2. Francesco Scottivoli and Patronage at the Church of San Francesco delle Scale

On 10 January 1490, shortly before his death, the nobleman Francesco di Benvenuto Scottivoli from Ancona drew up his last will and testament before the notary Pellegrino Scacchi. Having arranged his affairs and divided his property among his heirs, Francesco turned his thoughts towards his final resting place and posthumous legacy (

Appendix A). Following the family tradition, Francesco bequeathed his body to be buried in the church of San Francesco delle Scale in the family tomb that was located at the convent cloister and bore the Scottivoli coats of arms. The tomb must be the one described by Giovanni Pichi Tancredi in the late 17th century as being located “in the second vault, on the left from the entrance to the cloister” (“Nel secondo volto [à mano manca nel entrare del claustro] S. Philippi Benvenuti de Scotivolis”) (Pichi Tancredi, fol. 130

v). Filippo di Benvenuto was in all probability one of Francesco’s brothers, as we shall see further down. The Scottivoli family tomb is also mentioned in 1765 by Damiano Fillareti and 1782 by Pompeo Compagnoni (“[…] dal sepolcro della casa Scotivoli Patrizia Anconitana, esistente nella chiesa di S. Francesco de’ Minori Conventuali di Ancona, cioé nelle mura esteriori verso la parte del chiostro” [from the sepulcher of the patrician house of Scottivoli from Ancona, existing in the church of Saint Francis of the Friars Minor Conventual of Ancona, that is, in the external walls towards the side of the cloister])

Fillareti 1765, p. 12;

Compagnoni 1782, p. 392).

According to Francesco’s will, the friars of San Francesco delle Scale were also to receive a portion of the yearly revenue from his estates, on condition that they should celebrate masses in memory of the testator’s soul and the souls of his deceased family members. Last but not least, towards the end of his will Francesco Scottivoli proceeded to further establish his connection to the church and convent, by ordering his heirs and executors to have a chapel erected in his honor across or near his tomb, and have it adorned with a painted altarpiece.

Francesco seems to have had a clear vision of how his desired altarpiece should look. In his will, he left explicit instructions specifying which exact figures would be depicted in the composition, “namely the glorious and always Virgin Mary with her Son in her arms, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Cyriacus, Saint Jerome, and Saint Francis”. The main panel would be accompanied by a scabbello—in all probability a predella—featuring small figures of “the three Magi when they visited our Lord Jesus Christ and his mother the Blessed Virgin”. The task of seeing these works through to completion fell to Francesco’s four nephews, Benvenuto d’Astorgio Scottivoli, the brothers Niccolò and Benvenuto di Filippo Scottivoli, and Bartolino di Ciriaco Naffini. The four were to receive 125 golden ducats with the obligation to have the chapel, altarpiece, and scabello finished within a year from the testator’s death. Failure to do so would incur a penalty of 25 golden ducats per year, until the works would be finished as specified; any additional money resulting from a possible penalty would be spent to further enhance the ornamentation of the chapel.

Francesco di Benvenuto Scottivoli was a member of one of the most prominent houses of Ancona. The family took pride in hailing from Benvenuto Scottivoli († 1282), a friar of the Observant branch of the Franciscan order, who was canonized as a saint shortly after his death (

Saracini 1675, p. 501). Benvenuto Scottivoli served as archdeacon of the church of Saint Cyriacus in Ancona, bishop of Osimo and Governor of the region of the Marche. Francesco’s immediate family also counted several illustrious members. His brother Filippo, father of the aforementioned heirs Niccolò and Benvenuto, had gained renown as engineer at the court of Francesco Sforza in Milan, while his other brother, Astorgio, father of the above-mentioned Benvenuto, was a famous condottiero, also employed at Sforza’s service (

Saracini 1675, p. 502;

Peruzzi 1835, p. 320;

De Bernabei 1870, p. 179). Francesco himself had an important position in the local community of Ancona, holding the office of regolatore del comune, in which capacity he supervised the decoration of the ceiling of the Loggia dei Mercanti by the Florentine painter maestro Antonio, together with his father-in-law, Domenico di Lippo (

De Bernabei 1870, p. 163;

Ravaioli 1982, p. 162;

Mariano 2003, p. 116).

By commissioning a funerary monument and chapel at the church of San Francesco delle Scale, Francesco Scottivoli maintained his family’s traditional ties with the order of the Franciscan minors and honored his namesake and titular saint of the church, Francis of Assisi, all while following a patronage tradition that was well-established among the local aristocracy. Much like their counterparts in other Italian cities, Anconitan noblemen had adopted the practice of founding family chapels and altars in the city’s churches as a means of elevating their political and social prestige, as well as obtaining spiritual benefits in the afterlife. Since the Middle Ages the cathedral of Saint Cyriacus and the church of San Francesco ad Alto remained the city’s principal sites of devotion. However, during the 15th century San Francesco delle Scale grew steadily in popularity, enjoying the patronage of the most distinguished Anconitan families and attracting some of the most important art commissions of the time (Pichi Tancredi, fols. 130

v–45

v;

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 351, doc. 344).

In 1469 the nobleman Girolamo d’Antonio Ferretti had a family chapel built at the church, which was decorated in 1472 with an altarpiece by Nicola di Maestro Antonio d’Ancona (

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 352, doc. 352). Around 1481 the same painter was commissioned by another nobleman, Niccolò di Giovanni Petrelli, to paint an altarpiece for his family chapel and then again in 1486 to further decorate it with a lunette (

Mazzalupi 2008b, pp. 252–57;

2008c, p. 360, doc. 534; See also BAV, Vat. Lat. 13387, fol. 19

v). A few years later, in 1498, Giovanna, widow of Angelo Montifieri, had a chapel built in the same church, adorned with sculpted figures and scenes by the stonemasons Pietro di Stefano from Venice and Pasqualino di Giovanni from Trogir (Traù) (

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 367, doc. 655). Pietro di Stefano would return to the church of San Francesco two years later, this time to construct the funerary monument of nobleman Leonardo Trionfi (

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 369, doc. 679). Reaching its peak in the last quarter of the 15th century, this tradition of family and funerary patronage survived well into the 16th century. In 1550, for instance, the heirs of Lorenzo Todini commissioned the Venetian painter Lorenzo Lotto to create an altarpiece with the Assumption of the Virgin for the former’s funerary chapel at the church of San Francesco; the main altar of the church was also erected by the Todini family (Pichi Tancredi, fols. 134

v, 136

r; BAV, Vat. Lat. 13387, fols. 19

r, 21

r).

4. The Commission for the Scottivoli Altarpiece

While the Scottivoli chapel was probably constructed sometime between 1490 and 1500, the accompanying painted altarpiece would not be commissioned until almost two decades after Francesco’s death. Valuable evidence documenting the commission of the painting is provided in a series of contracts dating from 1507 and 1508, preserved in the State Archives of Ancona. The first document dates from 10 November 1507, on which day the heirs of Francesco Scottivoli appeared before the notary Calisto Trionfi at the palazzo degli Anziani in Ancona, promising to pay 80 golden Venetian ducats to a certain master Angelos (“Magister Angelus Nicolai greci pictor”), painter of Greek origin, at the time residing in Ancona (

Appendix B,

Figure 1). The payment concerned a panel (“unam conam seu tabbulam”) that the Greek master had agreed to paint for the altar of the Archangel (“in altare Sancti Angeli”) at the church of San Francesco delle Scale. The heirs who signed the contract were Niccolò, Benvenuto di Filippo and Benvenuto d’Astorgio Scottivoli, also acting in name of lady Antonia, widow of the fourth trustee, Bartolino Naffini, who had died in the meantime.

On the same day, Scottivoli’s heirs received a deposit of 22 ducats from one of the witnesses of the previous act, Tommaso di Bartolomeo di Ser Tommaso, in all probability used to pay master Angelos, who was now signing as a witness (

Appendix B). The second witness, Conte Ottomano Freducci, who was also present in the rest of the contracts, was the famous cartographer, active in Ancona between 1497 and 1539. Lorenzo Todini, also a witness, can possibly be identified with the aforementioned nobleman whose chapel at the church of San Francesco delle Scale was decorated with Lorenzo Lotto’s Assumption of the Virgin.

Three days after the stipulation of these two contracts, on 13 November 1507, the said master Angelos acknowledged having received the promised 80 ducats from the heirs of Francesco Scottivoli and renewed his commitment to paint a “cona” or “tabula” for the church of San Francesco delle Scale (

Appendix B). Finally, six months later, on 29 April 1508 Niccolò, Benvenuto di Filippo and Benvenuto d’Astorgio Scottivoli declared that they had received the commissioned altarpiece and released master Angelos of any obligations (

Appendix B).

At the time of the completion of the altarpiece, 18 years had passed since Francesco Scottivoli’s death. This was a substantial delay, especially considering the strict penalty of 25 ducats per year of postponement that was stipulated in the testator’s will. The reasons for this delay remain unclear, however, the price of 80 golden ducats that was set for the altarpiece suggests that the penalty was never fully imposed. In fact, if we assume that the construction of the chapel cost around 50 ducats—the standard average price for a similar work and the amount that master Matteo demanded from Francesco’s heirs (

Mazzalupi 2008c, pp. 352–53, 363, docs. 352, 360, 380, 579)—that would leave 75 ducats for the manufacture of the altarpiece, a sum which would have risen substantially in the years elapsed until its completion. One possible explanation would be that the penalty was lifted or not fully imposed in the event of the timely completion of the architectural and sculptural works.

To put the remuneration into perspective, the price of 80 ducats that the altarpiece cost was still on the high end compared to similar commissions from the same period, amounting to the cost of an average house in Ancona (

Mazzalupi 2008c, pp. 342, 344, docs. 138, 140, 179). For the sake of comparison, in 1441 Giovanni Antonio di Maestro Gigliolo da Parma was paid 100 ducats to paint an altarpiece and possibly the walls of a chapel in the church of San Francesco delle Scale (

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 343, doc. 168). Furthermore, in 1462, the Florentine maestro Antonio received 65 ducats for a painting with a predella for his patron Pietro di Dionisio (

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 349, doc. 325). In 1477 the same maestro Antonio and his son Nicola promised to paint an altarpiece for the church of San Francesco dell’Osservanza for 20 ducats (

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 356, doc. 437). Later, in 1486 the abovementioned Nicola di Maestro Antonio agreed to paint a lunette for the chapel of Niccolò Petrelli for 15 ducats, whereas in around 1496 he received 30 ducats for a painting commissioned by Angelo di Simone (

Mazzalupi 2008c, pp. 360, 366, docs. 534, 635). Additionally, in 1494, another painter, named “magister Iacobus Iohannis Lucidus” received 35 ducats for the construction of an altarpiece (

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 365, doc. 615). Few commissions resulted more expensive than the Scottivoli altarpiece, such as the one painted for Niccolò Petrelli’s family chapel at the church of San Domenico, which according to the patron’s will, cost 150 ducats (

Mazzalupi 2008b, p. 256n98). Similar or somewhat higher prices were set in Venice and other Italian centers, where renowned masters were charging from 60–100 ducats for an altarpiece, depending on size, with less popular painters demanding much lower wages (

O’ Malley 2005, pp. 131–60;

Čapeta Rakić 2019, p. 213n1).

5. Magister Angelus Nicolai Greci Pictor

Now that the legal documentation that has been discussed above has pointed out that “Magister Angelus” was commissioned to execute the Scottivoli altarpiece, the question becomes who this painter was and where his roots originated. In the earlier discussed contracts, the painter is recorded as “magister Angelus Nicolai greci”, that is, master Angelos, son of the Greek Nikolaos. The artist’s family name is not disclosed in any of these acts, nor is his place of origin, leaving only room for speculation regarding his identity. Among the Greek artists documented in the surviving sources, there is only one painter by the name of Angelos, who had a father called Nikolaos and could have been active in 1507 (

Cattapan 1968, pp. 29–46;

Cattapan 1972, pp. 202–35;

Constantoudaki 1973, pp. 291–380): Angelos Bitzamanos from Candia. Angelos Bitzamanos was first documented in 1482, when his father, Nikolaos Vitzimanos (Viçimano), a resident of Candia, signed a contract, placing young “Angelino” (“Angelinum filium meum”) into apprenticeship with the renowned Cretan master Andreas Pavias to be taught the art of painting (

Cattapan 1972, pp. 221, 224–25). The next documented record of Angelos dates from as late as 1518, when the painter was commissioned to paint a large altarpiece for the parish church of the Holy Spirit (crkva Svetog Duha) in the village of Komolac, in the outskirts of Dubrovnik (Ragusa) (DAD, Diversa cancellariae, vol. 108 (1518–19), fol. 109

v). As a result, the 36-year period between the painter’s apprenticeship in Crete and his first known commission in Ragusa remains entirely undocumented, leaving the possibility of a potential sojourn in Ancona open and making Bitzamanos a likely candidate for creator of the Scottivoli altarpiece.

Speculations aside, the key to safely revealing the painter’s identity can be traced once again in the archival sources. More specifically, in the records of another Anconitan notary, Troilo Leoni, the name of Angelos Bitzamanos (“Angelus Bizamanus”) appears on three different acts, all stipulated in Ancona during the year 1508 (ASA, vol. 165, notary Troilo Leoni, 1508). The first document dates from 10 January 1508, when “Magister Angelus Bizamanus de Creta” gave a loan of 52 carlini to the painter Johannes Boschetus from Zadar and the carpenter Andrea di Giorgio (

Appendix C,

Figure 2). This document was briefly mentioned by Marcello Mastrosanti, who read the painter’s name erroneously as “Angelo Bizantino” (

Mastrosanti 2011, p. 285). The second act was signed on just the following day, 11 January 1508, when Angelos Bitzamanos together with the aforementioned Johannes Boschetus—this time named as his associate (“socio”)—promised to execute certain unspecified painting works for three different patrons, one of whom was Niccolò Scottivoli (

Appendix D). The last series of documents dates from 9 May 1508. On that day, both of the previous contracts were cleared, and in addition, Angelos Bitzamanos appointed painter Johannes Boschetus as his procuratore, authorizing him to represent him and demand the payment of a debt owed by Benvenuto Scottivoli and Antonia, widow of Bartolino Naffini (

Appendix E). The name of Angelos Bitzamanos is also listed on the volume’s index: “Angelus Bizamanus cum Magistro Johanne pictore et socio”, “Angelus predictus cum dicto Magistro Johanne”, and “Angelus Bizamanus procuratorem in Magistrum Johannem pictorem” (ASA, vol. 165, notary Troilo Leoni, 1508).

The mention of Angelos Bitzamanos in the aforesaid 1508 documents in relation to several of Francesco Scottivoli’s heirs make it possible to safely identify the Cretan painter with “Magister Angelus Nicolai greci”, creator of the altarpiece of San Francesco delle Scale. These new sources further associate the Greek painter with the patronage of the Scottivoli family and are possibly also related to the commission for the altarpiece of San Francesco delle Scale. More specifically, two of the acts drawn up by Troilo Leoni were signed by members of the Scottivoli family: Niccolò Scottivoli in one case, and Benvenuto Scottivoli and Antonia Naffini in the other case. Since Angelos had acknowledged receiving his payment for the Scottivoli altarpiece already in November 1507, it seems unlikely that the debt owed by Benvenuto and Antonia on the 9 May 1508 would refer to the same work, which was after all delivered some ten days earlier, unless the painter demanded additional payment or in case extra works were required for the completion of the altarpiece. It is equally unclear whether the works ordered by Niccolò Scottivoli on 11 January 1508 were also related to Francesco’s altarpiece or if the possibility of an additional workload led the Greek painter to seek the assistance of his colleague, Johannes Boschetus. In any case, it is clear that the recurring involvement of Angelos Bitzamanos with several of his original commissioners indicates that the painter maintained a consistent association with the Scottivoli family, not only in relation to the altarpiece of San Francesco delle Scale, but possibly also for other individual commissions.

6. In Search of a Lost Masterpiece

As mentioned in the beginning of this article, in the late 18th century the church of San Francesco delle Scale underwent an extensive renovation, followed by the dissolution of its chapels and the dispersal of its earlier works of art, which at that time seemed outdated and unfashionable. The renovation was carried out at the plans of Francesco Maria Ciaraffoni, an architect residing in Ancona. The demolition of the altars started sometime in late 1777, to give way to Ciaraffoni’s expansion (“Nel fine dell’anno 1777 fu dato principio alla demolizione degli altari, ed altro per dar poi principio ad una nuova ristaurazione nell’anno seguente secondo il disegno del Signore Ciaraffoni Architetto dimorante in Ancona”, BAV, Vat. Lat. 13387, fol. 19

r). The older paintings were first moved to the sacristy of the church or were returned to the families to which they belonged. Only five paintings remained from the original ones, none of them dating before the 16th century (

Buglioni 1795, pp. 61–63; Albertini, 200r;

Mazzalupi 2008b, p. 261).

A casualty of this purge, the altarpiece that adorned Francesco Scottivoli’s chapel was removed from the church and has been considered missing ever since. At the church remained only the stone frame of the altar, which was detached and reused after 1777 to decorate the entrance to the adjacent ex-convent, now also destroyed (

Figure 3).

During the church renovation the coats of arms of the Scottivoli family, which were inscribed on the altar frame, were removed and replaced with those of the Franciscan order:

“La porta del convento era un altare di casa Scotivoli nella chiesa vecchia, e vi era nelle due piccole arme una torre, che poi fu convertita nell’arme di S. Francesco. La pietra si chiama de’ Brioni, ed è stata scolpita nel 1500” [The door of the convent was an altar of the Scottivoli house in the old church, and it had a tower in the two small coats of arms, which was later converted into the coat of arms of Saint Francis. The stone is called of Brioni and was carved in the 1500s] (BAV, Vat. Lat. 13387, fol. 21r).

“Due piccioli altari di pietra, ed un deposito a basso rilievo scolpiti sino dall’anno 1500 [...] furono in quella circostanza conservati per farne altro uso. [...] il migliore altare co’ pilastri a fiori e fogliami e contropilastro sostenente l’arco con gruppi di frutti egregiamente incisi da saggio seultore in quella stessa pietra di Brioni, ehe pochi anni prima avanzò, allorché si ornò la facciata e la porta maggiore, servì per porta principale del Convento”. [Two small stone altars, and a low relief deposit carved since the year 1500 [...] were preserved in that circumstance for a different use. The best altar with the pillars with flowers and foliage and the counter-pillar supporting the arch with groups of fruits excellently engraved by a talented sculptor in that same stone of Brioni, which a few years earlier adorned the facade and main portal serving as the main entrance to the Convent] (

Buglioni 1795, p. 47;

Cited in Moretti 1929, p. 75).

“Non fu sempre una porta, fu già ornamento in un altare dell’antica chiesa di S. Maria Maggiore, da cui l’anno 1777 si trasportò nell’ingresso dell’edificio, che era convento de’ frati minori ed ora è spedale degli infermi e de’ pazzi”. [It was not always a door, it used to adorn an altar of the ancient church of Santa Maria Maggiore, from which it was transported in the year 1777 to the entrance of the building, which was the convent of the Friars Minor and is now a hospital for the sick and mentally ill] (

Politi et al. 1834, tav. X; See also

Fillareti 1765, p. 12;

Compagnoni 1782, p. 392;

Mazzalupi 2008b, p. 271n156).

In the early 20th century, the convent housed the city museum of Ancona, and the frame of the Scottivoli altar was used as entrance to the museum library (

Moretti 1929, p. 75). No mention whatsoever of the painted altarpiece was made in any of these sources. But did these developments mean that the painting got irreparably lost or is there a possibility that it had survived in anonymity all along?

The answer may yet again be sought in the surviving archival and historiographical evidence. The contracts signed between the painter Angelos Bitzamanos and Francesco Scottivoli’s heirs do not specify the subject of the commissioned altarpiece, except that it would feature “certain figures”, painted according to what had been previously agreed upon between both parties (“cum certis figuris pictam iuxta conventiones inter ipsos initas”). It is reasonable to assume that Francesco’s heirs would have requested that the painter follow the instructions left in their uncle’s will, namely, to portray the Madonna and Child with saints Jerome, Francis, John the Baptist and Cyriacus, possibly together with a scabello depicting the Adoration of the Magi. As will be discussed next, the surviving sources confirm that this is indeed the case.

One of the first to record the presence of the Scottivoli tomb and altar in the church of San Francesco delle Scale was Giovanni Pichi Tancredi, writing sometime in the late 17th century. According to Pichi Tancredi, the Scottivoli altar was near the tombs of the Pici family, and in close proximity to the one of Ciriaco Massioli, as was in fact requested by Francesco himself in his will (“La sepoltura sotto l’altare à questo contiguo é de Scotivoli che dice cosi nell’Altare: Pium hoc opus cura et impensa Heredum Francisci Scotivoli absolutum est”, Pichi Tancredi, fol. 143v.) However, apart from describing the altar’s location, Tancredi’s report does not make any particular reference to the painting, save for a dedicatory inscription commemorating that the work was “accomplished through the care and expenses Francesco Scottivoli’s heirs”. The same inscription was recorded in an 18th-century manuscript mentioned earlier in this article, as being “below the so-called panel of Saint Bonaventure at the altar of the house of Scottivoli” (“Sotto il quadro detto di S. Bonaventura nell’altare di casa Scottivoli si legge: Pium hoc opus cura et impensa Heredum Francisci Scotivoli absolutum est”, BAV, Vat. Lat. 13387, fol. 20v). Given that Saint Bonaventure was not mentioned in Francesco’s will among the figures to be depicted in the altarpiece, the reference of the painting in relation to this particular saint seems rather unexpected.

More illuminating is the information provided by Marcello Oretti, who visited Ancona and the church of San Francesco delle Scale in 1777, shortly before the renovation works were initiated. According to Oretti’s account “the first painting on the right” bore Greek inscriptions and featured the Virgin with the Child, together with saints Bonaventure, Jerome, Francis, and John the Baptist (“San Francesco delle Scale […] Prima tavola a destra é greca con caratteri greci […] la tavola à destra con carateri Greci sopra B[eata] V[ergine] B[ambino] S. Bonaventura S. Girol[amo], S. Francesco, S. Gio[vanni] B[attista] S[an]to Vescovo con la croce sopra in lunet[t]e la[…]morto de[l] S[igno]re”, Oretti, fols. 340

v–41

r; See also

Mazzalupi 2008b, p. 261n155). Surprisingly, Saint Bonaventure is mentioned once again, although this time, all of the other figures described in the painting exactly match the ones that Francesco Scottivoli had requested in his will. In addition, Oretti’s remark about the presence of Greek inscriptions above the figures further indicates that the painting he saw was indeed the one executed by the Greek Angelos Bitzamanos at the commission of Scottivoli’s heirs. The inclusion of Saint Bonaventure was in all likelihood a later decision, either made by Francesco’s heirs or promoted by the friars of San Francesco delle Scale. According to Oretti’s description, the painting was accompanied by a lunette, which can also be deduced from the shape of the surviving frame. While Oretti’s notes referring to the lunette were written in haste and are largely illegible, it is likely that the subject depicted was that of the Deposition of Christ, the Pietà or the Man of Sorrows, topics frequently encountered in 15th- and 16th-century altarpiece lunettes.

The different accounts of the Scottivoli altarpiece in the archival and historiographical sources, together with the fact that the work was executed by a Greek icon painter, allow us to piece together a rather specific picture of Angelos’ composition. Even more remarkably, these sources point at a particular artwork, thus far largely elusive to scholarship, which perfectly matches the description of the “lost” painting. The artwork in question is a large “Byzantinizing” icon located at the Apostolic Palace in Vatican City, depicting the Madonna and Child with saints Cyriacus, John the Baptist, Jerome, Francis of Assisi, and Bonaventure (inv. n. 40522,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Although the icon’s provenance is not documented, in all probability it became part of the Vatican collections during the papacy of Gregory XVI (1831–46), whose cultural policy promoted the acquisition of works of Byzantine and Early Renaissance art with the intent to enrich the pontifical collections (

De Rossi 1876, p. 140;

D’Achiardi 1929;

Costanzi 2005, p. 26). With the assistance of monsignor Gabriele Laureani, prefect of the Apostolic Library, pope Gregory addressed an encyclical letter to various religious orders throughout the papal states, calling them to give away works of the so-called “primitives” in their possession that were not in use and stored in their deposits. The paintings collected at Laureani’s initiative eventually formed the nucleus of the Museo Cristiano at the Vatican Library, where the panel in question was first displayed. Indeed, the icon was first mentioned in 1867 by Xavier Barbier de Montault, who saw it at the bookbinding atelier (“atelier de reliure”) of the Vatican Library (“La Vierge et l’Enfant Jésus: à la droite du trône, S. Jean-Baptiste et S. Macaire, évêque de Jérusalem; à gauche, S. Jérôme et S. François d’Assise; au pied, S. Bonaventure, dont le nom est écrit en latin, tous les autres étant en grec. Tableau byzantin du XVe siécle”,

Barbier de Montault 1867, p. 8). De Montault identified all figures depicted on the icon save for Saint Cyriacus, whose name he misread as Macarius. During the early 20th century, the icon was kept at the deposits of the Pinacoteca Vaticana, from where it was temporarily moved to the papal private chapel in February 1923, only to be returned to the deposits later in August (

Bezzini 2010, pp. 281, 289). Subsequently, in 1991 the icon briefly appeared in an article by Marisa Bianco Fiorin, who reported seeing it at the Palazzo del Governatorato and attributed it to a Greek painter of the late 16th century (

Bianco Fiorin 1991, p. 212n14, fig. 3). The icon was later moved to the first loggia of the Apostolic Palace in 2003, after several relocations. The painting was last discussed by the author in 2007, when it was first associated with the cultural milieu of Ancona (

Voulgaropoulou 2007, pp. 174–76, n. 68, fig. 122–23).

The icon measures 178 × 160 cm and consists of three pieces of wood attached together. According to the museum’s inventory card the work was painted in a mixed technique with oil on canvas and not in egg tempera, which was the traditional medium of Byzantine and Cretan icon painting. In all likelihood, the painter became familiar with the new technique after his arrival in Italy, where oil painting was introduced during the course of the 15th century. Nevertheless, until a technical examination of the painting has been performed, it is impossible to carefully assess the artist’s use of materials and techniques, especially since the icon bears visible traces of overpainting. This is particularly evident in the background and the inscriptions, now almost illegible, as the restorer was obviously unable to understand the Greek text he was copying, therefore committing extensive spelling errors.

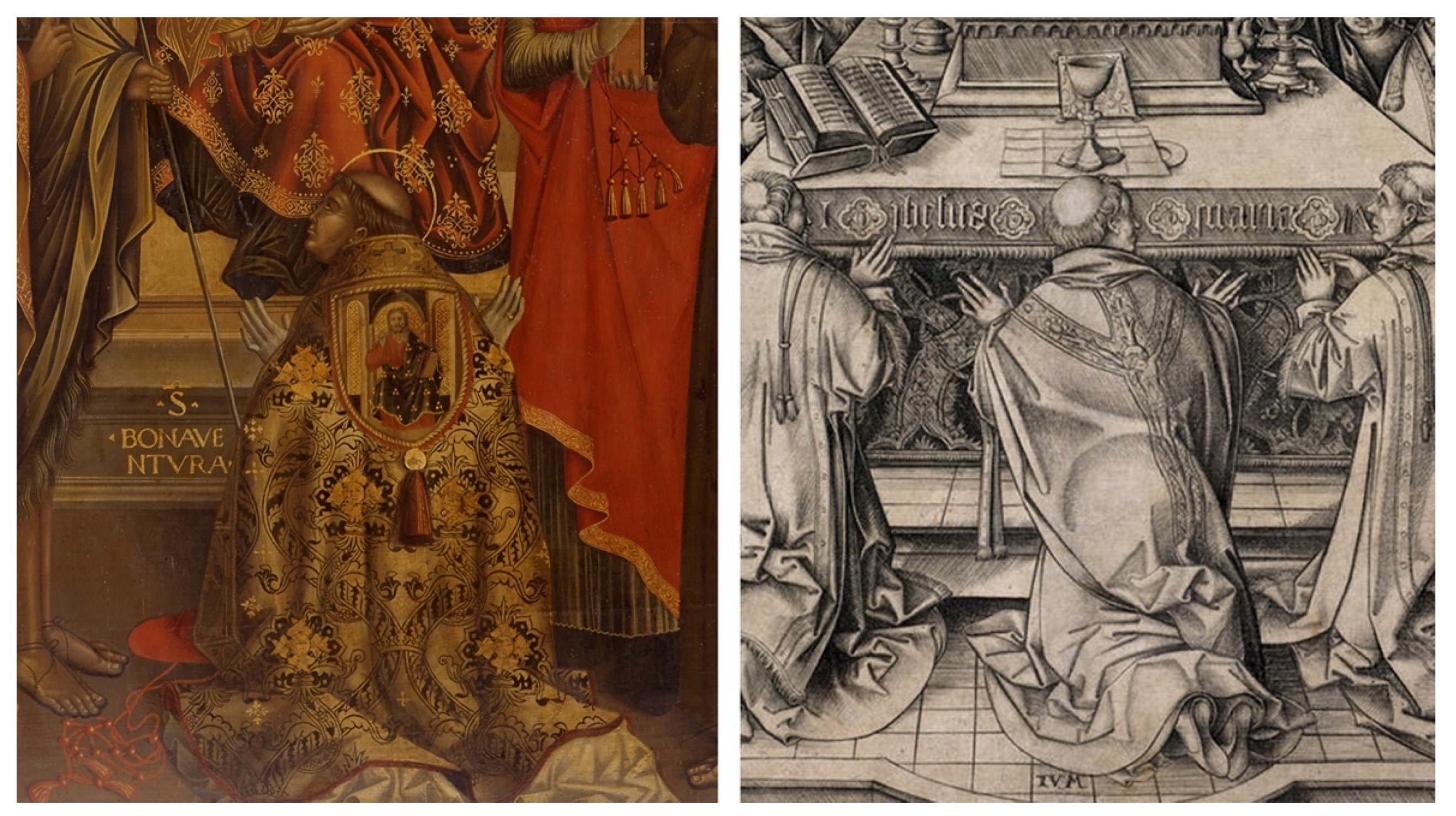

The composition follows the iconographic conventions of the Sacra Conversazione, a pictorial device that had grown immensely popular in 15th- and 16th-century Italy. In the center sits the Virgin enthroned with the Infant Jesus on her lap, surrounded by five male saints. Saint John the Baptist is placed in his usual prominent position on the Virgin’s right side, with Saint Cyriacus, the patron saint of Ancona standing next to him, depicted first from the left. Saints Jerome and Francis of Assisi stand on the Virgin’s left, while another Franciscan saint, Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, is depicted kneeling in prayer at her feet. All figures are identified by Greek inscriptions—albeit extensively overpainted—except Saint Bonaventure, who is inscribed in Latin. Greek is also the inscription of the Child’s scroll, which reads “ἐγώ εἰμι τὸ φῶς τοῦ κόσμου”, meaning “I am the light of the world” (John 8:12), a text commonly featured in Greek icons. The painting’s subject matter, including the figures requested by Francesco Scottivoli and Saint Bonaventure, whose presence is recorded in the historiographical sources, together with the use of Greek inscriptions, leave no room for doubt that this is indeed the altarpiece that once adorned the chapel of Francesco Scottivoli and was painted by the Greek artist “Angelus Nicolai”.

Although the painting bears no signature, its attribution to Angelos Bitzamanos and thus his identification with the painter of the Scottivoli altarpiece are further supported on the basis of stylistic and iconographic similarities with the artist’s other known and signed works. In particular, the figure of the Virgin shares a strong likeness with Bitzamanos’ icons from Split, Bari, and Saint Petersburg, although the latter ones were executed some 25 years later and in a much smaller, almost miniature scale (

Figure 6).

1Likewise, Saint John’s facial features and slim ascetic body have been rendered in a similar manner to that of the male figures in Bitzamanos’ triptych from Walters Art Gallery, as well as to several figures from the predella of Komolac, namely saints John, and Jerome and the beggar from the panel of Saint Martin (

Figure 7).

Saint Cyriacus, on the other hand, is portrayed as a bishop, resembling the figure of Saint Blaise from the said predella, although in a much more elaborate and detailed manner, which is easily explained by the larger scale of the composition (

Figure 8).

The floral arabesques and other decorative motifs of the saints’ robes are also typical of the Bitzamanos’ workshop, particularly the star motif depicted on the Virgin’s robes, distinctively rendered as a square inside a square (

Figure 9). The inscriptions, even though overpainted, have been copied after the original ones and display some of the painter’s common misspellings, such as the name of Saint Jerome which is spelled “ΥΕΡΟΝΙΜΟC”, in exactly the same way as in the predella of Komolac.

The Scottivoli altarpiece is Angelos Bitzamanos’ only surviving monumental work and by far his most elaborate one, created at the peak of his artistic maturity. The only other large-scale work known to have been designed by the painter, the altarpiece of the Holy Spirit in Komolac has survived only in fragments, whereas the vast majority of the icons signed by or attributed to the Bitzamanos’ workshop are mainly small-scale devotional images of industrial production, dating from his later Otranto period. Furthermore, the Scottivoli altarpiece stands as one of the few and earliest surviving examples of monumental-sized paintings created by Greek artists for Catholic patrons and displayed in Catholic religious settings. Among the few surviving examples are the early 15th-century polyptych from the church of Santo Stefano in Monopoli, now at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston; the Sacra Conversazione of Ioannes Permeniates for the Scuola dei Bottai in Venice, dating from around 1520, now at the Museo Correr; the altarpiece of the Madonna di Costantinopoli made by Donatos Bitzamanos in 1539 for the parish church of Noicàttaro, now at the Pinacoteca Provinciale di Bari; the altarpiece of Our Lady of the Rosary at the church of San Benedetto in Conversano, painted in 1572–82 by Michael Damaskenos; and lastly, the altarpiece of Our Lady of the Carmelites from Trogir, signed by Konstantinos Tzanes in 1658 (

Voulgaropoulou 2014, pp. 576–77, 590, 803, 920, with previous literature). The above works display different levels of integration of Western influences, including the use of Latin inscriptions, the adoption of Western formats, compositional devices, and painting techniques, the eclectic use of late gothic and renaissance stylistic elements, as well as the replication of Italian and Western-European iconographic models. One of the earliest cases on this list, Angelos’ altarpiece offers a rare example of the creative fusion of Western and Byzantine iconographic and stylistic traditions that would become typical of Cretan artistic production.

7. The Scottivoli Altarpiece between East and West

The Scottivoli altarpiece is a highly idiosyncratic work, ostensibly influenced by Italian art in terms of layout and iconography, while retaining the conventions of Cretan icon painting. Staging his composition as a Sacra Conversazione, Angelos departs from the austere frontal representation of Medieval and Byzantine formulas and even attempts to geometrically structure his pictorial space with the use of perspective, imitating his contemporary Italian masters. Although his application of the rules of perspective remains fundamentally flawed, Angelos manages to create the illusion of space and depth through his positioning of the holy figures, which even extend beyond the painted frame of the composition, as well as through the foreshortening of objects, such as the Virgin’s throne, Saint Jerome’s church model, and the three crosses held by saints Cyriacus, John, and Francis.

Faced with the challenging task of depicting saints of the Catholic Church, Angelos drew his iconographic models predominantly from the repertoire of the Western pictorial tradition and resorted to creative solutions with which he had become familiar in the artistically bilingual workshops of his homeland. For example, he portrayed the Virgin as Madre della Consolazione (Virgin of Consolation), an iconographic type developed by late-15th-century Cretan painters that sought to adapt their artistic production to the tastes of the local Venetian and pro-Latin audiences. By combining the morphological conventions of Byzantine icon painting with the humanized religiosity of Gothic and Renaissance models, icons of the Madre della Consolazione had become widely popular in the West and were massively exported to the Adriatic markets. A significant number of those icons made their way as far as Ancona and the Marche, where they are preserved until today in churches and private collections. Records of “madonne dorate alla Grecesca” are still encountered casually in local household inventories, accounting for the favorable reception of Greek icons in the region (ANA, vol. 9, notary Andrea Pilestri, 1535, fol. 193

r. For icons preserved in churches and collections of the Marche, see

Voulgaropoulou 2014, pp. 484–87, 611–30.).

In addition to the Virgin, the male figures of the composition have been also depicted in a hybrid style, imitating Italian models of the trecento and quattrocento that were frequently adopted by Greek artists in Venetian-ruled territories. Compare, for instance, the figure of Saint Jerome with an icon from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge featuring the same saint (inv. n. 1594), or the figure of Saint Francis with depictions of the saint in a triptych from the Pushkin Museum in Moscow (inv. n. Ж-266), a triptych from the Vatican Museums (inv. no. 40548), and an icon from the Museo Sartorio in Trieste (inv. no. 14682).

While in terms of style the Scottivoli altarpiece lies closer to Cretan art, in terms of iconography Angelos’ work reveals the influence of local painting workshops, such as the ones of Nicola di Maestro Antonio and Carlo Crivelli, who were active in Ancona and the Marche at about the same time. For instance, the figure of Saint Francis from the Scottivoli altarpiece bears a marked resemblance to the same saint from Nicola di Maestro Antonio’s 1487-polyptych of Jesi, now at the Musée du Petit Palais in Avignon (inv. Calvet 22872–22873) and especially to Saint Francis from Nicola’s altarpiece at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, dating from 1472, a painting which was originally on display at the Ferretti chapel, at the church of San Francesco delle Scale in Ancona (

Figure 10) (For the painter see

Mazzalupi 2008b, p. 274).

Furthermore, the depiction of Saint Cyriacus bearing the True Cross evokes the figure of Saint Andrew from Nicola’s altarpiece for Casteldemilio (Agugliano), now at the Pinacoteca Vaticana, a work contemporary to Angelos’ altarpiece as it was painted in 1504–08 (

Mazzalupi 2008b, p. 295), as well as models employed by the Crivelli workshop, as for example the figures of Saint Andrew from Carlo Crivelli’s polyptychs of San Francesco a Montefiore dell’Aso, San Domenico, and Camerino. The visual dialogue between Cyriacus’ massive, realistically rendered cross and the slender staff-cross of Saint John, is yet another element frequently encountered in Italian Renaissance works, such as Carlo Crivelli’s polyptych of San Domenico in Ascoli. Saints John and Jerome were also possibly inspired by Crivelli’s works, such as the altarpiece from the Cathedral of Camerino. Crivelli’s influence extends to the ornamental elements of Angelos’ painting, notably the highly ornamented floral patterns of the robes of the Virgin and Saint Bonaventure (

Figure 11).

A practice well established among Cretan icon painters, i.e., the reproduction of popular iconographic prototypes lay at the core of Angelos Bitzamanos’ family workshop.

2 Angelos, his younger relative Donatos, and their followers regularly exchanged

anthivola—i.e., pricked cartoons—to reproduce standard compositions of Cretan iconography. This is suggested by the repetition of certain iconographic themes in the workshop’s tradition, as was for example the type of

Our Lady Glykophilousa, painted by Angelos after Cretan models for the church of San Sepolcro in Barletta, and then copied by Donatos in an icon now at the Dominican monastery in Dubrovnik (

Voulgaropoulou 2014, pp. 582, 831–32). The same can be argued about Donatos’ icon of Saint Demetrius now at the Hermitage Museum, which is based on Angelos’ image of Saint George from the Vatican (

Voulgaropoulou 2014, pp. 923–25). At the same time, the painters drew extensively from Western models to which they had direct access, mainly from paintings they could study in Italian churches, as well as from Western-European and Italian prints that ended up in their possession. For instance, Angelos’ icon of the

Christ on the Column for the church of the Santissima Annunziata in San Mauro Forte replicates an iconographic type that had become largely popular in the region of Apulia and was encountered in particular at the church of Sant’Agostino and the Cathedral of Barletta (

Voulgaropoulou 2014, pp. 465–66, 602, 631, fig. 194.) On the other hand, Angelos’

Visitation of the Virgin, now at the Walters Art Gallery, reproduces a print by Thielman Kerver, while his

Nativity from Saint Petersburg copies an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi (

Vassilaki 1990, pp. 86–89;

Voulgaropoulou 2014, figures 374–75). It is reasonable to assume, therefore, that it was Angelos himself who consciously selected most of the above prototypes in order to best cope with the requirements of his commission. On the other hand, it is likely that at least some of these models were suggested or even imposed to the Cretan painter by his commissioners, a practice that was far from uncommon in this period. It is for instance known that in 1477 the painter Nicola d’Ancona and his father Maestro Antonio were commissioned to paint an altarpiece for the church of San Francesco ad Alto and were specifically requested to copy after a figure of Saint Bernardine from the Dominican church (

Mastrosanti 2007, p. 54;

Mazzalupi 2008b, p. 251;

2008c, p. 356, doc. 437).

To further explore this hypothesis, let us turn our attention to the figure of Saint Bonaventure, the only saint from the Scottivoli altarpiece that was not included in Francesco’s will, as already discussed. A Franciscan saint and patron of the order of the Friars minor, Saint Bonaventure was canonized by pope Sixtus IV just a few years before Francesco Scottivoli’s will, in 1482, after a 10-year long campaign. With his popularity rapidly growing, the newly canonized saint started to appear all the more frequently in art commissions of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, especially in works of the Crivelli workshop, such as in Carlo’s altarpiece from San Francesco in Fermo, now at Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Vittore’s polyptychs from Sant’Elpidio a Mare, San Severino Marche, San Francesco in Amandola, Potenza Picena, and in two panels with Saint Bonaventure now at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris.

In the Scottivoli altarpiece, Saint Bonaventure is placed in a prominent position, occupying the whole mid-lower part of the composition. Unlike the other saints who are depicted standing, he is portrayed kneeling in prayer before the Virgin with his back turned to the viewer to reveal his elaborately embroidered cope (piviale), which rivals the garments of the Virgin in magnificence. The saint’s cope is made of silk brocade with floral arabesque motifs, in the center of which are embroidered seraphs, possibly an allusion to Bonaventure’s adherence to the “Seraphic” Franciscan order and his usual designation as Seraphic Doctor (Doctor Seraphicus). The hood of his cope (scudo or cappuccio) is decorated with the figure of the enthroned Christ, depicted as a counterpart to the enthroned Virgin and dressed in opposing colors, while the Man of Sorrows (Άκρα Ταπείνωσις) is visible in a separate band above the hood.

The depiction of saints dressed in highly ornamented liturgical vestments was a common pictorial convention in Renaissance art, particularly diffused among Florentine masters, such as Fra Angelico, Filippo Lippi, Cosimo Rosselli, and Domenico Ghirlandaio. The latter, known for designing actual liturgical garments, was responsible for painting an image of Saint Bonaventure, which bears a striking resemblance to that of Angelos Bitzamanos. In his monumental

Coronation of the Virgin, painted for the Franciscans of San Girolamo in Narni in 1486, Ghirlandaio portrayed Saint Bonaventure in a similar pose, exposing his yellow-golden cope to the viewer, with his cardinal’s hat placed on the ground in front of him just as in the Scottivoli altarpiece (

Figure 12).

It should be stressed that Ghirlandaio’s composition had gained widespread popularity during his time and was repeatedly copied by painters throughout Italy. Giovanni di Pietro, known as “Lo Spagna” painted two versions of the Coronation of the Virgin: one for the Observant Franciscans of Santa Maria di Montesanto in Todi, commissioned on the same year as the altarpiece of Ancona, in 1507, but finished in 1511, and another one—a mirror image of Ghirlandaio’s original—for the Franciscan church of Trevi in 1522. Many years later, in 1541 Jacopo Siculo would revert to the same model for the Coronation he painted for the convent of the Observant Franciscans of the Annunziata Nuova in Norcia. Elements from Ghrilandaio’s composition, including the model for Saint Bonaventure, were also adopted by Cosimo Rosselli in his Coronation of the Virgin for the Church of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi in Florence in 1505.

Another thing to note is that Ghirlandaio’s composition and the above-listed copies were all intended for Franciscan institutions, indicating the consolidation and diffusion of a certain trend among the order in the early 16th century, as well as the active involvement of mendicant orders in the formation of iconographic programs and the circulation of iconographic models. The friars of San Francesco delle Scale were most likely aware of such a widely diffused trend and were in all probability the ones to propose the inclusion of Saint Bonaventure in the Scottivoli altarpiece, providing the Greek painter with the desired iconographic prototype. Still, it appears that Angelos took the liberty to adjust the proposed model to his own composition, possibly combining it with a popular engraving of the

Mass of Saint Gregory by Israhel van Meckenem, from which he seems to have borrowed the saint’s spread-hands gesture (

Figure 13).

8. Angelos Bitzamanos and Cross-Cultural Interaction in Early Modern Ancona

At the intersection of Eastern and Western artistic traditions, the Scottivoli altarpiece provides a unique reflection on Cretan cultural extroversion, while its study offers valuable insights on the early migrations of Greek artists in the West and the cross-cultural interchange that took place between the Eastern Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas during the Late Medieval and Early modern period. From the 15th century on and due to the increasing Ottoman expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans, Greek and primarily Cretan painters were traveling to the Adriatic all the more frequently, either to settle permanently or to seek temporary commissions. The majority of these itinerant painters would set out for Venice, especially after the establishment of a Greek confraternity and an Orthodox church, however, there is ample evidence documenting the activity of Greek-speaking artists and artisans in other centers of the Italian and Dalmatian coasts (

Voulgaropoulou 2020, pp. 23–73). Ancona and the region of the Marche have yet to attract extensive scholarly attention, however archival and field research suggests that the Marchigian ports constituted an important pole of attraction for artists of Greek origin, at least before the emergence of Venice as hub of the Greek Orthodox diaspora.

The earliest mention of a Greek artist in Ancona dates from 1446, when a certain master Nikolaos from Candia (“magistri Nicolai pictoris de Candia”) was hired by Urbano di ser Filippo da Cingoli for six months to “paint and design and do other things relevant to his art” (“ad pingendum et designandum et alia faciendum pertinentia et spectantia ad dictam artem”) (ANA, vol. 3, notary Chiarozzo Sparpalli, 1444–47, fol. 198

v; See also

Mastrosanti 2007, p. 37;

Mazzalupi 2008c, p. 345, doc. 225). Master Nikolaos was probably the same “Magister Nicolaus pictor de Graecia”, who was commissioned to paint an icon “in the modern style” (“moderno more”) for the main altar of the church of Santa Maria di Varano in 1475 (ANR, 1360–1939, notary Giacomo di mastro Petruccio, vol. 99, 1475, fol. 151

r; See also

Coltrinari 2005, pp. 75–77). The presence of Greeks in Ancona became more frequent after the granting of a series of trading privileges to Greek and Levantine merchants in the 1510s and the consequent establishment of a thriving Greek merchant community. It is estimated that, by the mid-16th century, more than 100 Greek merchant houses were established in Ancona, with the Greek population of the city rising up to 200 families (

Saracini 1675, pp. 361–62;

Natalucci 1960, p. 136;

Stoianovich 1960, p. 237; anonymous). These developments led to the concession of the church of Santa Maria in Porta Cipriana to the Greek rite in 1524 (

Porfyriou 2002, p. 155;

Greene 2013, pp. 27, 39). This church, subsequently dedicated to Saint Anne (Sant’Anna dei Greci), was decorated with icons by the Greek painter Ioannes Permeniates from Rhodes, as well as with panels “alla greca” by the Venetian master Lorenzo Lotto (

Voulgaropoulou 2010b, pp. 195–11;

2014, pp. 235–40, 611). Another Greek painter who was working in Ancona about the same time, possibly in relation to the Greek community, was the Cretan Ionas (“Jonac cretensis pictor”), documented in 1530 (ANA, notary Calisto Trionfi, vol. 369, 1525–43, fol. 17

r. A brief mention of the artist’s name is also included in

Mastrosanti 2011, p. 287). Mastrosanti also reports the presence of two more Greek painters, a certain “Cristoforo Siranicho”, and a “Maestro Ludovico pittore dal Levante” (

Mastrosanti 2011, pp. 287–88). This information, however, is incorrect and is based on the erroneous reading of the respective sources: in fact, the former name reads “Cristofanus Senichopolus grechus” (the surname’s suffix was read as “pictor”), while the latter reads “magister Ludovicus de Lonbardis pictor”, possibly to be identified with Lodovico Lombardi, a 16th-century artist highly active in the Marche with his brothers Aurelio and Girolamo (ANA, vol. 258, notary Bartolomeo di Corrado, 1516–24, fol. 199

rv; vol. 291, notary Gentile Senili, 1538–39, fol. 154

r). Aside from painters, in the archival sources there are also several records of Greek craftsmen working in the city, as were the goldsmiths Manolio (“Manollio Georgii greco aurifice”), active from roughly 1488 to 1495, and Ioannes from Rhodes (“magistri Iohannis aurificis de Rodo”), documented in 1501 (ANA, vol. 70, notary Melchiore Bernabei, 1488–89, fols. 95

v–96

r; vol. 88, notary Giacomo Alberici, 1495–96, fol. 229

rv; vol. 181, notary Calisto Trionfi, 1495–1504, fol. 275

v; See also

Mazzalupi 2008c, pp. 362, 366, 369, docs. 564, 632, 681).

The case of Angelos Bitzamanos stands out among these artists, not only because of the abundance of documented sources and signed works that allow us to reconstruct a fair deal of his life and activity, but also because his work encompasses the openness of Cretan culture under Venetian rule, and the vibrant cross-cultural exchanges that shaped the Adriatic into a dynamic “contact zone”. In the multicultural milieu of Venetian Candia icon painters were regularly exposed to the Italian language and culture, and constantly inventing hybrid pictorial forms to render their work more appealing to the aesthetic tastes of the local Catholic audiences. Much like his fellow Cretan painters, Angelos was well versed in both the Byzantine and Western pictorial traditions, which he harmoniously blended in his works, depending on the demands of his specific commissions. Yet, contrary to most icon painters, who were principally engaged with a Greek-speaking, Orthodox clientele, Angelos addressed his production almost exclusively to Catholic audiences. In fact, until now there appears to be no evidence to support any association of the painter with Greek patrons or Orthodox communities, whereas the subject matter, iconography and inscription language of his surviving works indicate that they were commissioned by or intended for a Latin-oriented clientele. Whether this signifies that the painter was also an adherent of the Catholic faith is much harder to determine. Although the painter’s family name, Viçimano, suggests a Latin origin, as does the fact that Angelos’ relative, Donatos, also bore a name more common in the Catholic Church, there still is not sufficient evidence to support such a hypothesis, especially given the ethno-confessional fluidity of late-15th and 16th-century Venetian Crete. In fact, the name Viçimano, although initially of Italian origin, was often encountered among Cretans of the Orthodox rite, including priests (See Nikolaos Panagiotakes’ relevant discussion on the religious affiliation of Domenikos Theotokopoulos.

Panagiotakes 2016, p. 66.) In any case, even if Angelos came from a Catholic family or if he converted to Catholicism after settling in the Italian peninsula, he never renounced his origins as “Grecus Candiotus”, an identifier which he consistently inscribed upon his works.

The documents presented as evidence in this article further confirm Angelos’ association with Catholic circles as well as his ability to handle himself within his host society. Despite being a foreigner, Angelos managed to land a prestigious commission from one of the most prominent Anconitan families, something which in all likelihood earned him a respectable reputation and financial stability. What is more, contrary to other foreign artists who were not conversant in Italian—such as the above-mentioned painter Nikolaos from Candia was in need of an interpreter when he signed with the priests of Santa Maria di Varano, even after residing in Ancona for at least three decades—Angelos was fully capable of representing himself in his legal transactions and even acted as witness and creditor for his patrons and colleagues. What is of particular note is that, although the Cretan painter was sufficiently integrated into the local society, at the same time he was well acquainted and involved with other foreign artists residing in the city.

In particular, from Troilo Leoni’s notarial deeds we learn that during his stay in Ancona, Angelos Bitzamanos maintained financial, legal and professional relations with two artists from the Dalmatian coast: the carpenter Andreas Georgii, and the painter Johannes (Juan) Boschetus (

Appendix C,

Appendix D and

Appendix E). According to the sources, the former hailed from Dubrovnik (“Magister Andreas Georgii de Ragusio carpentario habitator Ancone”) and was first documented in Ancona in 1482. In 1487 he wrote his testament in Ancona, before embarking for a trip to Valona (Vlöre). Further records of Andreas Georgii in the sources appear in years 1484 and 1502, and it is possible that he may also be identified with a certain “magistro Andrea Georgii architectore de Ancona”, mentioned in 1494 (ANA, vol. 115, notary Girolamo Pagliarini, 1480–84, fol. 305

v; vol. 115, notary Girolamo Pagliarini, 1485–89, fol. 237

rv; See also

Mazzalupi 2008c, pp. 358, 359, 361, 365, 370, docs. 483, 507, 555, 612, 691;

Mastrosanti 2011, p. 285). On the other hand, the painter Johannes Boschetus, Spanish of origin, was a naturalized citizen of Zadar (Zara), active in the Dalmatian cities of Šibenik (Sebenico) and Split (Spalato) as well as the islands Hvar (Lesina), Rab (Arbe), and Krk (Veglia). The earliest mention of Johannes Boschetus or “Giovanni di Matteo” dates from 1494, when the painter was working in Šibenik. In Ancona Boschetus was documented between 1507 and 1511, later, however, he returned to Dalmatia, where he worked until about 1526 (ANA, vol. 204, notary Bartolomeo Alfei, 1507–22, fol. 2

rv; vol. 100, notary Giacomo Alberici, 1511, fol. 97

r; See also

Mazzalupi 2008c, pp. 371–72, docs. 711, 725;

Mastrosanti 2011, p. 285. For the painter’s activity in Dalmatia see

Kolendić 1920, pp. 116–90;

Prijatelj [1960] 1963, pp. 50–52;

Prijatelj 1990, pp. 81–84;

Fisković 1987, pp. 321–32;

Domijan 2001, p. 208;

Sobota Matejčić 2008, pp. 107–14;

Bradanović 2016, pp. 103–22;

Bracanović 2011, pp. 50–51;

Schleyer 1914, p. 121). Angelos and Boschetus appear to have been in close contact, since in May 1508 the Greek painter appointed the Spaniard as his procurator, while earlier in the same year the two artists had received a joint commission to execute certain painting works.

Although it is not possible to assess the precise nature of the collaboration between the two artists, it is tempting to speculate whether their contact actively affected the development of their respective pictorial languages. A close comparison of their known works indeed leaves the possibility of a mutual influence open, despite the pronounced stylistic and technical differences. On the one hand, Boschetus’ paintings bear a marked similarity to Angelos’ works, sometimes even adopting the morphological traits of Eastern icons, chiefly the portrayal of figures half-length against a golden ground, as seen in his

Pietà from the Cathedral of Saint Stephen in Hvar. It is noteworthy that, in his report of his 1637-apostolic visit, bishop Zorzi refers to Boschetus’ painting in the Cathedral of Hvar as an “icona cum imagine Pietatis” (

Demori Staničić 1998, p. 259;

Voulgaropoulou 2014, p. 443). Likewise, Angelos’ compositional choices may also be attributed to the Spaniard’s influence. For instance, the scene of the Pentecost from his altarpiece from Komolac is designed in a way that is clearly distinct from traditional Cretan iconography, but instead closely resembles Boschetus’ corresponding composition for the church of the Holy Spirit in Hvar. Direct parallels can also be drawn between the two painters’ rendering of the theme of the enthroned Madonna and Child before a draped backdrop, notably between Boschetus’ paintings from Baška and Rab, and Bitzamanos’ relevant icons from Split, Bari, Saint Petersburg, as well as the Scottivoli altarpiece.

From the above it becomes evident that during his stay in Ancona Angelos Bitzamanos became engaged with a socially and culturally diverse network of patronage and cooperation, which arguably shaped his artistic development and determined his future course as an itinerant Adriatic artist. It is hardly a coincidence that the next documented mention of the Cretan painter would come from the East Adriatic coast, and particularly Ragusa, where he travelled in 1518 to paint the altarpiece of Komolac. The circumstances under which Angelos received that commission are still unknown, but it is reasonable to assume that the painter was introduced to his Ragusan patrons while he was still in Ancona, possibly through his above-mentioned colleagues.

During the Late Medieval and Early Modern period, the maritime republics of Ragusa and Ancona became the central nodes of a vibrant trading network that was established between the Marche and the Dalmatian coast, facilitating the mobility of people across and beyond the two Adriatic shores. This mobility is reflected in the establishment of numerous Slavic and Illyrian confraternities and colleges throughout the region of the Marche, the most prominent being the Slavic confraternity of Our Lady of Loreto, founded in 1469. Ragusan ships were regularly sailing to Marchigian ports, while numerous Ragusan merchants were frequenting the city of Ancona, often channeling their newly acquired wealth into art patronage (

Stoianovich 1960, pp. 236–37;

Popović 1970, pp. 443–62;

Natalucci 1978, pp. 93–101;

Voje 1978, pp. 200–3, p. 216;

Pantić 1993, pp. 35, 37, 40;

Abulafia 1997, p. 52). Such was the case of Alvise Gozzi (Gučetić), who in 1520 hired Titian to paint his famous altarpiece for the church of San Francesco ad Alto. Interestingly, it was a member of the same family that supervised Bitzamanos’ work in Dubrovnik, Nicolò Martini de Gozze, subsequently rector of the Republic of Ragusa (DAD, Diversa cancellariae, 108 (1518–19), 109

v; Voulgaropoulou 2014, pp. 540–41). Alongside these rising merchant elites, numerous artists and craftsmen were frequently commuting between Dalmatia and the Marche, taking advantage of the short travel distance and the ample job opportunities created by the rapid economic growth. Archival sources abound with names of “trans-Adriatic” artists, the most prominent among them being the Venetian brothers Carlo and Vittore Crivelli or the “Schiavoni” Juraj Ćulinović (Giorgio Schiavone), Ivan Duknović (Giovanni Dalmata), and Juraj Dalmatinac (Giorgio Orsini da Sebenico), who designed the portal of the church of San Francesco delle Scale in 1454 (Several cases of artists active between Dalmatia and the Marche are discussed in

Fisković 2007, pp. 48–59).

Following the steps of these itinerant artists, Angelos Bitzamanos eventually left Ancona some time before 1518 to seek his fortune on the opposite Adriatic shore. Shortly thereafter the painter crossed the Adriatic once again, although there is no indication that he ever returned to Ancona or the Marche. Instead, it seems more likely that he sailed further south to the Apulian port of Barletta, where he worked for a brief period of time, before settling permanently in the Terra d’Otranto. Despite being well along in years, the Cretan painter established a flourishing icon-painting workshop in Otranto with the assistance of Donatos and their local followers, Fabrizio and Giovanni Maria Scupula (

Voulgaropoulou 2010a;

2014, pp. 86–95). The Bitzamanos family workshop was specialized in the production of small-scale devotional images that would eventually become Angelos’ trademark, thus shaping the future reception of his work by art historiography. The discovery of the Scottivoli altarpiece, Angelos Bitzamanos’ only surviving large-scale work, steers us to a new understanding of the painter’s artistic idiosyncrasies, and calls for reassessing common historiographical perceptions regarding early modern Cretan art.