Abstract

This article positions queer nightlife as a central vehicle in the lives and practices of queer Latinx artists working in Los Angeles over the past decade. It highlights how queer nightlife has provided a generative space for art making and community building in LA and considers how the usage of queer nightlife as a frame of study ruptures existing art historical and curatorial methodologies relative to Latinx art. I closely analyze works by artists rafa esparza, Sebastian Hernandez, and Gabriela Ruiz drawn from the gay bars and streets of downtown and East Los Angeles to underscore the radical and sophisticated ways by which these artists create art, community, and opportunity. By critically examining three case studies—Escandalos Angeles (2018), a performance by Hernandez and Ruiz at Club Chico in Montebello, California; Nostra Fiesta (2019), a storefront mural by esparza, Ruiz, and friends at the New Jalisco Bar in downtown; and YOU (2019–ongoing), a queer party directed by Hernandez and launched at La Cita Bar in downtown—I reveal how queer nightlife has served as an incubator for these artists to come together, express themselves, and generate a sense of joy and freedom from the struggles of everyday life.

“Look at the history of queer performance. Much of it was not considered art for a really long time, in part because it emerged in community spaces and gay bars. Spaces that were, we might say, breaking-off spaces rather than bridging spaces. You can’t understand its qualities without understanding the communities from which it emerges.”(Doyle in Christovale and Ellegood 2018, p. 111)

1. Introduction: Queer Nightlife as Incubator

On 22 April 2018, the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (ICA LA) opened rafa esparza: de la Calle, an exhibition of art, fashion, performance, and nightlife cultures encompassed in esparza’s hand-made adobe brick slabs which covered the gallery’s floor and walls (Figure 1). Hosted in the ICA LA’s project space, the exhibition was billed as a work in progress, a simple yet dynamic presentation that would shift over time as esparza and a group of friends and artistic collaborators would use the gallery as a showroom, workroom, and studio for their practices. Collaborators included fashion designers Victor Barragán, Joshua Castillo, Tanya Melendez, and Oscar Olima and visual artists Fabian Guerrero, Sebastian Hernandez, Young Joon Kwak, Dorian Ulises Lopez, noé olivas, and Gabriela Ruiz, among others, who collectively produced and staged new drawings, paintings, sculptures, garments, accessories, and performances throughout the exhibition’s run. Their creative output provided an intimate glimpse into a topology of diverse but similarly minded artist’s practices, emphasizing intricate intersections among nightlife, art making, performance, and fashion design in Los Angeles.

Figure 1.

Exhibition view, rafa esparza: de la Calle, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 15 June 2018, photo by the author.

de la Calle shed light on a queer of color network of artists and cultural producers working in dialogue with one another. This network, comprising individuals who draw upon shared artistic and cultural experiences as creative Angelenos working in and from the city, has been active over the past decade within art, fashion, and nightlife underground circuits. As an exhibition, de la Calle is just one of a recent suite of gallery, museum, and public art projects since 2014 where esparza presented work in dialogue with others, and the exhibition gestured to the notion of him as a member of an artistic community whose practices come from, and perhaps make most sense outside of, something other than the mainstream art world.1 While de la Calle did not mark this outright, nor did the exhibition’s didactics historicize the artists’ practices within a legacy of art, performance, or nightlife in the city, esparza and his collaborators nevertheless created a group of artworks that spoke to these myriad of influences and left the door open for how we might begin to consider, or reconsider, our understanding of their work.2

This article seeks to pick up where de la Calle started, or rather, to tell its story, not in art world terms but actually “from the streets” and through the urban works of the artists themselves. In this article, I position queer nightlife as a central vehicle in the lives and practices of this artistic network and seek to answer the following questions: How has nightlife provided a generative space for art, performance, and community building in LA? And how does centering nightlife in the study of contemporary art and cultural production rupture existing art historical and curatorial methodologies relative to queer Latinx art and performance?

I closely analyze works by artists rafa esparza, Sebastian Hernandez, and Gabriela Ruiz drawn from queer nightlife contexts—particularly the gay bars and public spaces of downtown and East Los Angeles—to underscore the radical and sophisticated ways by which these artists create art, community, and opportunity for themselves and their collaborators. The three artworks of focus are Escandalos Angeles, a performance by Sebastian Hernandez and Gabriela Ruiz at Club Chico in Montebello, California; Nostra Fiesta, a storefront mural by rafa esparza, Gabriela Ruiz, and friends at the New Jalisco Bar in downtown Los Angeles; and YOU, a recurring queer party directed by Hernandez and launched at La Cita Bar in downtown Los Angeles. Through these examples, I argue that nightlife has served as an incubator for queer Latinx artists in Los Angeles to come together, express themselves, and generate a sense of joy and freedom from the struggles of everyday life. The critical site of the bar, club, or underground party is where survival and play intersect, and it is in these unique places where creativity is fostered and the production of new artworks can be realized.

2. Why Queer Nightlife?

Queer nightlife studies as a field of study has had a rather rocky or unpredictable start. Significant scholarship has been authored by faculty and researchers of music, popular culture, sociology, history, queer theory, and performance studies, whose innovative projects have at times faced marginalization by elitist institutions and academic departments deeming it too “ethnographic” or “low prestige” (García-Mispireta 2023, p. x).3 The field has also been predominantly white- and male-focused, mirroring the hegemonic and demographic makeup of many gay bars and queer spaces themselves (Hilderbrand 2023, p. xviii). However, key early projects in the late 1990s and early 2000s, such as Delgado and Muñoz Everynight Life (1997), Ingram, Bouthillette, and Retter Queers in Space (1997), and Buckland Impossible Dance (2002), have focused on the nightlife cultures and experiences of women, immigrants, and queers of color beyond Euro-American frameworks, providing reference points for scholars to open new avenues in the field. Since 2018, there has been a proliferation of book-length projects focused on the histories, cultures, and relevance of queer nightlife that emphasize a range of topics and perspectives.4

This article contributes to this highly dynamic and interdisciplinary field by prioritizing a focused discussion on the arts—that is visual art, performance art, and public art.5 As the late scholar–activist Horacio N. Roque Ramírez recognized through his oral history work and queer Latinx nightlife experiences in Los Angeles and San Francisco, it has long been the arts and creative organizing within gay bars that has helped to build community, raise consciousness, and fundraise around important LGBTQ+ issues (Roque Ramírez 2003). For example, the arts played an important role in Latinx gay bars of the 1990s and early 2000s, where theater and performance acts effectively engaged audiences and promoted positive messages about HIV prevention and sexual health education (Roque Ramírez 2007, pp. 287, 290). Acknowledging these histories underscores the longstanding and multifunctional role that queer nightlife has played in society and helps ground my study of the relationship between queer nightlife and contemporary art today.

I am interested in thinking deeply about how and why visual artists realize their creative ideas born in and from queer nightlife, and my detailed analysis of selected artworks crosses in and out of art history to speak to larger discussions of queer social spaces, artist networks, and the very frameworks we use to understand artistic and cultural practices.6 While I myself am trained as an art historian, I assert that art history alone cannot tell the story of esparza, Hernandez, and Ruiz’s individual and collective practices, and I recognize how the field’s investments in centering individual achievements and linear narratives can be limiting.7 For example, due to his visibility through various performances, exhibitions, and public art projects, esparza has consistently received solo requests and invitations by arts organizations, but in an effort to center his community, he has often elected to invite collaborators to reshape the otherwise individual-centric structure of each project. While esparza’s collaborative efforts have resulted in dynamic and community-driven projects (such as the exhibition discussed in the introduction), they have commonly started with a personal invitation that he pushed back upon and adjusted to his and his collaborator’s own terms.8 The art historical and curatorial focus on the individual (drawn from European tradition) can be useful to develop a deeper understanding of a specific artist, their biography, and their practice, but it must be challenged as the prevalent model, for it has sidelined and misunderstood both the individual and collaborative practices of women, people of color, and queer people. Furthermore, for esparza, Hernandez, and Ruiz, who understand themselves in relation to hemispheric, ancestral, and collective bonds, it is imperative to examine and contextualize their work through these same lenses, crossing out of art history and into other sets of knowledge or into the physical places of the nightclub, dive bar, backyard party, or streets themselves to reveal how they influence and collaborate with one another.

My study of queer nightlife and contemporary art emerged from friendships and collaborations that have burgeoned inside and outside of queer nightlife contexts over several years, notably manifesting in Liberate the Bar! Queer Nightlife, Activism, and Spacemaking (2019), an exhibition that I curated with Paulina Lara and that featured newly-commissioned artworks by esparza, Hernandez, Ruiz, and others (Figure 2).9 The exhibition and event series left a profound impact on me and motivated me to think about the manifold ways that the queer Latinx experience in nightlife has shaped the production of new visual art and performance. Each case study in this article is articulated from a point of view that calls upon varying degrees of first-hand or second-hand knowledge. Through memory, storytelling, interviews, and formal analysis, I write about these nightlife moments and extrapolate meaning across disciplinary fields and local, regional, national, and international contexts.10 If I attended and/or contributed to a nightlife moment, as in the case of the Nostra Fiesta mural at the New Jalisco Bar, I write from a first-person point of view and supplement my account with informal interviews from friends and other participants. This type of conscious/unconscious oral history of sorts became part of my methodology long before I had even recognized it as such. For YOU, a recurring party, I write exclusively about the nights that I physically attended and supplement my writings with knowledge drawn from conversations with Hernandez and other members within this network, as well as from the party’s official Instagram page. Social media also factored into my interpretation of Escandalos Angeles at Chico, as I did not physically attend the event but instead watched a large portion of the performance on Instagram live, in addition to reviewing photo documentation and interviewing participants involved. Throughout this article, I consider queer nightlife as its own method and frame of study (Adeyemi et al. 2021, p. 10) that allow us to see not only aesthetics but also the social, cultural, and political investments of these artists and their peers.

Figure 2.

Exhibition view, Liberate the Bar! Queer Nightlife, Activism, and Spacemaking, on view at ONE Gallery, West Hollywood, 28 June 2019–20 October 2019, photo by Monica Orozco. esparza and Ruiz’s art installation, right, replicates elements of the New Jalisco Bar’s interior and showcases the duo’s mural within the embedded TV monitor. The work on the left is by Dulce Soledad Ibarra.

In Los Angeles, queer nightlife can be examined through numerous vantage points, but for the purposes of this article it is both strategic and illuminating to employ what performance scholar and theorist Meiling Cheng has identified as a “multicentric” understanding of place, recognizing how the cultures of each neighborhood across the region contribute to a kaleidoscopic view that challenges any master narrative formation (Cheng 2002, pp. 67–68). This multicentricity also troubles the impulse to place queers of color within an urban/suburban binary, pushing us to revise our sense of where we might locate queer Latinx art, sociality, politics, and desire and how groups might traverse across both urban and suburban contexts.11 Los Angeles’ queer nightlife circuits—its bars, nightclubs, underground parties, and post-partying escapades—offer a lot to think about in terms of residents’ relationship and access to the city’s public space.12 For the Chicano generation of the 1960s and 1970s, access around the city was limited and policed, especially for those who resided in East Los Angeles.13 Over time, queers of color would carve their own paths outside of their siloed communities, regardless of the risk of harassment or exclusion, with many piling in and making their own spaces within nightlife.14 These venues should not be romanticized, though, as their collective history is fraught, from the criminalization of gay bar clients and owners in the early 1950s to de facto discrimination practices of dress-codes and admission policies aimed at preventing people of color from entering the doors. The 1970s and onward saw the rise of culturally-specific nightlife networks across the city, with each network contributing to the city’s multicentric nightlife landscape and percolating into music, theater, film, and art worlds.15

For the queer Latinx artists considered in this article, it is important to highlight a very particular set of nightlife venues and histories, and the people who have contributed to them, to set the context for the importance of queer nightlife for this group. In many ways, the artists and their queer nightlife network was born and nurtured through the life and work of the late Ignacio “Nacho” Nava Jr., co-founder of the nightlife recurring party Mustache Mondays, a “centrifugal force” (Donohue 2019) who ignited downtown Los Angeles with his cultural leadership and contributions to the city’s queer underground and experimental club scene and who brought together a constellation of creative, like-minded individuals who contributed to the party and each other’s livelihoods and artistic practices. Nava frequented a variety of queer nightlife venues in Los Angeles, from Arena Nightclub and Circus Disco in Hollywood to Latinx-centric venues such as the Mayan, Plaza, Tempo, and The New Jalisco Bar (Lara 2019, pers. comm.).16 He experienced and observed how each nightlife venue contributed something unique to the city’s queer of color landscape, and in September 2007, Nava, alongside Danny Gonzalez, Josh Peace, Dino Dinco, and friends, established Mustache Mondays in downtown. Mustache was the group’s take on queer nightlife done right, operating in opposition to the stuffy and predominantly white, gay, and male venues of Hollywood and West Hollywood, and over the course of a decade, the recurring party pushed nightlife boundaries with its diverse and legendary lineup of DJs, music performances, lighting and set designs, performance art, flyers, and merchandise, all contributing to providing space for so many different members of the city’s queer and transgender communities to come together (Bieschke 2017).17

Mustache Mondays, active from 2007 to 2018 in downtown Los Angeles, served as a vital convening space and incubator for artistic experimentation, socialization, and community building in Los Angeles (Valencia 2023, pp. 90–91). For Hernandez and Ruiz, who largely developed as performance artists in queer clubs and parties, queer nightlife has been formative in shaping their sense of community and refining their artistic practices.18 Indeed, throughout its ten-year run, esparza, Hernandez, and Ruiz would be pulled into some aspect of Mustache programs and operations, from working the door to performing as a featured artist to helping design flyers and/or promote one of the nights online. Nava’s visionary work provided a consistent platform for esparza, Hernandez, Ruiz, and so many others to experiment creatively while also fostering the type of community that allowed for these experimentations to debut within a welcoming and generative environment. Furthermore, Nava’s investment in those around him extended well beyond these critical nightlife moments, spilling over into the everyday of working and socializing, establishing an ethos of care and support that would become central to the networks of people who knew and worked with him. For those who knew him, there is without a doubt a sense of commitment to his legacy and the continuation of his work through the collective efforts that he led by his own example. Therefore, for this network, I understand collaboration and collectivity (staying together and working together) as powerful modes that help to facilitate the creation of new artworks while simultaneously operating as an homage to Nava—to process his loss and to continue to express creativity and joy as disparate pieces that form the whole.19

3. Escandalos Angeles (2018)

I take us back to the summer of 2018, on the Eastside, at a bar located on the corner of Beverly and Garfield in Montebello, California. The façade of this small but mighty nightclub is spray-painted black and adorned with the word CHICO in bright gold capital letters. This Friday night is a special occasion, as artists Sebastian Hernandez and Gabriela Ruiz are scheduled to debut a new performance at an event curated by Raquel Gutiérrez as part of the queer film and event series Dirty Looks: On Location (Figure 3). The organizers of this series collaborated with local artists, performers, bar owners, curators, and scholars to uncover and showcase the multiple people, places, and histories that have formed the region’s queer cultural landscape (Nordeen 2018). For this event, Escandalos Angeles, Hernandez and Ruiz would pay homage to performance artist Robert Legorreta and the East Los Angeles barrios that birthed his “Cyclona” persona.20

Figure 3.

Raquel Gutiérrez speaks next to a TV monitor with Cyclona imagery, as part of Escandalos Angeles, Club Chico, Montebello, California, 13 July 2018. Reproduced with permission from Amina Cruz.

The walls of this small and crowded venue are lined with booths and tables (and the bar), and, for this event, the television monitors that hang on each side of the venue’s back wall broadcasted images of Legorreta fashioned in his signature “Cyclona” garb—a hand-made gown and whitened face with elaborate eye makeup and a red-lipsticked mouth. Born in El Paso in 1952 and raised in East Los Angeles, the artist is most known for his public interventions taking place when he was a student in the 1960s at the local campuses of Garfield High School and California State University, Los Angeles and throughout the streets that wove through Whittier Boulevard. These interventions, whether individually or collectively enacted, often sought to disrupt the closed-minded character of the city’s Chicano public sphere.21

At the event and through its digital and printed promotional materials, Legorreta was positioned as a vanguard of the performance world, both inside and outside of Latinx contexts. In their essay on the history of Southern California performance, Suzanne Lacy and Jennifer Flores Sternad emphasized Legorreta’s vanguardism, noting that although the artist’s in-your-face strategy was typical for those working in performance, Legorreta’s public interventions during the late 1960s marked a shift from private to public audiences that would not be explored by other artists in the region until well into the 1970s (Flores Sternad 2006, p. 475; Flores Sternad and Lacy 2012, p. 90). In preparation for the performance, Hernandez and Ruiz conducted research on Legorreta at ONE Archives at USC Libraries, one of the largest repositories of LGBTQ materials in the world (Ruiz 2018, pers. comm.). Taking from their existing knowledge and research of the artist, Ruiz and Hernandez sought to pay homage to Legorreta by creating a performance that employed non-normative gender roles and desire and the artist’s signature in-your-face sensibility, while also critiquing the government rhetoric around Mexican and Central American immigrants that was increasingly prominent during the summer.

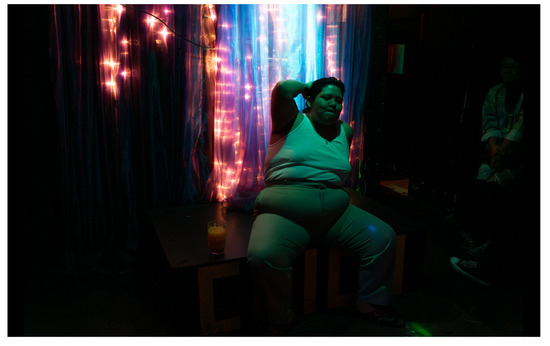

The performance opened with an audio track; the voice of Donald Trump echoed through the bar: “These aren’t people. These are animals.” The audio was taken from a May 2018 White House meeting with conservative mayors and officials from California who had opposed the rise of sanctuary city policies being implemented across their state (Korte and Gomez 2018). Ruiz entered the space, sat down, and listened to the track (Figure 4). She wore a white muscle shirt with khaki pants, channeling what cultural theorist Richard T. Rodríguez has called a “queer homeboy aesthetic”, a rearticulation of Chicano working-class masculinity: bold, dominant, and taking up space (R.T. Rodríguez 2006). With her legs spread apart and her arms behind her head, Ruiz listened to the audio track and became possessed by its sound and message. She began to demonstrate animalistic behaviors, including aggressive facial expressions, grunting, and growling.

Figure 4.

Gabriela Ruiz performs as part of Escandalos Angeles, Club Chico, Montebello, California, 13 July 2018. Reproduced with permission from Amina Cruz.

Hernandez jumped into the space with an equally dynamic response to the audio (Figure 5). Serving as Ruiz’s femme counterpart, Hernandez wore a navy tube top and black mini skirt with a long silver chain belt. For the next several minutes, the artists would circle each other and attack one another, wreaking havoc throughout the bar. This chaos and subversion of traditional Chicano gender roles overlaid with important aspects of Legorreta’s work, as the artist insistently rejected the characterization of himself or his Cyclona persona as male, female, masculine, or feminine (Flores Sternad 2006, p. 478).

Figure 5.

Sebastian Hernandez performs as part of Escandalos Angeles, Club Chico, Montebello, California, 13 July 2018. Reproduced with permission from Amina Cruz.

Music played throughout the performance, with each song dictating Hernandez’s and Ruiz’s movements. “San Cha started playing and Sebastian tried to seduce me”, recalled Ruiz (Ruiz 2018, pers. comm.). The music of the Chicana songstress evoked drama and love and ceased the duo’s animalistic behaviors.22 The performance then shifted into a love story and an elaborate courtship, as Hernandez danced around Ruiz and offered her orange foods such as Cheeto puffs (another blow to Donald Trump) in an effort to seduce her. Once Hernandez had successfully seduced Ruiz, the frenetic performance ended with the cutting of a beautiful pink sheet cake—one that read CYCLONA POR VIDA (CYCLONA FOR LIFE) (Figure 6).23

Figure 6.

Cutting into the Cyclona cake as part of Escandalos Angeles, Club Chico, Montebello, California, 13 July 2018. Reproduced with permission from the artists.

As a performance, Escandalos Angeles reveals artistic strategies of collaboration and site-responsivity that are central to the artists’ practices. This thoughtful consideration of a particular site’s location, history, and contemporary significance has served as a foundation for many of their visual artworks and performances.24 This performance in particular is deeply informed by its context: Club sCUM night at Chico. Founded in 1991, the Montebello bar was noted for its role as a gathering site for Chicano homeboys. Chico was recognized as a historic space for “men desiring men who adopt the homeboy aesthetic, as well as for those who seek it out for pleasure” (R.T. Rodríguez 2006, p. 131). Today the bar has changed in some regards. It now bills itself as “The Best Latino Gay Bar in Los Angeles”, expanding beyond its “homo-homeboy” clientele to cater to the broader Latinx community in and beyond Los Angeles. Between 2016 to 2020, Chico was also the home of Club sCUM, a monthly “punk/camp/trash/rock en Español night”, providing space for a new clientele who might never have felt welcome within the bar in the past (Dinco 2017). This dichotomy of past and present Chico, of homeboys and punks, formed pillars of inspiration for Hernandez and Ruiz’s performance via Ruiz’s clothing, their sCUM audience, and the evocation of Legorreta, who had moved through proto-punk and cholo scenes of the 1960s and 1970s inside and outside of nightlife.25

The performance also reveals the artists’ investment in knowledge sharing and commemorative acts. Through performance, Hernandez and Ruiz transform their nightlife context to an environment that can consider gaps and losses of knowledge within queer communities of color, particularly the way that a figure such as Legorreta could be improperly historicized and/or might be fading from the public imaginary. By invoking the performance practice of Legorreta, Hernandez and Ruiz not only aligned themselves with the vanguard artist but also re-centered his legacy for a twenty-first century queer of color audience.26 The performance’s queer bending of time, stepping out of Western and hetero-patriarchal linearity to bring Legorreta’s past performances to the present moment, signals that the present is not enough for queers of color, that it can be altered and collapsed through art and queer and ancestral ways of being, and that these modes can be used to raise awareness of an issue or to commemorate someone.27 In its most radical sense, the knowledge sharing and commemoration in Escandalos Angeles operates as a counter memory-making process against the hegemonic canon. Amidst the backdrop of gentrification and the shifting landscapes of Los Angeles, the rolling back of federal protections for queer and transgender individuals, and the increased negative rhetoric and criminalization against Latinx individuals across the United States during Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign (2015–2016) and subsequent administration (2017–2021), the celebration of queer of color working-class cultural heritage and legacy was a radical act—one tied to survival where artists and participants could move forward with a present relationship to the past.

4. Nostra Fiesta (2019)

When you drive or walk up South Main Street in downtown Los Angeles you will pass by a bright pink storefront mural on your left-hand side between Third and Second Street. This mural by rafa esparza, Gabriela Ruiz, and friends marks the location of the New Jalisco Bar, a nightlife institution with a deep history in the city spanning decades of family ownership and a series of name revisions. Jalisco is one of the longest-standing Latinx bars in the city, and over its lifespan it has become recognized among its clientele as a stronghold for those seeking to enjoy Spanish-speaking drag queens, sexy male go-go dancers, endless beer buckets, and no cover charge (Travel Gay 2018). esparza, Ruiz, and friends have frequented the bar for years, finding solace and community within its first-generation Latinx and immigrant-centric environment.28

In April 2019, during a visit to the New Jalisco Bar, curator Paulina Lara was asked by the bar’s owners if she knew of any artists who might want to repaint the bar’s exterior. Lara was at the bar that night with Ruiz and mentioned to the owners that Ruiz was in fact an artist. Interested in learning more, the owners asked if Lara and Ruiz could share their ideas for a possible paint job. The duo promised to return to the bar with a formal proposal, and, over the course of a few nights, Lara and Ruiz connected with esparza to outline a design proposal, budget, and timeline in dialogue with Jalisco (Lara 2020, pers. comm.). Lara returned to the bar and proposed to the owners that esparza and Ruiz not complete a simple paint job but instead produce a mural. The project would be completed in two days with supplies paid for by the bar. “The owners said yes—I sold it to them”, Lara informed me via text message (Lara 2019, pers. comm.). Upon gaining the bar’s approval, Lara, esparza, and Ruiz rallied their friends and loved ones to get started on the mural. Everyone had a role: Lara served as a broker of sorts, liaising with bar management, ensuring supplies and scaffolding were acquired, and managing inquiries from the public, while esparza and Ruiz came together to implement their design.

The mural was nearly finished when I visited them around noon on 4 May 2019, their second day of painting. My boyfriend Mark and I had brought water and chips to the group and checked in to see how we could support them. The team had borrowed a scaffold from artist and friend Alfonso Gonzalez Jr., but it was somewhat unstable, requiring someone to keep hold of its base whenever the artists were using it.29 We traded shifts with other friends to support esparza’s weight as he completed the final touches on the mural. We all looked up and watched esparza as he painted the arm hair and chest hair on the portrait of Nacho Nava located on the far-left side of the mural. As esparza completed this final portrait of the mural, everyone present reflected on Nava—a friend, mentor, and nightlife leader who was gone too soon.

The completed mural, Nostra Fiesta, features nine figures rendered against a bright pink background, surrounded by beers, music notes, and decorations, who collectively form a joyful ballroom scene (Figure 7). Elements of the mural’s composition reference an etching by Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada (1851–1913) that commemorated the 1901 incident of “El baile de los cuarenta y uno” in Mexico City, where 41 men and cross-dressers were illegally raided, brutalized, and detained by the police for their alleged homosexuality. This early twentieth century scandal catapulted LGBT discourse into the media for the first time in Mexican history (Barrón Gavito 2010) and is now recognized as a seed for the country’s modern-day LGBT rights movement (Najar 2017). esparza and Ruiz borrow central elements of Posada’s composition, including a dancing duo of men wearing a suit and gown, while remixing it to feature a pair of transmasculine cowboys, lesbian veteranas, and local figures such as Nava and the drag impersonators of Juan Gabriel and Celia Cruz. The mural was unveiled on the evening of 5 May 2019, with a small group of artists and friends present to celebrate esparza, Ruiz, Lara, and their collective achievement. People gathered outside to talk about the collaboration, appreciate the mural’s composition, and consider their own relationship to Jalisco. As the night continued, visitors moved inside the long rectangular bar to take part in its regularly scheduled programming of Latinx drag performance.

Figure 7.

rafa esparza and Gabriela Ruiz, Nostra Fiesta, mural, The New Jalisco Bar, Los Angeles, 11 July 2019, photo by the author.

Five months later, on 13 October 2019, Lara and I would host an informal talk on the sidewalk in front of Jalisco with esparza and Ruiz to discuss the mural in dialogue with our exhibition Liberate the Bar! Queer Nightlife, Activism, and Spacemaking. The artists had created a gallery-specific art installation inspired by Nostra Fiesta and recalled the story behind the mural’s conception and the various elements of its composition. Lara and I facilitated the conversation and highlighted the importance of the mural and its place within the city. As curators, we discussed how Lara’s leadership and contributions to Nostra Fiesta modeled a type of culturally relevant and responsive curating that also operates as a form of activism (Reilly 2017). Here, Lara’s curatorial activism helped to spotlight ephemeral nightlife histories and figures (notably Nava) while simultaneously connecting them to a wider transnational and public discourse. After the talk, we would once again enter the bar after holding sidewalk conversations in front of the mural, only this time the Sunday night programming was tailored to the mural, its history, and its contributors and friends. The bar owners had scheduled a Juan Gabriel impersonator to perform, Gabriel being one of Nava’s favorite musicians and performers, and the impersonator presented a set of the musician’s most iconic songs. Later in the evening, the night’s host invited Lara, Ruiz, and esparza to the dancefloor to address the crowd and share additional remarks of gratitude to the bar owners for allowing them to create something so special for a nightlife venue of equal significance to the group.

Nostra Fiesta is a remarkable artistic effort that exemplifies the ethos of this collaborative artist network and its commitment to queer nightlife. The mural and its production tell the story of a group of friends who used their skills, practices, and relationships to come together and produce something of value not only to themselves but also to the bar owners, returning clients, and the art and nightlife community more broadly. esparza, Ruiz, and Lara used their public urban platform to foreground local and transnational histories while celebrating the individuals and venues that have breathed life into the city. Like many murals, Nostra Fiesta is imbued with a pedagogical spirit, as its composition calls attention to early LGBTQ history in Mexico, where many of the bar’s clients share cultural roots, while simultaneously honoring and recognizing local legend and friend Nacho Nava as a frequent visitor who had brought esparza, Ruiz, and Lara to the bar and as a leader in the city’s underground nightlife circuits.

The mural’s explicitly queer iconography also makes it significant. As Nostra Fiesta came to be, esparza and Lara reflected on the history of muralism in Los Angeles, recognizing the dearth of queer representation in this medium (Lara 2019, pers. comm.). While Los Angeles murals have long played an important role in serving as vehicles for public teaching, participation, and visibility for communities of color, it has not always been the case that LGBTQ figures and imagery have been included or centered in their compositions. For the Chicano art movement in particular, a combination of male bravado, homophobia, heteronormativity, and general cultural resistance to queerness played a role in censoring or preventing queer iconography from being represented within Chicanx murals.30

In his book chapter “The Iconoclasts of Queer Aztlán”, Chicanx studies scholar Robb Hernandez writes about key examples since the 1990s of public resistance and outright violence toward public art projects that have centered queer of color iconographic imagery (R. Hernandez 2019a). These include Alex Donis’ My Cathedral (1997), a site-specific installation that debuted in the street-facing windows of Galería de la Raza in San Francisco’s Mission district, a neighborhood historically home to the city’s Latinx populations. Here, the artist’s same-sex compositions of kisses between religious and cultural figures such as Mary Magdalene and La Virgen de Guadalupe, Jesus Christ and Lord Rama, and Che Guevara and Cesar Chavez were met with waves of confusion, protest, and vandalism. Nearly twenty years later at the same gallery, artist Manuel Paul (on behalf of the Maricón Collective) would create Por Vida (2015), a street mural depicting a transgender Chicano flanked by two same-sex couples in a warm embrace. This explicitly queer mural would be defaced three times over the course of its first summer in the city, revealing the ways in which queer visual artists’ desires to see themselves reflected within the public sphere have been challenged by members of their own community as well as by members of the public at large. While both examples took place in San Francisco, they nevertheless illustrate a shared struggle for queer Latinx artistic visibility that has also permeated throughout the Los Angeles public sphere.31 Like their San Francisco counterparts, the artists of Nostra Fiesta queered the mural tradition, producing what scholar and theorist Luis Aponte-Parés has called Latinx “queerscapes”, or new landscapes whose queer iconography contributes to a reterritorialization of public space (Aponte-Parés 2001, p. 368). Nostra Fiesta has effectively transformed the downtown landscape by proudly visualizing the longstanding queer, Latinx, and immigrant presence that Jalisco has come to serve and represent.

Today Nostra Fiesta has spent more than five years in the public sphere. It is a blessing to report that there have been no incidents with the mural in terms of vandalism or complaints. The mural’s height, coupled with esparza, Ruiz, and Lara’s long-standing relationships with Jalisco, built upon years of visits, have secured the mural’s spot as a vibrant welcome sign for the bar that is guarded and embraced by bar owners, bar regulars, the mural’s artists, and their friends.

5. YOU (2019-Ongoing)

Marge Simpson, a sexy luchador, and a woman dressed as a disco ball stand among others on an elevated platform surrounded by a lively crowd of people cheering for them (Figure 8). These are the costume contest finalists for Halloween night at YOU—a queer party established and directed by artist Sebastian Hernandez. As I stand at the end of the bar’s large and crowded dance floor with friends, we quickly discuss who we want to win the contest. “Marge! Luchador!! Disco ball!!!” Our voices come together as we scream to collectively choose a winner. Hernandez uses the DJ’s microphone to calm the crowd and moderate the voice levels serving as votes. It seems that we are aligned with the others in the crowd, as Marge, luchador, and disco ball make it to the top three. I yell at the top of my lungs for luchador to win, but to my dismay, Hernandez declares disco ball the winner. It is midnight, and the night is still young. With the costume contest over, we drink and dance to eclectic and genre-bending DJ sets by BAE BAE (Kumi James), PACHUCO (Andrew Jaramillo), and LATEX LUCIFER (Alfredo Llamas).

Figure 8.

Costume finalists take the stage at YOU, La Cita Bar, Los Angeles, 16 October 2019, photo by the author.

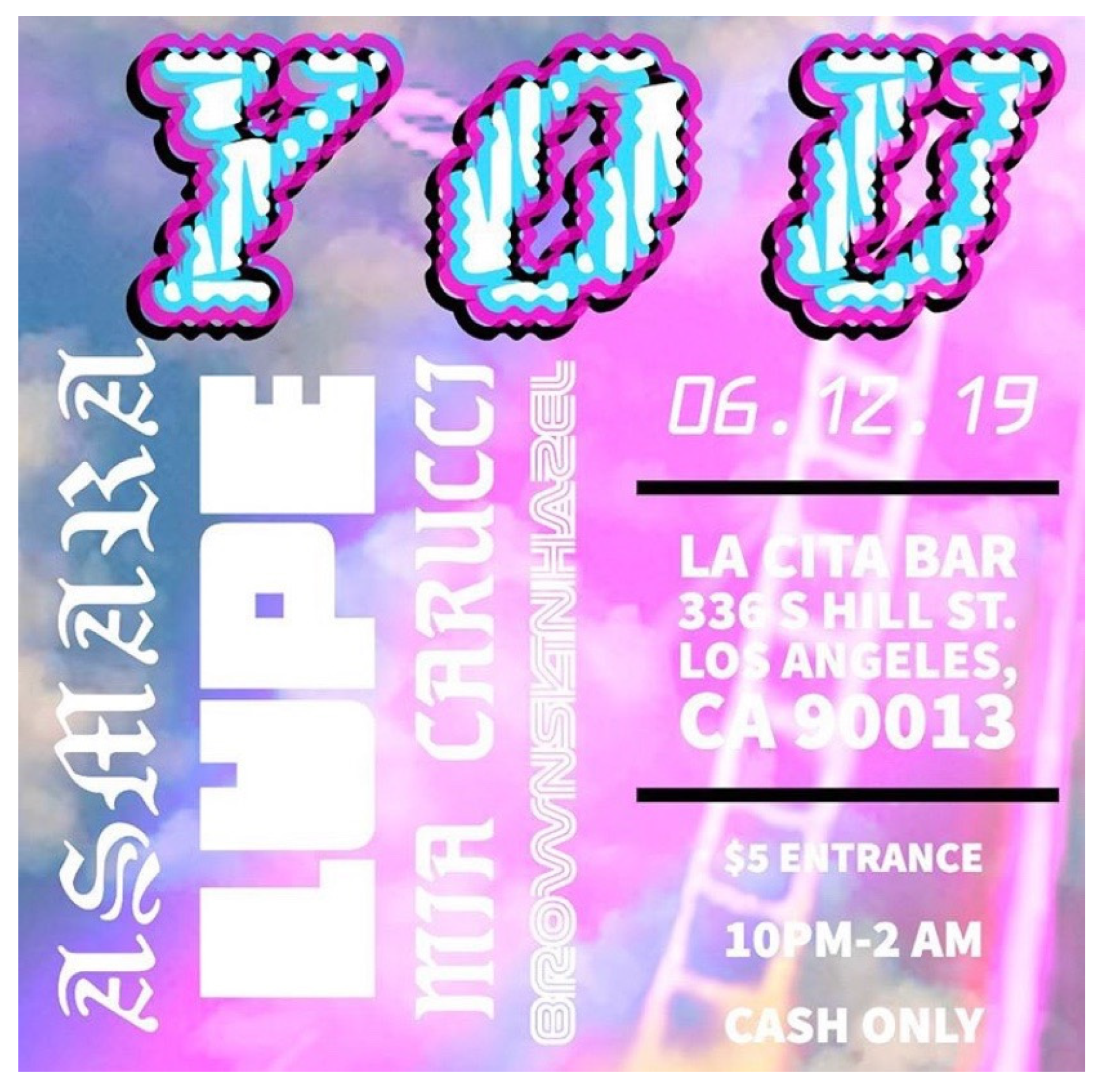

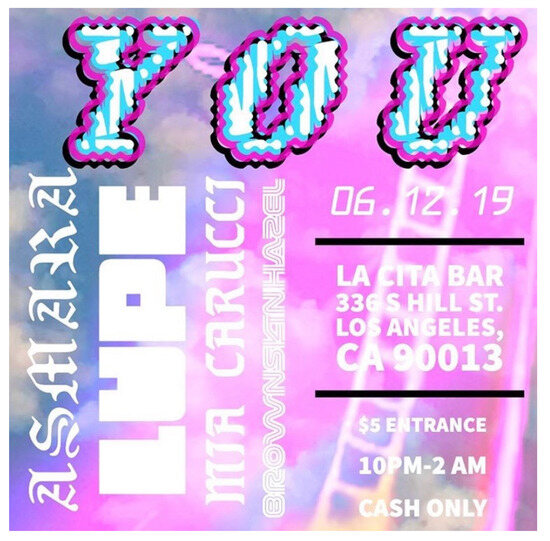

Since its launch at La Cita on 12 June 2019, Hernandez has organized impressive line-ups of DJs, including Asmara, Mia Carucci, Helikonia, and Morenxxx, as well as fashion designers, social media influencers, and artists from within Hernandez’s circle, who have served as the party’s hosts and/or co-organizers. Hernandez has also contributed as DJ on some nights, reviving their performance moniker born from Mustache Mondays, BROWNSKINHAZEL, for their DJ debut. Mustache has also provided Hernandez a key network of support, where members of the “Mustache Family”, those who participated and found community in the weekly party, offered early support of YOU and served as DJs, performers, hosts, event staff, and social media support.

Although YOU deviates from the previous case studies in that it is not a single artwork or performance, I highlight its importance within the context of this artist network and consider the organization, promotion, operations, and partying therein as an extension of Hernandez’s artistic practice. This point mirrors the scholarship of madison moore and Lucas Hilderbrand, who have positioned queer nightlife as a medium or artform itself, where organizers serve in a creative role tasked with “the production of scenes” (Moore 2016, p. 61) that express or give structure to various “social actions and worldviews” (Hilderbrand 2023, p. xv). Hernandez’s artistry is expressed through the organization of the party, not only through their DJ sets and performances but also through the creative design of digital flyers that market the party (Figure 9 and Figure 10) and the selection and pairing of various DJs, performers, hosts, and venues that ultimately shape the vibe and texture of any given night.32 This creative work is gratifying for Hernandez, who has been able to activate what performance scholar and theorist José Esteban Muñoz identified as the “transformative power” of nightlife for queers and people of color (Muñoz 2009, p. 108). For Muñoz, nightlife, and the art, performances, and sociality taking place therein, can operate as sites of becoming both for performers and for attendees, where they can imagine, temporally and physically, who and where they can and want to be in the present and future (Muñoz 2009, p. 100).

Figure 9.

YOU digital flyer, 12 June 2019, design by Sebastian Hernandez.

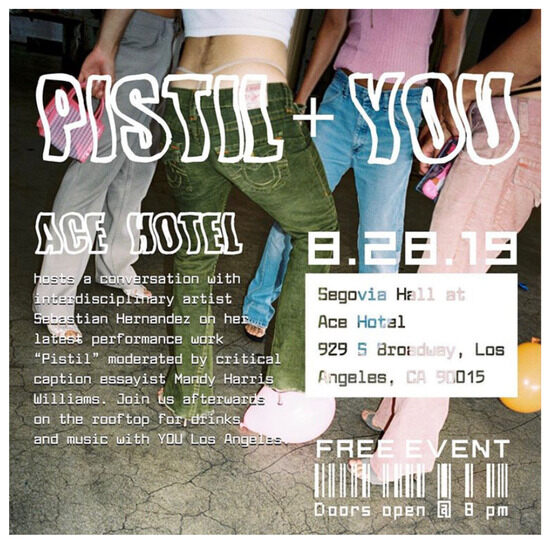

Figure 10.

YOU + Pistil digital flyer, Ace Hotel, 28 August 2019, design by Sebastian Hernandez.

Through YOU, Hernandez helps to facilitate the same generative nightlife context that has kept them alive and thriving in the city. And as mentioned in the introduction to this article, queer nightlife, and Mustache Mondays in particular, has served as a safe space and platform for Hernandez, a place where, through performance and sociality, Hernandez has been able to experiment creatively but also process and survive the violence and devaluation of their everyday life (S. Hernandez 2018).33 This is in line with thinking set forth by critic and theorist Joshua Chambers-Letson, who, echoing Muñoz, asserts that parties or social spaces in general can serve as sites of refuge (“to catch one’s breath when you can’t breathe”), as well as serving as catalysts for revolutionary planning and future-forward world making (Chambers-Letson 2018, p. xi; Muñoz 1999, p. 195). World making, as a process, does not suggest the creation of a geopolitical or bordered culture but rather the production of a moment or space of “creative, expressive, and transformative possibilities” (Buckland 2002, p. 4). As a queer nightlife organizer, Hernandez taps into this world-making apparatus to develop art and performances and build communality, visibility, and a sense of self, while spring-boarding into other underground and mainstream art, design, and performance settings and opportunities.34

Since starting at La Cita, YOU has morphed and found homes at other venues. On one occasion, Hernandez hosted a public talk at the now-defunct Ace Hotel in downtown LA, which was followed by a dance party celebration on the venue’s rooftop bar and pool. In December 2019, Hernandez moved the party away from La Cita and into El Dorado, a smaller upscale venue located just two blocks away, and on 11 February 2020, Hernandez partnered with Performance Space New York, Commonwealth & Council, and a roster of artists and performers (including esparza, Ron Athey, and Vander Von Odd) to host a VIP iteration of the party for the Frieze Los Angeles art fair.

The COVID-19 pandemic saw a decline in in-person art and socialization, if only temporarily, but YOU, as with queer nightlife in general, continues to provide new offshoots for creating art and community in Los Angeles (Valencia 2023, pp. 90–91). These adjustments reveal the malleability of the party format, emphasizing its capacity to accommodate the interests and needs of both Hernandez and their attendees. Above all else, YOU gestures to a queer futurity, one that is continually in progress, as the end of the night for each monthly iteration is not the end of it all but rather a recharging site and point of departure for new and continued beginnings.35

6. Conclusions

“The performance work I do was really born out of responding to being shunned or excluded from a community. And so, creating these spaces where we could view something and experience something together has been the vehicle that inspires me to want to continue to make work outside of museums”.(esparza in Christovale and Ellegood 2018, p. 104)

“[At Mustache], you [would] pay your ten or fifteen-dollar ticket to go hear music and dance all night. But then in the middle of it you have a great fucking performance artist who will just perform in the middle of the night. You don’t have to go to a museum to experience this”.(Ruiz in Helou Hernandez 2019)

“Queer club culture and nightlife has been a formative part of my art-making for over a decade and has impacted what it looks like today … I am interested in seeing how my party will impact the next generation of art-making in Los Angeles”.(S. Hernandez 2019, pers. comm.)

Sometimes queer nightlife is about dancing. Other times it is about drinking and socializing, or even fighting. However, in the right context with the right people, queer nightlife is much more. It is the place where one enacts the practice towards liberation (Román 2011, p. 292). As this article lays out, for esparza, Hernandez, Ruiz, and their friends and collaborators, queer nightlife is the site where survival and play intersect, where the practice toward liberation is enacted, and where opportunities to create art, community, and new potentialities are made.

Centering queer nightlife in the study of contemporary art and cultural production does indeed rupture existing art historical and curatorial approaches to queer Latinx artistic practices. It charts a new way of thinking about artists beyond their artistic output, a way of thinking that makes room for them to exist and be recognized as individuals, friends, mentors, family members, and members of a community. Distinctions between studio time and clubbing are not generative for this group of artists, as many times the clubs are their studios, their places to experiment, create, and present work, as well as their places to relax, experience joy, or even lose control. Moreover, whether performing at a bar, painting a mural on the bar’s exterior, working the door, or partying inside, it is esparza, Hernandez, and Ruiz’s engagement with queer nightlife that reveals their individual and shared history, culture, politics, art practices, and ways of being. Their praxes of working in connection to others emphasizes a direction for art making and being that traverses inside and outside nightlife, the art world, and everyday life. It is cognizant of the past and gestures towards the future but is firmly rooted in making the present a viable and nurturing place for them to live and thrive.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge rafa esparza, Sebastian Hernandez, and Gabriela Ruiz for their inspiring artistic practices, Paulina Lara for her friendship and collaboration, Mark Casas, for his love and support, Amelia Jones, for her mentorship, and Guest Editors Ray Hernández-Durán and Cristina Cruz González, for their invitation to contribute to this Special Issue.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest or private gain from this article.

Notes

| 1 | For more about esparza’s reframing of art and exhibition opportunities for other artists, collaborators, or friends, and the politics of this artistic strategy, see (Grossman 2017). |

| 2 | de la Calle culminated with a guerrilla parade-like procession through Los Callejones/Santee Alley in downtown Los Angeles that was promoted only via word of mouth. If we consider it outside its art institution origination, the performance could have easily been its own case study in this article: one that emphasizes the network’s connection to this historic shopping site for the purchase of various elements of their nightlife looks; the important ways in which esparza and other members of this network created the performance for themselves and specific members of their queer and/or cultural communities, in this case the workers and shoppers of this working-class, predominantly Latinx, stronghold in the city; and the immense interest in the performance by the art world and people on social media, where those not involved wondered how and/or why they were not included. See also (Miranda 2018). |

| 3 | But as the editors of Queer Nightlife (2021) poignantly express, “queer nightlife does not need the perceived legitimacy of scholarship to be legible or to thrive”. See (Adeyemi et al. 2021, p. 10). |

| 4 | These include (Ghaziani 2024; Hilderbrand 2023; García-Mispireta 2023; Mattson 2023; Adeyemi 2022; Allen 2022; Adeyemi et al. 2021; Lin 2021; Khubchandani 2020; Chambers-Letson 2018); and (Moore 2018). This increase in scholarship notably coincides with the 50th anniversary of Stonewall in 2019, commonly recognized as the birth of the U.S. gay liberation movement. It’s safe to say queer nightlife studies is here to stay. |

| 5 | The arts, broadly defined, have not always been at the forefront of queer nightlife analyses, with some exceptions. madison moore has notably written about the experience of queer nightlife through aesthetic terms (Moore 2016, pp. 50–51), and has referenced art or artists in related books and articles (Moore 2016, 2018). Additional scholars who come to mind include (J.M. Rodríguez 2021) who detailed performance artist Xandra Ibarra’s bar hopping tour; and (Hilderbrand 2023) who wrote about the New Jalisco Bar mural also featured in this article. |

| 6 | My curatorial practice and scholarship often aims to consider alternative ways to study art and visual culture. As I was building my expertise in live art and performance studies, the work of scholars Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield helped to shape my understanding and embrace of engaging with fields outside of art history to provide “new models for thinking about how visual and embodied cultural expressions come to mean”. See (Jones and Heathfield 2012, p. 12). |

| 7 | In many regards, this practice has been modeled after Italian painter and architect Giorgio Vasari, who relied heavily on individual authorship and biography to tell the story of Renaissance art in The Lives of the Artists. This now-classic text set the ideological and structural foundation for art historical scholarship that has continued today. See (Vasari [1550] 1991). |

| 8 | This is true for esparza’s exhibitions at the Vincent Price Art Museum, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (ICA LA), and the Hammer and Whitney biennials, among others. For the biennials, esparza’s collaborations are especially significant given the large-scale format. See Martha Rosler’s contributions to (Griffin 2003). |

| 9 | In addition to Liberate the Bar! (2019) at ONE Archives, there have been several exhibitions by alternative art spaces, galleries, and museums in my recent memory that have referenced both queer nightlife and contemporary art, including Estilazo (2022) at The Latinx Project, New York University; It’s Much Louder Than Before (2021) at Anat Ebgi; Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon (2019-Ongoing) at several organizations; and Party Out of Bounds: Nightlife As Activism Since 1980 (2015) at Visual AIDS and La MaMa Galleria. |

| 10 | This approach exercises a node of performativity in interpretation, as described by scholars and theorists Amelia Jones and Andrew Stephenson, where an element of performance is embedded in the act of ascribing meaning and value for art and performance, ultimately contributing to a more dynamic and contingent interpretation. See (Jones and Stephenson 1999) and (Jones 2012). |

| 11 | This has certainly been my experience as someone raised in a Mexican and Chicano enclave in Orange County, CA, but who works, socializes, and builds community within Los Angeles’s eastside and downtown areas. To learn more about queer sociality and the urban/suburban binary for queers of color in Southern California, see (Tongson 2011). For a transnational account, with chapters on California, see (Ingram et al. 1997). |

| 12 | While many public places have served as sites for sociality and leisure, including restaurants, cafes, parks, public events, and the streets themselves, this article hones in on queer nightlife as the site where sociality and leisure meet activism, community-building, and art-making to carve new space in the city. For a fantastic placemaking account of a single restaurant (which later became a nightclub due to gentrification and change of ownership), see (Molina 2015). On the boulevard, see (Fragoza 2017). |

| 13 | I am using “Chicano” in this context to point to a generation of young people in the 1960s and 1970s who self-identified with the term and built a collective civil rights and arts movement based on the identification. To learn more about this approach and its parameters, see (García 2015). |

| 14 | This quest for social and sexual freedom highlights the ways young queers of color since the 1960s, including Latinx folks, have challenged demarcated urban space. For more on this process, see (R.T. Rodríguez 2015). For Chicano space making in LA, see (Macias 2008). For a personal account from a Chicano perspective, see (Rojas 2016). |

| 15 | Queer communities that performance artist Ron Athey circulated in the 1980s and 1990s, for example, which included friends such as Vaginal Davis and Jennifer Doyle (whose remarks opens this article), were mostly linked to punk movements in Silver Lake/Echo Park and on the edges of downtown. (Jones 2020, pers. comm.). |

| 16 | I am indebted to Paulina Lara who, through her own life and through the course of conducting research for our exhibition Liberate the Bar! Queer Nightlife, Activism, and Spacemaking, shared with me so many different nightlife stories about Nava, and introduced me to their friends, collaborators, and the late-night places where they partied. |

| 17 | In a retrospective article for Red Bull Music Academy, Marke B. writes: “Mustache launched during a moment of creative ferment in American queer nightlife when a growing population of clubgoers was reacting against the homogenized pop-house sounds and cookie-cutter corporate feel of the clubs and culture at large… [Mustache had a] mission to diversify gay nightlife”. See (Bieschke 2017). |

| 18 | This is the core argument of my unpublished master’s thesis, which serves as the basis of this article. See (Valencia 2020). It was later explored through a KCET Artbound documentary and accompanying article. See (KCET Artbound 2021) and (Hidalgo 2021). |

| 19 | My intention here is to acknowledge Nava and Mustache as critical influences in this study of this queer nightlife network, its relationships, and creative outputs, but I write with sensitivity and care, and also love, especially for Paulina Lara, my friend who I have known for many years and whose side I have been by as she has experienced and processed Nava’s loss. |

| 20 | The event title, Escandalos Angeles, is a portmanteau of the Spanish words Escandalosa (scandalous) and Los Ángeles (LA) and also references a direct connection to Legorreta who used that term to describe himself and his work. See footnote annotations #34 and #52 in (R. Hernandez 2019a, pp. 271–72). |

| 21 | My use of Chicano here specifically evokes gender and same-sex exclusion and discrimination present within East Los Angeles during this time. On this point see (Flores Sternad 2006, p. 477). For a deeper historical account Robert “Cyclona” Legorreta’s life, activism, artistic practice, and archives, see (R. Hernandez 2009). |

| 22 | San Cha is also a friend and collaborator within this network, notably beginning her career in queer nightlife drag and performance scenes in Los Angeles and the Bay Area, before settling in Los Angeles to work exclusively as a singer-songwriter and performer. See (Mendez 2018). |

| 23 | It must also be stated that although Legorreta is still very much alive, he was not sought out or invited to participate in this performance program, and in some respects, the event gave the impression that he was actually deceased. Nao Bustamante, who had attended the event, had questioned, in a hysteric frenzy with fellow performance artist Marcus Kuiland-Nazario a few days prior to the event, “What if Cyclona just shows up and performs and ruins the party!? That would be so amazing!” To Bustamante’s disappointment, Legorreta did not intervene, nor did he show up at all. (Bustamante 2020, pers. comm.) I hope to pursue a future investigation of what this performance means in the absence of Legorreta. |

| 24 | esparza also develops work with this strategy in mind. “I’m always thinking about history”, esparza once stated. “As I walk through the city, I’m always imagining the many changes the landscape has undergone and attempting to imagine what the landscape looked like before all of these different migrations happened”. See Esparza’s comments in (Christovale and Ellegood 2018, p. 96). |

| 25 | Legorreta moved through different scenes with the help of sophisticated modes of self-fashioning. At times he was enmeshed in proto-punk and glitter queer scenes, and other times he infiltrated various gay and straight bars to seduce and tease cholos. This thread of seduction also links Hernandez and Ruiz’s performance with Legorreta. On Legorreta and “proto-punk” see (Flores Sternad and Lacy 2012, p. 96); On Legorreta and “glitter queer” see (Flores Sternad 2006, p. 485); On “teasing cholos” see (Flores Sternad 2006, p. 481). |

| 26 | Coincidently, Legorreta employed this very performance strategy, only in his case it was decades prior and for a dear friend: Edmundo “Mundo” Meza at the first-anniversary celebration of VIVA! Lesbian and Gay Latino Artists of Los Angeles, an artist coalition and nonprofit committed to increasing queer Latinx representation in art, performance, and activist circuits in Los Angeles. While there are differences between these artists and their evocations—Meza’s life and artistic contribution at the time risked near erasure from the historical record, compared to Legorreta, whose archives are preserved by and available for viewing at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at USC Libraries—the performance of remembrance enacted by Legorreta, Hernandez, and Ruiz across time and space further elucidates how knowledge sharing and the honoring of artistic and ancestral lineages is a key strategy for queer of color culture and creative expression. On Legorreta’s performance, see (R. Hernandez 2019b). |

| 27 | On queering “straight” time, see (Muñoz 2007, pp. 457–58). |

| 28 | Jalisco’s clientele is notably different from those who have historically frequented Club Chico (the bar mentioned in the first case study of this article). In my experience, first-generation Latinx frequenters, many Spanish-speaking, form the core of Jalisco’s base, while Latinx Angelenos who are more assimilated, including previous cholo clients of the 2000s, have found their home at Chico. In recent years, Chico has broadened its appeal to a more general Latinx audience, and this has only extended since hosting Club sCUM on the last Friday of each month. It is also notable that esparza, Hernandez, and Ruiz, and members of their queer nightlife network, frequent both Jalisco and Chico, a detail that I attribute to their heterogeneous cultural identifications and investments in their city’s queer nightlife landscape. On these particular Latinx venues and their varied functions and clientele, see also (Hilderbrand 2023). |

| 29 | Gonzalez is a Los Angeles contemporary artist and muralist whose father is a commercial sign painter. Here, esparza, Ruiz, and Lara pulled from their networks to locate the resources they needed to complete their project. On Gonzalez’s practice, see (Khatchadouria 2019). |

| 30 | Chicana feminist Cherie Moraga writes about this homophobia and cultural resistance, asserting that true liberation in El Movimiento is one that includes the embrace of all its people, including its jotería (queers). See (Moraga 2004, p. 225). |

| 31 | Interestingly enough, Netflix’s recent comedy-drama series Gentefied (2020), created by Marvin Lemus and Linda Yvette Chávez, also details a fictional Boyle Heights mural that is protested against for its queer iconography. Learn more in (Cuby 2020). |

| 32 | In a future text, I am interested in writing about the visuality of YOU vis-à-vis the digital flyers from each iteration of the party. These are designed by Hernandez and incorporate a range of cultural, vernacular, and art historical references, further emphasizing links among nightlife, visual arts, performance, and other modes of cultural production. |

| 33 | In a video feature, Hernandez says: “I live in an oppressive society in which I have had to fight for my existence. I know that if I am dancing, I am alive, and for me movement is happiness”. See (S. Hernandez 2018). |

| 34 | Since 2016, Hernandez has exhibited their work and performed at venues across Los Angeles, including Angels Gate Cultural Center; Club sCUM; Commonwealth and Council; Human Resources Los Angeles; Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Mustache Mondays; NAVEL; ONE Gallery, West Hollywood; and downtown’s Roy and Edna Disney Cal Arts Theatre (REDCAT), among many others. |

| 35 | This is one of the central points in (Chambers-Letson 2018). See also (Muñoz 2007, p. 454). |

References

- Adeyemi, Kemi. 2022. Feels Right: Black Queer Women and the Politics of Partying in Chicago. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi, Kemi, Kareem Khubchandani, and Ramón H. Rivera-Servera. 2021. Queer Nightlife. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Jafari S. 2022. There’s a Disco Ball between Us: A Theory of Black Gay Life. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aponte-Parés, Luis. 2001. Outside/In: Crossing Queer and Latino Boundaries. In Mambo Montage: The Latinization of New York. Edited by Agustín Laó-Montes and Arlene Dávila. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 363–85. [Google Scholar]

- B., Marke. 2017. Celebrating Ten Years of Mustache Mondays, LA’s Iconoclastic Party. Redbull Music Academy Daily. October 20. Available online: https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2017/10/mustache-mondays (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Barrón Gavito, Miguel Ángel. 2010. El baile de los 41: La representación de lo afeminado en la prensa porfiriana. Historia Y Grafía 34: 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Buckland, Fiona. 2002. Impossible Dance: Club Culture and Queer World-Making. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, Nao. 2020. University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Personal communication.

- Chambers-Letson, Joshua. 2018. After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Meiling. 2002. In Other Los Angeleses: Multicentric Performance Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christovale, Erin, and Anne Ellegood. 2018. Bridging and Breaking: Roundtable with Erin Christovale. Jennifer Doyle, Anne Ellegood, rafa esparza, Naima J. Keith, and Lauren Mackler. In Made in L.A. 2018. Edited by Erin Christovale and Anne Ellegood. Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, pp. 92–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cuby, Michael. 2020. Seen: Gentefied Tackles Gentrification with Humor and Authenticity. Them. February 21. Available online: https://www.them.us/story/gentefied-gentrification-netflix (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Dinco, Dino. 2017. Loving and Partying at Chico: ‘The Best Latino Gay Bar’ in Montebello. KCET Artbound. February 15. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/history-behind-chico-latino-gay-bar-montebello-los-angeles (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Donohue, Caitlin. 2019. Remembering Nacho Nava, a Force in Los Angeles’ Queer Nightlife Community. Remezcla. January 24. Available online: https://remezcla.com/music/nacho-nava-memorial-fund-scholarship (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Flores Sternad, Jennifer. 2006. Cyclona and Early Chicano Performance Art: An Interview with Robert Legorreta. GLQ 12: 475–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Sternad, Jennifer, and Suzanne Lacy. 2012. Voices, Variations, and Deviations: From the LACE Archive of Southern California Performance Art. In Live Art in LA: Performances in Southern California, 1970–1983. Edited by Peggy Phelan. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoza, Carribean. 2017. Cruising Down SoCal’s Boulevards: Streets as Spaces for Celebration and Cultural Resistance. KCET Artbound. February 24. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/cruising-on-socals-boulevards-the-streets-as-spaces-for-celebration-and-cultural (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- García, Mario T. 2015. The Chicano Generation: Testimonios of the Movement. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mispireta, Luis Manuel. 2023. Together Somehow: Music Affect and Intimacy on the Dancefloor. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziani, Amin. 2024. Long Live Queer Nightlife: How the Closing of Gay Bars Sparked a Revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Tim. 2003. Global Tendencies: Globalism and the Large-Scale Exhibition. Roundtable Discussion with James Meyer, Francesco Bonami, Catherine David, Okwui Enwezor, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Martha Rosler, and Yinka Shonibare. ARTFORUM 42: 152–63. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Hannah E. 2017. Performative Futurity: Transmuting the Canon through the Work of Rafa Esparza. Master’s thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Helou Hernandez, Samanta. 2019. Gabriela Ruiz Is Young, Subversive and Forging Her Own Way in the Art World. KCET Artbound. January 29. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/gabriela-ruiz-is-young-subversive-and-forging-her-own-way-in-the-art-world (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Hernandez, Robb. 2009. The Fire of Life: The Robert Legorreta-Cyclona Collection. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Robb. 2019a. Archiving an Epidemic: Art, AIDS, and the Queer Chicanx Avant-Garde. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Robb. 2019b. Mundos Alternos—Alien Skins. YouTube. May 9. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=7s&v=qbG7v75RZJM (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Hernandez, Sebastian. 2018. Be You: Finding Liberation in Art with Sebastian Hernandez. BESE. December 7. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYYFkZsrxXo (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Hernandez, Sebastian. 2019. Independent Artist. Personal communication.

- Hidalgo, Melissa. 2021. How Mustache Mondays Built an Inclusive Queer Nightlife Scene and Influenced the Arts in L.A. KCET Artbound. November 17. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/mustache-mondays-inclusive-nightlife-and-contemporary-art (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Hilderbrand, Lucas. 2023. The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America 1960 and After. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter. 1997. Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance. Seattle: Bay Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amelia. 2012. Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identity and the Visual Arts. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amelia. 2020. University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Personal communication.

- Jones, Amelia, and Adrian Heathfield. 2012. Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History. Bristol: Intellect. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amelia, and Andrew Stephenson. 1999. Performing the Body/Performing the Text. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- KCET Artbound. 2021. Mustache Mondays. November 17. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/episodes/mustache-mondays (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Khatchadouria, Alex. 2019. Finding Art in the Everyday: Alfonso Gonzalez Jr.’s Paintings Depict a Localized Perception of His Surroundings. Amadeus. July 30. Available online: http://amadeusmag.com/blog/finding-art-everyday-alfonso-gonzalez-jr (accessed on 29 March 2020).

- Khubchandani, Kareem. 2020. Ishtyle: Accenting Gay Indian Nightlife. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Korte, Gregory, and Alan Gomez. 2018. Trump Ramps up Rhetoric on Undocumented Immigrants: ‘These Aren’t People. These Are Animals.’ . USA Today. May 16. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/05/16/trump-immigrants-animals-mexico-democrats-sanctuary-cities/617252002 (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Lara, Paulina. 2019. Independent Curator. Personal communication.

- Lara, Paulina. 2020. Independent Curator. Personal communication.

- Lin, Jeremy Atherton. 2021. Gay Bar: Why We Went Out. New York: Back Bay Books. [Google Scholar]

- Macias, Anthony F. 2008. Mexican American Mojo: Popular Music, Dance, and Urban Culture in Los Angeles, 1935–1968. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, Greggor. 2023. Who Needs Gay Bars? Bar-Hopping through America’s Endangered LGBTQ Places. Stanford: Redwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, Stephanie. 2018. San Cha, The Fierce Latinx Musician Anchoring Herself in Rancheras and Identity. She Shred Media. November 7. Available online: https://sheshreds.com/san-cha (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Miranda, Carolina. 2018. Why Artist Rafa Esparza Led a Surreal Art Parade through the Heart of L.A.’s Fashion District. Los Angeles Times. June 25. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-rafa-esparza-ica-la-20180625-story.html (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Molina, Natalia. 2015. The Importance of Place and Place-Makers in the Life of a Los Angeles Community: What Gentrification Erases from Echo Park. Southern California Quarterly 97: 69–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Madison. 2016. Nightlife as Form. Theater 46: 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Madison. 2018. Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moraga, Cherie. 2004. Queer Aztlán: The Re-formation of Chicano Tribe. In Queer Cultures. Edited by Deborah Carlin and Jennifer DiGrazia. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, pp. 224–38. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 1999. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2007. Queerness as Horizon: Utopian Hermeneutics in the Face of Gay Pragmatism. In A Companion to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Studies. Edited by George E. Haggerty and Molly McGarry. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 452–63. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Najar, Alberto. 2017. ¿Por qué en México el número 41 se asocia con la homosexualidad y sólo ahora se conocen detalles secretos de su origen? BBC Mundo. January 11. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-38563731 (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Nordeen, Bradford. 2018. Dirty Looks: On Location (Event Series Booklet). Los Angeles: Dirty Looks Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, Maura. 2017. What Is Curatorial Activism? ARTnews. November 7. Available online: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/what-is-curatorial-activism-9271/ (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Rodríguez, Juana María. 2021. Public Notice from the Fucked Peepo: Xandra Ibarra’s ‘The Hookup/Displacement/Barhopping Drama Tour.’. In Queer Nightlife. Edited by Kemi Adeyemi, Kareem Khubchandani and Ramón Rivera-Servera. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 211–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Richard T. 2006. Queering the Homeboy Aesthetic. Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 31: 127–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Richard T. 2015. The Architectures of Latino Sexuality. Social Text 33: 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, James. 2016. From the Eastside to Hollywood: Chicano Queer Trailblazers in 1970s L.A. KCET LOST LA. September 2. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/from-the-eastside-to-hollywood-chicano-queer-trailblazers-in-1970s-la (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- Román, David. 2011. Dance Liberation. In Gay Latino Studies: A Critical Reader. Edited by Michael Hames-Garcia and Ernesto Javier Martínez. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 286–310. [Google Scholar]

- Roque Ramírez, Horacio N. 2003. “That’s My Place!”: Negotiating Racial, Sexual, and Gender Politics in San Francisco’s Gay Latino Alliance, 1975–1983. Journal of the History of Sexuality 12: 224–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque Ramírez, Horacio N. 2007. “Mira, yo soy boricua y estoy aquí”: Rafa Negrón’s Pan Dulce and the queer sonic latinaje of San Francisco. Centro Journal XIX: 274–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, Gabriela. 2018. Independent Artist. Personal communication.

- The New Jalisco Bar. 2018. Travel Gay. October 19. Available online: https://www.travelgay.com/venue/the-new-jalisco-bar (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Tongson, Karen. 2011. Relocations: Queer Suburban Imaginaries. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, Joseph Daniel. 2020. Queer Nightlife Networks and the Art of Rafa Esparza, Sebastian Hernandez, and Gabriela Ruiz. Master’s thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, Joseph Daniel. 2023. “Striving Toward Multiple Ideas of Community”: Chicanx Art, Artists, and Affectivity in Los Angeles. In Xican-a.o.x. Body. Edited by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, Marissa Del Toro and Gilbert Vicario. Munich: Hirmer Publishers, pp. 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1991. Preface to Part Three. In The Lives of the Artists. Translated by Julia Conaway Bondanella, and Peter Bondanella. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published in 1550. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).