Abstract

In A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel, concerns about class, decorum, and civility intersected with contemporary dialogue about the distinction between humans and animals, specifically, how human children needed to be educated to be distinguished from the wild, uncivilized state of animals and peasants. Both animals held significance surrounding behaviors that separated the moral from the immoral; cats and eels were pets and food, and they were used in baiting pastimes: cat clubbing and eel pulling. Paired with the children, Leyster’s choice of animals raised multiple moral questions and allowed for multiple interpretations, making the work widely appealing and setting Leyster apart in a tight market for genre paintings. These layers of possible meanings continue to make the work compelling today and shed light on how visual culture reflected and reinforced human–animal and social class distinctions.

1. Introduction

In A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel (Figure 1), a painting from around 1635 by the Dutch painter Judith Leyster, concerns about class, decorum, and civility intersected with contemporary dialogue about the distinction between humans and animals. Both animals held significance surrounding behaviors that separated the moral from the immoral. Paired with the children, Leyster’s choice of animals raised multiple moral questions and allowed for multiple interpretations, making the work widely appealing and setting Leyster apart in a tight market for genre paintings. The painting depicts a young girl wagging her finger at the viewer while a boy grabs an eel in his left hand, holding it behind the girl.1 He uses his right arm to clutch a protesting kitten. The girl directs her eyes at the viewer while pulling the kitten’s tail. The boy looks up and to his right. Both children grin with their teeth showing. The eel is small and translucent, and the kitten is a wide-eyed gray tabby. The girl seems aware of the foolishness in playing with these animals, literally pointing out the presence of important messages to be considered.2

Figure 1.

Judith Leyster, A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel, c. 1635/40, 59.4 × 48.8 cm, oil on panel. National Gallery, London. Image in the public domain.

Most obviously, the painting is a visual combination of various Dutch proverbs about transience: cats and eels both easily elude humans’ grasps. Cats and eels are well-known animals from everyday life, and they had multiple potential meanings in the seventeenth century. Their slippery iconography made for a perfect combination with children because the subjects at once define and call into question assumed-as-natural categories and hierarchies. As others have shown, both cats and eels held symbolic significance surrounding moral behavior (Hofrichter 1989, p. 64; Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, pp. 139, 200; Kuretsky 2011b, pp. 266–68). By providing potential clientele with a multiplicity of interpretive options, from moralizing iconography about class and education to questions about who has rationality, Leyster set herself apart in a tight market. Whether fodder for contemporary seventeenth-century European discussions around the relation between human and non-human animals and the corresponding concerns about the role of women, children, and peasants in society, or simply enjoyed as a playful scene mimicking lived experience, her pictures’ ambiguity gave viewers multiple opportunities to make meaning, then as now.

Both cats and eels were and are common and, as animals, instrumentalized.3 Animals had use-value as well as monetary value. The cat was a pet and hunter, and the eel was food. They also were entertainment: each was used in animal baiting pastimes played at Dutch festivals: cat clubbing and eel pulling (katknuppelen and palingtrekken). Cat clubbing involved putting a cat in a barrel, hanging the barrel between trees, and throwing clubs at it, while eel pulling entailed stringing a live eel from a line and pulling it from below, either on a boat across a canal or, if on land, on horseback, as can be seen in Solomon van Ruysdael’s Drawing the Eel4 (Figure 2). The idea behind cat clubbing was to terrify and chase a cat, symbolically driving away evil; eels were food. Both, in their challenging aspects—hitting a barrel and chasing a scared cat and pulling down a slippery eel while in a boat on water—also added to humans’ enjoyment of watching the mishaps that inevitably occurred, not unlike humans watching outtakes or bloopers today, but with no concern for the well-being of the animal.

Figure 2.

Salomon van Ruysdael, Drawing the Eel, 1650s, oil on wood, 29 1/2 × 41 3/4 in. (74.9 × 106 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image in the public domain.

The early modern confusion surrounding essential nature reveals the human construction of simplistic hierarchies and binaries, such as male/female, human/animal, white/black, adult/child, and property owner/peasant. Post-structural cultural theorists, including Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, and Carol Adams, have investigated the ways in which humans have constructed culture in relation to power, deconstructing dichotomies to expand how humans understand culture.5 In the seventeenth century, most people believed one’s essential nature was immutable and linked to social status (Van Nierop 2015, p. 23). The question of the animal was implicated in this hierarchical social schema. Understanding human–animal relations involves the intersection of class, politics, and religion in humans’ determination of who had the right to control bodies.6 Status, of course, was visually apparent in gesture, dress, and comportment. While visual materials such as emblem books, literature, and religious tracts dictated clear prescriptions for how moral citizens should act in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, the reality and complexity of human life cannot be boiled down into mere aphorism.7 This picture can be about fleeting fortune and the need to train children to become moral, governing adults, and it can be about the bigger question about the relations between humans, children, and animals.

While cats and eels served as objects of torture for those humans stuck in a rigid early modern hierarchy, a major theme in animal studies today is that human animals and non-human animals share more similarities than past humans have wanted to acknowledge, particularly our shared vulnerabilities and individuality.8 Our similarities and singularities, therefore, inspire humans to compassionately engage with animals as individuals rather than as objects, materials, or instruments, which has been the basis of anthropocentric (and correspondent misogynistic, racist, classist) thinking, allowing for continued exploitation and cruelty. Cultural construction is dynamic: it is a constant process of co-creation, reinforcement, deconstruction, and re-creation.9 Indeed, what makes this picture continue to be appealing is it suggests that the relational dynamics of the subjects depicted here are always in flux and can be questioned. Viewers of the painting today can consider this slippage between what is constructed by a class to distinguish itself and how that construction reinforces and reveals human-made boundaries.

Today, the human instrumentalization of animals becomes evident by looking at the picture. Both the kitten and eel are playthings for children, relegated to objects for amusement. Neither the kitten nor eel in the painting is worth much. The eel is too small for good eating; the kitten is also undeveloped. Much has already been written about early modern attitudes toward animals (Wolloch 2006; Fudge 2004). While not universal, early modern Europeans across societies generally othered animals and saw them as lower than humans on a scale often based on Genesis and Aristotle’s Great Chain of Being and, later, Descartes’ hypothesis that animals were non-feeling, non-rational beings. Even while such a stance toward animals generally might hold true, individuals might have had very different attitudes toward a particular being based on their own contexts and experiences. We know that the famous humanist Justus Lipsius (1547–1606) loved and missed his dogs when they died, as did Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687) love and miss his puppy Geckie when he died.10 Clearly, cats, too, were part of early modern households; Rembrandt depicted them (see below), and Michel Montaigne (1533–1592) famously mused about his cat’s subjectivity in “An Apology for Raymond Sebond”:

when I play with my cat, who knows whether I do not make her more sport than she makes me? We mutually divert one another with our monkey tricks: if I have my hour to begin or refuse, she also has hers.(de Montaigne 1910, p. 9)

But, following Aristotelian and Cartesian conceptions, most early modern humans did not think animals were capable of thought. Aristotle believed humans alone have the power to think rationally and speak and, therefore, lead an ethical life. Self-consciousness and conscious decision-making are folded into this concept of rationality. Non-human animals, in this schema, lack these capacities and, therefore, are subordinate to humans. Aristotle also thought some humans naturally subordinate: women, children, and slaves had not fully realized rationality. In the early modern period, the Chain of Being mapped onto class and racial distinctions, where the opposite of rational superior, white male human supremacy was irrational, female, black, and animal.11 As has been—and sometimes continues to be—the case for women, children, foreigners, peasants, or slaves, othering and objectification allowed for instrumentalization, exploitation, and, ultimately, violent death. Cruelty to animals is justified by a belief that someone is a superior life and has the right to take the life of another. In the seventeenth century, this supreme power was afforded to the sovereign or, in the Dutch Republic, the governing class; at festivals such as Carnival, when the world “turned upside down”, peasants took animal life in baiting games and in mock executions, in a display of power akin to the elite hunting and dissecting animals in their leisure and scientific pursuits. Peasants killed animals in baiting games, but hunting, a sport requiring land, and scientific investigation, requiring time to learn, were the purview of the nobility and elite. Both allowed humans to enjoy themselves and show dominance by killing animals.12

Certainly, Lipsius, Huygens, and Montaigne saw the individuality of their animal companions; whether a viewer of Leyster’s picture would generalize the kitten or relate her to one’s own pet is unknowable. Constantijn Huygens’ son Christiaan (1629–1695), the famous scientist, seems to have held theriophilic ideas yet still participated in vivisection, according to Nathaniel Wolloch (Wolloch 2000). The ambivalence—or cognitive dissonance—with which early modern individuals might have understood animals allowed for both recognizing animal suffering and, at the same time, acknowledging that their suffering might be natural or useful. Some painters recognized the intellectual benefit of using a picture to pose a dialogic or rhetorical question. As Koenraad Jonckheere has illuminated, the questye, or discursive issue, was an important component of a liberal education, and common in intellectual life (Jonckheere 2019, p. 74). In Leyster’s painted scenes, there are always moral choices to be made by both viewers and the human subjects shown. Leyster asks the viewer to consider the following: will these children, similarly undeveloped, learn their moral duties, or will they continue to be like the animals with whom they play? Today, we can also consider the subjectivities of these animals and push against animal instrumentalization. The question of instrumentalization in human and non-human animal relations is still open for discussion: Is it ethical to eat meat? Which animals? Does it matter how they are raised? Is it ethical to breed and use mice and rats in scientific labs for the benefit of humanity?

If post-structural gender/queer/feminist, post-colonial, and critical race theories have taught humans anything, it is that social categories and boundaries are constructs, not essential nature; even while some biology is innate, culture affects how that may be expressed. Humans create, codify, and reinforce boundaries and categories that benefit them or their group. Visual culture helps codify and reify them. Yet, when Leyster made this image, most people viewing it would have thought the existing social order was “natural”. While A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel illustrates common sayings, it also illuminates how dangerously tenuous and flexible the boundaries were that Dutch society had constructed between classes and between human children and animals. Leyster depicted children and animals playfully, seeming to question whether the children would grow up properly, in a lighthearted “realistic” scene. As a woman painter, some might also have assumed she had an intuitive understanding of children and enjoyed the realism on that level. Such a schema of lightened, but still complex, moral assumptions helped her to establish her niche.

2. The Market for Leyster’s Playfully Ambiguous Pictures

When Leyster made A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel, she was probably living in Amsterdam with her husband, Jan Miense Molenaer (1610–1668). The work is signed iudith*, and although undated, Hofrichter suggests she may have signed it because she made it in Amsterdam, where her monogram may have been less well known than in Haarlem.13 Molenaer and Leyster had married in June 1636, three years after she had enrolled in St. Luke’s Guild in Haarlem. The couple soon moved to Amsterdam, where they lived until 1648. Ellen Broersen suggests that the art market in Amsterdam may have drawn them there, as well as their attempts to avoid debt collection and outbreaks of the plague in Haarlem (Broersen 1993, p. 21). In Amsterdam, the artist couple was part of the middle class; by 1647, they were able to buy a house in the country, near Heemstede, and a house in Haarlem, where they probably lived and worked.14 Citing various seventeenth-century commentators, Henk van Nierop interprets the general categorization of society by seventeenth-century Dutch into three classes, even while acknowledging that “class” is a nineteenth-century concept (Van Nierop 2015, pp. 23–24, 38). Nobles, regents, and merchants made up the elite, generally urban, ruling class. Shopkeepers and skilled artisans, such as Leyster and Molenaer, were in the (upper) middle class. Unskilled laborers, peasants, and indigents lived their lives at the bottom of this social hierarchy.15 The Haarlem and Amsterdam markets for which Leyster painted were differentiated by the consumers who could afford various products. The wealthiest regents and burgomasters commissioned portraits, and well-to-do collectors could purchase history paintings; genre scenes might be collected by discerning merchants and other middle-class buyers.16 Leyster and Molenaer painted for the market that appealed to middle-class clients.

For the consumers who made up Leyster’s clientele, distinguishing themselves from peasants and animals was a way to show their burgerlijk status—their cultivation and civilization—and concomitant rightful governing capacity. In the Dutch Republic, the ideal citizen was civilized and educated; the peasant boer, animal, or irrational human was not. Visual and literary culture reinforced these ideals, often in entertaining forms. For example, the popular Dutch poet Gerbrand Bredero (1585–1618) warned against being like a peasant, associating them with cruelty toward animals and people—as acting animalistic and brutish—although, as Svetlana Alpers suggested, the poem is meant to be comedy, entertaining and moralizing at the same time (Alpers 1975–1976, pp. 122, 137–39). In his famous poem Peasant party (1621), Bredero describes the boerengeselschap as debaucherous, lustful, avaricious, and cruel. The peasants going to Vinkeveen (a village near Amsterdam) take part in goose pulling, among other sordid revelry, and the party ends with a drunken and violent (uncontrolled) brawl. With a figurative wink, the poem clearly acknowledges elites’ desire to have fun yet still warns them to stay away from the peasants who cannot control themselves (see Bredero [1621] 1980; Schenkeveld 1991).

In A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel, the two children playfully interrogate the viewer’s own morals. Baiting games were played in the Netherlands into the early twentieth century, and one benefit to the winner of the eel pull was getting to eat the eel.17 This was especially important to peasants and laborers, who could eat the prize and use the prize money. For both cat clubbing and eel pulling, bets were made, and gambling added to the stakes of watching (or playing) each game. Yet, in the seventeenth century, hard-line Calvinists in the Dutch Republic wrote tracts against the behaviors and activities that such games precipitated; they attacked gambling, along with cards and dice. Most people, however, continued to play games and attend festivals; even wealthier urban citizens went to rural festivals or played at being the Virgilian Shepherd and Shepherdess, as can be seen in Ruysdael’s picture (Kettering 1983) (Figure 2).

Indeed, while preachers found fault with much of the entertainment at traditional rural Dutch festivals, it seems from numerous depictions in visual and literary culture that peasants and festival entertainment became tropes that the rising merchant class was able to use to distinguish itself and mimic the elite. Von Bogendorf-Rupprath has made the connection between Shrovetide partying and the costumes in Leyster’s Two Children with a Cat (Figure 3). Von Bogendorf-Rupprath suggests that the jovial mood of the children is reinforced by motifs related to Carnival, including the cat and its association with mischief and choleric temperament. She furthermore notes the features of the plumed hat, the frog fasteners, and the bright colors of the boy’s clothing as similar to comic figures and charlatans at such festivals.18 Robert Darnton has also explained that cats were frequently the victims of torture and execution at Carnival in France until the end of the eighteenth century, and baiting and cat clubbing were festival events. He explains these examples of cat torture within the frame of class distinction via violence.19 As with A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel, the boy’s and girl’s clothing connotes class and behavior and raises questions for the viewer about the appropriateness of that behavior, and whether the child will be morally educated and thereby distinguished from both animals and peasants.

Figure 3.

Judith Leyster, Two Children with a Cat, c. 1629/35, oil on canvas, 61 cm (24 in); width: 52 cm (20.4 in). Private Collection. Image in the public domain.

Eel pulling and cat clubbing involved violence and gambling and held similar tensions to the play by the children depicted, naughtily pulling kitten tails or playing with eels. Depicting and alluding to children’s play and baiting games were ways for the well-heeled to recognize the tension of violence and temptation and play it out in the safety of a picture, poem, or play. Although churchy proscriptions against festival fun were widely ignored, it seems logical that the ambivalence the Dutch burgers felt toward what was expected of them and what they desired, and how they sought to visually distinguish themselves, created an ample market for the kinds of layered playful genre scenes in which Leyster and Molenaer specialized (Dekker et al. 2001, p. 56).

3. Who Could Be Moral?

Emblem books, prints, and paintings shed light on the potential layers of Leyster’s A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel. In the Dutch Republic, the governing elite used paintings, prints, books, and all manner of outward display to underscore their civility and impart to parents how to engender citizens of the Republic. Moral guides and schoolbooks were sought after to reinforce status through education. Popular advice manuals, such as the books on marriage and child rearing by Jacob Cats (1581–1660), used visuals and entertaining rhymes to outline how parents should morally educate. The strategy of moralizing by pleasure, or teaching and learning the virtues with fun, was frequently employed (Dekker 2009, p. 169).

Ideas about cats and eels were reproduced in emblem books, scientific treatises, and natural histories, with the authors categorizing human animals and non-human animals in an anthropocentric world. These books assisted the rising merchant and ruling classes in how to educate their children—to make them distinct from the animals and peasants, used as foils to upright moral citizens. Emblem books, histories, and manuals on civility made up many a merchant’s and aristocrat’s library.20 Genre paintings were aesthetically pleasing, complex, delightful, and instructive. Animals in visual culture, including cats and dogs, could underscore a message of well-trained children by alluding to and reinforcing the dichotomies of human/animal and classes.21

Cats and eels were often associated with fleeting fortune and the fickleness of love. Good fortune in life and love was a result of rational decision-making and morality: just because a person has something does not mean that she or he can hold on to it. While one might be born into a particular class position and not expect to move up the social ladder, falling out of good fortune was a real concern for those in the upper echelons and linked with the choices one made in life as much as the vicissitudes of Lady Fortune. This theme was in many didactic prints, including series on the cycle of virtues and vicissitudes by printmakers such as Jacques de Gheyn and Hendrick Goltzius. Like fortune, love is slippery. Hofrichter suggests that the Dutch proverb “to hold an eel by the tail” (een aal bij de staart hebben) is about the fleeting nature of things, and she notes an earlier French emblem relating the eel’s slipperiness to fickleness and infidelity. The proverb “oh how bad he has it” (Och hoe slecht ghy’t) in Roemer Visscher’s Sinnepoppen shows an eel sliding through hands, the accompanying rhyme warning about fleeting fortune.22 Von Bogendorf-Rupperath connects the boy holding the eel and kitten to the proverb “Hij is zo glad als een aal” (he is as slippery as an eel), signifying that, like an eel, no one can hold onto him (Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, p. 202). Like eels, kittens are difficult to hold onto and liable to scratch. Proverbs such as “a cat that sits held tight makes strange jumps” (een kat, die in de benauwdheid zit, maakt rare sprongen) and “he who plays with the kitten gets scratched” (die met het katje speelt wordt er af gekrabd) suggest that mischief will result in pain: an animal in bad circumstances will do whatever it needs to do to get free (Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, pp. 200, 202, 292). Cats had connotations with lust, temptation, and pain, while eels were often described by moralizing poets as analogs for the transient nature of love, along with their phallic shape. The girl with the feminized pussycat and the boy with the phallic eel further underscored the naughtily gendered joke.

Readings about the uncertainties of love and fortune would have been apparent to Leyster’s market demographic, burgers steeped in moralizing texts. Furthermore, by pairing the animals with a boy and girl, the children play as models for future adults. Will they make moral, rational choices? Will they grow up to be moral parents? If children needed to be taught morality, pictures such as Leyster’s asked elite viewers to consider human children’s need for moral education to be distinct from animals—to be able to make the rational, moral decisions necessary to retain fortune. Children without the proper training might be unpredictable, uncontrolled, and grow up uncultivated and materially and spiritually impoverished.

These children do not seem aware of all this good advice; it is yet to be determined how their fates will play out. Children were sometimes associated with cats because of their believed shared choleric nature: to early modern viewers, children and cats were both creatures that could be easily provoked, unpredictable, shy, and mischievous. Unlike dogs, who are often emblematic of loyalty and trainability, cats were known for their untrainable characters.23 But, in the Aristotelian schema, neither cats nor dogs could be moral. Children, however, could be trained to lead moral lives. Children were thought to be like blank canvases on which good or evil could be imprinted, and thus required education (Franits 1993, p. 140; Roodenburg 2004, pp. 14–16). Parenting advice books frequently compared children to untrained animals. Jacob Cats wrote that unlearned children were “innocent beasts”, and youthful misbehavior was due to poor upbringing (Dekker et al. 2001, p. 55). Cats and others sought to instill positive adult examples rather than allow mischief from “cat wickedness” (kattekwaad). An early Anglo-Saxon school book asked children why they should want to learn, providing the response, “Because we do not want to be like beasts, who know nothing but grass and water”.24 Even promulgators of the new science regarded children’s activities as potentially animal-like. Historian Erica Fudge explains that Francis Bacon (1561–1626) saw two dangers in the idea of childhood: the child represents a stage of humanity that must be dismissed in order that true humanity (achieved and expressed through the gaining of knowledge and exercise of power over the natural world) can be reached, and until the child has learned to pass along information, he or she is still like a beast; he is “a distraction from the true exercise of humanity … a creature”.25

As blank slates on which to be imprinted, Cats suggested that children’s play was to model adult roles: young girls played with dolls and small things “useful in the kitchen”, while boys beat drums.26 In Pieter van Slingelandt’s painting of a nuclear family, the young girl learns from her mother as the cat relaxes nearby (Figure 4). A mother’s role included not only the practical task of physically nourishing children but also nourishing her children’s souls. Parents’, and especially mothers’, work was to instruct their children about God and personal piety and model for their daughters how to create a harmonious family life.

Figure 4.

Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt, The Carpenter’s Family, c.1665–75. Oil on panel, 42.9 × 35.4 cm. RCIN 404812. Royal Collection Trust, UK.

Mothers were responsible for children’s initial education and developing their moral character. Indeed, the woman’s role as wife and mother cultivating her children was analogous to a gardener cultivating fruit to bloom, a metaphor frequently used in the young Republic.27 Jacob Cats capitalized on this theme in his advice to women. In Houwelyk (Marriage), he writes that the mother must

- Cultivate the infertile land so that it can bear fruit,

- Dig, uproot, make trenches,

- Pull out the weeds, from the very first day,

- So that your esteemed husband can sow there afterwards.28

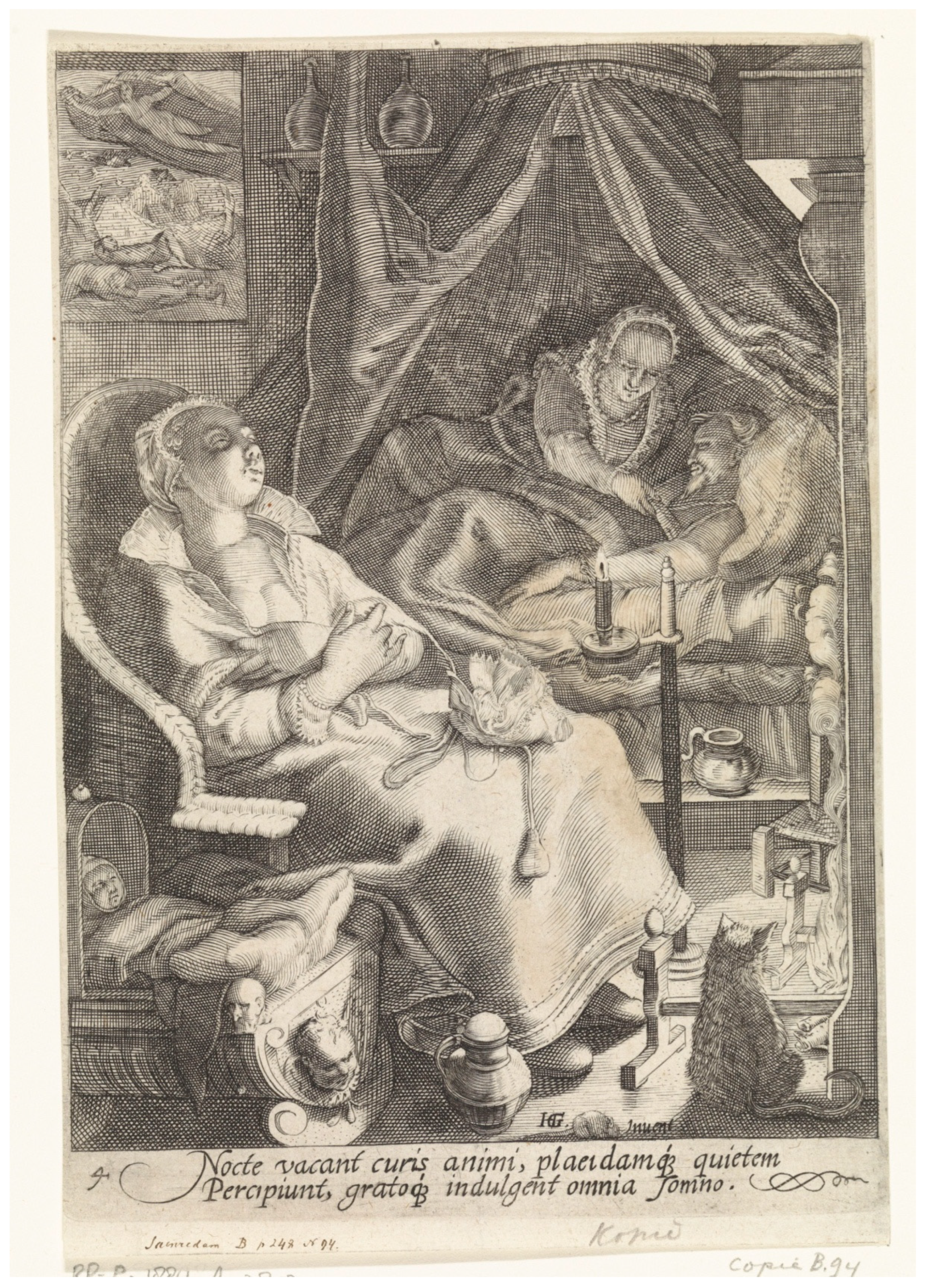

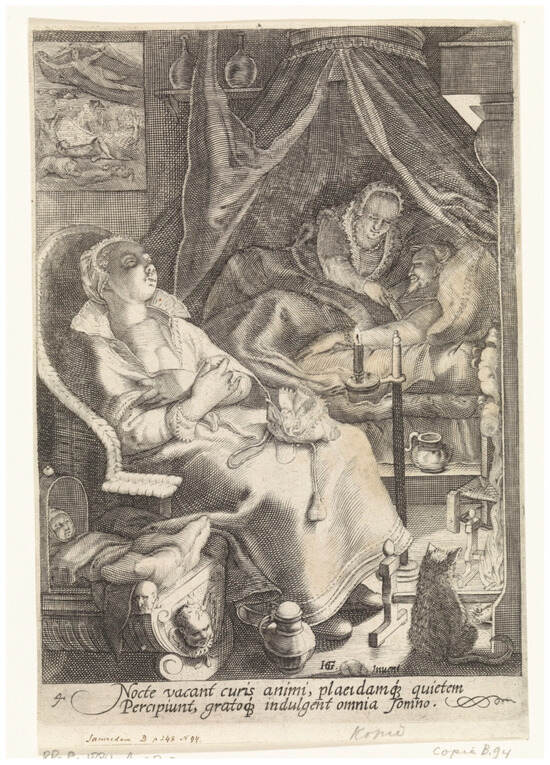

In the Netherlands, what had been an iconographic tradition of the Madonna lactans in Catholic countries became a secularized version of the virtuous mother in some Dutch paintings and prints; images such as Slingelandt’s, with the example of the nursing, fertile mother, are similar to those by fijnschilder Gerard Dou and correspond to earlier didactic print series by Haarlem artists such as Jacques de Gheyn, Jan Saenredam, and Hendrick Goltzius.29 Images such as these evoked the role of mothers to raise and nurture—to cultivate—children into moral, well-heeled Dutch citizens (Franits 1993, pp. 112–16). As in Slingelandt’s scene with the placid cat, in the night scene from Goltzius’ Times of Day series, a cat looks on as the mother rocks an infant to sleep30 (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Jan Saenredam, after Hendrick Goltzius, “Night” from the series Four Times of Day: “At night they are free from cares of the mind; they feel a peaceful quiet and all give themselves to pleasing sleep”. 1590. Engraving. RP-P-1884-A-7897.

In contrast to these model images of motherly duties and family life with the calm kitten, neither child in Leyster’s A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel seems to be doing as they should. Von Bogendorf-Rupprath suggests that the boy, like the cat and eel, seems particularly uncontrollable and unteachable (Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, p. 202). Significantly, it is the girl who points to bad behavior, even while she pulls the cat’s tail.31

Her pointed finger questions. What would happen to the children without moral instruction? For Leyster and her clients, constructing the difference between moral and immoral, those with rationality and those without, allowed them to order and make sense of their society. A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel does not portray a good example of moral, controlled comportment, but the children also may yet be taught. There are no parents in the picture, only children who play with two animals, the very animals that connote the slipperiness of fortune, animals that peasants bludgeoned at festivals. The picture asks, what have these children been taught? Who will give them culture? Will they be a good mother and father themselves, upright citizens, or will they succumb to temptations like lust, gambling, and hurting animals? Leyster engages viewers to create their own moral narrative and conclusions.

The pictorial subject of children playing with animals thus had many possible messages, with a common theme of how middle-class and elite children ought to be morally educated. Prints and paintings of the subject were useful for reinforcing parental awareness and status to a visually astute merchant class. Jeroen Dekker suggests that “[i]t was not good government but good education, not the good Prince but the good mother and father, not the good citizen, but the good child, that was placed in the center of Dutch genre painting. In sum: it was about moral teaching and about moral learning” (Dekker 2009, p. 182; more broadly, see Bourdieu 1984).

4. Instrumentalizing Cats and Eels

Asserting one’s moral superiority allowed humans to distinguish themselves from animals (and peasants, people of color, women) and rationalize using them. Seventeenth-century Dutch connotations for cats and eels must have first come from daily interactions with animals. Cats were useful and integrated into households. They were (and still are) used to hunt rats and mice, and they were pets with whom children played. Rembrandt’s heartwarming domestic scenes in oil (1646) and engraving (1654) of the Holy Family with a cat are beloved examples, as Susan Kuretsky has shown (Kuretsky 2011a). Here, the cat is a mouser, a trap for sin, and analogous to a good mother who protects and cares for her young.32

Cats could have positive associations because of their care for kittens, keen eyesight, and cunning.33 Kuretsky notes that Edward Topsell (who used much of Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium to print his own three-volume work from 1607) marked the cat’s contradictions: it was admired for its cleanliness, cunning vermin hunting, and devotion to kittens, and yet it was also seen as a carrier of pestilence.34 Cats could be viewed with suspicion because of their “lustful connection to witches” and association as familiars (Kuretsky 2011b, p. 266). There are numerous examples of Netherlandish still lifes where the cat is getting into the fish or oysters—demonstrating their association with temptation and lust—and alternatively, those that show the calm cat as emblematic of a virtuous family, as we have seen (see also Franits 1993, pp. 116–17).

As with the contradictions endemic to cat iconography, eels (paling or aal) were symbolically ambivalent in Dutch society. They are creatures both slimy and reviled while also sought after for their taste and expense. Furthermore, no one understood where eels came from or how they reproduced, and so eels, like the nocturnal cat, held an aura of the mysterious, even occult.35 It seemed they could not be tamed by science.

Dutch physician Johan van Beverwijk (1594–1647) had little to say about cats in the Schat der gesontheyt (Treasury of health, 1636) but described the eel’s taste (good, but fatty) and texture (slippery), clarifying how they were best cooked (roasted with wine or stewed with spices) and that holding them could stop a woman’s cycle (loop der vrouwen tegen [sic]).36 Jacob Cats mentioned eels mostly as a means of analogic moralizing; he described the eels’ slipperiness coming out of the pool as a parallel to the slipperiness of courtship, for example.37

The eel in Leyster’s picture seems to be a young eel, an elver, just past the “glass eel”, or transparent larval, stage. We now know that glass eels approach the European coast from having been born in the Sargasso Sea. They enter fresh water, and in the brackish habitat of Dutch estuaries, the young glass eels grow into elvers, about three to five inches long. The elvers and adult eels are fished and eaten across the North Atlantic coasts in Europe and America. When they are fully grown, adult eels return to the Sargasso Sea to spawn and die, although no one knew this aspect of their life cycle until the twentieth century.

Eels were (and still are) enjoyed as food, often smoked, salted, or stewed. Typically, fresh fish was food for the upper classes; quick preservation, such as smoking and salting, allowed a wider range of classes to benefit from the high fat and calories of local fish such as eel. Dutch fishermen responded to the demand for fresh eel among the upper classes, both at home and abroad, by selling directly from their vessels at times, while a fishwife could sell at the specialized markets in town. Amsterdam had been an important center for the eel trade since the late Middle Ages because of its location between salt and fresh water. The Dutch traded salted eels to England from the fourteenth century, and in the fifteenth century, fishermen began to trade in live eels, straight from their schuyts in the Thames River. In Amsterdam, the eel market was part of the central fish market on Dam Square.38 The eel market in Amsterdam was, in fact, an upper-middle-class enterprise run largely by women. Historian Danielle van den Heuvel has shown that the Amsterdam eel market was highly specialized and, with its close ties to the fish sellers’ guild, was probably the most prominent and most profitable of all fish markets in the city. The situation in the eel market was different not only from those in other fish markets in Amsterdam but also from those in other Dutch towns at that time: that is, in the eel trade, women had a position independent of their husbands, held very long careers in which they combined motherhood with a business, and likely were able to make more than a decent living (Van den Heuvel 2012, p. 592).

Interestingly, then, eels, like cats, had connections to women’s roles. While cats were revered for their hunting and mothering, eels were connected to women with economic power and were a rich source of energy for those who could afford them. While it is difficult to know whether Leyster made this connection, women, cats, and eels clearly had poorly understood powers that could be threatening to a patriarchal anthropocentric elite. Rationalizing hierarchies in a schema of seemingly apparent “nature” necessarily condoned violence to keep that order. In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek used eels to show the circulation of blood under his eel microscope (aalkijker). Like cats and dogs, who were used benignly as playthings or, more harmfully, as victims of vivisection, eels, too, were instrumentalized in humans’ entertainment and pursuit of scientific knowledge.

5. Objects to Subjects

Depictions of animals have served, as Jacques Derrida famously observed, to mirror back at humans the illusion of human superiority and difference (Derrida 2002). Animals held—and still hold—an in-between place in human society because of humans’ othering of them, despite our obvious connection to them: we share observable feelings, such as fear, pain, and affection. Such is the case with any Other: the more one can see oneself as distinct from and not entangled with or similar to, the easier it is to objectify, to use, to subordinate, and, potentially, to hurt. Children were believed to be like animals, sensate, yet able to develop moral rationality. Animals and children together in paintings prompted such comparisons. Thus, both beings with ambiguous statuses allowed them to be place-holders—objects onto which adult humans could project their ambivalence around class, status, and other social constructions while still seeming to reinforce the categories that undergirded the status quo.

As humans recognize the arbitrary and constructed nature of these boundaries, cruelty to animals and children and others becomes untenable. Substitutions could be made, though, to maintain hierarchies, even while some humans slowly moved to affirm the subjectivity of others. Folk historian Marjolein Efting Dijkstra describes how baiting games were so popular in the Netherlands throughout the early modern period that they persist today, although now revelers use animal substitutions. Records suggest that, as early as 1600, some towns outlawed goose pulling and cockfighting, but not out of concern for the animals’ well-being. Rather, like the visual and literary culture discussed above, such proscriptions sought to decrease the human inebriation and impropriety that went along with such cruel revelry. This was generally the case in anti-cruelty or animal protection legislation: the rationale was to control the unruly activities of the poor who consumed such entertainment and were potentially influenced by it, rather than considering the welfare of the animal. The proscriptions that accompanied wider social changes regarding human relations with domestic animals, especially pets such as cats, led to cat clubbing disappearing in many villages. Dijkstra relates how, in 1868, the Bennebroek mayor denied the permit application for cat clubbing, allowing the game only if a ball would replace the animal. She notes that beginning in the late eighteenth century, individuals substituted a ball for a cat in a barrel in some places. In other towns, especially in North Holland, the game is played with stuffed toy cats, other toy animals, or wooden blocks (Dijkstra 2004, p. 183).

As in the seventeenth century, in the nineteenth century, eel pulling was especially popular among the Dutch working classes. In 1886, the Netherlands enacted its first animal cruelty laws, making the maltreatment of non-human animals a crime; because the maltreatment of animals was regarded as an offense against public morality, public cruelty toward animals was penalized more heavily. Such laws corresponded with the rise of anti-cruelty groups in Europe and the United States in the latter half of the nineteenth century that corresponded with anti-vivisection movements, child welfare groups, and abolition work.

In the same year that the Netherlands’ first anti-cruelty law was passed (1886), eel pulling in the Jordaan neighborhood of Amsterdam caused a riot. An impromptu winter game across a canal was stopped by a policeman. Since whoever pulled down an eel, or part of it, could keep the eel to eat and potentially win as much as six guilders, this was a game with real stakes. At the time, workers in Amsterdam were suffering from high unemployment and an especially cold winter. They proceeded to protest their conditions by ripping cobbles from the road, making barricades, and fighting the authorities. This uprising was only a little about eel pulling; the animal, rather, was the object for a subjugated class to release frustration at their own subjugation and to potentially attain much-needed food. The army ended up quelling the workers’ revolt after three days, twenty-six deaths, and over one hundred injuries. This story indicates how two hundred years after Leyster’s picture, dominant sentiments toward animals and laborers continued to be fraught with hierarchical social class values that placed some humans in a lower status and how animals, in turn, were used by the ruling class as objects for moralizing against the behaviors of the lower classes.

In fact, nineteenth-century bourgeois prescriptions surrounding social comportment, much like those of the seventeenth-century Dutch, suggested teaching children kindness toward animals so that they could learn to treat other social inferiors (such as slaves or servants) kindly as well. Moralists saw animals as a way to teach children positive traits, although in this later case, not by comparing children to animals but rather by instilling positive traits in the child. As in the seventeenth century, outright violent cruelty was a sign of a person’s lack of control of passions. The increasing popularity of pet-keeping in the nineteenth century was partly fueled by a desire by bourgeois families to teach children middle-class virtues such as kindness and self-control, as much as it was also to distinguish the bourgeoisie. Kathleen Kete, in line with Bourdieu’s ideas about distinction, described the concomitant rise of pet-keeping with the formation of the bourgeoisie in nineteenth-century Paris, suggesting that “it was the realm of the aesthetic…that largely shaped class, and that the unexpectedly esoteric realm of the ordinary is the place where we should begin our search for the bourgeoisie” (Kete 1994, p. 4).

Today, animals continue to hold their ambiguous position with respect to human morality and ethics and serve as a touchstone for human ethical conduct. Many humans continue to instrumentalize animals, rarely asking Montaigne’s question of their companions, or their food. Othering allows subjects to become objects. If we humans are moral animals, how do we show care for one another? How should we care for other animals? What does care look like? What if we treat humans and animals well by identifying our duties to each other and our individual subjectivities and ways of being in the world? Feminist scholars, particularly care ethicists, have made these relationships explicit in the last twenty-some years (see especially Noddings 2013; Gruen 2015; Gilligan 1982). Carol Adams has shown the intersectional nature of misogyny, racism, and animal cruelty; that animal cruelty, particularly images of animals as Other, often depends on societal notions of masculine superiority and feminine, racialized, availability and objectification. She has suggested that “cultural theory must include consideration about species hierarchies and attitudes when examining racial and sexual representations. Otherwise it is impoverished” (Adams 2014, p. 210).

Intersectionality recognizes the interconnected nature of human—and, more frequently, human and non-human—power relations based on various categories and attributes. When human animals understand how we are interconnected to all beings, we understand our entanglement and an imperative to care: we are better able to act with empathy and compassion and reject human-constructed hierarchical systems that pictures like Leyster’s A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel reveal. Leyster constructed an elusive interpretive framework as slippery as the kitten and eel she depicted. The painting still intrigues viewers because of the layered and complex questions it raises. While the answers to those questions may have been different in the seventeenth century, the picture still raises moral questions about the relation between humans and non-human animals and our imperative to care for each other. Today, we may have different answers, because our premises rest on different ideas about the relations between humans and between human animals and non-human animals. Yet, the elision and slipperiness of these constructed categories—the contradictions signaled by the animals’ iconography and the playful questioning prompted by the children—remain.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Laura Gelfand for her insights and encouragement on this essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Hofrichter suggested that the eel is a slow-worm, which was also a plaything for Dutch children. Cynthia von Bogendorf-Rupprath writes that it may be a kat aal, the small eel not worth eating and given to the cat (Hofrichter 1989, p. 64n3; Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, p. 200). |

| 2 | The raised finger is a gesture discussed by both Leon Battista Alberti in the Art of Painting and, later, Karel van Mander in Het Schilderboeck as a way to direct the viewer’s attention to the important message of the painting. Both Leyster and Molenaer, as trained painters, must have been aware of this convention (Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, p. 290). |

| 3 | See Pugliese (2016) on the othering of animals as similar to the othering of the irrational or mad and the correspondent othering of women, Africans, and children. |

| 4 | An “old print” of cat clubbing is pictured in (Ter Gouw 1871, p. 351). |

| 5 | (Foucault 1973; Bourdieu 1984; Adams 2016). For a careful study of Foucault’s theory of epistemes in relation to animals, see especially (Chebili 2016). |

| 6 | Mackintosh on executions and baiting games as both part of Absolutist Europe (Mackintosh 2016). See also (Derrida 2011–2017). |

| 7 | As Susan James suggests, passions and rationality, the mind and body, were not so separated in seventeenth-century philosophy, literature, and art. Philosophers understood passions as part of the human being, God-given, and so relevant to moral decision-making and action; for Neo-Stoics such as Lipsius, this meant control. Suffice it to say, the discussion surrounding the interplay of morality, virtue, and ethics with rationality and emotions (passions) was not simply separating into binaries of rational/emotion, male/female, etc., nor is it today (James 1997). |

| 8 | Darnton details widespread torture of cats throughout France, England, and Germany from the 14th to 18th centuries. Cats were killed in bonfires and on poles, ritually tried and murdered, and clubbed to death. He describes reasons why cats were so used, linking them to the trials and debauched music of Carnival and superstitious practices surrounding witches, as well as symbolism related to sex. See (Darnton 1984, pp. 83–101). See also (Fudge 2006) and (Mackintosh 2016) on baiting games in early modernity. |

| 9 | (Deleuze and Guattari 2014, pp. 163–199). See also (Nagel and Wood 2010) and (Moxey 2013). Each explains this process of making meaning with art over time. |

| 10 | Papy connects Lipsius’ love of his dogs, described in a letter written on Saphyrus’ death, to the humanist tradition; similarly, Huygens’ epitaph for Geckie (Dit is mijn hondjes graf/Ik zeg er niet meer af/dan dat ik wenste (en de weer’ld was niet bedorven),/dat mijn klein Gekkie leefde en alle grote storven) suggests Huygens’ fondness for his dog and his awareness of classical precedents. Papy (1999). For Huygen’s epitaph, “Grafschrift voor mijn hondje Geckie” (Hofwijk, 25 October 1682), |

| 11 | I have written on this process in relation to images of Africans in the Dutch Republic. See (Sutton 2012, pp. 100–17, 124–49, 209, 229). See also (Chebili 2016). |

| 12 | Carroll discusses animal combat scenes in early modern Netherlandish painting to elucidate contemporary discussions of who had a right to violence and the connection between human and animal violence (Carroll 2007, pp. 161–69, 184). |

| 13 | The other signed work is a page from her 1643 Tulip Book. Hofrichter, Judith Leyster, 63–64. It probably is not her children here. She bore two boys in 1637 and 1639 and two girls in 1643 and 1646 (Broersen 1993, p. 23). |

| 14 | By 1650, Leyster and Molenaer had three houses, paying a total of 23,900 guilders, 7133 of which was mortgaged. Still, they remained financially comfortable. The houses cost them in mortgage interest, but they also received rental income from an inherited house (Broersen 1993, pp. 26–29). |

| 15 | See Ufer on the formation of four ideal categories that operated to define Dutch society: burger, boer, hovenier, and pronkert (Ufer 2010). |

| 16 | For more on Leyster’s market, see Wijsenbeek-Olthuis and Noordegraaf (1993, pp. 48–49). Cardinale suggests that Leyster’s works do not fit neatly into either the portrait or genre scene category and thereby defied the bounds of academic painting hierarchy, also, then, helping Leyster to create a new niche for herself outside of gendered expectations. Cardinale (2020, pp. 19–20). |

| 17 | (Dijkstra 2004, pp. 169–88; Ter Gouw 1871, pp. 350–51). On cat clubbing in this picture, see also (Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, p. 200). |

| 18 | Although Calvinist officials disapproved of celebrating Vastenavond (Shrove Tuesday), Von Bogendorf-Rupprath suggests that because Haarlem was home to so many Flemish immigrants (including Leyster’s father), such revelry was common. Numerous prints and paintings reveal how popular it remained in the North, even while disapproved of by preachers (Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, p. 139). |

| 19 | Darnton relates the event of apprentices and journeymen in a print workshop in Paris massacring their master and mistress’s cats, particularly the beloved gray cat of the mistress. He relates long-standing European traditions of cat torture and explains how this particular event was a mechanism by which the laborers could demonstrate, via the torture of an animal less powerful, how much they hated their master and mistress. “They found a way to turn the tables on the bourgeois. By goading him [the master] with cat calls, they provoked him to authorize the massacre of cats, then they used the massacre to put him symbolically on trial for unjust management of the shop. They also used it as a witch hunt, which provided an excuse to kill his wife’s familiar and to insinuate that she herself was the witch. Finally they transformed it into a charivari, which served as a means to insult her sexually while mocking him as a cuckold” (Darnton 1984, p. 100). |

| 20 | See (Franits 1993, pp. 5–6; Dekker 2008, p. 137; Roodenburg 2004, p. 45). Roodenburg notes that the Dutch never adopted the term civility as such; it was translated from Erasmus’ De Civilitate as Van de borgerlycke wellevendheide der kinderlycke zeden, for example. |

| 21 | Franits notes how mothers especially were necessary in cultivating virtue in children, and dogs and cats in familial scenes could signal correct or incorrect elite family mores; in Crispijn van de Passe’s print of Discordia, animals tug at the fighting couple’s clothes and maul the food, while in Concordia, the family at the table together, the dog trained, and the cat calmly looking on (Franits 1993, pp. 116–17); On dogs and the Lycurgus tradition, 148–156. |

| 22 | (Hofrichter 1989, p. 64). From Sinnepoppen: “ALS een mensch soo verre komt, dat hy op’t vriendelijck willekoom heeten, handt, douwen, omhelsen van zijn Landtsheere; of op jonste, en juyghen van het ghemeene, volck hem verlaet, ja of vertrout, die is verre uyt zijn coursse, om te gheraken tot een ghewenschte Haven van ruste, en eyligheydt. Ende heeft het immer* soo slecht, of hy een gladde Paling by de steert ghevat hadde: want eeren jonste ende Volcks trouwe, staen soo vast ende onbeweghelijck, als de Weerhaen op de Kercks toren” (Visscher 1949, p. 176). |

| 23 | Von Bogendorf-Rupprath notes that in contemporary Dutch emblemata, the cat represented unteachability (hardleersheid) or fickleness (onverantwoordelykheid) (Von Bogendorf-Rupprath 1993, p. 203n14). |

| 24 | Quoted from Leah Sinangou Marcus in Fudge (1999, pp. 102–3). |

| 25 | (Fudge 1999, pp. 104–5). In the seventeenth century, adherents to the new science, such as Francis Bacon, synthesized, rejected, or amended these ideas; Descartes considered animals as machines, with no feeling, incapable of language (we know this now not to be true). Not all thought this way, however: John Locke argued that animals do have feelings and can feel pain, although, for Locke, cruelty to animals was unethical because it engendered cruelty in humans. |

| 26 | See, for example, (Barnes and Rose 2012, p. x). See also Franits (1993, pp. 132–34). |

| 27 | There is a long tradition of allegorizing the maid tending her garden to the Republic, as in Willem Buytewech’s 1615 print of the “Allegory of the Deceitfulness of Spain”. Roodenburg (2004, pp. 14–15). |

| 28 | “moet het rouwe lant als totte vrucht bereyden/Bespitten open doen, met greppen onderscheyden,/Het onkruyt roeyen uyt, oock vanden eersten dach,/Op dat u weerde man daer namaels saeyen mach”. (Cats 1625). English from Franits (1993, p. 129, 232n72). |

| 29 | In the print of Morning from a series demonstrating appropriate familial activities for times of day by Jan Saenredam (1565–1607) after Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617), Goltzius underscores the mother’s role as cultivator of morally upright citizens of the new Protestant Republic by showing the mother feeding her children breakfast at a pause from sewing, while the father and elder son read together. |

| 30 | Unsurprisingly, cats were associated with sleep, and a peaceful night’s rest is what the couplet below suggests for the calm family: “At night they are free from cares of the mind; they feel a peaceful quiet and all give themselves to pleasing sleep”. Thanks to Jonathan Sutton for the translation from Latin. |

| 31 | Nicole Cook has shared with me how this picture also seems to fall into a pattern in Leyster’s work, where the female warns of/has the agency to stop/points out the bad behavior of the male. Personal correspondence. |

| 32 | As Kuretsky points out, because of their association with sin entering the world through temptation and their ability to withstand serpent poison, cats were sometimes included near Eve in images of the Temptation and Fall of Adam and Eve, or in images of lovesick or dissolute women, in addition to representations as the “female Nativity cat” who traps a mouse, as the Incarnation of Christ traps the Devil. Kuretsky (2011b, pp. 266–68). |

| 33 | A cat is foregrounded in Jan Saenredam’s 1616 print of Allegory of Perception, after Goltzius, and also appears in prints allegorizing winter. |

| 34 | Topsell remarks on their keen eyesight and glowing eyes, as well as their soft fur and scratchy tongues used for cleaning; for these reasons, painters and printmakers sometimes depicted the cat to highlight the senses of Taste, Sight, and Touch (Topsell 1967, pp. 81–83; Kuretsky 2011b, p. 266). |

| 35 | Little was known about the migration and reproductive habits of eels in the seventeenth century, and it remained mysterious for scientists even into the twentieth century. Today, European and North American eels are endangered because of human-made dams, pumps, and dikes, in addition to water pollution and overfishing. Asian markets for glass eels have also contributed to eel decline (Hennop 2013). |

| 36 | Ael en Palingh sijn wel lieffelijk en aengenaem van smaeck, maer vol van taeyen glat vet; waerom sy oock naeuwelijcks in de handen konnen gehouden werden, sonder te ontglijden, waer van het spreeck woort komt: Een gladden ael by de staert te hebben. Geven geen van beyden goet voedsel, en sijn den siecken noch den gesonden goet om te eten insonderheyt wat veel. Dan alderquaetst sijnse voor de gene, die een quade maegh hebben, en die met gicht ofte steen gequelt sijn. Oock houdense den loop der vrouwen tegen. Sy sijn beter gebraden of met wijn en specerijen gestooft, dan ghesoden, om dat daer door haer overtollige slijmerigheyt verbetert werdt. Beverwijk, Schat der Gesontheyt, (Amsterdam: Schipper, 1636), 134. |

| 37 | Eertijts was ick wel ghesien/Als ick u maer aen quam bien/Soo wat eleyns, eens Herders-gift,/Versche kees van room gheschist/Off een geele kees-roffoel,/Off een palingh uytte poel,/Off een scherp-ghetande snouck./Off wat mossels van Dijshouck; Cats, Maechden-plicht, ofte ampt der ionkvrouwen…, (Beverwijk 1636, p. 99). Both Beverwijk and Cats probably knew Conrad Gessner’s Historia Animalium, which was the most comprehensive source on animals. The Animalium consisted of four volumes printed between 1551 and 1558 (volume I on viviparous animals in 1551; volume II on oviparous animals in 1554; volume III on birds in 1555; and volume IV on fish and other aquatic animals in 1558). Condensed descriptions with woodcuts were also published by Christoph Froschauer as the Icones Animalium and Icones Avium in 1553 and 1555. These much-abridged vernacular editions were more accessible in language, size, and price. As Egmund notes, the German versions—the Vogelbuch (1557), Thierbuch (1563), and Fischbuch (1563)—probably enjoyed the widest distribution. Gessner synthesized information about the animals from antique and contemporary sources, building from philological history to physical description to behavior. For example, in the first volume, Gessner explains cats’ names in known languages, cites the ancients from Virgil to Pliny to the Egyptians, describes their habits, and warns against sleeping with them for health reasons. In the fourth volume on fishes, he similarly discusses the Anguilla or eel, explaining its historical philology, physical description, and known behavior. See also (Egmond 2013, p. 151; Gessner 1551–1558, vol. 1, pp. 345–48). On eels, 46–47. |

| 38 | Van den Heuvel documents “twenty-three stalls available for eel sellers, each of which could be shared by two stallholders. Most of these stalls were rented by women, … This was very different from saltwater-fish markets in the city at that time: evidence shows that in these markets all stalls were let to women”. Van den Heuvel (2012, p. 589). |

References

- Adams, Carol. 2014. Why a Pig? A Reclining Nude Reveals the Intersections of Race, Sex, Slavery, and Species. In Ecofeminism: Feminist Intersections with Other Animals and Earth. Edited by Carol Adams and Lori Gruen. New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 206–24. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Carol. 2016. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Alpers, Svetlana. 1975–1976. Realism as a Comic Mode: Low-Life Painting Seen through Bredero’s Eyes. Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 8: 115–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Donna, and Peter Rose. 2012. Childhood Pleasures: Dutch Children in the Seventeenth Century. New York: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beverwijk, Johannes. 1636. Schat der Gesontheyt. Dordrecht, Hendrick van Esch. Available online: https://archive.org/details/schatdergesonthe00beve (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bredero, Gerbrand Adriaensz. 1980. Boeren Geselschap. In Geestigh Liedt-Boecxken. Haarlem: Querido. First published 1621. [Google Scholar]

- Broersen, Ellen. 1993. ‘Judita Leystar’: A Painter of ‘Good, Keen Sense’. In Cat. Haarlem and Worcester Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and Her World. Edited by James A. Welu and Pieter Biesboer. Zwolle: Waanders, pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale, Nicole J. 2020. Judith Leyster: A Study of Extraordinary Expression. Master’s thesis, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/571 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Carroll, Margaret. 2007. Painting and Politics in Northern Europe. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cats, Jacob. 1625. Houwelick, Dat Is Het Gansche Gelegenheyt des Echten-Staets. Middelburg. Available online: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/cats001houw01_01/index.php (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Chebili, Saïd. 2016. The Order of Things: The Humans Sciences are the Event of Animality. Translated by Matthew Chrulew, and Jeffrey Bussolini. Leiden: Brill, pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Darnton, Robert. 1984. The Great Cat Massacre and other Episodes in French Cultural History. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, Jeroen J. H. 2008. Moral literacy: The pleasure of learning how to become decent adults and good parents in the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century. Paedagogica Historica 44: 137–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, Jeroen J. H. 2009. Beauty and simplicity: The power of fine art in moral teaching on education in seventeenth century Holland. Journal of Family History 34: 166–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, Jeroen, Leendert Froenendijk, and Jan Verbeckmoes. 2001. Proudly Raising Vulnerable Youngsters: The Scope for Education in the Netherlands. In Cat. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Pride and Joy: Children’s Portraits in The Netherlands 1500–1700. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 2014. What Is Philosophy? Translated by Hugh Tomlinson, and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Montaigne, Michel. 1910. An Apology for Raymond Sebond. In Essays of Montaigne. Translated by Charles Cotton. New York: Library of Liberty, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 2002. The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow). Critical Inquiry 28: 369–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrida, Jacques. 2011–2017. The Beast and the Sovereign. 2 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, Marjolein Efting. 2004. The Animal Prop: Animals as Play Objects in Dutch Folkloristic Games. Western Folklore 63: 169–88. [Google Scholar]

- Egmond, Florike. 2013. A Collection within a Collection: Rediscovered Animal Drawings from the Collections of Conrad Gessner and Felix Platter. Journal of the History of Collections 25: 149–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, Michel. 1973. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franits, Wayne. 1993. Paragons of Virtue: Women and Domesticity in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fudge, Erica. 1999. Calling Creatures by their True Names: Bacon, the New Science and the Beast in Man. In At the Borders of the Human: Beasts, Bodies, and Natural Philosophy in the Early Modern Period. Edited by Erica Fudge, Ruth Gilbert and Susan Wiseman. New York: Palgrave McMillan, pp. 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Fudge, Erica. 2006. Brutal Reasoning: Animals, Rationality, and Humanity in Early Modern England. Ithaca: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fudge, Erica, ed. 2004. Renaissance Beasts: Of Animals, Humans, and Other Wonderful Creatures. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gessner, Conrad. 1551–1558. Historia Animalium. Tiguri, vols. 1–4. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/06004347/ (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Gilligan, Carol. 1982. In a Different Voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gruen, Lori. 2015. Entangled Empathy: An Alternative Ethic for Our Relationships with Animals. New York: Lantern. [Google Scholar]

- Hennop, Jan. 2013. Dutch Fishermen Give Vanishing Eels New Lease of Life. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2013-10-dutch-fishermen-eels-lease-life.html (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Hofrichter, FrimaFox. 1989. Judith Leyster: A Woman Painter in Holland’s Golden Age. Doornspijk: Davaco. [Google Scholar]

- James, Susan. 1997. Passion and Action: The Emotions in Seventeenth-Century Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jonckheere, Koenraad. 2019. Aertsen, Rubens and the questye in early modern painting. Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art/Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek Online 68: 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kete, Kathleen. 1994. The Beast in the Boudoir: Petkeeping in Nineteenth-Century Paris. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kettering, Alison McNeil. 1983. The Dutch Arcadia: Pastoral Art and Its Audience in the Golden Age. Montclair: A. Schram. [Google Scholar]

- Kuretsky, Susan. 2011a. Rembrandt’s Cat. In Aemulatio: Imitation, Emulation, and Invention in Netherlandish Art from 1500–1800. Edited by Anton Boschloo. Zwolle: Waanders, pp. 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kuretsky, Susan. 2011b. Rembrandt’s Cat. In Aemulatio. Zwolle: Waanders, pp. 266–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh, Andrew. 2016. Foucault’s Menagerie: Cock Fighting, Bear Baiting, and the Genealogy of Human-Animal Power. In Foucault and Animals. Edited by Matthew Chrulew. Leiden: Brill, pp. 161–89. [Google Scholar]

- Moxey, Keith. 2013. Visual Time: The Image in History. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, Alexander, and Christopher Wood. 2010. Anachronic Renaissance. New York: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, Nel. 2013. Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Papy, Jan. 1999. Lipsius and His Dogs: Humanist Tradition, Iconography and Rubens’s Four Philosophers. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 62: 167–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, Joseph. 2016. Terminal Truths: Foucault’s Animals and the Mask of the Beast. In Foucault and Animals. Edited by Matthew Chrulew. Leiden: Brill, pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roodenburg, Herman. 2004. The Eloquence of the Body. Zwolle: Waanders. [Google Scholar]

- Schenkeveld, Maria. 1991. Dutch Literature in the Age of Rembrandt: Themes and Ideas. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamin. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Elizabeth. 2012. Early Modern Dutch Prints of Africa. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Gouw, Jan. 1871. De Volksvermaken. Haarlem: Erven Bohn. Available online: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/gouw002volk01_01/ (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Topsell, Edward. 1967. The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents and Insects. New York: Dover, vol. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ufer, Ulrich. 2010. Urban and Rural Articulations of an Early Modern Bourgeois Civilizing Process and Its Discontents. Articulo—Journal of Urban Research, Special Issue 3|2010. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/articulo/1583 (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Van den Heuvel, Danielle. 2012. The Multiple Identities of Early Modern Dutch Fishwives. Signs 37: 587–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nierop, Henk. 2015. The Anatomy of Society. In Cat. Boston, Class Distinctions: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer. Boston: MFA, pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Visscher, Roemer. 1949. Sinnepoppen. Edited by L. Brummel. The Hague: Willem Jansz. Available online: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/viss004sinn01_01/colofon.htm (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Von Bogendorf-Rupprath, Cynthia. 1993. Catalogue entries in: Cat. Harlem and Worcester. In Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and Her World. Edited by James A. Welu and Pieter Biesboer. Zwolle: Waanders. [Google Scholar]

- Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, Thera, and Leo Noordegraaf. 1993. Painting for a Living: The Economic Context of Judith Leyster’s Career. In Cat. Harlem and Worcester Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and Her World. Edited by James A. Welu and Pieter Biesboer. Zwolle: Waanders, pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wolloch, Nathaniel. 2000. Christiaan Huygens’s Attitude toward Animals. Journal of the History of Ideas 61: 415–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolloch, Nathaniel. 2006. Subjugated Animals: Animals and Anthropocentrism in Early Modern European Culture. Amherst: Humanity Books. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).