On 13 March 2017, in Wolnica Square in Cracow, I ate ice-cream tasting of tears. The ice-cream recipe was concocted by the Gdansk-based artist Anna Królikiewicz, who called her invention Tears Flavor Frost. By doing this, she embodied emotions in the ice-cream. She translated the bitter-and-salty of tears into a flavoring in which she meaningfully contrasted these savors with the freshness of fruity notes and the mild sweetness of the milk. Rather than a regular dessert, the ice-cream was designed as a challenge to perception and the stuff of memory.

“Maps of dried tears whose topographies can be seen under the microscope: they differ in their morphologies, in the intricate patterns of salt structures; they chart territories of feelings. Tears of emotions additionally contain the stress hormone noradrenaline, bitterness-releasing sodium, and traces of a natural analgesic”,

1 Królikiewicz explained in a commentary on her piece. Her ice-cream could evoke one of the feelings listed by St. Augustine, their various combinations, or their entire ensemble. “I am drawing on my memory when I say there are four perturbations of the mind—cupidity, gladness, fear, sorrow”, St. Augustine wrote in his

Confessions (

Augustine 1992, p. 191). For the emotions to be summoned, they had to be preceded by experience: “[B]efore I recalled and reconsidered them, they were there. That is why by reminding myself I was able to bring them out from memory’s store” (pp. 191–2). Królikiewicz admitted on Facebook that she had no difficulty developing the recipe, as she had spent the whole of January crying. This, however, was followed by “multiple reasons for joy”, and hence the ice-cream was ultimately poised at the intersection of “the sweet, the bitter, and the salty”. What especially appeals to me in St. Augustine’s reflections is his metaphorical rendering of recollection as chewing. St. Augustine himself finds it slightly amusing but nonetheless suitable for conveying the mechanisms of bringing back memories.

2 In a key passage that pivots on this metaphor, the philosopher refers to sweetness and bitterness, the basic flavors of Królikiewicz’s ice-cream: “[M]emory is, as it were, the stomach of the mind, whereas gladness and sadness are like sweet and bitter food. When they are entrusted to the memory, they are as if transferred to the stomach and can there be stored; but they cannot be tasted” (

Augustine 1992, p. 191). This and Królikiewicz’s other works discussed below can be said to rouse the flat taste of memory.

1. Palatal Memory

In her International Man Booker Prize-winning

Flights, the recent Polish Nobel Prize laureate Olga Tokarczuk dwells on the essence and structure of memory, observing that “with age, memory starts to slowly open its holographic chasms, one day pulling out the next, easily, as though on a string, and from days to hours, minutes” (

Tokarczuk 2018, p. 289). In this way, “the body of time” is reborn (

Tokarczuk 2018, p. 290). When exploring the art of Anna Królikiewicz, one may readily have an impression that her works add up to a persistent process of embodying time, memories, and emotions, in which gaps and voids are meaningfully filled. At a certain point, the artist deliberately abandoned the typical communicative tools of a painter and has consistently availed herself of a cook’s utensils ever since. This decision was preceded by a walk from the studio over the carpeted hall to the kitchen, as she recalls (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 46). For almost ten years now, she has been dedicated to redefining the relationship between the idioms of fine arts and cooking, whereby she has drawn inspiration from her predecessors who had the courage to breach the enshrined principle of the disinterestedness of art.

3 For example, she appreciates Filippo Tommaso Marinetti for the idea that the human stomach is a clean, stretched canvass—the surface of a painting that expects to be filled with the ornaments of the ingested foods (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 43). However, unlike the Futurists, Królikiewicz is no revolutionary, and her object is not to sever the ties with the past. She believes that her passage from the studio to the kitchen marked not so much a rupture, as rather a transformation, because—as she evocatively puts it—nothing surpasses drawing with a piece of lemon tree coal, graphic blacks of caviar and sepia ink, adding arabesques of cream and ricotta, and finishing off with liquid port-wine crimsons and impastos of fresh figs (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 43).

Królikiewicz has a lot in common with Rirkrit Tiravanija, as their artistic attitudes dovetail in the idea that what is pivotal to art is not an object, but experience and relationships spun around it, a standpoint resulting from their belief in the organic growth of the community and the imperative of opening up to mutuality (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 46). Both Kólikiewicz and Tiravanija perceive feeding as primal and fundamental, as a universal language of care, though both are at the same time aware that eating is also a tool for differentiating and a sphere of politics. Her female patrons include Judy Chicago, Leonora Carrington, Martha Rosler, and Mona Hatoum, whose art is a testimony that the kitchen—a sacred sphere where femininity is celebrated (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 49)—may easily mutate into a site of oppression, ridden with a mantra of small gesture, nauseating in their repeatability (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 52).

Similar to Daniel Spoerri, Królikiewicz traverses flea markets, examines remnants of culture, and develops self-disintegrating, impermanent artworks that are replete with a symbolic and gustatory potential, which stems from the cooking and sharing of food. Spoerri’s signature pieces are the famous trap-pictures (

Tableaux pièges)—spatial compositions of plates, cutlery, glasses, and food leftovers which are glued to tables and preserved in exactly the same state in which they were left by the banqueters. Spoerri’s art may be interpreted as an urge to eternize the incidental, but also as an expression of the shallow roots of the “pathological nomad” (

Schwarz 2010, p. 27) and his predicament of indefinite identity.

4Simple rituals of everydayness involved in the cooking and sharing of meals are converted by Królikiewicz into rites of art. The artist “locates memory in the stomach”, and her art is a laboratory in which relations between memory and food/eating are studied. She herself admits: “For more than 20 years my art has been revolving around emptiness, absence, fragility of memory and body” (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 84). Her method of choice consists of synesthetically transposing sensations from one area of excitation onto another. The artist relies on tastes and smells to restore the memory of past moments, places, and people and to give life to the dead. She inquires into the nature of perception, modes of remembering, and possibilities to foster a community around the table. Once-alive existences resurface in Królikiewicz’s pieces in the form of sensory traces. As imaginations are stirred, and sensory experiences are engendered, an artwork emerges and takes shape, in which the artistic situation at hand coalesces with the bodily activity of the audience. If indeed, “the past is sedimented in the body itself”, as argued by Ulrika Maude, an eminent Beckett scholar (

Maude 2002, p. 119), the past can be effectively accessed by way of corporeal stimulation. Consequently, the esthetic experience becomes a species of anamnesis, a memory-activating feat.

5Our taste buds preserve inscriptions of prior culinary experiences, which are bound up with the memory of their contexts and circumstances. A bite of a madeleine washed down with a sip of tea triggered waves of memory in Marcel Proust’s novel, a locus classicus in discussions of and studies on memory. Predictably, the image features in Beckett’s comprehensive essay entitled

Proust, in which Beckett ponders two kinds of memory: “voluntary memory”, which is linked to deliberate operations of the intellect and the will, and “involuntary memory”, which is entwined with bodily sensations: “Involuntary memory is explosive, ‘an immediate, total and delicious deflagration’” (

Beckett 1931, p. 20). Despite its contingent nature, “[i]t chooses its own time and place for the performance of its miracle” (

Beckett 1931, pp. 20–21). It is only involuntary memory that can serve as the source of a profound experience of the past (

Beckett 1931, p. 1), which “[t]he long-forgotten taste of a madeleine steeped in an infusion of tea, conjures in all the relief and colour of its essential significance from the shallow well of a cup’s inscrutable banality”, Beckett comments (

Beckett 1931, p. 21).

The voluntary-involuntary memory distinction is also relevant in Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of perception. As emphasized by Maude, who builds on Merleau-Ponty’s seminal insights, involuntary memory “alone can bring back the past in full” (

Maude 2009, p. 16), since “[v]oluntary memory in its bluntness, fails miserably to evoke the past, for we can only truly remember ‘what has been registered by our extreme inattention’” (ibid., p. 15).

Nonetheless, voluntary memory has its responsibilities and uses as well, and they lie in intentionally searching for tastes from the past. When Jennifer Jordan examines relations between nostalgia and tasting in her

Edible Memory: The Lure of Heirloom Tomatoes and Other Forgotten Foods, she insists that their interconnectedness is founded on physiological processes. The memory of former meals is associated with the senses, among which smell has a particular role to play because it is on smell that the experience of taste hinges. Smell is very directly—indeed, literally—connected to the area of the brain which controls memory processes. It is, therefore, no coincidence that certain smells are capable of immediately evoking some very vivid memories (

Jordan 2015, pp. 32–33). Unsurprisingly, Jordan concludes that emotional attachment to certain flavors seems to be especially strong and salient among immigrants as people who miss their lost home. When these tastes are unavailable, their lack is acutely felt, and when they appear, they offer respite. Cuisine from migrant’s forsaken country helps them feel its closeness again.

These mechanisms have also been investigated by David E. Sutton. In his well-known paper “Taste, Emotion, and Memory”, Sutton describes the situation of immigrants in terms of fragmented experience. The lost homeland seems to produce a gnawing phantom pain, which can only be alleviated by food. There are at least two good reasons for this. One of them is that taste and smell are associated with episodic memory, whose characteristic details may persist over decades. Importantly, taste and, even more emphatically so, smell evokes the context of the past experience. The way that smell operates is comparable to how the symbol functions: “[B]y virtue of the accepted definitions […] the symbol is the part of the whole, or the object that gives rise to thoughts of something other than itself, or the motivated sign, etc.”. (

Sperber 1975, p. 118). The other reason why the mechanism of emotional identification is effective is to be found in Sutton’s firm assertion that the act of eating is an important component of social memory and that, crucially, “[f]ood does not merely symbolize social bonds and divisions; it participates in their creation and recreation” (

Sutton 2005, p. 315). The bodily nature of memories makes the smell of basil instantaneously transport a fresh Greek immigrant from London back to Greece.

As Maude explains, “[i]t is in the nature of memories, in the flow between past and present, to be incomplete, phantomlike, fragile” (

Maude 2009, p. 21). Is it at all possible to put together a satisfying image of the past when we endeavor to “recall” people whom we have never met and to recognize places which we have never seen, or which once looked entirely differently?

The tear-flavored ice-cream evoked at the beginning of this paper is not the only one in Królikiewicz’s repertory. Actually, the first piece produced in Królikiewicz’s painterly kitchen was ice-cream called

Flesh Flavor Frost, which accordingly tasted of the sweated human skin. The combination of smells was concocted on the basis of tofu and almond milk, the ingredients which the artist seasoned with “smoked salt, birch juice and black truffles, because of their biological, rain-like odor” (

Królikiewicz 2015). The visitors to Królikiewicz’s Sopot-based studio could find a memory of erotic intimacy, or at least envisage it. A special role in this process was ascribed to cumin, which Królikiewicz describes in the following way: “Cumin is an ingredient which most closely approximates the richness and warmth of the aroma of the clean, breathing skin. Cumin imbues the ice-cream with the smell of the sunshine in the countries where it is grown, with the sweetness of sweat, the plowed-through soil, and the smell of a beach-tanned arm” (

Królikiewicz 2015).

Since Flesh Flavor Frost, many of Królikiewicz’s projects have revolved around the bodiliness and fragility of memory. Further, in my argument, I focus in more detail on two site-specific installations—How much sugar? and The Drugstore—which, like Flesh Flavor Frost aspired to become unique time machines and to build a relationship with the past by means of a synesthetic transfer. To grasp some of the meanings of these artworks, a brief flashback into the history of Poland is in order, revisiting the past of Sopot and Gdansk, cities which form the backdrop of the two pieces.

Similar to many other countries in East-Central Europe, Poland has experienced a series of disasters, some of which interrupted its historical continuity. When Poland was partitioned and had no sovereign statehood (1795–1918), memory was the chief strategy for sustaining the sense of national unity. Having regained its independence in 1918, Poland lost it again in 1939, invaded and occupied by Germany and Soviet Russia. As a result of the Yalta treaty in 1945, Poland’s borders were shifted westwards, and the loss of some of the eastern territories was compensated for by the addition of a strip of formerly German lands. Complex developments took place then in Gdansk, a city on the Baltic Sea whose population was largely German, and which had enjoyed the Free City status since the Treaty of Versailles. Following the Yalta decision, Gdansk was incorporated into Poland, and as the Germans were leaving the city in 1945, new settlers—Poles—were arriving, mainly from the eastern borderlands.

2. How Much Sugar?

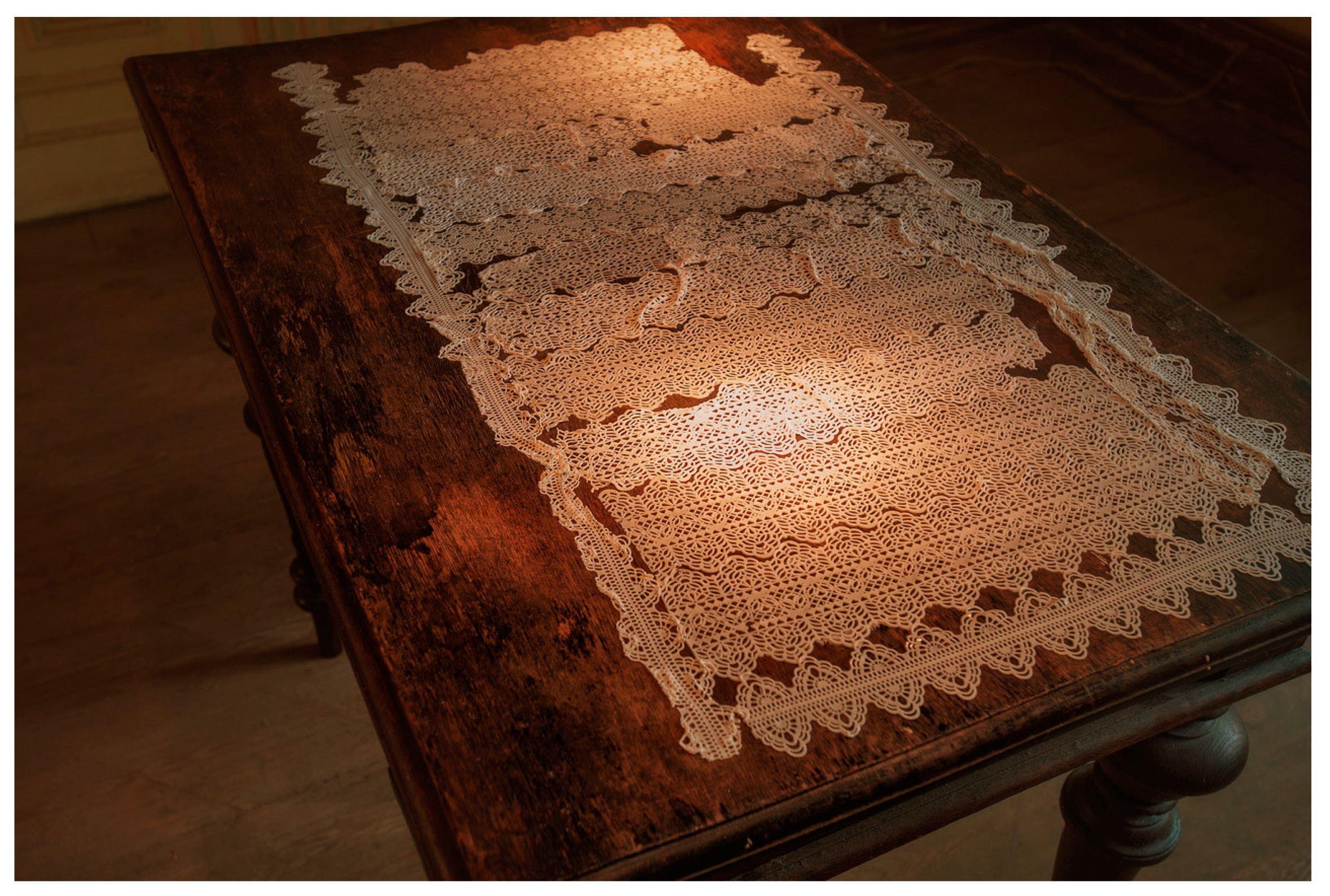

On 18 May 2013, in the evening, Anna Królikiewicz draped a lace tablecloth over an old, worn-out table in the kitchen of Berger’s villa in Sopot. The villa was built in the late 19th-century for the wealthy Danziger Johann Immanuel Berger, who commissioned it to be designed in then-fashionable neo-Renaissance style. After its first proprietor’s death in 1909, the villa was owned by Paul Heinrich Hermann Ressler and, subsequently, by Karl Kette. Shortly before WW2, it passed into the hands of Karl Hildebrandt. Between 1945 and 1954, the building housed the College of Fine Arts, and then it served as lodgings for the artists who taught at the College.

The interior layout of the villa has remained unchanged, save a few minor exceptions, since its construction. The former plan of the rooms has been retained, but their functions were reassigned whenever new tenants moved in. While the villa was one family’s residence before the war, it later had to accommodate several families. What were formerly drawing rooms were converted into living rooms, kitchens, and bathrooms for the new dwellers. The original kitchen of the elegant summer house was located in the basement, removed from the handsome rooms. This was also where utility rooms and servants’ quarters were located. The conservator’s survey of the building details the following elements: “In order to streamline the maids’ work, a small kitchen elevator was put in, connecting all the floors. The elegant rooms—a music room and drawing rooms—were situated on the ground floor. These rooms had direct access to a conservatory, adjacent to the north side of the building, wherein all likelihood exotic plants and citruses were grown, as the fad of the day dictated. There was a small fountain in the conservatory, with a shell-shaped basin and a lionhead waterspout”.

6 Królikiewicz staged her artistic intervention in a room on the ground floor.

7 As the photo records of Królikiewicz’s installation make clear, the kitchen-gear was a foreign element in the space of this room. A gas cooker and a sink were fitted into a corner of the spacious room with a large window overlooking the green garden (

Figure 1). Pipes and electric cables lined the walls and pierced the molding at the ceiling. They had probably been put in in the mid-1950s, when the building had become a dwelling place again, partitioned into apartments for artists.

The audience could have an impression that the host of the apartment into which the artist had let them had only left a while before. As if they had arrived at the appointed place just a bit too late. Afternoon tea tableware had already vanished from the table. Somebody had placed glasses with some leftovers of oolong tea in them aside for washing-up. Perhaps it was the same person who asked the visitors, “How much sugar?” As stated by the artist herself, her work is a “[m]inimalistic and intimate intervention into a dead nest that has no dweller” (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 100). What remains is “[a] couple of glasses with some tea left in them standing in the sink which is no longer being used for washing. Air is filled with dust” (ibid.).

In

Watermark, Joseph Brodsky broods on his sentiment for water and his habit of spending New Year’s Eve in its vicinity: “I am looking for either a cloud or the crest of a wave hitting the shore at midnight. That, to me, is time coming out of water, and I stare at the lace-like pattern it puts on the shore, not with a gypsy-like knowing, but with tenderness and with gratitude” (

Brodsky 1992, p. 44). The lace-like pattern wrought by water is an image of time to Brodsky. In Królikiewicz’s installation, memory also appears as lace. The metaphor for memory cannot possibly be a dense, tight-knit fabric. The openwork texture fell apart into pieces, highlighting the damage caused by the passage of time.

Króliewicz’s lace tablecloth turned out to be an edible object made of four kilograms of sugar, boiled water, and egg white (code 0) (

Figure 2). At the opening event, it was eaten, whereby history found its closure in the symbolic act of the “absorption” of the past.

3. The Drugstore

The first floor of the Berger villa “was probably occupied by bedrooms and a bathroom with a no-longer preserved bathtub of brass”.

8 Berger owned a factory of soap and other washing agents. Although Królikiewicz’s other work I selected for discussion is not directly related to Berger’s life story, his trade is a suitable segue to the

Drugstore, another of installations in which the artist seeks to reclaim the fleeting sensual atmosphere of an old soap store. This is a site-specific installation put up in a former colonial goods store, which traded in exotic merchandise, such as coffee, tea, rice, spices, chocolate, and cigars. In an attempt to trigger memory-work, the artist again mobilized the sense of taste by mingling the orders of a colonial goods store and a drugstore. She specifically relied on two intense flavors: the bitter flavor of lavender and the “muddy” flavor of Indian patchouli, which she used to prepare impressive desserts. The participants approached the counter, which was peppered with cake stands full of pastries, in the semblance of Viennese cafés. Some of the sophisticated babkas, sponge cakes, and pannacottas sported untypical colors, ranging from pale pink and light blue to dark purple and deep claret (

Figure 3). When their crispy brown crust was cut open, other cakes revealed their earthy green insides, like iridescent inner shells. Only the intensely pink candy floss did not differ much from its variety sold in the streets in summer. Spoons holding one-bite portions were fastened to the wall, serving their delicacies straight to their mouths. Putting up the installation on the ground floor of a run-down townhouse in Biskupia St., instead of at a gallery, expanded the circle of visitors, and the opening was attended not only by habitués of art exhibitions but also by the residents of the neighborhood, whose curiosity was spurred by the unusual occasion. Trying to find some footing in this bizarre event, the visitors fell back on their familiar sensory contexts. The patchouli flavor was accommodated as the taste of gingerbread. In an interview with Jakub Knera, Królikiewicz recalls: “Local homemakers who had come to “see” the exhibition, asked me for the recipe for “that gingerbread”. To them, the cake resembled a rich-tasting, spice-filled bake” (

Knera 2013). Many of the participants in the performance failed to assimilate the intensity of lavender, especially that its soapy taste defied any easy transposition onto the realm of cuisine. Some visitors would leave the gallery to stealthily spit out mouthfuls of cake. As they were unable to normalize the experience, a sense of alienation was engendered.

Królikiewicz’s method is unique in that she abandons the exclusively cognitive mode of remembering, promoted by ocularcentrism, which distinctively pervades our culture. The artist aspires to stimulate sometimes anemic memory to compose from scratch an image of a place that is strongly marked by the presence of its previous dwellers. She does not propose a cognitive dialog or intellectual processing of sensory data; instead, she constructs a relationship ensuing from emotional and empathetic processes. Vision and hearing, which are called distance senses, have traditionally been recognized as the source of the most valuable knowledge. Bodily senses, i.e., taste and smell, which are contact senses, have been ignored as, purportedly, utterly subjective. Philosophers have been reluctant to deal with the body, and the esthetic experience has been defined as necessarily founded on distance and impartiality. In this way, taste—the most intimate of the senses—has been ousted from the realm of art. Królikiewicz is one among a host of contemporary artists who have rebelliously dedicated themselves to artistic practice in the domain of taste. She is interested in “[i]nterpenetrations, enmeshments, mutating relations with the world, rather than in the subject-object opposition. Hers is embodied practice committed to sensing, participation, and engagement as a bodily phenomenon, instead of to thinking as a detached intellectual process” (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 67).

Today, we know that gustatory experiences are multisensorial and that the areas in which individual senses operate overlap, while the imperative of cold and distanced objectivity is untenable. This recognition is perfectly exemplified by the Italian essayist Francesco Matteo Cataluccio, who recalls:

Darkness may indeed smell. I remember, for example, that when the Arno River flooded in 1966, we had no electricity for several days. My father jokingly said that it was as if we had all entered a painting by Georges de La Tour. What I still remember from these sad days in November are darkness and the stench of the mold. These two sensations (visual and olfactory) still linger on in me. When there is no light at home, my brain instantaneously makes me sense the smell of dark mud, while light comes across as clean and healthy to me (

Cataluccio Francesco Matteo 2020).

Like Cataluccio, Królikiewicz is thoroughly aware that darkness may have a smell and that the volatile molecules of scents can be harnessed to produce images and fuel feelings. These insights underpinned her idea of the

Absolutes installation. In November 2012, Królikiewicz installed two diffusers spraying around synthetic odors at the Gdansk Municipal Gallery. Their mission was to conjure the olfactory texture of 19th-century fairs, which were regularly held in the Długie Ogrody [Long Gardens], a neighborhood adjoining the gallery. The organ of smell was to serve as a time machine to transport the audience into the past. As the artist explained: “My goal was to create a sensory illusion of standing near a large amount of fresh fish, fruit bulging with juice, shrivelling and withering flowers” (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 103).

Królikiewicz’s practice is deliberately and pervasively paradoxical, as, in her works, she seeks to preserve evanescent memory through evanescent taste and smell. This strategy makes perfect sense when read in the light of the theory of imagined gestalt, which, though admittedly classically marshaled to explain how literary texts work, easily lends itself to applying as an overall principle of interpretation. Wolfgang Iser believed that chasing some ultimately correct meaning was an illusory pursuit because the process of understanding had to be preceded by an act of the imagination through which an artwork received one of multiple possible shapes—an imagined wholeness: “The imaginary is not semantic, because it is by its very nature diffuse, whereas meaning becomes meaning through its precision. It is the diffuseness of the imaginary that enables it to be transformed into so many different gestalts, and this transformation is necessary, whenever this potential is tapped for utilization” (

Iser 1979, p. 17). The activation of taste and smell, the senses which are uncommon in art, ostensibly thwarts establishing the semantic idea of the artwork, yet if we are ready to sacrifice the value of interpretation for the relevance of deep participation, we will appreciate the polysensory stimulation which serves to fashion a holistic image of the place. Since the imagined gestalt serves to link the real here-and-now to its past, the dispersed meanings finally become unified.

4. The Card Index of Memory

Günter Grass’s

The Tin Drum pictures a vivid and, at the same time, grotesque scene of Danzig on fire, with raging flames relentlessly devouring building-by-building and square-by-square (

Grass 2009, p. 372). The burning of Danzig depicted by Günter Grass marks the end of a certain era and heralds a new beginning and a new order. Soon after the blaze, the smoldering ruins of Gdansk will be seized and controlled by communist Poland, and the political turn will see the city’s population replaced nearly in its entirety. With the Germans ousted, the city will be settled by Poles relocated from various regions of Poland’s prewar territory. The newcomers will join the Polish minority who lived in Gdansk before the war. The same developments took place in Sopot, which, as much as it is, in fact, part of Gdansk today, was part of the Free City of Gdansk (Freie Stadt Danzig) back then.

This grand history crossed paths with the personal history of the Królikiewicz family. Like all other relocates, the artist’s parents faced the daunting task of forging a community out of a motley crowd who had different experiences and cultivated different customs specific to the areas whence they had arrived. This task was all the more complicated because the challenging processes in which the new dwellers were gradually making the city their home involved forgetting those who had been there before them. However, material culture, apartments, furniture, household utensils, and the like belonged to another world and triggered memory conflicts. The newcomers would find unfamiliar objects in kitchen drawers and cupboards. They took over somebody else’s favorite armchairs and went to sleep in beds where sheets had been spread for somebody else’s rest. The peeling paint off the façades of prewar buildings still reveals old German inscriptions even today. A concerted effort was undertaken to erase the German past of these lands by propagandistically trumpeting the inherently Polish nature of what was dubbed the Recovered Territories. Consequently, new generations were raised “among ghosts”. The silence imposed by the communist regime has since proven an extremely difficult issue that is still being worked through by discussing memory conflicts endemic in this area. This predicament has loomed not only over the Northern Lands, where Królikiewicz dwells but also over the Western Lands, annexed to Poland in the same circumstances, with Lower Silesia as their largest region.

Meditating on past sentiments, St. Augustine writes that “[p]erhaps then, just as food is brought from the stomach in the process of rumination, so also by recollection these things are brought up from the memory” (

Augustine 1992, p. 192). It was not an option for the newcomers to bring emotions up from the “stomach of the mind” in the semblance of ruminants. Many of them, though, managed to benefit from the promise of a new beginning. Olga Tokarczuk, whom I have already quoted, shares the experience of living in the once-German area with Królikiewicz. The writer settled in Lower Silesia in the 1990s. A house which she bought in the Kłodzko Valley was, as she herself reflects, a wonderful gift for her as a writer because it came with an injunction to describe this beautiful land in her own language and in terms of her own culture. She did not fear that “[e]verything must be started all over anew” and planned to “sharpen her quill in order to capture the vastness of the world and fill all the empty places in space and in memory” (

Tokarczuk 2019, p. 174).

The metaphor of chewing is perfectly epitomized in “Totems and Beads”, a poem by Tomasz Różycki, who lives in the post-German city of Opole. What is chewed in the poem is a foreign identity and unfamiliar memory. This is a precondition for attaining one’s own rootedness.

Everything I have is post-German: a post-German town

and post-German forests, post-German graves,

a post-German apartment, post-German stairs

and clock, dresser, plate, a post-German Vokswagen

and shirt, and glass, and trees and a radio,

and right here on this rubbish heap I’ve built

my own life, on this refuse where I will reign,

digesting and decomposing. It fell me to grow

a fatherland from it [...].

No foothold can be found in foreign objects and experiences which seem to beset I-speaker.

10 The emotional discomfort bred by invading somebody else’s intimate space is labeled as the Snow White syndrome by Tokarczuk: “In the version of the fairy-tale in which we were embroiled in the aftermath of the war, the dwarves had gone never to come back again, leaving to us their rooms and furniture, their houses and streets, hills and paths, and we must now domesticate them” (

Tokarczuk 2019, p. 178). The history of the domestication of post-German Legnica is an axis of the philosopher Leszek Koczanowicz’s essay “The Memories of Childhood in a Spectral World”. The spectral world abounded in strange inscriptions and books in an incomprehensible language: “There were kitchen containers with words

Salz,

Pfeffer, or

Zucker on them, which were ignored” (

Koczanowicz 2020, p. 39). Not infrequently, sugar was kept in a pepper container and the other way round. Roasted sunflower seeds or Russian candies could work as a Legnica species of the madeleine for Koczanowicz, who grew up in a post-German town without Germans, but with Soviet soldiers stationed there for decades.

The world is by definition uncompleted, but on Recovered Territories, the task of building it tends to be more taxing than anywhere else. The difficulty resides in two issues. One thing is that the building must occur in a reality that was somebody else’s reality until recently. The other challenge is that newcomers to a foreign realm do not chance upon any kindly natives who offer to guide them. Paradoxical though it may sound, Koczanowicz wonders whether it is possible to remember places one has never gone to and people one has ever met: “Yet what happens to memory which is stripped of its natural point of reference—of place? What happens to memory which does not encompass the

here at hand, but reaches out, instead, into some faraway world? What happens to memory which must collide with the incorporeal memory of

this place?” (

Koczanowicz 2020, p. 38). He also answers the haunting question about the point of such efforts. I will revisit this issue at the end of this paper.

5. The Horizon of Taste

Elsewhere, I have discussed strong links between flavors on the one hand and emotions, embodied memory, and sentiments on the other.

11 This is applicable both to personal experiences and to social memory frameworks. Indeed, the two are not disjoined, and even things apparently as individual as the sensory sensitivities of particular people have their social dimension. That the sensibility horizon is shared can be explained on the basis of the mechanisms “of sharing a sensory orientation among those who seek to live together in an olfactory or flavor community” (

Ulloa et al. 2017, pp. 29–30).

The memory of past gustatory experiences is stored in the body and anchored in the situation surrounding the meal. The experience of taste is fleeting to the utmost. It basically defies being preserved in the language (

Koczanowicz 2018, pp. 202–11). It only comes alive when it is repeated because the tunnels of memory open up then. The bygone, inaccessible experiences can also be reconstructed in the space of art.

Królikiewicz metonymically activates the memory of the former lodgers of the deserted Berger villa. She helpfully offers props capable of producing “an illusion of continuity, even of an intimate bond with the already-gone dwellers of abandoned places” (

Koczanowicz 2020, p. 38). Nevertheless, the image of the past is fragmentary, and Królikiewicz navigates the space of insufficiency. As she writes in “Interlanguage”: “The key lies in the details, which lead us with their texture, function, color, sound or imagined taste through the meanders of bygone life, the past that none of us had a chance to experience” (

Królikiewicz 2019, p. 95). The tools she provides are inaccurate, ambiguous, and metaphorical. Yet, these are the only possible tools, and they suffice if we put trust in the agency of emotional and intuitive knowledge.

The participants in the event who—because of their age if for no other reason—have no memory of drinking tea infused in glasses may appreciate this component of the installation as an echo coming from the past, a generational difference, but the sweet taste of tablecloth—the primal sweetness embodying the comfort and security of the first meal, mother’s milk—bears a universal message. Robert Nozick emphasizes that feeding means giving the person being fed the sense of security, bliss, attention, and relatedness (

Nozick 2006, p. 58). It also evokes “primal contact with the nurturative mother; the security of being at home in the world, connection to other life forms, thankfulness too—the religious will add—for the fruits of creation” (

Nozick 2006). For its part, art entails venturing beyond the comfort zone since it is an experiment. This inherent experimentation is part and parcel of Królikiewicz’s practices. The artist strives to make us directly encounter the past. The esthetic experience takes the form of empathy, which—instead of being stirred through a toilsome deciphering of the protagonists’ consciousness—ensues straight from immersion in their sensory world of smells and tastes. Królikiewicz’s efforts stand every chance of success because, as Nozick argues,

[e]ating is an intimate relationship. We place pieces of external reality into ourselves; we swallow them more deeply inside, where they are incorporated into our own stuff, our own bodily being of flesh and blood. It is a remarkable fact that we turn parts of external reality into our own substance. We are least separate from the world in eating. The world enters into us; it becomes us. We are constituted by portions of the world.

In Królikiewicz’s installations, the senses operate as a vehicle of historical knowledge, but this knowledge has its obvious limits. The artist musters stimuli that are geared to spurring memory and imagination. In this way, she initiates an action whose course of which she is unable to fully control, as it unfolds in every individual experience, the shape of which is determined by the perceptual sensitivity, class position, knowledge and biological makeup of the visitors. The effect of alienation and discomfort which permeates Królikiewicz’s works is an admonition not to enter into an artistic situation naively and unreflectingly. Nobody promises here an easy time-jumping spree or an unproblematic solution to the issues of the past. All the artistic projects discussed in this paper share the sense of lack as their central feature. This lack is associated with transience, with change which produces space for the new where the old was, but a while ago. It also involves an inability to know for certain that our sensations and experiences approximate those felt by people before us. Królikiewicz invites us to engage in dialog with the other, which as Koczanowicz stresses, is inevitably arduous and painful: “Entering into somebody else’s life must evoke anxiety, and, accordingly, a host of stories were circulated with a view to alleviating this sense of fear and insecurity that harrowed people who had settled new worlds and tried to convince themselves that they were their legitimate inheritors” (

Koczanowicz 2020, pp. 37–38). Time is “a double-headed monster of damnation and salvation” (

Beckett 1931, p. 1) and for this reason we must not relinquish the toil of domesticating the past by attempting to establish contact, no matter how desperate such attempts may be, because it is “the only way to appease the anxiety of memory” (

Koczanowicz 2020, p. 53).