Abstract

In this article, I analyze Julia Pirotte’s photographs of the immediate aftermath of the Kielce pogrom as a resource for conceptualizing the relationship between trauma and photography, gendered ways of seeing, memory and trauma, body and archive, vision and death, death and the archive, images and history, survival, and destruction. These specific atrocity pictures make a difference to contemporary conceptions of trauma photography and the female gaze in relation to racist, political violence. I work with theories that go beyond thinking about trauma and photography based on the Lacanian concept of tuché on the one hand, and Barthes’ punctum on the other. I investigate to what extent Pirotte’s documentation of the Jewish victims and survivors of the pogrom can be read as a belated encounter with the trauma of the Holocaust, and what it reveals about survival at the site of violence. The article is a work of a feminist academic oriented at reclaiming a space within the narrative on visual violence; the reflection on the female traumatic gaze is an element of a broader gesture aimed at reorienting the theory of atrocity pictures and documentations of political violence, as well as photography of trauma.

Keywords:

Julia Pirotte; photography; Kielce pogrom; trauma; atrocity pictures; female gaze; psychoanalysis; women Learning to see means learning to read what is not visible, what remains unknown and unperceived, what can emerge only by reading creatively and historically at the same time.Eduardo Cadava

Sometimes, between the time of the pain and when the bruise presents itself, we forget the injury. I am trying to not forget. (…) A bruise is an injury that is “neither inside, nor outside”.Carol Mavor

1. Introduction

Julia Pirotte’s photographs of the immediate aftermath of the Kielce pogrom of 1946 provide a powerful resource for conceptualizing the relationship between trauma and photography. Moreover, they serve to help articulate the relations between memory and trauma, the gendering of the look, body and archive, vision and death, death and the archive, images and history, survival, and destruction. As overwhelming as this list may seem, I hope to show how these images address these relations at present, when so much has been written and said about the traumatic potential of atrocity pictures and their uses and abuses (Didi-Huberman 2008). This does not mean instrumentalizing the images for more a general, theoretical goal; rather, I would like to claim that these images (as well as the broader context of their production and archiving), more than others, allow us to reorient the theory of atrocity pictures. I am convinced that Pirotte’s photographs make a difference to our concept of trauma photography and the female gaze in relation to racist or ethnic political violence1. In my exploration of these photographs, I engage with texts and reflections that exceed conventional thinking about trauma and photography, much of which is based on the Lacanian concept of tuché on the one hand, and Barthes’ punctum on the other (Baer 2002; Batchen 2009; Koszowy 2018). I am searching for another model of looking at such photographs that “unlearns” the abovementioned conventions and originates from the needs for connections and relations, empathy rather than knowledge. I am specifically inspired by the work of Eduardo Cadava, Ariella Azoulay, and Carol Mavor, insofar as their texts are conceived in affective proximity, or even inseparable from the production of remarkable photographers, such as Susan Meiselas, Julia Pirotte, and Lee Miller (Cadava 2021; Azoulay 2008, 2012a; Mavor 2012).

I am thus concerned to formulate a theory of the female traumatic gaze based predominantly on the reading of the photographs deposited in the archive of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. These document the days after the Kielce pogrom occurred on 4 July 1946, depicting the dead and battered bodies of its victims and scenes at the morgue, in the hospital, and at the funeral. Many of these images are attributed to Julia Pirotte, a Polish–Jewish photographer and photojournalist, internationally recognized for her documentation of the 1944 liberation of Marseille. According to her testimony, she was the only person on site taking pictures in Kielce. I discuss the consequences of a certain archival opacity within the photographic event and the atrocity image, as well as the effects of the photographer’s subject position: the correspondence between the photographer and the witness as well as that between the one who sees and is being seen at the same time. Lastly, I explore the following conundrum: Pirotte was commissioned by the editor in chief of the journal Żołnierz Polski (Polish Soldier) to see and record the violence inflicted on the Jews, but on the other hand, it is not the viewing of violence, the “cruel radiance” (Linfield 2010)2 that could have killed her in Kielce, but rather the town’s residents, with whom she spent her days in the pogrom’s aftermath. She witnessed the violence, but she herself was also in view. I am intrigued by the consequences for the image registered by Pirotte where she could herself have been the target of a hateful gaze as a Jewish woman in postwar Poland, where a “good” or “bad” appearance could determine survival during and after the Holocaust3 (Gross 2007).

One issue to explore is whether Pirotte’s documentation of the pogrom’s victims can be read as a kind of deferred action, a return to the missed encounter with the trauma of the Holocaust, and the loss of her loved ones, who perished in the genocide. This requires a reflection on the position of the female photographer as survivor—a shocked and endangered subject who testifies and mourns as distinct from her possible (professional, political, or ethical) intentions or motivations. The question of survival is thus at the core of this issue—an articulation of the encounter with the Jewish dead and with genocidal violence that allows Pirotte to maintain historical awareness while observing the physical and emotional traumas of the victims, and possibly her own. What is at stake here is a traumatic framing in the act of photographing rather than a traumatic content in the straightforward documentation of the event and its victims. In other words, not the presence of the dead and mutilated bodies in the picture, but the presence of the photographer’s body among these bodies. In this respect, the act of photographing is concurrent with the photographer’s survival within the site of violence, the experience of both past and present survival.

My analysis of the images of the Kielce pogrom is very much inspired by Barbie Zelizer’s concerns regarding the relationship between gender and atrocity pictures in the historical and public imagination (Zelizer 2001, p. 247). In her essay Gender and Atrocity: Women in Holocaust Photographs, she is attentive to how women are “strategically featured” in the photography produced by the Nazis, as well as those photographs taken during the liberation of the concentration camps by the allies. These manifest something like an “overgendering” of the women depicted that Zelizer identifies as “a representational strategy” (Zelizer 2001, p. 256). This strategy, I claim, is closely related to the male gaze in relation to atrocity pictures. Women have been featured as figures of visual speech, as signifiers rather than subjects, consistent with their objectivization and universalization, a phenomenon to which I return. Was this not because the photographs were primarily supposed to convey a clear message rather than create bonds between the people depicted and spectators? And, as it turned out, according to many critics, atrocity photographs reiterated the violence they were supposed to contest, revealing the failure of empathic bonds (Bennett 2005). Here, the question becomes if and under what circumstances this obstruction of empathy can be undone, or accomplished otherwise, and whether the female traumatic gaze might offer a solution to this conundrum.

Lastly, and following Emma Lewis’ observation in Photography—a Feminist History that “the most immediate work of a feminist history is to reclaim some space from the male-dominated narrative”, this paper aims to stress the importance of a feminist framework when addressing these topics. Conceiving a female traumatic gaze is thus an element of a broader gesture aimed at “rebalancing representation” in the field of atrocity pictures and the documentation of political violence, as well as in the figuration of trauma (Lewis 2021, e-book introduction).

2. On Looking (in the Eye)

Before discussing Pirotte’s images, I would like to make a detour via two very powerful images. One is an artistic image, recently presented at an anniversary exhibition entitled Around Us a Sea of Fire. The Fate of Jewish Civilians During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising at the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw (Figure 1). The iris of the eye photographed by Joanna Rajkowska is that of Krystyna Budnicka (Hena Kuczer), a survivor of the uprising, still alive in 2023. It is the eye that saw the event, the eye that still looks, and at which the contemporary spectators look, or look it in the eye/I.4 The artist invites her spectators to view that eye closely as the picture was made on a macro-scale (Budnicka’s eye was magnified 160 times). By doing so, she presents the visual “truth” of this eye, which, under ordinary circumstances, remains unseen: “the complex structure of the iris with its thin, pigmented structure—regularly arranged elevations (trabeculae) and depressions (sinuses, cryptae). The deep, vivid brown color of the iris emphasizes the materiality of the photograph. Presented as a lightbox, it has an almost a three-dimensional effect—it is organic, soft, sculptural, and palpable (Rajkowska 2023). The eye of Budnicka, as part of her body, is not an abstract image, neither is it symbolic or metaphoric. “It is Her eye, material, unique and fragile”, she comments (Rajkowska 2023). A bodily part that, like her corporeal body, was destined for extermination, and survived, as well as recorded, and preserved her survival. Rajkowska returns the power of the witness’s gaze and allows the spectator to connect to this eye that saw and survived. This encounter between the artist and the witness places the viewers right at the center of this essay’s problematics. Yet, there might be something uncanny and a little repulsive, as well as something entirely fascinating and moving about this engagement with Budnicka’s “naked” eye, our primary optical recording apparatus.

Figure 1.

Joanna Rajkowska, We live day by day, hour by hour, minute by minute, 2023, courtesy of the artist.

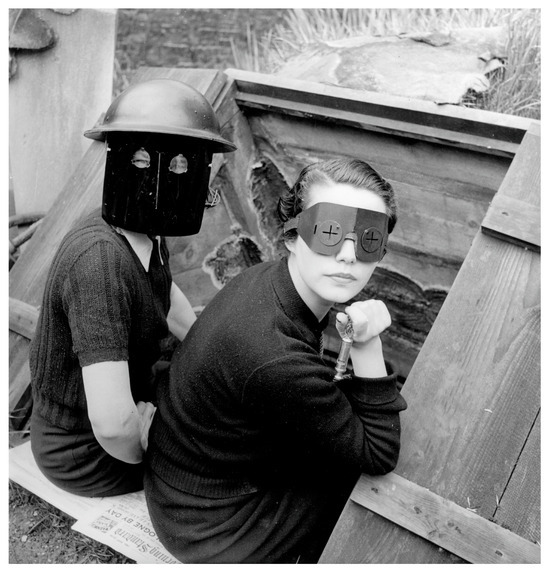

Another image within this rhetorical detour is one taken in 1941 in London by Lee Miller (Figure 2), whose photographic practice began in 1929, when she was the companion of Man Ray, and took up professionally a position as a photojournalist and correspondent, accredited with the U.S. Army from 1942. It depicts two women looking toward the photographer and consequently the viewer, but their faces and gaze are screened by their grotesque (or avant-garde) masks designed to protect them from the blinding effects of firebombs, but also—one could speculate—the objectifying operations of the camera. So, what we are looking at is a kind of visual conversation between the women photographed and the female photographer. Miller’s camera is not capturing its objects, not hunting for prey, but rather depicts a transactional exchange between the photographer and her two subjects: I see you—you see me—I see you seeing me. These women are vulnerable to the bombs rained on London but not, arguably, to the violent ways of seeing and looking endemic to the camera (Penrose 1992; Bourke-White [1963] 2016; Ofer and Weitzman 1998). I am thus reading this photograph as an introduction to the female photographic gaze in relation to war and violence, and to a conceptualization of the witnessing camera of a woman war photographer. As Jean Gallagher, from whom I am borrowing this example, observed: “these two figures ask us to consider how women were looked at during World War II and how they in turn looked through a set of technological contrivances, the literal and figurative, physical, and rhetorical technologies of vision that constrained and constituted how they saw and were seen” (Gallagher 1998, p. 2).

Figure 2.

Lee Miller, Fire Masks, Downshire Hill, London, England 1941, Lee Miller Archives, England.

In considering Julia Pirotte’s work in Kielce, I turned to another photojournalist and documentary photographer working and “fighting” with a camera: Susan Meiselas. In her short essay Body on a Hillside, Meiselas describes her experience as a photographer on the site of violence5—hearing, feeling, smelling, being near the carnage that occurred there. For her, the act of photographing is a means of distancing and mediating what is too overwhelming to be borne by her. For those who view the photograph, it brings them closer, nearly too close. Such dialectics of proximity and distance both reduce and increase the impact of the scene of violence and are responsible for the photography’s in-betweenness. “We, as makers, are the ones going out there, trying to figure out where we can be, where we can stand, what we can hold, what we can do” (Meiselas 2012, p. 117). When looking at Pirotte’s photographs from Kielce, one needs to imagine her presence there, standing next to the bodies of the dead and those of the survivors. She is “on their side” (as a Jewish woman), as well as in her situation as a potential victim and actual survivor, temporally placed between the then of the Holocaust and the now of the (still ongoing) pogrom, as well as the future of the memory of both.

Following Mieke Bal’s important essay His Master’s Eye, I would like to conclude this section by affirming her concept of an alternate form of knowledge: “The mode of vision I am trying to describe is also an epistemology: a different way of getting to know”. In my writing, as in hers, this epistemology “is based on relationality” that “in the visual domain (…) means a seeing radically different from the voyeuristic, asymmetrical mode that has for too long been hegemonic”. Such an approach to the visible world “calls for a suspension of what we think we see, for a recognition of historical positionality, and for an appreciation of relations of reciprocity”. It also requires embracing “many other ways of looking around”, typically diminished and ignored by the fact that “there are certain gazes that take all the authority” (Bal 1993, p. 400). It is thus a form of academic writing that strives to contest that authority.

3. The Witness

Julia Pirotte was born Gina Diament in 1908, in Końskowola, Poland. After persecution as a communist, Pirrote left Poland for Belgium in 1934, where she married and remained until 1940, studying and working in various professions. Fleeing the Nazi invasion of Belgium in May 1940, she left for France, with her Leica, joining other refugees, and subsequently volunteered to work in Marseille. It was there that, in 1942, she was hired as a photojournalist for Dimanche illustrée. It was not her only job. Pirotte was also a resistance liaison agent for the communist-affiliated MOI (Main d’Oeuvre Immigré), a forger of identity papers, and an active member of the Resistance (Diamond and Gorrara 2012). She documented the liberation of Marseille and entered the “Bompard” concentration camp, where she took pictures of Jews days before they were sent to their deaths in the gas chamber of Auschwitz. Her parents and relatives died in ghettos and concentration camps in Poland; her beloved younger sister, Maria (Figure 3), also a Resistance member, was arrested in France, tortured, and executed by guillotine in Breslau6. At the beginning of 1946, Pirotte came to Warsaw where she co-founded the military photographic agency “WAR”. From 1948, she worked as a journalist until her retirement in 1968.

Figure 3.

Julia Pirotte (left) and her sister Mindla (Maria) Diament (right), 1940. Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

She donated part of her legacy to the Jewish Historical Institute in the 1990s. The folders contain 471 prints: a series from Marseille, a document of the repatriation of Polish miners from Lille to Katowice, postwar photography commissioned by Żołnierz Polski, photographs of Jewish children raised in orphanages in Otwock, photographs of the ruins of Warsaw, a series from her trips to Israel, and postwar photographs taken for the Military Photographic Agency. The bulk of her oeuvre went to the Musée de la Photographie in Belgian Charleroi, which retains full copyright permission and holds her negatives7.

As Hanna Diamond and Claire Gorrara remarked, Pirotte was aware of the specific role of women as agents of a political and historical struggle. It is most evident in her visual and textual coverage in Rouge-Midi (25 August to 16 September 1944) entitled Le rôle des femmes dans la bataille (the role of women in the struggle): “I have seen them working illegally, these hundreds of women, transporting weapons, working in intelligence, forging identity cards. (…) [I have seen them, K.B.] shot, strangled, or beaten to death” (Diamond and Gorrara 2012, pp. 459–60)8. Interestingly, she received her first Leica (with an Elmar 50 mm f/3.5) from another woman—Suzanne Spaak: “Seeing that I did not have a job, she advised me to enrol in journalism and photography courses and gave me a Leica, which I am still very attached to” (Pirotte 1994, p. 103; Puchała-Rojek 2006, p. 98).

4. Her Testimony

The typewritten testimony of the Kielce pogrom of 1946 in its complete version is to be found in the Pirotte files at the Jewish Historical Institute. An abbreviated version was published on several occasions in the 1990s. According to Pirotte, on 4 July, she was summoned by the editor in chief of the Żołnierz Polski, where she worked as a journalist and photojournalist. He informed her of the pogrom in Kielce and commissioned material for the journal. She was to be accompanied by a soldier. “You have to pretend. They keep murdering Jews on trains, lurking at the stations”, he warned her, according to her testimony. And then she continues, “And I am Jewish”. This response requires some time to interpret. One can only hypothesize that Pirotte was terrified; if recognized as a Jew, she too was at risk. Perhaps she feared she would not be sufficiently objective to provide accurate documentation of the event. Or, contrarily, she considered herself the best qualified to provide the most accurate coverage of the event. The interpretive possibilities are numerous and none should be categorically excluded. Was it the threat to her life or her capacity for objectivity that worried her most? While in Marseille, she was politically self-conscious and engaged, a woman photographer and a fighter. Who was she then in Kielce? There is reason to take a closer look at her written testimony:

What is going on here, I asked one of the people on the street. I don’t know anything. I have not seen anything. I heard the same answer over and over again. Nobody knew a thing; nobody saw a thing. Here is what I managed to gather:

Yesterday morning a rumor was spread that Jews killed a Polish child and drew its blood for matzah. Instantly, the agitators turned up, especially women. Two women ran the streets of the city, screaming: “People, Jews are murdering Polish children”. In a few minutes a crowd gathered and moved to Planty Street, where 100 mostly young Jews with their families lived at number 7/9. People who had been rescued from death camps or had returned from the Soviet Union. Near Kielce, they leased a piece of land and were trained to cultivate it under the supervision of an instructor. From there they were to go Palestine already as an organized kibbutz “Ichud”.

Then, Pirotte reports what the survivors were telling her horrible, gory, and brutal narratives.Soon, the attackers were joined by workers of the Ludwików metal plant who wielded crowbars and metal pipes and were particularly brutal. The local authorities sent in the military to contain the situation. Yet the military joined the crowd. They sent in the militia that also joined the attackers. From the provincial committee building, we went to the hospital where the wounded were being treated. When the pogrom was stopped around 3 p.m. there were already many killed and (...) I was able to see how massacred, desecrated the corpses were, by taking photos of 42 corpses—men, women, children. The naked corpses were lying in a large courtyard.

She then continues with the description of the funeral:I remember the naked corpses laying in a huge courtyard. A young woman was desperately looking around. She wouldn’t stop. She was searching for her family members among the dead. All her loved ones had been killed in the pogrom.

One can clearly see that the photographer’s account of the events is unsparing. She misses nothing of the brutality and absurdity of the situation.At the head of the procession rode a dozen trucks, carrying the coffins. Delegations of the local institutions followed with people holding banners and posters. Among the first walked the delegation of the Ludwików metal plant, the same people who proved so brutal during the pogrom. The authorities probably ordered them to participate. (…) A woman in a headscarf leaned over to me: “Yesterday they beat them; today they must walk in the procession as a punishment. What a joke!”(Pirotte 1946)

According to anthropologist Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, the events in Kielce changed the perception of Polish postwar history. The war ended in 1945, but, as she claims, the Holocaust continued. According to the testimony of Niusia Borensztajn-Nester, a woman survivor of the pogrom and a protagonist in Tokarska-Bakir’s monumental study Pod klątwą. Społeczny portret pogrom kieleckiego (Under A Curse. A Social Portrait of The Kielce Pogrom), based on in depth archival research, it was mainly the militiamen who were responsible for the Kielce pogrom. Part of its context was the ordinary, everyday violence against Jews, generally tolerated by the postwar authorities. Reports of extortion and murder by militiamen in 1944–1946 were systematically concealed, one of the biggest problems of postwar communism. Communist authorities were, in fact, embarrassed by the Kielce pogrom; hence, they blocked the investigation and public transmission of the event (Tokarska-Bakir 2018, 2019). The confusion around the origins of the event became a confusion of the memory of the event in the following decades. Eventually, shame about the pogrom enabled its official acknowledgment to be widely transmitted. Pirotte was a devoted communist of the Western variety, as one of her friends recalled (Pirotte 2012). She returned to Poland to participate in the establishment of the new order, and yet she seemed to both belong and not belong in many complex ways. Her political commitments cannot be ignored in framing her photographic and textual productions in the aftermath of the event.

At the end of her written testimony, Pirotte adds a postscript: “Apologies for the poor technical quality of the photos. I was robbed of three Leica films (118 negatives) and had to redo the negatives from proofs. I think I was the only journalist and photojournalist present in Kielce” (Pirotte 1946)9. One can only wonder whether it was her identity as a photographer or as a Jew that made her unwelcome when she arrived on the scene.

5. Her Gaze

The pictures of the pogrom differ widely. Some are of a particularly poor quality, low resolution, out of focus, and too contrasty. They betray not only the photographer’s proximity to the event, the unimaginable fear, her confusion, or disorientation, as present in her written testimony, as well as her wish to document the event accurately and truthfully (the ultimate task of the photojournalist). Pirotte was photographing both rapidly and slowly, rapidly when she recorded scenes of violence, slowly when she recorded the crime scene and its environment. At present, only a small number of the images taken in Kielce are known, the rest that are lost can only be imagined. One might think of them as “poor images”, for they are actually images of images, rephotographed several times and in several different ways, variously cropped and taken from various distances.

Moreover, in the archives of the JHI, there are photographs whose provenance or authorship are obscure. There are those with “Pirotte” written on their index cards in pen or pencil and photographs with no author at all. For the purposes of this essay, I assumed that, as Pirotte claimed, she was the only one taking the pictures. Yet, the images whose authorship is not clear are reproduced in this article as pictures of visual objects, (i.e., photographic reproductions I took in the archive). Considering these images as constituting a distorted archive of the event, its obscurity reflects the confusion surrounding the event and its confused memory.

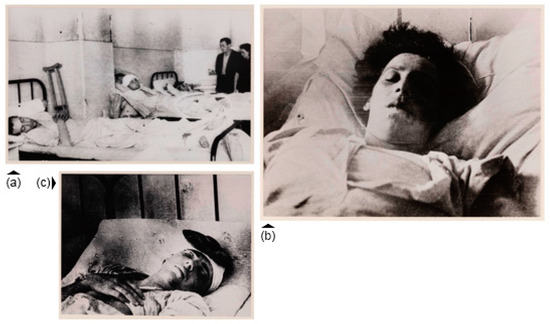

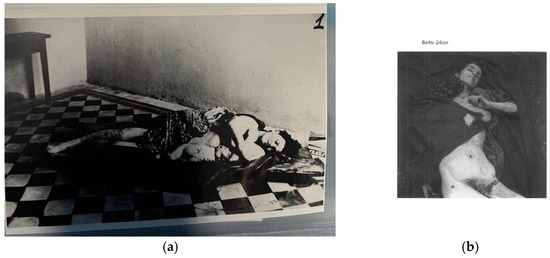

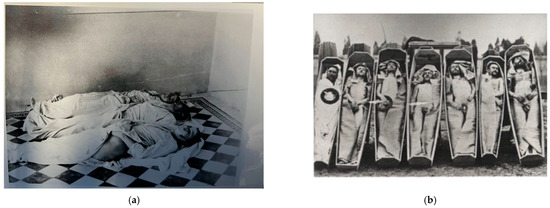

Among the photographs in the archives of the Jewish Historical Institute are those taken in the hospital depicting wounded survivors suffering from various kinds of injuries, and photographed from the perspective of a visitor standing by their bedside (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). There are several differently cropped images deposited in the archive. There also exist photographs of corpses on the hospital floor; one of a woman and a baby, and three men partially covered with white sheets on the floor tiles, images of bodies piled up in the morgue, mutilated corpses photographed in close-up in their coffins, scenes from the funeral (groups of people marching, standing, and talking), and more images of coffins and of people mourning.

Figure 4.

(a). Men wounded in the Kielce Pogrom, St. Alexander Hospital, Kielce 1946; (b). A woman wounded in the Kielce Pogrom, St. Alexander Hospital, Kielce 1946; (c). A man with a bandaged head, wounded in the Kielce Pogrom, St. Alexander Hospital, Kielce 1946. Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Figure 5.

(a). Mother and son, victims of the Kielce Pogrom, 1946 (index card with an annotation: Regina Fisz and her son Abram, as well as author: Julia Pirotte). Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish His-torical Institute in Warsaw. (b). Corpse of mother at Bergen-Belsen, 1945 reproduced in (Zelizer 2001, p. 258).

Figure 6.

(a). Victims of the Kielce Pogrom, 1946 (index card with an annotation author: Julia Pirotte). Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. (b). Photographer nknown, Bodies of militants of the Paris Commune, 1871, source: Art press l’album, Paris, Editions de la Martinière, 2012, p. 38, public domain.

The image of Regina and Abram Fisz (Figure 5a), the dead mother and child, takes time to be read, given the bruises and other marks of slaughter. The camera must have been positioned close to the bodies, a little above the level of the ground but not too close. The depiction of a murdered mother summons another: “the corpse of mother at Bergen-Belsen, 17 April 1945”10 (Figure 5b). Whereas the dead woman photographed in Bergen-Belsen is body frontally exposed by the camera, the Kielce mother’s body is relatively shielded by her arms and draped cloth and is thereby somewhat resistant to a prurient or invasive gaze.

There also exists an image of three male victims lying on the same hospital floor (possibly shot at the same moment in the same room—(Figure 6a) recalling another historically charged image, this time of Paris communards, naked in their coffins (Figure 6b). One could surmise Pirotte had this image in her visual memory while pointing her camera at the dead Jews in Kielce. Why such an association—for some, possibly outrageous? The female traumatic gaze, which is argued for in this essay, is very much about making connections and overcoming well-established routes of historical thinking and feeling.

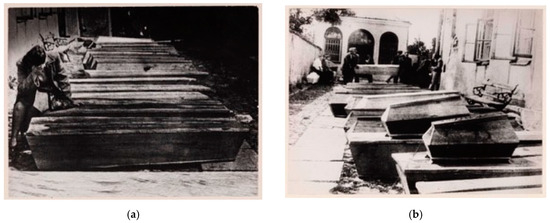

Another image to consider is that of a woman sitting on the top of a coffin, covering her face with a hand, her head bowed, a figure of mourning (Figure 7a). Is it perhaps the same woman as the one described by Pirotte desperately searching for the corpses of her relatives? And are the men in the background in the photographs depicting small coffins placed on top of larger ones (Figure 7b) wrapping things up before the funeral doing the work not of mourning? One cannot know.

Figure 7.

(a,b) Coffins with the corpses of the victims of the Kielce Pogrom, St. Alexander, Kielce, 1946. Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

There are scenes from the funeral: men, women, and children marching, some of them look directly at the camera. Some of them seem solemn, angry, and lost. It is hard to tell who they are or what they feel and in what role and capacity they are present and what, if any role, they played in the pogrom (Figure 8a,b).

Figure 8.

(a,b) Funeral procession of the victims of the Kielce Pogrom, including soldiers of the Polish Army, Kielce, 1946. Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

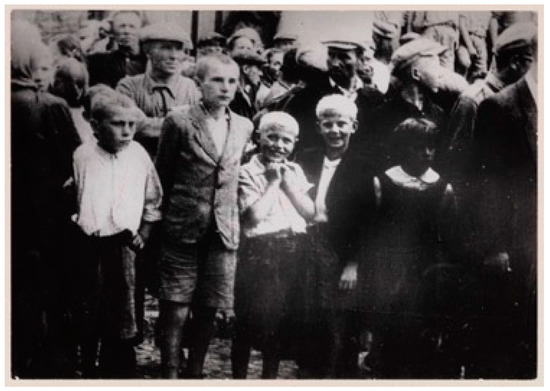

And there is the picture of children looking at the camera and smiling (Figure 9). This is one of the most intriguing pictures on many levels. First, one can consider the alibi for the pogrom, the alleged kidnapping and torture of a Polish child by the Jews of Kielce. But why are some of these kids smiling or even laughing? Was this a “joke” to them? Or is it merely the act of being photographed? How does one imagine their future, living in the aftermath of hatred and violence, and surrounded by the silence and lies spread by the adults, some of whom Pirotte photographed? How are we to relate to the protagonists of this image?

Figure 9.

Children at the funeral of the victims of the Kielce Pogrom, Kielce, 1946. Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Last, but not least, Pirotte most probably photographed survivors of the pogrom, standing in groups, exchanging looks, talking, and gesturing to one another (Figure 10a,b).

Figure 10.

(a,b) Jewish survivors of the Kielce Pogrom, at the victims’ funeral, Kielce, 1946. Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

In this discussion, I include images not necessarily taken by her, but which are archived with hers. Despite the multiple confusions and interventions in the archive, there is nevertheless a dynamic that I propose to call the female photographic gaze in relation to atrocity and violence. Such a gaze produces images from within the event and does not assume an external position (neither bodily, affective, nor mental), a position of detachment and control. It contradicts the division between the inside and the outside, the subject and object, thus refusing the objectivization that accompanies knowledge in the traditional sense. Such a gaze produces images that are porous, present as an outcome of an encounter, not an object that can be possessed. As Ariella Azoulay puts it: “an object in the world, and anyone, always (at least in principle), can pull at one of its threads and trace it in such a way as to reopen the image and renegotiate what it shows, possibly even completely overturning what was seen in it before” (Azoulay 2008, p. 13). Such a gaze produces relational images, images requiring the work of associating, connecting with the event (and its aftermath) if it is approached properly. “When and where the subject of the photograph is a person who has suffered some form of injury, a viewing of the photograph that reconstructs the photographic situation and allows a reading of the injury inflicted upon others becomes a civic skill, not an exercise in aesthetic appreciation” (Azoulay 2008, p. 14). I return to that “civic skill” at the end of the essay.

6. Acknowledging Atrocity

Among the many images of political violence, atrocity photographs are often thought to be complicit in the horrors they depict. The very reproduction and display of these images is deemed problematic, both because of the possible traumatization of the viewer, as well as those being looked at. Jay Prosser directs the reader’s attention to the place of “bodily vulnerability” within the conventions of such imagery (Prosser 2012, p. 9). He remarks on the importance of the relationship between the body depicted in the photograph and that of the person viewing the photograph. To this, I would also add the body of the intermediary, of the photographer herself. This is something that gets in the way and that needs to be acknowledged in the process of interpretation. I am not so much interested in the imbalance between these bodies—some are vulnerable and in danger, others are safely looking, some are protected by their professional situatedness or temporal distance, etc.—as I am in the complicated exchanges that seem to be occurring between them.

It is therefore crucial to acknowledge what Ariella Azoulay emphasizes in her numerous studies and photographic collections, namely, that the act of depicting atrocity never occurs outside of it: “It is rather an activity that takes place as part of the atrocity and of the conditions that enable its appearance, its very being” (Azoulay 2012b, p. 249). Moreover, she shifts the focus and dislocates atrocity by claiming that it is not about the photographic capture, placing violence in the central position as an object of the gaze, but rather an acknowledgment that “a photograph pictures atrocity when it is created under disaster circumstances regardless of what it captures, even when no visible trace of the atrocity is actually left in it” (Azoulay 2012b, p. 251). Thus, in order to speak of antisemitism and the long shadow of genocide that haunts Pirotte’s photographs, one need not look for the markers of this violence inside the images, but in the context of both the then (of their taking) and the now (of their presence in the archive):

the atrocity that they picture is not reducible to that which has been established as its visual attributes. (…) Sometimes, something of the horror might emerge from the centre of the frame and help restore it. At other times it is situated entirely outside the frame. In both cases, however, if the photograph was taken at the site of disaster, it bears the stamp of horror and pictures atrocity.(Azoulay 2012b, p. 251)

Such a shift in thinking about the relationship between the image and violence is also essential to identify the operations of trauma in the visual field. (Saltzman and Rosenberg 2006) It also lifts the burden of guilt (of perpetuating or re-enacting violence) from the image or the photographer, allowing one to recognize a more complex network of forces and interdependencies. In this regard, I propose connecting this shift to the notion of a female photographic gaze, in opposition to the male gaze, and in specific relation to atrocity images. Prosser claims that photography “responsible for producing atrocity as spectacle” (Prosser 2012, p. 9), and the paralyzed viewer/consumer, with little sense of the complexity of political and historical realities, is then transfixed by the horrific representations. In my opinion, this is precisely the male gaze that is responsible for this spectacle, and hence the necessity to find an alternative gaze, which I propose to call female traumatic gaze. This gaze mediates atrocity in a way that allows the viewer to, rather than remain paralyzed, become stimulated and encouraged to restore the larger context of the represented disaster they are part of.

In her discussion of atrocity pictures, Peggy Phelan stresses their performative aspect and inquires what is it they do to their spectators. She focuses on “how some atrocity photographs gain power by exposing both the given-to-be-seen and the blind spot that is central to seeing a photograph. Indeed, insofar as some atrocity photographs are traumatic, it may be precisely because they expose this blind spot that constructs the limit within the act of seeing as such” (Phelan 2012, p. 51). Phelan invites her readers to investigate this blind spot, what is subconsciously ignored or missed in the encounter with the horror of political violence in the visual field. What can be considered to have the annihilating power, she says, is not the depiction of horror, but the comfort of the blind spot. The fact that one looks away or does not acknowledge the reality of actual atrocity and one’s implication in its production and consumption. She argues that some respond to the exposure of their blind spots with violence, “with a more aggressive and displaced will to know” (Phelan 2012, p. 61). In Pirotte’s photographs, the will to know seems to be replaced by the drive to connect and mourn, the necessity of bearing the burden of Jewish extermination and to its testimonial. Phelan discusses the difference between atrocity images that interpellate us in the now of their production (performative), and historical images that document or even narrate events that have already ended (even if their aftermath remains painfully pressing) (constative):

When one sees an atrocity photograph for the first time, it can be traumatic. Indeed, we often look away. But when we return to it, the experience of looking has created a narrative that produces a kind of pastness, if only at the level of: “I have seen this before and survived seeing it”. Looking at an atrocity photograph repeatedly can transform the image from a performative to a constative expression.(Phelan 2012, p. 53)

The pastness she is referring to is the experience of survival in the act of looking. What could this survival mean? Is it the overcoming of trauma or its installation? In her conclusion, Phelan claims that “some atrocity photographs resist historicity and retain their performative force. In their resistance to pastness and the consolations of narrative coherence, atrocity photographs also share some aspects of the psychoanalytic account of trauma” (Phelan 2012, p. 54). Their incomprehensibility remains outside the narrative of the past, yet cannot be obliterated. They are within our history without being a legitimate part of it, neither mediated nor understood. Such images act like Freud’s overpowerful stimuli that breach the protective shield of history as narrative. They are unexpectedly encountered by an unsuspecting subject who remains unable to assimilate them, too vulnerable and exposed to their recurrence (Freud [1920] 1955; Caruth 1996, pp. 57–72). Freud himself offered an analogy between the workings of the traumatized psyche and photography. In Moses and Monotheism, he speaks of photographic exposure in relation to the psyche’s receptivity and ability to deposit sensations as imprints. Experiences (as elaborated impressions) can be “developed” just like pictures after “any interval of time” (Freud 1939; Iversen 2012)11.

When conceptualizing atrocity photography in dialogue with Azoulay, Phelan, and Freud, one might conclude that it is a convention that requires considering the unconscious dimension of the photographic medium: the registration and transmission distinct from the consciousness or intentionality of its author. The photographic image, even when developed, reproduced, and viewed, still contains an unmediated dimension, its secret or blind spot, something that resists integration and explanation. It may go beyond the traumatizing effect of atrocity pictures, exceeding what is recorded but not assimilated.

In his essay on Susan Meiselas (in the form of his letter to her), Eduardo Cadava developed what Freud conceived as a relationship between photography and the psyche:

Every photograph has to be read in relation to its secrets, to all the histories that are sealed within the image itself. (…) there can be no encounter without secrets, without relation to the night of knowledge in which they begin, and this is why (…) the meaning of a photograph is never present, never given to us directly, always related to something both earlier and later that remains hidden, always related to an entire network of historical relations.(Cadava 2021, pp. 346–47)

The interpreter is like an analyst or an archaeologist, for a photographic image “requires so much excavation of everything that underlies it (…) The image always demands a labor of exploration and this because (…), as Allan Sekula has written, “an image is not worth a thousand words; it is worth a thousand questions’” (Cadava 2021, p. 347). What is overwhelming is not the contents of the picture itself, nor the violence depicted in it, but rather that the size of the blind spot and the task of the one who is to perform the labor of excavation requires the posing of questions rather than the positing of answers.

7. Gender and Atrocity Pictures

Analyzing the photographs produced during the allied liberation of the Nazi camps, Barbie Zelizer claims that there exist two forms of public expectation. First, the photos documenting what was seen by the photographers is meant to be realistic, perceived as “accurate, fact-driven”, and unmanipulated, denotatively recording “events as they were” (Zelizer 2001, p. 249). Second, one perceives these images as “markers of a larger story, infused with broader cultural meanings that did not necessarily undercut the photos’ referential force but contextualized it against a more general understanding of what had happened” (Zelizer 2001, p. 249). In the second approach, the photos can be deprived of their referentiality to serve as symbols or metaphors, in the service of universal or propagandistic purposes and claims. What transpires in both approaches, however, is the urge to know and to be moved or mobilized by that knowledge, which is given to be seen. The image needs to be precise and powerful, underwritten by the photographers’ desire to see and show and, in their dissemination, to the viewers’ desire to learn and know. This I propose to call a male photographic gaze in relation to images of political violence. It does not necessarily have to relate to the gender of photographer, viewer, or person depicted in the image.

In her essay, Gender and Atrocity: Women in Holocaust Photographs, Zelizer points out that women visually documented the war and its aftermath, including such photographers as Lee Miller and Margaret Bourke-White, and as journalists who covered the Nazi crimes committed in Europe as reporters (e.g., Iris Carpenter, Martha Gelhorn, and Marguerite Higgins). She also reminds us that, during the war, the experience of women was all encompassing, as victims, perpetrators, resisters, militants, and bystanders. Her argument is thus that women should, in principle, be represented in all their various roles. However, she observes that within the existing visual documentation, they seem to have been represented in strategic ways insofar as their “gender was either wholly absent or wholly present” (Zelizer 2001, p. 256). In no case was it a question of giving a voice (and image) to specific gendered experiences, but rather to reiterate stereotyped versions of femininity. Citing Claudia Koonz, she observed that “women’s experiences in the camps (and elsewhere, K.B.) were flattened beyond repair, despite the hundreds of documents that attest to the multidimensional existence of thousands of women prisoners” (Zelizer 2001, p. 257; Koontz 1994). It is not thus the lack of evidence about women’s various roles in the war, but rather its very specific, selective editing that is the cause of this absence (Rittner and Roth 1993).

Remarking on what she terms the “overgendering” of women, Zelizer notes that their representations are underpinned by their purportedly more vulnerable and fragile qualities, which make the crimes against them look even more horrific. But, of course, women were not only victims. As perpetrators (for example, as prison guards or concentration camp personnel) in the immediate postwar period, they were depicted as “less human”, cruel beyond the limits of “natural womanhood”. Women survivors in turn were repeatedly represented as resilient nurturers and protectors of domesticity, despite the brutal conditions of life after trauma. As Zelizer writes: “Overgendered representations of survivors were thereby doubly codified: both as portraits of horrible depravation and as attempts to maintain remnants of dignity in a world where dignity no longer prevailed. Collective perseverance and the ability to call upon one’s role as nurturer in order to reinstate normalcy were key here” (Zelizer 2001, p. 260). Also, female witnesses, women looking at atrocities, were depicted not to fully acknowledge the specificity of their experiences, but rather to stress, again, the enormity of the crime via photography (Struk 2008).

Why is it necessary to imagine alternative ways, or uncover alternative representations, or reach beyond the putative male gaze of editing and framing atrocity while looking at the images from over 60 years ago? Zelizer claims that, even at present, the same representational patterns persist and recur whenever images of violence, genocide, and horror are publicly circulated (Zelizer 2001, p. 267). This repetitive compulsion seems to be challenged—but only to a certain extent—by social media and the amount of vernacular coverage of atrocities around the globe by women and other people resisting the dominant male gaze in war, conflict, and catastrophe regarding the acts of visual witnessing and reporting.

8. The Female Traumatic Gaze

By conceptualizing the notion of a female traumatic gaze, I begin with Laura Mulvey’s foundational essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema of 1975, inspired by the re-emergence of Anglo-American feminism at the end of the 1960s and its subsequent assimilation of Freudian and Lacanian theories. As she argued, in the mainstream field (i.e., classical Hollywood cinema), women have been portrayed to respond to the expectations, desires, and fantasies of men, and thus function to confirm and secure the patriarchal (visual) order of sexual difference. Within this patriarchal regime, women are always and only defined in relation to male characters. They exist as objects of desire, whose function is limited to their “to-be-looked-at-ness”, and who are therefore fashioned as a fetish and object of (male, heterosexual) desire. In my argument, the male gaze in regard to traumatic photographic imagery exists in mainstream photojournalism, but also in history books, museum exhibitions, and the conventionalized “ways of seeing” war and violence. Such a male gaze is driven by the desire to show and shock the viewer, as well as by the desire to know what one is looking at, and transmit that shocking knowledge. This is the gaze implicated if not complicit in the spectacle of violence reproduced by visual media: the gaze enacted by photographers, editors, archivists, historians, etc.

Additionally, the position of the photographer is a privileged one of distance and control: I am there for you, for you to see, for you to know, you can rely on me, I am doing this on your behalf, the image will move you, the image will make you remember, etc. The male gaze produces what Azoulay calls “planted pictures”, i.e., images violently inserted in our private “albums”. What distinguishes them is their mode of transmission and presence: “They are planted in the body, the consciousness, the memory, and their adoption is instantaneous, ruling out any opportunity for negotiations as regards what they show or their genealogy, their ownership or belonging” (Azoulay 2008, p. 13). Surely, the responsibility for such a gaze as it pervades social reality should be assigned not only to those taking pictures, but also to the ones reproducing and circulating them (e.g., editors, publishers) as well as their interpreters. The female photographic gaze works against the reduction “of photography to the photograph” and against the urge “to identify the subject”, but rather invites the viewer to watch the photography (taking time). The female gaze is driven by the desire for restoration, for connection. Pirotte is not “capturing” the victims, her camera is not aggressive, but attentive; confused, lingering rather than shooting. These images are evidence of her fragile relation to and resistance against the genocidal violence. As another scholar of cinema, Vivian Sobchak, with regard to cinematic depictions of death, states that one needs to distinguish between the fixed look (which objectifies what it sees and presumes its own technological superiority) and the helpless, endangered, and interventional gazes (Sobchack 1984, p. 295) of those who record images in the face of mortal danger and death. All three gazes suggest an embodied presence and proximity to the scene of violence. While the first one points to the impossibility of action beyond the registration of the event, the second reveals the possible threat and thematizes it within the image; the third one is resigned to the safe position of the maker of the image (in hiding) and depicts both the death of the other and the possibility of one’s own death (Sobchack 1984, p. 295). In addition to these three different cinematic gazes, Sobchack introduces what she terms the “human stare”, which can either be fixed by shock and disbelief in the face of horror (Sobchack 1984, p. 297) and reject any available perspective or convention to look at and depict the death of the other, or settle and engage the gazes of the others “inscribing the intimacy and respect and sympathy it feels with those who die in its vision” (Sobchack 1984, p. 297). I very much admire the efforts Sobchack made to differentiate the different attitudes to the scenes of violence and death and one’s implication in them. The female traumatic gaze I am postulating here is closest to the settled and engaged rather than the fixed and shocked human stare. Sobchak’s theory lacks, however, the third component in this scene of intimacy: the spectator.

When thinking about the Holocaust in the Polish collective memory, and the racial hatred in the immediate postwar period, what seems particularly painful from the contemporary perspective is that, to such a large extent, Polish society accepted the Nazis’ decision that a tenth of the population was condemned to death, marked with a yellow star, deprived of property, imprisoned in the ghetto, and exterminated. Much of the population remained silent or appropriated Jewish property and failed to acknowledge or cultivate the memory of their lives and tragic fates. The problem seems to persist, as many scholars have shown in recent years, because the poisonous language of nationalism that imposed the division of Poles and Jews, as if the Jews exterminated were not Poles, as if the war’s violence and its postwar manifestations were not aimed at fellow civilians. To unlearn these nationalistic and genocidal schemes and reject the “planted pictures”, one may want to start speaking the language of citizenship Azoulay offers. “It starts with the act of spectatorship”, she asserts, “we look at the photograph of disaster as something that concerns us. Concerns us not because we have to identify with the victim, but because we are governed by the same regime that produced this disaster” (Azoulay 2012a). From this perspective, Pirotte’s gaze is not that of a Jew, a victim, or survivor, but rather that of a co-citizen, then and now. Azoulay proposes to counter the language that participates in the production of these disasters with the new visual language of citizenship. The control and production of visuality has to be countered. It is necessary, therefore, to recognize oneself in the image of the disaster, not via an act of empathy, or identification with the victim, but in being implicated, in realizing we are governed by the same forces that instrumentalizes this disaster and blinds us. The female photographic gaze works against this blinding.

9. Conclusions: On Injury and Bruise

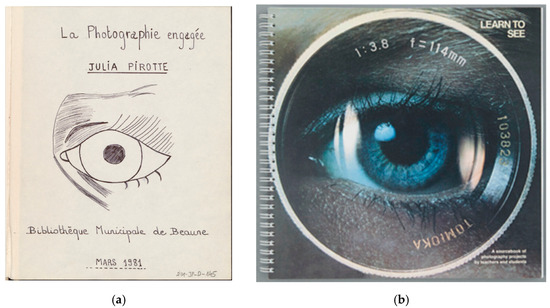

In the archive of the Jewish Historical Institute, I came across a hand-drawn cover of La Photographie engagé (engaged photography) by Julia Pirotte, for an exhibition at Bibliothèque Municipale de Beaune (1981). It illustrates the photographer’s engagement by means of a wide-open eye (Figure 11a). The eye that takes in what it views without blinking, the eye that sees too much but does not wish to miss anything, the eye that stays alert. Another female eye, this one photographed, can be found on the cover of a 1974 book by Susan Meiselas entitled Learn to See. A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Students and Teacher (Figure 11b). In this book, she provides visual lessons in the photographic language, including the issues raised in the representations of the underprivileged or marginalized, or those excluded from the visual field.

Figure 11.

(a). Title page of the guest book for Julia Pirotte’s exhibition Engaged Photography at the City Library of Beaune, March 1981. Courtesy of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. (b). Cover of Susan Meiselas book Learn to See. A Sourcebook of Photography Projects by Stu-dents and Teacher, 1974. Photo: Katarzyna Bojarska.

As unlikely as this correspondence between Pirotte and Meiselas might first seem, it allowed me to conceptualize the female traumatic gaze as that which allows the spectators to unlearn the objectifying and distancing gaze as the precondition for knowledge. Not only the knowledge of the events and the world more generally, but that form of intrasubjective communication that fosters connections between the viewing subject and those who are photographed (even after their deaths). Like Meiselas, Pirotte spoke to those she photographed and those she met while on assignment, clearly indicated in her written accounts, even more so in the excepts not included in this text. For both women, rather than a framework for visual knowledge production and control, distance seems to be a means of protection, even a lifesaving one. Their cameras, one could say, function as protective shields or masks (like these ones in Miller’s image from the London bomb shelter) that allow them to get close enough to make the exposure, and not too close to steal it, establishing a relation within the encounter, not trying to win a battle.

In The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry writes that “the main purpose and outcome of war is injuring” and that this “can disappear from view along many separate paths” (Scarry 1985, pp. 63–64). What I infer as Pirotte’s point of view during the Kielce pogrom, is the need to record and preserve the event, but in doing so, to also provide the shared space for empathic viewing, for staying in touch, to be connected to the injured bodies, to paying attention to the complexities of the postwar situation. Her gendered body makes her a gendered viewer, her Jewish body makes her a Jewish viewer, and her Polish body makes her a Polish viewer of “the radical damage done to bodies and the complex ways that damage is kept in view” (Scarry 1985, p. 69).

Pirotte’s eye was thus devoted to the task of witnessing, bruised by multiple scenes of violence and the experiences of pain. One could inquire—paraphrasing Cadava from his letter to Meiselas—if she was drawn to the scenes of death and destruction because of her compassion, her devotion to memory, and her political commitment to exposing injustice, or because she wanted to take photographs, those “photographs (which, K.B.) are also photographs of what makes photography what it is, and what it is not” (Cadava 2021, p. 404).

I proposed to look at Pirotte’s photographs taken in Kielce as an incarnation, or instance of the female traumatic gaze. This is one that organizes the relationship between trauma and photography through a critical and gendered mode of seeing and understanding the relations between memory and trauma, body and archive, vision and death, and Jewish death, presently archived and housed in the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. My analysis intended to open up the discussion of atrocity pictures, using a new perspective that fully encompassed gender, trauma, and critical approaches to memory and visual culture that represented and disseminated political violence. I investigated to what extent Pirotte’s documentation of the aftermath of the pogrom could be read in line with Freud’s concept of Nachträglishkeit in her encounter with the trauma of the Holocaust, the loss of her loved ones, and her position as the sole survivor. But, this photographic documentation has another dimension that is important to acknowledge. It speaks through the gaze (settled and engaged human stares) that is not exclusive to the Jew, the victim, or the survivor, but rather that of a co-citizen, back then in 1946 and at present, at whatever time reading of this essay occurs.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Centre for Science, grant number: 2021/41/B/HS2/01437.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Agata Pietrasik (Freie Universität Berlin), and Daniel Véri (Central European Research Institute for Art History, Budapest), for their invitation to the conference Representations of the Holocaust in the Cold War Eastern Bloc: The Early Decades, where I presented the first draft of this essay. I am grateful for all the feedback I received there. I am grateful to my wonderful student, Hanna Dudkowiak, who accompanied me in the research for this article, including a visit to the Jewish Historical Institute photography archives and to Agnieszka Kajczyk, the Head of the Heritage Documentation Department at the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw for her support. I am grateful to Tomasz Łysak for his interest in the theme of the traumatic female gaze and his patience. Lastly, I am extending my utmost gratitude to my dear friend Abigail Solomon-Godeau for her loving reading and editing of this essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I subscribe to a concept of the gaze as a complex relationship between what constitutes the subject as seen, or on view in the visual field, organized by both technological and discursive forces, and an embodied and historically specific act of seeing as formed both in conformity to and also in opposition to these forces. My approach is inspired by numerous psychoanalytic and feminist theories, yet also detached from them (Silverman 1996; Bal 1993; Mulvey 1975; Azoulay 2008, 2012a; Solomon-Godeau 2010, 2017). |

| 2 | As much as I disagree with most of Linfield’s argumentation that attempts to counter the criticism of atrocity photographs (as exploitative of the people depicted and contributing to consumerism and voyeurism of looking at political violence) with a return to the humanist and humanitarian gaze they promote, the phrase “cruel radiance” seems to me worth referring to. For criticism see (Zarzycka 2011). |

| 3 | In his novel Ocaleni (Survivors), 1986, as well as in other writings, Stanisław Benski, a Polish Jewish writer and survivor, concentrates on the looks and appearances of his fellow Jews. According to him, in order to avoid death, one’s gaze needed to be neither too bold nor too submissive (the latter was considered “Jewish”). The dark, black eyes signified a Jew, and so did “sadness” that was attributed to his or her gaze. Even the “Aryan-blue” eyes would be bad if perceived as expressing this specific kind of sadness that “all Jews had during the occupation and after”. The eyes thus first betrayed the victim and then the survivor. According to many writers, the obsession with “bad” eyes or “bad” looks kept haunting the survivors long after the war. See (Buryła 2012). |

| 4 | This project might be contemplated in relation to The Eyes of Gutete Emerita (1996) from Alfredo Jaar’s famous Rwanda project, where the artist photographed the eyes of the female witness and survivor of the massacre in a church where 400 Tutsis were killed by the Hutu during Sunday mass. Gutete Emerita witnessed the death of her husband and two sons. Jaar’s installation invites the spectator to look her in the eyes. See Solomon-Godeau (2005). |

| 5 | The picture entitled Cuesta del Plomo, taken by Maiselas in 1981, depicts a mutilated corpse on a hillside outside Managua, a site used by the National Guard of Nicaragua to perform executions. |

| 6 | In 1956, Pirotte travelled to Wrocław and took a photograph of the guillotine, a hand cut off by the frame of the picture holding the guillotine above the ground. |

| 7 | Digitalised images can be found here: https://fotomuzeum.faf.org.pl/ (accessed on 1 September 2023). |

| 8 | As the authors later indicate (p. 467), it was not until the publication of the catalogue of Pirotte’s work in the 1990s that the role of women was acknowledged, but also more precise information about the participants’ and the victims’ identities was provided. The authors interpret this as evidence of a certain shift in historical understanding, prompting attention to the subject position of the historian, or in this case, the photographer: Jewish, female, and communist. |

| 9 | It is said that from Pirotte’s three Leica film rolls, approximately 16 photographs survived. According to the Polish filmmaker, photographer, and writer, Joanna Helander, the rest of the images were destroyed by the Security Office (Pirotte 2012). However, it is not clear, as Pirotte claimed on another occasion that fearing the Security Office, she donated the photographs to “an institute”. No specific institute was named nor has any collection of such images been discovered. |

| 10 | This picture is reproduced and discussed by Barbie Zelizer in her Gender and Atrocity: Women in Holocaust Photographs in relation to another picture from the liberation of Bergen-Belsem depicting the corpses of two children (Zelizer 2001, p. 258). The latter image BU 4028 was taken by Oakes, H (Sgt) No. 5 Army Film and Photo Section and is archived in the Army Film and Photographic Unit of the Imperial War Museum, London. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205214652 (accessed on 1 September 2023). The image of the dead mother as reproduced by Zelizer is nowhere to be found in the online collection of IWM, however, its cropped version, a close-up the the victim’s face and upper part of her covered torso is in the collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Hadassah Bimko Rosensaft https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1083229 (accessed on 1 September 2023). |

| 11 | The task of the analyst, according to Freud, was akin to that of an archaeologist who reconstructs an object of his study out of traces and dispersed fragments. The forgotten and repressed elements of the past are awakened during the analysis in free association or during the transference. |

References

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. Translated by Rela Mazali Ruvik Danieli. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2012a. Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2012b. The Execution Portrait. In Picturing Atrocity. Photography in Crisis. Edited by Jay Prosser, Geoffrey Batchen, Mick Gidley and Nancy K. Miller. London: Reaction Books, pp. 249–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, Ulrich. 2002. Spectral Evidence. The Photography of Trauma. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, Mieke. 1993. His Master’s Eye. In Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision. Edited by David Michael Levin. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 379–403. [Google Scholar]

- Batchen, Geofrey, ed. 2009. Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Jill. 2005. Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke-White, Margaret. 2016. Portrait of Myself. New York: Simon and Schuster. Pickle Partners. First published 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Buryła, Sławomir. 2012. Topika Holocaustu. Wstępne rozpoznanie. Świat Tekstów. Rocznik Słupski 10: 131–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cadava, Eduardo. 2021. Paper Graveyards. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caruth, Cathy. 1996. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Hanna, and Claire Gorrara. 2012. Reframing War: Histories and Memories of the Second World War in the Photography of Julia Pirotte. Modern & Contemporary France 20: 453–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Didi-Huberman, George. 2008. Images in Spite of All. Four Photographs from Auschwitz. Translated by Shane B. Lillis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1955. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Translated by James Strachey. 24 vols. London: Hogarth Press, vol. 8, pp. 3–64. First published 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1939. Moses and Monotheism. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Translated by James Strachey. 24 vols. London: Hogarth Press, vol. 23, pp. 1–138. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, Jean. 1998. The World Wars through the Female Gaze. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, Jan T. 2007. Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, Margaret. 2012. Analogue. On Zoe Leonard and Tacita Dean. Critical Inquiry 38: 796–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koontz, Claudia. 1994. Between Memory and Oblivion: Concentration Camps in German Memory. In Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity. Edited by John Gillis. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koszowy, Marta. 2018. Fotografie pogromów: Julii Pirotte reportaż z Kielc. In Pogromy Żydów na ziemiach polskich w XIX i XX wieku. T. 1, Literatura i sztuka. Edited by Sławomir Buryła. Warsaw: Instytut Historii im. Tadeusza Manteuffla PAN, Instytut Historyczny Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Uniwersytet Warmińsko-Mazurski, Uniwersytet Wrocławski, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN, Warszawa, pp. 363–79. Available online: https://rcin.org.pl/dlibra/publication/165273?language=en (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Lewis, Emma. 2021. Photography, a Feminist History. London: Octopus Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Linfield, Susie. 2010. The Cruel Radiance. Photography and Political Violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mavor, Carol. 2012. Black and Blue. The Bruising Passion of Camera Lucida, La Jete, Sans Soleil, and Hiroshima mon Amour. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meiselas, Susan. 2012. Body on a Hillside. In Picturing Atrocity. Photography in Crisis. Edited by Jay Prosser, Geoffrey Batchen, Mick Gidley and Nancy K. Miller. London: Reaction Books, pp. 117–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey, Laura. 1975. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen 16: 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofer, Daniel, and Lenore Weitzman, eds. 1998. Women and the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Anthony, ed. 1992. Lee Miller’s War. Boston: Bullfinch Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, Peggy. 2012. Atrocity and Action: The Performative Force of Abu Ghraib Photographs. In Picturing Atrocity. Photography in Crisis. Edited by Jay Prosser, Geoffrey Batchen, Mick Gidley and Nancy K. Miller. London: Reaction Books, pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pirotte, Julia. 1946. Kielce – 1946, manuscript deposited at the archives of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw. [Google Scholar]

- Pirotte, Julia. 1994. Une photographe dans la Resistance. Charleroi: Imprimatex Beaumont. [Google Scholar]

- Pirotte, Julia. 2012. Faces and Hands. Photographs of Julia Pirotte from the Collection of the Jewish Historical Institute. Warsaw: Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, Jay. 2012. Introduction. In Picturing Atrocity. Photography in Crisis. Edited by Jay Prosser, Geoffrey Batchen, Mick Gidley and Nancy K. Miller. London: Reaction Books, pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Puchała-Rojek, Karolina. 2006. Ucieczka od piktorializmu. Rocznik Historii Sztuki 31: 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska, Joanna. 2023. Available online: http://www.rajkowska.com/we-live-day-by-day-hour-by-hour-minute-by-minute/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Rittner, Carol, and John K. Roth, eds. 1993. Different Voices: Women and the Holocaust. New York: Paragon House. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman, Lisa, and Eric Rosenberg, eds. 2006. Trauma and Visuality in Modernity. Hanover: University Press of New England. [Google Scholar]

- Scarry, Elaine. 1985. The Body in Pain. The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Kaja. 1996. The Threshold of the Visible World. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sobchack, Vivian. 1984. Inscribing ethical space: Ten propositions on death, representation, and documentary. Quarterly Review of Film Studies 9: 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2005. Lament of the Images. Aperture. Winter. Available online: https://issues.aperture.org/article/2005/4/4/lament-of-the-images (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2010. “Photographier la catastrophe” Traduit de l’anglais par Gérard Lenclud. Terrain. Anthropologie et Science Humaine 54: 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2017. Photography after Photography. Gender, Genre, History. Edited by Sarah Parsons. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Struk, Janina. 2008. Images of Women in Holocaust Photography. Feminist Review 88: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarska-Bakir, Joanna. 2018. Pod klątwą. Społeczny portret pogromu kieleckiego. Warszawa: Czarna Owca, vols. 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarska-Bakir, Joanna. 2019. Pogrom Cries—Essays on Polish-Jewish History, 1939–1946. Warsaw: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka, Marta. 2011. CAA. Reviews. Available online: http://www.caareviews.org/reviews/1638 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2001. Gender and Atrocity: Women in Holocaust Photographs. In Visual Culture and the Holocaust. Edited by Barbie Zelizer. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 247–60. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).