1. Introduction

Like language or history, landscape is a full marker of identity, a common home. And there are no landscapes forever. They are the record of a society that changes, and if the change is so great, so deep and accelerated, there will be signs of it, beyond a little time and plenty of space to understand or digest the marks and ways they are trampling each other, sometimes relics, sometimes debris.

The fishing neighbourhood of Paramos, located in the municipality of Espinho, approximately 30 km south of Porto, offers a paradigmatic example of urban fragmentation and identity ambiguity observable in several coastal settlements. Its landscape, deeply shaped by the juxtaposition of military infrastructure, leisure facilities, remnants of fishing activity, and imposed territorial boundaries, constitutes a palimpsest of conflicting memories and uses.

Historically, Paramos was one of many territories affected by the socio-demographic transformations that occurred in Portugal throughout the 20th century. The country was governed by a dictatorial regime between 1933 and 1974, a period that led to a developmental lag still visible today, especially in more isolated regions. According to

Barreto (

2007), from the 1960s onwards, Portugal underwent an intensified process of coastal migration, with inland rural populations relocating to the coastal belt between Setúbal and Braga. This movement, combined with the massive emigration of approximately one and a half million Portuguese citizens in search of better living conditions, resulted in the development of urban settlements marked by informal and precarious urbanisation, such as Paramos.

Few institutions reached all inhabitants, cities were small, local communities were isolated units, there was no national transport network, women mostly worked within their households, schools did not exist in every locality, public services failed to cover large portions of the country, communication was difficult, and markets represented the main form of commerce.

According to local tradition—often attributed to a romanticised imaginary traceable to Alexandre Herculano in Portugaliae Monumenta Historica—the toponym “Paramos” may derive from the verb “to stop”, in the expression “Here we stop!”, uttered by a nobleman mesmerised by the coastal scenery of the place. What was once a voluntary point of arrival has today become a space of enforced permanence, confined between the beach, a military airfield, and a wastewater treatment plant.

The construction of the railway in 1863, which physically divided the parish, alongside the installation of military structures and technical infrastructures during the Estado Novo (

Pereira 1970, pp. 45–46), contributed to discontinuous and fragmented occupation of the urban land. The successive transformations of the landscape have eroded the social fabric and collective identity, replacing the former fishing-based community life with a silent coexistence of ageing residents, military presence, and memories of the past.

This article stems from a visual essay based on direct observation and photographic documentation of the site. It proposes a critical reading of Paramos’s territorial and symbolic construction. Photography here is not only employed as a recording tool, but also as a medium for interpreting and questioning spatial and urban reality, as evidenced in the visual sequence developed throughout

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

3. Discussion

Framed by a

peripatetic3 narrative constructed through the photographic sequence, the neighbourhood of Paramos is characterised by the juxtaposition of dissonant elements: an aerodrome, a dirt football field, a wastewater treatment plant, a golf course, a military barracks, and the decaying remains of the fishing industry. These elements coexist within a confined area, generating both physical and symbolic barriers that undermine the construction of meaningful social relations and reinforce spatial segregation.

Figure 1.

The fence enclosing the airfield runway. The metal fence emerges as a diffuse control element, concealing a technical infrastructure within an apparently naturalised setting (Marum 2021).

Figure 1.

The fence enclosing the airfield runway. The metal fence emerges as a diffuse control element, concealing a technical infrastructure within an apparently naturalised setting (Marum 2021).

The airfield runway, enclosed by an ostensibly innocuous fence, materialises a spatial control device in Foucault’s sense (

Foucault 1980) (see

Figure 1)—an invisible yet effective mechanism of exclusion. Far from being a mere technical element, this fence acts as an

actant (

Latour 2005), shaping relationships of mobility and access. As

Lefebvre (

2006) argues, these physical elements produce social space, articulating the lived and the conceived. The fence’s silent presence reinforces territorial fragmentation, serving as a symbolic barrier that contributes to a pervasive sense of isolation. As

Domingues (

2012) points out, it is within the banality of physical boundaries that the most enduring strategies of territorial control are often revealed.

Figure 2.

View of the main access road to the fishing neighbourhood of Paramos (Marum 2021).

Figure 2.

View of the main access road to the fishing neighbourhood of Paramos (Marum 2021).

The main street provides access to the fishing neighbourhood of Paramos (see

Figure 2), characterised by a linear layout and a lack of public life, which emphasises the condition of social isolation.

The access road’s absence of public life and the football field’s dissonant coexistence with aviation and housing reflect Augé’s concept of non-place, a space defined by transience, infrastructural dominance, and a lack of meaningful social exchange.

Figure 3.

The dirt football field adjacent to the airfield (Marum 2021).

Figure 3.

The dirt football field adjacent to the airfield (Marum 2021).

The juxtaposition of dissonant uses (see

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10)—sport, aviation, and informal housing—underscores the absence of urban infrastructure and highlights the precariousness of the spatial structure, revealing unplanned and spontaneous forms of collective space use.

Figure 4.

A view of the wastewater treatment plant (Marum 2021).

Figure 4.

A view of the wastewater treatment plant (Marum 2021).

The presence of the wastewater treatment plant at the heart of the Paramos neighbourhood functions as a heterotopia in the Foucauldian sense (

Foucault 1967) (

Figure 4)—an “other space” that concentrates undesirable functions and simultaneously renders social control visible through symbolic and functional segregation. Its sensory, visual, and olfactory impacts inscribe a territorial mark of repulsion, configuring a geography of stigma and exclusion. The proximity between this technical infrastructure and the nearby dwellings reveals a latent urban conflict, in which vulnerable communities are forced to inhabit the fringes of urban systems that remain invisible to the rest of the city. In this context, resistance emerges as a form of permanence—silent yet political—within a hostile landscape. It is an element of strong visual and olfactory presence, where its proximity to housing defines a territory of exclusion and resistance.

These technical infrastructures act not merely as the background but as active participants in the network of spatial production (what Latour defines as actants) shaping human behaviour, visual experience, and territorial exclusion.

Figure 5.

A view of the wastewater treatment plant with houses and fishing boats in the background (Marum 2021).

Figure 5.

A view of the wastewater treatment plant with houses and fishing boats in the background (Marum 2021).

These elements coexist within a limited space, creating physical and symbolic barriers that hinder the development of meaningful social relationships. The view of the houses facing the airfield runway eloquently reveals this dysfunctional overlap of uses, where irregular paving and a fragmented horizon illustrate the lack of urban cohesion and the indeterminacy of the built fabric. As

Sennett (

2020) notes, cities shaped by closed and disconnected infrastructures tend to inhibit the formation of lasting community bonds. In Paramos, this condition is amplified by the overlapping of dissonant functions—housing, militarism, and recreation—producing a territory where, as

Lefebvre (

2006) would argue, the production of space is shaped by contradictory and fragmented logics.

This latent infrastructure functions, in Latour’s terms, as an actant shaping collective behaviours and perceptions.

Figure 6.

An isolated streetlight in a vacant urban area with the airfield in the background (Marum 2021).

Figure 6.

An isolated streetlight in a vacant urban area with the airfield in the background (Marum 2021).

This image (

Figure 6) reveals spatial emptiness and the dispersion of infrastructural elements. A solitary streetlight stands out on the vacant terrain, reinforcing the perception of discontinuity and a territory only partially urbanised, where the airfield in the background asserts itself as both a symbolic and physical element of separation.

Figure 7.

The “Praia de Paramos” signage next to the military barracks wall. The overlap of the leisure infrastructure, physical barrier, and drainage system expresses the tension between a tourist-oriented vocation and spatial control (Marum 2021).

Figure 7.

The “Praia de Paramos” signage next to the military barracks wall. The overlap of the leisure infrastructure, physical barrier, and drainage system expresses the tension between a tourist-oriented vocation and spatial control (Marum 2021).

This tension between the tourist discourse and military control is made visible in the coexistence of a recently installed red cycle path, tall military perimeter walls, and open-air drainage systems. This juxtaposition reveals what

Graham (

2011) refers to as an “aesthetic of militarisation” (see

Figure 7), where strategies of mobility and leisure coexist with mechanisms of exclusion and surveillance. Similarly,

Zukin (

1995) observes that the symbolic reconfiguration of space through cultural or touristic elements can operate as a mechanism for the domestication of public space.

The cycle path and signage reflect an attempt at the cultural domestication of public space, aligning with Zukin’s notion of symbolic economy, where aesthetics is deployed to mask structural inequities and to recode space for leisure or tourism. At the same time, the juxtaposition of military infrastructure with recreational elements creates what Graham identifies as an aesthetic of militarisation, where control and surveillance are visually normalised under the guise of accessibility.

Figure 8.

The chapel at the opposite end of the previous image, built atop the coastal wall, highlighting the liminal nature of the site (Marum 2021).

Figure 8.

The chapel at the opposite end of the previous image, built atop the coastal wall, highlighting the liminal nature of the site (Marum 2021).

The isolated presence of this religious building underscores the liminal nature of the site—between the sacred and the sea, between inhabited territory and the infinite (see

Figure 8). This relationship between technical fragments and diffuse edges culminates at the westernmost edge of the neighbourhood, where the urban fabric dissolves onto the coastal wall. The chapel, built there and standing alone before the ocean, appears suspended between sanctity and abandonment, reinforcing the liminality of Paramos—a threshold space between permanence and dissolution.

With the decline of

xávega art and the significant wave of emigration, the resident population is now composed mainly of elderly people, retired fishermen, and military personnel (

Nunes 2006). The lack of active public spaces and the degradation of the built landscape reinforce a sense of isolation and absence of belonging. In this context, alternative forms of identity expression emerge—often implicit in subtle signs or spontaneous inscriptions.

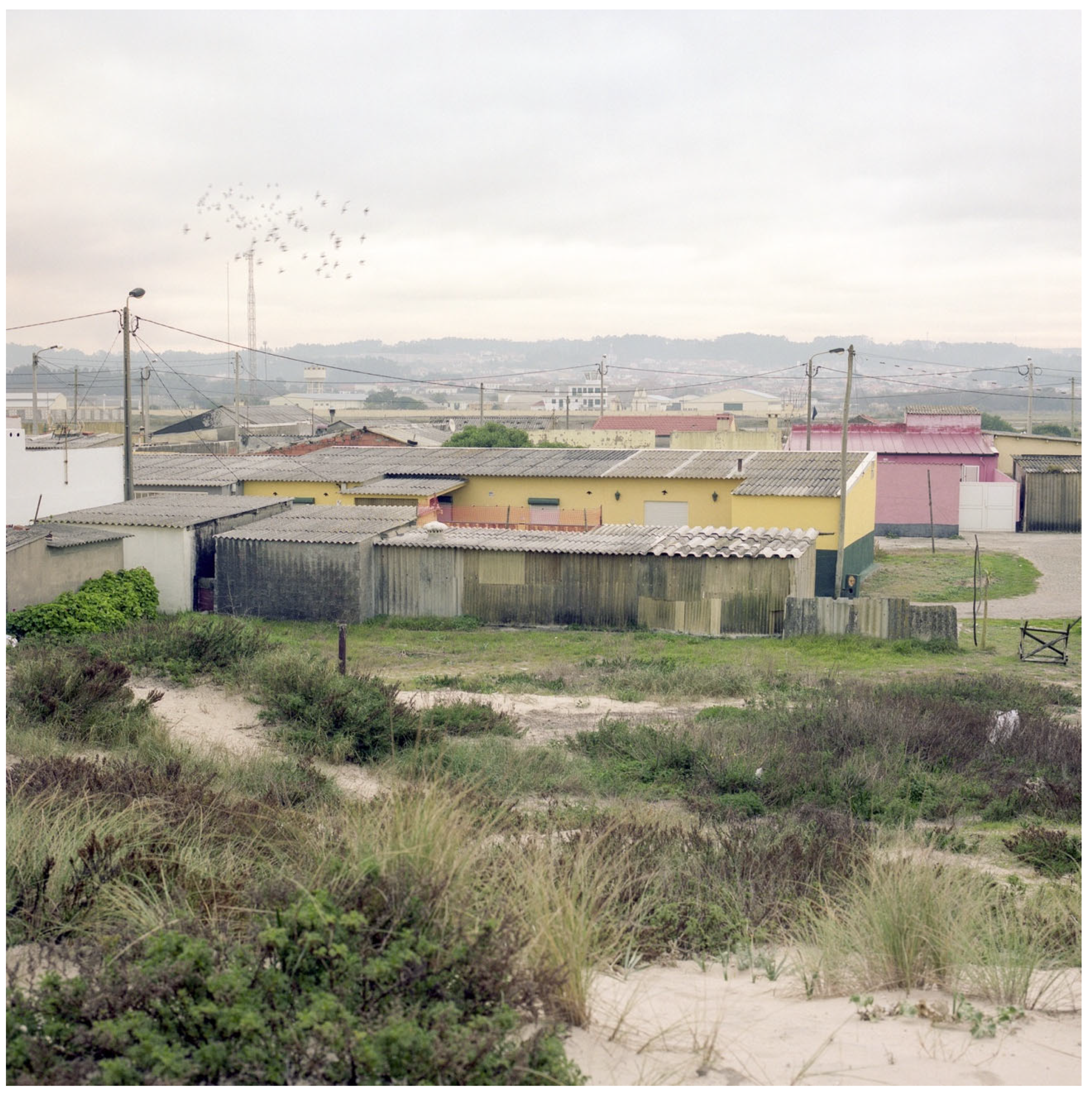

Figure 9.

Precarious dwellings on the dunes, painted in saturated colours (Marum 2021).

Figure 9.

Precarious dwellings on the dunes, painted in saturated colours (Marum 2021).

The dwellings possess expressions of individual spatial appropriation and attempts at symbolic affirmation in a context of collective abandonment.

These dwellings, while precarious, reveal an aesthetic agency often overlooked in formal urban readings. Their vivid colour schemes (see

Figure 9) resist the invisibility typically imposed on marginal housing. Drawing on Sharon Zukin’s idea of the symbolic economy, this informal vernacular aesthetic counters the homogenising tendencies of regulated urbanism. Rather than passive signs of decay, these structures represent micro-strategies of survival and self-expression, carved out of exclusion.

Figure 10.

An interior courtyard with an abandoned vehicle (Marum 2021).

Figure 10.

An interior courtyard with an abandoned vehicle (Marum 2021).

The presence of obsolete or unused objects carries a layered narrative of stagnation, resistance, and domestic memory. These items, often left to decay in backyards, on patios, or in forgotten corners, evoke the suspended temporality of a place that has ceased to evolve within dominant urban logics. Their enduring presence speaks to a kind of spatial resilience, where abandonment does not equate to erasure, but rather, to a silent occupation of the margins. As traces of previous uses and lived experiences, they function as informal archives of the everyday, articulating a domestic resistance that asserts presence in the face of institutional neglect. In Paramos, these remnants become silent testimonies of personal histories and attachments, embedded in the urban fabric as both memory and defiance.

Figure 11.

Façade with decorative elements and popular tiling (Marum 2021).

Figure 11.

Façade with decorative elements and popular tiling (Marum 2021).

The uniqueness of the ornamentation evokes fishing and religious imaginaries, suggesting identities that remain active within the symbolic sphere. These decorative gestures, often expressed through traditional azulejos, maritime motifs, and devotional elements, resist the homogenisation of space imposed by urban standardisation. They act as quiet affirmations of belonging, rooted in both collective memory and individual expression. In Paramos, such ornamentation functions not only as aesthetic embellishment but also as a cultural code, sustaining narratives of identity and continuity in an otherwise marginalised urban environment.

These gestures of ornamentation and local expression (see

Figure 11) become mnemonic devices, what Hayden describes as spatial inscriptions of collective memory, marking resistance within an otherwise eroded landscape.

The neighbourhood of Paramos reveals a dominant spatial identity shaped by exclusion, ageing, and infrastructural conflict, yet this narrative is continually contested by minor gestures, symbolic appropriations, and residual memories that suggest the presence of alternative, more nuanced territorial subjectivities. Rather than assuming a singular or fixed identity, we understand identity here as a field of tension, a negotiated and sometimes reluctant condition, oscillating between abandonment and resilience.

Figure 12.

Abandoned buildings with “FCP” graffiti (Marum 2021).

Figure 12.

Abandoned buildings with “FCP” graffiti (Marum 2021).

The “FCP” (Futebol Clube do Porto) graffiti painted on the door of an abandoned building in the centre of the neighbourhood (see

Figure 12) illustrates a symbolic act of territorial appropriation, revealing how support for a football club can serve as a marker of local identity in a context of eroded collective references. This kind of inscription functions as a trace of resistance and emotional belonging, standing in contrast to institutional silence and the progressive marginalisation of the area.

Figure 13.

Traditional xávega art fishing boats on the sand, beside supporting fishing structures (Marum 2021).

Figure 13.

Traditional xávega art fishing boats on the sand, beside supporting fishing structures (Marum 2021).

The final vestiges of local fishing activity (see

Figure 13) now stand in contrast with the abandonment of supporting infrastructures.

Xávega art, a traditional drag-net fishing technique once widespread along Portugal’s central coast, has seen a significant decline throughout the twentieth century. This decline stemmed from factors such as the modernisation of fishing technologies, changes in marine resource management policies, and shifts in local economic dynamics. As

Nunes (

2006) highlights in his anthropological study, the beaches of Paramos and Esmoriz were historically uninhabited during the winter, with fishermen migrating seasonally. Over time, these communities became permanently settled, but the demise of

xávega art contributed to the reduction in traditional fishing activity and to changes in the local demographic composition.

The images captured reveal the emptiness, irony, and banality of the place. The photographs function as critical devices, exposing the tension between the lived and the represented, between abandonment and the desire to remain. In this way, the visual narrative becomes a mode of symbolic reinscription of the place.

Figure 14.

Stairs ending in the sand, disconnected from the sea (Marum 2021).

Figure 14.

Stairs ending in the sand, disconnected from the sea (Marum 2021).

The stairs shown in

Figure 14 represent a symbol of the disconnection between function and use, the absence of continuity, and the erosion of both physical and symbolic territory.

Figure 15.

A drainage ditch alongside the main road (Marum 2021).

Figure 15.

A drainage ditch alongside the main road (Marum 2021).

Rendered invisible in official discourse, these structures reveal an everyday reality where precariousness is systematically managed through patchwork solutions. Drainage ditches, makeshift repairs, and improvised infrastructural elements speak to a form of urban maintenance driven not by planning but by necessity. These interventions, often ephemeral and improvised, are material manifestations of exclusion, traces of a population left to negotiate the conditions of inhabitation with limited resources and institutional support. In Paramos, such elements constitute a vernacular infrastructure of survival, where the residents’ responses to systemic neglect expose the failures of formal governance.

4. Materials and Methods

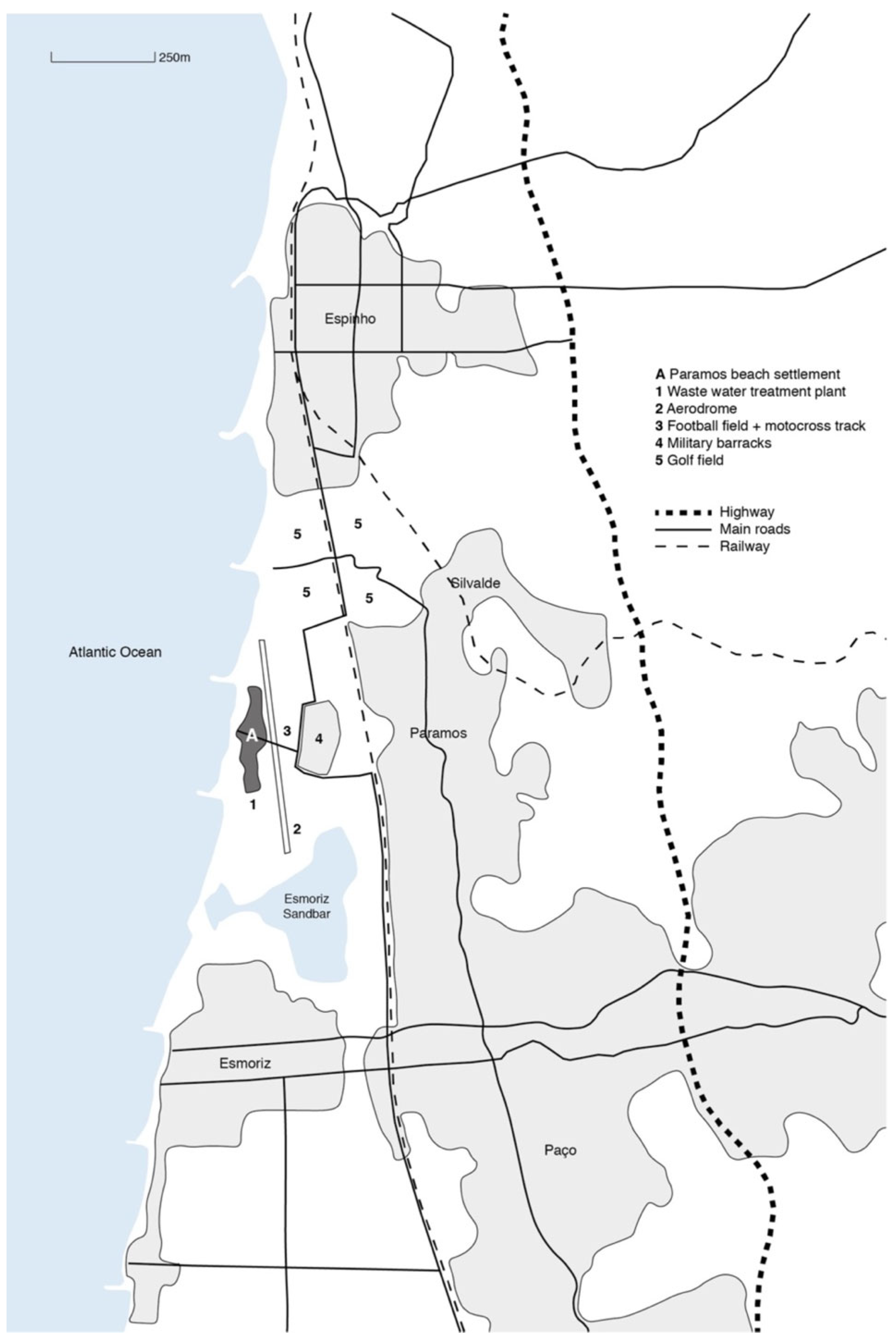

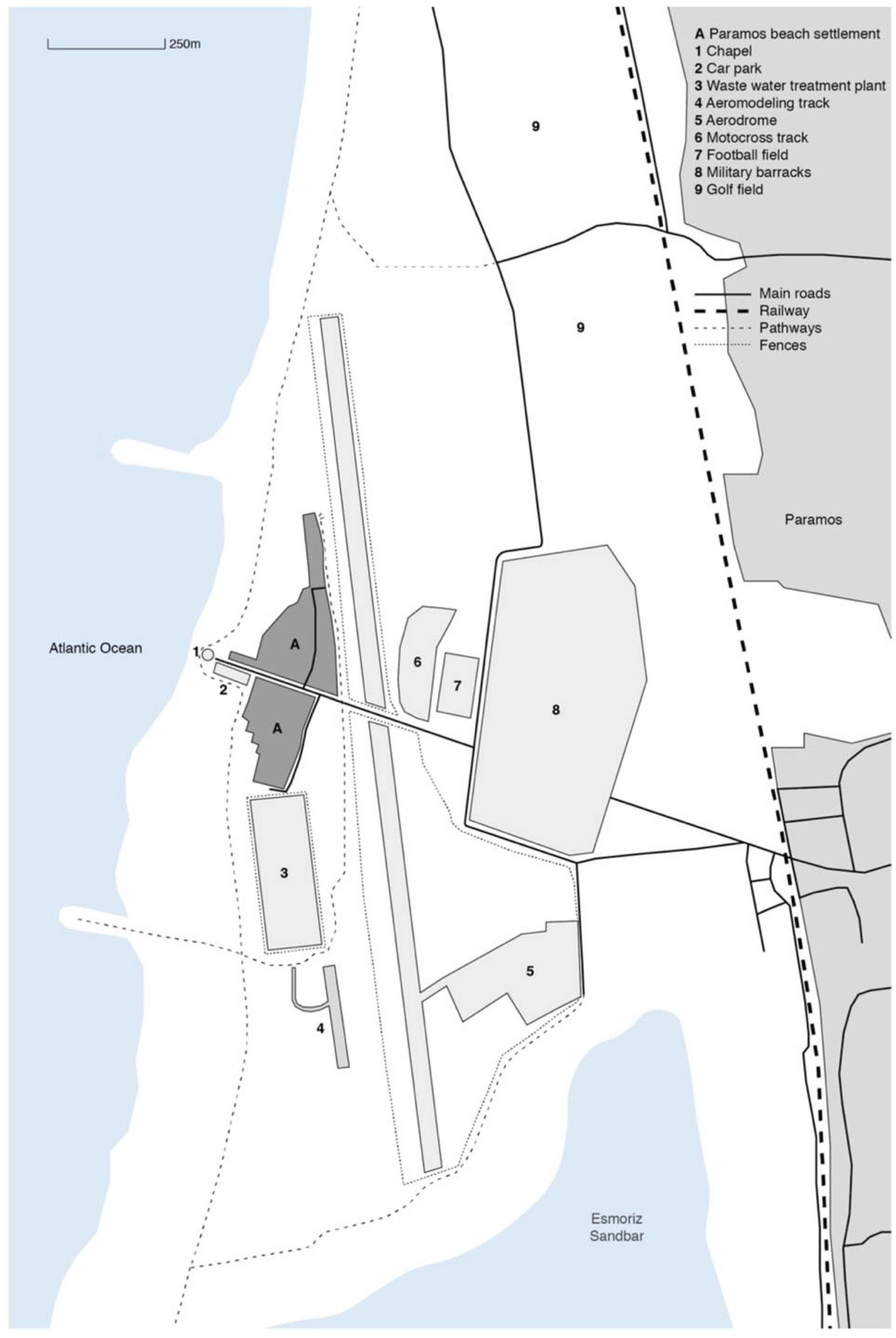

Our fieldwork consisted of site visits to the neighbourhood and the production of a photographic essay with a narrative structure. Through a critical itinerary, the main spatial elements were mapped, from the intersection near the military barracks to the chapel overlooking the beach. To better understand the spatial configuration and territorial boundaries of the settlement, two cognitive maps are presented, based on fieldwork and direct observation (Marum and Neto 2022).

Figure 16 situates Paramos within the regional context, highlighting its relationship with surrounding infrastructures.

Figure 17 provides a detailed representation of the neighbourhood’s internal morphology, identifying key built elements and their physical and symbolic articulations.

The photographic campaign consisted of four site visits between March and October 2021. The resulting photographs, presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, follow a narrative logic that echoes the spatial itinerary—from the military perimeter to the coastal limit, revealing visual markers of fragmentation, exclusion and resistance. While no direct interviews were conducted and no identifiable persons appear in the visual material, the ethical decision to avoid portraiture reflects an intentional focus on the spatial materiality of everyday life. The authors’ position, while external, is informed by prior work in the region and a familiarity with similar territorial conditions. The approach was observational and interpretive rather than participatory, acknowledging the limits of representation while striving to reveal latent dynamics through visual and cartographic means.

Cognitive mapping is adopted as a methodological tool complementary to photography, aiming to represent how the territory of Paramos is perceived, experienced, and narrated. Inspired by the concept developed by

Lynch (

1999), this approach privileges a subjective and experiential reading of space, incorporating perceptions, memories, and emotional connections. Rather than merely describing the neighbourhood’s physical morphology, the cognitive maps produced here aim to reveal latent dynamics, such as mechanisms of exclusion, everyday paths of resistance, or tensions between different land uses and territorial agents. This methodological exercise is especially relevant in a fragmented and ambiguous context like Paramos, where spatial practices and the meanings attributed to place are often contradictory or rendered invisible by formal planning instruments.

The photographic sequence served as the foundation for the spatial and symbolic interpretation of the site. The critical reading of the territory was developed through the analysis of a photographic series documenting different areas of the fishing neighbourhood. The images were grouped according to three main interpretative axes—fragmentation and territorial control, hesitant identity, and photography as a critical tool—aligning with the theoretical concepts discussed in the previous section. Each image is accompanied by an analytical caption, allowing for a simultaneously visual and textual reading of the territorial complexity of Paramos.

Complementing the fieldwork and photographic series, interpretative cartographies were developed to deepen the reading of Paramos as a fragmented, heterogeneous, and liminal territory. Like photography, cartography is employed here not merely as a representational tool but as a critical and operative instrument—a way of thinking and revealing the complexity of existing spatial and social systems.

The first cartography presents an overview of the Paramos beach settlement, highlighting the juxtaposition of contrasting infrastructures—such as the airfield, wastewater treatment plant, football field, golf course, and military barracks—within a territory that is simultaneously coastal, industrial, and militarised. The overlap between technical facilities, informal uses, and precarious housing reveals a pattern of unplanned, discontinuous appropriation that reinforces the sense of identity paradox and lack of centrality, a direct consequence of its linear configuration.

The second cartography proposes a morphological reading of the settlement, drawing attention to the internal fragmentation of the neighbourhood and the discontinuity of the urban fabric. Fences, interrupted paths, voids, and fluid boundaries reinforce the idea of a hesitant territory—a condition mirrored in the multiplicity of architectural languages, scales, and forms of occupation.

Both cartographies, produced by Marum and Neto (2022), were fundamental in informing and structuring the photographic essay’s itinerary. They served not only as a base for positioning the camera but also as a tool for understanding the spatial tensions that traverse this urban enclave.

The photographic essay follows the tradition of documentary landscape photography, informed by a research-driven aesthetic. Choices regarding framing, timing, and sequencing were guided by a critical reading of the territory’s spatial and symbolic tensions. This practice, in turn, was shaped by theoretical inputs, allowing the images to function both as data and interpretation.

5. Conclusions

The fishing neighbourhood of Paramos constitutes a liminal territory, where fragmented landscapes, fading memories, and infrastructures that silently regulate the use and meaning of space intertwine. Far from fitting into traditional dichotomies such as urban/rural, planned/informal, or central/peripheral, Paramos reveals a hybrid reality, marked by overlapping spatial regimes and a persistent tension between appropriation and exclusion.

Through the articulation of documentary photography and cognitive mapping, this article proposed a critical reading that transcends mere physical description. The photographic images, as both a methodological and analytical tool, enabled access to layers of meaning often obscured in official discourse and normative representations of the territory—a space captured and problematised through a visual narrative of tension and absence (see

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15). Similarly, the interpretative maps served as instruments for uncovering the logics underlying occupation, control, and spatial symbolism.

The evidence gathered points to a hesitant territorial identity—not grounded in institutional symbols or consolidated forms of belonging, but rather, articulated through small gestures, ephemeral inscriptions, and everyday forms of resistance. The case of Paramos demonstrates how spatial and symbolic marginality can operate both as a condition of vulnerability and a potentiality—as a space of exclusion, but also one of experimentation and reimagination.

This reading does not seek to propose direct interventions, but rather, to reframe the way we observe and interpret marginal territories. Through the integration of documentary photography and cognitive mapping, the study foregrounds alternative narratives and silent agencies that resist normative spatial discourse. Rather than suggesting architectural solutions, it highlights how fragile materialities and dispersed subjectivities challenge dominant notions of urbanity and spatial value.

In short, Paramos is here proposed as a paradigmatic case of an “in-between space”—a non-place where ambiguity is not a flaw but the expression of a contested territory, marked by interrupted stories and futures yet to be imagined. It is within this interval—between ruin and permanence, between the visible and the concealed—that space is opened for a critical and situated architecture, attentive to the fragile materialities and dispersed subjectivities that compose the real.

In Paramos, perhaps the most urgent form of architecture is the one that knows how to wait, observe, and remain.