Abstract

Environmental crime has been increasingly recognised as transnational organised crime, but efforts to build a coherent and effective international response are still in development and under threat from shifts in the funding landscape. This mixed methods study addresses the role of one significant group of actors in environmental crime enforcement, which are non-governmental organisations (NGOs) who gather intelligence that can be shared with law enforcement and regulatory agencies. The study compares their intelligence practices to findings from traditional intelligence sectors, with a focus upon criminal justice and policing. The research generated quantitative and qualitative data from NGO practitioners, which is integrated to discern three overarching themes inherent in these NGOs’ intelligence practices: the implementation of formal intelligence practices is still underway in the sector; there remains a need to improve cooperation to break down silos between agencies and NGOs, which requires an improvement in trust between these entities; the operating environment provides both opportunities and challenges to the abilities of the NGOs to deliver impact. The study concludes by positing that the characteristics of NGOs mean that this situation constitutes ‘green intelligence’, contextualising intelligence theory and highlighting areas in which agencies can further combat environmental crime.

1. Introduction

Recent years have seen increasing recognition that environmental crime exacerbates not only biodiversity loss but also climate change, causing economic instability and threats to human health and security (UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) n.d., paras. 1–2). Environmental crime involves offences associated with wildlife, forests, fisheries, mining, precious metals, waste, and pollution, and has been described as the fourth biggest crime type globally after drug trafficking, counterfeit crime, and human trafficking (Nellemann et al. 2016, p. 7). However, efforts to combat it are limited by weak governance, corruption, and lower political commitment and coordination (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and The World Bank 2019, pp. 8–9).

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are not-for-profit organisations which often have a charitable status (Vakil 1997, pp. 2058–59; Internal Revenue Service n.d.). In common with NGOs in other sectors such as human trafficking (Ahmed and Seshu 2012, para. 5; Shih 2016), NGOs that work on environmental issues can derive their legitimacy from ideological positions, including those that reflect the moral case for protecting animal rights, animal welfare, and environmental justice, to foster social change and the holistic protection of the planet (Nurse 2013, pp. 307, 311–12; White 2011, p. 143; World Wildlife Fund n.d., paras. 1–2). However, wildlife conservation models linked to NGOs in protected areas within developing countries have drawn criticism on the grounds that racism and (neo)colonialism deprive indigenous people of rights in favour of creating space for declining animal populations to recover (Kashwan et al. 2021; Lee 2023).

The literature demonstrates that some NGOs focused upon environmental crime work on fisheries, forests, mining, waste and pollution, but are more likely to work on wildlife crime, which is at least partially explained by the comparative ease of storytelling and funding opportunities associated with championing the protection of charismatic animal species (Colléony et al. 2017; Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC) 2014, p. 30; Friend 2023, paras. 23, 28, 78–79). As a result, such NGOs can focus their efforts upon countries with high levels of biodiversity, which might also have weak legal frameworks and high levels of political corruption (Barber and Bowie 2008, p. 749; Smith et al. 2003).

Important contributions from green criminology have furthered understanding of NGO activities (White 2011; Nurse 2011, 2012, 2013). Nurse (2013) proposed a taxonomy of campaigning, advocacy or law enforcement NGOs working on wildlife crime, and indeed, some NGOs support law enforcement interventions through the gathering and provision of criminal intelligence to governmental agencies (Nurse 2011, p. 39; 2012, para. 19; Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC) 2014, pp. 29–30; Haysom and Shaw 2022, p. 27). To date, however, academic research has not explored their intelligence practices specifically. The study therefore addressed the research question “How closely do NGO intelligence practices resemble or diverge from that which has previously been observed in policing and security literature, and why?”.

1.1. Background and Context

1.1.1. Environmental Crime, Environmental Harm and Organised Crime

The term ‘environmental crime’ is subject to definitional debates but can be understood as referring to illegal activity that harms the environment (Wentworth and Rabaiotti 2017, p. 1). Terms such as ‘green crime’, and ‘eco-crime’ are also used, due to the diversity of academic disciplines and perspectives (Marshall and Kangaspunta 2009, p. 4; Walters 2010, pp. 179–80). Scholarship considers not only criminally prosecuted activities but also regulatory violations to examine broader environmental harms such as pollution (Gibbs et al. 2010, p. 126; Gibbs and Boratto 2017, paras. 2–3). In a similar manner, law enforcement definitions of environmental crime can incorporate both breaches of legislation, and activities which cause “significant” harm and risk (European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol n.d., para. 1)).

Criminal justice literature has not yet achieved consensus on what defines ‘organised crime’ (Kuloglu 2016, p. 116; Brewster et al. 2021, para. 8) and some of the broadest definitions include co-offending by two or more people (Paoli and Vander Beken 2014, pp. 14, 18). Such definitional debates may be partly explained as the result of differences in perspectives between ‘who’ is committing crime and ‘what’ crime is being committed, or the power dynamics at play (Paoli and Vander Beken 2014, p. 14; von Lampe 2008, para. 3). This debate is further compounded when it is considered that serious crime does not have to be inherently organised (Thompson 2019, p. 103). European policy has conceptually combined ‘organised’ with ‘serious’ crime (Paoli and Vander Beken 2014, p. 25), which is reflected in the United Nations’ (UN) definition of organised crime groups (UNODC 2004, p. 5); this situation supports the proposition that, despite debate, the label of ‘organised crime’ allows enough focus to enact legislative and institutional change which then helps to assign resources (Paoli and Vander Beken 2014, p. 26).

The international policy agenda has increasingly recognised the threat of environmental crime and the need for improved responses (Elliott 2012, pp. 87–88; Financial Action Task Force (FATF) 2003, p. 15). Associated organised crime narratives can be interpreted as partially driven by efforts to raise awareness (Mackay et al. 2020, Conclusion). Environmental crime has been defined as “including, but not limited to serious crimes and transnational organized (sic) crime” (Nellemann et al. 2016, p. 17), and by 2019, this view had become broadly accepted within the international community, due in part to high levels of poaching of some animal species and increasing recognition of the intersections between environmental crime, conflict and security (Elliott 2012, pp. 87–88; Haysom and Shaw 2022, p. 16). In academic research, however, the prevalence of organised crime in environmental crime remains debated, and academics have warned that unnuanced narratives perpetuate a securitised conception of environmental crime which hampers efforts to embed approaches that are not dependent upon law enforcement (Mackay et al. 2020; Massé et al. 2020).

To some extent, conflicting discourses appear to be symptomatic of insufficient definitions, which might be better nuanced when ‘Organised Crime’, written as capitalised, is used to refer to crime organisations, and ‘organised crime’, in lowercase, to criminal activities which require an extent of organisation (Hagan 2006, p. 134). Furthermore, the term “disorganised crime” (Reuter 1983; Kleemans 2013, p. 616) may be a more useful term to refer to marginal and less structured enterprises and has already been applied to wildlife crime networks (Wyatt et al. 2020, pp. 356–57). It can be concluded that there remain opportunities for environmental crime scholarship to refine understanding through enhanced integration of insights from the existing criminal justice literature base; meanwhile, this study sought to explore practitioners’ perceptions about the prevalence of organised crime within environmental crime.

1.1.2. Environmental Crime NGOs—Extending Intelligence and Enforcement Beyond Governments

Some NGOs have extended their moral responsibility to undertake law enforcement activities, with the result that environmental and animal welfare perspectives are now entering traditional criminal justice paradigms (Nurse 2012, para. 7). As entities which operate in spaces where formal enforcement processes are absent or under resourced, this subset of NGOs can conduct and support investigations, gather and analyse intelligence, provide evidence at court, and in some cases have a prosecutorial mandate (Nurse 2013, pp. 306, 310–12; Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC) 2014, pp. 29–30; Rothe and Shim 2018; Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Sharman 2022).

In order to achieve these aims, some environmental crime NGOs gather intelligence, yet their activities have rarely been studied in depth—even when information and intelligence comprise a sizeable proportion of overall activities (Cadman et al. 2020, Table 1, Figures 5 and 6). Likewise in military intelligence studies, there is a paucity of research about NGO activities in general, and that which exists does not address how they actively gather and analyse intelligence (DemMars 2001, p. 196). Only a limited number of studies have addressed the implications around such outsourcing of policing (Nurse 2013) and national security functions, and have questioned how governments’ reliance upon external entities such as NGOs might shape the setting of intelligence priorities—including what happens to accountability in such instances (Martin and Wilson 2008, pp. 771–72; Petersen and Tjalve 2018, pp. 22, 30).

In the United Kingdom (UK), intelligence-led policing (ILP) developed from recognition of the threats posed by serious and organised crime and the limitations posed by reactive policing, along with the requirement to use resources more efficiently (John and Maguire 2007, pp. 201–3). Following several police inquiries which produced recommendations around the implementation of standards and processes to manage intelligence, along with the Police Reform Act 2002 (James 2013, pp. 69–72), the National Intelligence Model (NIM) was adopted in 2000 as a standardised intelligence-led business model and was accompanied by minimum standards which police forces in England and Wales were required to implement (National Centre for Policing Excellence (NCPE) 2005, p. 11; John and Maguire 2007, pp. 200–1, 220). ILP’s use of “sophisticated sources of intelligence” including “participating informants” and “the matching of databases from different agencies” however raised new risks and human rights debates (Maguire 2000, p. 333) where intrusion is more warrantable when targeted towards organised criminals (James 2017, Abstract).

While it is therefore clear intelligence does indeed now extend beyond the functions of government (Marrin 2018, p. 483), the literature does not show the extent to which NGOs have implemented formal intelligence frameworks such as the NIM.

1.1.3. Implications for Intelligence Theory

Recent years have seen reinvigorated academic efforts to broaden intelligence theory, including how it relates to non-state actors (Marrin 2018, p. 482). Often with a national security focus, this research has mainly been concerned with the growth of the private intelligence sector and the attendant opportunities and risks for states (Matey 2013; Delaforce 2013; Treverton 2018, p. 476). Far less attention has been paid to NGOs, although the need for further comparative research has been recognised (Gill 2010, p. 50; Gill and Phythian 2012, p. 57); while recent work by Pietilä et al. (2024) has illuminated the shift in power relations and intelligence ownership as a result of intelligence activities by citizens and NGOs (CITINT) including in the Finnish context.

One valuable contribution was offered by Gentry (2016), who compared the intelligence activities of non-state actors—including NGOs focused upon humanitarian issues and political advocacy—with state intelligence practices, to offer the foundations for a theory of intelligence for non-state actors. Ultimately, Gentry (2016) declined to formulate his findings into a single theory, and instead advocated that intelligence studies would continue to benefit from a variety of perspectives to avoid the “paradigm wars” of other disciplines (p. 488). There also remain opportunities to further examine the functional and structural dimensions of NGO intelligence, and explain how these fit together (Walsh 2011, p. 91; 2015, p. 125).

In 2011, Walsh offered an ‘effective intelligence framework’, which he considered to represent common elements of different intelligence frameworks regardless of context, and the means to examine intelligence practices more holistically to highlight areas for future research and theory building (pp. 92, 148–49). The framework comprises core intelligence processes: tasking and coordination; collection; analysis; production, and evaluation; within which security sits at the heart; then five enabling activities: research; legislation; human resources; information communication technology, and governance with independent oversight (Walsh 2011, p. 148; 2015, pp. 134–36). Given its inclusive scope, this study therefore applied the framework as its theoretical lens, not to assess effectiveness of NGO intelligence frameworks per se but as a structure to conduct research and develop insights to inform the research question. Furthermore, the study sought to address Walsh’s own question, as to how suitable and generalisable the framework might be to other intelligence contexts (Walsh 2015, p. 138).

2. Methods

2.1. Overview and Rationale for the Mixed Methods Approach

Research took place during 2023 as part of a Master’s degree. The study was a mixed methods study incorporating both quantitative and qualitative strands. In criminal justice research, qualitative and mixed methods approaches have been under-applied, but there has been increased recognition that, when used appropriately, mixed methods can enrich findings (Trahan and Stewart 2013, p. 62; Wilkes et al. 2022, pp. 528–29). In this manner, the mixed methods approach can be a pragmatic means towards resolving tensions between quantitative and qualitative research philosophies (Johnson et al. 2007, pp. 113, 125). Furthermore, the pragmatic position can be suited to examination of phenomena in organisations including NGOs (Kelly and Cordeiro 2020, paras. 2, 4).

As research of intelligence practices can be limited by organisational secrecy (van Buuren 2014, p. 90) the study followed a QUAN -> QUAL sequential design to implement the quantitative phase strand first on the basis that anonymous surveys can encourage engagement (Nie et al. 2021, Section Discussion). The quantitative phase was used to develop the qualitative construct towards an instrument that better represents human experience (Wilkes et al. 2022, p. 530), because the quantitative survey generated hypotheses which refined the qualitative interview questions (Hanson et al. 2005, p. 227; Creswell and Plano Clark 2011, Figure 3.6). In combination, results from the mixed methods design generated understanding of the topic (Aarons et al. 2012, pp. 68, 76; Clark and Ivankova 2017).

2.2. Participants

The survey was sent to 39 organisations, and 11 responses were received (28% response rate). All survey respondents (n = 11, 100%) responded that they worked for an NGO, therefore the methodology was highly successful in identifying the relevant sample. The qualitative semi-structured interviews (SSIs) engaged five NGO practitioners.

2.3. Materials and Sampling Procedure

In line with much criminal justice research (Wilkes et al. 2022, p. 540) the study used a survey instrument to obtain quantitative data. The survey was internet-based and anonymous (Kennedy 2008) and followed a purposive sampling strategy (Barratt et al. 2015, para. 7; Palinkas et al. 2015) as now described.

A semi-systematic academic literature review was undertaken, which is deemed suitable for topics that have been conceptualised across different disciplines (Wong et al. 2013, para. 2; Snyder 2019, p. 335), and the results were restricted to publications from the year 2000 onwards given the increasing academic and political attention afforded to environmental crime since that time (Elliott 2012, pp. 87–88). As the literature base is emerging and located in several places (Creswell and Tashakkori 2007, p. 109), the researcher supplemented the previous findings with a review of grey literature and directories about environmental crime. This had two aims: firstly, to identify materials which enabled understanding of the kinds of intelligence activities NGOs are involved in, and secondly, to identify the NGOs which gather, develop and share intelligence to support law enforcement and regulatory agencies to inform the survey sample.

To support this second aim, the names of 173 potential NGOs were identified from the literature. The researcher then referred to each website domain (n = 173) to verify which were NGOs through review of the NGOs’ own declarations and donation pages, and where necessary, with reference to regulatory charity and non-profit databases (e.g., Charity Commission for England and Wales n.d.; Internal Revenue Service n.d.). Due to sensitivities about intelligence activities (Walsh 2011, p. 132; Pili 2019, p. 165), the subsequent strategy to obtain the survey sample sought to identify only NGOs which self-declared that they undertook intelligence activities. The researcher therefore deployed advanced searches using the Google search engine which ensured that the relevant statements appeared within the content of each individual NGO’s organisational website. This meant that named NGOs whose intelligence work was referenced in third party publications, but not mentioned in their own materials, were excluded according to the criteria.

Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Palinkas et al. 2015, para. 8), which identified 39 NGOs in countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, Oceana and the Americas, working on environmental crime to include illegal mining and crimes related to fishing, forests, wildlife and waste.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the survey sample (n = 39 NGOs).

The survey was sent to each organisation using the contact details provided in published materials: organisational ‘info’ emails were primarily chosen in order for the survey invitations to be received and distributed within organisations, but some organisations instead only provided named email addresses, and online forms were used in the absence of email contact details. The survey invitation contained a request for distribution to participants who would fulfil the purposive sampling criteria of being (a) employees of the organisation, having (b) a role in intelligence, or possessing (c) knowledge of intelligence or enforcement practices and fulfilling a role such as law enforcement liaison, technical advice, or senior management. With the exception of the consent question, all survey questions were optional (University of Portsmouth 2020); questions formats included multiple choice (single or multiple answer), Likert Scales (Joshi et al. 2015, pp. 397–98; Heo et al. 2022, p. 374) and free-text fields to capture qualitative responses, which were included in order to enhance the instrument and validate the construct (Onwuegbuzie et al. 2010, p. 65). Given the relatively small sample, the results were analysed using Microsoft Excel rather than dedicated statistical analysis software and results are presented in the Figures.

In order to progress to the next phase of the SSIs, the researcher revisited the original survey sample of 39 NGOs to apply a criterion sampling approach (Moser and Korstjens 2018, p. 10) to identify NGOs whose materials included organised crime in the context of environmental crime (n = 15) to include illegal mining and crimes related to fishing, forests, wildlife and waste. From this sample, NGOs which fit the new criteria but had responded to the original survey email to state that they did not assist with student projects were excluded (n = 2) and one further NGO was excluded due to limited historical mentions of organised crime. Invitations to the SSIs were sent to the remaining NGOs (n = 12) by email to organisational addresses and individuals using the contact details provided in the published materials used to inform the sample. Attached to each email was a comprehensive participant information sheet which outlined the research, the process to assign a gatekeeper to act as an intermediary (Clark et al. 2021, p. 131) and ethics materials.

During the interviews, sampling maintained the purposive approach in conjunction with snowball sampling and theoretical sampling; as the initial analysis of the survey results had been completed by this point, the researcher was able to highlight areas where potential candidates might be able to contribute to the development of theory (Vogt et al. 2012, pp. 128–29; Moser and Korstjens 2018, p. 11; Naderifar et al. 2017, para. 6).

The five interviewees were dispersed internationally and the interviews took place using audio and video-conferencing platforms. Interviews lasted 37 to 90 min in length and began with a summary of the research to check the participant’s understanding and obtain verbal consent to supplement the written consent which had already been obtained. Audio files were transcribed and identifiers removed from the transcripts, and the anonymised transcripts were provided to participants to verify that they agreed with the content, after which each transcript file, and therefore all content, was given a non-sequential alphanumeric identifier named P1 through to P5 inclusive, and the content was analysed using NVivo software as described in the next sub-section.

The qualitative research phase followed four steps (King 2004a, p. 14). First, the researcher defined the research question: “how closely do NGO intelligence practices resemble or diverge from that which has previously been observed in policing and security literature, and why?”. Second the researcher created the interview structure guide which adhered to the theoretical framework of Walsh (2011), and within which individual questions were refined through analysis of the survey results (Kelle 2006, p. 308). In this manner, the initial process was both theory-driven and deductive (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 82; Clarke and Braun 2014, para. 3). Third, the researcher recruited the participants, and then fourth, conducted the interviews (King 2004a, p. 14). The semi-structured format allowed for the opportunity to probe for more information (Ruslin et al. 2022, pp. 24–26), however throughout, and as with the survey instrument, ethical considerations prescribed the nature and depth of the questions.

2.4. Data Analysis—Semi-Structured Interviews

The anonymised SSI transcripts were analysed using NVivo software in a process of qualitative thematic analysis (TA), which was chosen for its coherence with the research goals and the data format (Kiger and Varpio 2020, para. 7), and which followed six distinct phases proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 87):

Phase 1. Data familiarisation: This phase started during the interviews, which were recorded and transcribed, and supported by notes which the researcher took during the interviews. The researcher checked each transcript while listening to the audio recordings and read each interview transcript in the entirety several times, while making initial notes to aid memory in the later process of generating themes (Braun and Clarke 2006, pp. 87–88; 2012).

Phase 2. Generating initial codes: The researcher used NVivo to review the data equally and initially code short phrases in the data, which, as a data-driven exercise, took an inductive approach (Braun and Clarke 2006, pp. 88–89). To avoid repetition, the codes were collated separately (Nunan et al. 2020, p. 517), which generated documentation to support the principle of trustworthiness (Nowell et al. 2017, paras. 20–23, 26–31). Table 2 shows an example of an initial code which was generated from the data.

Table 2.

Data extract with code applied in TA Phase 2. From NVivo analysis (2023).

Phase 3. Searching for themes: The researcher then searched for themes, which were determined through reflexivity, to judge coherence with the research question and whether they represented “patterned response(s) or meaning” within the data (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 82). In this manner, the process was both inductive and deductive, but all themes were treated as ‘candidate themes’ and retained in order to assess significance and undertake the next phase (Braun and Clarke 2006, pp. 89–91). The use of diagrams within NVivo helped to visualise connections between the data (Nowell et al. 2017, para. 42).

Phase 4. Reviewing themes: The candidate themes were then reviewed for distinctiveness and coherence both overall and across the coded data, to result in first and second order codes (Braun and Clarke 2006, pp. 91–92; Nowell et al. 2017, para. 45), after which adjustments were undertaken to assure validity (Labra et al. 2019, sct. 5.4). For example, two first-order codes of ‘Formal sharing and ‘Informal sharing’ were reviewed and merged to become one first-order code of ‘Formality of sharing’ which was then linked to the second-order code of ‘Interactions’ which was then linked to the broad theme of ‘NGO intelligence sharing—building trust for collaboration’.

Phase 5. Defining and naming themes: The codes from the fourth and fifth TA phases were linked in a pathway that produced the final three themes (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 92). The researcher then reviewed the component data to ensure that all sections relevant to the research question had been accounted for, and to mitigate the risk that anecdotes had been transformed into themes (King 2004b, pp. 260–66; Kiger and Varpio 2020, para. 27). After finalising the themes, the researcher then provided verbatim quotations to those participants who had requested a review for their sign-off.

The three themes were as follows:

- Developing intelligence as NGOs—a patchwork of practices without standardisation?

- NGO intelligence sharing—building trust for collaboration

- Delivering meaningful change—recognising and reforming the operating context

Phase 6. Producing the report: Section 3 below integrates the survey results with the SSI results within the three themes to illuminate and analyse the research question (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 93). The coherence of the argument can also be considered as indicative of the trustworthiness of the TA process (Nowell et al. 2017, para. 57).

2.5. Ethical Approval

The researcher followed the UK Concordat to Support Research Integrity (Universities UK 2019). Prior to undertaking any research, the researcher drafted a comprehensive ethics application which was reviewed by the research supervisor, following which the application was submitted to the University of Portsmouth Ethics Committee during March 2023. The application received a favourable ethical opinion under ethics approval reference number 1132, after which primary research commenced.

2.6. Reflexivity

The researcher had prior professional experience of working in the environmental crime sector, which was declared in the SSI materials, with a foundation in public sector intelligence analysis. At the time of the research, the researcher was an independent freelancer working on a range of environmental and international trade topics. The researcher might therefore be considered a “partial insider” with some “degree of distance or detachment” (Chavez 2008, p. 475).

This status may have some potential benefits, such as rapport (Humphrey 2013, pp. 574, 579), but also accentuated the pre-existing need to mitigate the risk of bias (Smith and Nobel 2014). In order to promote reflexivity and research validity, the researcher maintained a dated decision diary to produce an audit trail (Mauthner and Doucet 2003; Greene 2014, pp. 8–10). In addition, the researcher referred to checklists, practice and polices, both in preparation of the ethics application and throughout the research (Schreier et al. 2006; UK Research Integrity Office n.d.a, n.d.b).

2.7. Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First due to the primary language of the researcher, the search strategy and sampling favoured English language materials, which potentially excluded an unknown number of NGOs from recruitment. Second, while the quantitative survey was able to identify 39 NGOs, the survey received 11 responses (28%), which limited the opportunities for analysis and posed challenges in relation to the generalisability of findings. Third, the researcher was informed that some organisations’ email filtering systems had routed the researcher’s emails into spam folders which may have affected the success of reaching an unknown proportion of the sample. Fourth, several gatekeepers reported that potential candidates were unavailable due to travel. Lastly, the researcher was aiming for at least six SSIs but due to the above availability issues, five were undertaken.

It also should be noted that the researcher drew upon research about policing practice, which as available in English is weighted towards Western European/North American/Australasian contexts. The researcher compared that with NGOs’ practices including in other regions, so the study could be considered ethnocentric.

3. Findings and Discussion

3.1. Developing Intelligence as NGOs—A Patchwork of Practices Without Standardisation?

The first theme surveys the ways that intelligence practices have evolved differently across NGOs in comparison to formal structures observed in the police and security sectors, and in particular highlights the issue of accountability in NGO operations.

3.1.1. Mission and Role

Interview participants clearly communicated the role of NGOs in combating environmental crime as compared to police and provided perspectives about the contributions of NGOs to the sector.

I think at the outset, we are very clear on who we are and who we’re not. We’re an NGO, we’re not a police service. We don’t pretend to want to be a police service, we can learn some lessons from police organisations, but we’re absolutely clear what we are and what we’re not.(P5)

Two interviewees explained that some NGOs might help to push for change, and call for laws to be strengthened (P2 and P5), which reflects the position of Gentry (2016, p. 470). One interviewee described how NGOs can help to convene government actors in the hope of stimulating greater cooperation, along with offering training support and subject matter expertise (P1), and with another interviewee, felt that NGOs’ global or local perspectives provide helpful knowledge to governments (P1 and P5). One further interviewee reported that law enforcement agencies had told them that they value the role of NGOs in helping to combat environmental crime (P4).

3.1.2. Defining Intelligence

In spite of definitional debates throughout the wider intelligence literature, there does exist consensus that intelligence is different to, and more than, information (Matey 2013, pp. 279–80), and provides “useful knowledge for a decisionmaker” (Pili 2019, p. 183).

Interviewee P2 suggested that the term ‘intelligence’ can carry several implications. The survey asked participants to provide their own definition of intelligence in free text (survey question number 6, n = 8). Notably, all definitions were different, but some commonalities were nonetheless apparent: all responses referred to ‘information’, and the majority of responses (n = 6) described intelligence as information which has undergone a process of assessment (Peterson 2005, p. 3). However, only half of these responses linked the assessment process to outcomes (n = 3). One further response defined intelligence in terms of secrecy, which has been recognised to be an important element of intelligence (Warner 2002)—although the proliferation of open-source intelligence (OSINT) may challenge that paradigm (Miller 2018), while one response defined intelligence in terms of how information is gathered. One striking feature was that respondents who stated that they worked to the NIM (n = 3) all referred to information as being subject to a process of assessment, but none replicated the NIM definition of intelligence (National Centre for Policing Excellence (NCPE) 2005, p. 196). It would however appear unreasonable to recommend that NGOs agree upon one definition, when the same issue has been debated within the wider intelligence literature (Pili 2019).

3.1.3. Sources and Methods

Conservation practitioners and military personnel have highlighted the utility of human intelligence (HUMINT) to, respectively, support anti-poaching patrols (Linkie et al. 2015) and to inform NGOs combatting sex trafficking (Howell et al. 2019), while the wider literature suggests that some NGOs also have signals (SIGINT) and geospatial (GEOINT) intelligence capabilities (Weinbaum et al. 2017; Rothe and Shim 2018). These activities extend the proposition of Gentry (2016, p. 487) that NGOs only overtly gather HUMINT.

For ethical reasons, the research did not address sources and methods in depth, however it sought to explore whether the observation of Gentry (2016) that humanitarian advocacy NGOs consider “security of sources and methods” to be of “minimal” concern (p. 486), held true for environmental crime NGOs. The survey (question number 12) indicated that the vast majority of respondents considered security of sources and methods to be highly important (n = 9, 82%), and these findings starkly diverge from Gentry (2016, p. 486).

On technological advances (Cope 2008, p. 407), interviewee P2 expressed the need to tap into different talents and undertake innovation, but expressed scepticism about how far technology can help NGOs to deliver tangible impact. Other interviewees explained how in particular, OSINT can present opportunities to identify and develop intelligence (P3 and P5), and two interviewees referred to the requirement to undertake OSINT investigations with adherence to defined protocols and policies (P4 and P5).

Interviewees did not describe utilisation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology, as numerous professions have increasingly adopted AI-powered tools since the research was conducted; meanwhile, AI governance architecture is still developing, within which national policy frameworks are taking different approaches (Radanliev 2025, paras. 2–3).

Criminal justice applications of AI include predictive policing, risk-assessments to inform judicial decision-making and surveillance (Talukder and Shompa 2024). In environmental crime, AI applications can, for example, promote transparency in governance mechanisms, produce intelligence on illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, and identify individual tigers from skins detected in illegal trade (Welch et al. 2024, pp. 1685, 1688–90; Paolo et al. 2024; Data Study Group Team 2023), although internet connectivity which may challenge working from remote areas. Moving forward, it may be anticipated that NGOs could increasingly leverage AI tools to generate tactical, operational or strategic intelligence; for example, through AI interfaces to enhance OSINT capabilities, to process or analyse multimedia content, or to gain quick and accurate warnings of deforestation or pollution (Rigano 2019; Ogunwumi and Matindike 2025; University of Southampton n.d.). In parallel however come considerations around AI’s environmental impacts and ethical challenges not limited to privacy, transparency and algorithm bias (Konya and Nematzadeh 2024; Talukder and Shompa 2024; Council on Criminal Justice 2024).

3.1.4. Security Management

Security management of intelligence gathering is important (DemMars 2001, p. 205), and more generally, NGOs may incur risk and suspicion when networking with government agencies, or can be subjected to threats, intimidation and imprisonment (Whitford and Prunckun 2017, p. 58; Thiện 2023; Global Witness 2023). Gentry (2016, p. 484) considered counterintelligence to be effectively irrelevant for NGOs, but there exist examples which show that state security agencies have exploited journalists and NGOs (Karataş 2018). One isolated but notable offering has raised similar questions about environmental NGOs (Corkeron 2023) but does not assess whether NGOs practise counterintelligence.

Interviewees described how NGOs are affected by the security environment while in the field, which creates a responsibility to ensure the safety of personnel, especially in remote areas (P1 and P5). P5 described risk assessments, and mitigation and backup plans. Particularly, the digital age presents both opportunities and threats; where appropriate, NGOs can exploit OSINT rather than visiting physical locations (P5) however internet-enabled infrastructures are increasingly at risk of cyberattack (P1).

3.1.5. Ensuring Accountability

Discussions about governance were particularly noteworthy. One interviewee reflected upon the number of NGOs active in the sector and referred to the presence of different levels and standards to emphasise the importance of ethical practices (P5).

Most interviewees (P1, P3, P4 and P5) referred to the need to adhere to data protection legislation and cited internal structures and protocols that had been designed by personnel with enforcement or legal expertise, along with organisational policies such as about safeguarding and the publication of information. For external governance however, it quickly became clear that there is no single external oversight structure or agency to govern how NGOs are conducting investigations and intelligence.

Charitable organisations can fall under regulators—for example, in England and Wales the Charity Commission can launch inquiries (Charity Commission for England and Wales 2022), while institutional donors can restrict funding and conduct audits. One interviewee explained that while audits take place to ensure that NGOs fulfil donor requirements, the scope of these audits is not specifically focused upon intelligence-gathering (P1). Although institutional donors are considered to be important actors who provide the parameters of projects, they themselves require expertise in order to accurately assess funding applications (Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC) 2014, pp. 28–29) and certain donors can convene expert reviewers to advise upon the technical aspects of funding applications (e.g., Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund n.d.). It is however unclear how many donors—to include private trusts and foundations—employ this measure. P5 supported the notion of donor oversight:

Obviously, the NGOs receiving the money have the ultimate responsibility, but donors also should be not afraid to ask questions, and particularly be aware of risks in certain jurisdictions.(P5)

Membership charities are also accountable to their members, as demonstrated when an estimated 7000 members stopped making donation payments to Oxfam following allegations that its personnel committed sexual misconduct in Haiti (BBC News 2018). In this manner, civil society groups and the media provide valuable informal oversight (Aldrich 2009, p. 55) to expose malpractice and call for greater NGO accountability (P5).

Interviewees with knowledge of the international wildlife protection sector were aware of past controversies, whereby media alleged that some NGOs in receipt of funding had supported park rangers who committed human rights violations, and which resulted in an audit into human rights protections (Warren and Baker 2019; United States Government Accountability Office 2020). Interviewees reported that they were aware of NGO efforts to improve safeguarding of indigenous people around protected landscapes (P4), and that donors build safeguarding requirements into funding applications (P5). Human rights groups however continue to identify a number of issues with conservation NGOs, including the exclusion of indigenous people from decision-making and benefit-sharing, and shortcomings in the scope of internal governance frameworks and record-keeping (Luoma 2022, pp. 27–32). A worthy future line of inquiry could explore how the scrutiny of protected area management has affected NGOs’ openness to local civic participation, and how social trust impacts upon intelligence gathering (Innes 2006, p. 239; Sigsworth 2019, p. 2).

Informal oversight by civil society may reveal “spectacular abuse or scandal” (Aldrich 2009, p. 56) but it remains crucial to institutionalise accountability. It is certainly understandable that by virtue of operating in close geographical proximity to natural resource exploitation, some NGOs might passively gain knowledge about environmental crimes, yet the topic of NGO transparency had been suggested during the earlier research to determine the survey sample, when the researcher found contemporary third party publications which described the intelligence-gathering activities of some NGOs in detail, but found no corresponding evidence on the same NGOs’ own websites. One interviewee highlighted how it was vitally important for NGOs to be transparent about their engagement in intelligence gathering:

You can’t (gather intelligence), get a load of money from a donor for it, but then not acknowledge it in the public domain. Not only is it not ethically right, it’s also going to get your organisation into trouble and probably get people into trouble as well.(P4)

This observation nuances that of Gentry (2016, p. 471), who concluded that there was insufficient transparency in NGOs’ influencing tactics, rather than their intelligence-gathering per se. Furthermore, and contrary to requirements in the NIM minimum standards around people assets (National Centre for Policing Excellence (NCPE) 2005, p. 43), and according to one interviewee, not all NGOs appoint a person to take formal responsibility for their intelligence gathering or intelligence processing functions: some NGOs may find it difficult to define who is responsible for intelligence gathering, which impacts upon the ability to sufficiently address human rights as impacted by intelligence gathering—for example, right of privacy, right to life and right to a fair trial (P4).

By contrast, most survey respondents (n = 9, 82%) indicated that their organisations had created formal named roles dedicated to specific intelligence functions (question number 13); one further respondent was working in an organisation where the formalisation of roles was underway, and one further response was inconclusive. One explanation for this apparent discrepancy between survey results and interviewee perception may be that the survey outreach requested participation from intelligence roles (among others) so NGOs without such roles may have been less inclined to participate in the survey.

In the UK, high-level inquiries have led to changes in policing practices and accountability (Cope 2008, p. 406). It is hoped that NGOs are proactive enough to identify and address any governance and accountability gaps, rather than enabling practices with implications for human rights and reputational risk that could precipitate injustices and scandals.

3.1.6. NGO Professionals Generating Intelligence

The survey contained two demographic questions (questions number 3 and 4) to ascertain the current role of the participant and their professional background. Results showed that NGOs professionals working on intelligence are not restricted to having a background in traditional intelligence sectors such as law enforcement or security agencies: from 11 responses, five had a scientific background, three an intelligence role in the public or private sector, two selected ‘other’ and one had been an officer in a law enforcement, military, security or regulatory agency. P1 affirmed these results as likely to have been influenced by factors such as wildlife conservation NGOs synergistically expanding into wildlife crime-focused projects. Some interviewees (P3 and P4) felt that these demographics influence the working practices within the sector, firstly because NGO personnel will not develop intelligence or put together operational plans in the same ways as police, and secondly their goals are geared towards environmental protection rather than investigative and judicial actions and ensuring that a case succeeds at trial (see also James 2017). This broadly coheres with the finding of Gentry (2016) that NGO goals influence their policies and practices (p. 483). On the other hand, given that NGO professionals are indeed involved in some aspects of intelligence work, some pragmatism may be required, including through the provision of training from experts (P4).

3.1.7. Intelligence from Tasking to Production

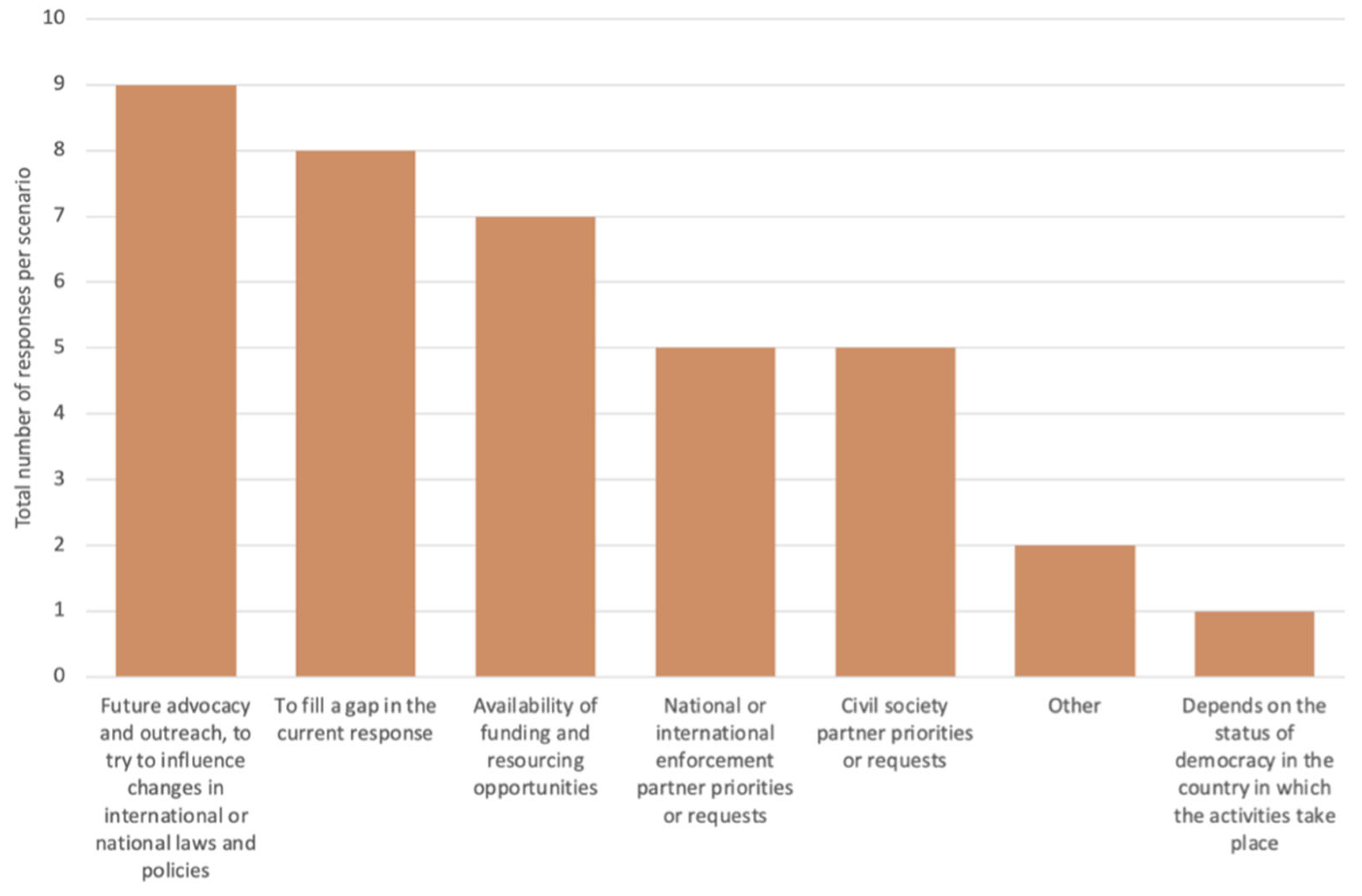

The survey sought to identify the factors which determine the setting of NGO intelligence priorities (survey question number 8), but in order to mitigate potential sensitivities, asked only about external factors which influence priority setting. As shown in Figure 1, the strategic need to inform future advocacy and outreach was the most important external factor in the setting of intelligence priorities, while the need to fill a gap in the response and the availability of funding were more influential than partner requests.

Figure 1.

External factors that determine priority-setting (survey question 8, multiple choice). Created with flourish.studio: https://flourish.studio/.

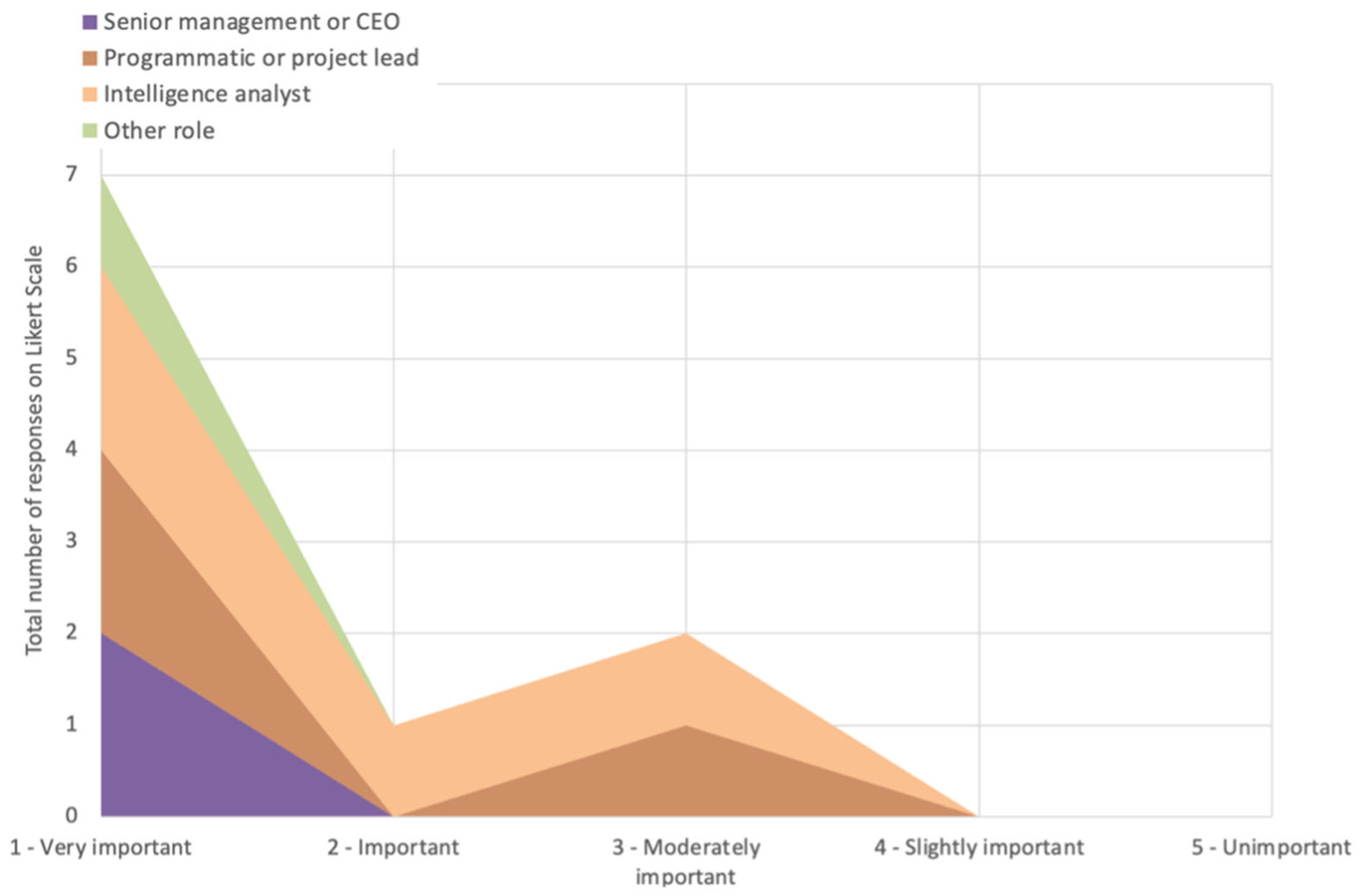

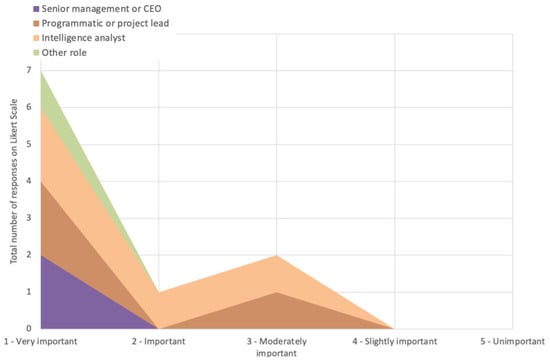

Interviewees reflected that having personnel with dedicated roles and responsibilities can help NGOs to better identify trends and priorities, and improve the collation, processing, analysis and sharing of intelligence (P3 and P5). All survey respondents felt that a formal phase of analysis to delivering outputs was important, and the majority (n = 7, 64%) felt analysis to be ‘very important’ (survey question number 9; Walsh 2011, p. 235). Senior managers considered analysis for outputs to be ‘very important’ whereas the views of programmatic or project leads were more distributed, as shown in Figure 2, which also shows one unexpected result that an analyst felt analysis to be ‘moderately important’. However, when the same data was aggregated against the status of implementation of intelligence models, it was found that the same analyst was operating in an organisation without a formal intelligence model. Further research would be required to firstly, identify any correlation between the perception of importance of analysis and the status of implementation of frameworks, and secondly, to compare the perceptions and experiences of NGO analysts with empirical research from police settings (Cope 2008, p. 409; Ratcliffe 2016, p. 134; Burcher and Whelan 2018, pp. 149–50).

Figure 2.

Importance to delivery of outputs of a formal phase of intelligence analysis (survey question 9), by respondent role (survey question 3). Created with flourish.studio: https://flourish.studio/.

Two interviewees (P1 and P3) variously explained that tactical, operational or strategic intelligence (National Crime Agency n.d.) might be produced as dependent upon the individual NGOs’ missions, and P2 considered that strategic intelligence analysis was more common generally, as apparent through the production of research reports. The latter could be reflective of the fact NGOs prioritise around the strategic need to inform future advocacy and outreach, as previously shown in Figure 1, and share intelligence to a range of consumers with different needs and mandates including government policy makers, as shown in Figure 3 below, while less frequently to directly apprehend offenders, as shown in Figure 4 below. Furthermore, strategic intelligence can make use of published academic and grey literature and qualitative research interviews, which are accessible sources for NGOs.

However, the research intentionally did not explore the intelligence products developed by NGOs, thereby precluding a comparison to Gentry’s findings (Gentry 2016, p. 485) along with further insights about how research affects organisations (Walsh 2011).

3.1.8. Intelligence Frameworks

In order to meet the investigative challenges posed by other forms of serious and organised crime, government agencies have recognised the need to implement structures and efficient procedures and operations (Jacobs and Hough 2010, p. 105; Kuloglu 2016, p. 115). Standardised police information management processes (Cope 2008, p. 406) seek to mitigate risks arising from poor practice (College of Policing 2023, sct. 4).

Several interviewees reflected upon the benefits of implementing practices also used in police information management, for example, three interviewees referenced the benefits of centralised intelligence (P3, P4 and P5), and two interviewees described the benefits of standardised intelligence reporting, to, respectively, create an audit trail and deliver reports in recognisable formats (P3 and P5).

The survey sought to discover the extent of implementation of formal intelligence frameworks, also known as models (Walsh 2011) as addressed by survey question number 7. The vast majority (n = 10, 91%) of responses (n = 11) indicated that formal models are being used to some extent: five respondents were using elements of one formal model but adapted for NGO purposes; two respondents were using one model from law enforcement, military or national security, two respondents were using elements of different formal models, while one respondent stated that no formal model was used. One additional response selected two options ‘Elements of one formal model but adapted…’ and ‘Elements of different formal models’.

The associated free-text field (survey sub-question number 7a) elicited one response which stated the respondent’s NGO used ‘the Intelligence Cycle’, which depicts how raw information is developed into actionable intelligence through stages and which has been applied to policing and military intelligence (Kuloglu 2016, p. 116; Budhram 2015, p. 51; Abilova and Novosseloff 2016, p. 6). The utility of the Intelligence Cycle however remains a point of debate, particularly because of its simplicity (Pythian 2008, p. 56; Hulnick 2014, p. 56), and alternative depictions have sought to better represent the practical reality of networked and non-linear intelligence (Gill 2008, p. 219; Omand 2013, p. 138; Kruger et al. 2022, pp. 610–11).

For example, the 3-I model as proposed by Ratcliffe (2005; 2016, pp. 80–84) offered the advantage of clarifying the role and contribution of intelligence to decision-makers, who then enact interventions in the criminal environment (Ratcliffe 2005; Burcher and Whelan 2018, p. 149). In this manner, the 3-I model might also depict how NGOs provide intelligence to—notably, external—decision-makers; although in policing, the model was found to be better suited to tactical offender targeting (Coyne and Bell 2015, p. 33; as cited in Phairoosch 2019, p. 50; Walsh 2011, pp. 118–20). Nevertheless, alternative models might be interpreted as showing components of practice rather than being frameworks per se (Walsh 2011, pp. 93–94). The model of Scanning, Analysis, Response and Assessment (SARA) (Eck and Spelman 1987) is a primary component in problem-solving approaches and has been applied to protected areas (Lemieux et al. 2022), but Walsh considered it more a tool for analysis (Walsh 2011, p. 93). The NGO tendency toward adaptation of models might similarly indicate components of practice.

Aside from the Intelligence Cycle, the only framework reported by the survey participants was the NIM (n = 3; National Centre for Policing Excellence (NCPE) 2005, pp. 14, 33). This reflects findings of police intelligence scholarship which identified that the NIM had been most widely adopted model in other countries, although there are limits to universal transferability (Walsh 2011, pp. 144–45). For example, reporting processes and product templates may have to be changed, and smaller organisations especially may find the NIM bureaucratic, so it may therefore be more accurate to refer to the prevalence of “NIM-like frameworks” which show the foundational components of intelligence but are also adapted to organisational context, the requirements of collection and analytical capabilities (Walsh 2011, p. 145). In discussing the above literature and survey findings, one interviewee appeared to support this:

(Frameworks would) definitely have to be adapted. … To make them, yes, simpler, less bureaucratic, because … the entire process can be daunting or onerous or off-putting for people without that (police) background. … Obviously, there are so many things in the policing world … that don’t exist within an NGO, like a hierarchy, a rank structure … Obviously, lots of things like that can’t apply. But the basic fundamental things … absolutely can apply.(P4)

P4 highlighted certain benefits of an intelligence framework for NGOs, explaining that processes for sign-off and accountability provide protection to NGOs and their personnel.

Another interviewee observed that implementation of intelligence frameworks within the sector was “definitely driven by the people who are there, and their background” (P3), which suggests that motivated people can make a difference within NGOs. On one hand, this scenario raises questions about sustainability, should personnel leave at a point when practices are not widely endorsed or institutionalised, but conversely, new personnel might refine and evolve practices. Secondly, should enforcement professionals come from different countries and agencies which use different frameworks and approaches, it is likely that some heterogeneity in implemented practices will result. One review of police intelligence units in New Zealand found that while “local flexibility of arrangements is often necessary”, significant variations had negatively impacted upon the ability of those units to compare working practices and therefore identify good practice to share innovations further afield (Ratcliffe 2005, p. 446). For the NGO sector, P4 recommended that NGOs might convene and reach agreement around, for example, evaluation systems and data entry standards. In that manner, relevant parts of the NIM minimum standards (National Centre for Policing Excellence (NCPE) 2005) could provide one starting point to identify the way forward, although NGOs with formal law enforcement partners might be expected to favour alignment with partner standards in the first instance.

3.1.9. Enforcement Professionals in NGOs

Interviewees reflected upon the influence of enforcement professionals in the NGO sector. One described enforcement professionals entering the sector as “very well motivated” (P5), and another predicted that, as a result,

(NGOs) would have better structures in terms of how to gather, collect, talk to enforcers, (and) have trainings that mean something.(P1)

In contrast, a third interviewee was more circumspect, citing the knowledge gap between NGO and enforcement professionals which could challenge effective supervision (P2), however along with two other interviewees mentioned successful methods used to assess and ensure the suitability of potential employees or collaborators (P2, P4 and P5).

NGOs might strategically influence policy making even in “semi-authoritarian contexts” (Ayana et al. 2018), yet while NGO cooperation can fill gaps in existing law enforcement approaches (P1), one interviewee reflected that NGOs should maintain a clear operational differentiation from police (P5) when working in countries characterised by weak legal and regulatory frameworks (Barber and Bowie 2008, p. 749).

An inspection of UK enforcement found that a robust governance structure is essential to ensuring assurance and sustainability of HUMINT functions (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) 2010, pp. 8, 12, 21). One interviewee highlighted their concern that due to limited numbers of enforcement professionals in the sector, any NGOs with source management programmes could likely be unable to separate roles and responsibilities between operatives and authorising officers (Home Office 2022), which would cause significant issues around conflicts of interest (P4). The same respondent advised that relevant NGOs should adhere to established enforcement standards, or if unable to, refrain from undertaking such activities.

3.2. NGO Intelligence Sharing—Building Trust for Collaboration

The second theme addresses with whom and how NGOs share intelligence, and the dynamics impinging upon inter-NGO information sharing.

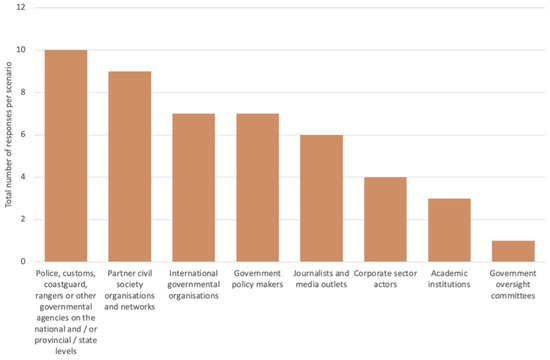

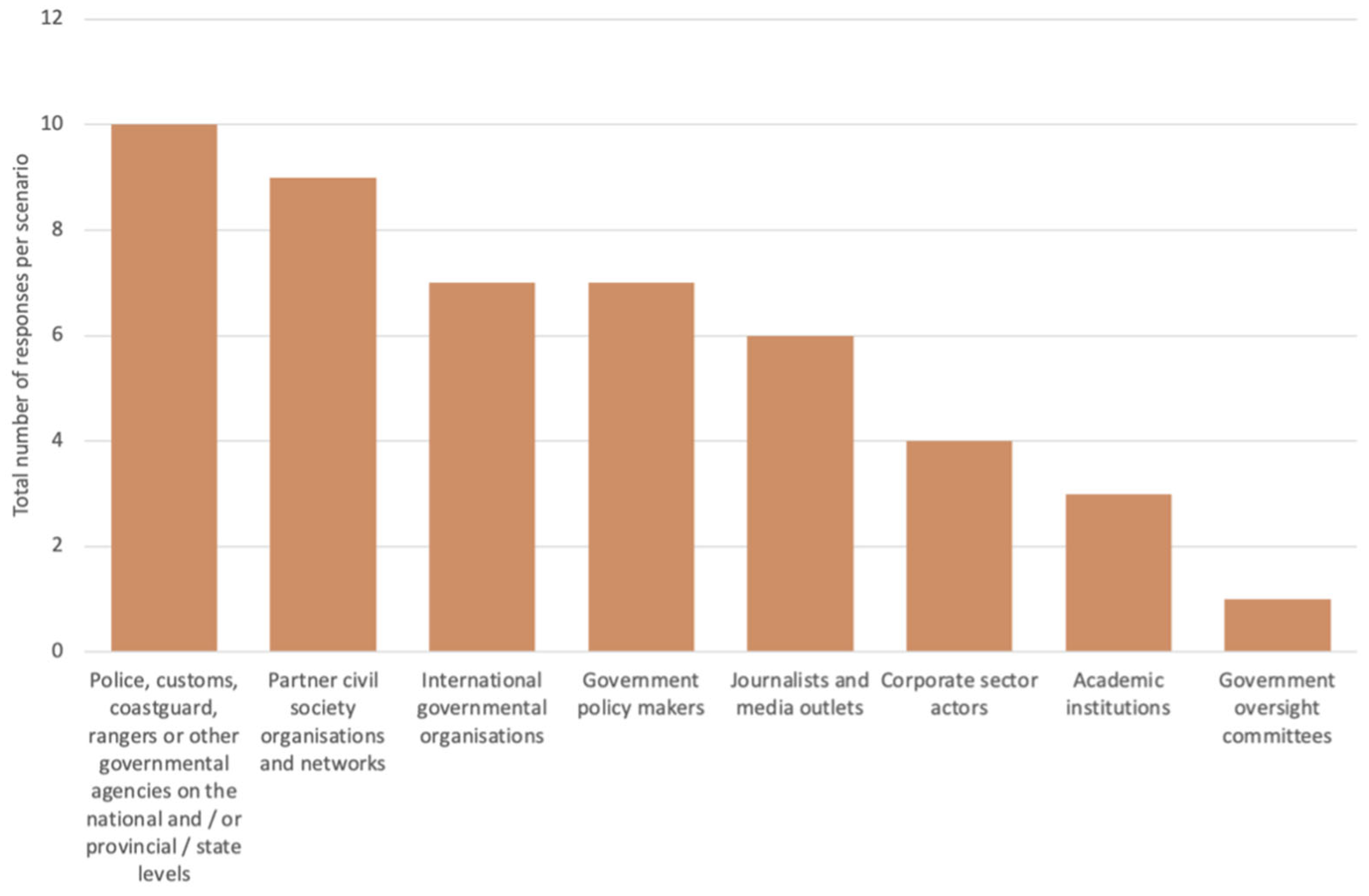

3.2.1. Consumer Mandate

As shown in Figure 3, the survey demonstrated that the most common consumers of NGO intelligence are enforcement or other governmental agencies (survey question 10), and that civil society is a more frequent consumer than government policy makers and oversight committees. One striking feature was that academic institutions appear to benefit less from NGO intelligence, and this was reflected in the interviews whereby only one participant mentioned liaison with academics (P1). While the researcher would expect that intelligence shared to academics would be sanitised and strategic, when these findings are considered in conjunction with the limitations in the literature, it appears that there remain opportunities for NGOs to better network with academics to develop the evidence base for criminology and intelligence studies.

Figure 3.

Intelligence consumers (survey question 10, multiple choice). Created with flourish.studio: https://flourish.studio/.

Figure 3.

Intelligence consumers (survey question 10, multiple choice). Created with flourish.studio: https://flourish.studio/.

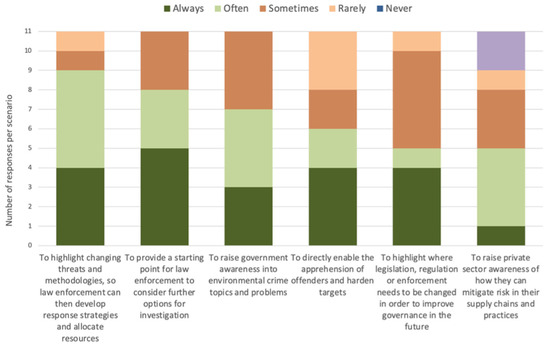

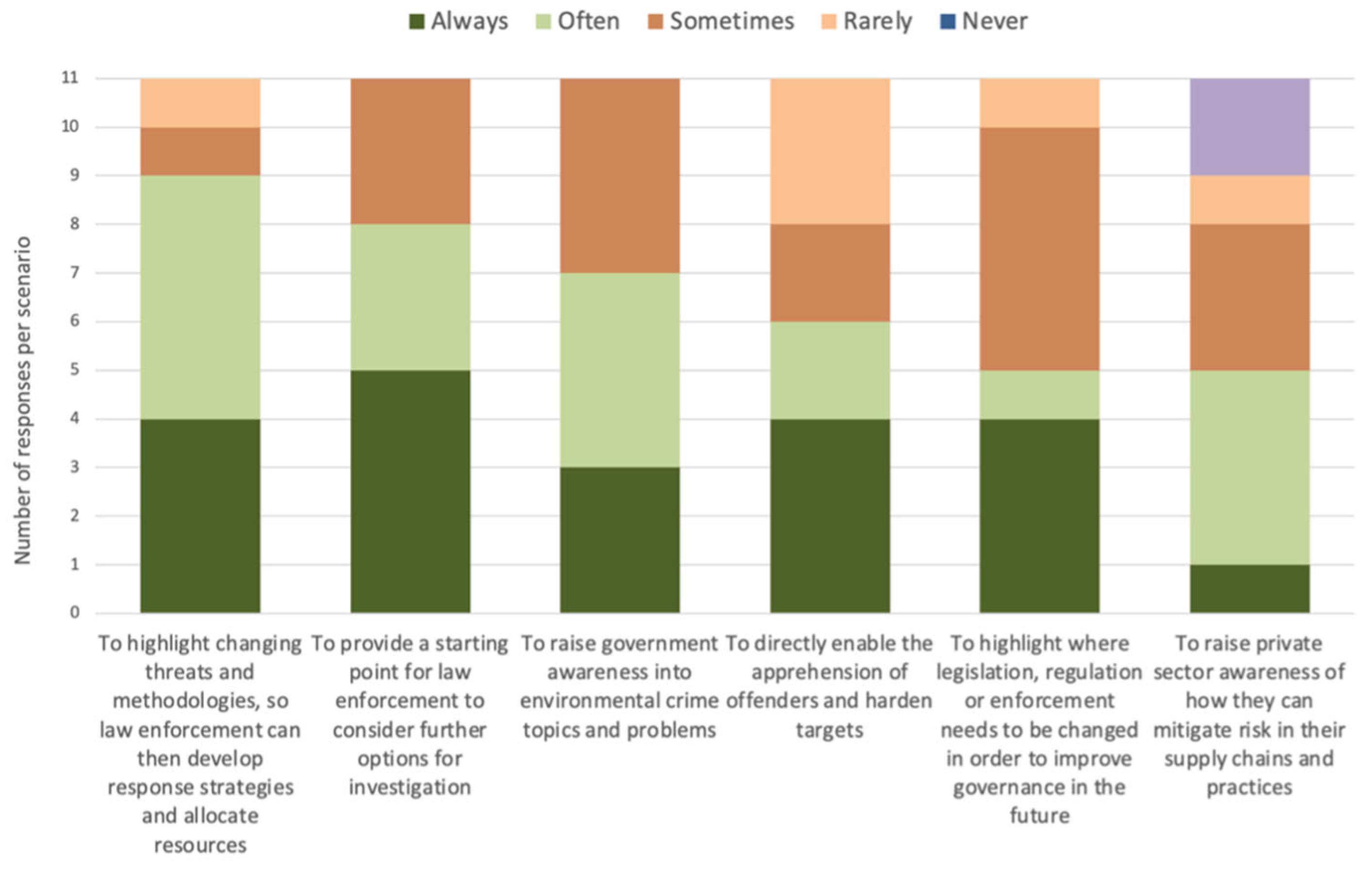

The survey furthermore identified how frequently NGOs provide intelligence against a range of different scenarios or purposes (survey question 14), as shown in Figure 4. A notable number of NGOs ‘always’ provide intelligence to provide a starting point for law enforcement to consider further options for investigation (n = 5), but when the parameters of frequency for provision are widened (to include both ‘always’ and ‘often’, as shown by two green shadings), the most significant purpose is instead to highlight changing threats and methodologies (n = 9), so that law enforcement can then develop response strategies and allocate resources.

It is however less common for NGOs to provide intelligence in order to directly enable the apprehension of offenders and harden targets, which itself has to “be simple to comprehend, not time-consuming to act upon, tactical in nature, and arrest focused” (Ratcliffe 2005, p. 448). Although the private sector is recognised to be an important actor in efforts to tackle environmental crime (FATF 2021, pp. 48–50), the survey indicated that it is not the primary consumer of NGO intelligence, although there are efforts toward cross-sectoral collaboration (Egmont Centre of FIU Excellence and Leadership (ECOFEL) 2021, pp. 58–59). In this manner, NGOs with relevant intelligence could enhance capabilities to develop financial crime typologies and cybercrime scripting, to support the detection and prevention of crime (Murray 2013, p. 104; Scott and McGoldrick 2018, p. 313; Jardine 2021).

Figure 4.

Frequency of intelligence provision against different scenarios (survey question 14, multiple choice). Created with flourish.studio: https://flourish.studio/.

Figure 4.

Frequency of intelligence provision against different scenarios (survey question 14, multiple choice). Created with flourish.studio: https://flourish.studio/.

Previous research has shown that in order to impact upon crime reduction, it is necessary to identify the key decision-makers (Ratcliffe 2005, p. 447), yet these are external to NGOs, being governments and enforcement agencies. Interview participants described their efforts to find intelligence consumers with the right mandates (P1, P3 and P5) and with awareness of potential corruption (P1):

We need to know first who we should send that to. And most of the time, that’s the hardest bit; rather than just gathering intelligence, it’s, ‘Okay, we shouldn’t send this to these authorities or these agencies, because they might be involved, or these, (because that particular environmental) crime is not a priority’. … but it takes years to build the trust and show that we add value—and (that) we’re not just here to be annoying.(P1)

The interviewee elaborated that while agencies do reach out to NGOs and ask for assistance, the direction for engagement is “mostly us being proactive” (P1).

3.2.2. Personal Relationships

Although intelligence exchange is vital to combat transnational organised crime, it is likely that those sharing will still feel some circumspection (Brown 2009, p. 189). This research revealed that trust is the overarching condition in any effort to share NGO intelligence. The interviews furthermore showed that personal relationships are extremely important to whether and how NGOs share with enforcement (P1, P4 and P5) and that these pave the way for either informal or formal sharing.

P5 explained that in the absence of having a contact in a specific country, regional enforcement bodies can be of assistance. Obtaining feedback on the outcome of information shared however remains difficult (P1 and P5) which creates problems for programmatic reporting, so NGOs have adapted their approaches to communicate simple parameters of feedback requests (P1) or meet with agencies in person to gain qualitative feedback (P5). This finding diverges from Gentry (2016) who assessed that humanitarian NGOs had mastered “consumer-producer” relations (p. 478), although his statement was not specifically concerned with intelligence provision.

3.2.3. Formality of Sharing

NGOs share intelligence both informally and formally. Memoranda of understanding (MOUs) can take a long time to develop (P1) and do not necessarily result in improved sharing (P4). P1 explained that direct contact with operational officers can be more efficient than navigating agency structures and potentially corruption, but in concert with Liddle and Gelsthorpe (1994), also observed that personal and informal cooperation can be prone to durability issues when people leave their posts.

Informal methods also raise accountability issues (Liddle and Gelsthorpe 1994, p. 29), and although it has been recommended that NGOs should better use secure and ethical informal channels (MacBeath and Stanyard 2023, p. 38), one interviewee explained why they perceived formal sharing to be preferable:

I do hear and see a lot of intelligence which I think, ‘That’s pretty good, we could develop that’—but a lot better it was more formally shared. … (Formal sharing) gives us protection which (means) obviously we’re protecting sources, we’re protecting ourselves as well because we’ve formally reported that to our partners, and it seems to work quite well.(P3)

In the EU, the impact of agency mistrust upon cooperation has been somewhat circumvented by an increase in sharing channels using standardised tools (Aden 2018, p. 998), although it can be challenging to develop that intelligence towards organised crime investigations (Brady 2008, p. 107). P3 observed that one of the barriers to formal sharing by NGOs was that there is no one central body with which to share. One properly resourced central repository could also enable the mapping of organised crime groups (OCGs) towards the development of threat assessments to inform the development of intervention strategies (Brady 2008, p. 108; Murray 2013, pp. 100–1; Denley and Ariel 2019, p. 35).

Further afield, agency information sharing and coordination has been found to depend upon not only integration of systems but also systems quality, organisational norms, and values and incentives, which points toward the need for problem-solving at all levels (Bharosa et al. 2010, p. 63).

3.2.4. Silos and Conditional NGO Collaboration

Interviewees believed that inter-agency and inter-NGO silos create barriers to sharing. P1 explained that rivalry and credit-taking might negatively influence inter-agency relationships, so networking opportunities for enforcement officers helps to establish trust and rapport on a personal level.

Another interviewee felt that what was required was:

[Enhanced] collaboration between different organisations, without a shadow of a doubt.(P3)

The UK response to organised crime since the 1960s resulted in the creation of multi-force squads and centralised structures (Stelfox 1998, p. 402), and two interviewees cited multi-agency taskforces as beneficial (P3 and P5). Nevertheless, implementation should be supported by evaluations which are able to discern whether the partnership action itself achieves goals, as opposed to the actions of agencies in isolation (Rosenbaum 2002, p. 212).

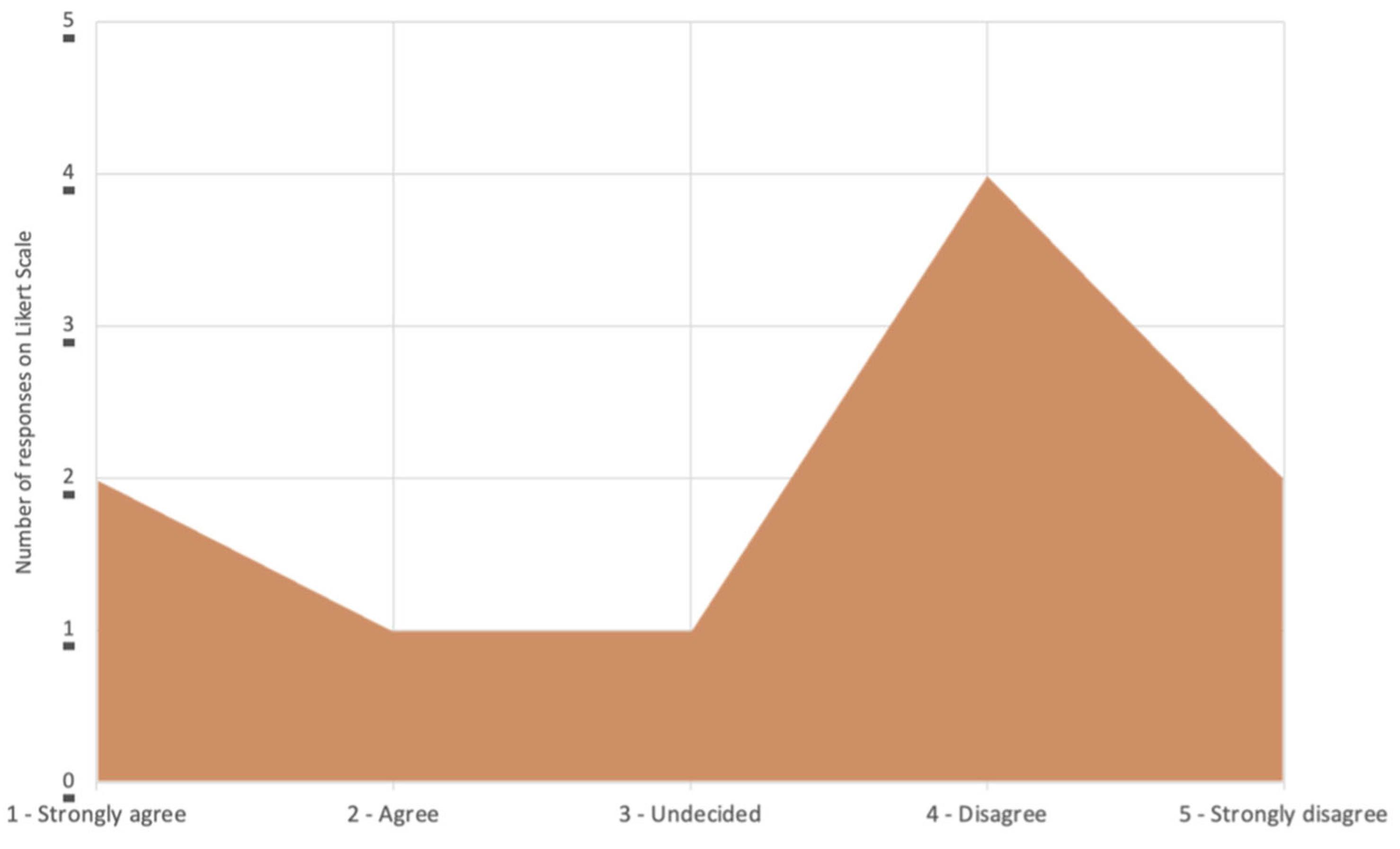

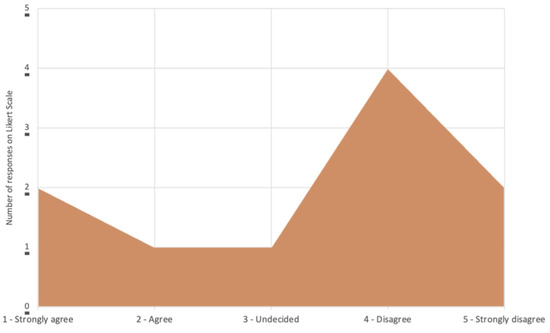

As noted above, survey question 10 established that civil society partners are important consumers of intelligence, and survey question 11 asked participants to rate how strongly they agreed with a statement derived from Gentry (2016) that “NGOs share intelligence with each other more than governments share with each other” (p. 478). The results showed a divergence of opinions, as shown in Figure 5, and overall showed a divergence from Gentry’s observation that regular and large-scale NGO sharing takes place, at least for humanitarian actors (Gentry 2016, p. 488).

Figure 5.

Level of agreement with the statement “NGOs share intelligence with each other more than governments share with each other” (Gentry 2016, p. 478; survey question 11, Likert Scale). Created with flourish.studio: https://flourish.studio/.

One interviewee explained that NGOs appeared to be protective about intelligence they were developing, but:

…Then again, (NGOs) are siloed. Because obviously they’re all competing for funding, so a lot of them (say), ‘It’s our intelligence, we’re not going to share it’.(P3)

In 1999, the police inspectorate for England, Wales and Northern Ireland pointed out that while intelligence should be protected, ‘need to know’ cultures “should not be used as an excuse to avoid freely sharing information with partnership agencies” (HMIC 1999, p. 5). As an interviewee pointed out:

There’s only one winner if you don’t share, and it’s the criminals.(P3)

P1 pointed to an array of potential barriers to inter-NGO information sharing, including personality and political differences, lack of knowledge about or access to networks, information leaks and perceived undue credit-taking—all within an environment in which NGOs compete for funding—while P4 perceived that sharing was determined by coherence with the recipient NGOs’ ethics and values. NGO cooperation therefore appears highly conditional upon not only trust but mutual values and defined parameters. P1 however commented that in more recent times:

NGOs that weren’t talking previously now (have) started talking, started coordinating. Even on training. Because sometimes you would see that two NGOs are doing the same training at the same time—to the same agency…(P1)

P1 felt that these positive changes had been driven by collaborative individuals within different NGOs.

Yet as the survey and the issues described above demonstrate, NGO cooperation may be a work in progress. P2 explained that there are NGOs who “know how to collaborate” which forms the basis for joint working on specific matters, however:

Thus, ultimately, they found that this potential was yet to be fully realised.When you compare that with the apparent potential, it’s like, ‘Wow, we have so many (NGOs) working on intelligence!’(P2)

3.3. Delivering Meaningful Change—Recognising and Reforming the Operating Context

The third and final theme considers the operating environment for NGOs, addressing where they see the opportunities for impact in the context of organised crime and corruption, and eliciting the influence of funding on their activities.

3.3.1. Organised Crime and Corruption

All survey respondents (n = 11) felt that environmental crime involves organised criminal activity (survey question 5), with responses weighted towards greater frequency: the majority felt that it ‘frequently’ features (n = 7, 64%), while a smaller proportion that it ‘always’ features (n = 3, 27%). Only one response felt it ‘sometimes’ features (9%). Despite some small variance, this finding coheres with the prevalent opinion of the multilateral environmental crime policy space (Haysom and Shaw 2022, pp. 16–18), rather than academic opinion. Interviewee P2 described features of crime groups to support the notion of lowercase ‘organised crime’ involvement (Hagan 2006, p. 134).

Three interviewees mentioned convergence with other forms of crime (P1, P2 and P3), of which two mentioned convergences between some environmental crimes and drugs and firearms offences (P2 and P3). One interviewee observed that “it doesn’t really matter” what illegal environmental commodity is traded:

It’s just another commodity for people to make money.(P3)

Money laundering and corruption are inherent parts of organised crime (Gottschalk 2008, p. 284). One interviewee explained that the lower-level offenders level are “replaceable” and that enabling corruption can occur in different levels of government and in the courts:

Places where people will be replaced, can be replaced, but the function remains the same—so the newcomer will be told what needs to happen: ‘That’s what we do, and you are a part of that’.(P2)

Indeed, when corruption is endemic in police institutions, it can rightly be considered as a national security issue (Hope 2018). While mindful of changing geopolitical landscapes, P1 predicted that it might become necessary for NGOs to adopt interventions and perspectives that are more “systemic, and not looking at one culture, or one animal” and also observed that, given the importance of corruption, more NGOs could undertake work to tackle corruption. Where safe to do so, this might be activated through NGOs including governance reform and anti-corruption activities as part of core programmes of work. Ultimately, tackling it will require sustained and unwavering commitment. One interviewee emphasised the shared responsibility for future change, in that

(The current response is) still a drop in the ocean, and unless enforcement bodies around the world, as well as NGOs, assume more responsibility … we are not going to win this.(P2)

3.3.2. Achieving and Measuring Impact

In the UK, the response to serious and organised crime has followed operational priorities aligned with “the 4Ps” (His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) 2020, pp. 3, 5, 11). This means that agencies pursue organised criminals through investigation, disruption and enabling prosecution, prevent those at risk from becoming involved in organised crime, and protect and prepare individuals, businesses and systems from the impact of organised crime (National Crime Agency 2015, p. 5; 2022, p. 8; Her Majesty’s Government 2018, pp. 18–19). Meanwhile, operational enforcement acts upon identified and prioritised risks, including those associated with OCGs (Home Office 2018; HMICFRS n.d.; 2021, p. 11).

Ethical considerations determined that the research did not specifically explore targeting, however two interviewees broadly mentioned that organised crime dimensions informed where they focused resources:

We don’t touch poachers; we only deal with traffickers.(P2)

Another acknowledged the importance of anti-poaching work but stated that instead the focus was on those

…Who we think disruptively (have) a much greater impact. … We go after the people who are making the big money.(P5)

In connection, Stelfox (1998, p. 405) cautioned that targeting of organised crime should not neglect its local dimensions, but it remains an open question how far, for example, localised NGOs and international NGOs share or integrate intelligence to coordinate approaches across supply chains, even on the strategic level, or with other NGOs working on localised crime issues that converge with environmental crime.

Although NGOs have different missions to police, some interviewees expressed goals in terms of the disruption or deterrence of environmental criminals. P3 explained that outreach presents NGOs with opportunities to encourage agencies to identify strategic intelligence which might then be developed to identify operational targets towards disruption. The College of Policing has produced a practitioner toolkit on disruption (College of Policing 2022, pp. 4–18) which might be adapted to environmental crime scenarios, because its scope coheres with the mandates of criminal and civil agencies. However, the disruption of crime organisations can be considered as separate to overall crime reduction efforts, and measurement of disruption may require a large number of indicators to develop a composite picture (Kirby and Snow 2016; Levi and Maguire 2004, pp. 454, 456).

One interviewee felt that deterrence involved removing the financial incentives for crime (P1), while another explained that criminal perception of the likelihood of incarceration was itself a deterrent:

The higher (up) the person is, the more deterrent it is—as opposed to a fine or anything that is financial, when the higher you go, the less it matters.(P2)

For wildlife crime, recent years have seen efforts in inter-disciplinary research to assess whether and which deterrence strategies are effective to inform future actions (Science for Nature and People Partnership n.d.), but quantifying impact more broadly remains a work in progress. Donors request indicators of impact, but these can be limited in scope and not tied to strategic outcomes (Haenlein 2025) which presents the need for learning and adaptation (Wildlife Justice Commission 2025). The issue is not particular to environmental crime NGOs; Ratcliffe (2002) observed limitations in the evaluations of intelligence-led police initiatives with the result that the “occasional short term achievement may not be a good indicator of long term success” (p. 61).

P1 explained that showing impact is important to ensure alignment with the overall organisational mission and to maintain the internal sustainability of programmes, but acknowledged that measuring impact against illegal trade is difficult because NGOs are working against an unknown baseline. Another interviewee observed the following:

It’s not a linear kind of work for you to say, ‘I see the impact here, I see the impact here’. … So we chose as an indicator. … There can be others but there must be something. There must be something tangible.(P2)

For strategic impact, P2 cautioned against the application of indicators associated with workshops which are “not linked to any change”. Indeed, research on improving police accountability in Africa has shown that institutional values must be reformed before managerial and capacity-building efforts can impact upon daily police practice (Auerbach 2003, p. 312).

3.3.3. Funding

Political attention to environmental crime issues ultimately enables the availability of financial resources available to NGOs. Interviewee P5 explained that by virtue of high poaching levels, the emotive power of wildlife and high-level political announcements, wildlife issues had come to receive greater political attention than other forms of environmental crime, and that this resulted in more funding for wildlife crime work specifically. An obvious consequence is that there is a clear imbalance within the NGO sector, and fewer NGOs are working on environmental crime such as pollution or climate-related crime, which remain neglected. This may change as the world warms and the visible impacts of climate change affect more lives, but the question remains—at what pace? Two interviewees referred to some potential future expansion of governments and agencies working on other types of environmental crime (P4 and P5), and P5 felt that best practice from tackling wildlife crime could inform such future efforts.

Since this research was originally conducted, the NGO landscape has significantly altered, only to further emphasise the importance of funding to NGOs. In early 2025, the United States froze its foreign development assistance and following similar measures undertaken by other countries in recent years, the United Kingdom announced aid budget cuts (O’Sullivan and Puri 2025). The non-profit sector generally has been significantly disrupted, and environmental protection NGOs have ceased programmes of work and shed personnel (Mukpo 2025). NGOs are already refocusing toward critical activities—which may exclude intelligence if that function is less integrated within their core missions. Looking ahead, NGOs may increasingly form cooperative partnerships to access funding; funding might increasingly favour localised responses and host country governments could increasingly fill the gap, or there may be a shift towards more holistic, preventative responses (Welz 2025; Haenlein 2025; Ali 2025).

4. Conclusions: Toward a ‘Green Intelligence’?