Abstract

Tacita Dean’s art relies on the perception of liminalities, of moving in-between, of one medium unfolding into another through dispersed, “molecular” sensations, either subverting or augmenting impressions of art forms perceived on the level of larger, structural wholes. Arguing against the wide-angle perspective employed by media studies approaches and for a close-up analysis of an “affective intermediality” in Tacita Dean’s art, the author looks at the landmark exhibitions at the National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Royal Academy in London organised in 2018. The article singles out some of the individual works in the context of the exhibition as a work of art, and focuses on questions like the cross-media phenomenon of the “cinematic”, the affective performativity of the various dispositifs employed in her installations of celluloid films, the affordances of Dean’s signature aperture-gate masking technique, as well as the relation between narrative cinema experienced in a theatrical space and film as the medium of a visual artist. The essay concludes with a brief analysis of her gallery film, Antigone (2018), unravelling an allegorical journey through cosmic time and atmospheric landscapes, viewed as an ode to the “blind vision” of photochemical film and as a synthesis of key features of her intermediality conceived as a strategy for the re-sensitization of mediums by approaching one art from the point of view of another.

1. Tacita Dean’s Aesthetics: An Affective and “Molecular” Intermediality

In 2018, in three simultaneous and coordinated exhibitions (Still Life, Portrait, and Landscape) hosted by the National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Tacita Dean presented works in a variety of mediums that initiated a stimulating dialogue with genres of painting associated with these prestigious institutions. In some cases, Dean’s own works were displayed alongside a carefully curated selection of pictures, and all in all, painting emerged undoubtedly as the primary partner in these dialogues. Beyond a versatile and ambivalent relationship between moving images and traditional forms of visual arts, much debated by critics at the time, what these exhibitions highlighted as essential features of Dean’s art was a diverse, material, and phenomenological exploration of intermediality itself, and at the same time, perhaps in a less ostentatious way, a persistent confrontation between two different kinds of moving image experiences, theatrical cinema and the exhibited gallery film. In what follows, I would like to examine this subtle, two-tier provocation underlying Tacita Dean’s oeuvre as a whole that we could see here, i.e., regarding the perception of intermediality in general and more specifically, regarding the rarely scrutinised relationship between narrative cinema and celluloid film as the medium of the visual artist.

First, I have found that Tacita Dean—working in film, photography, drawing, painting, printmaking, collage, moving image installations, etc.—continuously challenges our understanding of how intermediality “works”. Her experiments with the juxtaposition of these mediums can make us aware of the limitations of a theory of intermediality rooted in media studies, which for the most part ignores aesthetics and the perceptual qualities of art. Lev Manovich has rightly pointed out that “the concepts of beauty and aesthetic pleasure have been almost completely neglected in theories of media” (Manovich 2017, p. 9), and following suit, we may add, much of the theorization of intermediality (conceived as a research area of media studies) has also steered away from aesthetics, both from its pursuit of questions relating to beauty and from its focus on the senses. In this latter respect, we tend to forget that the etymology of the word shows that “aesthetic” is primarily inherently bound to “sensuous”. As Manovich also reminds us, the word comes from the ancient Greek aisthetikos, which meant “sensitive, sentient, pertaining to sense perception”, and “was derived from aisthanesthai, meaning I perceive, feel, sense’” (Manovich 2017, p. 9). Dean’s intermediality always foregrounds first and foremost a particularly engaging aesthetic understood like this, folding together sensory experiences of different arts.

Instead of making us think in terms of transmediations, media representations, or any kind of semiotic “operations” taking place between so-called qualified media types (Elleström 2014), Dean’s oeuvre prompts us to think in terms of an “affective intermediality”. It invites us to observe the unique sensuous excess and the complex affective performativity of each work and thus to take a step further in the alternative direction opened up by writings that have strong connections with phenomenology and post-structuralist philosophies of art.1 If intermediality is predicated in such writings on a visible display of the in-betweenness of media, associating it with the idea of “affect” complicates it even more, as it leads us towards new areas of in-betweenness, reaching beyond media, representation, text, and even beyond us, humans. Gregory Seigworth and Melissa Gregg summarise how this notion is understood in so-called affect theories in this way: “Affect arises in the midst of inbetween-ness: in the capacities to act and be acted upon […] affect is found in those intensities that pass body to body (human, nonhuman, part-body, and otherwise), in those resonances that circulate […] in the very passages or variations between these intensities and resonances themselves”. (Seigworth and Gregg 2010, p. 1) Thus, we could say that instead of the wide-angle, “molar” perspective of media theorists who have elaborated comprehensive concepts and taxonomies clarifying the implied relations in intermediality, considering the affective aspects of intermediality introduces a more elusive, precarious, “molecular” dimension that underlies (and even undermines) the larger framework. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s metaphors (i.e., “molar” versus “molecular”, borrowed from the natural sciences) seem appropriate in this case because they denote a similar shift in perspective (from organised structure to multiplicity), and furthermore because “molecular” belongs in their vocabulary to the order of affects, “the tiny perceptions or inclinations that destabilise perception as a whole” (Conley 2010, p. 178). As such, “affects are becomings” (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 256), they write, corresponding to a molecularity (and a so-called “desire-machine”) “operating by nonlocalizable intercommunications and dispersed localizations, bringing into play processes of temporalization, fragmented formations, and detached parts, with a surplus value of code” (Deleuze and Guattari 1983, pp. 286–87). If all of this might sound equally abstract at first sight, Laura U. Marks’s Deleuzian analyses may convince us otherwise. In her book entitled Hanan al-Cinema (Marks 2015), Marks unravels beautifully how the affective fabric can be woven through the dialectic between “molar” structures and “molecular” phenomena in experimental cinema and media art. The subtitle of the book, “affections for the moving image” calls attention to a very important starting point that we should bear in mind for this kind of intermedial exploration as well. Although affect theorists usually distinguish between affect and emotion (the former being considered pre-personal, unbounded, and therefore autonomous,2 while the latter denotes personal experiences3), Marks’s subtitle suggests that before we can say anything about the affective intensiveness of images, we need to acknowledge our own fondness for the medium and also the artists’ own affective/emotional engagement with their work. From an affective perspective, text can never be divorced from context. Art is always created and “comes alive” for its beholders in an intense, affective milieu.

In the case of Tacita Dean, it all starts with Dean’s own affection for her mediums, above all for the traditional, photochemical film that she has grown fond of and continuously used since her youth and that she has passionately campaigned for in order to save it from oblivion and obsolescence at a time when our culture is pervaded by digital technologies. The tactility and physical proximity required by shooting and processing analogue film is something Dean extends to all of her mediums, which she moulds, edits, and makes her own through laborious, intense, and time-consuming manual work and corporeal involvement (e.g., devising and setting up her camera with special filters; travelling to distant places in the world and patiently waiting with camera in hand to capture rare natural occurrences; overlaying paint, photography, writing; or collecting, transforming found images, etc.). The publicity photos4 or documentary footage of Dean that usually show her bending over and gently touching the surface of her pictures as if caressing a delicate creature,5 may remind us of a line from Jean-Luc Godard’s 1982 film, Passion, in which—superimposed on images of a film set reproducing paintings as tableaux vivants—one of the protagonists observes that “ultimately, work is the same as pleasure; it has the same gestures as love”. In all her filmed interviews, when Dean is talking about her work, her face lights up in a most radiant smile, often followed by an infectiously sprightly giggle and vivacious gestures of the hand, indicating a real passion and enjoyment in being engaged in the creative process. Yet, paradoxically, her art is suffused with a deep sense of melancholy. “All the things I am attracted to are just about to disappear”—she once said, and the statement has become perhaps the most often reproduced quotation from her (e.g., Adams 2018). She speaks here not only about her concern about the abandonment of analogue film in the digital age but also about being captivated by people mysteriously vanishing (e.g., Girl Stowaway, 1994; Disappearance at Sea, 1996), by the passage of time (e.g., Fernsehturm, 2001), by the twilight years of artists tinged with a sense of imminent loss (in her filmed portraits), or by glimpses of fleeting optical phenomena (solar eclipse, the green flash appearing at sunset over the sea, the mirage of Fata Morgana).

On the most elemental, pre-representational, “molecular” level, her ambivalent (both extremely joyful and mournful) affective/affectionate approach drives the way she reframes the idea of mediums outside the realm of technology. Dean believes that technologies have the tendency to become outmoded, while mediums can be timeless in the context of art.6 Her steadfastly experimental artistic practice is meant to reclaim the waning aesthetic effect of mediums and recover their pertinence to “sense perception”. This is why she insists on the plural form of “mediums” and not the Latin form of “media”, which has been appropriated and abstracted by media studies and also by contemporary colloquial speech, in which it is mainly used in reference to the convergent universe of digital media (and the press). “Artists use mediums”—she claims, not media, because “that word now no longer has any power […] So in order to retain the power of the materiality of artistic mediums, I’m pluralizing it” (Cuno and Dean 2019).7 In this way, her aim is not only to “re-empower the language” (Cuno and Dean 2019) to emphasise that each medium has its own distinct material substance but also to retrieve its essential non-transparency in art. The plural form of the word is indicative of her gestures towards what Annie Van den Oever (2015) defined as a kind of “experimental media archaeology”, i.e., a re-sensitization intended to literally re-aestheticize and salvage the affective potential of her media (of all her media, not just film). Her strategy for pursuing this re-sensitization can only be described as intermedial, as it relies on the perception of liminalities, of moving in-between, of one medium unfolding into another through dispersed, “molecular” sensations, either subverting or augmenting impressions of art forms recognised on the level of larger, structural wholes. In what follows, I will take a closer look at some of the works in the context of the 2018 exhibitions, which offered a comprehensive synthesis of her art, and I will trace some of these movements in which we see the mutual revitalisation of film and the visual arts through their intertwining as well as through their association with the “cinematic”.

2. Between the Visual Arts and the “Cinematic”

Somewhat paradoxically, in launching a veritable crusade fighting for the survival of analogue film, Dean identifies essentially as “more of a visual artist than a filmmaker” (Carvajal 2007, p. 51) and refuses to show her films in cinemas because that would be “just inappropriate and wrong” (Carvajal 2007, p. 52). This firm commitment is partly motivated by the intention to confer the prestige of the visual arts on a medium threatened by the disappearance of its material support (celluloid film) and by the marginalisation of its experimental use. In a short summary of her first major works, Peter Wollen noted in the same vein that “the word ‘artist’ sometimes seems to carry more prestige than ‘filmmaker’” (Wollen 2000, p. 107), but decided to dismiss this distinction as not very helpful with regards to Dean, writing that she is both a filmmaker and an artist making films. However, as the triple exhibitions mounted in 2018 may eloquently attest, the relationship between filmmaking (a concept associated with the art of cinema) and using film as a medium related to the other arts is far more complex than this in Dean’s oeuvre and is worth examining more closely. There is undoubtedly a clear strategy to consolidate the elevated status of celluloid film as an artist’s medium, reinforced by the prestigious locations of the exhibitions. Still, if we look at her versatile activity, we will see that it is not just film that is elevated or placed centre stage here, but first of all, the rarefied interplay between still and moving images, between traditional art forms, genres, narratives, and various aspects of cinema. Furthermore, what is most constantly highlighted through these interplays is that elusive quality that can traverse a painting, a photograph, or an art installation that we may perceive as “cinematic”.

Theorization of “the cinematic” (also referred to as “cinematicity”) moves between denoting “a close affinity to […] filmmaking and film exhibition”, or seeing it as a mere “sense of cinema” grasped through “the qualities and traces of cinematic creation and perception: a mode of mind, method, or experience” (Geiger and Littau 2013, p. 3), which can be interrelated with and detected in “a broad range of art forms and expressive modes”, including those preceding the invention of cinema and extending beyond the era of photochemical film (Geiger and Littau 2013, p. 8). This sensation of the “cinematic” is not derived solely from the experience of theatrical cinema or of moving images captured on film but also from a wider array of images in motion, before and after cinema. What is more, we could say, borrowing once more Deleuze’s metaphors, the “cinematic” can materialise within another art form on a “molar” level (by connecting with cinema as an organised whole, as a mode of being, not as a process of becoming, by adopting or containing elements suggestive of the structural units or the production process, i.e., the methodology of filmmaking, scriptwriting, the projection of a movie in a dark theatre hall, genres, narratives, and styles), and it can be perceived as a sensuous, “molecular” process of becoming (of becoming like a moving image), of introducing a sensation of ambivalence or oscillation between different mediums.

In Tacita Dean’s multimedia art, the “cinematic” unfolds on both levels, sometimes simultaneously and through an inventive variation of the dynamics that Marks defined as “pitting the molecular against the molar, or small-scale, local sensations against large-scale, accepted representations” (Marks 2015, p. 299). This could already be seen in one of her first series of large chalkboard drawings, The Roaring Forties: Seven Boards in Seven Days (1997), in which she established a generic link to the world of the movies with a play-on-words title alluding to the heyday of classical cinema. With her handwritten notes added to the sketches of maritime scenes, she treated the surface literally as a blackboard, doubling as a storyboard used to outline key sequences of a cinematic narrative. The large drawings invited associations with epic narratives across several media (film, seascape painting, literature/mythology), while also “drowning” such narratives in the vibrant details, blurring the perceptual threshold between graphic arts and film.8 In a similar way, Dean scribbled notes resembling film directions referring to lighting, camera movement, and sound over the photogravures remediating postcards foraged from flea markets in the series The Russian Ending (2001).9 The title evoked an early twentieth-century practice (especially popular in Denmark) of creating films with an alternative happy ending for Americans and Western Europeans and a sad finale for Eastern European and Russian audiences and, accordingly, suggested possible scenarios of doom.10 Her photogravure series, Blind Pan (2004) that could be seen in the Landscape exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, before entering the room showing her gallery movie, Antigone (2018), looked like drawings made in preparations for a film about Oedipus, with inscriptions hinting at the mythological narrative while having the same palimpsestic quality oscillating between the painterly, the photographic, and the cinematic.11

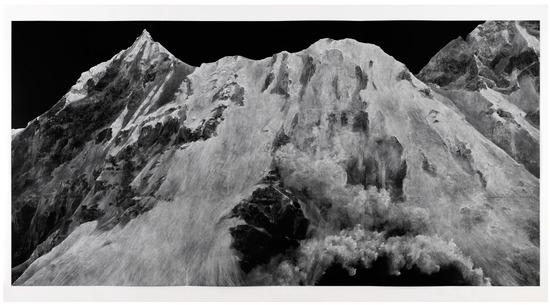

Dean’s tendency for creating series instead of single works shows not only her robust productivity but is symptomatic of a deep affinity with thinking in cinematic structures even without further cinematic references, adding the dimension of temporality to the images. In the Landscape exhibition, there were several such drawings on slate made in 2018 with a combination of spray chalk, gouache, and pencil (their titles quoting Shakespeare: Wind, Thought, Swifter Things; the triptych, Bless our Europe; Wished in Silence; Be Calm, Good Wind, Blow not; Verily, etc.), alongside a vast chalk drawing on blackboard covering an entire wall, titled The Montafon Letter (2017)12 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tacita Dean: The Montafon Letter (2017). Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

These drawings (associated with Shakespeare’s poetic words) looked like painterly photos made in the style of Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents (1922)13 series of cloud photographs, and as such, they appeared as variations of Dean’s earlier series of hand-drawn, multiple-layered lithographs exhibited in New York in 2016 with the Shakespearean motto, “…my English breath in foreign clouds”.14 They provoked the viewer to assume the artist’s position when she affectionately brushed the boards with her hands, to lean close and decipher the snippets of texts inscribed on the panels, which definitely read as personal imprints of Dean’s hand, mood, and flashes of thought but did not convey an explicit narrative (like in a detail of The Montafon Letter below, see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Tacita Dean: The Montafon Letter, detail (2017). Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

The visitor had to take time to appreciate the variations in the smaller drawings and to scan the vast surface of the monumental chalk tableau, despite the seriality and large format of the pictures suggesting viewing from a distance. The immersive experience was similar to that of the contemplative slow cinema of the likes of James Benning, whose successive long takes in Ten Skies (2004),15 for example, require an intermedial sensibility that recognises the delicate balance between film and photography. Dean drew the hovering, ethereal formations of clouds, vapours, or the superb snow slide by alternating crisp details and impressions of soft focus produced through multiple light touches and erasures. In this process, as described by Ed Krčma, writing about The Roaring Forties, Dean dramatised the “work of erasure, the insistent visibility of which announces their shared attachment to […] temporality, materiality, and bodily investments” (Krčma 2010). It stimulated a mobile, cinematic, and tactile gaze and lured this gaze to stay on a “molecular” level and to recognise the delicate mutations in forms covering or laying bare the slate beneath the pigments, thus effectively “cine-aestheticizing” the medium of chalk drawings.16

The 2018 National Gallery exhibition, Still Life, employed this interaction between different levels of cinematic perception across the arts in another way. Dean acted here mainly as a curator17 and filled the space with pictures of other artists that appealed to her and resonated with her films.18 Walking around the two rooms, more than in any of the other two companion exhibitions, there was an unshakable sense of seeing in the associations the emergence of a cinematic montage in which each isolated picture assumed new meanings and exhibited an exchange of media sensations in conjunction with the others. At first sight, one was tempted to think that some of the works were chosen to demonstrate changes in the symbolism of recurring motifs depicted in still life arrangements. Undermining such a cerebral discourse on art history, there was a staging of a much more consistent conversation between fine details leading the eye along lines, circles, colours, light, shade, and texture, foregrounding visual forms, and the absence of people in a series of chameleonic pictures that deceived the eye. We saw this, for example, in the empty plastic punnets basking in the sunlight on a window sill in Wolfgang Tillmans’s photo, Beerenstilleben (Berry Still Life, 2007),19 hardly distinguishable from a photo-realist painting (especially being placed next to a painting by Francisco de Zurbarán); in a banal rubber band thrown on two stacked plates in Thomas Demand’s Daily #13 (2011):20 a conceptual photograph of a trompe l’oeil sculptural reproduction in paper of an everyday image, or in a roughly sketched oil painting of a wide-brimmed hat on a wooden fence by Philip Guston (1976),21 which looked like a blackboard drawing. Whereas Dean’s own series like The Roaring Forties or The Russian Ending recalled well-known narratives or film genres, adding coherence to the disparate pictures through allusion, the varied pictures brought together for the Still Life exhibition did not offer easily identifiable correspondences with familiar structures or narratives. With the artworks distributed on the walls with lots of spaces in-between, the “montage” effect resembled that of a slow, essentially non-narrative film, in which the viewer could pore over each part at leisure both individually and as a loosely connected network. The viewer could contemplate “the exhibition itself as a work of art”, as the art curator and theorist Hans Ulrich Obrist wrote (Obrist [2014] 2015, p. 159) in admiration for Jean-François Lyotard’s 1985 show, Lés Immatériaux, organised in a way to produce ideas rather than merely illustrate them, creating paths “to awaken a sensibility” (Obrist quoting Lyotard’s catalogue description, Obrist [2014] 2015, p. 158). Dean’s exhibition did not deliver cathartic revelations about still life, but it did quietly deconstruct it through the dual unravelling of “stillness” and “life” in painting, photography, and film, ultimately bringing forth, in conjunction with the genre’s focus on transience, a “cinematic” sensibility across the arts and an ensuing cross-medial intensity, which animated the whole show.

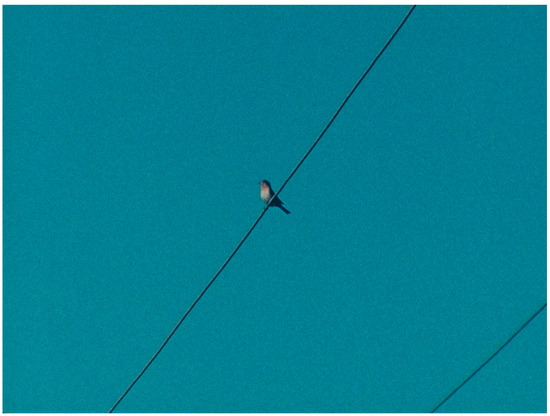

There were only three films by Dean, discreetly placed among the other works, but these were all crucial for the emergence of this “cinematic” undercurrent of the exhibition. Despite being frameless in a room full of framed pictures of various sizes, the display of these films was not cinematic but assumed the tableau form of their neighbouring paintings and photographs, with no separate, darkened space of their own and no seats in front of them for the audience. All of them were projected at a much smaller size than a regular cinema screen. The shimmering moving images provided a contrast to the enclosed stillness of the paintings and photographs. They added the impression of “life” next to the static pictures, many of which represented dead animals, reminding the viewer of the more sinister connotation of “still life” in painting (also referred to as nature morte), traditionally composed as an allegory of the ephemerality of life.22 The most remarkable contrast was provided by the photographs of a pair of taxidermized white owls by Roni Horn entitled Dead Owl (1997),23 above which, in a diagonal line, in Dean’s playfully titled Ear on a Worm (2017) (Figure 3), a tiny bird, perched on a power line, chirped and chirped under a clear blue sky before suddenly diving and disappearing from sight. The counterpoint of the dead owls to the singing bird (flanked on either side by two paintings and a photograph of fettered, caged, and dead birds), the photographs, and the moving image exhibited the palpable difference between not so much the two visual art forms as what we perceive as “photographic” and “cinematic” (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Ear on a Worm (2017), film still. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

Figure 4.

Tacita Dean Still Life exhibition at the National Gallery (2018), installation view of Ear on a Worm (2017) with Roni Horn’s Dead Owl (1997). Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

As the volume edited by David Campany (2007) on the subject has proved, the phenomenology of the “cinematic” can never be defined separately from the “photographic”. Continuing a long line of theorising started by André Bazin’s ([1958] 1967) ideas on the photographic embalming of reality and Roland Barthes’s ([1980] 1981) description of absence as presence in photography, Vivian Sobchack writes that the photographic materialises and preserves “a present that is always past” is connected to death, and are “ethical investments of nostalgia” (Sobchack 2016, p. 101). Conversely, “although dependent on the photographic, the cinematic has something more to do with life and with the accumulation of experience—not its loss. Cinematic technology animates the photograph and reconstitutes its materiality, visibility, and perceptual verisimilitude in a difference not of degree but of kind. The moving picture is a visible representation not of activity finished or past but of activity coming into being” (Sobchack 2016, p. 101, emphasis added). Sobchack argues—referring to the image of the woman opening her eyes with a flutter of the eyelids, breaking through the stillness of the series of photographs in Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962)—that this “animation” or “activity coming into being”, can be nothing more than “the transformation of the moment to momentum that constitutes the ontology of the cinematic and the latent background of every film” (2016, p. 103). In Dean’s arrangement of the cluster of still and moving images, confronting photography and film, there was also a reversal; the looped film eventually emphasised—beside the transition to the momentum of the bird taking flight—the mechanical repetition of the one-time photographic recording. As Barthes wrote, “What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially” (1982, p. 4). While the strikingly uncanny, identical pair of the dead and stuffed owls placed below as a double testament to their “being-that-has been”, appeared as if someone had framed two still images from a series making up a film (their photographic stillness being thus transformed into the arrestedness of a cinematic frame24), and provoked the viewer, in Marjorie E. Wieseman’s words, to instinctively “glance from one to the other and back again, hoping to find in some (perceived) variation a flicker of movement of life” (Wieseman 2018, p. 191).

This flicker of movement was the main topic of a sublimely sensuous film presented in this exhibition, Prisoner Pair (2008),25 with another pun in the title (hinting at the French poire prisonnière, a name for the delicacy depicted here used in the region of Alsace-Lorraine, where the film was made) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Tacita Dean: Prisoner Pair (2008), film still. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

It showed a couple of ripe pears, each grown inside a bottle to release their fragrance into the schnapps poured over them. With a small nineteenth-century painting of green apples by William Henry Hunt hung next to it,26 Dean’s picturesque pears could be seen this time not as a contrast, but indeed as a mere pairing of two pears and two apples in two self-contained images (two pairs of imprisoned fruits). There was a palpable resonance of synesthetic perceptions across the arts and an effective cross-pollination between them, carrying the synesthetic “momentum” as it was “coming into being” from one picture to another. Like the pears, the fallen apples at the brink of decay seemed to breathe their dense aroma into a blurry background of rugged earth and moss. The film itself, which amplified the liveliness of the painting placed by its side, unveiled a serendipitous fusion of the “painterly”, the “photographic” and the “cinematic” in the image of the motionless pears held prisoners in the bottles, with the sunlight bouncing off the moving leaves, the small particles of fermentation floating in the soft blur of the liquid seen through the dirty glass, the light changing from brightness to darkness, the varying camera angles completing the array of moving elements with “the very movement of vision itself” (something that we always perceive as cinematic, according to Sobchack 2016, p. 101). The moving picture of the slowly decaying pears inside the bottle, encasing within its “molar” structure (i.e., within its enclosed “pictureness”) the movements of the eye and the sensual mutability of the world unfolding in time, could ultimately be perceived as a kind of self-reflexive metaphor both for the main idea of cinematic re-sensitization running through the entire exhibition and for the current condition of photochemical film: cut off from cinema, which organically nurtured it in the past, and being allowed to mature further in the context of contemporary art.

The third film work in the Still Life exhibition, Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting (2017) (a diptych with a painting of a gnarly tree by Paul Nash27 hung in-between the two unevenly small-sized screens), explored further the effects (and elemental affects) of cinematic animation contained within a pictorial form marked by immobility in a way that harked back to the beginnings of cinema. The silent, slightly overexposed, flickering black-and-white films were shot on location at the Henry Moore Studios and Gardens set in the Hertfordshire countryside. It showed close-ups of some weathered, pitted rocks from Moore’s collection and fragments of sculptures, with sharp light penetrating the holes, sometimes appearing as windows through which one could observe the blades of grass swaying in the wind and flies buzzing in and out of the camera’s off-focus areas. The diptych exhibited the fine reverberation perceived in-between art and life, form, and formlessness, inanimate and animate, in a minimalist, non-picturesque way (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Still Life exhibition at the National Gallery (2018), installation view of Tacita Dean’s diptych, Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting (2017), with a painting by Paul Nash (Event on the Downs, 1934) placed in-between. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

It encapsulated at the same time an image of “nature caught in the act”, as described by Nico Baumbach (2009) based on George Sadoul’s account of early filmgoers’ and, according to anecdotal evidence, Georges Méliès’s and D. W. Griffith’s fascination with “the trembling of the leaves through the action of the wind”, (Baumbach 2009, p. 374) seeing the novelty of the new medium, the special quality of being “cinematic” not in its ability to deliver visual surprises, or in the representation of people or moving objects, but in the incidental details of movements of the unspectacular, real world captured by the camera eye in the background or at the fringes of the frame. It also conveyed something of the essential ghostliness of the indexicality of film in the lively but lifeless imprint of life produced by the touch of light on photosensitive materials. This ghostly interaction between immateriality and materiality, chance imprint, and controlled framing, inherent to every stage of the process of photographic/filmic image creation, is something that is reproduced and multiplied in Tacita Dean’s multilayer prints,28 and in the films made with her special technique of aperture gate masking, some of which will be discussed below.

3. The “Battle of the Dispositifs” in-between Cinema, Film, and Installation Art

While the previous examples and the Still Life exhibition as a whole drew attention to the “molecular” disruptions of the universal structure of the painterly tableau by way of the “cinematic”, and drew on the sensuality and impermanence that we experience in intermedial phenomena, the films on show in its companion exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery and Royal Academy brought into the spotlight a productive interaction on another level between the different dispositifs of moving image projection: the art gallery film, cinema, and multiscreen installation art. In other words, there was a shift of emphasis from the “passages” in-between the images, in the sense Raymond Bellour ([1990] 2012) has theorised the so-called l’entre images intertwining moving images, photography, and the traditional arts,29 to the creative reconfiguration of the phenomenological, “material circumstances that constrained, enabled, and defined the viewer’s relationship to a film” (Radner and Fox 2018, p. 41), or, in Bellour’s words, to the “quarrel” or “battle of the dispositifs” (Bellour 2012).30

This aspect of Dean’s art involves questions that go beyond the performative role of the “cinematic” with regards to the perception of intermediality that has been discussed here and connect to questions at the core of the debates about the possible expansion of the concept of cinema itself. In Bellour’s view, beside the multiplication of image technologies and computers joining cinema’s old rivalry with television, the museum opening its doors to moving images has emerged as a “respectable, friendlier”, yet “much more devious” enemy. For in the museum, “cinema becomes on the one hand really an art […], on the other hand it transforms itself there into unfamiliar, endlessly mutating dispositifs, where it disappears to itself under the guise of reinventing itself” (Bellour [1990] 2012, p. 5). Bellour has argued that such reinventions in the form of gallery films and videos led to the emergence of “another cinema” (Bellour 2008) or even “multiple cinemas” (Bellour 2013). Countering this position (and playing on Bellour’s terminology), Erica Balsom prefers “to see in these developments an othered cinema”, meaning that “they represent a site at which the cinema has become other to itself”. It is as if the cinematic dispositif has been “shattered into its aggregate parts, which are now free to enter into new constellations with elements once foreign to it” (Bellour 2013, p. 16, emphasis in the original). Such works differ from cinema but also share elements and very often explicitly reflect on cinema, “exhibiting” it “in the sense that they hold it out to view or subject it to scrutiny” (Balsom 2013, p. 13). Tacita Dean’s films challenge us to an even more nuanced interpretation, which cannot be fully ascribed to either of these positions grappling with “this new, vague and ungraspable ‘other’” (Leighton 2008, p. 10). Bellour and Balsom view the problem from the vantage point of cinema, looking at what happens to cinema in the transformative environment of the museum, and from this perspective, Dean’s gallery film practice appears both as “other” and as a creative “othering”. Her films can be set against what Bellour sees as the unique experience of cinema, in a “battle” between different kinds of dispositifs, while also creating “new constellations” that adopt elements of cinema. Still, the distinctive feature of her approach is that she consistently flips this perspective. As we saw in the previous examples, despite being a staunch cinephile, she is primarily interested not in “exhibiting cinema”, but in “cinematizing the exhibition”, in seeing what happens to the other arts when they are permeated by the “cinematic”, and in treating analogue film as a medium on par with the visual arts and not as a technology historically linked to the movies. Consequently, all the films in the Still Life exhibition adopted the dispositif of the tableau pictures, displayed on the wall together with the paintings, enfolding a cinematicity echoed through painting and photography.

On first sight, the parallel show at the National Portrait Gallery almost literally implemented Bellour’s idea of multiplied cinemas by allotting individual rooms to each of Dean’s films. One of these was the elegiac short about the poet Michael Hamburger (2007). In the figure of the old man speaking in a trembling voice about his orchard and the autochthonous variety of apples discarded in the age of supermarket uniformity, Dean brought to the fore, once more, the sensuousness of the aromatic fruits as metaphors for the appreciation of life, art, and the old, outmoded medium of analogue film. In a cinema, this and all the other films would have lost much of their affective value through the conventional divide implied between reality and fiction at the distance of audience and screen. Here, however, Dean’s analogue films turned the museum environment into an uncanny space. In the small rooms, one was invited not to watch the films but to be in their company, next to the projection machines, visible, palpable, and audible in the same space. This invitation to “being with” instead of “looking at” resulted in an uncanny sensation generated by the proximity of the ghostly, life-sized moving portraits of people (accentuated by the way the screens suspended on thin wires appeared to hover in space instead of being attached to the wall) in an enclosed, artificially created space of intimacy (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Tacita Dean’s films uncannily inhabit the small rooms of the Portrait exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in 2018. Installation view of Providence, a filmed portrait of the actor David Warner (2017). Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

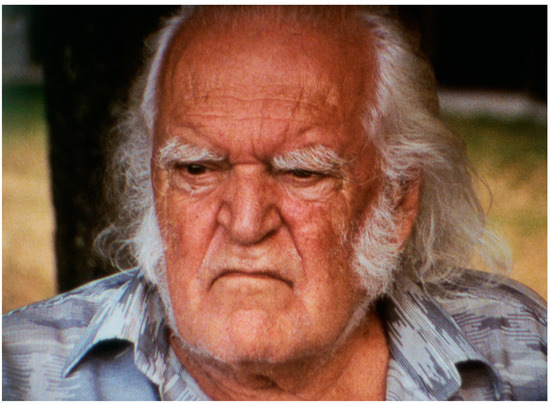

Furthermore, in Mario Merz (2002) and Portraits (a film about David Hockney, made in 2016), Dean deliberately posed their subjects as sitters, noticeably affected by the enforced stillness. Hockney, surrounded by his own portrait paintings, demonstrated an endearingly understated self-consciousness in front of the camera, smoking, coughing, adjusting his glasses sliding down his nose, and bursting into laughter, not being able to hold the pose for long. The portrait of Mario Merz, showing the ageing artist sitting under a tree unmoved by the play of sunlight over his rugged face, underscored his sculptural magnificence (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Tacita Dean: Mario Merz (2002), film still. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

This corporeality, set against light’s immateriality in the image, reflected the duality inherent to the whole exhibition. In each case, there was something more than the mere viewing experience of the film. Kate Mondloch has observed that in screen-reliant installation the art interface always matters (Mondloch 2010, p. 4); however, in this case, it was not only the objecthood of the screen or the “ambiance” created by the “projection as a luminous object” (Bruno 2022, p. 133) that appeared as a vital component of the artwork.31 Dean laid bare the symbiotic unity of the image hovering mid-air and the projector making a rackety noise in the background, so that the visitors were actually sharing the room with a delicate cine-sculptural assemblage rather than attending either a conventional screening or a radical experiment in expanded cinema. According to David F. Martin, the phenomenology of sculpture always “reveals our physical ‘withness’ with things, our ‘being-with’, much more vividly than painting” (Martin 1981, p. 28). Dean’s films activated this feeling of “withness” together with a keen awareness of the precariousness of the material components of the artworks, i.e., the rarely seen old-time projectors with the highly flammable celluloid film stock exposed to view and to unwanted touch, the beam of light that visitors had to avoid in their movement in the limited space lest they interfere with the projection over the shimmery screen. In each case, Dean’s characteristically affective, multisensory treatment of her subjects (her quiet observation of the passing of time, the discovery of vibrancy in the minutiae of everyday reality) had to be extended to the gallery space, too.

This intense feeling of “withness” and fragility was incorporated as an integral part of the architectural concept of Merce Cunningham’s performs STILLNESS … (six performances; six films) (2008), which consciously built on what Giuliana Bruno describes as “the architecture of projection”, “an atmospheric construction” where “as light ‘goes around’, along with spectators, a mutation of space is performed […]. The energy transmitted in luminiferous, projective ambiances, that is, creates not only a mutation of spatial conditions but also a psychic transformation, […] enhancing affective, relational atmospheres” (Bruno 2022, p. 133). In this particular installation, a larger room was populated by multiple screens and multiple 16 mm film projectors showing the frail, eighty nine year-old ballet dancer and choreographer, Merce Cunningham, being filmed while pensively seated in front of a wall-to-wall mirror, performing in this way, by being still, in John Cage’s composition 4′33″ (1952). In Cage’s original, provocative work, musicians stood in front of an audience without playing any music. Their (non)performance did not exhibit silence, but ambient noise and movement being imminent to stillness. Dean’s version included the whirring of the mechanical devices and the sounds of footsteps in a dark hall of mirrors in which the visitor had no choice but occasionally step in front of one of the projectors and thus cast their own silhouette onto the “moving still” image of the old man peacefully waiting for us to perform the “dance” choreographed by chance movements in the room prompted by the arrangement of the projectors and the large screens enfolding the full-scale human figures and their reflections (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Merce Cunningham performs STILLNESS (in three movements) to John Cage’s composition 4′33″ with Trevor Carlson, New York City, 28 April 2007 (six performances; six films). The silhouette of the viewer is projected over the image. Installation view photographed by the author at the National Portrait Gallery, Portrait exhibition, 2018. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

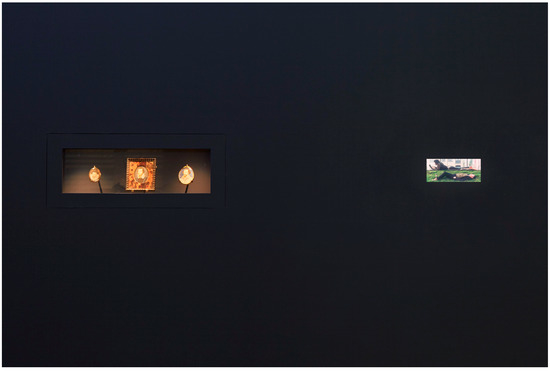

An even more daring dispositif was conceived for the film presented in The Portrait Gallery’s exhibition within the exhibition, which was titled, borrowing a line from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, His Picture in Little (2017).32 In this work, the visitors had the impression they could look at moving pictures at the diminutive scale of the film stock itself, shown with its backlit screen encased in the wall. These miniature portraits of actors who once played Hamlet (Stephen Dillane, David Warner, and Ben Whishaw) effectively challenged the idea that cinema should still be regarded as “the other” in the art gallery, reminding us of the historicity of Bellour’s ideas that he himself was fully conscious of at the time of surveying the state of the art(s) in his L’entre images. The film-frame-width strip of translucent moving images evoked and defied both the exquisite miniature faces painted in watercolour from the Elizabethan and Jacobean ages that were placed beside them as well as the commonplace, portable digital portrait galleries people store but seldom look at nowadays on their mobile phones. By situating film in-between painting and electronic images, Dean made the viewer conscious of the fact that cinema is no longer an automatic point of reference in today’s media landscape, where movies are mostly watched on electronic screens of all sizes, anyone can shoot pictures using their telephones, and there are digital applications for making still images painterly or “cinematic”. The enclosed small format emphasised the tiny picture as a portal to imaginary worlds, as “one of the refuges to greatness” (Bachelard [1958] 1964, p. 155). It enabled a special kind of immersion encoded in the traditional form of miniature paintings, which drew the viewer nearer, something that electronic devices have rediscovered and reshaped in their “mix of intimacy and possession” (Beugnet 2013, p. 206). Vivian Sobchack wrote: “as an object for our vision, a moving picture is not precisely a thing that (like a photograph) can be easily controlled, contained, or materially possessed—at least, not until the relatively recent advent of electronic culture” (Sobchack 2016, p. 104). Contesting this evanescence of cinematic images, Dean’s encased film offered a form of containment that resembled both the boxed-in pictures of pre-cinematic contraptions and the glass display cases in the museum. Moreover, in comparison, it made the viewer even more aware of the uncanny feeling of “being with” the other life-sized filmic portraits in their own rooms, where the precarious assemblage of the exposed technical apparatus revealed a fragility dependent on exclusive, site-specific forms of containment, control, and material possession as an indelible part of the viewing experience (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Tacita Dean: His Picture in Little (2017), encased in the wall next to miniature paintings from the late sixteenth century. Installation view, National Portrait Gallery, Portrait Exhibition, 2018. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

His Picture in Little showcased Tacita Dean’s distinctive process of filming that she invented, which consists in successively masking and revealing different parts of the aperture gate, each time rewinding the film in the camera, capturing multiple images in one divided frame. Here it allowed for the three actors to appear confined to solitude in different “cells” of the film strip, as if quietly passing the time while preparing to inhabit Shakespeare’s illusionary, poetic world (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Tacita Dean: His Picture in Little (2017), film still. National Portrait Gallery, Portrait Exhibition, 2018. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

The technique has been used by Dean many times, resulting in an extremely versatile template that also defined two of her most monumental works to date. Perhaps the most important, Film, commissioned for the Tate Modern in 2011,33 was deliberately devised as an installation, impressing the viewer with its singular dispositive, displaying a silent movie in the form of a towering film strip reaching up to the ceiling of the enormous turbine hall. In addition to masking and rotating the camera, Dean also intervened in the images through double-exposure and matte painting. Film was therefore not just a splendid homage to analogue film, conjuring up a wide range of playful experimentation with the medium from early cinema to avant-garde abstractions, but at the same time a magnified mirror of Dean’s tactile, intimately artisanal filmmaking.

Antigone (2018),34 which was the centre piece of the Landscape exhibition at The Royal Gallery, may be considered a companion piece of Film, one that stands out just as emblematic for her entire oeuvre and artistic creed. It integrated the key concerns of Dean’s art discussed here earlier: the “molecular” and “cinematic” sensitivity unfolding in the chalk drawings and “animating” the multimedia exhibition of Still Life, along with the creative focus on the reconfigured cinematic dispositifs that we saw in the installations at The Portrait Gallery. In this respect, it reinstated the productive interaction, i.e., the “battle” between theatrical cinema and film as a visual art, with full vigour on more than one front. The projection of the hour-long work in a traditional, theatrical form with the audience seated in a darkened hall in front of the screen encouraged expectations for narrative cinema. (Although the film was later projected as a two-channel installation too, at the Kunstmuseum Basel in 2021, a cinema-like viewing was endorsed even then, urging visitors to watch the film in its entirety from the beginning to the end.) These expectations were already there at the genesis of the work, in a failed attempt at writing a screenplay for a feature film. Living in Los Angeles, the “proximity to cinema production in Hollywood almost certainly contributed to the rekindling of my ambition to make Antigone, but it also complicated it”, Dean wrote (Dean 2018a, p. 97), hinting at the allure of moviemaking and the challenge to combine it with her own method of embracing the medium of film and all the “molecular” processes of intermediality that it affords.

She drew inspiration from her literary studies and, more importantly, from her deeply personal bond with classical Greek culture established through her father, who gave Greek names to all three of his children, naming her Tacita, her brother Ptolemy, and her older sister Antigone. Her closeness to the stories of Sophocles’s Theban plays was increased by the intriguing significance of her sister’s name and by the coincidence of being affected by corrosive arthritis, causing her to limp just like Oedipus, whose name referred to his swollen ankle, the symbol of his fate. Yet, the ancient Greek story itself functions only as a distant echo attached affectively to her family history and to the unwritten screenplay (both relegated to the unconscious). Although the title might suggest an adaptation of the eponymous third part of Sophocles’s trilogy, the film is about the period that falls in-between the first two plays, Oedipus Rex and Oedipus at Colonus, during which the banished and blinded king is imagined roaming the wilderness together with his daughter and sister, Antigone.

In-betweenness and blindness define the entire film as key notions intertwined and articulated in many ways. Firstly, there is this opposition between narrative and what is arguably “outside narrative”.35 We see no dramatic action, only the figure of a modern-day Oedipus, embodied by Stephen Dillane with a wavy grey beard, dressed in a long coat, walking through rocky landscapes and moorlands, lying on the ground, or sitting at a campfire. These scenes accompany images of the poet, Anne Carson (the author of a new English translation of Antigone), reading her own poem, TV Men: Antigone (Scripts I and II), readings from other texts, and a dialogue filmed in a historic courthouse in Thebes, Illinois, in which Carson, Dean, and Dillane reflect on the plays, acting as a kind of chorus. The overlapping voices together with the ambient sounds result in a polyphonic interweaving of words and images in which the rich texture of the soundscape rivals the complexity of the composite imagery. The musicality of verbal speech and the intellectual challenge of the fragmented philosophical musings fill the gap in between the Sophocles dramas by substituting epic literature with free-flowing poetry.

Similarly, the film draws on the dichotomy between the discursive visual structure of narrative cinema (where image is subordinated to storytelling) and the non-discursive affordances of films more closely allied with photography and the visual arts (characteristic of avant-garde practices). Despite its cinematic screening, Antigone is a film like no other: it is in fact composed of two 35 mm anamorphic films projected side by side, self-reflexively flaunting their specific medium with sprocket holes made visible on the edges of the frames. The arrangement spreads out a horizontal, “landscape” view in opposition to Film, which has chosen verticality for the majestic “portrait” of the celluloid filmstrip. Each of the conjoined films was shot with inventive variations of the aperture gate masking technique, dividing the frame into two or three parts in the shapes of semicircles, rectangles, triangles, and even that of a swollen ankle. The two rectangular frames are described as “left eye” and “right eye” in the transcript of the film (Friedli et al. 2022) and replicate the contour of the solar-eclipse viewing glasses worn by Dillane to symbolise Oedipus’s blindness.

The film offers a look into “the wonderful dark hole”36 of a world left in obscurity in the original plays, inviting the viewer, paradoxically, to see it through this double frame resembling Oedipus’s lenses. The two-channel vision therefore appears not as a reflection of an actual sight but more as an insight drawn from memory and from the heightened acuity of the senses granted to the blind. On the one hand, this may recall Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Romantic image of Homer standing at the threshold of worlds in his poem, Limbo (1834), and staring into the unknown with an “eyeless face all eye”, where “he seems to gaze at that which seems to gaze on him”. Oedipus’s blindness shared in the images becomes a form of expanded, affective, tactile vision, feeling the sculpturality of rocks, the warmth of light, the dynamics of movement, the sparks of fire, taking in the sensations of vapours, geysers, and all the sonorous world of living, throbbing, bubbling matter, stretching into universal time and space, culminating in the magnificent, cosmic reciprocity of a total eclipse: the blinding spectacle of the blindness of the sun observed through the filter of the blindness of film (Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 12.

Tacita Dean: Antigone (2018). Stephen Dillane as Oedipus wearing eclipse-viewing glasses in the first rectangle of the composite images. Installation view of the cinematic screening at the Landscape exhibition hosted by the Royal Academy in London in 2018. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

Figure 13.

Tacita Dean: Antigone (2018). The sensuous landscape “outside” the narrative. Installation view, Landscape exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, 2018. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.

Figure 14.

Tacita Dean: Antigone (2018). The emergence of the cosmic spectacle of the solar eclipse. Installation view, Landscape exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, 2018. Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Paris.37

On the other hand, Antigone is an elaborate ode to the “blind faith” (Dean 2018b, p. 166) involved in the mystery of photochemical film. In Dean’s (2018b, p. 166) words, “only the negative, deep within the darkness of the camera body, carries the secret to what has already been exposed on it”, and with the repeated covering up of different parts of the aperture of the lens, it becomes “a magical place of pictorial intimacy where one is bound together by chemistry”. Furthermore, with the introduction of the masks that partially blind the camera eye, Dean has found not only a way to increase the role of chance associations within the same, divided frame, producing, in Laura Marks’s words, affects unfolding through a “new connection that brings things into contact, makes a new fold” (Marks 2015, p. 212), but also a way to forge a form of “controlled serendipity” (Reid and Turner 2016). This meticulous fragmentation of the widened landscape format through the inlaid pictures reconfigures the familiar forms of split-screen cinema, multiscreen installation art, and collage in painting. The technique makes it difficult for the viewers to scan the screen as a whole and tempts the eye to wander from one part to another, observing the continuities and discontinuities while being immersed in the polyphony of sounds and images, lingering on one shot while others fall out of sight. In a more conventional set-up of installation art, the audience is invited to perambulate freely among several screens, and the attention becomes more naturally divided by the spatial arrangement. Here, however, there is an immobile spectator sitting in front of a cinematic projection of images and experiencing a continuous, overwhelming flux between seeing and not seeing. At the same time, the masked frames also reignite the tension between two traditional modes of picturing the world, i.e., between opening up an Albertian window and offering the aesthetic pleasure of scanning surfaces, forms, and textures contained within the image. According to Svetlana Alpers, “fragmentariness; arbitrary frames” (Alpers 1983, p. 43) are characteristics of what she considers “the descriptive mode” (Alpers 1983, p. 43) in painting and inherent to photography. Instead of a window “to which we bring our eyes”, or the invitation to look at things, in this mode we have “the picture taking the place of the eye” and an invitation to behold “‘the look’ of things” (Alpers 1983, p. 45). Accordingly, elevated by the inner frames, it is the sheer, fleeting cinematic “look” of the world that is brought into spotlight once more, in which “the smallest of gestures becomes playful. The detail delivers the grace” (Dean 2018b, p. 166). Each inner frame veers towards the “untamed”, radical openness of meanings of a photo, resisting cinema’s tendency to domesticate “the essential wildness of photography” (Campany 2007, p. 13). Dean explicitly acknowledges these issues in a dialogue in the film about the theme of blindness and seeing corresponding to “photography and cinema: photography in relation to painting, and cinema in relation to narrative”.38

The film can be seen as a self-reflexive journey through the arts and even an allegorical synthesis of Tacita Dean’s intermediality discussed here.39 Antigone, the child of an incestuous relationship in the Greek tragedy, becomes a symbol of another “incestuous” relationship, i.e., of a unique hybridity between two related but still very different ways of creating moving images (one connected to seeing the world in a constructed, comprehensive cinematic vision and the other to abandoning visual control in favour of photography’s own power to capture reflections of the tangible world). Despite its severed roots in the abandoned project of a fiction film, Antigone, as a piece of installation art with its stretched-out format and gorgeous vistas, inherits cinema’s grandeur of an awe-inspiring picture show designed for a dark hall with spectators’ eyes glued to the screen, yet it is also “genetically” defined by the intimate darkroom craftsmanship of a private and small-scale celluloid filmmaking and by its fractured, photographic aesthetic, relying on the volatility and blindness involved in photochemical processes. In this way, Antigone as a cinematic spectacle is not showing us pictures but merely revealing the transience of images appearing and disappearing within the frames, implying ultimately the precariousness and instability of the human eye facing the eternal mutability and incomprehensible immensity of the natural (and cultural) world. In the original story, Antigone is the one who leads the sightless Oedipus into the play’s mythical hinterland. Here, despite being chosen for the title of the film, she is not materialised as a character, but her enigmatic name might as well refer to all the affective intensities that connect various realms of images (both still and moving), forms of imagination (sensory, pictorial, literary, etc.), perceptions of the world (physical, emotional, conceptual), and lead us across the liminal landscapes of Dean’s intermedial art.

Finally, to conclude our journey proposed by the 2018 exhibitions through Tacita Dean’s prolific art practice straddling the visual arts, filmmaking, and curatorial work, I would like to emphasise the extraordinary capacity of her work to direct our attention towards a close-up view of the affective-performative aspects of intermediality. For in Dean’s approach, intermediality emerges not as a mere combination of elements from different arts but as a versatile artistic strategy for re-sensitization that enables the viewer to rediscover the sensorial richness and affective qualities of an artistic medium by approaching one art from the point of view of another. Paradoxically, this re-sensitization relies not on the sharpening of the eye or the expansion of vision, but on a concrete and metaphorical expansion of sense-enhancing and performative blindness, suggesting we do not need to see more, but—like Coleridge’s blind poet—we need to engage all our senses, turning blindness into “all eye”, to “feel” the images by registering the fine oscillations, transitions, and superimpositions between the arts (e.g., between photography, film, painting, and poetry). Through an emphasis on ephemerality, sensuous impressions of medium ambivalences, blind chance in the “look of” the world revealed through the analogue photographic image, as well as through her preference for unique, site-specific dispositifs involving delicate technical apparatus,40 she advocates for an aesthetic sensitivity that embraces the wondrous affordances as well as the extreme fragility of her mediums, defying through her innovative, deeply personalised, affective relationship with these “old” mediums the era of digital reproducibility and automated digital creativity. Furthermore, her strategy entails a mutual revitalization of words and images, of painting, photography, analogue film, and the cross-media phenomenon of the “cinematic” which repeatedly pits immediate sensations of “molecular” becoming of one medium folding into the other against intellectual associations, universal frameworks of the arts, genre, and narrative in a manner that dwells insistently on what Henri Bergson saw as “the affective states” between images and ideas, on the “impenetrable mystery” of “the passage from affection to representation” (Bergson [1896] 1991, p. 61).

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization in Romania, CNCS–UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P4-PCE-2021-1297, within PNCDI III.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See a detailed description of such theoretical avenues unfolding from Jean-François Lyotard’s notion of the figural, along with a rethinking of intermediality following Raymond Bellour’s, Alain Badiou’s, Jacques Rancière’s, Giorgio Agamben’s and Lúcia Nagib’s ideas on dispositifs, passages between the arts, mediums and reality, in Pethő (2020). |

| 2 | See Brian Massumi’s thoughts on the “autonomy” of affects: “They are autonomous not through closure but through a singular openness. As unbounded ‘regions’ in an equally unbounded affective field, they arc in contact with the whole universe of affective potential” (Massumi 1995, p. 105). |

| 3 | This is Steven Shaviro’s (2016) summary: “If emotions are personal experiences, then affects are the forces (perhaps the flows of energy) that precede, produce, and inform such experiences. Affect is pre-personal and pre-subjective; it is social, or even ontological, before it is strictly individual. Affect isn’t what I feel, so much as it is what forces me to feel”. |

| 4 | See, for example, the pictures published in the catalogue of the exhibition, L.A. Exhuberance, at Gemini G.E.L. in 2016, online: https://issuu.com/geminiatjoniweyl/docs/tacita_dean_-_la_exuberance?fr=sMGY5NjQyOTI0ODU (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 5 | Tacita Dean’s palm touching the canvas, lightly smoothing and brushing the surface are the very first images that introduce the documentary made for BBC One in 2008, Imagine: Tacita Dean: Looking to See, and later on such images are repeated whenever we see her working in her studio. The film is available online here: https://vimeo.com/281953375 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 6 | Tacita Dean (2021) declared with some pathos in an interview: “The problem with film is that it’s still considered a technology. […] It is aggressively labelled as obsolete and old fashioned because technologies go out of date. […] But for me it’s a medium, not a technology. And if you call it a medium then you put it on a completely different trajectory”. |

| 7 | The writings and interviews in which Dean discusses her works in a highly articulate way and with the sensitivity of a poet, not only “function as important textual supplements”, as Erika Balsom has observed (Balsom 2013, p. 69), but they have become (like the theatrical “asides” that Dean often mentions) integral parts of the multimedia experience of her art. In this respect, despite Dean’s preference for analogue mediums in her practice as well as in the representation of her art (e.g., offset prints of frames from her films, artist’s albums with photo reproductions and texts), her digital presence on the internet is also noteworthy. |

| 8 | See a summary of the series here: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/dean-the-roaring-forties-seven-boards-in-seven-days-t07613 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 9 | See pictures of the series here: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/dean-the-russian-ending-75361 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 10 | See a description of the picture, Ship of Death (2001) from this series, owned by Tate Modern, in which cinematic references are mixed with allusions to Greek mythology: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/dean-ship-of-death-p20246 (accessed on 2 March 2023). The text also draws attention to the fact that Dean’s interest in cinematic storytelling and the film industry is also manifest in other works, like her installation (exhibited at the Tate), Foley Artist (1996) about the creation of acoustic effects in cinema, or her film, Uncles (2004), which presented Tacita Dean’s family connections to two early filmmaking pioneers, the founding figures of Ealing Studios, Basil Dean and Michael Balcon, through the recollections of her two uncles. |

| 11 | For a more comprehensive analysis of inscriptions in Tacita Dean’s blackboard drawings and photogravures, including the narrative that could be untangled from the words appearing in Blind Pan (2004) see Newman (2013). |

| 12 | The title of the drawing refers to the Montafon valley in Austria, where supposedly an avalanche buried more than 300 people in 1689. When a priest went to the site to pray for the victims, another avalanche buried him too, only to be rescued by a subsequent avalanche, which unburied him. The picture was also exhibited together with two similar monumental drawings, Sunset (2015) and When First I Raised the Tempest (2016), in the manner of a panorama display at the Glenstone Foundation in Potomac, Maryland, USA, between November 2020 and October 2022 (see: https://www.glenstone.org/art/exhibition/tacita-dean/ (accessed on 2 March 2023). This drawing may be seen therefore as representative of an entire subgenre created in Dean’s oeuvre (including further works like: Chalk Fall, 2018; The Wreck of Hope, 2022). |

| 13 | See: https://archive.artic.edu/stieglitz/equivalents/ (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 14 | The line used for the title is from Shakespeare’s Richard II. See images from this exhibition here: https://www.mariangoodman.com/exhibitions/66-tacita-dean-my-english-breath-in-foreign-clouds/ (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 15 | James Benning’s Ten Skies (2004) is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dnBGr6VsDVU (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 16 | These immersive pictures incited the viewer to perform a similar action as Tacita Dean’s camera did in her film, Buon Fresco (2014), in which she filmed extreme close-ups of the details in Giotto’s fresco covering the walls of at the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, in this way—to quote the poetic words of Evgenia Citkowitz (2021, p. 2)—“connecting the viewer to that revelatory moment of the artist’s imprint and the intimacy of seeing pigment breathing through pores in plaster”. |

| 17 | This was not the first curatorial project that Tacita Dean had embarked on. In 2005, for example, she created a selection for an exhibition at the Camden Art Centre in London, with the title, An Aside, which experimented with surreal juxtapositions and the idea of “objective chance,” something that she felt had close affinity with her own art practice. https://camdenartcentre.org/file-notes/file-note-01-tacita-dean (accessed on 2 March 2023). The Landscape exhibition at the Royal Academy in 2018 also presented mixed media works, found photographs and even her own collection of stones and pressed multiple leaf clovers, selected by Dean to add personal, tangible, cultural and even political associations to the idea of landscape. |

| 18 | Still Life was also the title chosen for Tacita Dean’s first major exhibition in Italy at the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, Milan, 12 May–21 June 2009. See: https://www.fondazionenicolatrussardi.com/en/mostre/still_life/ (accessed on 2 March 2023). According to the official site, that show was a “a celebration of slowness and memory,” and included some of the films that could be later seen in the Portrait exhibition in 2018, which only proves the interlacing of conceptual threads that can be unravelled from her oeuvre. |

| 19 | https://artscouncilcollection.org.uk/artwork/beerenstilleben (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 20 | https://matthewmarks.com/exhibitions/thomas-demand-dailies-11-2013/lightbox/works/daily-13-2011-35893 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 21 | https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/guston-hat-t07132 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 22 | For an in-depth analysis of Tacita Dean’s engagement with the genre of still life in painting, based on her works featuring in her 2009 exhibition in Milan, and especially on her films, Still Life (2009) and Day for Night (2009) using footage shot in the preserved studio of the still life painter Giorgio Morandi (1890–1964), see Krčma (2014). |

| 23 | https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/5242 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 24 | David Campany wrote in his preface to the collection of essays on The Cinematic: “Moving images transformed the nature of the photographic image, turning its stillness into arrestedness” (Campany 2007, p. 12, emphasis in the original). |

| 25 | Tacita Dean: Prisoner Pair (2008), https://www.mariangoodman.com/artists/39-tacita-dean/works/38104/ (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 26 | William Henry Hunt (1790–1864): Apples; https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hunt-apples-n01974 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 27 | Paul Nash (1889–1946): Event on the Downs (1934); https://artcollection.culture.gov.uk/artwork/8536/ (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 28 | See, for example, the description of the way such prints are prtangioduced in the catalogue of the exhibition, L.A. Exhuberance, at Gemini G.E.L. in 2016, online: https://issuu.com/geminiatjoniweyl/docs/tacita_dean_-_la_exuberance?fr=sMGY5NjQyOTI0ODU (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 29 | “Passages” was also the keyword of the groundbreaking exhibition, Passages de l’image (at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, in 1990) that Raymond Bellour co-curated and which was devoted to the idea of the intermediality of contemporary images of photography, film and video. |

| 30 | The dispositif remains a much debated term in social sciences and philosophy. In film studies, in the widest sense, theorists have defined it to include the so-called “basic apparatus” comprising the material components, a particular set of technologies for production and projection, as well as their concrete, architectonical structure, and the phenomenological, psychological, and ideological aspects of viewership. See a comprehensive overview of the theories regarding the notion in Parente and de Carvalho (2008) and in Elsaesser (2016), who argues, from a media archaeological point of view, against looking only at the specificities in the historical divergence of the cinematic dispositifs, and for “grasping their mutually interacting dynamics” (2016, p. 111). |

| 31 | In Mondloch’s words: “the interface ‘matters’ for media installation art. It matters in the sense that it constitutes an essential component of the artwork (the various dealings between spectators and the screen are structural to the work), but also because the body—screen interface is a phenomenal form in itself as well as a constitutive part of an embodied visual field” (Mondloch 2010, p. 4). |

| 32 | https://www.npg.org.uk/whatson/display/2018/his-picture-in-little-shakespeare-hamlet-and-tacita-dean (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 33 | https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/dean-film-t14273 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 34 | https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/tacita-dean-landscape (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

| 35 | We hear the question in Dean’s voice in the film, “Outside narrative?” For these (and further) quotations from the dialogues in the film, see the transcript published in Friedli et al. (2022). |

| 36 | Quotation from the film. |

| 37 | I would like to thank Moet Wyborn from the Frith Street Gallery in London for her kind assistance in providing me the pictures of Tacita Dean’s works that I could use in this article. |

| 38 | Quotation from Tacita Dean’s lines in the film. |

| 39 | Its status as a synthesis work is confirmed by the fact that it has also been shown alongside a different selection of works for the exhibitions organized at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen in 2019 and at the Kunstmuseum Basel in 2021. |

| 40 | Tacita Dean’s 2023 film installation, Geography Biography, exhibited in a circular space at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris (between 24 May and 18 September 2023), is perhaps technically her most complex and unique installation work to date. It consists of two synthesized 35mm projectors mounted on a spinning platform projecting images taken from her previous films superimposed over magnified, portrait oriented found postcards. |

References

- Adams, Tim. 2018. Tacita Dean: The Acclaimed British Artist Poised to Make History. Interview. The Guardia. March 11. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/mar/11/tacita-dean-interview-celluloid-heroine-london-exhibitions-film (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Alpers, Svetlana. 1983. The Art of Describing. Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, Gaston. 1964. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press. First published 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Balsom, Erica. 2013. Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Baumbach, Nico. 2009. Nature Caught in the Act: On the Transformation of an Idea of Art in Early Cinema. Comparative Critical Studies 6: 373–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazin, André. 1967. The Ontology of the Photographic Image. In What Is Cinema? Edited by Hugh Gray. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, vol. I, pp. 9–16. First published 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Bellour, Raymond. 2008. Of Another Cinema. In Art and the Moving Image: A Critical Reader. Edited by Tanya Leighton. London: Tate Publishing, pp. 406–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bellour, Raymond. 2012. Between-the-Images. Zürich: JRP/Ringier. Dijon: Les Presses du Réel. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bellour, Raymond. 2012. La Querelle des Dispositifs: Cinéma—Installations, Expositions. Paris: P.O.L. [Google Scholar]

- Bellour, Raymond. 2013. “Cinema, Alone”/Multiple “Cinemas”. Alphaville. 5 (Summer). Available online: https://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue5/PDFs/ArticleBellour.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Bergson, Henri. 1991. Matter and Memory. New York: Zone Books. First published 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Beugnet, Martine. 2013. Miniature Pleasures: On Watching Films on an iPhone. In Cinematicity in Media History. Edited by Jeffrey Geiger and Karin Littau. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, Giuliana. 2022. Atmospheres of Projection. Environmentality in Art and Screen Media. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campany, David, ed. 2007. The Cinematic. London: Whitechapel. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal, Rina. 2007. Film is a Medium of Time: A Conversation with Tacita Dean. In Tacita Dean. Film Works. Edited by Rina Carvajal. Milan: Edizioni Charta, Miami: Miami Art Central, pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Citkowitz, Evgenia. 2021. The Clouds Look Very Different Today. In Tacita Dean at Gemini G.E.L. LA Magic Hour (Exhibition Catalogue). Los Angeles: Gemini G.E.L. LLC. Available online: https://issuu.com/geminigel/docs/tacita_dean_la_magic_hour?fr=sMGRjNDQzMDM4NDU (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Conley, Tom. 2010. Molecular. In The Deleuze Dictionary. Revised Edition. Edited by Adrian Parr. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 177–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cuno, James, and Tacita Dean. 2019. J. Paul Getty Trust Art & Ideas Podcast: Artist Tacita Dean and Her Many Mediums. Available online: https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/podcast-tacita-dean/ (accessed on 2 March 2023).