Abstract

Fairy tales are often accompanied by illustrations that extend and complicate the messages of the text, and adapt it to the specific characteristics of different political and cultural situations. This article focuses on the images of one of the best-known fairy tales recorded by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, “Cinderella,” and looks for an answer to the question of how, in the second half of the 20th century, when the world was divided by the Iron Curtain, the socialist ideology attempted to make a “visual translation” of the story, which had been known for centuries, thus sending new aesthetic and political messages to adolescents. The emphasis is placed not only on the opposition of the roles of woman in socialist and capitalist societies but also on making the differences in appearance, behavior, and upbringing stand out.

1. Introduction

Fairy tales are extremely difficult to analyze since they have both a folklore (oral) and a literary (written) aspect (which are substantially different); they are intended for children but also for adults (as the different age groups interpret their content differently); they change depending on the cultural and social situation (i.e., some semantic layers of meaning are displaced by others); and last but not least, fairy tales are almost always accompanied by illustrations, which further complicate and extend the messages of the written text. These accompanying images, however, have remained out of the scholarly interest of the most eminent researchers of magical stories. Anthropologists and ethnologists such as Claude Levi-Strauss and Alan Dundes do not discuss them at all, while Vladimir Propp is definitive and explicit: “No matter how beautiful the illustrations in the books are”—he writes—“no matter how talented the authors are, they do not convey the essence of the fairy tale world... I think it is fundamentally impossible to illustrate fairy tales, since the events in them take place outside time and space, and fine art transports them into reality... Through illustrations, the fairy tale is no longer fantastical” (Propp 2000, p. 16). In the same vein is the opinion of psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, who believes that “the illustrated storybooks, so much preferred by both modern adults and children do not serve the child’s best needs. The illustrations are distracting rather than helpful. Studies of illustrated primers demonstrate that the pictures divert from the learning process rather than foster it because the illustrations direct the child’s imagination away from how he, on his own, would experience the story. The illustrated story is robbed of much content of personal meaning which it could bring to the child who applied only his own visual associations to the story, instead of those of the illustrator” (Bettelheim 1976, pp. 59–60). In contrast, modern scholars of fairy tales such as Jack Zipes, Maria Tatar, Ruth Bottigheimer, etc., view illustrated editions as much more favorable. However, we must not forget that those to whom we owe the literary versions of many folktales—Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm—did insist that their works be accompanied by images. The first illustrations of the well-known stories are the result of the joint work of talented artists and the writers themselves, who had their own requirements as to what parts of the texts needed to be visually interpreted.

Alan Dundes remarked that collective folklore differs from individual dreams. Dreams are different for different people, moreover, they are sometimes difficult to realize and define. “Folktales, in contrast, like all folklore, have past the test of time and are transmitted again and again. Unlike individual dreams folktales must appeal to the psyches of many, many individuals if they are to survive” (Dundes 1980, p. 34). If we focus on the idea that the essence of fairy tales, the archetype or the “nature constant” of the human psyche (in the words of Marie-Luise von Franz (1997, p. 17) is stable and unchanging, then the illustrations are part of those added elements that are impermanent and temporary. However, they are necessary because they function as a “time machine” and also as a “protective shell” that reflects the vanity of the epoch by not allowing anything temporary to reach the essence of the stories. Artists are “translators” of a kind who should render the content of the text according to the specific audience it aims at and the specific characteristics of the epoch that the audience lives in. The kernel of the fairy stories remains the same, but the details that indeed make the narrative “live” change—fashion is different, and that affects not only the attire and accessories but also the architecture, interior, manners, and even the food that is present in the everyday lives of the characters. The representation of nature also matters: it is set in conformity with the relief in the different parts of the world; the forest is not always dark and dense, and the mountain is not necessarily high and pointed. The illustrations mark, repeat, and reaffirm the main points of the story, but no matter how the artists endeavor to adhere to the narrative, they inevitably extend and adapt it to the national geographic, cultural, and folkloristic peculiarities.

This article is primarily a visual study, not an anthropological, semiotic, or folkloric study of fairy tales. It will focus specifically on the images that accompany the texts of two of the most famous fairy tales that have functioned for more than four decades in Bulgaria under the pressure of socialist propaganda. In this case, the illustrations became a kind of “shield” that bore the ideological blows while the core of the stories remained intact.

2. Fairy Tales, Illustrations, and Society

Regardless of what culture they belong to and what century they live in, children are never merely children. They are boys and girls. “The doctor”, Ruth Bottigheimer notes, “looks at a newborn baby and announces, “It’s a girl” or “It’s a boy.” However, at the moment of birth, a baby is a girl or a boy solely in sexual terms, not in social terms. Nonetheless, a process of gender socialization begins almost immediately. It is a process, that ultimately results in producing a child, who thinks, behaves and responds “like a girl” or “like a boy”. By adulthood, the gendering process has produced full-fledged men or women, each equipped with a voluminous knowledge of gender-specific and gender-appropriate behavior” (Bottigheimer 1999, pp. 71–106). According to Bottigheimer, in this process of “gender maturing” the illustrations accompanying the fairy tales that every child becomes familiar with since early childhood play an especially important role. The original texts might be reprinted almost identically all over the world, but the illustrations differ depending on the epoch in which they were made, the upbringing and culture of their author, and the expectations of the audience that they were intended for. In the same manner, the gender roles are learned and they vary in a broad range and between different human communities, and they change over time.

It is beyond any doubt that children can fantasize more than adults. Their notions are based both on the impact of the environment, their personal experiences, what they have already seen, heard, and read, and on some specific instinctive gender-related knowledge. What does Cinderella actually look like? We all take one fact for granted: she (as well as all remaining good female characters from the fairy tales of Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm) is beautiful. However, what does that mean? Beautiful according to the standards of what times and what society? Slim or plump, blond or brunette, pale or dark-skinned? The most famous of all fairy-tale beauties is actually described quite sparingly by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm. The authors’ attention is focused less on her physical traits than on her attire (Cinderella is not beautiful while she wears rags: she is just good). In all versions of the story, it comprises wonderful, glamorous dresses (without any details regarding the cut and the silhouette) and, naturally, slippers made of crystal, gold, or silver (but are they are low- or high-heel ones, mules, or shoes?). What is, however, the image that comes to our minds when we hear about the poor girl transformed into a princess? Does it correspond to the meager verbal descriptions or, on the contrary, does it emerge on the basis of other psychological processes that are more complex and stable in time? A slender and thin girl with a marked waist, with lush hair, pink-cheeked and full-lipped, dressed in a long, fluffy dress combining elements from many different fashion epochs: does not Cinderella look like that although no text presents her in such key details? Is that appearance a fruit of artistic imagination or is it in some notion, deeply rooted in the belief that girls should look a certain way in order to be successful in life (i.e., in order to be liked by the prince)? Can artists change such notions and subordinate them to other aesthetic rules? This study will focus the attention on the questions of how the authors of illustrations in Bulgaria make a “visual translation” of the Western texts telling about kingdoms, princes, and princesses, by adapting them to the moral norms and social peculiarities of the socialist society and how their attempts to introduce new aesthetic codes are received by the adolescents. This study is based on some of the most popular children’s books from the second half of the 20th century containing the fairy tale about Cinderella, which did not come to the young readers until they had passed through strict ideological control. The guiding method will be comparative, in which some of the peculiarities of the socialist illustration will stand out more vividly.

3. Chronological Frameworks and Ideological Specificities

In Bulgaria, similarly to readers all over the world, both the young and adults know and love the stories recorded by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm. In 1896, the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm were first published in Bulgarian1, two years before the fairy tales of Charles Perrault. The edition is richly illustrated, but no artist’s name is mentioned. In the early 20th century, various Bulgarian publishers published booklets, mostly with fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm. Most often, they are with no illustrations or their illustrations are borrowed from the original editions and their authors remain anonymous. It is interesting that in the period of the Kingdom of Bulgaria2, when princes and princesses were a topical subject, there was not even one image of Cinderella made by a Bulgarian artist. The heroine appeared for the first time on the pages of the books with the arrival of the new political system that had an extremely negative attitude toward the monarchy. Then, a crucial change began in the processes of preparation, printing, and dissemination of children’s books in the country3. The socialist rulers realized how easy it was to reach the hearts and minds of adolescents through literature and illustrations. In the years when the options for entertainment were limited, books became the closest friends of children, who dreamt, played, and fell asleep with them, who learned from them how to read, paint, and draw. “Children and teenagers are the best readers in our country. They make up almost 80% of the readers in mass libraries and this is quite proper. Our great expectations lie first and foremost in today’s children and adolescents—tomorrow’s new people of the socialist fatherland. And it is precisely for this reason that a little more effort must be made for them, also in terms of book publishing”—notes the statistical analysis of the books printed after 1944 (Tsvetanov 1952, pp. 43–44). The best artists were entrusted by the authorities with the responsible task of working in the field of illustrations for kids. Until the political changes that occurred in 1989, all publications in Bulgaria that contained the fairy tales of Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm were solely printed with illustrations drawn by Bulgarian authors. For almost four decades, there were only two exceptions, with two books that had the images illustrated by the Italian artists Gianni Benvenuti (Perrault 1958) and Roberto Sgrilli (Perrault 1974), which were reprinted many times, even in the 21st century. It is telling that it is precisely those publications, and not those illustrated by the socialist artists, that gained the attention and the affection of generations of Bulgarian children.

Communist authorities were suspicious of the fairy tales’ description of kingdoms, kings, princes, and princesses. Despite that, the works of Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm continued to be printed and reread by children. Naturally, there was criticism aimed at the content of the stories and their remoteness from the essentially important principles of socialist literature. “A great deal of the old fairy tales,” wrote a Bulgarian writer active in the field of children’s literature, “tell about kings and queens, of step-mothers and magicians, of misers and dragons, of dwarves and bad fairies… Haven’t some of them become shabby now? Isn’t it time for the new, modern-day fairy tale to resound in full swing? Would you say that the great transformations in our towns and villages, the cultural uplift, the flourishing of science and technology are not a source of inspiration?” (Avgarski 1967, p. 8). Another author, quite on the contrary, points out the “popular character of these stories” recorded out of the mouths of “alive, working people gifted to tell with skill and eloquence” (Karaliychev 1985, pp. 160–61). According to him they reveal “the most ancient forms of human verbal creation, one of the most durable monuments of people’s spirit manifested in the mythology of the oldest human history” (Karaliychev 1985, p. 161). Now, we already know that the informers of Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm were not always “working people” in a sense that was suitable for the authorities. However, it was thanks to the myth that readers in socialist Bulgaria had the opportunity to enjoy stories about kingdoms and palaces inhabited by handsome princes and beautiful princesses in a period when such topics were unknown and even dangerous for the proper citizens of socialist society.

4. Cinderella, Who Is Waiting for Someone to Rescue Her

Modern studies of fairy tales started in the 1970s alongside the struggles for equal human rights, anti-war protests, and the development of the feminist movement. Getting immersed in the fantastical world was not an attempt to escape the dramatic reality of that time, quite on the contrary, it was the result of the realization of the fact that fairy tales played an important role in the expansion of cultural conflicts and the unfolding of debates regarding social values (Haase 2008, p. ix). In 1973, Marcia Lieberman published her article, “‘Some Day My Prince Will Come’: Female Acculturation through the Fairy Tale”, (Lieberman 1972, pp. 383–95) where she formulated the thesis that fairy tales prepare girls from their earliest ages for traditional female roles in society by habituating them to obedience, humility, patience, and defeatist behavior. The fantastical narratives create notions that accompany children throughout their lives and often make them be prejudiced toward certain people, events, or circumstances: the stepmother is always evil, the youngest child is always neglected and their destiny is the hardest, only the beautiful girls succeed while the ugly ones are bad, marriage is the road to wealth, and life is a competition with only one winner since there is only one prize: a well-to-do man (Lieberman 1972, pp. 385–86). During the following decades, many more feminist studies dedicated to the fairy tales of Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm appeared, as their female authors presented a new reading of the well-known stories and began to cast doubt on their optimistic endings. One of the landmark works of the new feminist literary criticism was Judith Viorst’s quatrain entitled “And then the prince knelt down and tried to put the glass slipper on Cinderella’s foot”, in which the heroine acknowledges that she does not actually like the prince and in that order to avoid marrying him, she has the right to say that the slipper feels tight and does not fit her:

I really didn’t notice that he had a funny nose.And he certainly looked better all dressed up in fancy clothes.He’s not really as attractive as he seemed the other night.So I think I’ll pretend that this glass slipper feels too tight.(Zipes 1986, p. 73)

Instead of remaining passive and waiting to be chosen/saved, in Viorst’s version, Cinderella makes her own choice. She does not allow the events to drag her in a direction that is not in unison with her own notions of happiness. According to feminist female authors, since their early childhood, women are brought up to accept their dependency without a murmur, and the destiny of female characters in fairy tales clearly shows that. They always act as per another’s will: their father, mother or stepmother, brothers, or husband. In 1981, the famous US writer and psychotherapist Colette Dowling examined the network of repressive relationships and fears that keep women in a “half-light” and prevent them from making full use of their creativity and intelligence, bringing them together in the so-called The Cinderella Complex. Her book of the same title subtitled “Women’s Hidden Fear of Independence” (Dowling 1981a), became a best-seller. Dowling formulated the thesis that despite the freedom that women nowadays enjoy, women still prefer to let other, external factors determine their destiny and to passively await for something extraordinary to happen and “upturn” their lives. Since early childhood, they have been taught to believe that they are tender, delicate, and “fragile”, and that they need a male patron to give them the necessary protection, without which they cannot survive (Dowling 1981b, p. 47).

Although various interpretations of Cinderella’s story appear in the literature, including ones with twisted endings (see, for instance, Munsch 1980; Dahl 1982), the illustrations remain conservative. The female characters do not look like independent feminists when the fairy tale is preserved in its original form. There are marvelous examples from the past made by artists such as Walter Crane, Arthur Rackham, Anne Anderson, Charles Folkard, Edmund Dulac, Charles Robinson, Hermann Vogel, Jennie Harbour, and others, who are all known and loved by children from Western countries. They all depict Cinderella in a way that those flipping through the pages expect to see: elegant, tender, and wearing a long dress with her glamorous shoes glittering underneath. Such an appearance explains the behavior of the prince, who roams his kingdom far and wide looking for a stranger. The magic happens: the story thus presented is easy to believe.

5. Cinderella, Who Can Save Herself on Her Own

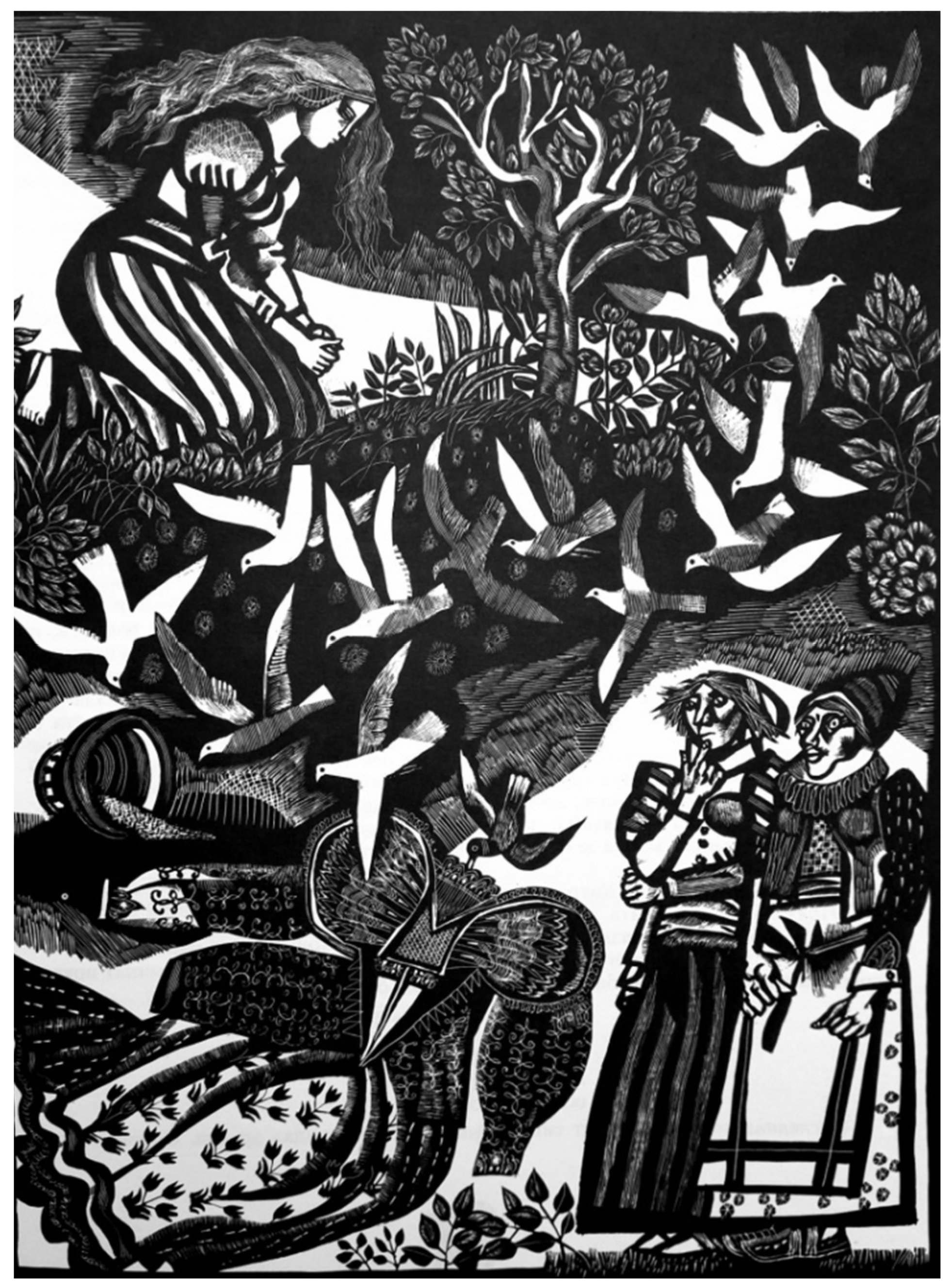

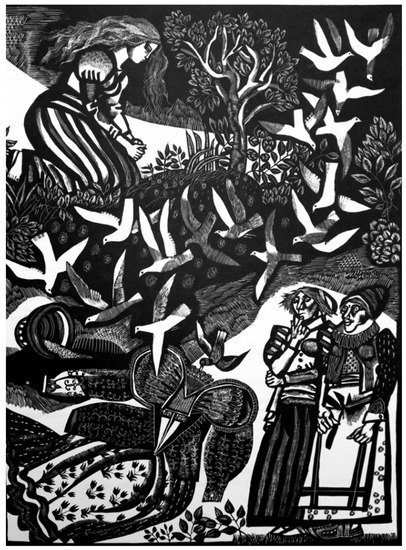

Regardless of what political conditions they are growing up under, all girls know two things about Cinderella for certain, that she is “beautiful” (as if her goodness remains in the background) and that she “becomes a princess”. Socialist children are no exception to this, although they have never seen a princess, even in a photograph. That notion, stubbornly presented as negative by the Communist Party, awakens in them associations that they keep deep inside themselves: romanticism, longing for another, a different life, glamour, retribution, happiness, justice, and love. The communist ideology has never put one’s appearance on a pedestal: quite on the contrary, what was always in the spotlight was the idea that a socialist woman is beautiful in another manner: educated, well-balanced, composed, tenacious, strong, rational, and prudent. This in no way means that girls do not actually notice, appreciate, and crave the other beauty that is attributed to the Western world. However, since their early childhood, they have been convinced that that kind of beauty does not determine their lives since it does not play a crucial role in socialist emulation. The concern over good looks is totally useless in a society that is not dominated by men. Bulgaria’s constitution, which was adopted in 1947, enshrines the idea of full equality for men and women in all fields of life. This equality of rights was effective by granting women, on an equal footing with men, the right to work and to equal pay, the right to vacation, social security, retirement pension, and education. Child care was paid for by the state, and the socialist woman was granted access to all economic fields. In this regard, both in terms of the long, paid maternity leave and the state-funded child allowances, etc., Bulgarian women achieved much earlier some objectives that have long remained inaccessible for women in the West. The feminist ideology in Bulgaria turned out to be needless, as the Communist Party was called upon to take the same care of all citizens of the socialist society who enjoyed equal rights. By mastering the male professions to a great extent, socialist women mastered the male manners, too. Their appearance also changed. While women were working on construction sites, in plants, or on the fields, they preferred comfortable clothes, and easy-to-maintain haircuts, they did not wear makeup, have manicures, or wear jewelry. The state made every effort possible to make women believe that since they were under the protection of the party, they could cope with everything without men’s help: studying, being self-supporting, raising their children, and developing professionally. Children’s books—through their texts and illustrations—habituate girls’ determination and independence from an early age. However, despite the party’s efforts to create a new literature that was adequate for the socialist reality, the adolescents preferred reading the stories of Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm much the same4. The authorities were unable to change the content of the fairy tales, but they could import additional meaning into them through the power of images. The exquisite and fragile Cinderellas adorning the pages of the Western publications were presented much more harshly, plainly, and decoratively in Bulgaria. It is hard to believe that the prince could fall in love with the robust, strong girls that do not look like they need to be saved; the main idea of the story is called into question (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Illustration of Perrault, Charles, Fairy Tales (Cinderella), 1968. Illustrated by Petar Chuklev, Sofia: Narodna Mladezh.

Figure 2.

Illustration of The Brothers Grimm, Fairy Tales (Cinderella), 1978. Illustrated by Stoyan Iliev, Sofia: Narodna Mladezh.

Figure 3.

Illustration of The Brothers Grimm, Fairy Tales (Cinderella), 1985. Illustrated by Rumen Skorchev, Sofia: Narodna Mladezh.

The readers’ attention is deliberately diverted in a new direction: aesthetic education. The authorities insisted that the young readers should meet “high art” not only in the galleries but also in their everyday lives. Since the socialist ideology puts reading on a pedestal, books became, quite naturally, the most convenient and easily controlled channel of influence on a large scale. The authorities were emphatic that their illustrations might not be liked by children, but nevertheless, they cultivated a high artistic taste in them. Ostensibly, ways were being sought to carry out a constructive “dialogue” between the artists and the young readers, but actually, a serious imbalance existed. Artists were presented as undisputable “authorities” and those who disliked or did not understand their creative work were presented as “ignorant”. “The superiority of Bulgarian illustrations for children over the illustrations of a number of other countries, as described in one of the programmatic articles, was due to the fact that our authors did not have to conform to commercial requirements. Quite a few publishing houses in the West made the artists create sugary works that attracted the parents’ non-sophisticated tastes. In Bulgaria, the artistic or publishing councils would not greenlight such works. […] There is another conflict, too: the one between the artists, on the one hand, and the educators and parents, on the other. The latter often claim that artists paint degenerate people and creatures, and are given the answer that it was not until they started to buy children’s books that it came to their minds to think about art, and therefore their judgments are completely false” (Dimitrov 1981, pp. 7–8). Over the years, the gap between the high criteria of the authorities and the unsatisfied expectations of the readers became larger and larger, and in the 1980s, the public already had the feeling that the artist’s work was first and foremost aimed at asserting themselves and not at reaching the hearts and minds of young children. According to a number of interviews and inquiries conducted among both the artistic milieu and the readers, “Bulgarian illustrations are ‘ugly’, a ‘parody of tastelessness’, ‘formalistic’ and ‘abstract’” (Radeva 2019, p. 53). Apparently, readers preferred the realistic, volumetric representations of characters, while in the second half of the 20th century, almost all Bulgarian illustrators worked in a decorative and plain manner, focusing their attention much more on the complexity of composition than on the psychological building of characters.

6. Conclusions

Indeed, it does not matter when the action in the fairy tale takes place or what epoch children perceive it to take place in, since the most important thing for the story’s magic to “work” is that beauty (which is identified by the children with happiness) should triumph. Princesses are beautiful, and their clothes too; palaces are beautiful, and so are the princes, even though it is as if they remain in the shade and their appearance is neither memorable nor identifiable. The future of the pair of lovers is also beautiful, or at least we believe it is. Every girl would want to be the princess. However, the girl chooses to identify herself with the princess not because of her good deeds but first and foremost because of her appearance. In practice, the child repeats what lies at the foundation of most fairy tales: the child prefers beauty and ignores actions. Different political systems might offer certain images of Cinderella, but they cannot make the girls identify with them. In Bulgaria, a number of inquiries conducted among the adolescents clearly show that children ignore the Bulgarian images and admire only the princesses drawn by the Italian artists, namely, Gianni Benvenuti and Roberto Sgrilli (Vasilev 1965, p. 42) (Figure 4). The fairy tales are not merely absorbing stories, if they were such, they would not have existed for so long. They are based on some deep notions and beliefs that, as it turns out, are not impacted by time or the political situation. At their homes, what the young Bulgarian girls imagine while looking at the illustrations, even for a second, is that they are fragile, vulnerable, and tender, but out of their homes, they live as strong, independent female citizens of the socialist society who are not controlled by their feelings. This imbalance between the desired and the real entails some serious psychological and social problems that shake the self-confidence of generations of Bulgarian women, even after the political changes in Bulgaria.

Figure 4.

Illustration of Charles Perrault’s The Little Red Riding Hood and Other Fairy Tales (Cinderella), 1958. Illustrated by Gianni Benvenuti. Sofia: Narodna Mladezh.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The fairy tale “Cinderella” is not included in the book. |

| 2 | The Kingdom of Bulgaria existed in the period 1908–1946. It came to an end in 1944, after the country’s occupation by the Soviet troops, and in 1946, Bulgaria was proclaimed the People’s Republic, which started to follow the experience of the USSR in all fields of political, economic, social, and cultural life. |

| 3 | In late 1947, private printing and publishing houses in Bulgaria were nationalized, and three years later, the “Chief Directorate of Publishers, Printing and Publishing Industry and Trading in Printed Matter” ran the creation and dissemination of all printed products in the country. |

| 4 | According to a survey conducted among 100 Bulgarian children of preschool age and first- and second-grade children published in “Detsa, izkustvo, knigi” (children, art, and books) magazine in 1980, the most read and liked fairy tales are the ones of Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, and, among those publications, the most popular were those that have more illustrations: (Kovacheva and Aleksieva 1980). |

References

- Avgarski, Georgi. 1967. [No Title]. Detsa, izkustvo, knigi [Children, Art, Books] 6: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bettelheim, Bruno. 1976. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Bottigheimer, Ruth. 1999. Illustration and imagination. In Fellowship Program Researchers’ Report. Available online: https://www.academia.edu (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Dahl, Roald. 1982. Revolting Rhymes. Illustrated by Quentin Blake. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov, Dimitar. 1981. Razvitie na bulgarskata iliustracia za detsa [Development of Bulgarian illustration for children]. Detsa, izkustvo, knigi [Children, Art, Books] 3: 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, Colette. 1981a. The Cinderella Complex: Women’s Hidden Fear of Independence. New York: Pocket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, Colette. 1981b. The Cinderella complex. The New York Times Magazine. March 22. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Dundes, Alan. 1980. Interpreting Folklore. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, Donald. 2008. Foreword to: Stone, Kay. In Some Day Your Witch Will Come. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, pp. ix–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Karaliychev, Angel. 1985. Skapotsenna ruda ot nedrata na narodnata dusha [Precious ore from the womb of people’s soul]. In Prikazki [Fairy Tales]. Edited by Grimm Brothers. Sofia: Narodna Mladezh, pp. 159–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacheva, Nadezhda, and Stefka Aleksieva. 1980. Predpochitaniyata na 5–6 godishnite detsa kam literaturata [The literary preferences of 5–6-year-old children]. Detsa, Izkustvo, Knigi [Children, Art, Books] 3: 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, Marcia. 1972. “Some day my prince will come”: Female acculturation through the fairy tale. College English 3: 383–95. Available online: https://www.jstor.org (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Munsch, Robert. 1980. The Paper Bag Princess. Illustrated by Michael Martchenko. Ontario: Annick Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perrault, Charles. 1958. Chervenata Shapchitsa i Drugi Prikazki [The Little Red Riding Hood and Other Fairy Tales]. Illustrated by Gianni Benvenuti. Sofia: Narodna Mladezh. [Google Scholar]

- Perrault, Charles. 1974. Pepelyashka [Cinderella]. Illustrated by Roberto Sgrilli. Sofia: Narodna Mladezh. [Google Scholar]

- Propp, Vladimir. 2000. Sobranie Trudov. Ruskaia Skazka. Moskva: Labirint. [Google Scholar]

- Radeva, Milena. 2019. Hudozhestvenata ilyustratsiya za detsa v Balgaria prez 80-te godini na XX vek [Artistic illustration for children in Bulgaria in the 1980s]. Problemi na izkustvoto [Art Studies Quarterly] 2: 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetanov, Tsenko. 1952. Bulgarskata Kniga sled Deveti Septemvri. Statisticheski Analiz, Izraboten ot Bulgarskia Bibliografski Institute [Bulgarian Book After September 9th. Statistical Analysis Made by the Bulgarian Institute of Bibliography]. Sofia: Nauka i izkustvo. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilev, Petar. 1965. Za esteticheskiya vkus na detsata i za ilyustratsiite na detskite knizhki [On children’s aesthetic taste and on the illustrations of children’s books]. Nachalno obrazovanie [Primary Education] 4: 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- von Franz, Marie-Luise. 1997. Archetypal Patterns in Fairy Tales Studies in Jungian Psychology by Jungian Analysts. Toronto: Inner City Books. [Google Scholar]

- Zipes, Jack. 1986. Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).