Abstract

By way of an analysis of Simone Leigh’s You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been (2017), this essay argues that by hybridizing the cowrie and watermelon, Leigh creates her own natural history of these biological forms that disorders the rigid taxonomic classification on which systems of discrimination rely. The resulting hybrid cowrie not only defies classification, it also forms a folded architecture that facilitates a Deleuzian reading. The hybrid cowries, by way of their capacious construction and narrow slits, evoke an interiority that enables metamorphosis. By way of the analysis of the works of Cupboard (2014) and Cowrie (Pannier) (2015), the essay further investigates architectural forms. It considers the intricate interactions between the hybrid architecture of natural forms, such as cowries and watermelons, and human-fabricated forms, such as teleuks and crinolines.

Keywords:

African art; Simone Leigh; African–American art; cowrie; ceramics; sculpture; ecology of form; animals; architecture Simone Leigh’s hybrid cowrie sculptures challenge viewers to explore the intersections between natural and human histories and invite them to contemplate themes of identity, interiority, and metamorphosis within the context of diasporic histories. Leigh’s sculptural practice makes use of materials, processes, and forms that function intertextually. Her works often incorporate elements historically found in West African art, such as clay, bronze, raffia, and cowrie shells. Moreover, Leigh’s pieces evoke the traditional processes and forms associated with ceramics, sculpture, and architecture from West African and Black diasporic cultures. A hybrid cowrie and watermelon ceramic form is a motif seen across Leigh’s body of work. After being molded from hollowed-out watermelon, the clay forms are cut open to different degrees such that their openings resemble the toothy gape of the underside of a cowrie shell. Cowries and watermelons were dispersed intercontinentally during the period of the transatlantic slave trade, and Leigh intends to connect her hybrid cowries to the history of this trade and the Black diaspora that arose as a consequence of it. Leigh has stated clearly that knowledge of colonial history, specifically as it relates to the Black diaspora, is necessary in order to recognize the “radical” gestures in her work. She posits a form of interpretation that relies on the accumulation of a vast amount of knowledge by the viewer; the object then draws on this accumulation in the viewer’s mind to form multiple intertextual connections (Leigh 2019). For this reason, when interpreting Leigh’s work, this essay will recount the colonial histories of the various objects and forms to which she refers.

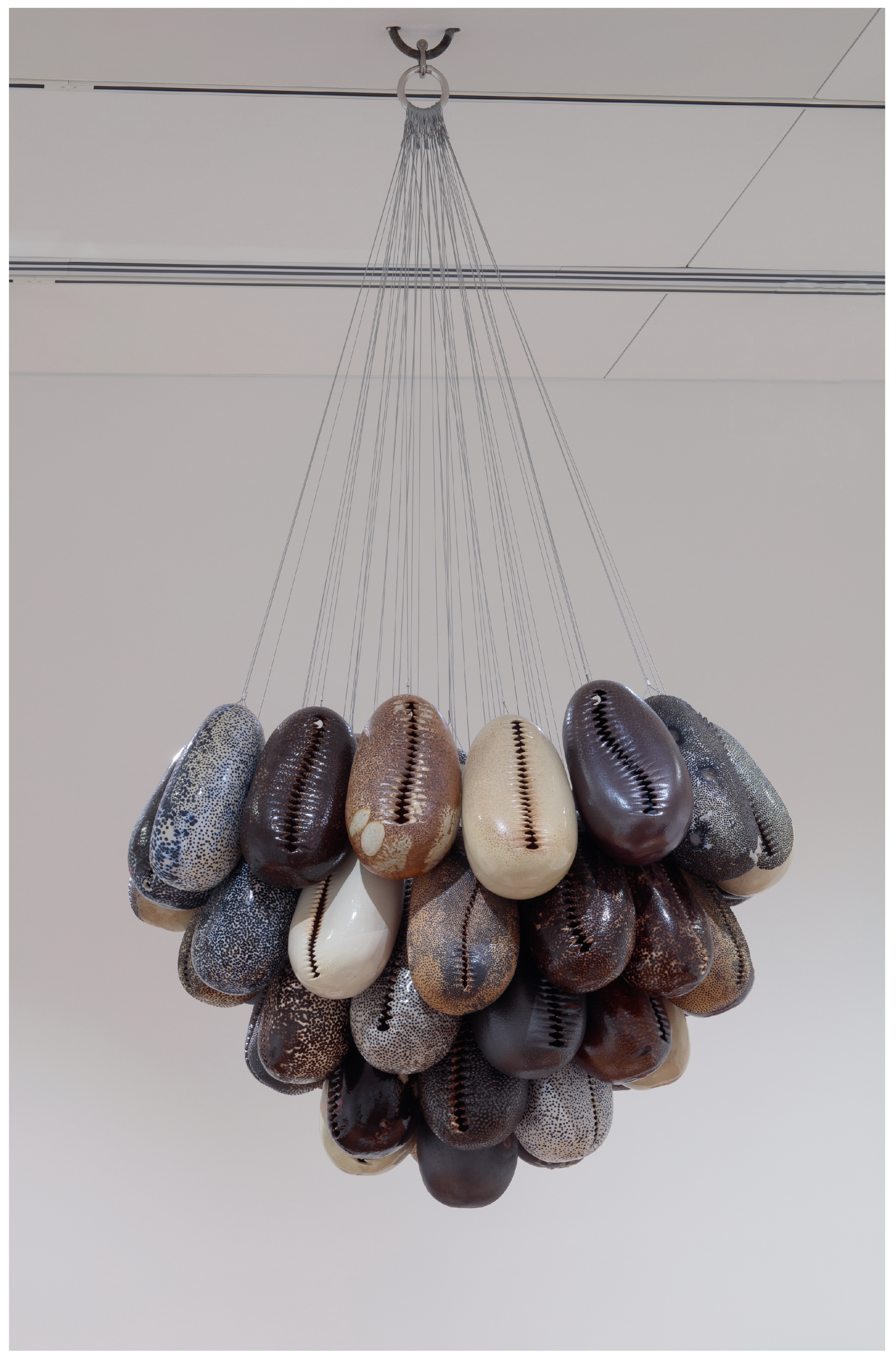

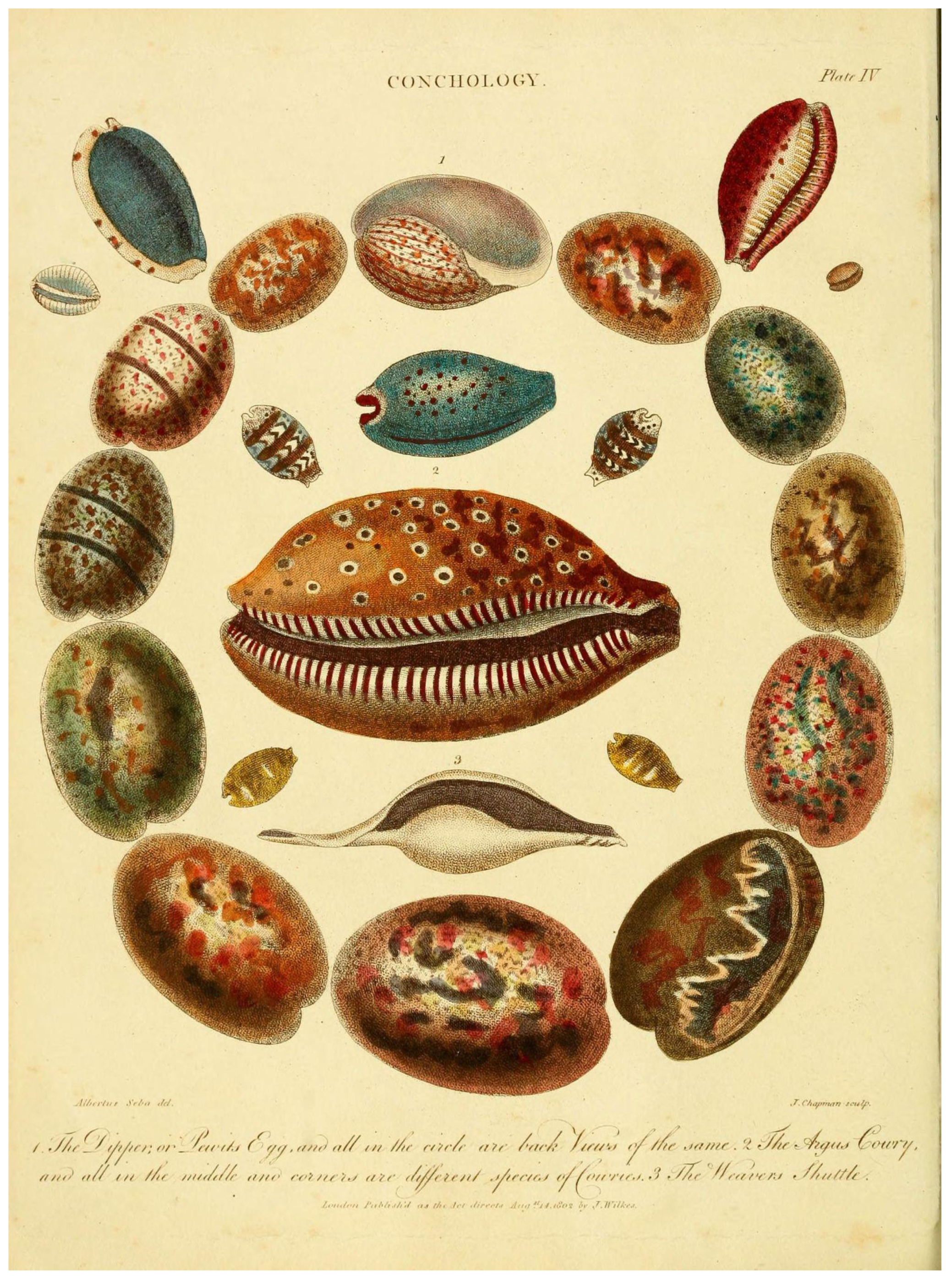

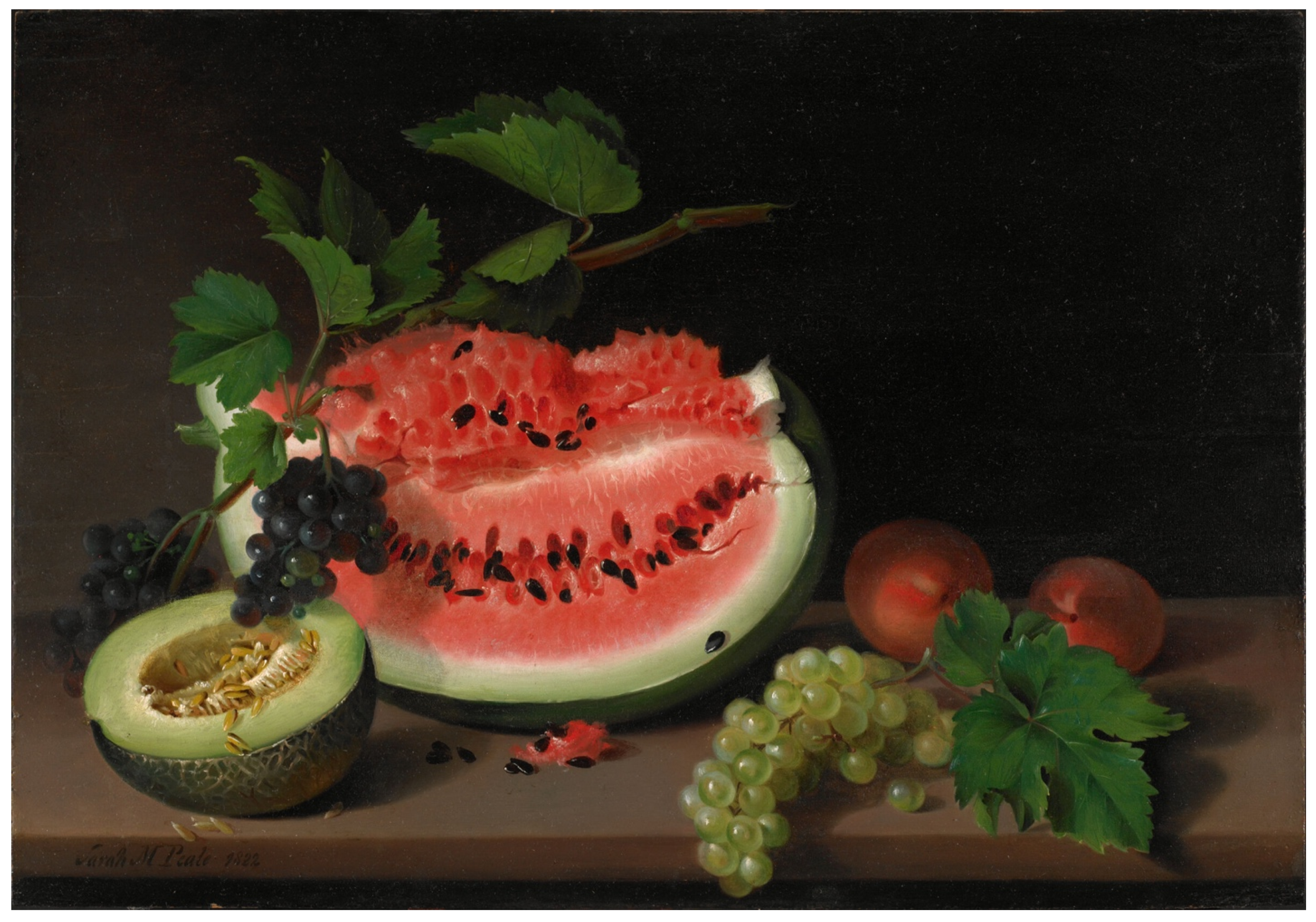

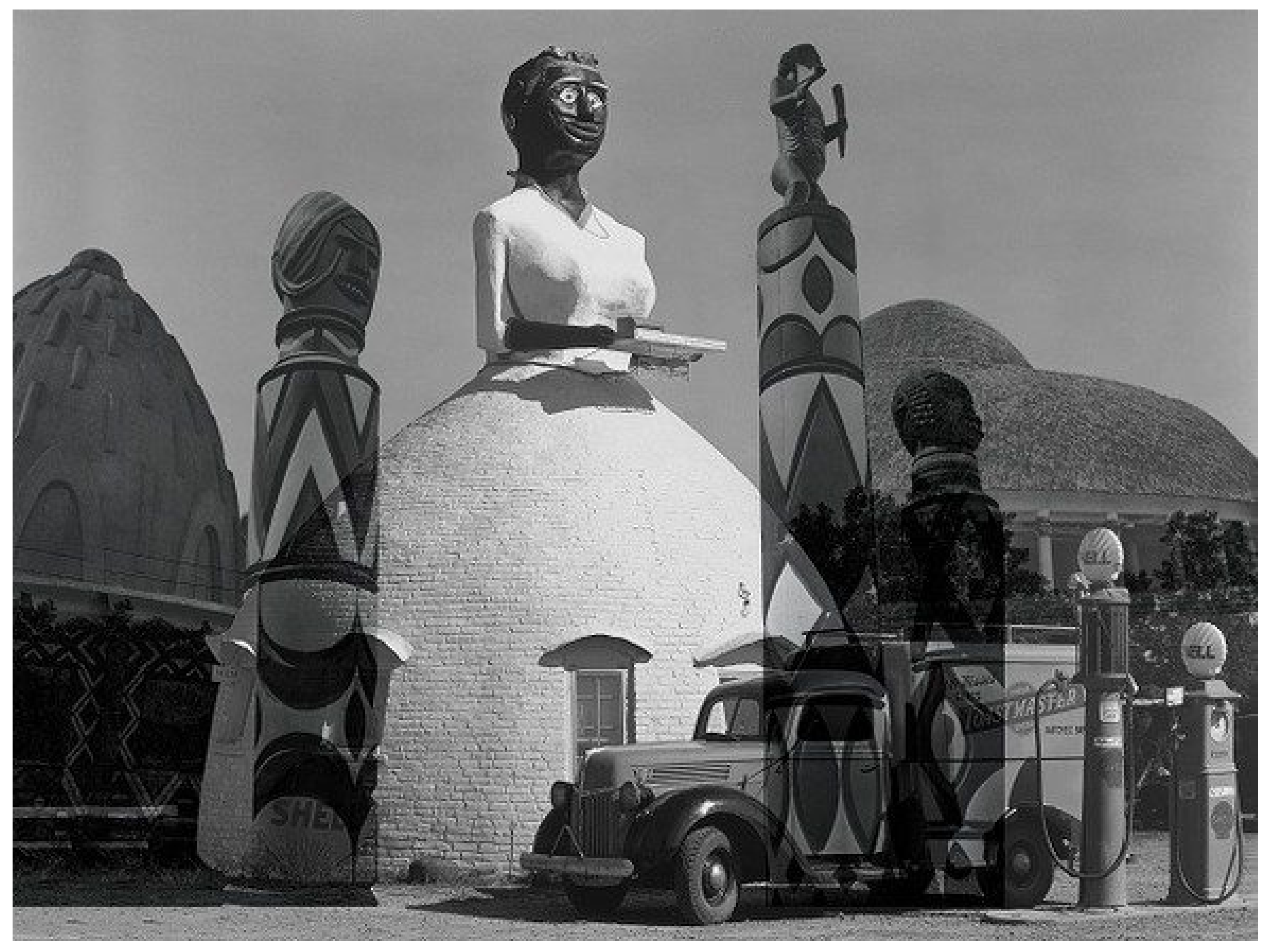

The slickness of clay, the sweet and sticky juiciness of watermelon, and the salty sea where cowries propagate come together in You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, 2017 (Figure 1). The title suggests an ambiguous erotic narrative, where the subject of the title is either derided as sexually impure or celebrated as sexually liberated. The work comprised a cluster of ovate stoneware and porcelain hybrid cowrie forms glazed in shades from maroon to ivory. The clustering of cowrie forms in You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been suggests the anatomy of biological reproduction—vulvae, breasts, phalli, fruits, eggs, seeds, and spores. The cluster, suspended from the ceiling on wires, is arranged in symmetrical circular tiers of decreasing circumference, recalling the growth patterns of fruits. Each cowrie rests atop and against the others. The “stringed” cluster refers to the cowrie’s historical use as jewelry, ornament, talisman, and currency (Lagasse 2018). The suspension also orients the viewer on the underside of the work. This approach is unusual, asking the viewer to look up instead of to the walls or the floor, as is typical in a gallery. Leigh has introduced a hierarchy, wherein we are positioned beneath the work. The orientation also prevents us from viewing intimately the details of the work, such as the raised black dots on some of the cowries created with black slip. The arbitrary method of their placement produces an organic appearance akin to the variety of color patterns seen on the shells of the Cypraeidae, the family of marine snails to which cowries belong (Figure 2). The variegated coloring of the stoneware and porcelain hybrid cowries is a product of introducing salt into the kiln, which vaporizes at the height of firing and produces chance effects.1

Figure 1.

Simone Leigh, You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, 2017. Sixty-five stoneware and porcelain cowrie-shaped sculptures, 15 × 10 ft. The Newark Museum of Art, Newark, New Jersey. Helen McMahon Brady Cutting Fund.

Figure 2.

“Conchology”, Plate IV, Encyclopaedia londinensis, or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, 1810.

This essay argues that by hybridizing the cowrie and watermelon, Leigh creates an object that inspires an imaginary natural history that disorders the rigid taxonomic classification on which systems of discrimination rely. Moreover, the hybrid form subverts and destabilizes historical watermelon imagery employed to reinforce black stereotypes. The hybridization of these two forms is particularly effective because watermelons and cowries historically served as easily reproduced reservoirs of stored value—economic, nutritional, cultural, political, and aesthetic. Watermelons functioned as “botanical canteens” in arid climates, and cowrie shells were used as a form of currency at the height of the slave trade (Kiple and Ornelas 2000). The hybrid cowries work as slippery metaphors for the slave economy’s transformation of unique individuals with interiorities into slave bodies with stored labor values. Carla L. Peterson writes that “within both economic systems of slavery and free labor, the black body was made to perform as a laboring body, as a working machine dissociated from the mind that invents or operates the machine.” (Bennett et al. 2001, p. 11). The hybrid cowries, by way of their capacious construction and narrow slits, evoke interiority connected to conceptualizations of the self that rely on concealment. This insistence on interiority is significant in relation to historical denials of black interiority (Bennett et al. 2001, p. 11). The cowrie hybrid forms a new architecture that protects interiority and resists dehumanization—a folded interior space within which, in Maria del Guadalupe Davidson’s words, “black female identity can interact with itself and bring about a convergence between the outside and the inside of thought.” (Davidson et al. 2010, p. 131). Ultimately, the hybrid cowrie evades complete knowing, given that its interiority is one of partial concealment. In addition to appearing singly, as part of installations, and in suspended clusters, Leigh’s hybrid cowries appear atop and within hemispherical armatures that recall multiple forms—Mousgoum teleuks, termite hills, granaries, cages, fish traps, crinolines, and panniers—to name only a few. In works such as Cupboard (2014) (Figure 3) and Cowrie (Pannier) (2015) (Figure 4), this hybrid architecture of natural forms, such as cowries and watermelon, interacts in complex ways with the hybrid architecture of forms fabricated by humans, such as teleuks and crinolines.

Figure 3.

Simone Leigh, Cupboard, 2014. Porcelain, stoneware, wire, and steel, 216 × 144 inches. © Simone Leigh, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

Figure 4.

Simone Leigh, Cowrie (Pannier), 2015, terracotta, porcelain, and steel, 58 × 54 × 32 inches (147.3 × 137.2 × 81.3 cm), Collection of Jonathan and Margot Davis. © Simone Leigh, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

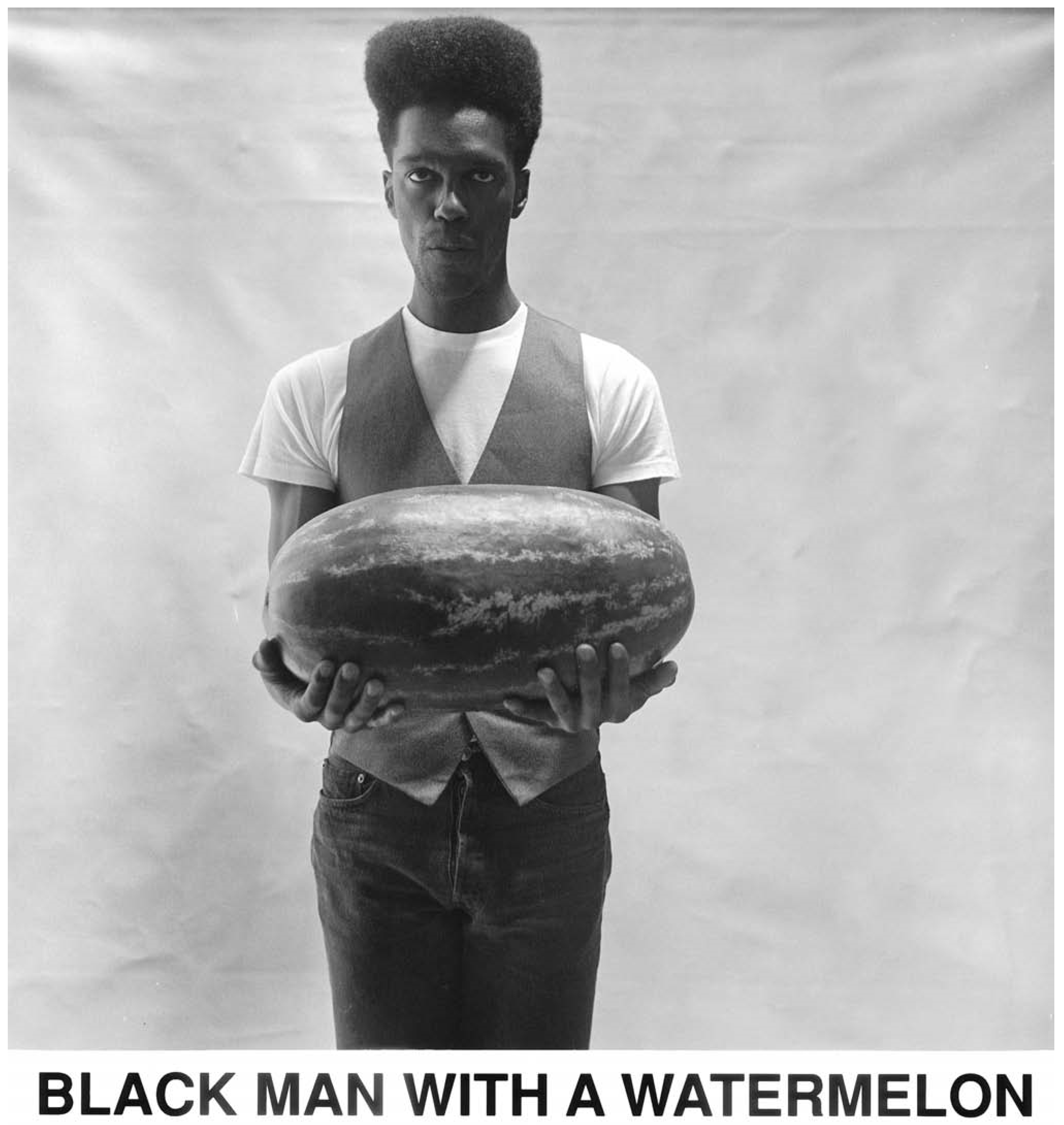

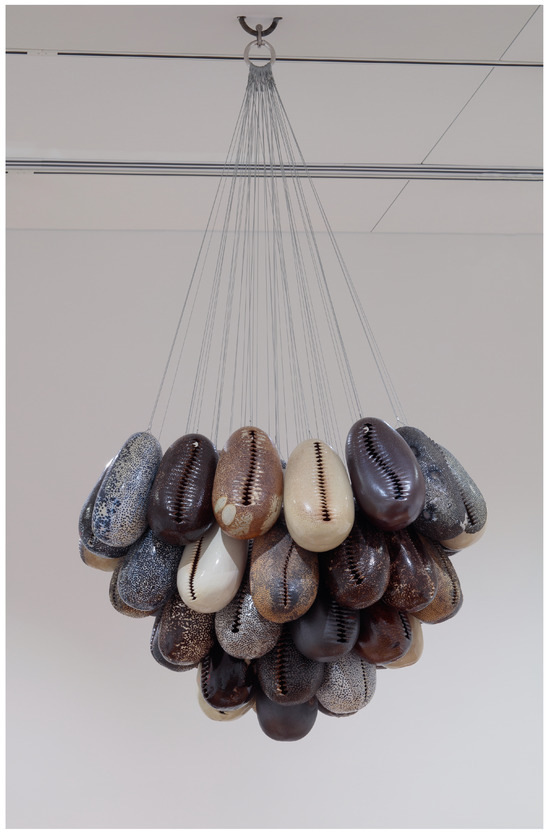

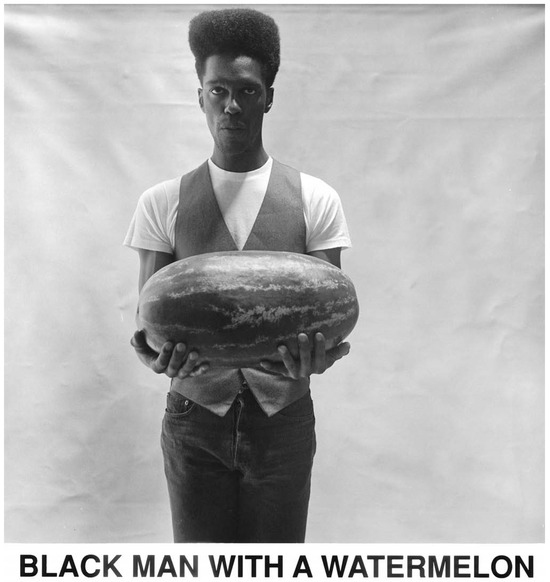

By using watermelon rinds to mold her cowrie forms, Leigh addresses the sticky history of the watermelon’s use in racist iconography. The hybrid shape challenges and undermines historical watermelon imagery that is used to support negative black stereotypes. “I could have used any gourd to make molds”, Leigh has remarked. However, she chose the watermelon for its “kind of preternatural” qualities and saw her sculptures as opportunities to “rewrite the watermelon” into a new narrative. She explains that the watermelon carries connotations aligned with derogatory descriptions of the female black body as “too large, overgrown, fat” often caricatured in objects, such as mammy cookie jars and teapots (Caruth n.d.). In a photograph from 1930s Moengo, Surinam, it is evident that in a colonial context, the watermelon is associated with the black female body and its sexuality (Figure 5). Moengo was a mining city and sundown town where the Americans and Dutch were segregated from Afro-Surinamese, descendants of Africans brought to work on sugar plantations as slaves. The man in the center of the photograph, a manager of a Dutch mining company, bites into a slice of the watermelon as if he is eating a slice of the black servant. She holds this watermelon, a symbol of sexuality and fecundity, in place of a chubby white child. The photograph’s composition suggests that the man goes back and forth between the two women, one for erotic pursuits, and the other for reproducing the white colonial body. The back of the photograph has an inscription in pencil that reads, “Look at the large watermelon that the servant is holding in her hand.” Leigh describes the effect of the watermelon image beside a black body as akin to a filmic montage. “It’s one of the few forms I can think of that’s actually an insult. You can put a watermelon next to a black body, and that’s an insult. You don’t have to change or do anything to it to have this content.” (Chun 2014). Carrie Mae Weems illustrated this point in her contemporary photograph, Black Man with A Watermelon (1987) (Figure 6). Part of her Ain’t Jokin’ series, the photograph, addressed “America’s obsession with classifying people according to race and ethnicity, as well as the perpetuation of racial stereotypes through American humor.” (Patterson 2001).

Figure 5.

Echtpaar Guilonard met kind en een bediende in Moengo, 1930, Photograph, 11.5 cm × 8.5 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Jaarverslag. Purchased with the support of the Maria Adriana Aalders Fonds/Rijksmuseum Fonds.

Figure 6.

Carrie Mae Weems, Black Man with A Watermelon, 1987–1988. Gift of the Estate of Lester and Betty Guttman. Photograph ©2024 courtesy of The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago.

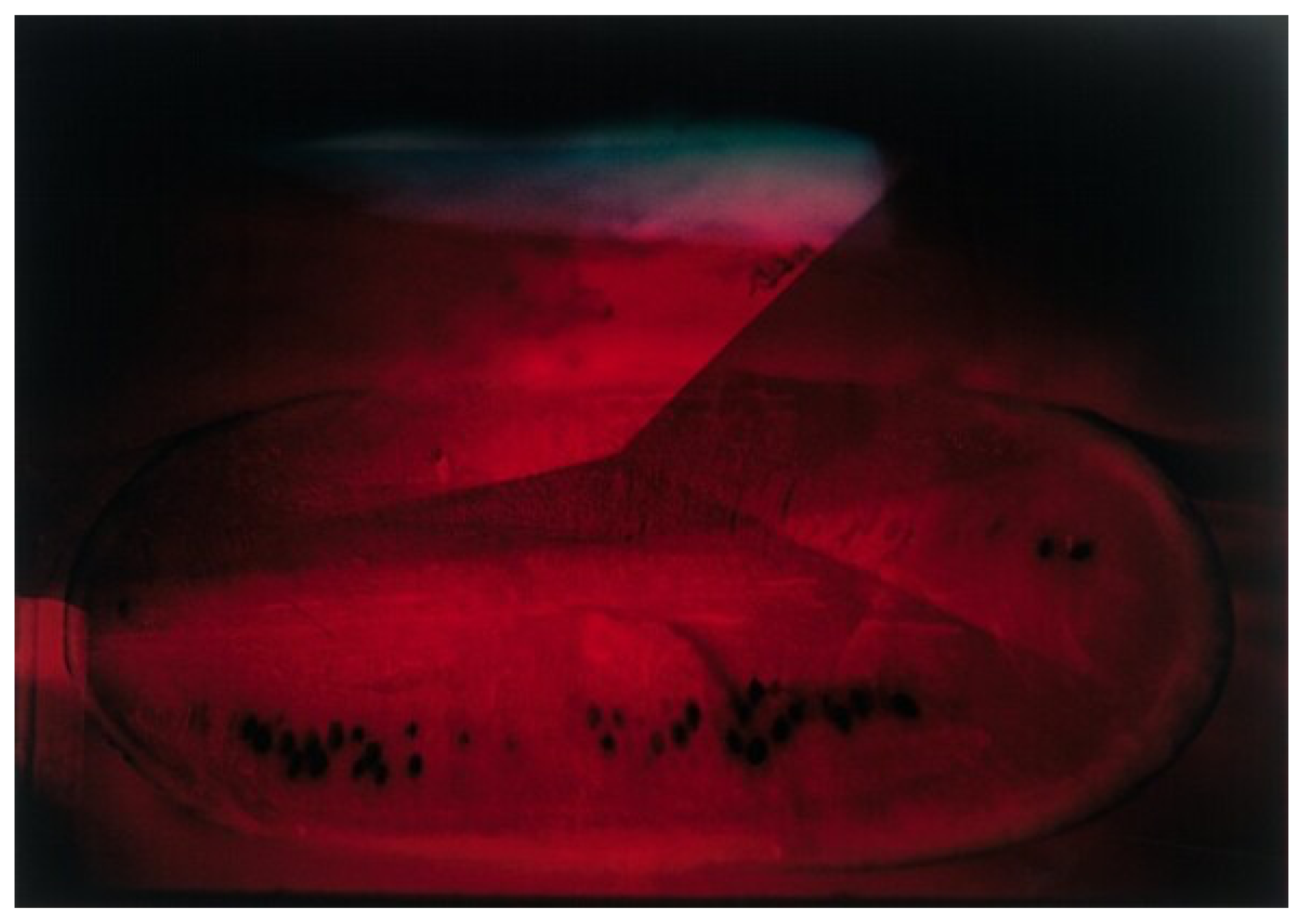

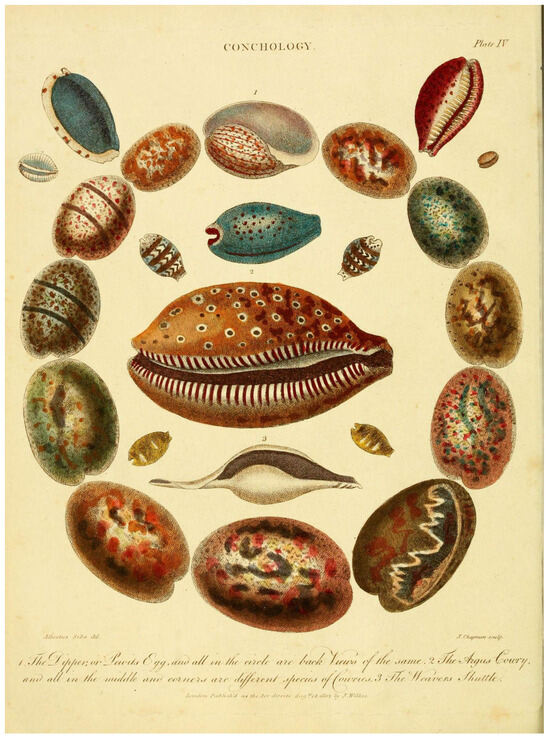

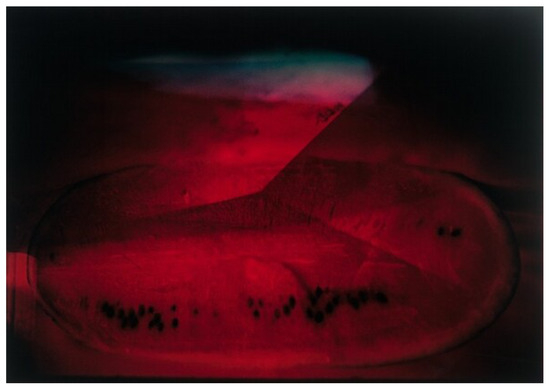

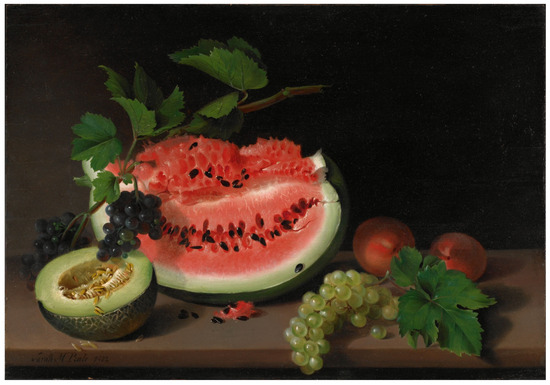

Other artists have focused on overtly reclaiming the watermelon from the stereotype. For example, Gordon Parks’s vibrant dye print casts the watermelon into shadow and renders it abstract (Figure 7). In the film The Watermelon Woman, black lesbian filmmaker Cheryl Dunye sees the watermelon, in Michele Wallace’s words, “not as a symbol of shame but of abundance; and the mammy figure not as an image of denigration but as a bountiful goddess figure.” (Wallace 2004, p. 459). Moreover, Dunye casts the watermelon and the mammy as symbols of black lesbian desire, thereby queering the traditional interpretations of both. Leigh and Dunye’s casting promotes against-the-grain readings of heteronormative works, such as Sarah Miram Peale’s Still Life with Watermelon (1822) (Figure 8), in which we can easily perceive an erotic and reproductive implication that is gendered. In Peale’s painting, the watermelon is split open, its fleshy red interior exposed and dripping with glistening seed. A cluster of black grapes, similar in arrangement to the cluster of hybrid cowries in You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, leads us down into the hollow of the honeydew melon, likewise abundant with seed. The ambiguity in Leigh’s title, You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, indicates that she invites both perspectives into her work—both the critique of colonialist and racist discourses and the embrace of the watermelon and mammy as objects of love and desire. By hybridizing the watermelon with the cowrie, Leigh’s You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been both highlights and drowns out—or rewrites—the racist meaning of this iconography by transforming it and proliferating its intertextual associations. As in dream imagery, we paradoxically encounter both a concentration and dilution of meaning. The effect runs counter to that of stereotype and classification, where clear identities and boundaries are sought and fixed.

Figure 7.

Gordon Parks, Watermelon, c. 1967–1969. Dye Imbibition Print. Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Figure 8.

Sarah Miriam Peale, Still Life with Watermelon, 1822. Oil painting. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Daniel A. Pollack, Class of 1960, American Art Acquisition Fund.

Because watermelons and cowries have historically functioned as readily replicable repositories of stored value, Leigh’s hybridization of these two forms is intertextually productive. The hybrid cowries serve as enigmatic allegories for how the slave economy transformed unique individuals into slave bodies with stored labor values. Leigh’s use of the cowrie points to complex iconography that touches on African art, religion, and the economy of the slave trade, and knowledge of this iconography contributes to a fuller interpretation of the significance of her decision to employ the hybrid cowrie form.

The cowrie shell has historically vacillated between its state as a biological being and its state as money or representation. As opposed to having inherent value, money has been widely theorized as symbolic and linguistic in nature; it gains its meaning through a system of representations and the ascription of a transcendental value. The porousness of the cowrie’s status as subject and object (or commodity) is likewise evident in the slave, a commodity “who spoke”, as Fred Moten puts it, and who then threw into crisis the delimitation between subject and object necessary for commodification. Moten notes that in slave narratives “blackness marks simultaneously both the performance of the object and the performance of humanity.” (Moten 2003, p. 2)

In her analysis of the cowrie trade in the sixteenth century, Justine Wintjes likewise acknowledges the transformation of a cowrie from a living organism to a symbolic form, indicating why the cowrie can successfully function in Leigh’s work as a symbol for the dehumanization slavery left in its wake. “Each cowrie represents a life, however seemingly small and unrelatable to human experience. Each life was implicated in a web of relationships—the shell is but a hollow skeletal remnant of the once more complex living organism. Although occurring fully formed in nature, a cowrie had to undergo a process of physical transformation (cultivation, harvesting, and cleaning), as well as conceptual transformation, to become usable as currency—a tiny material vessel harbouring an abstract value.” (Wintjes 2020). Wintjes correctly remarks that each cowrie, a singular animal, represents a life unrelatable to human experience; we are unable to know the interiority of the cowrie. Following Jacques Derrida, we can conclude, “For thinking concerning the animal, if there is such a thing, derives from poetry” (Derrida and Mallet 2008, p. 7). Behind the gaze of an animal, he continues, there is a “bottomlessness… uninterpretable, unreadable, undecidable, abyssal, and secret.” (Derrida and Mallet 2008, p. 12). Grasping the perspectives of animals and other non-human biological beings is therefore impossible. However, “poetic” thinking, whether in the form of words or sculpture, allows us to imagine how cowries and watermelons matter in ways beyond how humans interact and think about them.

Cowries, specifically Cypraea moneta, functioned as currency for thousands of years within the Indo-Pacific realm. The first imports of moneta cowries into West Africa arrived in Benin from the Indian Ocean via Lisbon in 1515 (Ogundiran 2002, p. 438). Thereafter, until the third quarter of the nineteenth century, their use expanded to Atlantic commercial networks and at least 30 billion cowries were transported to the Bight of Benin (Ogundiran 2002, p. 429). Throughout the centuries of the sea-borne slave trade originating from West Africa, cowries were directly bartered for slaves. This led to cowries being referred to as “slave money” in the Bight of Benin (Ogundiran 2002, p. 440). In North America, archaeologists have excavated cowrie currency in colonial ports that served the transatlantic slave trade. As artworks that are bought and sold, Leigh does not remove her cowries from an economy of monetary exchange. In You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, Leigh strings up her cowries, echoing the way that cowrie currency was stored. However, the hybrid cowrie is also brought into the realm of sculpture and its characteristics are understood within an expanded context that involves the exchange, not only of money, but of meaning between artist, material, and viewer.

Cowries were not just currency, however. They also functioned as amulets in cultures across the globe since at least the bronze age (Hildburgh 1942). Evidence suggests that in many ancient cultures, the cowrie was worn as a fertility amulet, as a result of its resemblance to the vulva, and as an amulet to ward off the “evil eye”, envy, and witchcraft, as a result of its resemblance to a closed eye (Hildburgh 1942). In this way, the cowrie shares erotic and reproductive implications with the watermelon. These amulets were fashioned of bronze and clay or consisted of cowrie shells in metal settings. Akinwumi Ogundiran, a Nigerian archaeologist, anthropologist, and historian, argued that the “monetization of cowries increased the range of their cultural attributes as these imported sea shells were recontextualized not only as the symbol of wealth but also as the embodiment of fertility, abundance, and self-realization. Likewise, their supply route, the ocean, assumed a central image in the discourse of material accumulation and wealth.” (Ogundiran 2002, p. 442). In West Africa, cowries were used for divination and as currency well into the twentieth century. In 1940, an anthropologist reported that in Nigeria, cowries were deposited in graves to serve as money for use in the next world (Meek 1940, p. 62). The same anthropologist reported that the Jukun tied cowries around a child’s neck so that evil spirits might be “deceived into thinking that the child was a slave (bought with cowries) and therefore unworthy of attention.” (Meek 1940, p. 63). Understanding You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been as a talisman or object to aid divination, challenges Western assumptions about the status and purpose of contemporary art objects.

Tracing the use of the cowrie in the African diaspora, Nivaldo a Léo Neto et al. conducted an ethnozoological study on how aquatic biological resources are used in Brazil’s Candomblé (houses of worship), an Afro-Brazilian religion introduced during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by enslaved Yoruba. The prevalence of exotic cowries in Candomblé ritual, such as Erosaria caputserpentis, Monetaria annulus, and M. moneta, indicated the importance of these species in regional and global trading (Léo Neto et al. 2012, p. 2). These two types of cowries were used in the shell toss (jogo de búzios), as ornaments, and in altars and liturgical objects (Léo Neto et al. 2012, p. 3). The jogo de búzios represents the means by which the faithful can enter into contact with divinities (Orixás) and consult their futures (Odu). According to Neto et al., “The utilization of mollusks in Candomblé is strongly influenced by ancient Yoruba myths (Itãs) which, having survived enslavement and generations of captive labor, continue to guide the lives of Brazil’s African Diaspora.” (Léo Neto et al. 2012, p. 1). Thus, the cowrie form utilized by Leigh is one that offers a means of exchange and communication between humans and the pantheon of African divinities. Leigh’s hybrid cowries resemble E. caputserpentis, the species known as the African shell. According to Neto et al., this shell holds significant importance as it is associated with the “land of the ancestors.” Due to the challenges of importing liturgical animals and plants during the slave trade, any African species that managed to arrive or were already present in Brazil, whether wild or domestic, held a nearly sacred status (Léo Neto et al. 2012, p. 5).

Leigh’s hybrid cowries offer a counterpoint to the way in which economies of exchange depend on objects of the natural world to maintain fixed identities—void of interiority—that work to legitimize those same economies at the expense of the object’s self-definition and internal multiplicity. The proliferation of cowrie forms in Leigh’s work is reminiscent not only of the human practice of collecting cowries but of the cowries’ natural reproduction, which is self-oriented and has no regard for a human economy of exchange. The hybrid cowries thereby allow for imagining an object’s natural history “before” it acquired cultural meaning. In “Resistance of the Object”, Moten addresses a similar idea of “before” within the context of the commodity. He writes, “To think the possibility of an (exchange-)value that is prior to exchange, and to think the reproductive and incantatory assertion of that possibility as the objection to exchange that is exchange’s condition of possibility, is to put oneself in the way of an ongoing line of discovery, of coming upon, of invention.” (Moten 2003, p. 11). This is precisely what Leigh’s cowrie forms prompt viewers to put themselves in the way of—discovery, arrival, and invention. Through her hybridization of non-human biological beings that store value, Leigh reminds us that subjects and objects, subsumed by economies of exchange, retain enigmatic and fluid meanings that are unknowable by that economy. Even though the viewer is given the tantalizing sense that we may have access to the hybrid cowries’ interiority through their toothy slits, we are still faced with the unknowability of others’ interiors because Leigh’s cowrie forms are largely closed off to vision.

The importance of the cowrie to human imagination and fashioning opens up an opportunity to consider Leigh’s hybrid cowries alongside Dipesh Chakrabarty’s thesis that it is necessary to collapse the traditional humanist distinction between natural history and human history. Historically, it had been thought that nature did not have a history because it had no “inside”, or internal motivation, that could be separated from an external event. The events of nature were perceived as simply events and not as acts by agents that historians could analyze by way of attempting to discern the thoughts and motivations of an agent (Chakrabarty 2009). Some humanists posited that nature could have a history, but only insofar as we could see ourselves in nature. Chakrabarty summarized the upshot of this view when he wrote, “What exists beyond that does not ‘exist’ because it does not exist for humans in any meaningful sense.” (Chakrabarty 2009, p. 203). Similarly to Chakrabarty, Devin Griffiths calls for a “renewed philosophical ecology that looks backward as much as forward and that does not so much carve out an exception for human values as place them in relation to forms of value beyond (and not simply for) the human.” (Griffiths 2021, p. 93).

The anatomy of the Cypraea moneta is characterized by slippage, dissolution, accumulation, and layers of interiority. While alive, the cowrie’s shell usually remains hidden beneath its sizable mantle, a soft and protective covering that secretes the substance forming its shell. However, the glossy shell is sometimes visible through a slit across the top of the mantle, mirroring the slit across the underside of the shell (Figure 9). In the case of Cypraea moneta, the mantle has zebra-like deep brown stripes and white pallial tentacles. As the cowrie moves across the ocean floor on its foot, the mantle envelops its pale-yellow shell. As the organism grows, the inner whorls of the shell dissolve, and the lime from this dissolution is used to expand the outer whorl of the shell (Lagasse 2018). The architecture of the Cypraea moneta’s shell is a product of perpetual and internal recycling.

Figure 9.

Money cowrie (Erosaria moneta, Cypraea moneta, Monetaria moneta), blickwinkel/Alamy Stock Photo.

Cypraaea moneta illustrates Griffiths’s argument in “The Ecology of Form”, in which he calls for an understanding of form that disrupts the traditional notion of form as a container. As an alternative, he theorizes form as ecological, shaped through networks of relation and material (Griffiths 2021, p. 71). Form is produced as it bumps up against things outside of itself, which incidentally become parts of itself by way of this encounter. Notably, You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been relies on the “bumping” of multiple hybrid cowrie forms to support its overall architecture. Griffiths encourages us to consider what forms bring into relation, and what they repeat. He means for us to consider their histories, what they bring into the present and what they echo or duplicate (Griffiths 2021, p. 84). He writes, “It is a question of the relations between the things and the world—the contents and the extants—and their place in a wider network of examples, echoes, and repetitions.” (Griffiths 2021, p. 84). Griffiths’s conception of form encourages us to think more explicitly about artistic forms as the product of networks of relation and material, repetitions, and echoes.

Griffiths’s call to acknowledge the value of forms beyond human values dovetails with Maria del Guadalupe Davidson’s ideas about power and human subjectivity. In “Rethinking Black Feminist Subjectivity: Ann duCille and Gilles Deleuze”, she writes that “though power knows much about the subject, it does not know all, and more importantly… there is an internal world that is almost impossible to penetrate from the outside.” (Davidson 2006, p. 132). Leigh’s folded ceramic forms speak to the human subject’s ability to evade power by way of creative metamorphosis within an interior space of the self and to the value of forms beyond the human. Davidson argues that the fold creates an internal space for positive subjectification that culminates in “the right to difference, variation and metamorphosis.” (Stivale 2011, p. 194). This space, while internal and private, is permeable and open to history and the future.

Leigh’s cowries materialize the characteristics Davidson imagines. As abstract forms, the cowries involve the laying of a flat piece of clay, called a slab, within a concave shape that functions as a mold, in this case, a hollowed-out watermelon. The cowrie’s curve is the result of this slab settling into each half of the watermelon mold and folding in on itself. The two halves of the oblong form are then slipped, or joined, together, and when the clay reaches what is called a “leather” stage, the toothy opening into the interior of the form can be cut and shaped. In this way, the hybrid cowrie form functions as a model for an interior space in which, in Davidson’s words, “black female identity can interact with itself and bring about a convergence between the outside and the inside of thought.” (Davidson et al. 2010, p. 131). The interior and exterior of the form are coterminous.

Davidson explains that Deleuze’s notion of the fold is useful to her because it offers a site of creative resistance for subjects who are, due to historical circumstances, unable to self-define, to become themselves, or to create themselves anew due to the pressures of social forces (Davidson et al. 2010, p. 128). In other words, the fold provides a way to conceptualize a space to encounter oneself and to create a positive identity that differs from the identity imposed by external, marginalizing forces (Davidson et al. 2010, p. 130). To support this point, she quotes Deleuze, who writes, “It is as if the relation of the outside folded back to create a doubling, allowed a relation to oneself to emerge, and constitute an inside which is hollowed out and develops its own unique dimension.” (Davidson et al. 2010, p. 130). Davidson is interested in a positive notion of difference wherein, instead of being a product of a relation to something else, as in a commodity relation, there is “the right to difference, variation, and metamorphosis.” (Stivale 2011, p. 194). Deleuze embedded his concept of the fold with his concept of the Baroque, arguing that in the worldview of the Baroque the soul and the body are indissociable. The soul, then, “discovers a vertiginous animality that gets it entangled in the pleats of matter” (Lahiji 2006, p. 63). If we consider the hybrid cowrie a body with a soul, or interiority, it is an interiority that is entangled in the matter of clay and the concept of animality.

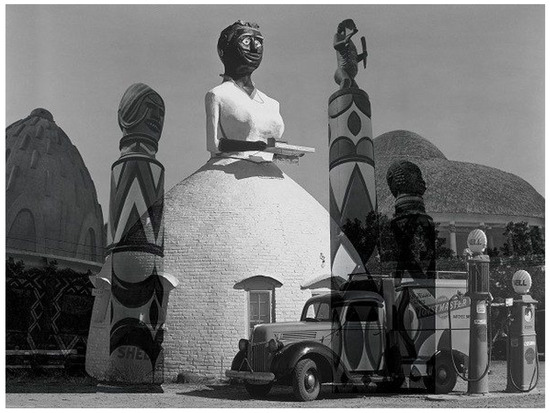

Thus far, this essay has focused on how the hybrid cowrie functions as a form in isolation or in multiple. It is important to recognize, however, that Leigh also subsumes and juxtaposes her hybrid cowrie forms beneath and above other architectures. The understanding that Leigh’s hybrid cowrie forms convey interiority contributes to our understanding of how the hybrid form relates to these architectures. In Cupboard (2014), a globular cluster similar to You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been is suspended from a hemispherical armature that follows the form of a hoopskirt. Cupboard specifically refers to Edward Weston’s photograph, Mammy’s Cupboard, Natchez, Mississippi, 1941. Mammy’s Cupboard was a roadside restaurant, and the structure was a key reference point in Sovereignty, Leigh’s exhibition at the 2022 Venice Biannale. Leigh has also incorporated Weston’s photograph into a collage alongside reconstructions of West African architecture built for the 1931 Exposition coloniale international in Paris, indicating that she is interested in collapsing the hoopskirt form with colonialist reconstructions of the teleuk (Figure 10). In Cupboard, the cluster of cowrie forms is positioned where a woman’s reproductive organs are located in relation to the hoopskirt form. Leigh invites the viewer to enter this cage-like structure in which stand-ins for reproductive organs are dangled above us like ripe fruit ready to be picked. This allows for the viewer’s reperformance of the action of entering Mammy’s Cupboard. The patron/viewer enters the area beneath a woman’s skirt to eat—raising connotations of nourishment and erotic pleasure. Leigh sees this entering as a form of violence, however, and conceives of the hoopskirt form as carrying the potential for “concealment, gathering, and invasion.” (Respini 2022, p. 16).

Figure 10.

Simone Leigh, Landscape, from the series “Anatomy of Architecture”, 2016. Digital collage. © Simone Leigh, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

At the same time that Cupboard (2014) evokes captivity and display (such as the display of animals or humans in zoos or fairs), it also evokes African domestic architecture and “gathering.” In this way, Cupboard (2014) leaves itself open to additional readings, allowing the viewer to experience a sense of captivity that is layered with a sense of maternal embrace or protection. The work, then, has something in common with that of Louise Bourgeois’s Spider (1997) or Crouching Spider (2003), in that, it imagines a multifaceted, and psychologically complicated, maternal being who surrounds and creates cages and which must be rehabilitated due to her reputation as a killer (Reichek 2008). Cupboard (2014) is a sculpture that “becomes architecture by way of becoming a structure one can enter”, to borrow Josef Helfenstein’s words on Louise Bourgeois’s Articulated Lair (1986) (Bourgeois and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía 1999, p. 25). Leigh shares Bourgeois’s interest in hybridizing the human body and architecture, evidenced in well-known works such as Femme Maison (1947) and Portrait of Jean-Louis (1947). Cowrie (Pannier), (2015) repositions the hybrid cowrie to achieve this effect. In this work, the hybrid cowrie appears singly and occupies the place of the head or torso (with exposed ribs or corset ties) in relation to the pannier. A pannier is a basket, or a pair of them carried by a beast of burden, and the term was taken up to describe a frame that supports a skirt looped up around the hips. The term is thus an example of the collapse of femininity with the ideas of labor and container.

Leigh’s engagement with Yoruban religious beliefs adds another layer of significance to her work. There is a direct connection between Leigh’s practice of ceramics, her engagement with the iconography of the hybrid cowrie and its interiority, and Yoruban religious and philosophical beliefs. In Yoruban religious thought, “the physical head is thought of as no more than a shell, orí òde (lit. ‘outer head’), concealing the orí inú, the ‘inner head.’” (Lawal 1985, p. 91). Lesser divinities, or òrìsà, mold the physical body from divine clay and life is breathed into it through the head. The newly birthed human is then directed to another òrìsà, known as the potter, whose responsibility is to mold the inner head (Lawal 1985, p. 91). Inspired by the metaphysical importance of the head in Yoruba tradition, Leigh’s sculptures reflect notions of interiority and the molding of the self. Through forms reminiscent of Yoruban shrines and houses, Leigh highlights the connection between materials, individual histories, and collective experiences. Cowrie (Pannier) is symmetrical, arguably frontally oriented, and focuses hierarchically on the hybrid cowrie that stands in for a head. Leigh’s focus on the head likely responds to the beliefs of the Yoruba of Western Nigeria, upon which she often draws. The Yoruba traditionally viewed the human head as the most vital part of a person, making it the largest and most elaborately finished part of Yoruba figural sculpture. This significance arises from the fact that the brain, where wisdom and reason reside, and the sensory organs responsible for perceiving the environment are physically present in the head. An even higher importance is placed on the metaphysical significance of the head as the source of life and human personality.

Moreover, Cowrie (Pannier) echoes the form of the ìborí, which is both a shrine and a house. This implies that Cowrie (Pannier), like the hybrid cowrie itself, is concerned with the idea of interiority as it is connected to the self, and with the way in which materials can speak to individual and collective histories. According to Babatunde Lawal, there are three modes of representing the human head in African art: naturalistic, stylized, and abstract. In the abstract mode, the head is represented as an ìborí, a shrine for worshipping the orí (Figure 11). A transportable cone-shaped object wrapped in leather and ornamented with cowries, an ìborí contains a leather bag into which divination powder has been poured. The powder represents the primeval clay with which the person was molded (Lawal 1985, p. 98). Lawal remarks that “its lavish decoration with cowries, the ancient form of Yoruba currency, underlines its function as the source of its owner’s well-being.” (Lawal 1985, p. 98). The ìborí itself is housed in a decorated cowrie container that serves as its house.

Figure 11.

Ibori, Shrine of the Head, 19th or 20th Century. Animal shell, animal skin, metal, textile, 31.3 × 12.7 × 9.5 cm. Courtesy of The Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Cowries, watermelon, and clay—materials that can be charged or contradictory in their meanings—can also be thought of as concentrating a kind of power rooted in the exchange between natural history and human history. Leigh’s deliberate choice of the watermelon, laden with symbolic weight and associated with derogatory portrayals of Black femininity, underscores her intention to reimagine and recontextualize the natural histories of entities that circulated during the transatlantic slave trade. Watermelon and cowries stand in as allegorical representations of the transformative process by which individuals were commodified within the slave economy. Historically, cowries have shifted between living organisms and symbolic currency, mirroring the dehumanizing metamorphosis experienced by enslaved individuals. Leigh’s sculptures challenge fixed identities and economies of exchange, inviting viewers to contemplate entities’ natural history and resist their reduction to mere commodities. The interiority of cowries remains elusive, inviting poetic speculation beyond human understanding. The anatomy of the Cypraea moneta exemplifies this—it is characterized by a dynamic process of slippage, dissolution, and accumulation. Despite the suggestion of access through their slits, the interiority of Leigh’s hybrid cowries ultimately remains closed off, emphasizing the obscurity of others’ experiences. Thus, the hybrid cowrie represents an interiority entangled in materiality and offers a space for positive identity formation, echoing Maria del Guadalupe Davidson’s concept of creative resistance within an interior space of the self. Leigh’s engagement with Yoruban religious beliefs adds another layer of significance to her work. Inspired by the metaphysical importance of the head in Yoruba tradition, her sculptures reflect notions of interiority and the molding of the self. Through forms reminiscent of Yoruban shrines and houses, Leigh highlights the connection between materials, individual histories, and collective experiences. Through the juxtaposition of hybrid animal and plant architectures within and alongside hybrid human architectures, Leigh demonstrates that difference, variation, and metamorphosis exist within and alongside armatures, we might, at first, imagine to be impermeable and immobile.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | (Troy 1977, p. 15). Salt glazing originated in Germany’s Rhineland with the earliest fragment of a piece glazed with salt dated 1539. Thank you to Sandra Ginter, professor of ceramics at Saint Mary’s College, Notre Dame, for her help in deciphering how Leigh’s cowries were made. |

References

- Bennett, Michael, Vanessa D. Dickerson, Daphne Brooks, Dorri Beam, Meredith Goldsmith, Ajuan Mance, Yvette Louis, and Doris Witt. 2001. Recovering the Black Female Body: Self-Representations by African American Women. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois, Louise, and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. 1999. Louise Bourgeois: Memory and Architecture. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía; Madrid: Aldeasa. [Google Scholar]

- Caruth, Nicole J. n.d. Gastro-Vision: Simone Leigh and the Fruits of Her Labor, Art 21. Available online: https://magazine.art21.org/2012/01/20/gastro-vision-simone-leigh-and-the-fruits-of-her-labor/ (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2009. The Climate of History: Four Theses. Critical Inquiry 35: 202–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Kimberly. 2014. Simone Leigh Uses Sculpture, Video to Race, Gender Issues. SF Gate, February 5. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Maria del Guadalupe. 2006. The Rhetoric of Race: Towards a Revolutionary Construction of Black Identity. València: Publicacions de la Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Maria del Guadalupe, Kathryn T. Gines, and Donna Dale L. Marcano. 2010. Convergences: Black Feminism and Continental Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques, and Marie-Louise Mallet. 2008. The Animal That Therefore I Am. Perspectives in Continental Philosophy. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Devin. 2021. The Ecology of Form. Critical Inquiry 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildburgh, Walter Leo. 1942. Cowrie Shells as Amulets in Europe. Folklore 53: 178–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiple, Kenneth F., and Conee Kriemhild Ornelas. 2000. II.C.6. Cucumbers, Melons, and Watermelons. In Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lagasse, Paul. 2018. Cowrie. In The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiji, Nadir. 2006. Adventures with the Theory of the Baroque and French Philosophy. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Lawal, Babatunde. 1985. Orí: The Significance of the Head in Yoruba Sculpture. Journal of Anthropological Research 41: 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, Simone Yvette. 2019. I’ve Seen Some Preliminary Thoughts on the Biennial and Concerns about Radicality. Instagram, May 16. [Google Scholar]

- Léo Neto, Nivaldo A., Robert A. Voeks, Thelma L. P. Dias, and Rômulo R. N. Alves. 2012. Mollusks of Candomblé: Symbolic and Ritualistic Importance. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 8: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, C. K. 1940. 78. The Meaning of the Cowrie-Shell in Nigeria. Man 40: 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Moten, Fred. 2003. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundiran, Akinwumi. 2002. Of Small Things Remembered: Beads, Cowries, and Cultural Translations of the Atlantic Experience in Yorubaland. International Journal of African Historical Studies 35: 427–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Vivian. 2001. Carrie Mae Weems Serves Up Substance. Gastronomica 1: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichek, Elaine. 2008. Spider’s Stratagem. Art in America 96: 118–23. [Google Scholar]

- Respini, Eva. 2022. Simone Leigh: Sovreignty, U.S. Pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale Di Venezia. Boston: ICA. Boston: La Biennale di Venezia. [Google Scholar]

- Stivale, Charles J. 2011. Gilles Deleuze: Key Concepts. Durham: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Troy, Jack. 1977. Salt-Glazed Ceramics. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Michele. 2004. Dark Designs and Visual Culture. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wintjes, Justine. 2020. A Cowrie’s Life: The São Bento and Transoceanic Trade in the Sixteenth Century. Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies 6: 245–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).