1. Introduction

A central curiosity in the operation of the American regulatory state lies with its hybrid structure: one that is defined not only by centralized, bureaucratic approaches to policy implementation, but also more decentralized actions such as lawsuits brought by private citizens in the courts. While this first approach is perhaps most easily aligned with conceptions of how regulation takes place in the U.S., the second is more commonly obscured and overlooked. However, as private litigation rates have soared in the U.S. over the last half-century, scholars of regulation and law have done much to reconceptualize and reframe this growing activity as not simply the aggregation of many private acts of grievance, but as an increasingly pivotal means for the enforcement of policy—and one, importantly, that has been crafted, emboldened, and developed by political elites to sidestep the oftentimes weak administrative processes granted to agencies to enforce the law.

The American regulatory regime, then, is rooted not only in the day-to-day activities of bureaucratic agencies tasked with regulating social and economic interactions, but also those of private citizens who bring violations of policy to the courts to be addressed and remedied. The complexity of this system, however, leaves students of policy implementation with a set of questions about how this hybrid, administrative–legal model of regulation operates in practice. Are more administrative methods preferred for some types of regulatory activity, and private legal remedies for others? Does this vary from policy area to policy area? From one set of political interests to another? According to what set of criteria, in other words, are determinations made about how (through which pathway) policy should be enforced in the U.S., and by whom are they made?

While much of the current research focuses at the elite level—exploring how and why political actors in Congress, the Executive Branch, and the courts utilize these approaches on different public policies—there is little research that examines

public attitudes toward how policy is enforced in the U.S. However, there are real reasons we would expect the public to have meaningful opinions on these processes. In public opinion polling, Americans express strong attitudes toward the federal agencies that enforce policy (

Pew Research Center 2018) and about the litigation process itself (

Galanter 1983,

1998;

Haltom and McCann 2004). Likewise, these topics have been highly politicized over the last half century, especially by the Republican Party’s frequent critiques of “big government” solutions to social and economic problems and the “explosion” of litigation brought by the public in the courts that was publicly campaigned against in the form of the tort reform movement. Given the salience of these topics among the public, as well as the fact that the public is an important partner in these processes—whether through democratic responses to regulatory policy or through its key, active role in the legal pathway—this paper aims to integrate public attitudes into this discussion of approaches to regulation.

Tapping into popular conceptions of “big government,” privatization, lawsuits, and the tort reform movement, this paper uses original data from a series of vignette-based experiments in the 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey to examine the nexus of these opinions in relation to several different substantive issue areas (employment discrimination, disability accommodation, the environment, food safety, and mortgage lending), presenting a different picture of ideological and regulatory preferences than that which typically characterizes the political elite. In doing so, we offer one of the first studies that adjudicates the boundaries of public attitudes on litigation and bureaucratic regulation in the U.S., offering implications for how elites might approach the design of policy implementation for different issue areas.

2. Approaches to Regulation in the U.S.: An Institutional Perspective

How and through what mechanisms policy is enforced in the U.S. is a critical question for studies of regulation—a question made even more critical given accounts of the limited administrative capacity of many agencies. The literature on the bureaucracy is replete with accounts of modern regulatory agencies divested of many of the formal powers, authorities, and resources necessary to carry out strong command-and-control enforcement actions. Deemed exceptional among advanced democracies for their relative weakness (

Lieberman 2005), some have traced these limitations to a long-term distrust of centralized administrative authority that goes back to institutional compromises at the foundation of the U.S. (

Huntington 2006) and an enduring set of liberal traditions that eschew administrative intervention by the federal government (

Hartz 1955). Caught in the crossfire of political and institutional competition embedded in the separation of powers system, American agencies have emerged stripped and disempowered relative to their peers.

However, within this discussion, a question remains: how is policy to be enforced with such a historically and comparatively enfeebled bureaucracy? Some studies have pointed to spurts of administrative growth which develop in response to localized crises and demands, but never quite meet the capabilities of other western democracies (

Bensel 1990;

Carpenter 2001;

Skowronek 1982). However, a growing set of literature has turned its focus to the more institutionally creative ways that political actors navigate this weak administrative landscape. In particular, this scholarship points to the increasing role played by private litigation as a critical engine of policy enforcement in the U.S., examining how political actors in Congress, interest groups, and agencies, themselves, have learned to harness the enforcement powers located in the courts to meet regulatory demands (

Farhang 2010;

Frymer 2003;

Kagan 2001;

Mulroy 2018).

Citing the integration of an atypical, hybrid administrative–legal model of regulation in the implementation designs of several new policies during the mid-20th Century, these studies show how elite political actors learned to supplement administrative capacity using incentives that mobilize private citizens to prosecute violations of policy in the courts. Coming off the boom of policy proliferation and regulatory expansion during the New Deal period, by the mid-20th Century, there was increased demand for governmental regulation on an expanded set of social and economic activity. However, there was also an important roadblock in the form of a congressional coalition of southern Democrats (who viewed federal interventions in local affairs as a threat to the region’s existing racial hierarchy) and Republicans (who were ideologically opposed to strong federal regulation) that worked successfully to block the creation of strong federal administrative powers on these new policies (

Katznelson and Mulroy 2012).

However, these policies were also defined by a key legislative compromise. In lieu of strong administrative authority, liberal Democrats and this blocking coalition in Congress agreed to create a private right to sue on many policies, giving private citizens standing to bring lawsuits in the courts. Few initially thought this pathway would work.

1 Conscious of how expensive, time-intensive, and difficult litigation can be for private citizens, elites in Congress, the courts, agencies, and interest groups, as revealed by new scholarship, consciously developed strategies to overcome these barriers and make litigation a more feasible option for private citizens. In result, the modern American regulatory system is characterized by multiple pathways for policy enforcement: through administrative processes carried out by agencies, and another largely enacted through private litigation in the courts.

This paper joins these studies, seeking to understand the implications of the development of this hybrid system of policy enforcement in the U.S. However, while most inquiries have thus far focused on how elite, institutional actors navigate this system, we turn our analytical focus to an underexplored but critical set of actors in this story: the members of the public who are charged with the important task of bringing lawsuits in the courts. Knowing more about how public opinion operates in this context is critical for understanding the complex processes by which regulation takes place in the U.S., and by whom this is carried out, providing important lessons for crafting regulatory policy.

3. Approaches to Regulation in the U.S.: Public Attitudes

To study a regulatory system that relies, in part, on the active participation of private citizens, we argue, demands an examination of public attitudes toward policy enforcement. In addition to identifying elite preferences on the public–private, administrative–legal model of policy enforcement, it is critical to understand public attitudes about how policy is enforced in the U.S. Does it look favorably upon private litigation as a means of enforcing policy? Is it likely to support administrative approaches? How does the public respond, in other words, to public policy that utilizes one of these approaches, or the other?

In this study, we seek to know more about public attitudes on these different approaches to policy enforcement. While extant studies examine public opinion on regulation, agencies, and litigation, they have done so quite separately; addressing each topic in turn and at the expense of a more holistic approach recognizing the ways attitudes on these topics might fit together. Much of this is likely due to the nature of data surrounding these topics in public opinion polls, themselves. Many large national polls do not ask consistent questions on attitudes toward regulatory policy or agencies, but rather respond to critical moments of policy development or saliency before moving on to the next event. Polls measuring public attitudes toward litigation follow similar patterns, largely gauging opinion in response to, for instance, developments in the tort reform movement or instances of litigation run amok. We will go into more detail on this below, but before doing so, want to emphasize that many of these data limitations are driven by the types of questions that are being asked—specifically, those that focus more on attitudes toward particular actors (e.g., bureaucrats, private litigants), than on system-level preferences about how policy is enforced.

4. Public Opinion on Administrative Regulation

There is, first, the starting assumption that the public is preternaturally adverse to the bureaucracy and its regulation of social and economic activities.

Even Woodrow Wilson (

1887), in his famous treatise on the study of public administration, noted the deep incongruence that characterized the American democratic experiment—one that relied on public input and participation, and yet required the development of a strong, central administrative apparatus to take on the challenges of the day. Noting that “it is harder for democracy to organize administration than for a monarchy,” Wilson observed that America “has long and successfully studied the art of curbing executive power to the constant neglect of the art of perfecting executive methods,” such that “it has exercised itself much more in controlling than in energizing government” (207). Of the American public, Wilson counseled that “we go on criticizing” administrative authority “when we ought to be creating,” cautioning against the ways in which democratic will is seemingly at odds with administrative strength.

The lingering lessons of Wilson’s warnings about democratic opposition to bureaucratic authority are reflected in existing treatments of public opinion on regulation and governmental agencies. A substantial, though fairly scattershot, set of literature reports on the cynicism (

Berman 1997), distrust (

Houston and Aitalieva 2013;

Merton 1940;

Van de Walle 2004), and hostility (

Alvarez and Brehm 1996;

Kaufman 1981) respondents express toward different agencies and bureaucrats. Indeed, as some scholars suggest, there is an air of “theater” around this time-worn activity of critiquing the bureaucracy in America, one in which public discourse has contributed to perceptions of the bureaucrat as anti-hero in the great American narrative (

Terry 1997).

In the sections to follow, we address these common assumptions about public attitudes toward the bureaucracy in the U.S., but contextualize them within a larger framework that considers not just public reactions to what the government is or of whom it is composed, but how it enforces public policies. As such, we are interested in gauging public attitudes toward bureaucratic regulatory actions, but also—taking this full, hybrid model of regulation into account—the enforcement of policy by private citizens in the courts.

5. Public Opinion on Private Litigation

Public attitudes toward private litigation have received growing attention in the past several decades—especially in reaction to the “litigation explosion” taking place in the U.S. courts system. Starting in the 1970s, legal scholars identified a precipitous (and some argue, alarming) increase in private litigation rates. Warning that American society was afflicted with a “national disease,” researchers pointed to institutional and cultural explanations for the rapid proliferation of lawsuits in the courts—a rise that some attributed to a growing consensus within American society that problem resolution is best left to the courts, where citizens might seek and ultimately receive rewards for policy violations committed against them (

Galanter 1983;

Manning 1977).

2Concerned about over-burdened courts and a growing litigiousness within the public, some legal scholars began to call for changes in the justice system (

Sugarman 1985), but none so vocally, effectively, or penetrating to the public consciousness as those associated with the blossoming tort reform movement. This movement, largely spearheaded by conservative think tanks and interest groups in the 1980s and 1990s, developed effective public relations campaigns that painted private litigants as self-serving individuals prone to bringing “frivolous lawsuits” in pursuit of a big pay-day. As William Haltom and Michael McCann argued in their book,

Distorting the Law (2004), these campaigns effectively produced cultural memes about greedy attorneys and opportunistic plaintiffs that were picked up and reproduced by the media, tapping into American cultural valuations of individual responsibility and self-reliance that have driven public perceptions of litigation to that of a “crisis” in need of reform.

Studies of public attitudes toward litigation have, accordingly, been quite focused on measuring the effects of this tort reform movement. There is a general consensus that the public has effectively internalized the arguments of the tort reform movement (

Galanter 1983;

Haltom and McCann 2004;

Meinhold and Neubauer 2001), distorting public perceptions about the trustworthiness of lawyers (

Galanter 1998), the excessive nature of jury awards (

Hans 1993;

Saks 1998) and even, as trial lawyers have expressed to researchers, about court processes that can have major consequences for trial outcomes (

Daniels and Martin 2000). Indeed, public perceptions of litigation have been so shaped by this movement that tort reform pledges were major components of several presidential campaigns (both George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush produced campaign commercials featuring tort reform proposals).

Given the prevalence of the tort reform movement, most studies of public attitudes on private litigation focus on measuring the effects of this movement on opinion, as well as the subsequent effects of this opinion on support for the movement. A recent study by Neil

Malhotra (

2015), for instance, used survey experiments to explore the effects of exposure to “tort tales” on support for tort reform policy proposals aimed at reducing litigation. We are likewise interested in gauging the effect of this movement on attitudes toward litigation,

3 but with the additional intent of moving the conversation beyond the language and framing of the tort reform movement. Rather, we probe for public perceptions of litigation as a means of enforcing several substantive policy areas about which respondents assign varying degrees of regulatory importance. By presenting litigation neither through cultural memes of individual greed and monetary reward nor as something quite separate from policy and the regulatory process, we hope to better measure public attitudes toward litigation as an integral component of the American regulatory system.

In the analysis section to follow, we revisit these public attitudes toward the bureaucracy, litigation, and processes of how governance occurs in the U.S. Following important observations by

Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (

2002), we argue that people not only have opinions about the substance of policy, but also genuinely care about

how government does the things that it does. We suggest, in other words, that

process matters to the public and it is important to more fully engage with public attitudes on these processes. In doing so, we treat attitudes toward bureaucratic regulation and private litigation not simply in isolation, but in relation to actual policies and a larger framework that considers the different pathways by which policy might be enforced, revealing new findings on public attitudes toward this hybrid model of regulation in the U.S.

6. Introduction to Methodology

If the public cares about the process of governance—that is, how regulations are enforced—we should be able to observe those attitudes using survey data. To date, there have been few studies that compare how the public thinks about alternate means of regulatory enforcement. Studies of attitudes about federal agencies (

Pew Research Center 2015,

2018) focus on trust or confidence in the organization, and studies of attitudes on litigation (

Malhotra 2015) are developed mostly in relation to proposals for reform of the legal system. However, we know from the extant literature that citizens care not only about the outcomes of government but also about the process by which governing is carried out (

Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 2002;

Mansbridge 1983). While many citizens may not interact regularly with federal agencies, they do interact more frequently with street level bureaucrats enforcing policies in places such as courts, health agencies, airports, and police departments (

Lipsky 2010;

Michener 2018) and have opinions on those enforcement interactions. Given that most studies do not explore public valuations of administrative actions and private litigation as

processes through which public policy is enforced, there is ample opportunity to complicate these long-standing assumptions about public attitudes on these subjects.

To test whether there is variation in public support for these processes of policy enforcement, we developed and utilize a survey experiment on a module of the 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey (CCES).

4 The 2014 CCES is a nationally representative sample of American respondents, stratified by state and type of Congressional district, recruited from the larger online YouGov panel. The CCES was fielded in two waves—one wave prior to the 2014 Congressional elections in October and a post-election wave in November. The sample has 1000 respondents—54% of respondents are female, 28% have a high school degree, 28% of respondents identify as liberals, 33% as conservatives, 47% as Democrats, and 38% as Republicans. In the pre-election survey wave, respondents answered questions about their general views on regulation, litigation, and how much regulation there should be in five different policy areas: environmental pollution, food safety, mortgage lending, employment discrimination, and accommodations for the disabled (see

Appendix A for question wording).

In the post-election study, we developed an experiment in which respondents answered questions about their support for a particular process by which policy is enforced (whether through administrative action or private litigation) in the five specific policy areas asked about in the pre-election survey. The regulatory purview of these policy areas fall under different federal agencies and commissions that vary in the strength of their administrative powers and authority.

5 Likewise, each of these policies provides for a private right of action in the courts, meaning citizens have standing to bring complaints of violations of the policy before the courts.

6In addition, these policy issue areas differ in terms of their public salience and politicization, ranging from those that are both salient and polarized by party (e.g., environmental policy) to those that are less prominent and on which we expect minimal polarization (e.g., food safety). By randomizing what information respondents receive about policy enforcement within a representative survey, we can make inferences about how the public may think about the process of governance, not just policies themselves. Typically, the citizens most knowledgeable and opinionated on issues of regulation are those with a particular stake in the outcome of enforcement, and these citizens are not necessarily representative of the public as a whole. The treatments designed for this study consciously provide information only about different means of enforcement and do not specify any interest groups or political actors who may support or oppose these different types of enforcement mechanisms. In low information policy areas, citizens rely on heuristics such as the position of a party or interest group to form their opinions (

Berinsky 2007;

Lau and Redlawsk 2006;

Lupia 1994), but we are interested in whether citizens differ in their preferences across different processes of enforcement apart from partisan or ideological cues.

In our experimental module in the survey, for each policy area, we described a specific law and its goal. For example, in the area of employment discrimination, respondents read this preamble about the Civil Rights Act of 1964:

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employers from denying qualified employees raises, promotions, or comparable salary on the basis of race. When workplace discrimination occurs.

After the preamble, respondents were randomly assigned to see one of three paragraphs describing a mode of policy enforcement that takes place through: (1) agency powers (e.g., investigation, inspection, fines, etc.); (2) lawsuits brought by private actors; or (3) lawsuits brought by private actors where the harmed or aggrieved party has a financial incentive to sue for monetary compensation (a framing meant to tap into the effect of the tort reform movement on public attitudes toward litigation).

7 Examples for the treatments on employment discrimination policy are as follows:

This policy is enforced by a federal agency, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which conducts investigations and mediates settlements to require employers to grant minority employees a raise, promotion, or equal pay.

This policy is enforced by minority employees who sue their employers in court to require them to grant a raise, promotion, or equal pay.

This policy is enforced by minority employees who sue their employers in court to require them to grant a raise, promotion, or equal pay. Minority employees have a financial incentive to bring lawsuits because they may be able to collect a monetary compensation for themselves.

How much do you support or oppose the process by which this policy is enforced?

Strongly support, somewhat support, neither support nor oppose, somewhat oppose, strongly oppose

Each policy question was randomized separately, meaning individuals might have seen each permutation of treatment across the five different policy areas. After reading one of these three vignettes, respondents were asked about their level of support for how the policy is enforced on a five-point scale from strongly support to strongly oppose. By comparing support between the federal agency treatment (1) and the private litigation treatment (2), we can test whether respondents more strongly support bureaucratic action or private legal activity. By comparing the effects of the litigation treatment with no mention of financial incentives (2) to the litigation treatment with the mention of financial incentives (3), we can compare whether respondents are less supportive of private legal enforcement of public policies when individuals have a financial stake in the process. This comparison gave us leverage on the question of whether Americans’ views of litigation are driven by a sense that some people (unfairly) profit from lawsuits—a perspective well-publicized by the tort reform movement.

7. Results: Attitudes toward Regulation and Litigation (Pre-Election Wave)

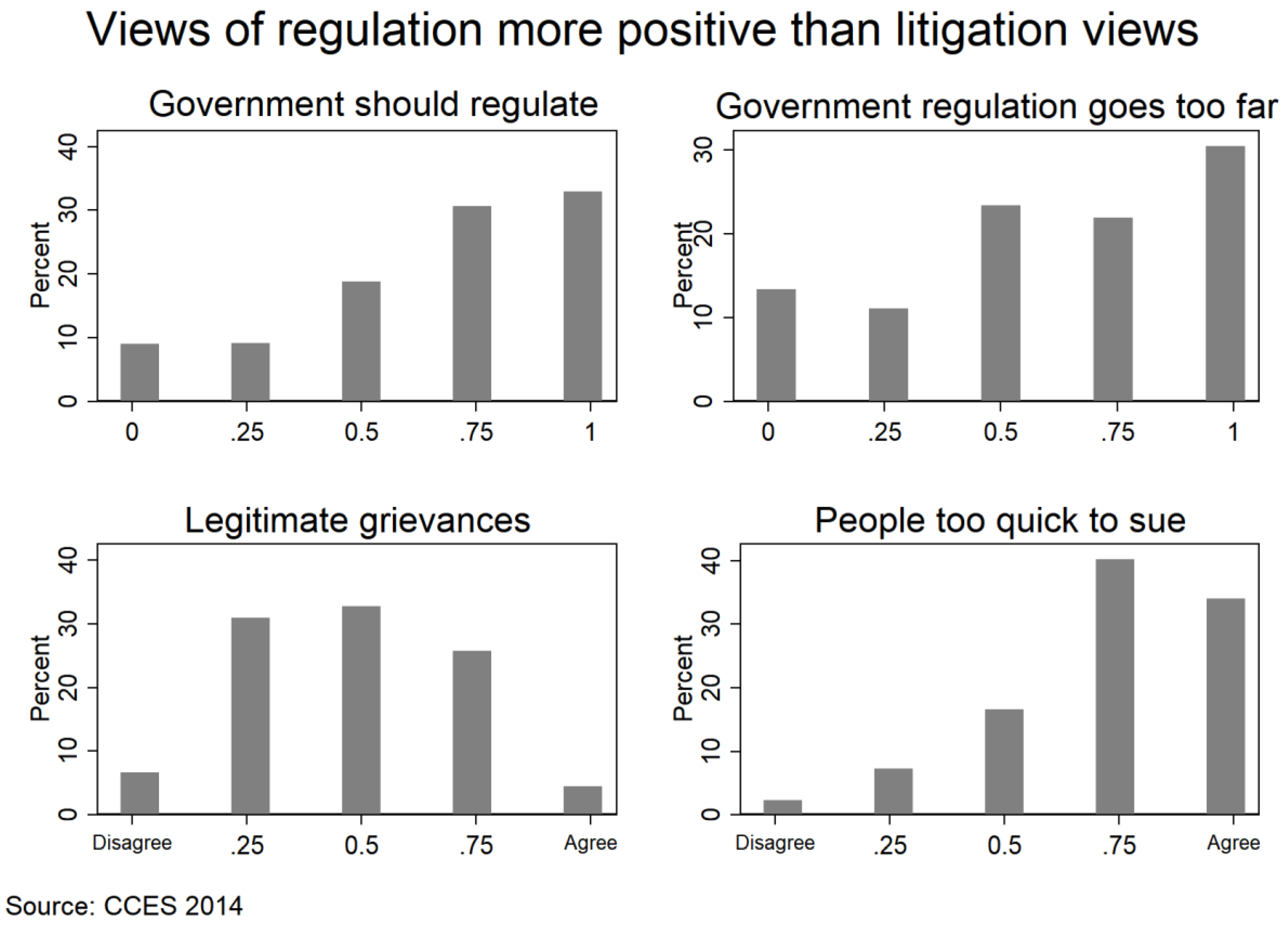

In the first wave of the survey, respondents in the study reported favorable views of regulation, in general, and across a variety of policy areas and regulation. The top half of

Figure 1 displays respondents’ baseline levels of support for government regulation from the pre-election survey wave. When asked whether the government should regulate major companies, industries, and institutions to be sure that they do not take advantage of the public, 64% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with that statement. While, overall, regulation was relatively popular, self-identified liberals were significantly more likely to support regulation, with 60% agreeing strongly with regulation compared to 13% of conservatives (X

2 = 243.62,

p < 0.01). However, a majority of respondents (55%) also strongly agreed with the statement that the government has gone too far in regulating business, tempering more general support for governmental regulation with a critical perspective on more activist approaches to this process. Again, there are significant differences by ideology of respondent, with 63% of conservative respondents strongly agreeing with the idea that regulation has gone too far compared to 7% of liberals. The Pearson’s correlation between these two items is −0.50.

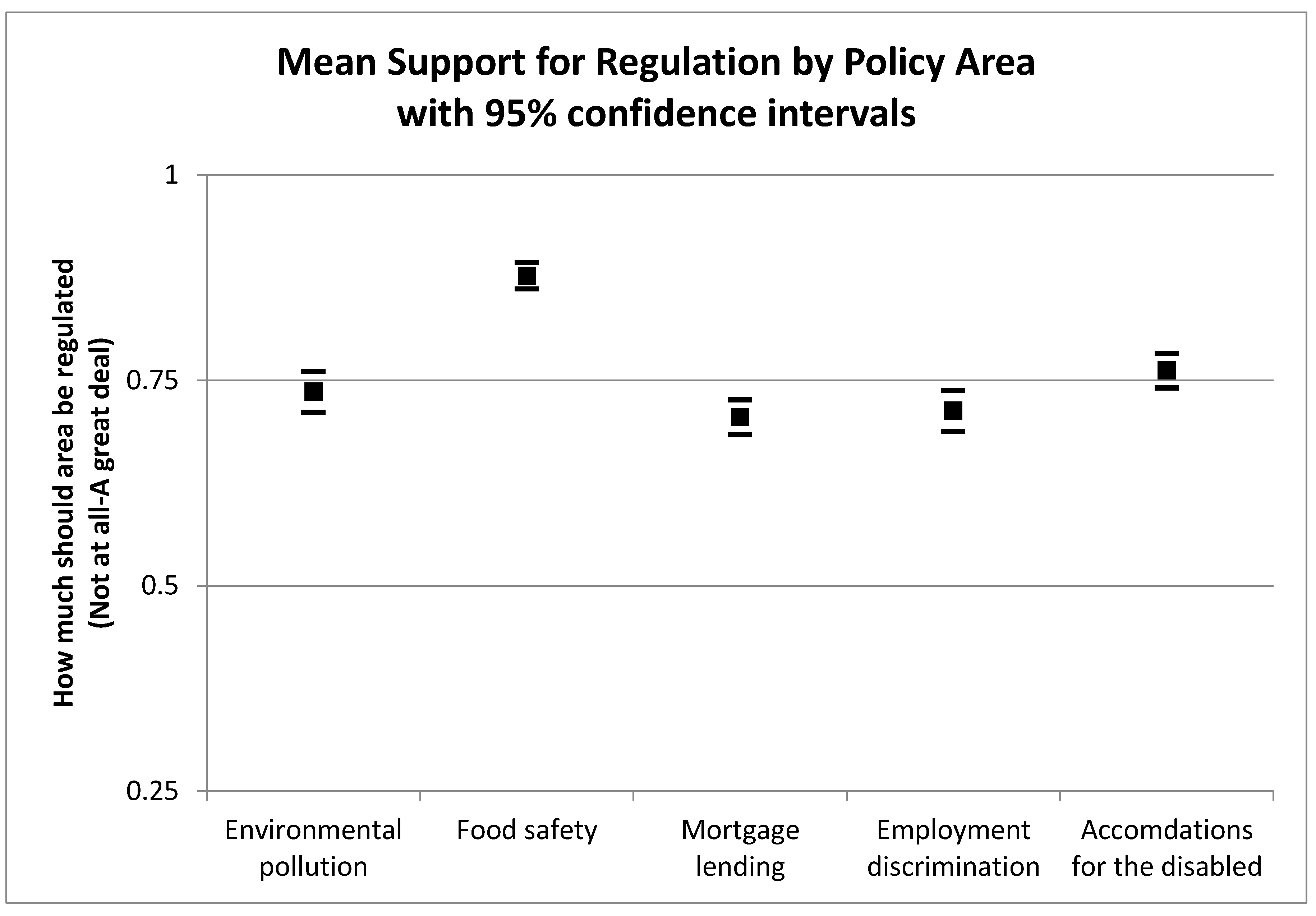

The pre-election survey also asked respondents how much regulation there should be in particular policy areas on a seven-point scale from “not at all” to “a great deal” (rescaled to vary between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating more support for regulation). The means and 95% confidence intervals of each question are displayed in

Figure 2. While a majority of respondents reported that the government has gone too far in regulating business in general,

Figure 2 shows that on our specific substantive policy areas of interest—accommodations for the disabled, environmental pollution, food safety, mortgage lending, and employment discrimination—the average level of support for regulation is on the pro-regulation side. Food safety is the policy area on which there is the strongest support for regulation, with 60% of respondents expressing support for the highest level of regulation on this scale and 90% supporting some level of regulation. Even with a more contentious policy area such as the financial regulation of mortgages,

8 26% of respondents preferred a great deal of regulation and 67% of respondents supported at least some amount of regulation.

9 This suggests that otherwise negative attitudes toward active governmental regulation may be seemingly tempered when considered in relation to actual public policy issues.

As the bottom half of

Figure 1 shows, however, respondents expressed consistently negative views about litigation. When asked whether most people who sue in court have legitimate grievances, only 4% of people strongly agreed with the statement, with another 26% reporting agreement. More than a third of respondents likewise strongly agreed with the idea that most people are “too quick to sue” rather than resolving their issues in another way, with only 2% of respondents disagreeing with the statement.

Taken together, results from these more general first wave questions on governmental regulation, litigation, and regulation of different policy areas reveal some of the patterns borne out by previous studies of attitudes on these phenomena. While respondents report general support for governmental regulation, they do believe these efforts sometimes go too far. However, attitudes regarding the appropriate scale of regulation come into fuller (and more complex) relief when these questions are asked about specific, substantive issue areas. Attitudes on litigation, however, are consistently negative, echoing the findings of many law and society studies that identify the strong distaste that Americans have for those who bring complaints in the legal system.

8. Results: Attitudes Captured by the Survey Experiment (Post-Election Wave)

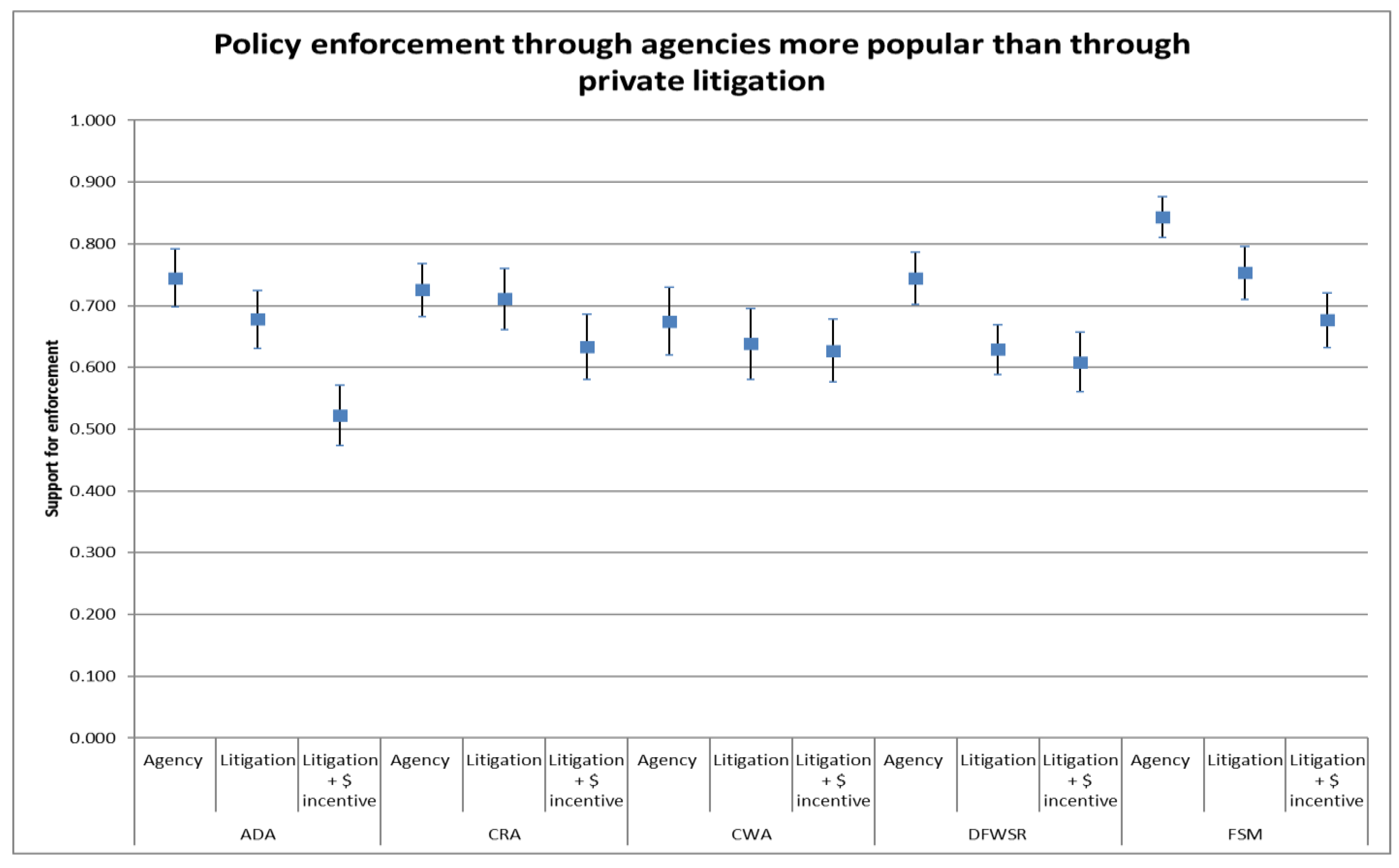

These more commonly embraced assumptions about public attitudes toward regulation and litigation are mitigated, however, when respondents are presented with experimental treatments designed to capture attitudes toward different pathways for enforcing policy on these five substantive issue areas.

Figure 3 displays the average level of support for how the policy is enforced according to each treatment group, as measured on a five-point scale from strongly oppose (0) to strongly support (1) and 95% confidence intervals around the mean. There are two main takeaways from

Figure 3. First, the enforcement of policy is more popular through federal agencies (1) than through litigation (2) or (3). While the rise of the Tea Party (

Skocpol and Williamson 2011) and declining trust in government (

Pew Research Center 2015) would suggest that Americans may respond negatively toward strong, bureaucratic action for enforcing policy, in three of the five policy areas we explore, respondents in the CCES are significantly more supportive of the federal agencies using powers such as investigations, fines, seizing products, and requiring business to act than of individuals suing to achieve the same regulatory ends. For policies on accommodating the disabled, regulating food safety, and regulating mortgage lending, respondents in the federal agency condition (Condition (1)) were significantly more supportive of the process of enforcement than their counterparts in Condition (2) (litigation, no mention of incentives). Overall support for enforcement across all conditions was high, but respondents who received the treatment about private lawsuits (Condition (2)) were less favorable toward the enforcement process of the ADA by 0.07 (or, 7% of the scale) (se = 0.03), the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform by 0.12 (se = 0.03), and the Food Safety Modernization Act by 0.09 (se = 0.03) than respondents who received the treatment outlining actions taken by federal agencies (Condition (1)).

The second primary takeaway from the results of the survey experiment is that respondents are less supportive of policy enforcement through private lawsuits with the “financial incentive” treatment (3) than those for which there is no mention of financial incentives (2). Respondents who were told that policy was enforced by victims bringing lawsuits on which they may be able to collect monetary compensation (3) were significantly less supportive of the process by which the ADA is enforced by 0.22 (se = 0.03) compared to the agency Condition (1), and this is significantly lower than even those in the litigation alone Condition (2) (F(1857) = 20.24,

p < 0.01). Even though respondents were as likely to support the enforcement of employment discrimination policy through lawsuits (2) as through agency investigations (1), when monetary compensation for employees was mentioned (3), respondents dropped their support by 0.09 (se = 0.03) (F(1855) = 4.4,

p < 0.05). An explanation for this finding might be that while citizens are perhaps familiar with the historical practice of using lawsuits to enforce civil rights protections (

Francis 2014;

Gonda 2015), and as such are not turned off by civil rights lawsuits per se, this indifference is diminished when presented with indications that litigants had financial incentives to sue. In the area of food safety, while respondents were less supportive of enforcement through litigation (2) compared to administrative actions taken by the FDA (2), their support drops even further when reading that citizens may have a financial incentive to sue and collect compensation (3). Compared to the agency condition, support for enforcement drops by 0.17 (se = 0.01) in Condition (3), a significantly larger effect than just reading about litigation on its own (2) (F(1852) = 6.03,

p < 0.01). The financial incentive condition appears to have the largest effect on issue areas that are more tied to rights claims rather than monetary claims. As such, it is possible that respondents interpret rights claims via lawsuits that can also benefit people financially as less legitimate or driven by greed rather than actual harm.

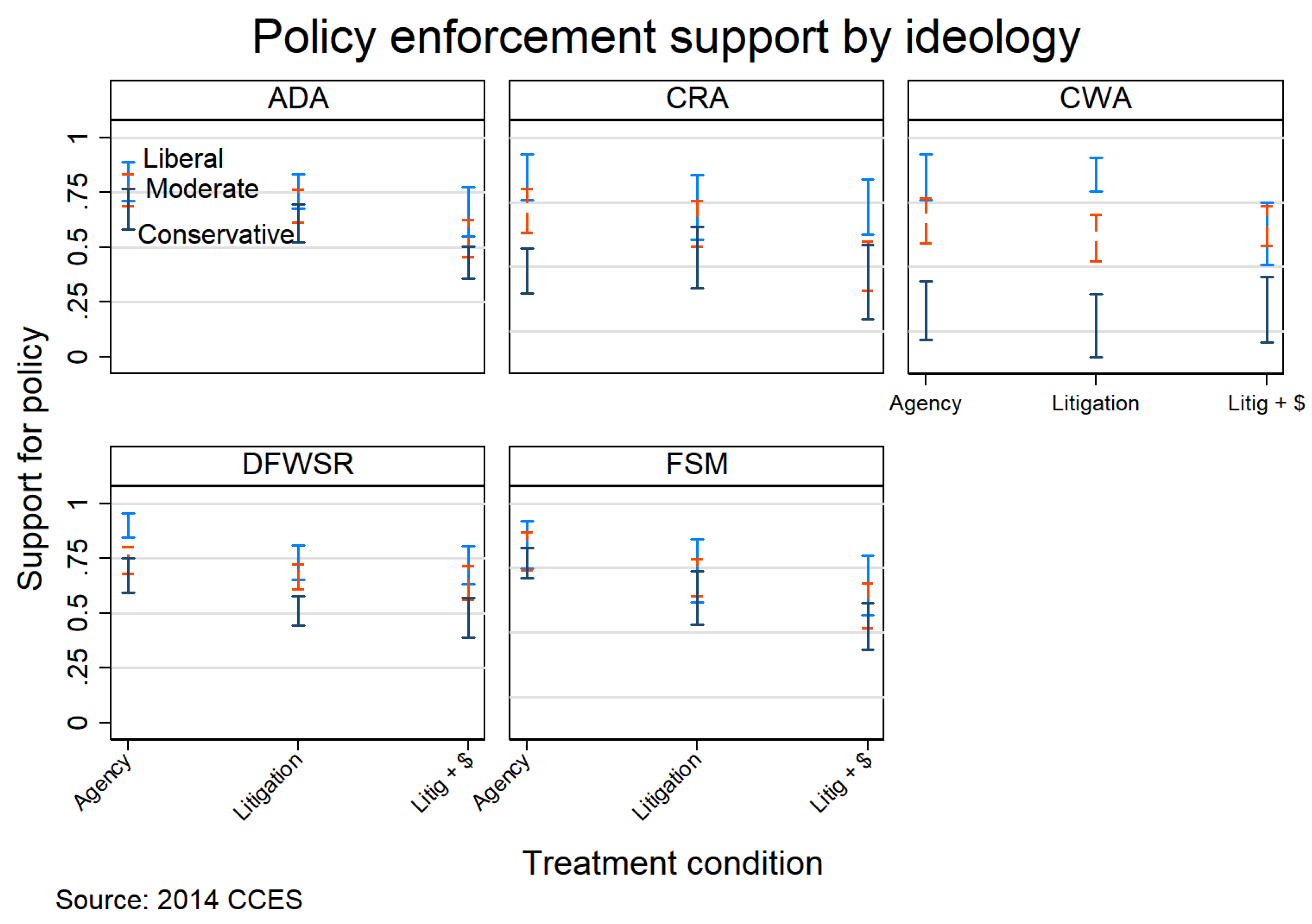

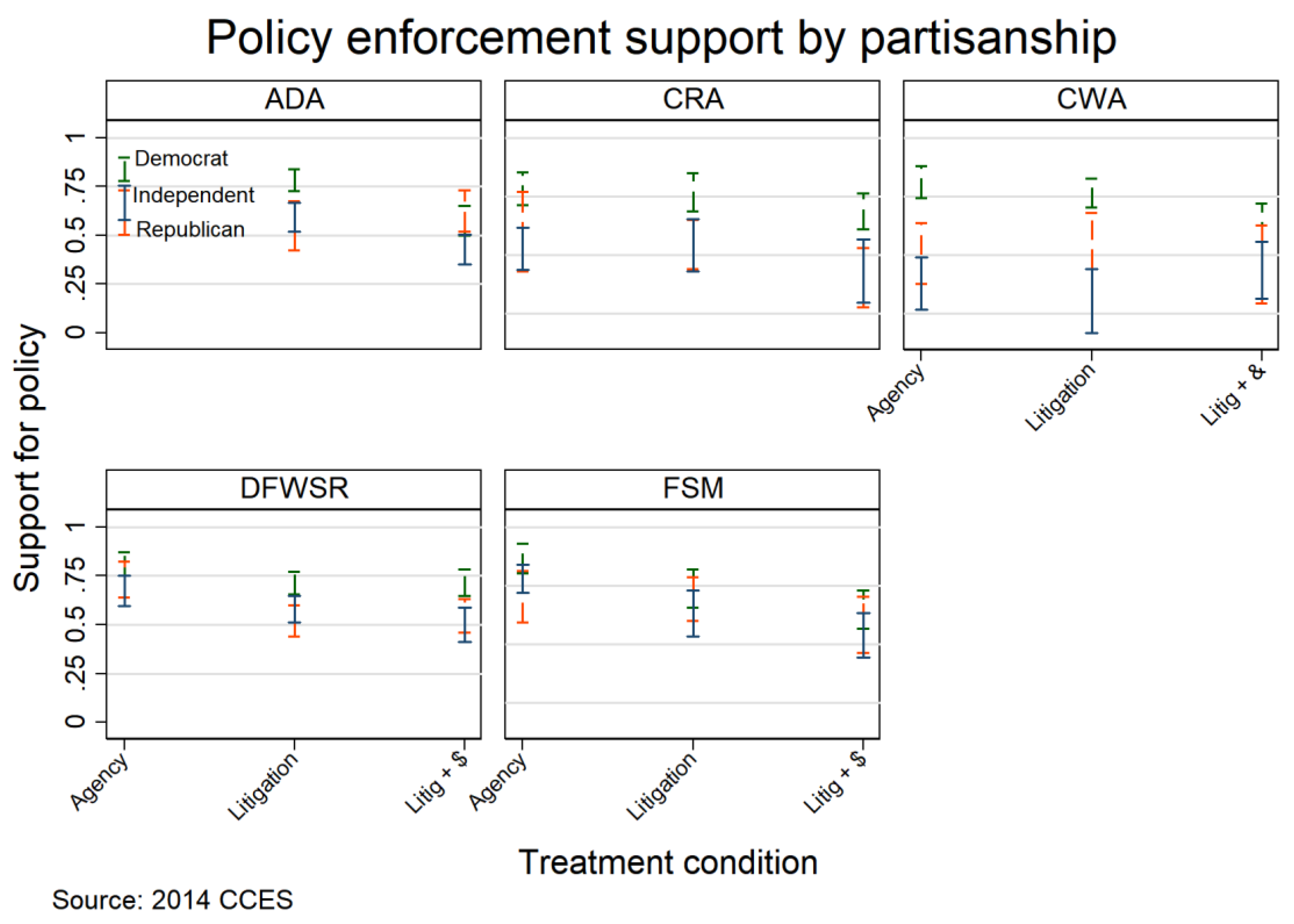

9. Effects by Partisanship and Ideology

In the pre-election survey, liberals and conservatives had different baseline levels of support for regulation and attitudes about litigation. Given that, it is possible that ideology and partisanship may moderate the impact of the treatments in the survey experiment. To explore that possibility,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 display respondents’ mean support (and 95% CI) for policy enforcement across the separate experimental treatments according to the partisanship and ideology of the respondent. Looking across the five different policy areas, one of the key findings that emerges is that the treatments work in similar ways across partisan and ideological differences. While liberals (Democrats), conservatives (Republicans), and moderates (Independents) have different overall levels of support for enforcement processes, on all five policy areas a consistent pattern emerges across the ideological and partisan positions of the respondents: that is, there is less support for litigation as a means of policy enforcement (2) than for agency action (1), and even less support for enforcement processes defined by lawsuits with financial incentives (3). For instance, after reading about litigation on the Americans with Disabilities Act (2), Democrats were less supportive of enforcement by 0.08 (se = 0.03,

p < 0.05) compared to when reading about enforcement actions taken by the Department of Justice (1). Democrats who read about litigation with financial benefits (3) were even less supportive of enforcement, lowering their evaluations of enforcement by 0.33 (se = 0.04,

p < 0.05). Among Republicans, the litigation treatment lowered support for enforcement by 0.11 (se = 0.05,

p < 0.05) and, while the litigation treatment with financial benefits depressed support by 0.27 (se = 0.05,

p < 0.05), across the two groups, these patterns are not statistically distinguishable.

10While common observations about the anti-“big government” attitudes of conservatives might suggest that these respondents would be more hostile to agency regulatory actions as compared to these other enforcement processes, and in relation to respondents at other points along the ideological scale, instead we find that the preferences orderings on these three treatments is largely consistent across ideological and partisan differences. This pattern is repeated across the rest of the policy areas, except for the enforcement of environmental pollution. When asked about enforcement of the Clean Water Act, conservative respondents were significantly less supportive of enforcement than liberals or moderates (i.e., the means are lower), and conservatives’ and moderates’ support for enforcement was not affected by the treatments. In contrast, liberals were significantly more supportive of enforcement through agency actions (1) than through private lawsuits (2), especially when there was mention of the lawsuit’s potential financial benefits (3). The treatments have a statistically larger effect on liberals than conservatives (X2 = 6.92, Pr > chi2 = 0.03) and moderates (X2 = 9.09, Pr > chi2 = 0.01).

Overall, the findings suggest that across policy areas that fall under the purview of different federal agencies, private litigation is less popular than agency action as a mechanism of enforcement across ideological and partisan boundaries. While conservative and liberal political elites often express contrasting preferences on the means by which policy should be enforced (with liberals typically less hostile to “big government,” administrative approaches to regulating social and economic behavior), in this study, liberal and conservative respondents are in relative agreement about their preference rankings on how (the means by which) policy is enforced.

10. Discussion and Conclusions

The operation of the hybrid administrative–legal American regulatory system provides a rich set of puzzles for students of policy enforcement. Questions regarding the degree to which one approach is preferred over the other, according to what criteria, and by whom provide a rich research agenda that has thus far been only partly addressed by studies of elite preferences on approaches to policy enforcement. This study sought to expand these inquiries beyond the debates occurring among political institutions and elites, to include the important and pivotal voice of the public—whose participation in and opinion of these bureaucratic and legal approaches to regulation is critical and thus far underexplored.

That this public perspective on approaches to policy enforcement in the U.S. has received scant attention is not surprising. Indeed, the great democratic narrative of American politics is often pitted against notions of policy regulation and enforcement—the idea being that the powerful public voice is naturally adverse to centralized governmental regulation of its behavior and practices. This is a disconnect that is likewise exacerbated by the discipline-reinforced divisions between more institutional, state-centered perspectives and more behavioral, public opinion-centered perspectives in the study of political science. It is on rare occasions that institutional and behavioral modes of inquiry and questioning dare tread on common ground, but much is lost in these divisions. This paper hopes to bridge these divides, addressing questions of regulation that have been thus far relegated to the study of institutions with the helpful tools and important perspectives offered by studies of public opinion. We aim, in other words, to bring the public back into the study of the state and the enforcement of its policies.

By better attending to this perspective, we could uncover findings on public attitudes toward bureaucratic and legal means of policy enforcement that challenge commonly-held assumptions. Perhaps most surprisingly, respondents in our survey experiments are quite supportive of policy enforcement conducted by bureaucratic agencies, on the whole. Even when accounting for potentially important intervening factors such as the ideology and partisanship of the respondent, we do not find evidence that conservatives—who one might expect to hold particularly hostile attitudes toward bureaucratic regulation—necessarily prefer private, legal mechanisms of policy enforcement over more administrative methods. Rather, contrary to larger ideological narratives on the size, scope, and proper role of the government that pervade our understandings of the operation of ideology in American politics, we do not find the common aversion to “big government” approaches to regulation typically assigned to conservative respondents even in a polarized moment when the executive branch was controlled by Democrats and there was strong political opposition to the Obama administration.

While we cannot determine from the results of this study what, exactly, is motivating public attitudes toward these different means of policy enforcement and whether these attitudes are more fixed or temporally contingent in nature, these considerations provide fruitful lines of inquiry for future studies—studies that would offer important lessons on how policymakers might approach public attitudes on these topics in different political eras. The lack of hostility to federal agencies reported by conservative respondents in the bounds of this study still leaves open the possibility that elite signals can change those attitudes. We may expect that, given the current presidential administration’s criticism of the work of federal agencies such as the FBI and CFPB, for instance, that conservatives may be more open to privatizing enforcement through litigation and/or especially opposed to the work of federal bureaucracies.

One area where attitudes appear to be consistent with elite framing and the malleability of public attitudes in our study is the distaste that ordinary citizens have for litigation when it is framed as driven by financial incentives (i.e., “greed”). The data indicate that without the financial framing, litigation is fairly popular, although still less popular as an enforcement tool than agency action. This suggests that the public may be less hostile to lawsuits if elites framed them without focusing on greed as an underlying motivation. Likewise, while our basic finding is that average citizens are surprisingly supportive of regulatory enforcement through federal agencies, this does not necessarily mean that average citizens will always support more active federal agencies. Our experimental design does not include elite cues, so it is possible that, with the addition of elites overtly arguing for one means of enforcement over the other, we would see more differentiation by partisan group and polarization in support for types of enforcement. In the current era in which federal agencies are directly maligned by the administration and are seen as poorly managed by the opposition party, we could potentially see different attitudes play out on how policy is enforced in the U.S.

With these lessons in mind, there is still much to study and say about the boundaries of public opinion on this important topic of how policy is to be enforced in a polity. By better bridging this divide between investigations of society and those of the state and its policies, we contribute to our understanding of the complexities of policy design, implementation strategies, and how the state and society may shape one another through the processes of regulation.