1. Introduction. State of Research

The art of socialist realism was a doctrine that required artists to present “a true—as recorded in 1934 in the Statute of USSR Writers—concrete historical picture of reality in its revolutionary development. Truth and historical relevance must be linked to the ideological reconstruction and education of the working people in the socialist spirit” (

Tuмoфeeв and Typaeв 1972, p. 93). The above-quoted definition of socialist realism, one of the earliest ones, does not leave any illusions about the purpose of introducing a new artistic direction, which consisted of social propaganda and the associated control of artists and their creations. The new art, with people acting as its patron through the apparatus of power, was supposed to be easy in reception, and at the same time formative for both the reality and its recipients. The foundations of socialist realism were programmatically laid in Soviet Russia, based on Lenin’s “Plan of monumental propaganda”; artist training institutions educating the performers of “committed works” were also intensively built. In the context of the later imposition of socialist art patterns on the artists of the “Eastern Bloc” countries, in the initial period, socialist realism developed somewhat in the shadow of avant-garde art, whose representatives usually supported the “proletarian revolution”. In the 1930s, as a result of Stalin’s personal choices, socialist realism was opposed to the avant-garde and became the only valid trend in Soviet art. Semantically open abstract concepts were replaced by figurative representations carrying an unambiguous ideological message. Socialist realism works were intended to “strengthen the will and courage of socialist society, the sense of brotherhood of nations, love of the fatherland”, developing “the artistic taste in people, enriching them with new ideas and pointing the way forward” (

Бoльшая 1947, p. 244).

After the end of the Second World War and once post-war Europe had been divided into a democratic West and a central and eastern part subjected, as Winston Churchill stated, “to a high and increasing degree of Moscow’s control”, socialist realism was introduced in the countries subordinated to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. As early as November 1947, Boleslaw Bierut, the President of the Republic of Poland announced that “art cannot cause doubt in the working class, is supposed to be a source of enthusiasm, belief in the socialism’s victory, the great work of the state reconstruction” (

Bierut 1947, p. 4). Two years later, socialist realism was given the status of the official and only accepted artistic method. Unlike in the Soviet Union, where socialist art continued to develop until the collapse of the empire in 1991, socialist realism was abandoned in Poland as early as 1956 in a wave of political change. However, many sculptures had been created by this time; these were materially permanent “historical notions” (

Young 2003, pp. 234–35), some of which, exhibiting, apart from being works of propaganda, some artistic qualities.

As already mentioned, this paper mainly aims to show the developmental line of Polish sculpture from 1949–1956 against the background of Soviet aesthetic and ideological patterns. This goal is well reflected in the structure of the text. The first two chapters present the assumptions of Lenin’s “Plan of Monumental Propaganda” and attempts at their realisation, as well as some examples of works by Soviet sculptors which are considered iconic of this style until today. The third chapter discusses in some detail the process of introducing socialist realism in Poland, as well as the paradigms of the new art and its relationship to former artistic styles. The subsequent three chapters discuss the evolution of forms in Polish socialist sculpture in the heroic (great genre scenes—the building of socialism, struggle for peace, mausolea, the victory of the Red Army and the Polish army over Germany), portrait (monuments to theoreticians and leaders of the Bolshevik revolution, leaders of the socialist countries, national and folk heroes) and architectural–decorative trends (mainly large-format bas-reliefs decorating residential and public utility buildings), depicting the history of the creation of the most important works of the epoch and their meaning.

Much has been written about socialist realism both in the Soviet Union and in Poland, but before the changes in the system, that took place in both countries at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s, critical texts almost always remained unpublished. In Western Europe, however, research on Soviet art had been conducted as early as in the 1940s, mainly in a philosophical and aesthetic context, with one of the most important publications of this time being John Somervill’s essay on the Leninist vision of art and its social references (

Somerville 1945). Texts by Soviet critics were also published in Western Europe, including Andrei Donatovich Sinyavsky, who in 1957, under the pseudonym Abram Tertz published a dissertation entitled “What is Socialist Realism?” (

Tepч [1957] 1999). In response to the question thus posed, the author juxtaposed the art of socialist realism with the teleology current. According to Tertz, artistic activity was subordinated to the “superior goal” of building communism, it was “refined” through this goal. However, it was not the art that created reality, but it was rather a tool to help to make this reality correspond to the ideal of the new social system. Tertz already saw a contradiction in the name of “socialist realism”, because he thought that “purposeful, socialist” art could not be implemented by means derived from 19th-century realism. C. Vaughan James in his book published in the early 1970s defined socialist realism as “a worldwide phenomenon that arose under the influences of the great social changes at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth – the sharpening contradictions within capitalist society, the crisis in bourgeois culture and the rise of a socially conscious proletariat” (

James 1973, p. 85). Although the theses included in James’s work have not stood the test of time, its value was in presenting readers with translations of original Soviet documents from the 1920s and 1930s. The discussion on the aesthetics of Soviet art continued into the 1980s, when Boris Groys, in his best-known work on the culture of the Soviet Union in the Stalinist era, entitled “Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin. Die gespaltene cultures in der Sowjejenion” argued that socialist realism did not stay in history but has left it definitively (

Groys 1988). In this way, artists were able to refer to classical models, which were understood not in terms of aesthetic criteria, but rather as an attitude, reactive or progressive. For socialist realism, the end of history translated into an opportunity to use the art of the past, which became a meaningless collection of artefacts. By using the word “Gesamtkunstwerk” in the title of the book, Groys equated socialist realism to the Wagnerian “total work”, in which however, all artistic (and life) domains were linked with the idea of Communism. English-language publications on the art of socialist realism, published at the end of the 1990s were collected and analysed by Marek Bartalik in a paper entitled: “Concerning Socialist Realism: Recent Publications on Russian Art” (

Bartelik 1999). However, almost all the books and articles mentioned there related to graphics and painting except for works by Matthew Cullerne Bown, in which the author presented various aspects of Soviet art from 1917–1922 (

Bown and Taylor 1993) and the Stalinist era (

Bown 1991).

Today, the backstage of the implementation of the “new art” is widely discussed (e.g.,

Kruk 2008;

Lampard 2012;

Silina 2016), documents to which researchers have not yet had access are analysed (

Mileeva 2019), while at the same time addressing doubts relating to the identification of today’s society with the art of socialist realism, referring to the need to protect the “Soviet heritage” mainly in the countries that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union (e.g.,

Kačerauskas and Baranovskaja 2021). Only a few years ago, one of the most conservative publishers, the Great Russian Encyclopedia (formerly the Great Soviet Encyclopedia), in the entry on socialist realism, included a mention on “dogmatism and intolerance” of this creative method “especially in post-war years when its principles were introduced in art in the communist bloc countries” (

Юpченкo et al. 2015). The authors’ attempt to grant an objective perceive to socialist realism must be regarded as a breakthrough since it has thus far been defined as “the leading artistic method of the modern era” and “a new type of artistic awareness” (

Маркoв and Тимoфеев 1976, p. 236). From the perspective of the countries of the so-called “Eastern bloc”, this “introduction” of socialist realism was a form of coercion, imposition on the artists of foreign ideological values, which temporarily prevented the free development of art. In Polish literature on socialist realism three periods can be distinguished: the “foundation period”, when the superiority of socialist art over other currents of artistic creation was enthusiastically argued, followed by a period of rejection, when socialist realism was not subject to analysis and discussion in an attempt to forget it, and then a period of renewed, already critical interest in the achievements of artists of that epoch.

The first critical work on Polish art of socialist realism, written by Wojciech Włodarczyk, was published in Paris in 1986 (

Włodarczyk 1986). A year later, already in Poland, Waldemar Baraniewski published an article analysing the ideological side of the doctrine of socialist realism (

Baraniewski 1987). The same author later presented the socialist realist architecture of the Polish capital (

Baraniewski 1996,

2004), with particular emphasis on the sculptural decoration of the Palace of Culture and Science (

Baraniewski 2005). The only review publication on monumental sculptures is the book published in 2015 and entitled “Monuments of gratitude to the Red Army in the People’s Republic of Poland and in the Third Polish Republic”, in which the author, Dominika Czarnecka, presents the history of construction and further history of selected monuments built in praise of the “Soviet Liberation Army” (

Czarnecka 2015). However, this work focused on historical and propaganda issues, leaving aesthetic aspects aside. The English-language literature on Polish monumental sculpture from the socialist realism period basically features one author only, Kasia Murawska-Muthesius, who presented twice a discussion on the ultimately unrealized monument to the victims of the Auschwitz Nazi concentration camp (

Murawska-Muthesius 2002,

2003). In 2010 Ewa Ochman analysed the role of “gratitude to the Red Army” in the process of rebuilding the national identity of Poles after the political breakthrough of 1989 (

Ochman 2010). This year, together with Joanna Majczyk I present thus-far unknown facts about the flagship sculptural implementation of socialist realism, the Silesian Insurgents Monument at the top of the St. Anne Mountain (

Tomaszewicz and Majczyk 2021).

The following paper, therefore, complements the existing literature with issues concerning the link between the ideological and aesthetic aspects of the most important sculpture works in Poland during the socialist realism period and their Soviet models. In addition, an attempt was made to depict other sources of inspiration for Polish sculptors, even those carefully hidden or unintentional.

2. The Soviet Union. “A Monumental Propaganda Plan” and First Sculptural Realization

In the Leninian vision of the socialist world, art, and sculpture specifically, was assigned the role of a tool for shaping a new society. In early spring 1918, Lenin announced the “Monumental propaganda plan”, which was a program of using art and artists to promote the ideals of the Bolshevik revolution. Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky, first People’s Commissioner for Education, mentioned that when drafting the plan, Lenin was inspired Thomas Campanelli’s “The City of Sun”, where the developments of an ideal city were decorated with frescoes illustrating the latest scientific achievements (

Луначарский 1968, p. 198). Campanella treated building façades as drawing boards that would allow children to unintentionally learn “easily and as if for pleasure” (

Луначарский 1968, p. 198). Lenin decided to use similar tools to “immerse” the society in the ideas of the new order, to surround it with slogans for support of the emerging communism and the images of the revolution fathers. The “Monumental Propaganda Plan” took effect in April 1918 when the People’s Commissioners Council adopted a decree “On the demolition of the monuments erected to the tsar and their servants and the creation of monuments to the Russian Socialist Revolution” (

Декрет No 416 1918). A decree was issued to set up a special committee, whose task was not only to identify monuments planned for demolition but also to “mobilize the artistic forces and organize a wide-scope competition for the design of monuments commemorating the great days of the Russian socialist revolution” (

Декрет No 416 1918, point 3). It was assumed that the first “models of new monuments will be presented to the masses for judgment” (

Луначарский 1968, p. 198) as early as on 1 May 1918, the Labour Day. In practice, however, the decree proved much more difficult to implement than to be merely issued, since no law enforcement mechanisms were developed, not only related to organizational issues but more importantly to financial ones. The People’s Education Commissariat provided “artists with full freedom in expressing the idea of a monument” (

Шалаева 2014, p. 31), which was a demonstration of the lack of vision for the new art rather than trust in the sculptor. Initially, it was not clear who should be commemorated, but in August 1918, the People’s Commissioners Council approved a list of 66 people, as “suggestions to erect monuments to in Moscow and other cities in the Soviet Russia” (

Худoжественная 2010, pp. 54–55). These include not only the heroes of the Bolshevik revolution, but also Spartakus, Henri de Saint-Simone, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Alexander Pushkin, and even Frédéric Chopin, the Polish composer and pianist. These apparently incoherent sets of names, which in the opinion of the policymakers, embodied the history of the fight of the poor and oppressed for their rights and freedoms, were supposed to be the basis for the “founding” myth of the Soviet state. The semiotic understanding of the individual involved in this case is an attempt to find threads that would link the past with the present. As Vladimir Maksimovich Fritsche, a literary critic and at the same time one of the People’s Commissioners of the Moscow City Council, explained for the press the listed persons were the “Pantheon of International Culture”, the “Pantheon of immortality” (

Фриче 1918). According to Fritsche’s words, the monuments to the chosen celebrities should be arranged in the city structure in a specific order, creating a linear historical and cultural space. “Wherever a citizen of the Soviet Republic goes, wherever his or her sight falls,” wrote Fritsche, “he or she would be surrounded by memories of the heroic past, heroic people, varying not only in epochs but also in nations, thus instilling the feelings of heroism in his or her soul” (

Фриче 1918).

In the first year of the people’s power, Lenin supervised the implementation of the “Monumental propaganda plan” in person and, despite the telegram to Lunaczarsky, in which the revolution leader expressed his indignation that “nothing has been done for months (…) and neither busts of Marx nor propaganda inscriptions can be found in the streets” and further requested the “names of all those responsible for it” to “be able to bring them to court” (

Лeнин 1918), first monument, a plaster bust of Alexander Nikolayevich Radishchev, a Russian Enlightenment philosopher (author: L.W. Sherwood) was unveiled in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) at the end of September 1918. Further monuments appeared in the Soviet cities on the occasion of the anniversary of the October revolution. Among others, a monument to the Soviet Constitution was unveiled in Moscow at that time, which was located on the Soviet Square (now Twerski Square), in place of Mikhail Skobelev’s sculpture, a general and hero of the Russian-Turkish war (1877–1878). The new monument was designed by architect Dimitry Osipov in the form of a three-sided obelisk of 26 meters in height, located on a tall plinth that acts as a tribune with a round speaker balcony (

Figure 1a). The plinth was decorated with bow panels, which were planned to be filled with bronze plates with quotations from the new Bolshevik Constitution. At the time of unveiling, the monument was not completed. There were no boards and a full-bodied allegory of Freedom, which was supposed to decorate the obelisk, while at the same time adding to its ideological content. Finally, the sculpture, the work of Nikolay Andreyevich Andreyev, made of concrete “refined” with marble aggregate, was unveiled in 1919. The artist adapted both the size of the figure and its forms, which were quite clearly associated with the Hellenistic Winged Victory of Samothrace, to the character of the obelisk, understood as the essential elements of the monument. The target boards with engraved pages of the constitution were placed in the tribune plates in 1922. The first monument implemented out under the “Monumental propaganda plan” displayed a certain gap between the declared idea of “art for the people” and creative practice, in which references to Greek and Italian classicism prevailed. Already in 1920, Nikolay Nikolaevich Punin, an art critic, proved that a sculpture inspired by ancient art and the idea of making monuments to the heroes of the revolution is not a “completely Communist idea”. Communism should not “stir up and cultivate individual heroism”, because “the heroic understanding of history is forever gone now” (

Пyнин [1921] 1994, p. 14). Punin critically evaluated the monuments made as part of the implementation of the “Monumental propaganda plan”. He wrote that “they are very clumsy, shapeless, aesthetically unpleasing. There is nothing to say about them—it is below any standards” (

Пyнин [1921] 1994, p. 14). This criticism seems to be confirmed by the preserved photographs of one of the first commemorations of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels unveiled at Moscow’s Revolution Square by Lenin himself. The author of the monument, S.A. Mezentsev, placed the main socialism ideologists side by side on a plinth designed in the form of a tribune, but Marx’s and Engels’ figures were rescaled and thus distorted by incorrect proportions of the various parts of their bodies (

Figure 1b).

Nikolay Nikolaevich Punin called for the abandonment of figurative monuments in favour of geometric forms created by a synthesis of sculpture, architecture, and painting. The critic believed that the winning ideals of the Bolshevik revolution allowed for breaking with all the former traditions and thus he pointed to the designed monument to the Communist International of Vladimir Yevgrafovich Tatlin as an example of a modern monument, in which the artist combined—according to Punin—“a purely creative form with a utilitarian form” (

Пyнин [1921] 1994, p. 17). The “Tatlin Tower” concept emerged in 1919 as part of the Leninian “Monumental propaganda Plan” and assumed the erection of a 400-meter-high steel structure consisting of two inclined metal spirals supporting three movable and completely glazed rooms. The constructivist Tatlin’s design was not scheduled for implementation, and the basic allegation made not only towards this work, but also other avant-garde artistic works, related, apart from masses’ lack of understanding of their intentions, the alleged disregard of the urban context. The sculpture as “social artwork” was supposed to be visible and located in the urban square, which “socialism restored with the role they played in Greece and Italy as arenas for public life” (

Алфаких 2018, p. 85).

3. The Soviet Union. Monuments to National Heroes

Discussion on “heartlessness and atavism” (

Пyнин [1921] 1994, p. 15) of figurative sculpture ended as soon as five days after Lenin’s death. During the Second USSR Soviet Congress, which took place on 26 January 1924, a resolution was taken on the erection of monuments to the revolutionary leaders, and a national competition was organized for the best sculpture portrait and image of Lenin.

Realistic works “humanizing” the leader were expected as proven by reviews published in the press. In one of the “Art for the working people” newspapers, the design presented by Isaac Abramovich Mendelevich was positively assessed. It represented the full-bodied, naturalistic figure of Lenin in an informal posture way with his right hand held in the trouser pocket and the left hand propped against a fragment of the lectern (

Figure 2a). As an anonymous critic wrote, Mendelevich did not use “the existing Lenin’s photographs, but the takes of his face and silhouette from cinema films. This led the artist to the concept of a living, honest and intimate portrait, uncontaminated by an act of “posing” and capturing not only the head, but also the entire silhouette, interpreted with neither pomposity nor vulgar haughtiness” (

B.И. Ленин 1924, p. 19). Mendelevich’s monument was realized in Ufa and then became a recurring pattern in other cities in the Soviet Union. At the same time, there was a tendency to sacralise the memory of Lenin and to make his commemorations monumental. Apart from erecting the mausoleum in Moscow, which houses the embalmed corpse of first Soviet Russia’s leader, attempts have been made to turn Lenin’s images into urban visual dominates. The most characteristic example of the “deification” of the revolution leader included the competition and then tender for the design of Moscow’s Palace of the Soviets which was developed in 1931–1934 by Boris Mihailovich Iofan. Initially, the building, conceived as a people’s forum, was designed in stepped forms of a cylindrical tower crowned with the status of a “liberated proletarian”. In the meantime, it was recognized that the Palace of the Soviets should serve as a monument to the “leader of humanity, the great Lenin”, thus in subsequent versions of the design, the building gradually became higher and turned into a kind of gigantic plinth carrying a full-bodied silhouette of the revolution leader. While the 17-meter “proletarian” accounted for about 1/16 of the height of the whole building, in the final concept the Lenin’s statues reached a height of 100 meters which translated into almost one-fourth of the height of the building (

Хмельницкий 2006, p. 117).

The Palace of the Soviets was supposed to be an example of a new type of building in which architecture and sculpture merged into “an inseparable whole, a single, ideologically saturated artistic image” (

Алфаких 2018, p. 93). The radically monumentalized monument to the first leader was designed by Sergei Dmitrievich Merkurov as the father of the nation “blessing” Moscow and symbolically dominating over Soviet Russia, and, implicitly, over the world (

Figure 2b). Merkurov specialized in monumental sculpture and authored many memoirs of not only Lenin but also Stalin, among them the most famous architectural and sculptural ensemble i.e., the monuments to both leaders placed on opposite sides of the Moscow Canal on the outskirts of Dubno. The giant statues of Lenin and Stalin erected between 1935 and 1937, thus still during Stalin’s lifetime, embodied the “winning ideas of the revolution” symbolically dominating the tamed nature.

In the end, the Palace of the Soviet’s was not, of course, built, but Iofan realized his vision of the synthesis of architecture and sculpture in the Soviet Union Pavilion design at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1937 (

Figure 3a). The architect won a national competition with his proposal to erect along the Loire an elongated of a “speedy ship” towering on the front side and decorated with a giant two-silhouette sculpture group representing a worker and a Kolkhoz woman crossing sickle and hammer over their heads (

Figure 3b). The silhouette has been refined and carved by Vera Ignatievna Mukhina, a graduate from Emile Antoine Bourdelle’s studio, who actively participated in the implementation of the Leninian “Monumental propaganda plan”. “When designing the pavilion, I immediately felt that the (sculpture) group should express not the character of the personality, but the dynamics of our epoch, the creative impulse that I see everywhere in our country and that is so close to me” (

Bopoнoв 1989, p. 140). The silhouettes of “ordinary people” created by the sculptor were seen as “strong, energetic and beautiful” and their movement was meant to symbolize the “uninterrupted development of the young Soviet state”. Mukhina assumed that “monumental art cannot be mundane, earthly, it is an art of great, the lofty, heroic feelings and great images” (

Muchina 1952, p. 34) and her Worker and the Kolhoz Woman became a leading work of socialist realism.

Socialist realism as a new creative method was proclaimed in 1934 by Maxim Gorky at the Congress of Soviet Writers in Moscow when the principle was adopted that the literary work should have a realistic form and a socialist content, consistent with the ideas of Marxism-Leninism. Socialist realism was soon extended to all areas of art, and after the end of World War 2, it became a valid creative method in those countries of Central and Eastern Europe that were subordinated to the political and economic power of the Soviet Union.

4. Poland. Socialist Realism and Monuments before Its Introduction

In Poland, socialist realism was officially adopted in 1949, which meant that, as in the Soviet Union, state authorities became the only “patron” of artists who were forced to associate in trade unions and to abandon their creative freedom. Still, in January 1948, the press wrote that “only a free and fully responsible artist will be able to cope with the tasks that s/he has been faced with in Poland’s new social and cultural reality”, but right after it added that “a free artist is the one who deliberately incorporates his or her work into the progressive trend of his time” (

Deklaracja 1948, p. 5). Artists who wanted to remain independent could neither count on public orders, nor present their works on trade union reviews and exhibitions, nor were they allowed to participate in art competitions. The state authorities financed fees of the competition participants as well as the possible realization of selected works, but in return, they expected the artists to pursue specific subjects and apply imposed design style of socialist realism.

Before the introduction of the new creative method, discussions were launched on the reconstruction of monuments destroyed during the war, and the first attempts were made to build new monuments, mainly to commemorate the dead.

In 1947, the construction of the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes began. It was located in the place of the first fights of Jewish rebels against the Nazi Warsaw ghetto uprising. The monument, designed by the sculptor Natan Rapaport in collaboration with the architect Leon Marek Suzin, was given the form of a wall fragment with a trapezium cross-section, symbolizing the walls of the ghetto (

Figure 4a). The stone wall was set on a low platform and decorated with bronze reliefs; on the western side representing the heroic revolutionary impulse of the ghetto’s inhabitants (

Figure 4b), on the eastern side an illustration of the martyrdom of the Jews driven to death. In the formal layer, the wall acted as a kind of “passe-partout” for the relief-sculptured parts of the memorial, which varied not only by material, but also by texture, expression, and light-shadow play. As Jadwiga Jarnuszkiewiczowa wrote in 1948: “in the frontal sculpture action is manifested with a dynamics of diverse directions, in the swirling forms of strained muscles, in the anxiety of a variable virtue”, while in the relief in the eastern plane of the memorial features a static composition of a figure expressing “the passiveness of people who deprived of all action power” (

Jarnuszkiewiczowa 1948, pp. 35–36).

The first opportunity for a wider presentation of the latest sculpture achievements presented itself at the Exhibition of the Recovered Territories, which took place in 1948 in Wrocław, the largest city of the so-called Western Territories, which was joined to post-war Poland based on the provisions of the Yalta Conference. The exhibition, known in the press as the “Olympic Games of Polish Architects and Visual Artists” (

WZO 1948, p. 1), was clearly propaganda-oriented, and it aimed to confirm the inclusion of the new territories in Poland and to demonstrate the effectiveness of socialism in the development of industry and the reconstruction of the state. Among the sculpture creations, the works of the most important Polish artists were exhibited, especially by Xawery Dunikowski and his students. Due to his pre-war achievements, Dunikowski remained largely independent, although he—what should be emphasized—supported the introduction of socialism in Poland. At the Exhibition of the Recovered Territories, Dunikowski presented Workers’ Head and four allegoric sculptures showing a miner, a steelworker, a farmer, and a Silesian woman with a child, which were planned as elements decorating the Silesian Insurgents Monument at the top of the St. Anne Mountain (

Tomaszewicz and Majczyk 2021, Figure 6b, p. 10). While the four twin sculptures forming part of a larger architectural project were close to Cubism, the Worker’s Head responded to the realist mainstream and became a kind of “announcement” of the upcoming changes in art (

Figure 5a). The artist himself mentioned that in his composition he wanted to “depict a head typical of a Polish worker”. As he said: “I wanted his mental expression to be clear, adequate to every person working in Poland” (

Artysta 1949, p. 1). The themes of Dunikowski’s work, correct from the point of view of later socialist realism ideologists, ennobled the working people, while at the same time identifying the key professions in the economic development of the country.

Since the beginning of 1949, conferences and meetings of the “people of culture and art” have taken place in various locations all around Poland, during which representatives of the ruling Polish United Workers’ Party presented the assumptions of socialist realism and explained why contemporary artistic life should—in their view—be subordinated to this method. These congresses were much “directed” with such mandatory elements as speeches of representatives of the Ministry of Culture and Art, supporters of realism, followed by debates of enthusiasts and opponents of the new doctrine. Often during such conferences, new trade union authorities were elected, obviously sympathising with the party. Congresses of painters, sculptors, and art theorists were organized twice: in February and June 1949. The first of these meetings, organised in Nieborów, did not bring significant decisions on the future of Polish visual arts as it was rather a consultation intended to prepare the ground for the planned changes. Four months later, in Katowice, these changes were approved, recognizing socialist realism as a doctrine of Polish art, which was subsequently entered in the statute of the Union of Polish Visual Artists. Socialist realism was meant to be in opposition to naturalism and was defined as a “formation method based on the philosophy of historical materialism” (

Krajewski 1949, p. 138). Naturalism was considered as a mistake not only artistically, but ideologically. It was an error consisting of “finding a starting point in the reactionary and fascist schools of the last half-century, rather than in the great traditions of progressive periods, that is to say, first and foremost, in the tradition of Renaissance, Enlightenment and the tradition of critical realism” (

Sokorski 1953, p. 10). In line with the slogans of socialist humanism, the artists’ attention should be focused on depicting the proletariat as a social avant-garde that paves the way for the liberation of all humanity. The socialist content was also seen in “pictures of nature”, but only when it was “tamed, learned and transformed by man” (

Juon 1950, p. 28). The paradigms of socialist realism included: absolute cohesion of content and the resulting form of art, ideological commitment “both constituting the initial stage of creative work and its ultimate aim”, subsidiarity of artists toward “folk masses”, the “elimination of the opposition between the artist and the recipient, between talents and the world view”. The artists were intended to “present phenomena in a universal way” using “a simple and comprehensible visual language” and to “create a great and organic” realistic art “using the best Russian traditions and classical art of humanity” (

Juon 1950, p. 28). It was assumed that the national character of socialist realism would be the essential characteristic of the art and that “new artistic values” were intended to create, as stated in the press, “the colour scheme of local life and nature, the local human type, clothing, richness of architecture and ornaments, uniqueness of style, forms and colours of local life” (

Juon 1950, p. 28).

In Poland it was acknowledged that “national art is limited exclusively to 19th-century painting and folk art”, thus rejecting the art of the inter-war period. The art of socialist realism, in its turn, was defined as the one that would “actively participate in shaping the psyche of the nation and express the creative taking place in our lives” (

Krajewski 1949, p. 137). Dunikowski himself wrote that “realism corresponds to the concept of revolution. It consists in showing in the work of art the truth about the life of a given epoch. The artist moved a new idea provokes a revolution, creates a new form in harmony with time” (

Dunikowski 1955, p. 3).

5. Poland. Socialist Realism and Its First Sculpture Realizations

The earliest test of the effectiveness of the implementation of the new creative method was the First Polish Exhibition of Visual Arts organized in 1950 at the National Museum in Warsaw. The exhibition was “the first mass review of the effort made by our artists to illustrate the revolutionary changes that took place in the reborn nation after the liberation from fascist occupation” (

I Ogólnopolska 1950, p. 11). The exhibition was perceived as “the closure of the period of influence of bourgeois colourism and modernism ideologies on our art” (

Wróblewski 1950, p. 5). Almost 400 artists participated in the first post-war visual art exhibition which included 629 works, out of which 119 were sculptures (

Komarnicki 1950, p. 10). Numerous summaries of the exhibition stressed the domination of “humanistic” topics as the artists exhibited a great affinity to portraying “a working man overcome by work a heroism, a man fighting for human dignity, a man fighting for peace and a man building a just social system” (

Komarnicki 1950, p. 11). Such works also proved award-winning. The sculpture of Alfred Wisniewski, showing a Worker with a rifle “fighting for freedom and social justice” was judged exemplary (

Wróblewski 1950, p. 5) (

Figure 5b). The exhibition also includes a fragment of one of the first monumental compositions, the monument to the Polish-Soviet Brotherhood designed by Marian Wnuk, and then realized at the central point of modernist Gdynia. The monument consisted of two parts: a wide, chunky column and a full-bodied silhouette of a girl with a banner set on it (

Figure 6a). In the upper part of the column, the artist placed a relief friez illustrating “the brotherhood of both nations (Soviet and Polish)”, at the same time “depicting the essence, purpose, and nature of the peaceful joint struggle in the images of reconstruction, work, and family life, based on mutual friendship shown by greeting a Soviet soldier” (

Jarnuszkiewiczowa 1953, p. 58).

Wnuk’s monument was part of a collection labelled “gratitude”, which was one of the elements of the political propaganda by the socialist Polish authorities. Forced and ideologized “gratitude” was expressed in artistic performances from the subordinate position towards the Soviet Union and most frequently depicted in the form of soldiers of “brethren nations” either fighting together or shaking hands or returning from the front line and welcomed by “grateful” civilians. It is estimated that about five hundred “gratitude” monuments were erected in Poland. An example of a typical depiction of this theme is the Monument of Gratitude to the Red Army constructed in 1951 in Legnica, a small town in the Recovered Territories, where the North Group of the Soviet Army was stationed until 1993. The Monument, designed by Józef Gazy, presented three people: a Soviet and a Polish soldier shaking hands and the little girl sitting on the arm of one of them (

Figure 6b). As the author explained: “the Soviet soldier, by shaking hand of the Polish soldier, passes on the independence of the Polish state to him. The Polish soldier expresses his gratitude and friendship. A child that he holds on his arm, that props her hand against the shoulder of the Soviet soldier is a symbol of the young generation saved from extermination” (

Czarnecka 2015, p. 274). The group of sculptures was set on a rectangular plinth, which included the inscription “Legnica Community to the heroic Soviet Army” and two reliefs: one showing the seated silhouettes of a farmer and a worker, and the other showing a woman surrounded by a group of children. The symbolism of both depictions was more than clear: the new Poland built based on the “worker-peasant alliance” was supposed to be a safe place to live in.

Forms of monuments of “gratitude” evolved from individual sculpture elements, merely serving as an ornamental detail in a defined urban space, to extensive architectural and sculpture compositions serving as the basis for larger urban planning. The monument-detail includes the aforementioned column by Marian Wnuk, or soldiers with a child by Józef Gazy, whereas the Cemetery–Mausoleum of the Soviet Army Soldiers in Warsaw can serve as an example of the monumental architectural and sculptural ensemble. The idea of commemorating soldiers killed in the fight for the capital of Poland appeared as early as 1946, when a competition for the design of a monument linked to the Mausoleum was announced, where symbolic urns with soil from the most famous battlefields would be placed. The competition regulations stated that “the idea of brotherhood in arms with the Red Army should be stressed”, but the main goal of the monument was “to celebrate the victory over the Nazi Germany” (

Konkurs 1947, p. 15). The plan was to place the monument in the Ujazdowski Park, which in September 1939 became a place of burial for those people who died during the defence of Warsaw. The first prize in the competition was awarded to the work of Bohdan Lachert, a modernist architect who worked with Jan Knohe and Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz, a sculptor. The designers proposed to erect a mausoleum in the form of a semi-circular ramp that was formed step-wise and crowned with a Nike figure (

Figure 7a). Not only, as required by competition rules, did the ramp delimit the square that was connected in space with a street forming one of the park’s borders, but it could double as stands for public events. As the “friendship” with the Soviet Union tightened, the novel form of the monument became increasingly unsuitable and too small for a monument commemorating the “brotherhood of arms”. In 1949, a decision was taken to relocate the monument and connect it to the cemetery of Soviet soldiers. The new project was entrusted to the same architects and sculptor, joined by Stanislaw Lisowski, another sculptor, and Władysław Niemirski, a greenery designer. The artists were supposed to develop a plot on the outskirts of Warsaw’s city centre, which they converted into a landscape park. The composition was based on three major axes with a broad central alley running led through three terraces and ending with a granite obelisk of 21 meters. The four-sided obelisk was decorated with an inscription saying: “In eternal glory of the heroic soldiers of the invincible Soviet Army, dead in the fight with the Nazi invader to liberate Poland and our capital of Warsaw”, and in the upper part it features relief-sculptured stars, symbols of communism. In front of the obelisks, a trapezoidal square was drawn with two sculpture groups placed on tall plinths in the front. The first group presented, as written in the press, “a soldier lifting and supporting his wounded companion who, in his very last effort, tries to throw a grenade to the enemy”, while in the second group the soldier held the “head of a dying colleague who placed his hand on his rifle as if to transfer his enthusiasm for the battle” (

Linke 1950, p. 28) (

Figure 7b). In the composition of both monuments references to the Pietà tradition can be seen, and how the characters are presented makes a reference to classicism. However, numerous comments recognized that the sculptures were “made with a great sense of seriousness” and were “realistically implemented” (

Linke 1950, p. 28). The mausoleum sculpture programme was supplemented by quasi-sarcophagi decorated with bas-reliefs representing scenes of the greeting of Soviet soldiers and inscriptions: “glory to the heroes of the Soviet Army who brought Poland freedom and peace”, which was located at the beginning of the avenue, right next to the entrance square in the cemetery. Along the side axes, parallel to the sides of the trapezoidal square, the plots for the dead were designed and covered with grass and flowers. Similar monumental necropolae, although usually with a more modest sculptural program, were built in every larger city in Poland.

6. Poland. Socialist Realism and Portrait Monuments

A separate group of monuments designed and realized during the socialist realist period included portraits of national heroes, revolution leaders, and people representing the “world of labour”, most often folk people, workers, and peasants. Even before the introduction of the new creative method, many Polish cities planned to build monuments to personalities most significant for national culture, especially to Adam Mickiewicz, who was perceived as the “bard of the Polish commoners”. (

Zieliński 1946), and Frederic Chopin, “the piano poet”, the most important composer of Romanticism.

Apart from historical figures and attempts to commemorate them in traditional figurative forms, monuments to “new heroes” were also designed as a keystone of the founding myth of People’s Poland. Karol “Walter” Świerczewski, general of the Red Army and the Polish Army, and at the same time a communist activist, shot dead in 1947 by members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, was one of such idols. The day after the death of the “steadfast revolutionary”, at a meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, the following decisions were taken: “to propose to the Government a resolution to build a monument” to Świerczewski (

Protokół 1947). The monument was planned to be erected in Warsaw, but it seems that the above-mentioned resolution became the basis for many local initiatives to commemorate gen. Walter. For example, Wrocław intended to build a mausoleum to Świerczewski, which was to constitute the “main ideological political and sculptural accent” of the newly designed academic district (

Program 1951, p. 2). The concept of the monument together with the development design of the main, monumental traffic axis of the new part of the city would be obtained in a competition, announced in 1951. The competition conditions stipulated that the monument to “the hero of the fight for socialism and freedom of the Polish nation, general Walter-Świerczewski” must not take on “abstract forms, e.g., of an obelisk”, and its pedestal should be “synchronised with the tribune parade audience” (

Załącznik 1951). Already two years after the official introduction of socialist realism to art, an obelisk became an “abstract form”, which is why most of the works submitted to the competition proposed a figurative monument, and one work, by Tadeusz Teodorowicz-Todorowski featured a mausoleum (

Figure 8a). The symbolic Świerczewski’s tomb was designed as a cuboidal pavilion covered with a dome, preceded by a portico, and surrounded by pylons topped with sculptures placed on low quadrilateral bases. The mausoleum, designed in raw classicist style, was placed in the gigantic “defilade” square, whose borders were accentuated with sculptural groups elevated above the square floor level on massive cuboid plinths. The concept presented by Teodorowicz-Todorowski remained unrealised, but it is worth mentioning that the architect was the author of a small sculpture of a bricklayer woman erected in Nowe Tychy, the city which was one of the flagship construction sites of socialist realism. Todorowski’s monument depicted a female worker, attired in a dress and apron, holding a trowel in one hand and in the other a model of a residential building, similar to those that the communist authorities built for “the labouring people” (

Figure 8b). While the subject matter of the sculpture, a woman creating a new reality on an equal footing with men, was well in line with socialist propaganda, its forms only seemingly conformed to the assumptions of socialist realism. In the Tychy bricklayer woman, the new ideological content was superimposed on the pattern drawn from sacral art, namely the image of St. Hedwig of Silesia bringing the image of the church to the believers. Today, it is difficult to say whether this was the intention of the originator of the monument and its maker, the sculptor Stanisław Marcinów, or whether the effect was unintentional as, after all, there was no place for religion in a socialist society.

Similar to the Soviet Union, a separate group of monuments consisted of representations of revolution leaders, mostly Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. The first sculpture of the leader of the Bolshevik party was placed in Poronin, next to the Lenin Museum organized in the building of a former inn that Lenin often visited in 1913–1914, when he lived in Biały Dunajec in Podhale. The sculpture, unveiled in 1950, was made in the Soviet Union according to a design by Dmitriy Petrovich Schwartz, a Russian artist who provided a kind of template for a “correct” depiction of Lenin (

Figure 9a). The conservative design, depicting the figure of the leader in a slight lunge, with his coat slung over his shoulder, confidently looking off into the distance, was probably intended to become a model which would serve as an inspiration for Polish artists. If this was the aim of presenting Schwarz’s sculpture to Poland, then it was achieved, and as early as in 1951, at the Second National Exhibition of Fine Arts, Marian Wnuk presented his vision of Lenin’s silhouette (

Figure 9b), which was deemed by critics as “an accurate realistic interpretation of the portrait of a socialist hero”. (

Jarnuszkiewiczowa 1953, p. 61). “The artist was able to recreate an accurate portrait of Lenin, in a true and yet synthetic and monumental pose. The audience is subjected to the extraordinary power of character, the unyielding will, the all-embracing intellect of this man who is for us the embodiment, the symbol of the Revolution. (...) Although Lenin’s face does not express any agitation, the impression of meaning is irresistible. In simple terms, it seems to us that we are listening to a speech, a great, shocking oration by Lenin, in which the inexorable logic of his arguments goes hand in hand with the fervour of the feelings he expresses”. (

Jakimowicz 1952, p. 55). Hagiographical descriptions of Wnuk’s sculpture would not change the fact that it was a work intended for viewing in an enclosed space; the composition of the silhouette, the way it was cut at knee height with a base block, basically made it impossible to place the figure as a free-standing monument in the open city space. One of the few realised monuments to the revolution leaders, Lenin and Stalin, was erected in 1955 in Krakow, in Strzelecki Park. The monument, depicting the leaders sitting on a bench and immersed in conversation, was a “gift” from Baku, the largest city in Azerbaijan, and was, therefore, neither designed nor created by Polish artists. After Stalin’s death, a great number of concepts for commemorating the USSR leader were put forward, including designs by Ksawery Dunikowski, Marian Wnuk, and Franciszek Strynkiewicz. The above-mentioned artists were invited by the state authorities to take part in a competition for the design of a monument to the Generalissimo, which was to be erected on the square at the entrance to the Palace of Culture and Science, another USSR’s gift, this time to Warsaw.

7. Poland. Socialist Realism and Sculpture in Relation to Architecture

The Palace of Culture and Science was designed by Soviet architect Lev Vladimirovich Rudnev, modelled upon Moscow skyscrapers, which were in turn inspired by American skyscrapers of the interwar period. However, while the latter were mainly built in the art-deco style, the Soviet skyscrapers followed socialist realism stylistics, enriched with “national” motifs in accordance with the Leninist slogan on architecture that is “national in its form and socialist in its content”. The Warsaw Palace of Culture and Science was thus decorated with elements mainly stemming from Polish Renaissance buildings such as the Castle in Krasiczyn or the Krakow Cloth Hall. As a work of propaganda, the skyscraper was also intended to serve as a frame for carefully selected works of art, mainly sculptures. It was initially planned to display twenty sculptures in niches and ten silhouettes sitting at the entrances and a decision was made that Polish artists would make monuments to Stalin, Adam Mickiewicz, and Nicolaus Copernicus, and a sculpture symbolizing Polish–Soviet friendship, whereas other sculptures, the allegories of “art, theatre, science, the friendship of nations, the struggle for peace” would be made by Soviet artists (

Baraniewski 2005, p. 59). The afore-mentioned design competition for a monument to Stalin remained unsettled as in view of the jurors “the authors presented J. Stalin is too one-sided, for example, only as a leader”, whereas “the sculpture should reflect the multifaceted character of a leader, a thinker and a friend of Poland” (

Baraniewski 2005, p. 66). The sole monument model that survived till today is the one created by Xawery Dunikowski, which depicted Stalin in a standing position, dressed in a long coat. The USSR leader propped one hand at his side and held the other one, clenched in a fist, at his breast. Despite the unquestionably monumental silhouette of Stalin and its artistic originality, the project remained unimplemented as “the concept itself was too risky” (

Baraniewski 2005, p. 66). Finally, as designed by sculptors, two “seated” characters were sculpted, one commemorating Nicolaus Copernicus by Ludwika Nitschowa and one commemorating Adam Mickiewicz created by Stanislaw Horno-Popławski (

Figure 10a) and a monument to Polish-Soviet friendship carved by Alina Szapocznikow (

Figure 10b) and set in the main hall of the Palace. I was undoubtedly the most interesting Szapocznikow’s work from the artistic point of view; an expressive and realistic study of two male figures clasped by their arms and linked by a jointly held banner.

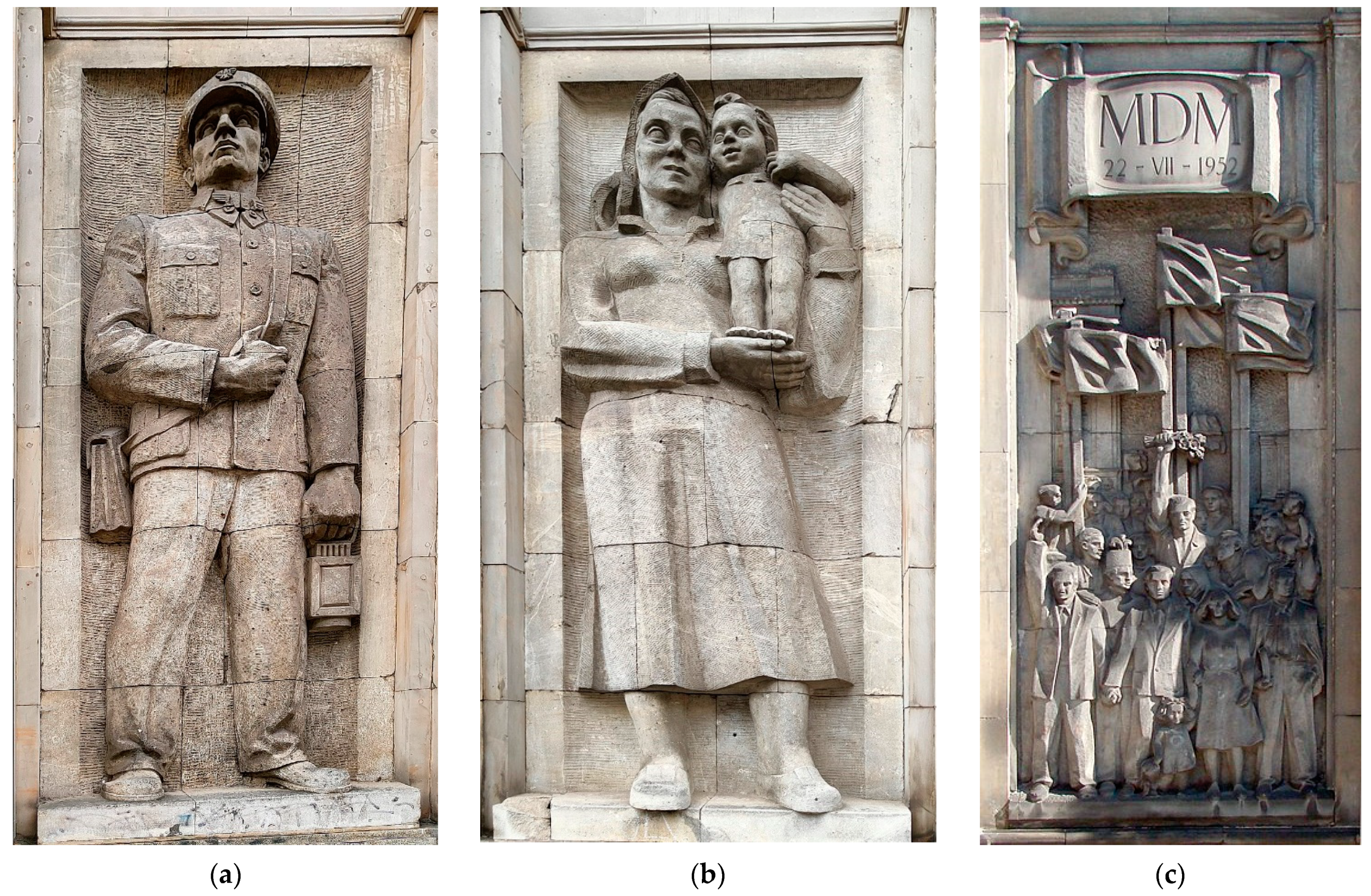

For Polish sculptors, it was not the Palace of Culture and Science that was the largest testing ground, but the Marszałkowska Residential Quarter (MDM), the great urban planning scheme built in the war-ravaged Warsaw in the early 1950s. The new district intended for 45,000 inhabitants was planned to be an example of a “model” socialist housing estate, with good access to services and designed—at least in theory—for the working class. The aim of the project was said to “give some monumental character to the centre of the socialist capital, to properly reflect the humanist nature of the residential area, to create an appropriate climate for social coexistence on a large-city scale”, and therefore the forms of the designed buildings followed the social realism objectives and at the same time, they made “a creative reference to the good national traditions of Warsaw architecture” (

Jankowski et al. 1951, p. 229). It was planned to decorate public spaces with monuments and residential buildings with relief-sculptures and sculpture groups. In 1951, a competition was announced for three monuments, a group of allegorically figure sculptures representing: the “Capital”, “Silesia”, and “Mazovia” as industrial and agricultural centres the most important to the socialist economy. It was planned to locate the sculptures set on tall plinths along one of the boundaries of the Constitution Square, the largest square of the settlement serving as a communication hub and a place for “peaceful demonstrations”. For some unclear reasons, the monuments were never made, and three giant candelabra took their place. However, the sculptural decorations of houses located around the Constitution Square and along Marszałkowska Street, the main communication and composition artery of the Marszałkowska Residential District, were realized. The arcade pillars in residential buildings were decorated with eight semi-plastic sculptures of “representatives of the world of labour”, namely: a teacher with a student and a railwayman (

Figure 11a) by Tadeusz Łodziana, a steelworker and a textile worker designed by Tadeusz Breyer, a bricklayer and a mother with a child (

Figure 11b) by Karol Tchorek, and finally a miner and a farmer sculpted by Józef Gazy. Over the arcaded windows of residential blocks at the Constitution Square, there were relief-sculptures showcasing the history of the project and the construction phase of the Marszałkowska Residential District made by Ludwik Nitschow and Adam Smolan. The punch line of this story is a relief by Franciszek Habdas, entitled “Opening of the MDM”, which shows the crowded, slightly geometric figures, banners, and a cartouche dated 22 July 1952” (

Figure 11c). Multi-figure sculptures by Kazimierz Bienkowski and Józef Gosławski representing the allegories of architecture and visual arts, literature, and music, were placed at composition tops of selected houses. At the time of the opening, the sculptures were already criticized for “conformity and using false stylization” (

Sokorski 1952, p. 10), whereas Zygmunt Skibniewski, an architect and urban planner, even considered that “it would be better to leave these spaces empty instead of realizing all these sculptures in insufficiently good form” (

Dyskusja 1953, p. 14). However, there was quite universal agreement that a synergy of architecture, sculpture, and painting is the right way to further develop socialist art of building. The proposed development did not take place, as it had been hampered by political and technological changes.

8. Conclusions

The socialist realism method in art was abandoned in 1956 as a reaction to the “thaw” initiated by the famous speech by Nikita Khrushchev entitled “The cult of the individual and its consequences”, in which the future leader of the Soviet Union depicted Stalin as a criminal responsible for the extermination of millions of people during the period of “great terror” in the 1930s. In Poland, the “new opening” involved a change of power, and the position of the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers Party was taken by Władysław Gomułka, a communist, but also a political prisoner from 1951–1954. The criticism of artistic achievements was almost immediate, with the monumental art being deemed to have produced “a dead pattern in which the differences between artistic expressions, the individuality of creative ideas, and even the presented subjects and characters are blurred, the lack of creativity and limited artistic imagination are more and more visible in works that seem to draw mechanically from a single established iconography, repeatedly from the same very scarce resource and one and the same convention” (

Jarnuszkiewiczowa 1956, p. 24).

It is difficult not to agree with the afore-cited words of art critics, but Poland, a country with a particularly complex history, had almost no tradition of monumental sculpture. Socialist realism, which gave the art a unique meaning, allowed us to start exploring ways of commemorating historical figures and contemporary events. Obviously, the convention of “apotheosis of a character raised above the crowd, on a high plinth in a representative pose and a representative gesture” prevailed (

Jarnuszkiewiczowa 1956, p. 25), but non-standard, custom solutions were also sought after, of which the “revolutionary creation” of Xawery Dunikowski is undoubtedly an example. Most probably, the subconscious of the “sacralization” of the commemorated figures was the characteristic trait of Polish memorial art. Artists used to refer not only to the forms worked out by Soviet artists but also to the old native art, including people’s and religious art. Without a doubt, in the period of socialist realism, monuments have become desirable elements of the urban space, never before and never later, were sculpture and architecture linked so closely. Financial support to creators and artistic education to talented young people was also provided modelled on Leninian “Monumental propaganda program”. The sculptor family in Poland of the 1950s was small enough that it was unable to cope with larger tasks by itself, such as, for example, making decorations to the Palace of Culture and Science. Educating new staff was, therefore, a priority for the further development of monumental art, which, despite formal changes, did not undergo major ideological transformations until the political breakthrough in 1989.

Once socialist realism was abandoned, the fate of monuments realized at that time varied greatly. Some of them have been preserved, especially those decorating cemeteries, others have been disassembled, including most of the monuments of gratitude to the Red Army, and some have been “improved” by changing their inscriptions or hiding the name of Stalin as it was the case of one of the sculptures adorning the Palace of Culture and Science representing a young man holding a book of works of communist classics with names of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin on the cover. Most of the disassembled monuments have been destroyed and a small part of them are now on display at the Gallery of Socialist Realism Art, which was opened in 1994 in Kozłówka, located in the eastern part of Poland. Socialist realism continues to be treated in Poland as a short-lived episode in art history, an experiment enforced by the political situation. The sculptures that were created at that time are often denied artistic values, as evidenced by the efforts of contemporary politicians to remove from public space the remaining, sometimes outstanding, works of art by successive “de-communization” laws. The fall of the monument is still perceived as a symbol of the fall of the regime that initiated its creation.