Abstract

William Pether (1739–1821) was a painter and skilled draftsman, whose abilities led to his becoming a master of engraving in the mezzotint technique—his prints reproducing works not only by the Dutch masters, such as Rembrandt van Rijn and his pupils Gerrard Dou and Willem Drost, but also by English artists such as Joseph Wright of Derby, Edward Penny, and Richard Hurlstone. An eminent British mezzotint engraver, he was also an underrated painter of miniatures. His artistic activity in this domain has been overlooked by scholars, who have focused on his print production; this study considers all extant miniatures produced by the artist during the period 1760–1820. The aim of this article is to present as many as possible known miniatures painted by this artist and to determine their proper attribution and dates through the use of stylistic analysis, the graphical-comparative method and handwriting research using available works of art and archival materials in the form of letters written by Pether.

1. Introduction

The miniature painting is a highly specialized field of painting in the world of art, whose characteristics were well delineated in 1739:

I will only add in a few words, the Peculiarities which distinguish it [miniature painting] from every other Species of Painting:

- It is more delicate.

- It requires a nearer View.

- It is not easily done but in Little.

- It is wrought only upon Velum or Paper.

- And the Colours are diluted only with Gum-water.

(Boutet 1739, p. 1)

Beginning in the early sixteenth century, miniature painting began to arouse interest as a new form of representation. Miniature landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits of saints became increasingly popular. At the same time, portrait miniatures gained in popularity. These were usually affixed to garments or everyday personal objects such as brooches, rings, medallions, pendants, caskets in veneer, book bindings, or snuff case lids. Initially, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, miniatures were often copies of works by famous masters depicting mythological and religious scenes, or portraits. At that time, such representations were known as limnings, or paintings in little; the term miniature first appeared in the seventeenth century (Foskett 1979, p. 18).

Initially, people preferred that miniatures be small enough to fit in one’s hand and to be pinned onto pieces of clothing. Eventually, they acquired larger dimensions—sometimes measuring up to a dozen centimeters. These were usually placed in a square or rectangular frame. Some of the first and best-known miniatures come from the first half of the sixteenth century, including the portrait of Anne of Cleves by Holbein (c. 1539) and the work Father of the Artist Richard Hilliard by Nicholas Hilliard (1577).1 Miniature painting flourished in Paris, Berlin, and London, where it enjoyed a notable evolution from the time of Henry VIII (1491–1547) to the second half of the nineteenth century.

The base on which miniatures were painted depended on the availability of materials, the artist’s preference, and the individual wealth of the client. Initially, only parchment was used2 and glued to the unprinted side of a playing card to stiffen and enhance the whiteness.3 The material changed only at the beginning of the eighteenth century, when Rosalba Carriera (1675–1757) used ivory for the first time.4 The dominant materials in England were ivory and paper (Day 1852, p. 11). By the end of the century, the technique of miniature painting on ivory had developed, with artists applying a thin paint layer, which allowed the refinement of representations.5

Miniature painting has long been considered an important field of art history; indeed, as early as the eighteenth century painting in miniature became a focus of scholarly research. Among the first important publications on the subject is The Art of Painting in Miniature (1752), which contains instructions on how to paint elements such as draperies, sky, and carnations, and how to choose the best color (Boutet 1739, p. 3).

Several nineteenth-century publications (Haywood 1890, pp. 69–70; Humphreys 1872, p. 132) also discussed miniature painting—among them, the letters of André Léon Larue (called Mansion), and works by Arthur Parsey, Emma Eleonora Kendrick, Nathaniel Whittock, and Charles William Day (Day 1852; Kendrick 1830; Mansion 1822; Parsey 1831; Whittock 1844). The early years of the twentieth century saw renewed interest in this topic by George Charles Williamson (Williamson 1904, 1921) and Heath Dudley (Dudley 1905), as well as significant publications by Cyril Davenport, who devoted an entire chapter in one of his books to a description of English miniatures of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Davenport 1908, 1913a, pp. 839–44; 1913b, pp. 825–30; 1913c, pp. 811–17). The post-war decades also witnessed a huge growth of interest in British miniature painting, as seen in the publications by Reynolds Graham, Torben Holck Colding, and Daphne Foskett (Foskett 1972; Graham 1962; Holck 1953).

Considering the relatively large number of publications on the history of miniature painting, it seems surprising that the miniature works of the title artist, William Pether, are not enough developed. The detailed state of research in this area will be presented in the further part of the article. Miniatures painted by the artist in the years 1760–1820 will be subjected to a stylistic analysis, and their proper attribution will be helped by the graphical-comparative method and handwriting research based on signatures in miniature portraits, engravings, as well as on handwritten letters and notes by William Pether from the collections of various archives. Before I analyze the works of this artist, however, let me quote a brief outline of the miniature painters’ environment in England in the eighteenth century, which will place the artist among the most renowned miniature painters of that period.

2. Miniature Painting in England

With the use of ivory now facilitating the process of creating miniatures, the number of accessories that could be decorated using small portraits began to increase. Until about 1760, no artists in England had dealt exclusively with miniature painting because it was regarded initially as amateurish—an occupation of people not directly connected with art or the artistic milieu, such as the valet Gervase Spencer or the pharmacist Samuel Cotes. However, engravers like Lake Sullivan and Thomas Frye also worked in miniatures, and around 1760, William Shipley founded a drawing school in London that taught miniature painting; his students included Richard Cosway, John Smart, and Richard Crosse.

With the founding of the Royal Academy of Art in 1768, London artists started showing their miniatures at exhibitions organized by associations such as the Free Society of Arts and the Society of Artists of Great Britain. Miniatures were also exhibited under the auspices of the Royal Academy. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the number of miniature painters had greatly expanded. As Przesmycki wrote:

The eighteenth-century miniature has completely new influences. First of all, after the theatrical manner of Piotr Lely and Gotffried Kneller, who influenced the last painters of the miniatures of the era (Flatman, Dixon) unfavorably, a new revelation in the art of portraying was introduced by Gainsborough, Romney, Lawrence, and especially Reynolds, who had a decisive influence on Cosway, Engleheart, and Ozias Humphrey.(Przesmycki 1912, p. 12)

Instead of its previous emphasis on power, dignity, and subjects of high seriousness, miniatures were now dominated by emotionality, lyricism, grace, and an elusive but refined charm, which carried with it a certain shallowness, superficiality, and glitz. The period is characterized by life-like representations of faces and a deep feeling for the spiritual side of the model. However, even though the miniature is now an accepted category of painting, many of its exponents have been forgotten by history, as is the case with William Pether. The main purpose of the article is to present Pether not only as an engraver, for which he is mainly known, but also as a miniature painter, presenting his work in this area, and analyzing and determining the proper attribution of miniatures, including those that are only attributed to this artist.

The most Important sources on Pether’s miniatures are catalogues from societies established in eighteenth-century London, such as the Free Society of Arts (FSA), the Society of Artists of Great Britain (SAGB), and the Royal Incorporated Society of Artists of Great Britain (RISA). SAGB catalogues consulted were from 1764, 1766, 1768, and 1780 (SAGB 1764, p. 9; 1765, p. 13; 1766, p. 10; 1768, p. 9). In the second half of the eighteenth century the Society was transformed into the Royal Incorporated Society of Artists of Great Britain (RISA), and for several years Pether exhibited portrait miniatures with them, with his participation recorded in 1769, 1770, and 1771 (RISA 1769, p. 9; 1770, p. 9; 1771, p. 11; 1777).

Insofar as he was recognized at all in the twentieth century, Pether was viewed more as a mezzotint engraver than a miniaturist. Algernon Graves, in his 1906 dictionary of contributors covering all exhibitors at the Royal Academy of Arts, called Pether only a “Miniature Painter” (Graves 1906, p. 114). In another Graves dictionary covering exhibitors at the Society of Artists of Great Britain and the Free Society of Arts in the years 1760–1791 and 1761–1783, Pether was called an “Engraver and Miniature Painter” (Graves 1907, pp. 196–97). An author provided a full list of his works exhibited at the societies and also recorded the addresses where the works of art were made or sold. In 2021 David Alexander mentioned Pether in his dictionary of British and Irish engravers but only called him a portrait painter (Alexander 2021, p. 691).

Few scholars have addressed the subject of Pether as a miniaturist. In 1909, F. M. O’Donoghue noted only, “He was also an excellent miniaturist” (O’Donoghue 1909, p. 967). In Emmanuel Bénézit’s dictionary there is likewise only a single sentence: “He was a pupil of Thomas Frye and painted portraits in oils and in miniature” (“Il fut élève de Thomas Frye et peignit des portraits à l’huile et en miniature”) (Bénézit 1948, p. 623). Neil Jeffaer Dictionary of Pastel & Pastellists (2021) mentions Pether’s miniatures only in a passing note: “He also worked in miniature, oil and crayon” (Jeffaers 2021). In 1929, Basil S. Long was the first to focus more closely on Pether as a miniaturist, identifying him as having “Executed miniatures, oil and crayon portraits, mezzotints, etc.” (Long 1929, p. 338). He also remarked on a miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection, signed with the monogram WP and attributed to Pether, noting that “It has red touches on the eyelids, etc.” He also notes a miniature of a man made by the same artist, owned by the Duke of Portland. This is the sole publication where Pether’s miniatures are described in any detail.

Pether has sometimes been mentioned in publications devoted specifically to miniatures. The first is The Miniature Collector (1921) by George Charles Williamson, who identifies Pether as an artist responsible for occasional portraits in pencil, plumbago, or crayon (Williamson 1921, p. 213). Pether received more attention from Daphne Foskett, who illustrated a miniature by Pether, identifying it as A Portrait of a Man: Richard Cavendish, from the collection of the Duke of Portland—the only instance where a miniature picture by Pether is reproduced (Foskett 1979, p. 347).

3. William Pether—Mezzotint Engraver and Miniature Painter

William Pether was a painter and skilled draftsman, whose abilities led to his becoming a master mezzotint engraver—his prints reproduced works by Dutch masters, including Rembrandt van Rijn and his pupils Gerrard Dou and Willem Drost, and by English artists such as Joseph Wright of Derby, Edward Penny, and Richard Hurlstone. In addition to his artistic activity, he also published engravings and set up branches of his business in several places in London and in the provinces. He was skilled artistically as well as technically. At the end of his life, he taught drawing, engaged in paper conservation, and developed technical projects such as the “Apparatus to promote the escape the smoke” (Cora 2021, p. 298; Pether 1804).6

Pether’s miniatures form a separate group, one that has not been adequately described. Generally, William Pether was listed primarily as an engraver and only occasionally as a miniature painter. Only in the Royal Academy catalogue he is described as a miniature painter. Between 1761 and 1763, under the patronage of the Free Society of Arts, Pether exhibited only one miniature. It is probably thanks to the teachings of his master, Thomas Frye, who also dealt in the creation of “paintings in little,” that he set out on his path as a miniature painter. In the mid-eighteenth century, Frye produced several male portraits. In a miniature from 1761, there appears a background similar to one described by Long and the monogram of the artist “TF.” The catalogues of the Society of Artists of Great Britain and the Royal Academy contain much information about the miniatures Frye produced. Pether painted miniatures mainly in watercolor on ivory. Initially, they were small, 3–4 cm long, but later reached 8–15 cm.

Table 1 below summarizes the data regarding Pether’s miniature work thus far obtained. He may have begun painting miniatures during his time with Thomas Frye, but initially, he only exhibited drawings. Not until 1763 were his miniatures, mainly portraits, exhibited publicly. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, miniature painting represented mainly men; only in the second half of the eighteenth century did representations of women become popular. One of the most important female miniatures of this period, a portrait of Queen Charlotte based on Frye’s engraving, is often described also as based on the mezzotints of William Pether (Pointon 2001, p. 49).7

Table 1.

William Pether’s miniatures exhibited at the Free Society of Arts, the Society of Artists of Great Britain, and the Royal Academy of Arts.

4. A New Light on the Attribution of the Artist’s Miniatures

Cynthia Walmsley, a specialist dealer in portrait miniatures, silhouettes, and portraits from Nottinghamshire, identified the earliest Pether miniature hire, Portrait of a Man, created around 1765.8 This might be a miniature from the FSA exhibition of 1763 or a portrait from the SAGB exhibition of 1766. It has a uniform background similar to those that appear in Frye’s portraits. Pether’s singular way of developing the background using small, characteristic lines is similar to Portrait of an Unknown Man by Frye, currently owned by Ellison Fine Art, miniature portrait specialists in London. In addition, Walmsley claims that the man’s clothing—a brown jacket and vest, a white shirt, and a stock tie—is typical of that worn before 1765. The same arrangement of the stock tie and the wrapped collar appears in Frye’s miniature from around 1758. The way in which the background was painted, as well as the presentation of the same elements of clothing as Frye, may indicate that the miniature was painted by Pether because he had a very close relationship with his master, from whom he undoubtedly learned to paint miniatures and decorate bow porcelain (Cora 2021, p. 290).

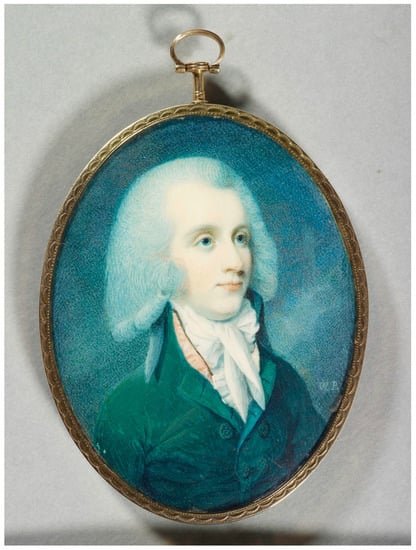

Portrait of a Young Man (1770), located in the Portland Collection in Nottinghamshire, is signed and dated “W. Pether 1770,” which may indicate that it is the same portrait as that exhibited at the SAGB in that year. Bridgeman Images contains a miniature described as being by William H. Patten (d. 1843), despite the fact that it contains the inscription “W. Pether 1770.” The miniature depicts a young man with a light complexion, deeply flushed cheeks, and hair arranged in a manner similar to that in the 1765 miniature. Furthermore, the poses of the figures in the 1765 and 1770 miniatures are almost identical. The men were presented with their heads in three-quarter view turned to the right and wearing similar clothing: jackets with buttons and a wrapped collar. This may suggest that the same compositional sketch was reused formulaically, introducing individual characteristics to the person portrayed. Daphne Foskett identified the figure as Lord Richard Cavendish (1752–1781), stating that it was in the collection of Countess Portland (Przesmycki 1912, p. 157). Goulding similarly connects the man portrayed with Lord Cavendish: it may thus be one of the miniatures from the Duke of Portland’s collection, about which Long wrote (Goulding 1914–1915, p. 157; Long 1929, p. 338). Cavendish, an English nobleman and politician, was a son of William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire (1752–1781). Cavendish was much younger in Pether’s miniature. Cavendish was about 18 years old when the portrait was made, although the engraving is dated to the last year of his life. It is also possible that Cavendish’s miniature portrait was commissioned from the artist through contacts between Pether and Lord William Ponsonby, 2nd Earl of Bessborough (1704–1793), for whom Pether engraved mezzotints between 1765 and 1770. Ponsonby’s wife, Lady Carolina Cavendish (1719–1760), was the aunt of Richard Cavendish and the sister of his father. The miniature can be given a new title—Portrait of Lord Richard Cavendish (1752–1781). A similar way of presenting the figure, its clothes, and the way the details such as hair and buttons are painted, can confirm that both miniatures—Portrait of a Man and Portrait of Lord Richard Cavendish—were painted by Pether.

The collection described as “Three portraits; in miniature” dated 1771 in the above Table 1 includes a potential self-portrait of the artist. This is one of only two self-portraits that Pether made—the first, a mezzotint, dates to the second half of the eighteenth century.9 Despite the brief inscription, which bears only the name “Don Mailliw Rehtep”—"William Pether” backwards—it likely dates to 1777, the year it was exhibited for the first time under the aegis of the Society of Artists of Great Britain (RISA 1777).10 Pether appears as a middle-aged man with dark hair and what seems like a false moustache. The second dates to between 1770 and 1780 and shows a middle-aged man wearing a grey wig and holding a pencil and card stand in his hands. In the background are an easel and palette. The painting now forms part of the Thomson Collection, the Art Gallery of Ontario.11 This is the only square-format miniature by Pether; the others are mainly round or oval.

The years 1780–1783 saw the creation of several female portraits. One of these, Portrait of a Woman, with the head turned to the left with a contemporary coiffure, is dated around 1780. The colors of the miniature are not known but the description indicates that she wears a blue dress and an ermine collar.12

Noteworthy is a group of Pether’s miniatures created in the second half of the eighteenth century and identifiable by the peculiar development of their background, in which light–shadow transitions created by delicate hatching are visible. In Pether’s miniatures, the light always comes from the left side of the portrayed person, and the hatching with the use of light–shadow does not create a perfectly smooth background, but naturally refers to the shape of the clouds. Signatures of the artist “W.P.” appear on the miniatures from this period, which will be discussed. Portrait of a Woman (Figure 1), after the drawing by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun from 1777,13 represents Marie-Joséphine-Louise de Savoie, Comtesse de Provence (1753–1810), whose portrait (as well as that of her husband Comte de Provence, and later Louis XVIII (1755–1824), King of France, was also engraved by Pether in the mezzotint technique in 1778.14 An engraving of this miniature is in the British Museum,15 with additional prints in the Royal Collection Trust.16 The engraving was published on 9 November 1778 by the most eminent publisher of the day, John Boydell (1720–1804). Further confirmation is provided by the handwritten inscription on the print: “Published 9 November 1778 by John Boydell Engraver in Cheapside London” (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

William Pether, Portrait of Marie-Joséphine-Louise de Savoie, Comtesse de Provence, c. 1778, watercolor on ivory, 101.6 × 79.4 mm. Private collection. Credit line: Stam Gallery, Hewlett NY.

Figure 2.

William Pether, Madame, 1778, mezzotint, 349 × 278 mm. Royal Collection Trust, London. Credit line: Digitized by Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022.

Pether engraved the Comtesse with a careful eye for detail and special light effects, notably on the big, striped bow fastened across her breast and the patterning of light and shade across her face. The miniature shares the same distinctive style as the engraving, reinforcing an attribution to Pether. Painting a picture based on a drawing requires the artist to choose colors. Pether shows the Comtesse in a blue dress with orange details, including a bow on the bodice. The same bow, in white and light blue, appears on Marie Antoinette with a Rose (1783) by Vigée Le Brun. This miniature is signed “Pether” in the lower left. On this basis, the title can be changed to “Portrait of Marie-Joséphine-Louise de Savoie, Comtesse de Provence” and is dated to around 1778.17

The four other portraits from the same group depict male sitters on oval plaques, with the same “W.P.” signature appearing on the lower left side. The Victoria and Albert Museum’s Miniature Portrait depicts a middle-aged man with a light complexion, posed with the head turned towards the right and wearing a jacket with the same number of buttons and a folded white stock such as in the above-described miniatures from circa 1765–1770.

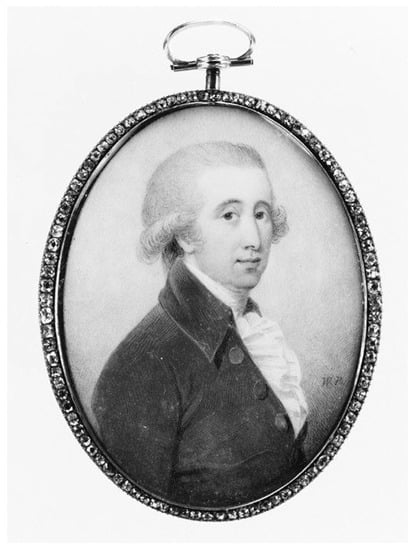

Graham Reynolds attributed Portrait of a Man to Pether in 1969, noting that the orthography of the signature corresponded to that on the V&A’s miniature (MET 1996, p. 129) (Figure 3).18 It shows an unknown male posed in three-quarter view and with draftsmanship and brushwork similar to the following two miniatures. This man has brown eyes and powdered hair and wears a grey-brown coat and white frilled shirt. The MET catalogue notes that, “The original gilt frame is set with brilliants. Decorative borders are etched on the gilt back, and in the center an oval glass covers the gold initials FM surmounted by a crest. In the backing is a trade card for an inn at Lyncombe near Bath” (MET 1996, p. 128). There is a signature of “W.P.” in black on the right side of the miniature, and the mentioned gold initials “FM” may refer to the person who ordered the portrait at that time or was its owner.

Figure 3.

William Pether, Portrait of a Man (A Man with the Initials FM), latter half of the 18th century, watercolor on ivory, 75 × 56 mm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Credit line: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Open Access policy.

The third, Portrait of an Officer, depicts a young man in a military officer’s uniform: a scarlet coat with a blue lining, gold lace, buttons and epaulettes, and a frilled white shirt and black stock tie (Przesmycki 1912, p. 245).19 The man wears a similar red coat to that depicted by Charles Jagger (1770–1827) in Portrait of an Officer, though with one crucial difference: the lace, buttons and epaulettes of Jagger’s officer are painted silver rather than gold.20 To identify the person depicted in the painting, it is necessary first to identify the particular uniform and compare it with other uniforms. The Yale Centre for British Art owns a painting by John Hoppner (1758–1810) entitled An Unknown British Officer21, dated (c. 1800). Most importantly, it assigns the British officer to the 11th (North Devonshire) Regiment of Foot (Wickes 1974).22 The figure in the portrait has the same uniform as that depicted on the miniature—scarlet/red coat, blue lining, gold details. Care must be taken, however, in connecting the appearance of the uniform with the Regiment, and this issue will require additional research. Nonetheless, it strengthens the hypothesis that the miniature was likely painted between 1790 and 1800. This painting also carries the signature “W.P.”, placed in a comparable position. Long wrote:

I have seen a miniature of an officer in a red coat signed W. P. in sloping Roman capitals, (c. 1793). The background was painted with long blue strokes, some curved, running in various directions, the hair was painted with long blue strokes and a few stippled lines; the face was shaded with blue, delicate hatchings, but there was a little red at the eyelids and corner of the eyes and at the cheek, mouth, and base of the nose.(Long 1929, p. 338)

This description could belong to the one miniature depicting the officer. This carries the “W.P.” signature, and the miniature itself may well have been made around 1793. Long stated, in addition, that the head of the figure was slightly larger than his torso, and the background was crisscrossed with long blue lines. This method of covering the background around a portrayed figure with wavy lines and intersecting lines enriched by a chiaroscuro modeling was characteristic of Pether when dealing with backgrounds.23

The fourth item in this group, Portrait of a Gentleman, belongs to the Royal Collection Trust in London. On the reverse of the miniature is the inscription “NHD” (Figure 4). The identification of the subject based on this inscription is a matter of speculation. The interlaced letters “NHD” may suggest a reference to the painter Nathaniel Dance (Figure 5). However, Dance began using his wife’s name, Holland, after 1800, which indicates that between 1780 and 1790 he could not be identified with these initials. In addition, this figure has blue eyes, which does not correspond to the brown color recorded by Dance on a self-portrait from 1773.24 The likeness also differs from that executed by Angelika Kauffmann in 1764.25 The above letters, which appear on the reverse of the miniature, seem more likely to be the initials of the person to whom the item belonged.

Figure 4.

William Pether, Portrait of a Gentleman (Portrait a Man formerly called Sir Nathaniel Dance Holland (1734–1811), c. 1790, watercolor on ivory laid on card, 90 × 70 mm. Royal Collection Trust, London. Credit line: Digitized by Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022.

Figure 5.

Portrait of a Gentleman (Portrait a Man formerly called Sir Nathaniel Dance Holland (1734–1811). Reverse with monogram “NHD”, c. 1790, watercolor on ivory laid on card, 90 × 70 mm. The Royal Collection Trust, London. Credit line: Digitized by The Royal Collection Trust, London.

Each of the three miniatures in question contains the same monogram; but the signature is problematic in that it can be attributed to several artists. One is William Prewett (1699–1759), a painter of miniatures and a student of C. F. Zincke. He is, however, unlikely to be the author of miniatures on ivory since he worked mainly in enamel in the years 1735–1750. Around 1789, however, two other artists using this signature were active. One was the Irishman William Palmer (1763–1790), and the other, William Pether.

Since Pether is known for signing by way of joint initials, he the most likely author of the miniature. On this basis, one can assign the authorship of the above three miniatures, distinguished by the monogram “W.P.”, to William Pether. These portraits are characterized by a singular manner of treating the background—using small, overlapping lines—as described by Long. The background of each of these paintings is characterized by chiaroscuro lightening in the same area of the portrait, as well as in the area of the signature, which suggests that they had the same author. A similar approach is notable in other miniaturists of the period: Horace Hon, Portrait of a Man (1785); Philip Jean, Portrait of a Man (1790); Anker Smith, Mr. John Bowyer (1790); Diana Hill (1795), and John Bogle (1800). At the end of the eighteenth century, sitters are presented in greater detail, and their backgrounds change to a chiaroscuro sky with increasingly visible clouds. This treatment emerges in miniatures from around 1800 by William Wood, Richard Cosway, John Wrimp, and Thomas Hargreaves. In the nineteenth century, landscapes and marine scenes began to make their appearance as backgrounds in miniatures by painters such as Taglilini (1822) and Reginalda Easton (1850).

One of Pether’s later miniatures is a round plaque, Portrait of a Man, signed and dated “Pether 1797”.26 It is probably one of the last miniatures made by the artist. The subject is reduced and adapted to the composition, and various dashes and chiaroscuro effects appear in the background, which never occurs in his earlier works. The miniature shows a middle-aged man with grey hair and blue eyes wearing a dark jacket and white vest with floral green elements and a white foulard. The way of creating the brown-grey background resembles that of the other three miniatures dated to the last quarter of the eighteenth century with the signature “W.P.”: Portrait of a man, Portrait of an Officer, and Portrait of a Gentleman.

Towards the end of the century, a new type of miniature came into being—small plaques in which only the eye was depicted. These eye miniatures were painted mainly in watercolor on ivory. Portraying a single eye of a family member, child, or loved one, they adorned medallions, brooches, bracelets, rings, and small boxes, and were often surrounded with precious stones, pearls, and gold frames. Such miniatures became popular, allegedly, thanks to the Prince of Wales, who had Mrs. Fitzherbert’s eye painted by George Engleheart (1750–1829), and other artists including Richard Cosway (1742–1821), William Wood (1769–1810), and Charles Hayter (1761–1835) (Foskett 1979, p. 25). These miniatures had their origin in ancient Egypt, where the eye was used as an amulet of the sun god Ra. To this day, belief in the Evil Eye still exists, based on the assumption that the gaze from such an eye can bring suffering, illness, and death (Gordon 2001, p. 526). In early-eighteenth-century France, inspired by examples imported from the East, the symbol of the eye acquired political significance. Around 1793, supporters of the French Revolution used it as a means of personal identification, placing the symbol on a variety of accessories (McClenehan 1930, p. 29). One of the last paintings in miniature by Pether is just such an eye miniature, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It is set inside the lid of an oblong ivory case, lined with red velvet, and with a mirror inside the top half of the case. Under the miniature is set a piece of paper with the inscription “27th Jan’y 1817. W. Pether”—with 1817 evidently being the date the work was painted (McClenehan 1930, p. 28). The miniature depicts a blue left eye with a light brown eyebrow, on natural-colored skin with grey shading; also shown is a light pink lacrimal gland. As noted, this was one of the last works of art executed by Pether before his death in 1821. Between 1800 and 1821, when he moved from London to Bristol, he engraved several mezzotints, such as Cottagers Pigs (1803), Portrait of Samuel Seyer (1816), and Portrait of Edward Colston Esq. (1817).

5. Conclusions

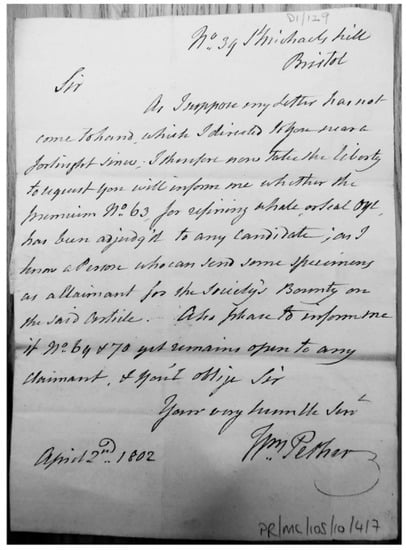

William Pether’s miniatures can be divided into two groups. The first group includes a visible signature. Pether adopted three forms of signature for his works: “W. Pether,” “Pether,” and “W.P.” To be sure of our conclusions, all signatures must be compared with Pether’s style of writing and orthography. His signature can be found on handwritten documents in various British archives. The Nottinghamshire Archives hold Pether’s marriage certificate to Elisabeth Cook in 1776, which includes his signature (Pether 1776); in the Royal Academy Archives is a letter written by Pether to James Paine (Pether 1770); and in the collection of the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) Archive are two letters sent from Bristol with signatures (Pether 1801, 1802) (Figure 6). The same signature appears on the Floral Design and Decorative design in colour, also from the RSA Archive (Pether 1758, c. 57) (Figure 7). The evidence of Pether’s signatures on these documents offers clear proof that the eye miniature (1817) was painted by the artist. The inscription on the piece of paper placed below the miniature bears the same signature as the Floral Design. The handwriting of numbers and letters on the miniatures Portrait of Marie-Joséphine-Louise de Savoie, Comtesse de Provence, Portrait of Lord Richard Cavendish (1752–1781), and Portrait of a Man also closely resemble the hand seen in Pether’s letter to James Paine.

Figure 6.

William Pether, Letter from William Pether about refining whale oil, 2 April 1802. Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Archives, London. Credit line: Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Archives, London.

Figure 7.

William Pether (1757), Flower Design, Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Archives, London. Credit line: Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Archives, London.

These two types of signatures correspond clearly to those of the artist; the third type, however, is more speculative. Although the most interesting paintings in this group are miniatures with the signature “W.P.”, their attribution to William Pether is less certain. However, two Pether engravings have the inscription “W. Pether fecit.” Unlike mezzotints that have inscriptions added by the publishers, these may well have signatures furnished by the artist himself. A Farrier’s Shop (1771)27 and An Academy (1772),28 both engraved after Joseph Wright of Derby paintings, carry the signature “W. Pether”. The other instance is a handwritten signature, “W. Pether”, on a porcelain jug, now in the British Museum.29 The configuration of the capital letters on the mezzotints and porcelain, “W” and “P”, closely resemble the style of the letters painted on the miniatures Portrait of a Man, Portrait of an Officer, and Portrait of a Gentleman.

The second group consists of miniatures that carry no inscriptions: Portrait of a Man, dated by Cynthia Walmsley to 1765; and Young Lady, probably from 1780. For the first of these, if we rely on the knowledge of Walmsley and the style of composition, draftsmanship, and brushwork in the painting, we might assume that the portrait was painted by Pether. However, authorship of the other miniature, the portrait of the young woman, cannot be firmly connected to Pether without further information on the artwork, which remains in private hands.

The subject of miniatures is one of the most interesting and challenging fields of art history to research. Based on the information so far collected, we can conclude that of the nearly twenty miniatures listed in the Table 1 and exhibited in public in the second half of the eighteenth century, eleven of them have now been identified. Nine miniatures described in this article can be attributed to William Pether. The discovery and attribution of these miniatures to a barely known miniaturist and engraver are significant, not only for the history of British miniature production and British art, but also for the auction market. Further research remains in order to date and establish correct attributions for the miniatures in the second group of Pether’s paintings. Research such as non-invasive scientific methodology, comprising of stereo and optical microscopies, Raman microscopy, and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy may be a continuation of research on William Pether miniatures, which in the future could help to better understand its production and solve attribution problems, not only Pether’s “paintings in little”, but also many other artists of the modern period.

Funding

This research received external funding: Jagiellonian University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Michelle Facos and Howard Davies, coordinator of The Robert Anderson Cheritable Trust in London, for their invaluable help and patience. I owe thank to Evelyn Watson, Head of the Royal Society of Arts Archive in London for providing all archival documents.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | He is also author of the treatise “Of Limning”, a manuscript at the University of Edinburgh. Typical of these miniatures is that they show the bust of the portrayed person en face as well as en trois quart. The portrayed persons fill the entire composition, as in the modern “law of the frame”. There are no free spaces here, and a uniform background occupies a small part of the entire metal surface, on which, sometimes, inscriptions are included. Portraits of men dominate and are characterized by lack of shading, little visual depth, matte complexions, and richly ornamented costumes. In Paris circa 1700, miniatures were created by the Flemish miniaturist van Blarenberghe and later Klingstedt, also referred to as “Raphael des tabatières”. |

| 2 | As a base for miniatures, sheep or calf parchment (vellum) or pecorella (stillborn lambs’ skin) was used. Over time, the use of cardboard, the reverse side of playing cards, paper, silk, tree, metal sheets (zinc, copper, silver, gold), enamel, corner, tortoise shell, porcelain, glass, and ram’s bones began to be popular. Ivory was the last base adopted, ultimately supplanted in the second half of the nineteenth century by the invention of the Daguerreotype. In addition to these major types of base, there were also miniature paintings on lace, wax, and stearin plaster. |

| 3 | In addition to this method, another technique, table bookleaf, created a plate by covering parchment with a layer of gesso on both sides. This allowed the parchment surface to be stiffened and smoothed. In addition, it was also possible to increase the size of the miniature. Each artist had their own way of developing pigments, but the most common was gouache and watercolor. Pigments were combined with a binder, usually acacia gum or gum Arabic. |

| 4 | She began painting miniatures for the lids of snuff boxes and was the first painter to use ivory instead of vellum for this purpose. Thanks to this material, which initially had a thickness of 1–2 mm and was later decreased to 0.1–0.2 mm, the paint layer could be thinner, lighter, and more delicate. |

| 5 | One of the first British artists to start using ivory as a foundation for miniatures was Bernard Lens (1682–1740). However, the main breakthrough in miniature painting was made by Richard Cosway (1742–1821), who introduced a new way of using watercolors on ivory so that they looked natural—like watercolor on paper. Over time, parchment fell out of use, and the widely available paper began supplanting the much more expensive ivory. |

| 6 | Pether, despite being an engraver, publisher, and miniaturist, invented an “Apparatus to promote the escape of smoke” (from the chimney). This 1804 invention got a patent and was fully described in 1804 (Pether 1804). |

| 7 | Miniatures representing Queen Charlotte and King George III were also painted by Jeremiah Meyer: an oval miniature on a bracelet with a representation of George III from 1761, and a watercolor on ivory entitled Queen Charlotte and dated 1770. In 1789, William Pether engraved Portrait of Jeremiah Meyer, now in the British Museum, London (1902; 1011.3639). |

| 8 | It is difficult to recapture information published on the Cynthia Walmsley website (www.c-walmsley.co.uk), since it ceased to exist two years ago. The information quoted came from private research conducted several years ago. It is not possible, at present, to corroborate the source of these details. |

| 9 | William Pether, Mr William Pether Engraver, mezzotint, 366 × 274 mm, British Museum, London (1852; 0214.312). |

| 10 | “Don Mailliw Rehtep/pinxit et Fecit/Will. Pether Engraver”. |

| 11 | William Pether, Self-portrait, c. 1770–1780, mezzotint, Art Gallery of Ontario (AGOID.106997). This miniature was offered for auction at Galerie Fischer in Lucerne (lot 843) and then sold by Christie’s, London (lot 176), on 27 November 2007 (Christie’s 2007); (Fischer 1960). It was estimated at GBP 6000–8000 and the final price was GBP 10,000. |

| 12 | The portrait was sold at the Halls Fine Art auction of Miniatures & Works of Art at Shrewsbury on 13 November 1996 (lot 352) and is now part of a private collection (Halls Fine Art Auctioneers Shrewsbury 1996). |

| 13 | Elisabeth-Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Portrait of Madame, Comtesse de Provence, 1777, drawing, Royal Collection Trust, London (RCIN 913123). |

| 14 | It is important that not all of William Pether’s engravings have signatures (pinxit, fecit) but this one has the signature “W. Pether.” This signature, verified, appears on the other mezzotints. |

| 15 | William Pether, Madame, 1778, mezzotint, British Museum, London (1902; 1011.3645). |

| 16 | William Pether, Madame, 1778, mezzotint, Royal Collection Trust, London (RCIN 617550). |

| 17 | The provenance and history of the miniature is unknown; it is also said to have come from a private collection and was sold by Stam Gallery Appraisers, Washington, NY, in early 2016 and then by Shannon’s Fine Art Auctioneers in Milford, CT, on 27 October 2016 (lot 98), with an estimated value of USD5000–7000. It is now part of a private collection (Shannon’s Fine Art Auctioneers 2016). |

| 18 | Portrait of a Man belongs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and was donated in 1968 by Lilliana Teruzzi (MET 1996). |

| 19 | A stock tie is a form of neck-cloth that was often stiffened and usually close-fitting, formerly worn by men but also used in military uniforms. |

| 20 | “An Officer, Wearing Red Coatee, With Blue Facings, Cuffs and Standing Collar”. Mutual Art. Available online: https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/An-Officer--wearing-red-coatee--with-blu/1DF54E2ECFB0C028 (accessed 12 October 2019). |

| 21 | John Hoppner, An Unknown British Officer, c. 1800, oil painting, Yale Center for British Art (B1977.3), New Haven, CT. |

| 22 | Preceding and later titles: 1685—The Duke of Beaufort’s ‘Musketeers’, 1751—The 11th Regiment of Foot, 1881—The Devonshire Regiment. |

| 23 | The miniature was sold at Sotheby’s on 26 June 1978 (lot 188), and then again at Christie’s on 14 October 1988. It is now (since 2009) part of the Comeford Collection at the Irish Architectural Archives in Dublin (Sotheby’s 1978). |

| 24 | Nathaniel Dance, Self-portrait, 1773, National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 3626). |

| 25 | Angelica Kauffmann, Nathaniel Dance, 1764, Victoria and Albert Museum in London (E.384-1927). The Royal Collection Trust indicates the date of the drawing as 1764, whereas the V&A dates it around 1790. |

| 26 | Half-length portrait of a man, wearing a black coat and vest with embroidered silk lapels. The miniature was sold by Millon & Associés in Paris on 17 June 2016 (lot 189), with the title Portrait d’homme en buste portant un habit noir et gilet avec revers en soie brodé (Millon 2016). |

| 27 | William Pether, A Farrier’s Shop, 1771, mezzotint, British Museum, London (1870; 0514.485). |

| 28 | William Pether, An Academy, 1772, mezzotint, British Museum, London (2010; 7081.2228). |

| 29 | Pether was a scholar of Thomas Frye, who taught him porcelain painting (Cora 2021, p. 290). |

References

- Alexander, David, ed. 2021. Pether, William (c.1738–1821). In A Biographical Dictionary of British and Irish Engravers 1714–1820. New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon’s Fine Art Auctioneers, ed. 2016. Fine American and European Paintings, Drawings, Prints and Sculpture. 27 October 2016. Milford: Shannon’s Fine Art Auctioneers. [Google Scholar]

- Bénézit, Emmanuel, ed. 1948. William Pether. Dictionnaire Critique et Documentaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs. Paris: Librairie Grund. [Google Scholar]

- Boutet, Claude. 1739. The Art of Painting in Miniature. London: J. Hodges. [Google Scholar]

- Christie’s, ed. 2007. Live Auction 7453 Important Portrait Miniatures and Gold Boxes Lot 176 ‘William Pether (British, 1738–1821). London: Christie’s. [Google Scholar]

- Cora, Dominika. 2021. New Light on the Life and Work of the Mezzotint Engraver William Pether (1739–1821). Print Quarterly XXXVIII: 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Cyril. 1908. Miniatures: Ancient and Modern. Chicago: A. C. McClurg and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Cyril. 1913a. The Art of Miniature Painting. Lecture III. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 61: 839–44. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Cyril. 1913b. The Art of Miniature Painting. Lecture II. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 61: 825–30. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Cyril. 1913c. The Art of Miniature Painting. Lecture I. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 61: 811–17. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Charles William. 1852. The Art of Miniature Painting. London: Winsor and Newton. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, Heath. 1905. Miniatures. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Galerie. 1960. Bedeutende Kunstauktion in Luzern. Mobiliar Aus Schweizer Privatsammlungen Luzerner Zinnsammlung Gemälde Aus Kollektion Hand, R. Und de M. Auktion in Luzern Am 21, 22, 23, 24, 25. und 27. Juni 1960. Luzern: Galerie Fischer. [Google Scholar]

- Foskett, Daphne. 1972. A Dictionary of British Miniature Painters. New York: Praeger Publishers, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Foskett, Daphne. 1979. Collecting Miniatures. London: Antique Collector’s Club. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, John, ed. 2001. Evil Eye. Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Detroit, New York, San Francisco, London: Gale Group, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, Richard W. 1914–1915. The Welbeck Abbey Miniatures. The Walpole Society 4: 1–224. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40086498 (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Graham, Reynolds. 1962. English Portrait Miniatures. London: Adam & Charles Black. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Algernon. 1906. The Royal Academy of Arts. A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from Its Foundation in 1769 to 1904. London: H. Graves and Co., London: George Bell and Sons, vol. VI. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Algernon. 1907. The Society of Artists of Great Britain 1760–1791. The Free Society of Artists 1761–1783. A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from the Foundation of the Societies to 1791. London: George Bell and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Haywood, Emma. 1890. Miniature Painting. The Art Amateur 23: 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Holck, Colding Torben. 1953. Aspects of Miniature Painting: Its Origins and Development. Copenhagen: E. Munksgaard. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, M. A. P. 1872. En Miniature. From the German of Elize Polko. The Aldine 5: 132–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffaers, Neil. 2021. Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800. Available online: http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/PETHER.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Kendrick, Emma Eleonora. 1830. Conversations on the Art of Miniature Painting. London: Privately Printed for the Author. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Basil S. 1929. British Miniaturists. London: Geoffrey Bles. [Google Scholar]

- Mansion, Andre Leon Laure. 1822. Letters Upon the Art of Miniature Painting. London: A. Ackerman. [Google Scholar]

- McClenehan, Helen J. 1930. Miniature Eye Portrait. Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 26: 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- MET. 1996. European Miniatures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Millon. 2016. Collections & Successions—Mobilier & Objets d’Art Prestige. 17 June 2016. Paris: Millon. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, Freeman Marius. 1909. Pether William. Edited by Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee. Dictionary of National Biography. London: The Macmillan Company, vol. XV. [Google Scholar]

- Parsey, Arthur. 1831. The Art of Miniature Painting on Ivory. London: Printed for Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. [Google Scholar]

- Pether, William. 1757. Flower Design. London: Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Pether, William. 1758. Decorative Design in Colour. Manufactures and Commerce Archives. London: Royal Society of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Pether, William. 1770. A Letter of William Pether, G. Russel Street, Bloomsbury, to James Paine, Declining His Election as a Member of the Committee for Conducting the Academy in Maiden Lane, Read at a Meeting of the Directors. July 11. London: Royal Academy Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Pether, William. 1776. Marriage Certificate of William Pether of the Parish of St. James Westminster in the County of Middlesex and Elizabeth Cook of the Parish of Nottingham, Nottinghamshire. March 20. Nottingham: Nottinghamshire Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Pether, William. 1801. Letter from William Pether about Refining Whale Oil. April 2. Bristol: Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Pether, William. 1802. Letter from William Pether about Refining Whale Oil. March 22. Bristol: Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Pether, William. 1804. Specification of William Pether. Apparatus to Promote the Escape of Smoke. 1804, No. 2778. London: G. E. Eyre & W. Spottiswoode. [Google Scholar]

- Pointon, Marcia. 2001. Surrounded with Brilliants: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England. The Art Bulletin 83: 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przesmycki, Zygmunt. 1912. Pamiętnik Wystawy Miniatur oraz Tkanin i Haftów, Urządzonej w Domu Własnym w Warszawie przez Towarzystwo Opieki nad Zabytkami z Przeszłości w Czerwcu i Lipcu 1912 Roku. Warszawa: Towarzystwo Opieki nad Zabytkami. [Google Scholar]

- RISA. 1769. A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Designs in Architecture, Models, Drawings, Prints, etc. Exhibited at the Great Room Spring-Garden, Charing-Cross, 1 May 1769. London: Printed by William Bunce. [Google Scholar]

- RISA. 1770. A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Designs in Architecture, Models, Drawings, Prints, etc. Exhibited at the Great Room Spring-Garden, Charing-Cross, 16 April 1770. London: Printed by William Bunce. [Google Scholar]

- RISA. 1771. A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Designs in Architecture, Models, Drawings, Prints, etc. Exhibited at the Great Room Spring-Garden, Charing-Cross, 26 April 1771. London: Printed by William Bunce. [Google Scholar]

- RISA. 1777. A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Designs in Architecture, Models, Drawings, Prints, etc. Exhibited at the Great Room Spring-Garden, Charing-Cross, 28 April 1777. London: Printed by T. Bensley. [Google Scholar]

- SAGB. 1764. A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Drawings, Prints, etc. Exhibited by the Society of Artists of Great Britain, at the Great Room in Spring-Garden, Charing-Cross, 9 April 1764. London: Printed by William Bunce. [Google Scholar]

- SAGB. 1765. A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Designs in Architecture, Prints, etc. Exhibited by the Society of Artists of Great Britain, Instituted by His Majesty’s Royal Charter, 26 January 1765. London: Printed by William Bunce. [Google Scholar]

- SAGB. 1766. A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Drawings, Prints, etc. Exhibited by the Society of Artists of Great Britain at the Great Room in Spring-Garden, Charing-Cross, 21 April 1766. London: Printed by William Bunce. [Google Scholar]

- SAGB. 1768. A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Drawings, Prints, etc. Exhibited by the Society of Artists of Great Britain at the Great Room in Spring-Garden, 28 April 1768. London: Printed by William Bunce. [Google Scholar]

- Halls Fine Art Auctioneers Shrewsbury. 1996. Miniatures & Works of Art. 13 November 1996. Shrewsbury: Halls Fine Art Auctioneers Shrewsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Sotheby’s. 1978. Fine Art and Miniatures. 26 June 1978. London: Sotheby’s. [Google Scholar]

- Whittock, Nathaniel. 1844. The Miniature Painter’s Manual: Containing Progressive Lessons on the Art of Drawing and Painting Likenesses from Life on Card-Board, Vellum, and Ivory. London: Sherwood. [Google Scholar]

- Wickes, Henry Leonard. 1974. Regiments of Foot. A Historical Record of All the Foot Regiments of the British Army. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, George Charles. 1904. How to Identify Portrait Miniatures. London: G. Bell and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, George Charles. 1921. The Miniature Collector. A Guide for the Amateur Collector of Portrait Miniatures. London: H. Jenkins Limited. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).