1. Introduction

African-born artists are increasingly featured in Europe’s recurring art festivals these days. Presentations such as Kassel’s documenta, Berlin Biennale, La Biennale di Venezia, or the European Nomadic Biennial Manifesta should be viewed as leading art institutions that develop the discourse while adapting their models to political climates and corporate expectations. Having an impact, they establish the contemporary paradigms of official art. Negative consequences may abound—but world exhibitions also provide space where the establishment can be subverted. These “mega-shows” are by no means birthplaces of revolutions or avant-gardes; they rather nourish and disseminate the already matured trends. And as their propositions globalise, the mechanisms of distribution also evolve: passive viewing gives way to active participation.

This paper aims to frame—even if partially or subjectively—the presence of African artists at contemporary European mega-exhibitions. I look at the years 2017–2025, a period spanning several important editions of the said shows, on the one hand, and on the other, a series of geopolitically significant events; while the former brought about an increased representation of Africa’s art and made its message clearer, the latter were symptomatic of new and prolonged crises around the world. In the present day so defined, African artworks exhibited in Europe display a number of common thematic features: they revise art histories, deal with colonial violence, oppose racism, appropriation of cultural and natural resources, as well as vicious treatment of public space, or—last but not least—simply reveal peculiar, non-Western sensitivities.

Mega-shows have had different beginnings—all of the formats discussed herein, however, are products of social and political processes initiated in the West and occurring at the turn of the last century. At the same time they adapt, as most spectacles do, to the current events and circumstances. In a severely destabilised era, exhibitions have become carriers of radical messages, and manifestations of Africa’s cultures drive change within the art world’s institutions. African-born artists are effective—because their works are geographically and historically relevant, credible as critique, and highly participatory; and thankfully, more often than not they steer clear of colonially oriented presentations today, avoiding the status of a looted fetish—of something appealing and curious but still inferior.

Hereunder, an argument is advanced that since around 2017, the presence of Africa’s output in Europe has been emancipating the artists: treated instrumentally for a long time, they eventually assumed the role of negotiators. African artworks have been featured before—especially from 2002 onwards, starting with Documenta11; what makes the situation today substantially different, though, is that the pieces presented now tend to begin far away from the European continent. It is there, in the communities of the South, and it is with native, locally originating narratives about these places, often documenting disgraceful abuse, that artists conduct a kind of field work, amassing the evidence they need to demand compensation for their past as well as recent harm. To this end, methods and languages of contemporary art are employed that allow to create spaces of confrontation—which takes place at mega-shows and brings together the Global North, as those whose conduct is subject to revision, and the Global South, as the ones who are revising it. The works of art themselves, also discussed in this paper, are not just displayed and interpreted as they become artifacts on yet another level, in the process of symbolic renegotiation reshaping the audience’s awareness.

2. Concepts and Method

In the 21st century, recurring exhibitions of contemporary art have become art institutions in their own right, whose personnel—curatorial and artistic elites—shapes the wider discourse. Some argue, convincingly so, that the worldwide exhibition movement and the process of “biennalisation” have replaced the academia in the role of art historiographers (

Esche and Hlavajova 2009).

The institutions in question are deeply rooted in the recent past as they emerged as a result of major political events. In 1955, documenta launched in Kassel to dissociate from the nationalist-socialist aesthetic and celebrate a return to modernism. The European Nomadic Biennial Manifesta, founded in 1996, was euphorically fuelled by the fall of the Iron Curtain. Traditions like these justify reflections about the present day.

But there are downsides too. Driving the monetary value of artworks and strengthening artists in the marketplace, large-scale exhibitions take part in the exchange of commodities, which makes the art world similar to the entertainment industry—a field of interest to politicians and global corporations. Consequently, symbolic values are overshadowed at times by attainable profits.

2.1. Towards a Revised Exhibition Format: Opportunism, Carnival, Participation, and the Present

Despite obstacles to substance, mega-shows leave room for a wise and ethical narrative to grow. Their immense exposure and diversified viewership call for negotiating a mega-exhibition’s content carefully. Employing the conceptual, philosophical apparatus of Paolo Virno, cultural sociologist Pascal Gielen spoke of ‘opportunism’ (

Virno 2004)—a notion carrying negative connotations which nevertheless applies here positively in its most basic and literal sense of seizing opportunities (

Gielen 2009). Making any phenomenon visible through platforms frequented by hundreds of thousands of people requires concessions: curators and artists have to respond to what is around them without compromising their artistic and ethical goals.

All biennials follow the logic of a spectacle, but La Biennale di Venezia, documenta, Berlin Biennale, and Manifesta each stand out in particular as an extremely well-financed carnival—a carnival in Mikhail Bakhtin’s understanding: not a show but an actual, albeit transient, form of life itself; not performed but experienced (

Haynes 1995). To look at the scale of everyday involvement in culture and the growth of participatory models is to see how complex and significant these are in a utilitarian view. The latter redefines the artwork as proposition, the artist as proposer, and the viewer as user—a tremendous ontological shift in the arts (

Wright 2013), already noticeable in programmes of the most visited exhibitions.

This paper’s perspective of the past almost-decade corresponds to a sequence of globally destabilising events: the COVID-19 pandemic, migration crises, war in Ukraine, and new confrontations between the world’s superpowers. Artists draw inspiration from adversity—it was a fact notably reflected in Adam Szymczyk’s curatorial concept for documenta 14: in 2017 the influential art festival moved from prosperous Germany to crisis-struck Athens (

Szymczyk 2017). In a time of helplessness and stagnation, when art institutions failed, bottom-up propositions amassed where a more optimistic message was most needed: in communities, out in the streets.

Before Athens, artistic endeavours had seldom connected this strong to histories and traumas of particular places and, at once, to the present. Apart from being a carrier of intriguing materiality, however, art is also an emotional tissue that grows on distressed and exhausted social bodies. It is a reaction—or response—to the destabilisation of the world; it aspires to be the remedy. Older works receive brilliant new meanings when curatorially negotiated, partially giving answers to the whys of the dissolving status quo.

2.2. Starting Points for the Exploration of Multiplicity, and Establishing Diasporic Public Spheres

In the artistic discourse examined here, one argument prevails: that today’s grave stalemates were brought about by certain expressions of globalism and capitalism. Similar points—oversimplified, surely, but working just fine in the field of art—are often made in curatorial statements. This model of thought is also applied to the situation of Africa, a long-time victim of Western policies and programmes enforcing uniformity.

African art eventually found its actual advocate in Nigeria’s Okwui Enwezor—not necessarily the first one to speak up, but certainly the first one to be heard. Curating documenta 11 (2002), he made it into a genuinely global exhibition. It was also then that art came to be seen clearly as a way to produce knowledge (

documenta 2002). The Nigerian intellectualist not only expanded the narrative about Africa’s output; he also made sure it appealed to the audiences of the West (

Enwezor and Okeke-Agulu 2009).

1Enwezor was acutely aware that the growth-oriented mega-shows—he used that word on every occasion—were complicit in processes whose cynical mechanisms blunt all cultural diversity; but he also knew that this opened up new possibilities of fierce dissent on the part of artists by prompting them to radically rethink what is contemporary, what is modernist, and what art should do. It is in Enwezor’s spirit to think of curatorial narratives as explorations of historical circumstances in which art has been, and still is, created, and of exhibitions as spaces that absorb different cultural translations. The latter often function as agorae and are able to establish “diasporic public spheres” (

Enwezor 2025). The literature on the subject acclaims Enwezor’s legacy and his strong, inherently geopolitical views on the matters of art. Enwezor managed to combine Western artistic formulae with those of the Global South. In his shows, African aesthetics appeared most expressively and distinctively, wholly different from the well-known metropolitan language of the West (

Green and Gardner 2016).

I argue that new ways of dramatising artistic practices—anticipated already in the early 2000s, in analyses of African artworks—are now exploding. Locating projects outside any typical exhibition spaces, they cause the monolithic mass of art world’s culture to crack. They celebrate the situation and deal with problems within communities, employing artistic methods and cultural codes but involving different audiences—inhabitants of Africa’s villages, for instance, in their natural habitats. Finding itself in circumstances like these, an art institution has to question its own mode of operation and become a platform that actively encourages dialogue between individual participants (

Deliss 2005). With case studies covering the period in question, an image of the art festival field is constructed in which new turning points and format-wise redefinitions keep appearing; looking back, transformations culminate with documenta 15 (2022).

Revisions of globalism, usually approached from either an imperial or a colonial perspective (

Hardt and Negri 2000), result in adjustments to canons and to knowledge production systems, ruled so far by Western and national institutions. This paper’s interpretative process, however, looks away from the national pavilions at the Venice Biennial—because these, being representations of state apparatuses, cannot be deemed objective.

One has to keep in mind that Africa is not unified and uniform: it is a continent of many faces, populated by divergent native cultures that found different ways to break free—not always without trouble—from what had been imposed on them by Europe’s colonial powers. The paper examines the output of artists and curators from Benin, South Africa, Nigeria, Algeria, Ghana, Egypt, Senegal, Zambia, and Kenya, as well as the work of a couple of Europeans, South Americans, and a Palestinian. As dispersed around the world as they are, this attempt probably will not suffice to draw universally applicable conclusions; in any case, to generalise is an undesired and unwelcome colonial practice—therefore generalisations are avoided here methodically, in favour of an exploration of multiplicities, which best reflects the states of different phenomena observed in the art world.

3. African Art Displayed at Europe’s Recurring Mega-Shows of Contemporary Art in 2017–2025: Case Studies

3.1. Seized Artworks, Their Circulation, and Subversive Play with the System

Postcolonial research implies discussing loot and advocating restitution—but it would be naïve to believe that European countries no longer pursue business against the interest of the Global South. Alessandra Ferrini’s 2024 film “Gaddafi in Rome: Anatomy of Friendship” (shown at the 60th Biennale Arte in Venice) demonstrates this unwavering tendency: collecting media coverage of the Libyan dictator’s get-together with Italy’s then-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, it shows the African ruler being received with honours, as any respectable statesman and true friend would be. Subject to artistic treatment, the scene appears downright grotesque.

Examinations of the past are equally disillusioning as far as the corporate financial system is concerned. Peru’s Daniela Ortiz and Catalonia’s Xose Quirga set out to identify traces of colonial artifacts in the public space of Barcelona. Their 2013 photographic series “Nation State. Part 1”—completed in 2013, displayed at Manifesta 15, which was held in the Catalan capital in 2024—shows existing monuments to figures tied to slave trade, as well as buildings of institutions that used to fund similar colonial pursuits.

Protests grow louder where the ethics of shame has not yet manifested itself at all. “We Don’t Need Another Hero” was the motto of the 10th Berlin Biennale (2018), curated by a team

2 led by South Africa’s Gabi Ngcobo. The exhibition made inquiries about history, its malleability, and a human being’s hopeless entanglement in it. What inspired the programme were the events of 9 April 2015, when students at the University of Cape Town forcefully took down a monument to Cecil John Rhodes (1853–1902), one of Britain’s most “distinguished” colonialists and leading contributors to the establishment of the United Kingdom’s rule in South Africa. Rhodes was counted among the most powerful and wealthy individuals of the late 19th century, as confirmed by the existence of the part of Africa known today as Rhodesia, and the toppling of the monument—captured in memorable photographs—became symbolic of the decolonisation of higher education (

Ngcobo 2018).

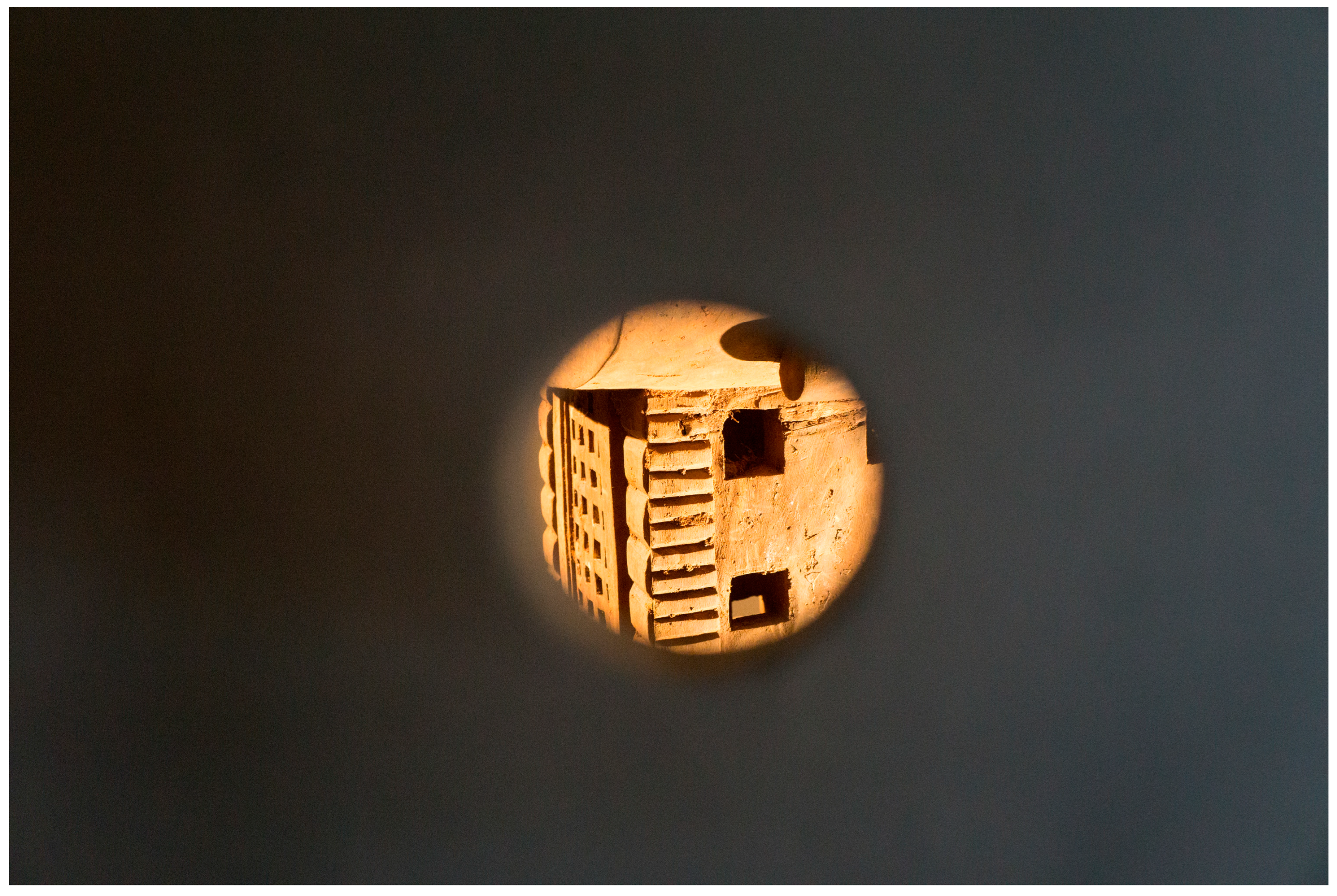

3In the exhibition, Benin’s Thierry Oussou was featured with his work titled “Impossible Is Nothing” (2016–2018)—documentation of archaeological excavations that the artist arranged in Allada (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Prepared in line with scientific standards, the operation involved students of archaeology from Université d’Abomey-Calavi, for them to dig out and reveal—to their astonishment—the throne of King Béhanzin (1844–1906), an item which had remained in the hands of the French state since the early 1890s. The hoax received media coverage, turning the public attention to the fact of the monument having been seized and held far away from its place of origin. As reported by “The Guardian,” UAC’s Dean of the Faculty of Archaeology demanded that the copy of the throne not be displayed as the actual relic (

Berning Sawa 2018)—somewhat absurd, but also telling: we stick to images of reality rather than facts. Paradoxical outcomes like that are vital to discussions about rights and ownership, and artists readily stress the symbolic aspect of this tension.

Oussou’s installation, exhibited at Akademie der Künste, included the film and the unearthed fake artifacts. Visitors could see the replicated throne by looking through a coin-sized hole in an otherwise solid wall—a falsified image of reality is always limited, and this is precisely what makes such images desired; but the throne itself invariably reminds one about the outright truth of loss and trauma. The monument has been retrieved symbolically, finding its way to people’s memory; it has lent meaning to the lives of individuals who now connect over the long-gone piece of history. The installation is a kind of performative study of materiality, transcending historiography in order to trace links between objects in time, and between human beings in communities.

Legal intricacies concerning the flow of commodities (also artistic) between Africa and the rest of the world are a fairly frequent theme. At the European Nomadic Biennial Manifesta in Palermo (2017), Algerian-born Lydia Ourhmane presented “The Third Choir” (2014): an installation made from tens of oil barrels, all visibly branded by Naftal (

Figure 3). In each container there was a telephone placed, emitting an industrial sound. To have the work displayed in Europe, the artist had to work her way around an act, dated 1962, prohibiting—in good faith, perhaps—the transportation of any works of art out of Algeria. The administrative burden involved was documented as part of the project.

In the material aspect of the piece, binding trade laws are reflected. The containers, originally intended for oil that is exported to Europe, were immobilised in North Africa as soon as they entered the field of art. Also the art system itself contributed to the story of this work: in 2021, the installation made it to the prestigious collection of Britain’s Tate Gallery—like so many ethnographic artifacts, it came to be locked up in a museum. What makes the situation different, however, is that the artist’s actions were deliberate: it was her strategy to activate the paradoxes of global circulation, to reveal the mechanisms of commodification and museification of art.

The work of Oussou and Ourhmane grabbed the attention of the European establishment: diplomats, museums, and the popular press. Objections and calls for justice sometimes do resonate widely, drawing crowds to the streets. Back in 2017, documenta 14 (2017)—both in Kassel and, first, in Athens—featured Ibrahim Mahama’s interventions in the public space. In his projects, the Ghanaian uses hessian (jute cloth) sacks, which he obtains from West African traders. Dirty and worn from charcoal or food products that they originally contained, jute sacks are charged with the materiality of hard physical work. The sacks themselves are likely made in Asia, then travel long distances between continents. They are marked by memory, perhaps its most significant constituents being sweat and blood of Africa’s contemporary working class. In this amalgam of meanings, jute itself is not neutral either: a natural, durable, and cheap material used for furnishing homes and making clothes.

Mahama sews pieces of jute cloth together, into gigantic skins for buildings or other urban objects. In Kassel, executing “Check Point Sekondi Loco. 1901–2030. 2016–2017,” he enveloped the Torwache—historic, 19th-century guarded town gate. In Athens, he invited the public to sew the cloth together on the city’s central Syntagma Square. The actions disturbed the European splendours of orderly public space and elegant architectural monuments.

At times, voices of dissent are more intimate, addressing one’s personal experience. MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa, Nare Mokgotho) is a group of Johannesburg-based artists who, by examining space and its effect on people locally, explore various dimensions of Black life. Their installation “Mafolofolo: a place of recovery,” presented at documenta 15 (2022), took the form of ascending terraces or stairs—elements of an intentionally unergonomic, inconvenient environment. It is a materialisation of the feeling of being unprivileged, deprived of rights, separated from land—inspired, specifically, by the land act of 1913, which took away 90% of native property and transferred it to the white minority. In the exhibition space, the floor was a synthetic map, with administrative boundaries indicated. The installation’s entire content was a result of years-long research into the dynamics of ownership, especially into displacements of the Bokoni people. Thus the artists created an atmosphere of mourning—and healing, too, attempted by reconnecting to the land.

Similar was the inspiration behind the TAM collective, a platform initiated by Palestine’s Sandi Hilal and Italy’s Alessandro Petti in which architects and researchers collaborate. In “Ente di Decolonizzazione, Borgo” (Entity of Decolonisation), presented at the 12th Berlin Biennale (2022), they focused on Libya, Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia’s legacy of 1940s fascist architecture and urban planning. The spatial modules constituting the work’s main parts were in fact upscaled fragments of elevations. Visitors could move them around—and by doing so, deconstruct the heritage and decolonise it.

The above examples combine into a coherent critical model for artists’ mixed-media projects: one of imagery and tangible evidence—be it authentic or fabricated—of struggles against the historical violence of seizures and instrumental treatment of cultural and intellectual property as well as land. In the field of art, these images are obviously less compelling than the real terror, energy, and risk on the part of the young rebels at the university; and less troubling than the lack of agency in ongoing political pursuits of restitution. Immense strength, however, of this artistic language and the related curatorial vision lies in their credibility, guaranteed by the identities of artists and artifacts alike. Even Ourhmane’s installation, although held at Tate, resisted petrification behind museum walls by getting there subversively par excellence.

3.2. Testimonies to Violence, and the Inability to Heal

Dineo Seshee Bopape’s installation “Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings]” (2016) dominated the KW Institute for Contemporary Art during the 10th Berlin Biennale (2018) (

Figure 4). It consisted of objects and works of other artists—flooded in red light, they resembled charred ruins; a video documenting Nina Simone’s peculiar rendition of “Feelings” at the Montreux Jazz Festival of 1976—emotional, full of interactions with the audience; and footage from the trial of Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s former president who faced rape charges—referencing the burst of sexual crimes in the country, a predicament looming on women’s daily lives.

Nigeria’s Etinosa Yvonne interviewed females who had been displaced from their villages, and photographed them in black and white (“It’s All In My Head,” 2019–2020). The subjects turn their eyes away from the camera; some of the compositions are mostly burqas. This particular work, presented at the 12th Berlin Biennale (2022), tells the story of women who suffer from war and male cruelty, abused in acts of ritualised violence. That same exhibition featured Binta Diaw’s installation “DÏÀSPORA” (2021/2022): a deeply moving tangle of ropes made from female hair, and small, sprouting mounds. Italian of Senegalese descent, the artist deals with identities and traumas of Black women, working with the history of slavery and the unorthodox—from Western perspectives, that is—matrilineal kinship.

In the same year, Algerian artist Ammar Bouras displayed in Berlin a collage of photographic works with a video projection concerned with the present and the past of the desert landscape. A set of geographical coordinates in its title—“24°3′55″ N 5°3′23″ E” (2012/2022)—pinpoints the location where France carried out an underground nuclear test back in 1962. It is a work about violence against a foreign continent and its scenery, evidence of conflicts being transplanted away from superpowers’ homelands.

Curating that instance of the festival, titled “Still Present!,” Kader Attia (Algerian-French) restlessly inquired about the contemporary condition and the possibilities it gives us. His own artistic pursuits revolve around individual and social implications of violence; their repair is to be seen as an act of resistance (

Attia 2022). That theme seems to have faded in the following edition, held this year. One of the projects on show, aspiring to provide remedies—“Doctor Bwanga in Berlin” by Zambia’s Bwanga “Benny Blow” Kapumpa, an artist working in the social media—turned out rather unconvincing. Banners around town announced sessions with a fictional healer, saying: “Your ancestors are trying to speak with you.” Aware of civilisational diseases, Kapumpa decided to confront them with popular beliefs and healing practices kept alive where he comes from. A booth was erected in the courtyard of the KW Institute, offering phone advice from the Doctor—supposedly a traditional

ng’aka. On the other end of the line, a virtual, non-human consultant was generating answers to the caller’s questions; or, strictly speaking: an algorithm was mechanically administering extracts from the Zambian tradition to anyone who dared to undergo this strange, make-believe therapy.

In July, however, Doctor Bwanga was on vacation, his booth closed: the algorithm failed. Knowledge and skill thinned out, compromising the project as mere noise and commotion meant to capitalise on ancient wisdom—an attractive alternative to the rationalism of the West, whose popular culture readily absorbs elements of religious or otherwise supernatural systems from afar. Here, the capital involved was the many African peoples’ ritualistic reverence for ancestral spirits, seen as a way of safeguarding oneself and securing an affluent life (

Meredith 2014). The Nobel laureate V.S. Naipaul argued in his non-fictions that Africa’s culture is one of multiplicity, producing complicated biographies of exceptional individuals. Their spirituality is defined, on the one hand, by a deeply physical, carnal expression, and on the other, by the ability to make meaningful use of mental energy and engage in dialogue with ghosts and spectres (

Naipaul 2010).

3.3. Disputes Around Aliens, Strangers, Foreigners

In 2015, the African and Middle Eastern exodus to the European Union culminated in massive migrations. Fleeing from coups, wars, and the global warming, the masses sought better living conditions in the exact region which is responsible in part for the crises back where they came from. Leaders of the wealthy West were reserved in their reactions—these, at times, even opposed any humanitarian logic. The issues at hand polarised Western nations, disturbing the pillars of European prosperity and encouraging racist and xenophobic tendencies.

Already in 2002 the Copenhagen-based collective Superflex, overwhelmingly disappointed, distributed a poster saying, “Foreigners, Please Don’t Leave Us Alone with The Danes!”—reissued for the 60th Biennale in Venice (2024). At documenta 14 (2017)—as a tribute, for a change—the “Monument to Strangers and Refugees” was unveiled. The piece was an obelisk, drawing on antiquity, with a line from the Holy Scripture engraved: “I was a stranger and you took me in” (Matthew 25:35). The man behind the work was Olu Oguibe, Nigerian-born Professor at the University of Connecticut. Having a monument like that erected in a middle-sized German town, however, where right-wing and liberal electorates negotiate their balance in the council, seems rather pointless.

“Exile Is a Hard Job” (1983–2024), in turn, is a collage of snapshots from migrants’ lives, constructed by Egyptian-born Nil Yalter over a period of more than forty years. Black-and-white photographs are contrasted with the title—painted in red, resembling a propaganda slogan. The work was featured prominently at the 12th Berlin Biennale (2022) as well as the 60th Biennale Arte di Venezia.

Entire curatorial concepts, too, have had migration as their organising theme. Manifesta 12 (2018) was held in Palermo, Sicily, in a place where, since ancient times, Europe meets Africa—where diverse cultures mix and clash. Today, in the island’s unrelenting heat, Sicilians cope with past and present traumas of organised crime and corruption, at the same time facing waves of migrants from the South.

For the 2018 edition, a peculiar allegory of transfer and relocation was proposed: the botanical garden, a kind of space conceived in the Enlightenment (just like the museum), established for the cultivation of plants that only grow naturally in distant parts of the world. When discipline is observed and local factors adjust to the needs of exotic organisms, the domestic and the foreign coexist fruitfully.

Founded in 1779, Orto Botanico dell’Università degli Studi di Palermo was intended, among other things, for growing medicinal herbs—and the notion of a remedy, as applied in the artistic discourse, frequently recurs. The Palermitan project, titled “The Planetary Garden. Cultivating Coexistence,” employed a significant theoretical shift: the festival’s creative mediators (Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, Bregtje van der Haak, Andrés Jaque, Mirjam Varadinis) extended the definition of migration to include non-human organisms, namely plants and animals; after all, these are impacted as well by spatial translations and the ensuing adaptations. Francesco Lojacono’s oil painting “Veduta di Palermo” (1875) depicts the town as seen from its suburbs and fields. A number of plants appear in the picture that we associate today with Sicily. Each was described, indicating its place of origin too—and, as it turns out, none of them is actually local, in the same way that Sicily’s ethnically diversified population cannot be considered autochtonous (

Pestellini Laparelli et al. 2018).

In Sicily, the Nigerian-born artist Jelli Atiku organised an extended performance titled “Festino della Terra (Alaraagbo XIII)” (Festival of the Earth)—a procession of dancers painted green, carrying soil and plants as if these were offerings, so accentuating the non-human element of reality and its essential role in ecosystems. The festivity was likely inspired both by the locally significant processions celebrating Santa Rosalia, typical to Palermo and the island in general, and by the traditions of the Yoruba people and West Africa.

Along this vital celebration, revolutionary activism manifested itself. In “Lituation” (2018), South Africa’s Lungiswa Gqunta set out petroleum-filled beer bottles inside a greenhouse full of exotic plants. The project hinted at littering, but also deployed relics (ready—mind that—to be used once again) from the histories of struggle and resistance.

Launched in 2002 in Cape Town by Ntone Edjebe, Chimurenga functions as a printed magazine (the “Chimurenga Chronic”), a meeting point and space for discussion, a radio station, as well as in several other forms; all of them embrace the multiplicity and diversity of voices from Africa. The project can be seen as an interdisciplinary mechanism for the creation of alternative knowledge about the intensity of Africa’s reality. In order to formulate new questions and develop new analytic tools at Manifesta, Chimurenga set up office in Palermo temporarily and produced a special issue of “The Chronic.” Writings contained therein revolved around the conflict between Western concepts of sovereignty and selected African notions of borderlessness (

Chimurenga 2018).

The migratory theme received its most extensive and spectacular treatment so far in the 60th Biennale in Venice: “Foreigners Everywhere/Stranieri Ovunque.” The Brazilian artistic director Adriano Pedrosa noted that the edition’s central term, “stranger,” may refer both to migration and to those parts of art history which have not been admitted to the canon. The motto came from Claire Fontaine, a collective that relocated from Paris to Sicily (

Figure 5). Their installations, spread throughout the exhibition, were simple neon signs repeating the title phrase in several dozen different languages of the world. One could feel the raw power of a cliché as it burned itself into the minds of thousands of visitors, reiterating the notions of quantitative domination and perceived threat (

Pedrosa 2024).

The show drew on modernist history, presenting works created throughout the 20th century that have to do with the avant-garde language of deformation and distortion. Artists classified as Global Southern, entirely alien to the major narratives of the “global” art history, have developed their own codes of artistic representation, becoming classics regionally. Certain examples of portraiture or abstraction do ring a bell, perhaps—but how many of us know about Morocco’s Casablanca School, or recognise the excellent 1962 oil painting “The Dancer” by Nigeria’s Ben Enwonwu? (1917–1994) The latter introduced us to the realm of African masquerade ceremonies and the ritual of Agbogho Mmuo, performed to celebrate maiden spiritualities. Colour-wise, the work does justice to the vivid palette of the South; formally, it disintegrates the viewer’s perception of reality. Or, who remembers the South African painter Maggie Laubser? (1886–1973) Her “Meidjie” (undated) could spark a remarkable discussion of psychological dimensions of portrait painting.

Another work to single out deservedly was the film “We Were Here” (2024) by Fred Kuwornu, a Black Italian from Ghana who approaches his migrant status as something permanent. He examined the appearances of Black people in 15th- and 16th-century European art. Wondering who they were exactly—those Africans living in Florence, Rome, and other important centres of the Renaissance—Kuwornu found that these are not only likenesses of servants and slaves: there were princes with distinctive Black features, and ambassadors, and clergymen as well.

In his influential essay titled “The Artist as Ethnographer,” Hal Foster recognised the rise of interdisciplinary methodologies in the contemporary artistic research on otherness (

Foster 1995). It was in this way that the artists featured at the 60th Biennale di Venezia—their descent genuinely foreign, their identities most diverse—reconfigure our biased knowledge.

3.4. The Carnival, Exploding: Documenta 15

Foster noted that artists, by testing otherness increasingly, made ethnographers jealous. The former made practice and theory one as they undertook field work, acting as observers and participants rather than creators (

Foster 1995), and I consider documenta 15 (2022) to have played an important part in this process.

That edition marked the first time in the exhibition’s history that artistic direction was entrusted to a group (as opposed to a single curator): Ruangrupa, an Indonesia-based collective operating in Jakarta since 2000. Their community functions as a peculiar ecosystem where each member has a role to perform in order to maintain an overall equilibrium within. As a strategy, this breaks away from Western individualisms of curators and artists, fostered so that their personal brands grow—hopefully enough to be included among those whose views count in the art world. The fifteenth documenta mediated the term

lumbung: Indonesian for “rice barn”, i.e., the place where villagers stock their crops. The barn is owned collectively, with everybody contributing as much as they can. Metaphorically, it means collective action aimed at producing commonly shared value (

Ruangrupa 2022).

The festival featured various collectives whose primary activity consists of working with local communities; whose main concern is to challenge the status quo, whose methods are based on participation, and whose ultimate goal is utility. This stressed the kind of narratives—vital to the artists involved—that transcend pure artistic reflection by becoming acts of social practice. Surely, translating their projects into an exhibition-wise format is not easy, regardless of one’s attitude to tradition. Extremely detailed infographics, information booths, common areas, talks, and documentations replaced the more conventional artistic objects. It was a revolutionary move, one that provided a platform for the negotiation of Africa’s contemporary art and culture.

That year’s intervention in Documenta Halle seemed particularly significant. The building, designed by Jourdan and Müller as an extension to the festival’s exhibition space, opened in 1992, for the ninth edition. Today, it stands as a postmodern monument of elitist architecture—and the installation transforming its entrance in 2023 contradicted that code altogether. Titled “Killing Fear of the Unknown” (2022), it was a sheet metal tunnel leading to the exhibition hall, resembling the rural structures of the Maasai, in East Africa (

Figure 6).

Manyatta, as the natives call them, are constructed by local women, from whatever they find suitable; aesthetically, the building material hinted at African slums. As with Mahama, what made this rendition powerful was its physicality, ruining the splendour of its surroundings.

Since 2004, originators of this structure—Wajukuu Art Project—have been active in Nairobi’s (Kenya) slum of Lunga Lunga. By encouraging the local community to create art, they give children and young people—who otherwise mostly penetrate the nearby industrial dump—a chance to speak up about the injustice that they face. Wajukuu conduct workshops, run a library, provide space for activities as well as advice on matters such as conflict resolution, health, or conscious parenting. They initiate processes that promise to fight poverty and keep youngsters from engaging in criminal activity.

Nairobi was also the birthplace of the interdisciplinary Nest Collective, who work with film, fashion, and literature, among other media. The artists set up a fund called HEVA, for the support of creative entrepreneurship. Nest’s activity usually revolves around African experiences of urban space, often countering the littering of cities. Their installation “Return to Sender—Delivery Details” (2022), made from worn clothes, annexed a section of the elegant park outside the 18th-century orangery (

Figure 7).

Another project, “The Black Archives,” collected documents, books, photographs, and other artifacts linked to the history of colonialism, slavery, liberation, and emancipation of people of African descent in the Netherlands. The group behind the collection intends to inspire artistic and literary activity in Black contexts. Their presentation in Kassel, covering a part of that archive, was meant to nurture collective action around memory and human rights.

All of the initiatives discussed here approach the art world’s establishment—its symbols, its celebrated prestige—critically and subversively. Deploying dirt and scrap in the ever-tidy streets and parks, they act against the German decorum of managing public space. They make one perceive the sceneries of artists’ homelands in the sterile conditions created for the maintenance of the cultural heritage of the West—and in doing so, they make it as clear as possible that there are darker, less comfortable worlds out there somewhere. It is, indeed, a carnival of documented violence—because the point is to experience the evidence on show, not just look at it, as is the case with typical ready-mades. Poor people’s rags, bundles, and rusty sheets are set in front of the viewers’ eyes by artists, but also given credibility and strength by the actual memory of the South contained within. European institutions become transmitters of works whose message and power come from localities far, far away.

No edition of documenta had ever received this much attention—countless commentaries tried to grasp the new, refreshed format. Minh Nguyen of “Art in America” highly appreciated the festival’s powerful account of how all sorts of resources of the Global South are abused and ruined by the Global North (

Nguyen 2022). Harry Burke of “Artforum”, having closely examined the projects on show and even reached a fairly enthusiastic conclusion, could not help but point out that all the noble intentions and ideas were washed away in the end by the lustre of Europe’s respectable institutions involved (

Burke 2022). Extracts from artistic criticism suggest that—as far as mega-exhibitions are concerned—looking for cracks and leaks is the thing to do; instead of taking offence at the imperfect and cruel system, one should keep an eye for alien narrations that seep through it. This kind of conflict is called for, promoting confrontation without concealment.

4. Conclusions

The festivals appearing here were never intended as reviews of African art—but they do represent the Global South increasingly, welcoming a variety of critical voices from postcolonial countries that retain their critical momentum. The situations initiated by African artists dismiss any definition of an exhibitable artistic object and, although radical in both form and content, are ultimately peaceful in their demands for historical revisions and restitutions. The practice in question is one of meticulousness as it reveals forgotten, withheld, or concealed facts preserved in international laws and trade agreements, or in the custom; this imbues artistic activity with pragmatism and utility, giving it an enormous advantage of telling difficult, problematic stories to audiences of hundreds of thousands.

Such pursuits, correlating with the general transformation of exhibition concepts, produce a multifaceted space of intentional collisions: between the colonisers and the colonised, between the dominant culture of the West and the marginalised parts of the globe, or even between viewers who expect traditional formulas of display and artists who set up information booths devoted to participatory projects taking place in distant countries. It is a paradiplomatic method of operating in an imperfect art world, aimed at amplifying the need to reconsider the Global North’s relations with Africa. As usual in circumstances like these, questions reasonably arise whether the intended goals are achieved or not; either way, the message is unambiguous and distributed widely.

As mega-shows become saturated with art from outside the Western enclave—a process brought about by Okwui Enwezor, who insisted on creating diasporic spheres—the institutions of contemporary art turn into spaces of confrontation more and more often. Their actors have already made several new arrangements: in 2017, documenta moved to the border of the Global South, relocating to the struggling city of Athens; five years later, the same festival—perhaps the most influential of them all—exhibited artifacts from the activities of utility-oriented collectives; the 2018 Berlin Biennale was founded on firm objections to colonial deals, demanding their undoing; and in the same year, the curatorial team of Manifesta 12 in Palermo argued convincingly that migration, as a condition, is not unique to human beings but rather natural to ecosystems at large. The list—of how the field of art defines its new qualities, anticipated and advocated by the Nigerian reformer—is likely longer, and keeps growing.

The quality of curatorial concepts depends on their credibility no less than it does depend on artistic effectiveness. During documenta 14, back in 2017 in Athens—economically shattered at the time—sceptical graffiti emerged, inquiring: “The Crisis of Commodity or the Commodity of Crisis.” This, too, was an instance of multidirectional polemics, only made possible by a certain open-mindedness on the part of the festival’s programming team. Along these lines, inclusion of radical African output can be a guarantee that the art on show will be authentically relevant to the time and place of its presentation. Chances are that works like that—instead of being displayed as colonial loot—will be perceived more than ever as an actual contribution to the repair of today’s unstable reality. The globalised, capitalist dimensions of a mega-show, where ethical efforts often end up producing nothing more than a cynical spectacle, can be outplayed by critical and participatory projects from the Global South.