The Shape of International Art Purchasing—The Shape of Things to Come

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Discussion

3.1. Digital Corporate Mutualisation:

How DAOs and NFTs Facilitate Business and International Art Acquisition

“Almost forty years ago, cryptographer David Chaum proposed a blockchain-like protocol in his 1982 dissertation entitled Computer Systems Established, Maintained, and Trusted by Mutually Suspicious Groups. This work formed the bedrock of the current blockchain technology, but the notion of blockchain as a form of cryptography traces back to the 1970s”.

“DAOs are a vehicle which will drive idea in music, fintech and healthcare. Tennessee is winning whenever DAOs are established in our state that help transform industries”, noted TN representative Jason Powell. “I proposed the DAO legislation because I believe in democratizing the ability to participate in various ventures previously not open to most people. I am hoping that more high-impact legislation will be passed as web3 initiatives evolve and transform the business landscape”.

“DAOs are made up of humans and therefore require manual actions from users to function, such as needing users to conduct votes, deploy code, and debate proposals. The use of autonomous in the term DAO stems from the idea of hardcoding specific function of the DAOs as immutable smart contracts. However, humans still need to interact (provide inputs) with the smart contracts (code) for them to execute actions (outputs)”.

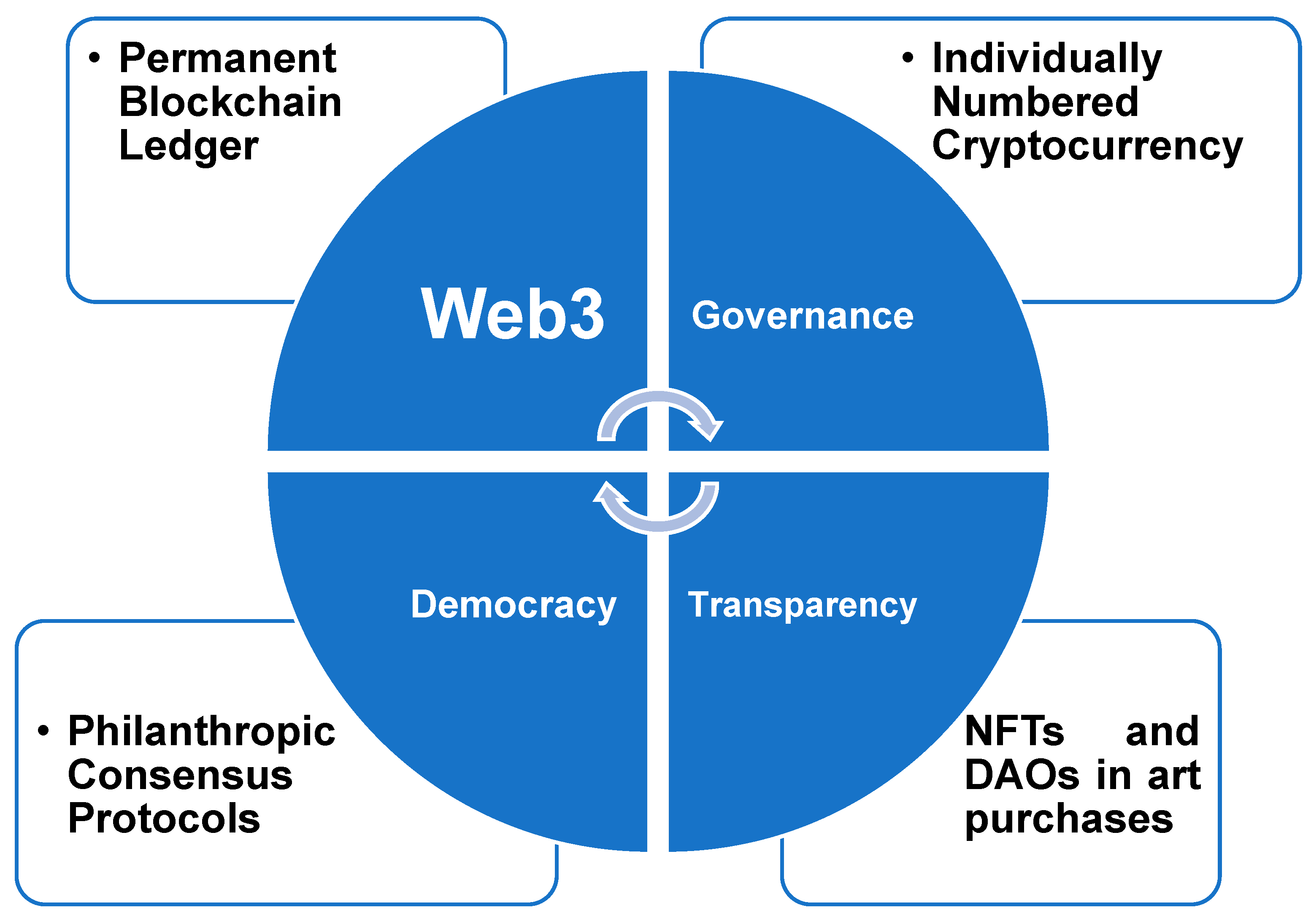

3.2. Web3: A Governance Instrument with Double Utility to Oversee the Acquisition of International Art Using DAOs and NFTs

“Proposition. Stakeholders and governance entities need to discuss how future law can capture the ambivalence of the person in a hybrid real-digital society and the interdependence between the personality interest and economic interests of gatekeepers. Generally, the problem of distribution of responsibility and liability between platform operators and users is becoming evermore challenging for social and e-commerce platforms”.

3.3. The Future of Web3 Governance: When DAOs and NFTs Are Used in Corporate Business and the International Art Market

“Upala protocol ensures that Price of forgery (PoF) is defined by the market which makes Upala, accurate, responsive, and reliable (even bots cannot beat the market). Every human verification method can be fairly and accurately measured with PoF”.

4. Limitations of Study

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A DAO could be programmed to comply with state or non-state funding agencies within a particular country or jurisdiction, for example, Arts Council funding in the UK. |

| 2 | Debbie Blockchain is a Publishing DAO who went dormant 5 February 2021. Ensembl is an Ethereum-based platform for decentralised organising of artistic production. |

| 3 | Elzeweig and Trautman (2023, p. 320) observe: The United States Security and Exchange Commission’ 2017 ‘DAO Report’ describe DAO token holders afforded voting rights as limited. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Petratos et al. (2020) discuss the emergence of blockchain technology in technological innovations, investment and sustainability. Digital finance is mentioned, which has a key role in purchasing, alongside marketing, exchange, and recording transactions in the international art market. |

| 6 | Mosley et al.’ (2022) ‘systematic understanding of blockchain governance’ study, identifies how DAOs can have a number of potential voting vulnerabilities. These are governance vulnerabilities that can subvert the outcome of proposals, which are then subsequently actioned by DAO intermediaries. |

| 7 | Salman and Razzaq (2019) discuss Bitcoins and how this cryptocurrency can wildly fluctuate in value. Salman et al’ pre-2020s study, warned then of the problems of the lack of regulation of cryptocurrencies. A sudden devaluation of a cryptocurrency would have a significant effect upon the reputation of an art house. A museum or gallery who bought an art piece using a particular cryptocurrency a few short weeks before its exchange rate fell sharply; would find that not only has the value of the art piece purchased fallen, but so would the art house’s reputational stock on the international market. This financial risk problem has not been solved by art based DAOs using NFTs to buy and sell art. NFTs have solved provenance, ownership and historical transaction problems; they have not solved the financial risk posed by a sudden devaluation or de-recognition of a particular NFT in the open art market. |

References

- Alex, ed. 2023. ‘Record Labels Are Dying!! #IndieIsTheNewNorm—Here’s Why…’. Music Lowdown, April 12. Available online: https://musiclowdown.co.uk/record-labels-dying/(accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Ali, Omar, Mujtaba Momin, Anup Shrestha, Ronnie Das, Fadia Alhajj, and Yogesh K. Dwivedi. 2023. ‘A review of the key challenges of non-fungible tokens’. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 187: 122248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambolis, Diana. 2023. NFT-based DAOs: How NFTs are Changing the Game in Web 3.0. Blockchain Magazine. May 16. Available online: https://blockchainmagazine.net/nft-based-daos-how-nfts-are-changing-the-game-in-web-3-0/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Andrew, Gretchen. 2023. What are DAOs? How blockchain-governed collectives might revolutionise the artworld. The Art Newspaper. February 23. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/02/23/what-are-daos-how-blockchain-governed-collectives-might-revolutionise-the-art-world (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Arts Council. 2023. CRF: Information for applicants offered funding. Arts Council: Culture Recovery Fund. Available online: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/culture-recovery-fund/crf-information-applicants-offered-funding (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- B (@beatyandpunk). 2022. The New Patrons: NFT Collectors and Supporters. Art Basel Conversations. June 16. Available online: https://www.artbasel.com/stories/conversations-art-basel-2022-nft-collectors-and-supporters?lang=en (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Becker, H. S. 1982. Art Worlds. Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. Available online: https://sabrinasoyer.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/howard-s-becker-art-worlds.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Beckett, Lois. 2022. ‘Huge mess of theft and fraud:’ artist sound alarm as NFT crime proliferates. The Guardian. January 29. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global/2022/jan/29/huge-mess-of-theft-artists-sound-alarm-theft-nfts-proliferates (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Biais, Bruno, Christophe Bisiere, Matthieu Bouvard, Catherine Casamatta, and Albert J. Menkveld. 2023. Equilibrium Bitcoin Pricing. The Journal of Finance (The Journal of THE AMERICAN FINANCE ASSCIATION) 78: 967–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binance. 2022. What is a DAO and How Does it Benefit NFTs. Binance Blog. June 22. Available online: https://www.binance.com/en/blog/nft/what-is-a-dao-and-how-does-it-benefit-nfts-421499824684903992 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Bleach, Tom. 2023. Web3 Foundation Calls for Regulatory Clarity But Warns Rules Should Address Behaviours Not Technology. The Fintech Times. June 30. Available online: https://thefintechtimes.com/web3-regulation-clarity-behaviours-technology/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Bogomolny, Sara. 2022. NFTs: Digital Renaissance or Death Knell of Traditional Art? Arts Management & Technology Library. June 14. Available online: https://amt-lab.org/blog/2022/6/nfts-digital-renaissance-or-death-knell-of-traditional-art (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Bonifazi, Gianluca, Francesco Cauteruccio, Enrico Corradini, Michele Marchetti, Daniele Montella, Simone Scarponi, Domenico Ursino, and Luca Virgili. 2023. Performing Wash Trading on NFTs: Is the Game Worth the Candle? Big Data and Cognitive Computing 7: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Phonographic Industry. 2021. Match of the Day: The Intersection of Music and Sport. December. London: British Phonographic Industry (BPI). Available online: https://www.bpi.co.uk/media/3140/bpi4.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Bron, Daniel. 2023. 10 Ways Web3 is Disrupting Traditional Business Models. LinkedIn Pulse. April 4. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/10-ways-web3-disrupting-traditional-business-models-daniel-bron- (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Carter, Rebekah. 2023. Why DAOs Matter and Why they Impact NFTs. XR Today, June 1. Available online: https://www.xrtoday.com/mixed-reality/why-daos-matter-and-why-they-impact-nfts/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Chainlink. 2022. DAOs and the Complexities of Web3 Governance. Blog. August 6. Available online: https://blog.chain.link/daos/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Chalmers, Dominic, Christian Fisch, Russell Matthews, William Quinn, and Jan Recker. 2022. Beyond the bubble: Will NFTs and digital proof of ownership empower creative industry entrepreneurs? Journal of Business Venturing Insights 17: e00309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie’s. 2023. Digital Art and NFTs. Available online: https://www.christies.com/en/events/digital-art-and-nfts/overview (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Cornelius, Kristin. 2021. Betraying Blockchain: Accountability, Transparency and Document Standards for Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). 2021. Information 12: 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, Diana. 1976. Reward Systems in Art, Science and Religion. American Behavioral Scientist 19: 719–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, Leo. 2023. Reframing the Art Market Ecosystem in a Web3 World. Sotheby’s Institute of Art. February 13. Available online: https://www.sothebysinstitute.com/news-and-events/news/reframing-art-market-ecosystem-in-web3-world (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Danto, Arthur. 1964. The Artworld. The Journal of Philosophy 61: 571–84. Available online: https://is.muni.cz/el/phil/jaro2014/IM088/Danto__1_.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- De Filippi, Primavera, Morshed Mannan, and Wessel Reijers. 2020. Blockchain as a confidence machine: The problem of trust & challenges of governance. Technology in Society 62: 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbie Blockchain and Ensembl. 2021. Hong Kong DAOs. Goethe Institute. February 5. Available online: https://www.goethe.de/ins/gb/en/kul/zut/dao/dah.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Denny, Simon. 2023. NFTs: An artists perspective. Art Basel. Available online: https://www.artbasel.com/stories/art-market-report-nfts-simon-denny?lang=en (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- De Nooy, Wouter. 2002. The dynamics of artistic prestige. Poetics 30: 147–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, Josh. 2022. How we finally evolve from Web2 to Web3. VentureBeat. February 13. Available online: https://venturebeat.com/datadecisionmakers/how-we-can-finally-evolve-from-web-2-0-to-web-3-0/ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Dwivedi, Yogesh K., Laurie Hughes, Abdullah M. Baabdullah, Samuel Ribeiro-Navarette, Mihalis Giannakis, Mutas M. Al-Debei, Denis Dennehy, Christy M. K. Cheung, Kieran Conboy, Samuel Fosso Wamba, and et al. 2022. Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management 66: 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Yogesh. K., Nir Kshetri, Laurie Hughes, Emma Louise Slade, Anand Jeyaraj, Arpan Kumar Kar, Abdullah M. Baabdullah, Alex Koohang, Vishnupriya Raghavan, Ryan Wright, and et al. 2023. Opinion Paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implication of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management 71: 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, Steven. 2023. What is Web3? Forbes. March 10. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/digital-assets/article/what-is-web3/?sh=374f827667a4 (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Elzeweig, Brian, and Lawrence J. Trautman. 2023. When Does a Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Become a Security? Georgia State University Law Review 39: 295–336. Available online: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3184&context=gsulr (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Evans, Brian D. 2023. Hollywood Meet Art: How NFTs Are Revolutionizing the Entertainment Industry. Rolling Stone. May 17. Available online: https://www.rollingstone.com/culture-council/articles/hollywood-meets-art-nfts-revolutionizing-entertainment-industry-1234736416/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Fan, Yuqing, Tianyi Huang, Yiran Meng, and Shenghui Cheng. 2023. The current opportunities and challenges of Web 3.0. arXiv, 1–23. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2306.03351.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Flamingo, Julia. 2023. What are DAOs and what can they bring to the art world? Art Curator Grid. February 22. Available online: https://blog.artcuratorgrid.com/what-can-daos-bring-to-the-art-world/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Flick, Catherine. 2022. A critical professional ethical analysis of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Journal of Responsible Technology 12: 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucher, Simon, Charles Denis, and Matthis Grosjean. 2023. Web3 & customer engagement. Sia Partners, White Paper 02. Available online: https://www.sia-partners.com/system/files/document_download/file/2023-07/WP%20Web3%20%26%20Customer%20engagement%20-%20SiaXperience%20x%20METAV.RS%20x%20Zealy.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Freeman Law. 2022. The History of Blockchain and Bitcoin. Freeman Law. Available online: https://freemanlaw.com/the-history-of-the-blockchain-and-bitcoin/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Fritsch, Felix, Jeff Emmett, Emaline Friedman, Rok Kranj, Sarah Manski, Michael Zargham, and Michel Bauwens. 2021. Challenges and Approaches to Scaling the Global Commons. Frontiers in Blockchain 4: 578721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Yan Lin. 2022. How DAOs are Funded. ConsenSys. December 7. Available online: https://consensys.net/blog/metamask/metamask-institutional/how-daos-are-funded/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Fundraising Regulator. 2022. Cryptocurrencies, NFTs and the Future of Fundraising. May 3. Available online: https://www.fundraisingregulator.org.uk/more-from-us/news/cryptocurrencies-nfts-and-future-fundraising (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- G’sell, Florence, and Florian Martin-Bariteau. 2022. The Impact of Blockchains for Human Rights, Democracy, and the Rule of Law. Council of Europe. Information Society Department, DGI2022.06. September. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/report-on-blockchains-en/1680a8ffc0 (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Ganatra, Raj. 2022. Web3 and Art: Unlocking the Future of Humanitarian Justice. Human Rights Pulse. June 18. Available online: https://www.humanrightspulse.com/mastercontentblog/web3-and-art-unlocking-the-future-of-humanitarian-justice (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Garbers-von Boehm, Katherina, Helena Hagg, and Katherina Gruber. 2022. Intellectual Property Rights and Distributed Ledger Technology: With a focus on art NFTs and tokenised art. European Parliament Study. PE 737.709. October. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/737709/IPOL_STU2022.737709_EN.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- GFS IT Solutions. 2023. Riding the Bandwagons of NFTs—Becoming a Part of Evolving World of NFT. LinkedIn Pulse. April 11. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/riding-bandwagon-nfts-becoming-part-evolving-world-gfs-it-solutions (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Gilbert, Sam. 2022. Crypto, Web3, and the Metaverse. University of Cambridge, Bennett Institute for Public Policy. Policy Brief. March. Available online: https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Policy-brief-Crypto-web3-and-the-metaverse.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Gitcoin. 2023a. Donate to Gitcoin Grants. Available online: https://www.gitcoin.co/ (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Gitcoin. 2023b. Benefits of Using Price of forgery in Gitcoin. Available online: https://gov.gitcoin.co/t/benefits-of-using-price-of-forgery-in-gitcoin/11314 (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Giuffre, Katherine. 1999. Sandpiles of Opportunity: Success in the Art World. Social Forces 77: 815–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaveski, Steve. 2022. How DAOs Could Change the Way We Work. Harvard Business Review. April 7. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/04/how-daos-could-change-the-way-we-work (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Goyal, Shubham. 2022. Web3 incoming: How far is it? Delta Exchange Blogs. July 15. Available online: https://www.delta.exchange/blog/web3-incoming-how-far-is-it/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Hackl, Cathy. 2021. What Are DAOs and Why You Should Pay Attention. Forbes. June 1. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/cathyhackl/2021/06/01/what-are-daos-and-why-you-should-pay-attention/?sh=635570a37305 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Hedera.com. 2023. Web3 vs Metaverse: The Differences and Connections. Available online: https://hedera.com/learning/metaverse/web3-vs-metaverse#:~:text=you’ll%20understand%3A-,Web%203.0%20is%20a%20concept%20for%20a%20decentralized%20version%20of,metaverse%20environments%20incorporate%20web3%20technology (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Hickley, Catherine. 2022. Art market goes crypto with NFTs. The UNESCO Courier, (United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization), 3, pp. 30–33. July–September. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000382095_eng (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Hilsberg, Victoria. 2023. DAOs and NFTs—what in the interconnection is going on? Medium. May 21. Available online: https://medium.com/@vic.hilsberg/daos-and-their-implications-to-the-nft-space-ab0030bebde4 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Holcombe-James, Indigo. 2022. Where Are Web3 Technologies Being Used? In Developments in Web3 for the Creative Industries: A Research Report for the Australian Council for the Arts. Edited by Ellie Rennie, Indigo Holcombe James, Alana Kushnir, Tim Webster and Benjamin A. Morgan. Melbourne: RMIT Blockchain Innovation Hub, November, pp. 43–48. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2022-11/apo-nid319849.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Huang, Ying, and Maximilian Mayer. 2022. Digital currencies, monetary sovereignty and U.S.-China power competition. Policy & Internet 14: 324–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-The, Thien, Thippa Reddy, Weizheng Wang, Gokol Yenduri, Pasika Ranaweera, Quoc.-Viet Pham, Daniel Benevides da Costa, and Madhusanka Liyananage. 2023. Blockchain for the metaverse: A Review. Future Generation Computer Systems 143: 401–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing Culture & Crypto. 2023. Cultural Bits and Bites. Jing Travel. August 20. Available online: https://jingculturecrypto.com/bits_n_bites/chinese-tourism-cultural-bit-n-bites/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Jones, Ioan Marc. 2022. Top fundraising tips for 2022. Charity Digital. August 15. Available online: https://charitydigital.org.uk/topics/topics/top-fundraising-trends-for-2022-9180 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Kaul, Sandy. 2023. Evolution & Revolution: Understanding Web3 and digital assets—Franklin Templeton’s new primer. Franklin Templeton Institute. July 31. Available online: https://franklintempletonprod.widen.net/content/ykjfzcquke/pdf/understanding-web3-and-digital-assets-a.pdf?_gl=1*1t8fv7e*_ga*NTUwMDU3MjQ0LjE2OTIzODg0Mjg.*_ga_15V8ZZDP8Z*MTY5MjM4ODQyNy4xLjEuMTY5MjM4ODUwMi4wLjAuMA (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Khan, Shafaq Naheed, Faiza Loukil, Chirine Ghedira-Guegan, Elhadj Benkhelifa, and Anoud Bani-Hani. 2021. Blockchain smart contracts: Applications, challenges, and future trends. Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications 14: 2901–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, Nikos, Tonia Damrakeraki, Lambis Dionysopoulos, Marianna Charalambous, George Giaglis, Zalan Noszek, Iordani Papoutsoglou, Konstantnos Votis, Ishan Roy, Jeff Bandmen, and et al. 2021. Demystifying Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Brussels: The European Union Blockchain Observatory & Forum. Available online: https://www.eublockchainforum.eu/sites/default/files/reports/DemystifyingNFTs_November%202021_2.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Kuta, Sarah. 2022. Art Made With Artificial Intelligence Wins at State Fair. Smithsonian Magazine. September 6. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/artificial-intelligence-art-wins-colorado-state-fair-180980703/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Layton, Roslyn. 2022. NFTs for Art and Philanthropy Could be Crypto’s Next Act. Forbes. September 27. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/roslynlayton/2022/09/27/its-not-yet-curtains-for-crypto/?sh=325bf4147d62 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Legge, Michelle. 2023. DAOs: Your Guide to Decentralized Autonomous Organizations. Koinly. July 5. Available online: https://koinly.io/blog/daos-decentralized-autonomous-organizations/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Liddell, Frances V. 2022. The Crypto-Museum: Investigating the impact of blockchain and NFTs on digital ownership, authority, and authenticity in museums. Ph.D. thesis, University of Manchester, School of Arts, Languages and Cultures, Manchester, UK. Available online: https://pure.manchester.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/216118534/FULL_TEXT.PDF (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Liden, Erik. 2022. Potential Advantages and Disadvantages of NFT-Applied Digital Art. Master’s thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, July 6. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1675570/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- LinkedIn. 2023. How can you use DAOs for better Web3 governance? LinkedIn: Web3. August 17. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/advice/0/how-can-you-use-daos-better-web3-governance-skills-web3 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Makridis, Christos A., and Esther Larson. 2023. How blockchain can help fund artists—and revive the arts. Philanthropy Daily. March 9. Available online: https://philanthropydaily.com/how-blockchain-can-help-fund-artists-and-revive-the-arts/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Mao, Xinrou. 2023. Is dao a utopia? Its past, ongoing practice and the future. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. March 10. Available online: https://www.outofframe.mit.edu/allposts/hojlvdun1w2x8hwg40dowxj0n3wtym (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Marr, Bernard. 2022. The Best Examples of DAOs Everyone Should Know About. Forbes. May 25. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2022/05/25/the-best-examples-of-daos-everyone-should-know-about/?sh=1fc48fd40c3c (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Mateus, Sara, and Soumodip Sarkar. 2023. Can Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) Revolutionize Healthcare? California Management Review. January 2. Available online: https://cmr.berkeley.edu/assets/documents/pdf/2023-01-can-decentralized-autonomous-organizations-daos-revolutionize-healthcare.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- McKenna, Saro. 2023. How DAOs Can Turn The NFT Rebound Into A Web3 Success Story. Forbes. August 9. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2023/08/09/how-daos-can-turn-the-nft-rebound-into-a-web3-success-story/?sh=7bd48125503b (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Mesidor, Cleve. 2023. Crypto Artists Share How Web3 Tools Enable Diverse Art Market Experiments. Forbes. May 1. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/digital-assets/2023/05/01/crypto-artists-share-how-web3-tools-enable-diverse-art-market-experiments/?sh=4833785a64b0 (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Morris, David Z. 2023. CoinDesk Turns 10—How The DAO Hack Changed Ethereum and Crypto. CoinDesk. May 15. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/consensus-magazine/2023/05/09/coindesk-turns-10-how-the-dao-hack-changed-ethereum-and-crypto/ (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Morris, Jane. 2022. Can NFTs make a comeback. Apollo. November 30. Available online: https://www.apollo-magazine.com/nfts-art-market-crypto-crash-digital-art/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Mosley, Lawrence, Hieu Pham, Xiaoshi Guo, Yogesh Bansal, Eric Hare, and Nadia Antony. 2022. Towards a systematic understanding of blockchain governance in proposal voting: A dash case study. Blockchain: Research and Applications 3: 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mues, Adela, Soham Panchamiya, Matthew Townsend, Hagen Rooke, Brett Hillis, Jonathan T. Ammons, and Mira Bagaeen. 2023. ADGM Regulations on Virtual Assets and Decentralized Autonomous Organization. Reed Smith Client Alerts. April 21. Available online: https://www.reedsmith.com/en/perspectives/2023/04/adgm-regulations-on-virtual-assets (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Mukaddam, Farah. 2021. NFTs and Intellectual Property Rights. Norton Rose Fulbright, October. Available online: https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/1a1abb9f/nfts-and-intellectual-property-rights (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Murray, Michael D. 2022. NFTs and the Art World—What’s Real, and What’s Not. UCLA Entertainment Law Review 29: 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalee. 2022. NFT Provenance and how it will change Art forever. NFT Culture. August 22. Available online: https://www.nftculture.com/guides/nft-provenance-and-how-it-will-change-art-forever/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Natalee. 2023. Beyond the Pixels: Decoding Web3 Gaming and NFT Challenges. NFT Culture. June 1. Available online: https://www.nftculture.com/nft-news/beyond-the-pixels-decoding-web3-gaming-and-nft-challenges/ (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Newberry, Deborah. 2023. Mitigating future risk: Anticipating reputational exposures in an ESG-conscious world. Kennedys Law. April 23. Available online: https://kennedyslaw.com/en/thought-leadership/article/2023/mitigating-future-risk-anticipating-reputational-exposures-in-an-esg-conscious-world/ (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2022. Why Decentralised Finance (DeFi) Matters and the Policy Implications. Paris: OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-markets/Why-Decentralised-Finance-DeFi-Matters-and-the-Policy-Implications.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Oleh, Malanii. 2023. NFT Smart Contract Audit: Ultimate Guide. HACKEN. June 2. Available online: https://hacken.io/discover/security-audit-for-nft-guide-for-founders-and-managers/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Park, Hyejin, Ivan Ureta, and Boyoung Kim. 2023. Trend Analysis of Decentralized Autonomous Organizations Using Big Data Analytics. Information 14: 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penningtons Manches Cooper. 2023. Decentralised Autonomous Organisations—The New Frontiers for Corporate Structures, March 9. Available online: https://www.penningtonslaw.com/news-publications/latest-news/2023/decentralised-autonomous-organisations-the-new-frontier-for-corporate-structures (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Perper, Rosie. 2023. The NFT Louvre Exhibit That Wasn’t: Untangling the Public Mess of a Non-Event. CoinDesk. March 17. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/web3/2023/03/17/the-nft-louvre-exhibit-that-wasnt-untangling-the-public-mess-of-a-non-event/ (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Petratos, Pythagoros N., Nikolina Ljepava, and Asma Salman. 2020. Blockchain Technology, Sustainability and Business: A Literature Review and the Case of Dubai and UAE. In Sustainable Development and Social Responsibility—Volume 1: Proceedings of the 2nd American University in the Emirates International Research, AUEIRC’18—Dubai, UAE 2018. Edited by Miroslav Mateev and Jennifer Nightingale. Cham: Springer, pp. 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radermecker, Anne-Sophie V., and Victor Ginsburgh. 2023. Questioning the NFT “Revolution” withing the Art Ecosystem. Arts 12: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Emily. 2021. Philanthropy on the Blockchain: Giving DAOS and the Next Generation of Giving Circles. Dorothy A. Johnson Center for Philanthropy. December 14. Available online: https://johnsoncenter.org/blog/philanthropy-on-the-blockchain-giving-daos-and-the-next-generation-of-giving-circles/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Ray, Partha Pratim. 2023. Web3: A comprehensive review on background, technologies, applications, zero-trust architectures, challenges and future directions. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems 3: 213–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, Ellie. 2022. What is Web3? In Developments in Web3 for the Creative Industries: A Research Report for the Australian Council for the Arts. Edited by Ellie Rennie, Indigo Holcombe James, Alana Kushnir, Tim Webster and Benjamin A. Morgan. Melbourne: RMIT Blockchain Innovation Hub, November, pp. 11–23. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2022-11/apo-nid319849.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Ritter-Doring, Verena, Charlotte Hill, and Miroslav Duric. 2023. That’ll be the DAO: An overview of the structure and status of decentralised autonomous organisations under English Law. Taylor Wessing. April 4. Available online: https://www.taylorwessing.com/en/insights-and-events/insights/2023/04/that-will-be-the-dao (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Roose, Kevin. 2022. What are DAOs? The Latecomer’s Guise to Crypto. The New York Times. March 18. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/03/18/technology/what-are-daos.html (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Sadowski, Jathan, and Kaitlin Beegle. 2023. Expensive and extractive networks of Web3. Big Data & Society 10: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Yoshiro, and John A. Rose. 2023. Reputation-based Decentralized Autonomous Organizations for the non-profit section: Leveraging blockchain to enhance good governance. Frontiers in Blockchain 5: 1083647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, Asma. 2019. Digital Currencies and the Power Shift in the Economy. In Creative Business and Social Innovations for a Sustainable Future. Edited by Miroslav Mateev and Panikkos Poutziouris. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation (IEREK Interdisciplinary Series for Sustainable Development). Cham: Springer, pp. 123–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, Asam, and Muthanna G. Abdul Razzaq. 2018. Bitcoin and the World of Digital Currencies, Financial Management from an Emerging Market Perspective. In Financial Management from an Emerging Market Perspective. Edited by Guray Kucukkocaoglu and Soner Gokten. London: IntechOpen, pp. 269–81. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapter/pdf-download/57380/6569117 (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Salman, Asma, and Muthanna G. Abdul Razzaq, eds. 2019. Blockchain and Cryptocurrencies. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillig, Michael Anderson. 2023. Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) Under English law. Law and Financial Markets Review, February 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, Steve, and Kate Wilson-Milne. 2023. The Promise of NFTs for Art and the Art Market. The Art Law Podcast. Interview with Amy Whittaker. March 1. Available online: https://artlawpodcast.com/2023/03/01/the-promise-of-nfts-for-artists-and-the-art-market/ (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Schroeders Wealth Management. 2022. What are NFTs and How Do They Work in the Art World, June 15. Available online: https://www.schroders.com/en-ch/ch/wealth-management/insights/what-are-nfts-and-how-do-they-work-in-the-art-world/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- See, Geoffrey, Ashlin Perumall, and Assel Zhannasova. 2022. Are ‘Decentralized Autonomous Organisations’ the Business Structures of the Future?’. World Economic Forum. June 23. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/are-dao-the-business-structures-of-the-future/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Sharma, Tanusree, Yujin Kwon, Kornrapat Pongmala, Henry Wang, Andrew Miller, Dawn Song, and Yang Wang. 2023. Unpacking How Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) Work in Practice. arXiv, April 17, arXiv:2304.09822. [Google Scholar]

- Shilina, Sasha. 2022. A Comprehensive Study on Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs): Use Cases, Ecosystem, Benefits & Challenges. May. Moscow: Lomonosov Moscow State University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, Alexandra. 2020. Blockchain and Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs): The Evolution of Companies. New Zealand Universities Law Review 28: 423–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Sean Stein. 2022. Cryptocurrency-funded groups called DAOs are becoming charities—here are some issues to watch. The Conversation. February 4. Available online: https://theconversation.com/cryptocurrency-funded-groups-called-daos-are-becoming-charities-here-are-some-issues-to-watch-174763 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Sotheby’s. 2023. Natively Digital: A Curated NFT Sale. Available online: https://www.sothebys.com/en/digital-catalogues/natively-digital-a-curated-nft-sale (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- South South Art. 2023. Online Art Community: Global South Contemporary Art. Available online: https://south-south.art/ (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Stackpole, Thomas. 2022. ‘What is Web3?’ Your guide to (what could be) the future of the internet. Harvard Business Review. May 10. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/05/what-is-web3 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Stanescu, Alexandru, and Tudor Velea. 2023. The emergence of DAOs: From the legal structuring to dispute resolution. Global Legal Insights. Available online: https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/blockchain-laws-and-regulations/17-the-emergence-of-daos-from-legal-structuring-to-dispute-resolution (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Stublic, Helena, Matea Bilogrivic, and Goran Zlodi. 2023. Blockchain and NFTs in the Cultural Heritage Domain: A Review of Current Research Topics. Heritage 6: 3801–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SuperRare® Labs. 2023. Terms of Service, version 4.1. April 5. Available online: https://campaigns.superrare.com/terms (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Takac, Balasz. 2022. The Art World Responds to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine by Wide Walls. Artist at Risk. April 13. Available online: https://artistsatrisk.org/2022/04/13/press-the-art-world-responds-to-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine-by-wide-walls/?lang=en (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Troncoso, Stacco. 2019. The Open Coop Governance Model in Guerrilla Translation: An Overview. In Decentralized Thriving: Governance and Community on the Web 3.0. Edited by Felipe Duarte. DAOSTACK.IO. pp. 100–17. Available online: https://daostack.io/ebook/decentralized_thriving.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- United Kingdom HM Treasury. 2023. Future Financial Services Regulatory Regime for Cryptoassets: Consultation and Call for Evidence; February. London: HM Treasury. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1133404/TR_Privacy_edits_Future_financial_services_regulatory_regime_for_cryptoassets_vP.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- United Kingdom Parliament. 2022. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and the blockchain. Written evidence submitted by Sorare. DCMS Select Committee. Available online: https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/114732/pdf/ (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Van Rees, C. J. 1983. How a literary work becomes a masterpiece: On the threefold selection practised by literary criticism. Poetics 12: 397–417. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwi_5NjB5biBAxUIg1wKHQjyCy0QFnoECBcQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%2Fscience%2Farticle%2Fpii%2F0304422X83900153%2Fpdf%3Fmd5%3D3c8035514478ceeccc9af1170b548 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Vasan, Kishore, Milan Yanosov, and Albert-Laszlo Barabasi. 2022. Quantifying NFT-driven networks in crypto art. Scientific Reports 12: 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, Mara. 2023. Could 2023 be the Year of the DAO? Cultured. January 12. Available online: https://www.culturedmag.com/article/2023/06/02/vincent-van-duysen-zara-home-collection (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Velthuis, Olav. 2005. Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, Federico. 2023. Empowering Web3: The Rise of Decentralized Governance and DAOs. LinkedIn Pulse. April 11. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/empowering-web3-rise-decentralized-governance-daos-federico-weill (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Weinstein, Gail, Steven Lofchie, and Jason Schwartz. 2022. A primer on DAOs. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. September 17. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/09/17/a-primer-on-daos/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Wieder, Bernadine Brocker. 2023. Discover Acrual’s Pioneering Blockchain Technology. ArtReview. March 17. Available online: https://artreview.com/discover-arcuals-pioneering-blockchain-technology/ (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- World Economic Forum and Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. 2022. Decentralized Autonomous Organizations: Beyond the Hype. In White Paper. Geneva: World Economic Forum (WEF), June, Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Decentralized_Autonomous_Organizations_Beyond_the_Hype_2022.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- World Economic Forum and Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. 2023. Decentralized Autonomous Organizations Toolkit: Insight Report. Geneva: World Economic Forum (WEF), January, Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Decentralized_Autonomous_Organization_Toolkit_2023.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Yanger, Zack, and Noah Davis. 2021. All About NFTs—SuperRare’s Zack Yanger and Christie’s Head of NFTs Noah Davis. Art Sense by Canvia. Episode 12. September 14. Available online: https://kite.link/Art-Sense-Episode-12?utm_source=embed&utm_medium=webplayer (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Zhang, Hedy. 2022. What Are the Potential Uses and Things to Consider for NFTs in the Arts Museum Field? Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University, May 6, Available online: https://courses.ideate.cmu.edu/62-830/s2022/?p=1579 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Zhen. 2023. Revolutionizing Art with Web3—Art Group’s Journey Empowered by IOST. Medium. IOST in Hong Kong. July 7. Available online: https://medium.com/iost/iost-in-hong-kong-revolutionizing-art-with-web3-art-groups-journey-empowered-by-iost-f79fd0674ea7 (accessed on 4 August 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duke, B. The Shape of International Art Purchasing—The Shape of Things to Come. Arts 2023, 12, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050208

Duke B. The Shape of International Art Purchasing—The Shape of Things to Come. Arts. 2023; 12(5):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050208

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuke, Benjamin. 2023. "The Shape of International Art Purchasing—The Shape of Things to Come" Arts 12, no. 5: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050208

APA StyleDuke, B. (2023). The Shape of International Art Purchasing—The Shape of Things to Come. Arts, 12(5), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050208