Abstract

In Everyday Life in the Modern World, first published in 1968, Henri Lefebvre presents the sexual revolution as the first instance of the cultural revolution. This aspect has remained one of the central themes of contemporary activism, often reflecting the relationship between social and artistic performance, between art and life or even presenting life as art. Hinged on this relationship, we will discuss some Portuguese art works produced between the 1960s and the present: from dictatorship into democracy. These works build a continuing thematic thread related to what has been termed the “intensification of bodies” but also, as we intend to explore in this article, to a necessary “intensification of minds”, concerning eroticism, sexuality and love.

1. Introduction: A Body between Oppression and Revolution

From 1926 until the democratic revolution of 25 April 1974, the “Carnation Revolution”, Portugal lived under a long authoritarian regime. This dictatorship, called Estado Novo (‘New State’) from 1933, promoted “Salazarism”, being led (until 1968) by António de Oliveira Salazar, a former Professor of Law at the University of Coimbra. This political regime also maintained one of the oldest colonial empires in the world and, from 1961 to 1974, became embroiled in the Portuguese colonial war. Such political events had an ideological impact on the way in which the Portuguese were (not) able to experience their relationship with their bodies (and sexuality).

In fact, during the 48 years of this oppressive dictatorship, Portuguese bodies constituted a device to be shaped according to a conservative ideology that established “God, Fatherland and Family” as the country’s moral pillars. For this purpose, the national organization of Mocidade Portuguesa (“Portuguese Youth”) was created, with pre-military and defensive overtones, being particularly active between 1936 and 1966. Mocidade Portuguesa aimed to stimulate and fully develop the physical capacity of young people, form their character and promote devotion to the Fatherland. Especially reserved for young women were preparations for their marital future, domestic and social duties, with lessons in hygiene, childcare and morals (Pimentel 1996, 2011).

This sectarian, disciplining and domesticating ideology of the body, imposed by the Estado Novo, led to a structural performative character of bodily submission: a complete antidote to free experience and full bodily consciousness. This formed “a time and a specific social and mental space” (Gil 2017, p. XXI), where “a minority of Portuguese shaped what the majority of Portuguese did” (Gomes 1991, p. 110). This conservative ideology, modelling mentalities and habits, was also reinforced by a system of political censorship directed at everything that contradicted this idea of disciplining the body, especially artistically. This censorship, documented by various historical, sociological (See, for example, (Godinho 1980; Rosas and de Brito 1996; Rosas 2001; Pimentel 1996, 2011; Simpson 2014)) and artistic studies1, particularly in the areas of cinema and the performing arts, saw its temporality paradoxically extended beyond the Portuguese revolution, in 1974, as we shall demonstrate later in this paper.

There was some opening to discourse on intimacy and private life during the 1960s and 1970s, particularly in the transitional year to democracy in 1973 (Freire 2016). Nonetheless, even in the Estado Novo’s final months, the Censorship Commission officially continued to ban all types of erotic films until 26 April, the day after the revolution. The theme of eroticism, more specifically “bedroom scenes”, followed by “nude body images”, was the most highly censored (Morais 2021)2.

After that date, and even after the end of the Censorship Commission and its replacement by a Shows’ Commission, age restrictions and moral indications were maintained (Cunha 2011). In other words, after 25 April 1974, there was a progressive public debate on issues related to the expressiveness of the body: sexuality and eroticism, affectivity and intimacy. The Portuguese people could now flock to cinemas to see international films that had been banned during Salazarism, especially erotic and even pornographic films. At the same time, however, “several attempts were made by both distributors and anti-pornography activists to apply public and private pressure to influence the taking of a political position” (Cunha and do Carmo Piçarra 2013, p. 57), in a restrictive sense. This was often done in the name of Catholic morality, as in the case of the controversial exhibition of Pasolini’s Salò or the 120 days of Sodom. With such ambiguities between oppression and freedom, the spectator was often seen as an “inexperienced child with no idea of the dangers involved” (Cunha 2011).

These ambiguities, contextualized in a period of transition to democracy, were manifested in several new cycles that re-emerged as a structural conservative habitus, in the Bourdinian sense, affecting or conditioning freedom of expression even after the revolution.

This process does not seem to present the sexual revolution as the motto of a societal transformation, as proposed by Henri Lefebvre in his Everyday Life in the Modern World (1968), where the sociologist advocates reform and sexual revolution as the starting point for a cultural revolution. It rather sees it as a kind of “work in progress”, a revolution that seems to remain a continuous necessity right up to the present. As Lefebvre underlined, the change to be undertaken should not only concern female–male relations, legal and political equality, or the defeudalization of sex-to-sex relations and their democratization. For Lefebvre, the transformation should modify affective and ideological relationships between sexuality and society. He then proposed that repressive society and sexual terrorism should be attacked and overthrown through all means possible, via theory and practice: “Let sexual repression no longer be the subject (and even the essential subject) of institutions. May it disappear”, so that “control is a matter for the interested parties, not for the institutions, much less the moral order and terrorism together” (Lefebvre 1969, p. 275).

2. Dance First, Think Later?

This mandatory denunciation of societal censorship of sexual revolution, as proposed by Henri Lefebvre, has had the artistic domain as one of its main stages in Portugal. This is shown particularly by the question that the Portuguese sociologist, critic and curator, Alexandre Melo, used as a title for an article in the newspaper, Expresso: Será que os portugueses têm corpo? (Do the Portuguese have a body?) (1993). Despite seeming absurd, Melo’s question actually proved to be disturbing, as evidence accumulated that the answer seemed to be ‘no’:

The Portuguese have no body. A current topic of observation—despite the destabilization brought about by private television—is the way in which the majority of discourses approach sexuality and, above all, the issues of sexual differentiation, discrimination and repression.(Melo 1993, p. 52)

Later in the same article, Alexandre Melo also questions why, in Portugal, there was no correct prevention of AIDS and that sexual discrimination continued, without anyone being held responsible or even expressing indignation. And, again, in his words:

The most radical hypothesis is that, perhaps, the Portuguese have no body. The body has no place in the current and dominant discourses in Portuguese society and that is why everything happens as if the Portuguese had no body.(p. 52)

This questioning adds a nuance to Lefebvre’s proposal, inscribing the issue of the body in the relationship between what we can call the social performativity (of the Portuguese) and the artistic performance (Madeira 2020a). Melo’s article analyses the body’s discursive deficit in Portuguese society, to focus on the emerging “intensification of the body” that was becoming visible, especially on the New Portuguese Dance stages in the late 1990s. Choreographers such as Vera Mantero and Francisco Camacho, among others, paved the way for theatrical dance stages to investigate the body socially and historically. This “intensification of the body” in dance, initiated by Alexandre Melo, was continued and extended in other texts. Corpo Atravessado, Corpo Intenso (Transversed Body, Intense Body) was written in 1998 by the anthropologist, André Lepecki. Based on Melo’s text, journalist Raquel Ribeiro (2010) wrote Os portugueses já têm corpo e os criadores encontraram-no (The Portuguese have a body now and the creators have found it) in 2010, for the Público newspaper, which looked back as well as into the future. Uma intensa presença do corpo—A Dança em Portugal no contexto de uma democracia recente (An intense presence of the body—Dance in Portugal in the context of a recent democracy) was produced by anthropologist, Maria José Fazenda, 2014. In the preface to a book of essays, Intensified Bodies from the Performing Arts in Portugal (Vicente 2017), coordinated by Gustavo Vicente, the Portuguese philosopher José Gil questioned how a body can be intensified. In the same year, João Oliveira included an introduction on the same question in the Portuguese translation of Judith Butler’s book, Gender Trouble. Appearing 27 years after its first international edition, this book’s introduction established a transnational perspective presenting the New Portuguese Dance again as a precursor to the performative gender revolution in Portugal. In 2021, the artist Miguel Bonneville created a programmatic performative cycle and published Recuperar o Corpo (Recovering the Body). More recently, on 29 April 2022, when this paper was being revised and the 48th anniversary of the Portuguese revolution celebrated, Alexandre Melo published a new article in the newspaper, Expresso, entitled Do the Portuguese have a body now?, it stands as clear proof of a continuous and cyclical questioning about the new ways of intensifying the body in Portugal.

We will now address these various reflections around the notion of “intensification of the body”, not only as a tool and theme of a particular time and disciplinary artistic field, but as evidence of a bodily (and necessarily sexual) revolution in continuous process.

Considering the transformations in the artistic field, and particularly the emergence of New Portuguese Dance, André Lepecki has argued that “the condition of the Portuguese body over the last two decades can be characterized by an increasing sensorial intensification” (Lepecki 1998, p. 15). Lepecki provides a framework of the historical phenomena that made “the ground under the Portuguese body shake”. Besides the end of the dictatorship, the empire and the Portuguese colonial war, Lepecki adds economic pressure and that of the cultural approximation with Europe, after Portugal joined the European Community in 1986. All these structural transformations led to the emergence of a “Body that is thus thrown into the midst of a crisis of self-recognition and self-reinvention in this post-revolutionary transition” (Lepecki 1998, p. 15). This bodily crisis is questioned through an intensification of the body that, for Lepecki, appears as a dramaturgical tool, and through a hyperbolic mimesis, which has made “manifest and corporeal the tremor that this unstable ground causes in the body” (ibid., p. 15). Lepecki argues that this intensification is one of the most relevant traits in the work of New Portuguese Dance artists:

Whether working with their own, or another person’s body, the body is lucidly perceived as intensely bound to, and constructed, as well as destroyed by, multiple and conflicting discourses transversing Portuguese society today. Discourses of nation, of modernity, of periphery, of “Europe”, of dramaturgical and performative affiliation crash down upon the performing body with a force powerful enough to shred it into nothingness. This shredding force—which is the force of history—is further intensified by the quite explicit political demands of creating a “contemporary” temporality, in step with a reified Europe.(ibid., p. 25)

Raquel Ribeiro’s article, referred to above, dialogues directly with Alexandre Melo’s earlier text. Ribeiro recontextualizes Melo’s questions, stating that at the end of the first decade of the new millennium, the Portuguese body changed, becoming more androgynous and ambiguous. Focusing specifically on the issue of gender identity and on its relationship with the arts, this update presents a more heterodox reality, in which feminine and masculine characteristics mix and dilute. This is the case of works by artists such as Miguel Pereira, André Murraças, André Teodósio, Miguel Loureiro, Miguel Bonneville and Olga Roriz; as well as by Vasco Araújo and João Pedro Vale in the plastic arts. As André Teodósio underlines in his interview for this article: “Basically, the body is always us. It is always our body that is there, but everything is there”, arguing that today “it is already another body that is affirmed. It is the perverse logic of the art of undermining the question by asking a new one. The aim is to continue to create a living organism. In a few years, we will all be a community of multiples”.

Both the 2014 article, by Maria José Fazenda, and the 2017 Portuguese introduction to Butler’s book Gender Trouble, by João Oliveira, presented a retrospective reading, underlining the pioneering role of the New Portuguese Dance choreographers in the creation of an emergent Portuguese corporeal discourse. This showed itself as an inseparable ‘open body’ in terms of the country’s social and political 1990s transitions. In Fazenda’s view, these dancing bodies could not fail to reflect the heritage that, during the Estado Novo, restricted the body, in several of its dimensions, from individuality to sexuality, affectivity and gender, to a profound silence.

Some of these New Portuguese Dance choreographers, Paulo Ribeiro for example, performed gestures in their pieces that referred precisely to the issues of oppression and surveillance over bodies that Salazarist educational policies had reinforced, such as the division between classrooms and playgrounds for girls and boys in schools. Fazenda argues that the pieces by these choreographers are “significant representations of the experience of a particular time” but also “generators of knowledge about that historical period, in which bodies were subject to direct control” (Fazenda 2014, p. 86). At the same time, they are expressions “of the construction of subjectivities and individual identities, in constant negotiation with the cultural, social and political forces in motion within the reality where the choreographers live and that shape their artistic creations” (ibid., p. 86).

In the preface to Intensified Bodies from the Performing Arts in Portugal, José Gil begins his discussion by contextualizing the period of dictatorship as a “frozen space-time” preventing the “emergence of intensive bodies” (Gil 2017, p. XXII) that underwent a complex transformation after the 1974 revolution. Democracy, for Gil, brought two opposing forces: one of “intensification” and the other of “standardization”. The first force created a new community space for free bodily expression; the second, which, in his view, defeated the first force in political terms, did the opposite, leading to the re-territorialization of bodies, creating closure, normalization and disciplinarization. Bodies quickly acquired new forms of isolation, atomization and culture of the ego, recovering, as in the dictatorship period, the tendency to hide traumatic conflicts such as the Portuguese colonial war, which were silent in the public space and the media for more than two decades after the revolution. New Portuguese Dance, emerging in the late 1980s and early 1990s, was thus faced with a need for deconstruction, criticism and even destruction that activated this need to create an intensified body, without having, in Gil’s view, any national artistic reference. José Gil, therefore, argues that the only way to promote body intensification was to experiment with the different techniques, styles and grammars being developed in Europe and the United States, (re)territorializing them in situ in the Portuguese context:

The manner in which the organic movement maintained a global subterranean order allowing for turbulence and local chaos; the way each artist combined, exacerbated or harmonized these two tendencies; were also generators of intensity—and the nature of the post-25th April intensified bodies of Portuguese performing arts. These tensions paved the way for the emergence of new ‘contemporary’ bodies’.(Gil 2017, p. XXV)

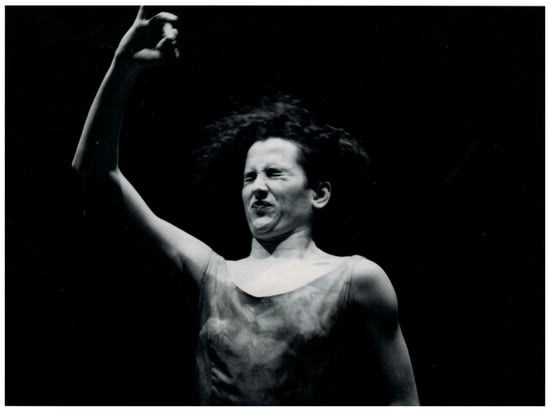

João Oliveira, however, focusing on the specific theme of gender issues, based on Butler, uses the title of a Vera Mantero choreography, Talvez ela pudesse dançar primeiro e pensar depois (Perhaps she could dance first and think afterwards) (Figure 1), to state that in Portugal, dancing came first and thinking later:

I argue that it was in contemporary dance that the first effects of Gender Trouble in Portugal were noticed. A reinvention of dance in our country (…). Artists who took a questioning of bodies seriously that would convey the Portuguese situation. Thinking about a body between worlds, a country always coerced between modernity and tradition, colonizer and colonized.(Oliveira 2017, pp. 13–14)

Figure 1.

Talvez ela pudesse dançar primeiro e pensar depois (Perhaps she could dance first and think afterwards). Vera Mantero. Crédits by José Fabião.

More recently, in 2021, Miguel Bonneville, an artist who has been predominantly dedicated to the theme of gender identity, programmed the performative cycle Recuperar o Corpo (Recovering the Body) at Teatro São Luiz in Lisbon. Several artists from different generations presented performances, choreographies or plays at his invitation. The selection of artists constituted, as the curator expressed it, “a kind of archive” and “a way of not forgetting” the various types of relationship with the body that these artists have developed in Portugal. It was, essentially, a “re-emphasis that there is no art without a body” (Bonneville 2021, p. 92). This cycle simultaneously represented a proof of love and a tribute to the artists who influenced him. It was also the collective memory of a bodily path, already being traced, of “Bodies that speak, erotic bodies, bodies that de-instrumentalize themselves. Bodies that cannot be explained. To recover the body is to recover the enigma” (Bonneville 2021, pp. 9–10). This enigma refers to a body that seeks to reconstruct itself continuously, a subjectivity that seeks to expand in the relationship with the other, assuming, as Erika Fischer-Lichte says, that “People, in their distance from themselves, need (…) a threshold to cross, in order to (re)find themselves as another” (Fischer-Lichte 2019, p. 489). This “intensification of the body”, which has been visibly manifested in the public space since the 1990s, is therefore based on a process of inter-opening (Bachelard [1957] 1989) of the bodies of the Portuguese, where all rhizomatic relations between art and life are triggered by the body as medium.

3. Think First, Dance Later?

A New Portuguese Dance is repeatedly spoken of as the precursor of an intensive body discourse within an ongoing sexual revolution. This does not mean, however, that there is an exclusive place for artistic investigation of the theme, as we aim to demonstrate below. Even if it was seen in dance from the 1990s onwards, intensive body discourse had varied embryonic expressions in Portugal from literature to the plastic arts and, especially, in performance art. We have chosen to highlight some examples, with no attempt to be exhaustive and acknowledging a certain arbitrariness. These examples, however, do attest to the pre-existence of thinking on the body and the sexual revolution that was underway before of the Carnation Revolution in 1974.

The book Sim… Sim! (Yes…Yes!) by Ernesto de Melo Castro (2000), with the subtitle Poemas Eróticos (Erotic Poems), brings a history of previous publications with it. The book is based on another called CARA LH AMAS published by Edições Afrodite in 1975, a title chosen by the author in 1964 for the compilation of erotic poems that he had been working on since then.

CARA LH MAS included, for the first time, an introduction, which made the publication of these poems only possible after the revolution. This same introduction would be published again, albeit as a prologue, in the 2000 edition. It is here that Melo e Castro explains that he wanted a title expressing the eroticism of his poems directly, thus using a type of language considered unacceptable in the dark and repressive pre-revolutionary times. For more than ten years (1984–1975), the book remained unpublished. In 1975, after the revolution, when the opportunity arose, this original title was weighed against other possibilities, such as Os Erros de Eros (The Errors of Eros). Keeping the title CARA LH AMAS would be the direct affirmation, through experimenting with visual poetry, of a set of words that linked together would highlight its erotic and raw but also satirical and humorous character, summarizing the motto of a “Love” that “is face to face”.

Some poems in this book had, however, been published in 1970 in the Antologia de Poesia Erótica e Satírica (Anthology of Erotic and Satirical Poetry) organized by Natália Correia. This led to court charges of abusing the freedom of the press. Melo e Castro’s introductory text, therefore, foregrounds this history of censorship, which preceded the democratic revolution of 1974, but also affirms that, in a democracy, the sexual revolution must be assumed as liberation and as pleasure. The text displays a desire for debate on current issues in the sexual domain, invoking works such as Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty (original title: Présentation de Sacher-Masoch) by Gilles Deleuze or A History of Pornography by H. Montgomery Hyde and discussion contexts alluding to it (the famous report of the United States Presidential Commission on Obscenity and Pornography). It also shows Melo e Castro’s desire to be affiliated with a long erotic-satirical poetic lineage that, in Portugal, has its origin in the medieval songbooks3. Referring the reader to the Antologia de Poesia Erótica e Satírica, he argues that it confirms the erotic-satirical vein existing in Portugal from the medieval age to the avant-garde. In short, this introductory text provides double justification: it explains the book’s censorship during the dictatorship and, at the same time, explores the questions posed about eroticism and pornography in the post-revolutionary period.

In 1980, Melo e Castro would have an important role in the António Arroio School of Arts, in Lisbon, where he was a teacher, by defending students who had decided to graffiti the school walls clandestinely with the expression Amo-te (I Love You). The ‘A’ (the initial letter of the word ‘love’ in Portuguese) was confused with the symbol for anarchism. This meant that students, now in a democracy, could potentially be punished. Melo e Castro was an attentive observer of (we might even say researcher into) the graffiti that was unleashed on Portuguese walls after 25 April 1974. He wrote about it in the Colóquio Letras magazine and participated in an RTP4 television programme in December of that same year, attempting to demonstrate that with the revolution, the “laboratory of experimental poetry jumped onto the street” (Madeira 2019a; Madeira et al. 2021) as a means of popular expression. Melo e Castro made use of these same rhetorical-pedagogical skills to justify the student graffiti, as an important stand for freedom.

Although these manifestations have yet to address the defence of gender performativity, they suggest an attitude towards the liberation of bodies and senses that has found its eminently conceptual expression. Words have served here as a speech act, or to perform in J. L. Austin’s performative sense (Austin 1975). This is the human capacity to act with words, showing that it was necessary to change language in order not to reproduce embodied stories. It was, therefore, necessary to change discussions, arguments and scenes (Irigary 1985). In either case, such a conceptual reaction to the situation clearly invokes the seeking of more elaborate and, at same time, alternative strategies to defend democratic precepts against censorship. Melo e Castro had, in fact, already tried to express himself in the 1950s through an amateur play that he had prepared with students at an industrial school in Lisbon, which was heavily censored by the political police. As a result, he made an artistic detour to areas less exposed to censorship, such as visual poetry and performance (Madeira 2019b) to continue his struggles in search of a revolution.

Another artist who invoked this approach, transforming it through a feminist reading into a new sculptural materiality was the artist Clara Menéres. In 1969, Menéres provocatively built a Relicário (Reliquary) for the exhibition of a phallus, setting a transparent phallic sculpture molded in synthetic resin in a blue lacquered box. The work invoked a new relationship with the idea of reliquary, dominated by Eros, presenting itself as a satirical critique of prevailing Catholic morality in Portugal.

Later, in 1977, Menéres5 produced a work for Alternativa Zero, a collective exhibition organized by Ernesto de Sousa at the Galeria de Belém in Lisbon. Mulher-Terra-Mãe (Women-Earth-Mother) was a large-scale sculpture composed of earth in which grass was planted. This living sculpture, evoking the torso of a lying woman, exposing breasts, belly and vulva, composed of grass that cyclically needed to be trimmed, was shown again at the 1977 São Paulo Biennial. It would also be one of the works presented in 1997, as part of the Serralves Foundation’s Alternativa Zero retrospective exhibition. These diverse installations, in Lisbon and São Paulo in 1977, and in Porto twenty years later in 1997, suffered forms of censorship either by the local population or by its institutional leaders. In 1977, in Lisbon, the piece was seriously vandalized during the night. In São Paulo, the installation was subject to several delays because the mayor did not agree with its inauguration. In 1997, the Serralves Foundation rejected the proposal to permanently install the work as public art in its gardens. These examples of recurrent forms of censorship were clearly linked to the continuous prejudice regarding the exposure and materiality of the body.

4. Performance or the Vice-Versa of Body and Mind

The issues raised by Ernesto de Melo e Castro about pornography and eroticism in the introductions to his 1975 and 2000 books of erotic poems will be discussed again when we come to PORNEX. This was an exhibition of pornographic arts and objects, which took place at the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences’ Students’ Union in 1984. It was the time of the scandal surrounding the film, Pato com Laranja (Duck in Orange Sauce) (1975), with Ugo Tognazzi and Monica Vitti, which had recently aired on Portuguese public television. At the same time, Portugal was in the process of joining the European Community, which would happen in 1986.

With the question “Faculdade ou Bacanal”? (“Faculty or Bacchanal?”) in the air, an exhibition was organized with the aim of doing something new, evocative and also related to what Portugal was experiencing at the time. The innovation came from the fact that pornography, usually for individual consumption, would here be seen openly in public. Holding such an event in an academic institution, despite its critical-satirical character, created “a certain scientific pretext legitimizing the presence of people, camouflage for their desire to see these things that makes them seem perfectly irreproachable in being here” (Correia 1984, p. 68).

Portugal’s entry into the European Community was also discussed, and academics and artists, in some cases academic performers, such as Alberto Pimenta and Rui Zink, organized an art exhibition, as well as performances, films, lectures and activities in terms of the potentially erotic-submissive relationship that Portugal assumed in relation to Europe. As Rui Zink wrote in “Onamismo e Pornografia” (“Onamism and Pornography”) which opens the book PORNEX:

Portugal is today a country that is at the crossroads. If we want to be Europe, if we want to lift our good name and our economy out of the mud, if we want to have luxury tourism and fur-lined boots, then there is no need to hesitate: our future lies in pornography. To the shouts of‘Amsterdam has come and gone Lisbon now rules’Let’s move forward throughout Europe, to conquer our place in the EEC. We promote pornography campaigns. Forward, forward, the seeds are already sown. If pornography is the salvation from bankruptcy for old cinemas, it will be so for our eight-century homeland too. Let us send the twelfth graders and conscientious objectors in civic service throughout this country.(Zink 1984, p. 21)

As mentioned by Leonor Areal, reactions to the event were expressed in several ways, one of which was recorded on the huge white sheet nailed to one of the walls entitled “pornograph yourself”. Criticisms appeared here, such as “It is a pity that this Faculty has fallen so low”, and someone would retort: “Would you like it to go down?”, “These fucking Faculty students, instead of fucking, they hold exhibitions”. Ernesto de Melo e Castro, who went to read poems from his book CARA LH AMAS, was interrupted by an Anthropology student: “Leave words and annoyances, move on to actions! Isn’t that what pornography is? After all, they only talk, I still haven’t seen them fuck!” (Areal 1984, pp. 91–92). Areal goes on to tell us that there were some attempts to censor this kind of collective happening, concealed as “collective fears”, which no one wanted to take as personal. Perhaps for this reason, PORNEX was, for Areal, “a kind of revolution” (Areal 1984, p. 102).

Alberto Pimenta, a professor of literature in that faculty but also a Portuguese performer, devised a public performance at the PORNEX inauguration. He was subject to satirical transvestism by the Brazilian professor, Iracema Pinto de Andrade, who would “replace” him in the talk “Pornography, Art, Human Sciences and Vice Versa”. This vice-versa identified in the title of this talk is presented as an important metaphor for the transit developed between the body (movement) and the mind (conceptual thought) present in performance art, a genre that increased in importance in Portugal during the 1980s (Madeira 2007, 2016). In Portuguese performance art, an expressive “intensification” of the body and mind emerges, which was not referred to as a precursor of the New Portuguese Dance in the 1990s. For the emerging generation of dance performers who had trained in Europe and the United States, it did not present itself as part of a national lineage. Performative intensification practices had no influence on these young artists, because they didn’t know of their existence and, therefore, were not its spectators. For dance performers, in fact, it seemed a hidden and unknown lineage that had only recently been recovered in Portugal (Madeira 2007, 2020a; Metello 2007; Dias 2015; Brandão 2016; Marçal 2018; Fernandes 2018, among others). This lack of knowledge led to the existence of a kind of rupture between two performative movements based on the body, which both “intensified” through different and asynchronous degrees of exposure and inscription in the public space in the 80s (Performance Art) and 90s (New Portuguese Dance). This hidden history of performance art, perhaps due to the lack of critical attention, which translated into a hidden presence for the new generations, led to Portuguese choreographers finding their reference models for the intensification of the body on the international scene, as José Gil points out in his preface to Intensified Bodies. However, despite these two generations of Portuguese artists taking divergent paths, some New Portuguese Dance and theatrical dance creators (Fazenda 2007) advocated a progressive movement towards the art of performance, developing:

a new attitude towards the body and dance, which was seen in their interest in various kinethic activities (everyday gestures, for exemple), the use of a wide range of physical training tecniques (…). They recombined dance and narrative with other elements of the performing arts and the plastic arts in completely new ways (…)(Fazenda 1997, pp. 14–15)

This approximation was made through experimentation that led to a growing ambivalence between the artistic categories. Lepecki sees this happening in the evolution of Vera Mantero’s work, as follows:

Mantero’s solo work has been lately verring more and more to a delicate form of performance art—although without performance art’s attachment to autobiography, and with dance’s trust on the body’s presence and mobility—as one could see in Foda de Morte (Death Fuck) (1996), a reflection on Sade presented in the context of an exhibition of illustrations of Julião Sarmento for Sade’s Justine, or in uma misteriosa Coisa dissse e.e. cummings, (a mysterious Thing said e.e. cummings).(Lepecki 1997, p. 50)

For Mariana Brandão (2016) too, both Mantero and João Fiadeiro, who started clearly in dance, built a path that took them to the production of performance. Without ever striving to frame their pieces (in terms of institutional dissemination), their work benefited from the ambiguous use of the terms “dance” and “performance”.

The movement and thought of “intensification” began, however, before the emergence of the New Portuguese Dance. In fact, some time before PORNEX began, the artist Elisabete Mileu, who was taught by the sculptor Clara Menéres at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon, introduced the exhibition of her naked body in performance on the Portuguese stage (Madeira 2020b). She then toured the main Portuguese and European performance festivals between 1981 and 1992. More than feminist issues, this nude invoked and underlined the “intensification of the body” discourse. Egídio Álvaro, one of the most prominent performance art critics, organizers and gallery owners in Portugal and France, highlighted her work in the Performance Portugaise catalogue at the Center Georges Pompidou in April 1984 in Paris, stating that:

Elisabete Mileu is an extraordinary creator of tense spaces where sobriety meets detachment. As soon as her naked body (…) penetrates her installations, the energy flows freely, crossed by lightning flashes of a desperate look, by hoarse screams, by spasmodic movements.(s.p.)

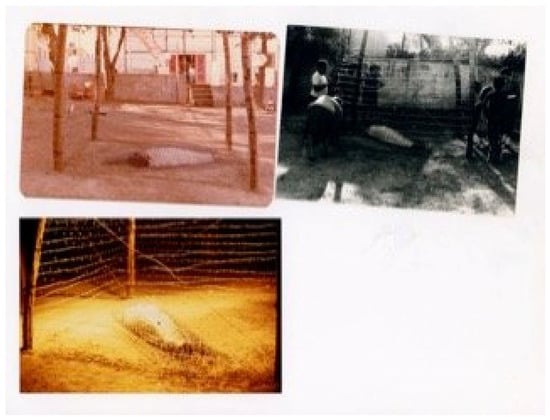

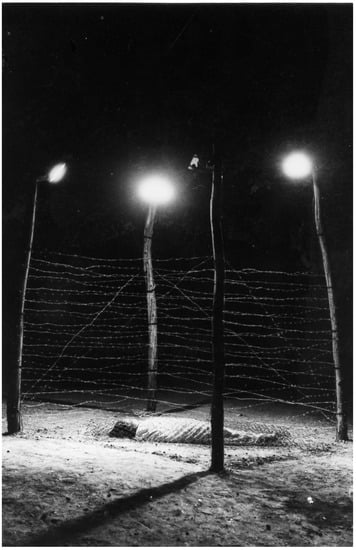

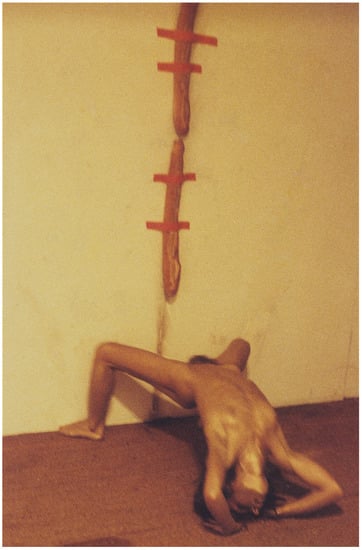

Álvaro was referring precisely to Mileu’s “brutal staging of the body”, which highlighted the role of the taboos linked to it in contemporary Portuguese society, stating that the progressive transformation of morals in Portugal did not, or rarely touched, these taboos. Mileu’s body thus presented itself to this critic and commissioner as “the fragile detonator of the waiting violence” (s.p.) against a dominantly machismo and at the same time matriarchal society. As Álvaro also explains, the presence of women was very rare in Portuguese performance art because the body did not play any fundamental role in this society. Elisabete Mileu is an exception that revolutionized this aspect in Portugal, while having many peers in the transnational context. Indeed, Mileu toured the main national and international festivals and performance meetings in the 80s, sharing the space and imagination of other female performers, such as Orlan, Shirley Cameron, Barbara Heinisch, Laurence Hardy, Gaël, Elisabeth Morcellet, Manuela Fortuna, Ilse Wegman-Hacker, Monique Hebré, Natascha Fiala, Suzanne Krist, Catherine Meziat, Chantal Guyot, Orlan, Natasha Fiala, Marie Kawazu, Marcelle Van Bemmel, Tara Babel, Lydia Schouten and Ção Pestana. The euphoric/dysphoric body, the commodity body, the object body, the animal body, the domesticated body all intersect in this shared creativity of female performers, as shown by Egídio Álvaro’s archive. This was recently made available to the public by the curator Paula Parente Pinto, in the program Recalling the Future: Performing the Archive at the RAMPA space, in Porto, from 11 to 21 May 2022. What does Elisabete Mileu’s body talk about? She shows us the passage of a woman without a visible body, a woman conditioned by her social context, to a woman intensive body; a woman expelling an explosive magma through her body, chaotic in its indomitable tensions, detached from societal shackles. Mileu’s body becomes a territory for crossing all possible tensions between various types of subjectivity and social context. It presents itself, at the same time, as a “body in the territory” and the reverse of the “territory in the body”; a “territory that presents itself as the center” and the reverse of the “body as the margin” (Barbosa 1983). It is, therefore, in a liminal performance that her body becomes a receptive screen for all kinds of silences, of the unsaid, of ghosts, but also of drives, expectations, desires and dreams. It thus presents itself, as in the twelve-hour performance at the Festival de Arte Viva, Alternativa 1, in Almada, in 1981 (Figure 2 and Figure 3), as a woman’s body immobilized, mummified, made invisible under the raw cloth and net that envelops it. Lying on rough gravel, it is surrounded by high barbed wire fences, in a public space and overexposed to the intensity of the sun and the light sources that turn on at dusk. In later performances (Figure 4), the body presents itself naked, in contrast to this tortuous and supervised enclosure; in a ritual of power and energy, where all metamorphoses are possible. If, in the first case, the woman is confronted with the limits imposed on her; in other performances, she presented herself as pure, wild animal anima. In a reenactment of Almada’s performance, at the RAMPA gallery space, in Porto, on 14 May 2022, choreographed by Vânia Rovisco, she claimed to have felt an “intensification of thought” in that immobilized body. A process that in other performances metamorphosed into an extraordinary “intensification of the body”, with frantic gestures and guttural sounds. This “performance elastic”, in the words of curator Paula Pinto when presenting Mileu’s work, calls into question a legacy of disciplining and domesticating the body.

Figure 2.

Untitled Performance by Elisabete Mileu. Festival de Arte Viva, Alternativa 1, Almada 1981. Photo uncredited. Egídio Álvaro Archive. Archive curator, Paula Parente Pinto, who has kindly granted us permission to use this image.

Figure 3.

Untitled Performance by Elisabete Mileu. Festival de Arte Viva, Alternativa 1, Almada 1981. Photo Manoel Barbosa. Egídio Álvaro Archive. Archive curator, Paula Parente Pinto, who has kindly granted us permission to use this image.

Figure 4.

Untitled performance by Elisabete Mileu, Festival de Paris, 1982. Photo uncredited. Egídio Álvaro Archive. Archive curator, Paula Parente Pinto, who has kindly granted us permission to use this image.

In 1987, artistic performance around these themes reached its peak with the visit of the Italian Member of Parliament (M. P.) Ilona Staller to the Assembly of the Portuguese Republic. Staller, whose stage name was “Ciciolina”, who wore a long white ruffled dress with a low neckline, bared her breasts fully in parliament, provoking indignation on the political benches further to the right, who requested the suspension of the “public spectacle” that offended parliamentary dignity. The event was reported in several newspapers and television news broadcasts. The Italian politician–performer had come to present an erotic show at the Lisbon Coliseu and used the unexpected visit to parliament as a publicity stunt for her show. This visit, only welcomed by the M. P. Natália Correia, who had edited the Antologia Satírica Erótica in the 1970s, took on shockingly humorous contours, without really serving a gender or even a feminist debate. It was, in fact, a clear example of the normalizing reaction that Portuguese democracy, as José Gil’s abovementioned analysis stated, had assumed politically. O medo de existir (The fear of existing), the subtitle of an important book by Gil on contemporary Portugal, became ingrained in the bodies and minds of the Portuguese, as a fear of affirming freedom and the knowledge of shocking and traumatic events (such as the violent and violating body of the colonial war and Portuguese colonialism in Africa) (Gil 2004).

The performative approach, more centered on the theoretical themes of gender studies, along the line set out by Judith Butler but also by Donna Haraway or Paul Preciado, among others, began with the work of the performers, Ana Borralho and João Galante. Creating a path between the New Portuguese Dance and the visual arts, they began to explore themes of transgender identity and eroticism, such as MisterMissMissMister (2002) and Sexy MF (2006), through an expanded notion of performance. Here, a whole movement of experimentation with the fictionalization of the genre opened up, allowing new ways of eroticizing the body. This process is often created in workshops organized by the duo both for other artists and non-artists, who are then confronted with exposure to voyeurs in the presentation space of artistic galleries. This approach led to fanciful, eroticized and sensual transgender experimentation, with a mixture of female and male gender characteristics that were exposed to each other and also to the general public, producing another moment of ongoing sexual revolution. A space for questioning “reiterative behaviours” was thus created, discussed by Richard Schechner (2003, p. 28) and Judith Butler around gender performativity, but also for potential discussion and redefinition of body identities (Madeira 2007). The body and sexuality, already associated with an idea of “gender as prosthetic” (Preciado 2019), began to present itself not as a taboo, a kind of classic play with a pre-set script, played continuously, but rather as a continuous (and diverse) performance. It was in permanent reinvention through a process where “the art of life” was assumed, trying to touch “the impossible”, in the words of Zygmunt Bauman (2017, p. 34). It also assumed, and as sociologist Anthony Elliot mentioned in his book, Reinvention, that “Ours is the era of reinvention (…). The self is recast as a do-it-yourself assembly kit. Reality becomes magically deflated, as there are no longer any constraints imposed by society, at the same time that self is inflated to the level of a work of art” (Elliot 2013, p. 6).

From dictatorship to contemporaneity, a long journey has been made between Portuguese artistic performance and social performativity with regard to issues of the body and sexuality, gender and the disidentifications of identity (Munõz 1999). The “tyranny of intimacy”, referred to by Richard Senett in The Fall of Public Man (Sennett 1977), revealed itself in Portugal through a strange and progressive erosion of the public space seeking to control the intimate sphere of the Portuguese. This led, through the highly diminished active participation of the common citizen in public life, to a reduced number of those who remained with an active voice, such as the politician or the artist, turning the rest into a silenced crowd, mere “crushed spectators” in Sennett’s expression. Thus, despite the fact that, as Benoit Heiburnn also mentions, in La Performance, une nouvelle ideéologie? (Heiburnn 2004), performance, assumed in its social dimension, has been increasingly operationalized as a measurement value (of hierarchy) and visibility. It is a kind of engine governing all aspects of social relations, crossing all areas from its most public expression, of work and leisure, to its most private and intimate expression of “performance in personal relationships” and even of “sexual performance”. Paradoxically, in this scenario, artistic performance remains also a kind of laboratory, where the questioning of the body is experienced and made visible, which can only be assumed as fiction (Le Breton 1992).

In 2020, the visual artist duo of João Pedro Vale and Nuno Alexandre Pereira devised a performance meta-installation, which we have come to define as a work of meta-hybridism (Madeira 2021) entitled Ama como a estrada começa (Love how the road begins) (2020). The piece engages historically with the life and work of Mário Cesariny, author of the poem and of performative interventions with the same title, who was arrested on charges of indecent exposure and homosexuality in Paris in 1964.

The duo began their research during an artistic residency in Paris, where they sought to address the issue of Portuguese emigration in that city. The Portuguese poet, Mário Cesariny de Vasconcelos, emerged as one of these cases, with the specificity of being an artist, homosexual and having been punished for indecent exposure in Paris. The knowledge of the singularity of this episode led them to the creation of this meta-discursive piece, where they tried to mix this story with its interpretation and even performance incorporation. In an interview presented in the catalogue of this work, João Pedro Vale has said that the poem reflects:

the idea of a road, a path, something unsettled that hints at the fragility of the things we take for granted and believe to be permanent. It also echoes the idea of a new beginning, not because anything has come to an end, but because there is a need for renewal, for constant motion. From the political perspective, when we speak about freedom and divergent sexuality, I’m struck by the thought that we can never take anything for granted.(Vale and Ferreira 2020, p. 60)

This idea of non-sedimentation invokes, once again, the necessary continued sexual revolution. This meta-performative installation, where the imaginations of contemporary creators are reflected within the poetic and private imagination of Mário Cesariny, is based on an iron building, inspired by the kiosk observed by the two artists next to the famous Torre St. Jacques, which had fascinated the poet during his stay in Paris. In this fictionalized space, a heterotopia is created where different architectural structures connoted with the gay imagination are symbolically evoked: bathrooms, saunas and public baths, sex clubs and prison cells. This structure is, therefore, conceptually designed to “be inhabited by a body” (Vale and Ferreira 2020, p. 41). A performative body allegorical of all possible uses of space (Figure 5):

That is why it was so important to hold performances in the space. As if the work already had, right from the start, from its earliest design, the scent of bodies. You had to go in and feel that it was inhabited. I think that’s what happened. Even when there weren’t any performances, there was dirty clothing, ashtrays with cigarette butts, the smell of stale beer, objects that looked like they’d been abandoned, and the evocation of Cesariny through the constant repetition of poems from A Cidade Queimada (The Burnt City) scrawled across the walls. There was always a presence, a performative act. Even when the piece wasn’t active, our presence and that of the people we invited to create all this still hung in the air. Whether it was the performance of cruising, the performance of constructing some object or the performance of people visiting the piece.(Vale and Ferreira 2020, pp. 75–76)

Figure 5.

Performance in Ama como a Estrada Começa (Love how the road begins). João Pedro Vale + Nuno Alexandre Ferreira, MAAT, Lisbon, 2020. Photo Bruno Simão.

The catalogue book, in which the interview of the creators is published, was conceived by them from a performative perspective. It was originally produced with uncut pages that had to be separated by its readers to access all its information. They could decide to cut the pages and reveal new content or keep the mystery hidden.

Both the installation and the reading of the book propose a wandering through the visible and the invisible. We move through the interdicts of the body and sexuality, mixing textualities, times and spaces, as in an oblique mirror in which the spectator-reader reflects as an integral part of the work, thinking and also performing their own body.

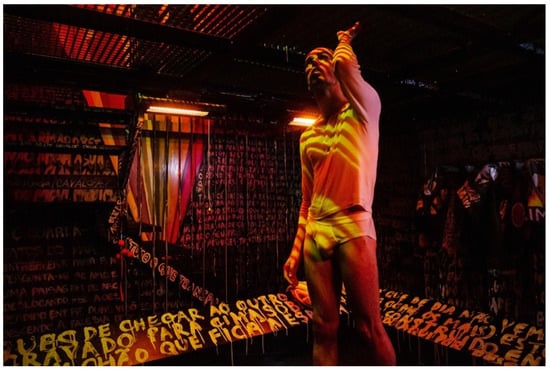

In his recent inquiry, in Expresso, about the place of intensification of the body in Portugal today, Alexandre Melo refers to a new artistic work by this duo of artists: “when asking if the Portuguese have a body now, one would say that the answer cannot be a simple statement but, rather, a strong affirmation, as shown by the exhibition-performance ‘1983’” (Melo 2022, p. 55). 1983 (Figure 6) openly presented itself as a meta-performative artistic device on the social history of the Portuguese. The work, in which several artists had performance moments, was presented at the Rialto6 space (02/11 to 04/29, 2022), in Lisbon, by João Pedro Vale and Nuno Alexandre Ferreira. It summoned up the questions that Alexandre Melo himself raised in his inaugural text in 1993 on the invisibility of discourses on the body and AIDS in Portugal. It also highlighted the history of the marginalization of the body, especially homosexuality in Portugal, which only ceased to be criminalized in 1983. This strong affirmation that the Portuguese now have a body, in Melo’s words, constitutes a radical range of approaches to the themes of the body developed by a group of Portuguese artists, from various disciplinary areas, already born in democracy.

Figure 6.

Performance in 1983. João Pedro Vale + Nuno Alexandre Ferreira, Rialto6, Lisbon, 2022. Photo Bruno Simão.

5. Conclusions: A Continuing Sexual Revolution for an Open Body and Mind

If Ama como a estrada começa and 1983 by João Pedro Vale and Nuno Alexandre makes explicit and visible the meta-performative dimension necessary to think about an open body and mind between Portuguese social performativity and artistic performance, we can say that all the artistic examples mentioned in this article dialogue with this meta-discursive and meta-hybrid dimension. They function as the oblique mirror revealing various notions of the body from diverse temporalities and spatialities, in a dynamic situated between reality, fiction and speculation. A body oppressed by social and political conditioning, whether they are the result of an incorporated dictatorial heritage or of a phantasmatic repertoire that is reactivated in continuous new censorial forms, such as a habitus and a structural ethos. This mixes with a body “to intensify” what reflects both a movement, triggered by the performance and by the New Portuguese Dance, and a thought, emerging in embryo in several artistic projects beyond dance: a dialogue and feedback promoting a continuous update. Body and mind, and vice versa, affect each other, intensifying, as in a story of (un)love. The issues of sexuality are dealt with in these various artistic projects regarding their relationship with a reactivity to everyday life, to the Portuguese context, inscribing in the bodies-minds the possibility of new habits and gestures. The continued inscription of these themes in the artistic field reveals that this revolution is not done once and for all and, therefore, it cannot happen equally for all Portuguese bodies, or even perhaps for all Portuguese artists. As Haraway says, “staying with the trouble is both more serious and more lively. Staying with the trouble requires making oddkin; that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations” (Haraway 2016, p. 4). In summary, the sexual and body revolution, therefore, must continue every day and with everyone’s participation.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia grant number UIDB/05021/2020 and the APC was funded by Arts Journal.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See, for example, the censorship of the Cabrera (2008, 2013)’s theatre and the censorship of the Cunha (2010, 2011)’s cinema, and also (Morais 2017, 2021). |

| 2 | Ana Bela Morais, in an article on the documentary produced by filmmaker Manuel Mozos, entitled Censura: Alguns Cortes (Censorship: Some Cuts) (1999), mentions that the Censorship Commission’s cuts were especially frequent around stripping, sexual scenes, or eroticism (Morais 2013). The filmmaker himself later mentioned in an interview with the newspaper Diário de Notícias that in Portugal: “In the post-World War II period, ladies in bikinis, showing their legs, or with a more daring cleavage, were often cut. Or smoking”, adding that “If they were women who were highly emancipated or who had an ascendancy over men, they were also cut” (Caetano 2019). In this interview, the filmmaker also mentioned that after the beginning of the independence movements, censorship focused more on issues of war, liberation movements and racism, with scenes cut because the characters used the words “revolution” or “democracy”. |

| 3 | Melo e Castro gave me the same justification in the interview held on 19 July 2016, in Lisbon. |

| 4 | Acronym for the State Radio and Television in Portugal. |

| 5 | On 5 April 2017, I had a long interview with Clara Menéres in preparation for our conversation on “Performance Art and Memory”. https://performativa.pt/Conversation-Performance-Art-and-Memory, accessed on 25 February 2022. |

References

- Areal, Leonor. 1984. Memorial do Convento. In PORNEX o livro. Edited by Rui Zink and Leonor Areal. Lisbon: & Etc e tal, pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, John L. 1975. How to Do Things with Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, Gaston. 1989. A Poética do Espaço. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. First published 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, Manoel. 1983. Le territoire-comme-centre; le corps-comme-marge. In Catálogo Elisabete Mileu. Performances 1981–1982. Lisbon: FCG. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2017. A Arte da Vida. Lisbon: Relógio D’Água. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneville, Miguel. 2021. Recuperar o Corpo, Author Edition. Lisbon.

- Brandão, Mariana. 2016. Passos em volta: Dança versus performance: Um cenário concetual a artístico para o contexto português. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Ana. 2008. A censura ao teatro no período marcelista. Media & Jornalismo 12: 27–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Ana, ed. 2013. Censura nunca mais! A censura ao Teatro e ao Cinema no Estado Novo. Lisbon: Alêtheia. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano, Maria João. 2019. O que a Censura cortou: Da perna à mostra à palavra revolução. Diário de Notícias. Available online: https://www.dn.pt/1864/o-que-a-censura-cortou-da-perna-a-mostra-a-palavra-revolucao-10579239.html (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Correia, Clara Pinto. 1984. Faculdade ou Bacanal. In Pornex o livro. Edited by Rui Zink and Leonor Areal. Lisbon: & Etc e tal, pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, Paulo. 2010. A censura e o novo Cinema Português. In Outros Combates pela História. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, pp. 537–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, Paulo. 2011. Uma Censura depois da extinção da Censura: O caso dos filmes eróticos e pornográficos (1974–1976). Paper presented in Avanca Cinema 2011. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/5723807/Uma_Censura_depois_da_extinção_da_Censura_o_caso_dos_filmes_eróticos_e_pornográficos_1974_76_2011_ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Cunha, Paulo, and Maria do Carmo Piçarra. 2013. Censura Nunca Mais? Estudos de Caso durante o Prec. In Media & Jornalismo. Repressão vs Expressão: Censura às artes e aos periódicos. Edited by Ana Cabrera. Lisbon: ICNOVA, vol. 12, pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- de Melo Castro, E. M. 2000. Sim… Sim! Poemas Eróticos. Lisbon: Veja. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, Sandra. 2015. O Corpo como Texto: Poesia, Performance e Experimentalismo nos Anos 80 em Portugal. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, Anthony. 2013. Reinvention. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fazenda, Maria José. 1997. Movimentos Presentes Aspectos da Dança Independente em Portugal. [Present Movements Aspects of Independent Dance in Portugal]. Lisbon: Colibri. [Google Scholar]

- Fazenda, Maria José. 2007. Dança Teatral. Ideias, Experiências, Acções. Lisbon: Celta. [Google Scholar]

- Fazenda, Maria José. 2014. Uma intensa presença do corpo—A Dança em Portugal no contexto de uma democracia recente. Sinais de Cena 22: 84–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, João. 2018. Performance Arte: Projectos, Mediações e seus Desenvolvimentos no Plano Global da Ecranização. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Lichte, Erika. 2019. Estética Do Performativo. Lisbon: Orfeu Negro. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Ana. 2016. A intimidade afetiva e sexual na imprensa em Portugal (1968–1978). Ph.D. thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, José. 2004. Portugal, Hoje: O Medo de Existir. Lisbon: Relógio D’Água. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, José. 2017. Preface. In Intensified Bodies—From the Performing Arts in Portugal. Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Brussels, Frankfurt am Main, New York and Vienna: Peter Lang, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Godinho, José Magalhães. 1980. Quando falar e escrever era perigoso: (antes do 25 de Abril). Mem Martins: Europa América. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, Rui. 1991. Poder e Saber sobre o Corpo—A Educação Física no Estado Novo. Boletim SPEF 2–3: 109–36. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heiburnn, Benoit. 2004. La Performance, une nouvelle ideéologie? Paris: La Découverte. [Google Scholar]

- Irigary, Luce. 1985. This sex which is not one. In Contagious Conversations, The Practice of Dramaturgy Working on Actions in Performance. Edited by Konstantina Georgelou, Efrosini Proptopapa and Danae Theodoridou. Amsterdam: Valiz, p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- Le Breton, David. 1992. La Sociologie du Corps. Paris: P.U.F. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1969. A Vida Quotidiana no Mundo Moderno. Lisbon: Ulisseia. [Google Scholar]

- Lepecki, André. 1997. Nas margens do presente. A dança dialogante de Vera Mantero e de Francisco Camacho. [Margins of the Present. A dialogical exploration of the work of Vera Mantero and Francisco Camacho]. In Movimentos Presentes Aspectos da Dança Independente em Portugal. [Present Movements Aspects of Independent Dance in Portugal]. Edited by Maria José Fazenda. Lisbon: Colibri, pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lepecki, André. 1998. Corpo Atravessado, Corpo Intenso. In Revista Theaterschrift—Intensificação: Performance contemporânea portuguesa. Lisbon: Danças na Cidade, pp. 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, Cláudia. 2007. O Hibridismo nas artes performativas em Portugal. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, Cláudia. 2016. Transgenealogies of Portuguese Performance Art. Performance Research 21: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, Cláudia. 2019a. E. M. de Melo e Castro: ‘O laboratório artístico saltou para a rua em 1974!’. CAP Journal VI: 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, C. 2019b. Teatro de um Homem (L)ido: Metaficção Crítica e Teatral 1954–2005. Revista Comunicação e Linguagens 50: 192–99. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, Cláudia. 2020a. Arte da Performance made in Portugal. Uma Aproximação à(s) sua(s) história(s). Lisbon: ICNOVA. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, Cláudia. 2020b. Elisabete Mileu: ‘Exposição’ e Performance do Corpo Nu. Sinais de Cena 11: 200–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, Cláudia. 2021. Meta-hibridismo e a reativação dos arquivos da arte da performance portuguesa. In Imagens & Arquivos. Fotografias e Filmes. Edited by Teresa Mendes Flores, Sílvio Marcus de Souza Correa and Soraya Vasconcelos. Lisbon: ICNOVA, pp. 300–20. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, Cláudia, Cristina Pratas Cruzeiro, and Ricardo Campos. 2021. ‘25th April always, fascism never again’. The post-Revolution murals in Portugal. In Political Graffiti in Critical Times: The Aesthetics of Street Politics. Edited by Ricardo Campos and Andrea Pavone. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 317–46. [Google Scholar]

- Marçal, Hélia. 2018. From Intangibility to Materiality and Back Again: Preserving Portuguese performance Artworks from the 1970s. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, Alexandre. 1993. Será que os portugueses têm corpo? Revista Jornal Expresso 1073: 52. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, Alexandre. 2022. Os portugueses já têm corpo. Revista Jornal Expresso 2583: 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Metello, Verónica. 2007. Focos de Intensidade/Linhas de Abertura—A Activação do Mecanismo Performance: 1961–1979. Master’s thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, Ana Bela. 2013. O que quase se perdeu—Reflexões sobre censura: Alguns Cortes, de Manuel Mozo. In Revista Media & Jornalismo, Repressão vs. Expressão: Censura às artes e aos periódicos. Edited by Ana Cabrera. Lisbon: ICNOVA, vol. 12, pp. 191–98. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, Ana Bela. 2017. Censura ao Erotismo e violência. Cinema no Portugal Marcelista (1968–1974). Vila Nova de Famalicão: Edições Humús. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, Ana Bela. 2021. Nas vésperas da Revolução de Abril e logo após. Censura ao cinema em Portugal. BEROAMERICANA. América Latina-España-Portugal 21: 135–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munõz, José Esteban. 1999. Dissidentifications—Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, João. 2017. Preface to Problemas de Género de Judith Butler. Lisbon: Orfeu Negro. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, Irene Flunser. 1996. Contributos para a história das mulheres no Estado Novo: As organizações femininas do Estado Novo: A “Obra das Mães pela Educação Nacional” e a “Mocidade Portuguesa Feminina”: 1936–1966. Master’s dissertation, The New University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, Irene Flunser. 2011. A cada um o seu lugar, a Política Feminina no Estado Novo. Lisbon: Editoras Temas e Debates and Círculo de Leitores. [Google Scholar]

- Preciado, Paul. 2019. Manifesto Contra-Sexual. Lisbon: Orfeu Negro. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, Raquel. 2010. Os portugueses já têm corpo e os criadores encontraram-no. Jornal Público. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2010/03/17/culturaipsilon/noticia/os-portugueses-ja-tem-corpo-e-os-criadores-encontraram-no-252773 (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Rosas, Fernando. 2001. O salazarismo e o homem novo: Ensaio sobre o Estado Novo e a questão do totalitarismo. Análise Social XXXV: 1031–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas, Fernando, and José Maria Brandão de Brito. 1996. Dicionário de História do Estado Novo. Lisbon: Círculo de Leitores. [Google Scholar]

- Schechner, Richard. 2003. Performance Studies. An Introduction. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, Richard. 1977. The Fall of Public Man. London and New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Duncan. 2014. A Igreja Católica e o Estado Novo. Lisbon: Edições 70. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, João Pedro, and Nuno Alexandre Ferreira. 2020. Ama como a estrada começa. Lisbon: MAAT. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, Gustavo, ed. 2017. Intensified Bodies—From the Performing Arts in Portugal. Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Brussels, Frankfurt am Main, New York and Vienna: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Zink, Rui. 1984. Onanismo e Pornografia. In PORNEX o livro. Edited by Rui Zink and Leonor Areal. Lisbon: & Etc e tal, pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).