2. Historical Context

The historical context of Gisbert’s work and its link to Goya’s requires some explanation. The painting depicts an event that occurred almost six decades prior to its creation, when the liberal General José María de Torrijos (1791–1831), and forty-eight of his followers, which included several leading Spanish liberals and a young Northern Irishman, were executed without trial on the beach of San Andrés de Málaga, on 11 December 1831, for high treason and conspiracy against Ferdinand VII. The painting forms an important relationship with Goya’s depictions of the Second of May revolt in Madrid and consequent executions,

Second of May 1808 and

Third of May 1808, as Goya’s and Gisbert’s paintings link two pivotal events in the reign of Ferdinand VII and the fate of Spanish liberalism, while key personages depicted in Gisbert’s work were involved in the events of 2 May 1808. The latter stemmed from an earlier event: the abdication of Ferdinand’s father Charles IV in March 1808 following a popular riot, and Ferdinand’s subsequent imprisonment by Napoleon, who planted his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne, sparked the beginning of the Peninsular War and the French Occupation. News that the rest of the royal family were to be moved to France resulted in the bloody revolt on 2 May 1808. The French reprisals resulted in the executions, at various locations in the city, of those known or suspected to be involved. Goya’s

Second of May 1808 commemorates the revolt while

The Third of May 1808 commemorates the executions of those shot on the hill at Príncipe Pío, Madrid. The Spanish successfully expulsed the French by early 1814, and Ferdinand was restored. In February 1814, Goya proposed to the provisional government that he ‘perpetuate by means of the paintbrush the most notable and heroic actions of our glorious insurrection against the tyrant of Europe’.

3 However, by numerous accounts Ferdinand, restored by the efforts of liberals, turned out to be much the tyrant. He disliked the liberal Constitution enacted in 1812, quickly abolishing it and restoring absolute monarchical power. Numerous uprisings occurred throughout the remainder of his reign, Torrijos’s final attempt occurring less than two years before Ferdinand’s death in September 1833.

Torrijos had been Captain General of Valencia and for a short time Minister of War during the so-called Trienio Liberal [Liberal Triennium] (1820–23) when Spain was ruled by a liberal government after a military uprising in January 1820, which temporarily unseated Ferdinand. One of numerous Spanish liberals living in London after Ferdinand’s restoration, Torrijos, by all accounts highly charismatic, became a magnet for the group of liberal-minded intellectuals around the poet John Sterling and known as the Cambridge Apostles, an informal debating society so named as its members had attended that university. Alongside Torrijos in London was Manuel Flores Calderón, a former Chair of Philosophy at the University of Santa Catalina, and a liberal politician and president of the Courts of the Liberal Triennium. In 1827 Torrijos and Flores Calderón formed the Liberal Board with Torrijos as military chief and Flores Calderón as its highest civil authority. Torrijos’s will to cause a revolution and topple Ferdinand found favour among some of the Apostles, including Sterling, who rallied for support around England despite severe illness, the poet Alfred Tennyson and his friend Arthur Henry Hallam, who travelled as couriers to revolutionaries in the Pyrenees, and poet Richard Chenevix Trench (future Archbishop of Dublin) and John Mitchell Kemble, the Anglo-Saxon scholar, who both sailed to Gibraltar (British territory) to meet Torrijos before entering Spain. Also attached to the expedition was Northern Irishman Robert Boyd, formerly a lieutenant in the Honorary East India Company’s 65th Regiment of the Bengal Native Infantry, who was introduced to the Apostles through Sterling, his cousin (

Boyd 1905, p. 763). Boyd, described as an ‘ardent, brave’ man and ‘a lover of liberty devotedly attached to the cause of the Spanish patriots’ (

Haverty 1844, p. 114), had agreed to donate his inheritance of several thousand pounds to help fund the expedition to Gibraltar.

4Torrijos, along with Flores Calderón landed in Gibraltar in September 1830, where among others joined with the aristocratic Francisco Fernández Golfín (1771–1831), who was Colonel of Infantry during the Peninsular War and among other notable things, was also one of the members who signed the liberal Constitution of 1812. In 1815 he was sentenced to ten years in prison when Ferdinand was restored but released during the Liberal Triennium. On Ferdinand’s return to power, he went into exile in Lisbon and Gibraltar. In 1831 Torrijos’s Pronouncement to restore liberalism to Spain was signed, which vowed to restore the Constitution of 1812.

The group made several attempts at disseminating the Pronouncement before December 1831, which were brutally put down. In their final attempt, Torrijos and around sixty men—that number being deemed sufficient as the operation was not military in character—fell victim to a trap masterminded by the treacherous General Vicente González Moreno (1778–1839), also the Governor of Málaga, who had previously promised them his own troops as support if they sailed to Málaga. They discovered Moreno’s betrayal when they were forced by the coastal guard vessel

Neptune to disembark at El Charcón, near Mijas, finally taking refuge at Torrealquería in Alhaurín de la Torre on 2 December 1831. On 4 December, after some fighting, they surrendered to Moreno and around three hundred troops, who incarcerated them in the prison in Málaga, and finally moved them to the Capuchin Convento de San Andrés de Málaga, from whence they were taken on the morning of Sunday, 11 December to the nearby beach of San Andrés, where Moreno had them shot without trial.

5 Torrijos asked to be allowed to give the firing order but was refused. The execution, as described by witnesses, was horribly bungled; it took the firing squad at least forty-five minutes to execute each group (twenty-four and twenty-five) of men, some of whom were horribly maimed.

6 The entire handling of the execution matched Moreno’s perfidious reputation: it was considered inappropriate in Spain at the time to carry out executions on Sundays, and, with the exceptions of Torrijos, López Pinto and Boyd, the gathered spectators were allowed to rob the dead, whose remains were then ‘flung into dust carts and cast into a ditch which had been dug in the Campo Santo’.

7 Boyd’s body, because it was that of a British subject, was retrieved at the execution site by William Penrose Mark, the son of the British Consul William Mark and brought to the Consul’s house, where it lay in state till the evening of the following day, when it became the first burial in the newly founded English cemetery (

Haverty 1844, pp. 121–22).

3. Content and Composition

Stood before it, the picture’s monumental scale with its life-sized central figures is deeply affecting. In the dull winter light and set against the backdrop of the sea-misted beach with the Convento de San Andrés in the left background, indicating the almost two-hundred metre walk from where the men were taken that morning, Gisbert presents the execution in progress. The leaders of the planned insurrection stand facing the viewer, while behind them, Moreno’s soldiers prepare to execute them. The central figures are separated from the viewer by a short stretch of sand populated by those already executed and whose bodies extend beyond the picture frame, as such positioned, more or less, at the viewer’s feet. Placed somewhat obliquely relative to the standing group, the viewer becomes an onlooker, a witness, close enough to easily read the troubled expressions on the faces of the condemned men, who stoically—even defiantly—prepare for their fate while the friars, who had accompanied the men for final prayers and walked with them from the monastery to the beach, assist with blindfolds. Torrijos, fourth from the right in a long brown overcoat, firmly clasps the hands of Fernández Golfín on his left and Flores Calderón on his right; the hands thus link the three most important Spanish liberals in the work. On Flores Calderón’s right is career soldier Lieutenant Colonel Juan López Pinto (1788–1831), a childhood friend of Torrijos who had fought against the French occupiers in the 2 May Uprising in Madrid in 1808 (and again explicitly linking Goya’s

Second of May 1808 with Gisbert’s painting), who had been a senior politician in Calatayud in 1822 and participated in the defence of Cartagena the following year, leading to his exile in France, Belgium and England. In England he subsisted on giving drawing classes, a skill he had taught as a teacher at the Academia de Artillería [Artillery Academy] in Segovia. From London he travelled to meet Torrijos, at the latter’s request, in Gibraltar.

8 The tall figure next to López Pinto is easily identified as the twenty-six-year-old Robert Boyd, who cuts a Romantic, noble figure, with his distinctive red hair, fair complexion and dark green overcoat, the latter which further suggests, perhaps imaginatively on Torrijo’s part, his Northern Irish heritage. It was not the first time that Boyd, born in Templemore, County Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland, was moved by revolutionary causes. Boyd had fought in the Greek War of Independence (1821–32), which famously counted the Romantic poet Lord Byron, like Boyd, on the Greek side. To Boyd’s right is a third military figure, Francisco de Borja Pardio (c. 1791–1831), who during the Peninsular War was captured by the French and due to be executed. War commissioner during the Liberal Triennium, he went into exile in Gibraltar in 1823.

The serenely proud, strikingly dressed figure next to de Borja Pardio, which is not identified, may have been intended by Gisbert as a symbol of Spanish liberty. His attire brings to mind the lush fabrics and embellishments of Spanish dress of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, such as that of the

majos, who belonged to the lower Spanish classes (and were famously depicted by Goya) and were well known for their elaborate traditional Spanish outfits, which unusually, were even copied by the higher classes. Though the long trousers were uncommon in

majo clothing until later in the nineteenth century, the short jacket, ornate brocaded and embroidered waistcoat and red wool cap were fashionable in Aragon and Catalonia, for example, and he wears typical

esparteñas (or

alpargatas) [Spanish] or

espardenyas [Catalan], traditional Spanish shoes today known by the French word,

espadrille (

Figure 2). Notably,

majo clothing arose as a vindication of native Spanish style in reaction to the ‘Frenchification’ of fashion. It does not seem incidental that his red cap closely resembles the Phrygian cap, a version of which is the

bonnet rouge [red bonnet] of the French Revolution, which by 1831 was widely used to signify liberty.

9 Finally, the friar who ties the blindfold for Fernández Golfín has been identified as a self-portrait. Here, noted Adrián Espí, an early biographer of Gisbert, ‘Let us look at his face, removing his monk’s hood for a moment; what we see is an almost bald head; here we have his distinctive nose, his eyes sunk in their sockets, his chin covered with a grey beard’.

10 While the inclusion of a self-portrait is a common device among artists, its inclusion here, as in the

Comuneros of Castille, proclaims Gisbert’s liberal standpoint.

5. Findings: Artist’s Research and Design

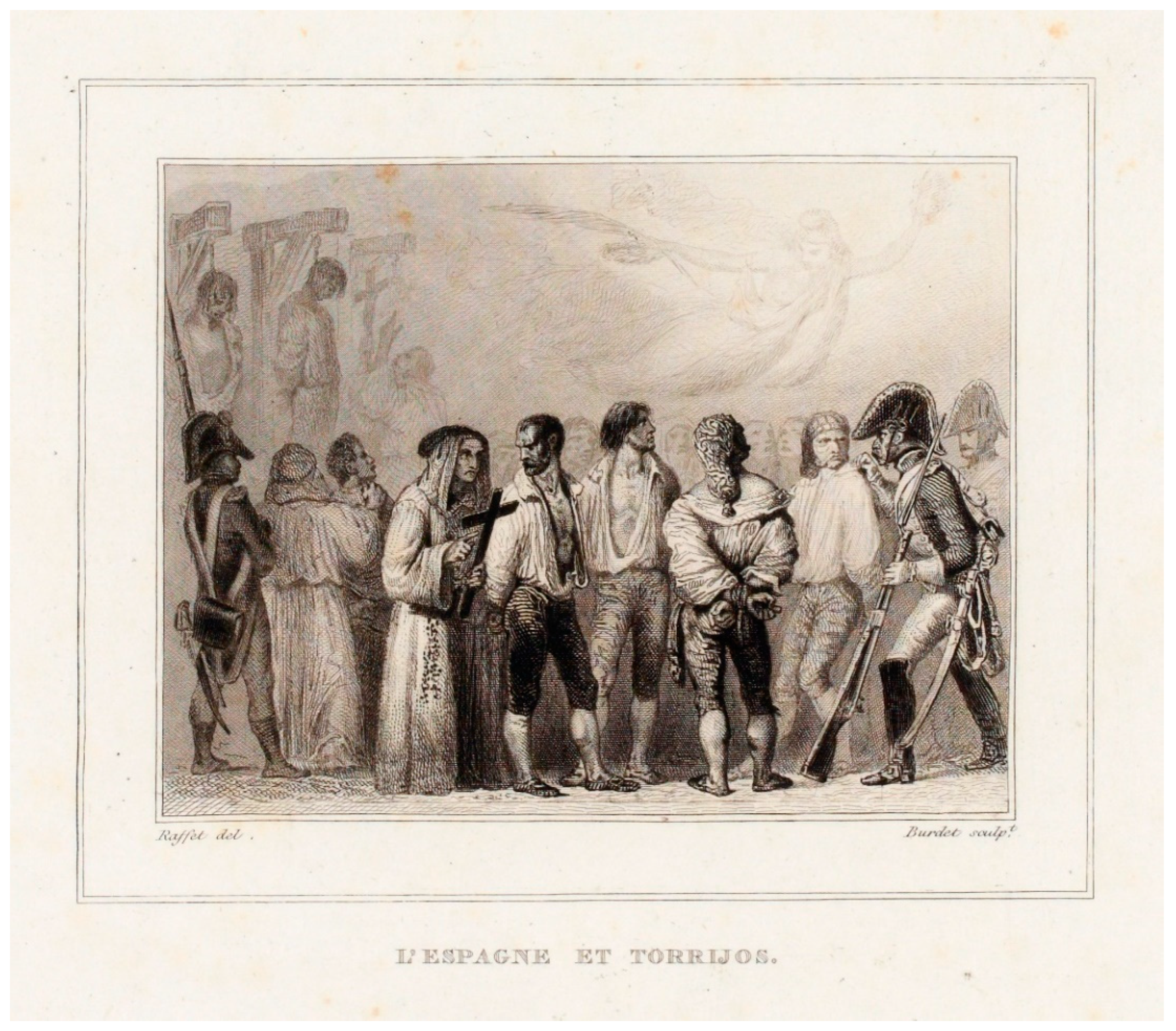

While the rationale governing the painting’s creation are clear, Gisbert’s decisions regarding its design are not. As a point of departure in recording the event, Gisbert could look to little in the way of visual precedents apart from the etching,

L’Espagne et Torrijos (1835,

Figure 3) by the French artist Auguste Raffet (1804–1860), a highly Romantic, imaginative work. The latter shows those awaiting their fate, none of whom are clearly identifiable, dressed in popular

majo clothing (including the elaborate hairnet) and an allegorical figure symbolising freedom crowns the dead with a laurel; however, the dead are incorrectly shown hanged.

11 While Gisbert knew the succession of events far better, he was tasked with recording the event effectively in line with his brief and portraying the leaders as accurately as possible, while forced to rely on inconsistent artistic representations of them.

According to the article in El País on 19 June 1888, Gisbert took great care to ensure that the location of the execution and the men were portrayed as closely as possible, travelling from Paris to Málaga to sketch the landscape and enquire about the men’s identities:

It cost him a lot of work; he had to undertake a trip to Málaga and gleaned a large part of his painting from nature, and enquired here and there into the slightest details, so that the [men] turned out to be similar to those heroes who sacrificed their lives for the sake of freedom. The canvas depicts part of the beach at Málaga, bordered on one side by the sea, and on the other by high mountains. [Between those about to be shot] is General Torrijos, the great victim of the Bourbons, whose raisin-toned dress coat is exactly the same as that which he wore (

Anonymous 1888, p. 2).

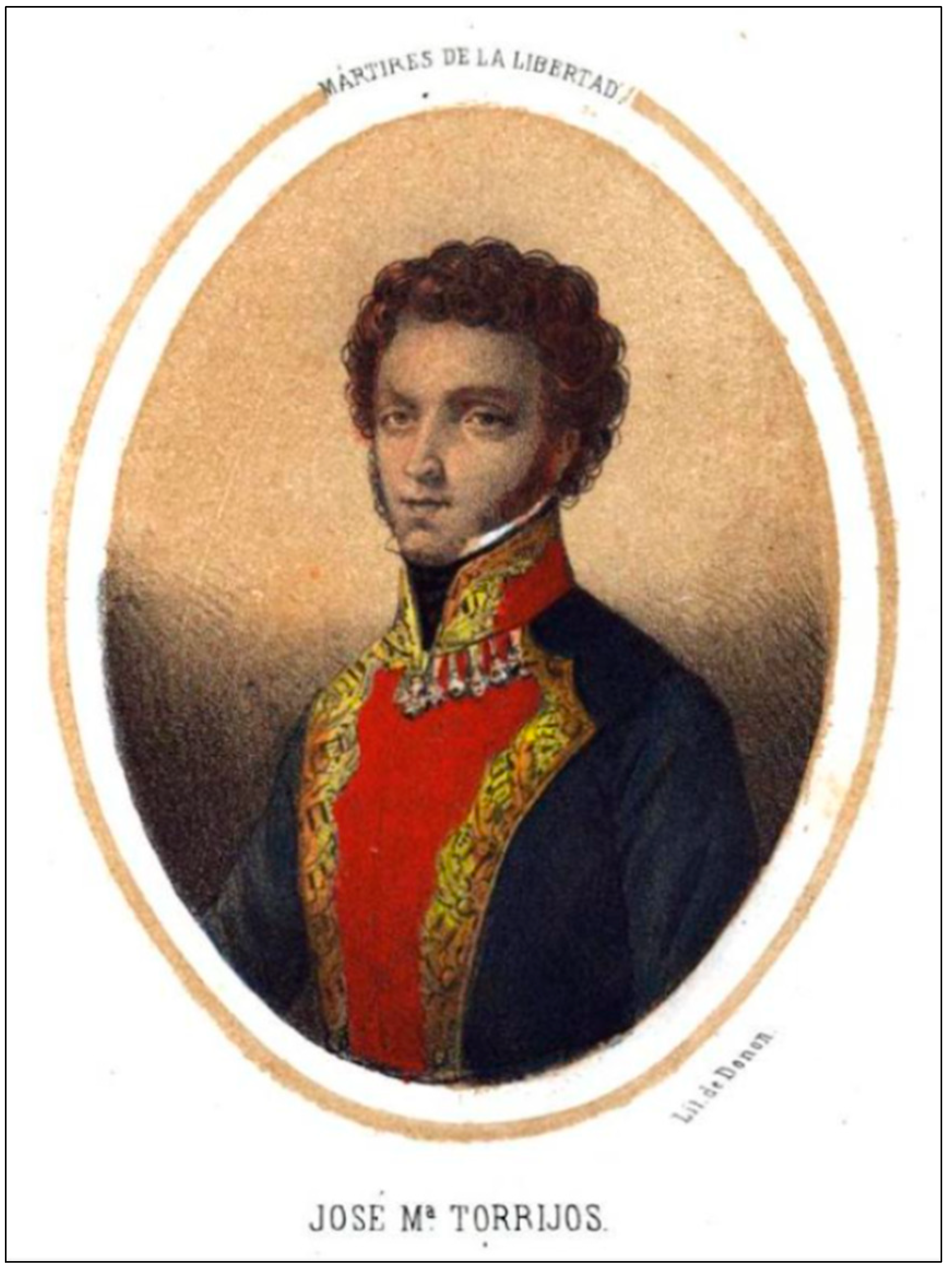

As Gisbert’s work shows, the location at that time was uninhabited, and thus suited to the grim operation at hand. But surviving archival and later written accounts reveal, however, that Gisbert’s portrayal of the men and presentation of the execution differ in certain details from the real event. As 1831 predated portable photography, Gisbert had to rely mainly on secondary artistic images of the men to establish their identities. While it is not known in every case what source material the artist used, there were numerous illustrations of the men in print media—typically bust-type imagery—which offered Gisbert an approximation of their features. In the case of Torrijos, the artist may have known of the fine portrait by Ángel Saavedra, completed while both Torrijos and the liberal Saavedra were exiled in London (

Figure 4). The work expresses Torrijos’ persona as described by John Kemble, who deeply admired Torrijo’s courage, charisma and cunning, and Sterling’s friend, the essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle, who described him as a ‘valiant, gallant man; of lively intellect [and] of noble, chivalrous character (

Nye 2015, p. 5;

Carlyle 1851, pp. 86–87). Also in circulation across the intervening decades were the numerous, though posthumous, ‘portraits’ of Torrijos in print which like Saavedra’s portrait, show him with curly hair and fashionable sideburns but unlike the portrait, depict him in military attire (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6); the full-figure images could indicate for Gisbert Torrijo’s physique.

12 Gisbert’s depiction, with dark eyes and wavy rather than curly brown hair is at odds with Saavedra’s portrait, which shows Torrijos with blue eyes, a light complexion and abundant rich brown curls. Assuming that Gisbert wished to portray the men’s features faithfully, as suggested by his trip to Málaga and depiction of other figures discussed below, it seems unlikely that he had seen Saavedra’s work, and depended, possibly, on one of the widely circulated prints for a likeness; these, however, were not dependable. A colour lithograph dated 1853 by Julio Donón shows Torrijos with wavy rather than curly hair and dark brown eyes. The lithograph appeared in the second of the two-volume

Los mártires de la libertad española [The Martyrs of Spanish Liberty], a significant publication that may have reached Gisbert and influenced his work (

Amellar and Castillo 1853, vol. II, p. 503). Additionally, the facial shape in Donón’s image, at odds with the heavier jawline in Pedro Barcala Sánchez’s piece, is closely matched by Gisbert (

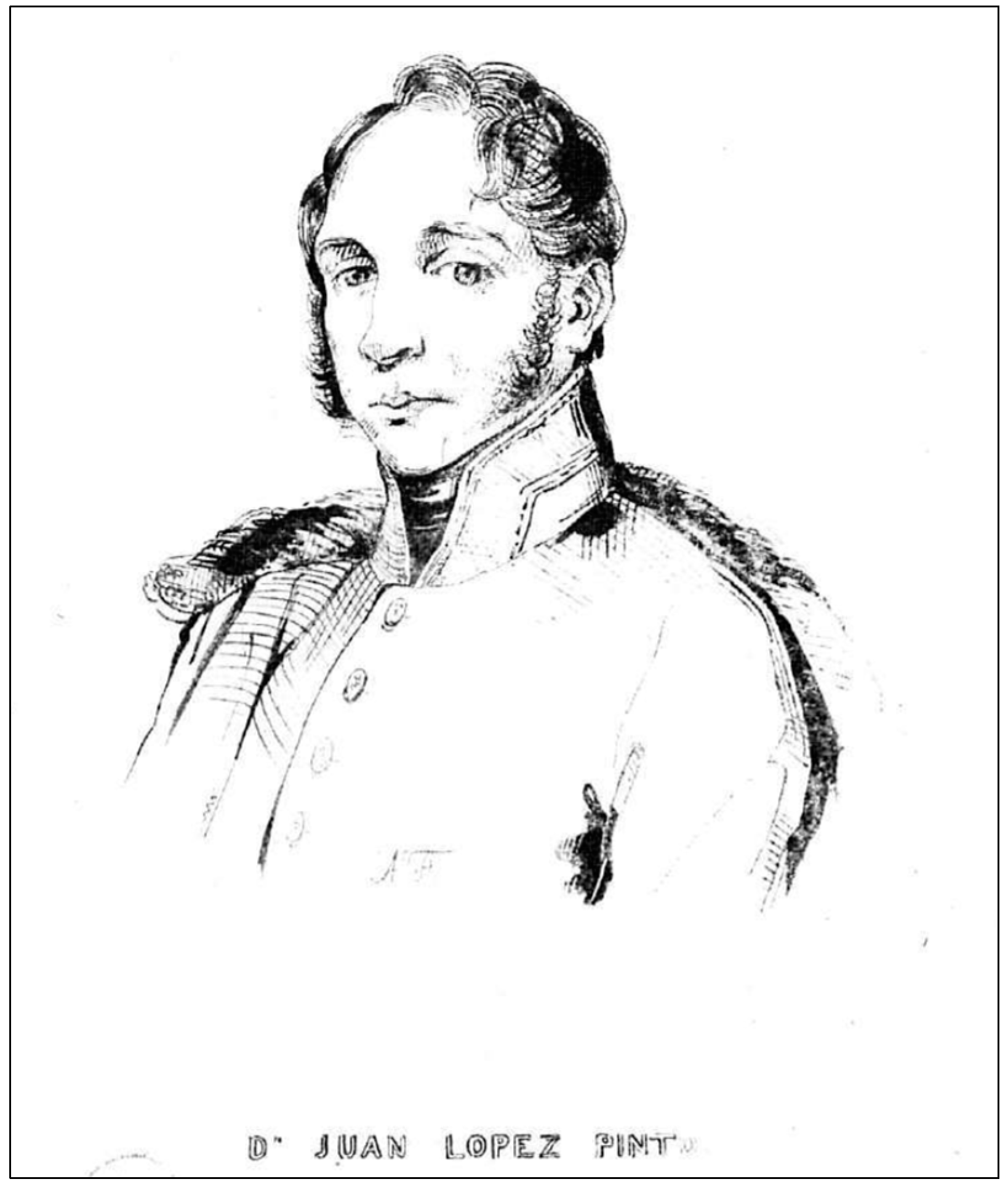

Figure 7). The same issue is present in the case of Juan López Pinto (

Figure 8), where Gisbert’s portrayal approximates somewhat to that again provided by

Los mártires de la libertad española (

Amellar and Castillo 1853, vol. II, p. 256) but which differs wildly from an image that offered a more verifiable likeness, that of the lithograph that appeared in the magazine,

Observatorio Pintoresco, which, it seems, was based on a self-portrait (

Figure 9).

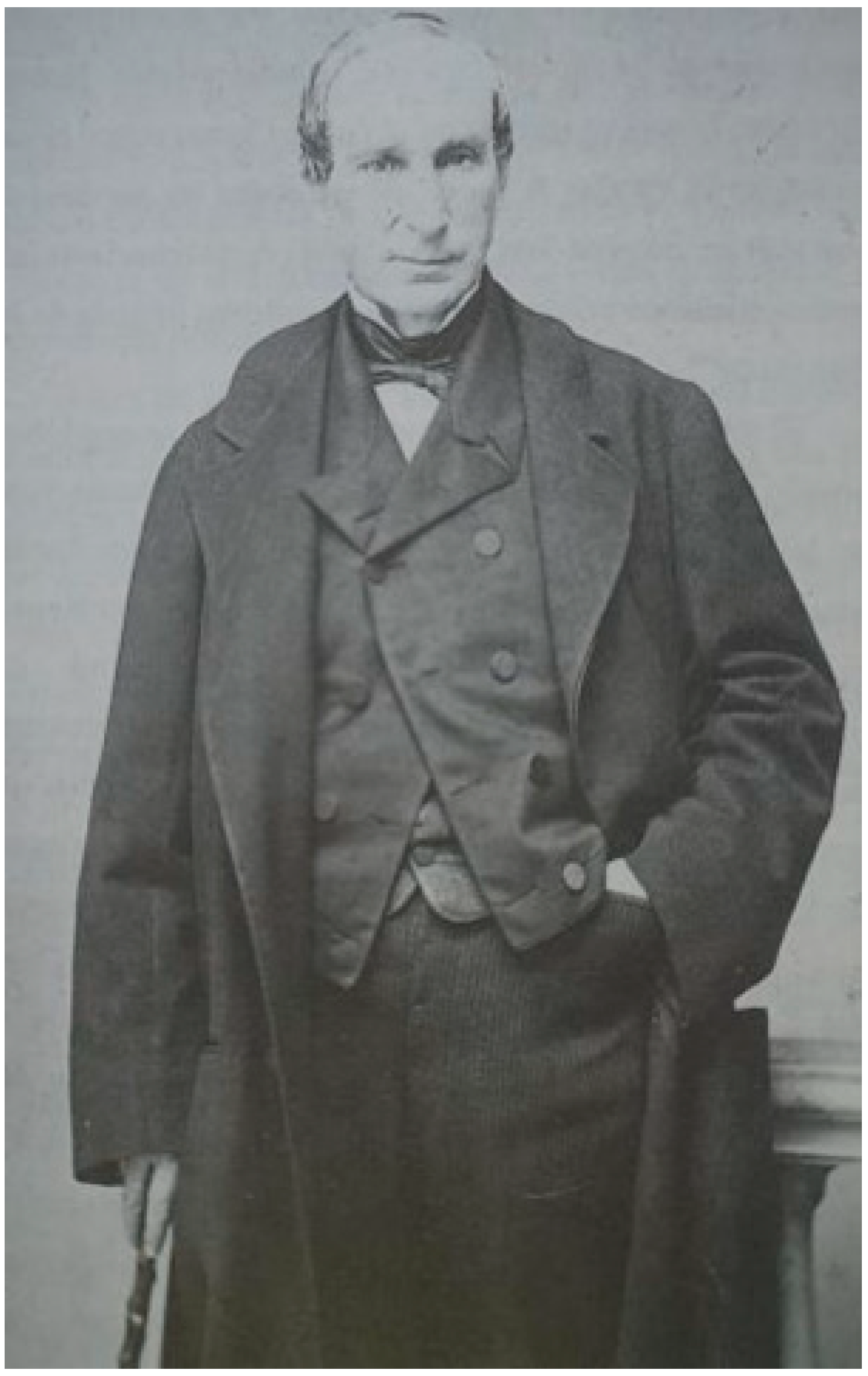

13Art historian Manuel Bartolomé Cossío (1857–1935), great-grandson of Flores Calderón, writing on the hundredth anniversary of the executions, noted that there were neither ‘miniatures nor portraits’ of his ancestor. As such, ‘Gisbert had to rely on a photograph of [Flores Calderón’s] son Lorenzo’ (

Figure 10). It is not clear to what extent Lorenzo resembled his father but at least, it provided the artist with a veritable link to Manuel Flores Calderón as well as the events leading up to the executions: Lorenzo had accompanied his father during his exile, but stayed behind in Gibraltar, thus saving his life.

14Gisbert fittingly portrayed the noble bearing and strength of character of the aristocratic Fernández Golfín, the eldest of the leaders. It is known that Fernández Golfín was almost blind by the time of the executions, which may be the reason why he is shown blindfolded (

Fernández Golfín 2018). Yet, the facial profile may be based on that of his son Antonio, as a photograph of the latter at approximately the same age reveals.

15In the case of Boyd, his nephew’s description of him alongside the black and white illustration of a colour miniature of Boyd at the age of twenty-two (

Figure 11), provides valuable insight to how the colour miniature looked:

One miniature hangs among old family relics which is worthy of notice. It is of the regulation large size. It belongs to the period when the miniature painters began to forget their true function, and to be misled by the ambition of prettiness of effect, but it is a good specimen of that perhaps mistaken period. It represents a young man some two-and-twenty years of age. His eyes are blue, his complexion fair, his features irregular but not insignificant. His face, which is clean shaven, is crowned by an abundant crop of light brown hair. He looks out on one with a glance of modest daring, not unmixed with some humour and sentiment. It is the portrait of my uncle, Robert Boyd, whose tragic story stirred deeply the hearts of Englishmen some seventy or eight years ago.

16In the account of Irish historian Martin Haverty, Boyd is described as a ‘slight, fair-haired young man, of interesting appearance and prepossessing demeanour’ (

Haverty 1844, p. 18). The boyish features, if not Boyd’s colouration, and slight physique, bear little resemblance to Gisbert’s portrayal, however. But another image, a typically small silhouette produced using a physionotrace and still in the possession of Boyd’s family, closely approximates to the stronger, more mature and more defined features in Gisbert’s work. Given the characteristic precision of portraits produced using the physionotrace, the silhouette provides a reasonably reliable likeness, indicating that the artist’s source material, if not the physionotrace, was a newer, more mature image of Boyd (

Figure 12).

Unlike the foregoing illustrations of Torrijos, López Pinto and de Borja Pardio in their military attire, Gisbert depicted the men in civilian clothing, which was in line with the purpose of the non-military expedition. Thus, all the men are depicted as civilians, which, as Javier Barón also considers, heightens the barbarity of the executions (

Barón 2019, p. 31).

As noted above, the painting does not faithfully depict the conduct of the executions. For example, it was recorded that the men were already tied in a line by the arms before they were taken from the monastery (

Haverty 1844, p. 120), but it is known from a letter by one of the friars, José Joaquin Zapata, Fernández Golfín’s confessor, to the latter’s cousin, that the leaders were executed first, meaning that the executed figures in the foreground are a compositional device.

17 Additionally, that one of the figures to the left is already positioned blindfolded and kneeling suggests that all the men were placed as such—that is, shot from behind; but this was not the case. Zapata also confirmed, as did Robert Boyd’s nephew William Boyd Carpenter, that the entire group were shot kneeling:

18At nine in the morning, they left to be shot, accompanied by us and a column of soldiers of the line. The first to break the march were Don Francisco Fernández Golfín, I was going by his side, as each priest was next to the confessed who attended, Torrijos, Flores Calderón, López Pinto and all the distinguished people were also, until they formed a string of twenty-four, those who all at the same time, kneeling and blindfolded, were shot in the chest, that is, from the front.

19Furthermore, several accounts concur that the men were in a poor physical state, having been tortured and confined in heavy chains, and refused food for the eighteen hours leading up to the executions, and Mark Boyd reported that the men were also previously stripped by convicts (

Boyd 1871, pp. 268–69). The minimal appearance of blood and wounds on the fallen men is at great odds with what actually happened. The dreadfully inefficient shooting over a prolonged period ensured the bloodbath that Haverty described as a ‘massacre’; half of Boyd’s skull remained in the sand when his body was moved, and the execution of the second group was even more brutal (

Haverty 1844, p. 121). An account of the execution in a letter written by a Capuchin friar who attended many of the victims recalled that ‘it was […] necessary to bring some sort of gravel to cover the excessive quantity of blood which remained on the ground in consequence of the repeated wounds received by the greatest part of the unfortunate men.

20Yet, these differences, and given the painting’s purpose as a monument to liberty, very probably reflect decisions on Gisbert’s part to alter certain details in order to present the men in a manner that emphasised their dignity and bravery. Despite the high tension of the moment depicted, the leaders exude an almost transcendent calm and the heroic demeanour that fills accounts of the executions and is reflected in their final letters; only the eyes of López Pinto, the clenched hands of Flores Calderón, Torrijos and Fernández Golfín, and the furrowed brows of Torrijos and López Pinto indicate their predicament.

21 The earlier of two surviving preparatory drawings reveal that originally, Gisbert had included three additional figures to Fernández Golfín’s left, one of whom looks beyond the picture frame and appears to cry out, arm raised in a final act of defiance. Additionally, Torrijos looks directly at the viewer, effectively linking the space within the image to that beyond it (

Figure 13). While arguably Torrijo’s direct gaze would have created a more poignant final work, the removal of the raised arm preserves the work’s sobriety, of what is essentially a frieze formed by the row of standing figures, and imbues the picture with a still, but not stiff, monumentality. The focus on the leaders, shown physically unscathed, with the firing squad relegated to the background, creates a kind of mise-en-scène, where the beach becomes a kind of theatre on which the men, centre-stage, seem somewhat removed from the bloody events, and their identities clearly preserved for memory. Though possibly incidental, the fact that the firing squad is placed behind the men and suggests that they were shot in the back, is perhaps a reference to Moreno’s betrayal.

Gisbert’s sombre, sober work betrays the tendencies in Spanish painting of the second half of the nineteenth century, when large-scale history painting remained the gold standard within the Spanish Academy. Stylistically, the painting is categorised as representative of a movement in the country known as Spanish Eclecticism, where artists borrowed aspects from various existing styles but preserved the ‘correctness’ in drawing and tightly painted details of classically inspired models. With the exception of developments in Catalonia that included the pre-Impressionism of Mariano Fortuny, Gisbert’s work reflects the comparative lethargy among Spanish artists in adapting the innovations in French art since the 1840s. As is generally the case with academic painting from this period, it now represents one of the lesser studied and most criticised periods in Spanish art. Yet, though such art remains typically far less studied in universities than developments in modernism, academic art has begun to be readdressed and re-evaluated in recent decades. Certainly, as we have seen, Gisbert’s work is a far cry from the figurative idealisation associated with academic art, and the result of much effort on the part of the artist to represent both the geographical location and Torrijos and his men naturalistically. The modelling of the figures, relatively loose handling and tonal range of paint and composition in Gisbert’s work have more in common with Gustave Courbet than J. L. Gérôme, two leading French artists who in the 1870s represented the epitome of academicism on one hand and reaction against it on the other. Indeed, where Gisbert comes closest to Gérôme, probably the most famous painter in the world while Gisbert was in Paris, is in what is perhaps Gérôme’s least characteristic and most political, controversial painting,

The Execution of Marshal Ney (1868) (

Beeny 2010, p. 42). Javier Barón has noted the possibility of Gisbert referencing this work due to the detail in both paintings of the fallen top hat (

Barón 2019, p. 43). The

Execution of Torrijos also clearly betrays aspects of modernism. The executed figures in the foreground are partly cut off rather than contained within, a feature typical of impressionist and modernist work influenced by photography, where pictures were commonly composed like a haphazard photograph, creating the impression of accident or lived experience.

If in the artistic sense Gisbert’s painting successfully and enduringly conveys the heroism of Torrijos and his followers, and by extension the struggles of liberalism and Spanish politics and society throughout the nineteenth century, one might question whether the painting represented, by its commission in the 1880s, a truly liberalised Spanish state. The very particular conditions of its commission suggest the triumph of liberalism over what had been essentially a feudalist system in the earlier nineteenth century. The facts show that this was not the case. If in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Spanish liberalism was revolutionary in intent, as Torrijos and his men demonstrated, from the 1860s the liberal authorities were, in Spain as in other continental European nations, seen as elitists who were out of touch with most of the population. If the Spanish masses were no longer the vassals of a tyrannical monarchy, and numerous measures were employed over time to improve the lives of the poor, many compromises were made for prominent monarchists and antiliberal factions, which were already crippling liberalism in the country during the first exhibition of Gisbert’s painting in 1888. Such dangerous allegiances helped ensure Spain would fall victim to authoritarian right-wing take-overs in the aftermath of the First World War (

Smith 2016).

6. Conclusions

Though Gisbert’s painting was not a faithful retelling of the bloody events of 11 December 1831, nor reflected current sociopolitical truths to the fullest, it is clear that the artist’s decisions regarding its design fulfilled its brief as a monument to the struggle for Spanish liberalism in the first half of the nineteenth century, which has been confirmed through the work’s enduring popularity and generally positive reception then and since.

22 Its success as memorial was especially marked during the centenary commemorations, when it was reproduced and discussed, as in the two-page spread in one of Spain’s most widely circulated newspapers,

ABC, on 10 December 1931 (

Figure 14).

23 Not least, the painting asserts Gisbert’s individuality and independence as a painter, who was tasked with creating a work that would be housed under the same roof as that of Goya’s

Third of May 1808, the most famous of all works on the theme, with which Gisbert’s work would be readily compared. He could not do as Edouard Manet did in his series of works titled

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867–69), which paid homage to Goya. Instead, as we have seen, the work was the result of much careful deliberation, over a period of two years, that tread a careful balance of both having to satisfy to some extent the traditional tastes and expectations of the Spanish government and Prado officials who had commissioned the painting while creating a work that was sufficiently original and contemporary in its rendering of the theme. The young but already respected art critic Jacinto Octavio Picón wrote of the work:

The moment chosen by Mr. Gisbert, the arrangement of the groups, especially the main one, and the terrible simplicity of all that, where there is no theatrical detail or elaborate exaggeration, suggest that this must have happened. […] The latest work by Mr. Gisbert is admirable; the inhumanity of the deed that it commemorates produces the impression that it should cause: although by a different path, it has obtained the same effect that Goya achieved with his famous execution [

3 May]. Mr. Gisbert, rightly wishing to move [the viewer] more intensely, has preferred to cause an emotional response with the noble dignity of those who are about to die than [depict] the brutality of the deed. […] The sensation produced by his work is no less intense because of the absence of blood. […] The painter has doubtlessly studied the epoque in detail. That is how the men dressed, and that is how they looked (

Picón 1888, p. 2).

Gisbert’s monumental painting, situated stylistically between academicism and realism, is a remarkable example of Spanish nineteenth century painting, which through the originality of its composition and sensitivity in its depiction of its subjects, manages to reach beyond the constraints of the academicism in which its creator was schooled. As an artistic and cultural monument, it is arguably as important to Spanish cultural identity as Goya’s great work in tracing visually Spain’s turbulent history and a fitting memorial to those who shaped it.