At an early meeting we attended at Indigo, Jytte and Nijah, two of its members, began debating what was more important for them, the “process” of crafting or the finished “product” of their work. The two women did not reach a definitive conclusion, highlighting an underlying question. It is the question of whether we recognise the attempt or the accomplishment, whether we recognise talent or participation. Is it enough for women to come together and make craftwork or are there certain aims that should be achieved along the way?

What became evident over the course of our research was that the project could not be uniformly understood as following a certain grand vision that was shared within the group. Instead, we found that the women involved in Indigo had different expectations surrounding the project. Similarly, their motivations for joining the weekly meetings varied. Some reasons were economically motivated, while some were social; some were personal, such as wanting to learn the Danish language better or wishing to develop a crafting skill, while others contained bigger ideas of what holds local communities together or how migrants could be ‘integrated’ into Danish society. The following sections offer a closer investigation of three modalities—1. being professional, 2. preserving material culture, and 3. practicing the social language of craft—that shaped the internal dynamic of the group, and explore how varying expectations were negotiated in practice.

3.1. Being Professional

At Indigo, creative expression was intertwined with initiatives to integrate migrant women into Danish society. A central aim was to provide a space for members to make handicrafts outside of their private homes and to develop their professional identities in Denmark. The integration project actively sought out opportunities for group members to collaborate with local design companies and supported them in applying for internships or relevant study programs. The image Hanna, the group’s founder, presented to us when talking about the group’s members, was that of women who had previously been trapped, their lives confined to the home:

[Many of them] have not been working so much—or maybe they worked a little and then their backs hurt, or arms hurt, and they could not work anymore. A few of them work now or go to school but not so much. It’s like the women just sat in their apartments and did not go out. It’s like they were forgotten, you know. Everybody had forgotten them. And some of them don’t speak Danish so much.

Evidently, from this description, Hanna saw the potential of Indigo in improving the lives of women, who in her view were neglected in Danish society. Her ideas were well-intentioned, although at times could be criticised for resembling Margalit’s descriptions of paternalism, whereby a person believes to be “speaking in the name of an individual’s true interest” (

Margalit 1996, p. 16). The core problem Margalit sees in this type of narrative is that it treats other people “as immature”, (

Margalit 1996, p. 16), which we read as a lack of recognition of their equal status. However, the founder’s intentions cannot accurately be described as dictating the social dynamic of the group. As is the case with other researched arts-related migration projects (e.g.,

Whyte 2017), the different motivations for joining Indigo reflected an underlying tension between the way official project objectives are framed and the experiences of participating members. While Indigo aimed to develop meaningful professional identities, expectations and approaches of the individual members did not necessarily align with these official representations (

Whyte 2017).

Nijah, an Iraqi member of the group, who regularly joined Indigo’s weekly meetings, welcomed the networking opportunities offered and was enthusiastic about the possibility of selling her handicrafts. Through her participation in the project, she developed an idea to create her own crafting business and was active in selling her work at craft fairs and online. Hanna generally supported such ambitions. She was a key initiator, setting up opportunities for the women to sell their work at local markets and connecting them with brands and design schools. However, there were occasions where the promoted idea of professionalisation clashed with the group member’s ambitions. The organiser described situations where she felt members prematurely requested money for their handicrafts instead of focusing on developing their craft:

They came in with their things that [they] made at home and said, ‘Sell this. I want money.’ And I said, ‘no, we can’t sell this. You have to develop your things before you sell them.’

While Hanna facilitated profit-making opportunities, at its core, the version of professionalism promoted by Indigo was one centred on developing a professional attitude and not necessarily securing material needs through one’s work. Drawing on

Fraser’s (

2003) work on the politics of recognition, this standpoint suggests a position of relative privilege, where the significance of economic discrepancies in society is potentially disregarded.

Other group members completely discarded the idea that women in the group could live off the sales of their handicrafts as unrealistic. Aisha, for example, a middle-aged woman who had migrated to Denmark from Punjab, India 30 years ago, was sceptical about craft-related careers. “You cannot survive with it”, she said when asked about the prospect of making money from her craftwork. Neither did she believe that anyone else in the group was making much money from their sales:

I don’t think [you can survive with it] (...) Maybe somebody is doing big projects. I don’t know who’s doing that [much] that they can survive with it. I don’t know.

Rather than Indigo representing a space for Aisha to develop her professional identity, the group was something she needed to schedule besides her full-time job as a schoolteacher. Due to her physical appearance, including her hijab, Aisha represented what the Danish women in the group seemed to have in mind when they spoke of ‘the women’ of the project. In fact, Aisha’s picture was on the business card of the project. She worked full-time and took a ‘hobbyist’ approach to the group sessions. Yet, through her migratory background and ethnicised and racialised identity in Denmark, Aisha inadvertently became the group’s ‘poster woman’.

Nijah was also in a state of regular employment, working as an Arabic teacher at a school in Copenhagen, where she also offered extracurricular classes in handcrafting. She was one of the women we met who saw business opportunities through Indigo. Other members expressed little aspiration to make money from their work. We found that the way members perceived their familial role also shaped women’s membership in the group. For example, for Aisha crafting was integral to her role as a grandmother:

So, I [ask myself] what kind of grandmother am I going to be? Somebody who does something for her grandchildren or not. So, I started thinking in this way. I want to be a nice grandma, which is making small projects for their kids.

Narratives of ‘empowerment’ through professionalisation were also complicated in Paula’s case, a US-American member who had recently migrated to Denmark because of her husband’s job. During our interview, Paula expressed finding herself at a crossroads in life and struggled, at times, to create meaning for herself in her new home in a small town north of Copenhagen. Rather than aiming to professionalise her skills, going to Indigo meant putting aside work-related stress and childcare responsibilities to do something for the sake of enjoyment.

It actually feels very empowering to have something that I feel is deserving of me saying, “It’s time for you, my husband, to take care of [the kids]”. Because I do a lot—the vast majority—of the childcare at home.

The various approaches that members took at Indigo reveal a tension in how crafting spaces are perceived and understood in a ‘middle-ground’ between the ‘public’ and the ‘private’. Although Indigo embodied a more traditional ‘domain’ for handcrafting, in which ‘local’ or ‘family networks’ are typically considered private, we found that the space facilitated meaningful encounters between group members and external parties (

Bal 2019;

Zabban 2020). In this context, we align with arguments against a strict division between the so-called public and domestic sector, instead recognising that activities related to domestic life, leisure, as well as paid work may all overlap in what we might call a ‘third space’ (

Zabban 2020). Handcrafting serves as a useful tool for understanding such a space which, using a textile metaphor, “is bound within its borders, but… can still extend infinitely far either upwards or downwards” (

Haehnel and Reichstein 2019, p. 145).

3.2. Preserving Material Cultures

Beyond passing on practical knowledge within the group’s meetings, Hanna had larger ambitions outside of Indigo. She wanted to see the work of group members shown in museums as a means of demonstrating to the general public that migrants are part of Danish society and, thus, Danish history and culture. Showcasing their handicrafts, she felt, was a way of recognising their cultural contribution. When asked why this pursuit was so important to her, she replied:

Maybe it’s because it’s a history and the women also have a history, and nobody listens to this history that they have. And they live in Denmark and are Danish people, you know. And nobody listens to them. So, I thought, why not museums where there is a history, you know? So, you see in museums that these people are also Danish. They also have a history we can put in museums.

Intertwined with collective imaginations of ‘the nation’, museums have a role in representing a national story and are part of constructing and preserving narratives of national identity (

Anderson 2016;

Wakefield 2017). It was because of this perceived Danish ‘authenticity’ that Hanna may have imagined museums to have the power to reinforce the identity of those who belong (

Anderson 2016;

Wakefield 2017). There are conflicting views, however, about the usefulness of working with migrants in state-legitimised sites of heritage (

Chayder 2019;

Wakefield 2017;

Whyte 2017).

Chayder (

2019) highlights the potential for museums to act as centres of learning and community engagement, finding that the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark acted as a useful hub to create networks for students with refugee experience. On the other hand,

Rodgers (

2017) argues that ideas of refugees and their art production can be superficial, and that museum displays of practices and interpretations of ‘refugee arts’ risk falling into stereotypes.

Wakefield (

2017), who studies artistic practices and cultural representation in the Gulf states, found that migrant workers often regarded as being culturally poor were “generally excluded from officially sanctioned discourses and cultural representations” (p. 100). It may be that because of the social, political, and economic currency that has developed around categories such as ‘refugee art’, the presence of those with refugee experience in museums has gained societal traction and has become important to organising figures, like Hanna.

Notably, for Hanna, working with museums was not only about preserving migrant histories but, importantly, their material culture. In our first conversation, Hanna shared a fear that crafting techniques would remain hidden and eventually forgotten if projects like Indigo did not intervene. The fear she expressed aligns with

Taylor’s (

1994) argument that in cases where a minority group’s ‘survival’ is threatened, they should be given special rights by the State to maintain their existence. For

Taylor (

1994), ‘survival’ is not about preventing the loss of life but the loss of a collective good, or resource, like a minority language. Notions of ‘survival’ may, however, rely on static understandings of culture, presenting those with refugee experience in a single story (

Rodgers 2017).

Rodgers (

2017) problematises the notion of ‘survival’ by highlighting the embodiment of political, ideological, and aesthetic complexities in the arts, suggesting that the nature of mobility is part of a process of evolvement. Similarly,

Lauser et al. (

2022) suggest that artistic expression can be charged with emotion and political meaning, which has the ability to transform artwork into something else entirely.

We found that the importance and relevance of preservation often depended on the socio-political climate in which members and their artwork were situated. In our last few weeks of fieldwork in June 2022, there was considerable momentum in drawing attention to Ukrainian culture within Indigo, and in Denmark in general. Indigo co-organised a Ukrainian arts festival in a neighbouring town and was working with recently arrived Ukrainians to create a Ukrainian arts exhibition. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine clearly created a sense of urgency to recognise Ukrainian culture and heritage in Denmark and abroad. Recent public attention to the Ukrainian crisis however suggests a transience in state-sanctioned and public forms of preservation as being shaped by current politics (

Ulz 2019). Furthermore, the positive public engagement with Ukrainian culture is markedly different to the reception that other migrant groups have received in Denmark, drawing attention to the different tensions that affect preservation efforts.

When we spoke to group members during our first research phase, in the summer of 2021, it was mainly Hanna who spoke of her wish to collaborate with museums. The other women we spoke to agreed, but rarely un-prompted voiced ambitions for exhibiting their work. This may have been circumstantial. During a global pandemic, where social gatherings were still restricted, ideas of showcasing craftwork in large public institutions perhaps appeared unrealistic. Perhaps the longer women participated in the group, the more they likened to the idea. Perhaps the arrival of new Ukrainian visitors to the group had sparked momentum for the initiative. Whatever the reason, one year later, some of the same women now overtly expressed wishes to exhibit their pieces in a joint refugee exhibit with Ukrainian craftswomen. There is much debate in the literature about how identity is negotiated in relation to the arts. In a Scottish study,

Netto (

2008) found that the arts produced by minority ethnic groups and associated with their ‘home’ culture served as a means of cultural recognition in a broader national context. Engagement in the arts, particularly those associated with minority ethnic communities, was part of a process of constructing and negotiating a collective ethnic identity (

Netto 2008). While creative expression associated with a ‘home culture’ can strengthen notions of ethnic identity, there are also instances where this can have the opposite effect.

Cusenza (

2019), for example, in a post-war Syrian context, found that recognising art as ‘culturally distinctive’ can undermine the individual talent of artists, posing the risk of producing essentialising discourses. Identifying refugee artists as ‘refugees’ before ‘artists’ has the potential to side-line their individual talent, because the category ‘refugee art’ itself becomes the key identifier (

Cusenza 2019). There is also a ‘burden of representation’ in the expectation that an artist with a refugee background represents the experiences of all currently arriving refugees (

Parzer 2021).

The findings from our research show that material culture is not a rigid artistic form that is inextricably linked to particular people. Rather it takes on different forms depending on the context in which it is created. As might be expected, we found that the women in the project sought to amplify the ethnic markers in craftworks intended for museums, or broadly speaking cultural frameworks. For example, the purpose of the Ukrainian festival was to celebrate craftworks made by Ukrainian women and showcase them next to the craftworks of other migrant women in Indigo. It was framed as a celebration of difference in a shared craft. “This is Turkish crochet pattern”, one of the women explained; “this is a Ukrainian doll” another said.

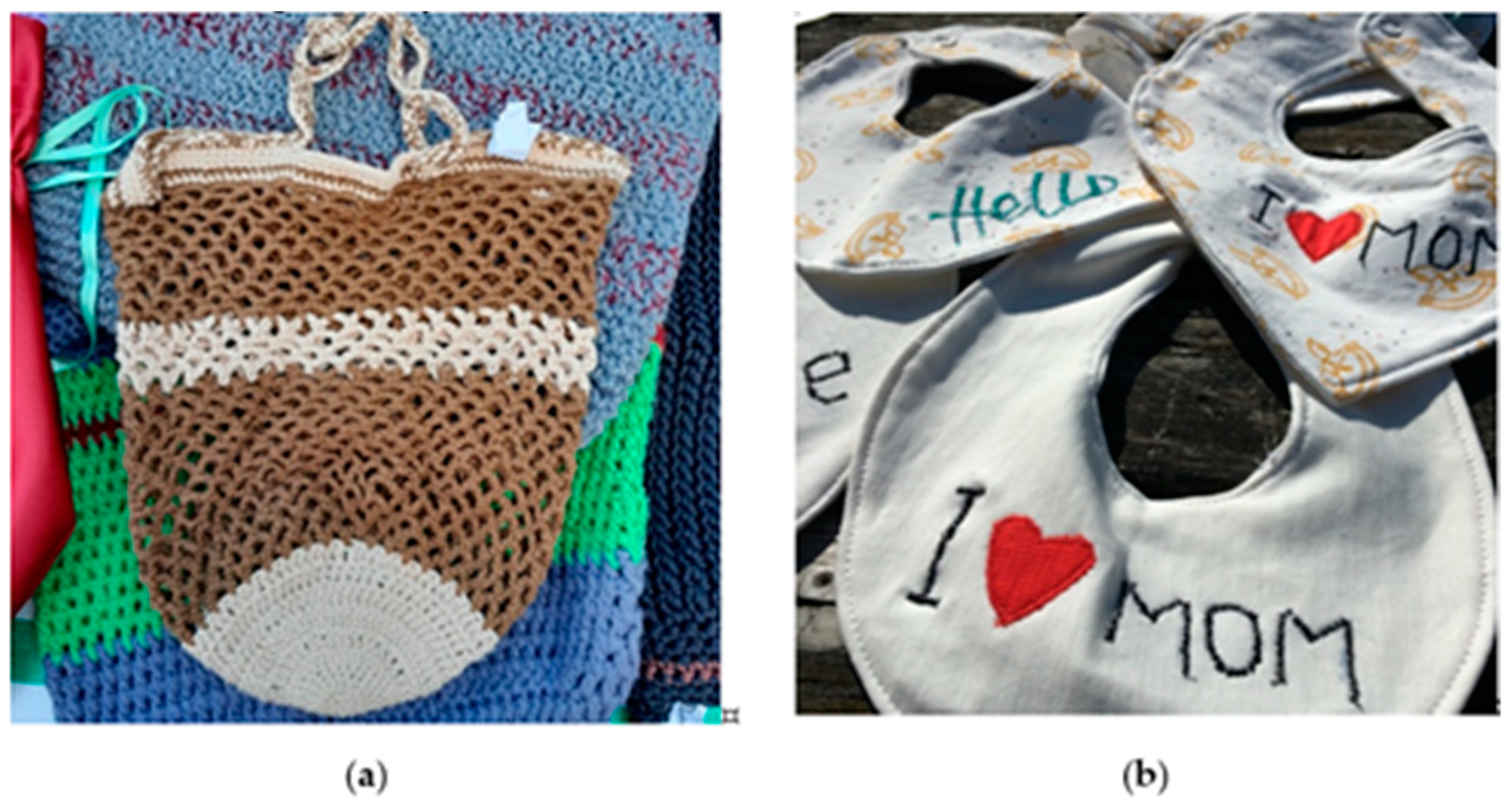

In other contexts, we found that the creative expressions of group members (see for example

Figure 1a,b) aimed to fulfil other criteria, such as the ability to appeal to a Danish market. This had consequences on the design, technique, and aesthetics of craftwork, whereby aspects of cultural identity were often ‘dampened down’. An emphasis on developing the professional identity of group members conflicted at times with how members envisaged their own work. For example, Hanna describes the importance of particular aesthetics and types of material in appealing to a Danish market:

A lot of the times when [group members] come with something, it’s acrylic yarn and it’s not Danish colours. We have to explain to them [that] Danish people like wool and cotton. And it has to be grey, beige.

After presenting the range of her work at a local craft fair, Indigo member Nijah quickly pointed to some of her more colourful pieces, suggesting that she preferred these. These tensions also manifested in instances where members such as Aisha brought back yarn from her country of origin that did not fit the ‘Danish tastes’ outlined by Hanna.

Rodgers (

2017) emphasises the significance of working with familiar materials and design aesthetics in her research with ‘refugee artisans’, finding participants often asserted that there was better thread in their hometown markets, sharing stories about “the failings of cotton thread” manufactured in their new country of residence (p. 31). Indigo members’ perceptions of quality were often marked by a reduced ‘market value’ in their preferred materials.

Some scholars have noted that it is not always the case that ‘the market’ is at odds with aspects of design, technique or aesthetics connected with cultural identities.

Riddering (

2018), for example, points out that art sales to tourists in San Juan la Laguna, Guatemala, do not rely on rigid notions of culture and do not compromise aspects of artists cultural identity. For artists in the area, new forms of artistic expression drawn from the art of their ancestors have become a unique selling point, and encounters at the art market have strengthened artists’ economic and cultural identities (

Riddering 2018). However, as pointed out by many authors (

Cusenza 2019;

Kasiyan 2019;

Parzer 2021;

Rodgers 2017;

Rotas 2004), the use of distinct categorisations to sell art, such as ‘refugee art’, ‘women’s art’ or ‘Black art’, pose the risk of becoming commodified and fetishised in harmful, self-serving ways.

In the face of certain market-oriented agendas in Indigo, members developed strategies of self-preservation, such as finding new ‘material middle-grounds’ and using Indigo for opportunities to network. For Aisha, learning new skills became an important factor in this adaption:

My preferences about [creating], it’s new thing for me to make.

Techniques connected to Aisha’s heritage were combined with a ‘Danish aesthetic’; likewise, ‘Danish materials’, such as cotton and wool, were adopted in combination with brighter colours. Nijah was still navigating processes of adaptation. So far, she said, Hanna played a significant role in connecting her with interested buyers, and it was through Hanna that Nijah could make her biggest profit. Nijah was, however, determined that events such as handicraft markets set up by Indigo could put her in touch with industry contacts and facilitate her transition to selling independently.

3.3. Practicing the Social Language of Craft

The French phrase

l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake), coined in the early 19th century, expresses the notion that art is intrinsically valuable and ought not serve any functional purpose (

Ullrich 2005). While the phrase can be celebrated for its liberation of artistic expression from social pressures and constraints, it also aligns with a tradition of devaluing craftworks which do serve a functional purpose. Thus, the works of ‘the artificer’, ‘the craftsperson’, ‘the handcrafter’, ‘the artisan’, or ‘the tradesperson’ all occupy an ambiguous position within a European context (

Haehnel and Reichstein 2019;

Troy 2006;

Ullrich 2005). It is within this context that anthropological approaches to art hold relevance. For example, the approach developed by

Gell (

1998) suggests that “from an anthropological point of view”, rather than relying on aesthetics when evaluating art, “anything whatsoever…including persons” could be an art object (p. 7). What about the practice of art itself then? The specific dynamic that develops in a group such as Indigo where women, even whilst pursuing different objectives, come together in a shared practice.

In his writing on art,

Boas (

1955) highlights the importance of practical knowledge (‘technical virtuosity’) which is acquired when a familiarity is formed between the craftsperson and the material object through repetitive artistic practice. The context of this case study adds a social element to the individual artistic endeavour. Learning handcrafting skills from one another and teaching others was an important element of Indigo’s regular meetings. The way of organising the weekly sessions involved Hanna designating one woman to lead the group in a crafting lesson. While Hanna praised members, she also mentioned the lack of initiative and confidence members displayed in leading such sessions. We observed teaching and learning taking place, but in a more informal way than what had perhaps been envisioned.

At first, it seemed like the women were each working on their own private projects with little reference to other group members. However, we then noticed the fluid way in which women gathered around each other to learn a specific stitch or pattern, and how they helped one another when they encountered craft-related issues. Aisha, for example, was regarded as a skilled craftswoman who frequently offered demonstrations to smaller learners’ circles gathered around her. These appeared more natural than the formal ‘classroom-style’ sessions which we had also witnessed and were characterised by a certain amount of disorder and awkwardness.

Other unstructured modes of communication and interaction also took place at the sessions. As Danish group member Jytte explained to us, “the technical language of doing craft” was a shared way of communicating within the group. Verbal elements, according to Jytte, could be one woman discussing a particular stitch with another woman or instructing her on how to do a certain crochet pattern. A reflection by

Taylor (

1994) on encounters across differences in ‘multicultural’ societies is fitting here. Ideally,

Taylor (

1994) argues, “we learn to move in a broader horizon” and the fusion of horizons with formerly unfamiliar cultures “operates through our developing new vocabularies of comparison, by means of which we can articulate these contrasts” (p. 67). In this sense, we can consider “the technical language of craft” as a mode to develop these new vocabularies and learn new and different skills.

For the women we spoke to, this did not only take place in the realm of verbal interactions. In fact, Jytte stressed that, sometimes through lack of a common language, non-verbal components of their meetings were often more important than spoken communication. Jytte found a kind of beauty in this form of communication: “It is more exciting”, she said, “with words you can only say, ‘I like your craftworks’, when you don’t speak the same language, you have to show this to someone visibly”. Thus, non-verbal communication, according to Jytte, could be a more expressive way to recognise what another person is doing.

Whyte (

2017) also emphasises the elements of sociality connected to artwork in his ethnographic fieldwork with asylum-seeking minors at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, where “using a friend’s idea or even letting him or her add something to your artwork could both reflect and develop social relations” (p. 691). Similarly, physical modes of communication at Indigo were an important part of how members made sense of one another and formed their own roles in the group.

These observations from our fieldwork highlight an interdependent relationship between knowledge and practice, relating to a common idea of practice theory, where practice is required to develop any kind of skill and cultivate it within a group (

Barnes 2001;

Turner 1994). In his ethnographically based research on craftworks,

Marchand (

2016) investigates problem solving within a framework of situated practice and cognition, suggesting the way that craftspeople interact with problems can be the core of learning and knowing. In line with

Marchand (

2016), we found making mistakes often facilitated interactions among members, where they ‘problem solved’ together. At Indigo, a knowledge–practice relationship also challenged prescribed forms of learning, such as the ‘classroom-style’ of teaching which held the expectation that group members would develop professional identities by taking on more ‘responsibility’ and demonstrating ‘leadership’.

A heightened public interest surrounding migration politics in Denmark also framed artistic practice at Indigo and centralised some members as particularly talented. For example, valued skills and esteemed talents were often associated with Turkish, Pakistani, and Iraqi nationalities. Organising figures such as Hanna described the “Turkish ladies… [as] so good, so good at handicrafts” and were in awe of their very fine crafting techniques:

And then when I see what they can do with their hands– and [their] handicraft. It’s like, wow, they… have a big talent.

Collectively recognising the work of these members foregrounded their position in the group, often (re)producing cultural stereotypes and ethnicised and racialised narratives. An us–them dichotomy became clear when group members reflected on one another’s work, with some members suggesting their own work was comparatively inferior. For example, this was apparent when US-American member Paula reflected:

I don’t think my work is worth as much as their work is,

as well as when Hanna suggested that:

They can do better handicraft than Danish women.

Perhaps the group’s commitment to value the work and skills of migrant women was an attempt to counter the increasing demonisation of migrants in public and political discourse in Denmark. However, through so doing, the national and migratory background, race, ethnic identity, and legal status of these members became emphasised, thus highlighting the potential for integration projects such as these to produce both helpful and unhelpful cultural labelling of minority groups.

While differences in the value attributed to creative expressions embodied broader societal positionings, for some members these labels were part of a process of deconstructing discriminatory views and enacting socio-political change. For Nijah, for example, crafting under the banner of Middle Eastern women was an important aspect of her identity formation in Danish society. In a group discussion, Nijah suggested that displaying skills connected to her ethnic identity was a part of undoing preconceived prejudices held in Danish society against women from the Middle East.

Indeed, we encountered different notions in the group about the potential of craftwork to inspire transformative processes. For Jytte, crafting was a “shared passion” that could transcend societal boundaries. She spoke mostly of bridging socio-economic differences, rather than perceived cultural differences. “Craft is a passion, like church is a passion”, she said, and, in her view, it did not matter how poor or rich you were to take part in them. She implied how skilfulness in craft was evident to anyone who shared this passion and, thus, took centre stage. In other words, she believed that at their meetings the technical language of craft could eclipse the classed language of society.

Hanna also noted how craftwork could empower women and bring together people of different backgrounds. But while Jytte was critical of what she called a lack of “coherence” in in Denmark caused by growing socio-economic differences, Hanna did not express a critique of classed society when she spoke of the presence of “rich” women at their meetings:

I always integrate all the people in the projects. I think that’s one of my main [goals]. When you have other women that are not like them, then something happens. Inspiration. You know, rich women also come and join the design place. (…) It’s like two worlds. (…) And then they connect and then something new comes up. They learn from each other. And some of the women, Danish women, that come in love to be there. I call them ‘Danish’ women, you know.

‘Rich Danish women’ to Hanna represented an opposite social group to the migrant women she worked with, speaking of “two worlds” coming together. She appeared particularly glad that wealthy Danish women had decided to be a part of the project, reflecting a degree of regard, maybe respect, that she had for them. At another point in our conversation, she ascribed “high people” status to them. Her statement that they, due to this status, could serve as inspiration for ‘the women’ at Indigo, reflects a different sentiment than Fraser’s idea of recognition as “an ideal reciprocal relation between subjects in which each sees the other as its equal” (

Fraser 2003, p. 10).

The above views share the notion that doing craft is about more than the craft work itself. An alternative perspective to these political notions surrounding craft was voiced to us by Aisha. She remarked upon craft enabling a connection between women in the project more as a matter of fact:

People get to know each other with this handicraft because we only have three things in common: the Danish language and the craftwork. And the third is that we are socially together.

Notably, the Danish language was not described as an issue, as it was by some organising figures in the group. When asked about whether she thought of the project as an ‘integration project’ Aisha replied:

[It] depends on what you put in integration. Is it people integrating into this society, or do you mean that they integrate in the handwork? (…) I don’t know, because I haven’t reflected that way, [on how] much they integrated it. Because always when we go there, it’s about handwork. It doesn’t matter that who is it, if they are Turkish or Pakistani or Danish or whoever it is.

Upon further reflection, Aisha later added that the project was a place where Danish women could learn from migrant women. She said that integration was taking place on the Danish side, that through interacting with the migrant women and recognising their talents, the Danish women were forced to rethink their prejudices. The above views share the notion that doing craft is about more than the craft work itself. Practices that emerged within the project pointed to larger societal structures in Denmark, whilst the group also clearly developed its own social dynamic. In this sense, Indigo both facilitated and framed interaction and social recognition.