Abstract

Trisha Brown (1936–2017) forged her artistic identity as part of Judson Dance Theater, which embraced everyday pedestrian movement as dance. Between 1966 and 1969, Brown’s work took a surprisingly theatrical turn. Five unstudied dances from this period reflect concerns with autobiography, psychology, and catharsis, influences of her exposure to trends in Gestalt therapy and dance therapy during a sojourn in California (1963–1965). Brown let these works fall from her repertory because she did not consider them to qualify as ‘art’. Close readings of these works shed light on a period in Brown’s career before she rejected subjectivity as the basis for her creative process prior to her consolidation of her identity as an abstract choreographer in the 1970s and 1980s, while raising intriguing questions as to Brown’s late-career devotion to exploring emotion, drama and empathy in the operas and song cycle that she directed between 1998 and 2003.

1. Introduction

Between 1966 and 1969, choreographer Trisha Brown (1936–2017) created a small body of dances whose basis in subjective experience lent them a theatrical flair quite different from other works in Brown’s oeuvre. With the exception of one work, Brown consigned these dances to her juvenilia, as she had with three of the four works previously presented at Judson Church (all likewise performed once or twice and never seen again). Four out of the five dances were brief solos, shown at obscure locations for small audiences and received almost no critical attention.1 Focus on these works contributes to disentangling Brown’s work of the 1960s from the overarching construct “Judson Dance Theater.”

Looking back on a brief period of Brown’s beginnings as an artist when personal narrative and emotion impregnated her dances also sheds light on Brown’s astonishing late-career devotion to creating operas: in the interim (1970–1987), she closely adhered to an abstract aesthetic. However, following her 1987 contribution to Lina Wertmuller’s direction of Bizet’s Carmen (1875) at the Teatro di San Carlo, Naples, Brown tentatively explored the introduction of character and narrative into her abstract works—a process that culminated in her creation of an abstract-representational movement syntax developed while directing significant operas and an important song cycle Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607) in 1998; Salvatore Sciarrino’s original libretto and music Luci Mie Traditrici (2001) and Franz Schubert’s Winterreise (1827) in 2002.

Brown’s unstudied dances of the mid–late sixties—Homemade (1966), Skunk Cabbage, Salt Grass and Waders (1967), Medicine Dance (1967), Dance with a Duck’s Head (1968) and Yellowbelly (1969)—share dramatic effects related to their ritualistic function within Brown’s artistic development. Notably Brown cast all but one (Homemade) to oblivion as she pivoted to create works defined by impersonal, objective and conceptual approaches to choreographing from 1970 onward, fulfilling her criteria for serious art.2 As was true for her peers in SoHo, where she lived and worked, this equated to abstraction and dances that had “no emotional base or content.” (Goldberg 1985, p. 11)

Having fallen from Brown’s repertory, these dances resurfaced in the compendium of brief entries published by Hendel Teicher at the end of the catalogue accompanying her 2002 exhibition, Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue—information sourced from Brown’s unpublished handwritten and typewritten “Chronology of Dances”. During the catalogue’s making, Brown added little to the record beyond what she had told Marianne Goldberg as part of the latter’s research for her 1990 dissertation, Reconstructing Trisha Brown: Dances and Performance Pieces: 1960–1975—an invaluable record of remembrances by Brown that date to a period closer to the time when she created and performed these five choreographies.

All of these works reflect a vector of experimentation emanating from Brown’s experiences from late 1963 to early 1965 when she decamped to Oakland, California, teaching dance at her alma mater, Mills College, while her then-husband Joseph Schlichter studied dance therapy. Created by Brown on her return to New York, these experimental dances suggest influences of her exposure to developments in Gestalt therapy, information that came to her not only through her husband’s dance therapy studies, but also through her participation in workshops held by Ann Halprin in which the boundaries separating the theatrical and the therapeutic were porous. All of the dances that Brown presented after returning to New York operate within this terrain, When Brown explained her exclusion of this works from her curated oeuvre she said that she considered “[these dances] too personal to be called art” (Goldberg 1990, p. 169) Rather, she identified their performance as fulfilling a private cathartic function in her artistic development: that of exorcizing of vestiges of emotion and drama from her work and creative process.

2. California Sojourn (1964–1965)

As a measure of the transformation that occurred during Brown’s time in California it is worth considering the piece that she performed at the California College of Art in April 1964: Target (1964). In a letter sent to Yvonne Rainer on 27 April 1964, Brown described this duet with her husband as derived from a numerical score juxtaposed with a limited repertoire of spoken phrases, which served as cues. In other words, it demonstrated zero emotionality and no any relationship to ritual or catharsis—although Brown’s statement to Rainer that “I love it because it scares me so much to do it” does presage her later interest stage fright as a choreographic motif.3 (Brown 1964) Brown excitedly told Rainer that Halprin had invited she and her husband to perform at the workshop on May 13 and 18, where she planned to show one of her rulegame works—likely Rulegame 5—with “repeats if necessary.”4 (Brown 1964).

However, her next five documented dances rejected Target’s use of scores that include numbers and language combined with everyday gestures, carryovers from Robert Dunn’s teachings of John Cage’s methods of composition to dancers/choreographers in workshops that spawned Judson Dance Theater. Never before discussed together, these five dances are defined by their uncharacteristically autobiographical impetus and dramatic tension, setting them apart from any other works in Brown’s career—even as in retrospect, they can be seen as tangentially related to Brown’s late-career operas, which required the accessing of emotion, storytelling and empathy.

Brown had previously participated in a summer 1960 workshop with Anna Halprin, held on her outdoor dance deck, set into the landscape of Mount Tamalpais in Kentfield California: it focused on imparting principles of improvisation. In contrast, the Halprin whom Brown encountered in 1964 was startlingly differed from the person with whom she had previously studied. In 1964 Halprin met Fritz Perls (1893–1970)5 (Ross 2007, p. 174). A pioneer of Gestalt therapy, Perls affiliated himself to the Big Sur-based Esalen Institute, founded in the fall of 1962 by “two transcendental meditation students, Michael Murphy and Richard Price,” who wished to create “a forum to bring together a wide variety of approaches to enhancement of the human potential.” (Hayton 1992, p. 211). During a period when Esalen’s mission was to expand into the community, running programs in cooperation with churches, schools, hospitals and government, Halprin brought Perls to lead group experiences on her dance deck.6

Halprin’s established workshop model was primed to experiment with Gestalt psychology’s notion of “psychotherapy without authority,” (Wheeler 2005, n.p.) while her deep engagement with improvisation dovetailed with Gestalt therapy practices focusing on the therapist’s “analy[sis] of only process, not content. (Wheeler 2005, n.p.). Therapeutic outcomes were tied to the theatricalization of psychological dramas and traumas with the workshop providing a “space where individuals could experiment with how to perform their immediate present and be in the here-and-now, but in a theatrical rather than a therapeutic context.” (Ross 2007, p. 177). As Halprin said, “I wasn’t thinking of that as therapy, I was thinking of it as theater.” (Ross 2007, p. 176).

Brown did not participate extensively in Halprin’s workshops with Perls—mostly joining on weekends when she was not teaching, “participating more out of the relationship with my husband.” (Brown 1993, p. 12). She visited the Esalen Institute, but not extensively. In later recollections Brown emphasized her profound misgivings about Halprin’s new direction, recalling a disturbing incident that remained vivid in her mind forty-three years later:

We went over to Halprin’s. She very much liked my husband. She liked guys. And she was delving into psychology. The body brings with it emotions. (author’s emphasis). You have to be a skilled practitioner. For instance, they were these people from Esalen… three guys; Fritz Perls was at the top of the pyramid and his wife Laura, a couple stages down […] Then there was Anna and one or two other men who had followed psychology. My husband went into this direction. I took a class. It was one of the most painful experiences of my life. She was a patient of one of these two men, I can’t remember their names. They set up a little trauma reenactment or maybe it was more abstract than that [author’s emphasis] and she was at the center of it. She was in her fifties at that time. I was not experienced in psychology or tragedy, I had no experience in that and I was not Jewish. I was not equipped to deal with this woman and I don’t think anyone else was. And I wasn’t interested in that work.7.(Brown 2008, April 15)

Brown remarked to the latter’s biographer, Janice Ross, on how completely Halprin had changed: “She’d become involved in catharsis, expression. There were these early dance therapy people and she was completely involved with that. It was not my idea of a dance class.” (Ross 2007, p. 180).

3. Enter Theatricality

Despite Brown’s expressed distaste for the direction of Halprin’s workshops, the dances that she made on the heels of her California stay, reveal the theatricalization of psychological states, of memories and of personal dramas. For example, in her final appearance at Judson Church on 29 and 30 March 1966 Brown presented the three-part work, A string: Homemade, Motor, Outside (1966). The first section (Homemade) showed intimately scaled movements drawn from memory and her life as a young mother. She executed the work’s emotional-laden pedestrian, non-virtuosic movement with movie projector attached to her back via a baby carrier; thus. Brown screened a film by Robert Whitman showing the very dance that she was performing. (Rosenberg 2017, pp. 36–64).

With its title redolent of a home movie and domesticity, Homemade’s sources and content differ from the Yvonne Rainer’s near-contemporaneous, affectless Trio A (1966), whose aesthetic Rainer summed up in her influential 1965 “NO” manifesto which rejected “spectacle,” “magic and make believe,” calling attention to contemporary choreographers’ facing “the challenge…of how to move in the spaces between theatrical bloat with its burden of dramatic psychological meaning and the imagery and atmospheric effects of the non-dramatic, non-verbal theater…”(Rainer 1965, p. 78) While Brown’s dance shares a formal structure with Trio A—the placement of one move after the other without transitions—Homemade juxtaposes a pantomime of recognizable highly personal found gestures, whereas Trio A presents unique, deliberately awkward, unaccented functional movements. As Brown explained, “I gave myself the instruction to enact and distill a series of meaningful memories, preferably those that impact on identity.” (Teicher 2002b, p. 301).

In Homemade, Brown performs the motion of holding up a baby; imitates the act of blowing up a balloon with cartoon-like physical exaggeration—expanded cheeks expanded, legs deeply bent to express the effort of this activity, and arms encircling the imaginary object. A deadpan miniature dramatic moment occurs when she casually jumps into a pair of visibly worn hospital sandals placed on the stage. Grounded in Judson Dance Theater’s treatment of ‘found movement’ as dance, Homemade presents subjectively-infused theatrical actions whose foundational concept relates to one of Fritz Perls’s core beliefs: “that muscles can talk.” (Berne 1970, p. 1520).

Her method for creating Homemade activates Fritz Perls’ concept of “re-living,” (Fiordo 1981, p. 109) and emphasis on “the grounding of experience in embodiment […]” (Wheeler 2005, n.p.) While it is unlikely that Brown was aware of the work of theater director Konstantin Stanislavsky—Ann Halprin certainly was; one can see how Brown’s treatment of her body as a score, replete with memories that she transformed into movements, resonates with Stanislavsky’s vision “[…] that control of the body can bring forth emotion.” (Kemp 2012, p. 159). Stanislavsky emphasized the use of “emotion memory exercises” (Kemp 2012, p. 159) to explore physical memory’s relationship to affective memory. Brown, played out the process reverse: emotional memories led her to physical memories—eccentric movements that neither told a story nor expressed psychological states.

This choreographic model had special utility for Brown because until 1971 she faced the challenge of making dances in the absence of a movement vocabulary of her own (Sommer 1972, p. 135). Determined not to repeat herself, she followed Homemade with a solely improvised dance performance in Skunk Cabbage, Salt Grass and Waders (1967), first presented at New York’s Spring Gallery (222 Bowery) on 14 May 1967 and then two years later as part of exhibition “Danza Volo Musica Dinamite,” on 22 June 1969 at Rome’s L’Attico Gallery. Its autobiographical voice-recorded accompaniment featured Brown reciting memories of duck hunting with her father as a child in the Pacific Northwest, where she was raised. With a title that alludes to the hunting experience, this work featured Brown’s wild, out of control improvised dancing and two props: a chair and a bucket filled with water.

4. Improvisation, Ritual and Self-Authoring

The ritualistic quality of the duck hunting theme (see quotation below from the piece’s soundtrack) informed the ritualistic quality of Brown’s performance of Skunk Cabbage, Salt Grass and Waders, which she called a “breakthrough,” explaining “I was using powerful movement trying to get to a real sledgehammer level, the equivalent of throwing a punch. It upset me to do it—I worked with interior fireworks in the improvisation. Salt Grass was like an exorcism of my background in an effort to get into synch with the urban sensibility […]” (Goldberg 1990, p. 151). In other words—and based on the evidence of works that Brown did maintain in her choreographic repertory—Brown retroactively ascribed to the roughness of Skunk Cabbage’s movement—as juxtaposed with a private memory—an important role: that of releasing her from dependence on a model for dance-making that she came to reject as overly personal once she embraced abstraction as her model for choreographing.

In a rare report on the first New York performance of Skunk Cabbaage, critic Jill Johnston wrote that Brown “made some wild shooting sounds and sat in a tub of water, then turned around and dunked her chest and belly in the water.” (Johnston 1967). In photographs from the Spring Gallery performance Brown soaks in the tub, while a film of the 22 June 1969 L’Attico Gallery performance shows her reeling off-balance, with her drenched white shift dress clinging to her body, and marks of water left on the floor as she falls on the hard brick surfaces of the gallery site—a former garage on Via Beccaria.

Johnston extolled Brown’s “truly inventive movement and spontaneous and nonchalant performing quality,” noting that the dance incorporated “all sorts of nervous and descriptive gestures [such as] hard movements of arms that knock out the dancer’s breath… and some difficult-looking whipping turns, and falls, and hand stands that melt into a crumple on the shoulder and the back.” (Johnston 1967). If, according to Maiya Murphy, “The widespread use of improvisation in postmodern dance… demonstrates [the] endow[ment] [of] the body with a self-authoring creative capacity,” (Murphy 2015, p. 142) Skunk Cabbage intensified this effect, complementing the physical dimension of performance with a ‘self-authored’ vocalized story.

Looking back on Skunk Cabbage, Salt Grass and Waders (1967) Brown saw its significance as related to another aspect of this self-authoring: her ability to get “through personal levels of experience to clear things out for choreography in the future,” (Goldberg 1990, p. 145)—in other words, her embrace of abstract movement and choreography three years later. Retroactively Brown dismissed the emotional and theatrical dimensions of this Skunk Cabbage with characteristic humor and irony, describing the sound score—which told an intimate story in an authentic voice—in these terms: “I wrote and taped a text of this mellifluous light woman’s voice talking about killing birds.” (Goldberg 1990, p. 149). Jill Johnston noted that the performance included a “great bit of talking to the audience (without making any sound).” (Johnston 1967). Marianne Goldberg offered the fullest account of Brown’s recorded text, and confirmed that Brown mouthed some parts without making sounds:

the thing that I remembered most about these trips […] the ritual—the ritual of going hunting. It begins at dawn—being wakened oh probably an hour before dawn because you have to get dressed and you have to get dressed in special clothes […] for the second thing after getting up that’s part of the ritual breakfast…breakfast was always fried eggs very greasy fried eggs with thick bacon […] and then fill your thermos with consommé and coffee and get the sandwiches and get the gear […].(excerpt of soundtrack from Goldberg 1990, p. 151)

5. Dance as Theatrical-Therapeutic

Brown’s work took on a more outwardly theatrical-therapeutic direction with Medicine Dance (1967) presented two months later, in Upper Black Eddy, Bucks County, Pennsylvania on the program Sundance: A Season of Chamber Music and the New American Arts. Little is known about this relatively minor work: Brown provided a succinct mysterious rationale for its making that aligned its concerns with those of Salt Cabbage, Salt Grass and Waders: “In 1967 I needed a medicine dance.” (Goldberg 1990, p. 127). Her statement implies that this work was catalyzed by a search for reparative healing through movements’ performance, another instance in these years when she resorted to that combination of the theatrical and therapeutic that she imbibed in California.

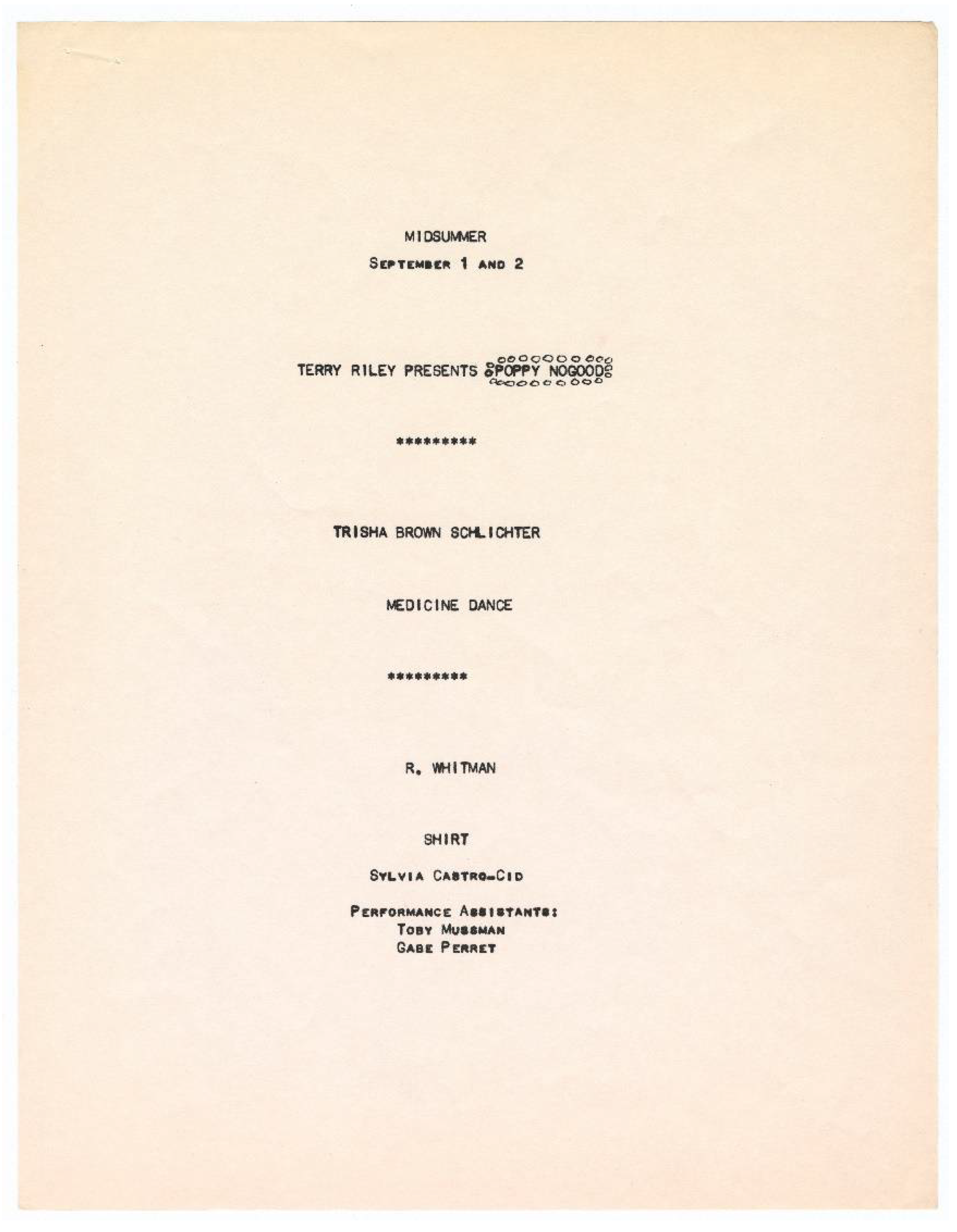

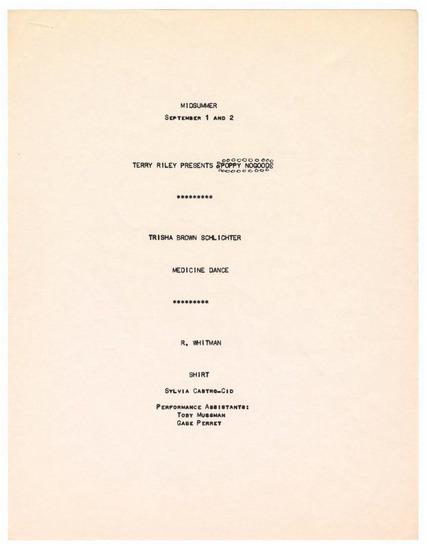

Shown last on a 1–2 September 1967 program titled Midsummer Medicine Dance followed minimalist composer Terry Riley’s Poppycock No Good and Shirt and work by Robert Whitman in which his wife, Sylvia Palacios Whitman (identified as Sylvia Castro Cia on the program performed (Figure 1)). Sylvia Whitman (who witnessed Medicine Dance and went on to join Brown’s company in 1973) described Brown as performing “almost like a cat. She made this incredible sound—like a pant. She was crawling and turning as she went in and out of the performance space.” (Goldberg 1990, p. 127). If conceived as a personal ritual, Medicine Dance heralded Brown’s creation of the most emotional and expressionistic dances of her career: Dance with a Duck’s Head (1968) and Yellowbelly (1969).

Figure 1.

Page from the program for “Midsummer,” 1967. Courtesy of Trisha Brown Archives and Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library.

In both Brown engineered a deliberately tense relationship between the dancer, (Brown), and her audience. Dance with a Duck’s Head (1968) and Yellowbelly (1969) include movement-centered performance and give language a prominent role; both span the categories of choreography and performance art, due to their activation of audience response and audience participation and their incorporation of human voices. Both notably capitalize on overtly emotional aggressivity—echoing with Gestalt therapy models built “theoretically and methodologically, around the reclamation of desire and aggression themselves, the very ‘energies’ that Freud had posed as the dangerous dark side of human nature.” (Wheeler 2005, n.p.).

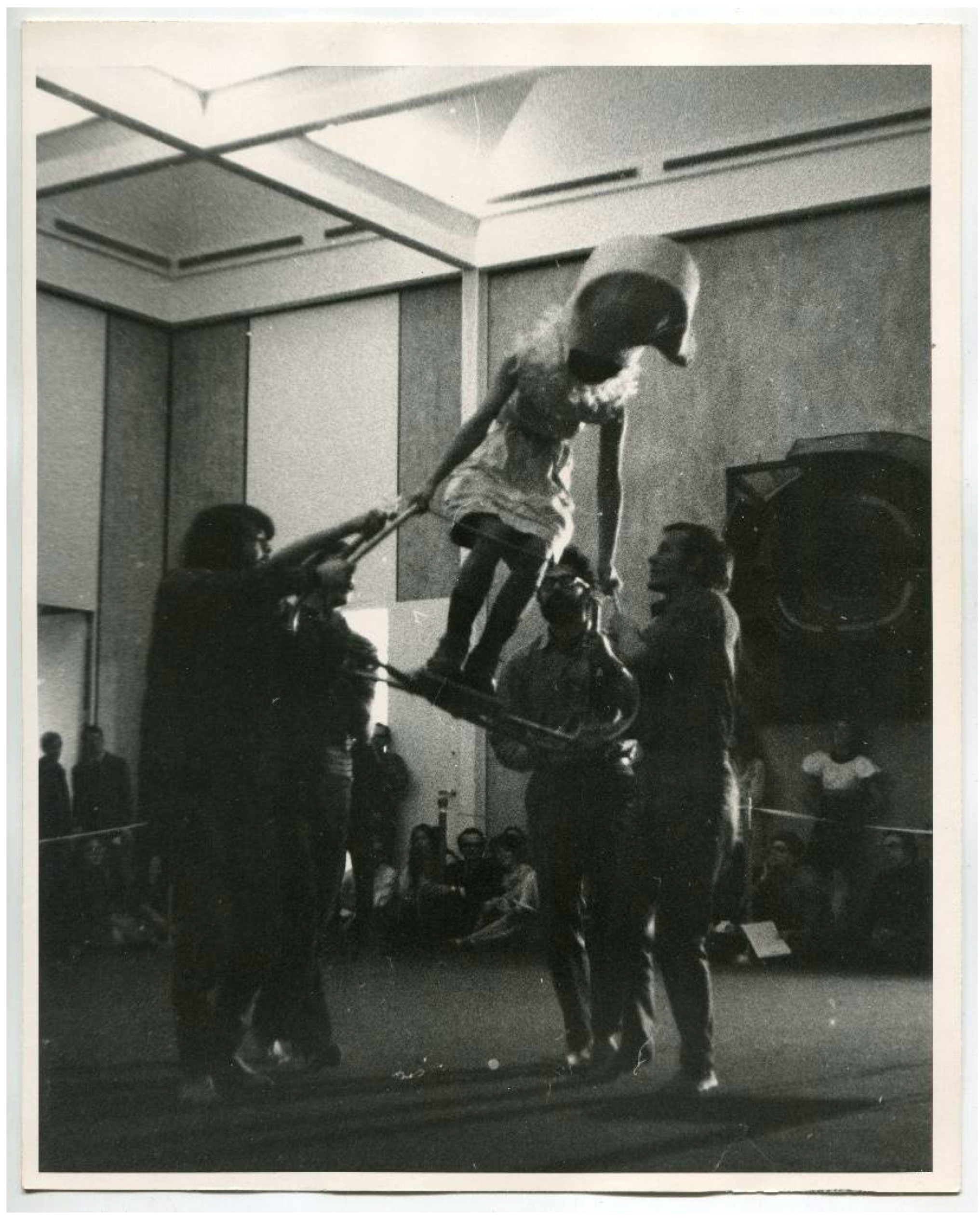

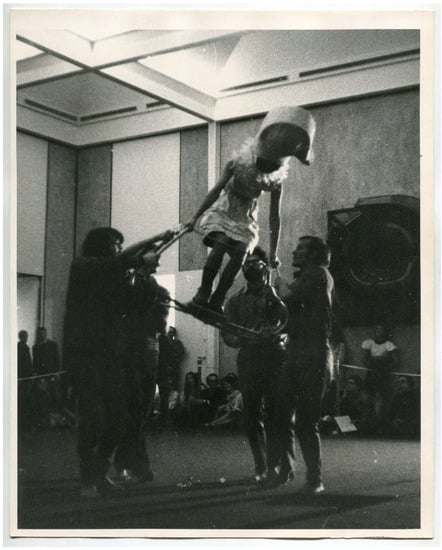

Presented at Brown’s first museum performance, Dance with a Duck’s Head was the fourth program of “Student Evenings” held on December 8, between 6:30 and 11:00 p.m., at New York’s Museum of Modern Art—events that the press release explained were open only to “college and university students.” (MoMA 1968). For this work, Brown costumed herself in a handmade papier maché mask, brassiere, and skirt, a collar of chicken feathers, and “a helmut in the shape of a duck’s head, also adorned with chicken feathers,” (Teicher 2002a, p. 259) materials and forms reminiscent of Claes Oldenburg’s happenings because papier maché is associated with craft and children’s art-making, and because—like Oldenburg—Brown made the costumes in a deliberately slap-dash, unrefined style, as if it was created by an untrained, unskilled amateur artist. She annotated her costume sketches, describing a dance of “tremendous energy commotion versus silent commotion.” (Goldberg 1990, p. 165).

In performance this commotion took the form of fight that Brown’s orchestrated between Joseph Schlichter and artist David Bradshaw: “The two wrestled violently kicking a few spectators, sending others running. [Brown] thought maybe the fight would expand into the audience, but it remained Joe and David until exhaustion. One minute, forty-seven seconds approximate time. It could have gone on until the guards broke it up.” (Goldberg 1990, p. 165). Once things calmed down Brown, the ‘duck lady’ put her feet a pair of logging boots bolted to a metal frame—the chassis of her son’s obsolete rocking horse—and was hoisted by four ‘carriers’—Steve Carpenter, Peter Poole, Elie Roman and sociologist Melvin Reichler who, like Trisha, was one of SoHo’s first settlers in the 1960s.

Held aloft she “careen[ed] around the space in a cumbersome sort of flight,” (Teicher 2002b, p. 302) with Lee Bontecou’s fierce Untitled (1961) installed on wall just behind her. (Figure 2) Brown said the dance’s theater followed from her awareness, through her husband, of therapeutic dance encounter groups in California (Brown 2008, April 15). Marianne Goldberg reported “At a time when body therapists were beginning to push for the public performance of emotion in encounter groups, Brown made male violence public […]” (Goldberg 1990, p. 165).

Figure 2.

Trisha Brown, Steve Carpenter, Peter Pole, Elie Roman, and Melvin Reichler in Dance with the Duck’s Head (1968). December 6, 1968. Photograph by Jeanie Black. Courtesy of Trisha Brown Archives and Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library.

6. “Psychodance”

The chaotic staged argument was a theatrical element that Brown imagined might seem real to her audience. She related its pugnaciousness to a tumultuous time in her marriage.8 Combining interior psychological states with exterior expression, Dance with a Duck’s Head affiliates to psychodrama—an element in Fritz Perls’ practice, although not an area of his training or specialization.9 Also relevant to this interpretation is the 1969/1970 publication of an essay by Brown’s then-husband, Joseph Schlichter, entitled “Sequence Psychodance (1964)” (Schlichter 1969–1970, n.p.), which appeared in the final 1969/1970 issue of Impulse—a journal of dance edited by Mills College Dance Department’s founding director and faculty emeritus, Marian van Tuyl at the inspiration of Ann Halprin.

This issue focused on “aspects of dance and movement therapy” (Van Tuyl 1969–1970 n.p.). Schlichter identified dance as “a complete mode of therapy,” a concept that Brown transformed into fictional artistic theatrical spectacle in Dance with a Duck’s Head. A subsequent section explained Schlichter’s “Methods,” while the next page ended with a smoothly written paragraph identified as “from a forthcoming book by Joseph R. Schlichter with Paul David Pursglove, Gestalt Therapist and Richard Nonas,” (Schlichter 1969–1970, n.p.) formerly an anthropologist and soon to serve as one of the two rooftop belayers, in Brown’s Man Walking Down the Side of a Building, (1970).

In Yellowbelly (1969), presented on the same 22 June 1969 program where she showed Skunk Cabbage, Salt Grass and Waders—“Danza Volo Musica Dinamite” at Rome’s Galleria L’Attico—Brown established a fraught relationship between the audience and the performer to produce a highly combustible theatricality. The premise was simple: Brown incited audience participation, insisting its members scream ‘yellowbelly’—a word from her childhood in Aberdeen, Washington which meant coward; the crowd’s heckling and shouting cued her improvisational dancing.10 Brown claimed that she devised Yellowbelly to heal herself from stage fright. In her words it was “a nightmare I made just for myself—and I was quite wise, because nothing could ever be as bad again.” (Goldberg 1990, p. 162). She recalled that “I did not move until they [the audience] did indeed start yelling at me. So I killed the dragon in a sense and I didn’t have to worry about it anymore. I fought back through slinging a bunch of undecipherable gestures at them.” (Mazzaglia and Polveroni 2010, n.p.).

7. Conclusions

Apart from the reprisals of Homemade, the existing photographic and film recording’s of the Rome performances of Skunk Cabbage, Salt Grass and Waders and Yellowbelly, one photograph of Dance with a Duck’s Head and brief mentions of Yellowbelly in publications of the 1970s and 1980s, Brown largely ignored this group of dances as if to confirm Sylvia Whitman’s statement (about Medicine Dance): “Don’t you think if Trisha didn’t remember, maybe she doesn’t want to?”(Goldberg 1990, p. 126) This 1989 interview indicates Whitman’s belief that Brown cut these works from her history because their emotional qualities so dramatically departed from her self-identification as an abstract choreographer, once she founded her dance company in 1970. Never reprising any of these works—except Homemade—Brown left sparse documentation of them, restricting insight into this experimental period in her career when she explored autobiography and psychological experiences of release, infusing her work with a distinctly unorthodox theatricality.

At the same time the record of Brown’s statements about these dances shows that they served an important role in her development: enabling the excavation and exhaustion of a working process dependent on highly personal subject matter and the use of dance to showcase or transform Brown’s psychological states. These dances served as a waystation en route to creating choreographies according to more rational and impersonal methods, including the use of mathematical sequences, a rigorous exploration of the body’s basic movement possibilities and the rejection of emotion, narrative and music. Indeed in 1970 with her “Dances in and Around 80 Wooster Street,” program—which featured the iconic Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970)—Brown literally moved outside of herself, and outside of her domicile, taking to SoHo’s streets, building facades, rooftops and art galleries to discover new methods for scoring dances in relationship to the architectural sites, streets, neighborhood loft spaces and art galleries, where she presented her work over the next decade. Resisting theatricality and subjectivity from 1971 to 1975 Brown pursued what she called “pure movement,” relegating psychological drama—her own and that expressed in her dances from 1966–1969—to the deep past as a means to move forward.

Confronted with this analysis of her work it is imaginable that Brown would adopt a position similar to that taken in response to queries about her “Equipment Dances” (1971–1974) when she stated, “I don’t even know who that woman was, it has been such a long time.” (Brown 2008, April 15) This statement reveals Brown’s dedication to ceaseless self-reinvention each time that she embarked on a new cycle of dances; it also performed the function of keeping critics focused on her next new dance, or series of dances, ensuring that she remained a ‘contemporary’ artist, even as she aged. The statement announced a profound rejection of nostalgia for her past, reinforcing her belief in the historicity of each choreography that she created. With Brown’s ongoing experimentation as an artist—in particular, her shift towards exploring character, psychology and narrative as she ebbed closer to directing operas in the 1990s and 2000s—she recognized her works’ contradictory sources and effects. Her creation of a vocabulary of an abstract-representational movement became the hallmark of the operas and song cycle, which she directed between 1998 and 2003.

This late career development inspired reengagement with questions of psychology, emotion and theatricality—but now in tandem with Brown’s well-established use of abstract movement. In working from operas’ librettos and music, Brown conjured personal empathy to instill characters with storytelling capacities through the use of a subtly connotative movement vocabulary of Brown’s invention. These works’ success powerfully rebuked critics who considered Brown—an abstract choreographer, known for commissioning new soundscores by living avant-garde composers in the 1980s and 1990s—to be the last person one might imagine entering this venerable interdisciplinary genre. New knowledge of Brown’s 1966–1969 dances allows recognition that Brown’s abstract movement and choreography in the 1970s and 1980s was but one period in her career, bookended by periods of work inspired by explorations of drama and narrative. Even if there is no direct line from the works discussed in this article to Brown’s operas, their inclusion in Brown’s history as a choreographer meaningfully complicates and expands understanding of her changing artistic concerns, methods and influences.11

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest with regards to this essay.

References

- Berne, Eric. 1970. Review of Gestalt Therapy Verbatim by Frederick S. Perls, M.D. Ph.D., compiled by John O. Stevens (California: Real People Press, 1969). The American Journal of Psychiatry 126: 1519–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Trisha. 1964. Letter to Yvonne Rainer, 125 East 25th Street, 27 April 1964. Yvonne Rainer papers, Series II. Correspondence, Box 8, Folder 6 Container List Series II. Correspondence. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Trisha. 1993. Interview with Janice Ross. In Janice Ross Papers, The Elyse Eng Dance Collection. Typescript. San Francisco: Museum of Performance + Design, 13p. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Trisha. 2008. Interview with the author. New York, April 15. [Google Scholar]

- Fiordo, Richard. 1981. Gestalt Workshops: Suggested In-Service Training for Teachers. The Journal of Educational Thought (JET)/Revue de la Pensée Éducative 15: 102–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Marianne. 1985. Taking Simple Instructions to the Limit: Interviews with Trisha Brown. New York: Trisha Brown Archive, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Marianne. 1990. Reconstructing Trisha Brown: Dances and Performance Pieces: 1960–1975. Ph.D. Dissertation, New York University, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Hayton, Gyeorgos Ceres. 1992. The Mother of All Webs: Who Gotcha! A Phoenix Journal: Tangled Webs, 3. Sanger: America West Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Jill. 1967. Review. The Village Voice. New York: Trisha Brown Archive, Review Clippings File, June 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Rick. 2012. How Does the Actor Embody Emotion in Fictional Circumstances. In Embodied Action: What Neuroscience Tells Us About Performance. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 156–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaglia, Rosella, and Adriana Polveroni. 2010. Trisha Brown L’Invenzione dello Spazio: Conversation with Rosella Mazzaglia and Adriana Polveroni, October 19, 2009. In Trisha Brown: L’Invenzione dello Spazio. Edited by Rosella Mazzaglia. Reggio Emilia: Collezione Marmotti. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Maiya. 2015. Chapter 7: Fleshing it Out: Physical Theater, Postmodern dance and Some(agency). In The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Theater. Edited by Nadine George Graves. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 125–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rainer, Yvonne. 1965. Some Retrospective Notes on Dance for 10 People and 12 Mattresses Called ‘Parts of Some Sextets,’ Performed at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut and Judson Memorial Church, New York, in March 1965. The Tulane Drama Review 10: 168–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choreography as Visual Art, 1962–2017. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

- Ross, Janice. 2007. Experience as Dance. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichter, Joseph R. 1969–1970. SEQUENCE, Psychodance (1964). In Impulse. Extensions of Dance issue. San Francisco, n.p. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, Sally R. 1972. Equipment Dances: Trisha Brown. TDR/The Drama 16, The “Puppet” Issue September, 135–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, Hendel. 2002a. Bird/Woman/Flower/Daredevil: Trisha Brown. In Trisha Brown: Art and Dance in Dialogue, 1961–2001. Edited by Hendel Teicher. Exeter: Addison Gallery of American Art, Philips Academy, pp. 269–84. [Google Scholar]

- Teicher, Hendel. 2002b. Chronology of Dances 1961–1979. In Trisha Brown: Art and Dance in Dialogue, 1961–2001. Edited by Hendel Teicher. Exeter: Addison Gallery of American Art, Philips Academy, pp. 299–318. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tuyl, Marian. 1969–1970. Preface. In Impulse. San Francisco, n.p. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Gorden. 2005. Spirit and Shadow. Available online: http://www.gestaltpress.com/spirit-and-shadow-esalen-and-the-gestalt-model/#_edn11 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

| 1 | One of the five works, Dance with A Duck’s Head (1968), involved seven performers: Steve Carpenter, Peter Poole, Elie Roman, Melvin Reichler, David Bradshaw, as well as Brown and her then-husband Joseph Schlichter. |

| 2 | Having first performed Homemade on a 29 and 30 March 1966 program at Judson Church, she reprised it on 22 June 1989 on commission from the eighth edition of the Montpellier Dance Festival in the no longer extant Jacques Coeur courtyard. (Confirmed an email with photographer of this event, Vincent Pereira 8 February 2021). In the absence of walls, Trisha Brown Dance Company member, Wil Swanson, moved behind her holding up white screen to catch the moving image projections. The piece was again reprised for the Trisha Brown Dance Company’s thirty-fifth anniversary, with Brown making it a dance of the sixty-year-old Brown juxtaposed with the film of her thirty-year-old self. The dance was remade for performance by Mikhail Baryshikov with a new film, shot by Babette Mangolte as part of the Baryshnikov’s Judson Dance Theater program PAST/Forward, at the Brooklyn Acadmey of Music, 2000. It was last reprised by Vicky Shick at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2013, with a film of Shick shot by Babette Mangolte. |

| 3 | Trisha Brown, letter to Yvonne Rainer, 125 East 25th Street”, sent April 27, 1964. Getty Research Institute, V. Yvonne Rainer papers, 1871–2006 (bulk 1959–2001); Series II. Correspondence, Box 8, Folder 6 Container List Series II. Correspondence, 1953–2005. Also remarks by Judith Shea from a November 20, 2001 interview with Hendel Teicher, published in Teicher, “Chronology of Dances, 1961–1978,” 300, Target involved six specific movements (what she called ‘phrases’) performed in random order and combined with “4 events that are performed according to mutual verbal cues or when we run into each other.” A page in Trisha Brown’s Personal Archive, provides more specific information, including how the six phrases, i.e., the gestures associated with the numbers 1 to 6, were organized into a sequence of sixteen movements differently ordered for each performer, and that the four interrupting phrases: “Seeming to come by wing; Let’s hug; Going West and Joe-Look Out.” |

| 4 | There is no documentation to back up the claim that Rulegame 5 (1964)—which Brown presented at Judson Church on the same 29 and 30 March 1966 program at Judson Church where she showed Homemade—was first performed at Humboldt State College, Humboldt, California on 13 April 1964 (as it states on the website of the Trisha Brown Dance Company). It is likely that this dance was performed at California College of the Arts, along with Target—since the program date was about one week before Brown’s 27 April 1964 letter to Rainer, where she mentioned these works. |

| 5 | In 1933 Perls and his wife Laura had fled Nazi Berlin for the Netherlands. The next year they moved to South Africa remaining there from 1942–1946. From 1946–1960 they lived in New York from 1946 to 1960 before settling in Los Angeles. From 1963–1969 Perls taught at the Esalen Institute, in Big Sur, connecting with Halprin in 1964 |

| 6 | According to (Ross 2007, p. 294). Halprin reciprocated during the late 1960s and early 1970s when she “was recruited by George Leonard, vice president of Esalen, to help him orchestrate the opening group improvisations at several weekend workshops conducted by Esalen around the United States.” |

| 7 | This workshop occurred in one of Ann’s weekend events that was led by Eugene Sagan, a psychotherapist trained at the University of Chicago, who had been working with Perls since 1960. See (Ross 2007, p. 180): “Brown and others were distressed with Sagan’s aggressive encounter style as he pushed a distraught Holocaust survivor to painful limits in playing out her experience. ‘He kept going, pressing, going, pressing. I just recall feeling to young and inadequate to participate in this. It was big stuff.’” |

| 8 | In the summer of 1970, Brown joined a consciousness-raising group organized by SoHo neighbor, painter Louise Fishman; as Fishman reported, “And what happened is Trisha, by the end of the summer, decided she was leaving her husband and did—boom, just like that.” See Judith Olch Richards, “Interview with Louise Fishman,” 21 December 2009, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, 21 December 2009, transcript, p. 30 (this interview took place over several days; Fishman made the statement on 31 December 2009). |

| 9 | Joseph L. Moreno (1889–1974) is credited as the founder of psychodrama therapy. As Eric Berne wrote of Perls’ connection to this technique, “he shares with other ‘active’ psychotherapists the ‘Moreno problem: the fact that nearly all known active techniques were first tried out by Dr. J.L. Morena,’ so that it is difficult to come up with an original idea in this regard.” (See Berne 1970, p. 1520). |

| 10 | In an interview with Marianne Goldberg, Brown recognized that the term “yellowbelly” brought with it ugly racist connotations about which she was unaware as a child. (Goldberg 1990, p. 162). |

| 11 | I have raised these questions in my essay, “Trisha Brown: Between Abstraction and Representation,” Arts, Dance and Abstraction issue, 9/2, 43 (27 March 2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020043. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).