Abstract

The silver-gilt container discovered in 1964 in the vicinity of Albarracin is currently housed in the Teruel Museum in Spain and represents a pinnacle of Taifa sumptuary arts. It was commissioned by the second monarch of the Kingdom of Albarracin, ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Khalaf (r. 1045-?), as a gift to his wife Zahr. The object’s elevated technical sophistication, coupled with its bespoke commemorative inscription, lends credence to the notion that it was crafted in the royal workshops responsible for the production of luxury items. The vessel’s functionality, which has fluctuated between its traditional consideration as a perfume bottle and the more recent identification as a canteen, has been adequately postulated but not sufficiently examined. The aim of this paper is to discuss the primary function of the object in question, particularly in relation to its distinctive flattened spherical shape. To achieve this, the study will delve into the close and well-established historical association between the morphology and function of objects, which tends to endure and perpetuate within the same cultural context over the centuries. By employing this methodology, we can establish a connection between the studied piece and the flasks used for the storage of sacred water (zamzam) that pilgrims brought back from Mecca after performing the Ḥajj. This typology can be traced back to the pre-Islamic period and persisted through the Ottoman matara model.

1. Introduction

A review of recent historiography on the design of objects in the 20th and 21st centuries reveals a close link between two essential elements that make up the configuration of any utensil: morphology and function. As numerous authors have observed, the structure of objects—whether they are for everyday use or more elite-purposed—is closely subordinated to the service they are intended to provide, which can be summarized in the maxim “form communicates function”.1 This correspondence between form and function is not exclusive to contemporary production; it also manifests when examining material culture preserved from past eras. In particular, this can be observed in the context of medieval Islam, where the harmonious union of these two elements has been celebrated as a significant factor contributing to the esthetic appeal of its artifacts. In this tradition, the complete artistic experience for the viewer is only achieved when form and function are in alignment (Shalem 2010, pp. 129–30).

Unfortunately, the link that associates and harmonizes both components is fragile and can sometimes easily break due to the loss of information associated with the passage of time and/or the complex biographies experienced by the artifacts. To reverse this information gap, it is necessary to engage in a meticulous exercise of observation, and to explore and reconstruct the cultural context of the artistic object, in order to investigate its silent and often hermetic primary use.

This paper will examine one of the most notable examples of Andalusi metalwork from the Taifa period. Since its discovery, the object has been subject to conflicting identifications, initially classified as a “perfume bottle” and more recently as a “canteen”. This ambiguity reflects the challenges inherent in precisely defining its function within the medieval Islamic context. The role proposed in this paper for this piece is based on the conviction that the link between design and function is preponderant and that this association remains immutable through the centuries, within the same cultural context, despite possible interferences or gaps that may surround our current understanding of the artifact. The formal comparison with other morphologically equivalent examples from earlier, similar, and later periods proves to be a valuable tool in this exploration and opens new avenues for investigating the past use of the analyzed object. As will be demonstrated in the following pages, the application of this study methodology enables us to pursue a previously unexplored avenue of inquiry, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of the object and its functionality as a liquid container. This is particularly relevant in the context of medieval Islam, where Ḥajj, or pilgrimage to holy sites, was a fundamental religious prescription based on practices and goals.

2. A Gift at the Court of the Banū Razīn

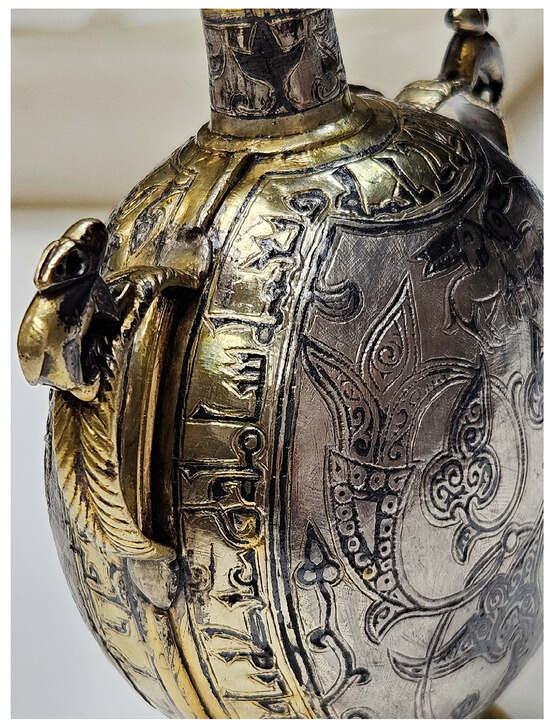

In 1964, an exquisite vessel crafted from silver-gilt was fortuitously unearthed on the “Tejadillos” estate, situated two kilometers from the town of Albarracin in the Spanish province of Teruel (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Following an initial emergency restoration, the object was incorporated into the Teruel Museum collection in the same year.2 In addition to its refined and exquisite craftsmanship in a noble metal,3 the piece is notable for its status as a “speaking object”,4 as it displays on its surface an engraved inscription in Kufic characters that provides valuable historical and documentary information. The text, which comprises an extensive votive and propitiatory formula (Martínez Núñez 2006, p. 310), also mentions the specific names of two of the individuals involved in the artifact’s creation: the patron and the recipient of the container (Figure 3).5 The vessel itself and the good wishes on the accompanying inscription are directed to a woman named Zahr, who is identified in the inscription as the wife of ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Khalaf, ḥāŷib of the Taifa kingdom of Albarracin.6 As previously demonstrated by Ortega Ortega (2007, pp. 45–46), this ruler was the second monarch of the Banū Razīn dynasty,7 the brother of the founder Huḏayl ibn Khalaf, from whom he inherited the laqab (honorific title) Mu’ayyid al-Dawla (“Upholder of the Dynasty”) mentioned in the dedication. The information provided by the Andalusi chronicler Ibn al-Abbār (1199–1260)8 in his Kitāb al-Ḥulla al-siyarā’ enabled this researcher to substantiate the proposal to extend the known lineage of this dynasty from three to five monarchs by including both ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Khalaf and his son Huḏayl. Ortega therefore identified these two dignitaries who had not been mentioned in the sources used until then, namely the Matīn of Ibn Ḥayyān and its later compilers and transmitters (Ibn Bassām, Ibn ‘Iḏārī, and the anonymous Chronicle of the kings of Taifas). The chronology of the reign of the patron of this beautiful container is unfortunately incomplete (Ortega Ortega 2007, p. 46). The date of his ascension to power is known (1045), but the date of his death and the exact moment of his succession by his son, who died in 1049 according to the chronicle, are unknown. The aforementioned information allows us to propose a tentative date for the object, which we can narrow down to a fairly narrow timeframe between 1045 and 1048 or 1049, given the lack of more precise documentary evidence.

Figure 1.

Canteen from Albarracin, Teruel; obverse. Teruel Museum, inv. 629 © Museo de Teruel. Archivo fotográfico (C. Id. n.° 154970).

Figure 2.

Canteen from Albarracin, Teruel; reverse. Teruel Museum, inv. 629 © Museo de Teruel. Archivo fotográfico (C. Id. n.º 154971).

Figure 3.

Canteen from Albarracin, Teruel; detail of the epigraphy. Teruel Museum, inv. 629 (photograph by the author).

As noted above, the recipient of the gift was the zawŷa (“wife”) of this ḥāŷib, about whom we have no documentary information other than the inscription itself. However, her personal name (ism), Zahr (“Flower”), suggests that she must have been a ŷāriya or a former slave who was freed and later made the legal wife of the ruler.9 The name itself is very eloquent, as it belongs to a semantic field associated with the world of sensory pleasures and nature, which was often used to name this category of unfree women (Marín Niño 2000, pp. 66–67; 2020, p. 109; Martínez Núñez 2006, pp. 310–11). Moreover, although the text does not specify it, this lady must also have been an umm walad (mother of a royal prince) and probably the mother of the heir to the throne, since the title of al-Sayyida al-’Āliya that she bears has been interpreted as equivalent to, or perhaps a variant of, the more common title of al-Sayyida al-Kubrà (“the Great Lady”) (Martínez Núñez 2006, pp. 310–11).10

In contrast to other preserved Islamic luxury artifacts, the epigraphy of this object omits any explicit indication of its workshop of origin. Nevertheless, the nominal patronage by the monarch and its technical and material sophistication unquestionably identify it as an official product from the palatial workshops (dār al-ṣināʽa), connected to the state propaganda policy transmitted by the Umayyads to the Taifa courts. One of the most notable self-affirmation strategies within this policy was the distribution of luxurious gifts as expressions of power, authority, and piety. The gifts were bestowed by the ruler upon family members, individuals within his closest circle (e.g., concubines), as well as government officials and diplomatic delegations. In return, these groups presented the ruler with luxurious goods, contributing to a system marked by ostentatious rivalry between kingdoms.11

While this work does not address the provenance of the container from the Teruel Museum, we believe that the proposed attribution to a potential precious metal workshop located in the Taifa of Toledo (Azuar Ruiz 2018, pp. 284–85) is inaccurate. This conclusion is based on a partial interpretation of the assessment, made by Ocaña Jiménez, regarding the style of calligraphy utilized in the inscription. In a letter to Almagro Basch, the distinguished epigraphist posited that the script of the container was “una obra toledana de la segunda mitad del siglo XI o muy influida por el arte epigráfico de aquella ciudad” (“a Toledan work from the second half of the 11th century or very influenced by the epigraphic art of that city”) (Almagro Basch 1967, p. 11). Although the second part of the statement has had minimal impact on historiography, we believe it is highly relevant. It is compatible with the probable existence of an independent, courtly production of metal objects in the Taifa court of Albarracin, distinct from the Banū Ḏī-l-Nūn, although potentially within their sphere of influence. This is evidenced by the documentary content of the dedicatory inscription, which explicitly names a member of the Banū Razīn as the patron of the artifact. Martínez Núñez (2018, p. 107) posits that the design of the calligraphy—characterized by highly stylized graphemes that extend vertically—resembles the Kufic script of other Taifas in the vicinity of Toledo, such as that of the Banū Hūd of Zaragoza, or more distantly, like that of the Abbadids of Seville (Martínez Núñez 1997, pp. 137–38). This would be consistent with the proposition that the sumptuary industry of Albarracin was autonomous from the Kingdom of Toledo.

The piece has been linked to other works that are technically and decoratively similar, including several nielloed silver caskets from the treasure of the Royal Collegiate of St Isidoro in León. Of particular note is the oval box, which is now preserved in the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid (inv. 50889). Additionally, two small heart-shaped containers are currently housed in the museum of the Royal Collegiate of St Isidoro itself (inv. IIC-3-089-002-0016 and 0017). Furthermore, a silver-gilt pyxis, also preserved in the same location (inv. IIC-3-089-002-0019), can be added to this list. In the absence of informative epigraphy, these items have been linked—without conclusive arguments—to the patronage activities of the Banū Ḏī-l-Nūn (Vidal Álvarez 2019; Azuar Ruiz 2018, pp. 284–85; Calvo Capilla 2001; Robinson 1992, p. 214, no 13). The Banū Ḏī-l-Nūn, who were politically more powerful than the rulers of Albarracin, have thus far been considered more capable of producing luxury items according to the traditional theory of patronage.12

Another argument in favor of the probable existence of a palatial metal workshop serving the Banū Razīn is the interest in luxurious displays exhibited by the rulers of this dynasty as a means of securing the prestige and splendor they needed to establish their legitimacy both within and outside their kingdom. This is substantiated by the archeological materials found in excavations conducted in various locations within the city of Albarracin, particularly in the castle and its surroundings. These findings include bronzes, glass, carved rock crystal of Fatimid origin, semi-precious stones, remains of lusterware ceramics or tin-glazed ceramics decorated in green and manganese, alabaster carvings, and even fragments of Chinese whitewares.13 Collectively, these artifacts demonstrate the notable financial capacity of this lineage as well as their access to distribution networks for these select products. This potential for luxury is also corroborated by written sources, which highlight the competitive zeal shown in matters of magnificence, particularly in relation to other mulūk, and especially against the rival kingdom of Toledo (Ortega Ortega 2018, p. 458).

Ibn ’Iḏārī, citing information from Ibn Ḥayyān, makes a pertinent observation regarding the dynasty’s founder, Huḏayl ibn Khalaf ibn Razīn (1013–1044/45): “His wealth was abundant, as he engaged in a competitive pursuit of wealth with his neighbor and counterpart Ismāʽīl ibn Ḏī-l-Nūn [...]” (“Fue copiosa su riqueza, puesto que compitió en reunir dinero con su vecino y semejante Ismāʽīl ibn Dī-n-Nūn […]”) (’Iḏārī 1993, p. 156). This desire for ostentation is also reflected in this emir’s concern with acquiring musical instruments and excellent singing slave girls. He paid very high prices for these in order to assemble the most exquisite musical–vocal ensembles (satā’ir) among the kings of al-Andalus (Crónica anónima 1991, pp. 57–58; ’Iḏārī 1993, pp. 156–57). This display of wealth is further illustrated by the splendid gift one of his descendants, Yaḥyà ibn ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Huḏayl, known as Husām al-Dawla (“Sword of the Dynasty”) (r. 1103–1104), presented to Alfonso VI of Castile when the latter took the Marches. This gift was composed of “jewels, garments, horses, mules, and precious objects [belonging] to kings, of which a description could not be made” (“alhajas, vestidos, caballos, mulos y objetos preciosos [propios] de los reyes, acerca de los cuales no se podría hacer la descripción”) (Crónica anónima 1991, p. 61). The information provided by this report is of great significance, as it pertains to the presentation of objects “belonging to kings”, an expression that we posit should be understood as luxury goods produced in aulic manufactories.

The available material and textual evidence, when considered alongside the object at the center of this study, provide insight into a rich and vibrant cultural and artistic milieu within the Taifa of Albarracin. This necessitates a reevaluation of the opulent significance of this court, which should be elevated to a prominent position among the Andalusi states and granted a more central role in the context of studies dedicated to the art of this period, where it has been marginalized for decades (Guichard and Soravia 2005; Clément 1997, pp. 319–20; Viguera Molins 1992, pp. 65–69, 1994; Wasserstein 1985, pp. 93, 101).

3. Perfume Bottle Versus Canteen

From the moment of its accidental discovery in the second quarter of the 20th century, the Albarracin vessel immediately attracted the interest of researchers, who, in the earliest publications devoted to its analysis, encountered the challenge of defining and determining its primary use. In the paper in which he presented the piece to the scientific community, Almagro Basch (1967, pp. 10, 12) offered a preliminary assessment, suggesting that it may have been used as a perfume container, albeit with a shape reminiscent of a canteen. This interpretation was linked to the Andalusi domestic sphere of fragrances and personal cosmetic sets. His proposal was widely disseminated in the last century and was reproduced with minimal variation in the majority of subsequent publications and catalog entries from the 1980s onwards, coinciding with the numerous exhibitions in which the vessel was featured (Escriche Jaime 2008; Ars Mechanicae 2008, p. 25; Esteras Martín 2007a, 2007b; España medieval 2005, p. 343; Aquaria 2006, p. 459, III.48; Centellas Salamero 2002; Restaurar Hispania 2002, p. 266, n. 62; Casamar Pérez 2000; Escriche Jaime 2000; Makariou 2000; Giralt and Eusebi García i Biosca 1998, p. 133; Robinson 1992, p. 219, n. 16; Atrián Jordán 1989, pp. 56, 58; Casamar Pérez 1988; Corral Lafuente and Peña Gonzalvo 1986, p. 40; Atrián Jordán 1968, p. 46) The hypothesis’s immediate impact on nomenclature was notable, as the vessel came to be popularly known as the “Albarracin perfume bottle”.

In this context of discursive homogeneity, the contribution of Professor Pérez Higuera (1994, p. 80) is particularly noteworthy. Despite maintaining the object’s status as an essence container within the courtly sphere, she was also able to underscore its exceptional typology within the Andalusi luxury context, pointing out its formal linkage with the “matara” of the Ottoman period.14 These, she asserts, “served not only to store water reserved for the sultan but also had a ceremonial use as a symbol of royal power, which justifies their richness and splendid decoration” (“al servicio de guardar el agua reservada para el sultán unían el uso ceremonial como signo de poder real, lo que justifica su riqueza y espléndida decoración”).

A notable shift in the historiography regarding the role assigned to the object was observed only in the latter part of the 21st century. A recent contribution presented at the Medieval Archaeology Conference in Aragon (Punter Gómez et al. 2018) definitively discarded the previously entrenched position that the object was a perfume bottle. This position was arbitrary and lacked morphological justification. Instead, the contribution makes a much more sensible proposal of use as a canteen.15 The Teruel Museum promptly updated its exhibit labels and website to reflect the new nomenclature,16 which has been included in subsequent exhibition catalogs (Escriche Jaime 2019).

The morphology of this object is as distinctive as any other within the known repertoire of Andalusi sumptuary arts. However, it is frequently found as part of domestic furnishings, used as a vessel for storing and transporting liquids, with a surprising formal durability throughout the different stages of Islamic presence in the peninsula (Rosselló Bordoy 2002, pp. 41–42).17 Furthermore, there are direct antecedents in the material culture of antiquity, such as the Gallo-Roman bronze canteen decorated with enamels found in Pinguente (Piquentum), Buzet (Istria/Croatia), which is currently housed in the Kusthistorischen Museum in Vienna (VI 1197). This item may have been part of a rider’s grave goods.18 Despite the corroboration of its existence through archeological evidence, the term used to describe this form in al-Andalus has not reached us. In the Maghreb, it is known as qar’a, while in Syria, it is referred to as matara (Rosselló Bordoy 1991, pp. 87, 150, 165).

4. Souvenirs from the Holy Land: Ampullae and Pilgrim Flasks in Late Antiquity and Their Typological Transfer to Islam

As previously observed, the vessel discovered in Albarracin exhibits a formal configuration consistent with the typology of Andalusi canteens. However, its production in a refined material such as silver-gilt is unusual. The object in question is a flattened, spherical body from which a neck protrudes. This neck is organized into two distinct areas, separated by a raised listel. The upper section, which serves as a mouthpiece, is conical in shape with an outwardly curved lip19 Simultaneously, the object is situated upon a moderately flared cylindrical base, which is supported by a protruding flat plate. The base is affixed to the body of the object by a band or listel in high relief, in the form of a clamp, that encircles the entire perimeter of the object. Two free-standing handles, crowned by a pair of four-footed animals, probably hares, are welded to this band. The ears are pierced to allow for the attachment of a small chain, which enables the object to be hung or suspended.20 This feature makes it a portable object, designed for transport, which is consistent with both its manageable size and the fact that the piece is decorated on both sides. Unfortunately, the stopper that would prevent the liquid contained within from spilling has been lost.21

This format—as previously mentioned—has its roots in classical civilizations. It was also a prevalent typology among portable objects in circulation throughout the Mediterranean during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Among the most renowned and sought-after souvenirs among pilgrims returning from the Holy Land were ampoules (ampullae), small containers (measuring between 5 and 10 cm) predominantly crafted from silver. These vessels were primarily utilized to contain sanctified oil from celebrated churches, such as the Holy Sepulchre or the Holy Cross of Jerusalem. These containers exhibited a highly uniform structural design, comprising a flattened spherical body adorned on both sides and a truncated conical neck, where rings were affixed to facilitate suspension from a chain. Notable examples of this type include the renowned Holy Land ampullae, predominantly dated to the 6th century, which are preserved in the treasures of Italian sanctuaries such as Monza and Bobbio (Figure 4). In some cases, inscriptions on the containers refer to the sacred oil from the Tree of Life and the holy oil carried by pilgrims.22 In his Homilies, Saint John Chrysostom asserts that these sanctified substances possessed healing properties, bestowed blessings (eulogia) upon their owner—hence the name “eulogiae” that these containers often received—and provided protection during the lengthy journey home (Weitzmann 1977, p. 564).

Figure 4.

Pilgrimage ampoule with image of the Holy Sepulchre, s. VI, Bobbio Abbey, Italy Public Domain.

However, during their peregrinations and sojourn in the Holy Land, travelers would also visit other sanctuaries where the relics of early Christian martyrs or saints were venerated. These included Saint Simeon Stylites (d. 459) in Antioch, Saint Menas (d. 309) near Alexandria, and Saint Thecla (d. s. I) in Meriamlik (Asia Minor).23 Similarly, pilgrims would procure mementos in the form of small flasks containing water from a prosimate spring or sanctified oils from the lamps of the temples. Such objects were imbued with considerable thaumaturgical significance and were also regarded as healing amulets. The flasks were manufactured from inexpensive materials, such as lead or terracotta, and produced in large quantities (Mostalac Carrillo and Guiral Peregrín 2015). Their morphology was comparable to that of the ampullae of Monza and Bobbio, but they often had large handles for suspension, which could be attached to the body, possibly around the neck or waist, using cords, chains, or bands. A considerable number of these flasks have been preserved in museums and national and international collections. Many of them originate from Coptic Egypt or Palestine and span a broad chronological range, from the 4th to the 7th century.24

In a compelling argument, Avinoam Shalem (2016, pp. 251–55) has proposed that the typology of these portable Christian souvenirs may have served as a source of inspiration for certain Islamic artisans in the production of opulent pieces, suggesting a transfer of the model to the Islamic context. The author provides two later examples, somewhat larger in size than the pilgrim flasks but closely related to them in terms of morphology. These include an Ayyubid brass vessel with silver inlay housed at the Freer Gallery of Washington (inv. F1941.10), and a glass flask painted with enamel and gold from Syrian or Egyptian production, preserved in the Diocesan Museum of St. Stephen in Vienna. Both of these examples date back to the second half of the 13th century. The author’s dissertation focuses on the analysis of the evident formal analogies between the designs but does not address the question of whether the transmission of the model also involved the continuity of the religious use associated with the ampullae.

In this context, the Albarracin vessel would therefore be understood to have a particular significance. Chronologically earlier than the examples provided by Shalem, we may consider this an intermediate link in the transmission of the prototype under discussion, from late antiquity to the medieval Islamic courts. Consequently, if we apply the previously discussed axiom that form follows function—or, alternatively, that form originates from necessity—the cross-cultural transfer of the design would not only affect the configuration of the object but would also imply the transfer of its associated functionality. Therefore, this should mirror that of the devotional containers to which it bears such a close morphological resemblance25. This hypothesis permits the association of the object with a context that has remained hitherto unexplored: that of Islamic pilgrimage (Ḥajj).

5. The Albarracin Vessel in the Context of the Islamic Pilgrimage (Ḥajj). A Possible Portable Receptacle for Sacred Water?

The Islamic pilgrimage is a duty mentioned in the Quran (III: 91–97) that all Muslims are obliged to perform at least once in their lifetime.26 This may be undertaken either in person or through a delegate, in cases of illness or lack of financial means, as indicated in Islamic jurisprudence.27 This religious precept, the fifth pillar of Islam, has been a central tenet since the Middle Ages and continues to be a fundamental aspect of Islamic practice. The journey to Mecca and the visit to the Kaʽba sanctuary constitutes a ritual that has been transmitted across centuries and serves as a unifying element within the Muslim community (umma). This unites the faithful, regardless of their place of origin or the era in which they lived, on a historical and geographical level. The ceremony consisted, and still consists, of performing the tawāf (circumambulation) seven times, in a counterclockwise direction, commencing from the eastern corner where the Black Stone is located. The faithful will endeavor to touch or kiss it, or, at the very least, point to it, on each lap, while repeating the takbīr “God is [the] greatest” (‘Allāhu ʼAkbar) (Abdel Haleem 2013, pp. 1–2). Subsequent to the completion of this ritual, it is advised that the pilgrim engage in two cycles of prayer (rakʽā) at the nearby Maqam Ibrahim, the stone where, according to tradition, Ibrahim (Abraham) stood in prayer and left the imprints of his feet, and then proceed to the nearby Zamzam well (Abdel Haleem 2013, p. 3).

5.1. The Zamzam Well

The well known as Zamzam is a sacred site, currently underground, located 20 m east of the Kaʽba, within the circumambulation area.28 Integrated into pre-Islamic pilgrimage practices, it retained its importance with the advent of the new religion, which was promoted by Muhammad. The faithful come to drink from it throughout the year, but especially during the annual Ḥajj and the ‘Umrah (the “lesser” pilgrimage, which can be performed at any time) (Ghabin 2020, p. 64).

According to Islamic tradition, this well was revealed to Hayar (Hagar), the second wife of Ibrahim (Abraham) and the mother of Ismail (Ishmael). Following God’s instructions, Ibrahim departed from his wife and infant in the arid valley of Mecca. Hagar desperately searched for water to provide her child with sustenance but was unable to locate any. According to the narrative, she traversed the distance between the hills of Safa and Marwa (situated 400 m apart) on foot, seven times, enduring the intense heat, until she heard the voice of the Archangel Gabriel, who instructed her to return to her son because water would emerge from that location. Upon observing the emergence of the water, Hagar collected it in a pool made of sand, preserving it in the form of a well (Ghabin 2020, p. 64).29 Later, due to the sins of the Arab tribe of Jurhum, the spring disappeared and was rediscovered through divine revelation in the form of four dreams that were conveyed to the Prophet’s grandfather Muhammad, ‘Abd al-Muṭṭalib (d. 578) (Ghabin 2020, p. 66; Hawting 1980). It seems probable that the presence of water in this location was the reason why a sanctuary was first established in Mecca (Porter 2012, p. 72).

The primary ritual observed during the Ḥajj that commemorates Hagar’s miraculous discovery of the well is the sa’i. Upon completion of the tawāf, each pilgrim is required to traverse the distance between the hills of Safa and Marwa seven times, while engaged in prayer, thereby retracing the journey made by Ibrahim’s wife. This establishes an important connection between Islam and the prophets Ibrahim (Abraham) and Ismail (Ishmael). During this ritual, or at its conclusion, the faithful partake of the Zamzam spring (Ghabin 2020, p. 66; Abdel Haleem 2013, p. 3; Porter 2012, p. 72). The ritual requires the worshiper to turn towards the Kaʽba, pronounce God’s name, breathe three times, and drink until satisfied, concluding with a thanksgiving to God (Ghabin 2020, p. 67). Both Andalusi traveler Ibn Ŷubayr (1145–1217) and the Tangerine Ibn Battuta (1304–1377) provide descriptions of the well and this widespread practice during their visits to the sanctuary (Ibn Ŷubayr 2007, pp. 152–53; Ibn Battuta 2005, pp. 239, 247).

The corpus of Hadith literature is replete with references to the purported healing properties of water from the Zamzam well. It is believed that this water not only has the capacity to heal the body but also to purify both the body and the soul. Furthermore, it is thought that this water has the power to exert a religious influence on those who consume it. These narratives recount how the Prophet used the precious liquid as a means of preparation for his journey to Jerusalem and his ascension to heaven (al-Isrāʼ wal-miʽrāj). Additionally, Muhammad is also attributed the categorical phrase, “The waters of the Zamzam are good for any purpose for which they are drunk” (Ghabin 2020, p. 67). For this reason, since the early days of Islam, the faithful, in addition to drinking from Zamzam during the prescribed Ḥajj ceremonies, would return to their homes with containers of sacred water from this spring to offer as gifts to family, friends, and the sick in their community, the latter as a form of charity (Ghabin 2020, p. 67; Porter 2012, p. 72). This religious practice persists in the present era and has resulted in the extensive commercialization of the product. Moreover, this blessed liquid was used to sprinkle the shrouds and graves of the deceased (Siraj and Tayab 2017, p. 26; Porter 2015, p. 103), and, appealing to its protective powers, was even employed in a more sophisticated manner to create ink for writing Qur’ans (Porter 2012, p. 72).

5.2. Zamzamiyyas: Precious Containers of Sacred Water

Among the souvenirs that any medieval Muslim traveler typically brought back from their pilgrimage to Mecca as a gift and memorabilia, bottles containing sanctified water from the Zamzam spring are particularly noteworthy. This water, imbued with supernatural properties, was meticulously conveyed back to their respective destinations in receptables that the devout individuals transported with them from their places of origin. These containers—or others specially acquired during their sojourn in Mecca—were replenished at the sacred well (Porter 2015, p. 103). Such containers are referred to as zamzamiyyas (Porter 2012, p. 72; Porter and Saif 2013, p. 79).

Similar to containers from the Christian context, these Islamic pilgrim flasks were crafted from an assortment of materials, including ceramic and glass, and demonstrated a range of quality levels contingent upon the owner’s economic standing. These receptacles are distinguished by their adherence to a standardized canteen typology, which has remained consistent throughout the centuries and across the various territories of the Dar al-Islam and which aligns with that of late antique ampoules. A considerable number of examples from the medieval period have been preserved, whether in ceramic (Day 1935; Voigt 2025; al-Moadin 2025; Naghawy 2025) or in more luxurious materials. Among these are the Mamluk piece from the British Museum (inv. 1869,0120.3), made of glass with gilded and enamel decoration,30 and the previously mentioned piece of Syrian or Egyptian production, preserved in the Diocesan Museum of St. Stephen in Vienna. Additionally, there are metal pieces, such as the Ayyubid brass flask from the Freer Gallery of Washington (inv. F1941.10), which is also referenced by Shalem. Given the format of these containers, it is possible that rather than being mere vessels for common water, they contained holy water from the Zamzam well. This potential liturgical function, associated with pilgrimage, is briefly mentioned, though not fully explored, by Rosselló Bordoy (1991, p. 165) in his formal analysis of the rural canteen model within the context of al-Andalus.31

As previously suggested by Pérez Higuera (1994, p. 80), when noting its formal similarity to the Albarracin container, the survival of this typology beyond the Middle Ages within the Islamic sphere is constituted by the so-called “matara” from the Ottoman period. These receptacles, often made of leather and used on journeys, military campaigns, and others to contain liquids within the context of the Ḥajj, could hold water from the sanctuary of Mecca.32 Some of these pieces reached such a high level of craftmanship that they were presented as diplomatic gifts. For example, Sultan Murad III gifted an embroidered leather canteen to Emperor Rudolf II, possibly in 1581, along with an invitation to attend the circumcision festivities of his son. This item is currently housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (inv. C.28).33 In imitation of the shape of the leather prototypes, and with slight variations in structure, pieces were also made in other more select materials. An example of this is the gilded copper container dating from the 17th century from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. 1984.100).34 This rests on a foot, similar to the container from Albarracin, in order to facilitate support and prevent the container from tipping over and spilling its contents.

The widespread distribution of the prototype throughout India has also yielded intriguing examples that illustrate the model’s popularity. These include a brass pilgrim flask dated to the early 17th century currently located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. 1992.50) which provides a compelling testament to the model’s enduring appeal (Porter 2012, p. 74, Figure 41; Zebrowski 1997, pp. 198–99, pls. 301, 517; Desai 1985, n. 108).35 Furthermore, in select Mughal and Deccan miniatures, comparable vessels are depicted within scenes of quotidian life or the Ḥajj, thereby providing a general indication of their probably utilitarian function. This is illustrated in folio 15a of the manuscript The Pilgrim’s Companion by Šafiʽ ibn Vali, illuminated in India, potentially Gujarat, circa 1677–80 (Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Mss 1025), where several of these objects are depicted suspended from a tripod in a camp during a rest stop of a caravan of pilgrims from North Africa (Porter 2012, p. 153, Figure 106; Rogers 2010, pp. 284–87, n. 332–41; Leach 1998, pp. 124–29; n. 34).36

6. Conclusions

The close historical association between the canteen shape and the transport of sacred water or oil, which has its roots in classical and late antiquity and has remained tenacious and unaltered in Islamic culture throughout its various eras and territories practically to the present day—as discussed in detail in previous pages—constitutes sufficient evidence to propose that the Andalusi vessel found in Albarracin may have primarily functioned not as a mere container for common water but as a luxurious zamzamiyya or pilgrim flask. This hypothesis would provide the object with a new and previously unknown dimension, associated with one of the five pillars of the Islamic faith: the Ḥajj pilgrimage. This would help to alleviate the functional “amnesia” that has surrounded the artifact until very recently, enriching its understanding. A religious reinterpretation that is consistent with the formal characteristics of the flask, specifically designed to be carried, either hanging from the neck or waist, is also plausible. This is due to the perforations shown in the ears of the hares that decorate the handles and the accompanying chain.

Conversely, the artifact represents an exemplar of the ostentatious waste that the kingdom of Albarracin espoused as part of the cultural and artistic framework spearheaded by the state in response to the pervasive competitiveness among the various Taifa courts throughout the 11th century. This period saw the creation of royal workshops for the production of luxury objects (dār al-ṣināʽa), where it is evident that this piece was crafted due to its quality, technical refinement, and unique epigraphic features. Concurrently, the object provides a female interpretation with a gender perspective, as the recipient of the gift was a lady linked by marriage to the royal lineage of the Banū Razīn family of Santa María del Oriente. This information is highly relevant to the projection of elite women beyond the strictly intimate and domestic sphere. The artifact is an individualized object bearing the name of the owner along with that of her husband and promoter. It is plausible that she received it as a personal gift for her use during the Ḥajj, or as a devoted present filled with the precious holy water from the Zamzam well, which was brought back from al-Andalus by a distinguished pilgrim returning from their journey.

In sum, the formidable challenge that we art historians face in attempting to “fill in” the considerable gaps present in our discipline entails listening to, conversing with, and, in numerous instances, simply observing objects and allowing them to convey their messages. In instances such as the one we have addressed in these pages, the solution lies in paying close attention, observing meticulously, and recognizing that function is always strictly determined by form.

Funding

National Research Challenge Grant of the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities, as part of the Research Project “Artistic transfer in Iberia (9th to 12th centuries): the reception of Islamic visual culture in the Christian kingdoms” PID2020-118603RA-I00, 2021–2025, funded by MCIN/AEI 10.13039/501100011033.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to the Museum of Teruel, particularly to the restorer, Ms. Pilar Punter Gómez, and the librarian-archivist, Ms. Ana Andrés Hernández for their kind assistance and facilities during the examination of the piece and the consultation of the archival documentation

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The phrase “form follows function” is a modernist design principle popularized by the American architect and designer Louis Sullivan (1856–1924). On its later application to object design, see, among others (Norman 1998; Lambert 1993). |

| 2 | For details regarding the circumstances of the discovery and the subsequent accession of the piece into the museum’s collection, see Teruel Museum Archive, file n. 511/1964/1. The discovery was fortuitously made by Manuel Roy Maicas, a local resident engaged in agricultural activities at the time. He initially offered the find to the Town Council of Albarracin, which declined to purchase it. Ultimately, the Teruel Museum acquired the piece and entered it into its collection on 18 May 1964 with accession number 629. Given the item’s state of conservation, comprising loose handles, a broken foot, and numerous dents and detached fragments, an initial emergency restoration was deemed necessary. This was carried out by Aladrén Jewelers in Zaragoza at a cost of 9.500 pesetas. |

| 3 | About its manufacturing technique and subsequent restoration in 2009, see (Punter Gómez et al. 2013, 2018). |

| 4 | On “speaking objects” from the World of Islam, see the following: (Shalem 2010, pp. 131, 135; Taragan 2005; Blair 1998, pp. 98, 112). |

| 5 | “Perennial benediction, general well-being, continual prosperity, elevated position, honor, assistance, divine help and good direction [toward the good and the equity] for the most excellent lady Zahr, wife of the hajib Mu’ayyid al-Dawla ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Khalaf, may God assist him”. Translation in (Robinson 1992, p. 219, nº 16; Ocaña Jiménez in Almagro Basch 1967, p. 8). |

| 6 | This kingdom was also called as-Sahla (the Plain) by the Arab chroniclers and its capital was Santa María del Oriente (Šantamariyyat as-Šarq), the modern city of Albarracin. See (Crónica anónima 1991, p. 57; Ortega Ortega 2007, pp. 29, 42, 44; Boch Vilá 1959, pp. 52–57). |

| 7 | Their monarchs were also known as the Banū l-Aṣlaʽ (the sons of the Bald One). Concerning this dynasty, see, among others (Ortega Ortega 2016; Boch Vilá 1959; Prieto y Vives 1926, p. 63). |

| 8 | https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/37658/ibn-al-abbar (accessed on 17 July 2024). |

| 9 | These luxury slaves, for whom high prices were paid, were not only physically attractive and capable of providing sexual gratification to their owners, but had also been carefully educated to sing, play instruments, and declaim verses at palace gatherings (Marín Niño 2020, pp. 115–16; Barton 2015, pp. 33–38). |

| 10 | On the different ranks and honorific titles of women in the harem, see (Marín Niño 1987, pp. 50–52; López de la Plaza 1992, pp. 73–74). |

| 11 | On gift policy in Umayyad times, see (Silva Santa-Cruz 2014). |

| 12 | This group of objects presents a notably relevant associated issue that should not be overlooked when analyzing them together. A more profound examination of this issue is beyond the scope of this paper. The fact that they are technically and stylistically similar does not necessarily indicate that they were all produced in the same artistic center. The diaspora of Andalusi artisans following the fitna, which compelled them to depart from the Umayyad capital and resettle in courts under the authority of local powers that offered more promising work prospects, probably entailed the relocation of artists from one Taifa to another in accordance with the fluctuations in labor conditions and demand. This may have contributed to the formation of these similarities. On the dispersion of these masters, see (Silva Santa-Cruz 2013, pp. 262–63; Calvo Capilla 2011, p. 86). |

| 13 | (Ortega Ortega 2007, p. 69; 2018, pp. 455, 462–68). For the ceramic repertory found, see (Hernández Pardos 2018). |

| 14 | This same idea is taken up years later in (Esteras Martín 2007a). |

| 15 | This option had only been previously suggested for this object in (Esco et al. 1988, p. 164, n. 126). |

| 16 | https://www.museodeteruel.es/colecciones/edad-media/al-andalus/cantimplora/ (accessed on 25 July 2024). |

| 17 | See, among others, some examples of different chronologies created from earthenware and glass from the excavations of the Alcazaba of Almeria and the Castle of Santa Barbara (Overa), in (Ramos Linaza 2015, pp. 377–79, n. 232–36, Figure 105; p. 590, n. 411). |

| 18 | https://www.khm.at/en/object/64921/ (accessed on 25 July 2024). |

| 19 | Its overall dimensions are 16 cm high, 14.5 cm wide, and 7 cm deep. |

| 20 | The chain has been partially preserved and is in a state of considerable fragility. The cord is composed of silver thread, woven into a braided structure comprising three strands. Until 2009, the chain was knotted to two rings threaded into the perforations, apparently attached during the 1964 restoration immediately after the object was discovered. The chain has been detached from the container and is currently on display in a free-standing position (Punter Gómez et al. 2018, pp. 421, 424). |

| 21 | It is not possible to ascertain whether the preserved chain remnants are part of the vessel’s suspension system or the attachment of the stopper. |

| 22 | On these ampoules, see (Barag and Wilkinson 1974; Grabar 1958). |

| 23 | About the latter, see (Kristensen 2016). |

| 24 | For the characteristics of these flasks and a selection of examples, see, among others (Fluck et al. 2015, pp. 136–37, n. 150–52; Arad 2007; L’ Art Copte 2000, pp. 40–41, n. 6–7; Arias Sánchez and Novoa Politela 1999; Kiss 1989; Metzger 1981; Weitzmann 1977, pp. 576–78, 585–88, n. 515–16, 524, 526–27). |

| 25 | Rosselló Bordoy (1983, pp. 338, 357) defines the existence of a generic type of unguent bottle canteen for the Andalusian context. |

| 26 | An overview of the Islamic pilgrimage in the Middle East can be found in (Mols and Buitelaar 2015; Tagliacozzo and Toorawa 2015; Porter and Saif 2013; Porter 2012; Peters 1994). |

| 27 | On the pilgrimage by proxy (ḥaŷŷ al-badal), see (Carro Martín 2021, pp. 209–11; 2023, p. 130). |

| 28 | About the Zamzam well, see (Ghabin 2012, 2020; Porter 2012, pp. 72–73; Chabbi 2002). |

| 29 | Another version of the story in Genesis, 21: 17–19. |

| 30 | https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1869-0120-3 (accessed on 10 July 2024). |

| 31 | This is also included in (Cavilla Sánchez-Molero 2005, p. 107; Ramos Linaza 2015, p. 377). |

| 32 | In recent decades, several examples of these characteristics have been sold on the art market. See, among others, Sotheby’s, London, October 2021, lot 224 (https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/arts-of-the-islamic-world-india-including-fine-rugs-and-carpets-2/a-rare-ottoman-leather-matara-flask-turkey-16th) (accessed on 25 August 2024) and Sotheby’s, London, October 2023, lot 145 (https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2023/arts-of-the-islamic/an-ottoman-tombak-water-flask-matara-turkey-16th) (accessed on 25 August 2024). |

| 33 | (Atil 1987, p. 165, n. 105); www.khm.at/de/object/373747/ (accessed on 10 July 2024). |

| 34 | See (Welch 1987, p. 125, Figure 96); https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/453238 (accessed on 25 August 2024). |

| 35 | https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/453335 (accessed on 26 August 2024). |

| 36 |

References

- Abdel Haleem, Muhammad. 2013. The Religious and Social Importance of Hajj. In The Hajj: Collected Essays. Edited by Venetia Porter and Liana Saif. London: The British Museum Press, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro Basch, Martín. 1967. Una joya singular en el reino moro de Albarracín. Teruel 37: 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- al-Moadin, Mona. 2025. “Pilgrim’s Flask” in Discover Islamic Art. Museum with No Frontiers. Available online: https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;sy;Mus01;33;en;v (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Aquaria. Agua, territorio y paisaje en Aragón. 2006. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón-Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza.

- Arad, Lily. 2007. The Holy Land Ampulla of Sant Pere de Casserres—A Liturgical and Art-Historical Interpretation. Miscel·lània Litúrgica Catalana 15: 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Sánchez, Isabel, and Feliciano Novoa Politela. 1999. Ampullae: Ampollas de peregrino en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional. Boletín del Museo Arqueológico Nacional XVII: 141–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ars Mechanicae. Ingeniería medieval en España; 2008. Madrid: Ministerio de Fomento.

- Atil, Esin, ed. 1987. The Age of Sultan Süleyman Le Magnificent. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Atrián Jordán, Purificación. 1968. Museo Arqueológico Provincial de Teruel. Nueva sala de cerámica popular turolense. Boletín Informativo de la Excma. Diputación Provincial de Teruel IV: 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Atrián Jordán, Purificación. 1989. El Museo Provincial de Teruel. Revista de Arqueología 96: 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Azuar Ruiz, Rafael. 2018. Arqueología de la metalistería islámica de al-Andalus durante los reinos de Taifa (siglo V HG/XI DC). In The Pisa Griffin and the Mari-Cha Lion. Metalwork, Art and Technology in the Medieval Islamicate Mediterranean. Edited by Anna Contadini. Pisa: Pacini Editore, pp. 281–92. [Google Scholar]

- Barag, Dan, and John Wilkinson. 1974. The Monza-Bobbio Flasks and the Holy Sepulchre. Levant 6: 179–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, Simon. 2015. Conquerors, Brides, and Concubines. Interfaith Relations and Social Power in Medieval Iberia. Philadelphia: University of Penssylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Battuta, Ibn. 2005. A través del Islam. Translation, Introduction and Notes by Serafín Fanjul and Federico Arbós. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Sheila S. 1998. Islamic Inscriptions. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boch Vilá, Jacinto. 1959. Albarracín musulmán. Parte primera. El Reino de Taifas de los Beni Razín hasta la constitución del señorío cristiano. (Historia de Albarracín y su Sierra directed by Martín Almagro Basch, Vol. II). Teruel: Instituto de Estudios Turolenses. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Capilla, Susana. 2001. Caja. In Maravillas de la España Medieval. Tesoro Sagrado y Monarquía. Directed by Isidro G. Bango Torviso. Madrid: Junta de Castilla y León-Caja España, vol. I, p. 112, n. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Capilla, Susana. 2011. El arte de los reinos de taifas: Tradición y ruptura. Anales de Historia del Arte 2: 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Carro Martín, Sergio. 2021. Observaciones sobre la peregrinación islámica delegada en los trabajos de Chardin, Niebuhr y Burckhardt (siglos XVII-XIX). Estudios de Asia y África 56: 207–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carro Martín, Sergio. 2023. Una lectura iconográfica del ḥaŷŷ a través del certificado ORB.50/11 y otras copias impresas del s. XIX. Eikón Imago 12: 129–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casamar Pérez, Manuel. 1988. Esenciero de plata de Albarracín. In Exposición de Arte, Tecnología y Literatura Hispano-Musulmanes. Madrid: Instituto Occidental de Cultura Islámica, pp. 80–81, n. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Casamar Pérez, Manuel. 2000. Esenciero. In Dos milenios en la historia de España. Año 1000, año 2000; Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte—Sociedad Estatal España Nuevo Milenio, pp. 238–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cavilla Sánchez-Molero, Francisco. 2005. La cerámica almohade de la isla de Cádiz (Ȳazīrat Qādis). Cádiz: Servicio de Publicaciones Universidad de Cádiz. [Google Scholar]

- Centellas Salamero, Ricardo. 2002. Esenciero. In Aragón, de reino a comunidad. Diez siglos de encuentros. Zaragoza: Cortes de Aragón, pp. 148–49, n. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Chabbi, Jacqueline. 2002. Zamzam. In EI2: The Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, pp. 440–42. [Google Scholar]

- Clément, François. 1997. Pouvoir et légitimité en Espagne Musulmane à l’époque des taifas (Vè-XIè siècle). L’imam fictif. Paris: Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Corral Lafuente, José Luis, and Francisco Javier Peña Gonzalvo, eds. 1986. La cultura islámica en Aragón. Zaragoza: Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza. [Google Scholar]

- Crónica anónima de los reyes de taifas. 1991. Introduction, Translation and Notes by Felipe Maíllo Salgado. Madrid: Akal.

- Day, Florence E. 1935. Some Islamic Pilgrimbottles. Berytus. Archeological Studies II: 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, Vishakha N. 1985. Life at Court: Art for India’s Rulers, 16th–19th Centuries. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Esco, Carlos, Josep Giralt, and Philippe Sénac. 1988. Arqueología islámica en la Marca Superior de Al-Andalus. Huesca: Diputación de Huesca. [Google Scholar]

- Escriche Jaime, Carmen. 2000. Esenciero. In Aragón, reino y corona. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón—Ibercaja, p. 408, n. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Escriche Jaime, Carmen. 2008. Esenciero. In Encrucijada de culturas. Zaragoza: Ibercaja, pp. 56, 263, n. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Escriche Jaime, Carmen. 2019. Cantimplora. In Las artes del metal en al-Andalus; Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte-Museo Arqueológico Nacional, pp. 230–31. [Google Scholar]

- España medieval y el legado de Occidente; 2005. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Acción Cultural Exterior de España, México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, Instituto Nacional de Antopología e Historia, Barcelona: Lunwerg.

- Esteras Martín, Cristina. 2007a. Esenciero. In El Cid. Del hombre a la leyenda. Directed by Juan Carlos Elorza Guinea. Madrid: Junta de Castilla y León-Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Esteras Martín, Cristina. 2007b. Esenciero. In Tierras de frontera. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón-Ibercaja, p. 469, n. 277. [Google Scholar]

- Fluck, Cäcilia, Gisela Helmecke, and Elisabeth R. O’Connell, eds. 2015. Egypt: Faith After the Faraons. London: The British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Ghabin, Ahmad. 2012. The Zamzam Well Ritual in Islam and its Jerusalem Connections. In Sacred Space in Israel and Palestina. Edited by Marshal J. Berger, Yitzhak Reiter and Leonard Hammer. London: Routledge, pp. 116–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ghabin, Ahmad. 2020. The Well of Zamzam. In Sacred Waters. A Cross-Cultural Compendium of Hallowed Springs and Holy Wells. Edited by Celeste Ray. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Giralt, Josep, and Joan Eusebi García i Biosca, eds. 1998. El Islam y Cataluña. Barcelona: Institut Català de la Mediterrània. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1958. Les Ampoules de Terre Sainte (Monza-Bobbio). Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Guichard, Pierre, and Bruna Soravia. 2005. Los reinos de taifas. Fragmentación política y esplendor cultural. Málaga: Sarriá. [Google Scholar]

- Hawting, Gerald R. 1980. The Disappearance and Rediscovery of Zamzam and the “Well of the Kaʽba”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 43: 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Pardos, Antonio. 2018. La cotidianidad en la alcazaba andalusí de Albarracín (Teruel): El testimonio de la cerámica. In II Jornadas de arqueología medieval en Aragón. Edited by Julián M. Ortega Ortega. Teruel: Museo de Teruel, pp. 225–59. [Google Scholar]

- ’Iḏārī, Ibn. 1993. La caída del Califato de Córdoba y los Reyes de Taifas (al-Bayān al-Mugrib). Study, Translation and Notes by Felipe Maíllo Salgado. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, Zsolt. 1989. Les ampoules de Saint Menas découverts à Kôm el-Dikka (1961–1981) (Alexandria, V). Varsovie: Centre d’Archéologie Mediterranéenne de l’Académie Polonaise des Sciences-Centre Polonais d’Archéologie Mediterranéenne de l’Université de Varsovie au Cairo. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, Troels Myrup. 2016. Lanscape, Space and Presence in the Cult of Thekla at Meriamlik. Journal of Early Christian Studies 24: 229–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lambert, Susan. 1993. Form Follows Function? (Desing in the 20th Century). London: Victoria and Albert Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, L. York. 1998. Paintings from India. The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, VIII. London: Khalili Collections. [Google Scholar]

- López de la Plaza, Gloria. 1992. Al-Andalus: Mujeres, Sociedad y Religión. Málaga: Universidad de Málaga. [Google Scholar]

- L’ Art Copte en Égypte. 2000 ans de Christianisme. 2000. Paris: Institute du Monde Arabe-Gallimard.

- Makariou, Sophie. 2000. Botella con el nombre de Zahr. In Las Andalucías. De Damasco a Córdoba. Paris: Hazan-Institut du Monde Arabe, p. 151, n. 167. [Google Scholar]

- Marín Niño, Manuela. 1987. Notas sobre onomástica y denominaciones femeninas en al-Andalus (siglos VIII-XI). In Homenaje al Profesor Darío Cabanelas Rodríguez, con motivo de su LXX aniversario. Granada: Universidad de Granada, Departamento de Estudios Semíticos, vol. I, pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Marín Niño, Manuela. 2000. Mujeres en al-Ándalus. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Marín Niño, Manuela. 2020. Mujeres andalusíes: Memoria, patrimonio e identidad. In Tejiendo pasado. Patrimonios invisibles. Mujeres portadoras de memoria. Coordinated by Alicia Torija López and Isabel Baquedano Beltrán. Madrid: Dirección General de Patrimonio Cultural, pp. 103–22. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Núñez, María Antonia. 1997. Escritura árabe ornamental y epigrafía andalusí. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 4: 127–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martínez Núñez, María Antonia. 2006. Mujeres y élites sociales en al-Andalus a través de la documentación epigráfica. In Mujeres y Sociedad Islámica: Una Visión Plural. Coordinated by María Isabel Calero Secall. Málaga: Servicio de Publicaciones, Universidad de Málaga, pp. 287–328. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Núñez, María Antonia. 2018. La epigrafía de las taifas andalusíes. In Tawā’if. Historia y Arqueología de los reinos de taifas (siglo XI). Edited by Bilal Sarr. Granada: Alhulia, pp. 85–118. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Catherine. 1981. Les ampoules à eulogie du Musée du Louvre. Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Mols, Luitgard, and Mario Buitelaar, eds. 2015. Hajj: Global Interactions Through Pilgrimage. Leiden: Sidestone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mostalac Carrillo, Antonio, and Carmen Guiral Peregrín. 2015. Un molde para la fabricación de “ampullae” metálicas hallado en las excavaciones del teatro de “Caesaraugusta” (Zaragoza). In De las ánforas al museo. Estudios dedicados a Miguel Beltrán Lloris. Coordinated by Isidro Aguilera Aragón, Francisco Beltrán Lloris, María Jesús Dueñas Jiménez, Concha Lomba Serrano and Juan Ángel Paz Peralta. Zaragoza: Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza-Institución Fernando El Católico, pp. 667–82. [Google Scholar]

- Naghawy, Aida. 2025. “A pilgrim’s flask” in Discover Islamic Art. Museum With No Frontiers. Available online: https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;jo;Mus01;27;en (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Norman, Donald A. 1998. The Desing of Everyday Things. London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Ortega, Julián M. 2007. Anatomía del esplendor. Fondos de la sala de Historia Medieval. Museo de Albarracín. Zaragoza: Fundación Santa María de Albarracín. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Ortega, Julián M. 2016. La dawla Raziniyya. Súbditos y soberanos en la taifa de Santa María de Oriente, siglos V.H./XI.dC. Ph.D thesis, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Ortega, Julián M. 2018. Una gobernanza poscalifal: Poder patrimonial y prácticas de consumo en el sultanato taifa de Albarracín. In Tawā’if. Historia y Arqueología de los reinos de taifas (siglo XI). Edited by Bilal Sarr. Granada: Alhulia, pp. 447–71. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Francis E. 1994. The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and to the Holy Places. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Higuera, María Teresa. 1994. Objetos e imágenes de al-Andalus. Barcelona: Lunwerg. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Venetia, ed. 2012. Hajj. Journey to the Heart of Islam. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Venetia. 2015. Gifts, Souvenirs, and the Hajj. In Hajj: Global Interactions Through Pilgrimage. Edited by Luitgard Mols and Mario Buitelaar. Leiden: Sidestone Press, pp. 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Venetia, and Liana Saif, eds. 2013. The Hajj: Collected Essays. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto y Vives, Antonio. 1926. Los Reyes de Taifas. Estudio Histórico-Numismático de los Musulmanes Españoles en el Siglo V de la Hégira (XI de J.C.). Madrid: Centro de Estudios Históricos. [Google Scholar]

- Punter Gómez, María Pilar, Isabel Sánchez Marqués, Alejandro Chamorro Salillas, Josefa Parra Granell, and Ángel Luis García Pérez. 2013. Restauración del esenciero de plata procedente de Los Tejadillos, Albarracín. Museo de Teruel. In IV Congreso Latinoamericano de Conservación y Restauración de Metal; Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Deporte, pp. 420–32. [Google Scholar]

- Punter Gómez, María Pilar, Mohamed Oujja, and Marta Castillejo. 2018. La cantimplora taifa de Albarracín: Conservación-restauración y análisis mediante espectroscopias láser. In Jornadas de arqueología medieval en Aragón: Reconstruir Al-Andalus en Aragón. Edited by Julián M. Ortega Ortega. Teruel: Museo de Teruel, pp. 439–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Linaza, Manuel, coords. 2015. Almariyya. Puerta de Oriente. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía. [Google Scholar]

- Restaurar Hispania; 2002. Madrid: Ministerio de Fomento-Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte.

- Robinson, Cynthia. 1992. Box and Perfume Bottle. In Al-Andalus. The Art of Islamic Spain. Edited by Jerrilyn Dodds. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 214, 219, n. 13, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, John Michael. 2010. The Arts of Islam. Masterpieces from the Khalili Collection. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló Bordoy, Guillermo. 1983. Nuevas formas en la cerámica de época islámica. Bolletí de la Societat Arqueològica Lul·liana 39: 237–360. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló Bordoy, Guillermo. 1991. El nombre de las cosas en al-Andalus. Una propuesta de terminología cerámica. Palma de Mallorca: Museo de Mallorca—Societat Arqueològica Lul·liana. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló Bordoy, Guillermo. 2002. El ajuar de las casas andalusíes. Málaga: Sarrià. [Google Scholar]

- Shalem, Avinoam. 2010. If Objects Could Speak. In The Aura of Alif. The Art of Writing in Islam. Edited by Jürgen Wasim Frembgen. Munich: Berlin: London: New York: Prestel Verlag, pp. 126–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shalem, Avinoam. 2016. The Poetics of Portability. In Histories of Ornament. From Global to Local. Edited by Gülru Necipoğlu and Alina Payne. Princeton: Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. 250–61. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Santa-Cruz, Noelia. 2013. La eboraria andalusí. De la Córdoba omeya a la Granada nazarí. BAR International Series 2522; Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Santa-Cruz, Noelia. 2014. Dádivas preciosas en marfil. La política del regalo en la corte omeya andalusí. Anales de Historia del Arte 24: 527–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, M. A., and M. A. K. Tayab. 2017. Water in Islam. In Water and Scriptures. Ancient Roots for Sustainable Development. Edited by Konduru Raju and Manasi Subramaniam. New York: Springer International Publishing, pp. 15–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliacozzo, Eric, and Shawkat M. Toorawa, eds. 2015. The Hajj: Pilgrimage in Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taragan, Hana. 2005. The “Speaking” Inkwell from Khurasan: Objects as “World” in Iranian Medieval Metalwork. Muqarnas 22: 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal Álvarez, Sergio. 2019. Arqueta ovalada. In Las artes del metal en al-Ándalus; Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Viguera Molins, María Jesús. 1992. Los reinos de taifas y las invasiones magrebíes. Madrid: Mapfre. [Google Scholar]

- Viguera Molins, María Jesús, coords. 1994. Los reinos de taifas. Al-Andalus en el siglo XI. Historia de España dirigida por Menéndez Pidal, t. VIII/I. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, Friederike. 2025. “Pilgrim bottle” in Discover Islamic Art. Museum with No Frontiers. Available online: https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;se;Mus01;13;en (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Wasserstein, David. 1985. The Rise and Fall of the Party-Kings. Politics and Society in Islamic Spain, 1002–1086. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed. 1977. Age of Spirituality. Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art-Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Stuart Cary. 1987. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Islamic World. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Ŷubayr, Ibn. 2007. A través del Oriente. Riḥla. Introduction, Translation, Notes and Indexs by Felipe Maíllo Salgado. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowski, Mark. 1997. Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India. London: Laurence King Publishers. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).