3. Janco’s Artistic Transformation

The Bucharest Pogrom did not merely disrupt Janco’s life; it ruptured the very foundation of his artistic practice. Before January 1941, his work had balanced modernist structure with avant-garde experimentation, negotiating between Dadaist fragmentation and Constructivist precision. But in the aftermath of atrocity, such formal strategies no longer sufficed. How does an artist depict suffering when the very visual language he once employed has been rendered inadequate by the events themselves? For Janco, this was not just a theoretical dilemma but a material crisis. His previous artistic vocabulary—rooted in geometric abstraction, structural clarity, and experimental rupture—was no longer an effective means of confronting the destruction he had witnessed. If his earlier career had sought to rebuild the world through form, the pogrom had now reduced that world to ruin. Janco’s shift from modernist clarity to grotesque distortion marks a fundamental rupture in his artistic vision. His Holocaust drawings, rather than offering legible testimony, insist on fragmentation as the only viable response to atrocity—where visual instability becomes an ethical imperative.

Faced with this crisis, Janco’s response was immediate. In the days following the pogrom, he turned to drawing—not as an aesthetic exercise but as an act of survival. His compositions abandon the stability of prewar modernism; in their place emerges a visual language of raw, uncontained violence. For the first time in his career, Janco’s fragmentation is not an avant-garde device but a historical necessity. As he later wrote:

“My hatred and contempt for the beasts who inflicted such cruel blows upon my people found, […], another form of manifestation. I possessed other weapons—those of a man of letters and art. I began to write and expressed myself with the thirst for vengeance. I drew to denounce the madness, the sadism, the bestiality of an entire people who, in our century, lived in the very heart of what we call—civilized Europe.”

Janco’s words expose the urgency and desperation that fuelled his artistic response. The language of “weapons” and “vengeance” signals a shift in his understanding of art, not as an intellectual pursuit but as resistance. His reference to “civilized Europe” drips with bitter irony, underscoring the dissonance between the continent’s cultural ideals and its brutal realities.

For him, drawing was not depiction; it was counterattack: “I drew with the desperation of a hunted man, racing to quench his thirst and find refuge” (

Janco 2022, p. 11). What had once been a visual language of play for Janco was now a language of undoing—one that refuses to stabilize history, demanding instead its disintegration. After 1941, fragmentation was no longer an aesthetic strategy. It was the only way to depict disintegration.

Janco’s grotesque is not mere distortion; it is rupture. What was once a formal experiment—fractured, jagged compositions—now bears the weight of historical violence. His figures are not exaggerated; they are disfigured, stretched to the limits of endurance, their faces reduced to vacant masks that refuse expression. They do not speak; they endure. Here, fragmentation is no longer a means of formal innovation—it is the residue of destruction. His compositions suffocate. Figures press against one another, crushed within the very enclosures that define them. Cells. Ghettos. Camps. These drawings do not depict spaces of confinement; they inhabit them. Claustrophobia is not a visual effect; it is a condition. Janco’s monochrome does not denote absence; it is the visual excess of loss. Black ink, heavy and inescapable, crushes the blankness of the page. White space is not emptiness; it is erasure.

Janco’s Holocaust drawings do not belong within traditional modes of Holocaust art; they defy categorization, rejecting the visual frameworks that have come to define representations of catastrophe. Unlike conventional Holocaust imagery, which often oscillates between forensic documentation and symbolic memorialization, Janco’s work refuses both. His images do not offer closure or commemoration; they unsettle, disrupt, and resist absorption into historical narrative. But if Janco’s Holocaust drawings refuse closure, this is not an aesthetic ambiguity—it is an ethical stance. Rather than containing trauma within a stable form, his distortions refuse reconciliation, ensuring that suffering remains unresolved, unassimilated. His work demands not only that we look but that we confront the insufficiency of looking itself. This refusal sets his approach apart from other artists who have grappled with Holocaust representation.

While figures, such as Felix Nussbaum, George Grosz, David Olère, and Anselm Kiefer, also engage with absence, fragmentation, and the crisis of representation (

White 2020;

Milerowska 2024;

Biro 2003), their works ultimately impose aesthetic or narrative structures that frame suffering within allegory, critique, documentation, or historical reflection. Janco, by contrast, refuses these stabilizing frameworks—his drawings do not seek to explain, reconstruct, or mediate suffering but to insist upon its immediacy, rawness, and rupture. His distortions are not interpretative but visceral, existing at the threshold of witnessing itself.

For instance, Nussbaum’s work remains tied to a symbolic, allegorical mode of Holocaust representation, using metaphor to process catastrophe. As Magdalena

Milerowska (

2024, pp. 403–19) has shown, Nussbaum’s Triumph of Death (1944) visualizes war and genocide through fractured compositions and vanitas symbolism, creating a space where history is not depicted directly but mediated through metaphor. Janco, by contrast, rejects this mode of translation altogether; his distortions do not encode suffering into allegory but present it in its raw, unmediated form. Unlike Nussbaum’s layered symbolism, Janco’s figures resist metaphor, existing instead as ruptures in the visual field, unassimilable and irreducible.

At the same time, Janco’s grotesque distortions recall the politically charged visual strategies of George Grosz. Yet, unlike Grosz, whose interwar montages primarily satirized power from a critical distance, Janco’s distortions bear its weight—his grotesque elongations and compressions mirroring the physical and psychological deformations inflicted upon Jewish victims of the Bucharest Pogrom. As Michael

White (

2020, pp. 960–87) has argued, Grosz’s late montages engaged with political expression and personal reflection, extending beyond Dadaist provocation into a mode of historical reckoning. However, whereas Grosz weaponized distortion as an act of critique, Janco mobilizes it as a form of witnessing. Grosz’s figures are grotesque in their caricatured inhumanity, exposing the moral decay of their subjects, but Janco’s distortions emerge from within the trauma itself—his figures do not satirize power but embody its consequences.

David Olère, a survivor of Auschwitz, renders memory with forensic precision, reconstructing the camps with documentary exactitude. His work serves as postwar testimony, an attempt to make visible what was otherwise erased. Janco’s drawings, however, emerge from a different urgency—not reconstructing atrocity from memory but producing images before memory has even settled. If Olère’s works belong to the genre of post-Holocaust documentation, Janco’s grotesque distortions exist in a state of rupture—capturing an event still in progress, before historical distance, before stability, before language.

Finally, Janco’s work stands in stark contrast to Anselm Kiefer’s engagement with Holocaust memory. Although Kiefer did not witness the Holocaust directly, his postwar engagement with its memory through material decay and conceptual erasure provides a revealing counterpoint to Janco’s immediate, embodied response. This temporal and generational distance highlights the shifting visual strategies for representing trauma, and the contrast sharpens our understanding of Janco’s refusal of abstraction as a mode of distancing. While Kiefer’s multimedia works confront historical trauma through hermeneutic undecidability and reflexivity (

Biro 2003, pp. 113–46), Janco operates from a position of immediacy. This fundamental difference stems not only from their artistic methods but from their relationship to history itself. Janco was a direct witness to the events, whereas Kiefer, as a postwar artist, engages with the Holocaust from a position of historical distance, negotiating not testimony but the weight of inherited memory. However, if Janco, Nussbaum, Grosz, and Olère register violence as it unfolds, Kiefer faces a different imperative: the struggle of reckoning with a history that is both inescapable and inaccessible. Kiefer’s postwar landscapes grapple with how Germany remembers the Holocaust, embedding trauma within the materiality of his paintings, while Janco’s drawings do not navigate memory at all—they exist within the violence itself, before memory has even taken shape. This distinction is crucial because it reveals not only the ethical stakes of Holocaust representation but the limits of artistic form itself.

Rather than simply drawing parallels, this essay examines how different historical conditions of witnessing—or the impossibility of witnessing—shape artistic responses to catastrophe. The artists discussed here—Nussbaum, Grosz, Olère, and Kiefer—all grapple with the limits of representation, yet their works engage trauma through modes of allegory, critique, documentation, or historical mediation. Janco, by contrast, refuses such stabilizing frameworks altogether. His grotesque figures do not transform trauma into metaphor nor do they reconstruct the past; they emerge as raw ruptures in the fabric of history itself.

If Nussbaum translates atrocity into allegory, Grosz into political critique, Olère into forensic documentation, and Kiefer into postwar reckoning, Janco’s drawings reject translation altogether. They do not process suffering—they inhabit it. In doing so, Janco challenges not only the visual strategies of Holocaust representation but the very premise that history can be contained within representation at all. His drawings do not belong to the postwar tradition of grappling with memory, nor to the documentary impulse of testimonial art—they are eruptions of immediacy, visual ruptures produced at the threshold of catastrophe itself.

By situating Janco within this trajectory, we see that his Holocaust drawings are not merely an extension of avant-garde strategies but an intervention into their limits. Where Kiefer’s postwar landscapes interrogate how Germany remembers the Holocaust, Janco’s drawings do not navigate memory—they exist at the threshold of witnessing itself. His grotesque figures do not function as symbols; they are not mediations of history but its immediate aftermath—compressed, fragmented, and irreducible.

Yet, this rupture is not abstract; it is material, visual, and urgent. If Janco’s work resists mediation, how does it make suffering visible? What happens when artistic form is stripped of symbolic function? These questions unfold not in theory but in the works themselves, where the very act of drawing becomes a confrontation with catastrophe.

4. From Artistic Vision to Testimony: Analyzing Janco’s Holocaust Drawings

If Janco’s Holocaust drawings refuse resolution, this refusal is not an aesthetic ambiguity but an ethical imperative. They confront the limits of representation, forcing us to reconsider not only how suffering is visualized but how it resists visualization. The grotesque distortions, the claustrophobic compression, the deliberate breakdown of form—these are not stylistic choices but the conditions under which Janco’s work takes shape, a visual language forged in crisis. It is within this framework that the following analysis unfolds. The five selected drawings do not construct a cohesive narrative but exist as a network of ruptures, each articulating a distinct facet of trauma’s visual grammar. Rather than reconstructing events, they enact their instability, positioning artistic vision as an act of bearing witness rather than representation.

Janco’s Holocaust drawings mark a radical departure from his interwar aesthetic, where Constructivist precision and architectural clarity gave way to violent fragmentation and grotesque compression. His stylistic evolution is particularly evident when comparing The Angry Mob, Coșer, and Dupa Pogrom, each of which reveals a distinct approach to the instability of representation in the face of atrocity.

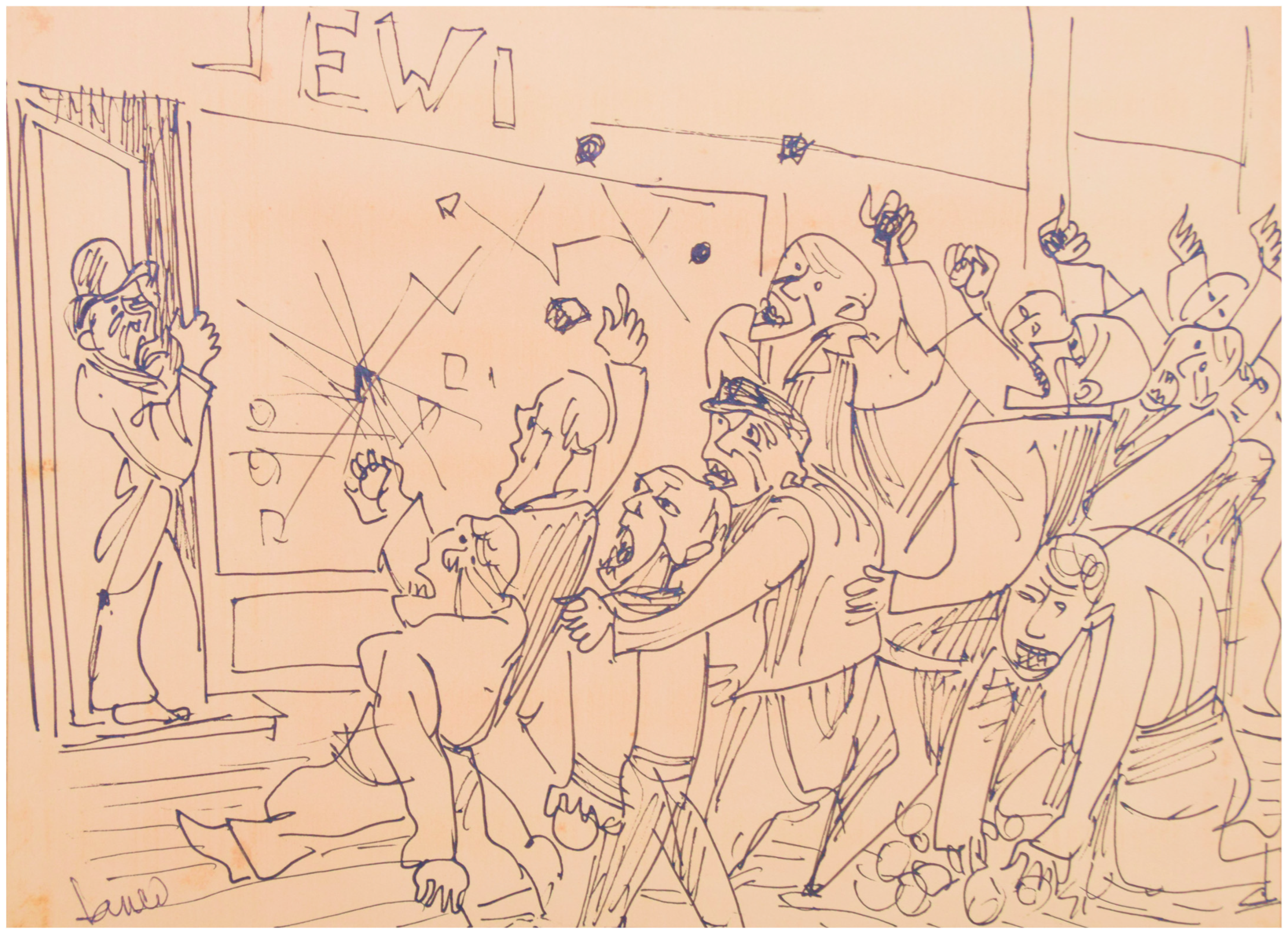

The first one, The Angry Mob (

Figure 1) transcends mere depiction, embodying the very mechanics of violence and exposing its structural underpinnings. He employs an aggressive, jagged line that fractures the surface of the composition, echoing the chaotic energy of the rioting crowd. The figures are not delineated with the crisp contours’ characteristic of his earlier work but rather dissolve into erratic strokes, as if their very form is collapsing under the weight of the violence they enact. The speed and urgency of his mark-making suggest a refusal of aesthetic polish, privileging rawness over refinement. This aggressive linework reaches an extreme in the next drawing, Coșer, where ink strokes become almost skeletal, reducing bodies to fragile, elongated remnants—a transition that underscores Janco’s evolving response to atrocity.

The aggressors are deliberately de-individualized, merging into a singular, undifferentiated mass—a faceless embodiment of collective culpability. The isolated figure at the threshold stands at the precipice of dissolution, visually reinforcing the precarity of individual identity in the face of mass violence. Even the shattered glass functions as a metaphorical rupture, highlighting the fragility of societal and architectural structures meant to offer security. Janco critiques the failure of modernist ideals: buildings designed to shelter become shattered enclosures, unable to withstand the force of ideological hatred.

This drawing functions as both a depiction of physical violence and a psychological study of terror. The exaggerated gestures—clenched fists, outstretched arms, and wide-open mouths—suggest not just brutality but the mob’s descent into an orchestrated frenzy, fueled by propaganda and sanctioned hatred. The stark black ink against the plain background strips away extraneous detail, forcing the viewer to confront the figures in their brutal unity. This minimalism mirrors the way trauma condenses memory into fragmented impressions, reinforcing the impossibility of fully reconstructing catastrophe.

In contrast to his earlier Dadaist and modernist works, already discussed for their brimming use of color and rhythmic composition, Janco’s restrained palette, dominated by black ink with stark accents of pale blue, red, and ochre, intensifies the drawing’s testimonial function. The absence of chromatic complexity does not mute the impact but sharpens it, reducing the scene to elemental violence. The repetition of snarling expressions suggests not just the dehumanization of victims but of the perpetrators themselves, stripped of individuality and reduced to instruments of destruction.

Figure 1.

Untitled (The Angry Mob), c. 1941. Ink and watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the Janco Estate. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

Figure 1.

Untitled (The Angry Mob), c. 1941. Ink and watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the Janco Estate. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

The half-erased inscription “JEWI” serves as a potent symbol of textual violence and ideological erasure. Language is not simply defaced; it is actively disintegrating, reinforcing the broader tension in Holocaust representation: how does one visualize acts designed to annihilate not only people but entire identities? This act of erasure articulates antisemitism as not merely an ideology of exclusion but of negation itself.

Janco’s gestural intensity resists historical detachment. The drawing does not frame the event as a static past occurrence—it propels it into the present, compelling the viewer into a state of complicity. Unlike conventional testimonial images that seek to preserve memory, The Angry Mob operates as an accusation. This is not a passive document of history but a direct confrontation.

Janco’s approach to distortion and fragmentation in The Angry Mob is deeply rooted in his earlier engagement with Dadaist strategies, particularly in how the movement rejected aesthetic stability and embraced dissonance. As Hans Richter describes, Dadaists had long since sought to dismantle conventional representation, using fragmentation not just as a stylistic device but as a radical challenge to meaning itself (Dada: Art and Anti-Art, 2016). However, while early Dadaists employed distortion to subvert rationality and expose the absurdity of modern life, Janco mobilizes it in response to the breakdown of reality under atrocity.

The suffocating compression of space in The Angry Mob intensifies this shift. Figures are densely packed, their interwoven forms reinforcing the inescapable terror of mob violence. Unlike Dadaist compositions, which often reveled in disorder as rebellion, Janco’s jagged linework does not merely disrupt coherence—it enacts persecution itself. The composition barely contains its own intensity, mirroring the overwhelming force of pogrom violence, where victim and space collapse together under the weight of destruction. This transformation of fragmentation—from Dadaist defiance to historical necessity—resonates with Michael White’s argument in Dada: Art and Anti-Art (

Richter 2016) that avant-garde rupture was never purely aesthetic but an intervention into the limits of representation. Janco extends this principle into the realm of catastrophe, where form itself is strained to breaking point under the pressure of historical trauma.

This strategy aligns with the broader refusal of closure seen throughout Janco’s Holocaust drawings. As discussed earlier, his rejection of allegory, critique, and direct documentation sets him apart from artists, such as Felix Nussbaum, George Grosz, David Olère, and Anselm Kiefer. However, in The Angry Mob, his handling of distortion and spatial compression offers another lens through which to examine these divergences. While Janco’s grotesque fragmentation recalls Grosz’s politically charged distortions, it operates in radical contrast to his satirical mode—not ridiculing power but registering its violent imprint. Similarly, the claustrophobic intensity of The Angry Mob shares an affinity with the suffocating enclosures in Olère and Nussbaum, but where their compositions attempt to bear witness, Janco’s enacts rupture itself. His work does not reconstruct violence as a narrative—it renders it immediate, inescapable, unresolved.

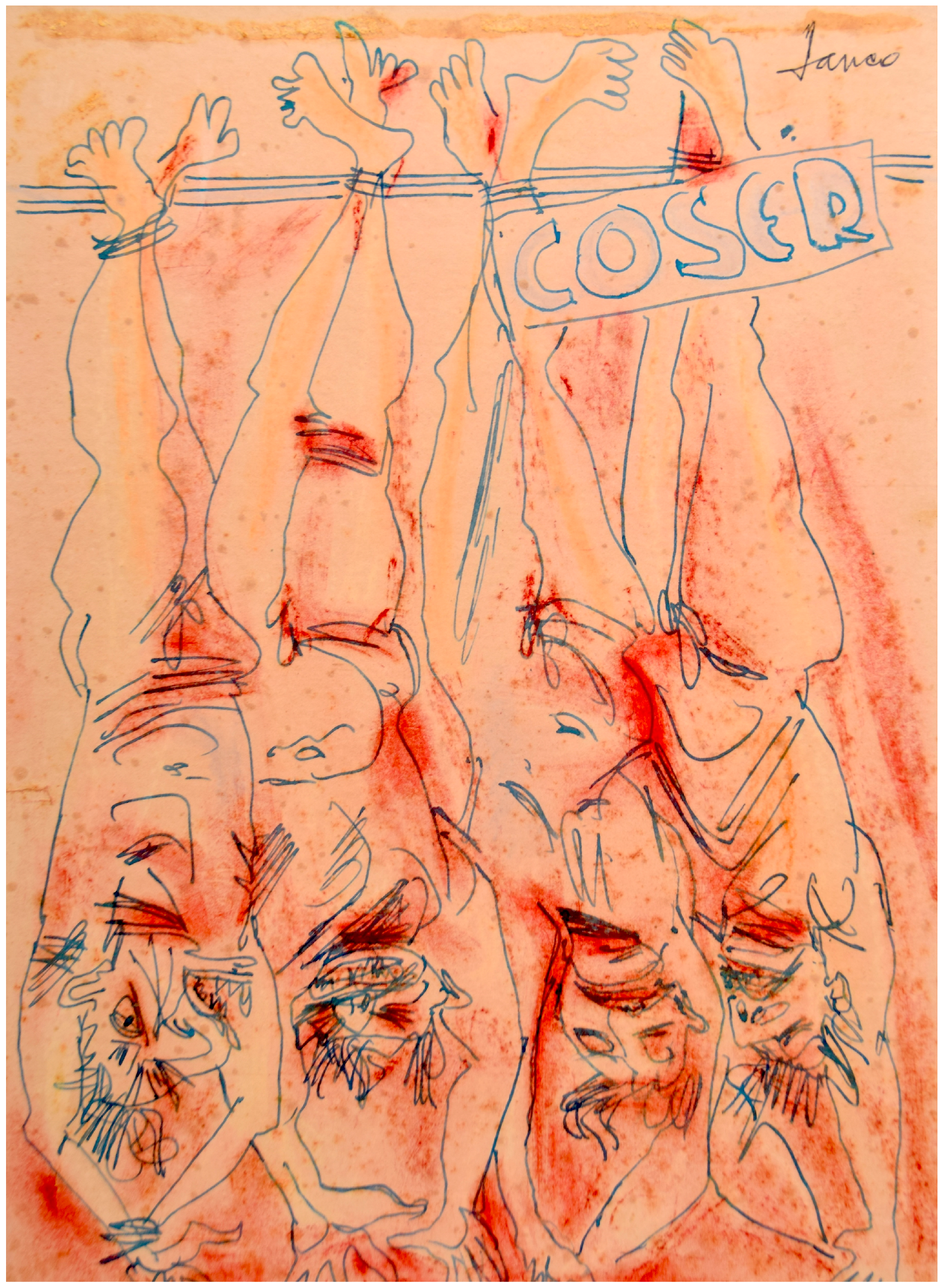

If The Angry Mob presents violence as eruption, Coșer (

Figure 2) distils it into spectacle, revealing the transformation of atrocity into a visual system of control. While The Angry Mob depicts collective brutality in motion—rage manifesting through movement and distortion—Coșer immobilizes its victims, freezing them in a state of perpetual suffering. In shifting from the chaotic energy of mob violence to the rigid spectacle of execution, Janco exposes not only the immediacy of atrocity but its lingering afterlife as a public display of power and degradation.

Unlike the controlled geometric abstractions of his interwar designs, Janco’s Holocaust drawings abandon compositional stability, using distortion to communicate physical and psychological torment. The figures in Coșer do not simply hang; they collapse under their own weight, their limbs bending under the pull of gravity and death. This grotesque elongation establishes a lineage with the twisted, deformed bodies of George Grosz’s war drawings, yet the function of distortion diverges crucially. While Grosz weaponized deformation to satirize social decay, Janco harnesses it as a mode of witnessing—his grotesques are not caricatures but visual testimonies of mutilation. Unlike Grosz’s often monochromatic ink drawings, Janco smears his forms with streaks of rust-red pigment that do not merely suggest blood—they evoke the tearing of flesh, the open wound, the violence of bodies flayed alive. The color does not decorate—it scars. It saturates the paper like dried blood ground into skin, transforming the surface itself into an extension of mutilation.

If The Angry Mob captures the explosive ignition of antisemitic violence, Coșer presents its final, motionless state, stripping it to its starkest, most inescapable terms. Unlike the kinetic energy that fractures The Angry Mob, Coșer is static, unrelenting. The victims do not fight back, nor do they plead; they simply hang, drained of resistance. Rendered in thin, brittle lines, their bodies seem almost transparent, yet no less brutalized. Suspended in a state of prolonged suffering, their contorted bodies exist not in the moment of execution but in its echo—violence transformed into permanence.

Figure 2.

Coșer, c. 1941. Ink on paper. Courtesy of the Janco Estate. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

Figure 2.

Coșer, c. 1941. Ink on paper. Courtesy of the Janco Estate. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

Violence here is not an act but a display. The verticality of the composition reinforces subjugation, stretching the bodies along a rigid, inescapable axis. The pictorial field is consumed by the suspended corpses, with no reprieve, no horizon line—no spatial exit. The downward pull of their weight is emphasized by the cold, mechanical rigidity of the metal bar from which they hang—a brutal contrast to the frenetic, almost involuntary gestures of their limbs. The absence of a defined background intensifies their isolation. Unlike the chaotic urban environment in The Angry Mob, Coșer refuses a sense of place. There are no walls, no streets, no architectural elements to situate the scene within history. This is not a moment recorded; it is a void created. By erasing spatial markers and reducing the body to a grotesque suspension, Janco denies viewers the possibility of historical distance. Instead, his work forces an encounter with atrocity that is unrelenting, refusing to frame suffering within familiar narratives of martyrdom or redemptive commemoration.

Returning to our earlier discussion of Olère’s documentary precision, Janco’s Coșer intensifies this contrast. Olère’s documentation of Auschwitz functions as a postwar act of witnessing—an attempt to make the unseen visible, to counter erasure through detailed reconstruction. Janco, by contrast, offers no such visual retrieval. If Olère’s meticulous renderings expose what history seeks to forget, Coșer enacts the very conditions of disappearance. There is no reconstruction, no spatial markers grounding the scene within a legible context. The figures are suspended in an abyss, their mutilated bodies not merely depicted but dissolved into a space that denies their presence even as it makes them horrifyingly visible. This refusal of historical retrieval aligns Janco not with the testimonial impulse of postwar Holocaust art but with the impossibility of witnessing itself. His abstraction does not serve to obscure suffering but to expose its irrepresentability. Unlike Olère, who reconstructs the machinery of genocide with documentary clarity, Janco’s grotesque figures refuse coherence, refusing to transform the mutilated body into a site of knowledge. His work does not inform—it unsettles, rupturing the viewer’s ability to process atrocity within the comforting frameworks of recognition and understanding. This is where Coșer resists not only realism but even the notion of art as testimony. Janco does not attempt to restore what was lost; he forces us to confront the loss as an irreducible condition, an absence that cannot be filled, only endured.

The inversion of the bodies is crucial to Janco’s composition. Not only does it evoke ritual slaughter, but it also invokes a broader history of public executions, where the display of the dead serves as both punishment and spectacle. This inversion serves a double function: it intensifies the grotesque horror of the scene while also neutralizing individual identity. These are not martyrs, not heroes; they are bodies reduced to their most basic, disposable state. The red smears that run across their faces and torsos read less as traces of blood than as the scars of obliteration—effacing identity, muting expression, and turning flesh into something closer to ruin than to remembrance. This is where Janco’s approach fundamentally diverges from the memorialized dignity often afforded to Holocaust victims in postwar public monuments. There is no solemnity here—only a grotesque mockery of existence.

As previously established, Janco’s grotesque distortions do not function as satire, as they do in the work of Grosz, nor do they operate as allegorical signifiers, as in Nussbaum’s paintings. If The Angry Mob captured violence in motion, Coșer presents its aftermath, its figures no longer engaged in action but suspended in a state of irreversible suffering. Yet here, Janco’s treatment of the face marks a crucial departure. While Grosz deploys exaggerated facial expressions to expose the moral and ideological decay of their subjects, Janco’s figures do not function as critiques of power—they bear its imprint. They are not character types engaged in social commentary; they are human remains.

Facial expression, often a site of psychological depth in portraiture, becomes in Coșer an index of dehumanization. In The Angry Mob, the aggressors’ snarling faces convey movement, energy, and intent. Here, by contrast, the victims’ features are frozen in grotesque grimaces—mouths twisted open yet emptied of voice, eyes wide yet devoid of agency. Their expressions do not communicate suffering so much as they confirm its completion.

The presence of the text Coșer heightens the brutality of the drawing. Unlike the fragmented inscription “JEWI” in The Angry Mob, where language itself is subjected to violence, here, the word is intact—bold, stable, unyielding. Rather than disintegrating, it is imposed with bureaucratic finality, transforming human bodies into textual objects. The stark, industrial lettering stands in jarring contrast to the agony below, reinforcing the mechanized logic of extermination. Coșer (Kosher), a term associated with ritual purity, is here repurposed into a grotesque inversion, reducing the victims to mere livestock in a system of industrial slaughter. The boundary between human and product, murder and protocol, collapses.

The use of ink and the deliberate sparseness of shading create an aesthetic of stark immediacy. But it is the red—the dusty, streaked red—that dominates the image’s emotional register. Applied with an uneven, almost casual violence, it seeps across the paper like blood ground into skin, marking the very surface of the image as a wound. Janco does not build depth or illusion; there is no chiaroscuro, no attempt at pictorial consolation. They exist in absolute isolation, within the irreducible space of spectacle. This is what makes Coșer so terrifying: it is not simply an image of execution but of execution staged for display, a scene composed explicitly for the viewer’s gaze. Unlike The Angry Mob, where violence erupts dynamically, Coșer captures violence at its most horrifying stage: as a completed, irreversible act, lingering beyond the moment of death.

Janco’s compositions also shift dramatically in their spatial treatment, moving from chaotic dispersal to suffocating compression. In The Angry Mob, figures clash and overlap, their forms pushing against the edges of the frame. The lack of negative space amplifies the overwhelming nature of mob violence, reinforcing how the victims are engulfed within an uncontainable force. In contrast, Coșer subjects the figures to a rigid, almost mechanical order, reinforcing their transformation into objects of spectacle. The stark verticality of the composition, with the victims strung up in a cold, serial formation, mimics the industrial logic of execution. Unlike the uncontrolled frenzy of The Angry Mob, here, violence is no longer an event—it is a condition, fixed, enduring, inescapable.

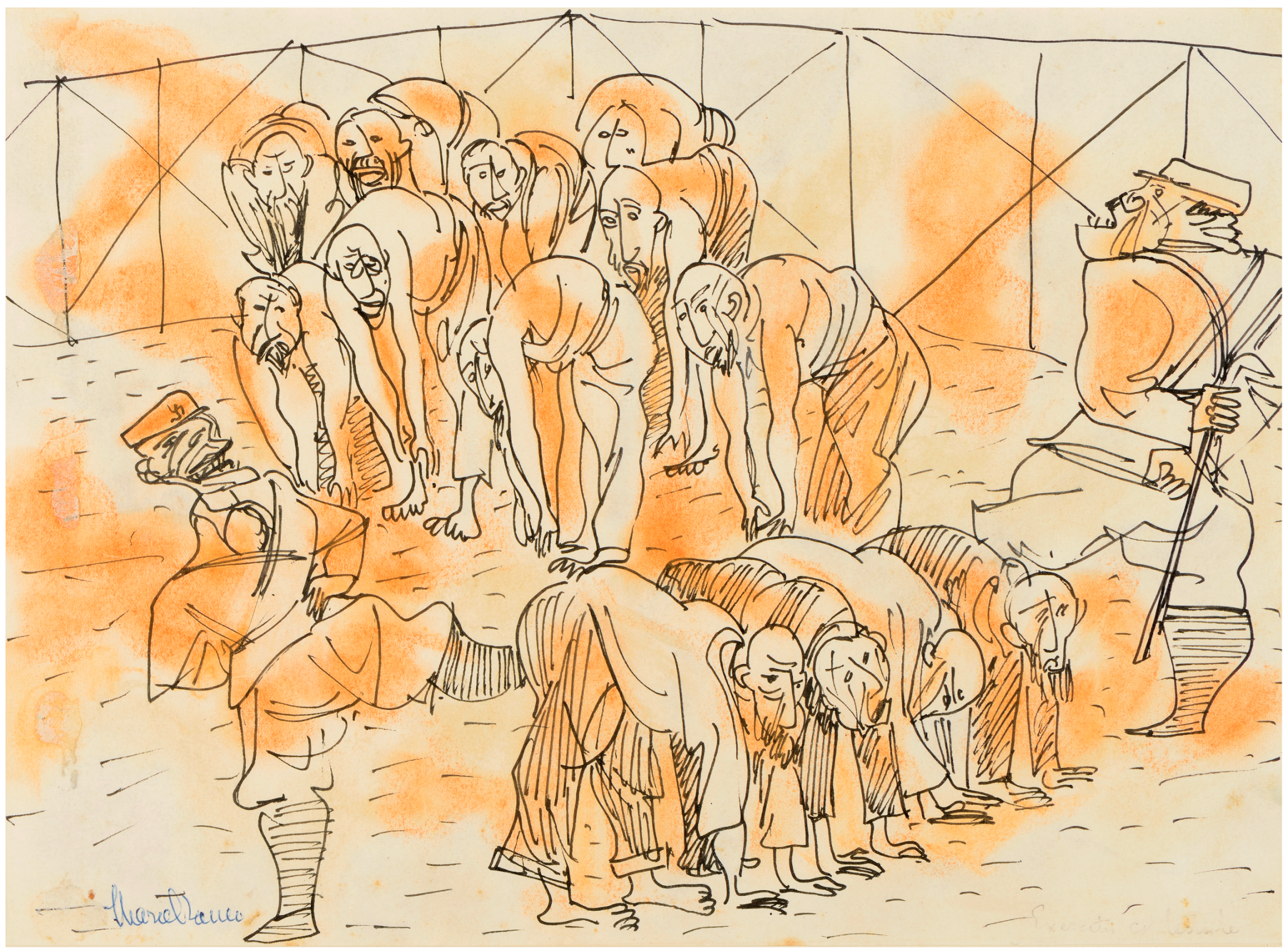

If Coșer immobilizes violence in its most horrifying stasis, transforming bodies into dehumanized objects of spectacle, the next drawing, Dupa Pogrom (

Figure 3), reintroduces movement—but only as collapse, exhaustion, and forced continuation. Where execution in Coșer rendered victims permanently suspended in a state of display, Dupa Pogrom shifts focus to the weight of survival itself as a form of violence. Janco moves from the spectacle of death to the physical and psychological burden of endurance, tracing how atrocity lingers within bodies long after the event itself. Unlike the grotesque finality of Coșer, where bodies are trapped in a rigid, imposed stillness, the figures of Dupa Pogrom appear unmoored, bent under an invisible yet crushing force.

Where Coșer arrests violence in its most horrifying stasis—bodies reduced to lifeless display—Dupa Pogrom reintroduces movement but not as resistance. Instead, Janco presents figures trapped in a cycle of collapse, their gestures fragmented, their forms no longer stable. As seen in the progression from The Angry Mob to Coșer, Janco shifts from the explosive moment of violence to its transformation into spectacle—now, in Dupa Pogrom, he explores its lingering, unresolved aftermath. If earlier works in this series depicted violence in its immediate eruption or its grotesque exhibition, Dupa Pogrom shifts toward the prolonged burden of survival—a survival that is neither heroic nor liberating but a state of continuous deterioration.

Unlike the angular, frenetic energy of The Angry Mob, the figures in Dupa Pogrom are not in motion but frozen in exhaustion. Janco’s linework, which in earlier drawings was jagged and chaotic, here becomes frayed, hesitant, reflecting the transition from immediate brutality to the numbing weight of its aftermath. If Coșer forced the viewer to confront the fixed stasis of death, Dupa Pogrom shifts the perspective to the oppressive gravity of survival. Yet, unlike the grotesque finality of his other Holocaust drawings, Dupa Pogrom introduces something more complex: the liminal tension between despair and endurance, between suffering and the necessity of persistence.

Figure 3.

Dupa Pogrom, c. 1941. Ink and watercolor on paper. Image reproduced from Kav ha-Kets (On the Edge), Tel Aviv: Am Oved Publishers, 1981. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

Figure 3.

Dupa Pogrom, c. 1941. Ink and watercolor on paper. Image reproduced from Kav ha-Kets (On the Edge), Tel Aviv: Am Oved Publishers, 1981. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

The composition of Dupa Pogrom reflects this uneasy equilibrium. Figures are scattered throughout the foreground, their postures bent under the cumulative burden of trauma, yet still engaged in action—lifting, searching, rebuilding. Unlike Coșer, where bodies hang in inhuman suspension, here they remain anchored, tethered to the earth, even as their gestures and expressions betray exhaustion and grief. The spatial instability in this work continues the theme of architectural dissolution seen in previous drawings, yet here, the fragmentation is more subdued. The compressed foreground traps the figure in a tangled network of limbs, while the dissolving background denies them a stable environment.

As previously discussed, this dissolution of space recalls Felix Nussbaum’s Triumph of Death (1944), where architecture ceases to function as shelter and instead becomes a monument to its own disintegration. However, where Nussbaum’s symbolic treatment of ruin frames catastrophe through allegory, Janco resists such interpretation, his broken structures are not metaphors but direct articulations of rupture. The survivors do not inhabit a coherent environment but a psychic landscape of ruin, reinforcing the instability of memory itself.

The presence of color in Dupa Pogrom, a notable divergence from Janco’s stark black-and-white compositions, further complicates its emotional register. Muted, spectral tones of rusty oranges and faint blues seep into the scene, as if memory itself is bleeding into the landscape, rendering the past inescapable. Unlike the rigid, bureaucratic lettering in Coșer, color here is used fluidly, creating an almost unstable, dissolving atmosphere. Here, color does not serve as mere embellishment but as a medium of historical residue, bleeding into the composition like memory itself. Rather than defining form with precision, the unstable washes create an atmosphere of dissolution, reinforcing trauma’s persistence on the surface of the image.

As seen in The Angry Mob and Coșer, Janco’s grotesque distortions do not function as direct documentation but as articulations of trauma through fragmentation. In Dupa Pogrom, this abstraction extends to gesture—figures marked by exhaustion rather than resistance, their movements neither fully constrained nor entirely free. The upraised arms of the central figure recall the motif of forced submission and spectral endurance familiar in Holocaust imagery. Whereas Olère’s figures in Auschwitz sketches register suffering with documentary immediacy, Janco distills trauma into uncertain, unresolved motion—where survival does not offer clarity, only a fraught persistence. This abstraction reinforces his broader approach to Holocaust representation, shifting from direct depiction to the destabilization of form itself.

Despite its insistent themes of loss and devastation, Dupa Pogrom does not wholly surrender to despair. Unlike the absolute finality of Coșer, this work contains movement, however burdened. Figures bend and reach, their postures suggesting both exhaustion and compulsion, grief and obligation. This tension, between mourning and the inexorable act of continuing, reinforces Dupa Pogrom’s position within Janco’s evolving Holocaust works, where survival is not a moment of triumph but an unstable condition, fraught with exhaustion and uncertainty. Ultimately, Dupa Pogrom does not reconstruct the past but renders its disintegration visible. Janco does not offer narrative resolution; instead, he creates a space where loss, endurance, and historical fracture remain entangled. As in previous works, he forces us to grapple with what it means to persist when the very foundation of the world has already been annihilated.

If Coșer presents the fixed spectacle of atrocity and Dupa Pogrom lingers in the exhaustion of survival, Humiliation Line (

Figure 4) captures the systematic choreography of persecution. Janco’s figures are not simply suffering—they are forced into a performance of degradation, their movements dictated by an external force that reduces them to mechanized instruments of submission. This is not just a march; it is a ritual of abasement, where posture itself becomes a mechanism of dehumanization.

The composition is structured through rigid, insistent diagonal rhythms, forcing the viewer’s gaze along the procession of hunched, depleted bodies. Unlike the chaotic dispersal of figures in The Angry Mob or the morbid suspension of Coșer, Humiliation Line locks its figures into a linear trajectory, reinforcing the sense of inescapability. The figures are compressed within the pictorial space, creating a claustrophobic visual field that denies them both spatial and bodily autonomy. Janco’s linework is fraught with tension. His strokes—fluid yet forcibly contained—capture both the exhaustion and forced compliance of the figures. The elongated, sinewy bodies fold in on themselves, their spines curving in submission, their faces hollowed by suffering. This grotesque distortion recalls the jagged, contorted anatomies of George Grosz’s satirical figures where war-maimed bodies are reassembled as half-human, half-mechanical parodies—faceless cogs within a remorseless social machine of oppression. Grosz’s savage exaggeration of the human form in such works transforms the crowded composition into a blistering critique of systemic cruelty, a visual strategy echoed by Janco’s own tightly confined procession of uniform, subjugated figures. However, while Grosz heightens distortion for satirical sharpness, Janco wields repetition as a weapon of inevitability. Instead of grotesque exaggeration, he uses rhythmic uniformity to mechanize suffering, making persecution feel procedural rather than chaotic. In Humiliation Line, the figures are not simply victims; they are subsumed into a system that dictates their very posture, reducing individuality to a function of oppression.

Figure 4.

Untitled (Humiliation Line), c. 1941. Ink and ochre wash on paper. Courtesy of the Janco-Dada Museum, Ein Hod, Israel. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

Figure 4.

Untitled (Humiliation Line), c. 1941. Ink and ochre wash on paper. Courtesy of the Janco-Dada Museum, Ein Hod, Israel. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

Facial expression is deliberately minimized yet deeply haunting. Unlike the explosive rage of The Angry Mob or the calcified grimaces of Coșer, here the figures are frozen in a paralysis of exhaustion, their downcast gazes and collapsed shoulders signalling resignation rather than resistance. The uniformity of their faces suggests the obliteration of individuality, reinforcing the systemic nature of their oppression. This recalls the visual logic of forced marches in Holocaust imagery, particularly in Olère’s Admission in Mauthausen (1945), where victims appear not as discrete individuals but as anonymous units within an unrelenting cycle of degradation. However, unlike Olère, whose documentary precision emphasizes historical specificity, Janco abstracts this suffering, making it a recurring structure of oppression rather than a singular event.

The presence of the guards ruptures this uniformity, introducing a grotesque asymmetry. Their bodies—rigid, angular, exaggerated in posture—stand in violent contrast to the limp, organic submission of their victims. The officer at the front, with his exaggerated sneer and commanding stance, embodies absolute control. He is not merely enforcing power; he is performing it. The theatricality of his posture, with one foot thrust forward and his arm extended in a directive gesture, transforms subjugation into spectacle. Rather than a faceless enforcer, he is a self-aware participant in a ritual of humiliation. This aligns Humiliation Line with representations of ritualized degradation in Holocaust visual culture, where perpetrators are not depicted as neutral enforcers but as active participants in a performative system of oppression.

Janco’s muted ochre washes, applied with calculated unevenness, further emphasize the ritualistic nature of this forced march. The pigment, streaked and irregular, resembles dust, grime, the residue of erasure, evoking both the literal filth of forced labor and the symbolic staining of historical memory. Unlike the disorienting spectral washes of Dupa Pogrom, where color seeps into the image like the leakage of memory itself, here color is deliberately coarse, reinforcing the imposed degradation. The unevenness of pigment does not create a dreamlike dissolution but a texture of dirt, marking the figures with the residue of forced submission rather than allowing them to fade into historical abstraction.

The background is skeletal—faint architectural lines sketch the outline of enclosures, fences, barriers—a spatial confinement that is both literal and psychological. Unlike the shattered, crumbling structures of The Angry Mob, which depict violence as an explosive force of destruction, here the architectural elements are tools of regulation, not passive remnants of brutality but active instruments of control. The structures do not simply contain the figures; they dictate their movement, enclosing them within a geometry of suffering. This spatial compression recalls the calculated enclosure of bodies in Holocaust iconography—where figures are not merely trapped but systematically arranged, forced into submission by the very space that holds them.

The relentless repetition of bent figures, each echoing the one before, mechanizes their suffering. Their postures, unnaturally aligned, transform them into cogs within an oppressive system rather than autonomous beings. This recalls forced labor iconography, where bodies are not merely enslaved but structurally rearranged into instruments of submission. The inversion of agency is key here: their bent forms do not only register physical exhaustion—they manifest subjugation as a forced posture, an imposed bodily script. Janco’s abstraction emphasizes that their suffering is not incidental but choreographed, turning the figures into extensions of the oppressive mechanism that controls them.

Unlike The Angry Mob, where violence erupts chaotically, or Coșer, where death is frozen into stillness, Humiliation Line captures the durational, procedural nature of persecution. There is no fixed endpoint to this march—it extends beyond the frame, suggesting a historical continuum of degradation. Janco’s figures are caught not in a singular event but in an ongoing ritual of humiliation—one that precedes the Holocaust and extends beyond it, inscribed into the longue durée of antisemitic persecution.

Within the visual canon of Holocaust memory, Humiliation Line bridges testimonial realism and modernist abstraction. While Olère’s works document specific atrocities, Janco resists direct representation, instead distilling persecution into an abstracted, ritualized structure. This strategic reduction is what makes Janco’s work distinct from Holocaust artists who foreground individual victimhood. His approach anticipates the strategies of later artists, such as Anselm Kiefer, who employs material decay and repetition to evoke the weight of historical trauma. Yet, where Kiefer’s monumental works operate at the scale of national memory, Janco’s figures retain an intimate fragility—his bodies are not anonymous abstractions but remnants of lived suffering.

Ultimately, Humiliation Line is not merely an image of oppression but an anatomical dissection of its mechanisms. Janco does not simply depict persecution; he reveals its architecture, exposing how violence is performed, ritualized, and mechanized. Through his masterful use of repetition, spatial compression, and gestural restraint, he forces the viewer to confront humiliation not as a singular historical moment but as a recursive, systemic condition.

This concern with systemic violence continues in The Spectacle of Violence (

Figure 5), where Janco shifts from depicting humiliation to exposing the mechanics of power itself. This composition exposes not only brutality itself but the mechanics of its execution, revealing how violence is ritualized into an instrument of power. Unlike The Angry Mob, which captures the explosive chaos of collective violence, or Coșer, which presents its aftermath as ritualized humiliation, The Spectacle of Violence exists in the liminal space between action and consequence—the moment in which power asserts itself through force, and the victims have already been transformed into objects of suffering.

The composition is architecturally divided into two strata of existence: the aggressors, looming above, their rifles raised in a visual choreography of dominance, and the victims below, crumpled into an entangled mass of violated flesh. This contrast is not merely spatial—it is ideological. Janco’s persecutors remain rigid, structured, and fully absorbed in their actions, while the victims dissolve into chaotic, writhing forms, reinforcing the asymmetry of power.

If earlier comparisons between Janco and Grosz focused on their shared use of grotesque distortion, The Spectacle of Violence marks their ultimate divergence. Where Grosz’s figures—bloated and sneering—expose the corruption of power by collapsing under their own absurdity, Janco’s do not become laughable. Their exaggerated expressions intensify rather than undermine their authority. The grotesque here is not satirical but integral to terror, transforming brutality into spectacle.

Janco’s treatment of victims further separates him from both Grosz and Holocaust testimonial painters, like David Olère. Unlike Grosz, who retains some degree of individuality even in suffering, Janco’s figures dissolve into an indistinguishable mass, stripped of singularity and consumed by violence itself. This abstraction is in stark contrast to Olère’s Priest and Rabbi, where the victims—though subjected to grotesque brutality—retain their identities as religious figures, embedded within a moral and historical framework. While Olère anchors his composition in testimonial specificity, ensuring that the viewer recognizes both perpetrators and victims as part of a historically situated act, Janco refuses this specificity. His victims are not positioned within a redemptive or symbolic framework; they are not martyrs, nor are they individuated witnesses to horror. They are simply consumed.

Janco does not allow the viewer the comfort of detachment. Instead, The Spectacle of Violence forces them into the structure of the event itself. Like lynching photographs, which functioned as performances of dominance, Janco’s composition presents violence as a staged assertion of power. Unlike Olère, who positions his victims with narrative dignity, Janco denies them even this final act of recognition. The viewer is not permitted to mourn or contextualize—only to witness obliteration.

Figure 5.

Untitled (The Spectacle of Violence), c. 1941. Ink and watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the Janco Estate. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

Figure 5.

Untitled (The Spectacle of Violence), c. 1941. Ink and watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the Janco Estate. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024. Reproduced with permission from DACS, License Number LR24-21207.

Janco’s grotesque stylization reaches its most extreme articulation here. The distorted, bestialized features of the aggressors, their exaggerated snarls, asymmetrical physiognomies, and jagged outlines, do not merely caricature antisemitic violence; they expose it as a system of dehumanization. These figures do not undermine their own authority but embody its excess, performing their role with grotesque theatricality. If Humiliation Line rendered oppression as forced choreography, here violence is no longer procedural—it is an ecstatic spectacle.

Janco’s handling of color reinforces the overwhelming brutality of the composition. The triadic palette—black for structural intensity, red for blood and brutality, and blue for the spectral chill of death—functions not as a naturalistic element but as a psychological force. Unlike Dupa Pogrom, where spectral tones of ochre and blue dissolved memory into the landscape, here color does not fade—it erupts. The red does not simply depict spilled blood—it spreads beyond the figures, consuming the space itself, mirroring violence’s inability to remain contained. The aggressors, by contrast, are marked by a stark, almost monochrome solidity, reinforcing their role as orchestrators of destruction rather than passive participants. This contrast is key to Janco’s visualization of systemic violence—his perpetrators remain stable, asserting dominance, while his victims disintegrate under the weight of force.

Janco’s modernist influences remain present but here they are stripped of their earlier utopian aspirations. His engagement with Dada fragmentation and geometric abstraction is no longer experimental—it becomes a violent formal strategy. The instability of form, seen earlier in Dupa Pogrom, is now total—the very structure of representation threatens to collapse under the weight of atrocity. The Spectacle of Violence is not merely a document of one moment of brutality—it actively resists closure. Unlike Dupa Pogrom, where survival was burdened by the weight of memory, here there is no memory—only the event itself, unfolding as an uncontainable rupture.

Janco’s Holocaust drawings do not offer resolution. They resist containment, rejecting the consolations of narrative coherence or commemorative solemnity. Instead, they enact trauma as an unstable, recursive force—one that fractures form, distorts space, and compresses bodies into near-abstraction. His grotesque stylization is not simply a means of intensifying horror; it is a visual articulation of violence’s irrepresentability. If Grosz exposes power as grotesque parody and Olère renders suffering as a testimonial record, Janco forces us into a world where violence consumes everything—even the very structure of representation itself.

By positioning violence as both a system and a spectacle, Janco does not simply depict the Holocaust—he exposes its mechanisms, implicates its viewers, and demands recognition of atrocity as ongoing, unresolved, and terrifyingly present. Yet, how do we make sense of this refusal to contain trauma within fixed visual narratives? Janco’s grotesque distortions do not merely represent suffering; they challenge the very premise of representation itself.

This difficulty is reflected in the reception of his Holocaust works, which, unlike his celebrated modernist contributions, remained in relative obscurity for decades. Caught between the shifting politics of Holocaust memory and the evolving priorities of postwar Israeli and European art, his drawings were never fully absorbed into either commemorative frameworks or avant-garde canons. This tension—the uneasy status of Janco’s Holocaust art—demands a closer examination of how we define the limits of Holocaust representation.

5. Holocaust Art and the Limits of Representation

Marcel Janco’s Holocaust drawings stand at the intersection of modernist fragmentation, testimonial art, and the crisis of visualizing trauma. His grotesquely distorted figures—contorted, fractured, dissolving—do not stabilize memory but enact its instability. The jagged enclosures, extreme compression of bodies, and frenetic dissolution of form in his works do not merely depict the Bucharest Pogrom; they confront the very failure of representation itself. His visual language refuses resolution, forcing the viewer into an encounter with the inadequacy of images to contain atrocity.

This problem, the tension between bearing witness and the failure of representation, has shaped postwar Holocaust memory and artistic discourse. Scholars, such as Georges Didi-Huberman, James E. Young, and Marianne Hirsch, have interrogated how Holocaust images function between presence and absence, necessity and impossibility. Didi-Huberman’s Images in Spite of All insists that Holocaust images are paradoxical: they are both necessary and insufficient, traces of an event that resists full visual documentation. Janco’s grotesque distortions exist within this paradox—his figures do not inhabit stable contours but dissolve, fracture, and contort, mirroring the instability of memory itself. His work does not reconstruct history; it enacts its rupture.

Janco’s refusal of visual stability sets him apart from Holocaust testimonial artists, such as David Olère, whose detailed, realist depictions function as direct visual testimony. Where Olère reconstructs genocide with forensic precision, anchoring his images in historical specificity, Janco rejects certainty altogether. His compressed compositions and radical distortions suggest that memory itself is unstable, filtered through displacement and the impossibility of direct representation. Rather than offering recognizable victims, his figures exist in a state of dehumanization, obliterating the possibility of individual identification.

Yet, Janco’s resistance to realism does not place him outside broader avant-garde responses to historical rupture. His work shares a conceptual lineage with George Grosz, whose use of distortion resists historical containment. Michael

White (

2020) argues that Grosz’s late works do not ‘document’ war but expose the instability of historical memory itself. This resonates with Janco’s drawings, where grotesque exaggerations and compressed compositions force a confrontation with atrocity that cannot be fully reconstructed. While Grosz’s fractured compositions reject narrative closure to highlight political violence, Janco’s Holocaust drawings similarly refuse commemorative frameworks, demanding an unresolved, destabilizing engagement with trauma.

Both Grosz and Janco use distortion not just as critique but as a refusal of aesthetic coherence itself. White emphasizes that Grosz’s later montages abandon the satirical clarity of his Weimar-era works—instead of revealing historical truth, they fracture it, mirroring the incompleteness of memory. This is precisely Janco’s strategy: his Holocaust drawings do not function as conventional testimony but as anti-testimonies, resisting closure and refusing the illusion of full visibility.

This resistance aligns Janco with broader ethical debates in Holocaust art. Claude Lanzmann’s landmark film Shoah (1985) famously refused archival Holocaust imagery, arguing that genocide cannot be reconstructed through images without turning suffering into spectacle. In Shoah, the refusal to show—the withholding of images—becomes a form of bearing witness itself. By eliminating visual representation, Lanzmann forces the viewer to engage with Holocaust memory through testimony and absence, making the void itself an ethical statement. His use of landscape imagery (trains, empty camps, sites of atrocity) reinforces this strategy: the past is never shown, only evoked.

Janco, however, confronts this dilemma through an opposite but equally radical method. Instead of refusing images, he overloads them with distortion. His grotesque figures are not absent but unbearably present—compressed, mutilated, barely holding together. Unlike Lanzmann, who rejects images to resist spectacle, Janco pushes visual form to its breaking point, rendering suffering through excess rather than negation. If Shoah preserves absence, Janco renders presence unbearable, forcing the viewer into a confrontation with horror as an unstable, fractured event. His figures are not witnesses in Lanzmann’s sense, where memory is verbal, constructed through testimony but embodiments of trauma itself—figures caught between material presence and dissolution. This distinction raises a key ethical question: does Janco’s grotesque stylization amplify suffering, or does it risk aestheticizing it? While Lanzmann’s erasure of images ensures that trauma remains unspectacular and unconsumed, Janco’s fragmented bodies expose the limits of containment. Rather than negating representation altogether, Janco forces us to see—and to see differently.

If Janco’s figures resist spectacle, they also refuse the psychological interiority of Felix Nussbaum’s Holocaust imagery. If Lanzmann’s withholding of images confronts the viewer with absence, Nussbaum instead personalizes suffering, offering the viewer a direct emotional engagement with the victim’s isolation. Unlike Nussbaum’s haunting, solitary depictions of Jewish victimhood, figures caught in frozen moments of despair, Janco’s subjects do not exist in quiet contemplation. They are thrown violently into spatial chaos, mangled, contorted, caught in the mechanics of dehumanization. If Nussbaum’s realism internalizes suffering as an individual experience, Janco externalizes it as a force of violent rupture. His grotesque distortion aligns with James E. Young’s argument that Holocaust memory must resist closure. Rather than offering a coherent image of the past, Janco’s drawings disorient, destabilize, and rupture the viewer’s ability to process trauma within a conventional framework. If Lanzmann withholds and Nussbaum personalizes, Janco fragments, dismantling not only the human form but the very legibility of suffering itself.

This radical destabilization, however, raises another question: does grotesque distortion risk undermining the seriousness of testimony? Janco’s work emerges from direct experience, yet its fragmentation, grotesque stylization, and refusal of stable form challenge traditional testimonial frameworks. His Holocaust drawings do not function as forensic records, nor do they attempt to stabilize memory through aesthetic containment. Instead, they enact suffering as an unresolved rupture, forcing the viewer into direct confrontation with trauma’s instability.

In the decades following the Holocaust, much of its artistic representation became shaped by the dilemmas of postmemory, as theorized by Marianne

Hirsch (

1997,

2012). Postmemory refers to the transmission of trauma across generations—where later artists reconstruct Holocaust memory not from lived experience but through archival fragments and historical absence. While postmemory artists emphasize symbolic gaps and deferred witnessing, Janco’s work insists on trauma’s immediate inscription, rejecting the temporal distance that defines postmemory aesthetics.

Unlike postmemory artists, who reconstruct inherited trauma through mediation, Janco’s Holocaust drawings are not acts of remembrance but direct responses to atrocity. Created in the wake of the Bucharest Pogrom, they do not rely on archival traces, secondhand testimony, or metaphorical reimaginings—they emerge from lived experience. His grotesque distortions do not function as retrospective reconstructions; rather, they register trauma in real time, capturing its immediacy rather than its afterimage. This distinction—between mediated reconstruction and direct witnessing—is critical. Postmemory artists must negotiate the ethics of representing a past they did not witness firsthand, ensuring they do not aestheticize suffering through retrospective symbolism. Janco, however, does not engage in historical reconstruction—his figures are not symbols of loss but unbearable presences, forcing an encounter that resists historical remove. While postmemory works often emphasize silence, erasure, and the spectral nature of memory, Janco’s drawings collapse the space between viewer and victim, confronting us with atrocity as a destabilized, uncontainable force.

By resisting both forensic realism and conceptual abstraction, Janco’s work defies the dominant categories of Holocaust visual culture. His drawings neither align with the testimonial precision of David Olère nor dissolve into the symbolic erasures characteristic of Anselm Kiefer. Instead, Janco’s work occupies an unstable middle ground, one that defies categorization, forcing a confrontation with memory that is neither purely testimonial nor fully abstract. Its refusal of resolution mirrors its unstable reception—obscured for decades within shifting postwar artistic and commemorative priorities. While his modernist contributions were widely recognized, his Holocaust works were largely marginalized, caught between competing demands for clarity, commemoration, and aesthetic progress.

This instability not only shaped Janco’s reception but also defines his uneasy position within Holocaust visual culture. While Holocaust art has often been structured around the divide between forensic realism and abstraction, Janco’s work resists both categories. The following section examines how his drawings navigate this tension—refusing both historical reconstruction and symbolic negation—and how his approach contrasts with other Holocaust artists who embraced either realism or abstraction.