Abstract

The article focuses on the aerodynamic experiments of Petr Vasil’evich Miturich (1887–1956), in particular his so-called letun, a project comparable to Vladimir Tatlin’s Letatlin, but less familiar. Miturich became interested in flight during the First World War, elaborating his first flying apparatus in 1918 before constructing a prototype and undertaking a test flight on 27 December 1921—which might be described as an example of Russian Aero-Constructivism (by analogy with Italian Aeropittura). Miturich’s basic deduction was that modern man must travel not by horse and cart, but with the aid of a new, ecological apparatus—the undulator—a mechanism which, thanks to its undulatory movements, would move like a fish or snake. The article delineates the general context of Miturich’s experiments, for example, his acquaintance with the ideas of Tatlin and Velemir Khlebnikov (in 1924 Miturich married the artist, Vera Khlebnikova, Velemir’s sister) as well as the inventions of Igor’ Sikorsky, Fridrikh Tsander, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and other scientists who contributed to the “First Universal Exhibition of Projects and Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses, Devices and Historical Materials” held in Moscow in 1927.

Keywords:

Petr Miturich; Velemir Khlebnikov; Vera Khlebnikova; Georgii Krutikov; Nikolai Punin; Igor’ Sikorsky; Vladimir Tatlin; Fridrikh Tsander; Konstantin Tsiolkovsky; aeronautics; letun; Letatlin; volnovik; “First Universal Exhibition of Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses and Mechanisms Gadgets and Historical Materials” (Moscow 1927) One of the salient themes of Russian Modernism is flight, metaphorical and practical, examples of which are legion—from the flying demons of Mikhail Vrubel to Aleksandr Blok’s poem “Aviator”, from the crashing airplane in the Cubo-Futurist opera Victory over the Sun to Kazimir Malevich’s Aero-Suprematism. The numerous visual and literary manifestations of the subject would take us into a dense and long orbit of angels, airplanes, balloons, spaceships, levitation, and the firmament, but this essay focuses on a single artist, Petr Vasil’evich Miturich (1887–1956), and a single event which seems to have influenced or, at least, paralleled, one of the most visionary inventions of the later avant-garde, i.e., his flying apparatus or letun (literally, one who possesses the capacity to fly) which he first envisaged in 1918. If Vladimir Tatlin’s Letatlin has been discussed widely, Miturich’s letun has not and, therefore, deserves serious investigation, the more so since it leads us into the wider context of Velemir Khlebnikov’s own flights of imagination. After all, from 1924 onwards Miturich was the husband of the artist Vera Khlebnikova, sister of Velemir, who exerted a profound influence on the artist’s worldview (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vera Khlebnikova: Portrait of Petr Miturich, 1924, Pencil on paper, 25 × 35, Private collection.

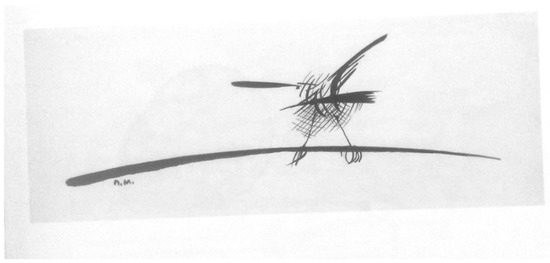

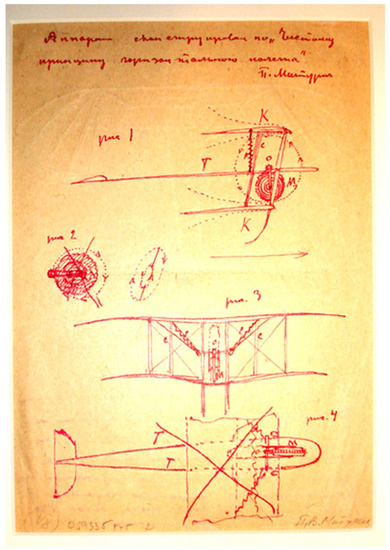

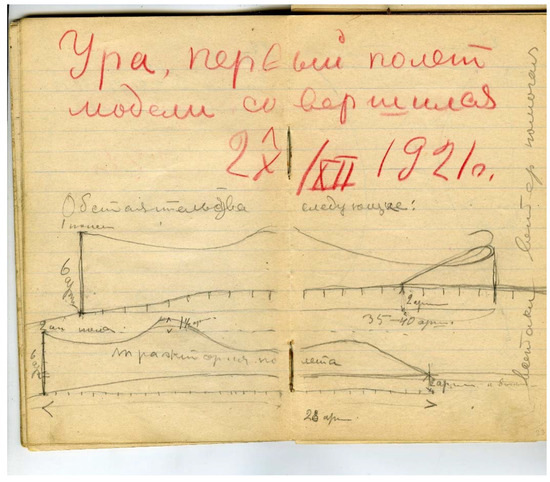

Miturich seems to have first cultivated an interest in flight during the Great War when he studied and introduced hot air balloons as part of the defense system of the Osovets Fortress on the Eastern Front. Inspired, of course, by Khlebnikov’s designs for “flying abodes—cells” and astute observations of birds, Miturich designed his first apparatus in 1918—captured in the drawing called Bird on Branch (Figure 2), which, as Nina Belokhvostova argues, seems closer to an incoming flying object or to the ornitoper (mechanical bird) on which Miturich worked in 1918–1922 (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). In turn, Miturich tested a model prototype on 27 December 1921, in Santalovo1 and, like Tatlin, seems to have elaborated the idea of his flying machine with particular enthusiasm in the mid-1920s—which begs the question: Why? By way of an answer, let us recapitulate the essential details of the letun which might be allied with what might be called a Russian Aero-Constructivism (by analogy with the Italian Aerofuturismo or Aeropittura) (Figure 7).

Figure 2.

P. Miturich: Vignette (Bird on Branch), 1918–1922, Indian ink on paper, 9.4 × 26, State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow, Inv. No.: RS-4330 (p. 44822/4).

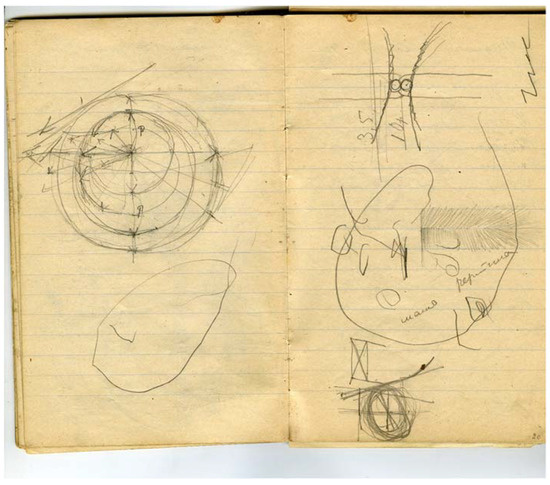

Figure 3.

P. Miturich: Designs for a flying apparatus, 1918, Graphite pencil on paper, 17.5 × 22.1, State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow, Inv. No.: RS-13518 (p. 69603).

Figure 4.

P. Miturich: “I have constructed my apparatus according to the ‘Pure principle of horizontal flight’”, ca. 1921, Red Indian ink on paper, 40 × 27, Private collection.

Figure 5.

P. Miturich: “Hurrah! First flight completed, 28 ХII 1921”, 1921, Pencil on paper, Private collection.

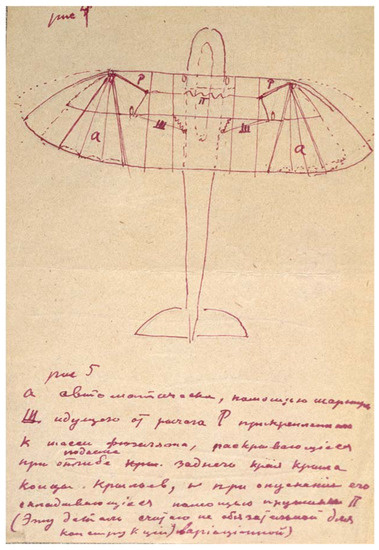

Figure 6.

P. Miturich: Drawings for a flying apparatus. Notebook, 1921, Pencil on paper, Private collection.

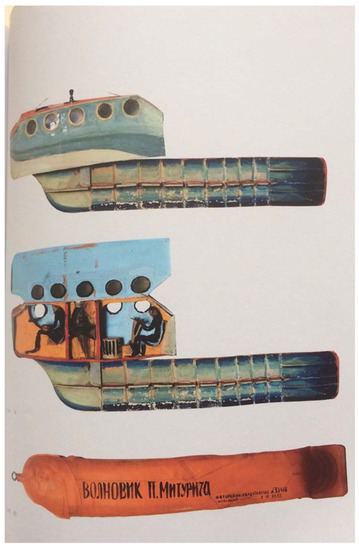

Figure 7.

P. Miturich: Volnovik, ca. 1930, 60 cm long, mechanism wrapped in oilcloth, Private collection.

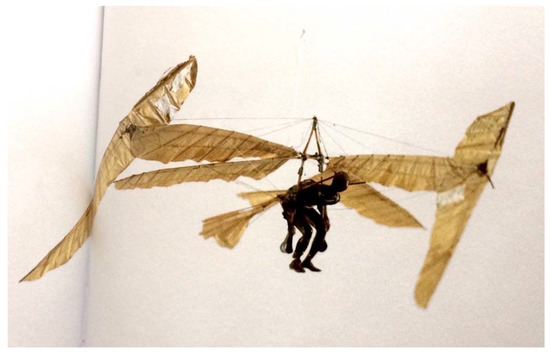

Miturich’s basic argument was that man should no longer be moving around with carts and horses, but with a new ecological apparatus—the volnovik [undulator]—a mechanism which, like a fish or snake, would advance by undulatory action (Ibid.). Miturich contended that the motor impulse of all animals, fish, and birds relied on a spiralic thrust and that each resultant wave continued to reverberate—and to generate further energy—like an echo. Through the judicious application of placement and displacement, traction and distraction, the volnovik would move in air and water and on earth and, in accordance with the respective application, would be called variously an airship, boat, hydroplane, or caterpillar. Miturich justified his argument as follows: “Technology aspires to straighten out the crooked paths and forms of space and to furnish itself with a hardness and strength so as to overcome the counter and lateral forces of the ambience. … Technology ignores the facts of intermittent movement and as well as the rhythms of the moving phenomena themselves. … The engines which I am proposing adopt—automatically—a complex undulatory movement and, technically speaking, are a valuable expression of a different kind of space and of movement therein, i.e., of time”.2 The airship or flying apparatus—the летун (Figure 8)—was also meant to extend this principle: there exist four drawings on one sheet dated 1923, a single design dated 26 March 1923, a project with an explanation dated to the 1920s–1930s, and a set of eleven sketches for an “airship based on the principle of ‘undulatory’ movement” of 1932.3 Judging from Miturich’s notes and drafts, the pilot of the letun would have directed the contraption by arms and hands only.

Figure 8.

P. Miturich: Model of a Letun (Flying machine), ca. 1927, 60 × 30 × 30, Wood, metal, parchment, Private collection.

Inevitably, Miturich’s machine elicits comparisons with Tatlin’s Letatlin which is more celebrated in part because much of the original body exists—and there have been many reconstructions such as this one produced for the Costakis collection now in the Museum of Modern Art in Thessaloniki. Suffice it to recall that Letatlin, too, was to have flown without fuel and with wings operated by the arms—plus a bicycle mechanism for take-off. Tatlin tested his prototype with modest success but seems to have shelved the project after 1932, crash-landing into heavy still-lives and textured portraits.

Miturich and Tatlin came to their respective constructions via different trajectories, although in the 1910s both achieved artistic maturity during the frenetic development of the airplane industry, witnessing the construction of all manner of flying machines. Tatlin talked of “iron wings” in a lecture in Tsaritsyno in 1916 and, as Nikolai Punin (1920) observed, the very incline of the Monument to the III International of 1919 was meant to symbolize the intergalactic impetus of Communist colonialization, i.e., of the planets. Miturich, on the other hand, cultivated a deep interest in ornithology and, as a student at the Battle-Painting studio of the Academy of Arts, learned how to paint machines of war, including airplanes. in 1915 he even tried to enter flying school4 and the following year took courses in military engineering, including airplanes and безмoтoрный пoлет.5 In 1925 Miturich accomplished his one and only flight between Moscow and Kiev which “remained vivid in my memory. … In fact, falling for a few seconds, weightless, only to ascend in quick bursts, is not very pleasant and you start to worry a lot about the wings—maybe they’ll break off as a result of such sharp tremors?”6

In any case, as an artist, soldier, and engineer, Miturich must have been very impressed by the huge flying apparatuses which Igor’ Sikorsky was designing in 1913–1914, i.e., the Grand and the Il’ia Muromets, which, incidentally, were quickly adjusted to the military exigencies of the First World War (Figure 9). Furthermore, the popular press ran countless articles on air and space, carrying exuberant renderings of airplanes and spaceships by professional engineers as well as by countless amateurs. With particular zeal, the press commented on the triumphs of the first Russian airplane builders, pilots, and aerodynamicists, giving pride of place to Sikorsky and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, and, obviously, Miturich (and Tatlin) followed these trends with particular enthusiasm. In 1930 Miturich, for example, witnessed the flight of the famous airship Count Zeppelin 127: “This morning I was woken up by boys shouting ‘Zeppelin’ … [you could see] the grey, metallic contour of [what looked like] a cloud. … Made two circles above the Kremlin. … Lots of airplanes circling. …. Extraordinary spectacle”.7

Figure 9.

Minister of War Vladimir Sukhomlinov (in white) and aeronautical engineer Igor’ Sikorsky (in black) standing in front of the Il’ia Muromets airplane, 1915.

What is often disregarded is that, during the 1920s, Miturich and Tatlin were well aware of each other’s aerial experiments and even, as their correspondence of 1926–1927 demonstrates, were ready to collaborate: On 1 April 1927, Tatlin wrote to Miturich: “I’ve thought through my research on the bird, although one thing is clear—we have very different ideas about implementing the model. … Some elements I have already produced in the model, others life size … I accept your proposal to participate in the work”.8 However, nothing came of Tatlin’s tentative call to join forces, and in 1929 their brief rapprochement turned into a condition of mutual distrust, enmity, and avoidance, caused, apparently, by Tatlin’s acceptance of the state commission to design Vladimir Maiakovsky’s coffin (Miturich interpreting this as an affront to the memory of Khlebnikov).

Of course, the evocation of an Aero-Constructivism does beg the basic question as to why Tatlin and Miturich, amateur inventors, could have arrived at such a crazy enterprise as a flying machine, reliant upon hand-controlled wings, which in strong winds would have spun out of control and crashed. In turn, their preposterousness does remind us that we now remember Russian Constructivism more for what it did NOT produce than for what it did. In any case, Miturich’s and Tatlin’s proposals were not especially revolutionary—by 1927 there were many gliders, aerospace engineering was evolving rapidly and the skies were full of airplanes. But why is 1927 so crucial? Perhaps the response is to be found in a particular event that took place in Moscow, triggering Miturich’s (and Tatlin’s) flights of fantasy and, for that matter, the interest of many of their contemporaries.

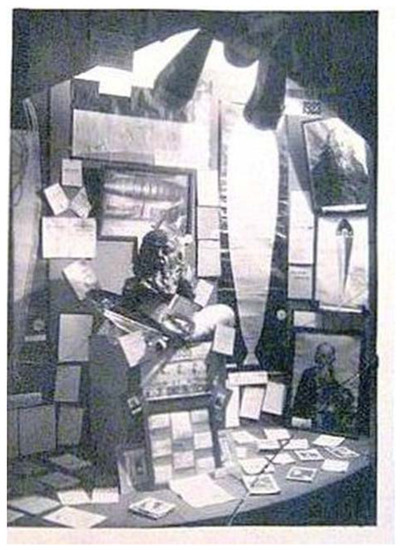

On 24 April 1927, a decade after Red October, an unusual exhibition opened at House 68 on Tverskaia Street in Moscow (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12). This was the “First Universal Exhibition of Projects and Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses, Devices and Historical Materials”, an extraordinary celebration of the ancient dream to conquer space and reach the planets of our solar system. Divided into national sections, the “First Universal Exhibition” gave pride of place to the discoveries and inventions of the modern pioneers of space travel from Robert Goddard and Tsiolkovsky to Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Consisting of diagrams and sketches of airplanes and rockets, three-dimensional models, artists’ impressions of celestial and galactic phenomena, and detailed explanations of velocity, traction, gravity, and so on, the “First Universal Exhibition” summarized the intense curiosity, enthusiasm, and passion which Russians, in particular, were manifesting towards the idea of manned air and space flight in the 1920s. Certainly, there were political and military dimensions to the exhibition, for one of the initial sponsors of the project was Feliks Dzherzhinsky and the aspiring Stalin is said to have visited the display, but, whatever its strategic importance to the Soviet regime, the exhibition can be regarded not only as a fundamental milestone in the history of Russian technology but also as a strong symptom of Russia’s Modernist mix of physics and metaphysics, astronomy, and astrology. The “First Universal Exhibition” received an enthusiastic public response, was discussed in the press, and from documentary sources, we know that Ivan Kudriashev, Aleksandr Labas, Vladimir Liushin, and probably Aleksandr Rodchenko visited the show. Given their special interest in flight, it is tempting to add Miturich and Tatlin to the list.

Figure 10.

The Konstantin Tsiolkovsky section at the “First Universal Exhibition of Projects and Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses, Devices and Historical Materials”, Moscow, 1927. Photographs from the handmade album entitled “First Universal Exhibition of Projects and Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses, Devices and Historical Materials” (no date, editor, or page numeration), Private collection.

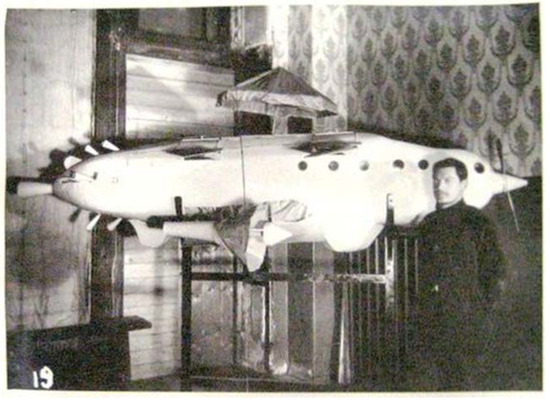

Figure 11.

Grigorii Polevoi in front of his Rocketmobile at the “First Universal Exhibition of Projects and Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses, Devices and Historical Materials”, Moscow, 1927. Photograph from the handmade album entitled “First Universal Exhibition of Projects and Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses, Devices and Historical Materials” (no date, editor, or page numeration), Private collection.

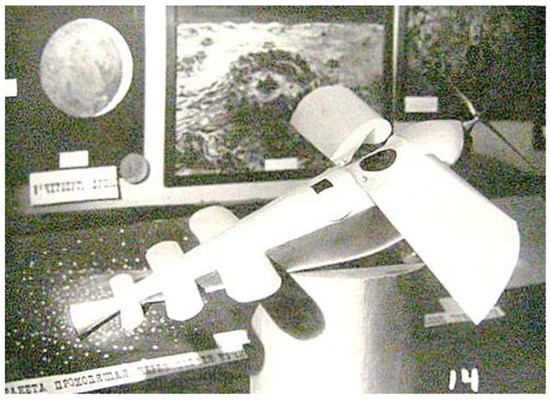

Figure 12.

Fridrikh Tsander: Model of an interplanetary ship. Photograph from the handmade album entitled “First Universal Exhibition of Projects and Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses, Devices and Historical Materials” (no date, editor, or page numeration), Private collection.

Not surprisingly, Tsiolkovsky commanded a primary position at the “First Universal Exhibition” of 1927, with didactic panels reproducing many of his drawings and statements (Figure 10). Although lacking a rigorous scientific and technical education, Tsiolkovsky, like Miturich and Tatlin, revealed an astonishing perspicacity and intuition, offering potential solutions to the major technical problems which hindered the development of air and space flight a century ago, e.g., liquid fuel, the multi-stage rocket, the effects of gravitation, the harnessing of atomic and solar energy, space stations, and many other related phenomena. Tsiolkovsky was represented here by models in wood and metal and numerous sketches and diagrams of trajectories, wind tunnels, airships, spaceships, and cosmonauts.

No catalog of the “First Universal Exhibition” was published, but the surviving photographs and reviews underscore the vision of its organizers—amateur inventors as well as professional engineers and, in a very tangible way, signaled a rich period of scientific and cultural gestation when numerous Russians were giving thought to the conquest of the air. One of the key sources of information is an album or scrapbook of original photographs and captions compiled by the organizers—members of the Interplanetary Section of the Association of Inventors and Inventists—and issued in three copies. The photographs of the airplane and rocket models, technical charts, and renderings of the planets provide us with a rich, graphic impression of that historic exhibition held almost a century ago. Grigorii Polevoi’s so-called rocket-mobile next to the Tsiolkovsky section attracted immediate attention.

(Figure 12 and Figure 13) Of direct relevance to this discussion of Miturich and his letun is the model of the winged rocket on display at the “First Universal Exhibition” designed by scientist Fridrikh Tsander, one of the most original and exciting of the early rocket engineers who went on to perfect his formula for jet engines and liquid fuel rockets which, he hoped, could be used for interplanetary flight. Trained at the Riga Polytechnic Institute (the alma mater of El Lissitzky, incidentally), Tsander built his first glider in 1909 and became so passionate about aviation, rocketry, and the potential conquest of space that he even baptized his children Astra and Mercury.

Figure 13.

P. Mitrich: Flying apparatus. Drawing No. 4, ca. 1922, Red ink on paper, Private collection.

At the 1927 exhibition, Tsander’s experimental vehicle took pride of place, for it offered a remarkably prescient solution to the problem of fuel consumption. In a lecture which he gave at the Moscow Society of Lovers of Astronomy in 1924, Tsander had already elaborated the principles of his aircraft, according to which the basic fuel would derive from parts of the metal structure itself which would be made of aluminum, magnesium, and plastics. In proportion as the aircraft gained in altitude, these materials (wings, fuel tanks, propeller, etc.) would become superfluous, would be directed into a special chamber where they would be crushed and shredded, then transferred to a boiler to be melted down and then fed into the jet engines as fuel. Tsander also entertained the idea of adding external mirrors which would capture the light of the sun (solar panels), cultivating a kitchen garden onboard, yielding fresh fruits and vegetables, and the engagement of a parachute to land. In other words, physically, the machine which arrived would have looked very different from the one which departed.

Set off against artists’ impressions of outer space and flight simulation, Tsander’s “Interplanetary Ship” was highly visible, just like Tatlin’s glider hanging in the Museum of New Western Art, and must have impressed the innocent and the prodigal alike. In 1932 (a few months before the test flight of Letatlin) Tsander (1932) published the findings in his book, Problema poleta pri pomoshchi reaktivnykh apparatov (The problem of flight using jet apparatuses), discussing the subject of jet propulsion, and, like Miturich, he also developed a manned glider which was meant to carry and be driven by a rocket, the basic concept being a tri-partite, winged vehicle also made of wood and controlled with pedals and flaps. The glider ran a successful test flight in March 1933, following Tatlin’s test flight the previous summer and coinciding with Miturich’s airship, “based on the principle of ‘undulatory’ movement”. Such experiments, pragmatic and prescient, led directly to the astounding accomplishments of the Soviet space program in the 1950s–1970s.

True, the cataclysm of Stalin’s Great Terror hindered and deformed the evolution of aerial and cosmic exploration. On the other hand, for those who adjusted and survived, aviation and cosmonautics represented an escape route from the oppression of everyday, maintaining—strangely enough—a continuity of both scientific research and aesthetic release throughout the Soviet period. For the more sensitive artists of that time, the aerial and the cosmic even became an alternative theme unadulterated by the triviality of material life, and Miturich, combining Constructivist technology with private imagination, never abandoned the theme of flight, drawing the interior of an airplane model workshop as late as 1954.9

A century ago, Miturch and Tatlin, Tsiolkovsky, and Tsander embarked upon what many regarded as a mission impossible, but their ideas, grandiose, incredible, and prescient, came to fruition and their artifacts, weird and wonderful, ushered the human race beyond the last frontier into interplanetary space. At the end of his 1915 Suprematist manifesto, Malevich declared: “Comrade aviators, swim into the abyss”,10 a sentiment which, even today, has not lost its energy.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For technical details of the model and the test flight see Miturich’s notes in (Rakitin and Sarab’ianov 1997, p. 104). |

| 2 | P. Miturich: “Dnevnik izobretatelia” (1933). Quoted in (Rakitin and Sarab’ianov 1997, p. 107). |

| 3 | See (Zhukova 1978), unpaginated. For illustrations of the volnoviki see (Miturich 2018, pp. 265–72). |

| 4 | See (Belokhvostova 2012): Petr Miturich, p. 20. |

| 5 | See (Rakitin and Sarab’ianov 1997): Petr Miturich, p. 278. |

| 6 | P. Miturich, untitled text supplied by Vera Khlebnikova-Miturich, Moscow. |

| 7 | See (Rakitin and Sarab’ianov 1997): Petr Miturich, p. 104. |

| 8 | Letter from Tatlin to Miturich dated 1 April 1927. Quoted in (Miturich 2008, pp. 321–24). The original is in the Khardzhiev-Chaga Archive, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. |

| 9 | Illustrated in (Rozanova 1973, p. 122). |

| 10 | Malevich ([1919] 1996): “Suprematizm” (first published in the catalogue of the “X State Exhibition. Non-Objective Creativity and Suprematism”, Moscow, 1919). Republished in A. Shatskikh, ed.: Kazimir Malevich. Sobranie sochinenii v piati tomakh, Moscow; Gileia, 1996, vol. 1, p. 151. |

References

- Belokhvostova, Natalia. 2012. Petr Miturich. Moscow: Catalog of exhibition at the State Tretiakov Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Мalevich, Кazimir. 1996. “Suprematizm”. In Kazimir Malevich. Sobranie sochinenii v piati tomakh. Edited by A. Shatskikh. Moscow: Gileia. First published in 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Miturich, Petr. 2008. Neizvestnyi Miturich, Materialy k biografii. Moscow: Tri Kvadrata. [Google Scholar]

- Miturich, Petr. 2018. Petr Miturich. Moscow: Tri Kvadrata. [Google Scholar]

- Punin, Nikolay. 1920. Pamiatnik III Internatsionala. Petrograd: NKP. [Google Scholar]

- Rakitin, Vasily, and Andrej Sarab’ianov. 1997. Petr Miturich; Moscow: RA.

- Rozanova, Natalia. 1973. Petr Miturich. Moscow: Sovetskii Khudozhnik. [Google Scholar]

- Tsander, Friedrich. 1932. Problema poleta pri pomoshchi reaktivnykh apparatov. Moscow: Oborongiz. [Google Scholar]

- Zhukova, Ekatherina. 1978. Petr Vasil’evich Miturich. Moscow: Catalog of Exhibition at the State Tretiakov Gallery. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).