In a Time Loop: Politics and the Ideological Significance of Monuments to Those Who Perished on Saint Anne Mountain (1934–1955, Germany/Poland)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Saint Anne Mountain—Franciscan Sanctuary and National Socialist Thingstätte

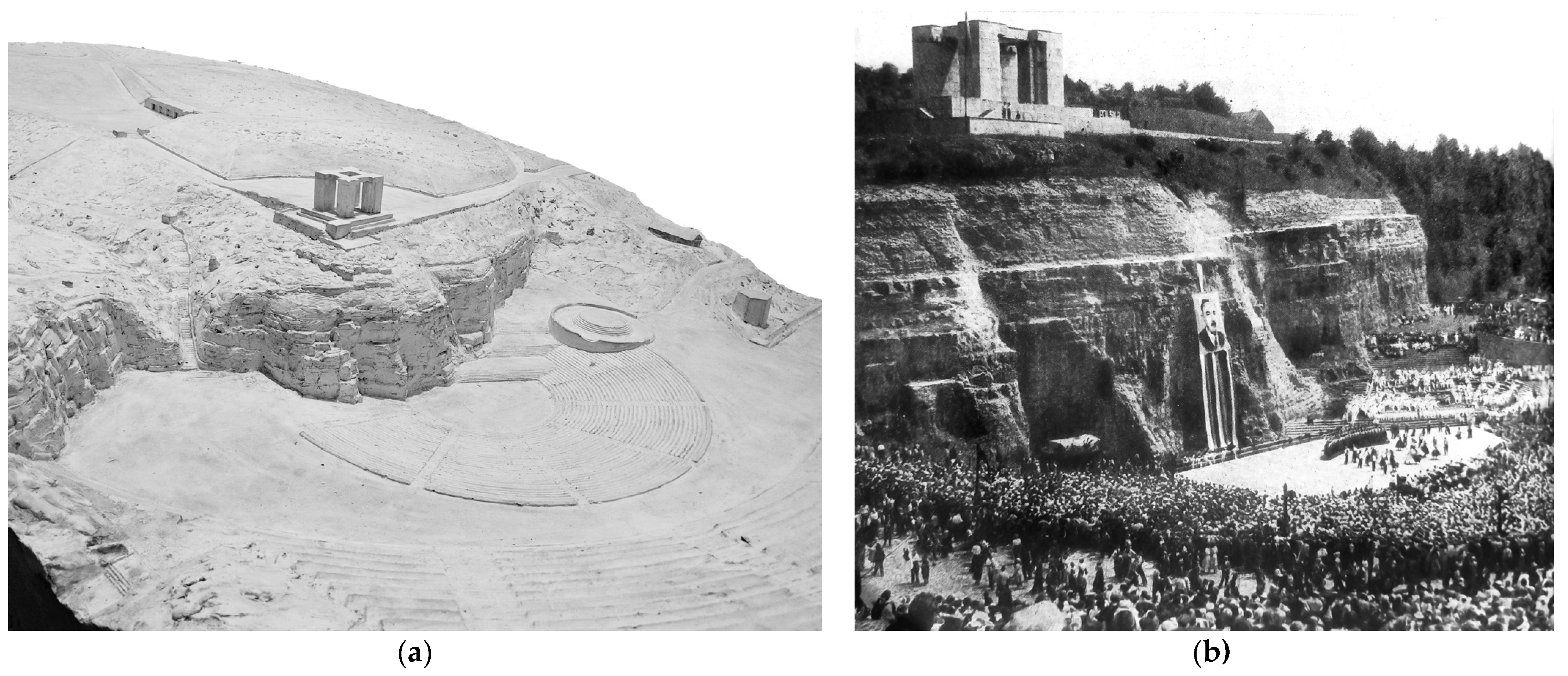

3. Evolution or Revolution? German Thingstätte and Polish Monument to Silesian Insurgents

4. New in the Old. Competition for the Design of the Monument to Silesian Insurgents

- “Should the accent dominating the design constitute the crowning of the rock massif and be the main element attracting spectator’s attention from the open-air theatre, and at the same time destination of the ceremony in progress?

- Could this accent be presented at the background of the rock, or even could its edges be used as the motif of the sculpture itself?

- Is the interior of the valley where the open-air theatre is located spacious enough and do its dimensions make it possible to organize the ceremony and place the dominating accent here?

- (…) Do the existing natural and manmade structures fill their surroundings to a sufficient extent and would they be enough to serve as background for introducing the artistic structures of sculptures as the reflection of a desired and wanted symbol here, or should it be treated as necessary, in order to complement the existing structures, for the dominating accent to represent prevailing characteristics of an architectural work of art?

- (…) what should be considered the most appropriate representation of the symbol in order to constitute a simple, understandable and moving tone for every individual today and in the future?” (Frydecki and Michejda 1946, p. 6).

5. Xawery Dunikowski and His Vision of Commemorating Silesian Insurgents

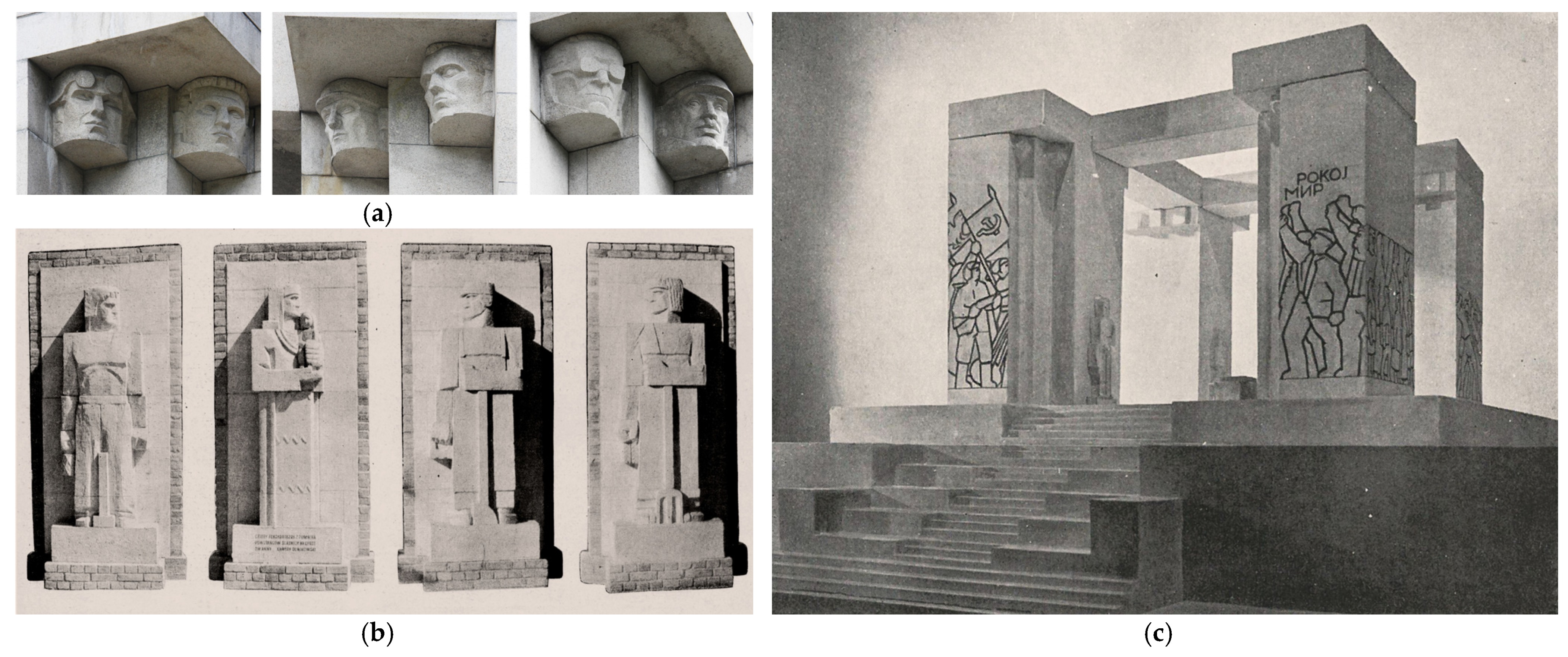

6. Architectural Staffage of the Monument to Silesian Insurgents

7. Xawery Dunikowski and the Method of Socialist Realism in Art

8. Epilogue, Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banaszkiewicz, Magdalena, Nelson Graburn, and Sabina Owsianowska. 2017. Tourism in (Post)socialist Eastern Europe. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 15: 109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartetzky, Arnold. 2006. Changes in the Political Iconography of East Central European Capitals after 1989 (Berlin, Warsaw, Prague, Bratislava). International Review of Sociologie 16: 451–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic, Rozmeri. 2011. Destructions of Monuments in Europe: Reasons and Consequences. International Journal of the Arts in Society 6: 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böck, Korbinian. 2017. «Bollwerk des Deutschtums im Osten». Das Freikorpsehrenmal auf dem Annaberg/Oberschlesien. RIHA Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezicki, Włodzimierz. 1955. Xawery Dunikowski—Twórca Pomnika Czynu Powstańczego. In Pomnik Czynu Powstańczego. Edited by Antoni Sylwester. Stalinogród (Katowice): Wydawnictwo Śląsk, pp. 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bullitt, M. Margaret. 1976. Toward a Marxist Theory of Aesthetics: The Development of Socialist Realism in the Soviet Union. The Russian Review 35: 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čamprag, Nebojša. 2018. International Media and Tourism Industry as the Facilitators of Socialist Legacy Heritagization in the CEE Region. Urban Science 2: 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, Amy. 2011. Alina Szapocznikow and her Sculpture of plastic Impermanence. Woman’s Art Journal 32: 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Czepczyński, Mariusz. 2010. Interpreting post-Socialist Icons: From Pride and Hate towards Disappearance and/or Assimilation. Human Geographies 4: 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Desa Unikum. 2021. Available online: https://desa.pl/en/wyniki/modern-and-contemporary-sculpture-np8d/friendship-1954/ (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- deTar, Matthew. 2015. National Identity after Communism: Hungary’s Statue Park. Advances in the History of Rhetoric 18: S135–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Freikorps-Ehrenmal auf dem Annaberg. 1939. Das Freikorps-Ehrenmal auf dem Annaberg. Die Baukunst. Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich 1: 102. [Google Scholar]

- Dobesz, Janusz. 1999. Góra św. Anny—Symbol uniwersalny. In Sztuka Górnego Śląska na przecięciu dróg europejskich i regionalnych. Materiały z V Seminarium Sztuki Górnośląskiej odbytego w dniach 14–15 listopada w Katowicach. Katowice: Muzeum Śląskie, pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Flurkowski, Stefan. 1949. Dunikowski powstańcom śląskim. Wielkie dzieło nowoczesnej architektury pomnikowej. Odra 9: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Frydecki, Andrzej, and Tadeusz Michejda. 1946. Pomnik powstańca ślaskiego. Odra 19: 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Frydecki, Andrzej. 1946. Budujemy pomnik Powstańca Śląskiego na Górze św. Anny. Ogniwa 7: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Frydecki, Andrzej. 1982. 1922–1982—moje sześćdziesieciolecie (Pamiętnik ilustrowany). Wroclaw: Museum of Architecture in Wroclaw. [Google Scholar]

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. 2018. The Limits of Iconoclasm: Soviet War Memorials since the End of Socialism. International Public History 1: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboni, Dario. 2007. The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. London: Reaction Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gawroński, Sławomir, Dariusz Tworzydło, Kinga Bajorek, and Łukasz Bis. 2021. A Relic of Communism, an Architectural Nightmare or a Determinant of the City’s Brand? Media, Political and Architectural Dispute over the Monument to the Revolutionary Act in Rzeszów (Poland). Arts 10: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, John R., ed. 1996. Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity 1996. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Groys, Boris. 1990. The Birth of Socialist Realism from the Spirit of the Russian Avant-Garde. In The Culture of the Stalin Period. Edited by Hans Günter. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 122–148. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, Nonette, and Magda Mueller, eds. 2018. Gender Politics and Post-Communism. Reflections from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gutkin, Irina. 1999. The Cultural Origins of the Socialist Realist Aesthetic, 1890–1934. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Herbert. 1985. Im Gleichschritt in die Diktatur? Die nationalsozialistische «Machtergreifung» in Heidelberg und Mennheim 1930 bis 1935. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Kanet, Roger E., ed. 2008. Identities, Nations and Politics after Communism. Oxon: Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, Stanislav, and Veronika Achikgezyan. 2017. Attitudes towards communist heritage tourism in Bulgaria. International Journal of Tourism Cities 3: 273–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C. Vaughan. 1973. Soviet Socialist Realism: Origins and Theory. London: The MacMillan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jassem, Michał, and Jan Minorski. 1948. Wystawa Ziem Odzyskanych we Wrocławiu. Architektura 10: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kiedy rozpocznie się. 1946. Kiedy rozpocznie się budowa Pomnika Czynu Powstańczego na Górze św. Anny. Wywiad z Ob. Wicewojewodą Płk. Ziętkiem. Nowiny Opolskie, July 28. [Google Scholar]

- Konkurs na projekt. 1945. Konkurs na projekt pomnika Powstańca Śląskiego. Gazeta Robotnicza, November 10. [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski, Juliusz. 1950. I Ogólnopolska Wystawa Plastyki. Przegląd Artystyczny 5/6: 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, Sergei. 2008. Semiotics of visual iconicity in Leninist ‘monumental’ propaganda. Visual Communication 7: 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźnik, Grażyna. 2016. Pomnik na Górze Świętej Anny i jego twórca ze szpikulcem. Dziennik Zachodni, April 29. [Google Scholar]

- Lurz, Meinhold. 1975. Die Heidelberger Thingstätte. Die Thingstättenbewegung im Dritten Reich. Kunst als Mittel Politischer Propaganda. Heidelberg: Schutzgemeinschaft Heiligenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Main, Izabella. 2008. How is Communism Displayed? Exhibitions and Museums of Communism in Poland. In Past for the Eyes. East European Representations of Communism in Cinema and Museums after 1989. Edited by Oksana Sarkisova and Péter Apor. Budapest: Central European University Press, pp. 371–400. [Google Scholar]

- Manifestacja Jedności. 1945. Ze zjazdu powstańców śląskich na Górze sw. Anny. Trybuna Robotnicza, July 2. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, Eric. 2004. The Cult of Art in Nazi Germany. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Irina. 2019. Vilnius memoryscape: Razing and raising of monuments, collective memory and national identity. Linguistic Landscape 5: 248–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalewicz, Magdalena. 2020. Rethinking Socialist Realism. Art in America 108: 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Muchina, Wiera. 1952. Obraz i temat w rzeźbie monumentalno-dekoracyjnej. Przegląd Artystyczny 5: 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Murawska-Muthesius, Katarzyna. 1996. Curator’s Memory: The Case of the missing “Man in Marble”, or the Rise and Fall of Socialist Realism in Poland. In Memory & Oblivion, Paper presented at the XXIXth International Congress of the History of Art, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1–7 September 1996. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 905–12. [Google Scholar]

- Niewczesna. 1945. Niewczesna obrona niemczyzny na posiedzeniu Woj. Rady Narodowej. Gazeta Robotnicza, August 1. [Google Scholar]

- O rzeźbie. 1952. O rzeźbie monumentalnej. Przegląd Artystyczny 6: 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ochman, Ewa. 2010. Soviet war memorials and the re-construction of national and local identities in post-communist Poland. The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity 38: 509–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomnik poległych. 1945. Pomnik poległych powstańców śląskich. Gazeta Robotnicza, May 26. [Google Scholar]

- Pomnik Powstańców. 1945. Pomnik powstańca Śląskiego na Górze św. Anny. Gość Niedzielny 30: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Pomnik Powstańców. 1946. Pomnik Powstańców na Górze Św. Anny. Gazeta Robotnicza, August 18. [Google Scholar]

- Przed manifestacją na Górze Św. Anny. 1946, Gazeta Robotnicza, May 15, 13.

- Rozpoczęto prace. 1945. Rozpoczęto prace przy budowie pomnika Powstańca śląskiego. Gazeta Robotnicza, August 24. [Google Scholar]

- Sokorski, Włodzimierz. 1978. Xawery Dunikowski. Warszawa: Iskry. [Google Scholar]

- Sprawozdanie. Sprawozdanie z działalności Komitetu Wykonawczego Budowy Pomnika Czynu Powstańczego na Górze św. Anny pow. Strzelce Opolskie za czas od 1945 r. do dnia 31 sierpnia 1955 r. (State Archive in Katowice, zespół: 12/274/0, seria: 5, jedn.: 412).

- Treter, Mieczysław. 1924. Ksawery Dunikowski. Próba estetycznej charakterystyki jego rzeźb, Lwów: H. Altenberg.

- Tworkowski, Srefan. 1954. O pomnikach. Przegląd Artystyczny 1: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Paul. 2008. The Afterlife of Communist Statuary: Hungary’s Szoborpark and Lithuania’s Grutas Park. Forum for Modern Language Studies 44: 185–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wystawa. 1946. Wystawa projektów pomnika powstańca na Górze św. Anny. Trybuna Robotnicza, April 11. [Google Scholar]

- Xawery Dunikowski i jego uczniowie. 1956. Xawery Dunikowski i jego uczniowie. Wystawa rzeźby i malarstwa 1945–1955. Warszawa: Sztuka. [Google Scholar]

- Żakiej, Tadeusz. 1947. Na Górze św. Anny stanie wielkie dzieło pomnik Powstańca Śląskiego. W pracowni twórcy pomnika profesora K. Dunikowskiego. Trybuna Robotnicza, February 14. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomaszewicz, A.; Majczyk, J. In a Time Loop: Politics and the Ideological Significance of Monuments to Those Who Perished on Saint Anne Mountain (1934–1955, Germany/Poland). Arts 2021, 10, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010017

Tomaszewicz A, Majczyk J. In a Time Loop: Politics and the Ideological Significance of Monuments to Those Who Perished on Saint Anne Mountain (1934–1955, Germany/Poland). Arts. 2021; 10(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomaszewicz, Agnieszka, and Joanna Majczyk. 2021. "In a Time Loop: Politics and the Ideological Significance of Monuments to Those Who Perished on Saint Anne Mountain (1934–1955, Germany/Poland)" Arts 10, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010017

APA StyleTomaszewicz, A., & Majczyk, J. (2021). In a Time Loop: Politics and the Ideological Significance of Monuments to Those Who Perished on Saint Anne Mountain (1934–1955, Germany/Poland). Arts, 10(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010017