‘A World of Knowledge’: Rock Art, Ritual, and Indigenous Belief at Serranía De La Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon

Abstract

1. Introduction

‘There are the paintings… The great spiritual worlds are captured here…’(Ismael Sierra, a Tukano Oriental elder, at the site of Principal, 20 September 2023; translation by the authors)

‘We have to read a figure, we have to read it from inside out… If we begin to look at the figure of each image it will give us many stories, and then what appears in each image is the knowledge of each species, and that is what is handled at the shamanic level…. And that is how we begin to know the pictographs…. Because this is a world of knowledge…. I tell you each one of these figures contributed the shamanic knowledge for our own management of the territory where we are…When this knowledge comes out it appears as a wardrobe, as a shamanic wardrobe, as a guide to be able to practice shamanism. …To understand the pictographs you have to have different levels of knowledge…. One part is that you have to look at them from the shamanic viewpoint… that corresponds to the shamans… you have to have another vision which is the oral shamanism which is the one that I manage….we have to concentrate very well for it to provide us with information’.(Ulderico, a Matapí ritual specialist, at the Raudal site, 1 September 2022; translation by the authors)

2. Serranía De La Lindosa and Its Environs

3. Methods

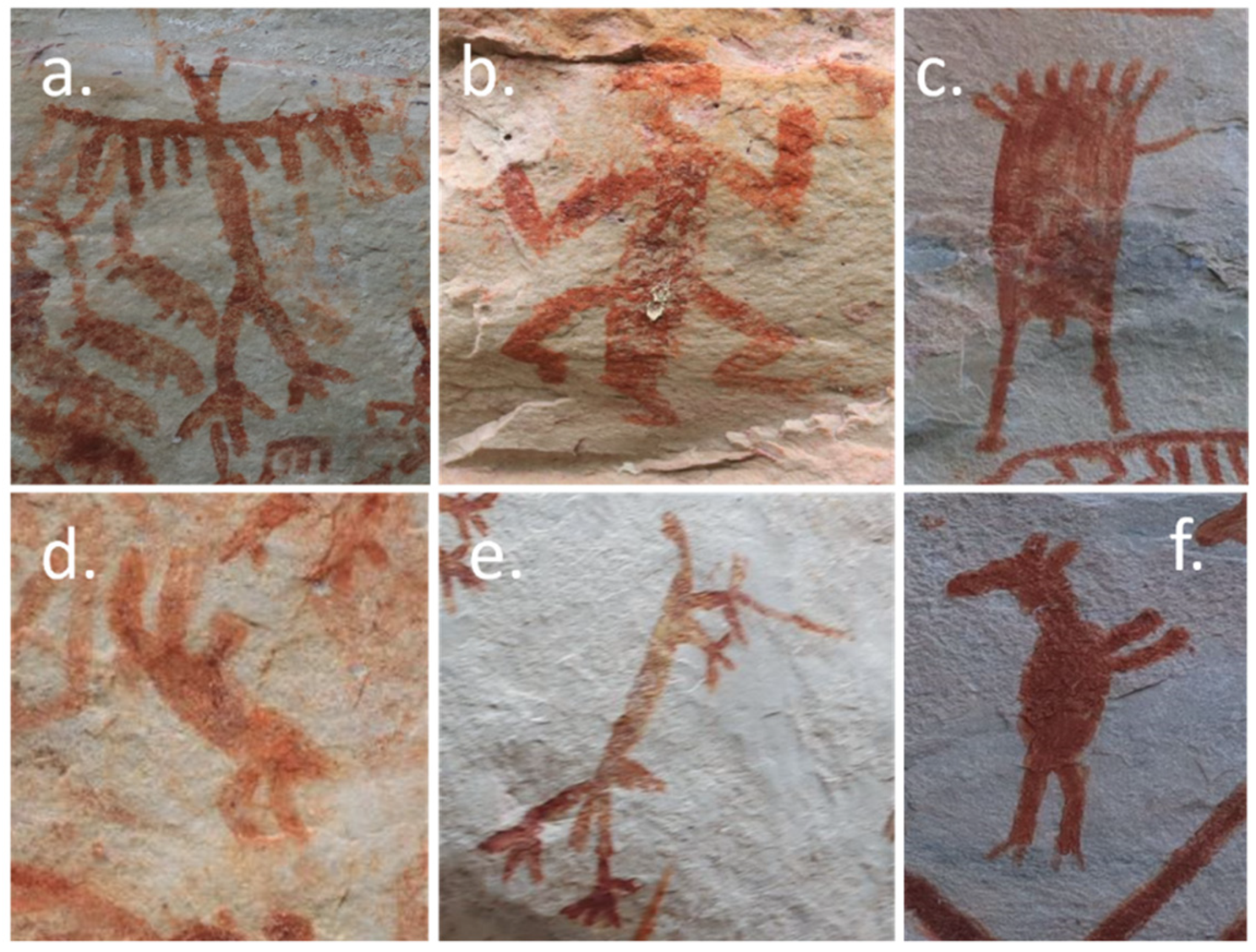

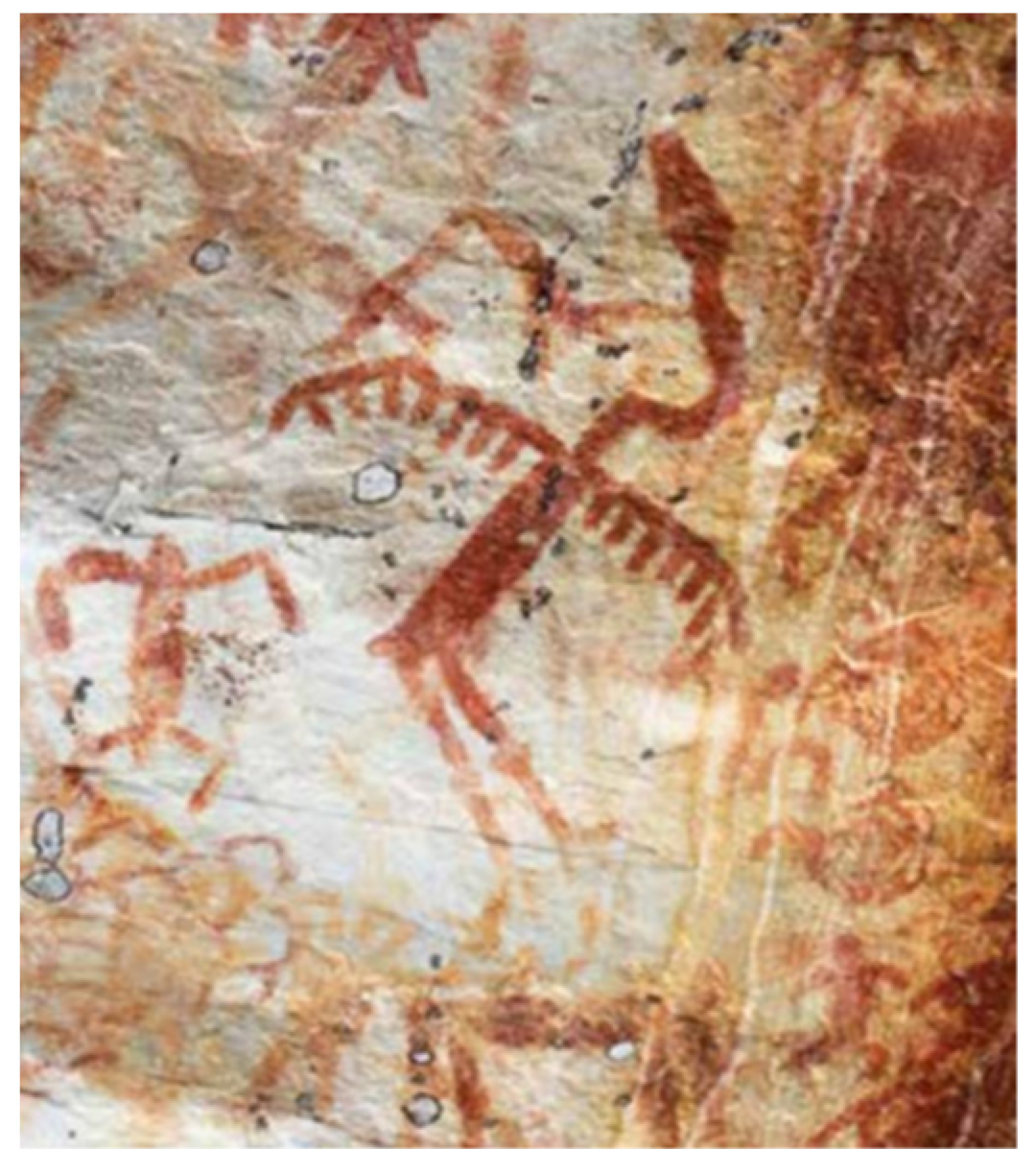

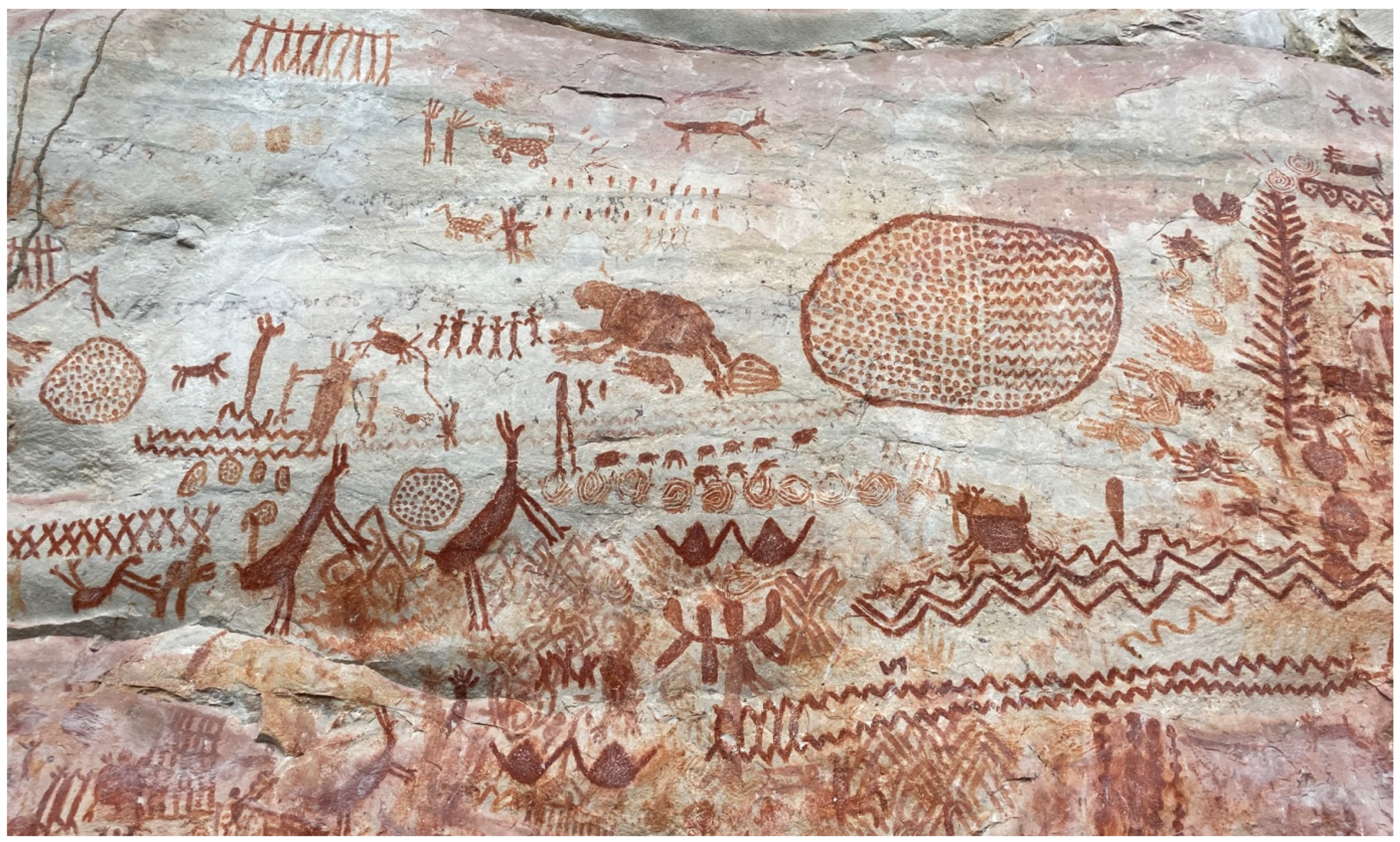

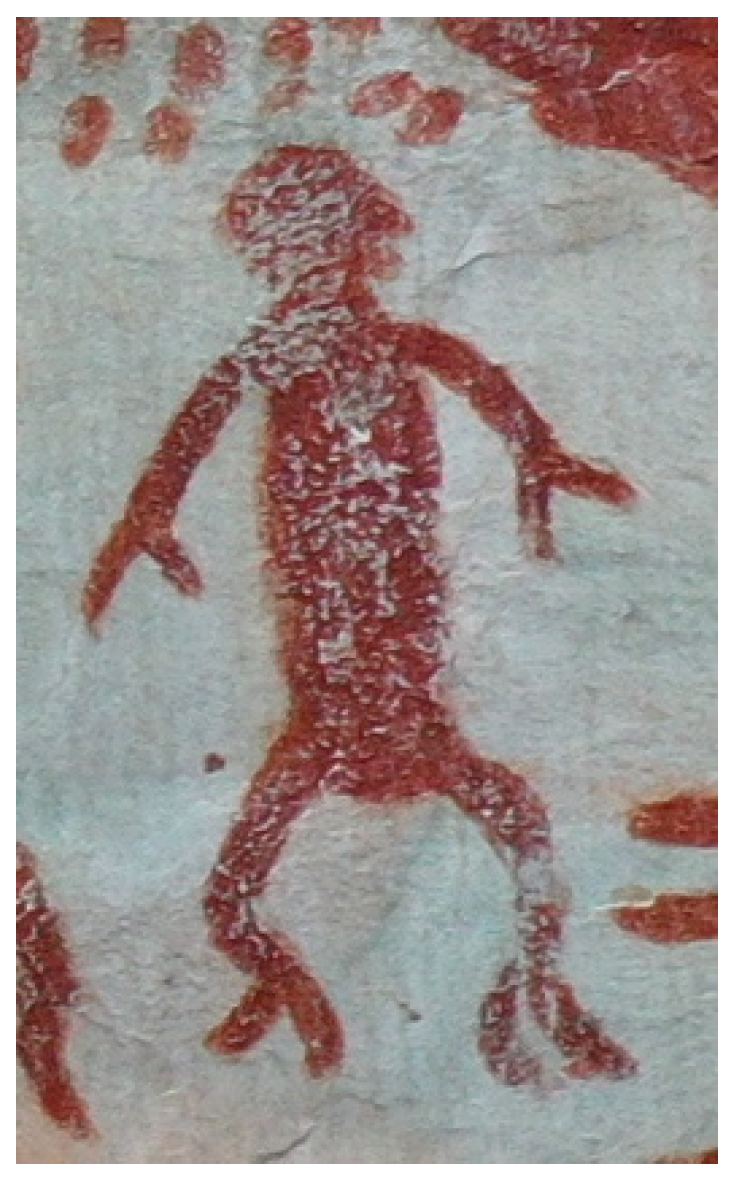

4. A Closer Look at the Rock Art of La Lindosa

5. Rock Art, Shamanism, Ethnography, and Ethnohistory at La Lindosa and Beyond

The hills in the forest are not only meeting places of one shaman and Waí-maxsè [the Master of Animals—an important figure to whom we return below] but also the locales where, in their hallucinations, various shamans of neighboring tribes celebrate their reunions. Among them and the Master of Animals a true barter unfolds during which each tries to gain advantages. It is imagined that within the uterine hills, which are like great communal houses, the animals hang from the rafters in a somnolent state, and the shaman chooses the animals which he needs for the hunters of his group. Going from rafter to rafter he shakes them, and with each shake, the animals awake and go forth into the forest. Waí-maxsè “charges per shake” and at times when more animals have been awakened than was intended and bargained for, negotiations are renewed with the Master of Animals who asks for more and more souls.

Where are we? This [gesturing to the paintings at the Principal site] is the door, this is the house and this is the wall of the tepui, one sees that it is made from stone, but for those in ancient times it was not stone, it was the wall of a house…This is a sanctuary, we are inside the tepui. The ancestors can hear us.…Each time you come, you see different things; things show themselves to you. All these rockshelters are houses.13

6. A Closer Look at Animal Motifs: Moving Beyond ‘Menus’

7. Hunting and Fishing in an Animistic World

8. Liminality, Portals, Transformation

9. Shamanism and the Master of Animals Within a Tiered Cosmos

10. Shamans and Plants

11. Moving Forward, Caring for the Paintings, and Why This Research Matters

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A25

‘When they [our ancestors] came down to Earth and arrived here… They came down from the world of the spiritual beings… they pulled half of the spiritual beings with them… And then the spirits that came down that had been torn apart … roamed the Earth like crazy, and then when they woke up they started to see a world of images, and then the whole world of images—as we see it here—was going to be the transformation of the living beings in the future world…. And then they began to concentrate,26 they sat down, and then they began to organise it…

We have to read a figure, we have to read it from inside out… If we begin to look at the figure of each image it will give us many stories, and then what appears in each image is the knowledge of each species, and that is what is handled at the shamanic level…. …. If I did not know any of these components of the figure I would not have the capacity to manage this world that is here… And after they organized it, the beginning of the second era arrives and that is where they begin to take… that is how they materialize it, that is where they give it the name, its habitat and all the shamanic knowledge that it has to manage it… And that is how we begin to know the pictographs…. Because this is a world of knowledge…. I tell you each one of these figures contributed the shamanic knowledge for our own management of the territory where we are…When this knowledge comes out it appears as a wardrobe, as a shamanic wardrobe, as a guide to be able to practice shamanism…’

‘After the fifteen days that you fast, your vision goes… You suddenly go out into the bush and all the noises prepare you as you begin to hear how the animals talk, and you no longer consider them as animals, and then when you see how everything is—let’s say the spiritual representation of each tree, of each place, of each place of respect—then you begin to be able to relate to that, and if you do not get into the vision of a shaman from beyond then you cannot interpret this, and then you cannot manage your own territory—that is what happened to my two brothers.’

| 1 | On the use of ethnographic analogy, (see Wylie 1985; Lewis-Williams 1991; Currie 2016; Whitley 2021; also, see below). |

| 2 | Unsurprisingly, each group in the Amazon has their own particular term for shaman. In this paper, we use the words payé, shaman, rezadore (‘one who prays’), and ‘ritual specialist’ interchangeably. (See also Castaño-Uribe and van der Hammen 2005). Below, we discuss the role of shamans within animistic and perspectivist frameworks. |

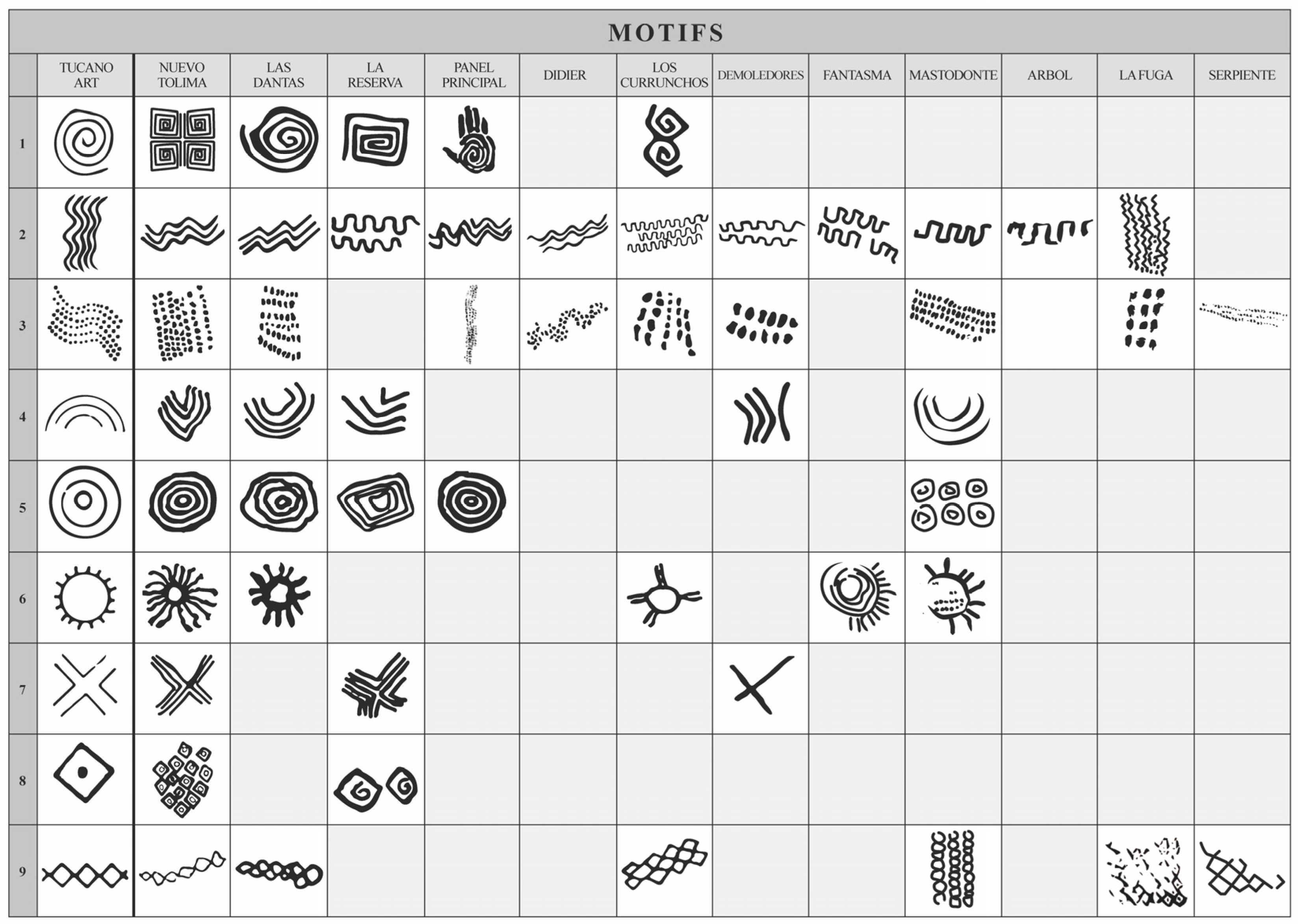

| 3 | Rock art sites in the nearby Inírida River and Chiribiquete regions contain similar motifs (Urbina 1994; Castaño-Uribe and van der Hammen 2005; van der Hammen 2006; Argüello and Martínez 2016; Castaño-Uribe 2019), suggesting a shared animistic ontology and artistic practice, albeit with distinct regional variations (see below). |

| 4 | As outlined below, although we start with etic categories here, we recognise the inherent issues of subjectivity and ambiguity within any form of categorisation and art interpretation. Classifications are of course subject to change as understanding of the artistic tradition increases, and in this article we adapt emic concepts and categories wherever possible. We also acknowledge here that, by themselves, numbers—and indeed the empiricist paradigm as a whole—do not help us establish the meanings of rock art motifs (see, e.g., Lewis-Williams 2006). |

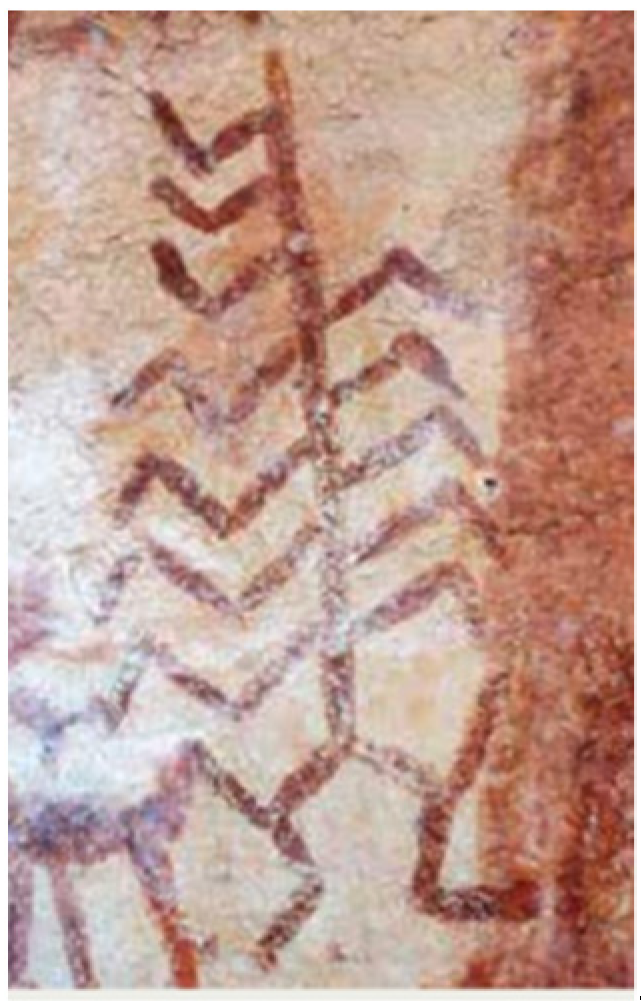

| 5 | Schematised images are primarily abstractions from a human or animal form that incorporate distinctly ‘non-realistic’ (from a Western perspective) elements. (This does not include the therianthropic merging of animal and human features, which is included under Animals—see below.) A common schematised motif, for example, is a series of vertical lines that lack defined human features, but suggest a human figure because of the addition of limb-like appendages (see Robinson et al. 2024). Geometric motifs, incorporating repeated basic shapes, are common in the region. Importantly, we know that for many Indigenous groups in the Amazon, animals are often manifested in artwork as geometric designs; zig-zags and undulating lines, for instance, often represent snakes, while a scroll design sometimes invokes a jaguar’s spots (see below; see also Iriarte et al. 2022b; Hampson, forthcoming). Importantly, we also know that geometric designs are often considered to be ‘gifts’ from animal and plant ‘donors’ (e.g., Reichel-Dolmatoff 1997). The Abstract category includes irregular non-figurative or geometric images, whereas the Unknown category encompasses images that—usually due to poor preservation—cannot be clearly identified. Future papers (e.g., Oosterwijk et al., forthcoming on handprints, and Iriarte et al., forthcoming on the relationship between dancing figures and geometrics) consider specific motifs, category by category. For a discussion of the importance of animal figures at La Lindosa, (see Robinson et al. 2024). |

| 6 | As in many parts of the world, more work needs to be done on how scenes are identified and categorised. One of us (Hampson 2019, 2024) has previously shown that what we as Western researchers identify as a ‘scene’ does not always tally with Indigenous concepts and beliefs. Similarly, researchers have usually found it extremely challenging to establish consistent definitions for ‘static’ and ‘dynamic’ motifs. |

| 7 | Reichel-Dolmatoff (1997, p. 33–34) points out that the ‘true specialists … in classificatory systems are the shamans who, because of their practical and esoteric activities, must handle enormous masses of data. To bring order into the visible and invisible universe, as conceived by the Desana, and to make all tangible and unseen phenomena amenable to manipulation and control are tasks all shamans must cope with, and the methods and aims of classificatory systems are often a matter of discussion by shamans and elders.’ |

| 8 | As Furst and Furst (1981, p. 26) made clear more than 40 years ago, for instance, Reichel-Dolmatoff ‘is one of the lamentably small handful of ethnographers who insist that the ideology and intellectual life of native peoples deserve to be taken seriously … and who recognize not just the decisive role of ideology in the regulation and organization of daily life but the functional interrelationship of mental life with the environment, whether sociocultural or natural.’ Similarly, Alberti and Bray (2009, p. 337) point out that in re-visiting the ethnographic and ethnohistorical texts of animistic groups, ‘we find indigenous accounts serving as both models for the exploration of past peoples through the archaeological record and as an intellectual resource for modelling theories about the archaeological record.’ Several anthropological rock art researchers (e.g., Lewis-Williams 2002; Whitley 2009) have been employing similar methodologies since the 1970s and 80s. For more on animism, perspectivism, and multinaturalist conceptions of the world, (see e.g., Descola 1994; Århem 1996; Viveiros de Castro 1998). |

| 9 | As we shall see below, Indigenous elders repeatedly refer to the paintings as animistic and shamanistic ‘knowledge’, in order to help manage their territory. |

| 10 | When Indigenous peoples tell us that there are such things as ‘other-than-human-persons’ (Hallowell 1960, p. 36), then ‘the anthropological exercise is not about translating the idea of nonhuman persons into concepts we already know, but rather about challenging our own assumptions about personhood so as to make it possible for us to imagine how persons in this world actually include humans and nonhumans alike.’ (Willerslev 2013, p. 42). |

| 11 | A maloca is a house modelled on the cosmological beliefs of many Indigenous groups in the Amazon (e.g., Reichel-Dolmatoff 1997); malocas are often painted with shamanistic motifs. |

| 12 | Yagé, also known as ayahuasca, is made from the hallucinogenic Banisteriopsis caapi vine. As we shall see below, entering shamanic altered states of consciousness was and is widespread in Amazonia (e.g., Reichel-Dolmatoff 1997; Langdon 2017). |

| 13 | Victor also mentioned that the Nueva Tolima rock art site was ‘another maloca’. |

| 14 | The Jiw group’s traditional lands straddle the Guaviare and Meta border. |

| 15 | As Loubser and Lewis-Williams (2014, p. 4) point out, however, ‘The current trend to deny the usefulness of ethnographies in archaeological research, whilst laudable in its critical endeavour, is often too dismissive. Valuable records of Indigenous peoples’ beliefs are today sometimes jettisoned along with what are clearly spurious or superficial accounts.’ |

| 16 | According to Whitley (2021, p. 69): ‘Earlier researchers [working with Indigenous groups in western North America] did not apprehend the ontological distinctions that made the ethnographic statements logical, consistent and informed, instead inferring that the commentary was incoherent gibberish signaling a lack of any knowledge about the art.’ |

| 17 | Tapirs ‘in real life’ have three toes on the front foot, and four on the back. Tapir paintings (e.g., Figure 4e above), on the other hand, always have two toes (on both front and back feet). Unsurprisingly, symbolic relationships between Amazonian groups and tapirs ‘develop on several different levels and use many different images’ (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1997, p. 81; see also Cabrera et al. 1999). Tapir is sometimes equated with Thunder, a powerful being who lives in the sky; in several myths, the first Desana take narcotic snuff and visit Thunder ‘by climbing up to the sky on a column of tobacco smoke’ (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1987, p. 81). Tapirs also feature in the myth concerning the origin of the hallucinogenic coca plant (e.g., Reichel-Dolmatoff 1997). For the Nukak, a person has three spirits which take different paths upon death; one of the spirits journeys to the ‘tapir’s home’ and emerges at night (Cabrera et al. 1999). Large trees also have spirits which make their way to the ‘house of the tapir’ (Cabrera et al. 1999). |

| 18 | |

| 19 | For the Barasana, if an anaconda wishes to eat birds, it simply sheds its skin and becomes an eagle—another important shamanic avatar (see below, and Hugh-Jones 1979, p. 125). |

| 20 | Moreover, as Furst and Furst (1981, p. 262) point out, the Desana ‘seek to assure continued balance between their needs and the environmental possibilities by supernatural means. Hunting is thus as much a matter of ideological determinants as of economic ones.’ |

| 21 | Lewis-Williams and Dowson (1988) famously drew much of their research on phosphenes, entoptics, and neurologically induced geometric imagery from the work of Reichel-Dolmatoff in the Amazon. |

| 22 | Several ‘dancing figures’ also have exaggerated knees, or what might possibly be dancing rattles (see Iriarte et al., forthcoming for the possible connections between dancing, geometrics, and fishing; see also Hampson, forthcoming). |

| 23 | Victor, pointing to another U-shaped geometric motif at the same panel, said: ‘This could be a shortcut, to use if your enemies are chasing you, a portal. It could also be a metaphor: if you get sick, you can use the shortcut to get healed.’ Ismael, on another visit to Principal, made it clear that ‘That’s why there has to be a main promenade that says ‘here is the door to leave the offerings’…’ |

| 24 | As Whitley (2021, p. 73) states, ritual specialists ‘were the necessary bridge upon which these relationships were established. That is, these relationships required the active participation of [ritual specialists] with the production of rock art a key performative element in their practices.’ |

| 25 | Interview recorded and transcribed on 1 September 2022. |

| 26 | Ulderico explained later that ‘to concentrate’ was akin to going into an altered state of consciousness. |

References

- Abram, David. 2010. Becoming animal. Green Letters 13: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceituno, Francisco Javier, Mark Robinson, Gaspar Morcote-Ríos, Ana María Aguirre, Jo Osborn, and José Iriarte. 2024. The peopling of Amazonia: Chrono-stratigraphic evidence from Serranía La Lindosa, Colombian Amazon. Quaternary Science Reviews 327: 108522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, Benjamin, and Tamara Bray. 2009. Animating archaeology: Of subjects, objects and alternative ontologies. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19: 337–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüello, Pedro, and Diego Martínez. 2016. Rock Art Research in Colombia. Rupestreweb. Available online: http://www.rupestreweb.info/colombia.html (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Århem, Kaj. 1996. The cosmic food web: Human–nature relatedness in the northwest Amazon. In Nature and Society: Anthropological Perspectives. Edited by Philippe Descola and Gísli Pálsson. London: Routledge, pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Baeta, Alenice, and André Prous. 2017. The history of the studies of prehistoric rock paintings in the Lagoa Santa karst. In Archaeological and Paleontological Research in Lagoa Santa: The Quest for the First Americans. Edited by Pedro Da-Gloria, Walter Neves and Mark Hubbe. Cham: Springer, pp. 319–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ballestas Rincón, Luz. 2007. La Serpiente en el Diseño Indígena Colombiano. Bogotá: Universidad Nacionald e Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamin. 2018. El Médano rock art style: Izcuña paintings and the marine hunter-gatherers of the Atacama Desert. Antiquity 92: 132–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, José. 2019. Pinturas Rupestres de la Vereda Nuevo Tolima, San José de Guaviare. Bogota: Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrão, Maria, and Martha Locks. 1993. Rock paintings of mammals at Central, Bahia, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 10: 727–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird-David, Nurit. 1999. “Animism” revisited: Personhood, environment, and relational epistemology. Current Anthropology 40: 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Sierra, Carlos, and Hugo López-Arévalo. 2015. Registro de mamíferos en las pinturas rupestres de Cerro Azul, Guaviare, Colombia. In Saberes Etnozoológicos Latinoamericanos. Edited by Rafael Monroy, Alejandro García Flores, José Pino Moreno and Eraldo Costa Neto. Feira de Santana: UEFS Editora, pp. 175–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Gabriel, Carlos Franky, and Dany Mahecha. 1999. Los Nukak: Nómadas de la Amazonía Colombiana. Santafé de Bogotá: Editorial Universidad Nacional. [Google Scholar]

- Carden, Natalia. 2009. Prints on the rocks: A study of the track representations from Piedra Museo locality (Southern Patagonia). Rock Art Research 26: 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño-Uribe, Carlos. 2019. Chiribiquete. La Maloka Cosmica de los Hombres Jaguar. Bogota: Villegas Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño-Uribe, Carlos, and Thomas van der Hammen. 2005. Visiones y Alucinaciones del Cosmos Felino y Chamanistico de Chiribiquete. Bogota: UASESPNN Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, Fundacion Tropenbos-Colombia. Embajada Real de los Paises Bajos. [Google Scholar]

- Cayón, Luis, and Thiago Chacon. 2014. Conocimiento, historia y lugares sagrados. La formación del sistema regional del alto río Negro desde una visón interdisciplinar. Anuário Antropológico 39: 201–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagnon, Napoleon. 1997. Yanomamo. New York: Harcourt Brace College. [Google Scholar]

- Challis, Sam. 2019. High and mighty: A San expression of excess potency control in the high-altitude hunting grounds of southern Africa. Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture 12: 169–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correal, Gonzalo, Thomas van der Hammen, and Fernando Piñeres. 1990. Guayabero I: Un Sitio Precerámico de la Localidad Angosturas II, San José del Guaviare. Caldasia 16: 245–54. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, Adrian. 2016. Ethnographic analogy, the comparative method, and archaeological special pleading. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 55: 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, Lewis. 2024. Fragrant ecologies: Aroma and olfaction in Indigenous Amazonia. In Smell, Taste, Eat: The Role of the Chemical Senses in Eating Behaviour. Edited by Lorenzo Stafford. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 141–63. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 1994. In the Society of Nature: A Native Ecology in Amazonia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 2012. Beyond nature and culture: The traffic of souls. Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2: 473–500. [Google Scholar]

- Déléage, Philippe. 2007. Amazonian graphic directories. Journal of the Society of Americanists 93: 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausto, Carlos. 2008. Too many owners: Mastery and ownership in Amazonia. Mana 4: 329–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Llamazares, Álavaro, and Pirjo Virtanen. 2020. Game masters and Amazonian Indigenous views on sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 43: 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, Danae, and Atilio Zangrando. 2006. Painted fish, eaten fish: Artistic and archaeofaunal representations in Tierra del Fuego, Southern South America. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 25: 371–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, Marcos. 1954. Aspectos de la cultura Tukana: Cosmogonía. Revista Colombiana de Antropología 3: 99–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furst, Peter, and Jill Furst. 1981. Seeing a culture without seams: The ethnography of Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff. Latin American Research Review 16: 258–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheerbrant, Alain. 1993. L’Expédition Orénoque-Amazone: 1948–1950. Paris: Gallimard Education. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Irving. 1940. Cosmological beliefs of the Cubeo Indians. Journal of American Folklore 53: 242–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, Alfred Irving. 1960. Ojibwa Ontology, Behaviour, and World View. In Culture in History: Essays in Honor of Paul Radin. Edited by Stanley Diamond. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 19–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie. 2015. Rock Art and Regional Identity: A Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie. 2016. Embodiment, transformation and ideology in the rock art of Trans-Pecos Texas. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26: 217–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, Jamie. 2019. Symbolism, aesthetics, and narrative in rock art. In Aesthetics, Applications, Artistry and Anarchy: Essays in Prehistoric and Contemporary Art. Edited by Jillian Huntley and George Nash. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 109–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie. 2024. Towards an understanding of Indigenous rock art from an ideational cognitive perspective: History, method, and theory from west Texas, North America, and beyond. In Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Archaeology. Edited by Thomas Wynn, Karenleigh Overmann and Frederick Coolidge. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1019–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie. forthcoming. Rock Art and Animism in the Colombian Amazon: Meaning and Motivation at La Serranía La Lindosa.

- Hampson, Jamie, Sam Challis, and Joakim Goldhahn, eds. 2022. Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Graham, ed. 2002. Readings in Indigenous Religions. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Graham. 2014. Relational health: Animists, shamans and the practice of well-being. In Science and Religion: One Planet, Many Possibilities. Edited by Lucas Johnson and Whitney Bauman. London: Routledge, pp. 204–15. [Google Scholar]

- Heizer, Robert, and Martin Baumhoff. 1962. Prehistoric Rock Art of Nevada and Eastern California. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones, Stephen. 1979. The Palm and the Pleiades: Initiation and Cosmology in Northwest Amazonia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones, Stephen. 1996. Shamans, prophets, priests and pastors. In Shamanism, History, and the State. Edited by Nicholas Thomas and Caroline Humphrey. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 32–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones, Stephen. 2016. Writing on stone; writing on paper: Myth, history and memory in NW Amazonia. History and Anthropology 27: 154–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultkrantz, Åke. 1987. Native Religions of North America: The Power of Visions and Fertility. San Francisco: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Timothy. 2006. Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought. Ethnos 71: 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, José, Alan Outram, Michael Ziegler, Patrick Roberts, Mark Robinson, Gaspar Morcote-Ríos, Francisco Javier Aceituno, and Michael Keesey. 2022a. Ice Age megafauna rock art in the Colombian Amazon? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 377: 20200496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iriarte, José, Jamie Hampson, Andrzej Rozwadowski, Francisco Javier Aceituno, and Barbara Oosterwijk. forthcoming. Dancing figures and geometrics in the rock art of La Lindosa, Colombia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

- Iriarte, José, Mark Robinson, Francisco Javier Aceituno, Gaspar Morcote-Ríos, and Michael Ziegler. 2022b. The Painted Forest: Rock art and Archaeology in the Colombian Amazon. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keyser, James, and David Whitley. 2006. Sympathetic magic in western North American rock art. American Antiquity 71: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kopenawa, Davi, and Bruce Albert. 2013. The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, Carobeth. 1976. The Chemehuevi. Banning: Malki Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laming-Emperaire, Annette. 1957. Cilisations préhistoriques. (Fouilles et recherches de laboratoires; le dévelopement des civilisations). In L’Homme, Race et Moeurs. Edited by André Leroi-Gourhan. Paris: Encyclopédie Clartés, vol. 87, pp. 4500–900. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, Esther. 2017. From rau to sacred plants: Transfigurations of shamanic agency among the Siona Indians of Colombia. Social Compass 64: 343–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroi-Gourhan, André. 1965. Treasures of Prehistoric Art. New York: Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, James David. 1981. Believing and Seeing: Symbolic Meanings in Southern African San Rock Art. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, James David. 1991. Wrestling with analogy: A methodological dilemma in Upper Palaeolithic rock art research. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 57: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, James David. 2002. A Cosmos in Stone: Interpreting Religion and Society Through Rock Art. Lanham: Rowman Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, James David. 2006. The evolution of theory, method and technique in southern African rock art research. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 13: 343–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, James David. 2024. Rock art and cognitive archaeology: A personal southern African journey. In Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Archaeology. Edited by Thomas Wynn, Karenleigh Overmann and Frederick Coolidge. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, James David, and Thomas Dowson. 1988. The signs of all times: Entoptic phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic art. Current Anthropology 29: 201–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, James David, Geoffrey Blundell, William Challis, and Jamie Hampson. 2000. Threads of light: Re-examining a motif in southern African San rock art research. South African Archaeological Bulletin 55: 123–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1963. Totemism. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes, and James David Lewis-Williams. 2014. Bridging Realms: Towards Ethnographically Informed Methods to Identify Religious and Artistic Practices in Different Settings. Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture 7: 109–39. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Josephine. 2013. Contemporary meanings and the recursive nature of rock art: Dilemmas for a purely archaeological understanding of rock art. Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture 6: 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, Colin. 2001. Seats of power: Axiality and access to invisible worlds. In Unknown Amazon. Edited by Colin McEwan, Cristiana Barreto and Eduardo Neves. London: British Museum Press, pp. 176–97. [Google Scholar]

- McGranaghan, Mark, and Sam Challis. 2016. Reconfiguring hunting magic: Southern Bushman (San) perspectives on taming and their implications for understanding rock art. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26: 579–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Métraux, Alfred. 1949. Religion and shamanism. In Handbook of South American Indians; Edited by Julian Steward. Washington, DC: United States Printing Office, vol. 5, pp. 559–99. [Google Scholar]

- Miotti, Laura, and Natalia Carden. 2007. Relationships between Rock Art and the Archaeofauna in the Central Patagonian plateau (Argentina). Oxford: BAR Publishing, p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- Morcote-Ríos, Gaspar, José Iriarte, Francisco Javier Aceituno, Mark Robinson, and Jeison Chaparro-Cárdenas. 2021. Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa. Quaternary International 578: 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro-Abadía, Oscar, and Martin Porr, eds. 2021. Ontologies of Rock Art: Images, Relational Approaches, and Indigenous Knowledge. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Ana, and Guadalupe Romero Villanueva. 2020. South American art. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Edited by Claire Smith. New York: Springer, pp. 2914–40. [Google Scholar]

- Munduruku, Jairo, Eliano Munduruku, and Raoni Valle. 2021. Muraycoko Wuyta’a Be Surabudodot/Ibararakat: Rock art and territorialization in contemporary Indigenous Amazonia—The case of the Munduruku people from the Tapajós River. In Visual Culture, Heritage and Identity: Using Rock Art to Reconnect Past and Present. Edited by Andrzej Rozwadowski and Jamie Hampson. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 107–19. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Guillermo. 2020. Estética amazónica y discusiones contemporáneas: El arte rupestre de la serranía La Lindosa, Guaviare, Colombia. Revista de Investigación en el Campo del Arte 15: 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimuendajú, Curt. 1939. The Apinayé. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterwijk, Barbara, Jo Osborn, José Iriarte, Jamie Hampson, Francisco Javier Aceituno, and Gaspar Morcote-Ríos. forthcoming. A cross-cultural analysis of decorated handprints in rock art: A view from La Lindosa, Colombian Amazon. World Archaeology.

- Pilaar Birch, Suzanne, ed. 2018. Multispecies Archaeology. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Politis, Gustavo. 2007. Nukak: Ethnoarchaeology of an Amazonian People. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Politis, Gustavo, and Nicholas Saunders. 2002. Archaeological correlates of ideological activity: Food taboos and spirit-animals in an Amazonian hunter-gatherer society. In Consuming Passions and Patterns of Consumption. Edited by Preston Miracle and Nicky Milner. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Prous, André. 2007. Arte Pré-histórica do Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Arte, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Geraldo. 1967. A brief field report on urgent ethnological research in the Vaupés Area, Colombia, South America. Bulletin of the International Committee on Urgent Anthropological and Ethnological Research Wien 9: 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Geraldo. 1971. Amazonian Cosmos: The Sexual and Religious Symbolism of the Tukano Indians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Geraldo. 1976. Cosmology as ecological analysis: A view from the rain forest. Man 11: 307–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Geraldo. 1978a. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Geraldo. 1978b. Drug-induced optical sensations and their relationship to applied art among some Colombian Indians. In Art and Society: Studies in Style, Culture and Aesthetics. Edited by Michael Greenhalgh and Vincent Megaw. London: Duckworth, pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Geraldo. 1985. Tapir avoidance in the Colombian Northwest Amazon. In Animal Myths and Metaphors in South America. Edited by Gary Urton. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 107–43. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Geraldo. 1987. Shamanism and Art of the Eastern Tukanoan Indians: Colombian Northwest Amazon. Groningen: Institute of Religious Iconography. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Geraldo. 1997. Rainforest Shamans: Essays on the Tukáno Indians of the Northwest Amazon. Dartington: Themis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Riris, Philip, José Oliver, and Natalia Lozada Mendieta. 2024. Monumental snake engravings of the Orinoco River. Antiquity 98: 724–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, Peter. 1994. WYSINWYIG in Amazonia. Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 25: 255–62. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Mark, Francisco Javier Aceituno, Gaspar Morcote-Ríos, Juan Berrío, Patrick Roberts, and José Iriarte. 2021. ‘Moving South’: Late Pleistocene plant exploitation and the importance of palm in the Colombian Amazon. Quaternary 4: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Mark, Jamie Hampson, Francisco Javier Aceituno, Gaspar Morcote-Ríos, Jo Osborn, Michael Ziegler, and José Iriarte. 2024. Animals of the Serranía de la Lindosa: Exploring representation and categorisation in the rock art and zooarchaeological remains of the Colombian Amazon. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 75: 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodd, Robin. 2002. Snuff synergy: Preparation, use and pharmacology of yopo and Banisteriopsis caapi among the Piaroa of southern Venezuela. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 34: 273–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Eric, Margaret Arnott, Ellen Basso, Stephen Beckerman, Robert Carneiro, Richard Forbis, and Wilma Wetterstrom. 1978. Food taboos, diet, and hunting strategy: The adaptation to animals in amazon cultural ecology. Current Anthropology 19: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostain, Stéphen. 2019. Un Lascaux en Amazonie. Pour la Science 498: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, Thembi. 2017. ‘People will no longer be people but will have markings and be animals’: Investigating connections between diet, myth, ritual and rock art in southern African archaeology. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 52: 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando. 2008. Writing history into the landscape: Space, myth and ritual in contemporary Amazonia. American Ethnologist 25: 128–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando. 2009. The Occult Life of Things: Native American Theories of Materiality and Personhood. Flagstaff: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, Glen. 1999. Shamanism and diversity: A Machiguenga perspective. In Cultural and Spiritual Values of Diversity: Indigenous Peoples, Their Environments and Territories. Edited by Darrell Posey. London: Intermediate Technology Publications, pp. 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, Ismael. 2019. El Payé y los Mundos Espirituales. San José de Guaviare: Gobernación del Guaviare, Secretaria de Cultura y Turismo. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Brian, and Sam Challis. 2023. Becoming elands’ people: Neoglacial subsistence and spiritual transformations in the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains, southern Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 78: 123–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Hannah Johnson, Phillip Dukes, Stephanie De Sola, and Kristen Simmons. 2011. Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Delamar Valley Solar Energy Zone. Washington, DC: Bureau of Land Management Solar Programmatic EIS. [Google Scholar]

- Surallés, Alexandre. 2005. Intimate horizons: Person, perception and space among the Candoshi. In The Land Within: Indigenous Territory and Perception of the Environment. Edited by Alexandre Surallés and Pedro García Hierro. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, pp. 126–49. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso, Andrés, and Felipe Armstrong. 2022. Making rock art: Correspondences, rhythms, and temporalities. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 30: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, Andrés, Felipe Armstrong, and Mara Basile. 2017. Rock art in Central and South America: Social settings and regional diversity. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Edited by Bruno David and Ian McNiven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso, Andrés, Marcela Sepúlveda, Francisca Moya, and José Carcamo. 2018. First absolute dating of Andean hunter-gatherer rock art paintings from North Central Chile. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 9: 223–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, Judith. 2016. Step forwards in the archaeometric studies on rock paintings in the Bogotá Savannah, Colombia. Analysis of pigments and alterations. In Paleoart and Materiality: The Scientific Study of Rock Art. Edited by Robert Bednarik, Danae Fiore and Mara Basile. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tuyuka, Poani, Kumu Tukano, Kumu Makuna, Kumu Desano, and Raoni Valle. 2022. Toñase Masise Tutuase—Memory, Knowledge and Power Between Tukanoan Kumuã and Rock Art Wametisé in the Middle Tiquié River, Northwest Amazonia. In Rock Art and Memory in the Transmission of Cultural Knowledge. Edited by Leslie Zubieta. Cham: Springer, pp. 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina, Fernando. 1994. El hombre sentado: Mitos y petroglifos en el río Caquetá. Boletín del Museo del Oro 36: 67–111. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina, Fernando, and Jorge Peña. 2016. Perros de guerra, caballos, vacunos y otros temas en el arte rupestre de la serranía de La Lindosa (río Guayabero, Guaviare, Colombia): Una conversación. Ensayos: Historia y Teoría del Arte 20: 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, Daniela, José Capriles, Calogero Santoro, Ronny Peredo, María Quinteros, Eugenia Gayó, and Marcela Sepúlveda. 2015. Consumption of animals beyond diet in the Atacama Desert, northern Chile (13,000–410 BP): Comparing rock art motifs and archaeofaunal records. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 40: 250–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, Raoni, Gori-Tumi Lopez, Poani Tuyuka, and Jairo Munduruku. 2018. What is anthropogenic?: On the cultural aetiology of geo-situated visual imagery in indigenous Amazonia. Rock Art Research 35: 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- van der Hammen, Thomas. 2006. Bases para una prehistoria ecológica amazónica y el caso Chiribiquete. In Pueblos y Paisajes Antiguos de la Selva Amazónica. Edited by Gaspar Morcote-Ríos and Carlos Franky. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Taraxacum, pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Vinnicombe, Patricia. 1972. Myth, motive, and selection in southern African rock art. Africa 42: 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 1998. Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4: 469–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriesendorp, Corine, Nigel Pitman, Alejandra Salazar Molano, Diana Alvira Reyes, Arelis Arciniegas, Rodrigo Botero García, Lesley de Souza, Álvaro del Campo, Tyana Wachter, and Douglas Stotz, eds. 2018. Colombia: La Lindosa, Capricho, Cerritos. Rapid Biological and Social Inventories Report 29. Chicago: The Field Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David. 1994. By the hunter, for the gatherer: Art, social relations and subsistence change in the prehistoric Great Basin. World Archaeology 25: 356–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David. 2009. Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit: The Origin of Creativity and Belief. Amherst: Prometheus. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David. 2021. Rock art, shamanism, and the ontological turn. In Ontologies of Rock Art: Images, Relational Approaches, and Indigenous Knowledges. Edited by Oscar Moro Abadía and Martin Porr. London: Routledge, pp. 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Willerslev, Rane. 2013. Taking animism seriously, but perhaps not too seriously? Religion and Society 4: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Robin. 2013. Mysteries of the Jaguar Shamans of the Northwest Amazon. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, Alison. 1985. The reaction against analogy. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 8: 63–111. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, Caco. 2012. A escrita da Ñaperikoli. Ensaio sobre os petroglifos do rio Içana. In Rotas de Criação e Transformação Narrativas de Origem dos Povos Indígenas do Rio Negro. Edited by Geraldo Andrello. São Gabriel da Cachoeira: FOIRN/ISA, pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Yoamara, Asatrizy-Kumua, Carlos Hernández Vélez, Sebastian Restrepo Calle, and Elcy Corrales Roa. 2020. Cosmology as Indigenous land conservation strategy: Wildlife consumption taboos and social norms along the Papuri River (Vaupés, Colombia). In Indigenous Amazonia, Regional Development and Territorial Dynamics: Contentious Issues. Edited by Walter Leal Filho, Victor King and Ismar Borges de Lima. Cham: Springer, pp. 311–39. [Google Scholar]

| Panel | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curronchos | Demoledores | Dantas | Más Largo | Principal | Reserva | Total | % of total | |

| Total images | 153 | 171 | 998 | 1031 | 626 | 244 | 3223 | 100 |

| Non-figurative | 112 | 115 | 344 | 356 | 242 | 175 | 1344 | 41.7 |

| Figurative | 41 | 56 | 654 | 675 | 384 | 69 | 1879 | 58.3 |

| Animal | 23 | 17 | 203 | 144 | 154 | 15 | 556 | 17.25 |

| % of total panel images | 15 | 9.9 | 20.3 | 14 | 24.6 | 6.1 | ||

| % of total panel figurative images | 56.1 | 30.4 | 31 | 21.3 | 40.1 | 21.7 | ||

| Human | 3 | 12 | 209 | 203 | 83 | 21 | 531 | 16.48 |

| % of total panel images | 2 | 7 | 20.9 | 19.7 | 13.3 | 8.6 | ||

| % of total panel figurative images | 7.3 | 21.4 | 32 | 30.1 | 21.6 | 30.4 | ||

| Schematised | 7 | 24 | 149 | 266 | 86 | 28 | 560 | 17.38 |

| % of total panel images | 4.6 | 14 | 14.9 | 25.8 | 13.7 | 11.5 | ||

| % of total panel figurative images | 17.1 | 42.9 | 22.8 | 39.4 | 22.4 | 40.6 | ||

| Handprint | 0 | 0 | 88 | 50 | 51 | 0 | 189 | 5.86 |

| % of total panel images | 0 | 0 | 8.8 | 4.8 | 8.1 | 0 | ||

| % of total panel figurative images | 0 | 0 | 13.5 | 7.4 | 13.3 | 0 | ||

| Flora | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 29 | 0.9 |

| % of total panel images | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 2 | ||

| % of total panel figurative images | 2.4 | 5.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 7.2 | ||

| Object | 7 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0.43 |

| % of total panel images | 4.6 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | ||

| % of total panel figurative images | 17.1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hampson, J.; Iriarte, J.; Aceituno, F.J. ‘A World of Knowledge’: Rock Art, Ritual, and Indigenous Belief at Serranía De La Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon. Arts 2024, 13, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13040135

Hampson J, Iriarte J, Aceituno FJ. ‘A World of Knowledge’: Rock Art, Ritual, and Indigenous Belief at Serranía De La Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon. Arts. 2024; 13(4):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13040135

Chicago/Turabian StyleHampson, Jamie, José Iriarte, and Francisco Javier Aceituno. 2024. "‘A World of Knowledge’: Rock Art, Ritual, and Indigenous Belief at Serranía De La Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon" Arts 13, no. 4: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13040135

APA StyleHampson, J., Iriarte, J., & Aceituno, F. J. (2024). ‘A World of Knowledge’: Rock Art, Ritual, and Indigenous Belief at Serranía De La Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon. Arts, 13(4), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13040135