Chinese porcelains due to its association with imperial exclusivity, in European decorative traditions it symbolized wealth and refinement. This act of repainting marked a redefinition of cultural identity: what once served as a display piece in the “Chinese style” was transformed into an object aligned with European decorative values.

Figure 13.

Chelsea Porcelain Factory (manufacturer). Fruit Dish. Mid 18th century (made), first half of 19th century (repainted). Diameter: 18.1 cm. © The V&A Museum, London.

Taken together, these examples trace the shifting trajectory of the peony motif across Chinese domestic porcelain, European chinoiserie, and Chinese armorial wares. In the Chinese imperial context, the peony was a bearer of layered symbolic meanings tied to authority and prosperity. In European chinoiserie, it was admired as an exotic marker of “Chineseness,” yet stripped of its deeper cultural resonances. On Chinese armorial porcelain, the peony was subordinated to heraldic crests and transformed into a decorative border motif. Across these contexts, what endured was the flower’s esthetic presence; what was diminished was its cultural voice. The peony’s visual transmission thus exemplifies how cross-cultural exchange could generate not only hybrid forms but also processes of symbolic loss and reconfiguration.

2.1.3. Bamboo

Bamboo is a recurring decorative motif in Chinese armorial porcelain, though less common than chrysanthemums or peonies, it became a familiar element in margin decoration during the late eighteenth century. As the native habitat of the world’s richest bamboo biodiversity, China cultivated what scholars have called a distinctive “bamboo civilization” (Yun 2014, pp. 8–10). By the Qing dynasty, especially under the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors, bamboo had become an established and highly symbolic motif in porcelain decoration. It appeared not merely as a background element but often as the central subject. A covered jar inscribed Da Qing Kangxi Nian Zhi exemplifies this tradition (Figure 14). Its surface is segmented by raised lines that echo bamboo’s nodal structure, while its lid is shaped as a bamboo stalk segment. Painted in overglaze enamels, the lid presents a floral arrangement of red and yellow chrysanthemums set against soft green leaves, with beaded edges further accentuating the symbolic elegance of the design.

Figure 14.

Doucai 斗彩 bamboo pattern bamboo jointed lid jar. Kangxi ca. 1662–1722. Overall H. 16.7 cm, rim D. 4.2 cm, foot D. 11.7 cm. © The Palace Museum, Beijing, China.

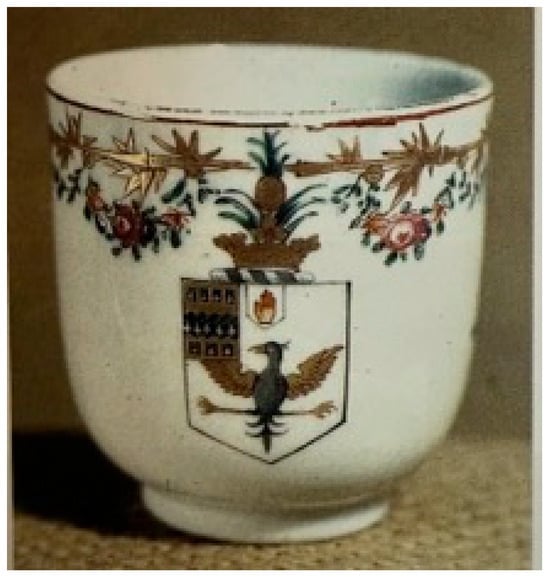

By contrast, bamboo motifs on eighteenth-century Chinese armorial porcelain were increasingly hybridized. Rather than preserving their upright form and literati associations, they were adapted to harmonize with European floral idioms. A teacup commissioned by the Parkyns family of Bunny Hall around 1730 illustrates this shift (Figure 15). Here, bamboo is no longer depicted as a vertical stalk but reoriented into a horizontal border motif encircling the rim. Interspersed with roses and other blossoms, the motif functions less as a naturalistic image than as a framing device. Its transformation dissolves bamboo’s traditional role as a symbol of integrity and resilience, repurposing it within a decorative schema shaped by European taste. Small, star-shaped leaves and curling tendrils extend from the bamboo lattice, merging with Rococo-inspired florals and softening the overall composition. At the centre, the heraldic crest—a black eagle in formal pose, reasserts the object’s commissioned identity, visually balancing lineage and exoticism within a single design.

Figure 15.

Chinese armorial cup N5 PARKYNS, Baronets. Yongzheng ca. 1730. Chinese armorial porcelain plate. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 262).

Bamboo, in this transcultural context performed a dual function. Esthetically, it appealed to European patrons for its refinement and exotic character. Symbolically, it retained residual meanings rooted in Chinese culture, such as integrity, humility, and resilience, even if these associations were not fully recognized by its European audience. Its reorientation from vertical stalk to horizontal lattice should therefore be read not simply as stylistic adaptation but as deliberate reframing by Jingdezhen decorators who created a continuous rim architecture capable of cradling European crests without disturbing the central field.

Thus, bamboo on armorial porcelain operated as a visual intermediary. Even when its symbolism was diluted or recontextualized, it remained a conduit for indirect cultural encounter, embedding traces of Chinese artistic values within a form calibrated for European decorative expectations. This negotiation underscores the broader processes of cultural translation in which motifs were transformed yet never entirely detached from their original significance.

2.1.4. Rose

In European visual culture, the rose occupies a privileged symbolic position. Rich with layered meanings, it embodies life, passion, love, wisdom, and beauty. In classical mythology, the rose is closely associated with Venus, the goddess of love, and is often regarded as a sacred gift, surrounded by an aura of divine and sensual allure. In Christian iconography, it can represent both purity and martyrdom, depending on the context. Beyond its religious connotations, the rose also holds secular symbolic weight, used in courtly rituals and public ceremonies to express joy, grief, honour, or political authority. It appears frequently in national symbolism: several European countries have adopted the rose as an emblem of national identity, often incorporating it into royal heraldry as a mark of dynastic legitimacy and noble lineage (Z. Liu 2013, p. 23).

This exalted status stands in stark contrast to the rose’s position within traditional Chinese cultural frameworks. In The Classic of Flowers (Hua jing 花经), a seminal tenth-century treatise by Southern Tang literatus Zhang Yi (942–993), flowers were systematically ranked according to their esthetic and moral value. Orchids, peonies, and wintersweet (lamei) were classified as “first-class noble flowers,” admired for their elegance and symbolic purity. The rose, however, was placed in the seventh tier, grouped alongside camellias and winter jasmine (ying chun) (Guo and Wen 2019). While The Floral Canon did not function as an official taxonomy, it profoundly influenced Chinese floral esthetics and literati tastes. Consequently, rose motifs rarely appeared in Chinese domestic porcelain, which favoured more culturally prestigious flowers such as the peony or chrysanthemum.

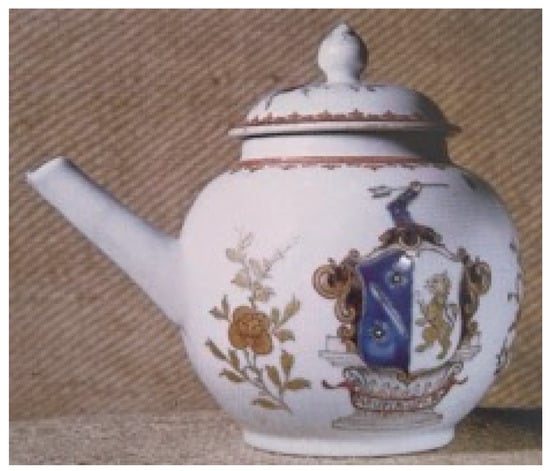

The contrast becomes especially striking in Chinese armorial porcelain made for European patrons. Here, the rose emerges as a prominent decorative element, valued not for its position in Chinese tradition but for its powerful resonance within European symbolic systems. A representative example is the teapot bearing the arms of Auchmuty impaling, dated to around 1750 (Figure 16). On this vessel, a rose motif is delicately outlined in gold and positioned adjacent to the heraldic crest. The combination of gilding and strategic placement demonstrates how European symbolic priorities were actively inscribed onto a Chinese decorative programme. Rather than a passive adoption of Chinese floral conventions, this arrangement reflects an intentional negotiation between Jingdezhen decorators and European patrons, resulting in a hybrid design that fused Chinese craftsmanship with European heraldic and cultural values.

Figure 16.

Chinese armorial teapot. P16 AUCHMUTY impaling. Qianlong ca. 1750. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 310).

In sum, the rose motif on Chinese armorial porcelain highlights the asymmetry of cultural translation. While in China the rose remained a marginal flower of limited symbolic standing, in Europe it was invested with dense mythological, religious, and political meanings. Its integration into armorial porcelain underscores how European symbolic hierarchies were projected onto Chinese media, producing hybrid objects where local craftsmanship and foreign cultural systems intersected.

2.1.5. Lotus

The lotus motif, long revered in Chinese art for its associations with purity, spiritual transcendence, and resilience, particularly within Buddhist and literati traditions (Zhang and Liu 2009, pp. 101–2), underwent a notable transformation in the decorative repertoire of eighteenth-century Chinese armorial porcelain. This process of semantic reframing reflected the demands and esthetic sensibilities of European patrons, who often engaged with Chinese motifs through their own cultural and visual lexicons.

A striking example is found in a Chinese armorial porcelain plate commissioned by the Davies family circa 1730 (Figure 17). The rim of the plate is decorated with four evenly spaced lotus clusters, each enclosed within circular medallions and surrounded by a band of chrysanthemums, while the central field features a dominant peony composition. In this configuration, the lotus no longer functions as a bearer of indigenous metaphysical significance but is reduced to a structurally ornamental role. The circular cartouches that enclose each lotus cluster also reflect a workshop practice of creating stable, repeated reserves. This stabilized the rhythm of the rim decoration and provided decorators with predictable clearances for heraldic scaling in the centre. At the same time, the medallion framing recalls the ornamental cartouches common in Rococo architecture, suggesting a European-inflected spatial logic that emphasized symmetry, containment, and decorative hierarchy over symbolic resonance.

Figure 17.

Chinese armorial porcelain plate. D9 DAVIS. Yongzheng ca. 1730. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 149).

This formal adaptation was accompanied by a cognitive recoding of the motif. To European viewers unfamiliar with the indigenous meanings of the lotus, the flower was often interpreted through analogies with familiar symbols, particularly the Marian lily (Stott 1992). Lilies had been cultivated in Britain since the early seventeenth century and, like the lotus, they were associated with purity while also symbolizing royal authority (Zilen 2017, p. 3). Their primary significance, however, was religious (Zilen 2017, p. 3). For instance, in Jan Brueghel’s Madonna in a Garland of Flowers (Figure 18), lilies appear prominently alongside other blossoms. The painting, commissioned by Cardinal Federico Borromeo, a noted collector and Catholic reformer, was intended to reinforce the image of the Virgin Mary during the post-Tridentine renewal of Catholic devotion (Zilen 2017, p. 4). In this light, the lotus was not only decontextualized but also reinscribed within a Christianized framework of moral symbolism. Such reinterpretations echoed the epistemic substitution practices evident in early modern botanical herbaria, where foreign flora was systematically classified according to European taxonomic categories rather than understood within their indigenous systems of meaning.

Figure 18.

Madonna in a Garland of Flowers. Peter Paul Rubens. Ca. 1616–1618. 185 × 210 cm. © Alte Pinakothek, München, Germany.

The spatial logic of the plate’s design further underscores this cultural negotiation. The lotus, positioned in the liminal zone of the rim and bound within strict geometric borders, contrasts with the freer, more expressive peonies at the centre. This visual hierarchy materializes a gradient of cross-cultural legibility: the central space accommodates a synthesis of Chinese and European florals, while the margins become sites of symbolic displacement, where traditional Chinese motifs are formalized, reframed, and subordinated to European esthetic order.

Ultimately, the presence of lotus motifs on Chinese armorial porcelain exemplifies how European consumers selectively appropriated and redefined Chinese iconography, transforming it into a visually exotic but semantically neutral pattern. The lotus thus ceased to function as a symbol of spiritual enlightenment and became part of a broader ornamental vocabulary tailored to Western tastes and cultural expectations.

2.2. Animal Motifs on Chinese Armorial Porcelain

2.2.1. Dragon

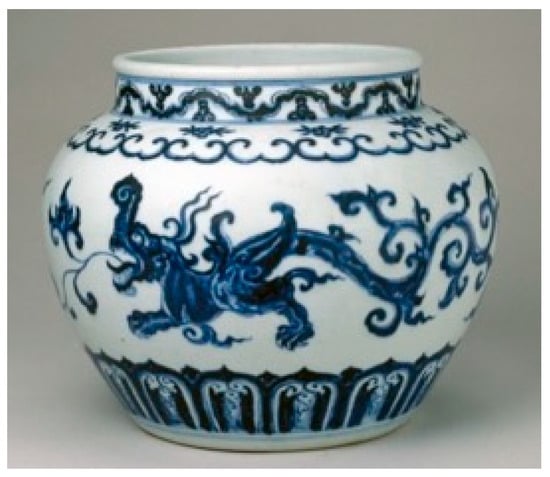

The dragon has long held a preeminent place in Chinese visual culture, its image evolving across dynasties to reflect shifting hierarchies of political power and cosmological thought (Welch 2008, p. 136). During the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), the five-clawed, horned dragon was strictly reserved for the emperor, referred to as the “True Dragon Son of Heaven”, while four-clawed variants signified lesser nobility (Wilson 1990, pp. 286–323). This codified hierarchy persisted through the Ming and Qing periods, underscoring the dragon’s exclusive association with imperial authority and celestial legitimacy.

Esthetically, the dragon’s elongated, serpentine body rendered it especially well-suited to porcelain decoration (Hugo 2011, p. 142). It could wrap dynamically around the contours of vessels—plates, bowls, jars, creating a fluid interplay between image and object. A celebrated example is a blue-and-white dragon jar attributed to the Xuande reign (1426–1435), now in the Palace Museum in Beijing (Figure 19). Here, the dragon’s coiling form is animated by expressive brushwork, its sinuous body emerging from auspicious cloud scrolls, framed by ruyi-head and lotus petal borders. The resulting composition achieves a visual rhythm that balances tension with harmony, encapsulating both artistic virtuosity and cosmological symbolism.

Figure 19.

Blue and white porcelain jar with dragon pattern. Xuande ca. 1426–1435. © The Palace Museum, Beijing, China.

When the dragon motif entered the realm of Chinese armorial porcelain made for European patrons, its semantic charge shifted. By the eighteenth century, Enlightenment rationalism had begun to reshape European cosmologies, and dragons were increasingly understood not as real or fearsome creatures, but as mythical symbols of natural forces, mysterious, powerful, but no longer demonic (Senter et al. 2016). Unlike the rigid claw-counting imperial taxonomy in China, European representations often featured dragons with four or indeterminate numbers of claws, suggesting a decoupling from original iconographic restrictions.

Crucially, the dragon’s visual affinity with the Rococo esthetic—a style defined by asymmetry, curvilinear forms, and kinetic surface ornament—amplified its appeal to European consumers. The swirling movement of Chinese dragons found unexpected resonance with the arabesques and S-curves of Rococo interiors. The streamline of the dragon’s body, thinned and elongated, can be read as a painterly choice that not only preserved Rococo-like movement but also carefully steered the coils away from armorial motto scrolls and quarterings. Such adjustments reveal the adaptability of Jingdezhen decorators, who subtly modified the motif to accommodate heraldic clarity while sustaining its ornamental vitality.

An example commissioned by a British patron (Figure 2) features a four-clawed dragon encircling a central heraldic device. Here, the dragon is largely stripped of its cosmological meaning and functions primarily as a decorative flourish, an ornamental emblem of the exotic that simultaneously conveyed status, worldliness, and refined taste. In this transcultural context, the dragon motif operated as a site of visual negotiation. While its symbolic density in Chinese tradition was attenuated, it nevertheless retained a trace of its original power, now reframed through the lens of European esthetics. The dragon on armorial porcelain thus exemplifies how visual forms could traverse cultural boundaries, shed some meanings while acquiring new ones, serving, ultimately, as agents of esthetic hybridity in the global circuits of eighteenth-century luxury.

2.2.2. Phoenix

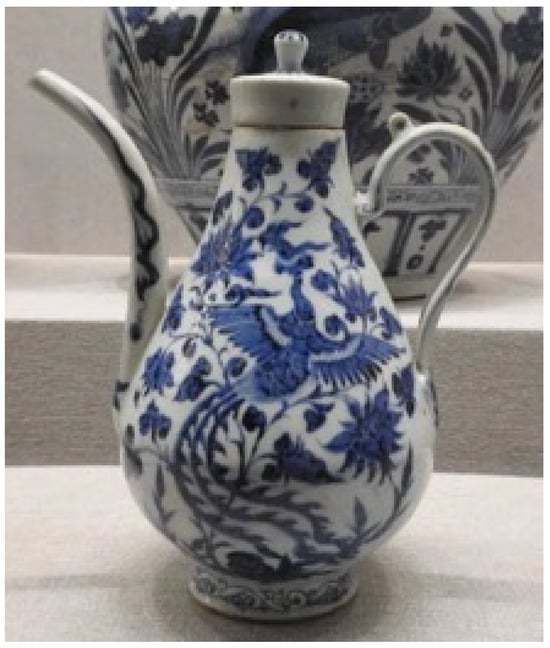

The phoenix motif has long occupied a significant place in the decorative lexicon of Chinese porcelain. Its earliest ceramic renderings can be traced to the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), where it frequently appeared in underglaze blue compositions. A Yuan-period ewer (Figure 20) offers a representative example, depicting a phoenix in mid-ascent, encircled by trailing floral and foliate motifs. The upward movement of the bird, paired with its botanical surroundings, evokes vitality, harmony with nature, and an idealized esthetic of grace, qualities traditionally associated with the fenghuang, the Chinese phoenix, which symbolized not only beauty but also imperial virtue and cosmic order (Hill 1984).

Figure 20.

Blue-and-white Ewer with Phoenixes among Lotus. Yuan Dynasty ca. 1271–1368. © The Palace Museum, Beijing, China.

During the Ming dynasty, the phoenix became increasingly codified as a motif of auspicious imperial significance (S. Liu 2023). It featured prominently in porcelains produced by official kilns, often commissioned for palace use or elite gifting. In contrast, the phoenix underwent a conceptual transformation in European contexts. While Renaissance Europe associated the phoenix with themes of resurrection and immortality, by the eighteenth century (Valerie 2013). The bird was increasingly interpreted not through complex theological or mythic frameworks, but as a metaphor for rarity, singularity, or exceptionality (Marder 2023). This semantic narrowing coincided with the rise of consumer culture and the commodification of uniqueness, which helps to explain its appeal in the decorative programmes of Chinese armorial porcelain.

Indeed, European patrons selectively adopted the phoenix motif not for its original Chinese or classical meanings, but for its perceived exoticism and capacity to signify exclusivity. In the realm of Chinese export porcelain, the phoenix became a means of visual distinction, a mark of rarity that conferred symbolic prestige upon the object and its owner. As Edward Harrison notes, an armorial service featuring the phoenix as marginal decoration (Figure 21) exemplifies this dynamic: the bird, while relegated to the decorative border, nonetheless plays a critical role in enhancing the aura of refinement and rarity surrounding the porcelain.

Figure 21.

Chinese armorial porcelain plate from Edward Harrison. Kangxi ca. 1718. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 126).

Thus, the phoenix motif on Chinese armorial porcelain operated at the intersection of two divergent symbolic systems. In Chinese tradition, it carried layered cosmological and political meanings; in its European reception, it was reimagined as an ornamental cypher of distinction. This cross-cultural reframing exemplifies the processes of transculturation at work in eighteenth-century material culture, where motifs were not merely transmitted but transformed, inflected with new meanings to accommodate different esthetic logics and ideological frameworks.

In summary, the Chinese patterns on armorial porcelain reveal a nuanced process of cultural adaptation and reinterpretation. Motifs such as chrysanthemum, peony, bamboo, lotus, dragon, and phoenix retained core elements of their Chinese symbolic meanings while being reshaped to meet European esthetic preferences and social functions. This interplay produced a hybrid visual language that simultaneously expressed exotic appeal and signalled status within eighteenth-century European elite culture. However, these stylistic and symbolic transformations cannot be fully understood without considering the broader cultural context in which European perceptions of China were evolving.

To deepen this understanding, it is essential to examine how eighteenth-century European fascination with the Orient informed and refracted the changing forms and meanings of Chinese decoration on armorial porcelain. The following sections explore this dynamic through the frameworks of alterity and Orientalism, demonstrating how the visual shifts in Chinese motifs not only reflect artistic hybridity but also reveal underlying shifts in European cultural identity and power relations. This approach situates the evolution of Chinese patterning within the broader discourse of eighteenth-century European engagements with ‘the Other’ and the construction of selfhood through material culture.

3. From Cultural Fascination to Orientalist Distance: Alterity and the Shifting Perception of China

In the eighteenth century, Chinese armorial porcelain was not only a luxury good but also a material embodiment of European cultural fascination with the Orient and its obsession with exoticism. As a cultural adjective, the term “exoticism” in the eighteenth century was largely confined to foreign flowers, plants, or rare imported goods. When viewed as a cultural phenomenon, however, exoticism was more related to individual emotions or feelings, specifically, the psychological state and atmosphere experienced by Western subjects as they encountered foreign cultures, which experience went beyond the specific objects of foreign origin (Rousseau and Porter 1990, pp. 146–47).

This section will discuss the general evolution of Chinese pattern on armorial porcelain through the concept of Mikhail Bakhtin’s alterity, and Edward W. Said’s ‘oriental other’, to reveals a shift in European perceptions of China, from an initial embrace and admiration rooted in Bakhtin’s concept of alterity, to a later repositioning of China as the ‘oriental other’, a subordinate cultural foil that served to elevate Europe’s own self-constructed identity and superiority during the period of growing Eurocentric dominance.

3.1. Alterity and Orientalism

The eighteenth-century European fascination with the Orient, particularly China, was closely tied to the binary opposition between the “self” and the “other” (Rousseau and Porter 1990, pp. 146–47). Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of alterity provides a critical lens for understanding the cultural dynamics of eighteenth-century armorial porcelain. For Bakhtin, alterity is not merely exclusion but a separation that serves as a prerequisite for dialogue (Ashcroft et al. 2013, pp. 12–13). Chinese armorial porcelain exemplifies this dialogic relationship: commissioned wares bearing European heraldry on Chinese decorative frameworks reveal how the European “Self” defined itself in relation to a culturally distinct Chinese “Other.” While patrons attempted to assert dominance through heraldic inscriptions, the material properties of porcelain, such as the translucency of its glazes and the refinement of kaolin, resisted full appropriation and preserved a sense of irreducible difference.

Unlike Bakhtin’s concept of alterity, Edward Said introduced the concept of ‘Orientalism’. According to Said, ‘Orientalism’ functions as a mode of thought that constructs a binary opposition between the East and the West, serving as a means for the West to control, reconstruct, and dominate the East (Said 2003, pp. 2–3). In the later eighteenth century, as Enlightenment confidence and industrial modernity grew, this discourse reframed China from an admired civilization into a stagnant empire (Muthu 1999, pp. 985–87). Although fully elaborated in the nineteenth century, traces of this shift are already evident in the visual logic of armorial porcelain, where Chinese motifs were gradually marginalized or reframed within European decorative hierarchies.

Together, these frameworks highlight not an abstract theoretical exercise but the concrete ways in which decorative motifs on porcelain registered changing perceptions of China, at once dialogic and hierarchical. The typological analysis outlined above provides the material basis for this ideological interpretation. In early services, dense chrysanthemum borders or bamboo lattices framed heraldry, staging the European crest within a Chinese ornamental system that embodied dialogic alterity. By the late eighteenth century, however, these motifs were displaced to thin fillets at the rim, replaced by European roses, or omitted altogether. Dragons and phoenixes were streamlined or confined to margins. Such displacement and simplification parallel the Orientalist reframing of China, in which Chinese motifs lost their centrality and became peripheral embellishment. In this way, the ideological transition from alterity to hierarchy can be read directly in the shifting visual logic of armorial porcelain.

3.2. The Evolution of Chinese Pattern on Armorial Porcelain

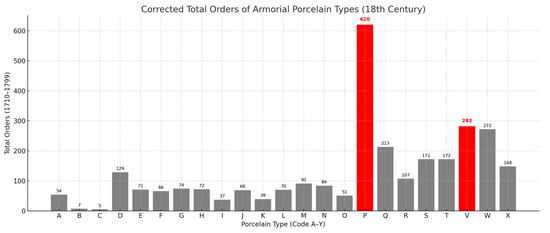

By examining the classification of eighteenth-century armorial porcelain styles in David Howard’s findings (Howard 1974, 2003), a comparative analysis reveals that the decorative style of Chinese armorial porcelain underwent gradual changes during the eighteenth century. A striking example of this transition can be observed in the most frequently commissioned styles, P and V. The high volume of commissions for both style P and style V indicates their popularity (Figure 22).

Figure 22.

An analysis of Chinese armorial’s styles and their dates. Based on Howard’s data, created by the author.

In style P (1735–1775), Chinese patterns appeared along the margins of the porcelain, preserving an element of exoticism. However, by style V (1770–1805), the design had increasingly Europeanized, with Chinese patterns in armorial porcelain gradually disappearing over the years (Figure 23). The transition from Style P to Style V, as catalogued by David Howard, demonstrates not only the numerical decline of Chinese motifs but also a process of motif displacement. In earlier Style P examples, Chinese elements occupy the rim or margins, functioning as a visual frame to heraldic crests. By the late eighteenth century, however, Style V porcelains reveal a progressive re-scaling and simplification of Chinese decoration, where floral or animal motifs are reduced in size, attenuated in detail, and in many cases eliminated altogether. This visual process resonates with Enlightenment rationalism and the epistemological drive for order and clarity, where ornamental excess was increasingly disciplined into controlled, symmetrical schemes. It also aligns with Orientalist discourse, which redefined China not as a partner in cultural dialogue but as a decorative supplement to be subordinated within European esthetic hierarchies.

Figure 23.

Style of P, Chinese armorial porcelain plate with the crest of CRAWFURD. Qianlong ca.1740 (left). Style of V, Chinese armorial porcelain bearing the coat of arms of Dalton accollé Gage quartering Rookwood. Qianlong ca. 1785 (right).

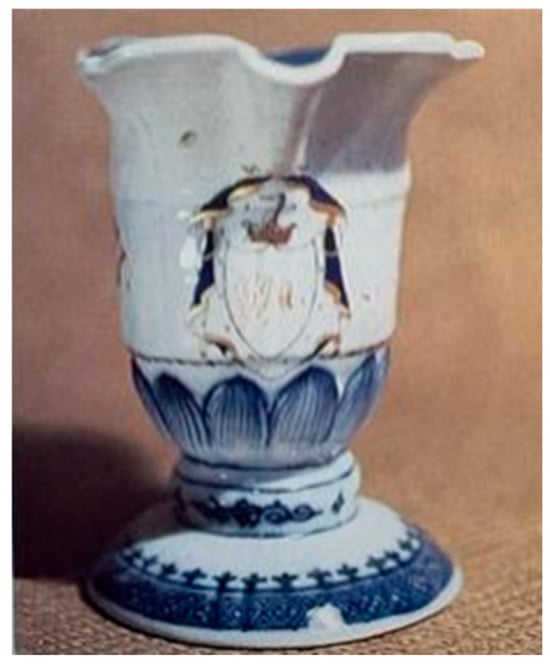

Furthermore, it is significant to note that the morphologies of Chinese armorial porcelain underwent notable transformation over the course of the eighteenth century. This study finds that during the earlier decades of the century, European patrons predominantly commissioned porcelain plates, which provided an expansive surface for the display of exotic Chinese decorative patterns. However, by the latter part of the eighteenth century, as the vogue for chinoiserie began to wane, the morphological typology of armorial porcelain shifted from ornamental display wares to more utilitarian forms. Increasingly, commissions included functional items such as tea sets, bowls, tureens, milk jugs, and fruit baskets.

Crucially, many of these later pieces were no longer based on traditional Chinese vessel forms but instead reflected adaptations to suit European domestic practices and esthetic preferences (Figure 24). This morphological evolution, coupled with the gradual marginalization of Chinese decorative motifs, signals a transformation from a commissioned luxury object to a practical commodity integrated into the rhythms of European daily life. Moreover, when considered in tandem with the fading of Chinese motifs, these morphological adaptations further exemplify a symbolic subordination of Chinese design. Decorative elements once central to the visual identity of armorial porcelain were relegated to peripheral zones or disappeared entirely, reinforcing Europe’s self-perception as the dominant arbiter of taste and cultural order.

Figure 24.

An armorial helmet pitcher creamer. V17 HERON or HERNE. Qianlong ca. 1790. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 590).

At the same time, these decorative changes cannot be attributed to ideology alone. The rise in European factory production introduced standardization, mass production, and quality control, which reshaped consumer expectations. Japanese porcelain also gained market share by offering adaptable designs at competitive prices. In contrast, Jingdezhen remained largely artisanal, with limited technological adaptation until the late nineteenth century. These economic and technological pressures interacted with shifting perceptions of China, accelerating the marginalization of Chinese motifs. Acknowledging these intersecting factors avoids reducing the trajectory to a purely ideological one and situates armorial porcelain within the wider transformations of global porcelain trade.

4. Consumption, Class, and Moral Order: Transformations of British Social Values in the Eighteenth Century

In eighteenth-century Britain, Chinese armorial porcelain functioned not only as an object of luxury but also as a prism through which broader social transformations can be examined. This period witnessed a significant shift in cultural values, from an aristocratic ethos rooted in hereditary privilege and martial honour to an emerging ideal of civility, taste, and individual distinction. Against this backdrop, Chinese armorial porcelain, distinct from mass-market luxury imports, became a powerful material vehicle for expressing new modes of identity and class differentiation. This section situates Chinese armorial porcelain within evolving patterns of consumption and moral sensibility, drawing on consumer theory (Veblen [1899] 2017, pp. 18–32) and Charles Taylor’s account of the moral transformation brought about by “le doux commerce (Taylor 1989, pp. 285–86),” to argue that the material and symbolic qualities of armorial porcelain played a pivotal role in articulating eighteenth-century British ideals within a globalized world.

4.1. The Psychological Turn in Luxury Consumption

Consumerism, as a sociological theory, was introduced by American sociologist Thorstein Veblen in his seminal work ‘The Theory of the Leisure Class’ (Veblen [1899] 2017), where he described the phenomenon of purchasing goods to display wealth, power, taste, and social status (Veblen [1899] 2017). Veblen termed this behaviour “conspicuous consumption”. He argued that the significance of purchasing goods goes far beyond their utility, with their symbolic value as social markers being paramount (Whitford 2010). Within this framework, eighteenth-century Chinese armorial porcelain can be seen as an important example of conspicuous consumption.

As Maxine Berg notes, although Chinese porcelain in the eighteenth century remained a luxury item, the expansion of global trade made Chinese porcelain more accessible, even to the rising middle class (Berg 2007, p. 27). As the popularity of luxury goods diminished their symbolic significance, the wealthy sought more scarce, novel, or personalized items to maintain their social distinction (Berg 2007, p. 27). According to David Howard’s statistics, the period from 1750 to 1760 saw the highest peak in the commissioning of armorial porcelain, accounting for 18.7% of the total number of commissions in the eighteenth century (Howard 1974, 2003). In this context, Chinese armorial porcelain, with its customizability and uniqueness, became an important means for these wealthier consumers to distinguish themselves from mass-market luxury goods. The personalized designs of armorial porcelain reinforced its rarity and became a key vehicle for conspicuous consumption.

A comparative analysis between the heraldic devices on Chinese armorial porcelain and the reign marks on imperial wares underscores how both functioned as markers of status and legitimacy, though in different cultural registers. On imperial porcelain, reign marks from the Jingdezhen kilns, often bearing the emperor’s name or seal, asserted a direct connection to the throne. They guaranteed authenticity, exclusivity, and supreme authority (Gerritsen 2016, pp. 116–17). By contrast, the coats of arms painted on export porcelain materialized British patrons’ aspirations for lineage, prestige, and social distinction. Juxtaposing these two systems of inscription shows how Chinese and British elites alike used porcelain decoration as a medium to affirm identity and power. Dutch writer Olfert Dapper documented the royal symbolism embedded in these marks, informing European consumers of their significance (Gerritsen 2016, p. 134). Inspired by this practice, European patrons, including the British began to incorporate their own family crests into Chinese armorial porcelain, mimicking the exclusivity and status associated with Chinese imperial porcelain.

While the motivations behind these practices differed. Chinese imperial marks emphasized political authority and legitimacy, whereas British crests focused on personal or familial prestige. Both used porcelain as a medium to signify status. This practice reflects a psychological strategy of differentiation. By emphasizing the rarity and uniqueness of Chinese armorial porcelain, British consumers distinguished themselves not only from the growing market of luxury goods but also within their own social hierarchy. In doing so, they incorporated this distinction into their identity, using material culture to project and reinforce their social status. Chinese armorial porcelain thus functioned as a symbol of exclusivity, both reflecting and shaping the cultural dynamics of consumption in the eighteenth century.

4.2. The Reordering of Values: From Aristocratic Honour to Commercial Civility

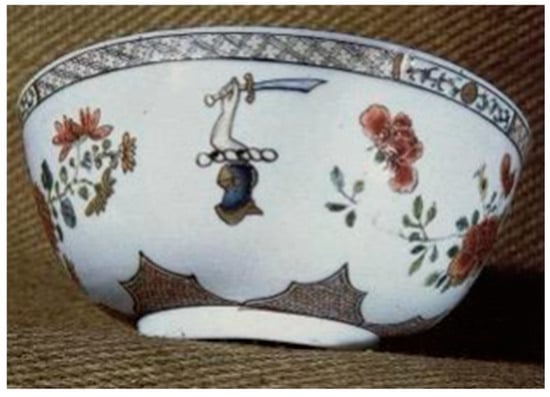

Chinese armorial porcelain not only serves as a psychological reflection of the British rising middle class but also reflects the broader shift in British social values. This article argues that it embodies the rise in a new valuation of commercial life, which can be traced to the decline of the aristocratic honour ethic, where military glory was once paramount. Charles Taylor’s concept of “le doux commerce (commercial life)” describes the emergence of these new values, emphasizing peace, civility, and the orderly conduct of commercial life (Taylor 1989, pp. 285–86). These values, which became central to modern culture, shifted societal focus from traditional noble values tied to military honour to concerns over personal well-being and the rhythm of daily life (Taylor 1989, p. 286). Chinese armorial porcelain can be seen as a material manifestation of this moral transformation.

The decorative motifs on armorial porcelain exemplify this shift through their fusion of heraldic crests, symbolizing military power and noble lineage, with Chinese floral patterns (Figure 25), representing harmony and nature. This juxtaposition illustrates that British patrons did not entirely abandon traditional symbols of military honour but rather integrated them with the emerging ideals of commercial life. By blending the personalized crests of aristocratic tradition with the refined esthetics of Chinese porcelain, these objects served multiple purposes: they conveyed personal identity, signified cultural sophistication, and reflected the aristocracy’s acknowledgment of the evolving commercial values reshaping society.

Figure 25.

Chinese armorial bowl E4 MACRAE. Yongzheng ca. 1730. In Chinese Armorial Porcelain II, by Howard (2003, p. 158).

In this way, Chinese armorial porcelain not only captured the changing priorities of its patrons but also became a medium through which the fusion of old and new values was visually articulated, embodying the complex interplay between tradition and modernity in eighteenth-century Britain.

5. Conclusions

This study has systematically examined the decorative system of Chinese armorial porcelain by foregrounding the role of botanical and animal motifs as key visual and cultural components. Chrysanthemum, peony, bamboo, rose, lotus, dragon, and phoenix have been identified and categorized, with their compositional features and shifting meanings traced across contexts. Comparative visual analysis demonstrates how these motifs moved from cosmological and moral frameworks in China to recontextualized elements in eighteenth-century export wares, becoming flexible carriers of negotiation across media, markets, and audiences.

The trajectory of European perceptions across the eighteenth century followed a layered path. In the early decades, Chinese motifs were received with genuine curiosity rooted in alterity, inspired by Chinese technical mastery and esthetic richness. By the later eighteenth century, as Enlightenment rationalism and Eurocentric attitudes consolidated, these same motifs were increasingly framed within an Orientalist perspective that positioned China as distant and subordinate. Decorative shifts on porcelain thus registered this ideological transformation in real time and material form.

Armorial porcelain also reflected significant changes in British social values. Aristocratic privilege and martial honour gave way to new ideals of civility, taste, and domestic order. Patrons commissioned heraldic services that fused family crests with Chinese motifs to signal lineage, refinement, and worldliness. The transition from ornamental display plates to functional tea and tableware embodied this moral reordering, as luxury was redefined through practices of sociability and everyday refinement.

Yet the decline of Chinese porcelain in European markets cannot be explained solely by ideological or cultural factors. Economic and technological developments must also be considered. The European industrial revolution introduced mechanized production, standardized forms, and quality control, reshaping consumer expectations and expanding output. Japanese kilns, too, adapted flexibly to European tastes, offering competitive designs and pricing. In contrast, Jingdezhen largely retained artisanal methods, with limited technological innovation until the late nineteenth century. This divergence reduced the competitiveness of Chinese porcelain in terms of consistency, durability, and price. As a result, qualities once admired as signs of refinement came to appear irregular when judged against industrial standards. The waning prestige of Chinese porcelain was therefore the outcome of intersecting structural forces in ideology, economy, and technology.

Beyond hybridity, these wares must be understood as material instruments that actively mediated and reshaped relations of power. They inserted Chinese craft into European systems of heraldry, domestic ritual, and consumption, thereby staging not only esthetic encounter but also the negotiation of authority and social distinction. Heraldic centrality on porcelain disciplined vision and reinforced hierarchies of lineage, while the placement of Chinese motifs at the margins both acknowledged and contained alterity. At the same time, the decorators of Jingdezhen retained agency: their translations of foreign emblems into Chinese pictorial logics preserved indigenous design intelligence, ensuring that European power was never simply inscribed but always re-articulated through Chinese hands.

Seen in this light, Chinese armorial porcelain cannot be reduced to ornamental hybridity or passive souvenirs of global trade. They were active mediators in an unequal but dynamic cross-cultural field, shaping eighteenth-century taste, enabling British elites to materialize prestige and civility, and registering the persistence of Chinese artistic agency within asymmetrical global circuits. These objects thus reveal how decorative surfaces became a site where visual languages, social values, and geopolitical power were continuously negotiated.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | These two volumes are the most comprehensive references works on Chinese armorial porcelain in the eighteenth century, documenting European, especially the British commissions with detail illustrations and owner’s provenance information. |

References

- Abernethy, David B. 2000. Phase 1: Expansion, 1415–1773. In The Dynamics of Global Dominance: European Overseas Empires, 1415–1980. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. 2013. Post-Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts, 3rd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Maxine. 2007. The delights of luxury. In Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2009. Cultural Hybridity. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Camille, Michael. 1992. Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, Kirti N. 2006. The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660–1760. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chiem, Kristen L. 2018. Possessing the King of Flowers, and other things at the Qing court. Word & Image 34: 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clunas, Craig. 2004. Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Boyuan 邓博元. 1989. Zhongguo lidai taoci wenyang 中国历代陶瓷纹样 [Chinese Porcelain Patterns Through the Dynasties]. Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer, Morgan C. T., Rachel L. Denyer, and Howell G. M. Edwards. 2024. Armorial Porcelain: The Genesis. Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, William. 2014. Silk and Globalization in Eighteenth-Century London: Commodities, People and Connections c. 1720–1800. Ph.D. dissertation, Birkbeck, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, Anne. 2016. Chinese porcelain in local and global context: The imperial connection. In Luxury in Global Perspective: Objects and Practices, 1600–2000. Studies in Comparative World History. Edited by Karin Hofmeester and Bernd-Stefan Grewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 116–37. Available online: https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/35354/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Guo, Xi 郭熙, and Zhenheng Wen 文震亨. 2019. Zhonghua yawenhua jingdian xilie 中华雅文化经典系列 [Zhonghua Elegant Culture Classics Series]. Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, John Spencer. 1984. The phoenix. Religion & Literature 16: 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, David Sanctuary. 1974. Chinese Armorial Porcelain. London: Faber & Faber, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, David Sanctuary. 2003. Chinese Armorial Porcelain. Wiltshire: Heirloom & Howard Limited, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, Munsterberg. 2011. Arts of China. North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xue-Hui. 2017. Development history and art characteristics of Chinese armorial porcelain. Ceramics Technical 42: 16–19. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.243451160495104 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Liu, Soleilmavis. 2023. The Origins and Developments of Dragon and Phoenix Worships in Ancient China. Paper Presented at E-Leader Conference held in January 2023 by CASA (Chinese American Scholars Association) and Training Vision Institute, 52 Jurong Gateway Road, JEM Office Tower, Singapore. Available online: https://www.g-casa.com/conferences/singapore21/paper_pdf/Liu%20Phoenix%20Dragon.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Liu, Zhuo 刘卓. 2013. 18世纪中国瓷器上的西洋花卉装饰 [18th-century Chinese porcelain with Western Flower Decorations]. Shoucang 收藏. Available online: http://collection.sina.com.cn/jczs/20131213/1346136843.shtml?from=wap (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Long, Chunlin, Yanan Ni, Xinbo Zhang, Tong Xin, and Bo Long. 2015. Biodiversity of Chinese Ornamentals. Acta Horticulturae 1087: 209–20. Available online: https://www.actahort.org/books/1087/1087_25.htm (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Marder, Michael. 2023. The Phoenix Complex: A Philosophy of Nature. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthu, Sankar. 1999. Enlightenment anti-imperialism. Social Research 66: 985–87. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40971360 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Rousseau, George Sebastian, and Roy Porter. 1990. Exoticism in the Enlightenment. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward Wadie. 2003. Orientalism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Senter, Phil, Uta Mattox, and Eid E. Haddad. 2016. Snake to monster: Conrad Gessner’s Schlangenbuch and the evolution of the dragon in the literature of natural history. Journal of Folklore Research 53: 67–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, Annette. 1992. Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition. American Art 6: 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Charles. 1989. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valerie, Jones. 2013. The Phoenix and the Resurrection. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Veblen, Thorstein. 2017. The Theory of the Leisure Class. London: Routledge. First published 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Patricia Bjaaland. 2008. Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford, Katie. 2010. Conspicuous consumption, social emulation, and the consumer revolution. New Histories. 2. Available online: https://newhistories.sites.sheffield.ac.uk/volumes/2010-11/volume-2/issue-2-revolutions/conspicuous-consumption-social-emulation-and-the-consumer-revolution (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Wilson, J. Keith. 1990. Powerful form and potent symbol: The dragon in Asia. The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 77: 286–323. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Wen-Ting. 2021. Driven by Power: Four Case Studies of the Possession and Appropriation of Chinese Porcelain in 18th-Century Europe and China. Ph.D. dissertation, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, Li. 2021. Study on decorative patterns of ceramic landscape paintings in Qing Dynasty. Journal of Literature and Art Studies 11: 833–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Chunming 余春明. 2011. Zhongguo mingpian: Ming Qing waixiao ci tanyuan yu shoucang 中国名片: 明清外销瓷探源与收藏 [China’s Calling Card: Tracing the Origins and Collecting of Export Porcelain in the Ming and Qing Dynasties]. Shanghai: SDX Joint Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Jiayan. 2014. A comparative study of bamboo culture and its applications in China, Japan, and South Korea. Paper presented at the SOCIOINT14—International Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities, Istanbul, Turkey, September 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Meishi 张梅石. 2020. “Sijunzi zai xiqu fuzhuang zhong de yunyong” 四君子纹在戏曲服装中的运用 [The Application of the Four Noble Ones Motif in Opera Costumes]. Xiqu yishu 戏曲艺术 41: 134–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Richard. 2021. King of flowers: Reinterpretation of Chinese peonies in early modern Europe. Journal for the Southern Association of the History of Medicine and Science 3: 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yalin 张亚林, and Hanxue Liu 刘寒雪. 2009. 浅析明清时期陶瓷荷花纹的装饰特征 [Analysis on the decorative characteristics of ceramic lotus patterns in the Ming and Qing dynasties]. Taoci yanjiu 陶瓷研究 2: 101–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zilen, Alexis Marie Michelle. 2017. Romanticism and Religion: The Superb Lily. Wonders of Nature and Artifice. 26. Available online: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/26 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).