Abstract

In her 2022 video installation, Blast Furnace No. 2, artist Su Yu Hsin explores the history of the German factory, Henrichshütte Ironworks. Namely, the artist focuses on Henrichshütte’s former blast furnace, which was bought by a Chinese steel mill in September 1989 and moved to China, where it operated until 2015. Now a state-owned museum, this former factory, located in Hattingen, Germany, is a snapshot of the past—a memorial of sorts for the region’s bygone industrial prosperity. The history and intercontinental movement of this blast furnace inspires Su’s affinities towards spaces located in-between shifting temporalities, identities, and changing environmental conditions within Hattingen and beyond. Su weaves archival materials, documentary film, and interview excerpts into a speculative narrative that connects the years 1989, 2022, and 2050. Blurring reality and imagination, the video follows the fictionalized trail of Lin, a Chinese translator who accompanied the dismantling of the blast furnace over thirty years ago. According to the narrative, Lin left behind an unfinished science fiction novel, which takes place in 2022. In Lin’s novel, the protagonist develops a utopian machine in the form of a blast furnace. With this apparatus, she sends herself into space with the goal of finding an alternative energy source to replace coal. Blast Furnace No. 2 constellates temporal spaces of socio-political and environmental nostalgia, predicated upon both remembered and imagined understandings of the past, present, and future. The work emphasizes contradictory gaps in between socially driven ideological systems and their afterlives, determined to memorialize what most would just as soon forget.

1. Introduction: Archive as Method

In spring 2022, contemporary multimedia artist Su Yu Hsin debuted her video installation, Blast Furnace No. 2, as part of FUTUR 21—art, industry, culture, an art festival bringing together 16 industrial German museums and 32 artists.1 From November 2021 through April 2022, artists, primarily based throughout Europe, were invited to stage digital artworks, light installations, and spatial interventions across these museums located in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), a region known as the cradle of German industry.

Festival organizers invited Su, born in Taipei and currently based in Berlin, to explore the history of a blast furnace called Blast Furnace No. 2, formerly of the German factory, Henrichshütte Iron and Steel Works, located in Hattingen, Germany.2 Conducting site visits, archival research and interviews, Su learned that this blast furnace was bought by a Chinese steel mill in 1989 and moved to China’s Hunan Province where it operated until 2015. Now a state-owned museum, this German factory, where Blast Furnace No. 2 originates, is a snapshot of the past—an afterlife of sorts for the NRW’s bygone industrial history.

The history and intercontinental movement of the physical blast furnace inspires Su’s affinities towards spaces located in-between shifting temporalities and identities. The artist’s research also underscores changing environmental conditions and growing anxieties regarding the increasingly dire effects of climate change within this region and beyond.3 As is common throughout her artistic practice, Su weaves together archival materials, documentary film, sound, and interview excerpts into a fictional narrative, which constellate the years of 1989, 2022, and 2050. In this way, the artist approaches questions concerning the death and the afterlife of space, place, and even ideology from an allusively speculative perspective.

2. Su Yu Hsin’s Blast Furnace No. 2

Blurring reality and imagination, Blast Furnace No. 2 (which adopts the same name as the physical blast furnace) follows the fictionalized trail of Lin, a female Chinese translator who accompanied the dismantling of the blast furnace over thirty years ago. While Su’s representation of Lin is not biographical, in a January 2023 interview the artist revealed that her characterization of Lin is based on the actual male translator who accompanied the dismantling of the blast furnace over thirty years ago. According to the video’s narrative, (the female) Lin left behind an unfinished science fiction novel, which takes place in the year 2022. In the novel, Lin’s protagonist develops a utopian machine in the form of a blast furnace. With this apparatus, she sends herself into space with the goal of finding an alternative energy source to replace coal. The work reimagines bygone socio-cultural and ideological systems such as labor-driven economies that rely on the extraction and metallurgical refinement of fossil fuels. Su’s project also critiques ways in which the factory-turned-museum space remembers its own industrial past against the backdrop of our current global climate crisis (Figure 1).

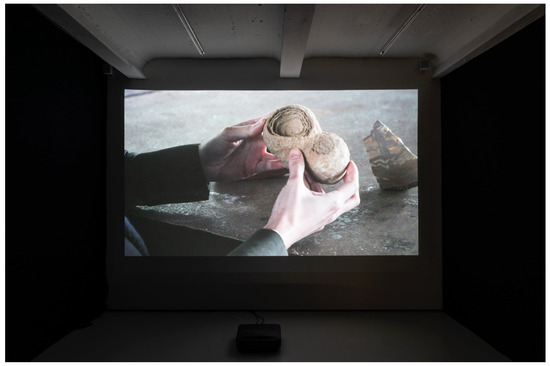

Figure 1.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, installation view in The Unexpected Universe—Traces of the Anthropocene, courtesy of the artist. Photo by Marcus Schneider.

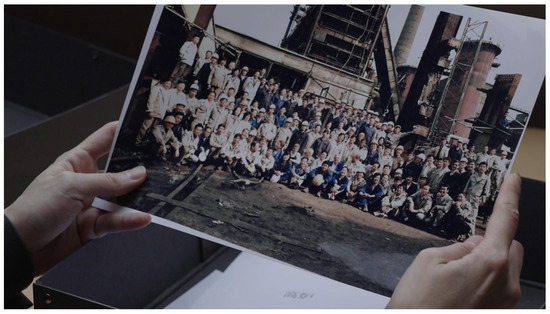

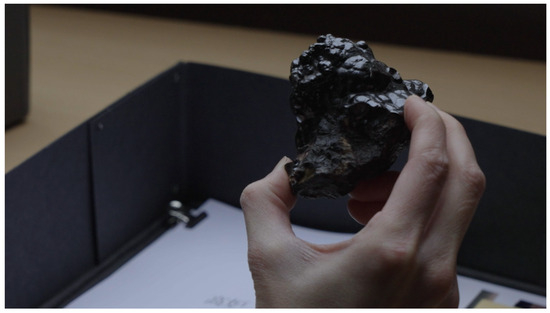

The video begins with a German-speaking voiceover describing Lin’s journey into the stars. The camera slowly pans over a silicate mineral rock, whose dark blue hues mimic a sparkling night sky. The video cuts to scenes from the former factory and then to a dimly lit room. We see a woman sitting at a desk. Having just arrived in Hattingen to make a documentary, she combs over factory archives. She scans through old photographs of workers posing in front of the blast furnace.

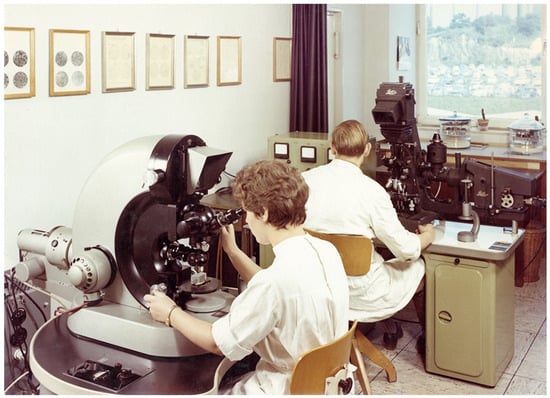

Suddenly, the video transports us to a sepia-tinted past. We see images of German scientists peering through large microscopes along with other individuals running tests in a laboratory (Figure 2). A man examines a document that has presumably just been printed out of a machine. Once again, we return to the present, where the former laboratory now stands, only now covered in rust following years of disrepair and exposure to the elements.

Figure 2.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, Video Installation (still), courtesy of the artist and ThyssenKrupp Corporate Archives, Duisburg.

In a subsequent scene, old factory blueprints are immediately juxtaposed with a black-and-white pencil drawing of Lin’s imagined utopian machine. It becomes apparent that these materials belong to Lin’s own abandoned archive which includes her unfinished novel. Situated in the present, this drawing allows us to peer into the past. We see the same retro computers and control panels from the former factory laboratory. A bed is prominently placed in the center of the drawing with a dynamic blast of energy radiating upwards. The narrator notes that this vertical energy current is powerful enough to project Lin’s protagonist up into the heavens.

Finally, we return to the small room where the filmmaker grasps the pencil drawing mentioned above, along with the novel manuscript. It becomes clear that, just like Lin’s fictional heroine who propelled herself into outer space, Lin also embarked on her own one-way mission of sorts—from a socialist (with Chinese characteristics) China to the west.

Svetlana Boym (1966–2015) defines nostalgia (from nostos, return home; and algia, longing) as “longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed,” and thus defies conventional notions of time and space (Boym 2001). She adds, “nostalgia itself has a utopian dimension, only it is no longer directed toward the future. Sometimes nostalgia is not directed towards the past either, but (is) rather sideways” (Boym 2001).4 Within a localized context of this factory-turned museum, the deliberate preservation of select monumental structures, including the blast furnace, along with rocks, minerals, and other objects are, to borrow Boym’s words, suspended “sideways” in time (Boym 2001). In other words, they take on a new meaning and context as part of a collection, separated from their original context, origin, or prior industrial function. As the video’s German-speaking narrator iterates, “time moves differently here. It thickens, pools, flows, rushes, slows”. We might understand this statement to mean that one’s conception and experience of time is inextricably linked to the presence (or absence) of industrial labor, in addition to the temporalities of extracted raw earth materials. Simply put, time contains multitudes. In this way, I suggest that such a rhizomatic temporal framework allows Blast Furnace No. 2 to move beyond the present and address a kind of utopian nostalgia activated by both the museum and the artist’s attention towards the histories of minerals and other organic matter found in and around the former factory campus.5

The former Henrichshütte Iron and Steel Works was founded in 1854 (Figure 3). This factory was responsible for the mining of iron ore and coal as well as coke, iron smelting and steel production, until it closed in 1987.6 Over 10,000 people worked within this industrial area, rolling, casting, and forging metal.7 Now, over 150 years since Henrichshütte first opened, visitors engage with this factory-turned-museum’s permanent exhibition, “Der Weg des Eisens”, or The Path of Iron, in English.8 Moving through the complex, people follow the process of transforming raw materials into hot metal, and finally, cast iron.9 According to one website, “with your own (f)antasy(,) you can (sense the liveliness) of working life (in) Henrichshütte”.10 As Boym points out, fantasy is also a key element of nostalgia (Boym 2001). Su capitalizes on this and other cosmic fictions within the narrative structure of Blast Furnace No. 2.

Figure 3.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, Video Installation (still), courtesy of the artist and ThyssenKrupp Corporate Archives, Duisburg.

Throughout the video, the narrator details temporalities of extraction, stating that our solar system originated from a gigantic dust cloud in the universe approximately four and a half billion years ago. Dust clouds, which contained elements of iron ore, became part of planet Earth. Once celestial bodies themselves, these raw earth materials exist across time. The narrator continues to explain that the sun within our own solar system is a fourth-generation star. Over the course of several billions of years, as each sun died out, massive explosions produced the same iron that has been extracted and refined into industrial materials within this region of Hattingen, Germany, as well as in China’s Hunan Province, and elsewhere. In this way, death is marked by both cyclicality and the rebirth of new stellar energies and structures. Connections among the global, regional, and hyper-local underscore how geological conditions, extraction economies, and social histories shape planetary conditions which have a dramatic impact on labor and industry.

According to the video, in 1989, the fictional translator Lin arrived in Germany with a group of 119 Chinese engineers, workers, and chefs. Over the course of a few months, laborers carefully dismantled Blast Furnace No. 2. Objects marked in red were shipped to China. Anything smudged with yellow pigment remained in Hattingen (Figure 4). To this day, these objects stained in a faded canary yellow quietly recall their long-separated counterparts (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, Video Installation (still), courtesy of the artist.

Figure 5.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, Video Installation (still), courtesy of the artist.

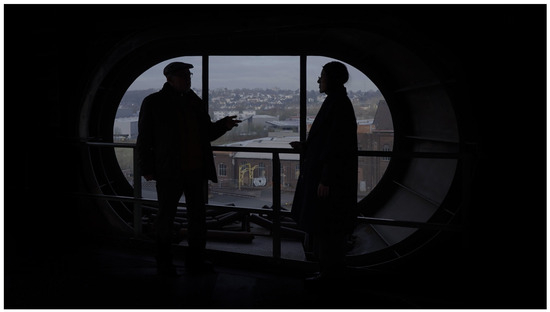

As a translator, Lin functions as an intermediary between two geographies, languages, and temporalities (Figure 6). She negotiates between a purported socialist system (in China) and a capitalist system (in Germany). Her unique positionality permeates with nostalgia for either, both, and simultaneously neither, system, all at the same time. Her unfinished science fiction novel reflects both the time and place in which she lived as well as post-1989 socio-political conditions. As indicated in the video, Lin leaves China for Europe in a way that is likened to her fictional heroine, who builds an apparatus “capable of catapulting her straight from her bed into outer space” (Su 2022). Lin adds that her protagonist, “took the reverse path of the iron meteorites… to the molten core of an asteroid located between Mars and Jupiter” (Su 2022). Lin’s character travels through the Earth’s atmosphere into outer space, equipped with a metal shield that protects her from immense vertical currents of energy (Su 2022).

Figure 6.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, installation view in the Futur 21—kunst industrie kulture festival, LWL Industrial Museum Henrichshütte Hattingen © courtesy of the artist. Photo by Katja Illner.

These same currents of energy, caused by meteorites melting in the Earth’s atmosphere are likened to the energy flows inside the blast furnace. The narrator remarks that this is a place in which time stops “in the rhythm of man eating coal and coal eating man, creating a sea of forces (which) rush together” (Su 2022). As the on-screen filmmaker pours over Lin’s writings, it is revealed that Lin did not return to China following the dismantling of the blast furnace. Her disappearance in 1989 is met with public amnesia, not unlike the events that unfolded in China, during the spring of that same year. In our interview, Su shared that, like the fictional Lin, the real male translator also remained in Germany, but was never heard from again.11

Challenging any linear conception of time, space, or politics, Su Yu Hsin excavates a bygone industrial history within the context of both Germany and China. Slow-moving shots over seemingly abandoned sections of this former labor-intensive, resource-depleting industrial complex expose structures now overgrown with moss and weeds, which quietly note the passage of time. Along with an abundance of archival images from the 1980s, Su shows great sensitivity towards this site’s local history of industrialization.

3. A “Thickened Present” of Ruins

Christine Ross attributes such sensitivities to time as attending to a “temporal turn,” motivated by “discontinuous time,” in which “the temporal category of the present is thickened by its proximity to the past and to the future” (Ross 2012). Much like Ross’ description of fellow Berlin-based artist Tacita Dean’s time-based works, Su underscores the “progressive stance of the modern regime of historicity” responsible for the transformation of this factory-turned-museum (Ross 2012). Through the artist’s own semi-documentary approach, Blast Furnace No. 2 is located within a present marked by ruins. The presence of ruins shapes one’s relationship to memory” (Ross 2012). Wu Hung describes ruined images as embodying a “suspended temporality” matriculating in-between time (Wu 1999, 2008). No longer operating on a progressively moving, forward trajectory, I propose that, like the death and subsequent explosion and material dispersion of a star, within the ruined spaces of this factory-turned-museum, time located within the museum becomes cyclical, meandering without a beginning or end. A closed loop forms between the past and the present. Memories of this former factory space no longer exist outside the new context of the museum. At the same time, we cannot look at these dilapidated remnants of the past without attempting to mentally reconstruct what they may have looked like during their height of operation. Thus, incorporating ruins into her visual vocabulary, Su highlights a cyclical present in suspension, where both memory and amnesia form amalgamated versions of one another.

A similar type of post-industrial ruin comes from former Soviet-born filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker. Stalker is an adaptation of the novel Roadside Picnic, which follows an illegal guide, known as a “stalker,” who accompanies a writer and a professor into a post-apocalyptic wasteland referred to as “The Zone”. A classic evocation of disjointed time, Stalker’s visual landscape reveals an industrialized zone simultaneously out-of-time with industrialization, a locale in which modernization can no longer modernize and capitalism can no longer capitalize. Space operates in a discontinuous fashion, as illustrated by moments in the film where two of the three protagonists travel through a tunnel, leaving the third man behind, only to unexplainably discover him waiting for them on the other side. While Stalker is most often described as a science fiction film, Tarkovsky discards traditional sci-fi representational elements in favor of the decaying, the rusted, and the ruined. The scholar John A. Riley refers to this dystopian environment as the product of a “repressed past and failed future” (Riley 2017).

When talking with the artist, Su described a kind of “material flow” of movement throughout the site (Figure 7). Water, air, and other elements seemed to exist in a somewhat anachronistic way. A museum website describes pre-recorded voices of former workers broadcast over loudspeakers, revealing uncanny evocations of the past.12 If we imagine these voices as ghosts of history, we might consider new ways in which they themselves transcend the boundaries of material time.

Figure 7.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, Video Installation (still), courtesy of the artist.

4. Mining the Past: Richard Serra and Clara Weyergraf’s Steelmill/Stahlwerk and Hilla and Bernd Becher

To provide additional understanding of these voices from the past, Su examined the 1979 documentary film Steelmill/Stahlwerk made by artist Richard Serra in collaboration with writer and art historian Clara Weyergraf.13 Ten years before the dismantling of Blast Furnace No. 2, Serra compiled a series of interviews with workers from Henrichshütte Iron and Steel Works as they engaged in the process of fabricating his CORE-TEN steel sculpture Berlin Block (for Charlie Chaplin).14

In a fall 1979 issue of October Magazine, Serra described ways in which the labor of steel workers is often romanticized, adding, “… having some admiration for the working class, I thought I was going to find the healthy, happy, heroic German worker who lived for his work. In fact, I found a situation that probably hasn’t changed for two or three centuries… It’s like an enormous cavern, tremendously loud. I was there at one time for three days straight, and on the fourth day I could hardly hear” (Michelson et al. 1979). Serra also recalled that these workers “have no sense of self-esteem. They are reduced to a dehumanized function necessary to the world economy, and no one examines it” (Michelson et al. 1979).

The documentary itself begins with an interview between Clara Weyergraf and several unnamed workers. To protect worker anonymity, the conversation is transcribed into text which appears against a black background. Speaking in German, Weyergraf first poses a series of practical questions about accident rates and the affects labor has on their bodies and overall health, along with trade-union issues. At one especially poignant moment, a worker states, “…the noise reaches 118 decibels… I’m slowly going deaf, for sure”. He also describes the physical dangers of working in the factory, in addition to examples of mistreatment by management. Weyergraf also invites more speculative reflection regarding the “significance” of factory work, one’s definition of freedom, and speculative thoughts on the future. In their responses to Weyergraf’s questions, workers do not see their future as independent from the factory labor they perform. One worker sees his future as inextricably connected to his workplace, asking out loud, “when there’s no more work, where will we go?” They exist within an exploitative system in which factory owners pocket most profits, leaving them little agency to imagine any alternative. When asked what they might change in their life, a worker sharply replies, “I wouldn’t know”.

In the subsequent October interview, Serra mentioned that an independent German camera team was hired to document the making of the steel sculpture. He noted that the crew “shot beautiful images of the mill, and then the workers appeared, it was in such a way that they seemed heroic. They looked like what the cameraman wanted them to look like—heroes; big, happy German workmen” (Michelson et al. 1979). The interview ends with Serra himself questioning “to what degree are we involved with making propaganda? And how conscious are we of it?” (Michelson et al. 1979). According to an exhibition catalogue produced by Kunstmuseum Basel in conjunction with the exhibition Richard Serra, Films and Videotapes, the artist moves “towards reality with the aim not of portraying this reality but of shaping it”.15 As underscored in Steelmill/Stahlwerk, Serra’s initial nostalgic assumptions about the lives and working conditions of factory workers were challenged by realities he faced during his time spent in the factory. In a similar vein, Boym writes, “(n)ostalgia… is an abdication of personal responsibility, a guilt-free homecoming, an ethical and aesthetic failure” (Boym 2001).16 Keenly aware of the museum’s romanticization of its own history (and perhaps even its failures), Su’s observational lens is an important counterpoint to Richard Serra’s. In our conversation, Su noted an important phenomenon as she herself moved through the factory-turned-museum—silence (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, Video Installation (still), courtesy of the artist.

As part of the research and development process for Blast Furnace No. 2, Su, like Richard Serra, spent time interviewing former workers about their experiences working in the factory, along with their memories of the blast furnace (Figure 9). She learned that several former workers are now employed by the museum as tour guides. Through these interviews, Su ascertained what she terms “virtual images of the past,” through the workers’ descriptions of factory conditions and labor practices. Su discovered that these so-called virtual images conflict with the museum’s desire to both preserve and promote the space as an important site of German national heritage. For example, Su notes that while the current site is like a serene memory capsule, during its operation, just as Serra mentioned, the factory was so loud that many workers she interviewed describe serious hearing loss as the result of long-term exposure to machinery and lack of effective PPE. Thus, these former workers themselves engage in a kind of nostalgia for Germany’s industrial past, hoping to sustain their own connections to place and its role in creating a sense of national identity and belonging. At the same time, they hold a kind of nostalgia for a time that may have never existed at all.

Figure 9.

Shooting day at LWL Industrial Museum Henrichshütte Hattingen. Photo by Su Yu Hsin.

The rehabilitation of these ruins supports collective identity formation. According to Su, some workers commented that young people no longer understand their roots, and these same workers believe it is their responsibility to help remember and preserve the history of this former industrial site. Yet their own proximity to this region’s history suggests a kind of amnesia towards the scars left by capitalist industrial extraction within this region.

Of course, Su Yu Hsin is not alone in such an undertaking, as similar investments are reflected in the documentary photography of 20th-century German artists Hilla and Bernd Becher. This husband-and-wife duo embarked on a large-scale documentation project throughout the outbreak of the coal crises which began in 1959 (Parak 2021). Together, they photographed structures, including blast furnaces, which included Henrichshütte, during a time when many of these buildings and edifices were slated for demolition or permanent closure (Parak 2021). Like Su, the Bechers’ work reflects a commitment to remembering amidst processes of transformative industrial and environmental change. The Bechers’ photographs are permeated with a sense of impending loss. These images illustrate the Bechers’ interests in remembering sites (and histories) otherwise slated for permanent erasure. For example, a Becher photograph of the Henrichshütte Ironworks taken in 1988 includes Blast Furnace No. 2 merely a year before it was dismantled and shipped to China. While it is unlikely that the Bechers knew the future fate of the blast furnace, their photograph takes on new meaning as a memorial of sorts—remembering a time and place that no longer exists.17

Within a contemporary context, the production of coal in China, a so-called “solar energy of the past,” as mentioned in Blast Furnace No. 2, has accelerated since the 1990s. China’s industrial history follows an even longer trajectory. Following the Soviet model, in October 1954, China’s first Five Year Plan was promulgated. A total of 156 industrial projects were formally announced, including iron and steel mines, the construction of electric power stations, factories for industrial and agricultural machinery, coal plants, oil companies, and other industrial development. The careful study and copying of Soviet practices resulted in the construction of the Shanghai Diesel Factory and the Shanghai State Factory of Electrical Equipment. Soviet experts also helped Chinese engineers and tradespeople develop chemical equipment, medical institutes, and hospitals, and clinics, as well as electricity and radio stations. In total, over 20,000 Soviet advisors and experts participated in knowledge-exchange programs with their Chinese counterparts (Shen 2020).

According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the country recorded its biggest increase in total energy consumption and coal use in a decade in 2021.18 It is reported that China is the world’s largest producer of coal domestically and the largest financier of coal-fired power plants abroad.19 Simultaneously, in a 2020 speech at the annual meeting of the United Nations General Assembly, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged that his country would adopt aggressive climate targets to achieve what he called “carbon neutrality before 2060”.20

Around the same time the Chinese company traveled to Henrichshütte to oversee the dismantling of Blast Furnace No. 2 in 1989, Germany vowed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent by 2050 (Bluma et al. 2021). However, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian natural gas deliveries into Europe have been dramatically reduced. As a result, Germany has turned to coal, resurrecting at least twenty coal-fired power plants nationwide, which provide energy during cold winter months.21 Yet, when visitors walk through the complex at Henrichshutte, they activate a nostalgic industrial fantasy, instead of grappling with the harsh realities of coal and steel production within Germany and beyond (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Su Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, Video Installation (still), courtesy of the artist.

Figure 11.

Yu Hsin, Blast Furnace No. 2, 2022, Video Installation (still), courtesy of the artist.

5. Conclusions

Blast Furnace No. 2 excavates the past, present, and speculative future in tandem with one another. The video combines concurrent links and continuities such as the Blast Furnace’s connection to cosmic histories, as well as the history of industrial labor and extraction-based economies. The project places particular emphasis on the future and elements of utopian nostalgia within modern global industrial production and development. The video, much like the museum, looks towards the future, while also projecting a sense of yearning towards a heroicized picturing of the past. Su sees the museum’s collection of minerals as her collaborators. They underscore time as non-linear, embodying ways in which the past is seen in the present, while at the same time connecting to the future.

To further highlight the video’s prescience, on 17 January 2023, police briefly detained Swedish climate activist Greta Thurnberg for her participation in a protest over the controversial expansion of coal mining in Lützerath, located only 62 miles from Hattingen (Figure 12). The resurgence of coal mining, despite an October 2022 announcement by the German government of closing all coal mines by 2030, further underscores Su Yu Hsin’s visual evocations of a non-linear past, present, and future. Su offers a critical intervention of sorts, contemplating the fate of workers and the harsh reality of factory conditions within the context of both our changing global climate due to human activities, as well as Earth’s planetary health, affecting future generations of humans, organic plant matter, and other living beings.

Figure 12.

Police officers carry Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg away from a mine during a protest by climate activists in Lützerath, Germany. Image by Federico Gambarini via AP.

In the final moments of the video, the filmmaker provides the viewer with an ending that hangs in suspension. The narrator prophesizes that in the year 2050, the novel’s protagonist will return to Earth with a new “source of stellar energy”. Yet at the same time, recent events might make us question what kind of planet Lin will encounter upon her return.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | According to the festival website, the goal of FUTUR 21 was to “encourag(e) people to think about the future of work, sustainability and the climate crisis, the impact of digitalization, and the limits of growth and consumption”. https://www.futur21.lwl.org/en/ (accessed on 5 March 2023). |

| 2 | The physical blast furnace is known as Blast Furnace No. 2. Su’s research-based video installation is also titled Blast Furnace No. 2. |

| 3 | According to the artist’s website, Su Yu Hsin (b. 1989) “is an artist and filmmaker based in Berlin. She approaches ecology from the point of view of its close relationship with technology. Her artistic practice is strongly research oriented and involves field work where she investigates the political ecologies of water. Her work reflects on technology and the critical infrastructure in which the human and non-human converge. Her analytical and hydropoetic storytelling focuses on map-making, operational photography, and the technical production of geographical knowledge”. https://suyuhsin.net/About (accessed on 5 March 2023). |

| 4 | An echo of sorts, scholar Susan Stewart writes of nostalgia as “a sadness without an object, a sadness which creates a longing that of necessity is inauthentic because it does not take part in lived experience. Rather, it remains behind and before that experience. Nostalgia, like any form of narrative, is always ideological: the past it seeks has never existed except as narrative, and hence, always absent, the past continually threatens to reproduce itself as a felt lack.” (Stewart 1993, p. 23). |

| 5 | A rhizome is a concept in post-structuralism describing a nonlinear network that “connects any point to any other point”. It appears in the work of French theorists Deleuze and Guattari, who used the term in their book A Thousand Plateaus to refer to networks that establish “connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences and social struggles” with no apparent order or coherency. (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 7). |

| 6 | https://www.joergnitzsche.de/en/industrial-museum-henrichshuette.html (accessed on 5 March 2023). |

| 7 | https://www.nrw-tourism.com/lwl-museum-henrichshuette-in-hattingen (accessed on 5 March 2023). |

| 8 | See note 7 above. |

| 9 | See note 7 above. |

| 10 | The literal text reads, “With your own phantasy you can very good sensing a liveliness feeling of working life on the Henrichshütte. Particularly of the very many original recorded votes of former workers, you can hear over loudspeakers, one obtains a very intense feeling of work”. https://www.joergnitzsche.de/en/industrial-museum-henrichshuette.html (accessed on 5 March 2023). |

| 11 | In a 2023 interview with the artist, she revealed that she attempted to contact the real translator during her time in Hattingen but was ultimately unsuccessful. She added that he likely did not want to draw attention to himself or to his decision not to return to China following the successful dismantling of Blast Furnace No. 2. |

| 12 | See note 6 above. |

| 13 | Conversation with artist, 19 January 2023. Clara Weyergraf and Richard Serra have been married since 1981. |

| 14 | Berlin Block (For Charlie Chaplin), made in 1977, was Serra’s first forged sculpture work. After completion, it was installed outside the Mies van der Rohe–designed Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. The work is both a tribute to the actor Charlie Chaplin and a comment on the Cold War division of Berlin into two blocs. |

| 15 | Kunstmuseum Basel, in conjunction with the exhibition Richard Serra, Films and Videotapes. |

| 16 | Boym also quotes Michael Kamen, who writes, “nostalgia… is essentially history without guilt. Heritage is something that suffuses us with pride rather than shame”. See Boym, xiv. |

| 17 | I look to the scholarship of Terry Smith, who argues that contemporary art is “marked by art to come,” shaped by his definitions of contemporaneity. Smith expands by offering the idea that “contemporary art today is art driven by the multiple energies of contemporaneity, the art that figures forth those energies so that we can glimpse them in operation, the art that works to transform those energies in ways that keep our futures open, an art that draws us into commitment to what is to come. This is, of course, to return the question to the realm of further questioning, but to a specified set of questions and a framework of interrogation”. Terry Smith, Art to Come, 50 (Smith 2019). |

| 18 | http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/ (accessed on 5 March 2023). |

| 19 | See note 18 above. |

| 20 | President Xi Jinping said, “Humankind can no longer afford to ignore the repeated warnings of nature and go down the beaten path of extracting resources without investing in conservation, pursuing development at the expense of protection, and exploiting resources without restoration”. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/22/climate/china-emissions.html (accessed on 5 March 2023). |

| 21 | https://www.npr.org/2022/09/27/1124448463/germany-coal-energy-crisis (accessed on 5 March 2023). |

References

- Bluma, Lars, Michael Farrenkopf, and Torsten Meyer, eds. 2021. Boom—Crisis—Heritage, King Coal and the Energy Revolutions after 1945. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. [Google Scholar]

- Boym, Svetlana. 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Michelson, Annette, Richard Serra, and Clara Weyergraf. 1979. The Films of Richard Serra: An Interview. October 10: 68–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parak, Gisela. 2021. Pulser for preservation: Bernd and Hilla Becher and the role of photography in industrial heritage. In Boom—Crisis—Heritage, King Coal and the Energy Revolutions after 1945. Edited by Lars Bluma, Michael Farrenkopf and Torsten Meyer. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, pp. 211–26. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, John A. 2017. Hauntology, Ruins, and the Failure of the Future in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Journal of Film and Vide 69: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Christine. 2012. The Past Is the Present, It’s the Future Too. New York and London: Continuum International Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Zhihua. 2020. A Short History of Sino-Soviet Relations, 1917–1991. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Terry. 2019. Art to Come: Histories of Contemporary Art. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Susan. 1993. On Longing: Narratives of Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Yu Hsin. 2022. Blast Furnace No. 2. Hamburg: Video Installation. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 2008. A Case of Being ‘Contemporary’: Conditions, Spheres, and Narratives of Contemporary Chinese Art. In Making History: Wu Hung on Contemporary Art. Hong Kong: Timezone 8 Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung, ed. 1999. Transience: Chinese Experimental Art at the End of the Twentieth Century. Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).