Abstract

The church of San Miguel of Almazán (Soria, Spain) houses a twelfth-century antependium ornamented with scenes of Thomas Becket’s martyrdom. Discovered during restoration works in 1936, its origin and its original location are unknown. The aim of this article is twofold—to frame its manufacture chronologically in light of recent research on late-Romanesque sculpture in Castile, and to use this information to discover who commissioned this work: The bishops of Sigüenza, whose diocese included Almazán? The canons of the monastery of Allende Duero built at the foot of Almazán’s town wall? Or, as has always been claimed, the Castilian Monarchs Alfonso VIII and Eleanor of England, who were the chief promoters of the Becket cult in their dominions? Whatever the answer, this relief is one of the earliest examples of Canterbury saint iconography in the Crown of Castile.

1. The Romanesque Frontal of Thomas Becket at the Church of San Miguel of Almazán—Iconography, Style, and Chronology

Almazán is a little town on the banks of the Duero, approximately 35 km south of Soria1. At the northern end of the village, next to the medieval town wall, stands the Romanesque church of San Miguel built in the second half of the twelfth century2. Inside the building, the north chapel in the east end contains a relief displaying one of the earliest examples of Thomas Becket iconography in the Iberian Peninsula3. Carved in sandstone, its proportions and forms suggest that it was created as an antependium to be placed on the front of an altar (Figure 1).4

Figure 1.

Almazán. Church of San Miguel. Frontal of Thomas Becket’s martyrdom.

The Almazán antependium is an oblong stone block with a chamfered edge that serves as a frame. It is approximately 0.8 m in height, 1.20 m in length and 0.29 m in width (measurements from Rodríguez Montañés 2001, 2002, p. 140). Although it is unfortunately damaged, the disfigurement did not hinder its theme being immediately identified as the martyrdom of St Thomas Becket, an attribution which is shared by all who have studied the panel since Gaya Nuño and Ridruejo announced the discovery (Gaya Nuño 1946, p. 194; Ridruejo Gil 1945, pp. 100–13; Sainz Magaña 1984, vol. I, pp. 511 and 522; Taracena and Tudela [1928] 1997, p. 211; Rodríguez Montañés 2001, 2002, pp. 140–142; Galván Freile 2008, pp. 209–10; Guardia Pons 2009, pp. 39–42; 2011, pp. 169–70; Huerta Huerta 2012, p. 52; Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, pp. 79–82; Sánchez Márquez 2020, pp. 94–95 and 2021, pp. 10–11).

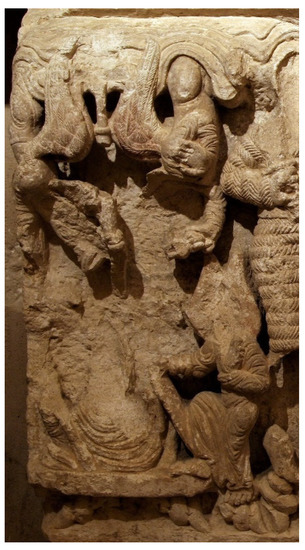

The scene of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s assassination covers most of the stone surface. Four knights, dressed in coats of mail—clearly the nobles identified in the majority of Vitae: Reginald Fitzurse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy and Richard Brito—advance from left to right towards the clergyman, who kneels with his back to the altar and his hands raised at chest height in an attitude that suggests acceptance of his tragic destiny. While the two men at the back still carry their swords on their shoulder and chest, respectively, the two in front adopt a violent stance to carry out the assassination. In a simultaneous attack, the first man is portrayed on the point of beheading Becket with a strike to his throat, while his companion thrusts his sword into Edward Grim’s arm as the latter stands behind Becket holding his crosier and trying to shield the prelate with a gesture (Figure 2). Behind the saint and above the surface of the altar, an angel raises a cloth showing a small head—a symbol of the new martyr’s soul rising to Heaven, in the typical elevatio animae pattern of Romanesque plastic art (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Almazán. Frontal (detail). Murder of Thomas Becket.

Figure 3.

Almazán. Frontal (detail). Elevatio animae.

Trying to ascertain the content of the leftmost third of the composition is a more complex task. Despite the damage, which has obliterated the whole central area of this scene, two angels can be perceived floating down from a sea of clouds and spreading incense over an open grave over which the remains of a shroud spill out. Another angel holds one side of the lid to prevent it falling. Although the details are impossible to discern, again the design is not unusual in contemporary artworks. Indeed, this is one of the most common representations of Christ’s resurrection in Castilian Romanesque, based on the episode of the visitatio sepulchri (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Almazán. Frontal (detail). Resurrection.

Along the bottom of the slab, a pattern of large fleshy leaves curling at the edges and containing pinecones, in a very similar design to the decoration of the cymatia and imposts on the vault capitals, forms the base on which the different scenes stand.

In line with Milagros Guardia’s reading (Guardia Pons 2009, p. 39), the choice of scenes displayed on the frontal aimed to enhance the Canterbury martyr’s holiness by representing a symbolic and visual parallelism between the last moments in the lives of the Becket and Jesus Christ. Although art popularised the notion that St Thomas was attacked while he was officiating mass, this was not the case.5 While it is true that the assault took place in the cathedral, mass was not being celebrated at the time. Consequently, the altar was not a mandatory element in the saint’s iconography but was included to reinforce the sacrilegious nature of the assassination. According to the account of John of Salisbury, there were four traitors, the same number as those mainly responsible for the death sentence of Christ.6 Becket’s blood had been spilt defending the Church in the very place where Christ’s sacrifice on the cross for the salvation of humanity is commemorated in perpetuity. These assassins were therefore portrayed wearing military garb instead of clothes befitting their status as noblemen, thereby linking them to the memory of the Roman soldiers who crucified Jesus and gambled for his robes. Exactly the same impious action committed by the criminals with the Archbishop’s possessions, as can be read a little later in the Vita of the aforementioned biographer7.

This also explains why the virtually obliterated scene on the far left of the panel can only represent the resurrection of Christ—as Guardia correctly inferred (Guardia Pons 2009, p. 42; 2011, p. 119)—while evoking the future resurrection of the martyr, which is anticipated by the vision of his soul being raised to Heaven at the opposite end of the panel: its reception into the Bosom of Abraham as was related by Edward Grim.8

The body language displayed by some of the characters also engages in this interplay of linked identities. The tilt of Becket’s head as he is struck, coupled with the position of his slightly oversized hands over his chest to enhance the expressiveness of the gesture, have a close parallel in the episode of Judas’s kiss which appears in the uppermost archivolt on the façade of the church of Santo Domingo in Soria. In that image, Christ’s head is similarly tilted to receive the traitor’s kiss while he presents one of his—also oversized—hands in an identical open-palmed gesture of acceptance of his imminent fate. One can even observe a certain similarity in the features and long loose hair of the two figures.

Taken as a whole, the iconographic programme displayed on the Almazán stone goes beyond reproducing a hagiographic narrative to conjure up a deep ecclesiastical symbolism which may, perhaps, help identify the person who commissioned the work.

In pointing out the parallels between the Almazán frontal and the Santo Domingo façade, I do not wish to imply that the former was in any way stylistically derived from the latter, although they share other features, such as the layout of the elevatio animae on the frontal, which resembles the scene of Abraham’s Bosom in Santo Domingo, as well as the angel by the sepulchre which also has its counterpart in the Soria façade. Despite a certain family resemblance, the two works have different styles, and their similarities derive from their authors’ shared knowledge of representational models, possibly because the members of both workshops received the same training.

The author of the antependium had the necessary skills to resolve a complex composition competently, incorporating three different episodes—resurrection, martyrdom and elevatio—and including a considerable number of characters. The symbolic nature of the theme required the artist to portray the heaven–earth duality through spatial arrangement on a rectangular surface just over 1 m in length and under 1 m in height. The resulting composition is crowded but not chaotic. The foliage that lines the base of the panel binds the different scenes together without impinging on their individuality. Movement, albeit restrained even in the most violent details, is suggested in all but cinematic fashion, as can be appreciated in the sequential advance of the four assassins. The last man, being the furthest from the target, is walking and as yet has no need to deploy his weapon, so he is shown carrying his sword on his shoulder. The man in front of him is close to meeting the martyr and has begun to lower his sword to the level of his chest. The two in front have reached Becket and Grim and launched their attack brandishing their swords horizontally. Of these two, the man who beheads Becket leans slightly forward, using the momentum of his body to perpetrate the deed. Grim’s attacker has stopped advancing and is shown standing still, facing the viewer to mark the end of the process. Their coats of mail are represented as a finely striped pattern that attests to the sculptor’s close attention to detail, a skill that can also be perceived in the feathery patterns on the angels’ wings (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Almazán. Frontal (detail). The four assassins.

Another interesting resource that evinces the workmanship of the piece can be observed in the right section of the panel, where the scene of Becket’s elevatio animae at the top is compensated by placing the altar table exactly underneath, filling an empty space that would otherwise have felt unbalanced. Thus, the soul does not rise over the martyr’s head but over the liturgical table, while the cloth that frames the head representing the soul appears to be an extension of the saint’s hair in a subtle play of curves and curls, showing the artist’s skillful juggling of compositional resources and symbolic values (Figure 6). Lastly, the figures are stylised, although their heads are slightly undersized in relation to the rest of their bodies. The fabric folds are heavy, flat and sometimes resolved by the addition of simple notches, while the faces that have survived are virtually inexpressive. On balance, the piece was fashioned by a skilled and resourceful artist with good knowledge of his craft, but not by an outstanding member of his profession. Where could he have learned his trade?

Figure 6.

Almazán. Frontal (detail). Altar and elevation animae.

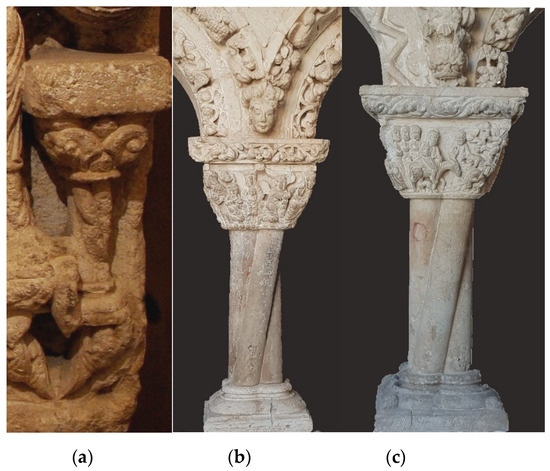

Despite certain formal elements that suggest the influence of the monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, both the sculptural style of the antependium and certain details in the representation of objects and scenes point to an artist trained in the ateliers that had worked on the ornamentation of the chapterhouse at El Burgo de Osma—a link first pointed out by Rodríguez Montañés (2001, 2002), Guardia Pons (2009, p. 49) and Huerta Huerta (2012). Osma is the source of many of the models the Almazán panel is based on: the altar is shaped as a foliated capital supported by a four-strand twisted column, closely resembling the central supports in the windows between the chapterhouse and the cloister gallery at Osma, the left of which even features a small head (Figure 7a–c). The Almazán sculptor only needed to add a cloth carried by angels to turn the decorative head at Osma into a symbolic image of the soul. The foliage patterns are virtually identical to the cymatia of some of the capitals in the chapterhouse. The artist even resorts to Osma to solve an iconographic problem for which no specific models were available: The martyrial scene showing the assassins dressed in coats of mail as they slice heads and pierce limbs with horizontal swords is borrowed from the representation of the Massacre of the Innocents which graces another capital in the chapterhouse. The main variation the artist had to introduce was to exchange the child’s body of one of the victims with the kneeling adult figure of Thomas Becket (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

(a) Almazán. Frontal (detail). Altar. (b) El Burgo de Osma. Chapterhouse. Left window. (c) El Burgo de Osma. Chapterhouse. Right window.

Figure 8.

El Burgo de Osma. Chapterhouse. Capital of the Massacre of the Innocents.

Be that as it may, the Osma sculptors outstripped the author of the Almazán panel in plastic quality. The figures at Osma are more ductile, their gestures more emphatic and their expressions more clearly defined; the textile folds are gentler and drape more naturally over the joints of the figures’ bodies. Osma still reflects the naturalism favoured by the great sculpture workshops active in the late Castilian Romanesque period, whereas Almazán appears to be already on the way to the stereotyped shapes that signalled the dissolution of that style.

Based on the above arguments, if the works at the Osma chapterhouse took place in the 1170s—at any rate, before 1182 according to Boto (Boto Varela 2000, p. 198) or 1170–1189 according to Valdez (Valdez del Álamo 2012, p. 371)—I believe it is feasible to consider the early years of the next decade, 1180–1185 approximately, as the most likely period for the manufacture of the Almazán panel. This considerably narrows down Rodríguez Montañés’ dating in the “last two decades of the twelfth century” (Rodríguez Montañés 2002, p. 143) and Huerta (Huerta Huerta 2012, p. 52).

To conclude this section on a purely iconographic note, it is impossible to determine at this point whether the artist was inspired by a specific model to compose the scene. Possible candidates are two Limousin enamelled caskets decorated with images of the martyrdom and burial of Thomas Becket. 9 One of these is preserved at the monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial (Melero Moneo 2001)—its date of arrival in the Peninsula in the Middle Ages is uncertain—and the other at the Musée National du Moyen-Âge in Paris, where it was relocated from Palencia cathedral (Caudron 2001). It is not easy to detect common features between these and the Almazán antependium on the basis of existing interpretations of their iconography. The reliquaries show two murderers instead of four and they are not dressed in military attire; the scene displayed above the martyrdom is Becket’s body being laid in his tomb rather than his soul rising up to Heaven (other differences in the depiction of these episodes on the caskets may be found in Yarza Luaces 2001, pp. 235–37). Added to this, the enamels are dated to the first few decades of the thirteenth century, and therefore later than the Almazán antependium (Español 2001, p. 89).10

My own working assumption is that the maker of the Almazán panel followed a textual source, perhaps one of the Vitae which had arrived in Castile soon after it was written, a copy of which fell into the hands of the person who sponsored the piece. I understand that the artist relied on common designs used in his artistic circle to arrive at the actual definition of its forms. He only needed to modify general features to obtain the new specific images.11

2. The Queen, the King, and the Bishop—One Artwork, Three Possible Patrons

As Gregoria Cavero has observed, the spread the Becket cult across the different kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula did not deviate substantially from the rest of Europe. Bishops, Augustine canons, Cistercian monks, monarchs and laymen in general played an important part in this process (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, pp. 203–24).

Focusing on the Soria province and, more specifically, on the examples of this cult in the Almazán area, it is not surprising to find a Gradual (c.1230)12 containing a specific office to honour the English saint on his dies natalis in a document from the monastery of Santa María de Huerta13. This abbey was one of the main beneficiaries of Alfonso and Eleanor’s protection, and some of its abbots had developed close relationships with the bishopric of Sigüenza, whose cathedral housed a chapel dedicated to the Canterbury saint since the days of the—possibly Aquitanian—bishop Joscelmo (1168–1178). However, as the Cistercian order—to which this monastery belonged—was one of the most active in the dissemination of the cult of Thomas Becket across medieval Christendom, the codex is likely to have been commissioned by the monks themselves (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, p. 221).

A more complex task is discerning who was behind the initiative to paint the Becketian scenes in the church of San Nicolás in Soria.14 Painted in approximately 1280–1300 in an almost outdated lineal Gothic style, its late presence in the Castilian town has been linked to the enduring memory of the marriage of Alfonso VIII and Eleanor of England, who had strong emotional links with the city;15 hypothesis that I do not share.16 Without any documentary data to support it, I suspect they were commissioned by the prelates of San Pedro in the city of Soria, on the following grounds: First, the geographical proximity between the church of San Nicolás and the canonical house in Soria. Second, the fact that this space housed the cult of two saintly bishops, St Nicolas and St Thomas Becket, who were renowned for their resolute defence of the Church’s values—the dogma of the Trinity after the Council of Nicea for the former case, libertas ecclesiae for the latter.

Turning to the frontal at San Miguel, whose idea was it to commission an antependium representing the martyrdom of the English bishop to be displayed in a church in a border town like Almazán? Was it really Alfonso VIII and Eleanor as it is often stated? Did it arise from a specific event? To answer this question, it would be helpful to know if, for instance, the town had suffered a leprosy epidemic or some such calamity, since Becket was one of the saints to invoke for the healing of skin diseases. Alternatively, it would help to have evidence of a clergyman from the British Isles who might have initiated the project, as was the case in other locations where the Canterbury saint became part of the local visual memory—Terrassa, for instance, where the presence of two canons of English or Anglo-Norman origin, Harvey and Reginald, is attested (Sánchez Márquez 2014, 2018 and 2020, pp. 61–66). Not even the existence of a Premonstratensian monastery in the outskirts of the town is of assistance in this case: The Augustine monks of Santa María Allende Duero would have been the ideal candidates for the task of commissioning and placing the carving in the church, were it not for the forty-year lapse from the manufacture of the frontal to the monastery’s foundation in 1231 (López de Guereño Sanz 1997, vol. II, pp. 545–46).17

As the matter stands, the quality of the workmanship displayed on the Almazán panel, the specific details of its iconographic programme and its early manufacture suggest that it was commissioned by a prominent individual. Discovering the precise identity of this person is a process that needs to take further background considerations into account.

2.1. The Queen—Eleanor of England and the Spread of the Thomas Becket Cult in the Kingdom of Castile

One of the most powerful tools available to royal houses in their efforts to build dynastic legitimacy in the Middle Ages was religious policy, coupled with the extension of the different monarchs’ personal devotions to all strata of society. This identity building process was strongly reinforced in areas where the cult had originated elsewhere or was not supported by local tradition. In the case of Alfonso VIII, the presence of Eleanor, Henry’s II of England daughter in the Castilian court and the spread of the cult of St Thomas Becket gave him an edge he skilfully used to develop his government programme vis à vis his neighbouring rivals.

On 29 December 1170, barely three months into the marriage of Alfonso and Eleanor, Thomas Becket, a former friend and confidant of Henry II, Chancellor of England and, by the end of his life, Archbishop of Canterbury, was assassinated in his own cathedral by four noblemen from the King’s immediate circle. Although Henry always denied responsibility for the incident, Becket’s murder while defending the interests of the Church against the kingdom’s shocked Christendom, and the conviction that the King had instigated the crime quickly spread. Belief in the martyr’s sanctity grew equally fast and he was canonised by Pope Alexander III in 1173, only three years after his death. Henry II was forced to make a public show of repentance in a carefully staged contrition ceremony, with the saint’s tomb in Canterbury Cathedral as a backdrop, on 12 July 1174. As José Manuel Cerda remarks, the situation was theatrically reversed: “The martyr of Canterbury, once a victim of Angevin wrath, became a focus of Angevin piety” (Cerda 2016a, p. 134). Of Henry II’s numerous offspring with Eleanor of Aquitaine, only Henry the Young King, who had been tutored by Thomas Becket between May 1162 and October 1163, accompanied his father in this ordeal. However, it was his three daughters, through their marriage alliances, who undertook a resolute defence of their father’s pious memory, disseminating the cult of the new saint and recently adopted patron of the Plantagenet dynasty in their countries of residence after their weddings. As Ana Rodríguez lucidly points out, “the daughters of Henry II and Eleanor of England played a key role in turning the need to forget into an opportunity to remember” (Rodríguez 2014, pp. 214–15).

Eleanor’s performance in this matter was no different from her sisters’ Matilda, Duchess of Saxony, and Joan, Queen of Sicily (Slocum 1999; Bowie 2014; Lutan-Hassner 2015; Jasperse 2017, 2020; de Beer and Speakman 2021, pp. 93–104. For Castile specifically, see Cerda 2016a, 2018). As far as is known, the Queen’s chancellery only ever issued two documents without the King’s involvement or signature. One of them is a charter issued on 30 April 1179 granting protection to an altar dedicated to the cult of St Thomas Becket in Toledo Cathedral (González 1960, vol. II, pp. 542–43, doc. 324). Founded in 1177, neither the chapel nor the altar were due to the Queen’s initiative, but had been promoted by a Castilian noble couple, Count Nuño Pérez de Lara and his wife Teresa Fernández de Traba, probably on the advice of Willielmus (William), their English chaplain18. However, the extant diploma issued by Eleanor of her own will (spontanea voluntate), signed in her own hand (propria manu hanc cartam roboro e confirmo) and sealed with her effigy is one of the earliest testimonies of Henry II’s daughters’ involvement in the spread of the Becket cult outside Angevin territories. Significantly, this document predates by two years another diploma issued by the King for the protection of the same altar in January 1181, containing identical terms (González 1960, vol. II, pp. 603–4, doc. 355).

This document proves Eleanor’s undeniable personal implication in her family’s cause to promote the cult of the Canterbury martyr. She never forgot she was Henry II’s daughter. However, this does not justify the assumption that she was behind most of the liturgical and material evidence relating to the new martyr which emerged in Castile at the turn of the thirteenth century, as has sometimes been claimed (for a detailed account of these claims, see Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013 and Cerda 2016a).19 The claim that Eleanor had an exclusive role in the dissemination of the cult implies denying the many attested contributions to that process on the part of clerics and laymen who had travelled from England or Aquitaine to Castile as part of the bride’s retinue, as well as Castilian prelates and monks who were likewise engaged in the ecclesiastical implications of the new saint’s cult. As José Manuel Cerda states, referring to Castile, “apart from her diploma for Toledo Cathedral, the evidence for Leonor’s active interest in the promotion of the Becket cult is inconclusive” (Cerda 2016a, p. 142). Could these conclusions be applicable to the artistic sphere?

The adoption of foreign cultural elements to channel a dynastic identity that would set Alfonso and Eleanor apart from their neighbouring kingdoms found one of its key allies in the plastic arts. In the fifty years they sat on the throne, the artistic environment of their territories experienced a profound change as the final manifestations of late Romanesque coexisted with the unfolding early Gothic styles. As a result, works were executed by artists of assorted origins and open to influence from other quarters, generating an effervescent artistic and cultural environment which the royal couple eagerly embraced (revised and updated in Poza Yagüe and Olivares Martínez 2017). Working jointly as was their habit—una cum uxore mea was the most frequent heading formula in documents issued by Alfonso’s chancellery—the King and Queen commissioned some of the most important buildings of their time, such as the nunnery of Las Huelgas and the Hospital del Rey in Burgos, as well as Cuenca Cathedral. As patrons of the arts, they gave financial support to the masters who erected these buildings, such as Garsión in Santo Domingo de la Calzada, Fruchel in Ávila or the (Englishman?) magistro Ricardo (Richard) in Burgos. They even had the rare ability among people of their time to exploit the use of their own effigies to channel power, and even to suggest holiness (Pérez Monzón 2002, 2017; Poza Yagüe 2017).

In recent years, scholars have underscored the powerful presence of Eleonor and certain members of her retinue in this process within Castile (Ocón Alonso 1997b; Walker 2007; Valdez del Álamo 2015, 2017; Cerda 2018). Setting aside the proposals that discourse at length on the political suitability of Alfonso’s choice of Burgos as his final resting place (D’Emilio 2005), certain studies claim that it was at the queen’s insistence that Las Huelgas convent and burial vault were built in the manner of her family mausoleum in Fontevraud (Walker 2005). Assuming this to be the case, it is not surprising to find that she played a part in the decision to recruit Ricardo—an English or Aquitanian master builder—to lead the project (Ricardo’s role as Master of Works instead of as a sculptor discussed in Palomo Fernández and Ruiz Souza 2007, p. 38). Some of the miniaturists who worked on the illuminations of two Romanesque manuscripts produced in Burgos in the late twelfth century were also probably English (Yarza Luaces 1991). The elongated, softly shaped, ductile, elegant, affected figures dressed in finely pleated robes which appear in the Burgos Bible (c. 1175) and the Cardeña Beatus (c. 1187) were habitual in manuscripts from the English Channel area. It has also been suggested that these codices may have been the driving force behind a renewal of monumental sculpture in the last third of the twelfth century towards forms which have been defined as Byzantinist (Ocón Alonso 1992, 1997a). The same has been claimed for the English Bestiaries produced in approximately 1200 in relation to pictorial groups such as the frescoes at San Pedro de Arlanza (Pagès Paretas 2017), a church which also had close links with the Crown. Was the Almazán antependium one of these works she directly promoted?

Although the above is the weightiest argument proposed by most of the researchers who have approached this topic,20 it is impossible to confirm such a hypothesis. If any documentation ever attested the presence of the royal couple in Almazán around the time the frontal was carved, they have not survived. There is no record of a potentially relevant event in the town dating from the time the sculpture was commissioned. Even the patrimonial and/or emotional argument fails to provide the necessary evidence. Since Almazán was not included in the territories given to Eleanor as part of her dowry on her marriage to Alfonso, it appears that, at least in principle, the idea that the frontal was simply a gift from the Queen to her direct subjects is not adequately endorsed by evidence.21 I therefore consider that, while it is beyond doubt that thanks to her endeavours the cult of Thomas Becket spread in the Soria area of Castile, there is no substantial historical or artistic evidence to attribute the direct decision to commission the Almazán frontal to Eleanor of England.

2.2. The King

The chances of the King being directly involved in the matter of the frontal hardly differ from the Queen’s, so I shall obviate the common points. I have also been unable to trace any exceptional events set in Almazán around the dates proposed for its manufacture which might have led Alfonso to commission the piece on his own, although perhaps he was not short of political or pious reasons.

When Henry II of England made a public declaration attributing his providential victory over the Scottish King William I in 1174 to the assistance of Thomas Becket, the Canterbury martyr became the patron saint of the Plantagenet dynasty. If supernatural protection could be considered both “a family matter” and “a matter of state”, Henry’s son-in-law Alfonso VIII might have considered invoking the saint’s help in any of the many conflicts he engaged in during his reign. The Castilian king maintained open hostilities with the neighbouring kingdoms of León and Navarra during a protracted period of his rule, including territorial disputes in some parts of the Soria province. He fought his Muslim neighbours too, securing several momentous victories which allowed the Castilian troops to advance southward significantly—such as the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212—but also suffering some painful defeats, as in the 1195 battle of Alarcos. The fact that the King signed a document to grant protection to an altar dedicated to St Thomas Becket in Toledo in 1181, soon after the landmark conquest of Cuenca, might point in that direction, but the king did not mention that victory in his diploma.22

Unlike his father, who made frequent visits to Almazán, Alfonso VIII did not have a particularly intense relationship with the town. It does not appear among the places the King visited or passed through on a regular basis, as confirmed by the royal itineraries revealed by mapping the locations where he subscribed documents. The King only signed two documents, dated 1185 and 1190, in Almazán in the twenty or so years that elapsed between Thomas Becket’s canonisation in 1173 and the late 1180s, by which time, in my view, the frontal must have been completed.23

Over five years later, in 1196, Alfonso’s troops liberated Almazán from a siege by Sancho el Fuerte, King of Navarre, in one of many confrontations between the two kingdoms in that period. As I have pointed out elsewhere, the decision to commission the piece may have been triggered by an appeal to St Thomas Becket to tip the scales in favour of the Castilians in that battle. This may be supported by the fact that the antependium was placed in a church dedicated to St Michael, an archangel with military connotations and captain of the heavenly host (Poza Yagüe 2017, p. 78). However, this option is not compatible with the chronological and stylistic proposal I am presenting in this article for the frontal.

2.3. The Bishop

On a personal level, Alfonso VIII’s position in relation to the pre-eminence of regnum vs. sacerdotium was probably virtually identical to that of his Staufen or Plantagenet contemporaries and relatives. On the other hand, he was faced with the challenges of perpetual confrontation with the neighbouring monarchs since the turbulent days of his youth, with the added pressure to continue the progress of the Reconquest. This combination of circumstances led the Castilian King to adopt an intelligent stand from the early days of his reign, which required winning the loyalty and, accordingly, the support (auxilium) of the bishops of his time.24 Many of these prelates did not hesitate to join Alfonso on the battlefield and he corresponded by referring to them in many documents in affectionate, intimate and familiar terms. Nevertheless, this supposed balance of power between the Crown and the kingdom’s dioceses did not mean that the bishops prioritised the king’s affairs over church business, nor that they relinquished the legitimate defence of the principle of libertas ecclesiae (Ayala Martínez 2007, 2013).

It is in this precise context that the Castilian bishops assumed a leading role in the promotion of the cult of the Canterbury saint (Cavero Domínguez 2011). In the words of Carlos de Ayala, “the remarkably swift expansion of the cult of St Thomas Becket in some Castilian churches could be seen as a symptom of the church’s thirst for preeminence” (Ayala Martínez 2007, p. 174, n. 106), because “we do not believe the Castilian bishops’ interest in this cult obeyed solely to the presence on the throne of Queen Eleanor, daughter of Henry II. A person who was known for being a martyrial victim of royal intrusion could not but conjure up a reminder of an uncomfortable message to the Crown. This could have been a subtle way for the bishops to align themselves with ideals which were theoretically impossible to renounce” (Ayala Martínez 2013, p. 261).

Almazán belonged to the Sigüenza bishopric, one of the most active advocates of the Becket cult (Dogson 1902). Cerebruno, bishop of Toledo in 1177—when the Count and Countess of Lara sponsored the above-mentioned altar dedicated to the saint—had previously been bishop of Sigüenza. The task of consecrating the chapel to St Thomas in the under-construction cathedral’s east end fell to his successor, Joscelmo († 1178).25 The Becket liturgy was still celebrated in this diocese several decades later—in approximately 1197—as recorded in documents exchanged by Pope Celestine III and the then bishop, Bernardo (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, pp. 51–52).

In addition to the general context, it is important to know whether a specific incident occurred which might have triggered the commission of the Almazán piece. Although at this point it is only a hypothesis which cannot be confirmed by documentary evidence, I believe that in this case I am able to give a positive answer.

On 18 June 1180, in an atmosphere charged with the clergy’s defence of the principle of libertas ecclesiae, a set of ecclesiastical statutes were enacted in Nájera which implied the King’s acknowledgment of the Church’s privileges in the Kingdom of Castile. Among other measures of a patrimonial and economic nature, the statutes guaranteed the inviolability of diocesan properties during any periods when the sees were vacant, as well as an exemption from certain taxes and duties which were explicitly listed (Ayala Martínez 2007, pp. 173–74). The first Castilian diocese to be granted the statute was none other than Sigüenza, through a document issued at Ayllón on 12 July (González 1960, vol. II, pp. 589–91, doc. 348).

In the summer of 1180, the bishop of Sigüenza was Arderico. As Carlos de Ayala confirms, several documents dating from Arderico’s brief period as head the diocese have survived. These records confirm his fluid relationship with the King who, in August 1181, granted him, among other benefits, a tenth of all royal revenues from the territory covered by the diocese, explicitly including those collected in Almazán (Ayala Martínez 2007, p. 158; González 1960, vol. II, pp. 652–54, doc. 376).

Several years earlier, in February 1161, a legal dispute between the bishoprics of Osma and Sigüenza relating to the Almazán clerics’ refusal to hand over their tythes (diezmos), claiming an ostensible royal concession, had been settled in favour of Sigüenza. The judgement included a reminder to the effect that it was not incumbent on kings, princes or any other laymen to intervene in the management of the Church’s assets (Ayala Martínez 2013, pp. 239–40, n. 3).26

Twenty years later, with the defence of the privileges afforded by libertas ecclesiae still in the air, sheltered by the ecclesiastical statute, and in response to the King’s concession of the tythes, it is possible that Bishop Arderico commissioned a stone relief portraying the scene St Thomas Becket’s martyrdom, as a reminder to Almazán’s wayward clergymen of their duty to pay their dues to the diocese and to abandon the claims of a royal exemption which they had alleged in the past. His arguments and defence closely reflected those which had led the English bishop to his death, and this was illustrated on the relief.

If, as I understand, this was the motive for the commission of the frontal and if the initiative came from the Bishop, the timescale coincides with the work’s stylistic chronology. Arderico was bishop of Sigüenza between 1178 and 1184, an accurate match for the dates proposed for the manufacture of the antependium in the early 1180s.

3. Conclusions

As late as the 1250s, the Cantigas de Santa María refer to Eleanor as “filla del Rei d’Ingraterra, moller del Rei Don Alffonsso” [daughter of the King of England, wife of King Alfonso],27 highlighting her English parentage and ancestry, as opposed to her status as Queen of Castile even though she had been on the throne for nearly fifty years. It is undeniable that the presence of one of Henry II Plantagenet’s daughters as queen consort in Castile fostered the immediate reception, adoption and dissemination of the cult of St Thomas Becket in the territories ruled by Alfonso VIII. This, however, does not warrant the conclusion that most of the early documented examples of this cult in Castile were the result of her exclusive influence. At any rate, not in the case of the Almazán frontal.

I have argued that this work was carved by an artist who had trained in the sculpture workshops which had been active in the chapterhouse at El Burgo de Osma Cathedral; that it was commissioned by the Sigüenza Church Council—the ecclesiastical authority covering Almazán—on the personal initiative of Bishop Arderico before his transfer to the Palencia diocese in 1184; and that his motivation may be directly related to the enactment of the ecclesiastical statutes of the realm in the early summer of 1180.

To define the themes comprised in the iconographic programme of the frontal, the artist may have resorted to the accounts of the assassination that appeared in the earliest Vitae to arrive in Castile. For details of the specific shapes, motifs and scene development, his model was far closer to home and much more familiar to him. The patterns on the antependium can be easily recognised in the carvings on the capitals and mouldings of the arched windows in the chapterhouse at El Burgo de Osma, as well as in the capital representing the Massacre of the Innocents inside the hall itself.

The timing of this work in the early 1180s (c. 1180–1184) is perfectly compatible with the timeline proposed for the presence of a stonework atelier at El Burgo de Osma. It also matches Bishop Arderico’s term at the Sigüenza diocese and coincides with the period in which the defence of the Church’s freedom embodied in the statutes was a burning issue. The Almazán antependium is the earliest visual representation of Thomas Becket’s martyrdom in the western kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, although certain documented initiatives linked to the Becket cult predate it, such as the foundation and funding of an altar dedicated to him in Toledo cathedral sponsored by Count Nuño Pérez de Lara and his wife Teresa in 1177; the dedication of one of the chapels in the chancel of Sigüenza Cathedral to the saint, including the possible reception of a relic during Bishop Joscelmo’s tenure and, therefore, before his death in 1178; or the possible presence of a church dedicated to St Thomas in Salamanca by 1175. The antependium would therefore be contemporaneous with the Terrassa pictoric cycle in Catalonia, which Carles Sánchez has tentatively dated to 1180–1190 (Sánchez Márquez 2020, pp. 70–71), but no other link between the two has been detected.

Finally, why was the church of San Miguel chosen to house the antependium? San Miguel was just a parish church, but probably the most important of all those that were in the village. Its prominence among Almazán’s churches may have been due to its location on an open space next to the town wall, a vantage point that offered both protection and a panoramic view of the town. The Hurtado de Mendoza family later chose the same spot, for identical reasons, to build their palace as the leading dynasty of the town. However, unfortunately, this does not answer my question. I am aware of that. So, until such time as more information becomes available, I finish these lines by evoking the happy coincidence that links the archangel Michael, in his role as psychopomp, leading souls to heaven, and the angel on the frontal as he raises Thomas Becket’s soul to heaven wrapped in a cloth.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Maria Fernández for the translation of this text.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Its name originates in the Arabic al-mahsan—“the bastioned”—indicating its strategic importance since the time of the Islamic conquest in the tenth century. After Alfonso the Battler’s death, in 1134, Almazán was permanently annexed to the Kingdom of Castile. Its ecclesiastical affiliation to the Diocese of Sigüenza was determined at the Council of Burgos in 1136 (Minguella y Arnedo 1910, vol. I, p. 358; Loperráez Corvalán [1778] 1978, vol. I, p. 114 and Ortego y Frías 1973, pp. 11–12). |

| 2 | The church has three aisles separated by cruciform pillars supporting pointed arches. At the eastern end, the central nave features a semi-circular apse at the end of a long straight section crowned with a decorative cornice formed by small trefoil arches on corbels. The side aisles, unusually narrow and topped with pointed barrel vaults, terminate in minor apses on the inside of the church, and straight perpendicular walls on the outside. A striking feature is the deviation of the aisles’ central axis at the choir, probably because of miscalculation of the church’s measurements and the need to adapt the building to uneven terrain, including a steep slope down to the river by the northern wall. San Miguel’s most outstanding feature is the lantern tower, supported by a system of stepped squinches and features an unusual ribbed vault in a star pattern with oculi in the clear spaces at the centre and between the ribs that let sunlight into the building. Each pair of ribs rises from a decorative console. Unlike the simply carved capitals in the rest of the church, these are the work of a skilled artist, or perhaps a small team of sculptors, who had learned their trade in the workshops that were active at El Burgo de Osma Cathedral in the late 1170s. These consoles are remarkable for their fleshy foliage decorations—great leaves whose tips droop by their own weight creating hollows that enhance the play of light and shadow. The figures are surprising in their dynamism, attention to detail, anatomical accuracy and plasticity, be they bestiary creatures—inspired by the carvings in the monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos—or elaborate scenes, like the one showing a pair of knights riding on harpies (among many other sources, see Madoz 1845, vol. II, pp. 77–78; Rabal 1889, p. 387; Lampérez y Romea 1901; Taracena and Tudela [1928] 1997, pp. 209–11; Gaya Nuño 1946, pp. 186–95; Sainz Magaña 1984, vol. I, pp. 500–22; Rodríguez Montañés 2002; Huerta Huerta 2012, pp. 51–53). |

| 3 | Since this text is not focused on historical aspects of the life (and even the afterlife) of the saint, I refer to Raymonde Foreville (Foreville 1971) and, specially, to the Anne Duggan editions (Duggan 2004, 2007 esp.) that continue to be the very leading works on Thomas Becket. |

| 4 | It has also been suggested that the sculpture might have been the front panel of a sepulchre. This is certainly a possibility because it was not unusual to decorate these items with scenes from the lives of saints. In this case, however, it seems less likely than the altar-front option (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, p. 79). |

| 5 | Despite its age, Borenius (1932) continues to be a leading work on Becket iconography. |

| 6 | “… in malitia Annam et Caipham, Pilatum et Herodem amplius praecedentes…” (Vita Quarta et Quinta, auctoribus Joanne Decano Salisburiensi et Alano Abbate Tewkesburiensi, in Migne 1854, P. L. vol. 190, col. 205). |

| 7 | “… sive in auro, sive in argento, aut vestibus, aut variis ornamentis, aut libris, aut privilegiis aut aliis quibuscunque scriptis aut equitaturis, insatiabili avaritia et stupendo ausu diripientes, ea, ut libuit, inter se diviserunt, imitatores eorum facti, qui inter se Christi vestimenta partiti sunt, licet eos quodammodo praecedebant in scelere “ (Migne 1854, P. L. vol. 190, col. 207). |

| 8 | “… in pavimento corpus, in sinum Abrahae spiritum collocavit” (Vita Prima, auctore Edwardo Grim, in Migne 1854, P. L. vol. 190, col. 47). As Guardia argues, to understand the iconographical process she names “cristo-mimesis”, it is essential to bear in mind the interpretation of Becket’s martyrdom offered by some of his early biographers, such as John of Salisbury and Edward Grim mentioned above, or Benedict of Peterborough, who asserted that “Nec ullius martiris pasionem facile credimus invenire, quae passioni Dominicae tanta similitudine respondere videatur” (en Migne 1854, P. L. vol. 190, col. 278, quoted from Guardia Pons 2011, p. 176). For other scholars, this scene could be a miraculous event, maybe a resurrection and perhaps in relation to some of the miracles of the Cantuarian saint (Rodríguez Montañés 2001, 2002, p. 141; Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, p. 81; with doubts in Sánchez Márquez 2020, p. 95). |

| 9 | On the very important role played by the Limousin enamelled casket in the diffusion of the Thomas Becket’s iconography, see also (Caudron 1975; Caudron 1993; Caudron 2011; and Gauthier 1975). |

| 10 | A third casket, also originating in Palencia, is known to have existed but its whereabouts are unknown (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, pp. 117–18). As of today, it is impossible to know whether it was manufactured earlier or later than the other two, whether it had a matching iconographic programme or whether, perhaps, it resembled the Almazán mode |

| 11 | As I have summarised elsewhere, most Becket hagiographies describing his martyrdom were written immediately following the events of December 1170 by authors close to the saint, many of whom were members of the Benedictine community of Christ Church, to which Becket himself belonged. The most popular ones were William of Canterbury’s Vita et Passio S. Thomae, auctore Willelmo, monacho cantuariensi, Benedict of Peterborough’s Passio Sancti Thomae Cantuariensis, auctore Benedicto Petriburgensi abbate, Alan of Tewkesbury’s Vita Sancti Thomae Cantuariensis archiepiscopi et Martyrus, auctoribus Joanne Seresberiensi et Alano abbate Tewkesberiensi, and Edward Grim’s Vita Sancti Thomae, Cantuariensis archiepiscopi et martyris, auctore Edward Grim, written by one of the permanent characters in representations of the assasination. The first miniature image of this iconographic programme has the same origin, having been illuminated in the Christ Church scriptorium c. 1180. This corpus of narratives provides many of the details which were later incorporated in the imagery, such as Grim’s protective moves, which caused him serious wounds to the back and arm (Poza Yagüe 2013, p. 55). These testimonies were eventually collected in a monumental work (Robertson and Shepard 1875–1885). For an analysis of this book and a classification of the different Vitae and Passio, see (Guardia Pons 1998–1999, pp. 40 ff., especially p. 41, n. 8). Becket also as subject of fantastic Medieval literature from the moment of his death in ‘A wonderous tale’ (de Beer and Speakman 2021, pp. 171–85). |

| 12 | Without being able to specify a precise date, scholars seem to agree on a chronology towards the end of the first quarter of the 13th century (Cavero et al. 2013, p. 135 and especially relevant for the knowledge of the codices of the library of this monastery Suárez González 2007, pp. 289–306). |

| 13 | Cod. 13-H, preserved in Soria Public Library. Its precise content is unknown because the office was written in a two volume Gradual, the first of which, containing the commemorations between March and October, has survived, while the second, including the December celebrations, is lost. Nonetheless, the ritual is announced in a marginal note contemporary to the main text: Lamberti episcopi officium in natale sancti Thome episcopi et martiris. Quere in alio libro in octauis natiuitatis Domini (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, p. 160). |

| 14 | The fresco tells the story of the martyrdom in three friezes, one above the other, to be read from bottom to top. The lower panel shows the precise moment when a knight stabs Thomas Becket in the back as he officiates at the altar, before the horrified eyes of a group of onlookers. The upper sections show two further scenes, the content of which has yet to be agreed. Due to their advanced state of decay, it is barely possible to discern what might be a funerary scene in the presence of a majestic-looking figure. Milagros Guardia and Fernando Galván understand these scenes to be miraculous events subsequent to the saint’s death (Guardia Pons 2011, p. 170, n. 27; Galván Freile 2008, p. 208); in a later work, Galván recognises two episodes directly linked to Henry II in the frescoes: the King’s visit to a leper hospital in Harbledown in the middle section, and the public atonement ritual performed by Henry in 1174 before Becket’s tomb at the top (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, p. 97). Carles Sánchez does not rule out that the two scenes tell a single story (Sánchez Márquez 2020, p. 96), while Fernando Gutiérrez Baños speculates on the miraculous healing of the French king Louis VII’ only son in 1179 thanks to the Canterbury saint’s intercession (Gutiérrez Baños 2005, vol. II, pp. 274–75). |

| 15 | While conscious that it is impossible to make this gothic mural painting directly dependent on Alfonso and Eleanor, who died in 1214, Carles Sánchez points out that it would be “exciting” to think that the royal couple had assumed the chapel’s patronage, dedicating it to the cult of the English saint, and that the decorations followed several decades later (Sánchez Márquez 2020, p. 96). Milagros Guardia also suggests the idea of memories projected forward in time—although without mentioning the monarchs—when she hypothesises that this chapel, which had long been dedicated to Thomas Becket, might have also housed another antependium—a companion piece to the Becket carving—featuring the scene of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, a Christological theme which was frequently linked to Becket’s hagiography (Guardia Pons 2011, p. 170). The hypothesis of a “renewed pictorial cycle that recalls a previous one which has been lost” is also explored in Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013 (p. 98, n. 209). I share with these authors the possibility that a chapel dedicated to the cult of the Canterbury martyr in the church of San Nicolas existed before the end of the twelfth century. |

| 16 | Having been painted almost a century after Eleanor’s death, it seems redundant to insist on her as the ultimate inspiration for these pieces. Not every reference to Becket in Castile can be linked to her and the tradition of attributing a leading role to the royal couple in the construction of the best Romanesque artworks in Soria no longer seems sustainable. It is time to detach the Soria/Becket link from Queen Eleanor. |

| 17 | Documented in the deed of donation to Abbot Juan de Retuerta by Leonor de Aragón, consort of King Jaime I. The fact that the Queens of Castile and Aragon shared the same name has caused some confusion in the past as to who was behind certain actions in the town. |

| 18 | Named in the document as “W., eiudem altaris beati Thome capellano”. |

| 19 | There is a slight chance that the royal couple—not the Queen on her own—donated a Becket relic included in the inventories of Santo Domingo de Silos, since this Benedictine monastery was one of a few abbeys under the monarchs’ patronage. |

| 20 | Exceptions to this current of thought are G. Cavero’s working group, which offered a few options but did not finally settle for any of them because “it is not possible to go beyond the conjecture” (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013, p. 213), and José Manuel Cerda, who concluded that “it is not easy to link the agency of Leonor with some Romanesque sculpture in the church of San Miguel” (Cerda 2016a, p. 140). |

| 21 | At least in principle, because the most reliable testimony of the Queen’s leadership in the promotion of the cult of the Canterbury martyr—the above-mentioned Toledo diploma dated 1179—includes the nearby town of Alcabón with all its properties in the terms of her donation (Alcauon cum uniuersis pertenenciis suis, uineis, terris, pratis, pascuis, montibus, fontibus, ualibus, fructiferis arboribus et infructuosis, ingressibus et egressibus, omnesque collaces ibidem in presenti populatos uel populandos) (González 1960, vol. II, pp. 542–43, doc. 324), despite the fact that it was not her personal property. At any rate, I believe this case should be treated as an exception rather than the rule. On the places included in the Queen’s dowry, see (Cerda 2016b). |

| 22 | The original document issued by count Nuño Pérez de Lara and his wife Teresa in July 1177 was signed in obsidione Conche—during the siege of Cuenca. The city fell to the Christians in September 1177 after a nine-month siege. The diploma is preserved in the archives of Toledo cathedral. I take the reference from (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013), pp. 49–50. |

| 23 | The first, dated 7 December 1185 (González 1960, vol. II, pp. 764–65, doc. 445). The second is not clearly dated but is likely to have been issued in early October 1190 (González 1960., vol. II, pp. 959–60, doc. 559). |

| 24 | In the words of Carlos de Ayala, “as far as Alonso VIII was concerned, the Church in his kingdom was above all an efficient legitimation instrument with which to increase his power, a secondary tool in the service of the royal political project which required a team of bishops made up of loyal associates” (Ayala Martínez 2013, pp. 249–50). |

| 25 | This chapel was later dedicated to St John and St Catherine. A relic of the martyr was displayed in it at the bishop’s request (Dogson 1902; Minguella y Arnedo 1910, vol. I, p. 125). |

| 26 | On this ruling, Minguella adds that “the Almazán [clergymen] appealed but then abandoned their appeal and submitted to the Bishop’s judgment in the matter of the oblations” (Minguella y Arnedo 1910, vol. I, pp. 123–24). This episode is also mentioned by (Cavero Domínguez et al. 2013), pp. 212–13, but without establishing any direct link between the dispute and the frontal. |

| 27 | Reference and transcription from (Cerda 2018), p. 35. |

References

- Ayala Martínez, Carlos de. 2007. Los obispos de Alfonso VIII. In Carreiras Eclesiásticas no Ocidente Cristão: Séc. XII-XIV. Lisboa: Universidade Católica Portuguesa–Centro de Estudios de História Religiosa, pp. 151–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala Martínez, Carlos de. 2013. Alfonso VIII y la Iglesia de su reino. In 1212, un año, un Reinado, un Tiempo de Despegue. XXIII Semana de Estudios Medievales (Nájera, 30 julio–3 agosto 2012). Edited by Esther López Ojeda. Logroño: Instituto de Estudios Riojanos, pp. 237–96. [Google Scholar]

- Borenius, Tancred. 1932. St Thomas Becket in Art. London: Methuen & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Boto Varela, Gerardo. 2000. Ornamento sin delito. Los seres imaginarios del claustro de Silos y sus ecos en la escultura románica peninsular. Santo Domingo de Silos: Abadía de Silos. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, Colette. 2014. The Daughters of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Caudron, Simone. 1975. Les châsses de Thomas Becket en émail de Limoges. In Thomas Becket: Actes du Colloque International de Sedières (19–24 août 1973). Edited by Raymonde Foreville. Paris: Beauchesne, pp. 233–41. [Google Scholar]

- Caudron, Simone. 1993. Les châsses reliquaire de Thomas Becket, émaillées: Leur géographie historique. Bulletin de la Société Archéologique et Historique du Limousin 121: 55–83. [Google Scholar]

- Caudron, Simone. 2001. Arqueta relicario de Santo Tomás Becket. In De Limoges a Silos. Edited by Joaquín Yarza. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Acción Cultural Exterior (SEACEX)–Ediciones El Viso, pp. 242–44. [Google Scholar]

- Caudron, Simone. 2011. La diffusion des châsses de saint Thomas Becket dans l’Europe médiévale. In L’œuvre de Limoges et sa Diffusion: Trésors, Objectes, Collections. Edited by Danielle Gaborit-Chopin and Frédéric Tixier. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cavero Domínguez, Gregoria (coord.), Etelvina Fernández González, Fernando Galván Freile, and Ana Suárez González. 2013. Tomás Becket y la Península Ibérica (1170–1230). León: Universidad de León-Instituto de Estudios Medievales. [Google Scholar]

- Cavero Domínguez, Gregoria. 2011. Santidad y realeza: Thomas Becket en la corte castellana de Alfonso VIII (1158–1214). In Cristãos e Muçulmanos na Idade Média Peninsular. Encontros e Desencontros. Edited by Rosa Varela, Mario Varela and Catarina Tente. Zaragoza: Pórtico, pp. 269–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cerda, José Manuel. 2016a. Leonor Plantagenet and the Cult of Thomas Becket in Castile. In The Cult of St Thomas Becket in the Plantagenet World, c. 1170–220. Edited by Paul Webster and Marie-Pierre Gelin. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 133–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cerda, José Manuel. 2016b. Matrimonio y patrimonio. Las arras de Leonor Plantagenet, reina consorte de Castilla. Anuario de Estudios Medievales 46: 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, José Manuel. 2018. Diplomacia, mecenazgo e identidad dinástica. La consorte Leonor y el influjo de la cultura Plantagenet en la Castilla de Alfonso VIII. In Los Modelos Anglo-Normandos en la Cultura Letrada en Castilla (Siglos XII–XIV). Edited by Amaia Arizaleta and Francisco Bautista. Toulouse: Presses universitaires du Midi Méridiennes, pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- D’Emilio, James. 2005. The Royal Convent of Las Huelgas: Dynastic Politics, Religious Reform and Artistic Change in Medieval Castile. In Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture 6. Edited by M. Parsons Lillich. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, pp. 191–82. [Google Scholar]

- de Beer, Lloyd, and Naomi Speakman. 2021. Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dogson, Edward Spencer. 1902. Thomas Á Becket and the Cathedral Church of Sigüenza. Notes and Queries, 227. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Anne. 2004. Thomas Becket. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Anne. 2007. Thomas Becket: Friends, Networks, Texts, and Cult. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Español, Francesca. 2001. Los esmaltes de Limoges en España. In De Limoges a Silos. Edited by Joaquín Yarza. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Acción Cultural Exterior (SEACEX)–Ediciones El Viso, pp. 87–111. [Google Scholar]

- Foreville, Raymonde. 1971. Mort et survie de saint Thomas Becket. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 53: 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván Freile, Fernando. 2008. Culto e iconografía de Tomás de Canterbury en la península Ibérica (1173–1300). In Hagiografia Peninsular en els Segles Medievals. Edited by Francesca Español and Francesc Fité. Lleida: Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida, pp. 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, Marie-Madeleine. 1975. Le meurtre dans la cathédrale, thème iconographique. In Thomas Becket: Actes du Colloque International de Sedières (19–24 août 1973). Edited by Raymonde Foreville. Paris: Beauchesne, pp. 249–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gaya Nuño, Juan Antonio. 1946. El Románico en la Provincia de Soria. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- González, Julio. 1960. El Reino de Castilla en la Época de Alfonso VIII. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 3 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Guardia Pons, Milagros. 1998–1999. Sant Tomàs Becket i el programa iconogràfic de les pintures murals de Santa Maria de Terrassa. Locvs Amœnus 4: 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Guardia Pons, Milagros. 2009. Il precoce approdo dell’iconografia di Thomas Becket nella peninsola ibérica. Il martirio di Becket o il racconto di una norte annunciata. In I Santi Venuti dal Mare. Atti del V Convegno Internazionale di Studio (Bari-Brindisi, 14–18 Dicembre 2005). Edited by Maria Stella Calò Mariani. Bari: Mario Adda Editore, pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Guardia Pons, Milagros. 2011. Les Cahieres de Saint-Michel de Cuxa. XLII: 165–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Baños, Fernando. 2005. Aportación al Estudio de la Pintura de Estilo Gótico Lineal en Castilla y León: Precisiones Cronológicas y Corpus de Pintura Mural y Sobre Tabla. Madrid: Fundación Universitaria Española, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta Huerta, Pedro Luis. 2012. Todo el Románico de Soria. Aguilar de Campoo: Fundación Santa María la Real. [Google Scholar]

- Jasperse, Jitske. 2017. Matilda, Leonor and Joanna: The Plantagenet sisters and the display of dynastic connections through material culture. Journal of Medieval History 43: 523–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasperse, Jitske. 2020. Medieval Women, Material Culture, and Power. Matilda Plantagenet and Her Sisters. Leeds: ARC Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lampérez y Romea, Vicente. 1901. San Miguel de Almazán. Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Excursiones 96: 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Loperráez Corvalán, Juan. 1978. Descripción histórica del Obispado de Osma. First published 1778 (Madrid: Imprenta Real). Turner: Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- López de Guereño Sanz, María Teresa. 1997. Monasterios Medievales Premonstratenses. Reinos de Castilla y León. Salamanca: Junta de Castilla y León, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Lutan-Hassner, Sara. 2015. Thomas Becket and the Plantagenets Atonement through Art. Leiden: Alexandros Press. [Google Scholar]

- Madoz, Pascual. 1845. Almazán. In Diccionario Geográfico-Estadístico-Histórico de España y sus posesiones de Ultramar. Madrid: Establecimiento tipográfico de P. Madoz y L. Sagasti, t. II, pp. 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Melero Moneo, M. Luisa. 2001. Arqueta relicario de Santo Tomás Becket. In De Limoges a Silos. Edited by Joaquín Yarza. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Acción Cultural Exterior (SEACEX)–Ediciones El Viso, pp. 245–47. [Google Scholar]

- Migne, Jacques-Paul, ed. 1854. S. Thomae Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi et Martyris nec non Herberti de Boseham clerici ejus a secretis Opera Omnia. In Patrologia Latina, Tomus CXC. Paris: J.-P. Migne Editorem. [Google Scholar]

- Minguella y Arnedo, Toribio. 1910. Historia de la Diócesis de Sigüenza y de sus Obispos. Vol. I. Desde los Comienzos de la Diócesis Hasta Fines del siglo XIII. Madrid: Imprenta de la Revista de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos. [Google Scholar]

- Ocón Alonso, Dulce. 1992. Alfonso VIII, la llegada de las corrientes artísticas de la corte inglesa y el bizantinismo de la escultura hispana de fines del siglo XII. In Alfonso VIII y su Época. II Curso de Cultura Medieval (Aguilar de Campoo, 1–6 Octubre 1990). Aguilar de Campoo: Centro de Estudios del Románico, pp. 307–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ocón Alonso, Dulce. 1997a. El renacimiento bizantinizante de la segunda mitad del siglo XII y la escultura monumental en España. In Viajes y Viajeros en la España Medieval. V Curso de Cultura Medieval (Aguilar de Campoo, 20–23 Septiembre 1993). Aguilar de Campoo: Fundación Santa María la Real–Ed. Polifemo, pp. 263–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ocón Alonso, Dulce. 1997b. El papel artístico de las reinas hispanas de la segunda mitad del siglo XII: Leonor de Castilla y Sancha de Aragón. In La Mujer en el arte Español. VIII Jornadas de Arte del Departamento de Historia del Arte ‘Diego Velázquez’ (Madrid, CSIC, 26–29 Noviembre 1996). Madrid: Alpuerto, pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ortego y Frías, Teógenes. 1973. Almazán. Ilustre Villa Soriana. Madrid: Publicaciones de la Caja General de Ahorros y Préstamos de la Provincia de Soria. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès Paretas, Montserrat. 2017. Las pinturas de San Pedro de Arlanza en el contexto artístico de su época. In Alfonso VIII y Leonor de Inglaterra: Confluencias Artísticas en el Entorno de 1200. Edited by Marta Poza and Diana Olivares. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense, pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo Fernández, Gema, and Juan Carlos Ruiz Souza. 2007. Nuevas hipótesis sobre Las Huelgas de Burgos. Escenografía funeraria de Alfonso X para un proyecto inacabado de Alfonso VIII y Leonor Plantagenêt. Goya 316– 317: 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Monzón, Olga. 2002. Iconografía y poder real en Castilla: Las imágenes de Alfonso VIII. Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte UAM XIV: 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Monzón, Olga. 2017. ‘Bien Contar [Supieron] las Gestas del Buen Rey’. Memoria visual de Alfonso VIII. In Alfonso VIII y Leonor de Inglaterra: Confluencias Artísticas en el Entorno de 1200. Edited by Marta Poza and Diana Olivares. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense, pp. 109–47. [Google Scholar]

- Poza Yagüe, Marta, and Diana Olivares Martínez, eds. 2017. Alfonso VIII y Leonor de Inglaterra: Confluencias artísticas en el entorno de 1200. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense. [Google Scholar]

- Poza Yagüe, Marta. 2013. Santo Tomás Becket. Revista Digital de Iconografía Medieval 9: 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Poza Yagüe, Marta. 2017. una cum uxore mea: La dimensión artística de un reinado. Entre las certezas documentales y las especulaciones iconográficas. In Alfonso VIII y Leonor de Inglaterra: Confluencias Artísticas en el Entorno de 1200. Edited by Marta Poza and Diana Olivares. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense, pp. 71–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rabal, Nicolás. 1889. España. Sus Monumentos y sus Artes. Su Naturaleza e Historia. Soria. Barcelona: Establecimiento Tipográfico-Editorial de Daniel Cortezo y C. [Google Scholar]

- Ridruejo Gil, María Antonia y María del Pilar. 1945. Cuatro frontales románicos de Soria. Archivo Español de Arte 68: 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, James Craigie, and Joseph Brigstocke Shepard, eds. 1875–1885. Materials for the History of Thomas Becket archbishop of Canterbury (canonized by Pope Alexander III, A.D. 1173). London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Montañés, José Manuel. 2001. N 6. Frontal de altar. In Soria Románica. El Arte Románico en la Diócesis de Osma-Soria. Catálogo de la Exposición (S.I. Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de El Burgo de Osma, 27 Junio–30 Septiembre 2001). Madrid: Fundación Santa María la Real–CER, pp. 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Montañés, José Manuel. 2002. Almazán. Iglesia de San Miguel. In Enciclopedia del Románico en Castilla y León. Soria I. Aguilar de Campoo: Fundación Santa María la Real, pp. 134–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Ana. 2014. La estirpe de Leonor de Aquitania. Mujeres y Poder en los Siglos XII y XIII. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Sainz Magaña, María Elena. 1984. El románico Soriano: Estudio Simbólico de los Monumentos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, vol, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Márquez, Carles. 2014. Becket o el martiri del millor home del rei. Les pintures de Santa Maria de Terrassa, la congregació de Saint-Ruf i l’anomenat Mestre d’Espinelves. In Pintar fa mil anys. El color i l’ofici del Pintor Romànic. Edited by Manuel Castiñeiras and Judit Verdaguer. Bellaterra: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona–Servei de Publicacions, pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Márquez, Carles. 2018. An Anglo-Norman at Terrassa? Augustinian Canons and Thomas Becket at the End of the 12th century. In Romanesque Patrons and Processes: Design and Instrumentality in Romanesque Europe. Edited by Jordi Camps, Manuel Castiñeiras, John McNeill and Richard Plant. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 219–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Márquez, Carles. 2020. Una tragedia pintada. El martirio de Tomás Becket en Santa María de Terrassa y la Difusión del culto en la Península Ibérica. La Seu d’Urgell: Anem Editors. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Márquez, Carles. 2021. Tomás Becket y la península ibérica: Imágenes, reliquias y comitentes. Románico 32: 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, Kay Brainerd. 1999. Angevin Marriage Diplomacy and the Early Dissemination of the Cult of Thomas Becket. Medieval Perspectives 14: 214–28. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez González, Ana I. 2007. El libro en los claustros cistercienses (una aproximación ca. 1140–1240). In El Monacato en los Reinos de León y Castilla (siglos VII–XIII). León: Fundación Sánchez Albornoz, pp. 263–325. [Google Scholar]

- Taracena, Blas, and José Tudela. 1997. Guía Artística de Soria y su Provincia. Soria: Ediciones de la Diputación Provincial de Soria. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez del Álamo, Elizabeth. 2012. Palace of the Mind. The cloister of Silos and Spanish sculpture of the twelfth century. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez del Álamo, Elizabeth. 2015. Cómo la reina Leonor de Inglaterra impactó en el románico de Castilla. Románico 20: 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez del Álamo, Elizabeth. 2017. Leonor Plantagenet: Reina y Mecenas. In Alfonso VIII y Leonor de Inglaterra: Confluencias Artísticas en el Entorno de 1200. Edited by Marta Poza and Diana Olivares. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense, pp. 249–68. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Rose. 2005. Leonor of England, Plantagenet queen of Alfonso of Castile, and her foundation of the Cistercian abbey of Las Huelgas. In imitation of Fontevraud? Journal of Medieval History 31: 346–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Rose. 2007. Leonor of England and Eleanor of Castile: Anglo-Iberian Marriage and Cultural Exchange in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. In England and Iberia in the Middle Ages. Edited by María Bullón-Fernández. Gordonsville: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yarza Luaces, Joaquín. 1991. La miniatura en Galicia, León y Castilla en tiempos de Maestro Mateo. In Actas del Simposio Internacional sobre ‘O Pórtico da Gloria e a arte do seu Tempo’. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia, pp. 319–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yarza Luaces, Joaquín. 2001. Arquetas relicario con historias de santos. In De Limoges a Silos. Edited by Joaquín Yarza. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Acción Cultural Exterior (SEACEX)–Ediciones El Viso, pp. 230–41. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).