The Protection of Monuments and Immoveable Works of Art from War Damage: A Comparison of Italy in World War II and Ukraine during the Russian Invasion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. How Can Italy in 1940 Be Compared to Ukraine? Heritage Management and the Experience of War

3. Registering the Importance of Protecting Monuments from Destruction: Cultural Memory and International Law

4. Terminology and Scope: Monuments and Immoveable Works of Art

5. Proactive Measures: Planning for Protection of Cultural Property during War

6. The First Stages of Protection: Facing Obstacles and Establishing Priorities

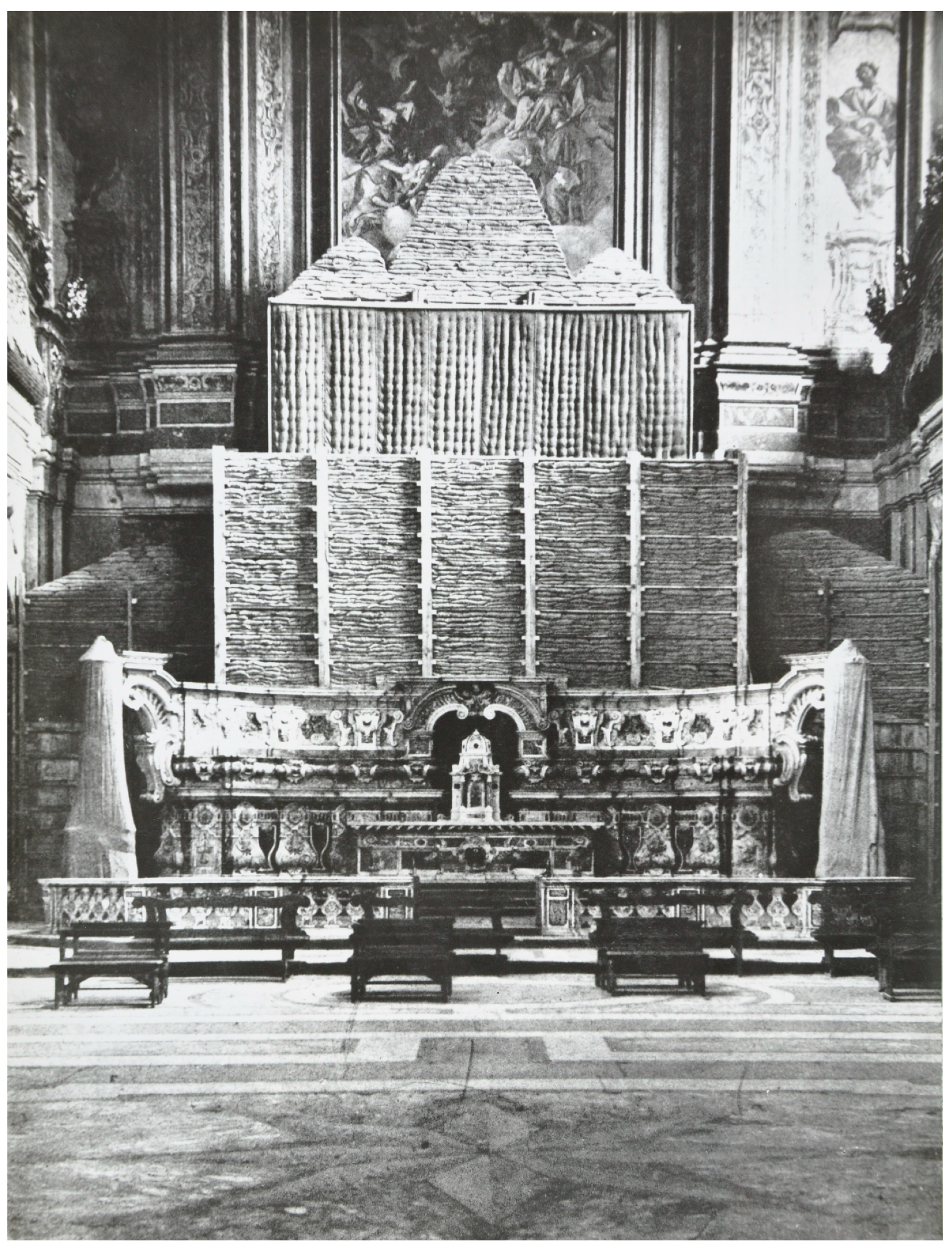

7. Approaches to the On-Site Protection of Monuments and Immoveable Works of Art

8. The On-Site Protection of Churches and Their Immoveable Decoration

9. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armanagué, Bernat. 2022. At Ukraine’s largest art museum, a race to protect heritage. AP News. March 6. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-travel-europe-art-museums-museums768ce266673b85965edc8367c2257370?fbclid=IwAR1gZ9qHLI-1bbtStu6r5WE4tsQHZFj19kQhKILsrDkADqwOtZUSVDY430 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Artioli, Alberto. 2022. L’architettura e I provvedimenti di salvaguardia. In Il Cenacolo. Approfondimenti: Il Restauro. Edited by Alberto Artioli. Milan: Electa, pp. 9–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, Pèleo. 1930–1937. Correspondence with Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS (Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome), MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 69. [Google Scholar]

- Balbek Bureau. 2022. Re: Ukrainen Monuments. Available online: https://www.balbek.com/reukraine-monuments (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Balzani, Roberto. 2003. Per le Antichià e le Belle Arti: La Legge n. 364 del 20 Giugno 1909 e l’Italia Giolittiana. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, Robert. 2006. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovska, Valentyna. 2022. Director, Museum of Book and Printing of Ukraine, Kyiv. Interview presented by IFAR, New York: “An IFAR Evening. Ukrainian Cultural Heritage. What’s Damaged, Destroyed, Documented, and Being Done”. April 27, Zoom Webinar. Available online: https://www.ifar.org/past_event.php?docid=1649960899 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Bosman, Suzanne. 2008. The National Gallery in Wartime. London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bottai, Giuseppe. 1938. La tutela delle opere d’arte in tempo di guerra. Bollettino D’arte 31: 429–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bunch, Lonnie. 2022. Safeguarding the Cultural and Historical Heritage of Ukraine. March 3. Available online: https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/releases/safeguarding-cultural-and-historical-heritage-ukraine/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Calzecchi Onesti, Carlo. 1940. Lavori di difesa antiaerea del Battistero e Duomo. 15 July. In Archivio Storico, Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici, Florence, Cartella 2, A 166. [Google Scholar]

- Campfens, Evelien, Andrzej Jakubowski, Kristin Hausler, and Elke Selter. 2023. Protecting Cultural Heritage from Armed Conflicts in Ukraine and beyond, European Parliament, Policy Study (European Union, March). p. 12. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2023/733120/IPOL_STU(2023)733120_EN.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Church of the Ascension. 2022. Church of the Ascension (Lukashivka) after Fighting (2022-04-24). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Church_of_the_Ascension_(Lukashivka)_after_fighting_(2022-04-24)_01.jpg (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Circolare. 1933. January 24. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1940–1945), busta 77, fasc. 1258. [Google Scholar]

- Circolare urgente riservatissimo. 1940. June 5. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 92. [Google Scholar]

- Circolare 7. 1940. January 13. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 93, fasc. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Circolare 24. 1930. December 18. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 69. This file also includes later correspondence about the same subjects from 1935–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Circolare 79. 1938. June 7. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 72. [Google Scholar]

- Circolare 157. 1942. December 29. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 93, fasc. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Circolare 158. 1938. October 13. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 72. [Google Scholar]

- Circolare 210. 1939. October 29. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 86, fasc. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Circolare 4965. 1936. July 11. Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1940–1945), busta 77, fasc. 1258. [Google Scholar]

- Coccoli, Carlotta. 2007. Repertorio dei fondi dell’Archivio Centrale dello Stato relativi alla tutela dei monumenti italiani dalle offese belliche nella seconda guerra mondiale. Storia Urbana: Rivista di Studi Sulle Trasformazioni Della città e del Territorio in età Moderna 114–115: 303–29. [Google Scholar]

- Coccoli, Carlotta. 2010. I ‘fortilizi inespugnabili della civiltà italiana’: La protezione antiaerea del patrimonio monumentale italiano durante la seconda guerra mondiale. In Pensare la Prevenzione: Manufatti, Usi, Ambienti. Conference Paper. Milan: Polimi. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/271510/_I_fortilizi_inespugnabili_della_civilt%C3%A0_italiana_la_protezione_antiaerea_del_patrimonio_monumentale_italiano_durante_la_seconda_guerra_mondiale_ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Coccoli, Carlotta. 2017. Monumenti Violati: Danni Bellici e Riparazioni in Italia nel 1943–1945: Il Ruolo Degli Alleati. Florence: Nardini. [Google Scholar]

- Congresso internazionale a Bruges per il Patto Roerich per la protezione opere d’arte in caso di guerra. 1931–1932, InACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 108.

- Constitution of Ukraine. 1996. Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (Constitution of Ukraine). June 28. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/en (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Culture in Crisis. 2023. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Projects: “Sending Fire Extinguishers to Safeguard Historic Wooden Churches”, and “Installing a Temporary Cover at the Holy Trinity Church in Zhovkva”. Available online: https://cultureincrisis.org/projects/sending-fire-extinguishers-to-safeguard-historic-wooden-churches (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Daniels, Brian. 2022. Protecting Cultural Heritage during Conflict. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. May 9. Available online: https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2022/05/09/protecting-cultural-heritage-during-conflict/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Dell’Aja, Gaudenzio. 1980. Il Restauro della Basilica di Santa Chiara in Napoli. Naples: Giannini & Figli, repr. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Della Volpe. 1986. Difesa del Territorio e Protezione Antiaerea (1915–1943). Rome: Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito Ufficio Storico. [Google Scholar]

- Elenco dei Monumenti Nazionali. 2024. Available online: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monumenti_nazionali_(Italia) (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Erll, Astrid. 2011. Memory in Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Espon/Heriwell. 2022. Cultural Heritage as a Source of Societal Well-Being in European Regions, Final Report (European Union, June). Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/HERIWELL_Final%20Report.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- FCDO. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), Office for Conflict, Stabilisation and Mediation (OCSM), Centre for Informational Resilience (CIR), His Majesty’s Government, United Kingdom. “FCDO Request (Culture_Religious) Damage, 15 January 2023”, Excel Chart (Personal communication).

- Fogolari, Gino. 1918. II. Protezione degli oggetti d’arte: Relazione sull’opera della Sovrintendenza alle Gallerie e agli Oggetti d’Arte del Veneto e per difendere gli oggetti d’arte dai pericoli della guerra. Bollettino D’arte 12: 185–229. [Google Scholar]

- Forlati, Ferdinando. 1947. Attorno agli affreschi della Cappella degli Scrovegni. Arte Veneta 1: 303. [Google Scholar]

- Forlati, Ferdinando. 1945. Relazione mensile sull’attività della Soprintendenza ai Monumenti, Venezia, July 20, 21st Monthly Report, AMG-169, pp. 45–46. In NARA (National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD), RG 331. [Google Scholar]

- Fortino, Francesco. 2011. Il Gabinetto e l’Archivio Fotografico della Soprintendenza ai Monumenti. In Francesco Fortino and Claudio Paolini, Firenze 1940–1943: La Protezione del Patrimonio Artistico Dalle Offese della Guerra Aerea. Florence: Edizioni Polistampa, pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Frayer, Lauren, and Claire Harbage. 2022. Ukraine Scrambles to Protect Artifact and Monuments from Russian Attack. National Public Radio. March 15. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2022/03/15/1086444607/ukraine-cultural-heritage-russia-war (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Gioannini, Marco, and Giulio Massobrio. 2007. Bombardate l’Italia. Milan: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Hadžimuhamedović, Amra, and Moumir Bouchenaki. 2018. Reconstruction of the Old Bridge in Mostar. World Heritage 86: 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hague Convention. 1899. Convention (II) with Respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land and Its Annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague. July 29. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-conv-ii-1899 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Hague Convention. 1907. Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague. October 18 Articles 23, 27, 28, 46, 47 and 56. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-conv-iv-1907 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Hague Convention. 1954. Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. The Hague. May 14. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-conv-1954 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Hague Rules for Air Warfare. 1923. International Committee of the Red Cross, International Humanitarian Law Databases. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/historical-treaties-and-documents (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On Collective Memory. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartt, Frederick. 1949. Florentine Art Under Fire. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Headquarters Allied Commission. 1946. Subcommission for Monuments Fine Arts and Archives, Final Report: General, 1 January. In Ernest DeWald Papers, Princeton University Library, Princeton, NJ, Box 5, Folder 1. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, Charlotte, and Artem Mazhulin. 2022. Sandbag Sculpture: How Kyiv Is Shielding Statues from Russian Bombs. The Guardian. October 18. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/18/sandbag-sculpture-kyiv-shielding-statues-from-russian-bombs (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Hoeniger, Cathleen. 2022. Protecting Portable Heritage during War: A Comparative Examination of the Approaches in Italy during World War Two and in Ukraine during the Russian Invasion of 2022. Text & Image: Essential Problems in Art History 1: 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeniger, Cathleen. 2024a. The Fate of Early Italian Art during World War Two: Protection, Rescue, Restoration. With Geoffrey Hodgetts. Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeniger, Cathleen. 2024b. The Recovery of Artistic Remains from the Ruins of War: Assessing the Restored Medieval Portals of San Tommaso in Ortona and San Giovanni Evangelista in Ravenna. In Difese, Distruzioni, Permanenze delle Memorie e Dell’immagine Urbana. Tracce e Patrimoni/Defences, Destructions, Permanences of Memories and the Urban Image. Traces and Heritages. v. 2. Edited by Raffaele Amore, Maria Ines Pascariello and Alessandra Veropalumbo. Naples: Cirice—University of Naples Federico II Press, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeniger, Cathleen. 2019. The Salvage of the Benevento Bronze Doors after World War Two. In The Long Lives of Medieval Art and Architecture. Edited by Jennifer Feltman and Sarah Thompson. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 245–59. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. 2023a. World Report 2023, Country Report: Syria. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/syria (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Human Rights Watch. 2023b. World Report 2023, Country Report: Ukraine. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/ukraine (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- ICOM. 2023. ICOM Member Newsletter, February. Available online: https://mailchi.mp/b294cbce847e/icom-member-newsletter-nov2022-en-2769157?e=7ec82fc33e (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- IFAR. 2023. Updated list of Ukrainian Heritage and Aid Organizations. October 13. Available online: https://www.ifar.org/news_article.php?docid=1697229268 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Il Duomo di Firenze: Documenti sulla Decorazione Della Chiesa e del Campanile Tratti Dall’archivio dell’Opera. 1909. Poggi, G., ed. Berlin: Cassirer, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- International Committee of the Red Cross. 2023. Red Cross Report: Climate Change, Environmental Degradation and Protracted Armed Conflict Are Exacerbating Humanitarian Needs across the Near and Middle East. News Report. May 18. Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/red-cross-report-climate-change-environmental-degradation-protracted-armed-conflict-exacerbating-humanitarian-needs (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Istituto Nazionale Luce. 1943. Il Trasferimento Delle Porte del Battistero di Firenze al Ricovero. May 25. Available online: https://www.archivioluce.com/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Karlsgodt, Elizabeth Campbell. 2011. Defending National Treasures: French Art and Heritage under Vichy. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, Lawrence M. 1997. Laws in Force at the Dawn of World War II: International Conventions and National Laws. In The Spoils of War: World War II and Its Aftermath. The Loss, Reappearance, and Recovery of Cultural Property. Edited by Elizabeth Simpson. New York: Abrams, pp. 100–5. [Google Scholar]

- Klinkhammer, Lutz. 1992. Die Abteilung ‘Kunstschutz’ der Deutschen Militärverwaltung in Italien 1943–1945. Quellen und Forschungen aus Italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken 72: 483–549. [Google Scholar]

- “Kristallnacht: Destruction of Synagogues and Buildings”, Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Memorial Holocaust Museum. 2019. Available online: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kristallnacht (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- La protezione del Patrimonio Artistico Nazionale Dalle Offese Della Guerra Aerea. 1942. Direzione Generale delle Arti, ed. Florence: Le Monnier. [Google Scholar]

- Law of Ukraine. 1992. Verkhovna Rada (Law of Ukraine: Basic Legislation of Ukraine on Culture). February 14. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ua_lawbasiclegislation_ukraine_culture_engtof.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Law of Ukraine. 2000. Verkhovna Rada (Law of Ukraine: On Protection of Cultural Heritage). June 8. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ua_law_protection_cultural_heritage_engtof.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Lazzari, Marino. 1942. La protezione delle opere d’arte durante la guerra. In La Protezione del Patrimonio Artistico Nazionale Dalle Offese Della Guerra Aerea. Edited by Direzione Generale delle Arti. Florence: Le Monnier, pp. v–x. [Google Scholar]

- Legge 185. 1902. June 12. In Gazzetta ufficiale del Regno d’Italia. Anno 1902, Rome, 27 June, 149: 2909–13. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/ricerca/pdf/preRsi/foglio_ordinario1/1/0/0?reset=true (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Legge 364. 1909. June 20. In Gazzetta ufficiale del Regno d’Italia. Anno 1909, Rome, 28 June, 159: 3409–13. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/ricerca/pdf/preRsi/foglio_ordinario1/1/0/0?reset=true (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Legge 386. 1907. June 27. In Gazzetta ufficiale del Regno d’Italia. Anno 1907, Rome, 4 July 1907, 158: 3993–99. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/ricerca/pdf/preRsi/foglio_ordinario1/1/0/0?reset=true (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Legge 3164. 1923. December 31. In Gazzetta ufficiale del Regno d’Italia. Anno 65, Rome, 18 February, 1924, 37: 695–700. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/ricerca/pdf/preRsi/foglio_ordinario1/1/0/0?reset=true (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Legge 823. 1939. May 22. In Gazzetta ufficiale del Regno d’Italia. Anno 47, Rome, 20 June 1939, 143: 2797–99. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/ricerca/pdf/preRsi/foglio_ordinario1/1/0/0?reset=true (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Levi, Donata. 2008. The Administration of Historical Heritage: The Italian Case. In National Approaches to the Governance of Historical Heritage over Time: A Comparative Report. Edited by Stefan Fisch. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 103–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Laurent. 2002. The action of UNESCO in Bosnia and Herzegovina to restore respect and mutual understanding among local communities through the preservation of cultural heritage. In La Tutela del Patrimonio Culturale in Caso di Conflitto. Edited by Fabio Maniscalco. Naples: Massa, vol. 2, pp. 143–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mack Smith, Denis. 1976. Mussolini’s Roman Empire. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Makar, Roksolana. 2023. Hemo: Documenting Ukrainian Heritage during the War. Presented at Cultural Rights, Heritage Destruction, and the Future of Ukraine, Penn Cultural Heritage Center, Philadelphia, USA, 7 December. Available online: https://www.penn.museum/calendar/177/penn-cultural-heritage-center-lecture (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Maniscalco, Fabio. 2002. Lacune e disattenzioni alla Convenzione de L’Aja del 1954 in un decennio di conflitti nella Peninsola Balcanica. In La Tutela del Patrimonio Culturale in Caso di Conflitto. Edited by Fabio Maniscalco. Naples: Massa, vol. 2, pp. 149–58. [Google Scholar]

- Maniscalco, Fabio. 2007. Preventive Measures for the Safeguard of Cultural Heritage in the Event of Armed Conflict. In World Heritage and War: Linee gu ida per inter venti a salva guardia dei beni cul turali ne lle aree a risc hio belli co. Edited by Fabio Maniscalco. Naples: Massa, pp. 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- McCamley, Nicholas. 2003. Saving Britain’s Art Treasures. Barnsley: Leo Cooper. [Google Scholar]

- Meharg, Sarah J. 2001. Identicide and cultural cannibalism: Warfare’s appetite for symbolic place. Peace Research 33: 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dell’Educazione Nazionale. 1923–1936. Elenco Degli Edifici Monumentali. Rome: La Libreria dello Stato, vols. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dell’Educazione Nazionale. 1931–1938. Inventario degli oggetti d’arte d’Italia. Rome: La Libreria dello Stato, vols. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture of Ukraine. 2023. ICCROM, Damage and Risk Assessment: Report to Promote Risk-Informed Cultural Heritage First Aid Actions in Ukraine. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/publications/2023-02/iccrom_far_2023_damage_and_risk_assessment_report_ukraine.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Myrie, Clive. 2022. In Kyiv, I saw Dante under sandbags—A modern image of the hell of war. The Guardian. December 12. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/dec/12/kyiv-dante-war-conflicts-russia-ukraine (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Newton, Henry. 1944. Report on the Bombing of the Duomo di Benevento. August 19, pp. 1–2, AMG-28. In NARA, RG 331. [Google Scholar]

- Nezzo, Marta. 2011. The Defence of Works of Art from Bombing in Italy during the Second World War. In Bombing, States and Peoples in Western Europe 1940–1945. Edited by Claudia Baldoli, Andrew Knapp and Richard Overy. London: Continuum, pp. 101–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, Lynn H. 1995. The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, Lynn H. 1997. World War II and the Displacement of Art and Cultural Property. In The Spoils of War: World War II and Its Aftermath. The Loss, Reappearance, and Recovery of Cultural Property. Edited by Elizabeth Simpson. New York: Abrams, pp. 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, Pierre. 1996–1998. Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past. Edited by Lawrence B. Kritzman. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. New York: Columbia University Press, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, Pierre. 2001–2009. Rethinking France: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Edited by David Jordan. Translated by Mary Trouille. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski, Teresa. 2023. Secretly Evacuated From Ukraine, Rare Icons Now on View at the Louvre. Smithsonian Magazine. June 26. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/louvre-icons-evacuated-ukraine-180982422/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Ortolani, Sergio. 1944. “Napoli e Campania: Elenco degli oggetti d’arte di maggior pregio distrutti per cause di guerra”. In NARA, RG 331, Box 1522, ACC 10000/145/31, 20031, Region III-General. September 1943–June 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrovska-Liuta, Olesia. 2022. Director, Mystetskyi Arsenal National Art and Culture Museum Complex, Kyiv. As Quoted in: S. Goodyear. This Museum Director Is Staying in Kyiv as Ukrainian Culture Comes Under Fire. CBC Radio. March 8. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/as-it-happens-the-tuesday-edition-1.6377319/this-museum-director-is-staying-in-kyiv-as-ukrainian-culture-comes-under-fire-1.6377322 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Overy, Richard. 2013. The Bombing War: Europe 1939–1945. London: Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti, Paolo. 1985. Firenze: La guerra. In Paolo Paoletti and Mario Carniani, Firenze: Guerra & alluvione (4 agosto 1944–4 novembre 1966). Florence: Becocci, pp. 7–111. [Google Scholar]

- Plant, James. 1997. Investigation of the Major Nazi Art-Confiscation Agencies. In The Spoils of War: World War II and Its Aftermath. The Loss, Reappearance, and Recovery of Cultural Property. Edited by Elizabeth Simpson. New York: Abrams, pp. 124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, Giovanni. 1945. Report [no title], 5 June, 16 pages. In Uffizi Galleries Archive, Archivio Giovanni Poggi, Florence, Series VIII, number 155, fasc. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, Nigel. 2020a. Bombing Pompeii: World Heritage and Military Necessity. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, Nigel. 2020b. Refuges for movable cultural property in wartime: Lessons for contemporary practice from Second World War Italy. International Journal of Heritage Studies 26: 667–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protecting Heritage amid War: St. Sophia’s Cathedral in Kyiv Digitized with Laser Scanner to Ensure Preservation. 2023. Rubryka. July 13. Available online: https://rubryka.com/en/2023/07/13/otsyfruvaly-lazernym-skanerom-sofijskyj-sobor-u-kyyevi-navishho-tse-rishennya/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Regio Decreto 1746. 1940. November 21. Dichiarazione di Monumento Nazionale di Chiese Cattedrali. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Religion on Fire. 2023. Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Yasnohorodka, Kyiv Oblast. Available online: https://religiononfireen.miraheze.org/wiki/Church_of_the_Nativity_of_the_Blessed_Virgin_Mary,_Yasnohorodka,_Kyiv_oblast (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Riedlmayer, András J. 2002. Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1992–1996: A Post-war Survey of Selected Municipalities. Expert Report commissioned by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. Available online: https://www.archnet.org/publications/3481 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Rosi, Giorgio. 1940. Correspondence with Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti, June-July 1940. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 68. [Google Scholar]

- Rosłan, Grzegorz. 2022. Protection of cultural heritage in an armed conflict. What Poland can learn from Ukraine? Challenges to National Defence in Contemporary Geopolitical Situation 1: 254–63. Available online: https://journals.lka.lt/journal/cndcgs/article/1971/info (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Schipani, Andres. 2022. Ukraine Battles to Protect Its Churches and Heritage from Ravages of War. Financial Times. April 15. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/b83fb574-0e2a-4ff0-bd73-d6714927e29f (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Second Protocol. 1999. Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. The Hague. March 26. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-prot-1999 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Sframeli, Maria. 2011. Giovanni Poggi soprintendente: Cinquant’anni di tutela. In L’archivio di Giovanni Poggi (1880–1961): Soprintendente alle gallerie fiorentine. Edited by Elena Lombardi. Florence: Polistampa, pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton, Caroline. 2021. National Treasures: Saving the Nation’s Art in World War II. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Skorkin, Konstantin. 2023. Holy War: The Fight for Ukraine’s Churches and Monasteries. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. April 11. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/89496 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Smithsonian. 2024. Cultural Rescue Initiative. Available online: https://culturalrescue.si.edu/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Standing with Ukrainian Museums. 2023. In “The Origins of the Sacred Image: Icons from the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts in Kyiv”, Press Kit, 13 June 2023, Musée du Louvre Exhibition, 14 June–6 November 2023. Available online: https://www.aliph-foundation.org/storage/wsm_presse/0TBTV3cGR6qZWYHwk6XaAJU4K7COY2A3RSL0jUma.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Stone, Peter G. 2023. Blue Shield Statement on Conflict in Ukraine. February 24. Available online: https://theblueshield.org/statement-ukraine-conflict-one-year-on/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Stone, Peter G. 2015. The Challenge of Protecting Heritage in Times of Armed Conflict. Museum International 67: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchiani, Nello. 1940. Telegrams and memoranda to Ministry, Rome, June–July 1940. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 92. [Google Scholar]

- Terenzio, Alberto. Correspondence with Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti, June 1940–April 1942. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 94, fasc. 1.

- Terenzio, Alberto. 1940. Salvaguardia patrimonio artistico. June 8. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 94, fasc. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ukrainian Institute. 2024. Postcards. Holy Dormition Cathedral. Available online: https://ui.org.ua/en/postcard/holy-dormition-cathedral/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO. 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. November 16. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO. 2018. Recommendations for World Heritage Recovery and Reconstruction Developed in Warsaw. May 14. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1826 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO. 2023a. Odesa: UNESCO Strongly Condemns Repeated Attacks against Cultural Heritage, Including World Heritage. July 23. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/odesa-unesco-strongly-condemns-repeated-attacks-against-cultural-heritage-including-world-heritage (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO. 2023b. Ukraine: UNESCO Sites of Kyiv and L’viv Are Inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger. September 15. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2608/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO. 2024a. Damaged Cultural Sites in Ukraine verified by UNESCO. March 13. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/damaged-cultural-sites-ukraine-verified-unesco (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO. 2024b. Ukraine’s Recovery: UNESCO Mobilizes an Additional $14.6 Million Thanks to Japan. February 7. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/ukraines-recovery-unesco-mobilizes-additional-146-million-thanks-japan (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO World Heritage List no. 527. 1990. Kyiv: Saint-Sophia Cathedral and Related Monastic Buildings, Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/527/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO World Heritage List no. 865. 1998. L’viv–the Ensemble of the Historic Centre. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/865 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO World Heritage List no. 1424. 2013. Wooden Tserkvas of the Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1424 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNESCO World Heritage List no. 1703. 2023. The Historic Centre of Odesa. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1703/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- United Nations. 2023. Over 115 Holy Sites Damaged in Ukraine Since Start of Russian Invasion, Top UN Official Tells Security Council, Urging Respect for Religious Freedom. July 26. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15366.doc.htm (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- U.S. Embassy and Consulates in Italy. 2023. Defending Ukraine’s Art and Culture from Destruction. March 2. Available online: https://it.usembassy.gov/defending-ukraines-art-and-culture-from-destruction/ (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Vasin, Maksym, Dmytro Koval, Igor Kozlovskyy, and Anastasia Zaiets. 2022. Russian Attacks on Religious Freedom in Ukraine: Research, Analytics, Recommendations. Edited by Oleksandr Zaiets and Maksym Vasin. Kyiv: Institute for Religious Freedom. Available online: https://irf.in.ua/files/publications/2022.09-IRF-Ukraine-report-ENG.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Zocchi, Oreste. 1939. Correspondence with Ministro dell’Educazione Nazionale, Direttore Generale per le Antichità e le Belle Arti, March 8. In ACS, MPI, Dir. Gen. AABBAA, Divisione II (1934–1940), busta 69. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoeniger, C. The Protection of Monuments and Immoveable Works of Art from War Damage: A Comparison of Italy in World War II and Ukraine during the Russian Invasion. Arts 2024, 13, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020065

Hoeniger C. The Protection of Monuments and Immoveable Works of Art from War Damage: A Comparison of Italy in World War II and Ukraine during the Russian Invasion. Arts. 2024; 13(2):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020065

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoeniger, Cathleen. 2024. "The Protection of Monuments and Immoveable Works of Art from War Damage: A Comparison of Italy in World War II and Ukraine during the Russian Invasion" Arts 13, no. 2: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020065

APA StyleHoeniger, C. (2024). The Protection of Monuments and Immoveable Works of Art from War Damage: A Comparison of Italy in World War II and Ukraine during the Russian Invasion. Arts, 13(2), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020065