Murals and Graffiti in Ruins: What Does the Art from the Aliko Hotel on Naxos Tell Us?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Historical Overview of the Aliko Hotel

3. Methodological Basis of the Study of Murals in the Aliko Hotel in the Context of Barthes’ Theory

3.1. Empirical Material Collection

3.2. Semiotic Analysis in the Context of “Studium” and “Punktum”

- What are the general themes and motifs presented in the murals and graffiti? (studium)

- What elements of these artworks relate to broader social, cultural, or historical contexts? (studium)

- Is there any specific detail that attracts attention or provokes a strong emotional response? (punktum)

- How do personal experiences and beliefs influence interpretation? (punktum)

4. Analysis of Murals and Graffiti in the Space of the Aliko Hotel

4.1. Dialogues of Art

4.2. Mythical Murals

4.3. Murals of Transcendence

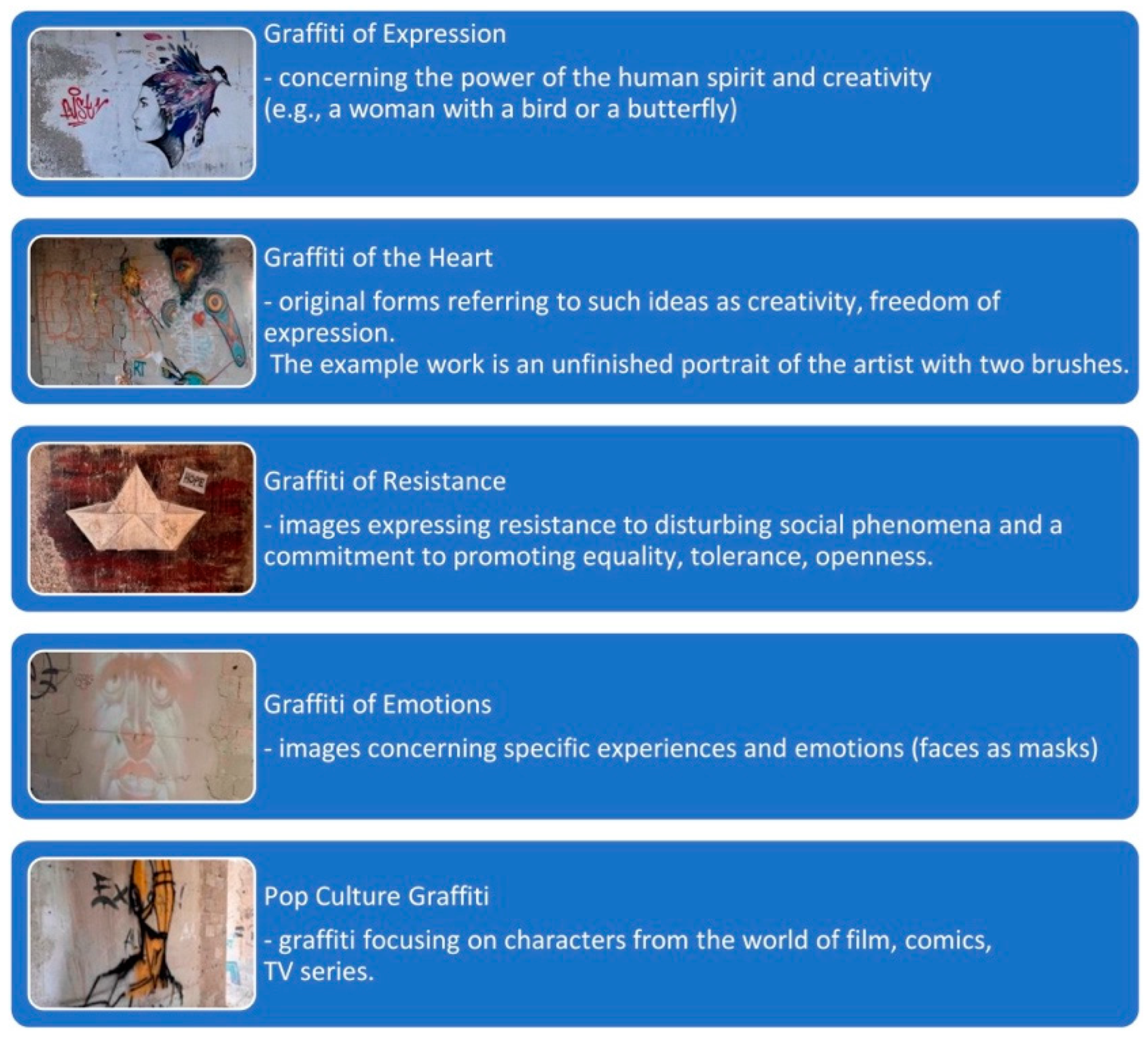

4.4. Graffiti of Expression

4.5. Graffiti of the Heart

4.6. Graffiti of Resistance

4.7. Graffiti of Emotions

4.8. Pop Culture Graffiti

5. Reimagining Spaces—Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Photo of a Mural or Graffiti | Author | Title | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| WD | “The Third eye”, 2018 | The picture shows a mural depicting a colourful, fantastical figure with a large, distinctive head and one visible eye. The figure has a bald head and intense, dramatic facial features, which give it a striking and somewhat surreal character. The colour scheme of the mural is vibrant, with deep shades of purple, red, and various shades of orange that outline the figure and emphasise its three-dimensional form. The figure seems to be intensely looking at the viewer, which can evoke a feeling of interaction or observation. The background of the mural, the dusk sky, and the raw, concrete surroundings create a contrasting backdrop for the colourful image, while at the same time integrating the artwork with its environment. The mural refers to Greek mythology—the motif of the Cyclops. At the same time, the third eye in Hinduism is a symbol of enlightenment and extrasensory perception. The 3D effect emphasises transcending the boundaries of knowledge and entering higher states of consciousness. |

| WD | “Sea Breeze”, 2018 | The photo shows a mural painted on the outer wall of a concrete structure. The mural depicts a colourful image of a woman in profile, with her head turned towards the sky. Her face is detailed with clear features and vibrant colours, including shades of purple, yellow, and orange. Above the woman’s head is a decorative motif that may resemble flames or plant patterns, executed in warm colours, creating an aura or crown around her head. On the right side of the mural, there are also abstract blue shapes that could symbolise water or air, adding an element of nature and movement to the composition. The female figure is entwined with tentacles. This suggests the mythical Medusa, but it could also be a goddess emerging from the sea waves, as suggested by the name ‘sea breeze’. |

| Lud Artwork | “Greek Gods” | The photo shows a mural depicting two male profiles facing in opposite directions, executed in dominant blue and black colours. The style resembles dynamics and movement, which may be accentuated by clear, almost abstract lines and patterns that create the background and fill the space around the figures. The faces are expressive, with strongly marked features and distinctive contours, giving the mural a strong emotional character. The background patterns may resemble elements of wind or water, which, combined with the cool colour scheme, creates a sense of movement and change. The mural might suggest a contrast between two states of being, different perspectives, or reflect the internal dynamics of thoughts and emotions. The choice of location is not coincidental, as the island of Naxos is the mythical birthplace of the Olympian God |

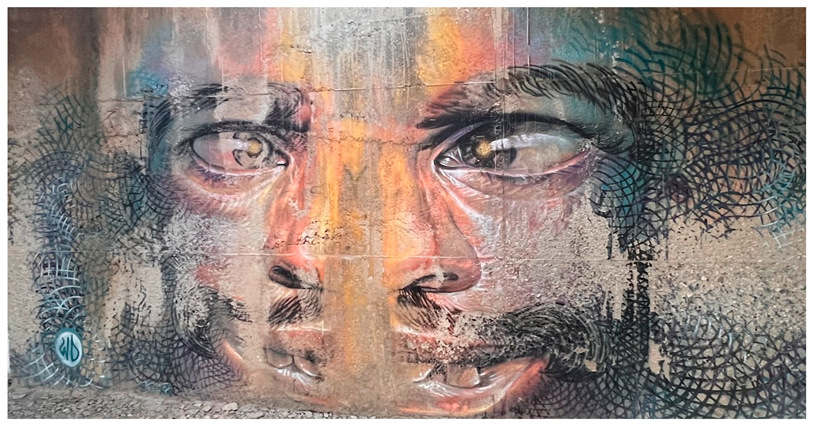

| WD | “Madness”, 2018 | The photo shows a mural depicting a close-up of a man’s face. The mural is made with a great amount of detail. The clear facial features, such as eyes, nose, and mouth, are visible. The colour scheme of the artwork is rich, combining warm shades of brown, orange, and yellow, which give the character expressiveness and depth. A distinctive feature of this mural is the texture resembling fingerprints or small spirals, creating a complex pattern over the entire surface of the image. These details give the entire work a unique character and may suggest the idea of identity, individuality, or the complex nature of human existence. The mural is not only visually striking but can also be interpreted as a deep artistic statement, representing an allegory of madness, as expressed by the man’s erroneous gaze. Additionally, it creates an effect of optical illusion. |

| WD | “Elf”, 2018 | The photo shows a mural on the concrete wall of a building, placed in a natural setting. The mural depicts a colourful portrait of a smiling young elf with a playful gaze. The girl’s face is full of life, with rosy cheeks and a cheerful expression in her eyes, giving the mural a warm and positive character. The figure refers to Norse beliefs, in which elves were beautiful beings endowed with power. Some of them harmed humans (dark elves), while others helped. The artwork is positioned in such a way that it forms the central point of view through an opening in the wall, adding depth to it and making it clearly visible in the landscape. The background of the wall is a view of the sea and sky, which highlights the contrast between the artificial structure and the natural environment. The overall composition harmonises with the surroundings while attracting attention with its intense colour scheme and touching representation of youth. |

| WD | “Beaching”, 2018 | The photo shows a mural on an external wall, depicting two bird heads looking in opposite directions. The birds are painted in a realistic style, with rich details and vivid colours, giving them a sense of dynamism and vitality. Their feathers display various shades of green, blue, and brown, and their eyes seem expressive and full of life. The mural uses the perspective of the wall to create the illusion that the birds are part of a larger scene that extends beyond the boundaries of the image. The title ‘Beaching’ suggests relaxation and a stopover on a long journey. The mural in the photo showcases a nature motif in the form of migrating. |

| WD | “No place like home”, 2015 | The photo shows a mural inside a concrete structure. The mural consists of several realistic paintings depicting animal figures that seem to blend into the concrete walls and pillars of the structure. On the left side, the mural features the face of a gorilla, which appears to emerge from dense shadows or is partially masked by patterns resembling fingerprints. Deeper in the room, on another wall, the face of a bear is visible, adding a wild and mysterious element to the overall composition. All figures are rendered in a monochromatic colour palette, which, combined with natural light entering through openings in the walls, creates a play of light and shadow, adding depth and atmosphere to the entire scene. This mural can be interpreted as an artistic statement about the presence of animals in abandoned or forgotten spaces. The mural has been partially destroyed, but in its original version, one of the figures is holding a club. |

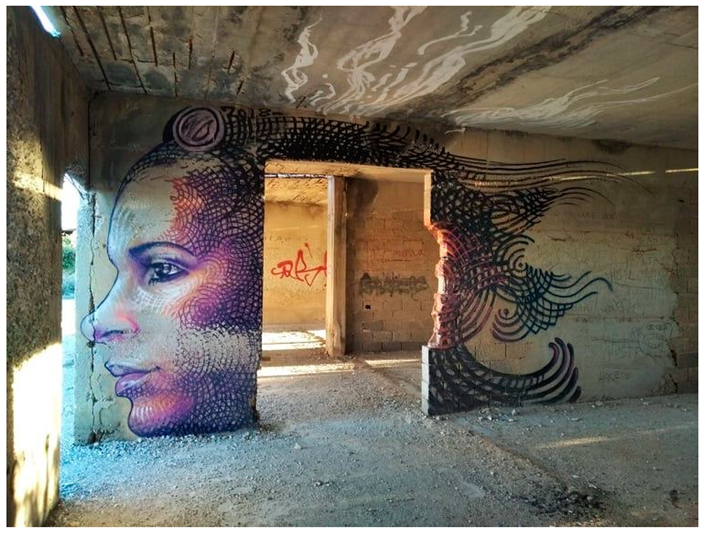

| WD | “Expectancy”, 2018 | The photo shows a mural painted on a concrete wall in a space resembling an unfinished or abandoned building. The mural depicts a realistic profile of a woman’s face looking to the right. The artwork is detailed, with clear facial features and smooth colour gradients. The woman’s face is surrounded by abstract patterns that seem to spread from her head and intertwine with the surrounding architecture, creating the impression that these patterns are an extension of the character’s thoughts or emotions. These patterns are made in dark shades, creating a striking contrast with the lighter parts of the face. The mural has a modern and dynamic character, thanks to the use of various painting techniques and the effect of expanding forms. The entrance door is located in the head’s position, creating the illusion that we can see inside the character’s thoughts. |

| Skitsofrenis | No title painted 2019 | Na zdjęciu widoczne jest graffiti, które przedstawia profil kobiety z uderzającymi, kolorowymi piórami w miejscu, gdzie zwykle znajdują się włosy. Pióra mają różnorodne barwy, takie jak róż, niebieski, żółty i czerwony, i sprawiają wrażenie, jakby były rozłożone jak w pawim ogonie lub były częścią maski karnawałowej. Twarz kobiety jest wykonana w subtelnych odcieniach szarości i białego, co tworzy wyraźny kontrast z żywymi barwami piór. Wyraz twarzy kobiety jest spokojny i zamyślony, a jej spojrzenie skierowane jest ku górze. Obok głowy kobiety unoszą się luźno abstrakcyjne kształty, które mogą przypominać płatki lub dodatkowe pióra, co dodaje całej kompozycji lekkości i eteryczności. Całość dzieła ma artystyczny i poetycki charakter. Ptak we włosach jest symbolem wolności, ekspresji i kreacji (kolorowe skrzydła)1 |

| Skitsofrenis | “Bang, bang I thought you down”, 2019 | The photo shows graffiti depicting the profile of a woman with striking, colourful feathers in place of where hair usually is. The feathers have various colours, such as pink, blue, yellow, and red, and they give the impression of being spread out like a peacock’s tail or being part of a carnival mask. The woman’s face is executed in subtle shades of grey and white, creating a clear contrast with the vibrant colours of the feathers. The woman’s expression is calm and thoughtful, with her gaze directed upwards. Floating loosely next to the woman’s head are abstract shapes that could resemble petals or additional feathers, adding lightness and ethereality to the entire composition. The whole work has an artistic and poetic character. The bird in her hair symbolises freedom, expression, and creation (colourful wings). |

| Skitsofrenis | “Killing time with spray paint” | The photo features the face of a woman with butterfly wings. The butterfly symbolises transience, the fragility of life, and beauty but also transformation. The woman has a calm, thoughtful expression, and her contour is clear and elegant. On the right side of the wall, there are also other tags and graffiti that appear to be less complex and may come from different artists. The dominant colours are blue and red, which integrate the mural with its surroundings, adding visual interest and an accent. The wall is in a brightly coloured environment, probably in a coastal area or open countryside, which allows the mural to stand out in this space |

| Anonymous | No title | The photo shows graffiti on a brick wall. The graffiti depicts a figure with lush, flowing red hair that surrounds her face, creating a kind of halo. The figure has closed eyes and hands folded near the heart, and her gesture may suggest meditation, prayer, or deep concentration. Above the figure’s head is a mask or totem with distinctive eyes and ornaments, giving the composition a mystical or ritualistic character. On the wall next to the figure, there are two messages. On the left side, the inscription reads: ‘Seal the urban at its mouth. Take the water prisoner.’, which can be interpreted as a call to control natural resources or to protect the environment. On the right side, the inscription states: ‘Fill the sky with screams & cries. Bathe in fiery answers.’, which may refer to emotional expression, rebellion, the search for truth, or the need for change. The entire graffiti, along with the texts, may have a deep symbolic meaning, encouraging reflection on human actions towards nature and society. The style of the work is colourful and expressive, with a strong emphasis on words and their potential consequences. |

| RT | No title | The photo shows graffiti depicting a colourful figure of a man with distinctive, ethereal features. The man has curly hair and a beard, and his face is turned towards a flower (star) that he is holding in his hand. Around the figure, there are abstract, colourful patterns, including a heart on the chest and spirals on the arms, which give the entire image a surrealistic mood. On the left side of the graffiti, there is another inscription, likely a tag from a different artist, which contrasts with the more polished and colourful work. Colourful streams directed towards the figure’s hand may symbolise energy, life, or creativity. The figure seems to breathe nature and harmony, suggesting a positive message of this piece of street art |

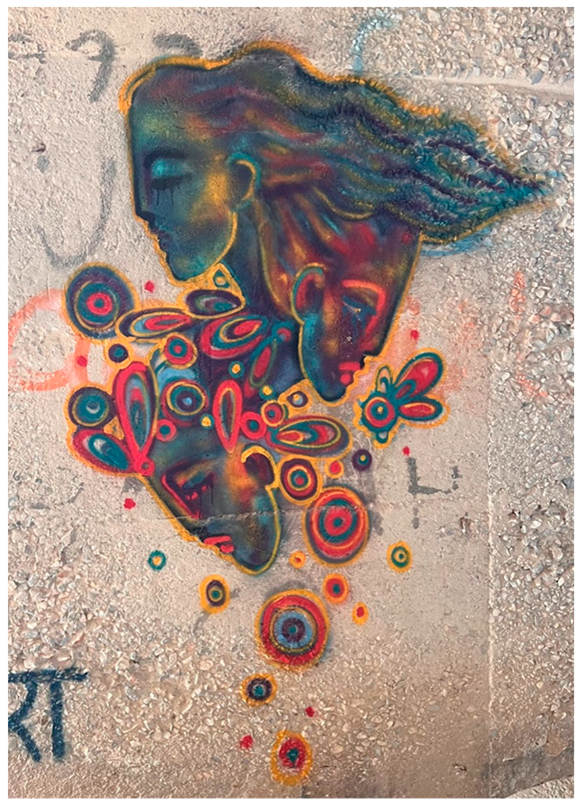

| RT | No title | The photo shows a section of colourful graffiti, depicting the profile of the head and upper body of a figure with refined, organic forms around it. The figure has a thoughtful, serene facial expression and seems to be in a state of reflection or meditation. The figure’s hair is represented as flowing lines in shades of red and blue, adding dynamics and a sense of movement. Around the figure, there are abstract shapes and patterns resembling flowers, circles, and other botanical motifs, executed in a warm colour palette, predominantly red, blue, and yellow. These decorative elements appear to radiate from the central figure, which might suggest the emanation of energy or an aura. |

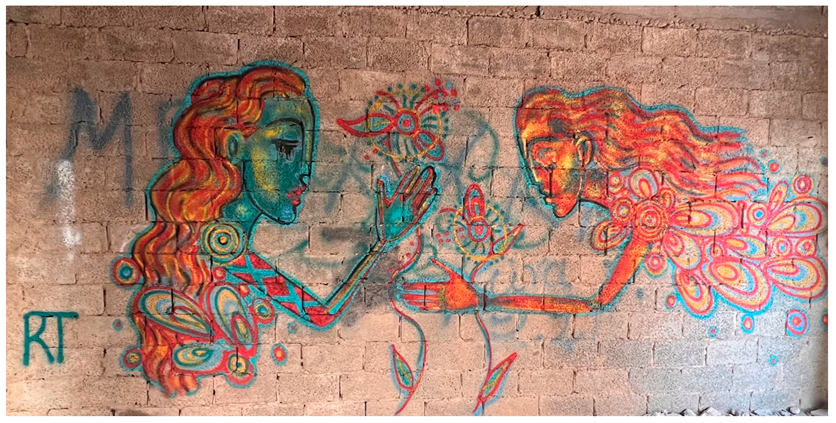

| RT | No title | The photo shows colourful graffiti on a brick wall. It depicts two figures in profile, facing each other, in a position suggesting interaction or dancing together. Each figure has elongated, decorated facial lines, with clearly defined eyes, noses, and mouths. The work is characterised by a dynamic colour palette, with dominating shades of blue, red, and turquoise, and patterned ornaments surrounding the figures, which may suggest movement or energy emanating from the dancers. The graffiti is executed in a style that combines elements of surrealism with ethereal motifs, possibly reminiscent of botanical or organic patterns. The whole is full of life and movement, and the colourful execution makes the work stand out against the brick wall background |

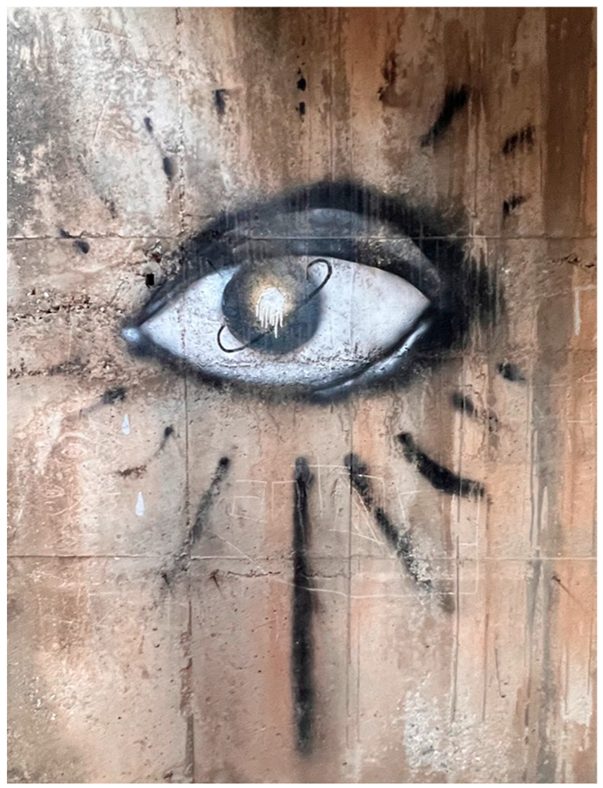

| Anonymous | No title | The photo shows graffiti depicting an eye. The work is mainly in shades of grey and black on a concrete background, giving it a monochromatic and stark character. The eye mimics a planet with a ring—Saturn (a reference to the cosmic universe, where the microcosm reflects the macrocosm). In ancient Egypt, the Eye of Horus was a symbol of rebirth and a protective sign. The eyes of Horus were the sun and the moon. |

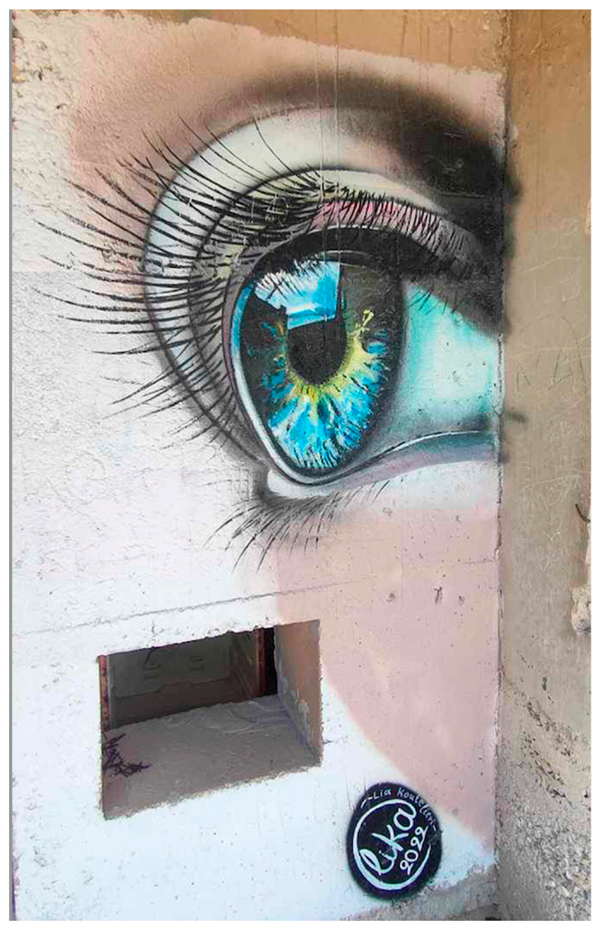

| Lia Koutelieri | No title | The photo features a detailed graffiti painting of an eye on a concrete wall. The eye has realistically rendered details such as an iris in shades of blue and yellow, shiny reflections that add depth, and distinct lashes radiating outwards. This graffiti is particularly impressive due to its realistic details and three-dimensional effect. Below the eye, there is a rectangular opening in the wall, adding a certain level of abstraction to the composition and possibly suggesting that the eye is ‘peeking’ into the wall’s interior. Next to the eye, there is also a small, round sticker or painting with an illegible tag, which might be the artist’s signature. The entire piece demonstrates a high level of skill and is an example of how street art can attract attention and evoke emotional responses. |

| Anonymous | No title | The photo shows graffiti on a concrete wall, depicting the silhouette of a human with a body resembling that of a horse, giving the figure a centaur-like appearance. The figure is holding a stick or staff, and its posture seems to express movement or dance. The figure also features a symbol with a crossed-out circle, which could be the artist’s mark or a symbol representing a certain message or ideology. The background of the graffiti includes additional tags and symbols applied by other creators, which is typical for places popular among street artists. The style of the artwork is simplified, with a strong outline that clearly separates the figure from the background. The whole creates a contrast between the ancient myth of centaurs and contemporary graffiti culture |

| Andrea Nyffeler | Hope | The photo shows graffiti depicting a white, origami sailboat against a red-and-black mural. The boat is the central element of the piece, with clear lines and edges that make it appear three-dimensional. Next to the boat, a small label with the word ‘HOPE’ is placed, which may suggest the symbolic meaning of the image. The background is irregular and seems to be made of smeared and dripping paints in dark shades, which might evoke the idea of seawater or a stormy sky, adding depth and emotional context to the entire composition. |

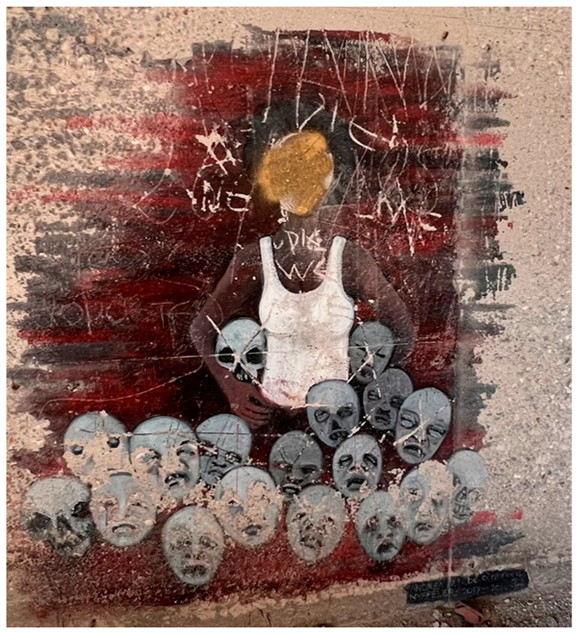

| Andrea Nyffeler | No title | The photo features a dark-skinned woman without a face, standing amidst masks symbolising death. She appears to be wearing something like a white shirt, with her arms hanging down along her body. The graffiti addresses the issue of fighting inequalities. Originally, the woman’s face was not blurred, showing that subsequent individuals entered a dialogue with the message, giving it new meaning. The background of the work is dominated by dark, red, and black colours, adding a dramatic tone to the composition. The whole can evoke a sense of unease and may be an attempt to express difficult themes such as suffering, the human condition, or social criticism. The wall on which the image is located appears to be in poor condition, which may reinforce the artistic message of transience and oblivion. |

| Anonymous | Horses in gallop | The photo shows a mural depicting two horses in motion, painted on a wall. The horses are represented in dynamic poses, suggesting running or galloping. The work is primarily in shades of blue on a white background, giving it a cool and tranquil character. In the lower part of the mural, there is a decorative band with motifs resembling waves or clouds, which may suggest a meadow or water surface over which the horses are running. The style of the painting is relatively realistic, with attention to the anatomical details of the animals. The graffiti is well integrated with its surroundings, and its horizontal format fits the long shape of the wall. It seems to be designed to decorate urban space, bringing an element of nature into the urban environment. |

| Anonymous | Save the Animals | The photo features colourful graffiti on a concrete wall background. The graffiti depicts an unusual figure that seems to be a hybrid between a cat and an owl, with large, expressive eyes and fluffy fur. The figure is holding a fish, which may suggest a fishing scene or a symbolic connection with nature. The graffiti is executed in shades of blue and white, with accents of black, giving it a dreamy and ethereal character. Around the main figure, there are various inscriptions, including ‘SAVE THE ANIMALS’, as well as other, less legible tags and symbols, such as a heart, which may indicate an ecological or pro-animal message. Works of this type often aim to raise social awareness or simply adorn urban spaces. The background wall is covered with other graffiti and tags, indicating that this place is popular among street artists |

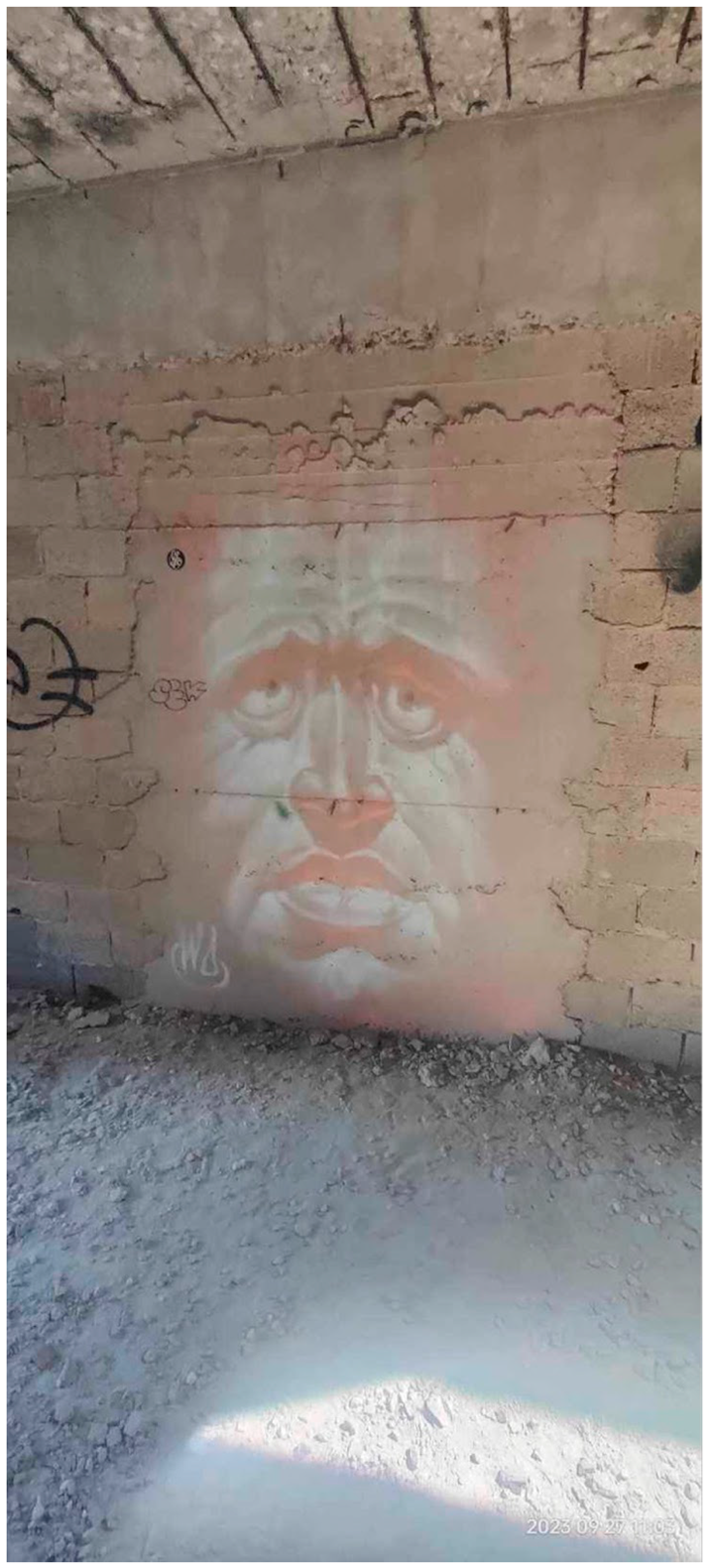

| Anonymous | No title | The photo features a man’s face with an expression of surprise or astonishment. The man has bulging eyes and raised eyebrows, which may suggest emotions of surprise or amazement. The graffiti is painted in light shades, with dominating whites and beiges, and delicate contours. In the background, a somewhat neglected wall is visible, with cracks and traces of peeling paint, which gives the whole an urban character. Next to the graffiti, there are other smaller paintings and tags. |

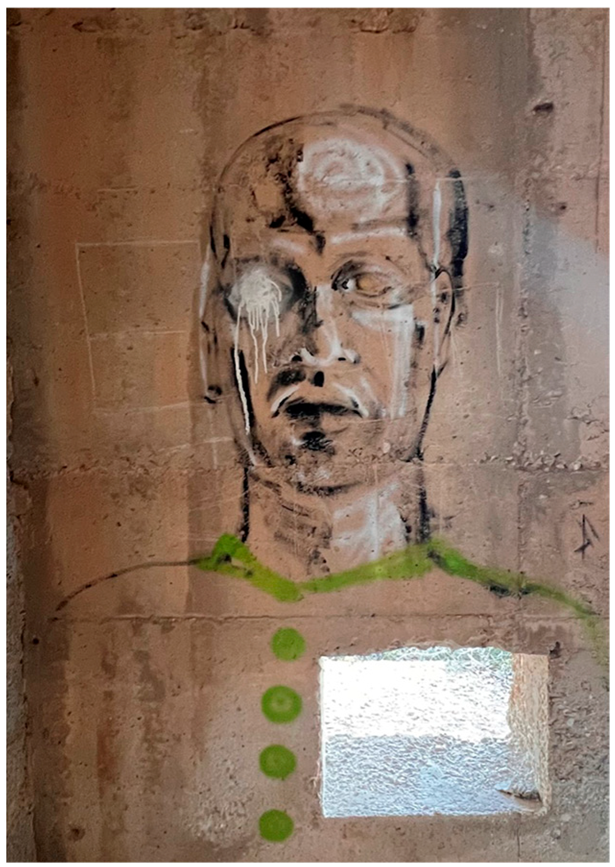

| Anonymous | No title | The photo features a figure of a man with the outline of his head and neck. It is created in a monochromatic colour palette, mainly in shades of grey, with visible traces of green paint at the bottom of the work. The face is characterised by harsh lines, with clearly defined facial features, giving an impression of three-dimensionality. The graffiti lacks an eye (it is painted over), which gives the composition a mysterious and somewhat unsettling mood. In the lower part, there is a rectangular area that reflects light, creating the impression of a mirror or window. The wall appears to be in poor condition, which emphasises the somewhat abandoned character of the place where the graffiti is located. |

| Anonymous | No title | The photo shows a section of a brick wall on which graffiti in the form of a simplified human face has been created. The graffiti consists of several colourful elements: one eye is outlined in red with a black contour, the other eye is less distinct, and the mouth is highlighted with bright green paint. The lines are simple and somewhat asymmetrical, giving the face an abstract and sketchy expression. The background is neutral and grey, which makes the colourful elements of the graffiti stand out, giving the work a distinctive accent. The appearance of the face is exaggerated, which may suggest a certain kind of artistic expression or commentary. The whole gives the impression of an informal, spontaneous piece of street art. |

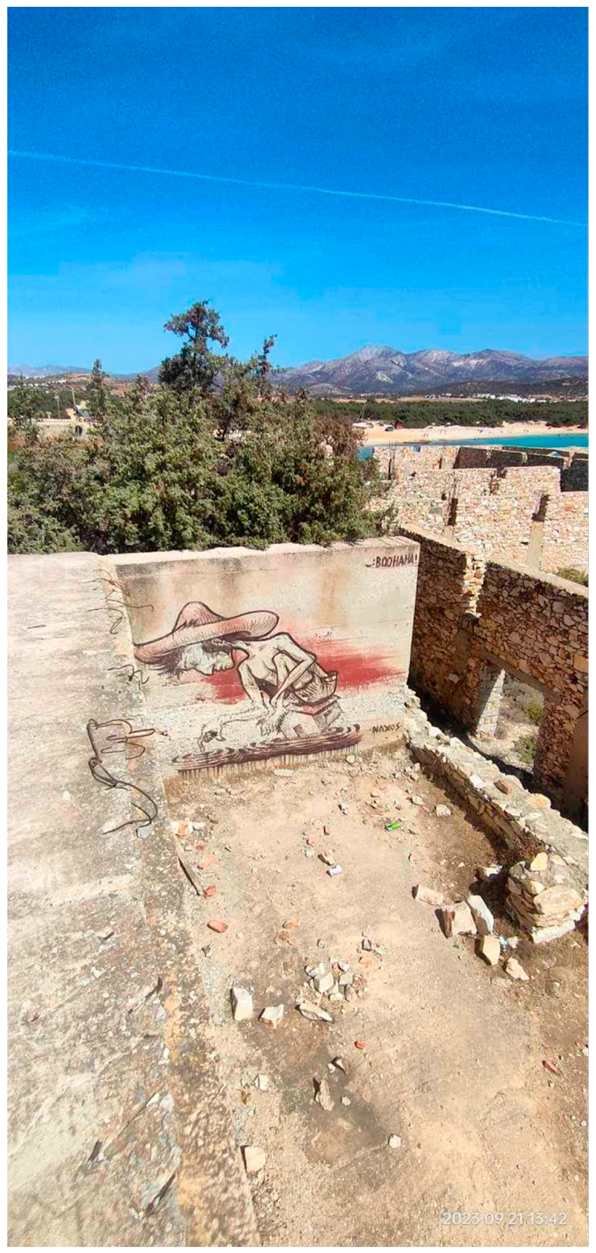

| Anonymous | No title | The photo shows a piece of wall or stone on which graffiti has been painted. It depicts a caricature of a character in a sombrero who appears to be playing a guitar, sitting on an unseen bench or similar object. The figure has exaggerated features, such as long, thin limbs and an elongated torso, giving it a humorous and overstated character. The background of the graffiti is in shades of red and brown, which may suggest a sunset or a desert environment. Above the figure is the text ‘BOOHAWHA!’, which can be interpreted as a laugh or exclamation, adding a comedic element to the scene. In the lower right corner, there is a signature ‘NAXOS’, which may indicate the artist or location of the graffiti. The overall style resembles comic drawings or illustrations from humorous books |

| Anonymous | No title | The photo shows graffiti on a concrete wall. The graffiti depicts a figure with a large, round head that might resemble a helmet or mask. The figure has an outlined body with elongated, slender arms. Above the figure’s head is a symbol or inscription that looks like ‘Ex’ with additional graphic elements, suggesting a possible meaning or context associated with this work. Below the figure, there is another inscription, which might be the artist’s signature or a comment. The colour scheme of the graffiti is mainly black and yellow, creating a strong contrast against the grey wall. The style of the painting is simple, with clear lines and a dynamic posture of the figure. |

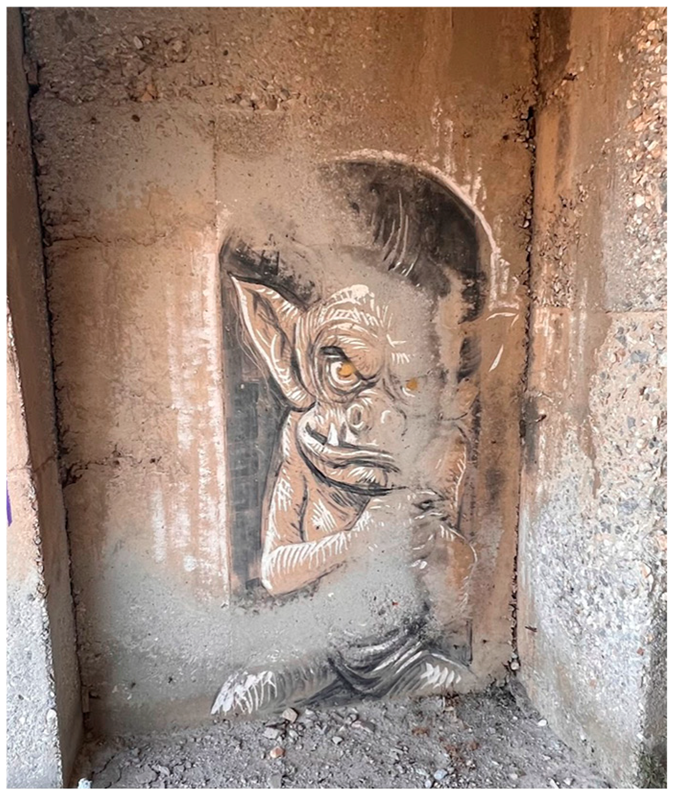

| Anonymous | No title | The photo shows graffiti depicting a figure resembling a goblin or another fantastical, mythological creature. The image is created in a monochromatic colour palette, mainly in shades of grey. The figure has distinctive, large eyes, pointed ears, and a twisted nose, giving it a grotesque, perhaps even slightly terrifying appearance. The creature is holding something resembling a pipe or club, and its pose suggests dynamic movement or hiding. The graffiti is placed in a niche or opening in the wall, which adds depth to the composition and makes the figure appear to be emerging from the shadows. Details such as the folds of the skin or the texture of the clothing are carefully executed, demonstrating the artist’s high skill. The overall piece has a surrealistic character and can evoke various interpretations depending on the viewer. |

| Anonymous | No title | The graffiti is varied in style and colour, with some pieces displaying more artistic flair, using gradients and shading to create a sense of depth. Other tags are simpler, featuring names or initials in a typical tagging style. The lighting plays a significant role in the mood of this scene, creating a play of shadows that could be seen to symbolise the interplay between light and dark, perhaps metaphorically representing hope in neglect or beauty in decay. The overall atmosphere of the image is one of forgotten urbanity, a space where the usual bustle of city life has been replaced by a quieter, more reflective presence. |

| 1 | The photograph captures a piece of graffiti that depicts a woman’s profile, her head adorned with striking, colorful feathers in place of where one would typically find hair. These feathers boast a spectrum of hues such as pink, blue, yellow, and red, creating an impression as if they were splayed out like a peacock’s tail or part of a carnival mask. The woman’s face is rendered in subtle shades of gray and white, establishing a vivid contrast with the vibrant colors of the feathers. Her expression is serene and contemplative, with her gaze directed upwards. Floating near the woman’s head are loose, abstract shapes that might resemble petals or additional feathers, lending an overall lightness and ethereal quality to the composition. The entire piece exudes an artistic and poetic essence. The bird in her hair symbolizes freedom, expression, and creation (colorful wings). |

References

- Ayan, Ayse. 2021. Street art as a form of translation in the urban space. Çeviribilim Ve Uygulamaları Dergisi, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, Roland. 1980. La Chambre Clare. Note sur la Ohotographie. Paris: Seuil Éditions Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 2020. Swiatło Obrazu. Uwagi o Fotografii. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Aletheis. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Binet, Andrew, Vedette Gavin, Leigh Carroll, and Mariana Arcaya. 2019. Designing and facilitating collaborative research design and data analysis workshops: Lessons learned in the healthy neighbourhoods study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrington, Victoria. 2009. I write, therefore I am texts in the city. Visual Communication 8: 409–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee, Lyman G. 1993. Political Protest and Street Art. Popular Tools for Democratization in Hispanic Countries. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, Rebecca, Caitlin Mullin, Daniel Berio, Frederic Fol Leymarie, and John Wagemans. 2020. Aesthetics of Graffiti: Comparison to Text-Based and Pictorial Artforms. Empirical Studies of the Arts 40: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clogg, Richard. 2002. A Concise History of Greece (Cambridge Concise Histories). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shewy, Mohamed. 2020. The spatial politics of street art in post-revolution Egypt. Journal of Urban Cultural Studies 7: 263–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartus, Andreas, and Leder Helmut. 2014. The white cube of the museum versus the gray cube of the street: The role of context in aesthetic evaluations. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 8: 311–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakouvakis, Giorgios, MDE Konstantina, and Konstantinou Maria. 2020. Report: Street Art Naxos—An Overview of the Works in the “Ruined Hotel of Naxos”. Available online: https://www.crimetimes.gr/report-street-art-naxos-mia-episkopisi-twn-ergwn-sto-ere/ (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, Monica, Lucia Schiatti, and Maria Bianca Amadeo. 2021. Masking emotions: Face masks impair how we read emotions. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 669432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralińska-Toborek, Agnieszka. 2019. Graffiti i Sztuka Uliczna. Słowo, Obraz, Działanie. Polska: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. Available online: https://wydawnictwo.uni.lodz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Gralinska-Toborek_Graffiti-20.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Halsey, Mark, and Alison Young. 2002. The meanings of graffiti and municipal administration. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 35: 165–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impelluso, Łucja. 2006. Natura i jej symbole: Rośliny i Zwierzęta. In Leksykon: Historia, Sztuka, Ikonografia. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo “Arkady”. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, Martina. 2012. The Work on the Street: Street Art and Visual Culture. In The Handbook of Visual Culture. Edited by Barry Sandywell and Ian Heywood. London: Berg/Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 234–78. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/8750584/_The_Work_on_the_Street_Street_Art_and_Visual_Culture_in_The_Handbook_of_Visual_Culture_ed_Barry_Sandywell_and_Ian_Heywood_London_Berg_Palgrave_Macmillan_2012_234_278_Pre_press_version_ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Iveson, Kurt. 2007. Publics and the City. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 2–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazeri, Mohamad, and Susanto. 2020. Semiotics of roland barthes in symbols systems of javanese wedding ceremony. International Linguistics Research 3: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, Payal S., M. S. Balaji, and Yangyang Jiang. 2021. Effectiveness of sustainability communication on social media: Role of message appeal and message source. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 33: 949–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanowski, Mariusz. 2018. Mur(al)owe podwoje do przeszłości-Murale jako nośniki kultury historycznej na przykładzie wybranych prac w południowo-wschodniej Polsce. Zeszyty Naukowe Towarzystwa Doktorantów UJ Nauki Społeczne 23: 203–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lachowska, Karolina, and Marcin Pielużek. 2021. Sztuka uliczna jako źeródło wiedzy na temat współczesnych społeczenstw. Propozycja i weryfikacja metody badawczej. Media Biznes Kultura 1: 21–49. Available online: https://czasopisma.bg.ug.edu.pl/index.php/MBK/article/view/6170/5414 (accessed on 12 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Landry, Deborah. 2019. ‘Stop calling it graffiti’: The visual rhetoric of contamination, consumption and colonization. Current Sociology 67: 686–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, Emma Louise. 2024. State Murals, Protest Murals, Conflict Murals: Evolving Politics of Public ArtinUkraine. Arts 13: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, John. 2014. Assembling a revolution: Graffiti, cairo and the arab spring. Cultural Studies Review 20: 237–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Alexis M. 2019. The co-optation of dissent in hybrid states: Post-soviet graffiti in moscow. Comparative Political Studies 54: 1757–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianos, Dymitris. 2023a. Report: Definitive End to the Ruins in Althkos, Naxos, in “Koini gnomi.gr—Cyclades Daily Newspaper”. (Δημήτρης Λιανός (2023), Oριστικό τέλος στα ερείπια στο Aλθκο της Νάξου στο «Κοινή γνώμη.gr—ημερήσια εφημερίδα τον Κυκλάδων). Available online: https://www.koinignomi.gr/news/politiki/politiki-kyklades/2023/01/23/oristiko-telos-sta-ereipia-sto-alyko-tis-naxoy.html (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Lianos, Dymitris. 2023b. The Ruins in Alikos Naxos Are Being Demolished—The Message of D. Lianos. Friday, January 20. (Κατεδαφίζονται τα ερείπια στο Aλυκό Νάξου—Το μήνυμα του Δ. Λιανού, 20 Ιανουαρίου). Available online: https://www.koinignomi.gr/news/politiki/2023/01/20/katedafizontai-ta-ereipia-sto-alyko-naxoy-minyma-toy-d-lianoy.html (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- MacDowall, Lachlan. 2019. Instafame: Graffiti and Street Art in the Instagram Era. Chicago: Intellect Books and the University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://www.graffitistudies.info/publications (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- MacGill, Belinda. 2016. Public Pedagogy at the Geelong Powerhouse: Intercultural Understandings through Street Art within the Contact Zon. Journal of Public Pedagogies, 1–4. Available online: https://jbsge.vu.edu.au/index.php/jpp/article/view/989/1377 (accessed on 21 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Majerczyk, Maria. 2004. Kobieta-ptak-dusza- w archaicznym obrazie świata. Rozprawy i analizy. Etnolingwistyka 16: 287–303. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe, Cameron. 2012. Graffiti or street art? negotiating the moral geographies of the creative city. Journal of Urban Affairs 34: 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Chandra. 2018. Public art replacement on the Mapocho River: Erasure, renewal, and a conflict of cultural value in Santiago de Chile. Space and Culture 23: 149–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubi Brighenti, Andrea. 2010. At the wall: Graffiti writers, urban territoriality, and the public domain. Space and Culture 13: 315–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J. Farley, and Sydney P. Wheeler. 2020. The visual perception of emotion from masks. PLoS ONE 15: e0227951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olteanu, Alin, and Cary Campbell. 2018. A short introduction to edusemiotics. Chinese Semiotic Studies 14: 245–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondřej, Škrabal, Mascia Leah, Ann Lauren Osthof, and Ratzke Malena. 2023. Graffiti Scratched, Scrawled Sprayed. Towards a Cross-Cultural Understanding of Graffiti: Terminology, Contxt, Semiotics, Documentation. In Graffiti Scratched, Scrawled, Sprayed. Studies in Manuscript Cultures. Berlin: De Gruyter, vol. 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospishcheva-Pavlyshyn, Maria. 2021. Changes in the themes, aesthetics and functions of public images in Kyiv due to the influence of socio-cultural processes in the society of 1990–2010. Contemporary Art 17: 183–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottalagano, Flavia V. 2022. Naturalistic parrots, stylized birds of prey: Visual symbolism of the human–animal relationship in pre-hispanic ceramic art of the paraná river lowlands, South America. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 33: 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzycka-Borowska, Elżbieta, Marta Gliniecka, Kalina Kukiełko, and Michał Parchimowicz. 2023. Socio-Educational Impact of Ukraine War Murals. Arts 12: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolston, Bill. 2018. Women on the Walls: Representations of Women in Political Murals in Northern Ireland. Crime, Media Culture: An International Journal 14: 365–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Gregory J. 2009. Graffiti Lives: Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stampoulidis, Georgios. 2019. Stories of resistance in Greek street art: A cognitive-semiotic approach. Public Journal of Semiotics 8: 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampoulidis, Georgios, and Marianna Bolognesi. 2019. Bringing metaphors back to the streets: A corpus-based study for the identification and interpretation of rhetorical figures in street art. Visual Communication 22: 243–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubielska, Magdalena, and Robbie Ho. 2021. Greater art classification does not necessarily predict better liking: Evidence from graffiti and other visual arts. PsyCh Journal 11: 656–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śliwerski, Bogusław. 2021. Pedagogy around graffiti. Studia Z Teorii Wychowania XII: 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldner, Lisa K., and Betty A. Dobratz. 2013. Graffiti as a form of contentious political participation. Sociology Compass 7: 377–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yichuan, Minhao Zhang, Ying Kei Tse, and Hing Kai Chan. 2020. Unpacking the impact of social media analytics on customer satisfaction: Do external stakeholder characteristics matter? International Journal of Operations & Production Management 40: 647–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, Paul J., Scott L. Rauch, Nancy L. Etcoff, Sean C. McInerney, Michael B. Lee, and Michael A. Jenike. 1998. Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. The Journal of Neuroscience 18: 411–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Alison. 2014. Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perzycka-Borowska, E.; Gliniecka, M.; Hrycak-Krzyżanowska, D.; Szajner, A. Murals and Graffiti in Ruins: What Does the Art from the Aliko Hotel on Naxos Tell Us? Arts 2024, 13, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020051

Perzycka-Borowska E, Gliniecka M, Hrycak-Krzyżanowska D, Szajner A. Murals and Graffiti in Ruins: What Does the Art from the Aliko Hotel on Naxos Tell Us? Arts. 2024; 13(2):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020051

Chicago/Turabian StylePerzycka-Borowska, Elzbieta, Marta Gliniecka, Dorota Hrycak-Krzyżanowska, and Agnieszka Szajner. 2024. "Murals and Graffiti in Ruins: What Does the Art from the Aliko Hotel on Naxos Tell Us?" Arts 13, no. 2: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020051

APA StylePerzycka-Borowska, E., Gliniecka, M., Hrycak-Krzyżanowska, D., & Szajner, A. (2024). Murals and Graffiti in Ruins: What Does the Art from the Aliko Hotel on Naxos Tell Us? Arts, 13(2), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020051