Abstract

Independent art spaces not only play an important role in exploring frontiers in the visual arts but are often also pioneers discovering new artistic territories within cities. Due to their subordinate position in the field of art, they often occupy marginal spaces in terms of their location within the urban structure and/or in terms of their physical visibility within the built environment. Their location outside the established artistic cores reflects, at the same time, their weaker economic standing and wish to distinguish themselves from previous generations of cultural producers. Post-socialist cities offer the opportunity to study the spatial history of independent art spaces under different political and economic systems. In this paper, I have used a detailed database of private art galleries in the period from the 1970s to 2019 and content analysis of press and internet texts about them to uncover the stages of development of independent art venues in Krakow, Poland, an example of a post-socialist city with a rich cultural heritage. They included periods of dispersion within the wider inner-city followed by cycles of concentration in rather neglected quarters that were emerging as epicentres of alternative artistic life only to dissipate due to unfavourable economic conditions and the appearance of the next generations of artists who wanted to mark their distinctive presence both in the art world and in the urban space. I also discuss how independent art spaces were using their usually marginal, temporary and fluid sites in their artistic practices and the accumulation of symbolic capital in the field of art.

1. Introduction

Independent, non-public and non-profit art spaces constitute a vital component of the contemporary art system (Table 1). They operate outside market logic as they are more oriented towards supporting local artistic communities and promoting emerging and so-far under-recognised artistic values. As such, they constitute an alternative to commercial art dealers that usually have a more dominant position, offer works of highly recognised, often non-local artists and focus on building relations with art buyers and investors (Blessi et al. 2011). They are often artist-run spaces usually led by young and aspiring cultural producers or their collectives and as such they are an expression of the self-organisation of the artistic community (Bystryn 1978; Batia 1979; Tremblay and Pilati 2008; Phillips 2014; Uboldi 2020). More recently, they have tended to be called project spaces as they are increasingly process-oriented rather than only product-oriented and bring artists together around collaborative endeavours (Marguin 2015).

Table 1.

Independent art spaces within the contemporary art system.

Independent art spaces started to emerge to bypass traditional intermediaries without being forced to conform to the pressure of the art market and public art institutions. They are often a form of protest against the commodification of artistic practices and art works. As such, they provide greater creative freedom and space for experimenting beyond artistic conventions, crossing boundaries between art disciplines. Therefore, they may be a source of artistic innovation that introduces a new language in visual arts. They are also understood as a way to democratise access to culture as they integrate art production with exhibitions and offer closer interactions between art producers and art enthusiasts (Bystryn 1978; Batia 1979; Tremblay and Pilati 2008; Vivant 2010; Blessi et al. 2011; Pixová 2013; Vickery 2014; Phillips 2014; Marguin 2015; Kumer 2020; Valli 2021). By definition, they are therefore the embodiment of artistic heterodoxy and autonomy in the field of art standing in an antagonistic relationship with the orthodoxy and heteronomy1 represented by public and commercial art organisations that play the role of gatekeepers defending the existing definition of art and already established artistic values (Bourdieu 2016; Valli 2021). With time, some independent art venues may gain recognition and become more integrated with more institutionalised or market-oriented components of the art system (Blessi et al. 2011). As such, they become a point of reference for the next generation of aspiring artists and alternative art spaces, repeating the cyclical logic of the classification struggle in the field of art.

In this paper I focus on independent art spaces that were emerging in the Polish city of Krakow from the 1970s to 2019 and were considered as representatives of artistic heterodoxy and autonomy at the time of their activity in varying social, economic and political circumstances prior to and after 1989. Only non-public and non-profit sites with alternative programming were included. However, one needs to remember that the level of their artistic independence varied within this group as, for example, some of the art spaces examined obtained public support in the form of grants or reduced rents in municipal premises. The idea of an ‘independent art space’ itself was also evolving throughout the period under study, for example in terms of the name they were using (the term ‘gallery’ was popular among them until the 2000s when it was often abandoned because of its association with profit-oriented art galleries). Despite that, they all shared the common trait of being regarded as an alternative to art venues regarded as mainstream at the time. For the purpose of this text, key independent art spaces were identified based on the number of mentions in printed and online art magazines and on the prevailing opinions of art critics. They were studied in detail as representatives of a wider community of alternative artistic initiatives in subsequent periods.

The aim of this paper is to establish links between the locations of independent art consumption (sometimes accompanied by art production) and the changing urban landscape of a socialist and post-socialist city with a rich cultural heritage. The main research question refers to the spatial strategies of independent art spaces under different social, economic and political conditions. Particularly, in what way they were reflecting the main artistic antagonisms in the field of art across the urban space and as a consequence whether the spatial choices enabled them to distinguish themselves and build their symbolic capital. This paper extends knowledge of the so far under-researched spatial history of independent art spaces in socialist and post-socialist cities by recreating the stages of their spatial development in Krakow from the 1970s to 2019. The findings are drawn from a larger database of both non-profit and commercial private art spaces in Krakow compiled by the author and from a qualitative content analysis of press and internet texts which focused on the relationship between gallery programming and the sites they were occupying in the urban space.

This paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses various relations between sites of independent art consumption and urban space and introduces specific features of post-socialist cities in which this topic is still under-researched. Material and research methods are described in Section 3. Section 4 is devoted to the presentation of four stages of spatial development of the independent artistic landscape before and after 1989, during socialist and post-socialist times. In this section, findings from the qualitative content analysis are demonstrated to provide examples of different types of spatial strategies in subsequent periods. Section 5 provides a synthesis of the spatial history of independent art spaces in Krakow from the 1970s until the 2010s reflecting its cyclical nature (dispersion and later concentration in emerging art districts) and repeated attempts to use meanings associated with different parts of the city in artistic practices.

2. Literature Review—Independent Art Spaces in the Urban Space

Independent art spaces hold few economic and symbolic capital resources. Thus, they are usually situated in marginal places within the city. They may adopt a strategy to occupy niches with low physical visibility (in side streets, on higher floors, in cellars and attics) in established art districts dominated by more recognised commercial galleries (that is, a central location in the urban structure, but a marginal one within the built environment), or they may become pioneers in more liminal spaces not associated with artistic activities where they may benefit from greater physical visibility from the street level (on ground floors, with storefronts, in main streets or squares) (Molotch and Treskon 2009; Rius Ulldemolins 2012; Molho 2014). In the latter case, they could play a role of catalyst of gentrification, or at least be regarded as a sign of ongoing or future social and functional transformation (Vivant and Charmes 2008; Schuetz 2013; Phillips 2014; Vickery 2014; Valli 2021), which is often cyclically reproduced in different parts of the city and progressing as a frontier of urban change (Gray and Mooney 2011; Zukin and Braslow 2011; Colomb 2012; Valli 2021).

Founders of independent art spaces follow the path of early-career artists, which for economic reasons often choose to live and create in derelict areas away from established artistic cores, in districts inhabited by residents with a lower socio-economic status (Standl and Krupickaitė 2004; Tremblay and Pilati 2008; Rius Ulldemolins 2012; Phillips 2014; Schuetz and Green 2014; Debroux 2017). Like young creatives, they refer to the atmosphere of authenticity associated with historic and/or industrial buildings and to the “nourishing otherness” (Chełstowska 2009, p. 183) of working class or ethnic communities. It brings an additional aesthetic and semantic frame of reference to the works of art they exhibit, especially when it is reinforced by the site-specific context of reused interiors, distinguishing them from the white walls of traditional art galleries. For their audience, usually younger and less affluent, reaching such a site can constitute an additional added value of experiencing art (Zukin 2008; Molotch and Treskon 2009; Moulin 2009; Harris 2012; Rius Ulldemolins 2012; Schuetz 2013, 2014; Jansson 2014; Phillips 2014; Vickery 2014; Polyák 2015; Debroux 2017; Molho and Sagot-Duvauroux 2017).

Examples of such artist-oriented clusters of art spaces can be found in many large cities. In New York, after the Second World War, Greenwich Village became home to a number of now renowned abstract expressionists whose works were presented in galleries operating nearby. From the 1960s, the post-industrial district of SoHo took over the central role in setting artistic trends. A similar path is now followed by clusters of visual artists and independent art spaces on the edges of Manhattan or outside of it (Molotch and Treskon 2009; Zukin and Braslow 2011; Schuetz 2013, 2014; Schuetz and Green 2014; Valli 2021). In Montreal, experimental art initiatives are concentrated in the down-at-heel areas of Mile End and Le Plateau, further from the central art district. “The outspread distribution of artist-run centres/collectives … demonstrates the sequential displacement of artists who migrate to neighbourhoods with lower rents, reputations for being creative hubs, and distance from mainstream norms where innovation can more safely take place” (Phillips 2014, p. 42).

In London, the development of the East End gallery scene in the late 1990s was based on the success of the avant-garde generation of YBAs, or Young British Artists (Wedd et al. 2001; While 2003; Kim 2007). In Barcelona, the historical neighbourhood of El Raval developed into a bohemian district housing a number of independent art spaces (Rius Ulldemolins 2012). Similarly, in Istanbul, the derelict district of Beyoğlu gained the most popularity, but art spaces were also using post-industrial sites in the Karaköy district (Molho 2014; Molho and Sagot-Duvauroux 2017). In Mumbai, non-profit artist-run initiatives are concentrated in Bandra West, located on the border between the city and its suburbs. This district represents an artistic and spatial opposition to the more prestigious galleries in the historic city centre, focused on local elites and foreign art buyers (Ithurbide 2014).

The spatial configurations of art spaces in post-socialist cities remain an under-researched topic (e.g., study of project spaces in West and East Berlin—Marguin 2015; there was more interest in spatial dynamics of music venues, e.g., in Prague—Pixová 2013—and in Warsaw—Wojnar 2017) when compared with numerous accounts from Western European or North American metropolises (e.g., Wedd et al. 2001; Molotch and Treskon 2009; Zukin and Braslow 2011; Rius Ulldemolins 2012; Schuetz 2013, 2014; Jansson 2014; Phillips 2014; Schuetz and Green 2014; Valli 2021). This paper makes a contribution to filling this gap by adding another case study (see Ithurbide 2014; Molho 2014) going beyond the dominant Western perspective and representing semi-peripheries of the global art system.

Post-socialist cities offer an interesting perspective to study the development of an independent artistic landscape since the turn of the 1980s and 1990s when it underwent a rapid transformation from being under strict political control during the communist regime and a centrally planned economy (which included a large degree of oversight over art production and consumption) to democracy and a market economy with more artistic freedom on the one hand but with hardened economic constraints on the other (Guzek 2012; Możdżyński 2015). During the communist period, independent artistic initiatives were treated with suspicion for political reasons, which prompted them to occupy marginal locations in the urban fabric to hide from the eyes of censors (Marguin 2015; Nae 2018). During the first years of the turbulent post-1989 transition, one could observe uncoordinated changes in the urban space related to the privatisation and reprivatisation of real estate, the deregulation of rents, the disappearance of old uses of buildings and the emergence of new ones. At the same time, the system of values and social norms was shaken up, creating a favourable ground for experimental and countercultural artistic activities. Later, gradual social and economic stabilisation resulted in the closure of illegal squats and independent art spaces and the subordination of alternative forms of culture to the new order of neoliberal urbanism. As a consequence, independent art venues were often forced to stop their activities or to look for other tolerant and affordable places to continue them (Pixová 2013; Marguin 2015; Polyák 2015; Wojnar 2017).

One can expect that in post-socialist cities, in a similar manner to other large art cities (Mangset 1998; Wedd et al. 2001; Lizé 2010; Phillips 2014), the emergence of new generations of artists and art spaces created by them or collaborating with them should be reflected in their distinct location within the urban space. Alternative art spaces designate not only new artistic trends, but also often new territories for art that help them build their symbolic capital in the field of cultural production (Valli 2021). Their founders usually distance themselves from mainstream and/or market-oriented art institutions and previous generations of established artists. They use various strategies of urban resistance and subversion to break the rules of spatial organisation imposed by market forces and public authorities. They search for “cracks in urban landscapes” (Gibson 1999, p. 21) that give them greater autonomy, unfettered by rigid social norms and conventions of artistic orthodoxy. The ‘republic of artists’ in the Užupis quarter in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, that claimed to be an “island of peace and freedom for everybody” (Standl and Krupickaitė 2004, p. 45), could serve as a good example. Their connection with local art communities translates into stronger embeddedness in artists’ ‘live-work’ quarters (Wedd et al. 2001). The urban and social fabric of these neighbourhoods may be used by them as a source of inspiration, as a material or a background for their artistic practices, and it becomes incorporated in their artistic identity. Artists and art spaces may use meanings associated with different parts of the city (Molotch and Treskon 2009; Harris 2012; Rius Ulldemolins 2012), co-create them and transform them into buzz-rich places filled with the atmosphere of energy and excitement (Działek and Murzyn-Kupisz 2021). In the long run, one can observe the relocation of the urban frontier of artistic exploration, which results both from the artists’ need to differentiate themselves from older art groups, but often is also a reaction to the gentrification processes that affect artistic communities with low resources of economic capital (Tremblay and Pilati 2008; Zukin and Braslow 2011; Pixová 2013; Działek and Murzyn-Kupisz 2014; Marguin 2015; Siemer and Matthews-Hunter 2017; Wojnar 2017; Valli 2021).

The specific situation of post-socialist cities in Central and Eastern Europe offers the possibility of tracing the spatial strategies of artistic initiatives under different political, social, and economic circumstances before and after the breakthrough year of 1989.

Krakow is, next to the capital city of Warsaw, the main centre of visual arts in Poland with one of the oldest academies of fine arts established in 1818 (Romańczyk 2018). Despite being regarded as fairly conservative in terms of artistic taste, both before and after the Second World War, it was the birthplace of many movements in the visual arts (Wallis 1994). In this context, I was interested where subsequent generations of independent artistic initiatives were located during the last five decades, both within the urban structure and within the built environment. It was reflected in my interest in studying how different independent endeavours were using meanings associated with various parts of the city in their artistic practices and which were evolving during the period under study (Górka 2004; Murzyn 2006; Smagacz 2008; Zwiech 2018). Additionally, their location was put in relation to the clusters of galleries emerging after 1989, when both non-profit art spaces and commercial galleries were allowed to operate without political constraints (Działek 2021). It was interesting to determine whether the main oppositions inherent in the field of art, between heterodox and autonomous vs. orthodox and heteronomous initiatives (Mangset 1998; Lizé 2010; Picaud 2017), were reflected in their spatial distancing while also taking into account the post-socialist context of the city.

3. Material and Methods

This study is a part of larger research endeavour that aimed to map all private contemporary art galleries in Krakow (both independent, non-profit art spaces and commercial art dealers, no matter the name they were using—a ‘gallery’, a ‘space’ or another). Initially it covered the period after 1989, but later it was extended to the pre-1989 era back to the 1970s when the first such an artistic initiative was established in Krakow (Działek 2021). Various data sources (see Rius Ulldemolins 2012; Debroux 2017; Molho and Sagot-Duvauroux 2017) were used to create a database of art galleries and art spaces: printed and online editions of local newspapers and weeklies, art and cultural magazines, art portals, gallery websites and social media profiles, artists’ websites, and other written materials on art galleries in Krakow and Poland. Personal visits of more recent art initiatives were conducted between 2015 and 2019, especially during annual gallery weekends known as Krakers (which were later transformed into a gallery week) (https://cracowartweek.pl/, accessed on 5 May 2021).

In the second stage, a collection of press and internet texts published between the 1970s and 2019 was compiled and later analysed by the author. Both the database of art spaces and the collection of excerpts allowed a subset of independent art spaces, understood as non-public, not-profit art venues with an alternative programming (at least at the beginning of their operation) to be identified. Later, key independent art spaces were selected based on the number of references in printed and online art media and on views expressed by art critics.

The qualitative content analysis of texts allowed insight to be obtained into the observations and comments of art journalists and gallery owners about the presence and activities of independent art spaces in different parts of the city through five decades. It allowed opinions and emotions expressed at the time when art spaces were opening, relocating or closing down to be interpreted in the context of reconfigurations of the field of visual arts and transformation of the urban space in different quarters of Krakow. In particular, it gave an insight into the individual and collective spatial strategies (location within the urban structure and within the built environment) of independent art spaces in relation to more recognised private and public art institutions representing orthodoxy and heteronomy in the field of art.

4. Findings—Four Stages of Spatial History of Independent Art Spaces in Krakow

4.1. Before 1989—Marginal Art Spaces within the State-Controlled Artistic Landscape

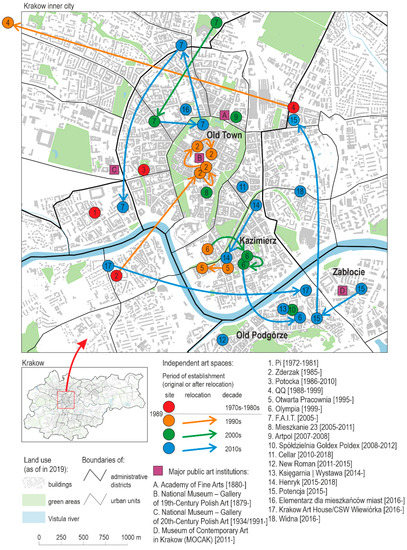

In the 1970s and 1980s, independent, illegal, or semi-legal artistic initiatives, from the point of view of the communist authorities (see Marguin 2015), operated on the outskirts of the historic inner city, usually well-hidden and known to dissident art enthusiasts. Krakow is credited with housing the first private, non-profit art gallery in post-war Poland. The Pi gallery was established in 1972 by Józef Chrobak and Maria Anna Potocka in their flat in a district behind the second inner-city ring road, and it operated until 1981 (Figure 1) (Guzek 2012). In 1986, Potocka founded another gallery, named the Potocka gallery after her, a bit closer to the Old Town in the annexe of a tenement house about 800 m from the Main Market Square. At the time, she worked as an appraiser in the state-owned art trading company and had wanted to create a museum of contemporary art based on her collection. She failed to convince the city authorities to go ahead with this idea and focused on running her own independent gallery for almost a quarter of a century until 2010 when she eventually became the director of the then established MOCAK (Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow) in the Zabłocie district.

“It was then that she came up with the idea of establishing the Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow. The management of Desa [the state-owned art trading company] then offered to help her—if she found a place, she would get the money to maintain the building. It took two years to search for a place for a museum. In the end, Maria Anna Potocka realised that nothing would come of it. So she decided to set up a gallery at Sikorskiego Square, which still exists today. It consists of two or three small rooms in an annexe.”2

Figure 1.

Locations and relocations of independent art spaces in Krakow’s inner city. Source: own study.

A year earlier, in 1985, the Zderzak gallery was inaugurated in the attic of a house in another marginal district, this time on the other side of the river (gallery is still in operation as of 2019). This “gave the opportunity to present (and discuss) the achievements of young, and by all means rebellious, painters called at that time ‘the wild ones’”3. In 1988, the QQ gallery (active until 1999) was founded by another group of young artists in the basement of a tenement house on the opposite side of the inner city.

“We wanted to deal with contemporary art. Meanwhile, there was simply no such art around us. The Poland of the late 1980s was a gloomy, grey, and dark country, the property of a characterless general Wojciech Jaruzelski. To exist, you had to build your own world.”4

Independent art spaces in the last decades of the communist regime were positioning themselves in political and artistic, and at the same time spatial, opposition to galleries located in the Old Town, including several run by the dominant state-owned art trading company, others managed by legal art associations, and finally the first private art dealerships that were allowed to operate in the 1980s. For those observing the art world at the time, their marginal horizontal and vertical locations (see Nae 2018) together with the unusual rhythm of their functioning, distinct from those of traditional institutions, designated their clearly antagonistic heterodox artistic position toward the ‘old’ centre. Their interiors also conveyed a significant aesthetic and artistic declaration.

“Where are these Zderzak meetings held? In Krakow, in Dębniki. Not elsewhere. New Art in Dębniki? … Because in Krakow … if something can happen, it should only be on the left bank of the Vistula. And then suddenly there are some artistic ‘clashes’ on the Krakow rive droite! To make it even more exciting—Zderzak is a sui generis phantom-gallery, or more precisely a gallery in the attic. Three or four days of the show and we are rolling up the clobber. Everything is back to normal. Laundry can be hung up again. Thanks to this however—but not only this—there is a salutary lack of routine, an aura of lively improvisation. Zderzak [literally ‘Bumper’]—as the name suggests—wants to be an independent, lively and open gallery. A place of artistic confrontation. Where, apart from—why not—compliments, opinions are also exchanged, and invectives are thrown.”5

“It is located almost in the city centre, in the district at the back of the train station, on the road leading to the cemetery, in a typical bourgeois tenement house. Every human habitat must have marginal places, a kind of rectum. These include the cellars and the QQ Gallery found its place right in the basement. When it was renamed a gallery, it underwent only minor cleaning, without changing its appearance or smell. The aesthetics of the gallery remained the aesthetics of the basement. The idea of the gallery is closely related to the nature of the place and the way it functions. Its low stature refers to a specific interpretation of the understanding of the concept of art and its attitude towards the institutions administrating art.”6

4.2. After 1989—Economic-Based Opposition and the Discovery of a New Artistic Territory in Kazimierz

Along with the political and economic changes after 1989, there was a significant reconfiguration of the field of visual arts in Poland—both due to the reduction of public spending on culture and the necessity to adapt rapidly to the demanding rules of the art market (Guzek 2012; Możdżyński 2015). In the 1990s, there was a boom of new, usually commercial, art galleries that started to flourish, mostly in the Old Town. The rise in price of contemporary art and the opening of the Polish art market to foreign customers brought some art dealers substantial profits: “1990, when people from the street went in and bought paintings like pretzels, that will not return…”7. The location in the Old Town ensured the proximity to affluent residents and visitors from abroad. These galleries also referred to the connotations associated with this historic part of the city—to its prestige, traditions, and cultural heritage (see Romańczyk 2018). Hence, the most desirable premises for them were on the Main Market Square and two main streets along the so-called Royal Route (see Działek 2021). The changes of that period were evidenced tellingly by the fact that in 1990 the Zderzak gallery began its commercial activity in the Old Town, retaining however, its original non-profit exhibition space until 1994.

The founders of the QQ gallery chose a different path: to maintain their heterodox position in the field of art, they moved to an even greater distance from the central district to the attic of a single-family house located 4 km from the Main Market Square. This physical distance was to affirm their continuous strong distinction from mainstream art.

“However, its remoteness is also very meaningful for a gallery that presents art as very distant from what is exhibited elsewhere.”8

As the Old Town regained and strengthened its position as the artistic core of Krakow with a strong orthodox and heteronomous focus, non-profit art spaces were, in this new economic situation, not fully appreciated and actually treated with suspicion.

“True, that is non-profit, art galleries usually operate in not the best material conditions, send out unattractive invitations, and are located in not very nice premises. Because of that, it is often hard for them to gain a reputation and understanding. Their importance is inversely proportional to these external manifestations.”9

The new path was forged, however, by the next generation of art spaces that started to contend with this predominantly market orientation. They were part of the art community that in the 1990s started to intensively explore the district of Kazimierz, relatively close to the Old Town yet suffering from significant dilapidation after the communist era. It was originally a separate medieval town incorporated into Krakow at the end of the 18th century and known until the Second World War as the home of Krakow’s large Jewish community. After 1989 it became, in the Central European context, an outstanding example of the urban transformation of a neglected quarter after decades of decline (Murzyn 2006; Smagacz 2008).

However, in the early 1990s it was two commercial galleries that were the first ones probing the edges of this district. Their location was meaningful from the spatial perspective as their sites were next to the main avenue (Dietla Street) which is relatively close to the Old Town (about 400-500 m). Despite this short distance, they were still perceived as risky enterprises due to the negative image of the area. Later in the mid-1990s, they were followed by a small group of art establishments that were invoking the Jewish heritage of this neighbourhood in their programming. The tragic wartime past and the decay of the quarter which followed were also drawing the attention of the independent art spaces that began to penetrate deeper into the district and, together with other alternative art establishments, started to shape its new alluring image (see Murzyn 2006). One of pioneers was the artist-run space Otwarta Pracownia (literally Open Atelier), which was established in 1995 (active as of 2019) in the premises of an abandoned store on the main street of this, then considered dangerous, district of Krakow.

“At that time [the establishment of the gallery] in Krakow, apart from large, official institutions, there were hardly any non-profit galleries. Commercial galleries have their own specifics, they are needed, but it would be terrible if they had no alternative. In the beginning, which sounds quite funny in the context of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, we were criticised a lot for this non-commercial nature. We had to explain it by ourselves. Why not commercial? The fascination with the ‘healthy and free’ market was then huge. Selfless activity seemed suspicious as a relic of communist times.”10

After two years, when the building in which it operated was returned to the pre-war owner, they moved to the premises of the carpentry shop in the yard of a tenement house on the rarely frequented outskirts of the district. At that time, there were grave doubts whether it would succeed due to its remoteness from the Old Town: “according to the common, albeit unofficial, opinion, galleries located beyond the Planty [meaning outside of the Old Town] have no chance of establishing themselves”11. Its marginal location both within the city and within the emerging art district, with low physical visibility, was a textbook example of its heterodox (low symbolic capital) and autonomous (non-profit orientation, no public support at the time) position in the field of art.

“You unexpectedly land in another dimension in which only one thing is important—art. And I would like to add that the entrance itself is not easy—you have to ring the intercom to get to the yard. (…) This non-profit gallery has just started its fourth year of operation. And what is interesting—not a single review of any exhibition has been published in Krakow during this time. (…) The silence of Krakow is even more incomprehensible that almost all the artists and people interested in the art of the end of the 20th century come to Otwarta Pracownia.”12

Art critics were pointing out the analogy between the features of the site and the neighbourhood and the art exhibited in this art space.

“Otwarta Pracownia nestled in Kazimierz, where the cheapest municipal premises could be rented for ‘free-of-charge cultural activities’. Even if it was a coincidence, it was a lucky one. Kazimierz—its less official part next to the Vistula river—is perhaps the last authentic district of Krakow. It has its own atmosphere; it has not always got the most beautiful of odours. Shabby walls, remnants of pre-war signs on plaster, neglected yards, dingy cages, suspicious alleys and nooks … A raw district, without varnish, but with character. … A yard, like many: photogenic and picturesque, but probably more burdensome for the everyday inhabitants than for the artists who are sensitive to the charm of ‘anti-aesthetics’. … A painter can see the aesthetic values of poverty, the beauty of decay, the aesthetics of neglect. Here, the poetry of art collides with the prose of life. … An overwhelming feature of the art shown here is the complete lack of coquetry, varnish—a certain severity, coarseness, and calm.”13

By the end of 1990s, Kazimierz was securing its renown as an ‘authentic’ and ‘magic’ quarter, Krakow’s Montmartre, in opposition to the Old Town, which was by then heavily commercialised.

“Kazimierz was perfect to become the city of art. Poor and ugly, deserted by the rightful inhabitants, notorious both then and now, guzzling and bastarded, it could take in artists to its filthy and vodka-stinking streets, because only they could be proud of it; for others it would be dishonourable to live here. Only this place could become Krakow’s quartier des artistes, it was a district open to change, a fabric that could be shaped, soft and malleable like clay.”14

At the turn of the 1990s and 2000s, it has grown into an emerging artistic cluster of mostly artist-oriented galleries with a strongly bohemian vibe. Józefa Street became its main gallery street with several new art spaces representing the youngest generation of Krakow and Kazimierz artists. Among them, Olympia gallery, that was established in 1999 in the neighbouring district, moved to Kazimierz in 2001, and then relocated to Józefa Street in 2005.

“Young artists, albeit with some achievements, will be able to exhibit their works there [in the Olympia gallery]; not permanently associated with any of the galleries, but full of enthusiasm. And those with whom the owner shares a generational bond and a similar way of seeing the world.”15

“For me, it is a typical gallery of this district—focused on promoting young artists, often right after graduation. Ascetic interiors, graphics, painting, and photography. Walk over here on Saturday afternoon—Olympia is where a small group of friends are sitting on the steps. And do not be discouraged by a few men standing next to the Endzior fast-food stand which is closed at this time—both groups coexist. At most, the oldest of this group will approach you slightly swaying, and politely ask for a zloty ‘for a sandwich’. It is a tradition of this place—give it, and you deserve their gratitude.”16

Kazimierz, however, was subject to gradual changes as a result of growing touristification and gentrification, culminating at the end of the 2000s and the beginning of the 2010s. The increase in rents and the loss of ‘authenticity’ had a negative impact on artists and independent art spaces. By 2005, the founders of the F.A.I.T. (abbreviation for the Foundation Artists-Innovation-Theory) gallery had already defined themselves in opposition to Kazimierz:

“This part of Krakow [north from the Old Town] is still undiscovered, neutral. We didn’t want a gallery in a trendy place like Kazimierz.”17

However, the symbolic moment for the independent art scene in Kazimierz was the decision of the Olympia gallery, one of its anchors, to leave it in 2013.

“Olympia Gallery is abandoning its location in Krakow’s Kazimierz at 18 Józefa Street and moving across the river to Podgórze. Krakow’s Kazimierz has dashed our hopes, forever losing its opportunity for development, and Józefa Street became a route for representatives of mass tourism devouring tons of ‘zapiekanka’ fast food sandwich during the day (and at night). In addition to street food consumption, tourists are busy taking pictures and blocking pavements and streets. It’s hard to break through this crowd. Therefore, for the convenience of people who are sincerely devoted to contemporary art and ready to climb wide, if winding stairs, we are opening Olympia Gallery at 24 Limanowskiego Street in studio No. 4b. There, in a ‘homely atmosphere’, we will take refuge from the hustle and bustle of the street crowd and escape from the ‘loud, group and mass exultation’ inherent to museums.”18

By the end of the 2010s, however, there was a slow revival of independent artistic life in Kazimierz, even though in general it was orbiting towards a more market-oriented cluster of art galleries. A typical initiative from this period was the Henryk gallery, which began operating in 2015 in a flat on the high ground floor in the northern outskirts of the district, farther from what used to be its main gallery street. Despite its marginal location, it benefited from being close to both the established, old and new, poles of Krakow artistic life in the Old Town and in Kazimierz. Yet, it made little reference to the ‘magic’ allure of the district. It gained a great deal of attention in the artistic milieu, despite the fact that it was only open for art viewers on Fridays and once a month on Saturdays on the occasion of openings, while on the other days its space was occupied by a drawing school which was a source of income for the owners. During the short period of its existence, in three years, it has evolved from a non-profit art space to a more market-oriented establishment, at the same time relocating to a more central location, on the main street of the district, still with rather low visibility for passers-by.

“Henryk is a gallery, a school, a laboratory-space, a place of artistic exploration, experiments, and encounters. Located at the junction of the Old Town and Kazimierz, the space is focused on activities and creative interventions, and above all—it represents an innovative approach to financing art.”19

“The first season of our activity focused on the location and space in which we found ourselves—an apartment in a tenement house at the junction of the Old Town and Kazimierz. Virtually all projects were site-specific installations.”20

4.3. Scattered Testing Grounds in Search of a New Artistic Frontier

In the mid-2000s, the next generation of artists and art spaces was coming to the fore. They were expressing their opposition to their predecessors by opting to be called ‘project spaces’ instead of a ‘gallery’, as this type of art venue was increasingly associated with artistic orthodoxy and market focus (see Marguin 2015). In this way they were underlining their collaborative, alternative, experimental, and process-oriented nature. This antinomy was also reflected in the growing renouncing of the traditional white cube aesthetics.

“Recently, there are more and more places dedicated to art that do not trade it and avoid the name ‘gallery’. They choose various unconventional places for their activities—for instance, abandoned warehouses or their own apartments. What is the reason for this? Is it that private commercial galleries and official exhibition venues narrow the space for experiments? That they are elite? Do they set high expectations for the audience, are they closed?”21

These initiatives started to be more scattered than before within the wider inner city of Krakow as exemplified by various initiatives depicted in the following paragraphs. They were ‘pulsating’ in its different parts, appearing and disappearing, taking opportunities to use vacant premises to mark their usually short-lived presence, sometimes in already mature art districts but more often by testing the attention of art enthusiasts and attracting them to the until then ‘non-artistic’ parts of the city. Thus, they were found both in niche locations within the Old Town, in neighbouring districts, and in more distant peri-central districts. Gradually, in the 2010s, two districts on the other side of the River Vistula, that is Old Podgórze and Zabłocie, started to attract a larger number of them, and since then were considered the new frontier for the artistic development of the city.

The non-gallery character was particularly emphasised by project spaces in marginal locations in the Old Town, of which one called Mieszkanie 23 (literally Apartment 23, active 2005–2011) resonated especially strongly within the local art world. It was an initiative of a couple of artists who organised exhibitions in their flat in the “attic of a tenement house on the high third floor”22 on a side street, which, according to them, was to provide an opportunity for an authentic discussion about art “without the whole non-artistic wrapping”23, which prevailed in more traditional institutions.

“We do not want to call it a ‘gallery’, we prefer—a ‘place’ … This is our home & studio, so a place close to the natural environment in which art is created. … [We want to] Revive the conversation about art, remove barriers, transcend the institutional character created by galleries. We are not satisfied with what we watch there, so we took matters into our own hands. There will be no trade here, and instead—meetings, discussions, and lectures.”24

Another art space representative for this period was the F.A.I.T. gallery, that was trying to break away from the dominant spatial logic of art venue concentration in the prestigious Old Town or in the no-longer ‘authentic’ Kazimierz. It was established in 2005 in the building of the former freight station, about 2 km north from the Old Town, away from those two main centres of culture and night-life entertainment.

“The second gallery, away from the ‘well-seen’ locations ‘within the Planty’ area, is probably the youngest child of the Krakow art scene that swiftly rose the top. This is the F.A.I.T. gallery.”25

Its distinctness was accentuated by being the first location in post-industrial premises in Krakow that was able to provide space for larger and unexpected artworks (see Molotch and Treskon 2009).

“No trace of sleek paintings and sculptures, or ‘real’ art. The only white and bright room that looks like a typical gallery is empty. It is a sign that in the building of the former freight station there will be room for activities that are not desired elsewhere.”26

“Now it [a former freight station] has been enlivened by art that needs space and that is very comfortable in such places. There are cash desks, benches, red doors, and an upper balcony. The works presented here must somehow dialogue with this space.”27

This quasi-industrial art space turned out to be a short episode in the history of the F.A.I.T. gallery, which, despite gaining relatively high recognition, was constantly struggling with its premises. It was disappearing for some time, only to reappear in a new, unexpected location. Initially in 2007, it moved closer to the city centre, to the main street of one of the ‘good’ neighbourhoods west of the Old Town, then in 2011 to a side street on the very edge of the Old Town. In 2014, it withdrew back again to the outskirts of the inner city, and finally in 2018 it settled as a more classic white cube gallery in small premises on the ground floor in another district beyond the second ring road, but in an apparently strategic location next to the future second main building of the Academy of Fine Arts. With each relocation, it was evolving and clearly experimenting with its image and organisational strategy.

“Speaking of Krakow traditions, the F.A.I.T. gallery is back for the fourth time. It was already an avant-garde gallery located in the building of the former freight station … Later it was a slightly more well-mannered address on Karmelicka Street. Finally, it was a bar with artistic ambitions next to Planty. It was a place for artistic actions, meetings and, above all, heated discussions about art by the counter until the early hours of the morning. Now it returns again as a gallery address, hidden on the first floor of a modernist Krakow tenement house … Open every Thursday from 12 o’clock. Again, it is to be a place for young art, experiments, and non-obvious choices.”28

Another independent art space, the Cellar gallery (2010–2018), seemed to continue the glorious tradition of the QQ gallery from the 1980s. Its name (originally in English) explicitly referred to its location in the cellar of a tenement house located in a neighbourhood between the Old Town and Kazimierz. It used yet another way to contradict classic gallery aesthetics. The humid microclimate of the basement, unfavourable for artworks, was imposing an ephemeral nature on its exhibitions and an evanescent rhythm for admiring art different from month-long exhibitions in established private galleries and museums.

“One gets there, more or less ‘by chance’. … you enter the gate, then into the yard and turn right. The entrance leads to extremely steep wooden stairs. After descending the stairs, we find ourselves in a dark corridor, branching into a series of rooms, the existence of which is suggested by a faint light coming out of it. Here is the Cellar Gallery: gallery-cellar. … So far, this place is making dreams of a non-gallery gallery, of ‘something completely different’ come true. It adapts the space that used to fulfil a diametrically different function. On the other hand, it turns inside out the post-traditional understanding of a gallery space—illuminated, with white walls (a white cube). However, the idea behind this space is rooted in—as it should probably be called—pragmatism: paintings cannot hang in the Cellar Gallery for more than one night, because the humidity here causes the paint to run off the canvases. Being aware of its ephemeral nature and of the general inaccessibility of this space leads two elements, Time and Place, to merge to create a unique experience.”29

Independent initiatives were also emerging north of the Old Town, next to the main building (opened in the 1880) of the Academy of Fine Arts. Some of them, such as the Artpol gallery (2007–2008), were founded by its students or graduates who were looking for a place to present their work outside the walls of this respectable, but rather conservative institution.

“We want to show that in Krakow it is possible to present quality contemporary art, without entering into any social cliques or bureaucratic rules or bans—says Jan Plater-Zyberk, one of the founders of Artpol, and also the owner of the 80-m, white-painted space in the basement of a tenement house … However, we will not sell the works that are exhibited because we were not established to earn money on art, but to present it … So far, the area near the train station has not abounded in cultural institutions. Now that may change, because the Artpol gallery, located near the base of the Academy of Fine Arts, is the dreamed-of harbinger of change in this part of the city.”30

Another non-profit project space in this neighbourhood, Elementarz dla mieszkańców miast (literally Primer for City Dwellers, opened in 2016) uses equally marginal space.

“Our base is … the attic and the basement, where we organise artistic events as regularly as possible with the participation of artists (those from visual arts as well as those focused on music or film) interested in contemporary urban culture and its connections with current political theory or cultural studies. Regardless of the intellectual inspirations—their extent or complexity—in this special place which we have taken under our wing in the centre of old Krakow, we want, however, to focus on the practices of everyday life.”31

In the more remote inner-city districts, there were also other, more isolated art spaces that were occupying underused premises. However, they were not followed by other initiatives and did not gain a critical mass. One of the areas for ‘testing’ new art territory for experimental venues was the former working-class neighbourhood east of the railway line, with Widna gallery being a good example (since 2016). Another art collective, Krakow Art House, was around the same time occupying a surprising site in a villa awaiting renovation in the more bourgeois district of Dębniki. They had to leave, as foreseen from the very beginning, and its members moved to the up-and-coming district of Old Podgórze with a new label of CSW Wiewiórka (ironically mocking in this way the typical names of public art institutions with their facetious Squirrel Centre of Contemporary Art).

“Krakow Art House is an artist-run independent art/cultural space located in the heart of Krakow. … Nowadays it functions as the home of local artists and activists involved in diverse activities. A shared space for living and art making, it makes room for cultural productions that bridge the building to the surrounding city areas. And as such it acts as a basis for alternative possibilities to dominant social, cultural and political consensus. Krakow Art House is a friendship based collective that evolved into a think tank. Through the course of five years it sheltered actions that ranged from visual art exhibitions, dance performances, community-oriented events and building workshops.”32

4.4. Old Podgórze and Zabłocie—‘History Repeating Itself’ on the Other Side of the River

Although the first gallery in the Old Podgórze district, on the other side of the Vistula river from Kazimierz, has since 1997 been the Starmach gallery, one of the leading commercial galleries in Poland, it was for a long time a cathedral in the artistic desert. It was not until a decade later, when Spółdzielnia Goldex Poldex was established in 2008, when eyes started to be turned towards this neglected part of the city. Its name, a ‘cooperative’, reflected its heterodox artistic nature and social orientation at the same time. It was an example of the self-organisation of an autonomous art collective opposing the system of cultural institutions benefiting from public support. It was also a forerunner of other independent art spaces in this neighbourhood that were creating and displaying radical and socially engaged art.

“The pragmatism of bureaucrats who use public money to support projects such as ArtBoom [a street art festival in Krakow from 2009 to 2015] is only a reflection of the pragmatism of the dominant social class—the bourgeoisie. And as a result, the art that is created is bourgeois, elitist, banal, and boring.”33

Its location was a result of the financial constraints faced by its creators that were not able to freely choose a place in the city. Despite their antagonistic relation to mainstream art, they wanted, however, to maintain a relative proximity to the central artistic clusters. At the same time, from its inception, they were already expressing awareness of the potential negative impact of its presence on the gentrification of the district that became an important topic of other local artists and art spaces in the next decade.

“It is not that I believe in the utopia of ‘community action’ and regret that we are not able to implement it. We have never even tried to act in that way. The objective truth remains, however, that Goldex is situated in a rather poor part of Krakow’s center (Old Podgórze), where mainly the urban proletariat lives, and our activity is simply the avant-garde of gentrification. In this respect, we are a victim of the economic base, which everywhere determines a similar mechanism of a socio-urban transformation: we opened Goldex where it was cheap, and at the same time close to the centre. We would not be able to operate anywhere else, because we cannot afford the high rent, and nobody would like to go to Nowa Huta [post-socialist district far from city centre]. It is true that we did not try to reach our neighbours in any particular way, but we did not want to exclude them in advance. In practice, the posters of our events, which we sometimes hang on the door of the tenement house in which Goldex is located, are immediately torn off by the residents themselves.”34

This was especially witnessed in the post-industrial part of Old Podgórze, in Zabłocie, where pre-war and post-war factories, warehouses, and office buildings were redefining its functions during the tumultuous period after 1989 when state-owned companies were reducing their activities or relocating out of the inner city (Zwiech 2018). At some point of time in the 2010s, artists invested in some of them that they were using as studios, and later in some cases transformed into vibrant art venues. It happened simultaneously with the opening in 2010 of the MOCAK museum of contemporary art in this very district that reused the building of the famous Schindler’s factory, with Anna Maria Potocka, esteemed gallery promoter, as its director.

The history of Zabłocie art scene is reflected in the spatial history of one of the leading non-profit galleries that originated from this district, the Potencja gallery, established by three young painters. It made its debut in “the Telpod building, a former electronic plant in Zabłocie, a mecca for independent initiatives in Krakow”35, where premises were rented by artists, art students, and art collectives as studios and exhibition venues.

“It was a six-story industrial building in which we had our studios. Like many other artists from Krakow. … Close to MOCAK in Zabłocie. … We received awards at painting competitions, but nobody was really interested in what we were doing. They were ignoring us a bit. Establishing a gallery meant getting a toehold in the art world. We decided that if we do not have a gallery, we will create our own one.”36

From the beginning, it was planned to be a ‘mobile’ art space: “The plan was that the Potencja gallery was to wander from place to place. We did not want a permanent site”37. It relocated, however, to a more stable location in Old Podgórze, this time on the ground floor with a storefront, but in a rather neglected one-story building on a side street with workshops as neighbours. However, its owners complained about the separation of the art gallery from their studios, and as they relocated their place of creation to a district next to the railway station, they decided to ‘take’ their gallery with them.

“Then we started to rent space on Rakowicka Street. Apart from our three studios, there is an old kitchen in the middle. We made a gallery there.”38

Throughout their short history (since 2015) and numerous relocations, they maintained the non-profit and artist-oriented profile of their gallery.

“It was the first time we sold a work of art as a gallery, although we don’t normally do that. We don’t want to take a percentage … We don’t want to get rich from artists. Our greatest capital is that we do things together. … It is great to provide visibility to people who are not present in the art world and who deserve it.”39

The Zabłocie experiences of the Potencja gallery well represent the short-lived history of many artistic initiatives in this neighbourhood. The Telpod building, where it was based at the beginning, was converted into a private student residence leaving no place for independent art. Other factory buildings were demolished and replaced by housing estates. The peri-central location of the district attracted real estate developers, whose activities, despite the arrangement of the local urban regeneration programme, resulted in the disappearance of its industrial character that was the inspiration for many local artists and a symbolic setting for many independent art venues (Hołuj 2015).

Today, there is only one alternative art space left operating in Zabłocie, the Nośna gallery. It is a survivor of a once vibrant art scene that was preserved in its margins, still distant from the large housing estate projects. Its site is again very meaningful and similar to other independent initiatives in the past—it is located next to a carpentry workshop and constitutes a part of a larger anarchist cultural centre named Warsztat (that is Workshop).

“The aim of Nośna is to promote young artists and to propagate new ideas in culture and art, with particular emphasis on engaged art and radical movements.”40

The situation is slightly different in the Old Podgórze, which, despite similar strong investment pressure, kept its status as a promising new territory for independent art spaces, some short-lived, others more stable. One of early initiatives was New Roman that at the beginning of the 2010s was operating for several years in an apartment in one of the side streets.

“Gallery? Studio? Collective? Neither of these terms fully fits, considering that we did not want to create a specific place. (…) we wanted to create a situation in which ideas create work and work gives rise to new ideas. We wanted to design our own space where we will inspire each other, exchange ideas, and implement them through joint work.”41

A more recent endeavour, Księgarnia | Wystawa (literally Bookshop | Exhibition) features a unique profile, yet one in line with the youngest, socially engaged generation of art spaces in Old Podgórze. It is part of a network of artistic and social collaboration with communities from the Global South, from Kenya and Indonesia. Surprisingly, it is one of a few non-profit art spaces to operate on the ground floor with large storefronts.

“This transcontinental exchange and cooperation between artists and viewers, social and art activists allows us to look for new ways of communication between the Global South and the Global North. … By sharing their art, they not only speak out on the problems of modern times that are important to us, but also by bending the universal model of capitalism, they co-finance and co-create artistic ventures. Often artistic projects take place simultaneously in two distant places, or they start in one place to be continued in the other. Acting at the interface of cultures is not only a political declaration but also breaks monolithic and selfish thinking about the identity of our own cultures, nations, and states. We consider it essential to give people from different latitudes the same opportunity to enjoy and create art. We believe that joint creation changes not only local worlds, but can change the whole reality.”42

5. Discussion and Conclusions

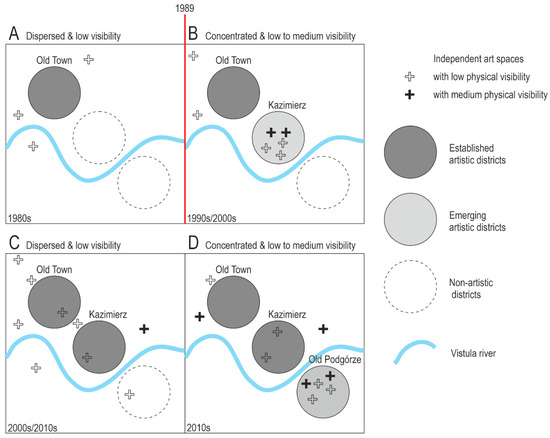

The spatial history of independent art spaces in Krakow from the 1970s until the 2010s reflects the cyclical nature of successive artistic generations and their relations with the changing urban landscape. Each of them was to some extent trying to use and co-create meanings associated with different parts of the city to distinguish themselves from previous artistic groups and to build their distinctive symbolic capital in the long run (see Valli 2021). They reacted and adapted to the opportunities and constraints that they encountered in different periods, those of a political nature before 1989 and economic after 1989, that were shaping the spatial logic of the art system. Their role could be interpreted as ‘testers’ of the new frontiers of artistic endeavours. When they were successful, it resulted in a clustering of a larger number of independent initiatives where they stimulated each other and cross-fertilised in the buzz-rich milieu (see Działek and Murzyn-Kupisz 2021).

Before 1989, the few independent art spaces were operating under completely different political and economic circumstances. Due to their illegal or semi-legal character, they were adopting the most marginal locations scattered outside of the city core with low physical visibility, as opposed to the legal, and more or less strictly controlled, public and private commercial institutions in the Old Town (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model of the spatial history of independent art spaces in Krakow. Source: own study.

The post-1989 political and economic transition brought about the development of the previously restricted art market, with a large number of commercial galleries establishing themselves, mostly within the Old Town. In the second half of the 1990s a critical mass of new generation artists emerged, creating an area of concentration of bohemian artistic initiatives in the neglected district of Kazimierz. They were using the genius loci of both the rediscovered pre-war Jewish heritage and the anti-aesthetic aura of this neighbourhood, perceived as ‘bad’ and dangerous due to its post-war decline. Its authenticity contrasted with the ongoing commercialisation of the Old Town. It was offering a more varied range of spaces for various transgressive artistic practices as opposed to the more bourgeois and tourist-oriented art in the more homogeneous historic core.

After one decade, however, Kazimierz became the negative point of reference for another wave of early-career artists. Its increasing gentrification and touristification were leaving less and less room for independent initiatives because of economic (new commercial functions, higher rents) and symbolic (loss of authenticity) reasons. They were forced to test, usually with no followers joining them, various scattered sites both in more established artistic quarters, in their niches in side streets, on higher floors, in cellars and attics, but more often in other parts of the larger inner city, in areas not associated with the consumption of art.

Again, with time they appeared to cluster in the working-class district of Old Podgórze and its post-industrial part of Zabłocie, located on the other side of the river across from Kazimierz. This area was offering relatively less expensive, underused premises and, what is also important, a thick layer of meanings associated with its social and industrial past. This part of Krakow, an independent city until 1915 which boasted a strong local identity, helped also in building the image of its growing art community. In the 2010s, it became a new artistic ‘promised land’, although the cycle of unfavourable changes for the cultural producers was even faster, with the important role of real estate developers in transforming the district for the needs of the new middle-class residents.

This poses a question about the future of independent artist-oriented endeavours in these neighbourhoods and in Krakow in general. Will they become dispersed again, or maybe a new cluster will emerge confirming the cyclical patterns of their spatial history in the previous decades. Predictions are not easy at present as the pandemic situation has ruptured the functioning of the city, including its art world. Uncertain prognoses of the post-pandemic situation suggest, however, that independent art spaces can take advantage, even if temporarily, of the troubles of the tourist sector, which has dominated the landscape of the historic city centre before pandemic (see Murzyn-Kupisz and Hołuj 2020), especially in the Old Town and Kazimierz, and now invest in vacated premises (see Grochowicz 2020), including those with higher physical visibility.

Five decades of the spatial history of independent art venues in Krakow indicates that, regardless of the period, they occupy similar liminal spaces (see Nae 2018). Sometimes they operated in established centres of orthodox and heteronomous art, in districts considered ‘good’ and bourgeois, but in this case, they were occupying, almost without exception, hidden niches within buildings. More often, however, they were located farther from these quarters, in rather neglected neighbourhoods generally considered ‘bad’, combining distance from the mainstream artistic core with equally low physical visibility, with some exceptions of medium physical visibility (ground floors with storefronts in a few cases, but never on the main streets). Site-specific aesthetics of cellars, attics and flats re-used for artistic purposes were prevailing over white cube interiors typical of commercial premises used by professional art dealers (see Debroux 2017). No matter the period or location within the city, they often incorporated their distinct, specific sites into their artistic practices (e.g., cramped attics used by the Zderzak gallery in the 1980s/1990s and Elementarz dla mieszkańców miast in the 2010s, damp cellars occupied by the QQ gallery in the 1980s/1990s and the Cellar gallery in the 2010s)—they become a pretext and a context for the cultural production and consumption, and as such become a vital part of the unique experience for art viewers (see Rius Ulldemolins 2012; Vickery 2014).

Independent art spaces used, both before and after 1989, private apartments and also cellars or attics owned by their founders. After 1989, they benefited from the possibility of the temporary use of underused premises in the era of dramatic post-socialist economic transformation; at first, these were service outlets, such as traditional crafts, disappearing from the city centre, later industrial sites on the edges of the inner city, from which, under new economic conditions, industry was moving further out. It resembles similar processes observed in Western cities (see Debroux 2017); however, in the case of post-socialist cities they were delayed and often more accelerated. In the long run, independent art venues constituted a more fluid rather than a fixed element of the urban space (see Gibson 1999; Adamek-Schyma 2006; Tironi 2012). They were often short-lived, used interstitial, ‘meanwhile’ locations. They were pulsating, appearing and disappearing, relocating from one place to another, often playing the role of urban pioneers. Their temporality was in some cases reflected in the ephemerality of exhibitions, after which their sites were quickly restoring their non-artistic appearance. Their imaginative spatial and temporal practices could be recognised as another symptom of their “hybrid and adaptive” (Blessi et al. 2011, p. 143) artistic and organisational strategies.

All those elements combined (usually a marginal location within the urban structure and within the built environment, site-specific aesthetics, meanings associated with neighbourhoods and sites, the temporary nature of many endeavours) were in line with their heterodox nature. In the long term, they were attempting to exploit the aura of authenticity and transgressiveness and convert it into symbolic capital within the field of art. Only a few of them were successful enough to transform into more orthodox and heteronomous forms and gain more longevity and a stable spatial position. The fluid nature of most of them was important in exploring new frontiers both in art and in urban space, to develop an artistic language of new generations that were drawing inspiration and experience from different urban settings, as was well shown in the case of the Krakow artistic landscape during the last five decades under different political and economic contexts during the communist era, the early post-socialist transition stage, and then neoliberal urbanism. The nature of post-1989 processes and observed interconnections between the reconfiguring field of visual arts and urban transformations is similar to that of those observed in Western art metropolises, although modified by specific features of the post-socialist urban landscape. The pandemic and post-pandemic situation reopens this field of study and offers an even more interesting perspective of uncovering how artists and art spaces adapt to this unprecedented social, economic, and urban challenge, whether they draw from past experience or forge new, imaginative forms of presence in the city.

Funding

This research received no external funding except for the initial mapping of artistic activities conducted in 2016 that was part of a research funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant no. UMO-2012/05/E/HS4/01601. This article is made open access with funding support from the Jagiellonian University under the Excellence Initiative–Research University programme (the Priority Research Area Heritage). This article was proofread thanks to funding support from the Jagiellonian University under the Excellence Initiative–Research University programme (the Priority Research Area Heritage).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | There are art spaces that represent other combinations within the field of art, for example, privately-owned non-profit exhibition space of traditional art (orthodoxy and autonomy) or the public art gallery promoting ‘young’ art (heterodoxy and heteronomy), although the main line of antagonism within the field of art runs between heterodoxy and autonomy vs. orthodoxy and heteronomy. Hence, in this paper, independent art spaces representing heterodoxy and autonomy were chosen because of their crucial transformative role in the field of art. |

| 2 | Bik, Katarzyna. 1994. Trzeba tylko wymyślić formułę. Gazeta Wyborcza. Gazeta w Krakowie 205: 5. |

| 3 | Porębski, Mieczysław. 1997. Galerie Krakowa. Tygodnik Powszechny 11: 13. |

| 4 | Guzek, Łukasz. 2004. Masz tyle, ile samemu sobie stworzysz. Galeria QQ. ArtPapier. Available online: http://www.artpapier.com/pliki/archiwum_czerwiec_04/recplast/galeria%20qq.html (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 5 | Baranowa, Anna. 1987. “Zderzak” i nowa sztuka. Res Publica 1: 134–135. |

| 6 | Guzek, Łukasz. 1993. Katalog. Poznań: Międzynarodowe Centrum Sztuki. Available online: http://www.doc.art.pl/qq/hispl.htm (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 7 | Małkowska, Monika. 1993. Krakowski spleen. Życie Warszawy 40: 5. |

| 8 | Górecki, Paweł. 1995. Poza magazynem sztuki. Gazeta Krakowska 98: 14. |

| 9 | Potocka, Maria Anna. 1991. Galerie niekomercyjne. Gazeta Wyborcza 220. Weekend 15: 14. |

| 10 | Z Jerzym Hanuskiem rozmawia Monika Branicka. 2005. Available online: http://www.otwartapracownia.com/teksty/teksty/009_pol.html (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 11 | Czerni, Krystyna. 2000. Otwarta Pracownia albo OFF na Kazimierzu. In Kraków w Opończy Edited by J. Boniecka. Kraków: SDP. Available online: http://www.otwartapracownia.com/teksty/teksty/004_pol.html (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 12 | Bartkowicz, Monika. 1999. Otwarta Pracownia. Dziennik Polski 41: 10. |

| 13 | Czerni, Krystyna. 2000. op. cit. |

| 14 | Grzywacz, Zbylut. 2001. Mój Kaźmirz. Przekrój 10: 52. |

| 15 | Frenkiel, Monika. 1999. Trochę fermentu. Gazeta Wyborcza. Gazeta w Krakowie 148: 9. |

| 16 | Trasa 013y. Available online: http://www.kazimierz.com/index.php?t=przewodnik&t2=trasa_013y (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 17 | (TYM). 2005. Dworcowe życie po życiu. Dziennik Polski 264: 6. |

| 18 | Galeria Olympia w nowym miejscu.Artidomowo 8.X–29.XI.2013. 2013. Available online: http://www.olympiagaleria.pl/pl.artidomowo.html (accessed on 7 April 2020). |

| 19 | Henryk. 2016. Available online: http://cracowgalleryweekend.pl/galerie-2016/henryk/ (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 20 | Dzwonkowska, Zuzanna. 2017. Efekt Henryka. Available online: http://magazyn.o.pl/2017/aleksander-celusta-mateusz-piegza-zuzanna-dzwonkowska-efekt-henryka/#/ (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 21 | Bik, Katarzyna. 2005. Nowe miejsce sztuki. Gazeta Wyborcza. Kraków 291: 7. |

| 22 | Morawetz, Dorota. Mieszkanie-galeria. Weranda. Available online: https://www.weranda.pl/domy-i-mieszkania/stylowe-i-przytulne/mieszkanie-galeria (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 23 | Mieszkanie 23. Available online: https://www.sztukpuk.pl/archiwum/assets/galerie/mieszkanie23.htm (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 24 | Bik, Katarzyna. 2005. op. cit. |

| 25 | Gazur, Łukasz. 2007. Subiektywny przewodnik po galeriach krakowskich. Gazeta Antykwaryczna 3: 53. |

| 26 | Bik, Katarzyna. 2005. Jak w komisariacie. Gazeta Wyborcza. Gazeta w Krakowie 248: 4. |

| 27 | (TYM). 2005. op.cit. |

| 28 | Gazur, Łukasz. 2014. Do czterech razy sztuka. Dziennik Polski. Available online: https://dziennikpolski24.pl/do-czterech-razy-sztuka-zdjecia/ar/3677104 (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 29 | Ruszało, Monika. 2008. W piwnicznej izbie. ArtPapier 101. Available online: http://artpapier.com/index.php?page=artykul&wydanie=55&artykul=1239 (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 30 | Romanowski, Rafał. 2007. Przy ulicy Zacisze powstaje nowa galeria. Gazeta Wyborcza. Available online: https://krakow.wyborcza.pl/krakow/1,35796,4304971.html (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 31 | Elementarz dla mieszkańców miast. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/elementarzdlamm/ (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 32 | Krakow Art House Available online: https://www.facebook.com/pg/krakowarthouse/about/?ref=page_internal (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 33 | Sowa, Jan. 2009. Goldex Poldex Madafaka, czyli raport z (oblężonego) Pi sektora. In Europejskie polityki kulturalne 2015. Raport o przyszłości publicznego finansowania sztuki współczesnej w Europie. Edited by M. Lind and R. Minichbauer. Warszawa: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, p. 24. |

| 34 | Sowa, Jan. 2009. op. cit., p. 26. |

| 35 | Plinta, Karolina, Piotr Policht and Jakub Banasiak. 2016. Najciekawsze młode galerie w Polsce. Szum. Available online: https://magazynszum.pl/najciekawsze-mlode-galerie-w-polsce/ (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 36 | Mazur, Adam. 2019. Pot. Rozmowa Karoliny Jabłońskiej, Tomasza Kręcickiego i Cyryla Polaczka. Postmedium. Available online: http://postmedium.art/pot-rozmowa-karoliny-jablonskiej-tomasza-krecickiego-i-cyryla-polaczka/ (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 37 | Ibid. |

| 38 | Ibid. |

| 39 | Ibid. |

| 40 | O Nośnej. Available online: http://nosna.pl/o-nosnej/ (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 41 | Otwarcie przestrzeni New Roman. 2011. Available online: https://cargocollective.com/newrmn/New-RMN-Otwarcie (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

| 42 | Sztuka. Available online: http://www.pamoja.pl/sztuka (accessed on 5 May 2021). |

References

- Adamek-Schyma, Bernd. 2006. Les géographies de la nouvelle musique électronique à Cologne. Entre fluidité et fixité. Géographie et Cultures 59: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batia, Sharon. 1979. Artist-run galleries—A contemporary institutional change in the visual arts. Qualitative Sociology 2: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessi, Giorgio Tavano, Pier Luigi Sacco, and Thomas Pilati. 2011. Independent artist-run centres: An empirical analysis of the Montreal non-profit visual arts field. Cultural Trends 20: 141–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2016. The Rules of Art. Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bystryn, Marcia. 1978. Art galleries as gatekeepers: The case of the abstract expressionists. Social Research 45: 390–408. [Google Scholar]

- Chełstowska, Agata. 2009. Pożywna inność. Warszawska Praga i gra w polu sztuki. Konteksty 1–2: 174–84. [Google Scholar]

- Colomb, Claire. 2012. Pushing the urban frontier: Temporary uses of space, city marketing, and the creative city discourse in 2000s Berlin. Journal of Urban Affairs 34: 131–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroux, Tatiana. 2017. The visible part: Of art galleries, artistic activity and urban dynamics. Presentation and first results of a research project. Articulo. Journal of Urban Research 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Działek, Jarosław. 2021. Geografia sztuki. Struktury przestrzenne zjawisk i procesów artystycznych. Kraków: Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ. [Google Scholar]

- Działek, Jarosław, and Monika Murzyn-Kupisz. 2014. Young artists and the development of artistic quarters in Polish cities. Belgeo 3: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Działek, Jarosław, and Monika Murzyn-Kupisz. 2021. Negotiating distance to buzz as an important factor shaping urban residential strategies of artists. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Chris. 1999. Subversive sites: Rave culture, spatial politics and the internet in Sydney, Australia. Area 31: 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górka, Zygmunt. 2004. Krakowska dzielnica staromiejska w dobie społeczno-ekonomicznych przemian Polski na przełomie XX i XXI wieku. Kraków: Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Neil, and Gerry Mooney. 2011. Glasgow’s new urban frontier. ‘Civilising’ the population of ‘Glasgow East’. City 15: 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochowicz, Marek. 2020. Sytuacja branży gastronomicznej w pierwszych miesiącach trwania pandemii COVID-19 na przykładzie Krakowa. Urban Development Issues 67: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, Łukasz. 2012. Ruch galeryjny w Polsce. Zarys historyczny. Od lat sześćdziesiątych poprzez galerie konceptualne lat siedemdziesiątych po ich konsekwencje w latach osiemdziesiątych i dziewięćdziesiątych. Sztuka i Dokumentacja 7: 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Andrew. 2012. Art and gentrification: Pursuing the urban pastoral in Hoxton, London. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37: 226–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hołuj, Dominika. 2015. Rynek nieruchomości jako generator zmian funkcjonalno-przestrzennych na rewitalizowanym krakowskim Zabłociu. Studia Miejskie 17: 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ithurbide, Christine. 2014. Beyond Bombay art district. Reorganization of art production into a polycentric territory at metropolitan scale. Belgeo 3: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, Johan. 2014. Temporary events and spaces in the Swedish primary art market. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 58: 202–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, H. 2007. The creative economy and urban art clusters: Locational characteristics of art galleries in Seoul. Journal of the Korean Geographical Society 42: 258–79. [Google Scholar]