Abstract

For many women living in parts of present-day north China and Mongolia during the 10th to 14th centuries, equestrian activities were a part of daily life. Women of all social levels were expected to know how to ride from an early age. However, documentary evidence for women’s participation in equestrian activities during this period is sparse. This paper brings together materials that highlight the important role horse riding played in the lives of northern women during the 10th to 14th centuries from the funerary context. This study connects funerary objects with women’s participation in polo, hunting, warfare, and the Mongol postal system, among other activities. The synthesis of material evidence from tombs with period texts will illuminate the important role of equestrian activities in women’s lives and afterlives during this period.

1. Introduction

In 2005, archaeologists excavated the remains of the tomb of Wang Shiying 王世英 (d. 1306) and his wife, née Xiao 蕭 (d. 1315), near Xi’an in Shaanxi Province. The tomb had been looted, but certain objects in the front chamber of the double-chambered tomb had been left intact, including two equestrian figures with boxes strapped to their backs, possibly representing postal couriers (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Identified as women in the excavation report, the gender of these figures is, in fact, unclear. Nonetheless, the possibility of these ceramic figures being women underscores the lack of representation of women equestrians in the material record during the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty (ca. 1271–1368) despite the well-established record of the importance of horse riding to Mongol women. In fact, equestrian activities were practiced by women in north China throughout the middle period (ca. 10th–14th centuries) despite the lacuna in the visual record. This article brings together the evidence for women equestrians in middle-period North China preserved in visual and material culture, focusing on the Kitan-ruled Liao dynasty (ca. 907–1125) and Yuan dynasty. Through an analysis of the material, this article aims to contribute to a clearer understanding of the different ways women engaged in equestrian pursuits at different levels of society.

Horse riding was a central facet of the lives of elite and non-elite women alike among groups living in present-day north China and Mongolia during the 10th to 14th centuries, and the funerary evidence for different types of equestrian activities illuminates the role horse riding had in both life and in death, especially for elite women. Horse riding was an essential part of women’s labor in the nomadic contexts of the Mongol and Kitan camps, but elite women in the northern Chinese context also rode horses as a source of entertainment and to participate in important political and ceremonial events. Through an examination of clothing, adornment, horse tack, and artistic representations, all from tombs, a visual understanding of the diverse functions of horse riding in the lives and afterlives of women who lived in the 10th to 14th centuries in northern China and Mongolia emerges. Beginning with an introduction to the image of the woman equestrian in Chinese funerary art prior to the 10th century, this article will primarily focus on a series of Kitan and Mongol women’s tombs with surviving examples of equestrian equipment and/or representations of equestrian activities.

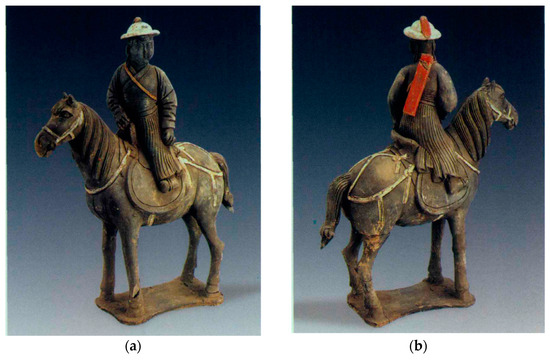

Figure 1.

(a,b) Front and back views of painted ceramic equestrian figures from the Tomb of Wang Shiying (d. 1305) and his wife, née Xiao (d. 1315), which were discovered in 2005 near Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China. Yuan dynasty ca. 1315. H. 36.8 cm, L. 31 cm. After Xi’an shi wenwu baohu kaogu su Figure 2 and Figure 3.

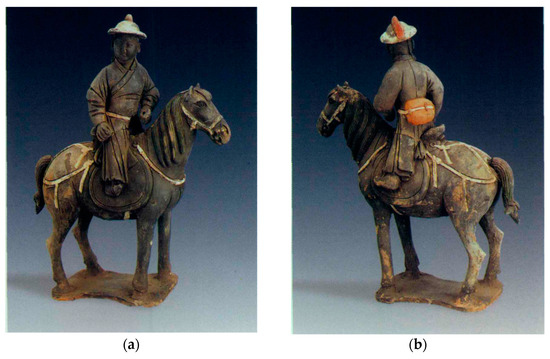

Figure 2.

(a,b) Front and back views of painted ceramic equestrian figures from the Tomb of Wang Shiying (d. 1305) and his wife, née Xiao (d. 1315), which were discovered in 2005 near Xi’an, Shaanxi Provice, China. Yuan dynasty ca. 1315. H. 36.8 cm, L. 31 cm. After Xi’an shi wenwu baohu kaogu su Figure 4 and Figure 5.

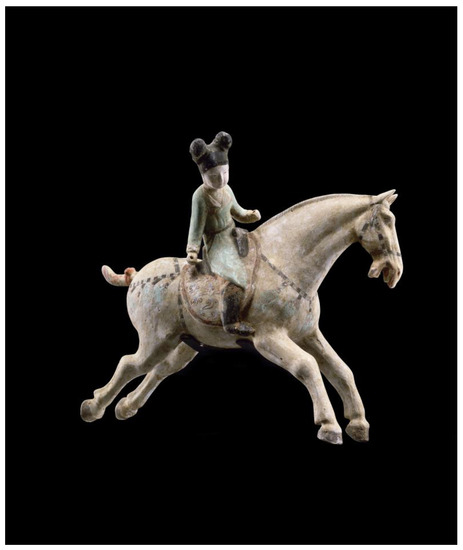

Figure 3.

Horse and female rider. Tang dynasty (618–907), 7th century. Astana cemetery, Xinjiang province, China. Unfired clay with pigment. H. 36.2 cm, L. 29.2 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1951 accession number 51.93a, b.

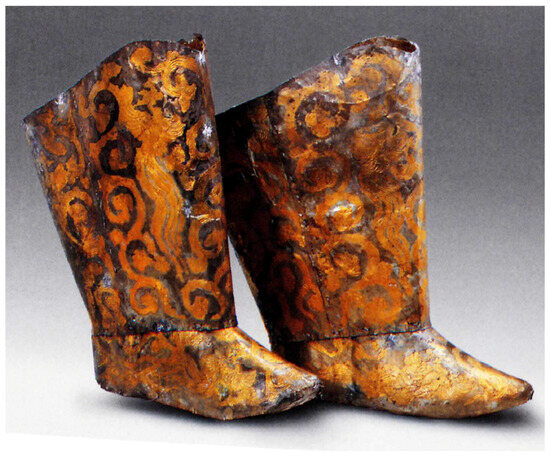

Figure 4.

Young woman polo player. Tang Dynasty, first half of the 8th century. Painted unglazed ceramic. Musée Guimet. MA 6117.

Figure 5.

Song Dynasty copy (by Song Emperor Huizong?) of Tang origin attributed to Zhang Xuan (713–755), Lady Guoguo’s Spring Outing. Hand scroll, ink and colors on silk. 52 × 148 cm. Liaoning Provincial Museum.

2. Women Equestrians in Funerary Art before the 10th Century

Horse riding was deeply connected to martial prowess during the Tang dynasty and was seen as central to the power of the Tang state. Riding was restricted to members of the military and the upper classes, yet it was also a period in which women participated actively in equestrian activities (Harrist 1997, pp. 22, 25). Indeed, tombs dating to the Tang dynasty (ca. 618–907) preserve representations of women equestrians. Ceramic figures of fashionably dressed women equestrians, such as those found in the Astana cemetery near Turfan (Figure 3), and women polo players dressed in Central Asian style men’s clothing, from Tang tombs and presently in the collections of museums such as the Musée Guimet in Paris (Figure 4), are two well-known types of these equestrian figures. Such funerary representations may stand in as an idealized depiction of the living world, which would indicate that women participated in a variety of equestrian activities, and indeed, the textual record and court art seem to support this conjecture. For example, the painting Lady Guoguo’s Spring Outing (Figure 5), traditionally attributed to the Tang dynasty court painter Zhang Xuan (ca. 713–755 CE) but probably a later copy, shows an elite woman and her entourage (including a little girl with her nurse) out on a ride, an activity suitable for their social class and gender. The women seem comfortable in their saddles and are clearly enjoying a ride in the spring weather. This representation of Tang beauties on horseback ties to figures such as those found in Astana, although the context is different. Both the Astana figures and Lady Guoguo’s Spring Outing can be said to be idealized representations of Tang beauties, showcasing both the high fashion and equestrian abilities of elite Tang dynasty women.

But what of women engaging in more active equestrian pursuits such as polo? We might initially interpret the presence of young women playing polo in the funerary context as some sort of playful amalgamation of tropes of entertainment (watching an exciting and popular elite game) and the depiction of beautiful women. The occasional reference to women playing polo in Tang poetry might be thought of the same way (Chehabi and Guttmann 2003, p. 316), that is, that this elite form of entertainment was represented for the benefit of the (male) poetry reader or the (male) deceased and beautiful women were inserted into the roles of the players to add another layer of enjoyment for the male gaze—a version of the trope of paintings and poetry of lovelorn women that became popular in the Song dynasty (Blanchard 2018, pp. 157–58). However, recent archaeological evidence has complicated our understanding of polo as a sport enjoyed not only by young men but also by women and older men. The ninth-century tomb excavated in 2012 near Xi’an of Cui Shi, wife of the high-ranking official Bao Zhou, contains the remains of three donkeys, which a team of Chinese and American researchers argue were polo donkeys used by Cui Shi in her lifetime.1 In the Tang dynasty, polo was extremely popular amongst the elite, with certain Tang emperors allegedly so obsessed with the game that they neglected their duties.2 Characterized in the Tang dynasty as a sport that helped men stay fit for martial activities, the fact that women and older men seem to have enjoyed playing polo as well may indicate that the young women depicted in funerary sculptures were not figments of artistic imagination but instead representations of a version of polo played by women otherwise only referenced in Tang poetry. In the Tang dynasty, then, the visual evidence points to equestrian activities for women as something principally engaged in for entertainment purposes. Horses were ridden during leisurely outings of upper-class women or while playing the popular elite sport of polo.

3. Women and Hunting after the 10th Century

Polo, as a favored sport to keep soldiers fit for warfare, decreased in popularity after the fall of the Tang dynasty (Liu 1985, pp. 215–18). In fact, the place of the horse in Chinese culture declined in general during the less militarily focused Song dynasty (Harrist 1997, p. 26). Among the northern groups who assumed power in northern China after the fall of the Tang and for whom horse riding was essential, hunting, rather than polo, was the most significant equestrian activity. Polo was played by elites in the Kitan Liao dynasty and Jurchen Jin dynasty (ca. 1115–1234), but it did not have the same political cache as hunting. Hunting, in some ways, might be seen as a form of entertainment, similar to polo, but it was much more politically significant. Indeed, the role of the hunt as a politically meaningful as well as practical activity has been established by scholars for both the Kitan, who formed the Liao dynasty in present-day north China and Mongolia, and the Mongols, who conquered the majority of Eurasia in the 13th century and formed the Yuan dynasty under Kubilai Khan (r. 1264–1294). Considering the role that women played in this significant activity provides a more robust understanding of the hunt in addition to filling in gaps in the historical record of women and their activities during these eras. Although they enjoyed a more visible and physically active role in their respective societies than many of their sedentary counterparts, dynastic histories such as the History of the Liao Dynasty (Liao shi) and the History of the Yuan Dynasty (Yuan shi), compiled by Confucian officials after the fall of the dynasties in question, rarely provide information about the formidable women who played crucial roles both within domestic spaces and in the public sphere. This is certainly the case with the hunt; any mention of women hunting in historical texts comes from records written by foreign envoys or an occasional funerary epitaph. By looking at the texts together with the material, hints of the role women played in the hunt begin to emerge. As we will see, in the Liao and the Yuan, women rode for a variety of reasons at all levels of society, including, in contrast to the Tang, quotidian labor and hunting.

Two court paintings, Banquet at the Kitan Camp, see see Shea (2020, plate 5), attributed to the Liao dynasty painter Hu Gui (fl. late 10th century), and Kubilai Khan Hunting (Figure 6), attributed to the Yuan dynasty painter Liu Guandao (act. 1275–1300), feature women in courtly hunting contexts. Kubilai Khan Hunting portrays an imperial hunt with the Yuan emperor Kubilai Khan and his favorite wife, Chabui (ca. 1227–1281), by his side, while Banquet at the Kitan Camp shows a celebratory meal with the ruler and his consort seated on a mat or carpet, attended to by servants and watching a dance performance. The Kitan banquet may be a representation of the type of ceremony that took place after the first day of successful hunting during a particularly important hunt, such as the swan hunt, which happened each year in the spring (Shea 2020, pp. 24–26; Tuotuo [1344] 1974, juan 32, 373–74). Both paintings depict a politically and culturally important activity with the consort of the ruler given a central role. Court-commissioned paintings depicting the inclusion of women in the hunt or the banquet after the hunt effectively underscore the essential role played by the close female relatives (in this case, wives or consorts) of rulers. These two paintings provide insights into the idealized structure of the Khan’s royal hunt, on the one hand, and the Kitan banquet after the hunt, on the other.

Figure 6.

Liu Guandao (active ca. 1275–1300). Kubilai Khan Hunting, dated 1280. Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk. 182.9 cm × 104.1 cm. Image source: National Palace Museum, Taipei.

This paper approaches women’s roles in the hunt in the Liao and Yuan dynasties together for several reasons. First, the Kitan and the Mongols were nomadic groups originating from present-day Mongolia for whom horse riding was an essential part of daily life, and as such, they share certain cultural characteristics. In addition, when the Kitan established the Liao, pre-imperial Mongol groups lived contemporaneously with the Liao dynasty in parts of Mongolia, and the material evidence from different places in north China and Mongolia provides useful comparisons. Finally, the Liao provided an important precedent for Yuan rule in China, impacting everything from the societal structure to dress (Morgan 1982, p. 129; Shea 2020, pp. 13, 22–31, 42). Although the Liao dynasty in China fell to the Jurchen Jin in 1125, members of the ruling Yelü family fled to Central Asia under the leadership of Yelü Dashi, where they established the Qara Khitai, or Western Liao. The Qara Khitai did not fall until the Mongol conquests in that region in 1218, and Kitan influence on the emerging Mongol empire can be felt through both aspects of culture and societal structure borrowed from the Liao and the Qara Khitai (Biran 2020). Looking at the evidence for women and the hunt in the Liao and Yuan in concert provides a more robust context for the role women played in the hunt. In part, the lack of material for both the Liao and the Yuan has to do with the archaeological evidence that has thus far been excavated. In the Yuan context, for example, the tombs with some of the best-preserved material evidence belonged to non-Mongol northern Chinese, who may have been loyal to the Mongol regime and showed their allegiance visually through the selective adoption of dress practices (Shea 2020, 84–85 and 93 n. 76 and n. 77; Steinhardt 2007, pp. 140–74). These northern Chinese did not, as a rule, participate in Mongol hunts. As Roslyn Hammers points out, there was legislation that barred Chinese from using bows and arrows during the Yuan, and Kubilai issued edicts in 1285 and 1290 proscribing hunting to all but those with “special privileges”.3 Thus, we might find Mongol-style clothing in these tombs, but depictions of the hunt or hunting implements are only found rarely. As new archaeological evidence comes to light, the author of the present paper expects to revise or expand her analysis of the material and any provisional conclusions reached here.

The role of elite hunting among various groups across Eurasia, including the Kitan and the Mongols, as a political activity that both showcased the power of the ruler and served as a preparation for warfare has been established by Thomas Allsen (Allsen 2006, pp. 209–32). As Allsen has shown, when ruling groups moved from the active conquering of territory to the formation of their states, the necessity of hunting as a form of subsistence became less important, while it increased in political and ceremonial significance. Allsen points out that this follows a pattern in pre-modern societies in Eurasia; when the domestication of plants and animals grows within a given society, that is, when a society becomes more sedentary, the hunt decreases in economic importance but increases in political significance (Allsen 2006, p. 2). While the Kitan and the Mongol ruling classes never became sedentary, the hunt, as practiced by the Liao and Yuan courts as they established their newly expanded empires, took a few different forms. The most important hunts were extended trips taken by the ruler and his court to hunting areas located some distance from a capital city. Such trips would range from a few days to several months; Allsen proposed that the longer the trip, the more politically and ceremonially important the hunt (Allsen 2006, p. 21).

4. On War and Hunting

The connection between warfare and hunting has also been well established, and because the textual evidence for both women hunting and women participating in warfare is not very robust, it is worth briefly summarizing some of the historical findings for both activities. The scholars Hang Lin and Linda Cooke Johnson have done groundbreaking work to illuminate the active roles of elite Kitan women (Johnson 2011; Lin 2018, 2020). Morris Rossabi was one of the first to write about the role of women in Mongol society, and Hong Zaixin, with Cao Yiqiang, outlined the important roles the wives of khans played in the politics and administration of the Mongol Empire in their analysis of the painting Khublai Khan Hunting (Rossabi 1979; Hong and Cao 1999, p. 195). More recently, Bruno De Nicola has written extensively about the role of Mongol women in socio-political contexts, especially in the Ilkhanate (De Nicola 2010, 2013, 2017). Johnson and Lin have both written about the roles that elite Liao women played in politics and warfare, focusing especially on Liao Empress Dowagers Yingtian (878–953) and Chengtian (953–1009), who led troops into battle and helped negotiate major treaties after the battles were fought (Shea 2021, p. 39; Johnson 2011, pp. 129–30; Lin 2018, p. 191). Rossabi notes that women were “from early childhood…offered military training. As adults many of them were excellent horsewomen and skilled archers, some of them were as adept at riding and shooting as their men” (Rossabi 1979, p. 154; citing Christopher Dawson 1980, p. 18). De Nicola has pointed out that elite Mongol women were sometimes given troops as part of their dowry, sometimes actively controlled these troops, and on occasion participated in military campaigns (De Nicola 2010, pp. 103–9). However, as De Nicola notes, from the historical evidence, it appears that while some high-ranking Mongol women controlled their own troops (directly or indirectly), women rarely actively participated in military campaigns, and those who did were firmly part of the Chinggisid elite (De Nicola 2010, pp. 104, 107). Based on the findings of Johnson and Lin, this same observation can probably be extended to Kitan women as well; their participation in warfare was exceptional, and those who did participate were part of the ruling elite.

5. Visual Evidence

The visual and material evidence for women’s participation in the hunt falls into three categories—court art (painting), funerary art, and clothing and objects of adornment preserved in the funerary context. Unfortunately, Banquet at the Kitan Camp and Kubilai Khan Hunting are all that survive from the 10th–14th centuries of court paintings that feature women in hunting or hunting-adjacent activities. The ruling class of Kitan and Mongol women participated in political decisions, military campaigns, and important ceremonial events, so it follows that they had some role to play in the hunt. Indeed, even if Kubilai Khan Hunting does not represent a particular event (and there is some evidence that it was painted after Chabui’s death as a memorial) (Shea 2020, p. 60), it was likely that Chabui accompanied Kubilai on some hunts. As recorded by the papal envoy John of Plano Carpini (1182–1252), “Young girls and women ride and gallop on horseback with agility like the men. We even saw them carrying bows and arrows. Both the men and the women are able to endure long stretches of riding. They have very short stirrups; they look after their horses very well, indeed they take the very greatest care of all their possessions… All the women wear breeches and some of them shoot like men” (Carpini in Dawson 1980, p. 18).

In the Kitan context, evidence for horse riding survives from burials of elite women, such as the Princess of Chen (1018) or the Yemaotai (ca. 959–986) tombs, where saddles, quivers, arrows, bows, and other equestrian or hunting equipment were preserved in the tomb with the deceased (Figure 7).4 Some of the equipment and clothing interred with the deceased appeared to have been worn in life, while some, such as the burial suits of the Princess of Chen and her husband, which included metal boots, were made specially for the funerary context (Kinoshita 2006). The walls of the princess of Chen’s tomb feature a hunting scene, and a hunting scene is painted on the wooden sarcophagus of the female occupant of the Yemaotai tomb (Johnson 2011, pp. 14, 35–36). The Princess of Chen was a member of the royal family, and archaeologists speculate that the woman in the Yemaotai tomb was also royalty due to the fine quality of goods, including some gold-woven fabrics, interred with her (Shea 2021, pp. 50–51).

Figure 7.

Pair of boots, tomb of Princess of Chen and Xiao Shaoju, Qinglongshan, Naiman Banner, Inner Mongolia. Liao dynasty, ca.1018. Gilded silver, L. 29.2 cm, H. 37.5 cm. Research Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology of Inner Mongolia. After Kinoshita 2006, cat. 4.

The importance of hunting materials and depictions in the funerary context complements what we know of elite Liao women in life. For instance, the Song envoy Lu Zhen 路振 (957–1014)5 describes Empress Dowager Chengtian going out for the hunt (and repeating gossip about the Empress Dowager having an affair with the powerful official, Han Derang 韓德讓) in his 1009 account, Cheng yao lu 乘軺錄: “Every time [the empress dowager] went out to hunt, [she] always abode with [Han] Derang in the same rounded tent” (Wright 1998, p. 30). Linda Cooke Johnson also points out the combination of desired traits in elite Kitan women included accomplishments in the literary arts as well as mastery of equestrian arts, including hunting, as noted on the epitaph of Xiao Fei 蕭妃 (d. 1071), about whom it was written: “She rode horseback ably, was adept at archery, and enjoyed hunting. When hunting, she withheld her shot until she was certain of hitting her prey”.6

Few burials of identifiably Mongol women have survived, but the only known undisturbed rock burial excavated in the Mongolian Altai, at the site of Üzüür Gyalan, is a notable example of a Mongol woman’s tomb (Pearson et al. 2019, pp. 56–70). This tomb dates to the 10th century, the pre-imperial period, in other words, contemporaneous to the Liao Yemaotai tomb, but a few decades before the Princess of Chen’s burial. The Üzüür Gyalan burial was for a middle-aged woman who was buried with a horse, complete with saddle bags, a felt saddle blanket, and tack, including bridle, saddle, girths (cinch), and crupper (Pearson et al. 2019, p. 58). As with the Yemaotai burial, the deceased seems to have been interred with favored objects she used in life. Unlike the Princess of Chen and Yemaotai burials, which date from the Liao imperial period, the woman in the Üzüür Gyalan burial lived in Mongolia prior to the confederation of groups by Chinggis Khan and the subsequent establishment of the Mongol Empire. In other words, she did not live in an imperial system. The objects in her tomb are of good quality, but none are made of expensive materials such as gold or silver, and many of the garments and other textiles show that they were worn and repaired (Pearson et al. 2019, p. 58). The horse interred with the deceased was likely a favored one she rode in life (Pearson et al. 2019, p. 58). The horse buried with the tomb occupant parallels the favored polo donkeys interred with Madame Cui in Tang Chang’an mentioned above, although the context is quite different. The Üzüür Gyalan burial features a favored horse that the deceased rode to do daily tasks, while the polo donkeys in Madame Cui’s tomb are among many luxury possessions that give us insight into the leisure activities of the deceased. As for hunting, while horse riding was an important activity for the woman buried in Üzüür Gyalan, none of the burial objects found in her tomb indicate that she was a hunter.

Few Yuan period tombs feature hunting motifs in their murals, but, as is the case in the Liao context, none of the tomb paintings show women hunting.7 The only potential artistic representations of women equestrians in Yuan period tombs that the author of the present paper is aware of are from the early 14th-century tomb of Wang Shiying 王世英 and his wife, née Xiao 蕭, mentioned at the beginning of this article (Figure 1 and Figure 2) (Xi’an Shi Wenwu Baohu Kaogu Suo 2008). Xiao was the surname of the imperial consort clan in the Liao dynasty, and women from this family continued to marry into elite ranks in the Yuan dynasty, so it is possible that the female occupant came from this elite Kitan lineage. Wang Shiying was not important enough to be given an official biography in the Yuan shi, but thanks to the funerary epitaph that was found in the tomb, we know some information about his life and career. According to the funerary epitaph, which was commissioned by the Xiao family upon the death of his wife in 1315, Wang Shiying served during his career (beginning in 1268) in various capacities in the Mongol bureaucracy as Mongolian language interpreter, provincial envoy, county magistrate, in addition to serving in the army, notably in a battle against the Song army (which ended in a Yuan loss), when the Song besieged Chengdu (Sichuan).8 Therefore, although he was not high ranking enough to have a biography in the Yuan shi, Wang Shiying was well-ensconced in the upper echelons of Yuan society, learning the Mongolian language well enough to be an interpreter, serving the administration loyally, and marrying a woman from the powerful Xiao family, a family who still held power and status during the Yuan.

As previously noted, Wang Shiying’s tomb had been looted, but there were still several well-preserved artifacts within the front chamber in addition to the epitaph, including two painted ceramic equestrian figures identified by the archaeological team as women (Xi’an Shi Wenwu Baohu Kaogu Suo 2008, p. 53). One of the figures has a rectangular box strapped to its back, while the other has a square-shaped bag/box strapped to its lower back. The size and shape of the bag/boxes, along with their situation in an equestrian context, may indicate that the boxes were document carriers and that these figures represent post-road couriers.9 Similar figures were excavated from Xiadian Village near Xi’an and are now in the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, although they are neither identified as women in their museum context (Figure 8) nor in the catalog where they are published (Shoudu Bowuguan 2016, pp. 132–33). The authors of the catalog do not provide information about their excavation, nor has an excavation report been published, so we do not have information about the tomb where these figures were found (Shoudu Bowuguan 2016, pp. 132–33). Nonetheless, it is significant that such similar figures were found in the vicinity of Xi’an; their similarity suggests they were products of the same workshop. The representation of courier figures in the tombs of officials such as Wang Shiying evokes the Mongol post-road system, or yām, a significant feature of Mongol administration. The yām was the crucial communication system of the Mongol empire, consisting of way stations every 20–30 miles.10 These were staffed by couriers whose job it was to quickly ride from one station to the next, swapping out fresh horses when they arrived at way stations and ensuring the rapid communication of people, goods, and ideas across Mongol territories. These figures, within the context of the tomb of a Yuan official, may have functioned as a sign of the official status of the deceased, who, in life, surely sent messages via the yām system.

Figure 8.

Front view (with reflected back) of a ceramic figure of a postal courier unearthed from Xiadian Village, Chang’an District, Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China. Yuan dynasty. H. 37.5 cm, l. 32 cm. Collection of the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology. Image source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E5%85%83%E8%B4%9F%E5%9B%8A%E9%AA%91%E9%A9%AC%E4%BF%91.jpg (accessed on 12 August 2023).

The two ceramic figures from Wang Shiying’s tomb, as with their counterparts In the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, wear typical Mongol men’s clothing—a side-closing outer robe cinched at the waist with a belt, with a brimmed hat, trousers, and boots. Three other standing ceramic figures, also dressed in male clothing, were also identified as women in the excavation report. No records account for women specifically working on the postal roads as couriers, although Mongol women often had physically demanding jobs. Alongside elite women sometimes participating in hunting and warfare, women at all levels of society would herd animals and were in charge of packing up wagons to move camp (Rubruck in Dawson 1980, pp. 95, 103). Additionally, Yuan governmental policy assigned specific jobs required for the smooth running of the empire to households (for example, post-road couriers), which meant that if a man was not available to do a job (due to absence or death), women would be obliged to step into the role assigned to her family. In the record Heida Shilüe 黑韃事畧 (A Sketch of the Black Tatars), the Song dynasty envoy Peng Daya’s 彭大雅 observations from a visit to the Mongol territories in 1233, expanded upon by Xu Ting’s 徐霆 (another Song envoy) record from 1235–1236, both men note that Mongol women did many tasks on horseback. Peng writes, “In horsemanship and archery, babies are tied with cords onto plats which then are fastened onto horses’ backs, so they can go about with their mothers” (Peng Daya in Atwood 2021, p. 211). Xu Ting elaborates on Peng’s observations with this anecdote:

I saw an old Tatar lady, when she had finished giving birth to a baby in the wilderness. She used sheep’s wool to wipe off the child, then used a sheepskin for swaddling clothes. Binding the baby up in a little cart, four or five feet long and one foot wide, the old lady thereupon tucked the cart crosswise under her arm and straightaway rode off on horseback.(Xu Ting in Atwood 2021, p. 212)

This is a strange story—why would Xu Ting have been in a position to witness a woman giving birth? As his account of the Mongols highlights, the Mongol population that Xu Ting interacted with were post-road couriers during his travels within the empire and personnel at the Mongol court, and it is unlikely that he witnessed a woman giving birth and immediately riding off on her horse to take up courtly duties, so it is plausible that this was a woman he saw who was working along the postal road, filling in for an absent male relative.11 Therefore, while no specific accounts of women postal couriers exist, in reading between the lines of Xu Ting’s narrative, the possibility of women postal workers in the Yuan becomes more likely.

The archaeologists identify these ceramic figures as women based on their face shape and hairstyle, which is comparable to Chabui’s in Kubilai Khan Hunting. That is, they all have their hair in two looped braids that fall behind the ears. However, this hairstyle cannot be taken as proof of gender; Mongol men wore their hair in a similar style, as seen in the portrait of Kubilai Khan attributed to Anige, now in the National Palace Museum (Figure 9). Neither does the dress of the figures specifically indicate gender. While the material evidence that has been preserved in court paintings, tomb murals, and Buddhist donor portraits shows elite Mongol women almost uniformly portrayed wearing court dress, they must have worn other types of clothing while performing more quotidian activities, including the many different tasks that they performed from horseback (Shea 2020, p. 89). This dress was different from the more quotidian northern Chinese style women’s dress we find depicted in many Yuan dynasty tombs and would have resembled men’s dress in basic ways. The similarity of men’s and women’s dress was remarked upon by visitors to the Mongol courts, such as John of Plano Carpini (who we recall mentioned that women wore breeches) and William of Rubruck. For example, William of Rubruck comments, “The costume of the girls is no different from that of the men except that it is somewhat longer” (Rubruck in Dawson 1980, p. 102). Based on the available evidence, we cannot definitively identify the gender of these postal road couriers. If these ceramic figures indeed represent women, they are another example of Mongol women wearing clothing similar to that of men outside of the court context and when engaging in many of the physically strenuous activities that were part of Mongol women’s daily lives. What is more significant, perhaps, is the presence of these postal road couriers in the first place in this tomb, no matter their gender. Wang Shiying and his wife were connected to the higher ranks of the Mongol government. Perhaps the depiction of postal workers in the funerary context represented some of the lived experiences of people in the Yuan dynasty or served as a reminder of Wang’s official position in the administration, just as ceramic figures of men and women playing polo may have represented a version of reality in the Tang context. Most polo players and postal couriers were men, but the ceramic figures of women performing these roles may have been a way of taking delight in the spectacle of women doing physical activities normally associated with men, especially in the Chinese context.

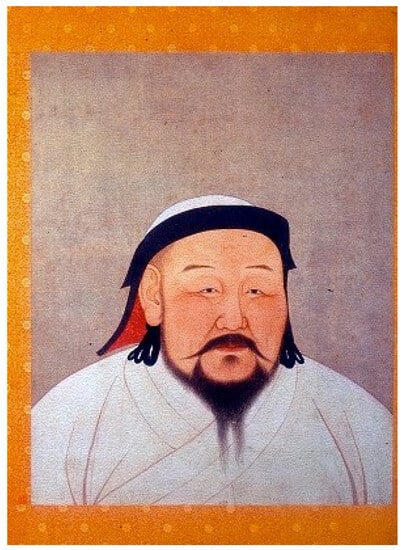

Figure 9.

Anige (1245–1306), Portrait of Kubilai. 1294, Yuan dynasty. Album leaf, colors and ink on silk. Height: 59.1; width: 47.6 cm. Image source: National Palace Museum, Taipei.

6. Conclusions

The evidence is far from complete, but based on the visual and textual materials currently available, we can safely say that women during the Liao and Yuan dynasties were avid equestrians and sometimes participated in activities we might associate with men. Horseback riding was such an important activity for Kitan and Mongol women that it was sometimes specifically memorialized in the funerary context through the preservation of tack and horse-riding clothing worn in life alongside pictorial representations of equestrian activities. Bruno De Nicola points out that the evidence for Mongol women participating in warfare only pertains to the ruling classes, and the evidence we have for Kitan women participating in warfare is also restricted to royalty (princesses, empresses, and empress dowagers) (De Nicola 2010, pp. 104, 107). Similarly, only members of the ruling elite would have had anything to do with the ceremonial hunts that were so culturally and politically important. However, women from varying levels of society would have ridden horses and probably hunted as part of their lives as pastoralists. Add to this the fact that women substituted for male family members when necessary in government-assigned jobs, and the notion of gendered labor and tasks seems to break down even further. Based on the available evidence, we can observe that, in general, horse riding for women in the Liao and Yuan periods was not undertaken for entertainment or leisure purposes, as was the case in the Tang dynasty. While focused on the funerary context, the types of visual and material evidence evaluated here range from court paintings and tombs of imperial family members to tombs of non-imperial local elites and historical texts. The author of this paper hopes that this has, therefore, provided a wide range of evidence to support the importance of equestrian activities for women in Liao and Yuan societies and expects that as more tombs are excavated, more evidence for the range of women’s equestrian activities will be uncovered.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

A draft of this article was originally presented at the Medieval Academy of America annual conference in Washington, D.C. on 24 February 2023. Thank you especially to Christopher Atwood who served as discussant for the panel for his invaluable feedback and comments on this paper. Thank you also to the three anonymous readers who generously provided feedback and suggestions.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | (Hu et al. 2020). While historians have known that polo was sometimes played with donkeys or mules or even on foot, the archaeological evidence gives more credence to these historical references. See (Liu 1985, p. 205). |

| 2 | (Liu 1985, p. 209); For the history of polo in China, see (Chehabi and Guttmann 2003, pp. 315–17; Li et al. 2009; Liu 1985). |

| 3 | (Hammers 2015, 14 n. 40): “Endicott-West, “The Yuan Government and Society”, 595. In 1263, Kubilai issued an imperial decree allowing Mongols, Uighurs, Muslims, police, appointees of the Mongol government who collected taxes, merchants who traveled long distances in caravans, and hunting households to carry bows and arrows”. For the edicts of 1285 and 1290 Hammers cites the Yuan Shi: (Song [1370] 1976): juan 277, 339–40. “This restriction was still in force after Kubilai’s death. In 1312 Temür Oljeytü Khan, or Emperor Chengzong (r. 1294–1307), restated that Chinese were not allowed to carry bows and arrows to hunt.” (Hammers 2015, 14 n. 41). |

| 4 | For both tombs: (Johnson 2011, pp. 11–13; Shea 2021, pp. 50–53). For Yemaotai: (Liaoning Sheng Bowuguan 1975). For Princess of Chen: (Sun 2006, pp. 71–72). |

| 5 | Lu Zhen’s biography is in (Tuotuo [1345] 1977, juan 441). |

| 6 | (Johnson 2011, pp. 11–12). Original: “頗習騎射。嘗在獵圍。料其能中則發。發卽應弦而倒。” (Chen 1982, pp. 193–94). |

| 7 | Sanyanjing tomb in Inner Mongolia (discovered 1965, excavation report 1982) has a mural depicting a falcon; Tomb from Luogetai Village, Shaanxi (excavated 2014, excavation report 2016) has murals depicting hunting. For the Sanyanjing tomb: (Xiang and Wang 1982). For the Luogetai Village tomb: (Xing et al. 2016). |

| 8 | Funerary epitaph; see (Xi’an Shi Wenwu Baohu Kaogu Suo 2008, pp. 67–68). The authors of the excavation report point out that there are some discrepancies between the account of the battle between Song and Yuan forces at Chengdu recorded on the funerary epitaph and the Yuan Shi, notably that the funerary epitaph dates the battle 5 years earlier than the Yuan Shi. See also (Song [1370] 1976, juan 7: 144). |

| 9 | Thanks to Christopher Atwood for suggesting this possibility to me and guiding me toward references, including (Shoudu Bowuguan 2016, pp. 132–35), which reproduces one of the ceramic figures from Wang Shiying’s tomb alongside a few others from Xiadian Village near Xi’an. |

| 10 | For the history of the Mongol yām system, including its establishment under Chinggis Khan, see (Silverstein 2007, pp. 145–48). |

| 11 | Thanks to Christopher Atwood for suggesting this possibility to me. |

References

- Allsen, Thomas T. 2006. The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Atwood, Christopher Pratt. 2021. The Rise of the Mongols: Five Chinese Sources. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Biran, Michal. 2020. The Qara Khitai. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, Lara C. W. 2018. Song Dynasty Figures of Longing and Desire: Gender and Interiority in Chinese Painting and Poetry. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Chehabi, Houchang E., and Allen Guttmann. 2003. Diffusion of Polo. In Sport in Asian Society: Past and Present. Edited by Fan Hong and James A. Mangan. London: F. Cass, pp. 309–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shu 陳述, ed. 1982. Quan Liao Wen. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju Chuban-She. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Christopher. 1980. Mission to Asia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Nicola, Bruno. 2010. Women’s Role and Participation in Warfare in the Mongol Empire. In Soldatinnen. Gewalt und Geschlecht im Krieg vom Mittelalter bis Heute. Edited by Klaus Latzel, Silke Satjukow and Franka Mausbach. Paderborn: Schöningh, pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- De Nicola, Bruno. 2013. Ruling from tents: The existence and structure of women’s ordos in Ilkhanid Iran. In Ferdowsi, The Mongols and Iranian History: Art, Literature and Culture from Early Islam to Qajar Persia. Edited by Robert Hillenbrand, Andrew C. S. Peacock and Firuza Abdullaeva. London: IB Tauris, pp. 116–36. [Google Scholar]

- De Nicola, Bruno. 2017. Women in Mongol Iran: The Khatuns, 1206–1335. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammers, Roslyn Lee. 2015. Khubilai Khan Hunting: Tribute to the Great Khan. Artibus Asiae 75: 5–44. [Google Scholar]

- Harrist, Robert E. 1997. Power and Virtue: The Horse in Chinese Art. New York: China Insittute Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Zaixin, and Yiqiang Cao. 1999. Pictorial Representation and Mongol Institutions in Khubilai Khan Hunting. In Arts of the Sung and Yüan: Ritual, Ethnicity, and Style in Painting. Edited by Cary Y. Liu and Dora C. Y. Ching. Princeton: The Art Museum, pp. 180–201. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Songmei, Yaowu Hu, Junkai Yang, Miaomiao Yang, Pianpian Wei, Yemao Hou, and Fiona Marshall. 2020. From pack animals to polo: Donkeys from the ninth-century Tang tomb of an elite lady in Xi’an, China. Antiquity 94: 455–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Linda Cooke. 2011. Women of the Conquest Dynasties: Gender and Identity in Liao and Jin China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, Hiromi. 2006. Pair of Boots. In Gilded Splendor: Treasures of China’s Liao Empire (907–1125). Edited by Hsueh-Man Shen. New York: Asia Society, p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhongshen 李重申, Jinmei Li 李金梅, and Yang Xia 夏阳. 2009. Zhongguo ma qiu shi. Lanzhou: Gansu Jiaoyu Chuban She. [Google Scholar]

- Liaoning Sheng Bowuguan 辽宁省博物馆 [Liaoning Provincial Museum]. 1975. Faku Yemaotai Liaomu jilue. Wenwu 12: 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Hang. 2018. The Khitan Empress Dowagers Yingtian and Chengtian in Liao China, 907–1125. In A Companion to Global Queenship. Edited by Elena Woodacre. Yorkshire: Arc Humanities Press, pp. 183–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Hang. 2020. Empress Dowagers on Horseback: Yingtian and Chengtian of the Khitan Liao (907–1125). Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 73: 585–602. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, James T. C. 1985. Polo and Cultural Change: From T’ang to Sung China. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 45: 203–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, David. 1982. Who Ran the Mongol Empire? Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 1: 124–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Kristen Rye, Chuluunbat Mönkhbayar, Galbadrakh Enkhbat, and Jamsranjav Bayarsaikhan. 2019. The Textiles of Üzüür Gyalan: Towards the identification of a nomadic weaving tradition in the Mongolian Altai. Archaeological Textile Review 61: 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rossabi, Morris. 1979. Kubilai Khan and the Women of His Family. In Studia Sino-Mongolica: Festschrift für Herbert Franke. Müchener Ostasiatiche Studien, Band 25. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag GmbH, pp. 153–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, Eiren L. 2020. Mongol Court Dress, Identity Formation, and Global Exchange. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, Eiren L. 2021. Intentional Identities: Liao Women’s Dress and Cultural and Political Power. Acta Via Serica 6: 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shoudu Bowuguan 首都博物馆. 2016. Da Yuan San Du. Beijing: Kexue Chuban She. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, Adam J. 2007. Postal Systems in the Pre-Modern Islamic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Lian 宋濂. 1976. Yuan Shi. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. First published 1370. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, Nancy. 2007. Yuan Period Tombs and Their Inscriptions. Ars Orientalis 37: 140–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Jianhua. 2006. The Discovery and Research on the Tomb of the Princess of Chen and Her Husband, Xiao Shaoju. In Gilded Splendor: Treasures of China’s Liao Empire (907–1125). Edited by Hsueh-Man Shen. New York: Asia Society, pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tuotuo 脫脫. 1974. Liao Shi. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. First published 1344. [Google Scholar]

- Tuotuo 脫脫. 1977. Song Shi. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. First published 1345. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, David Curtis, trans. 1998. The Ambassadors Records: Eleventh-Century Reports of Sung Embassies to the Liao. Bloomington: Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Xi’an Shi Wenwu Baohu Kaogu Suo 西安市文物保护考古所. 2008. Xi’an nanjiao Yuandai Wang Shiying mu qingli jianbao. Wenwu 6: 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Chunsong 项春松, and Jianguo Wang 王建国. 1982. Neimeng zhaomeng Chifeng Sanyanjing Yuandai bihua mu. Wenwu 1: 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Fulai 邢福来, Yifei Miao 苗轶飞, Bo Feng 冯博, and Juntao Yao 姚俊涛. 2016. Shaanxi Hengshan Luogetai cun Yuandai bihua mu jianbao. Kaogu Yu Wenwu 5: 63–74. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).