2. Spinning Technologies, Eve, and Mary

A preliminary discussion of the technology of spinning, with an emphasis on the shift from spindle and distaff to spinning wheel, is necessary to establish the prevalence of this subject in the visual arts. The imagery discussed here is very specific and assumes that the viewer would have some knowledge of this skill that has now become obsolete.

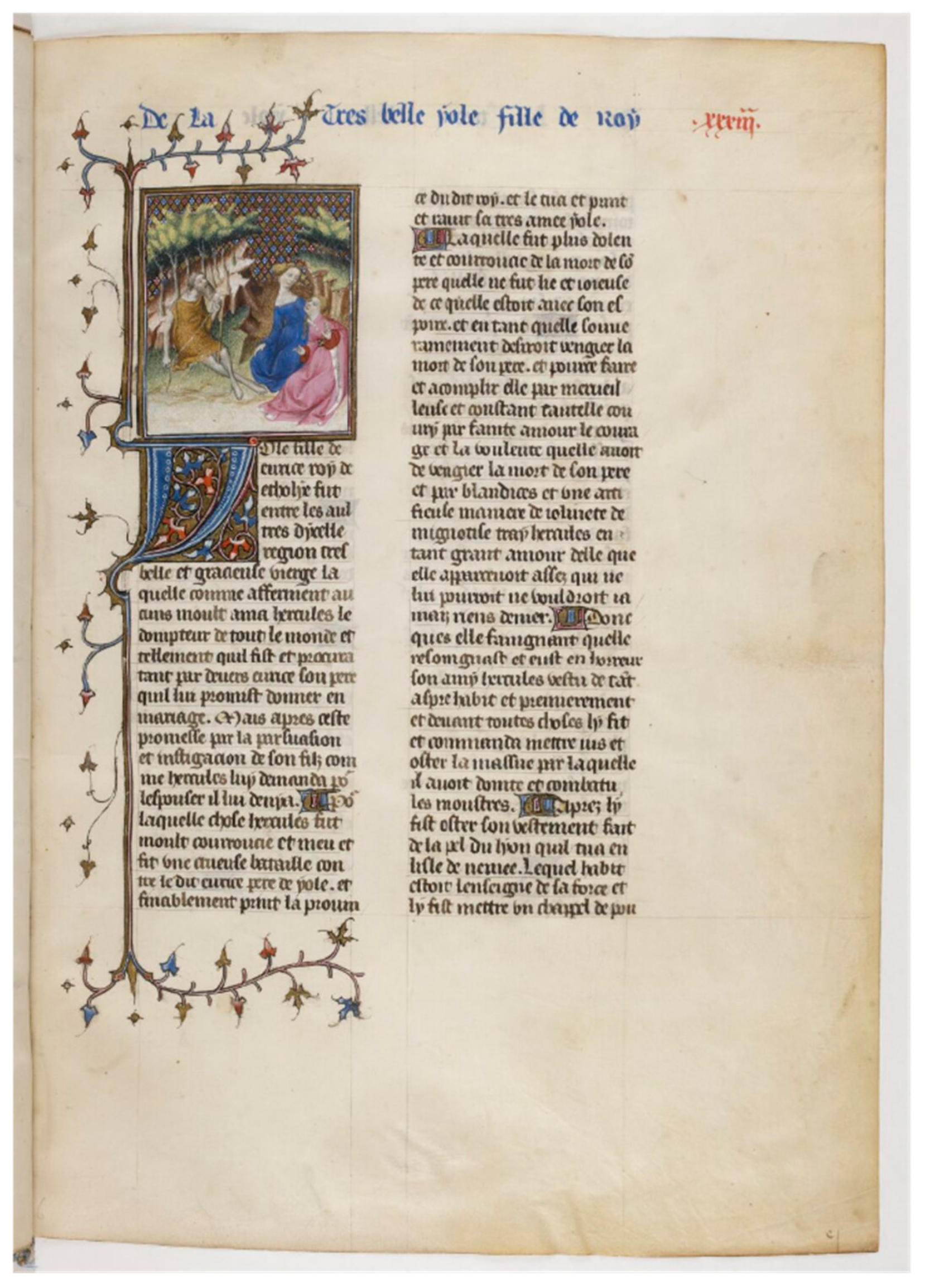

1 Looking at an image of Eve from an illustrated copy of the

Speculum Humanae Salvationis (1360), after the Expulsion, all of the key tools are clearly on display (

Figure 1).

2 She spins with a drop spindle and distaff, a method that was common during the Middle Ages but is not part of the text in the Old Testament.

Eve’s role in the early chapters of Genesis is communicated in terms of her fraught relationship with Adam. The couple live naked and unashamed in the Garden of Eden after her creation from one of Adam’s ribs.

3 The serpent tempts her and convinces Eve to consider the fruit from the forbidden tree, and she “saw that the tree was good to eat, and fair to the eyes, and delightful to behold: and she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave to her husband who did eat.”

4 Then, problems begin. Once their eyes are “opened”, they become immediately ashamed of their nakedness. God finds them hiding and questions Adam, who blames Eve, who blames the serpent. God then curses the serpent, “upon thy breast shalt thou go, and earth shalt thou eat all the days of thy life”; then, in Genesis 3:16–17, he curses both Adam and Eve before finally casting them from the Garden, saying,

“To the woman also he said: I will multiply thy sorrows, and thy conceptions: in sorrow shalt thou bring forth children, and thou shalt be under thy husband’s power, and he shall have dominion over thee. And to Adam he said …with labour and toil shalt thou eat thereof all the days of thy life.”

5Adam then names his wife Eve “because she was the mother of all the living”.

6 After the curse, God clothes Adam and Eve with “garments of skins” and sends them “out of the paradise of pleasure.”

7The textual narrative from Genesis was visualized and expanded during the medieval period to show Eve at work spinning, usually out of doors alongside her husband. In the image from the

Speculum, as Adam raises a spade, Eve sits and spins, twisting the drop spindle in one hand while guiding the fiber from a standing distaff with the other. A distaff is a long stick used to hold a portion of unspun wool or flax out of the way, while fibers are drawn out and spun onto the spindle.

8 The spindle is the part that spins—it can be as simple as a weighted whorl or the whorl can be attached to a stick to support and direct the newly spun yarn. The distaff can be attached to the body, either held under one’s arm or slipped into one’s belt, or made stationary on a stand next to the sitting spinner, as seen in the image of Eve. As she spins, she breastfeeds one child as another, older child pulls at her distaff stands with a small spindle of his own. Despite all these distractions, Eve spins.

Similarly, the Virgin Mary spins despite interruption at the Annunciation. The act of spinning is one of the many connection points between Eve and Mary: the first woman spins in support of her family, while Mary (as the New Eve) spins in anticipation of her pregnancy and growing family. In a psalter from Flanders made in the mid 1200s, the Virgin spins using a drop spindle and distaff (under her arm) as she gestures towards the Angel Gabriel (

Figure 2).

9 Her spinning at the Annunciation is rooted in an apocryphal text, the Protoevangelium of St. James. According to the text, the priests of the temple called the “undefiled virgins of the House of David” to spin the wool for the temple veil.

10 After receiving a preliminary and shocking visit from the angel Gabriel while getting water at the well, Mary returned home to spin her sacred wool: “and she went away, trembling, to her house, and put down the pitcher; and taking the purple, she sat down on her seat, and drew it out. And, behold, an angel of the Lord stood before her”

11 (

https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0847.htm, accessed on 18 June 2025). After Gabriel disappeared, Mary “made the purple and the scarlet, and took them to the priest”

12 (

https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0847.htm, accessed on 18 June 2025).

The Virgin Mary interrupted by Gabriel at her wool work appears in art as early as the late 4th century but falls significantly out of fashion by the Carolingian period, when Mary’s handwork is trumped by her spiritual, rather academic work of reading (

Cartlidge and Elliot 2001, pp. 79–80). From the 9th century onwards, artists usually picture Mary at the Annunciation reading from an open book rather than spinning (

Cartlidge and Elliot 2001, pp. 79–82). That Mary’s reading replaces her spinning reflects growing literacy patterns for women in medieval Europe. In her seminal essay “Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture”, Susan Groag Bell proved the importance of women readers as teachers and transmitters of knowledge and cultural traditions to their children (

Bell 1982, pp. 742–68). The Virgin as reader was part of this tradition.

The Annunciation from this psalter, now at the Getty Museum, recalls the earlier iconographic precedent of a spinning Virgin. When we consider Mary’s spinning, her work is compact, and she appears to keep at the task as she receives both Gabriel and the dove of the holy spirit. This scene is boiled down to the visual essentials; the space is ambiguous and abstract. Mary greets Gabriel from an interior space, under a trefoil arch, as she sits on a stool with a plump, comfortable-looking cushion. A tall lily plant is between the two figures, who stand against a gold background. Mary’s spinning indicates that she is at home; indeed, her work is clearly on display. The distaff Mary holds under her arm is not essential to spin but is helpful, especially if the spinner is a multitasker, as Mary and Eve are. The simple device gives spinners a bit more control, as it keeps the fibers “in order”, enabling spinners to pick up and put down their work. The pose of spinning on a drop spindle produces an open body position that can accentuate the frame of the image plane.

Eve’s post-Expulsion work is a necessity for her family, whereas the Virgin Mary’s spinning at the Annunciation is an allusion to her domesticity. For both, the following lines from Proverbs about the nature of a valiant woman ring true: “She hath put out her hand to strong things, and her fingers have taken hold of the spindle.”

13 Additionally, in both visual examples, the materiality of Eve and Mary’s work is clearly on display. The spindles are loaded with spun fiber, and each distaff is perfectly “dressed”. The accuracy of these tools would have made these biblical figures more accessible to contemporary viewers and readers, in the same way that medieval readers looked to the Virgin reading as a role model.

As visible in images of Eve and Mary, the combination of tension and twist makes the physical and material process of spinning work properly and productively. If one can control those elements, one can spin and make a usable yarn.

14 Spinning is inherently gendered labor because of its safe, portable, and distractable nature. Judith Brown examines these necessities of women’s work in her seminal 1970 article on the “Division of Labor by Sex.” She writes, “I would like to suggest that the degree to which women contribute to the substance of a particular society can be predicted with considerable accuracy from a knowledge of the major subsistence activity. It is determined by the compatibility of this pursuit with the demands of childcare” (

Brown 1970, p. 1075) The work of spinning, especially on a drop spindle, fits this description perfectly. Brown explains further,

Such activities have the following characteristics: they do not require rapt concentration and are relatively dull and repetitive; they are easily interruptible and easily resumed once interrupted; they do not place the child in potential danger; and they do not require the participant to range very far from home.

This core of women’s work is foundational for both the individual family and the larger culture of a society. Before the Industrial Revolution, women would have been constantly with their spindles, ready to spin at any moment (

Gies and Gies 1994, pp. 51–52). Their spinning, making yarn to be woven, was important for both their family’s well-being as well as the larger enterprises of weaving.

Artists were picturing spinners such as Eve and Mary with drop spindles at the same time as the new technology of the spinning wheel was on the horizon. After its development in the Near East or India, spinning wheels became prevalent in Europe by the late thirteenth century (

Gies and Gies 1994, p. 175). Wheels often had attached or free-standing distaffs but did not have foot treadles before the sixteenth century. Medieval wheels are in the category we now call Great or Walking Wheels—the spindle is placed horizontally adjacent to a larger wheel that is slowly powered by hand as the spinner walks to and from the spindle while the fiber twists and is taken on to the spindle. The later addition of the foot treadle allowed for speed and the freedom to use both hands at once. The foot treadle made it possible for one to spin a finer yarn faster, with the additional benefit that one could work sitting down.

The

Luttrell Psalter, which was made in Lincolnshire between 1320 and 1340, offers a rare case where both the spindle and the spinning wheel are included in the same manuscript. This richly illuminated book of psalms was made for wealthy landowner Sir Geoffrey Luttrell, who saw himself and his world pictured on the pages.

15 In addition to portraits of Geoffrey and his family, the imagery in the psalter clearly shows workers on his estate engaged in all sorts of tasks, from farming to spinning. There are four figures engaged with spinning tools in the psalter: three figures use spindles, and one uses a wheel.

16 Folio 60 recto is typical of the

Luttrell Psalter in the complexity and pervasiveness of the imagery (

Figure 3). Outside of the inhabited line fillers and foliation, this folio contains three hybrid creatures, a man about to strike a bird with a fish’s tail, and a seated bishop. Amid this visual mayhem, one finds the first spinner in the manuscript. Problematically, she is not spinning at all. Wearing a long, rose-colored dress, she holds a loaded distaff, with full spindle attached, above her head. A man wearing red shoes, and holding a bird, stands (one-footed) on the distaff handle. The woman seems oblivious to this figure as she pushes the head of a man who kneels at her feet. He raises his hands as if to beg her not to beat him with the elevated distaff.

This woman is the instigator in an early image of what later becomes the Battle of the Sexes, where an unruly woman dominates a cowering man.

17 Women using the distaff as a weapon were common in medieval art, from manuscripts to misericords. This example from the

Luttrell Psalter is representative of the iconography—as women misuse their spinning tools, the world turns upside down. The text on this folio relates to Psalm 21, which deals with injustice and judgment, and does not seem to inform the imagery at all. This folio shows the world topsy turvy, the steadiness of the bishop along the

bas de page countered by the fantastical beasts surrounding him to the jester-like character teetering on the woman’s distaff. When the woman swings at the kneeling man, the whole system comes tumbling down. Part of a constellation of imagery depending on gender role reversal, such scenes remain pervasive through the premodern periods.

The next two spinners in the

Luttrell Psalter also verge on the edge of Geoffrey’s genteel world and equally do not use their spinning tools productively. The spinner along the

bas de page of folio 30 verso counterbalances St. Catherine and her wheel on the upper corner of the folio (

Figure 4). This spinner is male and monstrous; his tunic gathers to reveal blue legs with claw-like feet. His spindle is tucked into his belt as he ponders the distaff and holds the spindle incorrectly with absolutely no tension. His bad spinning would have been obvious to contemporary audiences. How viewers understood and interpreted this figure would have been shaped by his bad spinning. For those in the Middle Ages, he is “wrong” in every way, from gender to humanness to the labor he does incorrectly. The final spindle spinner in the psalter, on folio 166 verso, is a worker pictured on the

bas de page (

Figure 5). She is taking a break from her spinning to feed some chicks. The thirteen little chicks are supervised by a giant hen. This working woman also tucks her distaff into her belt and supports it under her arm. The spindle is out of the way while she tips her dish of feed out for the chicks. As the grain falls from her dish, the viewer’s eyes are drawn to her bare feet, which accentuate her role as one of many workers on the Luttrell estate. Her spinning work is interruptible, one of the many tasks she must complete in a day. All three of the spindle users in the

Luttrell Psalter are not actually using their implements well (to their intended function) or at all.

In the fourth and final image from the

Luttrell Psalter, a lady in a long purple gown spins at a bright green wheel along the

base de page of folio 193 recto (

Figure 6). She is by far the most productive spinner, and she has a new wheel, implying a patron who favors the new technology and materiality of such a novel machine. Her gown is elegant, its form-fitting nature accentuated by a jeweled purse hanging low, perhaps heavy with coin, from a belt on her hips. She draws the fiber out as she turns the wheel while seated behind her is another lady at work carding the fiber.

18 Between the two figures is a round basket with freshly carded rolls of wool that are ready to spin. This is quite an accurate portrait of a great wheel or walking wheel. Here we see all the working parts clearly on display, from the supported spindle to the drive band to the wheel supports under the bench. Though the perspective is a bit off, the repeated pattern of the drive band, a rope that connects the large wheel to the spindle, gives a sense of implied movement as the spinner’s figure is about to turn the wheel. Her spindle is full, and we get the sense that she is just about to reach for more fiber.

Recalling the other spinners in the same manuscript, only our wheel spinner seems to be productively spinning. The elegant line, literally connected by the fiber she spins, creates a picture of a spinner in harmony with her technology. In the Luttrell Psalter the status divide between those who spin on spindles as opposed to wheels becomes clear: the well-dressed lady with her heavy purse uses the wheel while monsters, poor women, and those who misbehave use/misuse the spindle and distaff. However, even among these figures, the spinner at her green wheel in the Luttrell Psalter yet remains unusual. Spinning wheels are not common in medieval art, yet the spindle and distaff both remain prevalent in the visual record.

There are a variety of reasons that the older technology remained useful. The yarn produced on early wheels, without foot pedals or treadles, was often not consistent. For women undertaking piecemeal spinning work, there was no room for error or experimentation, and therefore, the wheel was not the primary choice for domestic spinners.

19 These rough results led to some very early prejudices against the wheel. Statutes from English drapers’ guilds in the 1280 outright ban the use of the wheel for its inconsistent yarn, which would not have been useable for weaving warps (

Gies and Gies 1994, p. 176). The

Livre des mestiers (Book of Crafts) of Bruges from 1340 is more specific: “The spinner … much values her thread which was spun on the distaff, but the thread which is spun in the wheel has too many lumps and she … earns more to spin warp at the distaff than to spin weft with the wheel” (ibid.). Domestic spinners needing to supply foundational warp yarn to weavers simply could not have afforded an inferior product. Over time, attitudes towards the wheel became more positive. This novelty status is seen in the public records when a woman living in Bishopthorpe, south of York, refers to herself as “Isabella Whelespynner” in 1379 (

Goldberg 1992, p. 145).

Recalling the connection between a woman’s virtue and her industry from Proverbs, one can also imagine the converse being present. Her spinning work could afford the medieval woman a sense of agency: her tools, her spindle and distaff, were cheap, portable, and her own. According to Michael Camille, the spindle was “an important economic asset”, one that could even be perceived as a threat, as discussed above where an unruly woman wields her distaff as a weapon (

Camille 1998, pp. 299–301). The iconography of a woman beating a man with her spinning gear persevered in art: the Battle of the Sexes is one of many tropes that depend on a woman striking a man with a distaff or spindle.

20 Women who misused their spinning equipment were seen as a threat since they opposed established gender norm as well as offering a measure of their own economic autonomy. According to Susan Smith, these antispinners are “one among many manifestations of the medieval preoccupation with women who seize the upper hand in their relations with men” (

Smith 1995, p. 2).

These contexts are clear in an image of the Thracian women attacking Orpheus from an illustrated copy of John Lydgate’s

Fall of Princes, which was probably made in England, Bury St. Edmunds, around 1450 (

Figure 7).

21 Orpheus lays on the ground with fists up to fight, but he is no match for two distaff-wielding women, their implements raised high in the air. Their loaded spindles are still attached and fly high as if gaining momentum to hit their victim, who does not stand a chance. The scene pictures an unlikely scenario because using a loaded distaff for anything other than spinning would have been incredibly wasteful. The artist’s depiction the barbaric nature of the Thracian women is communicated through their disregard of the proper usage of the spindle and distaff. Weaponizing women’s work was a way that artists could demean its value, when in fact the preindustrial economy depended on it. For example, the humble hand spinner working piecemeal was essential to the booming cloth industry of late medieval Europe.

3. Sardanapalus as Spinner by Choice

Sardanapalus and Hercules are unique in medieval and premodern imagery as they spin with a drop spindle and distaff as a consistent part of their iconography. As discussed above, the spindle and distaff would have been unmistakable gender signifiers to medieval audiences. However, in looking at manuscript and print examples, these meanings surrounding masculinity and the material nature of spinning become complicated, as both Sardanapalus and Hercules spin well and productively.

Sardanapalus is a fictional king whose does not appear on Assyrian king lists.

22 Yet he remained a cautionary tale, especially in late medieval manuals of courtly behavior. These narrative accounts of the king describe his opulent lifestyle and taste for all manner of excess. In addition, he supposedly dressed as a woman and enjoyed spinning. For example, in an illuminated copy of John Lydgate’s poem “Fall of Princes” from 1450 Bury St. Edmunds, Sardanapalus sits and spins in a large throne surrounded by trees (

Figure 8).

23 Lydgate’s text is a long list of historic kings that served as an advice manual for rulers, offering guidelines and examples of good moral behavior. It is filled with scenes illustrating antimodels for behavior. Sardanapalus wears a long, coat-like garment that is belted at the waist; similarly as in medieval images of women spinning, this belt supports his tall distaff, which is loaded with a beehive arrangement of fiber. He pulls the fiber to be spun on the spindle he spins with his other hand. He spins confidently, with strong tension, as he looks to the viewer and addresses a woman in a long dress wearing a white wimple.

24 The woman he gestures toward, raises a hand to the line he has spun, as if checking its quality. This would be an accurate image of spinning to highlight the older technology of spindle and distaff.

Looking at this image, the king radiates power and stability as he spins in his large chair. Lydgate’s poem provides a different message. He describes Sardanapalus as a “decadent” and “feminine” ruler, he writes,

- To vicious lust his liff he dede enclyne;

- Mong Assiriens, whan he his regne gan,

- Off fals vsage he was so femynyne,

- That among women vppon the rokke he span,

- In ther habite disguisid from a man.25

Text and image are related only so far as the king spins and keeps company with women, but Lydgate’s moralizing judgement is not present in the images. Medieval textual narratives about Sardanapalus rely on earlier works such as that by Diodorus, who writes that the king “outdid all his predecessors in luxury and sluggishness. For not to mention the fact that he was not seen by any man residing outside the palace, he lived the life of a woman, and spending his days in the company of his concubines and spinning purple garments and working the softest of wool” (

Diodorus Siculus 1935, 2.23). One senses a contradiction in text and image developing: Sardanapalus is a figure of luxury, excess, and perceived depravity, and yet he is productively working. That this work (signifying virtue in women) served to emasculate him points out the loaded contradictions in such imagery. In a sense, artists pictured him consistently doing the wrong thing in the right way.

In another manuscript from the British Library, that forms a Parisian compendium of history from 1473–1480, Sardanapalus sits in a larger company of women, all of whom spin (

Figure 9).

26 Indeed, all the women hold distaffs and spindles in the same position, giving the impression that there is a court style for spinning. It is not just Sardanapalus’s spinning style that matches his female colleagues: he wears a jeweled crown and a long dress with ermine along the hem as he sits against a brocaded cloth of honor. The cut of the bodice, the taper of the sleeves, and even the fall of the skirt are the same for all the spinners. The only marks of difference or authority are Sardanapalus’s cloth of honor, his beard, and his name inscribed above his crown. Sardanapalus is unmistakably associated with women through the acts of spinning and dress.

Pioneering gender scholar Vern Bullough opens his study of crossdressing with an examination of Sardanapalus: “The message of the story quite clearly is a mixed one: cross dressing is a sign of feminine weakness and justified a revolt, but beneath all the finery there was strong male potential, since Sardanapalus mounted a strong counterattack” (

Bullough and Bullough 1993, p. 24). He further writes about the concept of “status loss” in the Middle Ages when men assumed women’s roles or occupations such as nursing or spinning (

Bullough and Bullough 1993, p. 68). While these are hard concepts for modern audiences to imagine, they were part of a complex code of gender norms and expectations in the medieval and premodern periods.

4. Hercules as Spinner by Punishment

In addition to Sardanapalus, Hercules is another male figure from antiquity who is depicted as a spinner in imagery across the centuries. When one compares Sardanapalus with Hercules, however, a key difference emerges: for the mythological king, spinning was a choice, whereas for the mythological hero, it was a punishment.

27 As a penalty for the murder of Iphitus, Hercules was sentenced to serve the Lydian Queen Omphale for a year; the textual sources pertaining to Hercules’ servitude to Omphale do not mention spinning specifically, often instead focusing on the assumed sexual relationship between the pair.

28 Unlike the texts, early imagery is specific in associated Hercules with the task of spinning. For example, a clay pendant made in Luxeuil, from about 75–150 CE, clearly communicates elements of the narrative (

Figure 10). A muscular and bearded Hercules sits while pulling fiber from a loaded distaff; a spindle spins in front of him. He is covered in a drapery over his lap, which was presumably woven from his spun fiber. Omphale stands opposite and is nude, wearing only what looks like his lion skin over her shoulders. The body dynamics are on full display, her nudity and his strong physique. Fascinatingly, they trade gender roles here; spinning is how Hercules is feminized and tamed. His concentration on his punishment subdues him. One gets the sense that if Hercules would stand from his seat, he would be a giant. Considering his girth in relation to the intricacy of his spinning work creates visual tension in this and later images, adding to the implications of his gendered humiliation.

Through the Middle Ages, images of Hercules spinning are more likely to be in conjunction with Iole instead of Omphale. Iole was the daughter of King Eurytus of Aetolia, Hercules wanted to marry her, but the king refused; Hercules responds to this refusal by killing Eurytus and abducting Iole. Ultimately the incident leads to Hercules’ death, as wife Deianira was so jealous of Iole that she plotted to kill Hercules with the shirt of Nessus, which was imbued with poison (

Diodorus Siculus 1935, 4.31.1 & 2). Both Iole and Deianira are included on Giovanni Boccaccio’s

De Mulieribus Claris, and two manuscript copies of this text contain illuminations of Hercules spinning while Iole watches (Boccaccio describes Iole and Deianira in chapters 23 and 24 of his text (

Boccaccio 2001, pp. 91–99).

In a French copy of Boccaccio’s text from 1440, now at the British Library, Hercules wears full armor and an ermine-lined fur cloak while he sits under a tree surrounded by three women (

Figure 11).

29 Two of the women work with a distaff and spindle while the third holds a green poplar wreath. Iole wears a green dress and looks directly at Hercules as he returns her gaze. He holds a large spindle in one hand and his club in the other. Both implements reference conflicting gendered ability and power. By holding both, Hercules appears to be in transition, about to choose which to pursue. The regal seated pose of the hero recalls Sardanapalus, creating further links with another ancient figure of make power and strength whose position was inverted by spinning. This scene is a moment of pause, as he is not clearly spinning; instead, he seems to be weighing his options between the large spindle and the tall club. On the following folio, Hercules tries to escape with Iole, still in her green dress, on horseback: he has made his choice and has abandoned the spindle.

30The scene corresponds with Boccaccio’s text, which outlines how Iole was so horrified that Hercules killed her father that she sought to humiliate him as punishment. He writes, “Iole, however, was moved more by love for her slain father than for her husband and was eager for vengeance” (

Boccaccio 2001, p. 91). Iole’s punishment begins with dressing him in women’s clothing, jewels, and cosmetics. Finally, she forces Hercules to sit with her servant girls and tell stories of his labors. Boccaccio explains, “Taking the distaff, he would spin wool, and though now an adult—indeed a man of advanced years—he softened to stretch threads the very fingers he had hardened to kill serpents while still a baby” (

Boccaccio 2001, p. 93). This manuscript clearly illustrated all of the elements from the text: the aged hero surrounded by women as he is literally forced to spin a yarn. As in the “world upside down” imagery, gender roles are here subverted, and women’s work is thus demeaned.

In another illuminated copy of Boccaccio from 1403 at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France emphasizes the use of this theme in the visual arts and reinforces conventions that are familiar from earlier Hercules images, as well as depictions of Sardanapalus. In this image, Hercules sits on rocky ground and wears a loose-fitting garment of skins as he spins (

Figure 12).

31 His bare legs are obvious as he holds the distaff between his knees and draws the fiber onto his spindle. His clothing, pose, and unkept hair and beard all point to an unwilling servitude. Two women watch and gesture to each other in commentary. The women are both dressed in richly colored and detailed clothing; jewels adorn their hair or belt. Here, beyond just tensions regarding gender roles, we also see a clear class divide between Iole and Hercules display. The class distinctions further emasculate Hercules in addition to undermining his social status. Turing the hero into the worker strips him of the perfection and distinctiveness that are inherent to his narrative.

These images of Hercules and Iole do not hint at a connection with the much earlier iconography of Omphale. Unlike some images of Omphale, Iole does not wear his lion skin; she does not engage with his spinning at all, whereas Omphale’s costume changing, from a dress to Hercules’ lion skin, and interference with his spinning are clear from the classical imagery. Iole and Omphale are two distinct characters who have been merged in the visual record. Complicating matters is Boccaccio’s interchangeable use of Iole and Omphale (

Boccaccio 2001, p. 99). In any case, that the scene of Hercules and Omphale appears with such confidence and frequency in the premodern period suggests that it draws on an earlier, independent iconographic source. Lisa Rosenthal and Susan Smith identify this source as print cycles such as the “Power of Women” or “World Upside Down.” An example is a

Coat of Arms with the World Upside Down by the Housebook Master from about 1480–1490 (

Figure 13).

32 This print is a jumble of imagery and swirling line scrolls. At the top of the complicated composition, a woman sits on a man’s back. She spins, pulling fiber from a distaff to her loaded spindle. The pair teeters as the man holds onto the top of a helmet that is balanced on an upside-down shield. The man’s trousers are torn at the knees, and his mouth is open with a howl. He holds the base of the distaff with one hand while the woman spins with a sort of oblivious confidence. Medieval precedents for such print cycles were widespread, the Battle of the Sexes from the

Luttrell Psalter is an example (

Figure 6).

In her work on Peter Paul Rubens’ painting of

Hercules and Omphale, Rosenthal writes, “Images of Hercules holding the distaff while Omphale wields his club would take their place among other traditional scene of male disempowerment before the beauty of women, such as scenes of Samson deceived by Delilah and Aristotle ridden like a horse by Phyllis.”

33 Women misusing and weaponizing spinning tools represent the opposite of the multitasking spinners such as Eve and Mary. It is likely that medieval viewers would have looked to these antispinners as wasteful and antiwoman as they humiliated and physically dominated their male counterparts. In the Middle Ages in Europe, refusing to occupy traditionally sanctioned gender roles was cause for great anxiety and fear that led to the creation and articulation of canon laws outlining appropriate gender behavior (

Brundage 1993). As we move into the premodern period, artists deployed domestic role reversal for both social commentary and, later, comedy. Susan Smith writes,

…preoccupation with Chistian marriage as an institution for the regulation of sexuality and for social control. Civil authorities became more active in legislating and enforcing both public and private morality, and the properly ordered household became a model for the properly ordered society. Powerful, disorderly women did not cease to be compelling figures in this changed environment…

Considering Omphale in this light, she becomes not only the antispinner who exploits Hercules but a threat to domestic happiness and peace.

5. Hercules Spinning as Complicated and Comedic Image

The Power of Women

topos has elements of exaggerated absurdity as well. Following in this vein, Omphale as threat and Hercules as victim, verges on the realm of the ridiculous or comedy as we move through the premodern period. An example that shows the widespread popularity of the theme is found in the work of Lucas Cranach.

34 In Cranach’s 1531 painting of

Hercules and Omphale, now in a private collection, the hero is in the center of the composition flanked by two women (

Figure 14). He wears a brown drapery, evocative of his lionskin, that covers one shoulder, exposing his chest and arm marked by a well-defined bicep. His beard and muscles are a direct contrast to the woman’s cap on his head, highlighting his submission and underscoring his emasculation. One of the women rests her hand on the cap, giving the impression that she has just placed the garment on the hero’s head. The other woman guides fiber from the distaff to Hercules’ hand; she holds the base of the distaff. Her delicate hand offers a foil to Hercules’ as she attempts to teach the skill of spinning. Hercules spins, but he is under the control of the women. The inscription alludes to this domination, the text of the inscription in the image identifying him as “a little child” and a “dominated child.”

35 Lisa Rosenthal explains further, “Moreover, the threat to masculinity remains consistent: it is the pull towards regression, towards the dreaded, desired, infantilizing female realm.” (

Rosenthal 2005, p. 166) Everything about this painting alludes to discomfort, domination, and control. Hercules is to be pitied but also ridiculed.

In a print by Aegidius Sadeler II from about 1600, Omphale and Hercules face each other; Omphale looks to the viewer as coconspirator in her plot to humiliate Hercules (

Figure 15).

36 She wears his lion skin and holds his club between her legs as she looks over her shoulder to the viewer. Hercules balances a distaff under his arms and guides the fiber across his muscled body to the spindle. His pose accentuates and draws attention to his physique. His foot stretches out to rest on the club that Omphale has taken. The size of the spindle and club allude to the emasculation of the hero. A pair of yarn clippers, in the sewing basket in the foreground, points to the club to further make the point of the hero’s domination. The pair are surrounded by ladies-in-waiting and even a cupid in a rather jumbled interior space filled with draperies, fruit, and large columns. Everything about the space and figures suggests mismatched power. Kristin Heineman writes “the fact that Heracles was enslaved to a woman turns the episode into a common scene for comedy … it is not the slave Heracles that should be mocked, it is the foreign whore queen that wields far too much power” (

Heineman 2021, pp. 258–59). Indeed, in the visual record, the hero’s massive form at the work of spinning can draw an empathetic response. Yet even in his humiliation, he spins productively.

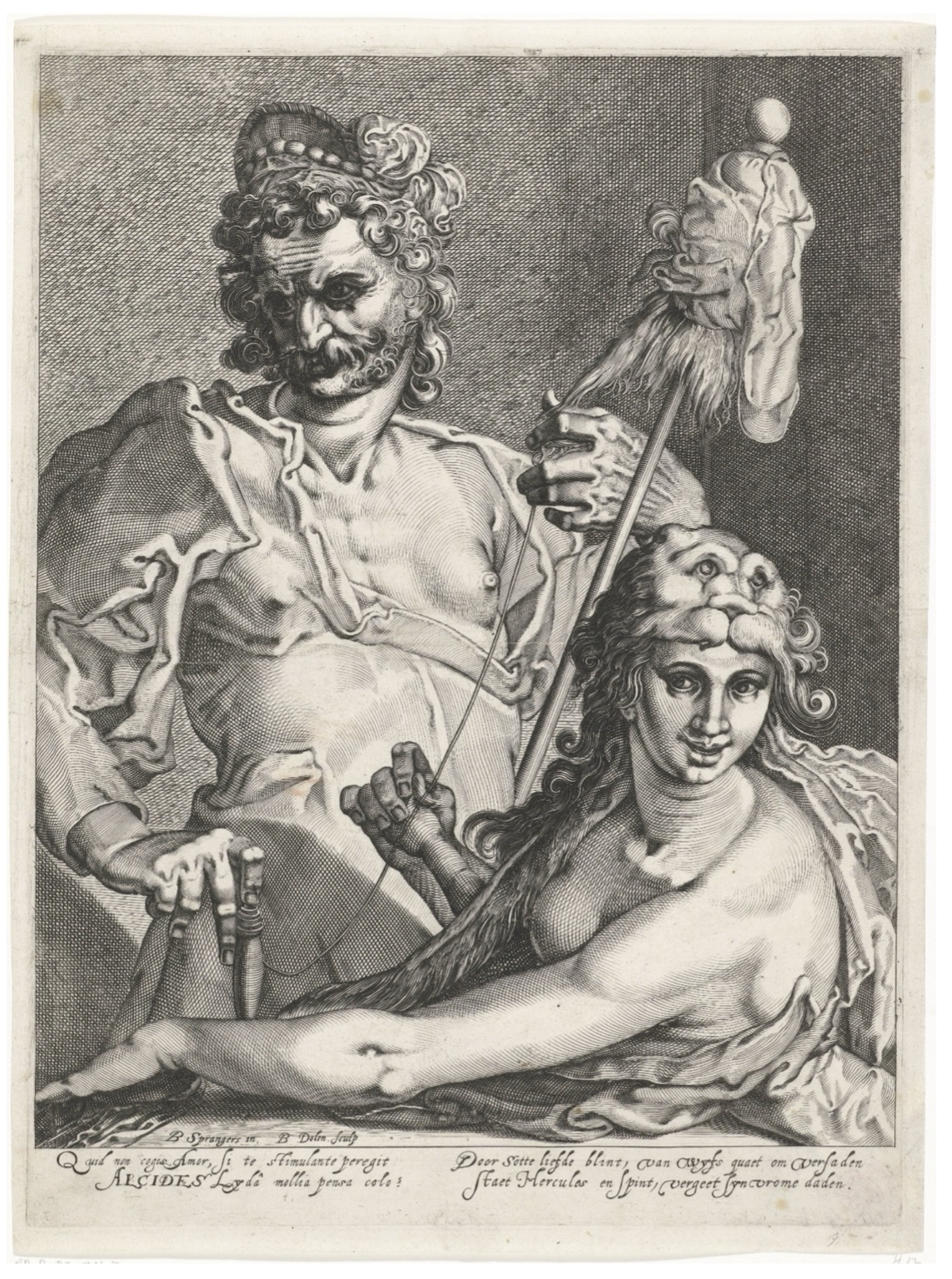

On a smaller and more immediate scale, the sexual relationship between Hercules and Omphale is on display in another contemporary print by Dutch engraver Bartholomew Willemsz Dolendo from the late 16th century (

Figure 16).

37 Here the scene is boiled down to the two key characters. Omphale looks conspiratorially to the viewer with a triumphant smile as she holds the fibers that Hercules leads from the distaff to the spindle. She wears his lion skin, and her own strong, bared arm marks the foreground of the picture plane, as if to mark the hero she has captured. Hercules spins with a pinched expression on his bearded face. His curls complement his furrowed brow in communicating his discomfort in the act. His body is covered by drapery that appears to be Omphale’s dress, evident in the hem of the sleeve of his spinning hand. His hands are the only part of his body clearly on display, and they bulge with veins and bones that suggest his physical strength. The dress is stretched and pulled over his torso, recalling Vern Bullough’s account of Sardanapalus’ masculinity under the guise of his costume. Hercules’ body seems to rebel against the punishing clothing, giving the viewer a sense of his frustration. There is a marked tension between Hercules and Omphale in this print; she flaunts her power, inviting the viewer to engage, while Hercules looks pinched, miserable, and awkward.

In both prints, Omphale’s perceived overconfidence is on full display. On the one hand, she takes the upper hand in the visual narrative, but on the other hand, she is part of a comedy. She looks to the viewer as if to boast and direct us to laugh at her captive, yet the viewer is simultaneously meant to laugh at her role reversal. She wears the lionskin with pride, displaying her body, further making audiences question her credibility and authority. Tertullian writes about Hercules and Omphale in a vitriolic text on gender norms, “No sober woman even, or heroine of any note, would have adventured her shoulders beneath the hide of such a beast … What sort of being the said Hercules was in Omphale’s silk, the description of Omphale in Hercules’ hide has inferentially depicted” (

Tertullian n.d.). Both prints were made as copies of Bartholomaus Spanger’s painting of

Hercules and Omphale. While the prints are fairly unique from the painting, a sexual tension between the pair is present; Omphale’s nude body is on display in each print, both of which are accompanied by poetic inscriptions that describe Hercules as dominated by the power of love.

38