1. Introduction

A preliminary regulatory framework for e-CNY has been gradually sketched out since the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) issued its whitepaper on China’s CBDC in 2021 (

People’s Bank of China 2021). Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP), commonly known as e-CNY or the digital Yuan, is a pilot program that started in 2020. After three years of exploration, DCEP is demonstrative of how CBDC operates within China’s regulatory framework (

Xu 2022). As many countries have yet to implement their CBDC plans (

Powell 2021;

Labonte and Nelson 2024), a closer look at China’s pilot program will help regulators worldwide determine what steps are mandatory to accommodate their future currencies.

CBDCs are currently still being explored by most countries, as it is still up to their central banks to determine who can use CBDCs, which technologies to employ, and what upcoming restrictions to implement (

Auer and Böhme 2020); these include the Federal Reserve (

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston 2022), the European Central Bank (

European Central Bank 2024), the Swiss National Bank (

BIS Innovation Hub 2024), and the Riksbank of Sweden (

Riksbank 2024). Only ten countries worldwide have currently launched CBDC pilot programs, and the e-CNY is the most used CBDC pilot among them. Normally, two types of CBDCs exist: retail and wholesale. Wholesale CBDCs are often accessible to financial institutions that have reserve deposits at a central bank (

Dashkevich et al. 2020), whereas retail CBDCs are designed for public transactions (

Chaum et al. 2021). The DCEP initiative is a retail CBDC intended to enhance payment facilities and incorporate digital features into future applications.

As a retail CBDC project, the DCEP has a significant advantage in developing the e-CNY, as China’s e-commerce and mobile payment penetrations have proliferated over the past several years, alongside the expansion of its digital infrastructure (

Klein 2020). The two largest mobile payment networks, Alipay and WeChat Pay, have over one billion users. Customers in China prefer to utilize mobile payment as their primary payment method and, as a result, are more likely to accept CBDC. The two mobile payment networks offer consumers e-CNY as a payment option, thereby integrating e-CNY into the existing mobile payment ecosystem. As e-CNY has been incorporated into China’s two largest payment platforms, the DCEP will utilize the mobile payment prevalence to its fullest extent to promote e-CNY.

According to the PBOC, another benefit of DCEP is its low-cost fee resulting from its design (

People’s Bank of China 2021). The e-CNY would accrue additional advantages for merchants’ solid cash flow. For instance, the e-CNY wallet is an inexpensive payment platform for merchants, and the low cost of merchant fees is another benefit of e-CNY compared to Alipay’s merchant cost of roughly 0.55%, WeChat Pay’s 0.6%, and Unipay’s 0.8%. For further comparison, Visa and MasterCard charge an average of 0.9% in Merchant Fee, while American Express charges an average of 1.4%. Having no merchant fees and expedited payment reduces vendor operational expenses. In addition to lowering merchant fee costs, the point-to-point settlement function of e-CNY might improve merchants’ cash flow and raise the efficiency of capital utilization (

People’s Bank of China 2021).

The PBOC’s whitepaper on the DCEP program provides an overview but lacks further detail. After analyzing the 290 patent applications filed by the PBOC and the three-year duration of the DCEP pilot program

1, we have identified the implementation path for the whitepaper’s core features—namely, no interest accrual, controlled anonymity, and smart contract programmability. The Chinese authorities are attempting to create a CBDC system that is more compatible with the existing regulatory structure. Nonetheless, some features may be incompatible with the current legal framework and necessitate additional legislation. According to the whitepaper, the e-CNY was designed as a parallel digital fiat currency system to paper currency (

Geva et al. 2021). As a digital currency, the Chinese central bank law has yet to be modified to legitimize e-CNY by adding it to the category of fiat currencies. To ensure that the legal status of e-CNY is identical to that of the paper Yuan, a change in PBOC law is necessary. Article 19 of the PBOC draft law states that e-CNY is another form of Yuan

2. Even so, addressing regulatory conflicts arising from its distinct characteristics remains critical. Summarizing these characteristics provides clarity on the current e-CNY model.

Despite this, the DCEP is in its pilot phase, and several features may be subject to change for various reasons. Inspecting the pilot program within China’s regulatory framework is still worthwhile, as it might demonstrate the pros and cons that a CBDC, with cutting-edge technology, could bring to the financial sector. More relevant is how it will affect the existing regulatory system and how legislators and regulators may react (

Bossu et al. 2020).

This study examines the distinct characteristics of the retail e-CNY and evaluates its integration within China’s existing legal framework. Recognizing that certain provisions of current Chinese law require modification to accommodate specific aspects of DCEP, this research offers targeted recommendations and elucidates how regulators might sustain effective oversight during the formation of a CBDC.

Section 1 delineates the differences between e-CNY wallets and conventional bank accounts, highlighting the rationale behind the non-interest accrual mechanism.

Section 2 explores the balance between regulatory compliance and user privacy, with a detailed analysis of the e-CNY’s anonymity features.

Section 3 illustrates the role of smart contracts in enhancing the currency’s programmability, examines its application in three distinct scenarios, and demonstrates that such programmability does not impede currency circulation.

2. E-CNY Wallets: A Secure Deposit Box Model

CBDCs are generally classified as either account-based or token-based (

Bossu et al. 2020). In an account-based system, users must open accounts with an intermediary, and transactions are validated by verifying the identity of the account holder. This model is in close alignment with the conventional banking system, as it capitalizes on the regulatory and compliance frameworks that financial authorities are already acquainted with. However, users may perceive account-based models as less intuitive or adaptable than token-based alternatives, even though regulators may find them easier to regulate.

Token-based CBDCs operate differently. They function similarly to digital cash in that the token itself serves as proof of ownership, and transactions are verified by the token’s authenticity rather than the identity of the transacting parties. This model has the potential to improve the sense of personal ownership and custodianship, particularly when it is implemented in physical formats such as prepaid cards—e.g., public transportation cards or anonymous gift cards for grocery stores—which are more relatable to users who are unfamiliar or uncomfortable with abstract digital systems (

Narula et al. 2023). Such formats are particularly helpful in regions where digital literacy is low or among populations (e.g., seniors) with a stronger preference for tangible assets.

Moreover, account-based models depend heavily on digital infrastructure. According to the World Bank, nearly 3 billion people globally have limited internet access, and 43% of the population remains outside mobile network coverage. Conversely, token-based CBDCs provide offline payment capabilities, rendering them more practical and inclusive in underserved regions. Nevertheless, these advantages are accompanied by regulatory compromises. Token-based systems are designed to provide a higher level of anonymity, which complicates the enforcement of anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) requirements. Consequently, financial oversight is presented with challenges.

The PBOC’s methodology for CBDC design significantly diverges from the traditional framework, which usually differentiates between account-based and token-based models. Instead, it has innovatively developed an indigenous hybrid model that is particularly designed for China’s internal circumstances. The PBOC’s whitepaper indicates that e-CNY employs three unique carrier-based categories—value-based, account-based, and quasi-account-based—demonstrating an innovative and contextually relevant divergence from globally recognized classifications (

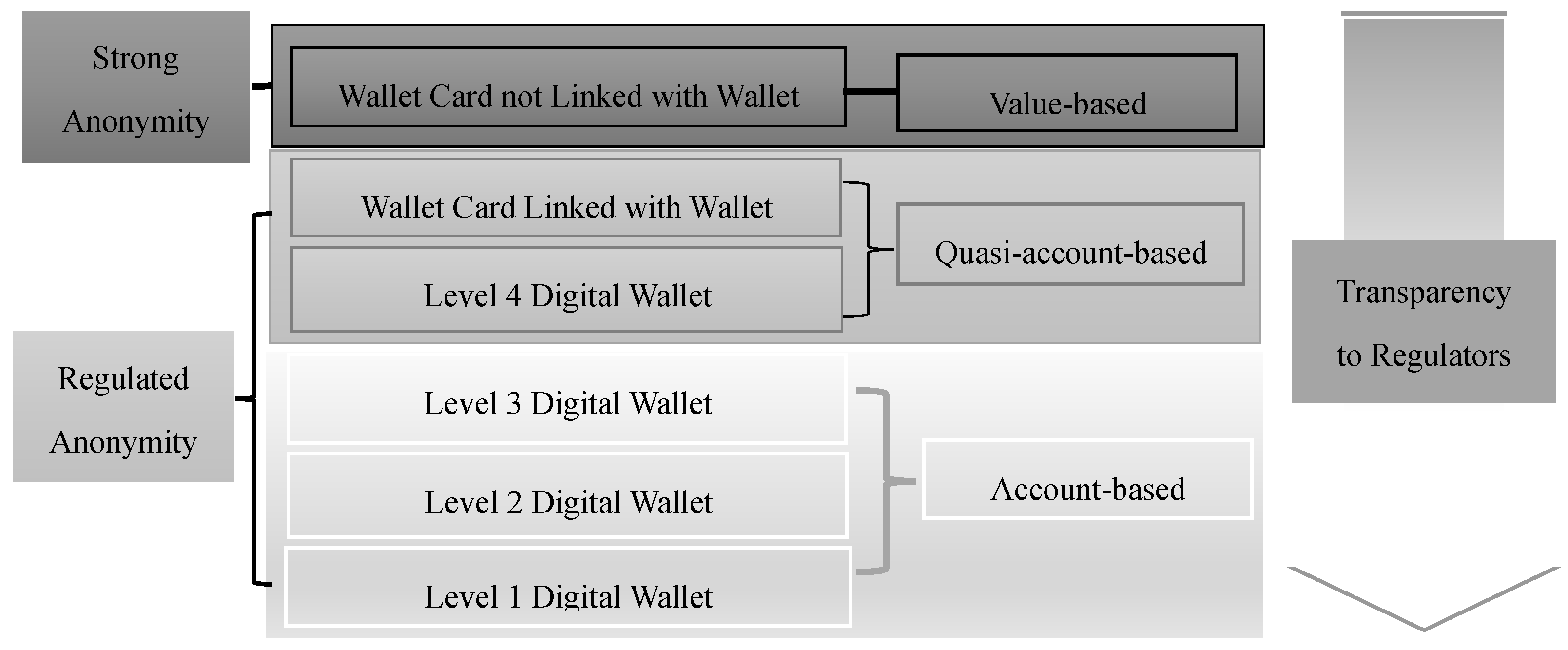

Table 1). These carrier types include not only wallet cards and digital wallets but also SIM card-based applications and other hardware-bound formats. These modes are not fixed and can be dynamically switched based on user behavior and transaction scenarios.

Value-based carriers are instruments that store digital currency directly without requiring identity-linked accounts. Examples include prepaid wallet cards or single-purpose hardware devices. These carriers are suitable for small-value and anonymous transactions. Account-based carriers, such as e-CNY digital wallets registered through banks or licensed platforms, are linked to verified user identities. They enable detailed record-keeping, risk monitoring, and policy enforcement. Quasi-account-based carriers emerge when a previously value-based carrier, such as a wallet card, becomes linked to a digital wallet. Though the card itself may retain some token-like properties (e.g., enabling offline payments), the linkage introduces elements of account-based control, including identity association and usage monitoring. Thus, wallet cards in their standalone form are typically value-based. Once associated with an e-CNY wallet—which is account-based—they effectively transform into quasi-account-based tools, maintaining partial anonymity but gaining more regulatory oversight.

In other words, quasi-account-based carriers represent a distinct hybrid category between the purely token-based and fully account-based models. Initially, these carriers, such as wallet cards, are value-based and issued anonymously, with no direct identity association. However, they transition into quasi-account-based instruments upon linkage to a user’s verified digital wallet. This linkage adds account-like features, including identity association and traceable usage, thus blending token-like anonymity features with account-based regulatory oversight. The essential distinction between value-based and quasi-account-based carriers in the e-CNY system is the degree of anonymity associated with the user’s identity; quasi-account-based carriers involve partial identity verification (e.g., registration via phone number without full linkage to a national ID), rather than complete anonymity.

Notably, the boundary between quasi-account-based and fully account-based carriers is intentionally flexible and often blurred, reflecting strategic considerations regarding privacy and regulatory compliance. Users and regulators can dynamically adjust this boundary according to specific transactional scenarios and risk assessments. This flexibility allows the PBOC to strategically balance user privacy with necessary oversight, adapting to evolving financial security requirements and user expectations.

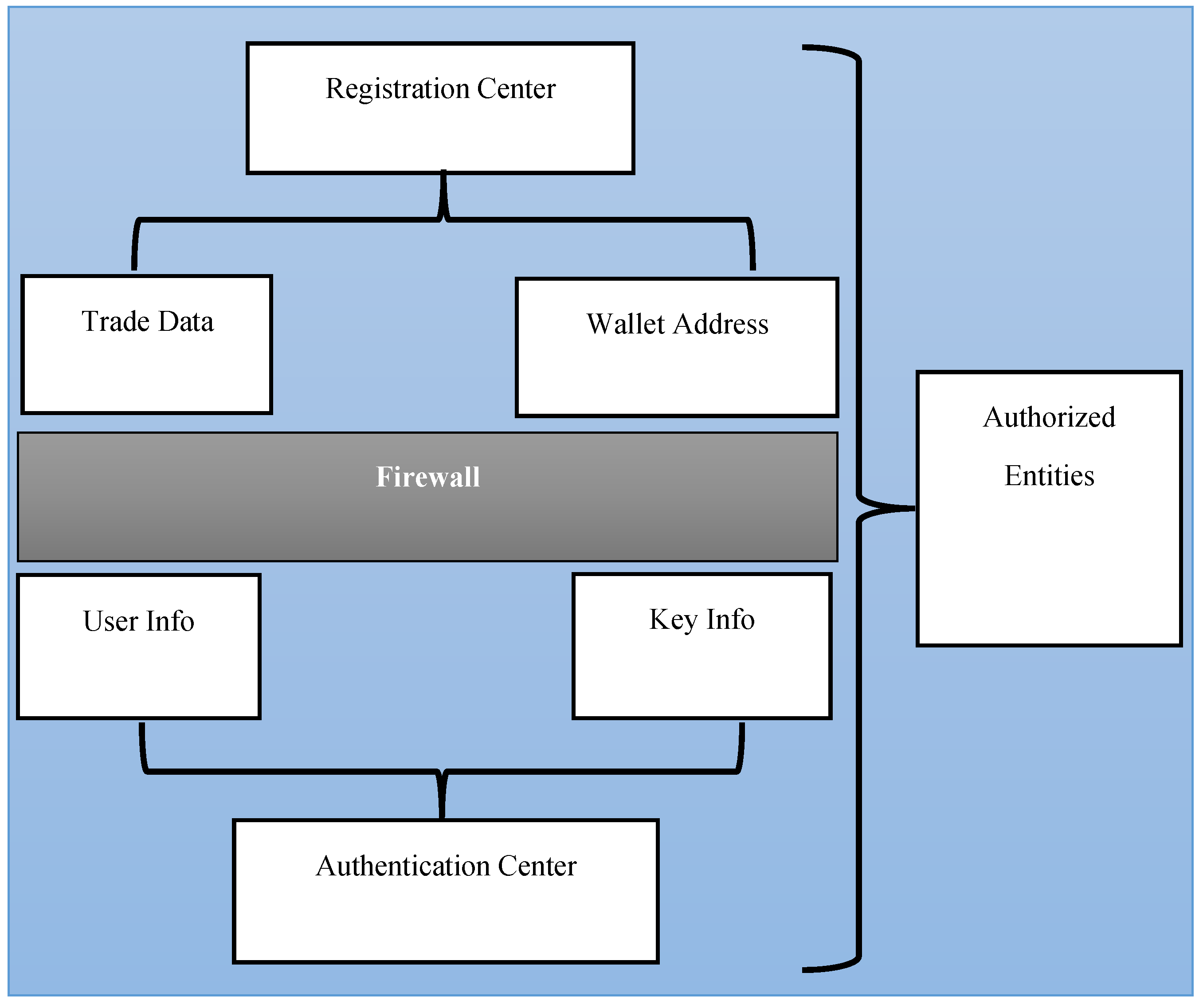

This structure allows the PBOC to tailor anonymity levels and compliance requirements according to the specific risk level of the transaction. Real-ID Authentication (RIDA) status is a critical enabler of this hybrid system, as it categorizes e-CNY wallets based on the degree of identity verification they necessitate. High-RIDA wallets are subject to rigorous verification, including full-name registration and linking to national IDs, which ensures regulatory alignment and strong traceability. Minimal verification is required for low-RIDA wallets, which provide enhanced privacy but restricted functionality. Although the PBOC asserts that low-RIDA wallets maintain robust user anonymity, recent academic evaluations indicate that these wallets may still be indirectly traceable (

Cheng 2023). However, value-based wallet cards, such as transportation cards with embedded e-CNY, maintain the highest level of anonymity, as they are not necessarily linked to an internet-enabled wallet nor registered to a personal identity. As a result, they continue to be the most privacy-preserving instrument in the e-CNY ecosystem, offering users a digital equivalent to physical cash (

Tendyron Corp. and People’s Bank of China Digital Cash Research Institute 2022).

However, this strong anonymity comes at a cost. The maximum balance for wallet cards is limited to 5000 CNY, which restricts their use for high-value transactions. In contrast, e-CNY wallets have significantly higher capitalization limits, ranging from 10,000 CNY to 5 million CNY, depending on the RIDA level of authentication (

Agricultural Bank of China 2021). Wallet cards are also subject to minimal usage restrictions, whereas wallets have tiered requirements aligned with their RIDA status. As the RIDA level increases, so does the transparency of transactions to regulators. It is imperative that the anonymity of users with respect to third parties is not compromised by an elevated RIDA status. All three types of e-CNY carriers—value-based, account-based, and quasi-account-based—maintain transactional anonymity from merchants and other non-governmental actors as a result of the application of general encryption and privacy-enhancing design principles. However, quasi-account-based and value-based e-CNY, particularly wallet cards, can be interpreted as hardware wallets with enhanced privacy features that are specifically designed to achieve specific policy and inclusion objectives from the perspective of regulatory authorities.

2.1. Legal Standing of the e-CNY Wallet

The e-CNY Wallet is an intermediary that allows customers to interact with CBDC and store transactional information. Moreover, wallets connect customers, commercial banks, and central banks. However, there are three types of functions in the context of technology: user authentication, authentication of trading information, and user interface for financial transactions (

Allen et al. 2020). Yet, when it becomes necessary to define what roles the wallet is performing in these connections, as well as the legal status of the wallet itself, unanswered questions remain.

Once the CBDC wallet could be considered a bank account, it is typical for lawmakers worldwide to apply the same regulations to the CBDC wallet as they do to bank accounts. Some believe the CBDC wallet requires special legislation because it differs from a conventional bank account (

Bossu et al. 2020). But if so, then what are the distinctions?

In response to these questions, this section explains why zero-interest accruals are reasonable. Typically, bank operations would be affected by the accumulation of interest. If the CBDC wallet could be considered a bank account, the wallet’s assets could be merged into the bank’s balance sheet, posing technical and legal difficulties. Second, because CBDC wallets compete with bank accounts, some individuals may be concerned that an interest accrual in CBDC wallets would determine the context of competition between wallets and bank accounts and whether zero-interest accruals compromise the wallets’ competitiveness. Some believe a CBDC’s interest rate is essential to its ability to compete with banks (

Kiff et al. 2020). Other opinions suggest that the interest rate on retail deposits must be higher to compete with CBDCs (

Usher et al. 2021), while others have provided interest design implementation plans (

Shah et al. 2020).

To use e-CNY, a person must first have a digital wallet (or a wallet card) for e-CNY (

Agricultural Bank of China 2021). A digital wallet is a software application that enables users to store, manage, and securely transfer digital assets (

Rathore 2016); it can also be used for in-store and online transactions. According to data from Statista, more than two-thirds of the Chinese population use digital wallets for online and offline payments (

Slotta 2023). A digital wallet that does not require a physical bank or bank branch could provide remote people alternative access to the current financial system. Such financial inclusion attracts China’s vast rural population; consequently, digital wallets have a high penetration rate in rural China (

Slotta 2023). Since the inception of the DCEP program, a greater acceptance of e-CNY wallets has emerged, partly because of customers’ previous experience with digital wallets; 261 million individuals have registered an e-CNY wallet.

A client’s e-CNY wallet is “loosely coupled” with their bank account (

Figure 1) (

People’s Bank of China 2021;

People’s Bank of China Digital Cash Research Institute 2020b). The DCEP whitepaper describes the e-CNY wallet as a parallel system to bank accounts that could operate simultaneously under a RIDA account. A foundational policy stance is a critical prerequisite for comparing e-CNY wallets with traditional bank accounts: PBOC has explicitly stated that the e-CNY is not intended to replace the current renminbi system but rather to function as a digital alternative to M0 (physical cash), regardless of its form (digital wallet, prepaid card, or other medium) (

Levitin 2022;

UNIDROIT 2023). This framework allows users to select between e-CNY and traditional fiat currency, thereby increasing the number of payment options without replacing existing mechanisms. The e-CNY’s enhanced safety architecture provides a significant competitive advantage. A critical distinction arises between wallets that allow users to control their private keys directly and custodial wallets, where intermediaries retain key control. Recent controversies in the cryptocurrency industry, particularly the FTX bankruptcy, illustrate the inherent risks when custodial wallets obscure user ownership of private keys (

Fan 2022;

People’s Bank of China 2021). Conversely, the e-CNY wallet architecture guarantees that clients maintain ownership and custody of their private keys, ensuring the user retains control. This user-centric custody model improves both the perceived and actual financial security. Consequently, certain Chinese scholars have proposed that e-CNY wallets are conceptually more similar to safes than to bank accounts—secure, client-controlled repositories of sovereign digital cash.

There are two causes for this loosened connection: (a) The e-CNY wallet is physically independent of the original banking system. (b) A bank account is not a prerequisite for using an e-CNY wallet. Any consumer without a bank account could create an e-CNY wallet on their mobile device. Alternatively, they could purchase an e-CNY wallet card from a bank counter or an automated teller machine (ATM).

Furthermore, the e-CNY wallet can operate regularly without being connected to a bank account with transaction restrictions. For example, the daily transaction limit for real-name authentication accounts without a connected debit card is 10,000 CNY, while an e-CNY wallet connected to a debit card and validated by a bank’s counter will lessen such limitations (

Agricultural Bank of China 2021). Considering their typical income, a non-bank-linked wallet would often be suitable for those who reside in remote areas and utilize e-CNY wallets as a daily payment method

3.

Digital wallets should have the same legal status as bank accounts since they often serve as the same transfer and payment instrument. However, the PBOC emphasizes that digital wallets accrue no interest (

People’s Bank of China 2021), distinguishing them from bank accounts since the Commercial Bank Law (CBL) mandates that banks pay interest on all deposits

4. Concerns remain as to whether the PBOC has the discretion to avoid interest payments and whether a change to the CBL is required to prohibit interest payments to e-CNY end users.

The e-CNY wallet serves as the foundation for the entire DCEP initiative. It has been essential to running the e-CNY system, and customers must establish an e-CNY wallet or a wallet card to participate in the DCEP program (

People’s Bank of China 2021). Like creating a bank account, opening an e-CNY wallet is the first step for a customer to interact with e-CNY. Furthermore, customers’ e-CNY are stored in e-CNY wallets, which function similarly to bank accounts regarding payment and transfer. Since a bank account and a digital e-CNY wallet are similar, could regulators regard the e-CNY wallet as the equivalent of a bank account for e-CNY?

Herein, two conceivable scenarios exist: (a) The e-CNY wallet is considered a bank or quasi-bank account. In this case, it would fall under a new subcategory of bank accounts and would be compatible with any sub-wallet under e-CNY wallets. (b) E-CNY wallets are not considered bank accounts but are more akin to safe deposit boxes that banks offer. Consumers utilize their wallets to reserve assets, and the assets are never under the control of banks but are constantly under client control. However, given that clients retain full custody of the e-CNY private key, e-CNY wallets are more accurately characterized as safes rather than bank accounts—secure, client-controlled repositories of sovereign digital currency.

2.2. The Safe Deposit Box Model for Zero-Interest Accrual

According to the PBOC’s whitepaper, the e-CNY wallet or prepaid cards differ from a bank account, as the whitepaper stated that they are “loosely” linked to bank accounts (

People’s Bank of China 2021). Assuming that e-CNY wallets and wallet cards are bank accounts, there would be no need for the PBOC to use the phrase “loosely coupled with” to describe the connection. Such a narrative suggests that Chinese authorities do not view digital wallets as a subset of bank accounts. If wallets are not considered bank accounts, this would have far-reaching effects and raise questions such as whether banks could include e-CNY wallet assets in their balance sheets and whether banks should pay interest on wallet assets.

This section will address the significance of the safe deposit box situation for banks and their clients. In a scenario concerning safe deposit boxes, consumers might put their fiat money, e-CNY, into safe deposit boxes, such as the e-CNY wallet, in a manner analogous to customers renting physically secure safe deposit boxes from banks, and the bank providing them with the keys to the boxes. In the case of digital money, banks offer their clients the keys to manage their e-CNY wallets. Corporations utilize the Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) for wallet administration, while retail users use traditional password authentication (

Weise 2001).

Under this framework, clients retain complete ownership and control over their wallet assets, and banks act merely as custodians responsible for safeguarding access without authority to utilize or move the funds. The safe-box model presupposes that customers have exclusive control over their wallet contents (

Li 2022;

Yao 2018, p. 313). Because customers possess encryption keys, banks cannot withdraw or use wallet assets for other financial operations, ensuring e-CNY balances remain off-balance-sheet. Even in a bank run or other liquidity crisis, e-CNY wallet assets are insulated from the bank’s insolvency since they are neither legally nor technically part of the bank’s deposit liabilities. Even during liquidity crises or bank runs, e-CNY wallet assets remain protected, as they are neither legally nor technically classified as banks’ deposit liabilities. Customers retain constructive possession, with banks obliged solely to safeguard wallet assets and ensure their return under predefined conditions.

Framing wallets as digital safe deposit boxes serves two critical objectives from a regulatory perspective: (1) it reduces direct competition between CBDC holdings and bank deposits, thereby safeguarding banks’ traditional deposit base; and (2) it mitigates financial disintermediation risks, preventing large-scale shifts from bank deposits into digital wallets that could threaten banks’ liquidity and credit provision capacities. The central bank guarantees that commercial intermediation and credit creation adhere to the conventional banking system by excluding e-CNY wallet assets from bank balance sheets.

Additionally, the PBOC explicitly categorizes e-CNY as an M0-oriented digital currency, positioning it as a genuine alternative to physical cash rather than a deposit instrument (

People’s Bank of China 2021). This positioning emphasizes the wallet’s role as a secure custody solution analogous to a physical safe deposit box. Users retain e-CNY primarily for transactional safety and convenience rather than yield. Consequently, the safe deposit box model solidifies the e-CNY as an alternative currency option while preserving banks’ traditional deposit and lending functions, along with their interest-bearing balance operations. The safe deposit box analogy thus ensures both technical and legal security for wallet assets. Since encryption keys are exclusively held by customers, neither banks nor third parties can access wallet contents. Moreover, commercial banks cannot legally offset client wallet holdings against debts—a practice permissible with traditional deposit accounts under Article 568,

Section 1 of the Chinese Civil Code, where banks may deduct equivalent-value deposits to settle client debts. In a general deposit account, when banks are the creditors to specific clients, and the nature and quality of the debts are equivalent, banks could deduct the clients’ deposits to offset the debt

5. In addition, the assets in e-CNY wallets are not recognized as bank assets and have never been consolidated into bank balance sheets. When banks experience bank runs or other liquidity concerns that might lead to failure, the assets are safer than those in bank accounts, even with e-CNY wallets. Thus, the assets in e-CNY wallets cannot be considered bank assets.

2.3. Non-Interest-Bearing Accrual

Interest is typically the cost of borrowing money. Following the terms of the agreement between the two parties, debtors must pay creditors interest on any outstanding loan balances (

Von Bar et al. 2009). As a borrowing cost, the borrowing status of the money determines whether an asset should earn interest. For bank deposits, depositors transfer funds to the bank, acquiring the right of possession and the ability to use the funds for profitable purposes. As a cost of bank borrowing, banks should charge their clients interest as a fee.

Regarding the e-CNY, some believe interest accruals are necessary but should be considerably lower than the average deposit rate to avoid the potential for Narrow Banking (

Shen and Hou 2021). However, the ability to utilize the funds and the possibility of making a profit is a more compelling argument for the zero-interest accrual situation. As banks never fully use the assets in their customers’ wallets, they are not required to pay the usage charge, in this instance, the interest, for their consumers. Banks are not required to pay interest on e-CNY wallet holdings, and no modifications to CBL legislation are required when e-CNY wallets are recognized as safe deposit boxes.

Thereby, the contents of e-CNY wallets are not regarded as belonging to the banks, and banks will not use the assets from safe deposit boxes, in this example, the e-CNY wallet, to make loans. The bank will not add the property in the e-CNY wallet to its balance sheet. The customer’s investment in the e-CNY wallet is always the client’s cash, and the client has no legal basis for claiming interest payments. In this case, the e-CNY wallet under scenario B is not deemed a bank account but a safe deposit box for the bank; the bank is not required to pay interest to the wallet’s owner and may even charge a lease for safekeeping. As a result, since the assets in the e-CNY wallet have a higher level of protection than regular bank accounts, they could not be used as a basis for a claim for interest under Article 29 of the CBL

6.

The accumulation of funds on a third-party payment platform constitutes a particular case for interest accrual. Third-party payment platforms, such as WeChat Pay and Alipay, have created payment accounts

7 for client’s payment and data recording needs. A client could, for example, transfer 100 CNY to their WeChat payment account or receive 100 CNY from another client’s transfer. Should the third-party payment platform pay interest on the 100 CNY in the client’s account? Whatever the case may be, some regulators worldwide avoid the interest accrual conundrum by establishing that third-party payment platforms are not required to pay interest on capital accumulations. For instance,

Section 3 (2) of the German Payment Services Oversight Act promulgated that an electronic money institution’s fund for e-currency exchange should not be regarded as a public deposit once the fund is zero-interest accrual or benefits (

Li 2021)

8. Similarly, the PBOC promulgated in Article 7 of the Administrative Measures for the Online Payment Business of Non-Banking that the balance of funds in the payment account is not deposited and would not be protected by the DIR

9.

Due to the different nature of e-CNY wallets and deposits, a tradeoff (

Table 2) exists for clients: if clients prefer safety, they could transfer more assets into their e-CNY wallets; if clients have a higher preference for interest return, they could opt for more deposit exposure. The latter would incur the risk of a prospective commercial bank’s bankruptcy since deposit insurance would not cover all their deposit losses if their deposit balance exceeded CNY 500,000. Since they are parallel systems, the e-CNY wallet and bank accounts are designed for distinct purposes and satisfy diverse needs.

Ultimately, this paper discusses the interest accrual conundrum for a CBDC from a functionalist perspective, even though some may argue that privacy or technical considerations render interest accrual for a CBDC impractical (

Kiff et al. 2020). From a central bank’s perspective, a safe box scenario could reduce direct competition between CBDC wallets and bank accounts and prevent the possibility of financial disintermediation. As for commercial banks, viewing the CBDC wallet as a safe deposit box provides more options for clients while avoiding a direct impact on the balance sheet.

2.4. Spillover Implications of the Safe Deposit Box Theory

In most countries, bank account deposits are protected by deposit insurance, albeit with coverage limitations. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was established by the Banking Act of 1933 to protect deposits in the United States. Nevertheless, the FDIC cannot insure all bank account assets. According to the most recent Federal Deposit Insurance Act, the coverage maximum per depositor per covered bank is USD 250,000

10. Per Article 5 of the Deposit Insurance Regulation (DIR), deposit insurance funds in China shall pay depositors for losses up to 500,000 CNY per institution and depositor

11. According to the official explanation, Chinese Deposit Insurance aims to strengthen financial security and depositor protections. It also contributes to fostering the robust future of the financial market by protecting financial stability, enhancing customer confidence, and optimizing the interaction between the government and the market.

12When a customer’s deposit exceeds the insurance limits, the excess is typically not covered by the government. As an example, consider Client A, who owns 800,000 CNY in a typical bank account at Bank C. When a bank run occurs, bank C files for bankruptcy. The 800,000 CNY deposited by Customer A would exceed the DIR insurance limit, and Client A could reclaim the 500,000 CNY from China’s Deposit Insurance Fund, while the remainder of their deposit will be considered a liability of Bank C and recouped via bankruptcy liquidation. It is feasible, however, that Bank C’s net assets will be less than its obligations upon liquidation. This means that customer A would incur deposit losses in the event of insolvency.

Now imagine the e-CNY wallet of Client B at commercial bank C, which holds 800,000 CNY. Bank C has declared bankruptcy due to a bank run. In this case, since Client B’s e-CNY wallet has never been subject to the Deposit Insurance Regulation as it is not a bank account, Client B can recover all of the wallet’s assets. A physical safe deposit box rented by a bank may not be included in a standard liquidation since it is not the bank’s asset, and in the safe deposit box scenario, the assets in an e-CNY wallet are not the bank’s assets. Hence, Client B is able to retrieve 800,000 CNY from the e-CNY wallet. Even though no claims are ever made on DIR, e-CNY wallets provide customers with more security.

Another reason is that the consumer continually manages and controls e-CNY wallet assets, and banks still need to use wallet assets fully. Banks have yet to participate in profitable activities with the funds in customers’ wallets, contributing to the wallet’s better safety rating. Ultimately, the assets in customers’ e-CNY wallets will not be integrated into the bank’s balance sheets and counted as its assets.

In addition, a safe deposit box scenario for an e-CNY wallet might decrease the need for a potentially controversial “bailout” for depositors. Given the most recent incident involving Silicon Valley Bank, any temporary increase in insurance coverage requires some authorities to exhaust their discretionary capabilities and may result in moral hazard (

Nocera and de la Merced 2023). A modification to the insurance coverage limits is contentious. Others feel, for instance, that any legislative strategy that enhances or eliminates the coverage ceiling might prevent a hypothetical bank run without introducing moral hazard (

Nocera and de la Merced 2023). Some contend that minimal deposit insurance hinders competitiveness among banks (

Shy et al. 2016). Still, some suggest higher premiums could prevent moral hazards (

Bartholdy et al. 2003).

In many ways, the services provided by e-CNY wallets resemble those of traditional bank accounts; for example, clients can query transaction information and payment history. However, the e-CNY wallet has safe box features that allow clients to realize their constructive possession over the wallet’s assets, whereas bank accounts represent banks’ liabilities to the clients. The two, in the context of China’s law, would invoke different legal relationships with their clients.

4. Programmability of Digital Wallets via Smart Contracts

Chinese authorities have spent years investigating the suitability of smart contracts’ conditional automatic transfer functions for various scenario applications, such as customer prepayment protection, directed fund utilization, and factoring (

Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China 2018). The development of smart contracts has led to numerous applications. Primarily, e-CNY smart contracts could strengthen labor protection through the preprogrammed payment of labor wages. Branches of the China Construction Bank in Xiong’an have demonstrated that e-CNY can be used with smart contracts to pay the salaries of migrant workers, preventing contractors from misappropriating funds intended as wage payments (

Xiong’an Government 2022). Moreover, smart contracts can increase customer protection by preventing misappropriation and prepayment. In addition, smart contracts could also be regarded as anti-fraud measures to prevent the misuse of financial subsidies and research funds. Some Chinese regulatory officials argue that smart contracts can regulate the use of funds by restricting e-CNY to the payment of goods and services specified in the smart contract.

4.1. Smart Contracts: Extralegal Ramifications

e-CNY is programmable based on smart contract functionality (

People’s Bank of China 2021). According to Nick Szabo’s definition from 1996, a smart contract is a collection of digital promises supported by protocols that control the fulfillment of these responsibilities by the parties (

Szabo 1996). With DLT technology, a smart contract might be executed on top of the blockchain to enforce an agreement between trade parties without needing a trusted third party (

Alharby and van Moorsel 2017). The Federal Reserve believes that with DLT technology, the security and consistency of smart contracts could be enhanced, thereby contributing to their irrevocability (

Lee 2021). In addition, smart contracts might be automatically executable as enforceable content, and the necessary conditions are specified. Due to the irreversibility of automatically executed functions, the smart contract must be formulated with prudence. Some believe that smart contracts are self-enforcing and that contract law remedies are rarely necessary or applicable (

DiMatteo and Poncibó 2018).

Since it is compatible with smart contracts, e-CNY possesses the following two characteristics:

- (a)

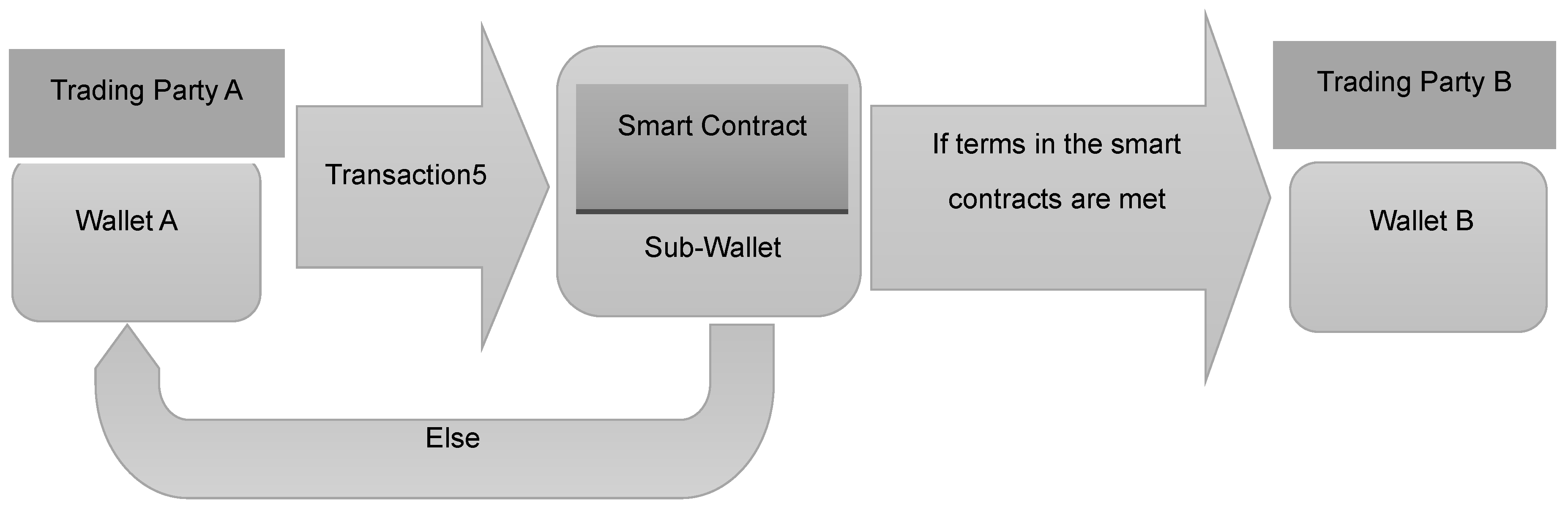

A smart contract will automatically execute if a specific prerequisite is met (

Figure 5);

- (b)

Once a smart contract is signed and engraved in the blockchain, it cannot be modified, which makes few law remedies available.

Some states have no plans to implement functions other than distributed ledger technology, such as smart contracts, on their CBDCs, whereas other nations are investigating further smart contract applications (

Rawat 2023). Smart contracts could provide CBDC with cost and efficiency savings by eliminating intermediaries. Clients are able to load smart contracts for conditional automatic transfers. For example, a client could set up a recurring contract for monthly auto-payment to a charity agent (

The Bank of England 2023). However, questions remain as to whether a smart contract exceeds the existing law or could be fully compliant with it. In addition, what else could be anticipated from such a mechanism?

Figure 5.

The operating mechanism of e-CNY smart contracts.

Figure 5.

The operating mechanism of e-CNY smart contracts.

The smart contract for conditional automatic transfer also includes a lock-in for the capital to be transferred until a specific condition in the smart contract is met, thereby increasing the transfer’s certainty. Although the contract seems suitable for fiscal stimulation to individuals or fiscal transactions across government agencies, as far as the contract’s designers are concerned, implementing such a contract would restrict the CBDC’s circulation (

The Bank of England 2023). Some are even concerned that a restriction on circulation would undermine the free-flowing nature of the CBDCs’ fiat currency or even transform it into a negotiable voucher (

Fan 2022).

4.2. Implementation Practices of Smart Contracts in the e-CNY Framework

Global regulators have recognized the potential of a programmable digital currency and are currently attempting to reach a consensus. For instance, the US Federal Reserve implies that a programmable currency’s value-recording function and programmability may be closely related (

Lee 2021). In addition, Deutsche Bundesbank believes that programmable money and payment must adhere to some inherent logic or precondition program instead of instantaneous response (

Deutsche Bundesbank 2020). The PBOC shares a similar understanding of programmability, reflected in the existing programmable applications and the incoming design of e-CNY (

People’s Bank of China Digital Cash Research Institute 2020a). e-CNY is a programmable digital currency that is automatically executed if the conditions of a smart contract are met. Similarly, e-CNY’s value recording module is affected by smart contract enforcement and will change the wallet’s remaining balance. In addition, the programmability of e-CNY enables clients to access additional applications, including fund usage monitoring (

People’s Bank of China Digital Cash Research Institute 2017).

Even though China’s authorities have diverse explanations for the applications of smart contracts, most smart contract applications are limited to fiscal subsidies and the distribution of consumption vouchers to specific groups of individuals. e-CNY is still programmable with a smart contract application, contrary to previous beliefs that it could not perform such a function (

Allen et al. 2020). Moreover, several complexes’ applications for smart contracts, such as Flash loans (

Wang et al. 2021), are not presented in e-CNY. Even if sophisticated smart contracts such as Flash loans were implemented in e-CNY, it would be complicated for regulators to determine their compatibility with the existing legal framework. Although the application of smart contracts for e-CNY is restricted to specific domains with conditional automatic transfer functionality during the pilot phase, it is easier for regulators to assess the impact of smart contracts on the circulation of existing currencies and legal systems. With a less complex programmable e-CNY, for instance, contracts with a single automatic executive function, it would be simpler to determine if the e-CNY’s intelligent contract function would hinder currency circulation.

4.3. Smart Contracts: Evaluating Potential Impediments to Currency Circulation

When smart contracts have no utilization restrictions, the function of currency circulation would not be affected. Some smart contracts for e-CNY would only have automatic executive preconditions, such as transmitting funds from one client to another when said conditions are satisfied. For instance, one of the PBOC’s patents demonstrates that a hardware wallet could be installed on a vehicle, transforming the entire automobile into a hardware wallet and allowing the on-vehicle wallet module to communicate and transact with third parties (

People’s Bank of China Digital Cash Research Institute 2022). In this scenario, customers could complete an e-CNY transaction without exiting their vehicle. The hardware vehicle model illustrates how the most fundamental functions of smart contracts are incorporated into various carriers. These smart contracts are identical to conventional credit transfers

23 with the addition of an autonomous execution function.

Historically, banks in China collected utility expenses, rent, and tuition on behalf of their principals. With regard to the e-CNY scenario, clients could also execute a specific smart contract authorizing banks to collect such fees from their digital wallets or deduct such expenses at the request of counterparties. When a smart contract’s condition is met, a certain quantity of e-CNY is transferred into the wallet of the counterparty. A smart contract is a mechanism for automatically fulfilling contractual obligations between trading parties. For instance, trading parties could conclude a sales agreement with a clause specifying the smart contract as their payment mechanism.

It is generally acknowledged that cash is the most liquid asset. As the e-CNY can be transferred as cash with smart contracts, a degree of concern exists that smart contracts will undermine the currency’s liquidity by limiting the e-CNY’s utilization scope, thereby reducing it to a negotiable instrument. When funds are transferred, a new, irrevocable legal title is created in the transferor’s name (

Gleeson 2018). By implementing e-CNY, the Chinese government hopes to prevent misappropriation and standardize the circulation of fiscal funds (

Mu 2022b). As an example, the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MOCA) provides 10,000 CNY to Citizen D for medication to alleviate poverty. The MOCA transfers the funds in e-CNY using smart contracts, restricting their utilization.

Suppose the initial transfer of funds is made to the China Charity Federation (CCF). In this instance, the CCF must comply with the predetermined condition of the smart contract and pay the medication charge for Citizen D. The purpose of the MOCA is to supervise the use of the poverty alleviation fund and ensure that it is used by the appropriate individuals and for the intended purpose. Under such a mechanism, the MOCA could guarantee the fund’s dedicated use and precise management (

Wang et al. 2021). Since the fund is contained within a smart contract, its restriction could permeate the bureaucratic system and serve its intended purpose. Even though the funds appear to have been transferred into the CCF’s e-CNY wallet and could be considered its property, the fund’s smart contract restricts the CCF’s use of itself and limits its unrestricted utilization. Will the smart contract’s functionality for conditional automatic transfer, which promotes the limitation of a specific fund, impede the circulation of fiat currency?

The conditional automatic transfer capabilities of the smart contract would not hinder Yuan circulation. Even though the MOCA owns the fund for poverty alleviation, its ultimate use is restricted through its smart contract, which also distinguishes itself from a conventional electronic fund transfer. Imagine that A places 10,000 CNY in an envelope and gives it to B. A entrusts B to pay C’s medical bill, but the hospital is the only one who can open the envelope and deduct the funds for C’s medication expenses. In this instance, only the hospital could release the funds into circulation. Similarly, the MOCA and the CCF are the principal and agent, respectively, and the fund belongs to the MOCA before hospital medication expenses are deducted. As the MOCA had constructive possession over the fund to alleviate poverty, there are no restrictions because of the smart contract’s conditional automatic transfer features on the fund’s actual owner.

The MOCA scenario could also illustrate the application of the factoring smart contract; according to data from the China Bank Association, China’s factoring revenue in 2021 increased by 42.97 percent yearly to 3.56 trillion CNY, representing an immense market opportunity for factoring smart contracts. Concerns remain regarding whether a factoring smart contract would hinder the circulation of the Yuan. Article 761 of the PRC Civil Code established the factoring contract, which permits a creditor to transmit a claim to a factor that provides liquidity to the creditor

24. Under the terms of a factoring agreement, debtors must pay their debt to the factor. Due to various reasons, debtors in China are more inclined to repay their debts to their original creditors, and these factors are typically amenable to this. The counterparty risk will increase if the initial creditors misappropriate the repayment funds.

The smart contract for factoring is intended to reduce counterparty risk by connecting the creditor, the debtor, and the factor. Once the debtors have repaid their original creditors and the smart contract conditions have been met, the factors would receive the debtor’s payment immediately (

People’s Bank of China Digital Cash Research Institute 2020a). Indeed, it appears that smart contracts reduce counterparty risk. Nonetheless, two further issues must be addressed: What happens if the original creditor is in bankruptcy and their assets are frozen—how would the smart contract operate in this scenario? Secondly, if the repayment goes into the original creditor’s wallet and the creditor files for bankruptcy, could the repayment be considered part of the creditor’s bankruptcy assets?

Due to the restriction imposed by the smart contract, the original creditor has no possession right over the repayment, similar to the CCF scenario. Thus, the repayment constantly belongs to the factor. The factor is the principal of the original creditor, who relies on the original creditor to collect the debtor’s repayment

25. Even though the debtor has transmitted the repayment to the original creditor’s e-CNY wallet, the original creditor must act as an agent in the factor’s favor and transfer the repayment to the factor. Therefore, the repayment could not be considered part of the original creditor’s bankruptcy estate and would not be frozen by the court. Even if the original creditor has declared bankruptcy, the smart contract will transmit the repayment to the factor as soon as the creditor receives payment.

Similar to a safe deposit box, which contributes to the depository function of CBDCs, smart contracts serve as an envelope that prevents any intermediary from acquiring possession of the CDBCs contained within. As a result, it would not hinder the function of circulation for e-CNY as the fiat currency.

4.4. Fortuitous Outcomes in Smart Contract Implementation

Despite existing challenges, the e-CNY has implemented some smart contract characteristics in daily payments and is recognized as a potent instrument for customer protection. Increasing client prepayment defaults and fraud rates have served as the impetus for Chinese regulators to combat prepayment fraud with cutting-edge smart contracts. Customers from China frequently experience issues with refunds, particularly when recovering prepayments in instances of pricing fraud.

Unlike the conventional prepayment method, the transaction is considered direct prepayment if a customer’s prepayment for a product or service is deposited directly into the vendor’s bank account. When a vendor declares bankruptcy, it would be difficult for a customer to recoup a prepayment that has been merged into the vendor’s balance sheet. Administrative Measures for Single-Purpose Commercial Prepaid Cards

26 and Administrative Measures for Prepaid Card Businesses of Payment Institutions

27 require vendors to open an escrow or so-called pending payment account to deposit and collect prepayment from clients. Despite this, customers are still exposed to risks:

- (a)

If banks are creditors when a vendor files for bankruptcy, they may still collect their debts directly from the regulated prepayment account, thereby jeopardizing the position of other creditors, such as prepayment-paying customers.

- (b)

When a vendor declares bankruptcy, a regulated prepayment account could be recognized as the vendor’s liquidation assets and distributed to all general unsecured creditors.

The PBOC is attempting to contain such risks by designing a prepayment smart contract that makes the transaction revocable. A prepayment smart contract automatically transfers e-CNY from client wallets to vendor wallets. However, if the transaction is not concluded, the customer’s prepayment can be returned to their wallet if it has not been transferred or consumed (

People’s Bank of China Digital Cash Research Institute 2023).

Customers could initiate a smart contract with a vendor and create a sub-wallet within their primary e-CNY wallet. The client could then transfer a prepayment to the sub-wallet. The prepayment could be automatically put into the vendor’s wallet only if certain conditions are met—in this case, after the vendor has provided the agreed-upon goods or services per the smart contract. Thanks to the conditional automatic transfer function, client prepayments are safe because a vendor must meet the requirements of the smart contract to acquire the payment. Similarly, there is no opportunity for embezzlement of the advance because the vendor only receives the prepayment after the fulfillment is complete due to the smart contract.

At first glance, the irrevocable nature of smart contracts for prepayment scenarios might appear to represent a novel form of transaction. However, it is fundamentally another example of technology facilitating the execution of conventional contractual obligations. Consider stage-based fulfillment—a well-established practice recognized in the legislation of many countries. For instance, Article 372, Paragraph 2 of the Swiss Code of Obligations stipulates that when work is delivered in stages, and installment payments have been agreed upon, each installment is due upon completion of the respective stage

28. In typical commercial scenarios, vendors complete their contractual obligations stage by stage, receiving corresponding payments from their clients at each milestone. Blockchain and smart contract technologies enhance such arrangements by enforcing payment irrevocability and automating payment execution. Specifically, an e-CNY smart contract would automatically release a staged payment into the vendor’s e-CNY wallet once the agreed milestone is verified as complete, eliminating the need for clients to initiate payments manually. Conversely, if the vendor becomes bankrupt or fails to fulfill their obligations at a particular stage, the smart contract would halt the automatic transfer, ensuring funds are safeguarded accordingly.

Admittedly, a concern remains that the programmable nature of smart contracts could introduce rigidity into currency usage, limiting the practical liquidity and flexibility of e-CNY. However, this potential rigidity largely depends on the specific contractual terms programmed into smart contracts rather than being an inherent limitation of the technology itself. The PBOC’s current approach to e-CNY smart contracts indicates careful consideration of this issue, as seen in pilot use cases such as staged payments and factoring agreements. By incorporating conditional triggers aligned with traditional commercial practices, such as installment payments activated upon completion of work stages or repayments transferred upon fulfillment of specified conditions, the PBOC ensures that programmability supports, rather than restricts, regular economic activities. Smart contracts thus provide automated execution and enhanced legal certainty without imposing unnecessary constraints. Additionally, smart contracts can be adjusted to balance security, flexibility, and practicality in various scenarios, as they are optional and customizable rather than mandatory or fixed in scope. This method demonstrates that programmable currencies can be designed to maintain a fluid currency circulation while utilizing technological advantages.

However, a prepayment smart contract has its limits. The objective of customer protection is to ensure that, in the event of a failed transaction, customers can always recoup their entire prepayment and avoid economic losses. Even the inherent mechanism of an existing prepayment smart contract would not safeguard the customer, especially in the event of the vendor’s bankruptcy. First, if the vendor transfers a portion of the prepayment to another bank account or wallet, the conditional automatic executive function of the prepayment smart contract would only operate on the remaining prepayment, if any. Second, even if the prepayment is retained in full in the vendor’s trading wallet, the prepayment may still be considered the vendor’s property if the vendor declares bankruptcy. Other creditors may petition the court to suspend the prepayment in the wallet, deactivating the smart contract’s conditional automatic transfer

29. Customers would have to recoup their prepayment from other creditors, so they would likely be unable to recoup their entire prepayment if the vendor’s assets are insufficient to repay all creditors.

Consequently, a prepayment smart contract may not be as effective for customer protection as a conditional automatic transfer smart contract, such as the hardware wallet model for a vehicle. The customer’s e-CNY will be transferred to the vendor’s wallet only after both parties complete their obligations and verify a transaction.

Nonetheless, when a prepayment is stored in a customer’s e-CNY wallet with a smart contract when the obligation is not fulfilled, the prepayments still belong to the customer. Since prepayment has never entered the vendor’s bank account (regardless of whether it is a regulatory bank account), other creditors, including the banks, would have no claims on the prepayment when the vendor files for bankruptcy. Hence, a customer prepayment is well protected.

Furthermore, as sellers must still fulfill their promise, the clients hold the prepayment in their e-CNY wallet with the smart contract. When a vendor files for bankruptcy, the prepaid cash in the wallet is not a liquidation asset. Prepayments with smart contracts in the customer’s wallet are more secure than straight bank transfers to the vendor’s conventional account. Hence, a customer prepayment is well protected.

Vendors are not subject to additional regulatory obligations when using a smart contract for prepayment instead of a pending payment account. Following the Measures for the Deposit of Pending Payments of Customers of Non-bank Payment Institutions

30, any vendor collecting or transferring these prepayments is subject to restrictions since the pending payment accounts are continuously under surveillance. Inside smart contracts, it would be challenging for a vendor to steal a prepayment using a pending payment account or an e-CNY wallet. The high security of the e-CNY wallet within smart contracts would attract customers with a preference for safety, as it is significantly more secure than direct prepayment or prepayment to a regulatory bank account. Vendors would be more competitive by choosing smart contract prepayment for security-conscious consumers.

In addition, a smart contract for anti-embezzlement might be applied in the public sector outside of private enterprises, such as for funding scientific research or public procurement. When creating smart contracts for e-CNY, consumer protection and currency liquidity will be compromised.

5. Conclusions

The DCEP initiative in China has made considerable progress, but its regulatory and legislative frameworks have not evolved at a commensurate pace. Regulators increasingly face the challenge of crafting legislation to address emerging legal and technical complexities, particularly concerning privacy, interest accrual, and the integration of smart-contract functionality. Given that the e-CNY remains in a prolonged pilot phase, with many of its core design and operational characteristics yet to be finalized, Chinese authorities have understandably adopted a cautious stance toward comprehensive legislative revisions. Although targeted amendments to existing monetary and commercial banking laws may initially appear sufficient, the complexities observed during e-CNY trials suggest that incremental statutory adjustments may prove inadequate. Consequently, more coordinated and systemic legal reforms may become necessary to accommodate and fully regulate CBDC implementation.

Nevertheless, such broader reforms would demand an extended legislative process accompanied by rigorous oversight to address potential systemic risks effectively. Indeed, despite considerable promotional efforts and extensive integration of e-CNY into prominent Chinese digital applications since the release of the PBOC’s white paper in 2021, actual adoption remains modest compared to existing private-sector mobile payment services. Although China’s substantial population and widespread adoption of e-commerce and mobile payment platforms might intuitively suggest favorable conditions for rapid CBDC adoption, these same factors paradoxically serve as significant impediments. Deeply entrenched user habits associated with dominant platforms like WeChat Pay and Alipay continue to constrain consumer acceptance and broader use of the e-CNY.

Thus, while China’s experience with the e-CNY does not represent an ideal model or universal template for global CBDC development, the PBOC’s incremental and pragmatic approach still offers valuable lessons, particularly regarding the complex interplay among existing legal frameworks, established market dynamics, and user adoption behavior. Rather than positioning China’s strategy as a definitive or optimal approach, it serves as an instructive case study highlighting both the opportunities and challenges involved in integrating technological innovation into highly regulated financial environments, especially when facing entrenched consumer payment habits and strong incumbent platforms.