1. Introduction

The operation of law in a system of separated institutions sharing powers demands a certain degree of cooperation between coordinate branches of government. Thus, Congress expects the federal bureaucracy will implement the laws it enacts, and strives to ensure that administrative implementation choices made subject to congressional delegation reflect legislative preferences (

Balla 1998). The complications that can arise when separate sets of officials are responsible for the initial determination and ultimate implementation of public policy are relatively simple to conjure. Moreover, the federal bureaucracy comprises a necessarily multifaceted host of institutions that leaves Congress with no shortage of administrative options when designing the contours of delegation and implementation. What, then, drives congressional choices regarding the implementation of law?

Amongst the most prominent dilemmas in institutional politics is the principal-agent question underlying congressional decisions about delegation. Numerous scholars have asked when, and under what conditions, agents in the federal bureaucracy may be trusted to implement policy consistent with congressional preferences (

Balla and Wright 2001;

Epstein and O’Halloran 1999), as well as the means by which Congress incentivizes bureaucratic cooperation (

Bawn 1995,

1997;

Whitford 2005). Consideration of the agency loss problem that inheres when legislators rely on bureaucrats to carry out congressional directives has tended to focus on the extent to which common characteristics between legislative and executive branch officials drive expansions or contractions of delegated authority (

Bertelli and Grose 2011;

Hammond and Knott 1996;

Volden 2002). This emphasis is reasonable, given that questions of delegation and implementation immediately direct attention toward inter-institutional relationships. In this article, however, I approach the congressional implementation dilemma in a manner that underscores instead the intra-legislative dynamics of delegation by offering an analysis of congressional delegation to the bureaucracy that centers on political conditions in the legislature itself. I seek primarily to answer two questions: (1) when does Congress concentrate implementation authority in fewer administrative agencies?; and (2) are legislative choices regarding the concentration of delegated authority driven by the congruence of intercameral ideological preferences?

I argue and find that when Congress enacts laws delegating implementation authority to the bureaucracy, legislators concentrate implementation powers in fewer agencies given greater levels of ideological congruence between pivotal actors in the House and Senate, respectively. I posit that increased concentration under such circumstances is driven by an expectation that legislators prefer to share responsibility for policy choices with as few other officials as possible under conditions of intercameral ideological proximity. By examining every significant legislative enactment that delegates authority to at least one administrative agency from 1947–2012, I am able to consider laws enacted under a wide variety of political, social, and economic circumstances. This analysis borrows elements from the theoretical framework of pivotal politics (

Krehbiel 1998), and to my knowledge, this is the first article to consider how the bicameral nature of congressional politics impacts questions of concentrated delegation and implementation responsibilities in the bureaucracy. Likewise, my analysis includes a novel independent variable to examine this question that measures intercameral ideological proximity.

As political and technological circumstances lead to increasingly expansive bureaucratic influence over the implementation of federal policy, there is growing normative concern regarding the origins and scope of administrative authority (

Hill 1991). The analysis presented here is intended to supplement existing conceptions of how the bureaucratic responsibility to implement federal law is distributed by examining the legislative origins of concentrated administrative implementation powers. My findings suggest that intercameral ideological proximity results in more concentrated delegation choices, thereby reducing the number of administrative agents responsible for implementing public policy.

2. An Exception to the Rule: Concentrated Authority in American Government

Scholars of American institutional design typically emphasizes the degree to which public authority in American government is distributed among many actors and institutions. Such emphasis reflects a system characterized by both vertical (e.g.,

McCann 2016) and horizontal (e.g.,

Epstein and O’Halloran 1999) fragmentation of policy-making power, which is shared between national and state governments, and between legislative, executive, and judicial institutions (

Barnes 2007). In this article, instead of positing a theory regarding the fragmentation of public authority, my intention is to reformulate the usual analysis by offering a theory about the limits of widely-dispersed policy-making power. By contrast, I consider the extent to which constraints on fragmented authority are themselves determined by aspects of institutional design, and in particular how those limits relate to the bicameral dynamics of American legislative politics.

There is a long tradition of scholarship in legislative politics that examines the methods and effectiveness of congressional attempts to exert control over the bureaucracy. Such research tends to examine the institutional tools at the legislature’s disposal to mitigate the problem of agency loss after implementation authority is delegated to administrative agencies. Congress can influence agencies’ composition, function, and capacity by an assortment of means, such as the employment of congressional oversight committees (

Weingast and Moran 1983), the legislative role in the nomination and confirmation process for political appointees (

Moe 1985), allocational decisions in the federal budget (

Fenno 1966;

Wildavsky 1964), and the enactment of statutory delegations of authority to bureaucracy, including the enabling statutes that create agencies in the first place (

Frug 1984;

Noah 2000). The nature of these delegation choices may also be impacted by the employment of so-called “dual” delegation attending delegatory decisions in Congress, first to substantive congressional committees and then to administrative agencies (

DeShazo and Freeman 2003), as well as (if conditionally so) by the electoral cross-pressures on legislators (

Fox and Jordan 2011). Other research has considered how agency-level factors and the risk preferences of delegating officials may undergird an informational rationale for legislative delegation to the bureaucracy (

Bendor and Meirowitz 2004), as well as how delegation may function as a corrective mechanism for governmental accommodation of policy drift (

Callander and Krehbiel 2014). As a general matter, the existing scholarship reflects the wide range of oversight mechanisms available in the principal-agent relationship between legislatures and bureaucracies, as well as the different sorts of incentives bearing on legislators charged with making delegation choices (

Holmstrom and Milgrom 1991). Much existing research stands for the proposition that legislative efforts at incentivizing or inducing bureaucratic compliance are reasonably effective (

McCubbins and Schwartz 1984;

Weingast 1984; contra

Carpenter 1996;

Wilson 1980), and there is little disagreement regarding whether Congress at least occasionally attempts such efforts at management and direction vis-à-vis agencies with delegated authority.

Despite extensive attention paid to the mechanisms of inter-institutional influence discussed above, comparatively less consideration has been given to the possibility that Congress elects to concentrate or fragment delegated authority among federal agencies and bureaus as an instrument of political control. In this article, I consider a specific, important subset of delegation choices, and subsequently present an empirical analysis that reflects a test of my theory regarding the scope of delegated authority among significant congressional enactments. There are, moreover, several notable exceptions to the general lack of work on concentration of delegated authority. While they consider bureaucratic insulation, rather than concentration or fragmentation as such,

Epstein and O’Halloran (

1999) examine delegation choices and find that Congress is more likely to delegate implementation authority to the bureaucracy “in exactly those areas where the political advantages of doing so outweigh the costs” (p. 232), and announce a variety of political conditions under which broadly delegated authority becomes more likely. Likewise,

Lewis (

2003) examines the politics of agency design and insulation from a presidential perspective and contrasts the motivations of the chief executive with those of legislators making delegation choices, arguing that Congress and the President are in an ongoing tug of war for political control of the bureaucracy. In other, more recent work,

Farhang and Yaver (

2016) consider questions of concentration and fragmentation directly by examining congressional delegations to the bureaucracy from 1947–2008 and find that fragmentation of delegated power is more likely given conditions of divided party government across both chambers of Congress and the Presidency. Here, alternatively, I present a theory that builds on prior theories of bureaucratic insulation and fragmented delegation regarding the conditions under which Congress concentrates implementation authority in fewer agencies, explicitly informed by the intra-legislative dynamics of intercameral ideological proximity. As opposed to the existing research that has tended to approach questions of delegation by considering intercameral dynamics only to the extent that they bear on binary definitions of unified or divided government, I employ a deliberately intercameral approach that considers whether ideological congruence between the chambers of a bicameral legislature in a separation of powers system results in laws that concentrate authority in fewer bureaucratic institutions. These theoretical developments motivate my explanation of how closer proximity of intercameral ideological preferences is positively associated with concentration of implementation authority among bureaucratic institutions. This mode of analysis permits me to make a series of inferences about the degree to which concentration of authority in American law, however rare, is driven by the ideological composition of Congress.

3. Intercameral Ideological Congruence and Concentrated Delegation

Two legislative enactments with significant allocational consequences serve broadly to illustrate the question motivating this article. Although there exist differences in the temporal and political circumstances surrounding the enactment of both laws, they nevertheless serve to animate how Congress structures the implementation of federal policy in manners that go unexplained by existing theories regarding the conditions under which legislators concentrate or fragment implementation authority. On 24 March 1948, the House concurred in the Senate’s final amendments to H.R. 4790, a bill otherwise known as the Revenue Act of 1948, which had passed the Senate two days prior. Ultimately enacted via an override of President Truman’s veto, the legislation ordered decreases to individual rates in the Internal Revenue Code, and provided for several additional tax exemptions (

Tempalski 2006). In crafting this legislation, designed to relieve the collective tax burden as demand for military spending waned after the end of the Second World War, Congress formulated an implementation scheme that relied only on cooperation by the Department of the Treasury (

Yang 2007). Nearly six decades later, on 1 February 2006, the House agreed to the final version of S. 1932, styled the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. This sweeping legislation also resulted in adjustments to federal spending levels, primarily by modifying coverage structures in the Medicaid and Medicare programs (

Wilson 2007). In delegating authority to implement this bill, by contrast, Congress spread responsibility for its execution across some thirteen federal agencies. Why did the congressional approach to delegating implementation powers differ so dramatically between these two enactments?

Attempting to account for such variation in the distribution of delegated authority by examining whether there was unified or divided government across the chambers of Congress and the Presidency proves insufficient. Here, I offer a theory that considers how intra-legislative factors bear on delegated implementation authority across the bureaucracy broadly. Whereas prior research suggests that divided government drives the fragmentation of delegated implementation power, in this instance, implementation authority was concentrated in only one federal agency by the Revenue Act of 1948—under conditions of divided government—while such responsibilities were fragmented across thirteen agencies despite unified government when the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 was enacted. This binary conception of divided versus unified government, however, neglects to take into account the possibility of ideological heterogeneity within party caucuses in Congress. For example, despite party control of government being divided between Republicans in the Eightieth Congress and Democratic President Truman in 1948, the pivotal legislators in the House and Senate were reasonably similar in ideology—in fact, based on a comparison of scores that use legislators’ roll call votes to estimate their ideological preferences (

Poole and Rosenthal 1985), the ideological “distance” between pivotal legislators in the House and Senate during the Eightieth Congress was the fifth smallest of the thirty-three sessions of Congress from 1947–2012. Contrarily, when the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 was enacted, the ideological space between the House and Senate was relatively substantial—the fourth largest of any Congress during the time period examined here—despite the Republicans controlling both chambers of Congress and the Presidency. This anecdote suggests that intercameral ideological congruity may be an important factor in predicting the distribution of delegated implementation authority in federal statutory design.

I theorize that greater proximity in ideology between the House and the Senate will be associated with increased concentration in policy implementation authority. This builds on existing work by considering how intra-legislative institutional forms affect the extra-legislative construction of federal policy. Congressional choices regarding delegation to the bureaucracy usually implicate assumptions about legislative attempts at political control, animated by principal-agent concerns and the potential for agency loss, or other considerations bearing on legislators such as the electoral incentive. Additionally, there have been a number of social and economic developments that manifest politically in changes in the incentive structure for legislators to delegate policy authority to administrative agents. For example, the expansion of bureaucratic authority during the twentieth century altered the political opportunity structure for legislative delegation in a manner that requires any empirical consideration of delegatory choices to account for the possibility that such choices are timebound. Further, the growth of federal authority more generally may impact how Congress chooses to design the implementation of policy regimes. Here, while I am unable to consider how characteristics of individual agencies may impact delegation choices as I analyze delegatory decision-making at the level of the congressional enactment, I examine broadly how implementation powers are concentrated or fragmented across bureaucratic institutions. I argue that concentrating implementation authority in fewer administrative agencies and bureaus provides Congress with an institutional means for minimizing agency loss. The fewer bureaucrats there are responsible for implementing enacted congressional directives, the fewer opportunities there can be for ideologically or politically recalcitrant administrators to frustrate the purposes of legislative programs. In essence, each bureaucratic institution to which Congress delegates some measure of implementation power when designing legislation functions as a sort of veto player with profound (if non-absolute) influence over the likelihood that policy regimes operate as Congress originally intended. As a result, and because reliance on the bureaucracy to execute at least some features of legislation is virtually unavoidable when governing in the modern administrative state, legislators seeking to ensure that enacted policies are implemented consistent with their own preferences must find ways to write laws that maximize favorable compliance outcomes among bureaucratic recipients of delegated authority. Reducing the number of potentially nonacquiescent administrators by concentrating implementation powers in fewer agencies represents one such legislative tactic. Although situated alongside existing determinants of concentrated implementation authority, my theory contends that intercameral ideological congruence explains some portion of delegated authority to the bureaucracy

My theory posits, however, that there exist political constraints—internal to the legislature itself—on the conditions under which legislators in a bicameral institution will express a willingness to concentrate implementation authority for enacted programs. This argument of mine relies heavily on the theoretical framework of pivotal politics (

Krehbiel 1998), which suggests that it is the distribution of ideological preferences within (and, by extension, across) institutions—along with those institutions’ decision rules—that determines their policy outputs. According to the theory, pivotal actors are those at the ideological “tipping points” within the institution, whose preferences determine the collective policy preference for the body. For the purposes of this article, I consider only the preferences of pivotal actors in Congress in keeping with the approach taken in other inter-institutional contexts that do not employ the preferences of the President in their analysis of legislative decision-making (see, e.g.,

Menounou et al. forthcoming). According to my argument, and all else equal, enacted legislation will probably be closer to the ideological preference of the pivotal member of one chamber given increased proximity between that member’s ideal point and the ideological preference of the pivotal member in the

other chamber. To express this more concretely, it is more likely that legislation will contain conservative (or moderate, or liberal) policy enactments if the pivotal members in both chambers of Congress are conservative (or moderate, liberal) than otherwise. Because, then, pivotal legislators in a bicameral system are ultimately more likely to prefer policy outcomes given minimal ideological distance between themselves and pivotal legislators in the corresponding chamber, it follows that legislators operating under such conditions of ideological proximity would view agency loss resulting from unsatisfactory policy implementation by bureaucrats more negatively than were the policies more remote from the legislators’ preferences. Indeed, facing the enactment of laws that specify policy programs they regard as suboptimal, legislators may even positively anticipate the chance of agency loss at the hands of the bureaucracy and seek to avoid concentration of implementation powers. These considerations should motivate members of bicameral legislatures to concentrate authority delegated to the bureaucracy among fewer agencies—i.e., to “put all their eggs in one basket”—given ideological congruence between the two chambers.

The notion that legislators will concentrate implementation authority more frequently under conditions of minimal intercameral ideological distance is not intended to diminish the importance of the ongoing inter-institutional dynamics inherent in congressional efforts to design legislation that the executive branch is willing and able to implement and that withstands judicial scrutiny. Instead, however, I seek to offer an additional explanation for the legislative construction of bureaucratic authority that is internal to the legislature itself. By focusing on the bicameral origins of concentrated delegation by Congress, I establish a theoretical connection between the ideological proximity of the legislature’s two chambers and the designated scope of delegated implementation authority that suggests close congressional management of administrative power. Likewise, the theory and analysis presented here are not intended to negate or refute the possibility that there exists a panoply of concerns that influence legislative decisions whether and how to delegate authority to the bureaucracy. For instance, legislators might consider the availability of oversight mechanisms, specificities and strictures of the administrative process, the ideology of bureaucrats responsible for implementation, the type of policy at issue, and the institutional design of the administrative body. These factors doubtless impact the legislative design of administrative implementation authority, and a theory of how intercameral ideological congruence leads to concentrated bureaucratic implementation power does nothing to theoretically diminish their importance. Further, I do not contend that the partisanship or preferences of officials in the executive or judicial branches are irrelevant for determining the conditions under which the bureaucracy’s responsibility to execute laws will be either concentrated or diffuse. Rather, the theory implies that certain contours of the bureaucracy’s implementation authority are circumscribed prior to coming out of the proverbial starting gate by legislators concerned with ex ante bureaucratic delegation, to the extent they are determined by the relative distribution of ideological preferences among legislators choosing which and how many agencies will carry enacted laws into effect.

To empirically assess this conceptualization of the association between intercameral ideological proximity and concentration of implementation authority in bureaucratic institutions, I develop the following testable expectation based on the observable implications of the theory. The expectations are summarized in the intercameral ideological congruence hypothesis:

Intercameral Ideological Congruence Hypothesis:

As the ideological distance between the House median and the Senate filibuster pivot more remote from the House median increases, the more agencies will be responsible for implementation authority in each instance of enacted legislation.

This hypothesis sets out the measurable consequences of my theory, and seeks to establish clearly the connection between intercameral ideological proximity in Congress and the concentration of implementation power in federal agencies. In the following section, I describe the empirical tests I employ before presenting the results of the analysis.

4. Data and Methods

To test my expectations regarding intercameral ideological congruence and concentration of policy implementation authority, I estimate several iterations of a Poisson regression model that examines the association between ideological proximity and the distribution of implementation authority across federal agencies. Poisson regression is methodologically appropriate for a countable dependent variable with a low arithmetic mean (

Coxe et al. 2009). The unit of analysis is at the level of the individual enacted law, and my sample includes all legislation from

Mayhew’s (

2005) dataset of important congressional enactments from 1947–2012.

1The dependent variable,

Number of Agencies with Implementation Authority (μ = 5.89) measures the number of federal agencies to which Congress has delegated implementation authority for each law in my sample. For the purposes of assessing the expectations suggested by my theory, legislation in which Congress has delegated implementation authority to more agencies is considered less concentrated, while legislation in which implementation power is delegated to fewer agencies is considered more concentrated. Descriptive statistics related to the dependent variable appear in

Table 1 below. In this table, I also include the percentage of laws from my sample delegating to each of the fifteen agencies to which Congress most frequently delegated implementation authority across my sample.

The dependent variable has been calculated as follows: I searched for and located each reference delegating authority to federal agencies in the text of each law in the sample, then added together the number of cabinet departments responsible for implementation and the number of independent agencies and other non-cabinet bureaus granted implementation authority. This involved performing a full text search of each law and searching for the words administration, agency, bureau, board, commission, department, and secretary (as well as sublexical constituent parts and variants of such words like “administr-” in order that the search captures references to administrators as well as administrations). I then counted the number of mentions of all these institutions (cabinet departments, independent agencies, and non-cabinet bureaus) receiving delegated authority to create the dependent variable. As such, this variable reflects the number of administrative agencies (at the cabinet level and otherwise) responsible for implementing policy. Because I coded delegation across the laws in this set by hand, I ensured that none of the references to agencies with delegated authority in the sample were “negative” mentions in which Congress was forbidding an agency from implementing policy or transferring implementation authority away from an agency or bureau. This approach differs from that in earlier work that counts both institutions and actors in measuring policy implementation authority (

Farhang and Yaver 2016), while data from other recent prominent studies of delegation account for the level of executive discretion in each federal law that delegates policy authority (

Epstein and O’Halloran 1999). These data are not publicly available but generally consider, as I do here, the distribution of implementation power across institutions as a baseline measure of concentrated delegation, but with a particular focus on constraints imposed by administrative procedures.

The independent variable of interest,

Senate-House Distance, is intended to measure the intercameral congruence of ideological preferences. This variable measures the absolute value of the difference between (1) the median first dimension DW-NOMINATE score in the House and (2) the first dimension DW-NOMINATE score of the pivotal Senator ideologically least proximate from the House median.

2 As discussed in the previous section, I expect that greater values of

Senate-House Distance will be associated with delegation to more agencies, i.e., with less concentrated implementation.

I include several other independent variables to account for the political, administrative, and economic circumstances that might lead Congress to design legislation that concentrates implementation authority in fewer bureaucratic institutions. First, I include two aggregate measures of the partisanship in each chamber of Congress in each year to control for the possibility that members of one party or the other tend to favor concentrating implementation power in fewer agencies. These two variables are the Democratic Percentage in the Senate and the Democratic Percentage in the House, which are continuous measures of the percentage of seats held by Democrats in each chamber. Further, to account for the existing explanation that congressional choices whether to concentrate authority are driven by control of the elected branches of government by one party, I include a binary variable indicating whether there was Unified Government in each year, coded 1 if one party controlled the House, the Senate, and the Presidency, and 0 otherwise. This acknowledges the possibility that Congress will take into account the partisanship of the President when making choices regarding delegation to the bureaucracy.

I also include two variables related to the administrative circumstances surrounding each significant enactment in my sample. Because legislative choices about concentrated delegation may depend on the capacity of the executive branch to implement congressional directives, I include a variable representing the size of the

Executive Branch Workforce during each year, which is the number of federal executive branch employees, measured in tens of thousands.

3 Likewise, to account for the clerical explanation that Congress delegates implementation powers to more agencies when laws are longer, I include a variable measuring the

Length of Legislation in pages for each significant legislative enactment.

4 Finally, to control for the possibility that Congress makes implementation decisions subject to economic constraints—and thus, delegates implementation authority to fewer agencies when macroeconomic circumstances are generally worse—I include a variable,

Debt per GDP, which measures the United States’ annual public debt as a percentage of the national gross domestic product for each year in my sample.

In addition to the primary version of the model described in the foregoing paragraphs, designated Model 1a in the results that follow, I estimate two additional iterations of the model that appear in the following section. In the first additional model, designated Model 1b, I include an interaction term to examine whether the effect of Senate-House Distance on concentrated versus fragmented implementation authority depends on partisan control of each chamber. This additional variable is designated Senate House-Distance with Unified Congress and is calculated by interacting Senate-House Distance with an indicator variable coded 1 if both chambers of Congress are controlled by the same party, and 0 otherwise. This will permit me to assess whether any effect of intercameral ideological congruence on concentration of implementation power is conditional on unified partisan control of the House and Senate. Last, in a second additional model, designated Model 1c in the table below, I include fixed effects for each decade in my sample, in order to account for any variation or patterns in concentration of implementation authority based on unobservable temporal characteristics. All three models also include fixed effects for the policy area governed by the legislation.

5. Results: Intercameral Ideological Congruence Drives Concentrated Delegation

The results of my analysis appear in

Table 2 below. Broadly speaking, these results offer strong support for the intercameral ideological congruence hypothesis. Across all three iterations of the model described in the preceding section, the primary independent variable

Senate-House Distance is statistically significant, and greater levels of intercameral ideological congruence are associated with increased concentration of implementation authority. In other words, the more proximate the ideological preferences of pivotal legislators in the Senate and the House, the fewer agencies receiving delegated implementation authority from legislation enacted by such Congress.

In the primary model (designated 1a in

Table 2), greater values of

Senate-House Distance are associated with increases in the estimated number of agencies to which Congress has delegated implementation authority when drafting legislation. This central result is robust to a number of alternative specifications of this primary model, including Model 1b—in which I estimate the effects of

Senate-House Distance on concentrated delegation for conditions of divided and unified control of Congress separately—and Model 1c—in which I include fixed effects at the decade level to account for unobservable temporal circumstances that might impact delegation choices in Congress.

5 Not only is there a statistically discernible association between

Senate-House Distance and

Number of Agencies with Implementation Authority across all three specifications presented here, the results in Model 1b suggest that the tendency for Congress to concentrate implementation authority in fewer agencies given conditions of ideological congruence between pivotal members of the Senate and House holds no matter whether there is unified or divided control of Congress. Although the delegatory consequences of ideological congruity may be diminished under conditions of a unified legislature since the magnitude of the effect for

Senate-House Distance with Unified Congress is smaller than for

Senate-House Distance (which in Model 1b serves to estimate the effect of intercameral ideological proximity given divided party control of Congress because of the interaction term), this nevertheless suggests that the distribution of ideologies among members of Congress has an impact on the manner in which implementation authority is delegated across agencies independent of whether there is unified control of the executive and legislative branches. In

Table A1 in the

Appendix A, I estimate the same models that appear in the text without policy area fixed effects, and the results are substantively comparable in direction and magnitude.

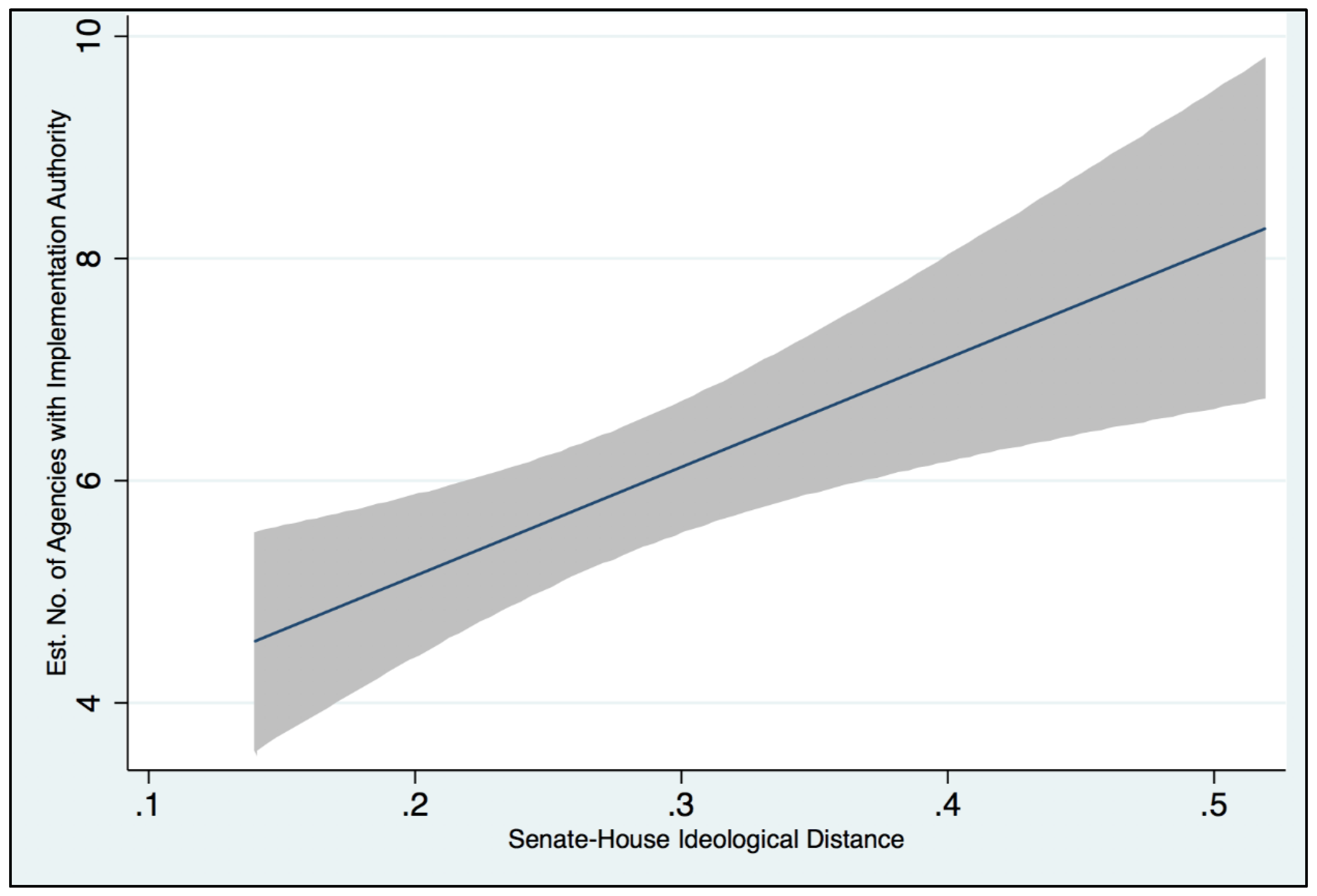

The association between

Senate-House Distance and the concentration of delegated authority is further illustrated in

Figure 1. The figure is based on the results from Model 1a and displays the estimated

Number of Agencies with Implementation Authority given a range of values in ideological distance between pivotal members of the Senate and House. The results suggest that intercameral ideological proximity is an important factor in predicting the concentration or fragmentation of implementation authority delegated to the bureaucracy in federal statutes. For example, based on these results, moving from a value one and a half standard deviations below the mean (0.12) to a value one and a half standard deviations above the mean (0.42) for

Senate-House Distance, the estimated number of agencies receiving delegated authority moves from 3.96 to 6.31. The results suggest that all else equal, congressional management of structuring implementation powers among bureaucratic institutions is strongly associated with the distribution of ideological preferences within Congress.

A number of the other independent variables accounting for the tendency of Congress to concentrate or fragment implementation authority are statistically significant. For example, in Models 1a and 1b, increases in the size of the executive branch workforce and the length of enacted legislation are associated with delegation to a greater number of agencies. This association between the number of executive branch employees and concentrated delegation, however, vanishes entirely upon the inclusion of decade fixed effects, suggesting that the size of the executive workforce is correlated with some unobserved temporal characteristics operating in the background of this analysis. There is also a strong relationship between the percentage of Democrats in each chamber of Congress and delegation outcomes, although the effects move in different directions in the Senate versus the House. This is likely related to ideological heterogeneity among party caucuses over the time period covered in my sample. Perhaps more importantly, the categorical variable Unified Government is only significantly associated with concentration or fragmentation in Model 1b, but otherwise fails to attain statistical significance. In Model 1b, the results do suggest there is a weak association between the existence of unified government and concentration of implementation authority in the bureaucracy. My findings imply, however, that the effects of unified government on concentrated delegation among the 386 statutes in my sample are attenuated to near imperceptibility once I control for other political and administrative factors including but not limited to intercameral ideological proximity. In general, the results suggest that intra-congressional ideological dynamics are brought to bear on the distribution of delegated authority across bureaucratic institutions independent of other political and administrative determinants of concentration and fragmentation.

6. Conclusions

This article continues a strand of scholarship examining the causes of concentrated implementation authority in federal policy-making, and represents the first work to consider how ideological proximity between the chambers of Congress impacts the concentration of enforcement power in fewer national administrative agencies.

My theory and findings suggest a number of fruitful avenues for future research regarding the causes and consequences of concentrated implementation power. For example, if the congressional intent in concentrating authority in fewer agencies under conditions of intercameral ideological proximity is indeed motivated by a desire to see policy enacted with minimal agency loss, is this approach effective? Despite some challenging issues regarding metrics of bureaucratic outputs and their relationship to congressional aims, investigation into the subject might consider whether policies enforced by fewer administrative agencies are indeed implemented in a way more consistent with the preferences of pivotal members of the House and Senate. Likewise, further consideration of the subject should do its best to take into account the variegation of policy types for which Congress and the federal bureaucracy are responsible. Future research might, for instance, employ measures of agency ideology to see if there exists administrative resistance to the directives expressed in legislative delegations of authority, and to establish whether members of Congress take actual or perceived agency preferences into account when making choices about the distribution of delegated implementation power. It would also behoove future scholars to take into account certain textual and rhetorical characteristics of legislation that delegates implementation authority to the bureaucracy. Perhaps even employing innovative techniques such as automated content analysis and other tools generally borrowed from computational linguistics, subsequent consideration of congressional delegation choices would do well to examine the textual mechanics by which Congress delegates implementation powers in policy design to the bureaucracy—namely, by providing answers to questions regarding whether the length of text delegating authority is associated with expansions in the scope of administrative powers, and how legislators structuring delegation to the bureaucracy employ certain linguistic features to place constraints on administrative implementation capacity. Last, future scholars would do well to employ a research design to examine questions of delegation to the bureaucracy that is equipped to take into account agency-level factors that may impact delegatory choices among legislators. Namely, future work could consider how delegation choices are associated with the range and types of bureaucratic institutions available to receive delegated implementation authority from Congress.

The prevailing normative criticism of bureaucratic governance is that an accountability deficit results in the divorce of policy outcomes from popular preferences. If, so the argument goes, the people elect legislators to design policies that reflect their own preferences, then unilateral alterations made to congressional enactments by unelected bureaucrats represent a subversion of the democratic will. Hollowed out or not, however, the administrative state is here to stay in one form or another, and as a result, the implementation of federal statutes will continue to rely on satisfactory performance from a cooperative (or coerced) bureaucracy. One manner in which legislators can circumvent the problem of agency loss is to distribute implementation powers among fewer bureaucratic institutions, and my findings indicate such concentrations of authority are more common given ideological congruity between the two chambers of a bicameral legislature. This suggests legislative attention to ex ante choices regarding delegation to the bureaucracy, and implies the need to continue examining the relationship between bureaucratic authority and legislative design.