Food Labels as Media and Artistic Artifacts—A Case Study of Muszynianka Water Labels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Media Archaeology

- Materiality. This means that it emphasizes the physical and technical aspects of media—their equipment, infrastructure, materials, and technological processes (Ernst 2012; Parikka 2012). In this view, media are not neutral channels, but material entities whose structure and properties actively shape communication. Wolfgang Ernst (2012) speaks of the “techno-logos” of media, their internal logic resulting from their construction. According to him, the materiality of the medium itself has the capacity to act.

- Non-linearity/anarcheology. In this approach, media archaeology rejects the idea of simple, linear progress in media history (Parikka 2012; Zielinski [2002] 2010). It explores the “deep past” of media. In doing so, it draws attention to turning points, discontinuities, alternative paths of development, and forgotten possibilities (Zielinski [2002] 2010). Siegfried Zielinski ([2002] 2010) proposes “variantology”—the search for different variants instead of a single line of development—and “an-archeology”—the rejection of the search for a single source (arché). It is about discovering the “new” in the “old.”

- Ephemerality and forgetting. Media archaeology also draws attention to transient, disposable, rapidly aging, and forgotten media (Huhtamo and Parikka 2011). Of key importance is the study of so-called “losers,” “dead ends,” and the aging of technology (Parikka 2012). Jussi Parikka (2012), in turn, speaks of “zombie media” that return in new contexts.

- Archive (l’archive). According to Ernst (2012), an archive is not only a collection of documents but, above all, a system of operating principles, technical standards, and algorithms that underlie the functioning of media at a given time. It is the technical and logical foundation of the media system.

- The influence of Foucault and Kittler: Media archaeology has its roots in the thinking of Michel Foucault (archaeology of knowledge, discursive formations, power/knowledge relations) (Parikka 2012; Zielinski [2002] 2010). Friedrich Kittler (1985) complemented this perspective by emphasizing the decisive role of technology in shaping discourses and subjectivity. According to him, “media determine our situation.”

2.2. Label as a Media Artifact and Art Artifact

Labels created in the interwar period constitute a multidimensional record of the everyday reality of those times. They are examples of multimodal communication using two different semiotic systems: text and image. The visual layer with a persuasive function dominates in the communication of labels, affecting the emotional sphere of the recipient. Visuality is communicated through text typography and image composition. The contextual connections in the image, textual, and functional layers of labels are so multifaceted that a crystal structure seems simple in comparison. For this reason, labels have enormous research potential. Their multidimensionality in terms of content, form, and function requires an interdisciplinary approach and perspectives covering linguistics, design, art history (iconography and iconology), marketing, and communication. Some of these disciplines have defined a common research perspective, namely, the relationship of text with other co-occurring semiotic systems, primarily the visual system.

3. Case Study: Visual Evolution of Muszynianka Water Labels

3.1. History and Present of the “Muszynianka” Brand

3.2. Analysis of Visual Evolution of Labels

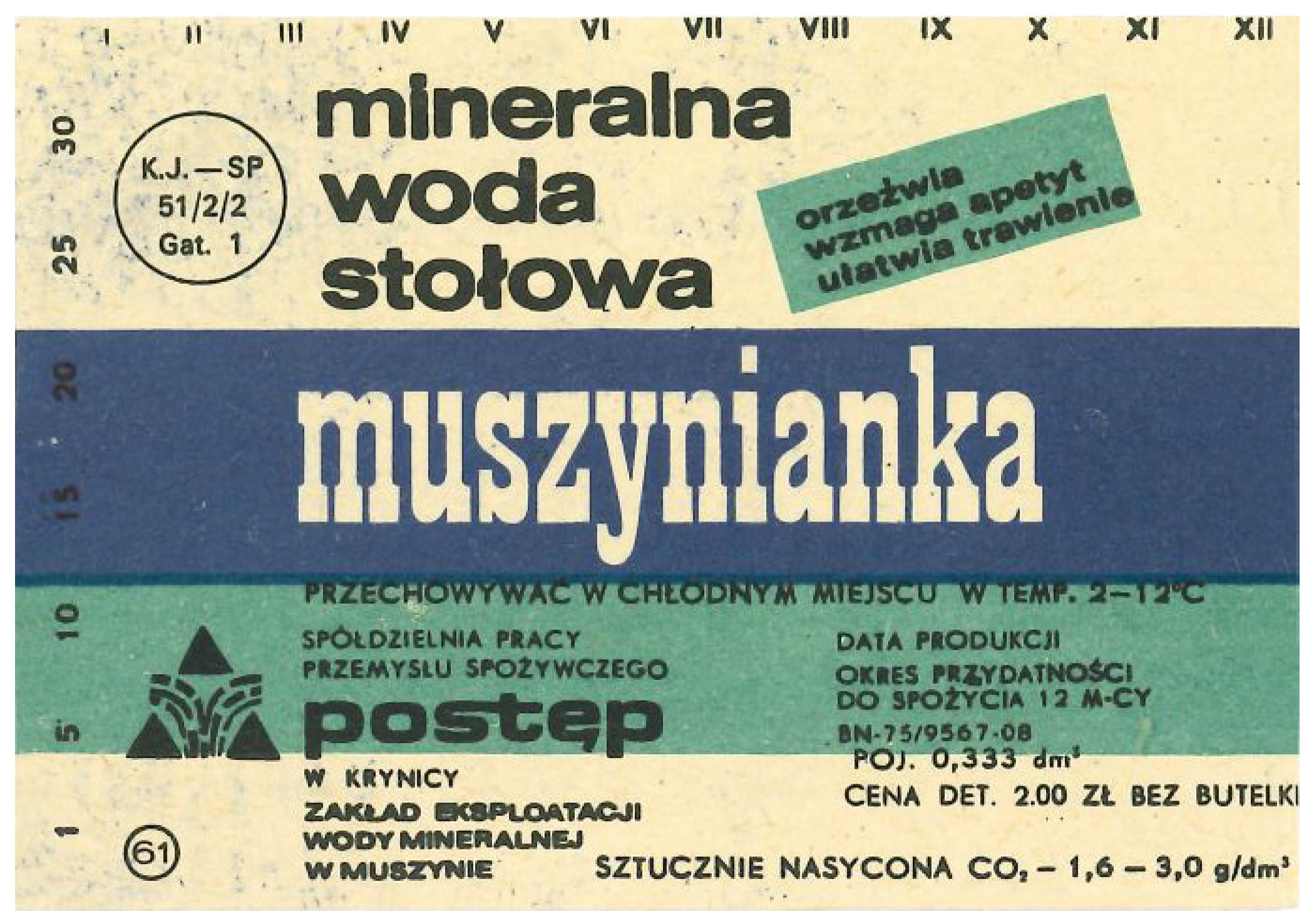

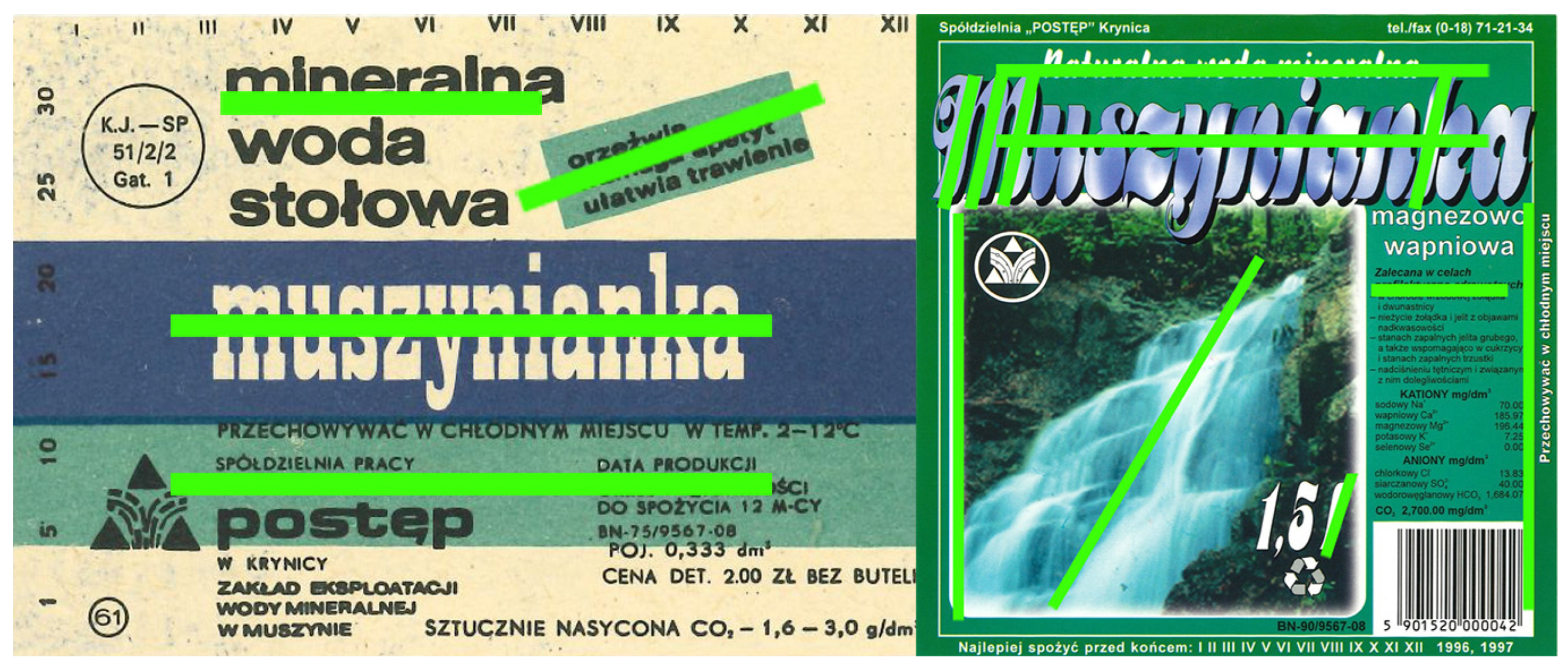

3.2.1. Early Period: Simplified Geometry and Technical Limitations

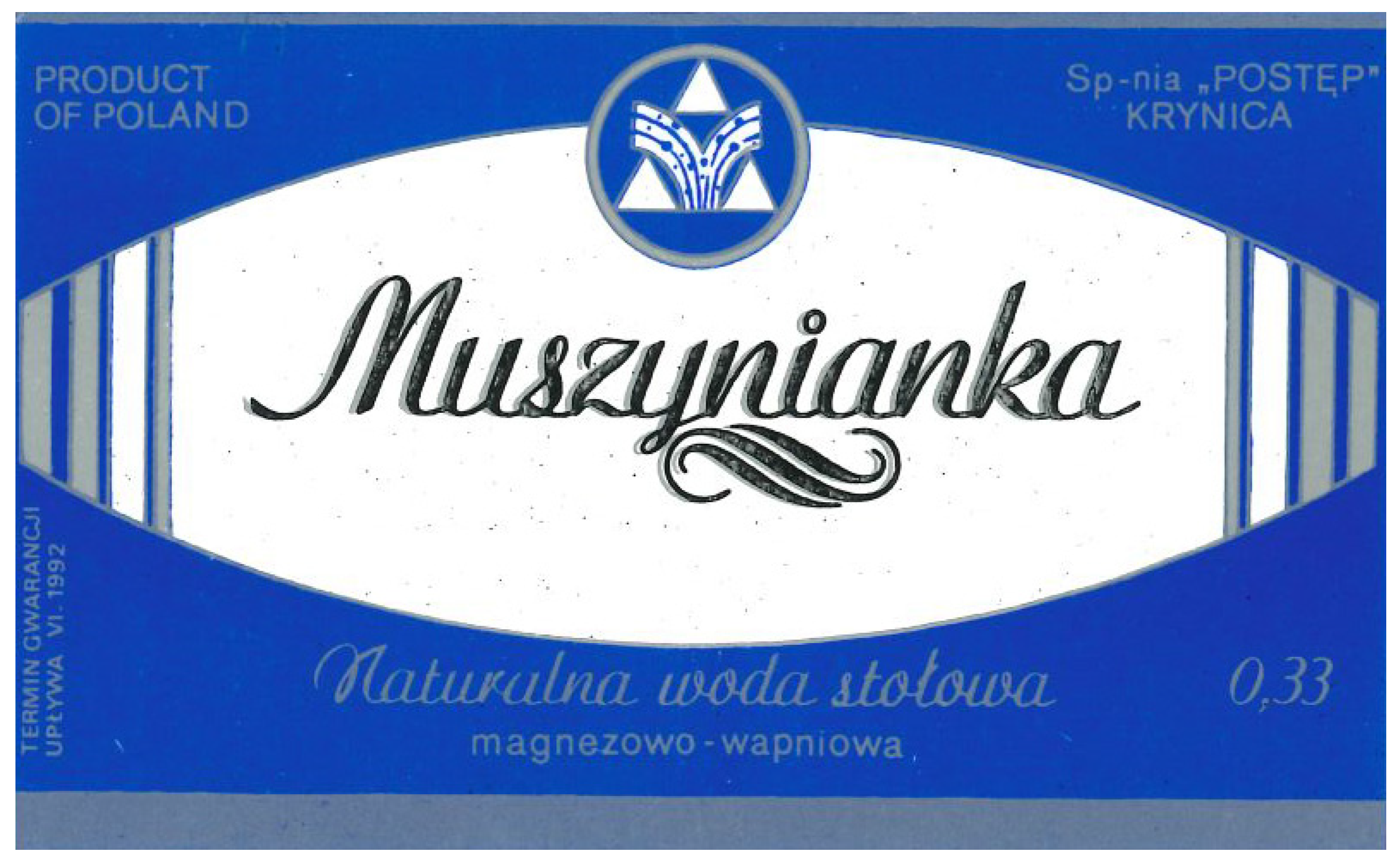

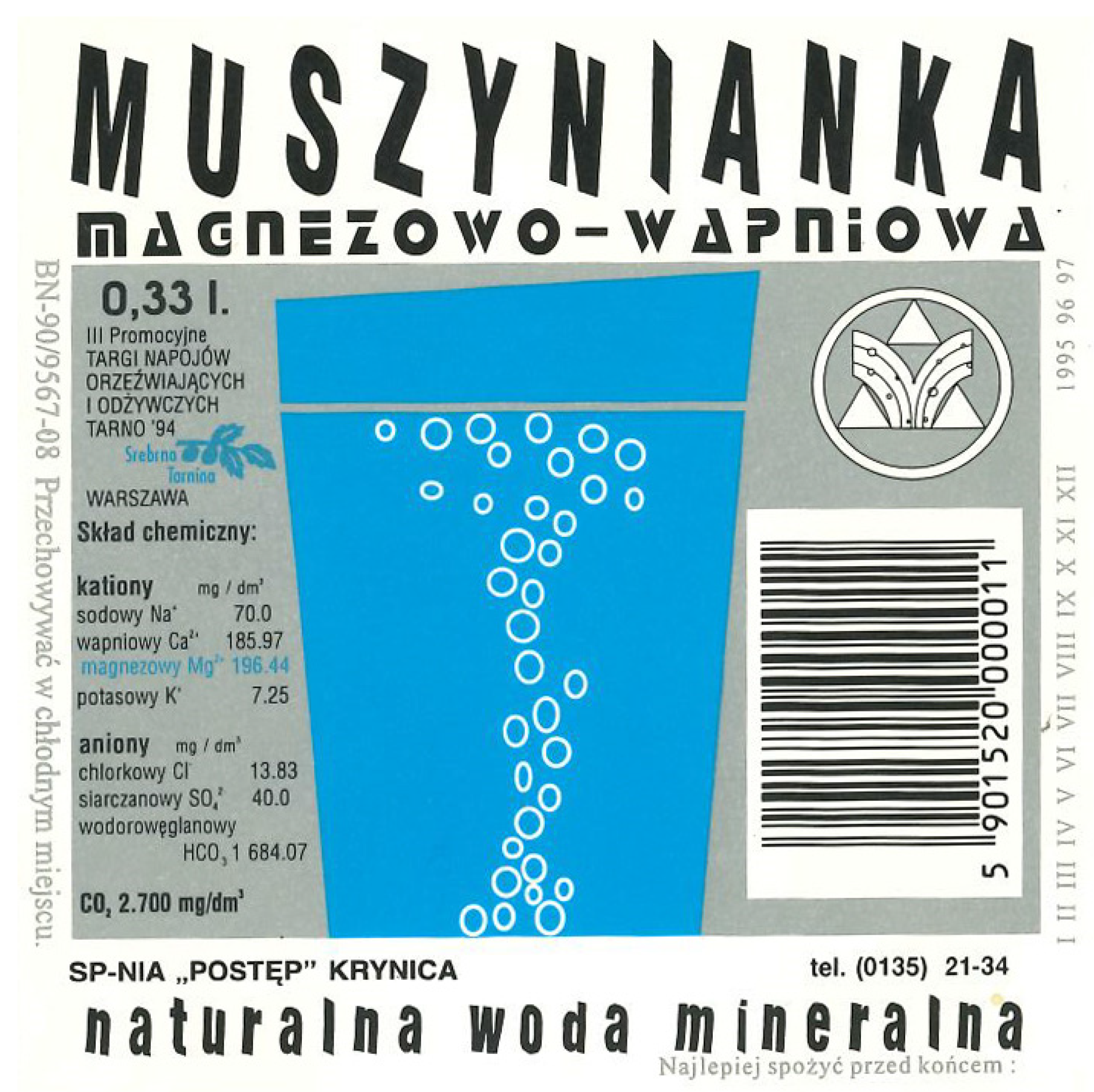

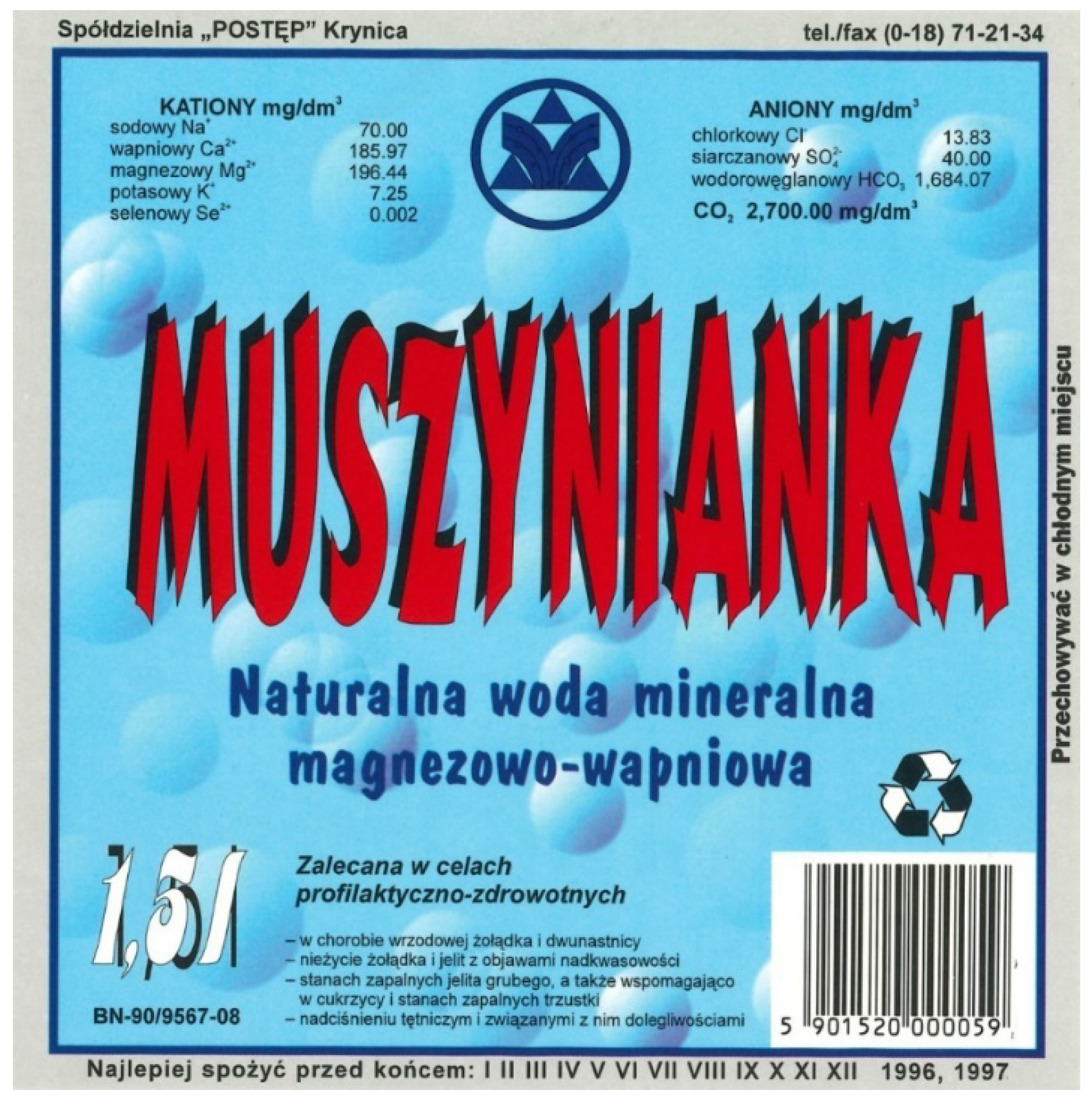

3.2.2. 1990s: Market Experiments and Search for Identity

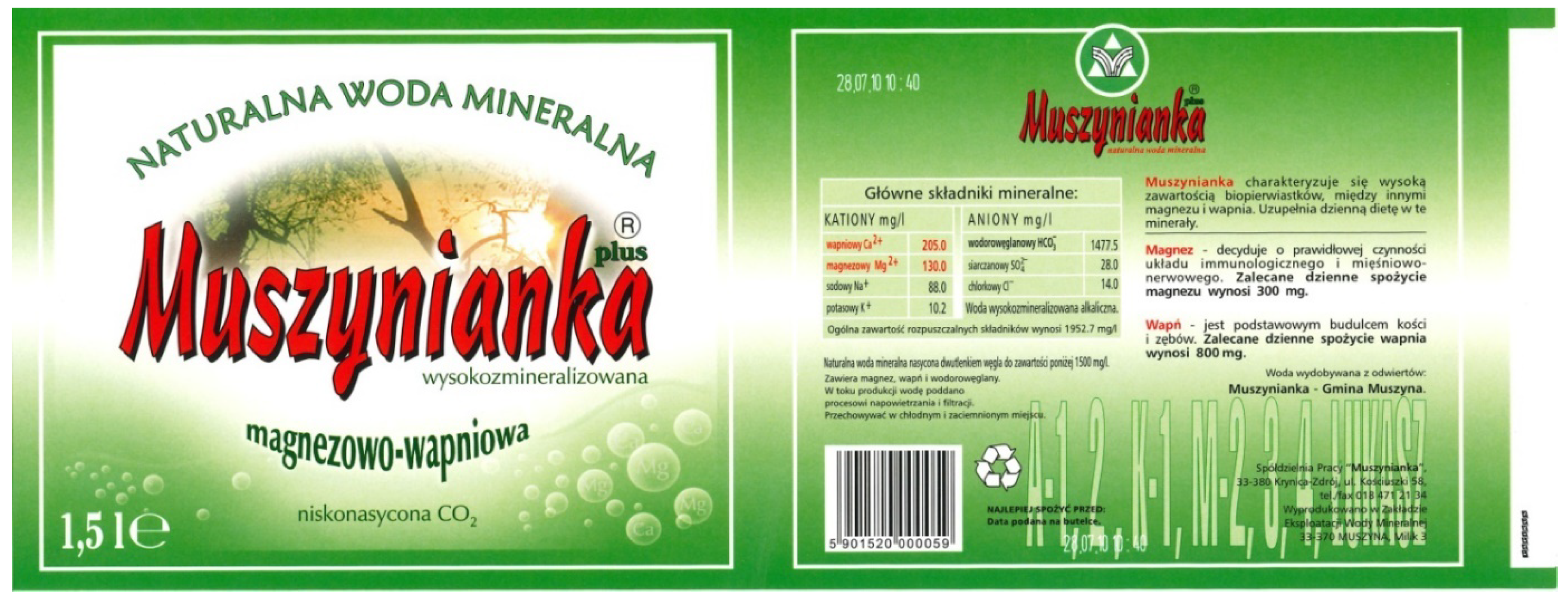

3.2.3. 2000s: Continuation and Overload

3.2.4. 2010s: Turn Towards Minimalism

4. Technical Analysis of Visual Communication of Muszynianka Mineral Water Labels

- Simplified geometric form of label—years xxx, 1995;

- Lettering forms—year xxx, 1997;

- Labels with photographic elements—1996, 2006, 2008; labels from the late 1990s depicting natural magnesium–calcium mineral waters;

- Labels with illustrative elements—xxx and 2016;

- Gradient forms or blurs—1998–2016.

4.1. Color Analysis

4.2. Shape and Form

4.3. Themes and Narratives of Muszynianka Labels

4.4. Composition

- Closed compositions—years xxx, 1992, 1995, 1997, 2011, 2013. In each of these cases, graphic and typographic elements are closed in space, and all are presented in their entirety.

- Closed compositions with elements of open composition—1996, 1998, 1999, 2005, 2006, 2016. The composition structure is essentially closed, but some elements, such as photos or illustrations, suggest that a fragment of the presentation is beyond the frame boundary.

4.5. Typography and Hierarchy Applied in Labels

- Xenotypes (mono-stylized styles applied in the product name);

- Sans-serif typefaces (Grotesques, Neo-Grotesques, Geometric typefaces, Humanist typefaces).

- Xenotypes (mono-stylized styles applied in the product name, in the words naturalna woda mineralna—here we encounter the same typeface. Additionally, in the words magnezowo-wapienna another typeface from this category appears);

- Sans-serif typefaces (Grotesques, Neo-Grotesques, Geometric typefaces, Humanist typefaces);

- Serif typefaces (Baroque Antiquas).

- Xenotype (in the product name, reminiscent of the typographic style of the 1970s);

- Sans-serif typefaces (Grotesques, Neo-Grotesques, Geometric typefaces, Humanist typefaces);

- Serif typefaces (Baroque Antiquas);

- Script/calligraphic typeface (applied in the words Naturalna woda mineralna).

- Xenotype (in the product name and in the product capacity marking 1.5 L. Interestingly, in this case we observe duplication of content in two different typefaces, which presumably result from printing errors);

- Sans-serif typefaces (Grotesques, Neo-Grotesques, Geometric typefaces, Humanist typefaces);

- Script/calligraphic typeface (applied in the words Naturalna woda mineralna).

- Script/calligraphic font (in the product name);

- Sans-serif typefaces (Grotesques, Neo-Grotesques);

- Serif typefaces (Baroque Antiquas).

- Script/calligraphic font (in the product name);

- Serif typefaces (Baroque Antiquas).

- Script/calligraphic font (in the product name);

- Serif typefaces (Baroque Antiquas).

- Script/calligraphic font (in the product name);

- Serif typefaces (Baroque Antiquas).

- Script/calligraphic font (in the product name);

- Serif typefaces (Baroque Antiquas).

4.6. Rhythm in the Work and Perspective

4.7. Chiaroscuro and Light

4.8. Dimensions and Shapes of Labels

4.9. Series of Labels on Glass Bottles

4.10. Visual Changes to the Logo on the Label

5. Analysis of Topoi on Muszynianka Labels

5.1. Methodology of Topoi Analysis

- Identification of potential topoi. Based on visual and contextual analysis (product type), the authors initially identified recurring, significant visual and narrative motifs on Muszynianka labels.

- Operationalization. For each topos, specific visual and textual indicators were determined, which allow for its recognition (e.g., for the “Nature” topos: images of mountains, green/blue color, keywords such as “spring”).

- Diachronic analysis. The authors analyzed the occurrence and method of realization (variations) of topoi on labels from different periods (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19), analyzing changes in form and meaning.

- Interpretation. The authors attempted to interpret the meaning and function of topoi in brand communication and their relationship with cultural trends.

5.2. Identified Topoi on Muszynianka Labels

5.2.1. Topos of Nature/Mountain Origin

- Operationalization: Images/illustrations of mountains, landscapes, water; dominance of green and blue colors; keywords related to nature.

- Analysis: Almost absent at the beginning (Figure 1 and Figure 2), appears clearly from the mid-1990s (Figure 3 and Figure 4) and becomes dominant from the late 1990s (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19). Realized through visual representations and green coloring. Communicates natural origin, purity, health. Evolves from literal photography to stylized illustration.

- Interpretation: In Western culture, mountains symbolize purity, primitiveness, majesty, and a source of unpolluted water. The Muszynianka brand seems to consciously position its product in this context. It thus appeals to deeply rooted human desires, related to authenticity and naturalness in a world that is becoming increasingly industrialized and polluted1. The image of mountains becomes a semiotic sign (de Saussure 1991; Barthes 2000) whose significance (signifié) is not only a specific landscape but, above all, connotations of purity, health, and natural mineral wealth. The green color strengthens this connection, symbolizing nature, growth, freshness, and potentially also ecology (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006; Itten 2015). The evolution from literal photography to stylized illustration in later labels may reflect a change in aesthetics towards greater symbolization and minimalism, but the core of the topos—natural, mountain origin as a guarantee of quality—remains unchanged. It is a key element of the marketing strategy, distinguishing mineral water from ordinary drinking water.

5.2.2. Topos of Health/Vitality/Purity

- Interpretation: This topos responds to growing social health awareness and the “wellbeing” trend. Mineral water is positioned as a healthy alternative to other beverages. The white background in newer labels (Figure 13 and Figure 14) communicates not only purity in the literal sense (lack of contaminants) but also simplicity, honesty, and transparency of the brand (Sprinkle 2019). The presentation of mineral composition, although legally required, becomes an element of health rhetoric, providing “scientific” evidence for the benefits of drinking Muszynianka. Minimalist design (Figure 13 and Figure 14) strengthens this message, suggesting a product that is uncomplicated, natural, devoid of unnecessary additives. The visual purity of the label becomes a metaphor for the purity of the product itself. It is a response to consumers’ search for products that support a healthy lifestyle and give a sense of control over what they consume.

5.2.3. Topos of Modernity/Technology

- Operationalization: Modern, sans-serif typefaces; digital techniques (gradients); minimalist design.

- Analysis: Realized mainly through stylistics. Gradients in the 90s/2000s (Figure 4, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19) communicated technological modernity. Current minimalism (Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19) fits into the contemporary understanding of modern aesthetics. There is an interesting connection with the Nature topos—modern design communicates a natural product.

- Interpretation: This topos introduces an interesting tension with the Nature topos. Although the product is natural, its packaging and visual communication use codes of modernity. In the 90s/2000s, this could signal the technological advancement of the company, professionalism, and ability to compete in a modern market. Gradients and photography could also add dynamism. Contemporary minimalism (Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19) communicates a different kind of modernity: elegance, sophistication, clarity of information, and perhaps compliance with digital aesthetics. Modern design becomes here a sign of quality, reliability, and attention to detail, which indirectly strengthens trust in the product. Through this topos, the brand shows that it is up to date with trends and expectations of the contemporary consumer.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Interpretation based on cultural analysis of the meanings of nature, see, e.g., in the context of food packaging (Brucks 2017). |

| 2 | The concept of performative texts, which “do” something in culture, rather than just describe it, derives from speech act theory (J. L. Austin) and was developed in cultural and performative studies (e.g., Judith Butler). Here, it is applied to labels as artifacts shaping attitudes and definitions. |

References

- Barthes, Roland. 2000. Mythologies. Translated by Adam Dziadek. Warsaw: KR Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarz Doiczmanowa, Ewelina. n.d. Images of Ships on Alcohol Labels. Applied Art as a Tool for Preserving History, Unpublished manuscript.

- Bergstrom, Bo. 2009. Visual Communication. Warsaw: PWN Scientific Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- BizRaport. 2025. MUSZYNIANKA SP. Z O.O. KRS: 0000800687. Available online: https://www.bizraport.pl/krs/0000800687/muszynianka-spolka-z-ograniczona-odpowiedzialnoscia (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Brucks, Kerstin. 2017. ‘Nothing added, nothing taken away’—Or laboratory-made naturalness? The semiotics of food product packaging in Germany in the 1990s and today. International Journal of Food Design 2: 203–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Saussure, Ferdinand. 1991. Course in General Linguistics. Translated by Krystyna Kasprzyk. Warsaw: National Scientific Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- EMIS. 2025. “Muszynianka” Sp. z oo (Poland). Available online: https://www.emis.com/php/company-profile/PL/\_Muszynianka\_\_Sp_z_oo_pl_9350938.html (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Ernst, Wolfgang. 2012. Digital Memory and the Archive. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homolacs, Karol. 1927. Advertising and art. Beautiful Things 6: 82, (Cited in: Klugowska 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Huhtamo, Erkki, and Jussi Parikka, eds. 2011. Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Itten, Johannes. 2015. The Art of Color. Translated by Sławomir Figat. Krakow: D2D.PL. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiołek, Katarzyna. 2021. Packaging, or Perfuming Herring. About Graphics, Advertising, and Trade in the Polish People’s Republic. Warsaw: Marginesy. [Google Scholar]

- Kierunek Spożywczy. 2025. Muszynianka as the First to Enter Deposits! The Company Takes Responsibility for Its PET Packaging. Available online: https://www.kierunekspozywczy.pl/artykul,105513,muszynianka-jako-pierwsza-wchodzi-w-kaucje-firma-bierze-odpowiedzialnosc-za-swoje-opakowania-pet.html (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Kittler, Friedrich A. 1985. Aufschreibesysteme 1800/1900. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Klugowska, Anna. 2023. Discreet charm of everyday life. Labels of producers from Toruń and the region in the interwar period (based on the collections of the University Library in Toruń). Faces of Communication 15: 105–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Małopolska. 2025. “Visiting Muszynianka…” Marshal’s Office of the Małopolska Voivodeship. Available online: https://www.malopolska.pl/aktualnosci/biznes-i-gospodarka/z-wizyta-w-muszyniance (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Mila Muszyna. 2025. History—Mila Muszyna. Available online: https://milamuszyna.pl/historia-niezwyklego-uzdrowiska/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Muszynianka. 2025a. About the Company. Available online: https://muszynianka.pl/o-firmie/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Muszynianka. 2025b. Mineral Components. Available online: https://muszynianka.pl/skladniki-mineralne/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Muszynianka. 2025c. Muszynianka—Development Is the Basis! Available online: https://muszynianka.pl/muszynianka-rozwoj-to-podstawa/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Muszynianka. 2025d. Muszynianka Is Known Not Only in Poland. RP.pl. Available online: https://pro.rp.pl/abc-firmy/art12746601-muszynianka-jest-znana-nie-tylko-w-polsce (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Muszynianka. 2025e. Muszynianka—Modern Enterprise with Traditions. Available online: https://muszynianka.pl/muszynianka-nowoczesne-przedsiebiorstwo-z-tradycjami/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Muszynianka. 2025f. Muszynianka—Stronghold of Tradition, Breath of Modernity. Be Healthy Magazine. Available online: https://behealthymagazine.abczdrowie.pl/muszynianka-ostoja-tradycji-powiew-nowoczesnosci,7141384801258336a (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Muszynianka. 2025g. Products. Available online: https://muszynianka.pl/produkty/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Myczkowska-Szczerska, Anna. 2018a. Designing Visual Information—Introduction. Krakow: Publishing House of the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. [Google Scholar]

- Myczkowska-Szczerska, Anna. 2018b. Number and Proportion in Visual Communication. Krakow: Publishing House of the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. [Google Scholar]

- Newark, Quentin. 2005. The Designer’s Lexicon: The Illustrated Dictionary of Design, Printing, and Computer Terms. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. [Google Scholar]

- Parikka, Jussi. 2012. What is Media Archaeology? Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poprawa, Marcin. 2020. Word-image spaces in propaganda leaflets of 1918–1939. An attempt at analysis in the light of textual linguistics and theory of visuality. The Art of Editing. Textual and Editorial Studies 1: 203–30, (Cited in: Klugowska 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Gilian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rypson, Piotr. 2011. Not Geese. Polish Graphic Design. Warsaw: Karakter, (Cited in: Klugowska 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Sprinkle, David. 2019. The ‘Clean Label’ Trend—Has It Peaked? Progressive Grocer. May 16. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://progressivegrocer.com/clean-label-trend-has-it-peaked (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Superbrands. 2025a. Muszynianka Is a Natural Mineral Water Extracted from Intakes Located in the Poprad Landscape Park in Mu. Available online: https://superbrands.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/052-053_Muszynianka.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Superbrands. 2025b. Muszynianka Is a Natural Mineral Water Extracted in Muszyna and Surroundings, from Intakes Located in the Poprad P. Available online: https://superbrands.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Superbrands19-29.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- The European Parliament. 2011. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers, Amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004. Official Journal of the European Union L 304: 18–63. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=celex:32011R1169 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Tilgner, Damazy Jerzy. 1935. Labels, Design and Evaluation, Warsaw, (Cited in: Klugowska 2023).

- WODA24. 2025. Muszynianka—Krakow—WODA24. Available online: https://www.woda24.pl/muszynianka (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Zakrzewski, Stanisław Z. 1937. Guide to the Use of Advertising, Warsaw, (Cited in: Klugowska 2023).

- Zielinski, Siegfrid. 2010. Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means. Translated by Gloria Custance. Cambridge: MIT Press. First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Year of Production | Height | Width | Number of Label Parts on the Packaging | Shape |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| xxx | 61 mm | 87 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 1991–1992 | 62 mm | 102 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 1995 | 90 mm | 90 mm | single-element label | Square |

| 1996 | 129 mm | 131 mm | single-element label | Minor irregularities may result from label trimming during production. Nevertheless, the label should be classified as square in shape. |

| 1997 | 130 mm | 130 mm | single-element label | Square |

| 1998 | 127 mm | 287 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 1999 | 130 mm (front and back) | 120 mm (front and back) | two-element label | Rectangle |

| Late 1990s—no precise date in company archives | 127 mm | 287 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| Late 1990s—no precise date in company archives | 127 mm | 287 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2003 | 132 mm (front and back) 45 mm (section at the upper part of the bottle) | 124 mm (front and back) 85 mm (section at the upper part of the bottle) | three-element label | Rectangle approaching square, and upper section of irregular shape |

| 2004 | 124 mm | 267 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2005 | 110 mm | 285 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2006 | 110 mm 25 mm (strip placed in the six-pack) 39 mm (section at the upper part of the bottle) | 229 mm 210 mm (strip placed in the six-pack) 80 mm (section at the upper part of the bottle) | three-element label | Two rectangles (label on the bottle and strip on the plastic packaging for the six-pack of bottles), upper section of irregular shape |

| 2007 | 110 mm | 290 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2009 | 110 mm | 290 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2011 | 110 mm 25 mm (strip placed in the six-pack) 37.5 mm (section at the upper part of the bottle) | 292 mm 210 mm (strip placed in the six-pack) 76,5 mm (section at the upper part of the bottle) | three-element label | Two rectangles (label on the bottle and strip on the plastic packaging for the six-pack of bottles), upper section of irregular shape |

| 2016 Large bottle, green label | 104 mm | 282 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2016 Large bottle, blue label | 104 mm | 282 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2016 Small bottle, green label | 56 mm | 216 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2016 Small bottle, blue label | 56 mm | 216 mm | single-element label | Rectangle |

| 2025 Glass bottle 0.7 L, blue label | 94 mm | 79.7 mm upper section 170 mm lower section | single-element label | Irregular shape resembling the surface of a truncated cone |

| 2025 Glass bottle 0.7 L, green label | 94 mm | 79.7 mm upper section 170 mm lower section | single-element label | Irregular shape resembling the surface of a truncated cone |

| 2025 Glass bottle 0.33 L, blue label | 78.2 mm | 94.7 mm upper section 163 mm lower section | single-element label | Irregular shape resembling the surface of a truncated cone |

| 2025 Glass bottle 0.33 L, green label | 78.2 mm | 94.7 mm upper section 163 mm lower section | single-element label | Irregular shape resembling the surface of a truncated cone |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Longawa, P.; Adamski, A.; Wiśniowski, J. Food Labels as Media and Artistic Artifacts—A Case Study of Muszynianka Water Labels. Arts 2025, 14, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050122

Longawa P, Adamski A, Wiśniowski J. Food Labels as Media and Artistic Artifacts—A Case Study of Muszynianka Water Labels. Arts. 2025; 14(5):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050122

Chicago/Turabian StyleLongawa, Patrycja, Andrzej Adamski, and Jacek Wiśniowski. 2025. "Food Labels as Media and Artistic Artifacts—A Case Study of Muszynianka Water Labels" Arts 14, no. 5: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050122

APA StyleLongawa, P., Adamski, A., & Wiśniowski, J. (2025). Food Labels as Media and Artistic Artifacts—A Case Study of Muszynianka Water Labels. Arts, 14(5), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050122