Abstract

Historical studies on the subject of Central American design are scarce. This article attempts to fill the gap as well as to overcome the exclusive correlation of design with industrialization. It highlights the relationship in a space and time other than those studied customarily: in the present case, 18th-century Sonsonate, El Salvador. With this purpose, it analyzes crafts, based primarily on an unpublished census of 1787 housed in the Archivo Municipal de Sonsonate. Considering design as a practice inherent to human life, this paper argues that design was present in craft activity through the creation of products, becoming a key factor for survival in a colonial periphery and overcoming guild barriers. Research findings indicate the limitations of conceiving design in industrial societies as a construction of coloniality, positing also the need to advance a concept of design that addresses the cultural and historical realities of peripheral regions like Sonsonate.

1. Introduction

This article aims to contribute to filling the void of Central American participation in the global history of design from a decolonizing perspective. It argues that design, generally understood as the result of a process that includes aesthetics and functionality, and that responds to patterns of consumption that link it decisively to industry1, needs to be defined for the colonial peripheries. To this end, the starting point here is to understand design as a fundamental human act, manifested in all areas of its activity, present throughout the world at all times, and with an important social and cultural role (Scott 1982; Dilnot 1984a, 1984b; Bonsiepe 1999; Margolin 2005; Huppatz 2015). With this framework, it extrapolates design to the time of the study, linking it to craftsmanship as responsible for providing utilitarian objects (products) to society. Considering production processes as one of the gravitating themes in the history of Latin American design (Rodríguez 2013), this article focuses on the interior, considering that the majority of studies on crafts in colonial Latin America focused mainly on the main cities. For this purpose, it is largely based on a 1787 census of the population of Sonsonate, in present-day El Salvador and then a province of the Reino of Guatemala (the Kingdom of Guatemala, the modern Guatemala and Chiapas). This is a document that the author was fortunate enough to find during his archival research and which is published here for the first time. The census includes the complete list of artisans in the region, their sex, age, and calidad, the 18th century term for ethnic designation.

The history of Central American design before the industrial era is a subject still in need of investigation. The reason can be linked to Central America’s ascription to the referred peripheral condition. “Periphery” is a concept expounded in Latin America as early as 1946 and coined to distinguish countries outside the modern and developed center (Boer 1972; Hausberger 2018). Central America’s peripheral status dates back to the Spanish invasion of the region in 1524. Central America had little potential for precious metal mining, but there were better opportunities in terms of land and people to work it. The Spanish Crown then assigned the region a secondary economic role, based on participation in the foreign market with a leading product (first cocoa, then, in the 18th century, añil or índigo). There, the Atlantic traffic would pass by, and there would never be development projects that were not safe. (Wortman 1991; MacLeod [1973] 2007). The situation worsened in the 18th century, with the decline of Spanish industry and maritime power, as well as pirate harassment and the official closure of merchandise traffic through registry ships between Cadiz and Honduras. To this must be added the immense local difficulties for overland trade due to distances, bad roads, the rigors of the seasons, competition from foreign goods, and taxes that made prices higher, among others. Survival led to economic and social adjustments, which in regions such as Sonsonate were expressed in the development of handicraft activities.

The Kingdom of Guatemala’s productive processes were strongly conditioned by the region’s peripheral status. There, survival, a set of economic, social, and cultural actions aimed at overcoming the difficulties posed by the economic model (Castellón 2021, pp. 80–81), became indispensable. This circumstance was framed by an economic and social model of inequality that established an ethnic division in which Spaniards were above all others, followed by “Indios”, and, finally, enslaved Africans. But soon the model could no longer contain Latin America’s intense social mobility, and the situation in the peripheries was exacerbated. Especially in the interior of the Kingdom of Guatemala, the elites were made up of both Spaniards and mestizos pretending to be Spanish, followed by Ladinos (born of the union between Indios and Spaniards, and eventually even Mulattos, so that the Ladinos were also called Mulattos), and even African and Mulatto slaves who occupied positions of trust or performed tasks reserved for Spaniards. The Indians were at the bottom, but that did not prevent some of them from doing jobs that were foreseen to be done by Ladinos or Mulattos. This intersection of the social and the ethnic did not reduce inequalities, but rather increased them. The social impact of economic survival was reflected in the intensification of the exploitation of indigenous people through tribute, especially female labor. Indigenous people, in particular, had to add economic demands to the already difficult struggle for cultural and aesthetic survival. The social consequences of survival extended to the large population of Ladinos or Mulattos, and even to poor Spaniards, who, like the indigenous people, had to engage in craft activities or share their subsistence tasks with craft occupations. Not to mention the daily needs that forced many to make products for themselves (Margolin 2005). Relying on the outstanding studies of Lauer (1984) and Benítez (2009) on Latin American crafts, this article argues that handicrafts, as an activity equivalent to design and overcoming guild barriers, became the key to survival in the Central American colonial periphery.

The backwardness of industrial development in Latin America led to the definition of a “design of the periphery” (Bonsiepe 1999). The tendency to link design to industry has prevailed in the history of Latin American studies on the subject. While there are some notable contributions, such as Taborda and Wiedemann’s (2008) Latin American Graphic Design, Bonsiepe and Fernandez’s (2008) History of Design in Latin America and the Caribbean or Margolin’s World History of Design (Margolin 2016), the trend persists. This has reduced the participation in both exhibitions and in studies of countries that were “late entrants” to industrial development and where there is a noticeable lag in several areas, including design (Rodríguez 2013). Central American countries are among them, and their lagging position has placed them around 100th in the rankings of the Global Innovation Index 2022 (WIPO 2022, p. 19). While the history of Central American design already includes works such as those of Campos (2012), Morales (2019), Escobar (2020), and Paredes (2022), research emphasizes specific areas of design: its link to nationalism prevails and, above all, its study is persistently limited to the industrial era.

Exclusionist ideas of mechanized mass production and technological innovation—“industrial design” in its purest sense—are based on the “diffusionist model” in which modernism begins in Western Europe and diffuses outward (Huppatz 2015). For Fallan and Lees-Maffei, this discourse has been translated to the non-Western world as part of colonialism and is projected in historical narratives (Fallan and Lees-Maffei 2016). This gives rise to the idea that the periphery can overcome this condition if it seeks in its cultural history and technology (Fry et al. 2015; Osorio 2022) a vision that subscribes to decoloniality, a term coined by the critical production of the colonial matrix of power emanating from Western civilization, and exposed in Latin America by authors such as Quijano (1977, 2000), Dussel (1984), and Mignolo (2011). For its part, the need for a “Design History” that broadens the perspectives of design (Margolin 2016) has been emphasized by several authors in recent decades.2 At the end of the 20th century, the idea of resisting colonization from a history of design (Woodham 1995) was strengthened, and, since the advent of the new millennium, has led to new epistemologies that include the Global South. Authors such as Calvera (2005), Fallan and Lees-Maffei (2016), and Lara-Betancourt (2016) have pointed to the importance of national design histories. Ideas such as that of an autonomous design, emanating from Arturo Escobar (2016), can be seen as a recent Latin American contribution from the Global South (Fry 2017). Anna Calvera, a proponent of peripheral design, has drawn attention to many design historians who have worked or studied in countries considered peripheral, speaking naturally of this condition as a starting point for their research (Calvera 2005, p. 373).

Overall, it has been very difficult for Latin American designers to distance themselves from the perspective that links design and industry (Rodríguez 2013), despite the growing interest in the need to expand the focus of design beyond the industrial in both space and time. Decolonial writers such as Chakrabarty, for example, who proposes to approach the issue with a European “provincialization”, argue that modernity must be seen as inevitably challenging connections, as it is indispensable to make room for historically excluded narratives (Chakrabarty 2007, p. 43). Huppatz, for his part, has noted that although it is now widely recognized that the histories of modernism and colonialism are deeply intertwined, design history has so far failed to engage with this relationship (Huppatz 2010, p. 33).

A different perspective from the traditional conceptualization of design, such as the one proposed here, makes it necessary to move forward in overcoming the temporal and spatial barriers of design, taking into account the historical reality of the peripheral region, as well as formulating methodological and epistemological proposals that contribute to resizing design history in a global context. Authors such as Fry have addressed the issue of methodology for Australia suggesting a possible way forward with another kind of narrative, and another kind of voice (Fry 1988, 1989). But how do we proceed in the case of the Central American colonial periphery? Design is not alone in its concern with the study of history (Fallan 2010); design history can deal with a variety of topics, perspectives, or histories. This falls within the framework of what Margolin calls “design studies”, namely the field of research that examines how we make and use products in our everyday lives and how we have done so in the past (Margolin 2005, p. 319). This article argues that this approach must begin by freeing design from its alienation by industry and dimensioning its presence in all spheres of human activity as a fundamental practice (Bonsiepe 1999; Scott 1982) and generator of goods. This involves both social and economic factors, especially considering that the commodification of objects was imposed in colonial societies (Dilnot 1984b; Margolin 2009; Appadurai 1991; Kopytoff 1991; López 2008). It was Walker who unveiled a model of production–consumption that has figured at various moments in the history of design (Walker 1989). Fallan and Lees-Maffei, for their part, have sought to overcome the separation between industry and manufacturing in social dynamics (Fallan and Lees-Maffei 2016, p. 2). Both views express the correspondence between design and craftsmanship in the colonial past, especially considering that in Latin American history the production of goods was indifferent to its industrialization (Velasco 2016; Ariza and Andrade 2019; Rodríguez 2013). Today, for many peripheral countries, handicrafts have become a way of producing objects of use, reflecting a productive approach, a mode of use, and a powerful means of cultural identification (Rodríguez 2013, p. 113). The persistence of this reality in Central America is remarkable.

The lack of archives and infrastructure has been one of the main difficulties in conducting historical studies on design in Latin America (Lara-Betancourt 2016), and even more so in Central America. However, although the main support for this article is a primary source, in addition to the authors and works mentioned, studies that refer in some way to the history of design in Central America also form its framework. Particularly useful have been studies of Central American economic and social history, as well as works on culture, materiality, and craftsmanship. Works such as those by Wortman (1991), Santos Pérez (1999), and MacLeod ([1973] 2007), among others, not only offer a broad view of Central American history, but also refer to aspects of its space, technology, and culture. Remarkable works, mainly from Central American anthropology and archaeology, have also been of particular help to the subject presented here. In the field of handicrafts, Samayoa’s Los gremios de artesanos en la ciudad de Guatemala 1524–1821 (Craftsmen’s guilds in Guatemala City), or the works of Alonso (1980) and Esteras (1994) about silverware in the Captaincy General of Guatemala, are particularly valuable. Like the previous ones, studies on everyday life and Central American materiality (Castellón 2019), important areas related to design that have come to light in recent years, contribute to this study.

2. Design, Crafts, Production, and Artisans

In Latin America, craft has been relegated to the testimonial and decorative, far away from the productive and distributive channels of the market and its offer of consumable and highly intelligent objects (Velasco 2016, p. 2). Therefore, there is a need for proposals that give back to craft what has been taken from it, in a new way and form. “We are talking about design”, says Velasco, “the same design that, in its conception and development, in its productive and mercantile relationship”, as well as in itself an actor of contemporary consumption, has contributed to the banishment of craft. Anibal Quijano, for his part, explained the generalized presence of handicrafts in Latin America in 1977, when he stated that there, industrial production sought to eradicate the previous artisanal production of manufactures, which, far from disappearing, was expanded and modified, forming a new level within manufacturing production, articulated with the industrial level (Quijano 1977, p. 24). Some years later, Mirko Lauer discussed a production of objects that survives by virtue of capitalism’s inability to fully integrate the entire population into consumption, and its inability to industrially produce all the components of its processes (Lauer 1984, p. 19). A production that satisfies utilitarian, symbolic, and cultural needs, interacts with other spheres such as design, and works with criteria assimilated from design (Benítez 2009, pp. 7–9). Among the similarities found between design and craft, is the ability of artisans to identify the necessary transformation of the object, in the same way that design seeks new functions of the project and its strategies (Ariza and Andrade 2019, p. 201), with the how (the industrial production) being the only difference in relation to the past.

Recognizing the importance of craftsmanship in the production of goods in Latin America and its relationship to design, leads us to reflect on the correspondence between the two in the non-industrial past. In Rodriguez’s opinion, the link between industry and design makes, in principle, “the historical analysis of the relationship between design and crafts in peripheral countries unfortunate” (Rodríguez 2013, p. 113), which requires complex visions and interdisciplinary relationships on the part of design histories. For Rodríguez, the paths to be taken by these histories in Latin America cannot be detached from a global context, just as they require adopting a systemic perspective and observing design in its multiple relationships, taking into account national histories (both economic and social), and incorporating issues denied by traditional studies (Rodríguez 2013). At the basis of these relationships, is the primordial human condition and its sociability, what Norman has called “human centered design” (Norman 2013, p. 8). As early as 1984, Clive Dilnot noted that “the conditions underlying the emergence of a designed object or a particular type of design involve complex social relations” (Dilnot 1984a, p. 5). Some time later, Margolin (2009, p. 96) observed: “So far, researchers find greater interest in analyzing design methods than in trying to understand design’s part in the unfolding of social life.” But this social function of design, its most important characteristic as an activity present in all areas of human activity (Bonsiepe 1999) and a fundamental human act (Scott 1982), has been particularly transformed by the market.

This alienation of design due to the deepening of social inequalities and the weight of the market, was noticed by movements such as the Arts and Crafts in the 19th century and then exposed by Papanek ([1977] 2014, p. 22) who, in 1977, recalled the need to consider the economic issue in this metamorphosis of the social in design. For economists, the products of labor become commodities with the emergence of the social division of labor (within which, incidentally, craft specializations develop) and different forms of ownership of the means of production (López 2008, p. 194). Since these are “things that possess a particular kind of social potential” (Appadurai 1991, p. 23), commodities respond, in fact, to the deep social sense of the utilitarian and its categorization (Kopytoff 1991, p. 97). In commodified societies, these cultural classification systems reflect the structure and cultural resources of those societies, as Durkheim and Mauss (1963) pointed out.

This leads to the specific branches of production, and the way in which each of them has historically corresponded to the aforementioned classification, as well as to their signified value and the need to monopolize that value through power, responding to the needs of domination (Lauer 1984, p. 19). For Lauer, the coexistence of different pre-capitalist ways of producing objects, linked to different forms of social organization in history, leads inexorably to craft (Lauer 1984, p. 23). With the Spanish invasion in the 16th century, the conquistadors found in the Central American territory, especially where there were large demographic concentrations (such as in the Pacific region), a prolific agricultural production based on the division of labor. It was a production that was carried out in accordance with the coercive mechanisms of the state and that found expression both in the tribute of goods and fabrics, and in specialized artisanal production, conditioned by wage labor and alienated by merchants (Lauer 1984, p. 9). On this basis, the colonial model was established, which lasted until the beginning of the 19th century. In the creator–product–user triangle (Bürdek 2002, p. 146) typical of production for social purposes, the market changed the character of the vertices.

In his definition of products, Margolin distinguished between civic and state products, products for the market, and products made by people with their own means (Margolin 2005, p. 69). Years earlier, he had already defined products as tangible and intangible man-made objects, activities and services, and complex systems or environments that constitute the domain of the artificial. For Margolin, a major proponent of design as a human activity, these products constituted, definitively, the vast result of design activity. For Fallan, however, it was necessary to limit Margolin’s definition, since design denotes the conception and planning of these products; although he himself extended the results of this conception and planning to the vast output of the design activity in which we all participate (Fallan 2010). This perspective has been shared by design scholars such as Julier, for whom the term design denotes “the activities of planning and conception, but also the product of these processes, be it a drawing, a plan, or a manufactured object” (Julier 2010, p. 20). However, this view needs to be reconsidered in the context of the history of peripheral design.

The question of the planning has been key to defining the nature of design and, consequently, to identifying its presence in non-industrial times and spaces, such as the colonial periphery. Margolin had already noted that, in their life, products go through a life cycle that begins with their conception, continues with their acquisition and use, and ends with their disposal (Margolin 2005, p. 70). He had also pointed out that the process could be applied both to products that circulate in the market and to those that people make with their own means, using materials that are generally acquired in the market (Margolin 2005, p. 71). In 1987, Gert Selle (1987) warned of the capital error of all idealistic and positivist design theories in using the term “function” for the objects to be created, and never as something that can also come from the social requirements of the design through the project and the creator himself (Bürdek 2002, p. 252). Lees-Maffei, for her part, has pointed to the persistence of the tendency to privilege the acts of ideation and design in the production of objects, rather than the processes of manufacture, mediation, and consumption, leaving the origin of the goods undetermined in light of the widespread recognition of the global character of design (Lees-Maffei 2014). It is worth mentioning in passing that, although its presence can be perceived as diffuse, planned action was not absent in the artisanal practice of the past. In societies characterized by the elementariness, scarcity, and difficulty of access to useful objects, characteristic of the colonial periphery, planning resided in the distant past of objects that did not require further improvement, in unexplored foresight, or in processes of improvement based on the ancient method of trial and error. Not to mention that Braudel had already criticized the search for timeless and eternal truths (Wallerstein 2006, pp. 30–31) and that, as Appadurai states: “The social history of things and their cultural biography are not entirely separate matters” (Appadurai 1991, pp. 54–55). The colonial world was very different from ours today in terms of what was produced. Products were made with old tools; of proven functionality-sufficiency and, therefore, without indispensable changes; made to last, and, therefore, expensive. The products could not come from any other activity than craftsmanship, but this requires a definition of craftsmanship in all its dimensions. In the 1970s, Novelo (1979, p. 7) observed that to define craftsmanship [in Latin America], we speak of it as a result and not as a process. This makes it necessary to consider craft first and foremost as a form of social organization that implies a certain productive process, certain social relations of production, and a certain type of socioeconomic articulation considered as a whole (Lauer 1984, p. 31). Craftsmanship is a historical category, of particular validity, whose peculiarities are determined by the character of the relations of production that are proper to it (Becerril 1981), a definition that can be extended to design.

The close relationship between the artisan/designer and the production process even became the ideal of movements such as the Arts and Crafts, but this fact can be traced back much earlier, even further away from the industrial era and its territories. In the 18th century, an artisan was a manual worker, engaged in “mechanical occupations” (Real Academia Española de la Lengua 1726). In principle, he (the vast majority were men) had a public shop, but he also acquired this denomination by belonging to a guild that controlled the exercise of his profession. Moreover, the artisan was not independent; his activity was strongly influenced by his clientele, but especially in the interior of Kingdom of Guatemala by trade, specifically by the merchants of the capital Santiago de Guatemala (Santos Pérez 1999; Wortman 1991; MacLeod [1973] 2007). In provinces such as Sonsonate, economic and, consequently, social survival led to the expansion of handicraft activities that crossed occupational, ethnic, gender, and age boundaries, even to the point where people had to make products “by their own means,” as Margolin (2005, p. 71) puts it. Huppatz has claimed that the production of objects in the past involved artisans as well as non-artisans, the latter “people totally unrelated to design” (Huppatz 2015) who acted as “designers”. In other words, individuals who were not members of a guild and did not have a craft as their primary activity, but who were faced with the need to solve problems using essential craft techniques and tools. In this perspective, design, even with the variables mentioned above, was present in the activity of artisans and “non-artisans”. The “other designs” (Fallan 2010) and their “designers” possess their own forms of validation and the cultural determinants of the regions conditioned their particular way of generating material culture. This shows how, historically, artisans have made of their productions a resource for cultural survival and resistance in the face of hegemonies, even resorting to mechanisms of adaptation to prevailing economic and commercial systems that impose unfavorable production conditions (Benítez 2009, p. 12). The complex social relations to which Dilnot alludes also include the determining circumstances in which designers work, as well as the conditions that lead to the emergence of designers (Dilnot 1984b, p. 24). In the creator–product–user triangle, reformulated by industrial design as designer–product–user (Bürdek 2002, p. 146), artisans, whether they were members of a guild or not, occupy no other place than that of designers, creators of the goods necessary for life demanded by the market in order to survive, but also pressured by their own survival.

3. Sonsonate, the 1787 Census, and Economic Survival Strategies

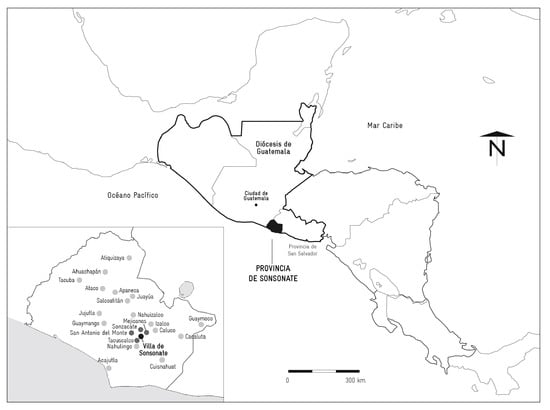

Sonsonate was a province of the Kingdom of Guatemala. As a jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Guatemala, it had 21 villages grouped into eight “curatos” (Juarros [1808] 1999, p. 25), one of which was the Villa de Sonsonate, the head of the province. Corresponding to this curato, were the villages of Santa Isabel Mejicanos, San Miguel Sonzacate, San Antonio del Monte, and San Francisco Tacuscalco (Figure 1). These villages were so integrated, and close to the Villa, that they were even considered its “barrios”, or neighborhoods. For its part, the Villa de Sonsonate had distributed its inhabitants among the barrios of El Centro or Santo Domingo, El Ángel, El Pilar, Veracruz, and San Francisco; another neighborhood, La Bolsa, close to Tacuscalco, appears only eventually in the documents.

Figure 1.

The Reino de Guatemala, Diocese of Guatemala, province of Sonsonate. Villa de Sonsonate and villages of the province. Own elaboration. Note: The darkest points correspond to the villages belonging to the Curato de Sonsonate, in the 18th century.

In November 1781, a census showed that the Villa de Sonsonate and its villages had 3290 inhabitants. But the population of the Sonsonate area had grown in just a few years (Table 1). This was a remarkable phenomenon in the Central American Pacific, where the demographic recovery from the time of the Spanish conquest was a reality. However, the protagonists of this recovery, especially in Sonsonate, were individuals of mixed calidades or ancestry. Children of Spaniards and Indios who fled their villages; some of them officially laborías, or forasteros (at first, indigenous servants of the Spaniards or Indios who had to pay tribute outside their villages, but over time, also Ladinos or free Mulattos); free Mulattos and their children, or among the other calidades (Castellón 2021, p. 10); constituted a population mass impossible to distinguish, according to the authorities, and indistinctly called ladinos and mulatos (Castellón 2019, p. 20). The census of 1781 reported 343 españoles (Spaniards), 2750 ladinos, and 188 indios in the Villa. There were also African or slave Mulattos, but in very small numbers: the large number of Ladinos or Mulattos made them unnecessary in terms of productivity. These individuals were found in practically all the settlements of the province, but mainly in the Villa de Sonsonate (Table 2).

Table 1.

Inhabitants of the Villa de Sonsonate and its surroundings.

Table 2.

Ethnic composition of the inhabitants of the Villa de Sonsonate and its surroundings (1797).

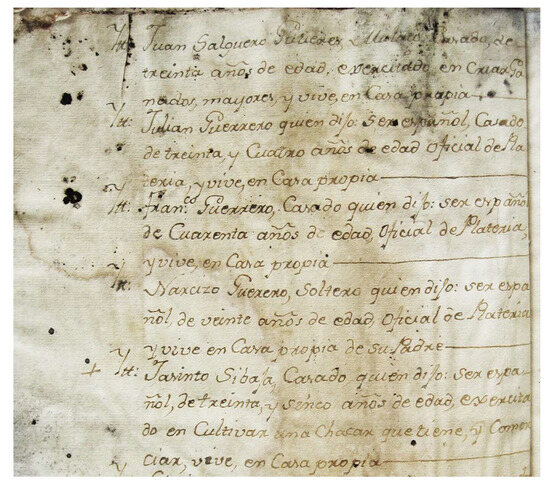

In 1787, a census of Sonsonate described the occupations of its inhabitants and nearby villages. Only male heads of households were included in the census (or in their absence, widows), and they were separated by neighborhood or barrio (Municipal Archives of Sonsonate, from here, AMSO. Caja 11, Expedientes 1 and 2, Figure 2). It is worth mentioning that although the information on the neighborhoods is complete, only the villages of Mejicanos, San Antonio, Sonzacate, and Tacuscalco could be located. Most of the inhabitants worked in agriculture, but about 5.5% were landowners and merchants, and 15% worked in the service sector. In total, 40.2% of inhabitants worked in recognized crafts trades. Outside the Villa, although the document does not list all the villages, 19.0% of the inhabitants were artisans. The information summarized in Table 3 (referring only to the Villa de Sonsonate) and Table 4 (referring to the villages outside the Villa) already revealed, in principle, two realities associated with the artisan activity in the hinterland of the kingdom: the rupture with the strict guild norms and the existence of rural circuits that also broke the traditional scheme of craftsmanship limited to the urban sphere.

Figure 2.

Extract from the 1787 census of Sonsonate. AMSO, Caja 11, Expedientes 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Villa de Sonsonate, 1787. Occupations of the inhabitants of its neighborhoods and the village of Tacuscalco (only artisan occupations).

Table 4.

Sonsonate, 1787. Occupations of inhabitants by village (craft occupations only).

Self-sufficiency was the answer to isolation in the Kingdom of Guatemala, especially in the interior. Commercial diversification became the “watchword for resistance and thriving in the changing and vulnerable world of colonial Central America” (Santos Pérez 1999, p. 464). The mercantile elite was committed to this goal in the early 18th century. On the one hand, it did so by opening channels for foreign trade, other than the official ones, by exporting and importing through Veracruz and Havana, and by smuggling. On the other hand, it engaged in intercolonial trade, mainly with Mexico, Havana, and Peru; and finally, the commercial elite organized internal trade, which allowed the flow of goods to and from the different provinces of the Kingdom of Guatemala (Santos Pérez 1999).

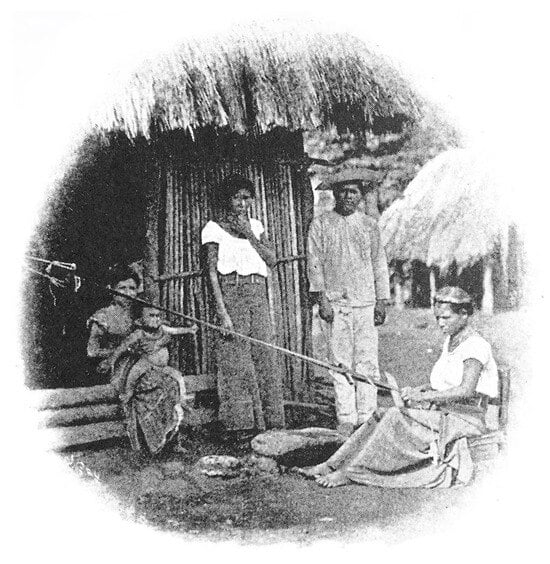

According to the logic of the market, the supply had to be guided by the demand. It should be noted that this is the modern equivalent of the idea of design for commercial mass production of finished products. For Santos Pérez, in Central America the first of the favorable factors, in this sense, was the aforementioned demographic recovery (Santos Pérez 1999, p. 476): more people were potential consumers of goods. This demand was activated not only by the commercialization of products through market channels, but above all by a special mechanism: the forced distribution of both goods (fabrics: ropa de Castilla or ropa de la China as well as iron tools, mainly) and raw materials for the production of ropa de la Tierra. In the first case, the merchants and their allies, the mayors, (the alcaldes mayores), received in exchange indigenous products at lower prices than in the market. In the second case, materials such as cotton were distributed to indigenous women to be transformed into threads and fabrics that they wove on backstrap looms (Figure 3). This was called repartimiento.

Figure 3.

A weaver in Izalco (Sonsonate) using a telar de cintura (backstrap loom). Documents show that this was the same technique used in the 18th century. Photograph: Karl Hartmann ([1899] 2001).

This dynamic not only suggests the early presence of the putting out system—the system of home-based labor associated with the industrial era—but also another, related to both the exploitation of labor and the coercion of labor, as well as the obligation to consume goods. The mechanism of the repartimiento activated the movement of goods on a large scale between the provinces of the kingdom. The repartimiento also led to a kind of regional specialization (González 2006) that further altered the original nature of regional patterns. The means of production, that initially determined the production of goods, were not based on exchange, inherent in the availability of local raw materials, but on trade, within the framework of colonial exploitation. The repartimiento was so crucial to the colonial economic system that it is said to have constituted, more than a corrupt practice, the most important form of commodity movement in the Kingdom of Guatemala (Patch 1994, pp. 78–80).

However, this mechanism was based on the tributo (tribute), which established that all indigenous people were obliged to tax part of their production to the authorities. In pre-Hispanic times, the model was based on the existence of the cacicazgo as a system of hierarchical organization. The peoples of a region had to pay tribute to the dominant lordships of the region; in the case of present-day El Salvador, these were local lordships. This mechanism was consolidated during the Mesoamerican Classic (300 to 900 AD) and Postclassic (900 to 1524 AD) periods in what is now Central America and was well suited to the extractive purposes of the Spanish, who had been accustomed to the concept of taxation for centuries (Hausberger 2018). Thus, tribute, along with trade (production and exchange), became the key components of colonial economic activity (Demarest 2004, p. 1). Its practice in the conquered territories was in line with the mercantilist vision of the Spanish Crown, which had perfected the model much earlier. The plunder and destruction of the conquest was followed by a greater division of labor, an emphasis on individual property, the appropriation of resources, and the general control of the economy by the colonizers. As far as possible, tribute supplied the crown coffers with money or goods, which were then converted into money, but it was trade that set the guidelines for its production, distribution, and consumption.

At the same time, other commercial survival mechanisms were incorporated into trade and the repartimiento in the Sonsonate region. The indigo boom that engulfed the neighboring province of San Salvador reached Sonsonate, but the region, less important in indigo production, developed its own dynamics. There was an active trade; an elite, though reduced, participated actively in it. There were at least five well-stocked stores, and nine pulperías (small shops). Despite its limited activity, Acajutla, close to the Villa, was the port with the best conditions to connect to the capital Santiago de Guatemala, with the maritime traffic of the Pacific, and there was a regular commercial traffic with that city. From the beginning of the 18th century, rosaries were exported from the Villa de Sonsonate to Peru via Acajutla (Archivo General de Centroamérica, A1 (3). Leg. 419. Exp. 4423). The villa and its surroundings were the scene of a particular dynamic of handicraft production.

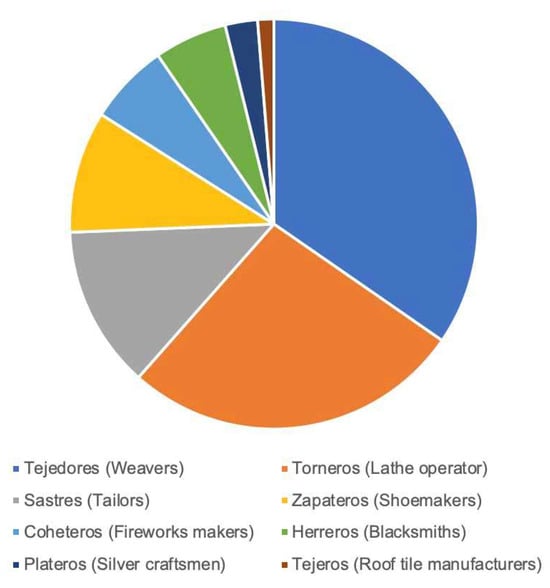

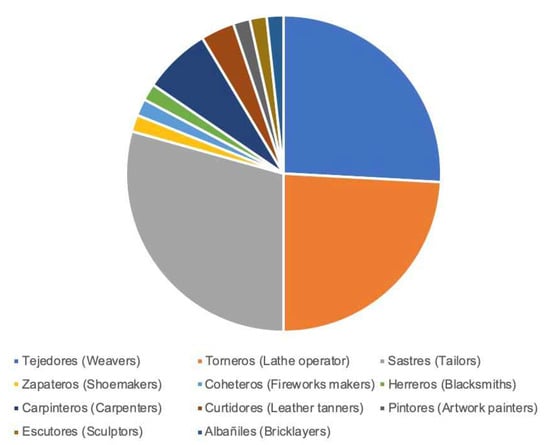

As Figure 4 and Figure 5 show, when the data for Villa de Sonsonate and the surrounding towns are combined, the occupations described in the 1787 census are headed by weaving. Once the Spanish tribute model was established after the Conquest, blankets (mantas) became one of the most sought-after items, and with the repartimiento of cotton in the 18th century, this form of exploitation of the traditional work of indigenous women became particularly notorious. To weave these blankets, the indigenous women used the ancestral technique of the backstrap loom. In this technique, a structure of several wooden rods holds the threads between which the warp is woven. The threads are tied, all together, at one end to a tree or beam and at the other end to a mecapal (a belt) attached to the weaver’s waist. The wooden rods define the width of the weave and allow the threads to be pressed with a special tool. The census lists only male artisans and excludes the traditional and substantial female artisan workforce. This is ironic, but understandable given the lack of interest at the time in listing trades that were considered exclusively indigenous. By the way, in 1730, the amount of blankets produced in Sonsonate generated 1486 pesos, (Solórzano 1985, p. 110), placing this product in second place after cacao and third after cash. However, several documents show that telar de pedales or telar de palanca (flying shuttle), used by the weavers described by the 1787 census (Figure 6), was, in fact, already installed in the Sonsonate region before the census.

Figure 4.

Professions of the craftsmen in Villa de Sonsonate. Based on information from the 1787 census.

Figure 5.

Professions of the craftsmen in the villages. Based on information from the 1787 census.

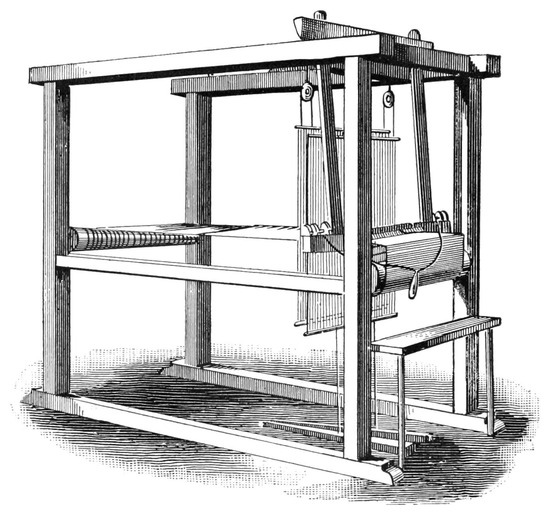

Figure 6.

The telar de palanca (flying shuttle). Image: The Popular Science Monthly Volume 39, 1891 (Youmas 1891).

It is unclear how production was handled by the flying shuttle technique (if, for example, there were obrajes in Sonsonate like those in Nueva España) and how they competed with the backstrap loom, in the repartimiento model. Everything indicates that production was controlled by merchants and authorities who owned and financed small or family workshops. The world cotton boom boosted textile activity in the Kingdom of Guatemala, leading to the expansion of flying shuttles into the urban and rural domestic sphere, something that also occurred in other parts of the American colonial space (Miño 1988, p. 300). But in Sonsonate, the expansion also suggests a reaction from the peripheral interior to its isolation and the high price of imported, mainly Guatemalan, textiles.

The large number of tailors indicates another important change. The great variety of fabrics de Castilla, de la China, and de la Tierra, that appear in the documents of the period, confirm both the important role of fabrics in the repartimiento and the wealth of some clients, but above all the probable existence of a clothing industry for commercialization and local consumption. This modality of repartimiento deserves further study.

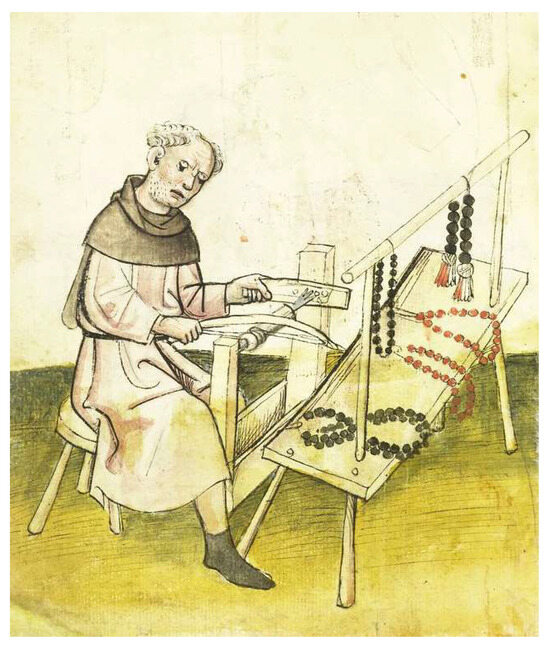

The other crafts highlighted in the census are torneros (lathe operators) and torneros de rosarios (rosaries lathe operators). The making of rosary beads brought the artisans of Sonsonate particularly close to the use of pre-industrial technologies. It was not specifically mentioned in the documents, but indications suggest that either the torno de arco (arc lathe) or the torno de pértiga (pole lathe) was used. This system has been used in Europe since at least the 11th century, and was introduced to New Spain (Mexico) in the 16th century. The system consisted of an elastic rod in the first case, or a bow in the second, attached by means of a string to a piece of wood that rotated with the reverse action produced by a pedal or the artisan’s hand (Figure 7). With the lathe machine, workers could have crafted rosaries that were shipped to Peru and documented in Sonsonate as far as the early 1700s. Information about this market, beyond its Christian importance, is unclear.

Figure 7.

The arc lathe. Image: Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen (1544).

Other occupations and techniques need more space than this article allows, but three are worth mentioning: shoemakers, blacksmiths, and silversmiths. The large number of shoemakers, as in the case of tailors, shows the existence of an important local elite, or even a shoe industry. The plentiful availability of cattle and leather guaranteed the vital and indispensable production of zurrones, leather bags essential for the transport of indigo on mules’ backs. Shoemakers in Sonsonate probably learned how to tan and work leather in addition to making shoes. The mastery of saddlery broadened their range of products to include the aforementioned zurrones, as well as girths and saddles for horses, belts, and bags, among others. For their part, blacksmiths played an indispensable role in the 18th century, and even more so for the mobilization of indigo in the region of Sonsonate and San Salvador. Blacksmiths made a range of things, from nails for buildings and boats, to knives and they also fixed and built parts for weapons, mills, stirrups, spurs, iron fittings, and types of tools. Guatemalan silverware experienced significant growth during the latter two-thirds of the 18th century. This growth is highlighted by the creation of both religious and non-religious pieces, including ciboria, processional crosses, fruit bowls, various vessels, and lamps (refer to Figure 8). The silver production in Guatemala and its provinces had unique features when compared to other Spanish American centers (Cruz Valdovinos 1979, p. 482). The production in San Salvador and Villa de Sonsonate was especially distinct (Alonso 1980).

Figure 8.

Lamp. Guatemala, 1757. Private collection. Photograph: Cristina Esteras (1994).

4. Artisans, Non-Artisans, Designers

After the conquest, the new productive relations, both in Ibero-America and particularly in Central America, were based on the similarity between local and foreign production methods, as well as on the European inability to expand its economic reach in the conquered territories (Lauer 1984, p. 11). But the conflict arose from the impossibility of balancing material and human capacities, social needs, and market interests. This had social and cultural repercussions, key aspects underwritten in the design (Scott 1982; Dilnot 1984b; Forty 1986; Fallan 2010).

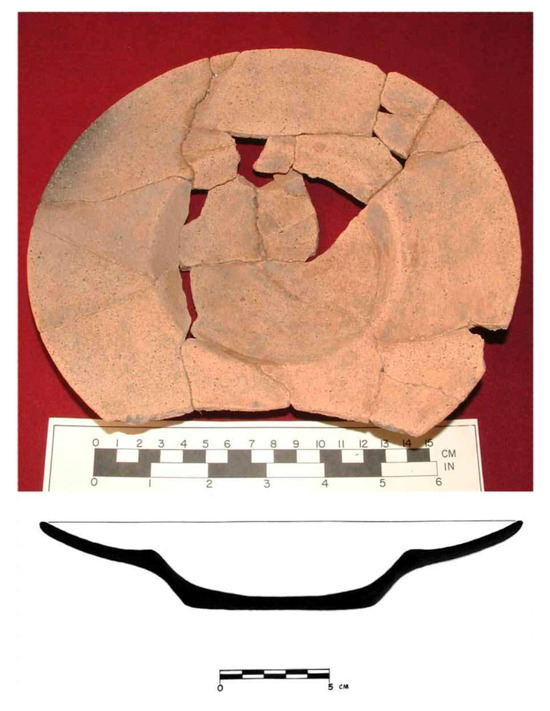

The first of these repercussions was both prompt and remarkable, relating to a fundamental trait of design: innovation (Margolin 2005, 2016). It involved not only the native exposure to new tools and methods but also the requirement to utilize and adjust the existing resources (material and human) to European customs in the territories conquered. An example of a plate made in Europe is called the “Pipil Italian Plate” by archaeologists. It was likely created by native potters in Ciudad Vieja, the earliest city in San Salvador from 1528 to 1545 (Card 2013). The plate is a mixture of Pipil (Central American nawua groups) and Italian styles, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

“Pipil Italian plate”. Photograph: Jeb J. Card. Drawing: Francisco Galdámez. Card (2013).

Clothing production is another example. Colonial tailors not only learned to copy European patterns but also adapted them to the tropics, following fashion trends. According to Bauer, there is enough evidence of this ability in rural cultures, which are mistakenly considered conservative and unchanging (Bauer 2001, p. 147). In 16th century Europe, dynamic economic conditions and increased competition made innovation a crucial ingredient for success (Conway 1987, p. 118). Innovation did not happen in the same way in peripheral regions. However, according to Conway, innovation does not necessarily mean developing new forms in its early stages, but rather incorporating trendy and striking qualities in both design and material handling. Although, in a competitive market, both the outstanding work of the Sonsonate silversmiths (Alonso 1980) and the creation of rosaries showed innovative ways to survive. Margolin labeled this “an act of permanent invention” (Margolin 2005, p. 319), which became essential in the periphery. Urgency led to limited resource solutions, skill acquisition, technology mastery, and transcending guild limitations. Innovation, which is considered the most remarkable moment in the process of developing technology, needs to be reconsidered based on its originality, creativity, and the writer’s determined and persistent effort (Basalla 2011, p. 14).

This brings us to another design-related issue: technology (Scott 1982; Margolin 2005; Norman 2013). If there was one activity that was affected by the European technological invasion of the early 16th century, it was craftsmanship. In some cases, the process was rapid and violent due to the circumstances of the conquest; in others, it was gradual, especially in the years of the founding of the first villages and towns, as exemplified by the Pipil Italian plate of San Salvador. Some handicrafts continued to be practiced by the indigenous population (especially pottery and basketry), but these activities were gradually influenced, on the one hand, by the need to produce new cultural objects or objects of reassigned economic value, and, on the other, by the direct and substitutive intervention of Spanish human and technical resources. It was an invasive process that had a direct impact on indigenous culture, displacing productive practices, technology and knowledge, and moving from the primary cause (Scott 1982) to the cultural affirmation of domination, reassigning qualities to design and once again affecting its original social purpose.

Only with the passage of time, in regions such as the Kingdom of Guatemala, and especially in its interior, did new machines, such as the lathe or the flying shuttle, make their way alongside new iron tools. Meanwhile, they shared space with traditional techniques, as production was still limited by the motive power and skill of the individual operator, as well as by the nature of a market where consumption patterns were rigid and traditional needs were preserved (Lauer 1984, p. 13). This made innovation less remarkable. Dynamic products were, for example, those related to clothing, but rather due to the influence of regional styles and fashions, the market, and elementariness. “Technology,” as Braudel said, ultimately has the very breadth of history and necessarily its slowness, its ambiguities (Braudel 1984, pp. 267–286).

Throughout this process, there was also planning, which is necessary to define the existence of design (Fallan 2010; Julier 2010). As noted above, planning may not have been so perceptible in the colonial periphery, as evidenced by the documentation in the Sonsonate case. It was limited by the persistence of the functionality of the few objects required by most consumers, the limited colonial market, the predominance of traditional craftsmanship, and the limited knowledge and practice of technical drawing. However, both the creative capacity, the technical mastery, the result of constant practice; the improvement and diversification of products, as demonstrated in Sonsonate, refer to a planned and methodical action, perhaps slower and less noticeable than expected, but present. Not to mention the fact that artisans such as the silversmiths of Sonsonate, in their work, probably required the preparation of sketches before making the pieces that made their work distinctive.

At this point, it is appropriate to specify how design was present in the activity of the producers of the objects. For this purpose, it is possible to distinguish three categories. The first is related to the assignment of craft activities to the guilds. In the original Spanish model, which lasted from the 11th and 13th centuries to the 16th century (Samayoa 1962), the artisan logic was expressed in the guilds, a form of organization that had three basic characteristics. First, guilds were recognized by the authorities, and their members (initially Spaniards) enjoyed the privilege of exclusively practicing a particular art or trade, and elected bylaws, mayors, and overseers. Second, the guilds had deep secular roots, expressed mainly in cofradías (brotherhoods). Third, they were subordinate to the Cabildo and linked to urban life (Samayoa 1962, p. 20). Indeed, the growth of cities and the number of artisans living in them was a widespread phenomenon in Latin America in the 18th century. In Mexico City, up to 50 percent of the population was engaged in artisanal activities (González 1982, p. 7). Something similar occurred in the city of Santiago de Guatemala, capital of the Kingdom of Guatemala, where 46.2% of individuals were artisans in 1794 (Sagastume 2008, p. 24).

It is very possible that the Sonsonate region had artisans officially recognized in the capital of Guatemala, but there is no record that the artisans listed in the Sonsonate census of 1787 were members of a guild, and it is almost certain that many were not. The absence of guilds in the documents consulted could be explained by the fact that the need to produce for economic and social subsistence outweighed the desire for artisans with guild status. The effects of this vision are clearly visible in the Sonsonate census. On the one hand, with the inclusion of all ethnic calidades in crafts (with exceptions such as indigenous participation in silversmithing), and on the other hand, with the expansion of artisan activity beyond the village to the surrounding towns.

Variations of the scheme also occurred in other regions of the Iberoamerican interior. This was due to local dynamics; in cities such as Salta and Jujuy (Argentina), for example, the artisan sectors constituted a small part of society (Raspi 2001, p. 163). But in general, in the 18th century, even in important cities such as Mexico (González 1982), there was a growing disregard for guild regulations. The phenomenon spread throughout Spanish America, especially in the second half of the 18th century, and in this context may have been the key to the survival of the peripheral regions. At that time, the same authorities of the Kingdom of Guatemala rejected the demands of the silversmiths and fireworks makers to include in their regulations the exclusion of persons who were not “pure Spaniards” in 1745 and 1794, respectively (Samayoa 1962, p. 35). But the reasons for this action went beyond simple autonomy. In the attempt to impose guild forms on the periphery, particular interests from the same city of Guatemala prevailed. It has been argued that mercantilist protectionism was intended to prevent the capital Guatemala from losing its dominance as the main commercial and industrial center, with its numerous workshops that supplied, or pretended to supply, the provinces (Samayoa 1954, 1962). But there were also powerful countervailing interests. It is possible to think that in Sonsonate the best consolidated workshops were financed by influential officials and merchants, especially from Guatemala, from where they exercised a strong monopoly. As lenders with extensive solvency, capitalist customers, and suppliers, they exercised considerable influence over production (Bernecker 2013, p. 24). The designer–producer–user system (Bonsiepe 1999) was inevitably affected. Except for the privileged who could pay for exclusive works, producers distanced themselves from the diverse needs of users. The subordination to commerce (whose emphasis was on the “safe sale”, for example through the repartimiento) reduced the spaces for innovation and creativity of the artisans.

It should be clear, then, that not belonging to a guild did not exempt artisans from a series of obligations that included the aforementioned means of production and capital, as well as a degree of specialization and certain organizational principles. The profession, whatever it was, distinguished levels of qualification and implied a certain creative capacity, but above all the mastery of technical skills and methodological work. The learning process took place in a workshop, starting as an apprentice. In the guild organization, this usually implied a contract. At the end, the apprentice had to demonstrate his technical ability in a master’s examination, which placed him in the category of laborante or official (González 2006, pp. 149–50). In Sonsonate, the process worked with some variations. The first was organic, since the family was an important organizational base, as evidenced by the census of 1787. In this system, which was more typical of the Ibero-American interior than of large cities like Mexico, the relationship father/teacher—official and son/apprentice—grandson prevailed. The second was apprenticeship, with variations as diverse as the existence of criados, apprentices educated “from an early age” in a mixture of apprenticeship-protection-servitude that could promise upward social mobility (this is the case of two Indio apprentices mentioned in the census in the village of Juayúa). Not belonging to a guild did not prevent one from learning and mastering tools and techniques (but not gaining the official title of “master”, which could only be conferred by a guild), nor from introducing variations and innovations in processes and products, as long as they were successful on the market.

However, the practice of crafts depended on the greater or lesser complexity of the art and its demand, so that occupations that were not particularly difficult to learn were practiced outside the guild (Samayoa 1962, p. 44). In this category, there were a variety of occupations that helped the main craft activities, such as leather makers who supplied the shoemakers, for example. This is the area where, far from the unrecognized artisans, the “non-artisans” or “semi-artisans” begin to appear. These were people who alternated their occupation with agricultural work, as the census shows in the example of “peasant and lathe operator” or “blacksmith and peasant” (Table 4), or who took part in the “putting out system”. This was, in fact, a differentiated modality in colonial times: that of artisans linked to subsistence agricultural activities, “whose production was destined for local and regional, utilitarian and ritual self-consumption, destinations that mark the limits of their exchange” (Lauer 1984, p. 15).

In regions such as New Spain, occupations that were less profitable or did not have direct access to the consumer market were subordinated to the strongest guilds or to merchants who acted as intermediaries (Angulo 1979, p. 157). This was due, on the one hand, to the fact that some occupations generated higher profits, such as weavers as opposed to indigenous spinners. On the other hand, it was also due to the fact that the most numerous occupations were the humblest (and, it is worth noting, the least well paid), and that they included more ladinos or mulatos, indigenous people and poor Spaniards, women, children, and the elderly. This peripheral reality was reflected both in the Kingdom of Guatemala (as Sonsonate’s census shows) and in other Iberoamerican regions, where there was a large number of “people of color, who had the lowest wages and among whom there was a smaller number of owners (of its means of production) in the 18th century” (Raspi 2001, p. 171). The same happened with the division of labor, as an expression of stereotypical and sexist exploitation (especially due to patriarchal power relations to the detriment of women), exacerbated by marginality. It is important to add that both underemployment and market-based employment limited the creative contribution of individuals, their mastery of technique, their planned action, and their social function, all aspects inherent in design.

In the same category should be included crafts of less commercial interest, such as basketry or ceramics, which were absent in the Sonsonate census but present in the “Indios” villages according to other documents. This segregation of trades that did not fit the economic model of profit maximation, but provided more accesible objects that were not obligatory purchases, made the indigenous candition more marginal. It also meant the displacement of most indigenous forms of production, keeping them in technological isolation and stripping them of their cultural burden. In addition, it marginalized indigenous producers (Salinas 1991, p. 172), limiting their spaces, as the 1787 census shows, to tasks such as weaving or making rosaries. This economic and cultural marginalization was transferred to design. This phenomenon continues to contradict the social, cultural, and functional nature of design and persists precisely in the gap that separates indigenous handicrafts from the industrial production of the consumer society.

The last category is that of those who engaged in activities related to crafts without being specialists. It included a wide range of specializations influenced by social and ethnic mobility, and of activities that made specialization dispensable. These were activities determined by subsistence, the urgency of daily life, and the need to prolong the life of objects. The documents show tools such as cepillos (planes), guillames, tongs, chisels, gouges, hammers, drills, saws, as well as sledgehammers, nails, and masons’ trowels (AGCA A1 (3). Leg. 459. Expediente 4609). Although these tools tended to belong to wealthy individuals, their abundant presence confirms that trades such as carpentry or masonry were frequently practiced on the haciendas, not necessarily in the hands of specialized craftsmen. The breadth of this category was facilitated by the fact that necessities, and their corresponding occupations and basic tools, did not change fundamentally until the 19th century either in Europe or in Iberoamerica. Some of these activities, honed by frequency, enabled some of the individuals in this category to become partially or fully engaged in less relevant or even more complicated craft activities, but it has not been possible to find concrete cases in Sonsonate. In any case, the excellence of these individuals derived from social recognition. This recognition was embodied in various codes, not only because of the frequency with which their services were required, but also because it made these individuals worthy of certain privileges, as was the case with accomplished artisans. Documents show how chocolate and bread, for example, were associated with the consumption of religious figures, high-ranking soldiers, officials, and especially skilled artisans (Castellón 2019, p. 204).

Finally, a fundamental characteristic of guild activity, but one that was key to the rooting of non-member artisans in peripheral colonial society. While the guilds in the capital went to the kingdom and demanded that artisans who worked beyond their authority be stopped, the non-members continued to organize themselves into cofradías. This form of organization was a mechanism of cultural penetration of the communities through Christian advocacy, but which had capital, were exempt from taxes by royal privilege, and were owners of money, cattle and even merchandise (Montes 1977, p. 22), estates and other properties. A documented example is the financing and participation of organized groups of carpenters, barbers, fireworks makers, and blacksmiths, among others, in the nearly 15 days that the celebration of the enthronement of King Charles III lasted in Sonsonate in 1761 (Castellón 2019, p. 294). For the guilds of the capital, it was no longer just a matter of the proliferation of unofficial shops, as opposed to the small number of shops of the official ones. Unofficial artisans had an increasing impact on the cultural, social, and political scene, for example by financing official festivals. Similarly, another variety of mechanisms can be cited that guaranteed the social rooting of non-guild artisans in the peripheral society, as marginal as it was permissive: servitude, alliances, and marriages, among others (Castellón 2019, p. 254).

By the end of the colonial era, “the promising dawn—or the harbinger of the storm—of capitalist production (depending on whether one was a beneficiary or a victim of the system) and the ‘consumer revolution’ in northwestern Europe were already on the horizon” (Bauer 2001, p. 158) and provoked changes in peripheral handicrafts. The Bourbon “free market” introduced in 1778 led to greater availability of foreign manufactures at lower prices, which significantly affected the Kingdom of Guatemala. In this context, the Spanish “Royal factories” came into force, which changed the organization of artisanal work and began to mutate it towards industrial forms of production, even mechanized, but which failed to develop the Central American proto-industry of the end of the colonial era. The side effects of the new ideas were also detrimental to the craftsmanship of the Kingdom of Guatemala. In the particular case of silverware, in 1795 the Enlightened ideas were gradually imposed from the capital Santiago de Guatemala to provinces like Sonsonate, and with them the neoclassical aesthetic doctrine. As creativity in silverware declined, so did artisanal activity. The decline was slow but steep. The crisis worsened at the beginning of the 19th century with European conflicts and the Napoleonic occupation of Spain, independence movements, and local crises such as plagues and droughts.

5. Conclusions

Latin American decoloniality requires an understanding of the historical and material production specificities of the periphery. When isolation was imposed on the Kingdom of Guatemala, Sonsonatecan society had to deal with the effects of the economic survival strategies of the local elite. Design, under the responsibility of those who produced the objects, the artisans, was not only a key for economic purposes: it allowed the social, technological, and cultural consequences to be faced. Artisans, whether they belonged to a guild or not, came to represent more than 40% of the inhabitants of the Villa de Sonsonate, as well as 19% in nearby villages (quite striking percentages in a Central American regional context). Survival developed a particular dynamic in the peripheral hinterland, where artisanal activity went beyond the guilds, diversifying and adopting a variety of modalities among social or ethnic groups of all ages and genders.

Of course, it is not possible to establish a correspondence between the parameters of modern design and those of the past. As is the case today, design was conditioned by the powerful pressures of the economy, to which it subordinated its social and cultural character. However, the example of Sonsonate allows us to point out some characteristics. More than a massive and diversified mass production, unbeatable basic objects suitable for elementariness, with a maximum time of use and an obsolescence that transcends generations. More than advanced technology, traditional craftsmanship with an emphasis on utility. More than advertising, prestige, and commercial success. More than a preconceived end product and the search for innovation, a product that has been tested, accepted, and perfected over time. Factors such as the large female labor force exploited by the repartimiento, the control of the merchants over raw materials and the commercialization of products, the growing economic dependence of the artisans on the merchants, and the distance between the artisans and the large number of inhabitants with limited access, also characterized artisanal production in the Kingdom of Guatemala and demonstrated the impracticability of being tied to a guild. But if one wants to insist on the link between design and industry, at least two things show that Central America was on the way to becoming a proto-Iberoamerican industry, as Miño (1999) has called it. First, the existence of a productive circuit integrated by the villages surrounding Villa de Sonsonate. Secondly, the development of the textile and wood industries. But not only was the Spanish Crown not interested in the development of industrial production in its possessions, on the contrary, it took measures to slow it down in order to protect the Spanish market.

The need to survive under colonial conditions also led to activities that did not require a high degree of specialization, but rather the mastery of basic tools and techniques to supplement daily activities, prolong the life of objects, or, in short, to survive. The additional and valuable merit of design in the periphery was that it made it possible for creators to cope with economic pressure, regardless of how products were made. This would confirm that the design criterion is not what is created or designed as a product of a process, but what is functional (Margolin 2005, p. 64). On the periphery, innovation and creativity, and even planned action, were not necessarily expressed in new technologies or products, but in the ability to make the best use of resources (material, technological, human) in order to survive.

Unfortunately, the ingenuity of these spontaneous “problem solvers,” as well as that of the true creators, the “inventors” of solutions, the “non-designers,” the individuals whose intrepid or unusual ideas rescued some unforeseen situation out of the urgency of survival, was not officially recorded. As John Heskett noted in 1987, anonymity seems to have been, and still is, “part of the burden designers must bear for their role in democratic utilitarian design” (Heskett 1987, p. 116). The study of the artisans and non-craftsmen who had to cope with existence in the peripheral Kingdom of Guatemala deserves attention for its potential contribution not only to Central American design, its history and identity, but also to “broadening design perspectives”, or, in Margolin’s (2015) words, in constructing a global design history.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the results reported can be consulted in the Municipal Archives of Sonsonate of the Salvadoran Academy of History. https://www.historia.edu.sv/ (accessed on 30 August 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Debates about the definition of design continue. The definition presented here has been constructed by trying to bring together the most common ones, including those of Sparke (1987), Bonsiepe (1999), Bürdek (2002), Taborda and Wiedemann (2008), Fallan (2010), Norman (2013). |

| 2 | These include Forty (1986), Dilnot (1984a, 1984b), Fry (1988), Walker (1989), Buchanan (1992), Fry et al. (2015), Margolin (2005, 2016), Lees-Maffei (2014), Fallan and Lees-Maffei (2016), Julier (2010), Fallan (2010), among others. |

References

Archival Sources

Archivo General de Centroamérica (AGCA) A1 (3). Leg. 419. Expediente 4423. Mortual del intestado don Lázaro Grijalba, 1706.Archivo Municipal de Sonsonate (AMSO). Caja 11. Expedientes 1 y 2. Padrón de los habitantes de la provincia con nombres, edades y oficios, 1785.Secondary Sources

- Alonso, Josefina. 1980. El Arte de la platería en la Capitanía General de Guatemala. Guatemala: Editorial Universitaria. [Google Scholar]

- Angulo, Jorge. 1979. Los gremios de artesanos y el régimen de castas. Anuario del Centro de Investigaciones Históricas II: 148–59. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1991. La Vida Social de las Cosas. Mexico: Grijalbo. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, Verónica, and Mar Itzel Andrade. 2019. La relación artesanía y diseño. Estudios desde el norte de México. Cuaderno 90: 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Basalla, George. 2011. La Evolución de la Tecnología. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Arnold. 2001. Goods, Power, History: Latin America’s Material Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becerril, Rodolfo. 1981. La encrucijada de las artesanias y su comercialización externa. In Comercio y Desarrollo. México City: FONART, pp. 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez, Surnai. 2009. La artesanía Latinoamericana Como Factor de Desarrollo Económico, Social y Cultural: A la luz de los Nuevos Conceptos de Cultura y Desarrollo. La Habana: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Bernecker, Walther. 2013. Manufacturas y artesanos en México a finales de la época colonial y a principios de la independencia. In Estudios sobre la Historia Económica de México Desde la época de la Independencia Hasta la Primera Globalización. Edited by Sandra Kuntz and Reinhard Liehr. Madrid: Iberoamericana, pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, Cees den. 1972. Centro y periferia: La Fundación Teórica en Prebisch. Boletín de Estudios Latinoamericanos 12: 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsiepe, Gui. 1999. Del objeto a la Interfase. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Infinito. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsiepe, Gui, and Silvia Fernandez. 2008. Historia del diseño en América Latina y el Caribe. Sao Paulo: Bûche. [Google Scholar]

- Braudel, Fernand. 1984. Civilización Material, Economía y Capitalismo. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, Richard. 1992. Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues 8: 5–21. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511637 (accessed on 21 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bürdek, Bernhard. 2002. Diseño: Historia, Teoría y Práctica del Diseño Industrial. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili. [Google Scholar]

- Calvera, Anna. 2005. Local, Regional, National, Global and Feedback: Several Issues to Be Faced with Constructing Regional Narratives. Journal of Design History 18: 371–83. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3527242 (accessed on 14 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Campos, Carmen. 2012. Diseño en El Salvador, estudio de caso una aproximación a las competencias. Actas de Diseño 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, Jeb. 2013. Italianate Pipil Potters: Mesoamerican Transformation of Renaissance Material Culture in Early Spanish Colonial San Salvador. In The Archaeology of Hybrid Material Culture. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, pp. 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellón, José. 2019. Secretos de familia: La familia y su Movilidad en El Salvador Colonial: Siglo XVIII. San Salvador: Editorial de la Universidad Centroamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Castellón, José. 2021. Estrategias de supervivencia y emociones. Unión informal y matrimonio en el Pacífico colonial centroamericano. Cuadernos Inter.c.a.mbio sobre Centroamérica y el Caribe 18: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2007. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, Hazel, ed. 1987. Design History: A Student’s Handbook. London: Unwin Hyman. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Valdovinos, José Manuel. 1979. Plata y plateros en Santa María de Viana. Príncipe de Viana 40: 469–95. [Google Scholar]

- Demarest, Arthur. 2004. Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of Rainforest Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dilnot, Clive. 1984a. The State of Design History, Part I: Mapping the Field. Design Issues 1: 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilnot, Clive. 1984b. The State of Design History, Part II: Problems and Possibilities. Design Issues 1: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Emile, and Marcel Mauss. 1963. Primitive Classification. London: Cohen and West. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique. 1984. Filosofía de la Producción. Buenos Aires: Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO). [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, Arturo. 2016. Autonomía y Diseño: La Realización de lo Comunal. Popayán: Universidad del Cauca. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, Gloria. 2020. Memoria del Evento “Historia y Actualidad del Diseño Industrial Latinoamericano”. Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar. [Google Scholar]

- Esteras, Cristina. 1994. La platería en el Reino de Guatemala: Siglos XVI–XIX. Guatemala: Fundación Albergue Hermano Pedro. [Google Scholar]

- Fallan, Kjetil. 2010. Design History: Understanding Theory and Method. Oxford and New York: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Fallan, Kjetil, and Grace Lees-Maffei. 2016. Designing Worlds: National Design Histories in an Age of Globalization. Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Forty, Adrian. 1986. Objects of Desire. Objects and Society Since 1750. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, Tony. 1988. Design History Australia: A Source Text in Methods and Resources. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger and the Power Institute of Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, Tony. 1989. A Geography of Power: Design History and Marginality. Design Issues 6: 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, Tony. 2017. Design for/by “The Global South”. Design Philosophy Papers 15: 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, Tony, Clive Dilnot, and Susan Stewart. 2015. Design and the Question of History. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- González, Jorge. 1982. La producción industrial de la ciudad de México a finales del siglo XVIII. Ph.D. dissertation, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México, Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- González, Jorge. 2006. La Fuente de Alcabalas y el Comercio Interno Colonial Guatemalteco: El caso del Corregimiento de Quezaltenango, 1763–1821. Barcelona: AFEHC. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, Karl. 2001. Reconocimiento etnográfico de los aztecas de El Salvador. Mesoamérica 41: 146–91. First published 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Hausberger, Bernd. 2018. Historia Mínima de la Globalización Temprana. Mexico: El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen. 1544. Available online: https://www.nuernberger-hausbuecher.de (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Heskett, John. 1987. Industrial Design. In Design History: A Student’s Handbook. Edited by Hazel Conway. London: Unwin Hyman, pp. 110–32. [Google Scholar]

- Huppatz, Daniel. 2010. Jean Prouvé’s Maison Tropicale: The Poetics of the Colonial Object. Design Issues 26: 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppatz, Daniel. 2015. Globalizing Design History and Global Design History. Journal of Design History 28: 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarros, Domingo. 1999. Compendio de la Historia de la Ciudad de Guatemala. Guatemala: Biblioteca Goathemala. First published 1808. [Google Scholar]

- Julier, Guy. 2010. La Cultura del Diseño. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili. [Google Scholar]

- Kopytoff, Igor. 1991. La biografía cultural de las cosas: La mercantilización como proceso. In La Vida Social de las Cosas. Edited by Arjun Appadurai. Mexico: Grijalbo, pp. 89–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Betancourt, Patricia. 2016. The Quest for Modernity: A Global/National Approach to a History of Design in Latin America. In Designing Worlds: National Design Histories in an Age of Globalization. Edited by Kjetil Fallan and Grace Lees-Maffei. New York and Oslo: Berghahn Books, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer, Mirko. 1984. La Producción Artesanal en América Latina. Lima: Report to the International Development Research Center (IDRC). [Google Scholar]

- Lees-Maffei, Grace. 2014. ‘Made’ in England? The Mediation of Alessi S.P.A. In Made in Italy: Rethinking a Century of Italian Design. Edited by Grace Lees-Maffei and Kjetil Fallan. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 287–303. [Google Scholar]

- López, Angélica. 2008. De la creación a su consumo: Objetos y mercancías. Athenea Digital 14: 191–98. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, Murdo. 2007. Spanish Central America: A Socioeconomic History, 1520–1720. Austin: University of Texas Press. First published 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, Victor. 2005. Las Políticas de lo Artificial. Mexico: Editorial Designio. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, Victor. 2009. Design in History. Design Issues 25: 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolin, Victor. 2015. World History of Design. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, Victor. 2016. A World History of Design. In The Routledge Companion to Design Studies. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miño, Manuel. 1988. La política textil en México y Perú en la época colonial. Nuevas consideraciones. Historia Mexicana 38: 283–321. [Google Scholar]

- Miño, Manuel. 1999. ¿Protoindustria Colonial? In La Industria Textil en México. Edited by Aurora Gómez-Galvarriato. Mexico: El Colegio de México, pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, Santiago. 1977. Etnohistoria de El Salvador: El Guachival Centroamericano. San Salvador: Dirección de Publicaciones, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, Hernán. 2019. La institucionalización del Diseño Industrial en Guatemala durante la década de los años 80. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Palermo, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, Don. 2013. The Design of Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Novelo, Victoria. 1979. Las Artesanías en Portugal. Mexico: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Osorio, Alejandra. 2022. Why Chuño Matters: Rethinking the History of Technology in Latin America. Technology and Culture 63: 808–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanek, Victor. 2014. Diseñar Para el Mundo Real. Barcelona: El Tinter. First published 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, Alejandra. 2022. Apuntes sobre la historia de la moda en Honduras. In Honduras Sabor de Sueño: Su Legado Cultural. Sevilla: E.R.A., Edited by Carmen Cruz. pp. 133–50. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10433/13554 (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Patch, Robert. 1994. Imperial politics and local economy in Colonial Central America, 1670–1770. Past and Present 143: 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, Aníbal. 1977. Imperialismo y Marginalidad en América Latina. Lima: Mosca Azul. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Aníbal. 2000. Colonialidad del Poder: Cultura y conocimiento en América Latina. In Capitalismo y geopolítica del conocimiento: El eurocentrismo y la filosofía de la liberación en el debate intelectual contemporáneo. Edited by Walter Mignolo. Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Signo, pp. 117–31. [Google Scholar]

- Raspi, Emma. 2001. El mundo artesanal de dos ciudades del norte Argentino. Salta y Jujuy, primera mitad del siglo XIX. Anuario de Estudios Americanos 58: 161–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]