1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid growth of the film industry has highlighted the increasing importance of source material in content creation. IP adaptation has become a common mode of film production. Intellectual Property (IP) represents inventions, writings, music, designs, and other works that may arise during innovation and product planning activities (

Kahn and Mohan 2020). In the field of film and television, IP has generally come to be regarded as a synonym for “original works” or “content resources”, including artistic works, animated characters, films, and video games (

Y. Chen 2024). Well-known IP examples include Disney’s Mickey Mouse and the

Harry Potter series and its related films. “IP adaptation” is commonly defined as the process by which film and television production and distribution companies, through either free use or the purchase of copyrights to existing artistic works or content resources, adapt them and release them as TV dramas, films, or similar audiovisual products (

Y. Chen 2024).

Generally, high-quality IPs, having undergone market evaluation, possess a strong reputation before being adapted into films. With such source material, filmmakers can focus on expanding existing narratives, reducing the need to create entirely new characters, scenes, or storylines. Additionally, the audience’s prior familiarity with the source material attracts loyal fans of the original works, ensuring higher box office returns and generating significant social and market impact.

As of 10 July 2025, data from Maoyan’s global historical box office ranking

1 reveal that nine out of the top ten highest-grossing films are adaptations, with

Avatar (2009) being the only original screenplay. Detailed figures are shown in

Table 1. These nine films are adapted from various sources, including real events, literary works, comic works, animated TV series, and film works. Some of these films have undergone multiple adaptations. These successes highlight the significant commercial potential of IP adaptations in cinema.

However, the quality of IP adaptations varies significantly. While some films stand out for their excellence, others are criticized for excessive modifications or poor production quality. For instance, the adaptation of the classic IP

Snow White (2025), based on the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tale, has been controversial in both character portrayal and plot adaptation, leading to a dual failure in box office performance and critical reception and a notably low IMDb rating of 2.0

2. This highlights that audiences are discerning and do not accept adaptations indiscriminately. In fact, the transformation from written text to audiovisual language presents significant challenges. Adapted films must meet audience expectations while also surprising and delighting them. Identifying and applying successful adaptation strategies could have a significant impact on the broader film market. Therefore, exploring the strategies of film adaptation is crucial for advancing both the theoretical framework and practical guidance of the field.

As the only Chinese film in the global top ten and the latest to break into the top five worldwide,

Ne Zha 2 (2025) is an excellent case of IP adaptation. It is noteworthy that

Ne Zha 2 (2025) not only grossed CNY 15.446 billion in China by 10 July 2025, far surpassing China’s previous highest box office record of CNY 5.775 billion

3, but also achieved an IMDb rating of 8.1

4. The film topped both the Chinese box office (see note 3) and the global animated film category

5, ranking fifth worldwide (see note 5). It represents a significant leap for Chinese cinema, and its success can provide valuable insights for the adaptation of other films, warranting thorough examination.

At the same time,

Ne Zha 2 (2025), as a classic mythological IP passed down for thousands of years, is revitalized through film adaptation, effectively inheriting and promoting Chinese traditional culture.

Ne Zha 2 (

Ne Zha: Mo Tong Nao Hai, 哪吒之魔童闹海, 2025)

6 is primarily adapted from the classic intellectual property (IP) of Nezha (哪吒), a widely known figure in Chinese folklore whose origins date back to the Tang Dynasty (618–907), with a history spanning over a thousand years (

Whyke and Mugica 2021). The adaptation sources for this film include the literary work

The Investiture of the Gods (封神演义, 1567–1619)

7, the earlier film

Nezha Nao Hai (哪吒闹海, 1979)

8, the animated series

The Legend of Nezha (哪吒传奇, 2003)

9, and the previous film in the franchise,

Ne Zha (

Ne Zha: Mo Tong Jiang Shi, 哪吒之魔童降世, 2019)

10. The success of

Ne Zha 2 (2025) not only promotes Chinese culture but also provides a reference for the cultural preservation of other countries and regions. Therefore,

Ne Zha 2 (2025) is of great significance from artistic, commercial, and cultural perspectives.

Aiming to contribute to the further development of film adaptations, the main research questions of this study are as follows: what adaptation strategies do excellent IP adaptations generally follow? Taking Ne Zha 2 (2025) as a case, how is this film adapted? What adaptation strategies does it embody? And what implications do these adaptation strategies have for the development of adapted films?

Specifically, this study will use a case study approach to analyze

Ne Zha 2 (2025)’s adaptation strategies. The case study approach is a qualitative research approach that focuses on a single or a few cases to conduct in-depth exploration of complex phenomena, thereby revealing their occurrence mechanisms and inherent laws (

Yin 2009). In this study, the analysis follows three main steps: (1) collecting and reviewing primary sources, including film synopses, related films, audience feedback, and box office data; (2) conducting a comparative analysis with previous Nezha adaptations; and (3) analyzing the film from four key perspectives—character, plot, theme, and esthetics, demonstrating how their strategic application contributed to its success both at the box office and in critical reception.

2. Film Adaptation Strategies: Intertextuality and Innovation

Before specifically analyzing the adaptation strategies of Ne Zha 2 (2025), this study first summarizes previous scholars’ perspectives on film and adaptation, providing theoretical support for the in-depth exploration of Ne Zha 2 (2025)’s adaptation strategies.

Typically, product quality is difficult to observe before purchase but is fully revealed after the purchase; such products are referred to as experiential products (

Wright and Lynch 1995). As an experiential product, the purpose of filmmaking is to evoke emotions, while the primary goal of the audience is to obtain a positive emotional experience (

Smith 2003;

Tan 2013). This is where the significance of film innovation lies. Emotional experiences derived from film viewing encompass not merely hedonic value but also a sense of significance and self-development (

Piçarra et al. 2021). When the audience acknowledges the adaptation and gains a positive emotional experience from it, the adaptation becomes more meaningful, and its market performance improves.

Film adaptation revolves around two fundamental questions: the extent of adaptation and the direction of adaptation. Regarding the extent, adaptation can be viewed as a process of intertextual reworking and creative reinterpretation (

Hutcheon 2006, p. 22). Filmmakers must find a balance between intertextuality and innovation. Many intellectual properties (IPs) originate from texts or are derived from existing films that rework the source material. Therefore, the adaptation process inherently involves intertextuality—the relationship and influence between a text and other texts—which may extend to media such as film, theater, and visual arts (

Allen 2021;

Raissi and Ghaffari 2023). In the case of literary works, both literature and film share three core narrative elements: characters, plot, and theme. Filmmakers can innovate upon the original work, and the transformation of text into visual media enables esthetic reimagination, offering significant creative flexibility.

Anchoring bias is one of the most powerful effects in cognitive psychology. It suggests that when people are presented with information, they are often influenced by prior knowledge and experiences, forming a psychological anchor. In this effect, people’s judgments tend to be biased toward values they have previously encountered (

Spicer et al. 2022). Consequently, filmmakers can employ techniques such as pastiche, parody, and homage to intertextually reference previous works or videos, skillfully using intertextuality to evoke emotional memories of the original works and meet audience expectations (

X. Chen 2020).

However, many literary and film works are quite old, and strictly adhering to the original during adaptation not only lacks novelty but also fails to evoke emotional resonance with the audience. Moreover, humans have an inherent curiosity to seek novelty, and audiences derive pleasure from experiencing novelty, which fulfills their emotional needs during film viewing (

Chen et al. 2020). Yet, novelty achieved through mere eccentricity does not equate to creativity, nor does it create meaningful value (

Burroughs and Glen Mick 2004). Therefore, the extent of adaptation is not necessarily better when greater.

Studies show that novelty itself is not correlated with market performance, but when it provides meaningful differentiation for consumers, it becomes related to market success (

van Trijp and van Kleef 2008). Therefore, film adaptations must balance intertextuality and innovation: preserving the core themes, familiar characters, or plot elements from the original work to activate intertextual memory while incorporating modern, defamiliarizing innovations that align with current esthetics and values to offer a surprising viewing experience (

Zhang et al. 2021). This process of recreation ensures that adaptations can survive and endure over time (

Cahir 2006, p. 14).

From the perspective of film narratology, film adaptation can be analyzed via several key dimensions, including characters, plot, themes, and esthetics, forming a comprehensive analytical framework (

Zhu 2024). Character adaptation reshapes character images and personalities; plot adaptation drives narrative progression and controls pacing; theme adaptation imbues the work with contemporary relevance and ideological depth; and esthetic adaptation creates a distinctive audiovisual style and artistic atmosphere. Additionally, enriching the overall elements of a film enhances its completeness and visual appeal (

Wang 2020).

The adaptation strategies summarized above provide a theoretical foundation and reference framework for analyzing specific works and can also guide film adaptations. As an outstanding example of IP adaptation films, Ne Zha 2 (2025) has brilliantly applied and innovated these strategies. It skillfully strikes a balance between intertextuality and innovation, drawing deeply from the original and previous works to establish a strong intertextual link with the classics while also boldly innovating to showcase its unique adaptation charm. The following sections of this paper will delve into this work, exploring in detail how it skillfully adapts, resulting in both commercial success and critical acclaim.

3. Analysis of Ne Zha 2 (2025) Adaptation Strategies

Prior to analyzing the adaptation strategies of

Ne Zha 2 (2025), we first explore the most widely celebrated and enduring story version of the character IP Nezha in ancient times. Nezha’s story in

The Investiture of the Gods (封神演义, 1567–1619) (see note 7) laid the core spiritual foundation for subsequent adaptations of the Nezha IP. Nezha is a divine general reincarnated from the Spirit Pearl (灵珠), and the son of Li Jing, military governor of Chentang Pass (陈塘关). In his youth, he stirred up chaos in the East China Sea, furiously slaying Ao Bing, the third son of the Dragon King. To protect his family, he severed his mortal ties through self-sacrifice for the father (剔骨还父)

11. Later, his master Taiyi Zhenren (太乙真人) reforged his physical form with lotus flowers, granting him an immortal body. Wielding the Qiankun Circle (乾坤圈), Huntian Ling (混天绫), and treading the Feng Huo Lun (风火轮), he had an unruly temperament yet adhered to righteous principles. During the conflict between the Shang and Zhou dynasties, he repeatedly defeated demons and evil forces, becoming a classic symbol of defying fate to rewrite destiny and loyalty combined with righteous rebellion.

Due to the excellent box office performance of Ne Zha 2 (2025), this article would like to focus on Ne Zha 2 (2025) as the core and conduct an in-depth analysis by comparing it with previous Ne Zha films. Ne Zha 2 (2025), the sequel to Ne Zha (2019), has broken free from the sequel curse, representing a significant leap for Chinese cinema and the substantial commercial potential of IP adaptations in film. This prompts two key questions: what factors contribute to Ne Zha 2 (2025)’s unprecedented success? Additionally, how do its adaptation strategies improve upon those of its predecessor?

Ne Zha (2019) is a landmark animated film, grossing CNY 5 billion at the box office, making it China’s highest-grossing animated film and the second highest-grossing film overall. Before its release, audiences were most familiar with Nezha’s depictions in Nezha Nao Hai (1979) and The Legend of Nezha (2003). Ne Zha (2019) makes substantial adaptations to pre-existing works, creating a variety of fresh characters and narratives that have received widespread acclaim. Its sequel, Ne Zha 2 (2025), retains the character designs and world-building while advancing the plot toward the climactic Nezha Nao Hai (Nezha Conquers the Dragon King) episode. Next, this study will provide an in-depth analysis of the adaptation strategies in Ne Zha 2 (2025) through four key dimensions—character, plot, theme, and esthetics—exploring ways to balance intertextual references with innovative reinterpretation to achieve success.

3.1. Character Adaptation

In terms of character adaptation,

Ne Zha (2019) modernizes and defamiliarizes the millennia-old mythological figure of Nezha across three dimensions: visual design, personality traits, and value orientation. Traditionally depicted as a noble, heroic figure in works like

Nezha Nao Hai (1979), this version presents Nezha as a slouching, dark-circled demon child, while his mentor Taiyi Zhenren (太乙真人) is reimagined as a gluttonous, unreliable character riding a winged pig instead of the traditional crane (

Figure 1).

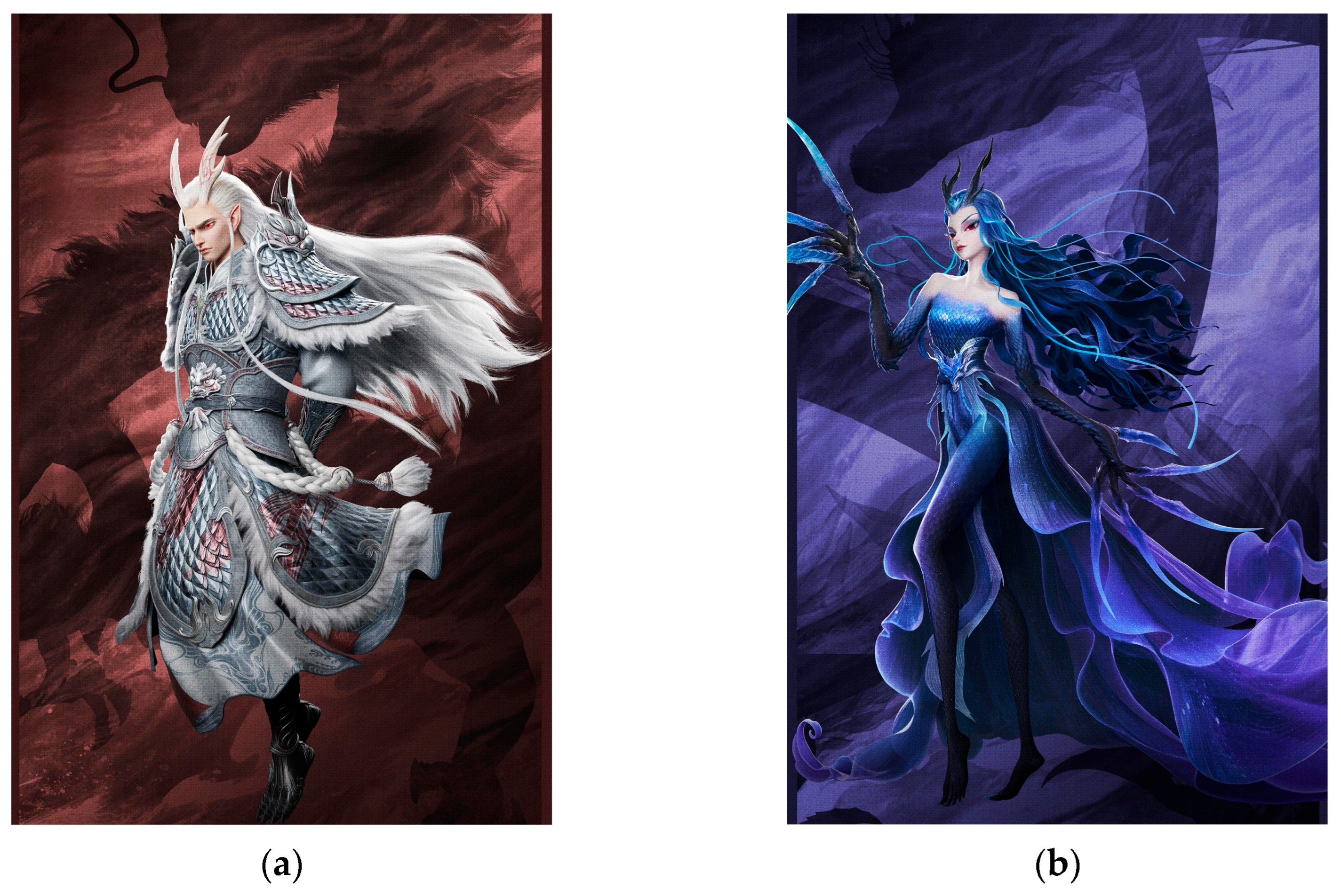

Similarly, Ao Bing (敖丙), the dragon prince traditionally portrayed as a monstrous antagonist, is reimagined as a refined, charismatic antihero (

Figure 2).

Ne Zha 2 (2025) retains these subversive characterizations while introducing new figures that combine familiar archetypes with modern esthetic sensibilities, creating three-dimensional characters through psychological depth and updated visual semiotics.

3.1.1. Presenting Familiar Character Archetypes to Evoke Intertextuality

Compared to its predecessor,

Ne Zha 2 (2025) expands the protagonist’s narrative with the introduction of Spirit Pearl Nezha (灵珠哪吒), where Ao Bing’s soul inhabits Nezha’s body, adopting his appearance and mannerisms. In contrast, the first film’s Demon Pill Nezha (魔丸哪吒) subverted expectations with his disheveled, ugly design (dark circles and slouching posture), while the Spirit Pearl version mirrors the elegant, heroic Nezha from the classic

Nezha Nao Hai (1979)—a nostalgic reference highlighted by Taiyi Zhenren’s meta-commentary “This is the authentic version!” (

Figure 3). This intertextual reference plays out through the celestial trials, where the narrative alternates between Demon Pill Nezha (conscious) and Spirit Pearl Ao Bing (unconscious), gradually acclimating audiences to the protagonists’ transformation from a singular figure to the Nezha–Ao Bing destined dyad, balancing defamiliarization with nostalgic familiarity.

3.1.2. Witnessing the Character’s Journey from Self to the World

Nezha’s developmental trajectory mirrors the nonlinear progression of adolescence, reflecting the Confucian ideal of “self-cultivation, familial harmony, state governance, and universal peace” (修身齐家治国平天下), marking a departure from the Nezha Nao Hai (1979), where he was portrayed as a heroic figure who prioritized society over family. In Ne Zha (2019), the protagonist undergoes a psycho-spiritual transformation, achieving “self-cultivation” by overcoming existential crises. The sequel, Ne Zha 2 (2025), advances this arc: his defense of family and comrades embodies “familial harmony”, while his efforts to rescue Chentang Pass citizens, reconcile with dragon clans, and fight injustice signal his steps toward “state governance and universal peace”. Despite his impulsive traits—such as rashly attacking the Dragon King after misinterpreting the clan’s motives—these character flaws enhance the narrative’s realism. Everyone is imperfect, with both strengths and weaknesses. This portrayal of Nezha makes it easier for the audience to empathize.

3.1.3. Multidimensional and Subversive Character Depictions

Before the Ne Zha series, characters in related literary and cinematic works were often portrayed as morally dichotomous, with a rather one-dimensional characterization. In Ne Zha 2 (2025), however, each character is given a multidimensional personality, where good and evil are not absolute. The film also features subversive characterizations, offering refreshing takes on well-known figures.

Wuliang Xianweng (无量仙翁): modeled after the Daoist longevity deity Nanji Xianweng (南极仙翁)

13 this character is reimagined as the representative of the Orthodox Enlightenment Sect (阐教)

14 and the acting leader of Yuxu Palace (玉虚宫). In the film, he serves as the primary antagonist. Traditionally, popular mythology portrays gods as virtuous and demons as wicked, with white and gold representing righteousness and black symbolizing evil. However, in this film, the Monster Capture Brigade, dressed in white and presenting themselves as guardians of justice, follow Wuliang Xianweng’s orders to falsely accuse demon clans, capturing them to refine them into elixirs for the sect’s gain. Paradoxically, many of the demons are depicted as kind-hearted, creating a dramatic narrative reversal.

Shen Gongbao (申公豹): in previous adaptations, Shen was generally depicted as a villain. In Ne Zha (2019), he swaps the Spirit Pearl and the Demon Pill. After his plot is uncovered, he manipulates Ao Bing into burying Chentang Pass. However, in the sequel, his character becomes more nuanced, showing love for his family, rationality, and a sense of justice. His decision to steal the Spirit Pearl stems from the discrimination he faced as a member of the demon clan, which prevented his promotion to the Twelve Golden Immortals, causing deep resentment. Later, after discovering that the Orthodox Enlightenment Sect had killed his father and brother, and moved by the compassion of Li Jing and his wife, Shen redeems himself by saving the Li family and defending Chentang Pass, ultimately transforming into a hero.

3.1.4. New Supporting Characters with High Esthetic Appeal and Lovable Traits

In Ne Zha 2 (2025), many demon clan characters are introduced as supporting roles, challenging the stereotype that “all demons are evil.” Beyond the protagonists Nezha and Ao Bing, even the minor characters have gained significant popularity online. Video edits of individual supporting roles have exceeded one million views and tens of thousands of likes, demonstrating the film’s rare ensemble appeal—a phenomenon seldom seen in standalone films.

The film attracts audiences in two ways. On one hand, new characters like Ao Bing’s father East Sea Dragon King Ao Guang (龙王敖光) and West Sea Dragon King Ao Run (西海龙王敖闰) are designed with high visual appeal, fitting the “looks-first” trend and gaining popularity online (

Figure 4).

On the other hand, these characters are portrayed as kind, cute, and optimistic, making them feel like real-life friends. In a key scene, Spirit Pearl Nezha passes a celestial trial by defeating three earth immortals (who are later revealed to be demons). He then takes them to Yuxu Palace with the Monster Capture Brigade. Below are details about these earth immortals and their families:

Groundhog Immortal (土拨鼠): the first earth immortal, an original character. With a clumsy yet endearing appearance and tattered clothes, this character avoids conflict but uses the widely recognized marmot scream sound effect when provoked, adding many humorous moments.

Shen Zhengdao (申正道): the second earth immortal and Shen Gongbao’s father. A kind-hearted educator who admires the Orthodox Enlightenment Sect and runs a “talent academy” to teach young demons cultivation.

Shen Xiaobao (申小豹): the younger brother of Shen Gongbao, he is an extremely cute little boy who practices diligently every day. His hairstyle and mannerisms closely resemble those of Nezha, and he enjoys composing playful rhymes.

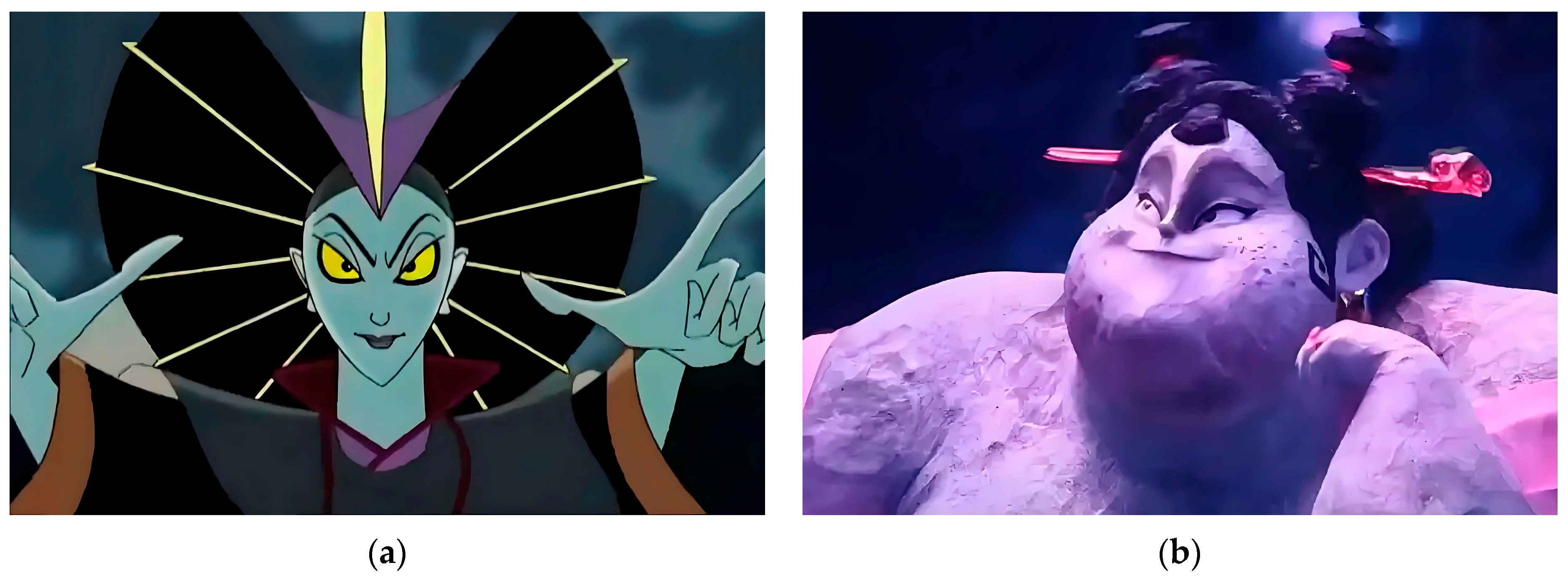

Shi Ji Niangniang (石矶娘娘): the third earth immortal, reimagined from her traditionally slim, villainous portrayal in the animated series

The Legend of Nezha (2003) into a plump, non-confrontational beauty enthusiast (

Figure 5). Rather than seeking power or fame, she often asks her bronze mirror, “Am I the fairest?” Her most endearing moment occurs after Nezha defeats her, leaving only scattered stones. She reassembles them and says, “Luckily, there’s a bit left! Where there’s life, there’s hope.” Her quirky, high-pitched voice and resilient optimism have made her a fan favorite.

Submerged Demon Clans (海底妖兽): confined in an underwater purgatory, these demons are ultimately imprisoned by Wuliang Xianweng in the Celestial Cauldron (天元鼎) for elixir refinement. In their final moments, roasted by the Samadhi Flames (三昧真火), they humorously share their octopus legs, fish fins, and crab claws, demonstrating a spirit of resilient optimism.

These endearing characters evoke deep empathy—their charming appearances and lively mannerisms, combined with their innate kindness, contrast sharply with the unjust persecution by Wuliang Xianweng and the Monster Capture Brigade, thereby intensifying audience sympathy.

3.2. Plot Adaptation

In terms of plot adaptation, Ne Zha (2019) employs a defamiliarized storytelling approach, reimagining Nezha as the incarnation of the Demon Pill (魔丸转世) instead of the traditional Spirit Pearl (灵珠转世) and transferring the Spirit Pearl identity to Ao Bing. The rivalry between Nezha and Ao Bing is also transformed into a destined partnership. The sequel, Ne Zha 2 (2025), continues this narrative while innovatively reinterpreting the iconic “Nezha Nao Hai (Nezha Conquers the Dragon King)” plot through multiple reversals and expanding the storyline with comedic elements and ethical complexity, enriching the plot to cater to family-friendly, cross-generational appeal.

3.2.1. Intertextuality and Multiple Plot Twists in Traditional Storylines

In the animated classic Nezha Nao Hai (1979), the Dragon King orders a yaksha to abduct children, but Nezha intervenes, prompting Ao Bing to defend his father’s honor. Nezha kills Ao Bing, leading the Four Dragon Kings to flood Chentang Pass (陈塘关) and force Nezha to commit suicide. After resurrecting, Nezha wreaks havoc in the Dragon Palace, giving rise to the title “Nezha Nao Hai (Nezha Conquers the Dragon King)”. Ne Zha 2 (2025) directly adapts this story, as reflected in its title. In the trailer, Dragon King Ao Guang declares, “If I strike, not even a chicken or dog will survive in Chentang Pass”, invoking memories of the original plot and positioning Ao Guang as the presumed antagonist.

However, Ao Guang, tasked with overseeing the submerged purgatory, assigns the mission to attack Chentang Pass to Shen Gongbao. Using the Rift Claw (裂空爪), Shen enlists the other three Dragon Kings and Submerged Demon Clans to launch the assault. The attack is called off when Nezha agrees to complete celestial trials within seven days to resurrect Ao Bing. Later, Shen’s brother, Shen Xiaobao, dies during the trials. The film presents a close-up of Shen Gongbao’s enraged expression, which is swiftly followed by a scene shift to Nezha’s group being informed of a crisis at Chentang Pass. Given Shen’s role as a villain in the first film, coupled with his furious expression and West Sea Dragon King Ao Run attributing the attack to Shen, the narrative misleads the audience, making them suspect that Shen is the ultimate antagonist responsible for the massacre of Chentang Pass.

However, the final revelation that Wuliang Xianweng is the true antagonist delivers yet another dramatic twist. This recontextualizes Shen Gongbao’s iconic line from the first film—“Prejudices in people’s hearts are mountains”—as audiences confront their own biases in attributing the Chentang Pass massacre to him. The intertextual reference to the first film adds an emotional depth, reinforcing the theme of preconceived notions. Through these successive twists, the film subverts traditional narrative structures, offering audiences unexpected thrills and heightening the dramatic tension.

3.2.2. Sequel’s Tight Connection to the Predecessor with New Plot Additions

Ne Zha 2 (2025) begins with the physical resurrection of Nezha and Ao Bing, seamlessly continuing the first film’s conclusion. Numerous details establish continuity between the two films: beyond Shen Gongbao’s recurring line, both installments feature emotionally charged moments, such as the “grit in the eyes” and humorous shapeshifting brawls. These intertextual elements prompt audiences to revisit the first film and reflect on the continuity between both narratives, gradually familiarizing them with the updated storylines. The film also introduces new plot developments, such as Nezha’s three-stage celestial trials, which present unfamiliar challenges. Notably, the film draws on the familiar image of Nezha from Nezha Nao Hai (1979), making it easier for audiences to embrace the new plot. This fusion of nostalgia with innovation reinforces the new portrayal of Nezha and deepens the expanded world-building in popular consciousness.

3.2.3. Diversified Story Design to Meet Family-Friendly Needs

Ne Zha 2 (2025) seamlessly integrates elements of comedy, action, and drama, offering broad appeal across age groups. For children, the film’s straightforward and fast-paced plot is filled with action, clear humor, emotional highs, and a balanced rhythm that engages the audience, making it easily comprehensible even for younger viewers. For adults, the film’s narrative adaptations subtly reflect contemporary societal realities, allowing for a deeper appreciation of its nuanced plot design. For example, Nezha’s mother, Madam Yin (殷夫人), advises Nezha to “stay calm in crises,” evoking the emotional farewells of modern parents as children leave home, drawing tears from viewers. Another scene portrays Nezha’s parents, Li Jing and his wife (李靖夫妇), repeatedly requesting revisions from Feitian Pig for Nezha’s sculpture, ultimately settling on the original design—this moment mirrors the exasperating client demands in corporate settings, resonating strongly with workers. Meanwhile, the immersion brought by such identification leads the audience to experience a sense of arousal and pleasure (

Wang and Tang 2021).

3.3. Thematic Adaptation

Ne Zha originates from ancient Chinese mythology, and the values in its story differ from those of the modern era. To resonate with contemporary audiences, Ne Zha 2 (2025) has made thematic adjustments, incorporating elements of contemporary Chinese society and reality. This study focuses on Chinese society in the early 21st century, particularly the 2020s—a phase of accelerated modernization where traditional culture intersects with globalized norms. Here, “reality” refers to the tangible experiences of contemporary Chinese audiences, such as educational competition, workplace “rigidity” faced by young people, the renegotiation of intergenerational relationships within families, and the collective pursuit of balancing tradition and modernity. Notably, the narrative core of the film remains an interpretation of ancient mythological stories, never deviating from the fundamental framework of the mythological IP. It retains the fantastical elements of the myth and the essence of classic characters while subtly integrating aspects of the realistic context and value reflections of modern society. Such adaptations enable the film to establish a timeless connection with contemporary audiences by reinterpreting traditional myths to reflect these real-life experiences, thereby generating resonance.

In terms of thematic adaptation, the

Nezha films consistently explore the theme of rebellion, with a focus on evolving sociopolitical narratives. In the first film,

Ne Zha (2019), the protagonist transforms from a feudal-defying warrior into a protector of the homeland. The film shifts from depicting resistance against patriarchy and breaking away from family to emphasizing the importance of family ties and a return to familial roots. This evolution culminates in Nezha embracing modern individualism, symbolized by his iconic line “I am the master of my fate” (我命由我不由天), reflecting contemporary values of self-determination (

Shao and Li 2020). The sequel,

Ne Zha 2 (2025), amplifies the theme of rebellion, directing its critique toward systemic injustice with the powerful declaration, “If heaven’s order is unjust, I’ll overturn the cosmos” (若天理不容, 我便逆转这乾坤), challenging oppressive societal structures.

3.3.1. From “Nezha’s Rebellion Against Fate” to “A Collective Rebellion Against Fate”

At present, the image of Ne Zha in Chinese animated films differs significantly from that in the past. However, his spirit is deeply rooted in the original prototype (

Whyke and Mugica 2021). In the first film,

Ne Zha (2019), Nezha, originally fated to die as the incarnation of the Demon Pill, defies destiny by joining forces with Ao Bing to resist the Heavenly Thunder’s judgment, thereby rewriting their fates. The sequel,

Ne Zha 2 (2025), shifts the focus from individual rebellion to collective resistance, emphasizing the unification of oppressed individuals in defiance of tyranny.

In the film, Wuliang Xianweng indiscriminately captures demons to refine elixirs to strengthen the Orthodox Enlightenment Sect’s power. The Groundhog Immortal, much like ordinary people in real life, leads a simple life but faces unjust oppression. Shen Gongbao represents hardworking students and overworked professionals who put in years of effort to gain recognition. Shen Zhengdao, despite his deep reverence for the sect and founding a school to teach demon cultivation, is still persecuted by the very sect he supports. Shi Ji Niangniang, who seeks no conflict, and the dragon clans submitting to the heavens are both targeted for their formidable power. These plotlines reflect the exploitation of marginalized groups by powerful forces in real-world societies, resonating strongly with audiences who recognize the parallels to contemporary social injustices.

In the film’s climax, Nezha, Ao Bing’s family, and the Submerged Demon Clans unite to lift the Dinghai Divine Needle, breaking the cauldron and defying their fate of being turned into elixirs. Their collective resistance defeats the Monster Capture Brigade led by Wuliang Xianweng. Reflecting the values of today’s youth—who are more educated and intellectually independent, striving for social equality—this narrative sparks the audience’s fighting spirit, motivating them to challenge and change the realities they find unsatisfactory.

3.3.2. From “Anti-Patriarchy” to the Great Parental Love

In the classic

Nezha Nao Hai (1979), Li Jing embodies feudal weakness, nearly allowing Nezha to be sacrificed to the Dragon Kings, leading to Nezha’s “self-sacrifice for the father” (剔骨还父) as a radical act of anti-patriarchal defiance (

Macdonald 2015). The series

The Legend of Nezha (2003) softens this relationship—Li Jing offers his life to save Nezha. In this latest iteration, parental devotion is further intensified: Li Jing again volunteers to sacrifice himself, while Madam Yin shatters Wuliang Xianweng’s Soul-Annihilation Pill meant for Nezha. In her final moments, she embraces her son, controlled by the Heart-Piercing Curse, and is herself refined into an elixir—this moment epitomizes unconditional maternal love, moving audiences to tears. Nezha, tearing himself free from the curse with bone-shattering pain, re-enacts the “self-sacrifice for the father” act in a modern context. Reforging his body, he reunites with Ao Bing and, together with the demon clans, fights against the unjust fate imposed on them, empowered by his parents’ love.

In modern society, while parents have moved beyond feudal mindsets, rapid economic development has widened the generational gap, resulting in emotional detachment. The film portrays exemplary parental figures to encourage mutual understanding between parents and children. Beyond Nezha’s parents, the dialog between Ao Guang and Ao Bing is particularly striking. Ao Guang admits, “I placed too many expectations on you without ever truly listening. As a father, I failed you. I tried to guide you with my experiences, but now I realize that the wisdom of one generation belongs to its time, not yours. Your path is yours to forge. From now on, follow the choices that resonate with your heart.” This offers a harmonious resolution for parent–child conflicts: parents must learn to listen and let go, while children should understand their parents’ concerns driven by love yet remain true to their hearts.

3.3.3. The Philosophy of Yin–Yang Transformation in Taiji

Throughout

Ne Zha 2 (2025), the Taoist philosophy of Tai Chi’s yin–yang duality (太极阴阳)

15 is intricately woven into the narrative. Nezha and Ao Bing, originally unified as the Primordial Chaos Pearl (混元珠), represent separated yin and yang forces, symbolized by the marks on their foreheads (

Figure 6).

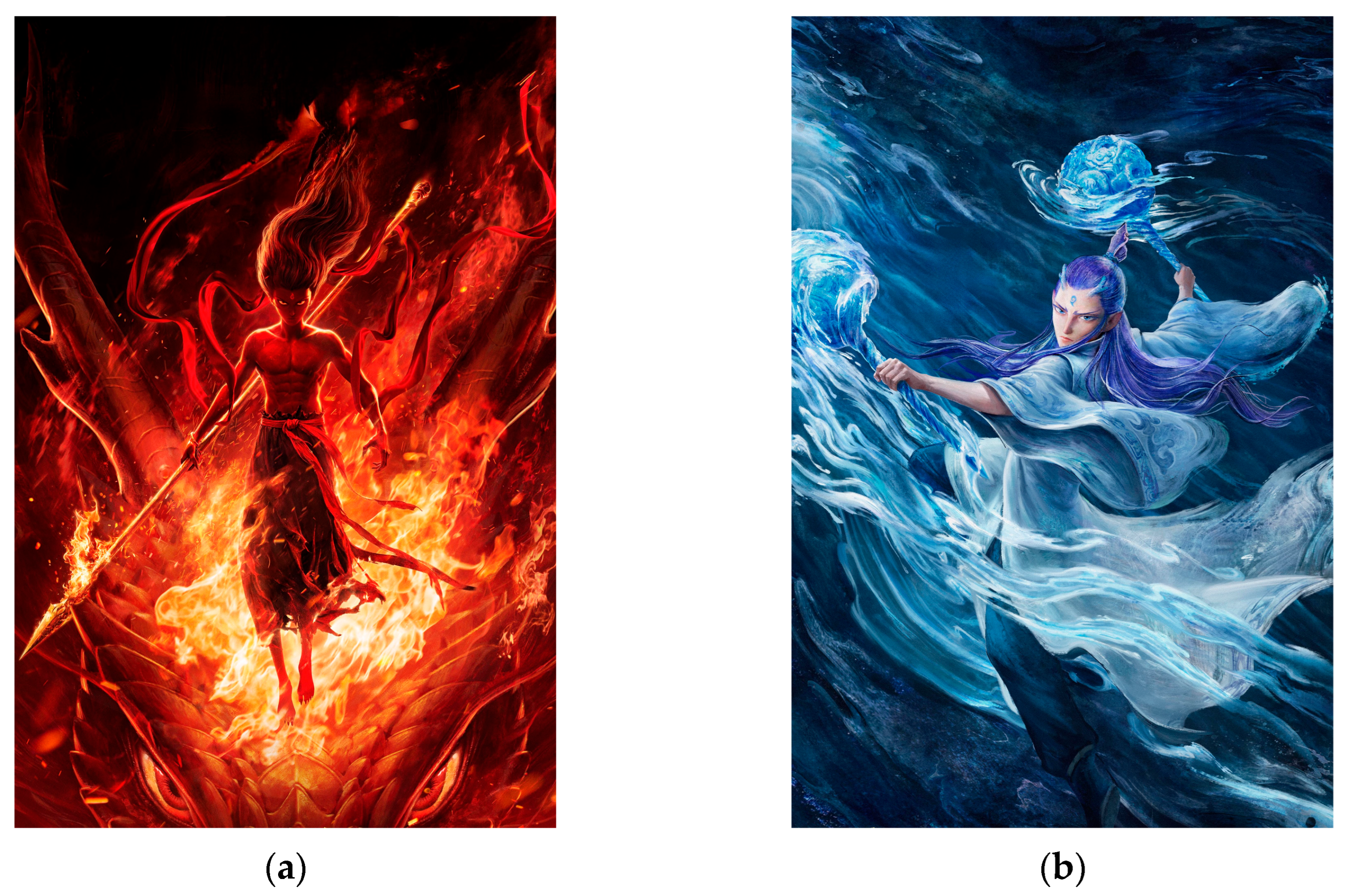

In terms of both skills and personality, Nezha embodies the essence of fire, with a fiery and impulsive nature. When he activates his ultimate skill, a raging inferno engulfs him, his body enlarges, and he transforms from a child into a more mature form. In contrast, Ao Bing represents water, embodying a gentle and compassionate nature. When Ao Bing unleashes his ultimate move, a torrent of water swirls around him in a controlled yet graceful display, reflecting his calm and nurturing strength (

Figure 7). Together, their contrasting qualities complement each other perfectly. Primordial Tianzun (原始天尊)

16 divides the Chaos Pearl into the Spirit Pearl and Demon Pill, seeking to destroy the latter with Heavenly Thunder, symbolizing society’s rejection of so-called “negative traits”—such as demonizing certain personalities, the obsession with absolute perfection, and the suppression of emotions like anxiety and fear. Yet, when Nezha and Ao Bing unite, their spinning fusion forms a Tai Chi diagram, showcasing their complementary synergy. The film conveys that no character trait is inherently good or bad; true strength lies in collaborative partnerships—whether familial, romantic, or professional—where individuals use their complementary strengths to achieve mutual success.

3.3.4. Shifting from Fixed Thinking to a Growth Mindset

In real life, people often take many things and rules for granted, developing stereotypical labels. However, these stereotypes are repeatedly challenged in the film through narrative twists and subversions, prompting deep reflection. In the previous Nezha series, characters were often depicted in a black-and-white manner, but this film presents more three-dimensional characters, highlighting their transformative arcs.

As the incarnation of the Demon Pill, Nezha is initially considered inherently evil, even marked for destruction by Heavenly Thunder. However, through the unconditional love and guidance of his parents and mentor, he sheds his demonic nature and transforms into a righteous and virtuous individual. Nezha further demonstrates his bravery by defending Chentang Pass against tyranny, embodying resistance and justice. Similarly, Sea Yaksha (海夜叉)

17 and Shen Gongbao, initially antagonists, are redeemed under the moral influence of Li Jing and his wife, ultimately joining forces to save them. This highlights the importance of postnatal environmental influences, emphasizing the potential for change in individuals. It serves as a reminder to view things objectively, maintain independent judgment, and avoid blindly following the crowd.

Many today cling to fixed mindsets or deterministic views, believing that life is hopeless and unchangeable. However, this film shows that character and virtue can be transformed—that people can undergo radical self-reinvention. When individuals strive to improve themselves and unite, they can resist tyranny and make the world a better place.

3.4. Esthetic Adaptation

In terms of esthetic adaptation, both Ne Zha (2019) and Ne Zha 2 (2025) present imaginative cinematic landscapes that deeply integrate traditional Chinese culture, reflecting the essence of Eastern esthetics. The sequel significantly enhances the visual effects, aiming to create awe-inspiring scenes that surpass audience expectations.

3.4.1. Striving for Cinematic Impact and Artistic Refinement

The film’s visuals demonstrate extraordinary precision—every character’s expression, movement, fabric texture, and even skin fuzz are rendered with exceptional clarity. As revealed in

Ne Zha 2 (2025)’s official documentary,

Breaking to Build (不破不立, 2025)

18, the production team pushed the boundaries of visual effects (VFX), doubling the number of effects shots to about 1900, delivering an unprecedented spectacle. In the Battle of Chentang Pass, millions of Submerged Demon Clans are bound by colossal chains, soaring toward the battlefield. These chains were designed to float in controlled chaos without intersecting, a remarkable technical achievement. The celestial–demon aerial clash escalates with 200 million CG entities swirling in waves and colliding, creating a visual marvel (see note 18). Nezha’s Heart-Piercing Curse sequence posed another challenge: the animation of his 600 torn flesh fragments being reassembled required meticulous frame-by-frame simulation. Every frame was painstakingly refined, greatly enhancing the film’s visual impact.

3.4.2. Incorporating Traditional Chinese Cultural Elements to Showcase Eastern Beauty

The film extensively incorporates traditional Chinese cultural elements in character design, scene setting, and music, reflecting a rich cultural heritage. In terms of character design, the Guardian Beasts (结界兽)

19 are inspired by Sichuan’s Sanxingdui archeological relics (三星堆)

20, while Ao Guang’s blade is modeled after the traditional Guandao (关刀)

21. Regional dialects are used to match the characters: Taiyi Zhenren speaks the Sichuan dialect, and the Octopus Demon uses the Tianjin dialect. Ao Bing employs Wing Chun (咏春)

22 martial arts, emphasizing traditional combat techniques. In terms of scene-setting, the crane scene in the Yuxue Palace draws inspiration from Emperor Huizong of Song’s painting,

Auspicious Cranes (瑞鹤图)

23. In terms of music, Dong ethnic music (侗族音乐)

24 accompanies the lotus blooming sequences, while Mongolian throat singing (蒙古呼麦)

25 amplifies the oppressive atmosphere of the Celestial Cauldron. Every detail is meticulously crafted to celebrate Chinese cultural heritage, embodying Eastern esthetics and effectively boosting cultural confidence among the audience.

4. Film Discussion

In filmmaking, sequels often face the sequel curse, yet Ne Zha 2 (2025) not only breaks this curse but also achieves a huge breakthrough. Its success is no coincidence. It is the result of efforts and breakthroughs from the entire animation industry. Good work naturally gains the love and support of the audience.

4.1. Industry Collaboration: Supporting Adaptation Strategies and Cultural Preservation

The previous section has analyzed the adaptation strategies of Ne Zha 2 (2025) from four dimensions: character, plot, theme, and esthetics, and the successful implementation of these strategies cannot be separated from the technical support of industry collaboration. This film was produced through a collaboration of 138 Chinese animation studios, analogous to the dragon clans in the story, who dedicate their strongest scales to forging Ao Bing’s Dragon Scale Armor (see note 18). The project brought together top-tier talent and cutting-edge animation technologies. Over five years, the production team overcame numerous challenges, meticulously refining 1900 VFX shots with steadfast dedication to creating a groundbreaking masterpiece (see note 18). Audiences were drawn to its stunning visuals, compelling, multidimensional characters, and captivating storyline, leading to widespread acclaim and organic promotion on Weibo and other platforms.

Industry-wide collaboration not only supports technical implementation but also underpins cultural preservation. The studios formed a network integrating cultural research, technical development, and creative execution: cultural heritage teams verified the cultural essence of traditional symbols, while animation technicians translated these into visual languages—for instance, refining Ao Bing’s Dragon Scale Armor to reflect both ancient craftsmanship and the mythic symbolism of “collective sacrifice”. This cross-disciplinary collaboration ensured cultural elements were embedded into the narrative core; integrating Dong ethnic music into lotus rebirth scenes, for example, required coordination between ethnomusicologists and sound designers to preserve musical characteristics while aligning with plot rhythm. By pooling expertise across fields, the collaboration transformed fragmented cultural elements into a coherent, living text, enabling traditional heritage to transcend boundaries through cinematic innovation—proving that industrial synergy revitalizes cultural diversity.

4.2. Audience Feedback: Fostering Emotional Resonance in Adaptation

Adaptation transcends mere adjustments to characters, plot, theme, and esthetics; it must also resonate with audiences’ emotional needs to achieve true success. This emotional experience prompts viewers to openly share their thoughts, experiences, and emotions with friends or online acquaintances after watching the movie (

Tettegah and Espelage 2015).

After the release of the first film, fans requested a backstory for Shen Gongbao’s family, which was seamlessly incorporated into the sequel. This inclusion responded directly to audiences’ desire to understand complex motivations. Its plot Easter eggs, like the recurring “missing dragon scales”, tapped into viewers’ nostalgia for the first film, satisfying their need for engagement and discovery. Thematically, the shift from “individual rebellion” to “collective resistance” mirrored contemporary audiences’ yearning for solidarity, while its esthetic blend of traditional symbols (e.g., lotus rebirth) with modern visuals stirred pride in cultural heritage. For every CNY 100 million in box office earnings, Director Yang Yu releases playful spin-off posters as Easter eggs (see note 12). The posters were based on fan trends—further reinforcing a bond of mutual recognition, making audiences feel seen and valued. Discussions about Ne Zha 2 (2025) on social media have generated viral trends, which the director actively embraces—for instance, creating a poster of Spirit Pearl Nezha with comically short legs (unable to reach Shen Zhengdao’s head) in response to a fan’s creation. Audiences further fuel the phenomenon through fan art, street murals, and official merchandise, creating significant economic value. In essence, the most impactful adaptations do not stop at formal innovation; they weave emotional threads that connect the IP to viewers’ lived experiences, turning passive consumption into active emotional investment.

5. Conclusions

In the realm of IP adaptation films, reconciling audiences with subversive reinterpretations of familiar characters remains a persistent challenge. Ne Zha 2 (2025) provides a groundbreaking solution—it validates established adaptation strategies while introducing innovative approaches. As society progresses, cinema must evolve. The film skillfully balances intertextuality and innovation, retaining familiar character elements while reimagining them through multidimensional character development, intricate plot twists, contemporary themes, and stunning esthetics. This fusion of tradition and innovation creates a unique intertextual dialog, offering both nostalgic familiarity and radical reinvention. This exemplary literary IP adaptation not only achieved critical acclaim and box office success but also advanced artistic innovation, cultural preservation, and the growth of the film industry.

Firstly, in terms of character adaptation, Ne Zha 2 (2025) successfully transcends traditional stereotypes through multidimensional and subversive character depictions. The film presents classic figures like Nezha and Ao Bing with more layered and complex depictions, moving beyond simplistic labels such as “rebellious” or “righteous” to align with the psychology and values of modern viewers. This approach—deepening and reconstructing character traits while honoring their traditional essence—provides crucial guidance for adapting traditional stories into visual works: striking a balance between nostalgic sentiments and innovative expression.

Secondly, in plot adaptation, the film realizes a harmonious unity of inheritance and innovation through close continuity with its predecessor and narrative innovation. By embedding multiple plotlines and enriching narrative threads, Ne Zha 2 (2025) not only enhances the story’s tension and appeal but also expands its audience across age and cultural boundaries. For future sequels or rebooted works, this strategy—preserving the core of the original while incorporating fresh content—can effectively attract both new and existing audiences, achieving dual success in commercial and artistic terms.

Thirdly, at the level of thematic adaptation, the film evolves from the first installment’s focus on “individual resistance against fate” to “collective rebellion against destiny,” embodying deeper social values and humanistic care. This thematic elevation not only resonates with the collective spirit advocated in contemporary society but also strengthens emotional engagement with audiences. Future IP adaptations that integrate traditional themes with the spirit of the times will undoubtedly gain greater cultural depth and communicative power.

Finally, in esthetic adaptation, Ne Zha 2 (2025) reaches new heights in integrating visual effects, scene design, and traditional cultural elements. The film not only showcases stunning visual spectacles enabled by technological advancements but also embeds numerous distinctively Chinese cultural symbols in its details—such as traditional architecture, costumes, colors, and totems. This approach of presenting traditional esthetics through innovative technology not only boosts cultural confidence but also offers global audiences a new window into understanding Chinese culture.

Overall, the adaptation strategies of Ne Zha 2 (2025) provide a successful model for future IP development in film and animation. Both domestically and globally, this approach—emphasizing both intertextuality and innovation—offers a sustainable path for the contemporary interpretation of traditional cultural IPs. Drawing on Ne Zha 2 (2025)’s experience, future creators can inject elements aligned with contemporary values while respecting tradition and preserving cultural essence, allowing traditional stories to continuously rejuvenate across diverse cultural and temporal contexts, thereby achieving widespread cross-generational and cross-cultural dissemination and resonance.