2. Generic Boundaries of Travel Writing

The travelogue is a very old genre of literary historiography.

3 As a variety of discourse representing critical historical importance, it gained popularity and grew in socio-cultural and political significance in Europe from the mid-18thcentury, although travelers had collected data and testimonies about unknown places since ancient times. The travelogue was “the most self-consciously print-informed genre of the period” (

Rogers 2009, p. 784) as it reflected cultural knowledge and consciousness based on observation and facts on the one hand and imagination and creativity on the other. In the 18th century, the travelogue had already become fundamental to the liberal understanding of the surrounding world (

Colbert 2012) and to the formation of a complex and objective vision of it. Travel literature also contributed to the development of individual and collective national identity (

Vlasta 2019).

Linguistically, or, to be more exact, from the point of view of functional stylistics,

4 travel writing as a genre of public discourse is based on the ontological juxtaposition or convergence of fact (to inform) and fiction (to impact). This juxtaposition is not simply a surface-level rhetorical device but is fundamental to the travelogue’s mode of knowledge production. In other words, the linguistic units/elements (lexical and phraseological choices)used in the travelogue realize their functional potentials (communicative purposes of informing and impacting the reader that underly stylistic choices), both on the semantic (referential) and meta-semiotic (connotational) levels of expression. Just as a travelogue follows its factitious conventions, it draws techniques from fiction in order to evoke the audience’s interest through crafting the first-person narrator. The narrator’s personal voice—shaped by imaginative language, style, and perspective—becomes the central tool through which experiences are framed, felt, conveyed, and communicated. Although facts and fictions are arranged in different ways, the genre authorizes itself only on the basis of the unity of fact and fiction.

In a similar vein, referring to the generic boundaries of travel writing,

Lisle (

2009, pp. 27–28) argues that at the heart of all travel writing is the combination of fact and fiction. The author claims that fact and fiction are two “competing authorities” that “cannot be divorced”.

Borm (

2004, p. 26) states that drawing generic boundaries and defining the status of travel writing and the terms used to describe it are problematic issues. He is, thus, doubtful of naming travel writing a “genre” at all, but he as well agrees that the travelogue is based on the ontological juxtaposition of fact and fiction and suggests that it be considered “a useful heading under which to consider and to compare the multiple crossings from one form of writing into another and, given the case, from one genre into another.”

Borm (

2004, p. 13) expresses a preference for contemporary writer Jonathan Raban, who has defined travel writing as a literary form, “a notoriously raffish open house where different genres are likely to end up in the same bed” (

Borm 2004, p. 13).Although they may seem radically different at first glance, as they do not serve the same functions (

Thompson 2011;

Youngs 2013;

Kaasa 2019), in reality, fact and fiction are closely interrelated and form a dialectical unity.

Actually, travel writing is not merely facts, data, and records of what the authors see. It is not only intellectual discussions on history, culture, science, anthropology, geography, etymology, architecture, and politics. It is simultaneously images, subjective impressions, personal observations and descriptions, individual interpretations, and embellishments. On the one hand, travel writing conveys intellectual information. On the other, it adopts expressive, emotive, and evaluative overtones to influence its audience. Which aspect prevails and to what extent—fact or fiction, science or art, the objective or the subjective—depends on the author and his/her personality, professional background, and writing style. Travel writers never doubt the twinned, intersected power of fact and fiction: they simply use both. Just prevalence is given to one to a greater extent than to the other. Therefore, travel “in the Western literary imagination, from antiquity onwards, provides an important backdrop for the overlaps between fictional and documentary modes of travel writing” (

Kaasa 2019, p. 474), with its generic boundaries covering both travel fact and travel fiction.

In addition to outlining the basics of travel writing, it is important to consider how the genre often blurs the line between fact and fiction. Travel narratives frequently rely on conventionalized structures and descriptive tropes that shape readers’ expectations and perceptions. These conventions—ranging from the use of evocative, often romanticized language to standardized narratives—influence how landscapes, architectural constructions, and cultural encounters are portrayed. The legacy of Romanticism, in particular, has had a lasting impact on the way travel writers depict the sublime or the picturesque, often prioritizing emotional resonance and aesthetic appeal over strict factual accuracy. This interplay between reality and representation highlights the inherently constructed nature of travel writing.

Western travelers of the past

5, such as the 19th-century traveler Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch, made significant efforts to understand Armenian culture and architecture by journeying to certain destinations in the Armenian Highlands. Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch’s Travel to Armenia: 1893–1894 played a crucial role in advancing the study of Armenian architectural heritage and contributed to the preservation of many historical monuments. The following discussion will explore the significance and impact of his work.

3. Armenia and Armenian Architectural History Through the Eyes of Henry Lynch

Lynch, Henry Finnis Blosse (1862–1913) (see

Figure 1), a member of British Parliament (in office in 1906–1910), traveler and businessman, was the son of the Irish businessman and explorer Thomas Kerr Lynch and his wife Harriet Taylor, whose father Colonel Robert Taylor, the British consul and resident at Baghdad, had married Rosa Moscow, the daughter of the Armenian merchant Hovhannes Moscow from Shiraz. In 1841, Thomas Lynch (Henry Lynch’s father), together with his two brothers, founded a commercial firm in Baghdad that exported goods from Britain to Mesopotamia. This family was described as “wealthy, cultured, well connected and ambitious” (

Young 2008, pp. 499–509).

6 Henry was born in 1862 in London and educated at Eton and Trinity Colleges and at the University of Heidelberg, where he studied classics. Lynch was elected as a member of Parliament for Ripon at the 1906 general elections but lost the seat at the 1910 general elections. He died unmarried in Calais, France, in 1913. Half of his estate was willed to Trinity College, a number of Middle Eastern artefacts to the British Museum, and his photographs to the British Library and to the Conway Library at the Courtauld Institute of Art

7 (

Lynch n.d.;

Neild 2012).

Lynch’s classical education (Eton, Trinity College, and Heidelberg), legal training, and commercial ventures in the Middle East uniquely positioned him to document the Armenian landscape (located in the Ottoman and Russian Empires) with both ethnographic detachment and aesthetic engagement. His background helps explain the hybrid tone of his travelogue, blending empirical observation with emotive, often poetic narrative.

Lynch’s first journey to the Armenian Highlands

8, specifically to the regions within the Russian Empire, in 1893 lasted eight months. He went back again for four months in 1898 for further research. He published the product of his trips and research on historic Armenia (located in both the Russian and Ottoman Empires) in 1901. The book contained two volumes (982 pages with 196 photographs and drawings, 16 maps, and a bibliography of 25 pages). The first was entitled

Armenia: Travels and Studies. Volume I: Russian Provinces, and the second was

Armenia: Travels and Studies. Volume II: The Turkish Provinces. The book and the illustrations covered the Armenian Highlands’ geography, history, architecture, culture, and politics in detail. The illustrations depict Armenian landscapes, portraits of people, and architectural monuments, including churches and monasteries (the Geghard and Marmashen monasteries). A positive review states that the books presented a “magnificently printed and illustrated mixture of travel notes and impressions, historical and archaeological research, political ratiocination, and geographical information” (Reviewed Work: Armenia: Travels and Studies by

Hogarth 1902, p. 153). In the present investigation, we will discuss only the first volume of Lynch’s book, as it is not possible to cover both books within the frames of one article, being hopeful that there will be another chance to display the style and architectural value of the work of the famous British traveler.

In the preface of the book,

Lynch (

1901a, p. V) answers the question of what drew him to Armenia withevocative, metaphor-rich language, describing the landscape as “the fabled seat of Paradise” and the mountains as “a wide half-circle along the margin of the Mesopotamian plain.” The inducement was the curiosity to see what lay beyond the mountains “drawn in a wide half-circle along the margin of Mesopotamian plain”, “the sources of the great rivers”, and “a lake with the dimensions of an inland sea, the mountain of the Ark”. Actually,

“The country and the people which form the theme of the ensuing pages are deserving, the one of enthusiasm and the other of the highest interest. It is very strange that such a fine country should have lain in shadow for so many centuries, and that even the standard works of Greek and Roman writers should display so little knowledge of its features and character. Much has been done to dispel the darkness during the progress of the expired century; and I have been at some pains to collect and co-ordinate the work of my predecessors”.

Lynch begins his journey in Constantinople (Ottoman Empire), pausing to admire the Bosphorus—”always bright and gay and beautiful”—which he imagines as a symbolic threshold: “the promised gate of paradise beyond the world of shades” (

Lynch 1901a, p. 2). This literary framing marks the aesthetic threshold into what Lynch, writing from a Eurocentric position, imagined as the exotic East. In Orientalist literature, “paradise” often functions as a metaphor for an idealized and exoticized East—a place full of beauty, mystery, and spiritual depth. This image flattens the East into a kind of dreamland that exists for Western exploration and also domination. In Lynch’s time, Western travel writers frequently portrayed the Middle East and Asia in this way, echoing Biblical ideas of the East as Edenic. This “paradise”is seen as beautiful, but in need of Western discovery or improvement. The image of “paradise” is a rhetorical device that romanticizes the land and legitimizes Western intervention, whether intellectual or political. The close reading of such a key phrase as”The country and the people which form the theme of the ensuing pages are deserving, the one of enthusiasm and the other of the highest interest” demonstrates the duality in Orientalist narratives:the land is framed almost like a lost paradisedeservingemotional and material investment. The other key phrase (“It is very strange that such a fine country should have lain in shadow for so many centuries”) evokes both a sense of admiration and neglect—this “fine country” (again invoking a paradisiacal quality) has been hidden or forgotten, like Eden after the Fall. The metaphorical utterance “Much has been done to dispel the darkness during the progress of the expired century”carries strong Orientalist undertones: the West is bringing light (progress) to the darkness (to the ignorant). The land is imagined as both “naturally beautiful” and “historically obscured”, a paradise waiting to be reclaimed by the West. Thus, Lynch’s use of the paradise trope positions him both as a traveller and a custodian of knowledge about a land that the West is supposed to rescue. This is Orientalism in action: a romanticization that masks power dynamics. The narrative at large foregrounds the travelogue’s stylistic duality: geographical reporting infused with poetic metaphor.

Lynch’s description of Trebizond has a dual effect: it romanticizes the landscape in line with Orientalist aesthetics and positions the narrator as both a witness and an artist. This blend of descriptive language with documentary precisionreflects conventions typical of the travelogue. The aesthetic mode (the fictional) makes an emotional effect, while the factual elements provide credibility. Together, they produce a stylized and persuasive image of the East that is ideologically loaded. Trebizond receives “the first flush of morning”. Its terraces are circling “seawards down the lower slopes of Mount Mithros to the point of the little cape”, and “rows of tall cypresses still hold the shadows of night”. But, “the white faces of the houses soon dispel the darkness, and their glass windows reflect in a glow of dazzling splendor the lurid brilliance of the rising sun” (ibid., p. 10). This writing blurs the boundaries between factual documentation (place names, geography, historical references) and fictional techniques (imagery, atmosphere, metaphor), lending authorityto the narrative through facts and names, while simultaneously attracting the reader with literary beauty. By combining the poetic with the empirical, Lynch positions himself not just as a traveler or observer but also as an artist shaping the East into a narrative that pleases and instructs the Western reader. This has the effect of elevating the travelogue to literature, while still preserving its claim to truth, reinforcing the authority of the narrator and masking ideological assumptions beneath the beauty of the prose. The effect is also genre-defining as the poetic descriptions signal an aesthetic atmosphere typical of fiction, but the numerous geographical names and historical explanations disclose the documentary aspect of the genre of travel writing very quickly. Such intersections of generic boundaries of fact and fiction, travel, and art characterize Lynch’s writing style throughout all the chapters of the book.

It should again be added that Lynch’s travelogue blends empirical observation with an emotive narrative style—a form of expression that seeks not only to inform but to stir emotional responses in the reader. His metaphoric language, particularly in describing landscapes such as the Bosphorus or Mount Ararat, positions the Armenian setting as spiritually elevated and culturally significant. This emotional charge functions rhetorically, encouraging readers to see Armenian heritage not just as historical data but as a living cultural legacy worthy of preservation.

After a scrupulous verbal and photographic description of Trebizond, with its Greek and Roman heritage and its mosques, churches, and other monuments, Lynch declares he intends to enter Eastern Armenia (under Russian rule) and “become acquainted with the Russian provinces of Armenia before investigating the condition of those under Ottoman rule not “by the well-beaten Avenue of Trevizond and Erzerum” but through Russian territory, Georgia in particular (ibid., p. 38).

The first Armenian district and city (under Russian rule) the author enters is Alexandropol (now Gyumri) “on the banks of Arpa, by the waters which swell the flood of the Araxes and sweep the base of Ararat” (ibid., p. 119). The Armenian Gregorian churches

9 here are “pretentious and commonplace both in design and in ornamentation”, “with their lace-work chisellings which adorn the exteriors of their mediæval counterparts” (ibid., p. 129). The author refers to the “Armenian Gregorian churches” contrasting them with the “lace-work chisellings” of medieval structures (ibid., p. 129). The churches in question include those built in the 19th century during Russian imperial administration, such as the Church of the Holy Saviour (Amenaprkich) and St. Astvatsatsin Church in Alexandropol. These were relatively new constructions in Lynch’s time and often reflected Russian-influenced ecclesiastical architecture, which may explain his critique of their design as lacking the distinctive medieval Armenian qualities he admired elsewhere (e.g., at Ani or Marmashen).

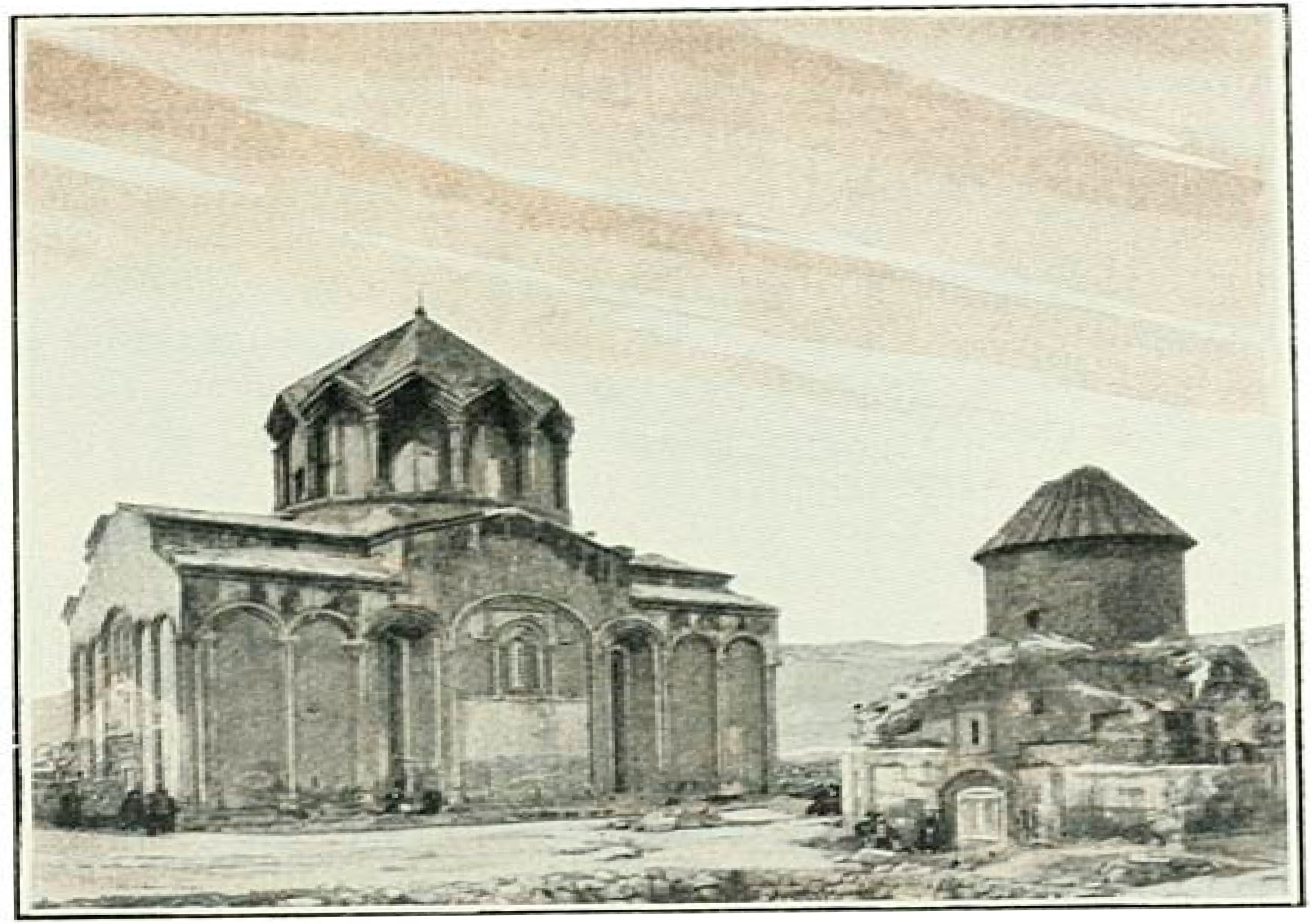

More than merely documenting the architectural features of the Church of Marmashen (

Figure 2), Lynch’s photograph serves to evoke a sense of awe and reverence for Armenia’s medieval past. Its careful composition, emphasizing the monument’s grandeur against a stark landscape, visually reinforces Lynch’s narrative portrayal of Armenian architecture as spiritually significant and culturally distinct. The image thus supports his broader argument: that these structures are not just relics, but vital symbols of Armenian identity, worthy of preservation.

Then the traveler heads for Erivan (Yerevan), a town of gardens with a network of irrigation channels. “Erivan is situated on the northern skirts of the valley of the Middle Araxes—a valley distinguished by its important geographical situation, by the great works of natural architecture which are aligned upon it, and by the high place which it holds both in legend and in history as the scene of momentous catastrophes in the fortunes of the human race” (ibid., p. 147). Unfortunately, since “Erivan does not possess any monuments of first-rate merit or of great antiquity” (ibid., p. 210), aside from its magnificent landscape, he documented four photographs of Persian buildings and mosques

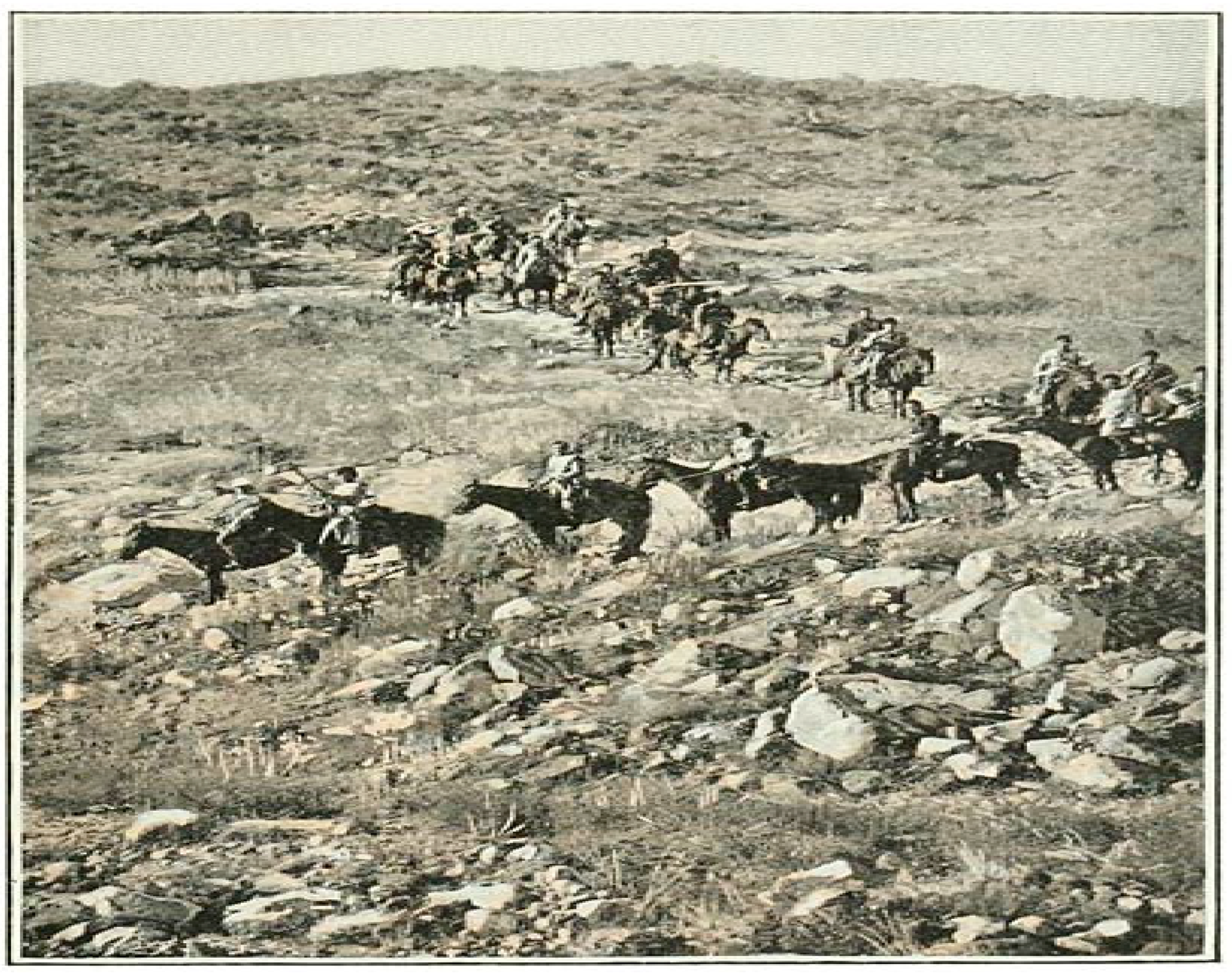

10—but not a single one of the Armenian churches that then stood in the city and have since disappeared. In contrast, the ascent of Mount Ararat is described with both informative detail and imaginative flair and is thoroughly documented in photographs. The summit is triumphantly reached: “And the ancient mountain summons the spirits about him, and veils a futile frown, as the rising sun illumines the valleys of Asia and the life of man lies bare” (ibid., p. 179). The photo (

Figure 3) shows much more than just a mountain climb. When placed next to Lynch’s vivid descriptionwhere Mount Ararat “summons the spirits” and the rising sun “illumines the valleys of Asia”, the image becomes almost mythical. The mountain feels alive, ancient, even sacred. Lynch’s words turn the landscape into something emotionally powerful, and the photograph supports that by capturing the scale and quiet drama of the moment. Together, the image and the text draw the reader into a sense of awe not just for the mountain, but for what it symbolizes: Armenian endurance, history, and spiritual identity. Lynch’s poetic invocation of Ararat is deeply symbolic, stirring reverence and solemnity. The mountain becomes not just a geographic feature but a silent guardian of Armenian history. Thus, H. Lynch has constructed a fictional atmosphere around Ararat as a real place. He evokes feelings due to the verbal and visual images created for the reader.

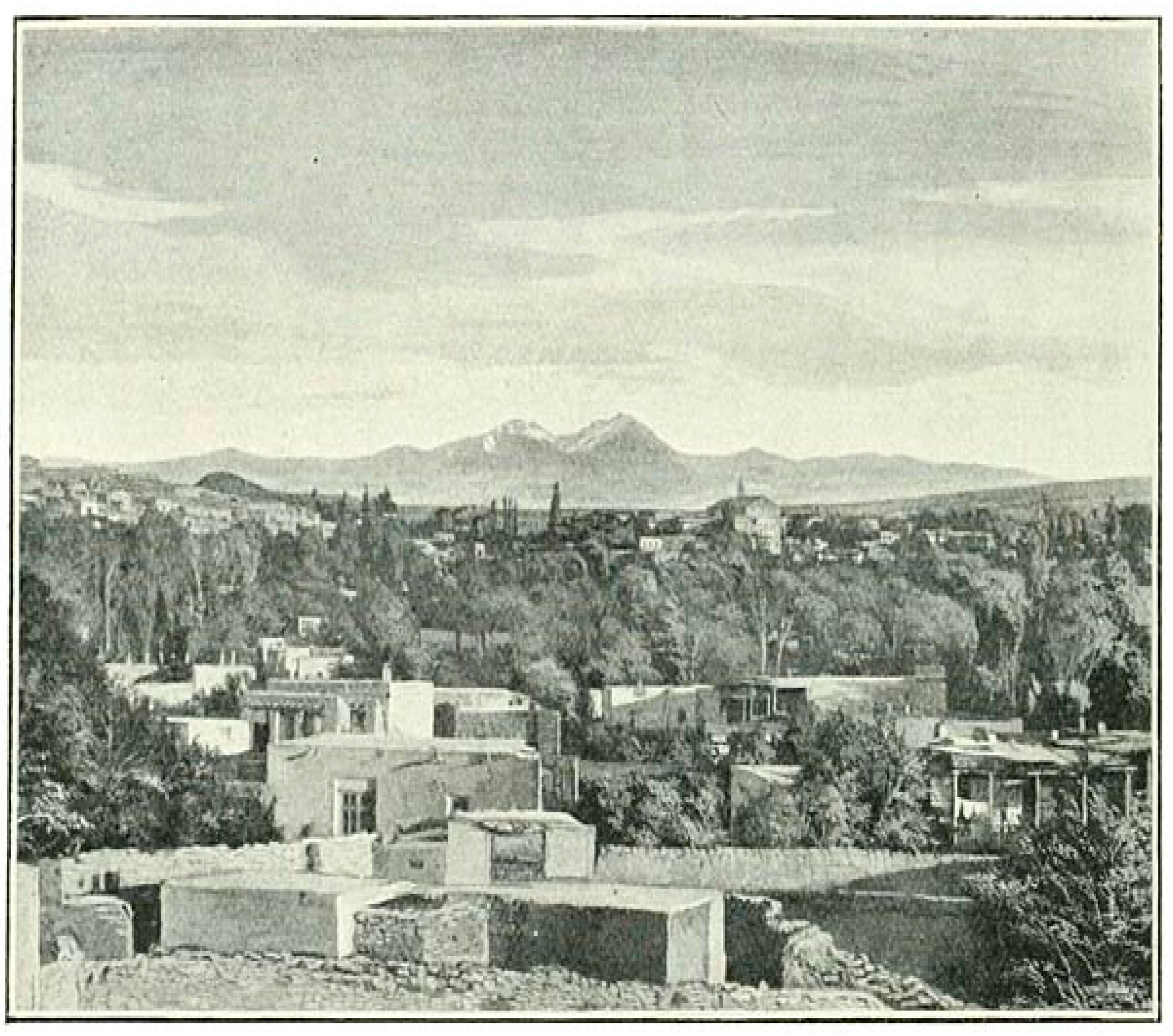

The image below (

Figure 4) is more peaceful. It shows a mountain in the distance, viewed from a rooftop in the city. It is not dramatic like Ararat, but it is still meaningful. It suggests that, in Armenia, nature and daily life are closely connected, that even from someone’s home, the landscape is never far away. Lynch describes Yerevan as a “town of gardens,” and this photo supports that quiet beauty. There’s a calmness here, a kind of balance between the personal and the monumental. While Ararat stirs big emotions and grandeur, this photo creates a feeling of belonging, a feeling of being rooted in a place where the sacred and the ordinary live side by side. Both photographs of the mountains, along with Lynch’s expressive language, help build an emotional atmosphere. They do not just inform; they move the reader. Ararat inspires wonder and reverence. Alagyaz, seen from Yerevan, offers a sense of peaceful connection to the land. By combining words and images in this way, Lynch turns his travelogue into more than a record of his trip. It becomes a kind of artistic tribute to Armenia’s landscape, history, and cultural meaning.

Descending from the mount, the author focuses his attention on the celebrated monastery located near the modern Armenian–Turkish border, approximately 30 km south of Yerevan, in the Ararat Plain. It is historically significant as the legendary site of Saint Gregory the Illuminator’s 13-year imprisonment before converting King Tiridates III to Christianity in 301 A.D.—marking the establishment of Armenia as the first officially Christian state. Lynch’s visit to Khor Virap reflects his awareness of its symbolic importance to Armenian religious identity.

From there, Lynch traveled across the mountains to Garni, the heathen temple located 28 km east of Yerevan, “above the gorge with basalt columns” and on the platform where once stood the temple of King Tiridates—“a beautiful Greek shrine given to these solitudes.”“Hard by this platform above the river are found the relics of the city of Garni; and, near the sources of the stream, at a distance of some five miles from Garni, the caves and monastery of Surb Geghard (4th–13th centuries), reputed to have been founded by St. Gregory, respond to the spirit of a landscape which for grandeur and severity is unsurpassed among these wilds.” (ibid., p. 201). The neglected state of the Geghard Monastery and many other monuments later led Lynch to express his regret that such sites were left abandoned in the harsh weather of winter. Moreover, he raised concerns about their preservation and conservation.

“For all these reasons a special duty devolves upon the traveler to address a pressing appeal both to the Armenians and to the Russian Government for the preservation of these monuments. I have already mentioned the abstraction of two important bas-reliefs, and the petty thefts which are taking place with increasing frequency. Of the buildings observed by my predecessors within comparatively recent years, the octagonal minaret has already succumbed. A like fate will presently overtake the chapel of the Redeemer, unless measures be promptly taken to maintain that edifice. The monastery of Horomosis falling into ruin. Rich Armenians spend vast sums upon the embellishment of Edgmiatsin; can none be found to conserve for the instruction of posterity the noblest examples of the genius of their race? The co-operation of the Russian Government should be secured in this laudable enterprise; nor need we despair that it will be forthcoming in such a cause. Much as that Government is inclined to discourage Armenian patriotism, it rarely omits to perform a service in the interests of culture when the appeal is general and the interests are clear.

(ibid., p. 392)

Lynch’s photographs of neglected monuments, paired with his expressive prose lamenting their abandonment, create an emotional atmosphere of solemnity and reverence. This pairing of visual and verbal imagery is designed to elicit affective reactions in the viewer, particularly a mix of admiration for the monument’s spiritual gravity and concern for its vulnerable state.

Lynch’s nuanced critique of Russian governmental inaction is a critical aspect of his travelogue. His commentary on architectural decay, especially at sites such as Geghard and Horomos, is more than an aesthetic lament; it constitutes a pointed political appeal. His statement referring to the cooperation of the Russian Government is deliberately double-edged. While diplomatically phrased, it subtly implies a lack of prior commitment or initiative from the Russian authorities. What makes this significant is that Lynch, as a British subject with imperialist ties, was not merely documenting ruin; he was making a public call for institutional responsibility. His appeal reflects his broader ideological position: skeptical of Russian rule over Armenian territories, yet hopeful for transnational cooperation in the name of cultural heritage. His tone also reveals his ideological leanings toward Armenian cultural self-determination. By including this criticism, Lynch positions himself not just as an observer but as a moral advocate for the Armenian cultural legacy. His rhetorical strategy—blending admiration, regret, and appeal—exemplifies how travel writing could function as a form of early heritage activism.

We recognize that Lynch’s admiration and concern for Armenian monuments are evident through his prose and photographs. He consistently viewed these monuments as embodiments of Armenian cultural identity and as evidence of a sophisticated architectural tradition distinct from neighboring empires. His view of Armenian culture extended beyond its architectural legacy; he regarded it as a deeply historical, spiritual, and intellectual tradition. He described Armenia as “deserving the highest interest,” lamenting that such a “fine country should have lain in shadow for so many centuries” (

Lynch 1901a, p. VIII). His prose reveals that he admired the Armenians’ resilience and their religious devotion. He often framed Armenian culture as a bridge between the East and the West, celebrating its unique synthesis of Christian, Byzantine, and Oriental elements. At the same time, his concern over the neglect of heritage sites was motivated by a desire to preserve Armenian cultural distinctiveness amid Russian and Ottoman dominance.

Lynch, after a lengthy discussion of the historical, educational, and religious value of Edgmiatsin (Echmiadzin) and some religious rites, refers to the architectural structure of the Cathedral: interior of the portal of the Cathedral, the vaulted ceiling, the well-lit chambers, the throne and the canopy of the Catholicos (the Archbishop), the park of the Cathedral, the monks’ residences, adjacent premises, the treasury and room of relics, etc. Then he focuses on the three Chapels of the Martyrs situated within short walks from the monastery: St. Gaiane, St. Ripsime, and St. Shoghakath. Lynch’s focus on chapels and religious structures in general reflects his understanding of Armenian identity as fundamentally rooted in Christian heritage. Armenia’s distinction as the first officially Christian state (301 AD) deeply influenced Lynch’s interpretive lens; he saw ecclesiastical architecture not just as art or engineering, but as expressions of national memory and spiritual continuity. The chapels of St. Gaiane, St. Ripsime, and St. Shoghakat, associated with martyrdom and the establishment of Armenian Christianity, embodied what Lynch perceived as the moral and cultural essence of the Armenian people. His detailed attention to these sites thus aligns with his broader purpose: to present Armenia’s religious architecture as both a sacred heritage and a testament to national endurance under foreign dominion. The ancient cathedral (a 10th-century masterpiece of the Bagratid Armenian architecture) of the ruined city of Ani was the next destination of Lynch.

He resorts to the meticulous description of both the monuments and the history of the medieval Kingdom of Ani. His descriptions are documented with twenty-eight magnificent photographs of the city and its architectural monuments. However, specialists argue that the descriptions are very lengthy and not particularly original. In addition, “there are few implications regarding the dating of the monuments and the chronology of architectural styles”(

Marouti 2018, p. 80). However, it is worth mentioning here that, after studying the cathedral of Ani, the church of St. Gregory, and the two polygonal chapels, Lynch came to a very important conclusion:

“These monuments are examples of the Armenian style at its very best before it was brought under the direct influence of Mussulman art and adopted with slight variations Mussulman models. […] The merits of the style are the diversity of its resources, the elegance of the ornament in low relief, the perfect execution of every part. It combines many of the characteristics of Byzantine art and of the style which we term Gothic, and which at that date was still unborn. The conical roofs of the domes are a distinctive feature, as also are the purely Oriental niches. Texier is of opinion that the former of these features was carried into Central Europe by the colonies of emigrants from the city on the Arpa Chai”.

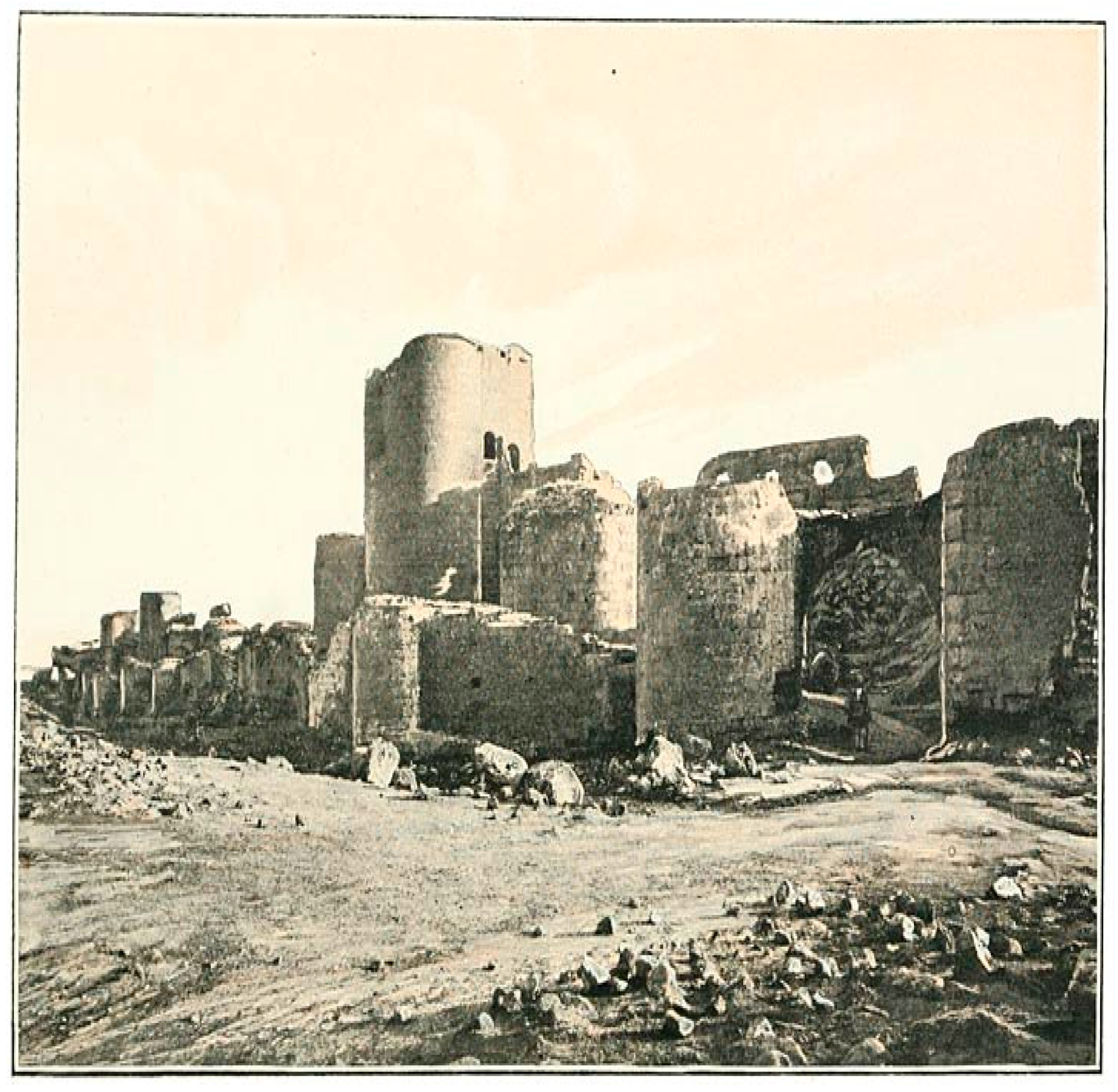

Figure 5, showing the walls and gateway of Ani, offers a striking visual support for Lynch’s claim that medieval Armenian architecture bears notable similarities to European Gothic design. The pointed arches, the strong vertical lines, and the meticulous stonework all echo hallmarks of the Gothic style, especially its balance of structural elegance and decorative richness. As Lynch himself observes, Armenian architecture “combines many of the characteristics of Byzantine art and of the style which we term Gothic, and which at that date was still unborn” (

Lynch 1901a, p. 391). By drawing a connection to the Gothic (a style long celebrated in European art history),Lynch elevates Armenian architecture, placing it within the realm of Western high culture. This comparison isnot just aesthetic; itis strategic. Lynch aims to reframe Armenia not only as an original culture, but also as a center of architectural innovation that may have even influenced European developments. The photograph reinforces this argument, inviting viewers to make their own visual comparisons between the Armenian and Gothic traditions.

Lynch’s descriptionsrefernot to invented narratives, but to aestheticized language, symbolic framing, and emotional coloration that go beyond the objective cataloging of sites. Lynch did not invent or fictionalize historical facts, but he did employ literary techniques typically associated with fiction (such as romanticized imagery and creative style) to shape readers’ perceptions. Lynch’s use of lyrical, evocative language—especially metaphors of paradise, grandeur, and decay—functions to shape the reader’s perception of Armenian architecture as spiritually and historically significant. His rhetoric does not merely embellish; it reframes ruins as cultural testimony and architecture as narrative.

Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch’s Armenia: Travels and Studies remains an essential source for scholars of Armenian architecture and cultural heritage for several reasons.

- (1)

Historical documentation in the absence of originals:Lynch’s photographic and descriptive documentation has preserved records of architectural monuments that have since been damaged, altered, or destroyed. His visual and textual records serve as critical references for conservationists and historians seeking to reconstruct or understand lost heritage;

- (2)

Academic and archival relevance:His work continues to be referenced in the modern academic literature and doctoral theses, and his photographs are part of ongoing digitization efforts at institutions such as the Courtauld Institute of Art and the British Library;

- (3)

Raising awareness through travel writing: Travel writing serves not only to inform but also to inspire and activate awareness—this includes awareness about cultural heritage at risk. Lynch’s emotive narrative and evocative visuals, particularly his photographs of sacred sites (Khor Virap, Geghard, Ani), are evocative of spiritual reverence, cultural loss, and historical grandeur. These images do not merely document structures; they frame them as fragile remnants of a profound civilizational legacy, stirring both admiration and a sense of urgency regarding preservation. Together, the emotive narrative and the evocative visualsengage readers both intellectually and emotionally, aligning with the dual function of travel writing: to educate and to advocate. His writing thus encourages not only scholarly engagement but also public appreciation—key elements in the broader discourse of heritage protection;

- (4)

Preservation through cultural memory:Preservation is not limited to physical restoration; it also includes maintaining cultural memory. Lynch’s work, as argued in the conclusion, helps keep the legacy of Armenian architecture alive in global consciousness. His travelogue is part of how this legacy entered European scholarly imagination and remains accessible to modern readers and researchers through reprints and digitized editions. Thus, Lynch’s travelogue continues to serve as both an archival tool and a cultural medium that enhances scholarly knowledge and public awareness, which are foundational to any sustainable heritage preservation strategy.

While many 19th-century European travel writers approached Armenia through the lens of romantic exoticism, Henry F. B. Lynch’s work is distinguished by its combination of descriptive precision, political engagement, andscholarly ambition. His two-volume

Armenia: Travels and Studies (

Lynch 1901a,

1901b) reflects a level of empirical rigor uncommon among his peers, incorporating photos, maps, architectural plans, and historical commentary alongside narrative accounts. Lynch’s efforts to document Armenian architectural heritage were shaped not only by aesthetic interest but also by a geopolitical awareness of the region’s strategic importance and contested histories. This distinguishes his writing from more impressionistic accounts, positioning it as a contribution to emerging discourses of imperial knowledge production.

4. Conclusions

The story of how Armenian art and architecture entered the European scholarly imagination is, in part, the story of the 19th-century travelers who documented cultural monuments across imperial geographies with a mix of admiration, curiosity, and, at times, advocacy. Lynch’s extensive travels and writings provided a substantial visual and textual archiveof Armenian historical sites, particularly under Russian and Ottoman rule.

Not only does H. Lynch’s expressive and evocative language engage the reader on an emotional level, but his vivid and carefully composed visuals—particularly his photographs—also serve to heighten this emotional impact. These images, often capturing the raw beauty of ruined monasteries or the solemn grandeur of isolated landscapes, evoke a visceral response in the form of awe, melancholy, and cultural empathy, prompting the viewer to feel the spiritual depth of Armenian heritage and the urgency of its preservation. This emotional engagement is one of the primary functions of travel writing: to immerse the audience not just intellectually but affectively, evoking admiration, wonder, reverence, and a quiet grief for what is vanishing.

In addition to this emotional resonance, Lynch’s work also fulfills the informative function that is central to travel literature. Through his detailed descriptions and keen observations, he conveys a wealth of geographical, historical, and architectural knowledge about the places he visits. Whether describing the layout of a city, the structure of a remote village, or the cultural significance of a monument, Lynch provides readers with a rich tapestry of contextual information. His writing, therefore, does more than merely narrate a personal journey—it educates and enlightens, offering readers insight into the physical and cultural landscapes he explores.

His work is undeniably valuable for the preservation of memory and material culture, especially in regions where many structures have since been damaged or lost. However, this documentation must be approached critically. Lynch was not a neutral observer but a participant in the broader project of European imperial knowledge production. His accounts were shaped by the geopolitical interests of the British Empire and reflect orientalist and paternalistic attitudes common to his time. Travel writing, as a genre, often romanticized the East while simultaneously asserting a Western authority to interpret, categorize, and evaluate other cultures. While Lynch did call for preservation, this advocacy coexisted with the colonial logic that positioned Europe as the custodian of world heritage—frequently ignoring or overshadowing local and indigenous efforts.

Revisiting Lynch’s work today offers insight not only into the historical architecture of Armenia but also into the power relations and ideologies embedded in the act of documentation itself. His travelogue should be appreciated for its contributions while alsobe interrogated for its silences and selective emphasis. These are biases that reflect the imperial and orientalist ideologies of his time. In this way, Lynch’s writings become a lens through which to examine not just endangered monuments, but also the complex entanglement of preservation, politics, and narrative authority in both historical and contemporary contexts.

Beyond his contributions as an observer, Lynch’s vision of a semi-autonomous Armenia and his cautious stance toward Russian involvement show a nuanced ideological position—one shaped by his background and the broader currents of British imperial thought. His legacy is thus complex but invaluable: a bridge between cultures, a record of endangered heritage, and a reminder of the role individuals can play in the preservation of history.