At Home in Chinatown: Community-Based Art Activism and Cultural Placemaking for Neighborhood Stabilization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Learning from Boston’s Chinatown

3. Case Study Design and Overview

4. ResLab: Partners, Program, and Procedures

4.1. Partner Organizations

4.2. ResLab Program

4.3. Procedures

4.4. ResLab Projects: Four Case Examples

4.4.1. 2019 Oasis: A House Shaped Dream

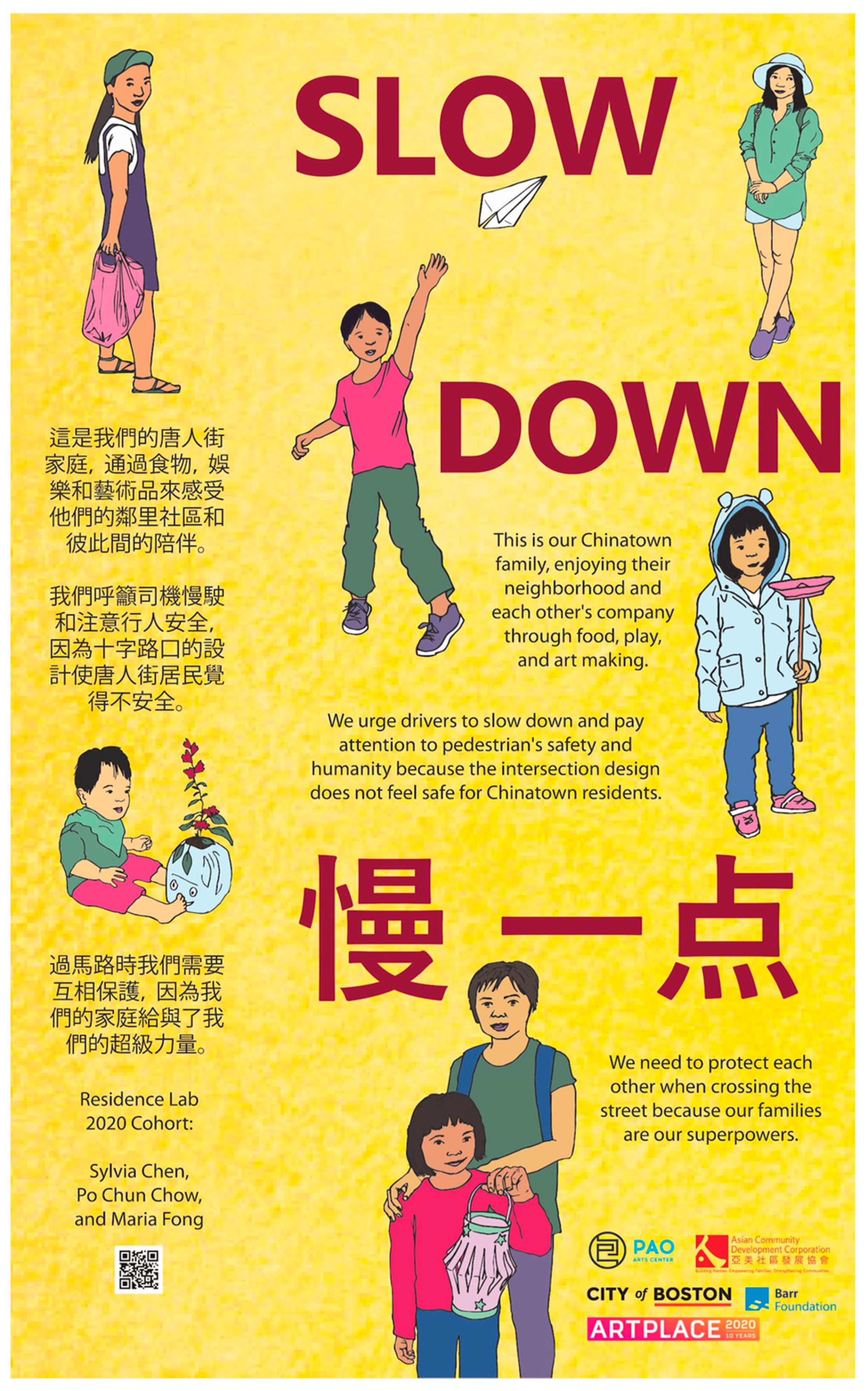

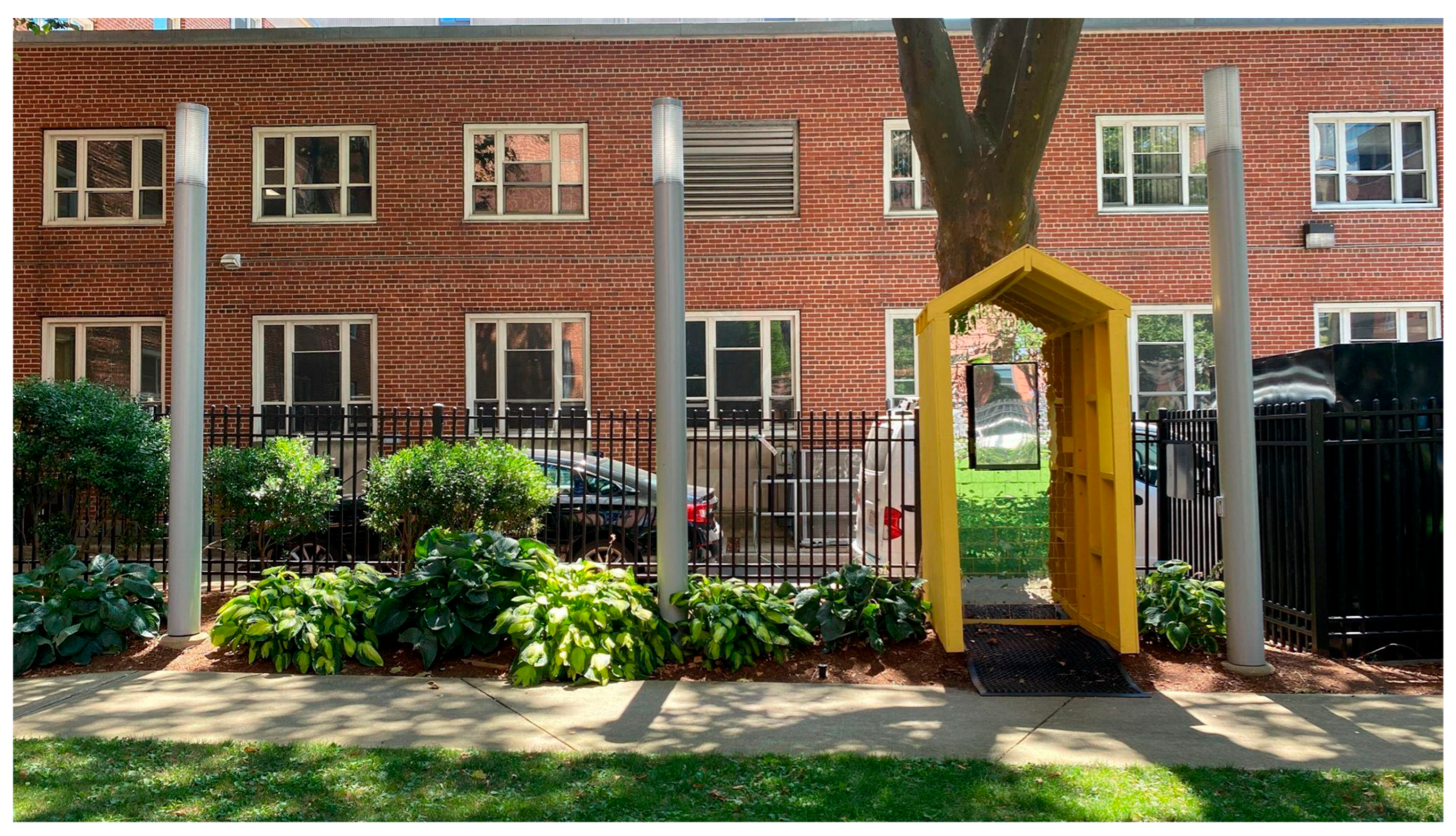

4.4.2. 2020 Portal: Slow Down for Chinatown

4.4.3. 2021 Collective Care: Abundance Among Us

4.4.4. 2022 Radical Inclusion: Welcome Home

4.5. Participant Perspectives on ResLab

When I go there, every time they invite a guest and then the guest will give us inspiration and teach us how to think, the pathway, and how to create. Before I didn’t know I could create. Now after that, I have some artist mind, too. I can think too like an artist. I used to think I wasn’t an artistic person. I have so much fun.

When I say sense of community, I don’t just mean Chinese people or Asian people. It’s a community on my hall, and it’s a melting pot, just like the rest of the city of Boston. In the beginning I may see them as outsiders, but then the more I see them, it’s like, they’re part of my community. They’re not outsiders anymore.

It turns out that there are still many people who will pay attention to this place, not just focus on development of the land. It turns out that there are people who still pay attention to the problems existing in Chinatown and listen to what the residents here want. If we promote Chinatown through literary and artistic exchanges, works of art, dance, and Cantonese music concerts, it would receive good reviews. Our project has promoted more people to pay attention to Chinatown.

I think it’s so important to have initiatives like ResLab that’s getting power back to people who actually live there and work there and have lived there for a long time and have built it into the community. It is giving them the power to say this is what we want and this is what we want to see and this is what we want back.

I’m more critical of what public art is…I think one part is empowerment for the people participating in it…that they believe they can change what their neighborhood looks like…giving them a feeling of responsibility and agency that they can also show up to make change.

It was very transformative… totally shifted the direction of my art practice…It really helped me understand and see the potential and what art can do…It changed what I thought I could do or be within an art practice. There’s so much possibility in collaboration and like different forms of collaboration…It was the first time I was really introduced to ideas like co-design or participatory art-making. Ideas of [placekeeping] were really impactful for me. I didn’t know that there was a way to think about art and how it can work together with other sorts of community advocacy efforts.

I really loved the experience. It pushed me beyond boundaries that I didn’t consider myself a community artist or a public artist. It pushed me to think of myself in that way and take on that role…It really solidified the ways that art and imagination work can have on policy, land ownership, and a feeling of belonging within the community.

So many artists that had been part of ResLab before are still so involved with the Chinatown community. It was especially cool to see them come back and help us find our way as new artists to the program, to like find our way through and to see what has been done before.

5. Concluding Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The population count is based on Chinatown Neighborhood Council boundaries and US Census figures for the American Community Survey. |

| 2 | The first wave of Chinese migration, from the late 19th century until World War II, was dominated by male laborers from Guangdong province. The second wave, which followed in the postwar era and exponentially expanded with immigration reform in 1965, largely came through Hong Kong. The end of the US wars in Southeast Asia triggered a third migration wave of Southeast Asians from the 1970s. As China loosened emigration restrictions, a fourth wave of migrant workers came from Fujian province from the 1980s, speaking Mandarin and Fuzhounese, in contrast to the Taishanese and Cantonese of earlier waves. Boston’s higher education and knowledge-based sectors also drew international students, scientists, and high-skill workers from China and other parts of Asia, many of whom settled in the suburbs and became routine visitors to Chinatown. |

| 3 | While the total population has increased by nearly 50% in the last decade, the white population has increased by more than 4 times the rate of the Asian population’s increase. There is a large and growing gap between the median household income for Asian residents (about $18k) and White residents (about $120k) in Chinatown. About 60% percent of households in Chinatown earn less than $35,000 a year. In addition, fewer families and children are living in the neighborhood (Northeastern-CCLT Capstone Project Report 2025). |

| 4 | CPA collaborators included Wen-ti Tsen, Chu Huang, Catalina Tang, Jennifer Lin-Weinheimer, Keith Francis, Pampi Thirdeyefell, Loreto P. Ansaldo, Maryann Colella, Andrea Zampitella, and Monica Mitchell. |

| 5 | The overall research question was: How can artists and residents work together on socially-engaged practices and art in a way that is truly co-created and collaborative? Data analysis applied the framework approach to identify themes and develop codes, and use charting and mapping to discern thematic patterns and relationships (Pope et al. 2000). |

| 6 | The BCNC is a social service agency with deep commitments to advancing cultural agency and self determination for individuals, families, and communities. |

| 7 | Additional benefits for residents included the chance to shape public art and culture in Chinatown, as well as to gain support from ACDC staff to further connect with the Chinatown community. Artists also benefited from access to shared collaborative meeting space at the Pao Arts Center and the ACDC during open hours, advisory hours with ACDC and Pao Arts Center staff, collaborative feedback sessions and workshopping clinics, and ACDC staff support to engage Chinatown residents and families and further connect with the Chinatown community and exhibit work in the Pao Arts Center after the residency. |

| 8 | Collaborators for Films at the Gate included Chinatown residents, film curator Jean Lukitsh, and Street Lab, as well as A-VOYCE youth, who eventually assumed a leading role in organizing Films at the Gate. |

| 9 | The 1965 South Cove Urban Renewal Plan harnessed the power of eminent domain to displace residents and facilitate university and hospital expansion from the late 1960s, fomenting considerable community protest and resistance (Liu 2020). |

| 10 | These include the Hudson Street Stoop, the Immigrant History Trail, and the R-1 Project Review Committee for the City of Boston. |

| 11 | The projects are (1) Phillips Square redesign, (2) Chinatown Streets—redesigning Kneeland Street, Washington Street, Essex Street, and Surface Road, and (3) Reconnecting Chinatown—feasibility study for reconnecting Chinatown across the open-cut Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90). |

References

- American Artscape. 2023. In Celebration of Artful Lives. A Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Available online: https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/2023-american-artscape-no1-rev.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Bedoya, Roberto. 2014. Spatial Justice: Rasquachification, Race and the City. Creative Time Reports, September 15. Available online: https://creativetimereports.org/2014/09/15/spatial-justice-rasquachification-race-and-the-city/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Cameron, Stuart, and Jon Coaffee. 2005. Art, Gentrification and Regeneration: From Artist as Pioneer to Public Arts. European Journal of Housing Policy 5: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinatown Atlas. 2025. Chinatown Atlas. Available online: https://www.chinatownatlas.org (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Chinatown Community Master Plan. 2020. Boston Chinatown Community Master Plan:Community Vision and Implementation Strategies. Boston: MAPC. [Google Scholar]

- Chinatown Cultural Plan. 2024. Available online: https://artsandplanning.mapc.org/cultural-planning-copy/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Courage, Cara, and Anita McKeown, eds. 2024. Trauma Informed Placemaking. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Courage, Cara, Tom Borrup, Maria Rosario Jackson, Kylie Legge, Anita McKeown, Louise Platt, and Jason Schupbach, eds. 2021. The Routledge Handbook of Placemaking. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett, Karilyn. 2018. People Before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eynaud, Philippe, Maïté Juan, and Damien Mourey. 2018. Participatory Art as a Social Practice of Commoning to Reinvent the Right to the City. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 29: 621–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, Richard. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, Richard. 2003. Cities and the Creative Class. City & Community 2: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florida, Richard. 2014. The Creative Class and Economic Development. Economic Development Quarterly 28: 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainza, Xabier. 2017. Culture-Led Neighborhood Transformations Beyond the Revitalisation/Gentrification Dichotomy. Urban Studies 54: 953–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodach, Carl, Nicole Foster, and James Murdoch. 2018. Gentrification, Displacement and the Arts: Untangling the Relationship between Arts Industries and Place Change. Urban Studies 55: 807–25. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26958507 (accessed on 29 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ho, Fred Wei-Han, and Man Chui Leung. 2000. Legacy to Liberation: Politics and Culture of Revolutionary Asian Pacific America. Chico: AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, Melissa. 2018. Luxury Developments, Gentrification, Airbnb: The Battle for Boston’s Chinatown. HuffPost, January 27. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/boston-chinatown-gentrification_n_5a6b05fae4b01fbbefb0b992 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Jackson, Maria Rosario. 2011. Building Community: Making Space for Art. New York: Leveraging Investments in Creativity (LINC). Available online: https://search.issuelab.org/resource/building-community-making-space-for-art.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Jackson, Maria Rosario, and Jen Hughes. 2024. Communities Deserve Creative Outlets: A Conversation between Chair Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson and Senior Advisor Jen Hughes of the National Endowment for the Arts on Artful Lives and Equitable Community Development. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Cultural Planning. Edited by Rana Amirtahmasebi and Jason Schupbach. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, Girija. 2022. The Expressive Instinct: How Imagination and Creative Works Help Us Survive and Thrive. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Zenobia, Andrew Leong, and Chi Chi Wu. 2000. Lessons of the Parcel C Struggle: Reflections on Community Layering. UCLA Asian Pac. Am. LJ 6: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, Loretta, and Martin Phillips, eds. 2018. Handbook of Gentrification Studies. Gloucestershire: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Andrew. 1995. The Struggle over Parcel C: How Boston’s Chinatown Won a Victory in the Fight Against Institutional Expansion and Environmental Racism. Amerasia Journal 21: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, George. 2007. The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race: Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape. Landscape Journal 26: 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, George. 2011. How Racism Takes Place. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Michael. 2020. Forever Struggle: Activism, Identity, and Survival in Boston’s Chinatown, 1880–2018. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Michael, Kim Geron, and Tracy AM Lai. 2008. The Snake Dance of Asian American Activism: Community, Vision, and Power. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, Lydia, and Daphne Xu. 2023. Boston Chinatown: Preserving Historic Character Through Cultural Placekeeping. Historic New England, Fall. Available online: https://issuu.com/historicnewengland/docs/hne.fall2023/s/45530708 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Markusen, Ann. 2006. Urban Development and the Politics of a Creative Class: Evidence from a Study of Artists. Environment and Planning A 38: 1921–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusen, Ann. 2014. Creative Cities: A 10-year Research Agenda. Journal of Urban Affairs 36 Suppl. S2: 567–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, Vanessa. 2010. Aestheticizing Space: Art, Gentrification and the City. Geography Compass 4: 660–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolitan Area Planning Council. 2025. Chinatown Master Plan 2020. Available online: https://www.mapc.org/resource-library/chinatown-master-plan-2020/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Montenegro, Arón. 2025. Muralism, Graffiti, and Gentrification in Los Angeles: Nuances of a Radical Imagination. Visual Arts Research 51: 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northeastern-Chinatown Community Land Trust Capstone Project Report. 2025. Sustaining Chinatown: Measuring & Fighting Displacement. Boston: Northeastern University. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, Catherine, Sue Ziebland, and Nicholas Mays. 2000. Analyzing qualitative data. BMJ 320: 114–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, Christopher John. 2023. Organizers Give Update on Chinatown Master Plan. Sampan, August 18. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Mark J., and Susan C. Seifert. 2017. The Social Wellbeing of New York City’s Neighborhoods: The Contribution of Culture and the Arts. The Culture and Social Wellbeing in New York City. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/46264 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Venable-Thomas, Meghan. 2018. Can Creative Placemaking Be a Tool for Building Community Resilience? Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Vrabel, Jim. 2014. A People’s History of the New Boston. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Lilian. 2023. Art, Repair, and Spatial Justice in Boston’s Chinatown and Seattle’s International District. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/152456 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Yanchapaxi, María Fernanda, Jade Nixon, and Eve Tuck. 2023. Consent practices in desire-based and beauty-affirming social science research. Feminist Review 135: 113–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, L.; Rubin, H.L. At Home in Chinatown: Community-Based Art Activism and Cultural Placemaking for Neighborhood Stabilization. Arts 2025, 14, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040095

Song L, Rubin HL. At Home in Chinatown: Community-Based Art Activism and Cultural Placemaking for Neighborhood Stabilization. Arts. 2025; 14(4):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040095

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Lily, and Heang Leung Rubin. 2025. "At Home in Chinatown: Community-Based Art Activism and Cultural Placemaking for Neighborhood Stabilization" Arts 14, no. 4: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040095

APA StyleSong, L., & Rubin, H. L. (2025). At Home in Chinatown: Community-Based Art Activism and Cultural Placemaking for Neighborhood Stabilization. Arts, 14(4), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040095