1. Introduction

So long as time moves in circles and lines, so will music. But exactly how the shape of sound is perceived is complicated by its many modes of expression. Performing music, listening to it, and writing it down all engage with the patterns of music in different ways. When monastic musicians started developing notation in the ninth century, they were documenting chants that had been shaped through oral transmission over the course of centuries, polished like river rocks in the mouths of countless singers before they were preserved on parchment. The shape of this music was formed through lived experience; melodic lines would rise and fall as vibrations in the vocal tract, and circles were inscribed in the body through physical repetitions.

In the tenth century, the two-dimensional visualization of melodic shape was brought into notation; in the Aquitanian notation system, neumes (musical notes) were placed higher or lower on the page according to their pitch, a shift which made notation less like words and more like drawings. But still, not all musical shapes translate so easily to the page. Notation tends to obscure as much as it reveals about the structures underlying a work because the pragmatics of performance usually take precedence over the ideals of form.

For example, we say that canons are circular. In a canon, one of the simplest polyphonic forms, multiple instances of the same melody are looped, overlapping upon each other. From time to time, scores pop up that incorporate the form directly into the notation. Straddling the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, French composer Baude Cordier’s

Tout par compas suy composés (With a compass was I composed) is the earliest example of a circular score (

Figure 1). Cordier is associated with the

Ars subtilior movement, which is known for elevating the art of notation and the complexity and cleverness of ideas that notation can convey.

Tout par compas captures not only the form of the music, but also the self-reflexivity of the lyrics, “With a compass was I composed”.

Peppered throughout the centuries, other examples of circular scores show up here and there, often with their own symbolic meanings. More than five-hundred years after Cordier, James Tenney’s (1934–2006) circular notation for “A rose is a rose is a round” highlights the circularity inherent in Gertrude Stein’s famous phrase, “A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”. But it is rare for the form of a work to be notated so explicitly. The vast majority of canons are notated in the standard horizontal fashion because performers need the linear details more than they need a visualization of the gestalt. Point being, most of the time, the formal shapes of music are experienced in the mind rather than on the page.

The difference between the shape of a sound and the look of the notation is made explicit in

Metastaseis, Iannis Xenakis’ 1953–1954 orchestral work (

Figure 2). Xenakis, a polymath trained as a mathematician, architect, and composer, built this piece around hyperbolic paraboloid shapes, which are clearly audible in performance. In his sketches of the work, the connections of image and sound via shape are clear and simple; yet, when orchestrated for 61 individual string instruments, the demands of the score distort the curving shapes of the music (

Figure 3). However, Xenakis did manage to encode the form of the music in the curvature of a building in an exquisite show of cross-modality; when he was later appointed lead architect on the Philip’s Pavilion for the 1958 World’s Fair, he borrowed these musical forms into the architectural domain thanks to his master’s thesis on reinforced concrete, the technology that made possible the iconic curved roof of the pavilion (

Figure 2).

Styles change and technology develops but there is so much that stays the same through the centuries. In every era, there are examples of compositions that grapple directly with the substance of music itself, exploring how ideas can be encoded into sound. But when reconstructing ancient music, much of the context is lost and usually the only thing that remains is the notation. How then, can the forms and ideas that shaped a composition be reverse engineered when they may not be readily apparent in the notation? And how, with a distance of one-thousand years, does one tease apart the novel from the commonplace?

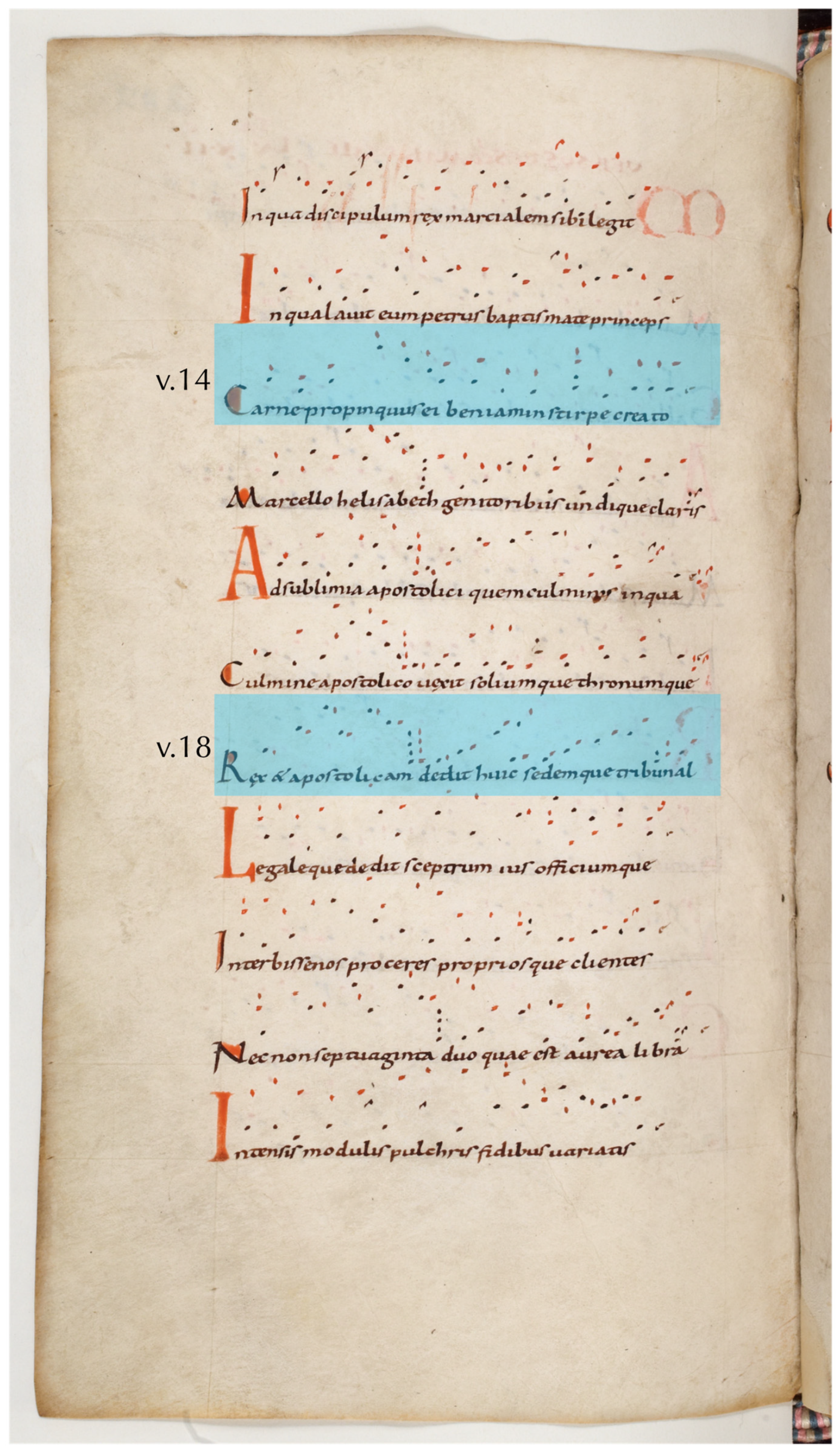

The Versus de Sancto Marcialis Septuaginta Duo (72 Verses for St. Martial) found in the manuscript Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département de Manuscrits, Latin 909 (Paris 909) is a remarkably early case of a composition whose composer is known by name. Written in 1028–1029 by Benedictine monk Ademar de Chabannes (989–1034), the 72 Verses have been a subject of niche curiosity for medieval musicologists for the past many decades, but the chant has generally lingered in obscurity and has yet to take its rightful place in the long view of music history, in the canon of works with extraordinary forms. Through its inclusion, the timeline of polyphonic master works is stretched further back a couple hundred years, back to the inception of standardized notation practices.

Like Xenakis, Ademar de Chabannes was a polymath who was sensitive to unique connections across different disciplines and modalities thanks to his specialized knowledge. Not only a master musician and composer, Ademar was also a writer, erudite scholar, illustrator, and forger. Ademar was one of the leading scribes at a time when the Aquitanian approach to notation had been established for a few decades and was ready for refinement (

Grier 2006). He was central to developments in the first half of the eleventh century that resulted in more precise notation; the heighting of the neumes was standardized, assisted by the introduction of the

drypoint line (uninked lines scratched into the parchment) and the

custos (small pitch indicator at the end of the line).

One significant consequence of these notational developments is that it became possible to share new melodies through writing, whereas previously notation functioned as a mnemonic device for those who had already heard the tune. Through Ademar’s innovations as both scribe and composer, we have a unique opportunity to observe how new musical ideas were conceived of and documented at a time of shifting relationships between oral and written practices. And in an era when composing was still largely an anonymous practice, we have a large body of chants that Ademar composed either as standalone works or as new additions to older chants. The depth of knowledge of Ademar’s musical contributions is known thanks to the work of James Grier, who has done the meticulous work of identifying Ademar’s hand in the many manuscripts he worked on at Limoges.

Officially, Ademar did not belong to the abbey of St. Martial of Limoges, the regional center of musical thought. His home abbey was in Angoulême, but he was a frequent visitor and had strong familial connections to St. Martial through his Uncle Roger, the cantor (

Landes 1995). Ademar was ambitious, and when his desire to be named abbot at Angoulême was thwarted, he set out to deepen his relationship with Limoges, intertwining his own goals with the abbey’s. Through the first decades of the eleventh century, the abbey of St. Martial ascended in popularity as a pilgrimage stop, and along with its renown, grew the tale that the abbey’s patron saint was not in fact a third-century bishop, but instead had lived in Jerusalem in the first century as one of the seventy-two apostles called forth by Christ in Luke Chapter 10.

Ademar became a zealous promoter of this new version of St. Martial’s life, and the apostolic cause engaged all his skills: he composed new and altered older music, forged documents, and wrote texts informed by his deep knowledge of biblical and extra-biblical literature. If the apostolicity of Martial were to be accepted, the abbey would benefit through greater prestige, wealth, and power, while Ademar too would be honored as the key architect of the endeavor. Through the 1020s, Ademar was extensively involved with the creation and alteration of manuscripts, musical and otherwise, that enhanced this mythology. As lead scribe for Paris 909, originally intended for the nearby abbey of St. Martin, Ademar co-opted the text to create a new liturgy that would celebrate St. Martial as an apostle (

Grier 2006). He personally contributed a great deal of newly composed music to St. Martial in this manuscript, including the

72 Verses for St. Martial. The exact purpose of the

72 Verses is not known, but there are certain positions in the liturgy reserved for more elaborate vocal pieces where it could have been inserted (

Ferreira 2002). What we do know is that it was part of a collection of music designed to create a spectacle.

The

72 Verses are based on the story of St. Martial according to the

Vita prolixior, which Ademar was also tasked with revising (

Appendix A). This official accounting of the saint’s life, dating to the 1020s, modified older versions to advance the apostolic version of events. As Richard Landes lays out in

Relics, Apocalypse and the Deceits of History, in this new version, he offered “proof of the antiquity of the title

apostolus Martialis … emphasized Martial’s personal ties with Jesus, thus shifting his discipleship directly to the Lord himself and redefining his relationship with Peter as one of companion and equal” and “expanded the scope of Martial’s mission to include all of Gaul and correspondingly increased the range of Duke Stephen’s dominion to coincide. He also redefined the relationship between duke and apostle to emphasize the honor and obedience the layman paid the churchman” (

Landes 1995). Thus, through this new version, the saint’s vita Martial’s power was expanded in more ways than one: his domain expanded from Limoges to Gaul, his position elevated from bishop to apostle, and even as apostle his importance is enhanced through closer affiliation with St. Peter.

The era InIch

72 Verses was written was at a crossroads of written and oral practices; the role of notated music was changing and new methods of composition were emerging, but performance practice was still deeply rooted in memorization (

Grier 2006). Much has been studied about memory practices with regard to the medieval singer, revolving around the intense memorization of the Psalms, psalm tones, antiphons, responsory tones, and other stock materials of daily musical worship (

Busse-Berger 2005). We know much less about the compositional process around which chants were created because so many of them have existed since time immemorial. With the

72 Verses being a new creation dated to the late 1020s by a known composer, there is much to learn from it about how a composition was created from scratch. As a standalone work, lacking the constraints of defined chant genres, Ademar had the freedom to experiment and tailor the piece to his preferences. Because he was also presumably one of the performers of the

72 Verses, this chant offers a keen insight into just how deeply structure and memory are intertwined in medieval composition.

The notation of the

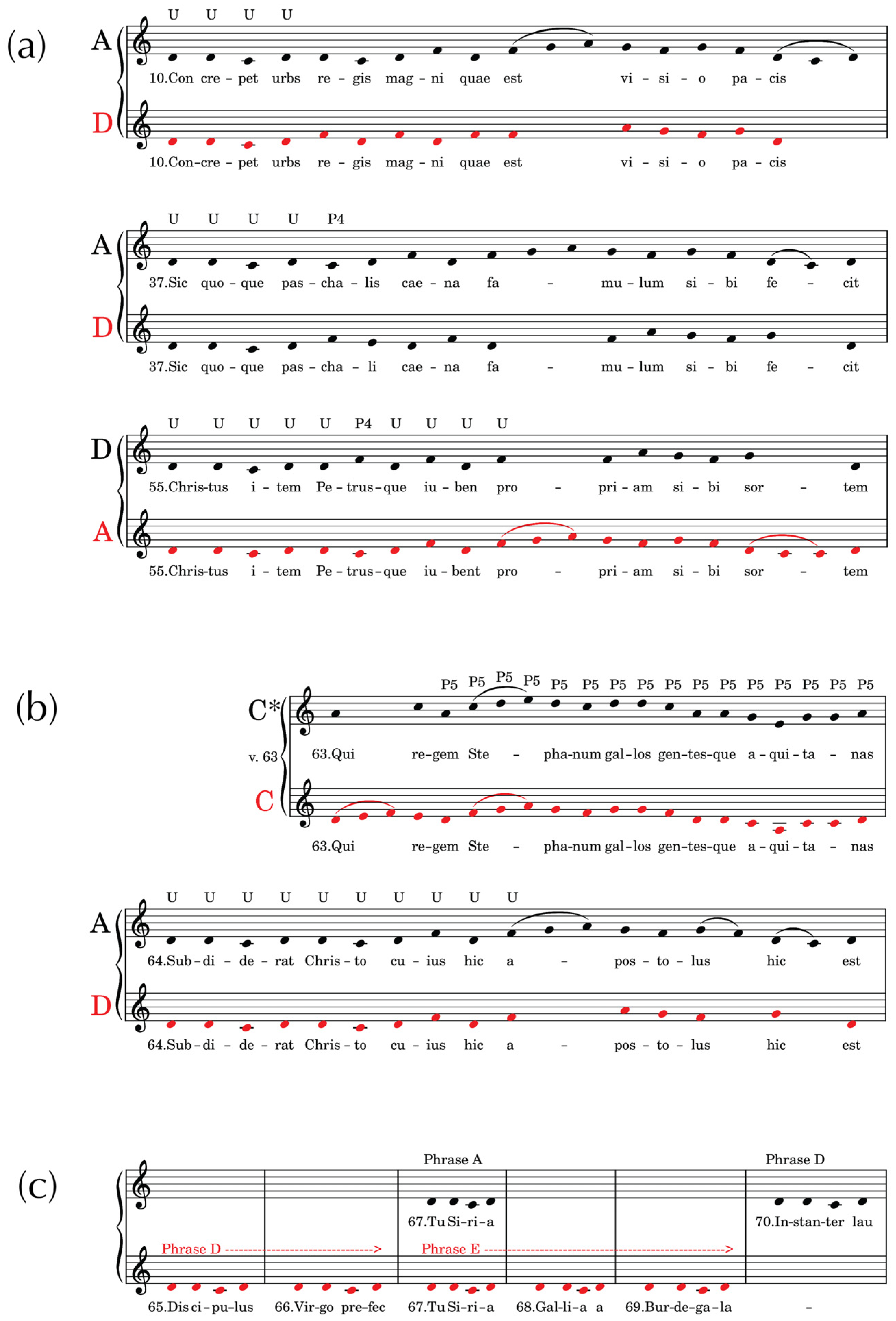

72 Verses stands out because two different colors of ink, red and black, were used to transmit two overlapping melodies (

Figure 4). Also in red ink, the chant is organized by an acrostic that spells out MARCIALIS APOSTOLVS XRISTI (Martial, apostle of Christ) with large initials at the beginning of each tercet. While many music manuscripts in the early eleventh century were richly decorated with brightly colored illuminations, the use of two colors of ink for the notation itself was rare for the time. The two colors indicate one of two possibilities: either the two melodies are meant to be performed together by two different singers or groups of singers or they provide two separate versions of the same chant. If meant to be performed together, then this chant precedes other notated examples of Aquitanian polyphony by at least half a century. While it is assumed that Aquitanian polyphonic vocal practices were well-established in Ademar’s day, there are not any other contemporary written examples to compare this notation to nor are there any notation standards regarding polyphony at that time.

When I first started working with the 72 Verses for St. Martial, I was seeking creative inspiration rather than a research project, composing some sketches for a new chamber work. I was enjoying deliberately misreading the notations because, while there are clear correspondences between the two parts, the way the neumes appear on the page makes for a strange coexistence. The manuscript looks as though the notation practices of that time could not quite accommodate the music the composer wished to express. Even just to use the music incorrectly, it was necessary to determine some of the actual musical information such as the mode, transcribe some of the melodies, etc. Yet, in all that time, it never once crossed my mind that the 72 Verses might not be polyphonic.

It was not until coming across the 2002 paper of Manuel Pedro Ferreira, “Is it Polyphony?”, that I learned that the chant’s basic nature was the subject of debate because of an influential study that Paul Hooreman published in 1949, “St. Martial de Limoges au temps de l’abbé d’Odolric (1025–1040): Essai sure une pièce oubliée du reperterriestousin” (

Ferreira 2002). In that paper, Hooreman identifies the two notations as two different versions of the same monophonic chant and denies any polyphonic nature to the work. Ferreira raises questions about Hooreman’s analysis, proposing that a polyphonic interpretation should be reconsidered.

According to Hooreman, the black notation was the first version of the chant and the red notation a simplified variation that was added later (

Hooreman 1949). He provides a detailed analysis of the form of both melodies but does not consider the implications of their juxtaposition. While Hooreman’s study is thorough, it is also dismissive of the idea that the chant might possess any artistic merits. He criticizes the poetry for being run-on and finds fault with structural features of both the black and the red notations. It is unfortunate that Hooreman seems to have never entertained the possibility that the chant could be polyphonic because if he had, he might have discovered these “problems” resolve when the chant is analyzed polyphonically.

To echo Ferreira, Hooreman’s only mention of polyphony was that he would be surprised if the monks of Abbot Odolric (Limoges, 1025–1040) had been learned in double-counterpoint (

Ferreira 2002). But in the case of the

72 Verses, we have the rare privilege of knowing exactly who composed this chant. The burden here is not to prove whether the polyphony functions within a particular tradition, but rather whether Ademar de Chabannes, specifically, might have composed a work such as this; few others could have quite the same combination of music expertise and passion for the apostolicity of St. Martial.

Considering the work as a creation of one mind rather than an example of a school of thought makes it easier to think of the

72 Verses as an experimental, outlier work that might not completely conform to the expected practices of early eleventh-century Aquitanian musicians. Ferreira offers some background on why the behavior of this polyphony is tricky to position within a particular tradition, but ultimately concludes that many of the confounding features of the polyphony, such as the proliferation of major and minor seconds in the harmony, do show up elsewhere (

Ferreira 2002). In other words, this polyphony has plenty in common with other contemporary practices, but the particular combination of musical rules and behaviors are unique.

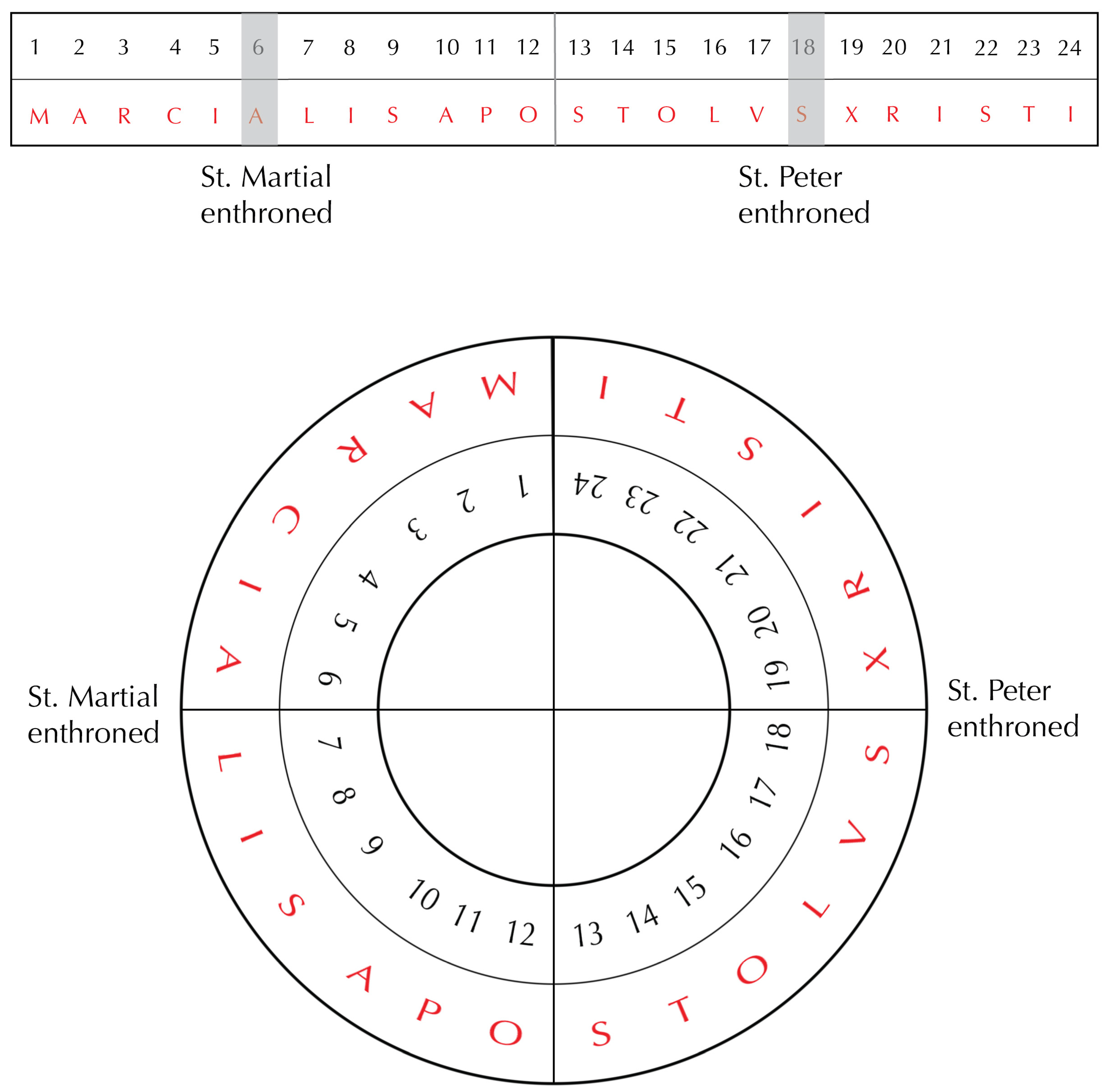

As I see it, the answers to the questions about the polyphony are rooted not in the music, but in the structure of the poetry (

Figure 5). The backbone of the composition, the acrostic MARCIALIS APOSTOLVS XRISTI, partitions the chant into 24 tercets. This acrostic determines not only the poetic form, but also the musical form of the red melody. Furthermore, there is a second acrostic nested within the first that is revealed by the form of the black melody. This secret acrostic reads MISSUS XRISTI (messenger of Christ), which pairs beautifully with the primary acrostic because

missus is the Latin gloss of the Greek

apostolus. I argue that the connection of the two melodies to these acrostics are proof that both melodies were created at the same time, as two parts of one unified composition. I suspect that Ademar, inspired by the elegant nesting of these semantically linked acrostics, set out to create a musical analogue of the wordplay through the two melodies. In the analysis, I will demonstrate that there is a quasi-combinatorics procedure at play that shapes the relationship between these two notations and that the way this procedure generates harmony is what accounts for the unusual polyphony.

Seeing how the 72 Verses for St. Martial was composed connects the dots between medieval rhetorical memory practices and medieval musical memory practices. It is interesting to learn how much the creation of this new composition is about a cognition of images. Because the length of the 72 Verses challenges the memory, numerous mnemonic devices are stitched into the basic structures of the poetry and the music. All of the music, for example, is created out of only nine melodies that repeat in easily recognizable patterns. The poetry is broken down into more manageable units as well, subdividing into eight sections that each map to a different location. All put together, those locations describe a journey upon maps of the heavens and of earth that tells the story of St. Martial’s life, according to the newly revised apostolic biography in the Vita prolixior.

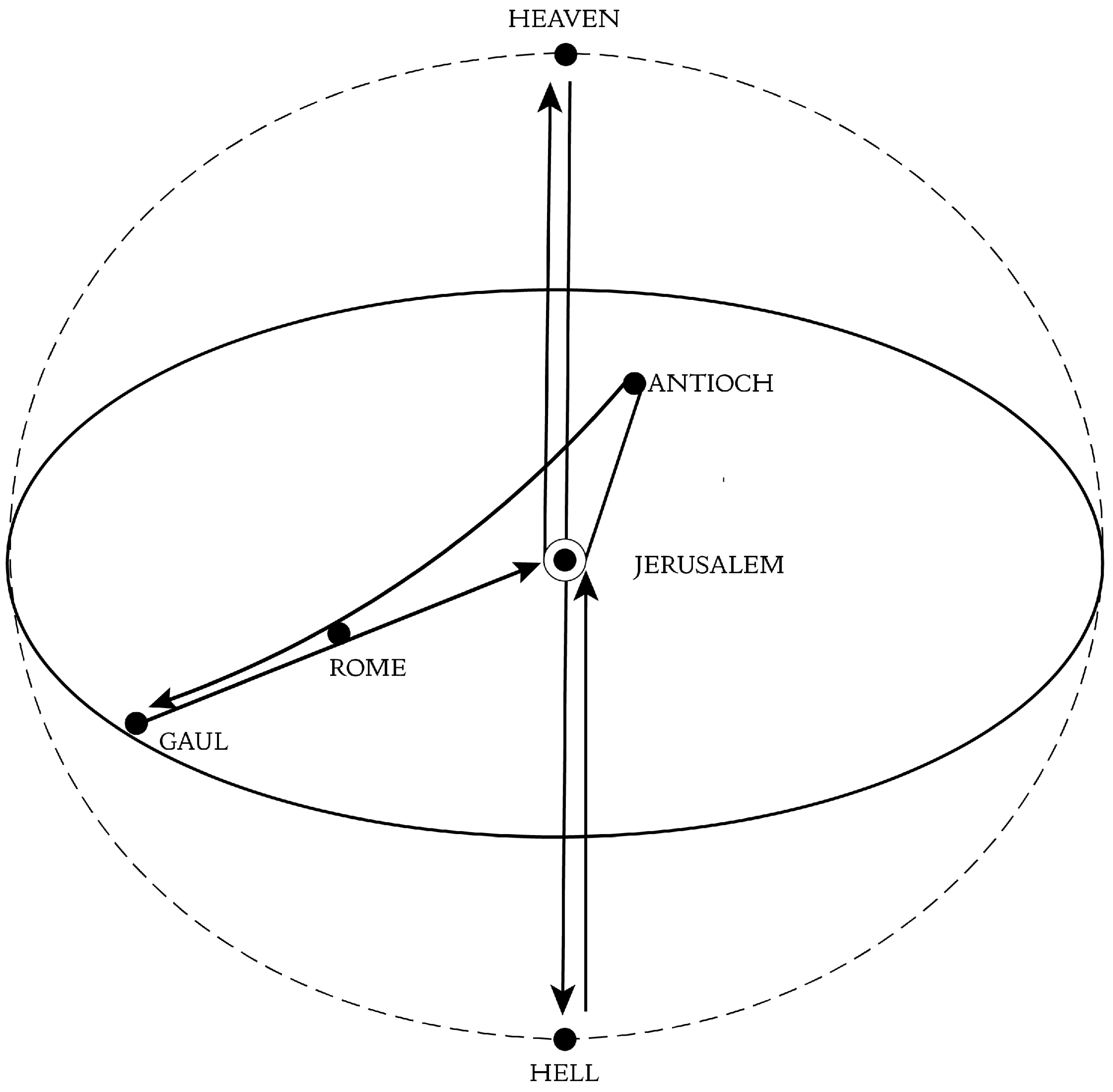

As the chant is rendered from beginning to end, the performer goes on this journey, envisioning a pilgrimage from Gaul to Rome to Jerusalem, ascending through the celestial spheres to Heaven and descending to the Underworld, then departing Jerusalem for Antioch, Rome, and ultimately Gaul (

Figure 6). The final scene zooms out to a full view of the cosmos, as all Heaven and Earth sing the praises of Martial, apostle of Christ. Numerological clues in the poetry add iconography to the scene; the celestial spheres are represented by the muses who join in the singing with the angels, and to the left and right of the cosmos are St. Martial and St. Peter, seated in thrones. From Heaven, Christ holds up his right hand in blessing, and below the map, in the underworld, Christ gifts St. Martial with the power of resurrection (

Figure 7).

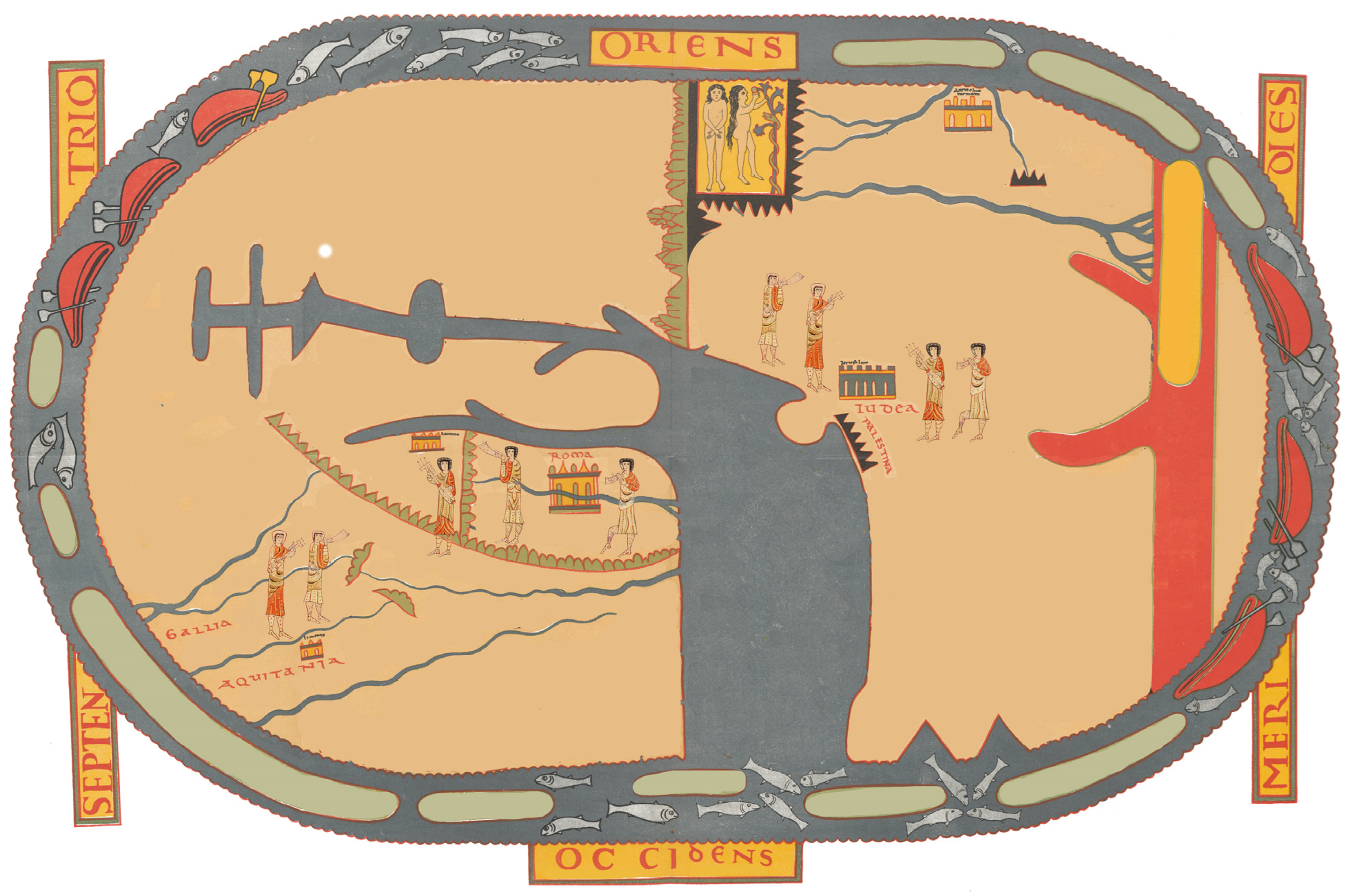

The structure of the

72 Verses makes use of the robust visual imagination that the performers already possessed, borrowing from rhetorical practices the method of loci, in which different ideas were mentally positioned in different locales upon a shared background image, such as a map. Mary Carruthers speaks of the medieval craft of memory as a compositional art, “Monastic

memoria, like the Roman art, is a locational memory; it also cultivates the making of mental images for the mind to work with as a fundamental procedure of human thinking” (

Carruthers 1998). She describes the mappa mundi as an open space upon which other ideas can be placed, calling to attention the mappa mundi at the beginning of the

Beatus of Liébana Commentary on the Apocalypse. While the original manuscript of the eight-century monk, Beatus of Liébana, is lost to history, the copies that survive from the tenth and eleventh centuries are known for their large, brightly colored illuminations depicting biblical events, in particular from the Revelation of St. John (

Williams 2011). Carruthers remarks that the placement of the mappa mundi at the beginning of these manuscripts “opens up the imaginative function”. She discusses in particular the map in the Saint Sever copy, which was created in Aquitaine around the same time as the

72 Verses, between 1028 and 1072 (

Figure 8). These illuminations offer an example of imagery that a performer of the

72 Verses could have had in their mind when memorizing different sections of the lyrics in connection to their different locales. Along with the mappa mundi from the Saint Sever Beatus, I offer a modification of Konrad Miller’s 1896 facsimile to model how one might use the map as a blank space to picture only the areas relevant to a particular story (

Figure 9).

The key to understanding the 72 Verses is seeing how this grand vision is modeled in the polyphonic structure of the music. Through the numbering of the verses and the use of acrostics, the music and poetry are built upon the same foundations, and together, they depict the new apostolic iconography of St. Martial. There are relationships in two-part writing that cannot exist in a monophonic reading of the music, so there is an extraordinary level of detail and craft that will otherwise go unnoticed in a monophonic analysis. This study plunges into the messy mass of data and details that proliferate once the red and black notations become linked.

While I disagree with Hooreman’s monophonic perspective, I am grateful for his nuanced observations because they were invaluable clues to uncovering the multimodal structures that shape the work. Essentially, I followed his astute criticisms of the work and asked the question, “Would this still be an issue if the work were polyphonic?” and kept coming up with the answer, “No”. I am also deeply indebted to Ferreira for his prior work on this topic and carry forward with pursuing further analysis of many observations that he touched on in his paper. Ultimately, the goal of analyzing the 72 Verses is to gain a better understanding of how to perform the music, but before approaching the questions surrounding an actual performance, my aim in this study is to first reconstruct how the polyphony was composed and to see where that leads in terms of interpretation.

2. Analysis 1: Two Nested Acrostics Shape the Polyphonic Structure

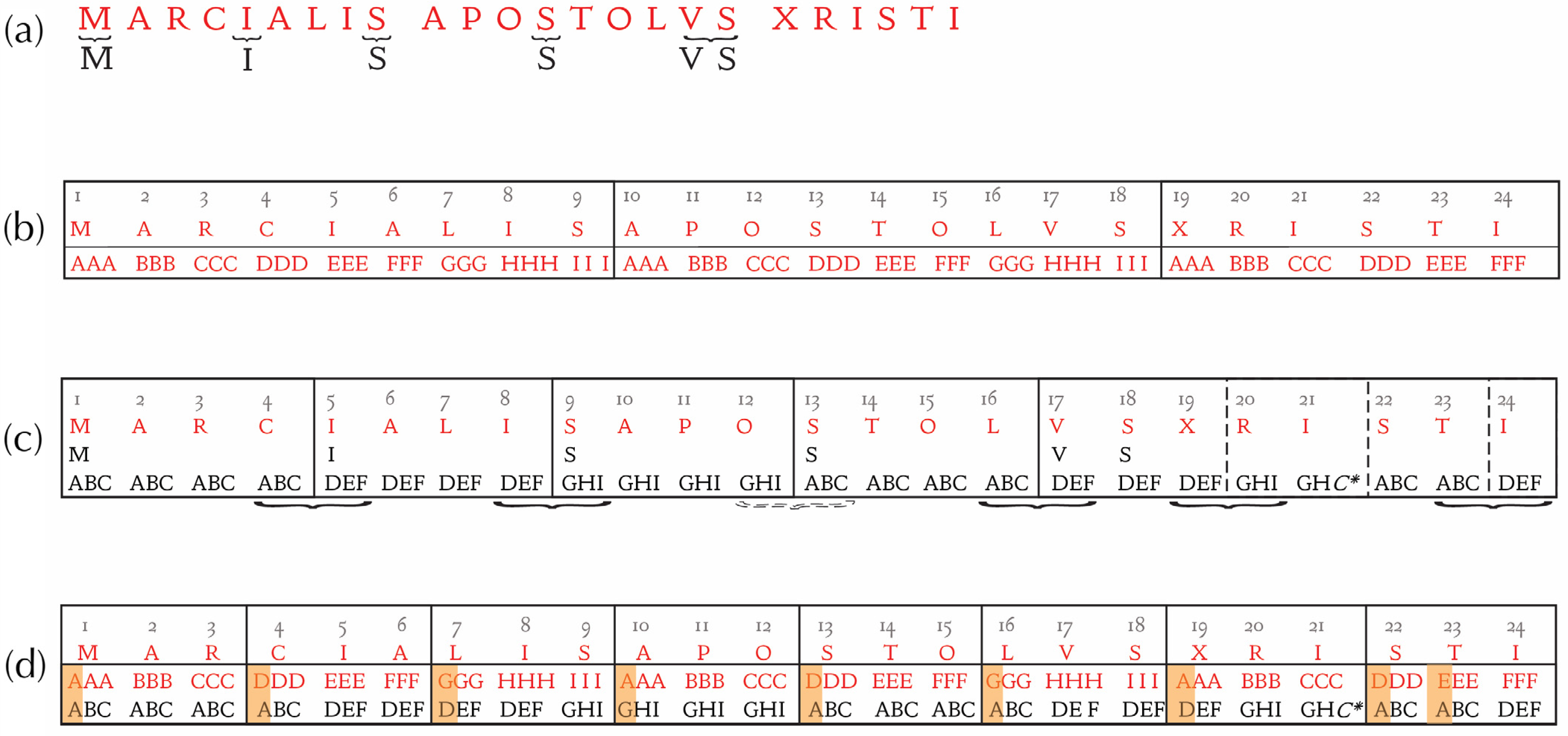

The acrostic MARCIALIS APOSTOLVS XRISTI shapes both the poetic form and the form of the red notation (

Figure 5). The connection between text and music is direct; for each tercet, the same melody repeats three times (AAA BBB CCC etc.), and because there are nine letters in both MARCIALIS and APOSTOLVS, the red notation starts over at melody A every time a new word begins in the acrostic. In contrast, the black notation groups the melodies into the trios ABC, DEF, and GHI. Each trio is repeated across a few tercets before moving on to the next one. At the beginning, ABC is repeated four times, followed by DEF four times, and so on. In the latter portion of the chant, the number of iterations diminishes. While the red notation is so clearly aligned with the acrostic, what determines the form of the black notation is less obvious. Why

four iterations of ABC at the beginning before moving on to DEF, rather than three or five or any other number? The reason for this is a second acrostic embedded within the first;

missus, the Latin gloss of the Greek

apostolus, is spelled out within

MARC

IALI

S APO

STOL

VS. This secret acrostic, which Hooreman does not seem to have been aware of, is articulated when the melody changes in the black notation, every four verses.

In medieval thought, written language was a visual form, as two-dimensional as a drawing (

Carruthers 1998), and spatial arrangements of language through acrostic and other forms of pattern poetry were ubiquitous. The carmina cancellataof Hrabanus of Maura (c.780–856), Frankish monk and scholar of renown, are an inspiring example of connections between shape and language, as are the acrostic frontispieces of the Beatus Apocalypses (

Higgins 1987). Ademar himself made use of advanced acrostic forms elsewhere; at the end of a poem to St. Eparchus, acrostics spell his name, Ademarus, three times into the final six lines of the poem (

Landes 1995). The difference between poetry and music is that language is similarly legible when read horizontally or vertically, whereas with music horizontality and verticality yield two entirely different things: melody and harmony. The task of composing a musical acrostic turns out to be quite a bit more complicated than what Hooreman called double-counterpoint; can one compose a chant such that every single one of its phrases can combine with any other and yield a plausible harmony?

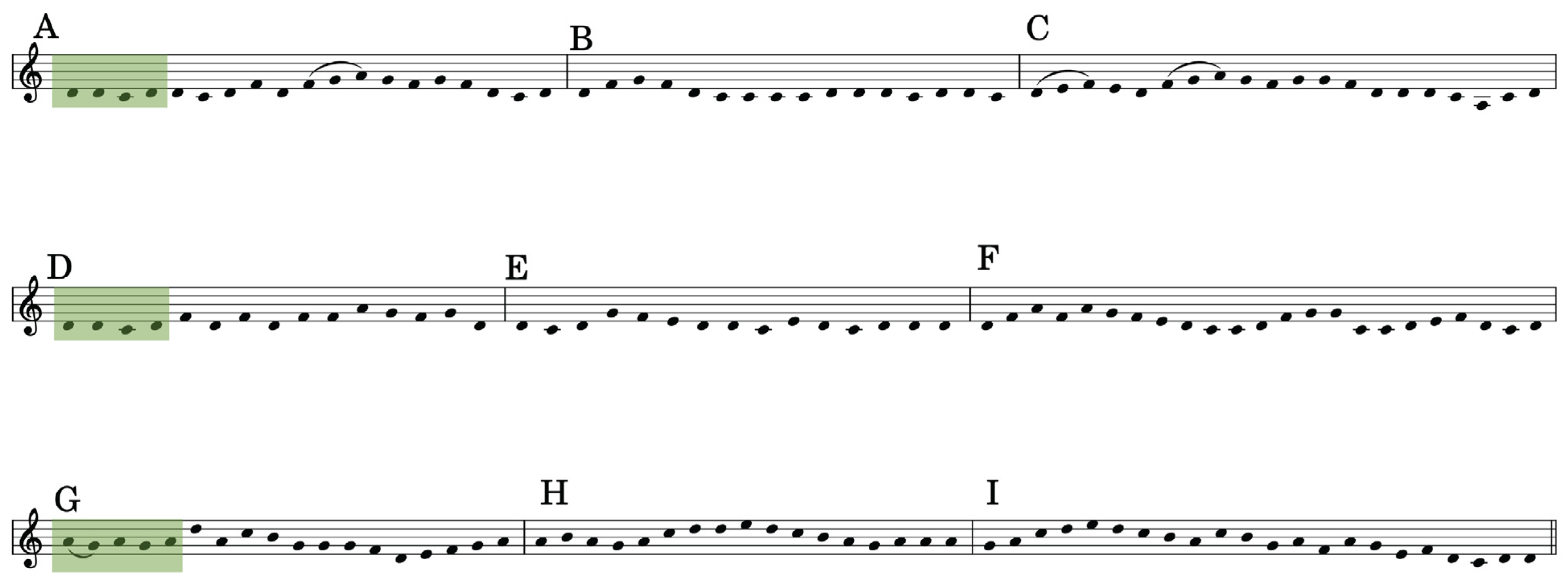

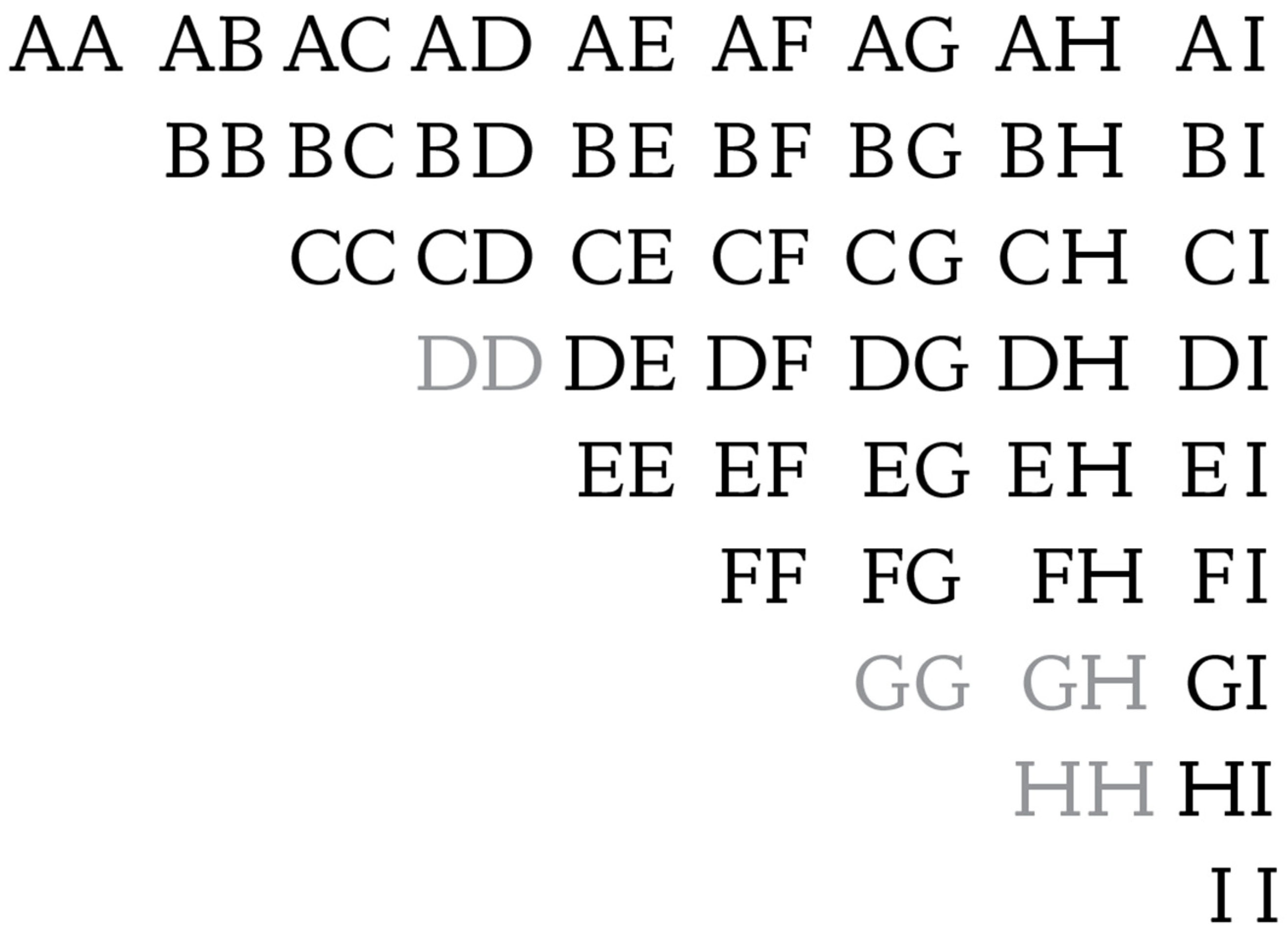

Ademar’s musical materials are economic, making use of only nine repeating melodies to set all 72 verses, labeled with letters A–I according to Hooreman’s convention (

Figure 10). These nine phrases form a prototype chant in the D-mode that, while complete in its own right, is never actually performed from beginning to end; the most we hear consecutively is six phrases. The red and black notations cycle through the phrases of this prototype chant according to two different patterns, causing them to overlap against each other in almost every two-part configuration (

Figure 11). Out of 45 possible combinations (36 polyphonic and 9 unison), 41 occur over the course of the chant. Only one of the unused combinations is polyphonic (G + H), with the rest being unisons (D + D, G + G, H + H). Restated another way, all but one of the 36 polyphonic combinations that can be produced by these nine melodies will occur at least once during a performance of the

72 Verses. Given the difficulty of this challenge, any seeming irregularities in the harmony might be considered with a touch of grace. The harmony does not seem haphazard or thrown together, as it might if the two notations were combined in error; perfect intervals predominate, and the imperfect ones are mostly nestled between the perfect ones.

Through the recombination of the nine melodies, the musical memorization task is kept to a minimum, while the sound is kept fresh by cycling through the harmonic combinations. This is one of the details that Hooreman missed in his monophonic analysis. He criticizes the form of the red notation for being

overly simple, noting that some of the phrases repeated in triplicate would be particularly awkward because their cadences have a strong sense of closure and would thus have the effect of prematurely ending, then beginning again, then ending again, and so on (

Hooreman 1949). Rather than assuming that the

72 Verses was a monophonic chant that was later revised to have a silly form, the polyphonic perspective is more compelling. As polyphony, the relationship between the two notations carries meaning and there are patterns to harness that would not otherwise be available.

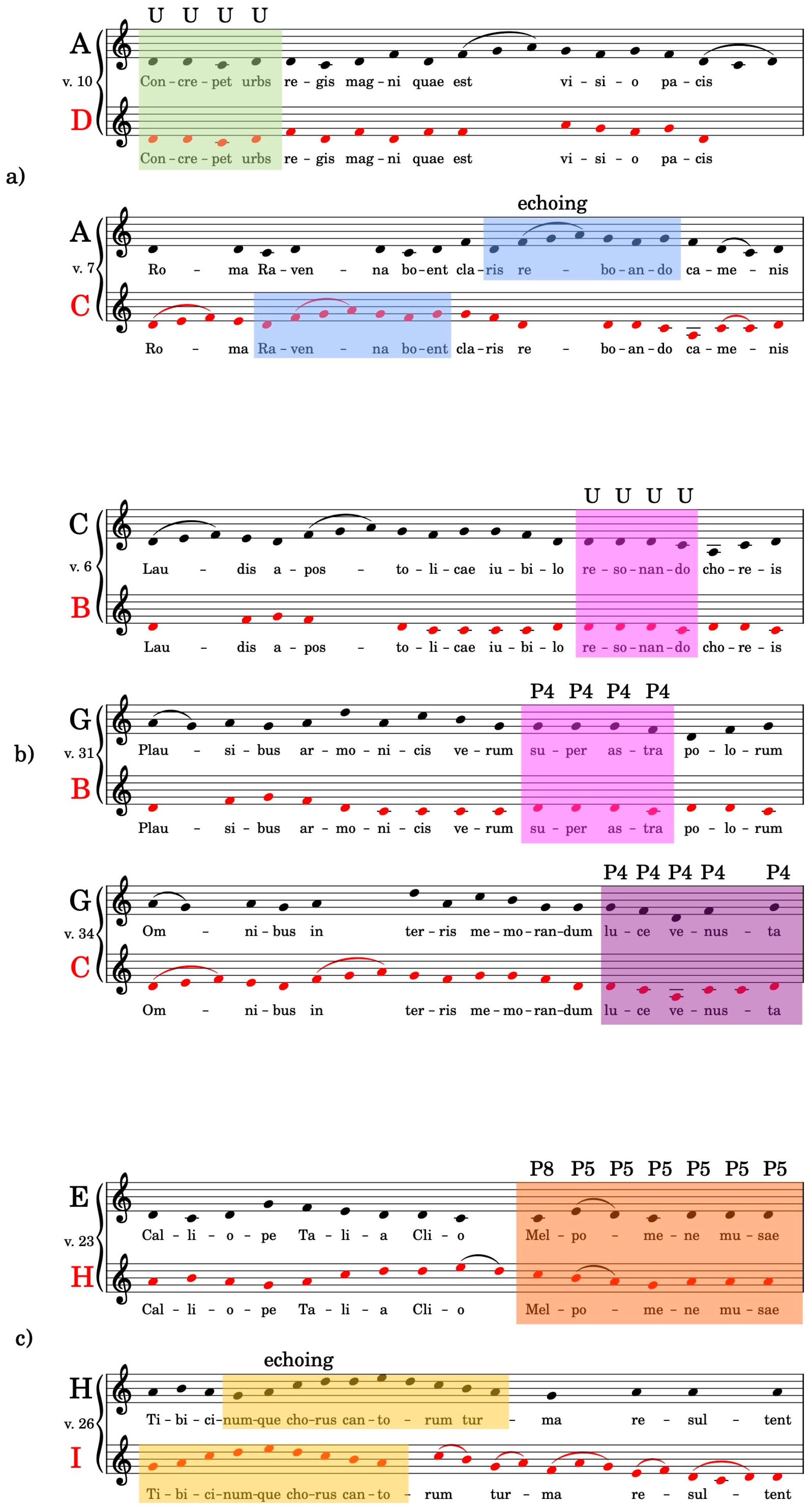

3. Analysis 2: The Polyphonic Structure Subdivides the Poetry into Eight Sections Situated on a Map

If the two notations were meant to be performed together, their coordination will leave a trace in the music (

Figure 12). One place to look to is strong, salient musical devices such as unisons, parallel motion, and echoing behaviors. When a unison occurs between the two parts, whether it be for an entire verse or for a brief melodic fragment, that moment rings out from the surrounding harmonic environment and calls attention to those words. Likewise with parallel harmony, because this polyphony has a lot of intervallic variation, a passage that suddenly snaps into parallel motion at the fourth or fifth will transform the sound.

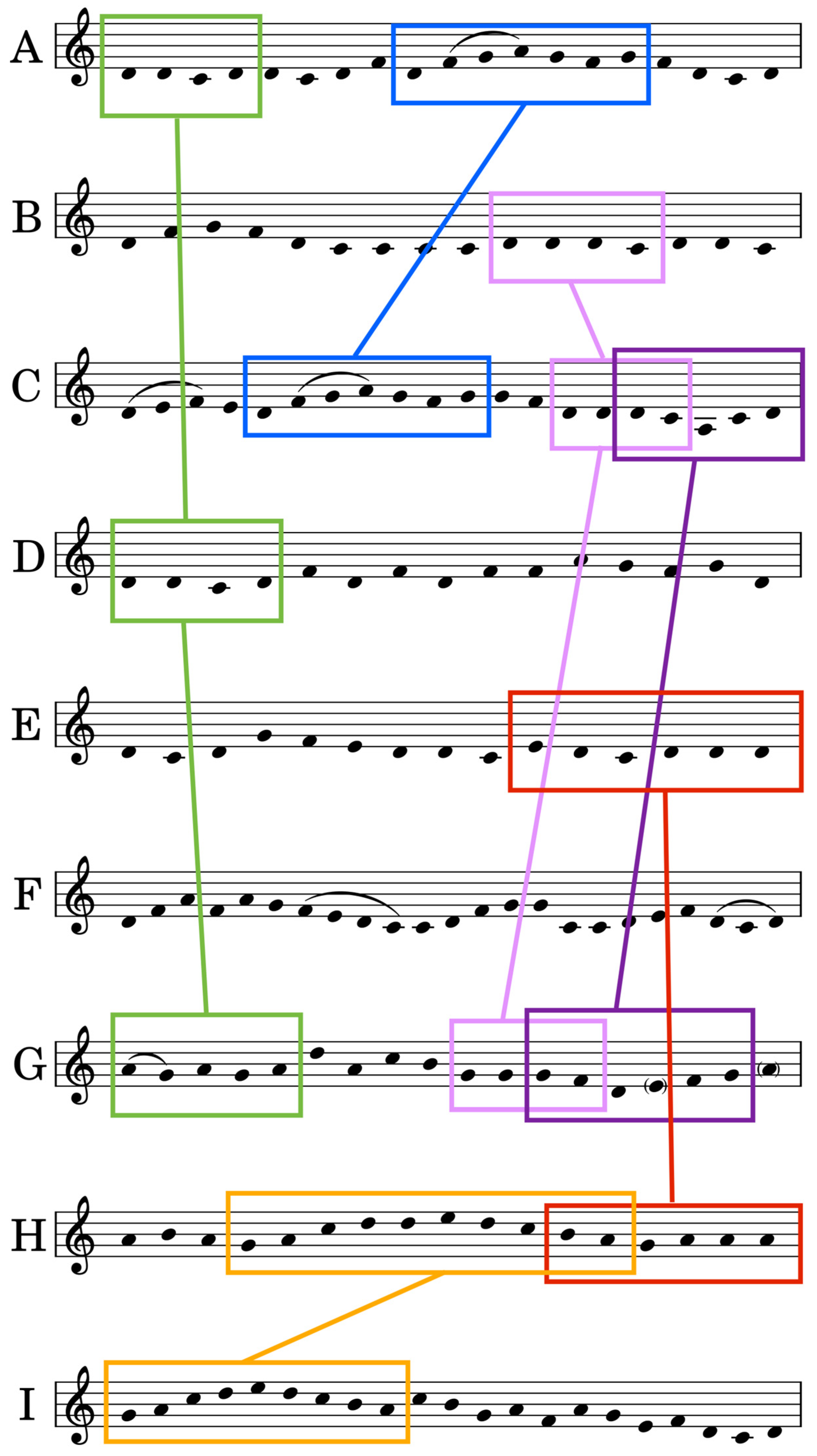

Looking at the prototype melody as a stack of nine individual phrases, it is clear that one of the ways Ademar “vertically” composed the prototype chant is by matching melodic fragments, like puzzle pieces that connect sections of different phrases to each other (

Figure 13). Ademar could then take advantage of the flexibility of Latin syntax to place words from the verse in positions that would interact nicely with the music. Phrase A, for example, forms a unison motif with Phrase D at the beginning of the melody and then in the middle echoes a fragment of Phrase C on the word

reboando, “echo”, of all words. Phrase C then forges further connection with Phrases B and G, yielding a unison with the former and a parallel fourth harmony with the latter in a melodic fragment that sets words such as

resonando (resound) and

super astra (beyond the stars). Similarly, most of Phrase H is an echoing of Phrase I, and then at the cadence, it moves in parallel fifths with Phrase E.

There is more to say about the unison that Phrase A forms with Phrase D. The nine-phrase prototype chant functions not only as a “horizontal line” (one unified chant melody) and a “vertical line” (a stack of phrases that combine into two-part polyphony), but also subdivides into a 3 × 3 grid, a square. Phrases ABC, DEF, and GHI subdivide the prototype chant into three subgroups that each begin with a common motif and end on a D cadence (

Figure 10). Groups ABC and DEF are quite similar, beginning with the motif DDCD, rising to

a, then descending for a cadence on D. Group GHI begins higher on

a, rises up to the apex pitch

e, then descends more than an octave to conclude on a D-cadence. It begins with the same opening motif, but set a fifth higher on (aG)aGA and with an added neighbor tone flourish on the first syllable, possibly to help tune the parallel fifth harmony that occurs when Phrase G coincides with Phrases A or D.

While some moments of unison or parallel harmonies may pop out as brief moments of word painting, such as resonando, some of these converging fragments take on a larger role as structural building blocks, which is the case with these opening motifs in Phrases A, D, and G. Whenever any of these phrases co-occur, their opening motif acts as an announcement, a call to attention. As it happens, a pairing of these phrases occurs exactly every nine verses, which subdivides the chant into eight equal sections. These eight sections correspond to eight locations situated on maps of the heavens and of Earth.

Just as with the secret

missus acrostic, Ademar uses music to highlight a covert feature in the language. The way that Ademar uses this musical motif to partition a linguistic structure is subtle and elegant. In location-based artificial memory practices, a succession of backgrounds, or loci, frame a collection of mnemonic images, creating a resonant mental presence that separates one idea from the next (

Carruthers 1998). In the same way, the DDCD musical motif separates the poetry into discrete sections without interrupting the flow of the poetry. As the poem progresses, the new apostolic story of St. Martial is narrated by moving to places on the map that were significant to the saint’s journey (

Figure 6). The story begins with a pilgrimage (Locus 1) from Gaul to Rome to Jerusalem. In every city, celebratory voices are joined by instruments and the clapping of hands in praise of St. Martial. After arriving in Jerusalem (Locus 2), scenes are depicted of Martial’s life: his parentage, baptism by St. Peter, and naming as apostle by Christ. The direction of the journey then pivots upwards, traveling through the celestial spheres (Locus 3), which are symbolized by the nine muses who join in the praise of St. Martial. The ascent through the celestial spheres culminates in Heaven (Locus 4),

super astra polorum (beyond the stars of [fixed] orbits), where choirs of angels sing the praises of St. Martial to all the earth, at the conclusion of the first half of the poem.

Crossing through the first half to the second half of the poem is a descent from Heaven to Hell (Tartara), directly above and directly below Jerusalem (Locus 5). St. Martial accompanies Christ to the underworld and receives the power of resurrection. Together, they return to Jerusalem, where Martial is also present at Pentecost, receiving the gift of tongues. He is sent out by Christ as an apostle to Gaul, but first travels with Peter to Antioch and Rome (Locus 6), before making his way to Gaul (Locus 7) where he converts King Stephen, former betrothed and beheader of St. Valerie. Having saved the people of Aquitaine, the poem ends with all of Heaven and Earth (Locus 8) singing the praises of Martial, apostle of Christ.

Hooreman was critical of the poetry, complaining that the

72 Verses had no overall cohesion and seemed rather like 72 individual verses, one after the other. And that if we did not know that the music and text were created by the same author, one might have assumed that the tercet groupings had been put there arbitrarily by some other scribe or musician (

Hooreman 1949). Without seeing the poetry in the context of these eight sections, it would be easy to come to such a conclusion, and the presence of the subdivisions is not immediately clear without looking at the polyphonic structure between the two melodies.

Another reason why Hooreman may have found the poem structureless is that the transitions from one section to the next are often well-concealed through poetic devices. Keyword repetitions, for example, create redundancies in the language that straddle one locus to the next. For the performer, picturing these eight background images as they move through the piece, the repetitions of keywords would help keep track of the order of the verses and connect the lyrics from one location to the next; but when viewed without that framing device, such repetitions might add confusion to the form instead of clarity. For example, the words “Hierusalem” and “regis” are mirrored across the transition from the first locus (ending with v. 9) to the second (beginning with v. 10). Since the first locus entails travel to Jerusalem and the second takes place in Jerusalem, there is a seamless transition that obscures the shift in the background. If one is not looking for it, it will be missed.

- 8 Hierusalem Nablis canat organa voce sonora,

- 9 discipulo regis, cui constat apostolus ipse.

- 10 Concrepet urbs regis magni, quae est visio pacis,

- 11 Hierusalem, quam restaurare Deus venit ipse,

-

- Jerusalem, Nablus, sing with polyphonous, melodious voice about

- the disciple of the King, who remained his steadfast apostle.

- The city of the great king resounds: a vision of peace.

- Jerusalem, which God himself comes to restore

- Translated by Bissera Pentcheva

“Dedit” (gave) functions in the same way at the transition from Locus 2 (Jerusalem) to Locus 3 (the celestial spheres), but as with the previous transition, there are confounding features to this one as well. Midway through the third locus, there is a symbolic shift from Biblical imagery to Classical that, at first glance, seems to disrupt the flow of this subsection. The imagery of verses 19–21 seems to better fit the preceding tercets about Martial in Jerusalem being named apostle by Christ. But in a clever sleight of hand, Ademar pivots from the Biblical to the Classical through “twelve lofty close attendants” that symbolize both the twelve disciples and the zodiac. Similarly, the mention of libra connects to notions of judgment from the preceding section, while simultaneously representing the seventh constellation of the medieval zodiac, Libra (which happens to be named in the seventh tercet). This pivot enables a shift in the axis; up to this point, travel along the mental map has been on the Earth, but at this moment, the motion pivots upwards through the celestial spheres.

4. Analysis 3: Numerological Cues in the Verses Position Icons around the Celestial Map

To complete this scene, the focus turns to the number seventy-two itself, which is biblically symbolic because Christ “appointed seventy-two others and sent them on ahead of him in pairs to every town and place where himself intended to go” (Luke Ch. 10:1). But beyond the significance of this number to St. Martial’s apostolic vita, seventy-two is interesting because it mathematically subdivides so many ways, including other traditionally symbolic numbers such as 3 (trinity), 4 (gospels and tetramorph), and 12 (disciples). There is ample opportunity to apply many geometric and symbolic meanings to the verse numbers, and the naming of the number in the title of the work reinforces its significance.

The numerological pivot from Biblical to Classical imagery in the seventh tercet performs several duties for the sake of the narrative, symbol, structure, and even a bit of humor. On the surface, the pairing of bissenos and septuaginto duo in verses 20–21 brings together the twelve original apostles and the seventy-two additional ones. These numbers also provide a structural clue that connects this passage to the halfway-point of the poem, as this same pairing appears again in verses 35–36 with numbers swapped: decies septem geminisque in v. 35 and bisseni in v. 36. This portion of the poem, from the seventh tercet to the twelfth, defines the boundaries of the portion of the chant that plays out on the celestial map. Together, all of these apostles may represent stars in the sky. Verse 36 also contains a pun, bisseni quoniam pauci rarique coloni (for twelve were too few), providing, on the surface, the suggestion that that seventy-two more apostles were called forth for twelve were too few. Yet simultaneously, this verse is the last one of the first half of the poem; apparently twelve tercets are also too few, so the poem is going to press on with twelve more.

- 19 Legaleque dedit sceptrum, ius officiumque,

- 20 inter bissenos proceres propioerriesentes

- 21 necnon septuaginta duo, quae est aurea libra

-

- Christ gave Martial a scepter of authority, legal power, and an office.

- Besides the twelve lofty close attendants, he added seventy-two, which is the golden balance.

- Translated by Bissera Pentcheva

-

- 34 Omnibus in terris memorandum luce venusta

- 35 fecit eum decies septem geminisque colonis,

- 36 bisseni quoniam pauci rarique coloni.

-

- Christ made Martial noteworthy in the entire world,

- setting him with a beautiful aura among the seventy-two servants

- for twelve were too few.

- Translated by Bissera Pentcheva

In another geometric arrangement, by subdividing the poem into quadrants, Ademar positions icons around the perimeter of the celestial background image (

Figure 7). Vertically, there is a descent affected through keywords that name Heaven, Earth, and the Underworld (Tartara) in close succession, straddling the halfway point of the chant. Imagery in the surrounding tercets describe icons that would be in these positions, above and below the celestial spheres. In Tartara, Christ gives St. Martial the power of resurrection, so we might envision the two of them at the bottom of the map. A few verses later, we then see Christ in Heaven with his right hand raised. On the mental map, this icon of Christ would be pictured surrounded by the angelic singing of the celestial hierarchy that was introduced in tercets X–XII.

Horizontally, there is a geometric link between verses that depict St. Martial and St. Peter, each seated on a throne (

Figure 14). The spatial arrangement of these verses in the overall poetic form places their icons to the left and right of the celestial map. The quarter-mark of the poem is the sixth tercet, verses 16–18, and it is here that St. Martial is given a throne by Christ. This act of enthroning is then exactly paralleled in the eighteenth tercet, the three-quarters-mark of the poem, when St. Martial enthrones St. Peter in Rome. With St. Martial as the one who places St. Peter upon the throne, Martial has been elevated to equal status with St. Peter. St. Peter was the first bishop of both Antioch and Rome, so the connections drawn across these three locations further elevate St. Martial with the suggestion that his enthronement as the bishop of Limoges was just as significant. These events are preceded by another symmetrical reference to St. Peter; in verses 13 and 49, exactly 36 verses apart from each other (halfway around the poem, so to speak), he is called “Prince Peter” in both instances.

- 13 In qua lavit eum Petrus baptismate princeps

- 14 carne propinquus ei, Beniamin stirpe creato,

- 15 Marcello Helisabeth genitoribus undique claris.

- 16 Ad sublimia apostolici quem culminis, in quo

- 17 culmine apostolico vexit soliumque thronumque

- 18 Rex et apostolicam dedit huic sedemque tribunal.

-

- In which Peter, the prince of the apostles washed Martial in baptism,

- to whom he is close in blood, conceived in the clan of Benjamin,

- whose parents, Marcel and Elizabeth, are each of illustrious descent.

- I say, Christ the king brought him to the sublime apostolic peak

- and gave him an apostolic seat and throne,

- and an apostolic position in the tribunal [Last Judgment].

- Translated by Bissera Pentcheva

-

- 49 Unde simul venit Siriam cum principe Petro,

- 50 cui comes indisiunctus erat, quo nempe rogante

- 51 semina spargebat fidei linguis populisque.

- 52 Sed post romulidas adeunt, tum pontificali

- 53 sede Petrum Marcialis apostolus ad Lateranos

- 54 cum Lino, Cleto senioribus inthronizavit.

-

- At a certain point, he [Martial] came to Syria with Prince Peter,

- whose inseparable companion he was, and at his bidding

- he would sow the seeds of faith to all people and languages.

- And afterwards when they went to Rome,

- then apostle Martial enthroned Peter on the seat at the Lateran

- together with his seniors, Linus and Cletus [patriarchs of Athens].

- Translated by Bissera Pentcheva

The naming of St. Martial as an apostle and his enthronement intersects narrative and mathematical structures (

Figure 15). By positioning this moment of Christ’s blessing in the sixth tercet, Martial is simultaneously in Jerusalem, according to the poetic locus, and at verse 18 of 72, i.e., the quarter-mark. Zooming in on the musical details in this tercet, melody and poetry also work in concert with these other structures. The significance of this moment in which he is named as an apostle is reflected in the poetry, which goes out of its way to say apostle three times, once in every verse. Musically, Phrase F dominates this tercet (verses 16–18); the red notation repeats FFF, and the black moves through Phrases DEF, creating the unison F + F in verse 18. Among the nine phrases, melody F has the unique feature of a four-note descending melisma, the longest melisma in the chant. For every occurrence of melody F in this tercet, a version the word “apostle” is set on this melisma. Through this moment, the poetry can be seen as separate from the narrative; the threefold repetition of “apostle” is not required for the telling of the saint’s vita, but by intersecting the geometric and narrative structures, Ademar harnesses the minute details of the music and poetry to reinforce the iconography of St. Martial the apostle.

The unison melody F + F occurs a second time at the conclusion of the chant, setting verse 72, and here again, “apostle” is placed on the same melisma. This time, the event is made even more florid by a notational twist, the only such moment this chant; Ademar offsets melody F against itself, creating polyphony in the middle of the melody, on the naming of “apostle”. The two melodies begin and end in unison on “Christo cuius” and “eon sine fine” but branch apart in the middle, yielding polyphony as Christo cuius apostolus est per eon sine fine. In the two notations, the melisma follows on two different syllables, creating an echo, one following right after the other. Thus, through a combination of number, music, and text, the sixth tercet is drawn into connection with the twenty-fourth. The sixth tercet emphasizes the icon of the enthroned St. Martial, while the twenty-fourth then places St. Martial in the center of Heaven and Earth.

5. Analysis 4: Composing the Narrative Climax with Melodic Shifts and Symbolic Errors

Up until this point, I have discussed cases of harmonic alignments between phrases without acknowledging how the length of each verse can complicate this process; because the syllable count is not consistent from verse to verse, the nine melodic phrases must be adapted to fit each verse individually. This is usually achieved by increasing or decreasing the number of repetitions of a pitch in the middle of the melody or by changing the grouping of pitches by either slurring a pair of pitches or separating them out. A change as subtle as shifting one pitch in one phrase will have major consequences regarding the harmony it produces with its polyphonic counterpart. This raises the question: is there evidence that the melodic adjustments in the red and black parts that accommodate the text setting were made with an awareness of each other?

Melody E, for example, begins with the notes DCD throughout the entire chant, with the exception of the twenty-third tercet, verses 67–69, when it is changed to the DDCD motif, forming a unison with Phrase A (

Figure 16). There are two prior instances in which Phrases A and E coincide in verses 43 and 56 that did not create this same unison, because in those cases, Phrase A begins DDCD and Phrase E begins DCD, offsetting the harmonic combinations for the entire phrase. So, why in verses 67–69 the difference, was this intentional? In order to answer this question, there is a complex convergence of melodic materials in the verses leading up to this moment that needs to be explained.

Phrases A and D, as has been discussed, together form the unison motif DDCD, and they are performed together at four points in the chant: verses 10, 37, 55, and 64. Every time they co-occur, they begin with these four notes in unison, and as the chant progresses, the number of unison pitches they share increases. For verses 10 and 37, they are in unison for the expected notes of the DDCD motif. (Verse 37 is also the first verse of the second half of the poem, so the unison motif here has the added effect of “starting over” by briefly referencing the unison opening of verse 1, before diverging into harmony.) The third time, in verse 55, an extra D is added to the end of Phrase D’s opening motif: DDCDD. The addition of this note offsets the harmony, resulting in a longer unison between the two. As a result, nine of the first ten notes are in unison, with the only exception being a perfect fourth in St. Peter’s name, Petrus. That perfect fourth then resolves to a unison in the fourth and final instance of A + D, and with it, the name has been changed from Peter to Christ. Thus, through subtle shifts in pitch, the two melodies become perfected through their repetitions, with the final act of perfection achieved by Christ in verse 64.

The narrative climax of the poem occurs at this exact moment, across verses 63 and 64, straddling the twenty-first and twenty-second tercet. At this point, St. Martial has arrived in Gaul to save King Stephen and all the people of Aquitaine. King Stephen, a fictionalized foe from the Vita prolixior, is rendered powerless through an act of syntax; by depriving the twenty-first tercet of a verb, verses 61–63 become dependent upon the first words of the next tercet, “Subdiderat Christo” (subdued to Christ), for their completion. (I thank Bissera Pentcheva for sharing with me this observation about the missing verb in tercet XXI.) Thus, King Stephen has been converted and St. Martial has fulfilled his mission, all symbolized in a laconic, grammatical act of submission.

Parallel to this grammatical “error” is another “error” in the musical form that also straddles verses 63 and 64. According to the polyphonic formal pattern, the black melody at verse 63 ought to be Phrase I, but instead the notation gives a variation of Phrase C that is transposed up a fifth (

Figure 16). Hooreman was confident enough that this difference was a scribal error to “correct” the form of the black notation from GH

C to GH

I in his analysis. But again, in a polyphonic context, this deviation of form makes sense and even incorporates the notion of error into its symbolism; replacing Phrase I with this variation of Phrase C sets up a parallel fifth passage with Phrase C in the red notation. Then, when poetry arrives at the verb, “Subdiderat Christo”, the music suddenly shifts to the perfected A + D unison passage described above. The juxtaposition of the parallel fifth harmony in verse 63 with the lengthy unison at the beginning of verse 64 forms a lengthy passage that is sonically unique in the chant. In other words, this melodic “error” coincides with the syntax “error” at the narrative climax of the chant, and together, these “human” errors communicate that, even when it is the apostle who fulfills the mission, it is Christ who is glorified above all.

Finally, following this glorious moment of coordinated submission, we can look back to melodies A + E in verse 67 and investigate whether their unison motif is intentional. Subdiderat Christo begins with the DDCD motif, and for the next six verses, this motif will continue to repeat in at least one of the notations. Thus, when A + E together sing DDCD, the unison motif continues insistent repetition, and Phrase E continues to carry the torch of the DDCD motif through the entire tercet. The effect is an echoing of Christ’s triumph from verse 64. Thus, the power of the DDCD motif, the very first sounds heard in the 72 Verses, is ultimately connected to submission to Christ, and as that sound is echoed through the final verses, it brings about a sense of closure and fanfare.