Three of the seven emirates host an art scene that is at the same time unique from the others, and yet also benefits from the differences that the neighboring states provide and, to some extent, mimic them. Depending on what we choose to elect as the most imperative factor in defining an art scene will determine how to present and classify the three different art scenes.

Today, Abu Dhabi, the federation’s wealthy capital, is most known for its “starchitect” designed institutions, often conceived as a local branch of a long-existing foreign establishment. Not surprisingly, being a commercial hub, Dubai is reputed for its annual art fair, Art Dubai—the largest in the region—in addition to locally based grassroots commercial galleries. As for Sharjah, its biennial has long attracted art lovers, and it is also the core from which the Sharjah Art Foundation (and all its derivatives) have sprung. Nearly all art initiatives come from either the current ruler, Sheikh Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi, or his daughter, Sheikha Hoor Al-Qasimi.

4.1. Abu Dhabi

In terms of its art scene, Abu Dhabi today is known perhaps most famously for the Louvre Abu Dhabi, on Saadiyat Island (see

Figure 2), announced in 2007 but only completed in 2017. Theoretically, the local branch of the most visited museum in the world (

Da Silva 2022) is not unique to this 27 km

2 island; there are also plans to host a local Guggenheim, among other museums.

In March 2007, an agreement was signed between Agence France-Muséums (or AFM) and Abu Dhabi Tourism Authority (or ADTA), announcing the creation of the Louvre Abu Dhabi. The group revealed that Jean Nouvel would design this new museum, and among its neighbors was to be the next iteration of the Guggenheim network, designed by another starchitect: Franck Gehry.

While the Louvre opened after several delays in 2017, local economic woes in addition to continued protests of the emirate’s human rights practices delayed the groundbreaking of Gehry’s next Guggenheim. In 2021, the Guggenheim brand revealed that construction should soon begin and that the opening would take place in 2026 (

Hilburg 2021).

Even though the newest Guggenheim iteration is not yet open, and Louvre did not do so until 2017, both museums have long had a presence in the local and international art community as if they have always been open. Since 2010, these institutions have appeared in local art guides (for example in

Art Map (

2010), starting in issue 11), and soon after each began hosting events in off-site locations such as their Talking Art Series. Beyond the art scene, but significant to note in a discussion on Abu Dhabi’s architecture and society, several other museums fall into this trend of illustrious institutions designed by world-class architects.

Whereas they have little in common in terms of their internal contents or mission, these museums share geographic proximity in that they were all designed for Saadiyat Island. The ADTA bought this natural island located slightly northeast of Abu Dhabi in 2004 to develop it into a “signature destination with environmentally sensitive philosophies” (

TDIC n.d.). The Abu Dhabi government created the ADTA for that specific purpose and later changed its name to the Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority (or the ADTCA) (

Kazerouni 2017). In 2012, the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture & Tourism launched, joining the Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage, Abu Dhabi Tourism Authority, and the Tourism Development & Investment Company (abbreviated as the TDIC), a private development company. Regardless of the multiple name changes, the overall purpose has always been to promote culture and tourism in Abu Dhabi, and they have always been largely government entities or private ones created with those specific missions in mind.

Among the original structures destined for “the Island of Happiness”, in addition to the Louvre and the Guggenheim, is the Sheikh Zayed National Museum, a performing arts center, and a Maritime Museum—alluding to the country’s past in pearling and fishing, were planned (see

Figure 3). It is noteworthy, yet no wonder, that the architects for these three structures were all Pritzker-prize winning: Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid, and Tadao Ando, respectively. To this day, the only one planned to open is the Norman Foster’s Zayed National Museum. Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism website refers to neither Hadid’s “Fruits on the Vine” performing arts center nor Tadao Ando’s dhow (a traditional local boat) shaped maritime museum. The website still discusses the Zayed National Museum in the future tense but gives no opening date. The British Museum, originally a partner of the Zayed National Museum, renounced its collaboration in 2017, but currently, the structure still seems to be planned for construction later.

Art and culture in Abu Dhabi are not limited to these, longtime mostly theoretical, museums, but they are perhaps most emblematic of the emirate’s “flavor” of art and architecture. They are also reflective of the country’s perpetual future thinking. While less well known internationally, the Cultural Foundation, which opened on Sheikh Zayed’s initiative in 1981, can be seen as the precursor to the Abu Dhabi versions of the Louvre, the Guggenheim, and the other starchitect-designed museums. The Abu Dhabi government launched the competition for the Cultural Foundation in the 1970s, nearly a decade before its opening.

Founded by the world-famous Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius, the Architects’ Collective’s (or TAC) proposal won the competition and finalized their plans by 1975. From its inception, Abu Dhabi thus has had a tradition of conceiving large-scale institutions designed by world-renowned foreign architects.

If the Cultural Foundation is home to the first national library, performance hall, and cultural center—and illustrative of the emirate’s and country’s onward perspective to the future—there are also traditional structures that were “sanctified” even before this one, historical structures that look onto the past. For example, the government inaugurated the Al Ain Palace Museum (Abu Dhabi’s smaller city and Sheikh Zayed’s birthplace) in 1971. While the Qasr Al Hosn Museum only opened in 2018, this historical fortress tower is considered one of the most important architectural monuments of the Emirate. It is noteworthy that the government chose to build the Cultural Foundation just across from it to bring the future and the past together in the new country. This juxtaposition also brings together examples of both academic and vernacular architecture.

One can observe this contrast—academic vs. vernacular—elsewhere in Abu Dhabi as well as in the two other emirates; however, the juxtaposition is not so striking in the other cases. Beyond that, this contrast is present in many levels of Emirati society, not as a visual distinction, but rather as a nearly omnipresent contradiction between a nostalgia for a quickly fleeting past and a coveted yet overwhelming onset of the future. We shall explore different examples in the other emirates before comparing the three together.

4.2. Dubai

If Abu Dhabi’s artistic presence is mostly defined by large institutions that are the products of international agreements—suitable for a capital city and the wealthiest emirate—it is no surprise that the artistic landscape of the more commercial Dubai has been composed more historically with more commercial structures. In Dubai’s case, the presence of galleries makes up the local art scene. Individually smaller and less well known than the larger institutions in Abu Dhabi—and later Sharjah—together, these grassroots structures characterize the art scene in Dubai. The first gallery was opened by British ex-pat Allison Collins in 1979—in her home in the Bastakia/Al Fahidi district, i.e., the “Old Dubai” district that covers approximately 0.06 km

2 of the now sprawling city (see

Figure 4). It was only in the 1990s when other galleries began to spring up with five galleries opening between 1995 and 1998; at this time, Abu Dhabi only had one, and Sharjah had none. Twenty-one more galleries launched between 2003 and 2009, and forty-nine between 2010 and 2020.

Dubai’s first galleries opened either in the owner’s home or, slightly later, in warehouses in the larger and more industrial district Al Quoz—about the same size as Saadiyat island. These structures reflect both the city’s more distant (merchant houses in Old Dubai) and more recent (warehouses to serve the ports of Sheikh Saeed and Jebel Ali) past. For the former, Allison Collins opened the Majlis Gallery in her home in Old Dubai for the simplicity of doing so nearby. This area is now referred to as the Al Fahidi historical district and hosts many examples of houses owned by pearl merchants or other wealthy traders whose business was in proximity to the Khor Dubai (Dubai Creek). Today, it is in the literal and figurative shadows of buildings in Downtown Dubai (Dubai Mall, Burj Khalifa, Dubai International Financial Centre, and more recently, the Museum of the Future, and the Dubai Frame), the Palm, Dubai Marina, and other developments. At the time of Collins’ arrival in Dubai, many of these areas did not yet exist, and she found the ancient quality of these crumbling buildings charming. Several years later, in 2003, Mona Hauser also opened a gallery and hotel in this area: the XVA Gallery.

While she did not live there, she describes appreciating a similar charm to these buildings, especially in contrast with all the new construction. More importantly, that she also chose to recycle an existing structure built for a specific purpose other than being an art gallery is remarkable. In 1995, the Green Art Gallery, started by the Atassi sisters as the Ornina Gallery in Homs, Syria, opened in another residence in Dubai: a villa in the beachfront neighborhood of Jumeriah. Again, the main reason to open chez soi was out of simplicity to not have to rent a new location.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, warehouses, mostly in the Al Quoz industrial district, became the next kind of structure used to house galleries. The first example of this is the Courtyard/Total Arts Gallery. Today, many of the most famous galleries in Dubai are in this area. Like other examples of transforming former industrial space into exhibition locations, the lower cost of rent in these less-desirable locales motivated gallerists to slowly move there as rents in other parts of the city kept creeping up. Reflective of trends elsewhere in the art world of artists recycling factories, hangars, and other manufacturing edifices, the use of these structures also reflects trends in Dubai’s history.

Later, as the art scene grew, galleries began to rent spaces in more modern structures—not residences or warehouses as we have seen in the past, but constructions catering to, and demonstrative of, a growing transient population such as hotels, malls, and retail floors of the city’s numerous skyscrapers. Well-reputed galleries such as Tabari Artspace, 1x1 Gallery, Andakulova Gallery, East Wing (now closed), Opera Gallery, and Lumas, although in different locations today, are some examples. Other less well-known examples include Gallery One, Legacy Art, Sovereign Gallery, Monde Art, Profile Gallery, DUCTAC (nonprofit), and the Vindemia Gallery. This trend is reflective of the fact that there was indeed a growing art scene, but not specific neighborhoods associated with the arts, explaining why, in the early days, galleries existed throughout the city in structures that seem like a curious choice for an art gallery.

The use of malls or hotels as a host for galleries is unusual in the West; however, it should rather be thought of as a gallery in a souk or bazaar. Such markets have a long tradition in the Middle East for being hubs of commercial activity. In the UAE, and Dubai especially, malls continue this tradition, and the fact that they are air-conditioned also helps to attract an audience and foot traffic not found elsewhere. As for hotels, these constructions often lend themselves as temporary hosts of conventions or other meetings. With this purpose in mind, some of the original gallery owners rented space in hotels, knowing that an international audience would see their exhibited artwork. Finally, when navigating Dubai, one rarely refers to streets when giving directions, save for large thoroughfares such as Sheikh Zayed Road, Al Wasl Road, Al Manara Street, etc., but rather by tower, hotel, or mall names. With the rapid rate of construction in this city, roads can quickly appear or disappear as urbanization continues; it makes more sense to navigate using structures that people can see and that are known.

Until 2007–2008, galleries existed in locations built for other purposes: residential (old or new), recycled industrial warehouses, and non-specific retail space. This year is a crucial moment for the art scene in Dubai (as well as elsewhere in the UAE) as it marks the start of a new era with the officialization of Alserkal Avenue, the DIFC Gulf Art Fair (later branded as Art Dubai—today the region’s biggest art fair), and the first local sale from Christie’s auction house. In 2008, the DIFC’s (Dubai International Financial Centre) Gate Village opened as a commercial and retail hub to service this increasingly important business free zone. While the Gate Village is only 0.02 km2, the entire DIFC spreads over 0.56 km2. Conceived to host luxury shops and lavish restaurants, several previously established galleries moved there, while other new galleries opened.

Among the former, these include the Tabari Art Space (moving from the Fairmont Hotel Downtown), and the XVA Gallery, which opened a second location there for a few years, while new galleries such as Cuadro, Art Sawa, Opera Gallery, and the Empty Quarter all started there around this time. Christie’s also had their offices there, while the first version of Art Dubai took place in the DIFC before moving to Madinat Jumeirah, though its offices remained there until moving to Dubai Design District years later. In this case, we are getting closer to purpose-built architecture for art exhibitions, whereas in the past, gallerists would reappropriate vernacular architecture previously built for an entirely different use. The DIFC Gate Village was conceived with a more specific purpose than retail space in malls, hotels, and skyscrapers, but was, nonetheless, not designed for art exhibitions.

In 2013, Dubai Design District (abbreviated as d3) was announced as a 0.08 km2 planned community to host businesses and organizations whose work revolves around design, art, fashion, etc. In the larger scope of Dubai’s urbanization, it is not unlike other real estate developments in Dubai: owned and constructed by TECOM investments. This group is a branch of Dubai Holding; Dubai’s ruler, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum owns most shares of this company. D3 is not the first kind of development for this group that designates a discipline or subject to a new part of the city; these include Dubai Internet City, Dubai Outsource City, Dubai Media City, Dubai Studio City, Dubai Production City, Dubai Knowledge Park, Dubai International Academic City, Dubai Science Park, and Dubai Industrial City. Concerning just the arts, however, this is the only example where the local government created buildings, let alone an entire neighborhood, for the arts. The artistic specification is noteworthy because, unlike Abu Dhabi and Sharjah, early milestones in the Dubai art scene were made by civilians and not by government entities or members of the royal family.

Indeed, the cluster of galleries that became more officially known as “Alserkal Avenue” (see

Figure 5) in 2008 started out as just that: a few rows—or avenues—of warehouses that previously only had industrial purposes—some are still there to this day. Adjacent to these structures stood a marble factory that the Alserkal Avenue group tore down in 2012 to make way for a mirroring expansion that would open in early 2015. In this case, Alserkal Avenue belongs to the wealthy Al Serkal Family.

This family, whose “Alserkal Group” was established in 1947, well before the federalization of the country, owns, or are the local shareholders of, such corporations as Bridgestone tires (since 1948), Pepsi (since 1962), the Commercial Bank of Dubai (since 1969), Beit Al Khair society (a philanthropic society since 1970), Etisalat (one of the country’s two largest telecommunications company, since 1976), Dubai Insurance (since 1989), Dubai Electric and Water Authority (since 1992), Dubai Autism Center (since 2001), Al Mal Capital (since 2005), and Emirates NBD bank (previously the National Bank of Dubai, since 2007). Local but not royal, the Al Serkal family is nonetheless a key player in Dubai’s overall development, including its art scene. While the whole family is involved, Abdelmonem Bin Eisa Alserkal, the grandson of the family’s founder (Nasser bin Abdullatif Alserkal), is the family member most involved with this endeavor, along with his long-time collaborator, Lithuanian-born Vilma Jurkute.

The expansion doubled the size of the “Avenue”, to about 0.05 km2, and the new construction mirrored the original ones. The architects conceived the new buildings to resemble the original warehouses but with the idea to host new art spaces, among other purposes. Unlike Abu Dhabi, which always had a long history of employing internationally renowned architects, Alserkal Avenue opted for a local option: QHC Architects (based in Sharjah) and EDMAC Consulting (based in Dubai and Fujairah).

For the most part, the architecture that hosts Dubai’s art scene are structures previously not used to display art but reappropriated to do so: residential villas, hotels, malls, towers, and warehouses. Districts such as DIFC and d3 perpetuated and specified the use of hotels, malls, and towers. The new warehouses at Alserkal Avenue copied the aesthetic of its original warehouses (not built for art) for a more bespoke arts purpose. In Dubai, being that the early examples of the art scene came from individuals and not government initiatives, it makes sense that the original structures to house the art scene were simple, vernacular examples of places that anyone could access i.e., not large new buildings as we have seen in Abu Dhabi (or later in Dubai with parts of the DIFC and d3) or reusing significant historical structures that are government owned. The latter method, we observe in Sharjah.

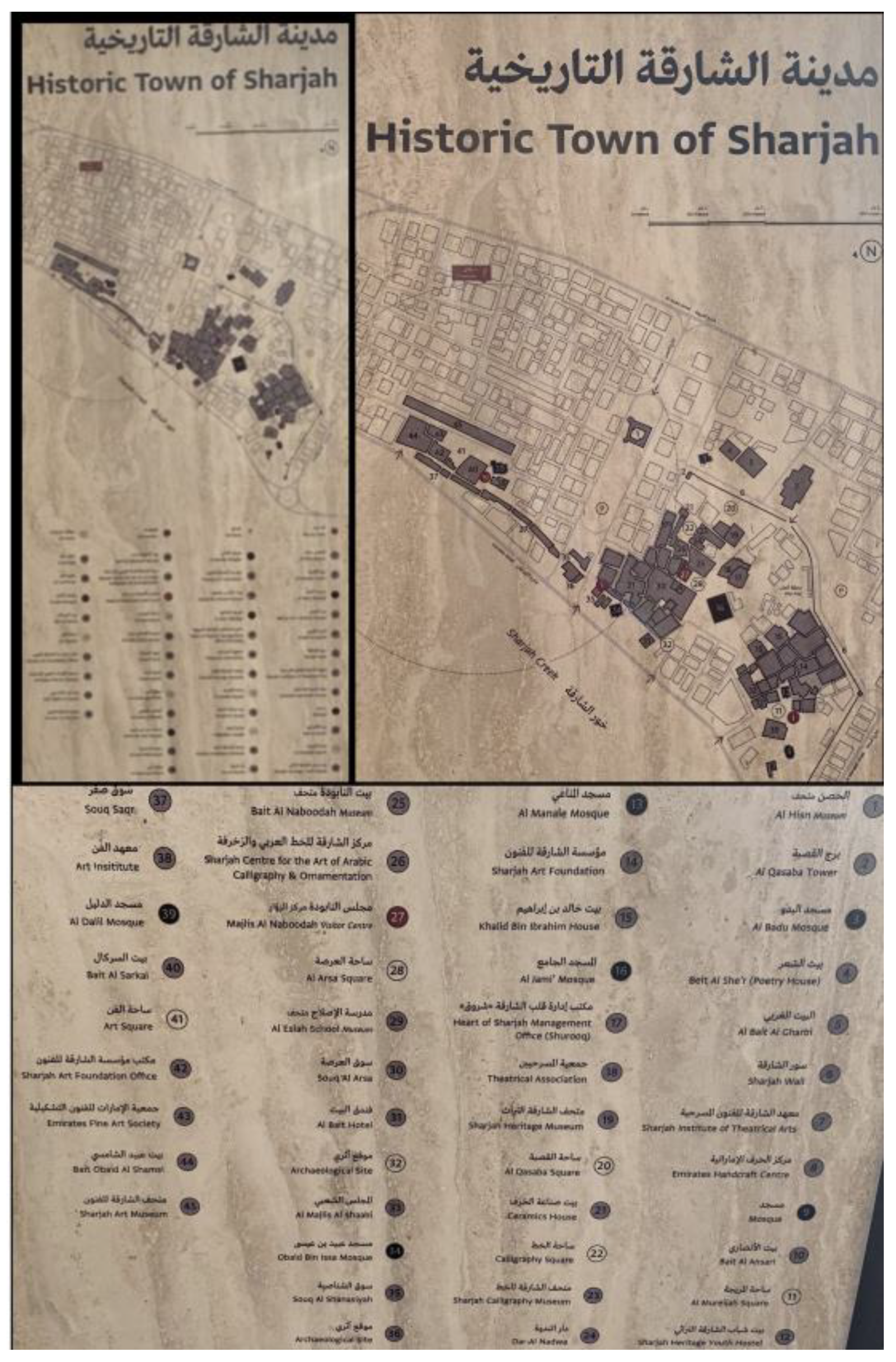

4.3. Sharjah

In the case of Sharjah, many of the buildings that house the art scene are historical—while such examples exist in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, that is the exception in those emirates. Select members of Sharjah’s ruling family (the Al-Qasimis) run the local art scene, which is mostly located in the center of the old town (approximately 0.035 km

2 also referred to as the “Heart of Sharjah” or the “Arts District, see

Figure 6); the use of historical buildings is, thus, not surprising.

While in Abu Dhabi the first example of architecture to display art and culture (the Cultural Foundation) is indeed in the historical center of the city, today it has shifted to Saadiyat Island, specifically designed by the government to host strongholds of culture. In Dubai, similarly, the first example of a gallery was along the Creek in the older part of the city, but the art scene has also migrated to newer neighborhoods, emblematic of its future: the industrial Al Quoz, the Dubai International Financial Centre, and in later years, Dubai Marina.

Today’s art scene revolves around the Sharjah Art Foundation, presided by Sheikha Hoor Al-Qasimi, the current ruler’s daughter. She established the SAF in 2009 as the permanent iteration of the Sharjah Biennale, founded in 1993 by her father Dr. Sheikh Sultan Al-Qasimi. He is solely responsible for creating the institutions in Sharjah that celebrate its culture (Sharjah Archaeology Museum, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah Calligraphy Museum, Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilization, etc.), all under the auspices of the Sharjah Museums Authority. Sheikh Sultan has been promoting traditional culture and art in the larger sense of the term (theater, literature, calligraphy, etc.) since the 1980s. He was also the first leader to do so specifically for contemporary art: he launched the not-for-profit (a rare status at the time in the newly founded country) Emirates Fine Arts Society (or EFAS) in 1980 through the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. The group’s original building, a former merchant residence in what has become “Arts Square”, still houses it today. In addition, the Sharjah Art Museum opened in 1997, again a project of the Sheikh, in a new building, but in the historical part of town, and designed with a traditional style (see

Figure 7).

That same year, the Sharjah Art Institute—dedicated to teaching—was established in the former Al Serkal House.

1 The Maraya Art Center—not linked directly to a specific royal family member but rather a project of the Qasba, a neighborhood and business center founded by the Sharjah Investment and Development Authority (or Shurooq)—was founded in 2006. It is a modern construction, but in the Mudejar style. The Sharjah Art Foundation opened its doors in 2009 in various buildings around Arts Square and Calligraphy Square. Originally, all these structures were in traditional edifices, but, in 2013, new construction was also completed in Al Mureijah Square to modernize these spaces all while keeping the historical aesthetic.

Since then, both the SAF and the Maraya Art Center, though in a lesser way, have expanded and added buildings to their rosters. Unlike Dubai and Abu Dhabi, where both have witnessed adding new, independent structures, or additional branches of foreign entities, Sharjah’s art scene is exclusively homegrown and dominated by two institutions: SAF and Maraya. In 2015, the Maraya Art Center opened the architecture and design-specific 1971 Design Space at a second location (Flag Island). Like the first Maraya building, 1791 Design Space is modern; a well-known architect does not seem to have conceived it, or at least that information is not promoted, unlike the other local institutions. Before enumerating, in detail, the various venues and styles of the SAF, Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, also a member of the royal family, created the Barjeel Art Foundation in 2010. This collection does not have a permanent physical space—a characteristic we observe more in Dubai (such as with the Atassi Foundation or the Dubai Collection) than in Sharjah—but is nearly always on view either at the Maraya Art Center, elsewhere in Al Qasba (the shopping district hosting the Maraya art center) or, since 2018, at the Sharjah Art Museum.

As for the Sharjah Art Foundation, one name means dozens of locations. At the time of writing, the SAF website breaks down its various buildings into two main categories: Adaptive Reuse and Constructed by SAF.

Table 2 illustrates this information. Unlike Abu Dhabi and Dubai, most buildings employed by the Sharjah Art Foundation, which is arguably the largest art institution in the emirate, are historical—whether they be ancient fortresses, 19th-century merchant houses, or 20th-century industrial buildings (for example, the Kalba Factory, Dibba Al Hisn Ice Factory, etc.). There is a strong emphasis on celebrating Sharjah’s past from various points in its history. The “adaptive reuse” of historical residences (any building on the list that begins with “bait”, meaning “house of” or “home”) is a demonstration of this tendency. The way in which the SAF has reused or rebuilt other locations also manifests this trend.

One of the most noteworthy examples of recycled buildings for the purposes of showcasing art is the “Flying Saucer.” Dating from the 1970s, this unusual construction has hosted a variety of businesses such as a French-style

pâtisserie, restaurant, gift boutique, news kiosk, and tobacco vendor—all in one, then as the Al Maya Lal’s supermarket and Life Pharmacy, next as the home to the Sharjah co-operative society, and, lastly, as the Taza Chicken fast food restaurant (

Sharjah Art Foundation n.d.). The SAF acquired the building in 2012, and since 2015 has used it as an off-site venue. A renovation project began in 2018, led by Mona El Mousfy of the locally based SpaceContinuum (

sic) Design Studio (

Yerebakan 2020). This firm renovated historical buildings in various galleries of the SAF around Arts Square, in addition to the modern building that houses the Rain Room (

Middle East Architect 2018).

For the latter, the SAF has featured this immersive installation by Random International since 2018, but such institutions as the Barbican, London (2012); MoMA, New York (2013); Yuz Museum, Shanghai (2015) and LACMA, Los Angeles (2015–2017) (

Selvin 2018) have also exhibited it. Indeed, Sharjah’s art scene is host to a very local set of institutions, but its understated partnerships spread nearly as far and wide as those of Abu Dhabi. Among them are the Australia Council for the Arts, British Council, Danish Agency for Culture, Goethe Institut, Institut Français, Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (ifa), Japan Foundation, Office for Contemporary Art Norway (OCA), and Wiener Festwochen. By collaborating in such partnerships, the Foundation receives the approval of this long list of international institutions, but the SAF does not publicize this information as much as Abu Dhabi does with the Louvre or the Guggenheim.

In addition to the building housing the Rain Room, another significant new structure is the Al Hamriyah Studios, located in the eponymous town on the northeast coast of Sharjah, and inaugurated in 2017 (

Universes n.d.). Local architect Khaled Al Najjar from the agency dxb.lab designed this modern structure on the site of an old souk. This fact highlights that even in the case of new constructions, Sharjah’s architecture, especially when used for an artistic or cultural purpose, both reflects and celebrates the local past.

Beyond the art milieu, among the various buildings used to house the different entities of the Sharjah Museum Authority (or SMA), five are new, more modern-looking constructions built by local, unremarkable architects. Two are new constructions, built in the 1990s, yet made to look much older: the Sharjah Art Museum has been built in the old style to remain in architectural harmony with the other structures in the center of town. Likewise, Hisn Khor Fakkan is a new building but made to look like the former nearby eponymous fort. Like the SAF’s use of pre-existing vernacular structures, the SMA uses four former 19th-century residences, an old fortress, a school, and an airport from the 1930s and, like the Al Hamriyah Studios, an old souk built in 1987.